Abstract

Introduction:

Alcohol-related content (ARC) on social media and drinking motives impact college students’ drinking. Most studies have examined peer-generated ARC on drinking outcomes but have yet to extend this relationship to other sources of influence. The current study explores the link between drinking motives, alcohol company ARC, celebrity ARC and alcohol-related problems among college students.

Methods:

Students (N=454) from two US universities completed a cross-sectional online survey assessing demographics; drinking motives (Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised [1]); following/ awareness of alcohol company ARC; engagement with celebrity ARC; peak drinks (most drinks consumed on one occasion); and alcohol-related problems (e.g., passed out).

Results:

Greater celebrity ARC was linked to coping, enhancement, and conformity motives, and peak drinks. Frequent engagement with celebrity ARC was associated with higher problems. Positive indirect effects were observed from celebrity ARC to problems through coping and conformity motives, and peak drinks. After having adjusted for the influence of celebrity ARC, no significant pathways were found between alcohol company ARC and any of the drinking motives, peak drinks or problems, nor were there any indirect effects between alcohol company ARC and problems.

Discussion and Conclusions:

Results revealed a possible explanation for why students who engage with celebrity ARC experience problems was due to coping and conformity motives as well as peak drinks. Interventions targeting alcohol cognitions might assess engagement with and exposure to different sources of ARC given their potential to influence problems.

Keywords: marketing, alcohol, young adults, social media, drinking motives

Introduction

One-third of heavy drinkers are between the ages of 18 and 25 years [2]. In fact, college students and non-college students (29% vs. 25%) are more likely to have engaged in binge drinking (consuming five or more drinks at least once in the past two weeks [3]). Additionally, Schulenberg et al. [3] also found they are more likely to report having been drunk in the previous month. Heavy drinking among college students has been linked to many negative problems including poor academic performance, sexual assault and car accidents [4]. There is a great need to gain a deeper understanding of the etiology of heavy drinking and problems among college students.

Peer drinking behaviour influences college drinking [5]. This influence is usually from college students holding inaccurate perceptions of how much and how often their peers drink (i.e., descriptive drinking norms). The effects of descriptive drinking norms on drinking are supported by the theory of normative social behaviour and social norms theory [6, 7]. These theories suggest that when students incorrectly perceive how much alcohol typical students or close friends are drinking, these misperceptions can lead to increased consumption as students attempt to drink at similar levels to what they believe their campus norms are. Descriptive peer drinking norms consistently predict greater drinking among college students (for a meta-analytic review, see [8]). Another common source of influence on college drinking is mass media (e.g., TV; for systematic reviews see [9–11]) whereby greater exposure to alcohol references are associated both cross-sectionally and prospectively to greater drinking.

Social media is an interactive mix of viewing, sharing, and engaging with content. Young adults (18-29 years) are the largest demographic of social media users with 84% reporting they use at least one social media site [12]. In fact, greater social media use links to greater drinking and problems among adolescents and young adults over time [13–15]. Given the pervasiveness of social media usage, researchers recently postulated that social media is a super peer in that content typically features peer drinking that they may not have encountered in real life [16]. Further, when college students share social media posts, they often display or discuss alcohol [17]. More engagement with alcohol-related content (ARC) links to higher consumption and problems among college students (for systematic reviews, see [18,19]).

Most research examining the relationship between ARC and college drinking outcomes focuses on peer-generated content, neglecting other potential sources such as alcohol companies. One way in which alcohol companies exert influence is by associating themselves with desirable social identities from which consumers can construct their own identities around [20, 21]. Seeing and engaging with alcohol company ARC on social media associates with intentions to drink and heavy episodic drinking among young people [22, 23]. These findings support that alcohol companies and brands build loyalty through online communities.

Another understudied source of ARC which may influence young people is celebrities. A prior study suggests that greater exposure to user-generated content (i.e., content generated by social media users, such as celebrities) links to higher purchase intentions compared to a clearly disclosed advertisement or alcohol brand post [24]. One possible reason is that celebrities act as role models for consumer purchasing intentions and behaviours. According to the consumer doppelganger effect, there may be a unidirectional relationship between a consumer and their celebrity role model, in which the consumer intentionally seeks to mimic the consumption behaviours of the celebrity [25]. Celebrities posting ARC is also relatively common. Turnwald et al. [26] analysed 181 highly followed celebrity Instagram profiles for posts of foods and beverages. Alcoholic beverages were featured in over half of the posts. Given that many young people are preoccupied by celebrity culture, which is often propagated by social media [27], it is critical to examine how engagement with celebrity ARC is linked to drinking and problems.

ARC is associated with drinking motives [28, 29]. These include social (to make friends), enhancement (to increase positive emotions), coping (to reduce negative emotions) and conformity (to fit in with friends; [30, 31]). Engaging with celebrity ARC and viewing alcohol company ARC may activate these motives by making drinking more salient and appealing. For example, as it relates to social and enhancement drinking motives, celebrity and alcohol company ARC often depict a lavish lifestyle centred around social drinking. In terms of conformity, people may aspire to achieve popularity among peers by emulating what is depicted in celebrity or alcohol company ARC. Viewing celebrity ARC or alcohol company ARC that depicts drinking alone or needing to de-stress could relate to coping motives. All four drinking motives associate with college drinking and alcohol-related problems [32–34].

To date, two studies have explored these relationships with one finding that sharing ARC was a significant predictor of consumption and problems when controlling for all four drinking motives [35] and another finding that enhancement motives significantly mediated the relationship between exposure to ARC and drinking [29]. More recently, Ward et al. [28] found that college student ARC posters report greater peak drinks, more alcohol-related problems and higher drinking motives compared to non-posters. This limited research has focused on peer ARC, leaving other sources of ARC unexamined.

The current study

The current study examined a cross-sectional model whereby we hypothesized that college student engagement with celebrity and/or viewing of alcohol company ARC would be positively associated with drinking motives and peak drinks; greater drinking motives and peak drinks would be linked to more problems; and greater exposure to alcohol company ARC and engagement with celebrity ARC would be associated with more problems. Lastly, we explored the indirect effects of drinking motives and peak drinks on the relationship between exposure to alcohol company ARC and/or engagement with celebrity ARC and problems.

Methods

Procedure

The online study received approval from institutional review boards from two large public US universities in the South and Midwest (N=1063). It consisted of a one-time, cross-sectional survey. Participants were recruited from an online participant pool management system specific to each university (i.e., Sona Systems). Respondents had to be 18 years or older. Given the focus of the current study, our analytic sample consisted of participants who reported they drank alcohol and either followed alcohol companies, saw celebrities they follow post ARC, or both (final analytic sample n=454). Thus, from the original 1063 participants, 442 were excluded because they did not endorse any alcohol consumption, and of these 621 drinkers, a further 167 were excluded because they reported not seeing any alcohol company or celebrity ARC. A series of independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses were conducted to examine differences between participants who drank alcohol but reported not following alcohol companies or celebrities who post ARC versus those who drank alcohol and did report seeing this content. Overall, there were no significant differences for most demographic characteristics (i.e., age). However, there was a significant difference for sex with more females reporting they saw alcohol company or celebrity ARC and more males reporting they had never seen this content. It should be noted that a larger proportion of participants saw ARC from these sources than not. Additionally, participants who saw ARC endorsed greater coping and conformity drinking motives (but not social or enhancement motives), peak drinks, and alcohol-related problems. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive differences between participants who never saw versus saw alcohol company or celebrity ARC

| Variable | Never saw alcohol company or celebrity ARC (n = 133) | Saw alcohol company and/or celebrity ARC (n = 454) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 22.83 (6.70) | 22.04 (4.84) | 0.202 |

| DMQ – Social, M (SD) | 3.01 (1.19) | 3.16 (1.06) | 0.194 |

| DMQ – Coping, M (SD) | 2.01 (1.03) | 2.21 (1.01) | 0.048 |

| DMQ – Enhancement, M (SD) | 2.62 (1.15) | 2.75 (1.04) | 0.234 |

| DMQ – Conformity, M (SD) | 1.63 (0.79) | 1.81 (0.96) | 0.031 |

| Peak drinks, M (SD) | 5.05 (3.71) | 6.19 (4.87) | 0.004 |

| Alcohol-related problems, M (SD) | 7.25 (12.44) | 11.48 (14.36) | 0.002 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.027 | ||

| Male | 53 (39.8) | 127 (28.0) | |

| Female | 79 (59.4) | 323 (71.1) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.583 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 54 (40.9) | 171 (38.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 78 (59.1) | 276 (61.7) | |

| Class standing, n (%) | 0.570 | ||

| Freshman | 18 (13.5) | 56 (12.4) | |

| Sophomore | 29 (21.8) | 96 (21.3) | |

| Junior | 40 (30.1) | 149 (33.0) | |

| Senior | 44 (33.1) | 148 (32.8) | |

| Graduate student | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Race, n (%) | – | ||

| White | 71 (20.9) | 269 (79.1) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | |

| Black | 16 (23.5) | 52 (76.5) | |

| Asian | 31 (25.0) | 93 (75.0) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | |

| Other | 8 (24.2) | 25 (75.8) |

Note. N = 587. A total of 34 participants had not completed the questions assessing drinking or alcohol company or celebrity ARC exposure and thus are coded as system-missing in the above analyses. For sex, ethnicity, and class standing, percentages within each column for “never saw alcohol company or celebrity ARC” or “saw alcohol company or celebrity ARC” are reported for each response option. For sex and class standing, Fisher’s Exact Test 2-sided p-values are reported. For ethnicity, Pearson’s chi-square asymptotic 2-sided p-values are reported. As participants could select all that apply for race, chi-square analyses could not be computed and ns and percentages within each race selected are reported. Bold values indicate significant associations.

ARC, alcohol-related content, DMQ, Drinking Motives Questionnaire.

Participants

Participants from both universities (N=454; M=22.04 years old; SD=4.84; Mdn=21.00; range: 18 to 68 years old; 71.1% female) were relatively diverse: 59.3% White; 20.5% Asian; 11.5% Black/African American; 3.3% American Indian/Alaskan; 1.3% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; and 5.5% Other, with 38.3% self-reporting as Hispanic. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant demographic characteristics

| Variable | M (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| M (SD) | |

| Age | 22.04 (4.84) |

| n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 127 (28.0) |

| Female | 323 (71.1) |

| Other | 4 (0.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 171 (38.3) |

| Non-Hispanic | 276 (61.7) |

| Race | |

| White | 269 (59.3) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 15 (3.3) |

| Black | 52 (11.5) |

| Asian | 93 (20.5) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 6 (1.3) |

| Other | 25 (5.5) |

| Class standing | |

| Freshman | 56 (12.4) |

| Sophomore | 96 (21.3) |

| Junior | 149 (33.0) |

| Senior | 148 (32.8) |

| Other | 2 (0.4) |

Note. Participants could select more than one response for race; therefore the percentages do not sum to 100%

Measures

Drinking motives.

The 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised [1] consists of 4 subscales with 5 items each tapping into individuals’ social (‘Because it helps you enjoy a party’; α=0.89; M=3.16; SD=1.06), coping, (‘Because it helps you when you feel depressed or nervous’; α=0.87; M=2.21; SD=1.01 ), enhancement (‘Because you like the feeling’; α=0.87; M=2.75; SD=1.04), and conformity (‘So that others won’t kid you about drinking’, α=0.90; M=1.81; SD=0.96) drinking motives. All questions began with, ‘You drink …’, and items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 ‘Almost never/Never’ to 5 ‘Almost Always/Always’). The Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised has good reliability and validity (e.g., [30, 36]).

Peak drinks.

Peak drinks were measured using one question from the Quantity/Frequency/Peak Index [37]: ‘Think of the occasion you drank the most this past month. How much did you drink?’ Participants selected a response from 1 = ‘0 drinks’ to 26 = ‘25+ drinks’.

Social media use.

Several questions were developed by the researchers to assess what social media platforms participants used, whether they post ARC (1 = ‘Definitely yes’ to 5 = ‘Definitely not’) and which platforms they post ARC on.

Alcohol company ARC.

Alcohol company ARC was comprised of two researcher-generated questions (r=0.19, p=0.002). Participants were asked to self-report how many alcohol companies they followed, ‘Approximately how many alcohol-related companies/products do you follow (e.g., types of alcohol, places which primarily serve alcohol such as clubs or bars)?’ with response options from 1 = ‘none’ to 4 = “6 or more’. If participants said they followed any alcohol-related companies/products they were then asked about their awareness of alcohol companies’ ARC, ‘How often do these companies post alcohol-related content?’ with response options from 1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’.

Celebrity ARC.

Engagement with celebrity ARC was encompassed using two researcher-generated items (r=0.44, p <0.001). Participants were asked, ‘How often do you ‘like’ a celebrities’ alcohol-related post?’ and ‘How often do you comment on a celebrities’ alcohol-related post?’ with response options from 1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’

Alcohol-related problems.

Participants were asked to think about the number of problems that occurred due to their drinking over the past 3 years using the 25-item Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (α=0.96; ‘Got into fights, acted bad, or did mean things’) [38]. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from, 0 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘More than 10 times’, and responses were summed with a potential range of 0-92. Higher scores reflected experiencing more problems (M=11.48; SD=14.36; range: 0 to 92). No items were reversed scored.

Data analysis plan

Before fitting the structural equation model, correlations between variables and patterns of missingness were inspected. The data appeared to be missing at random (<5% missing overall). Structural equation models assessed the relationship between drinking motives, peak drinks, alcohol company ARC, celebrity ARC and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol company ARC and celebrity ARC were specified as predictors. Indirect effects of drinking motives and peak drinks were examined. Alcohol-related problems was the outcome variable. The models were run using maximum likelihood estimation in MPlus 8.8. The following criteria were used: (i) relevance to theory (i.e., being informed by the previous research); (ii) global fit indices (i.e., χ2, Comparative Fit Index and Tucker Lewis Index); (iii) microfit indices (i.e., Root Mean Square Error of Approximation); and (iv) parsimony. A non-significant chi-square suggests that the data do not significantly differ from the hypotheses represented by the model; for comparative fit index and Tucker-Lewis index, fit indices of above 0.90 indicate a well-fitting model, and a root mean square error of approximation of less than 0.05 indicates a well-fitting model.

Results

Alcohol and social media consumption

On average, the highest number of drinks students consumed in a single occasion (i.e., peak drinks) was 6.19 (SD=4.87; range: 1 to 25 drinks). The average frequency for experiencing alcohol-related problems was 11.48 (SD=14.36). Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook were the most commonly used social media platforms. Almost 21% of students indicated they ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ post ARC. Snapchat was the predominant platform for sharing ARC (66%). Nearly 58% of participants followed at least one alcohol company while 93% followed celebrities who post ARC. Refer to Table 3 for additional information, and see Table 4 for zero-order correlations.

Table 3.

Participant social media use characteristics

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Social media platforms have accounts on | |

| 360 (79.3) | |

| 424 (93.4) | |

| Snapchat | 415 (91.4) |

| YouTube | 249 (54.8) |

| 295 (65.0) | |

| Other | 13 (2.9) |

| Participants share ARC | |

| Definitely yes | 33 (7.3) |

| Probably yes | 61 (13.5) |

| Might or might not | 107 (23.6) |

| Probably not | 99 (21.9) |

| Definitely not | 153 (33.8) |

| Platforms participants use to share ARC | |

| 43 (9.5) | |

| 129 (28.6) | |

| Snapchat | 298 (65.6) |

| YouTube | 7 (1.5) |

| 42 (9.3) | |

| Other | 57 (12.6) |

| Number of alcohol-related companies followed | |

| None | 193 (42.3) |

| 1-2 | 176 (38.8) |

| 3-5 | 67 (14.8) |

| 6 or more | 19 (4.2) |

| Frequency of exposure to alcohol company ARC | |

| Never | 13 (5.0) |

| Sometimes | 76 (29.1) |

| About half of the time | 59 (22.6) |

| Most of the time | 81 (31.0) |

| Always | 32 (12.3) |

| Frequency of exposure to celebrity ARC | |

| Never | 27 (6.8) |

| Sometimes | 266 (67.0) |

| About half the time | 60 (15.1) |

| Most of the time | 40 (10.1) |

| Always | 4 (1.0) |

| Frequency of liking celebrity ARC | |

| Never | 69 (17.4) |

| Sometimes | 199 (50.1) |

| About half the time | 69 (17.4) |

| Most of the time | 47 (11.8) |

| Always | 13 (3.3) |

| Frequency of commenting on celebrity ARC | |

| Never | 241 (61.0) |

| Sometimes | 98 (24.8) |

| About half the time | 31 (7.8) |

| Most of the time | 19 (4.8) |

| Always | 6 (1.5) |

Note. Percentages do not sum to 100% for questions about what social media platforms participants use or post ARC to because participants could select more than one response.

ARC, alcohol-related content.

Table 4.

Zero-order correlations among key variables

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alc comp follow | – | |||||||||

| 2. Alc comp ARC exp freq | 0.19 ** | – | ||||||||

| 3. Freq ‘like’ celeb ARC | 0.14 ** | 0.18 * | – | |||||||

| 4. Freq ‘comment’ celeb ARC | 0.10 * | −0.09 | 0.44 *** | – | ||||||

| 5. DMQ – Social | 0.06 | 0.16 * | 0.21 *** | 0.001 | – | |||||

| 6. DMQ – Cope | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.27 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.53 *** | – | ||||

| 7. DMQ – Enhance | 0.07 | 0.18 * | 0.23 *** | 0.07 | 0.74 *** | 0.64 *** | – | |||

| 8. DMQ – Conformity | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.22 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.35 *** | – | ||

| 9. Peak drinks | 0.11 * | 0.11 | 0.13 * | 0.10 * | 0.33 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.17 *** | – | |

| 10. RAPI | 0.15 ** | 0.03 | 0.32 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.33 *** | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| M | 1.81 | 3.16 | 2.34 | 1.61 | 3.16 | 2.21 | 2.75 | 1.81 | 6.19 | 11.48 |

| SD | 0.84 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.06 | 4.87 | 14.36 |

Note. The number of alcohol-related companies/products followed on social media by participants included response options from 1 = none to 4 = 6 or more. The frequency of participant exposure to alcohol-related company ARC, participants ‘liking’ or ‘commenting on’ celebrity ARC included response options from 1 = Never to 5 = Always. The items within the DMQ subscales had response options from 1 = Almost never/never to 5 = Almost always/always. For peak drinks, response options ranged from ‘1 drink’ to ‘25+ drinks’. The items of the RAPI included response options from 0 = Never to 4 = More than 10 times. Bold values indicate significant correlations.

p <0.05

p <0.10

p <0.001.

Alc comp, alcohol company; ARC, alcohol-related content; celeb, celebrity; DMQ, drinking motives questionnaire; Exp, exposure; Freq, frequency; RAPI, Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index [37].

Structural equation model

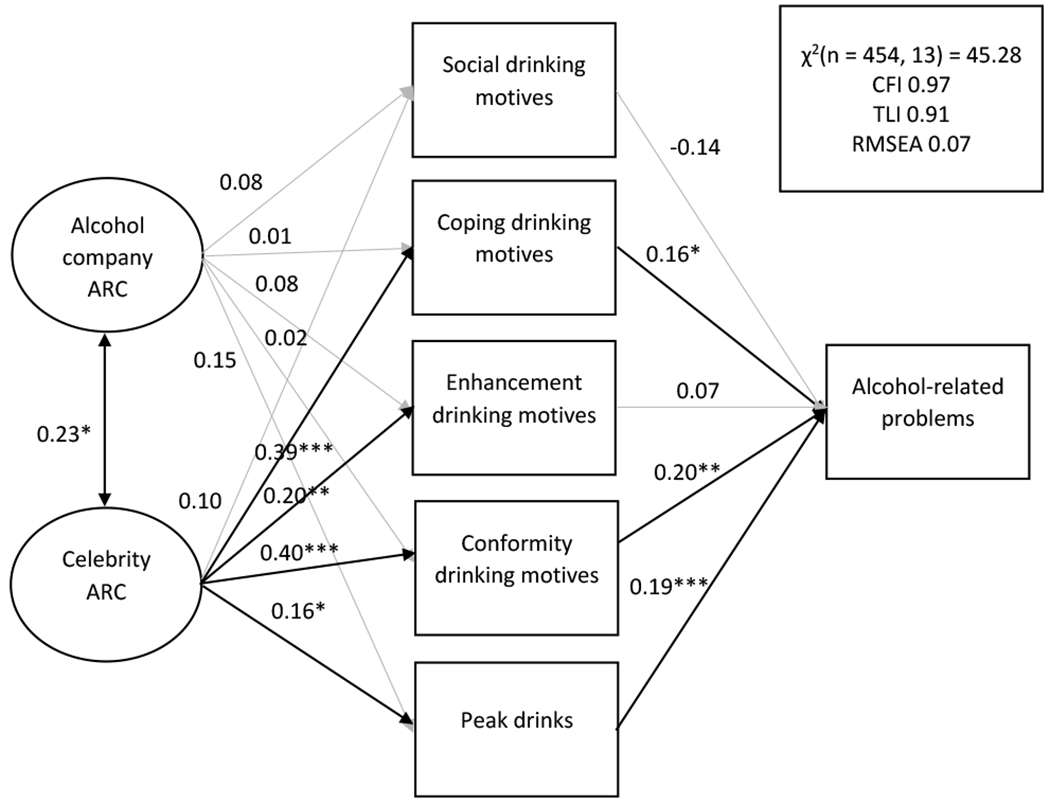

The model examined associations between alcohol company ARC, celebrity ARC, drinking motives, peak drinks and alcohol-related problems. The model fit the data, χ2 (n=454, 13)=45.28, comparative fit index 0.97, Tucker-Lewis index 0.91, root mean square error of approximation 0.07. Alcohol company ARC was not related to peak drinks (β=0.15, p=0.127), social (β=0.08, p=0.385), coping (β=0.01, p=0.872), enhancement (β=0.08, p=0.409) or conformity (β=0.02, p=0.750) drinking motives. Celebrity ARC was related to coping (β=0.39, p <0.001), conformity (β=0.40, p <0.001), enhancement (β=0.20, p=0.006), and peak drinks (β=0.16, p=0.022) but not social motives (β=0.10, p=0.173). More frequent engagement with celebrity ARC was directly linked to higher levels of alcohol-related problems (β=0.34, p <0.001) but greater exposure to alcohol company ARC was not (β=0.08, p=0.220). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The indirect effects of drinking motives and peak drinks on the association between alcohol company and celebrity ARC, and alcohol-related problems

Note. Standardised parameter estimates are provided. Significant findings are indicated with asterisks and black (vs. grey) lines for path coefficients. Direct effects are not pictured for clarity but were included. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001.

ARC, alcohol-related content; CFI, comparative fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; TLI, Tucker-Lewis index.

There were significant indirect effects for coping (0.06, p=0.012) and conformity motives (0.08, p=0.001), and peak drinks (0.03, p=0.031) on the path from celebrity ARC to alcohol-related problems. However, there were no significant indirect effects for social (−0.02, p=0.152) or enhancement motives (0.01, p=0.501) on the path from celebrity ARC to alcohol-related problems. In addition, there were no significant indirect effects for peak drinks (0.03, p=0.140), or social (−0.01, p=0.424), coping (0.002, p=0.872), enhancement (0.01, p=0.519), or conformity motives (0.01, p=0.751) on the path from alcohol company ARC to alcohol-related problems.

Discussion

The current study aimed to disentangle how engagement with celebrity ARC and exposure to alcohol company ARC as well as drinking motives influence college students’ alcohol-related problems. In terms of direct effects, engagement with celebrity ARC was significantly associated with enhancement, conformity, and coping motives, and peak drinks. Celebrity ARC may activate enhancement motives (e.g., ‘Because it’s exciting’) since celebrities often depict drinking as part of their lavish lifestyles [26]. However, only three significant indirect effects emerged.

There was a positive significant indirect effect of conformity motives on the pathway from engagement with celebrity ARC to problems. According to social comparison theory [39, 40], which conceptually overlaps with conformity motives (e.g., ‘To fit in with a group you like’) , the act of socially comparing oneself to another person or group often activates the need to conform to perceived behavioural norms. One study revealed that high social comparison orientation moderated the association between perceived peer descriptive norms and alcohol-related problems such that those high in social comparison who perceived their peers to drink more experienced more problems [41]. Relatedly, an experiment found that social media displays of older peers’ drinking (i.e., ARC) significantly increased young adolescents’ willingness to drink [42], presumably to conform to perceived older peer norms. Thus, students who are motivated to drink to conform – perhaps due to social comparison – could experience more problems.

Furthermore, there was a positive and significant indirect effect of coping motives on the pathway from engagement with celebrity ARC to problems. Literature suggests that young adults who rely on avoidant coping are more likely to drink to cope, experience more alcohol-related problems, [43–45] and exhibit signs of pathological internet use [46]. Thus, young adults who turn to celebrity social media content to escape may be comparing themselves to the perfectly curated lives of celebrities, resulting in feelings of inadequacy, which they quell by drinking to cope. Other young adults may drink to conform with their perceived celebrity drinking norms. Since alcohol is readily available to most college students, drinking may be an accessible and relatable method of embodying their venerated celebrities’ lifestyles compared to less attainable aspects, such as walking the red carpet.

Third, there was a positive and significant indirect effect of peak drinks on the pathway from engagement with celebrity ARC to problems. It could be that celebrity ARC boosts the salience of alcohol, increasing students’ peak drinks and leading to more problems. Recent research found that Instagram users’ desire to mimic a social media influencer was positively associated with their intentions to consume the same products shown in the influencer’s posts (i.e., consumer doppelganger effect). Although the researchers did not examine mainstream celebrities and alcohol consumption/purchase intentions, this study suggests that users may be influenced to mimic their perceptions of their favourite celebrities’ drinking behaviours (e.g., engaging in higher peak drinks) to emulate them [47].

Finally, the results partially supported our direct effect hypotheses that students with higher motives and peak drinks reported more problems. Surprisingly, we did not find a significant association with enhancement or social motives and problems. However, when looking at the bivariate correlations for the motives, the factors were highly correlated (r=0.35-0.74). Thus, it appears there might be a suppression effect occurring due to multi-collinearity. As expected, we found that peak drinks, coping, and conformity motives were positively and significantly associated with problems.

Our results did not find a significant direct effect between student following and awareness of alcohol company ARC and problems. However, we did not assess participants’ engagement with alcohol company ARC posts (e.g., likes). Engagement may indicate greater brand loyalty [48], which consequently may have more of an impact on participants’ alcohol-related problems. Moreover, greater student engagement with celebrity ARC was associated with more problems. This aligns with previous research which has found that engagement with ARC in general is associated with more problems [18].

No indirect effects were found between following and awareness of alcohol company ARC and motives, peak drinks, or problems. Since both celebrity ARC and alcohol company ARC were entered into the model, celebrity ARC may explain more of the variance in terms of the association with problems. An aforementioned experimental study found negative indirect effects via persuasion knowledge and via negative affective reaction such that users who saw a brand’s posts as opposed to user-generated content reported lower purchase intentions [24]. Thus, celebrity ARC may be less likely to trigger negative affect as consumers do not feel that the celebrity is actively attempting to persuade them to buy alcohol as opposed to alcohol company ARC. Given the importance that many young people place on celebrity culture, they may be more influenced to drink after seeing celebrities’ ARC and consequently experience more problems.

Limitations and future directions

While existing research links coping and conformity motives to peak drinks and alcohol-related problems [49, 50], our study is among the first to examine the relationship between students’ engagement with celebrity ARC and viewing of alcohol company ARC, motives and alcohol-related problems. However, several limitations should be acknowledged alongside the current study’s strengths. First, the study is cross-sectional; thus, temporal order and causality cannot be inferred. Another limitation is that a timeframe for alcohol company and celebrity ARC posts was not specified, which may have led to recall bias. We also did not include participants’ engagement with their peers’ ARC, which could have provided greater insight into how the disparate sources of ARC differentially influence alcohol-related problems. Additionally, how often participants viewed celebrity ARC was not assessed. It is possible that participants who saw celebrity ARC posts more often might have been influenced to drink and experience more problems. Conversely, engagement with alcohol company ARC was also not assessed. It is possible that engagement with alcohol company ARC is a stronger indicator of whether an individual is more likely to report higher peak drinks, motives and consequently, more problems. Furthermore, engagement with ARC may trigger algorithms to display more alcohol company ARC on users’ social media feeds. In the future, researchers may want to explore how often participants engage with ARC posted by alcohol companies.

Although there is a huge body of literature investigating celebrity influences on other health-related behaviours [51–55], the current study contributes to the field by highlighting the potential impact of celebrity ARC on alcohol-related problems among college students and underscores the need for additional research in this area. One such factor which the literature has yet to investigate is parasocial relationships, which are defined as strong, one-sided emotional attachments to a celebrity [56, 57]. A student with a parasocial relationship with a celebrity may be using that relationship to cope with loneliness [58] which, in turn, may lead them to not only drink more to conform but also further their reliance on drinking to cope. There is strong evidence which suggests that college students who drink to cope may be especially vulnerable to experiencing long-term problems [30, 36, 59]. Studies indicate that negative health consequences may result from parasocial relationships that involve a media figure who presents unhealthy behaviours such as vaping [60] and eating fast food [61]. A natural extension of this study may be to examine how parasocial relationships with celebrities affect the influence of celebrity ARC, and consequently, drinking outcomes. The pervasive nature of social media compounded by the intensity of a parasocial relationship may provide a unique environment in which individuals may continue to feel the need to conform to the celebrity’s ARC beyond their college years, which may lead to long-term problems.

Conclusions

The current study adds to the limited literature by exploring the indirect effects of motives on the association between ARC and alcohol outcomes among college students. Moreover, these findings emphasize the unique role that celebrity ARC may also play in creating an online drinking culture that could lead to problems among college students. To date, the extant literature has almost exclusively focused on peer ARC in relation to alcohol-related outcomes. Similar to peer ARC, celebrity ARC may be transforming young people’s thought processes surrounding alcohol as they feel compelled to drink to be analogous to their favourite celebrities, which consequently impacts their drinking. The present study also highlights that, in the digital age, it may be necessary to explore other online avenues of influence when designing alcohol interventions that target young people’s cognitions and drinking.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Grant numbers: R00AA025394 and K99AA025394 (PI: Steers), F31AA029945 (PI: Strowger), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25DA054015 (MPIs: Obasi and Reitzel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Cooper M Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:117–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.SAMHSA, National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2020: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-60. 2021, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinker DV, Krieger H, Neighbors C. Social network factors and addictive behaviors among college students. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:356–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: a review of the research. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13: 391–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimal RN, Real K. How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms: A test of the theory of normative social behavior. Communication Research. 2005;32:389–414. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: some research implications for campus alcohol education programming*. Int J Addict. 1986;21:961–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:331–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson P, De Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:229–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finan LJ, Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW, Balassone A, Kaner E. Alcohol marketing and adolescent and young adult alcohol use behaviors: A systematic review of cross-sectional studies. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2020;Sup 19:42–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith LA, Foxcroft DR. The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pe Research Center. Social Media Use in 2021. 2021. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/

- 13.Gámez-Guadix M, Calvete E, Orue I, Las Hayas C. Problematic Internet use and problematic alcohol use from the cognitive–behavioral model: A longitudinal study among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2015;40:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaBrie JW, Trager BM, Boyle SC, Davis JP, Earle AM, Morgan RM. An examination of the prospective associations between objectively assessed exposure to alcohol-related Instagram content, alcohol-specific cognitions, and first-year college drinking. Addict Behav. 2021;119:106948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng Fat L, Cable N, Kelly Y.Associations between social media usage and alcohol use among youths and young adults: findings from Understanding Society. Addiction. 2021;116:2995–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmore KC, Scull TM, Kupersmidt JB. Media as a “Super Peer”: How adolescents interpret media messages predicts their perception of alcohol and tobacco use norms. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:376–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno MA, D’Angelo J, Hendriks H, Zhao Q, Kerr B, Eickhoff J. A prospective longitudinal cohort study of college students’ alcohol and abstinence displays on social media. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis BL, Lookatch SJ, Ramo DE, McKay JR, Feinn RS, Kranzler HR. Meta-analysis of the association of alcohol-related social media use with alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42:978–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta H, Pettigrew S, Lam T, Tait RJ. A systematic review of the impact of exposure to internet-based alcohol-related content on young people’s alcohol use behaviours. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51:763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banet-Weiser S Authentic: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. 2012: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hearn A ‘Meat, Mask, Burden’. J Consum Cult. 2008;8:197–217. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alhabash S, McAlister AR, Quilliam ET, Richards JI, Lou C. Alcohol’s Getting a Bit More Social: When Alcohol Marketing Messages on Facebook Increase Young Adults’ Intentions to Imbibe. Mass Commun Soc. 2015;18:350–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critchlow N, Moodie C, Bauld L, Bonner A, Hastings G. Awareness of, and participation with, digital alcohol marketing, and the association with frequency of high episodic drinking among young adults. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2016;23:328–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayrhofer M, Matthes J, Einwiller S, Naderer B. User generated content presenting brands on social media increases young adults’ purchase intention. Int J Advert. 2020;39:166–86. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruvio A, Gavish Y, Shoham A. Consumer’s doppelganger: A role model perspective on intentional consumer mimicry. J Consum Behav. 2013;12:60–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turnwald BP, Anderson KG, Markus HR, Crum AJ. Nutritional analysis of foods and beverages posted in social media accounts of highly followed celebrities. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:e2143087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Power S. Why Gen Z is more obsessed with celebrities than any other age group: Newsweek Digital LLC. 2022. [cited 24 July 2023]. Available from: https://www.newsweek.com/gen-z-social-media-celebrity-obsessed-mental-health-tiktok-1755381

- 28.Ward RM, Steers M-LN, Guo Y, Teas E, Crist N. Posting alcohol-related content on social media: Comparing college student posters and non-posters. Alcohol. 2022;104:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle SC, LaBrie JW, Froidevaux NM, Witkovic YD. Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addict Behav. 2016;57:21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S et al. , Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In: Sher KJ, editor. The Oxford Handbook of substance use and substance use disorders. New York, US: Oxford University Press; 2016, Vol. 1, p. 375–421. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox W, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:168–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bresin K, Mekawi Y. The “why” of drinking matters: A meta-analysis of the association between drinking motives and drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:841–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyvers M, Hasking P, Hani R, Rhodes M, Trew E. Drinking motives, drinking restraint and drinking behaviour among young adults. Addict Behav. 2010;35:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westgate EC, Neighbors C, Heppner H, Jahn S, Lindgren KP. “I will take a shot for every ‘like’ I get on this status”: posting alcohol-related Facebook content is linked to drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper ML. How stable is the motive–alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Interventions for College Students: A harm reduction approach. 1999, New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novak KB, Crawford LA. Perceived drinking norms, attention to social comparison information, and alcohol use among college students. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2001;46:18–33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Festinger L A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–40. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Litt DM, Lewis MA, Stahlbrandt H, Firth P, Neighbors C et al. Social comparison as a moderator of the association between perceived norms and alcohol use and negative consequences among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:961–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Litt DM, Stock ML. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: the roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:708–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Digdon N, Landry K. University students’ motives for drinking alcohol are related to evening preference, poor sleep, and ways of coping with stress. Biological Rhythm Research. 2013;44:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woodhead EL, Cronkite RC, Moos RH, Timko C. Coping strategies predictive of adverse outcomes among community adults. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70:1183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez VM. Factors linking suicidal ideation with drinking to cope and alcohol problems in emerging adult college drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;27:166–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNicol ML, Thorsteinsson EB. Internet addiction, psychological distress, and coping responses among adolescents and adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017;20:296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ki CWC, Kim YK. The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychol Mark. 2019;36:905–22. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng X, Cheung CMK, Lee MKO, Liang L. Building brand loyalty through user engagement in online brand communities in social networking sites. Inf Technol People. 2015;28:90–106. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S, Kwon J-H. Moderation effect of emotion regulation on the relationship between social anxiety, drinking motives and alcohol related problems among university students*. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terlecki MA, Buckner JD. Social anxiety and heavy situational drinking: Coping and conformity motives as multiple mediators. Addict Behav. 2015;40:77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: The Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1601–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans DG, Barwell J, Eccles DM, Collins A, Izatt L, Jacobs C, et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: How high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liede A, Cai M, Crouter TF, Niepel D, Callaghan F, Evans DG. Risk-reducing mastectomy rates in the US: a closer examination of the Angelina Jolie effect. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;171:435–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garnett C, Perski O, Beard E, Michie S, West R, Brown J. The impact of celebrity influence and national media coverage on users of an alcohol reduction app: A natural experiment. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newcomb MD, Antoine Mercurio C, Wollard CA. Rock stars in anti-drug-abuse commercials: An experimental study of adolescents’ reactions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:1160–85. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horton D, Wohl RR. Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry. 1956;19:215–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levy MR. Watching TV news as para-social interaction. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1979;23:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baek YM, Bae Y, Jang H. Social and parasocial relationships on social network sites and their differential relationships with users’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16:512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: a ten-year model. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daniel ES, Crawford Jackson EC, Westerman DK. The influence of social media influencers: Understanding online vaping communities and parasocial interaction through the lens of Taylor’s six-segment strategy wheel. J Interact Advert. 2018;18:96–109. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Myrick JG. Connections between viewing media about President Trump’s dietary habits and fast food consumption intentions: Political differences and implications for public health. Appetite. 2020;147:104545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]