Summary

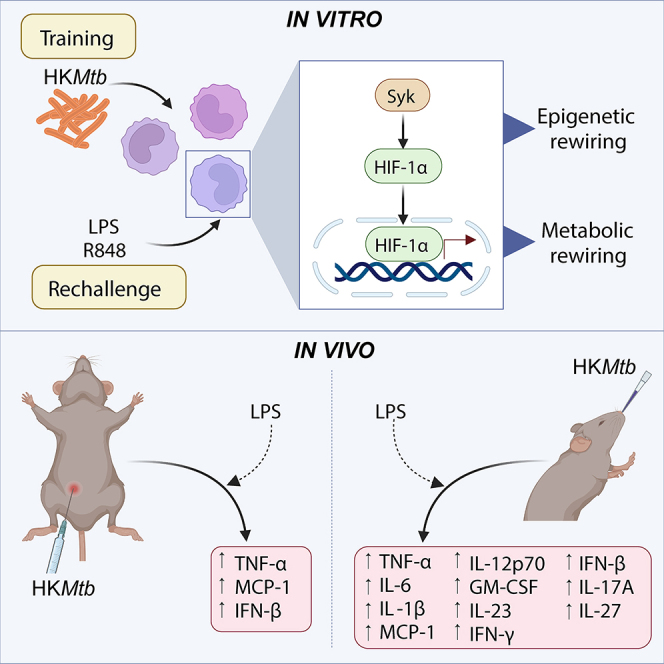

Trained immunity (TI) represents a memory-like process of innate immune cells. TI can be initiated with various compounds such as fungal β-glucan or the tuberculosis vaccine, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Nevertheless, considering the clinical applications of harnessing TI against infections and cancer, there is a growing need for new, simple, and easy-to-use TI inducers. Here, we demonstrate that heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) induces TI both in vitro and in vivo. In human monocytes, this effect represents a truly trained process, as HKMtb confers boosted inflammatory responses against various heterologous challenges, such as lipopolysaccharide (Toll-like receptor [TLR] 4 ligand) and R848 (TLR7/8 ligand). Mechanistically, HKMtb-induced TI relies on epigenetic mechanisms in a Syk/HIF-1α-dependent manner. In vivo, HKMtb induced TI when administered both systemically and intranasally, with the latter generating a more robust TI response. Summarizing, our research has demonstrated that HKMtb has the potential to act as a mucosal immunotherapy that can successfully induce trained responses.

Subject areas: Therapy, Immune response, Microbiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) induces trained immunity (TI)

-

•

HKMtb-induced TI relies on epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming

-

•

Syk and HIF-1α mediate the induction of TI by HKMtb

-

•

Intranasal administration of HKMtb generates robust trained systemic responses

Therapy; Immune response; Microbiology

Introduction

A complex network of cells, tissues, and molecules integrates our immune systems to protect our bodies against harmful insults. Traditionally, the immune system has been considered a dichotomy: the innate immune system, which provides a first line of defense, and the adaptive immune system, which confers long-term immunity through the generation of specific immune responses. In the last decade, however, this paradigm has been challenged due to the revelation of a fascinating phenomenon: trained immunity (TI).1

TI refers to the ability of innate immune cells such as monocytes or macrophages to develop a memory-like effect that results in an improved proinflammatory response to a secondary challenge.1 An essential attribute of this memory is its heterologous capacity for recall, given that a boosted inflammatory response can be generated by stimuli unrelated to those that induced the training process.2 Mechanistically, the epigenetic reprogramming of inflammatory promoters drives the characteristic long-lasting proinflammatory trained response, in particular, the enrichment of specific histone acetylation and methylation.1,3 Of note, metabolic rewiring is also relevant for the training process by providing key cofactors required to establish the characteristic epigenetic TI markers.4 Altogether, TI is considered an innate immune memory process.2

The current insights regarding the training process are mostly attributed to β-glucan as a TI inducer because β-glucan was the first stimulus studied in this context and it uncovered the mechanisms involved in the TI process.1 β-glucan is a type of polysaccharide found in fungal cell walls, and it is recognized by the Dectin-1 receptor. This recognition triggers a PI3K/mTOR/HIF-1α-mediated pathway, activating the glycolytic Warburg effect and TI-related epigenetic reprogramming.3,5 Interestingly, β-glucan can be found either in a soluble or in a particulate form, which conditions its immunomodulatory properties, given that Dectin-1 signaling is only activated by particulate β-glucan.6 Depending on their physical properties, soluble forms of β-glucan, such as laminarin, are known to inhibit subsequent Dectin-1 signaling.7 Along these lines, TI triggering has been experimentally achieved by using particulate forms of β-glucan as an inducer, both in vitro1 and in vivo.3,8 A commercially available β-glucan peptide consisting of a highly ramified, high-molecular-weight polysaccharide linked to a polypeptide portion has been reported to induce TI in vivo9; nevertheless, its particulate nature has not been fully elucidated.

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), a live-attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis originally developed as a vaccine against tuberculosis, is a well-established TI inducer.10 Epidemiological studies have shown that BCG vaccination not only confers protection against tuberculosis but also enhances immune responses against non-tuberculosis-related heterologous infections.11 Currently, BCG is one of the gold-standard stimuli to induce TI in humans, both in vitro12 and in vivo.13,14 Mechanistically, the signaling axis NOD2 receptor/Rip2 kinase is responsible for the training induced by BCG,10 in which PI3K/mTOR12 and autophagy15 also play a role. Thus, BCG represents a component with training capabilities that is used in clinical practice.

In our search for alternative TI inducer formulations, we studied MV130, a complex immunotherapy composed of various proportions of whole heat-inactivated gram-positive (90%) and gram-negative (10%) bacteria, originally indicated for treating recurrent respiratory tract infections.16 We had reported that MV130 generates TI, conferring heterologous protection against fungal and viral infections.17,18 MV130 modulates immune responses through Rip2 kinase and MyD88,16 although the role of these signaling pathways in the training process has not been addressed. Nevertheless, MV130 introduced the novelty of a heat-killed bacterial preparation with the capability of training innate immune cells by modulating their metabolism and epigenetic landscape.17

Interestingly, the in vivo induction of TI by these 3 components is achieved by various routes of administration. β-glucan is administered systemically in mouse models, primarily after intraperitoneal injection.3,8 BCG has been injected intradermally in humans,11 and typically subcutaneously in mice,19 with some intravenous20 or mucosal/intranasal21,22 attempts. Lastly, MV130 is administered as a sublingual spray in humans23,24 and mostly intranasally in mice.16,18 Comparative studies to address the relevance of the administration route employing a defined TI inducer are scarce; however, at least for BCG, mucosal delivery confers a stronger TI induction than intradermal vaccination in terms of enhanced innate cytokine production.22

The nature of these stimuli and their administration route determine their potential clinical application for triggering TI. The particulate nature of β-glucan limits its transition from mouse models to clinical applications because it requires systemic administration. However, there is no doubt regarding the clinical use of BCG in clinical practice as an intradermal vaccine, or even by intravesical instillation as immunotherapy against bladder cancer.25 However, due to the live nature of BCG, it bears the risk of localized or disseminated infections, depending on the patient’s immunological status26 and the route of administration. Although MV130 as a heat-killed bacteria-based mucosal immunotherapy has shown actual success in protecting against heterologous infections, with an excellent safely profile,27,28 MV130’s polybacterial nature could hamper the dissection of relevant mechanistic clues in certain clinical scenarios, such as autoimmunity.29,30

Linking the capacity of the mycobacterial vaccine BCG to induce TI, with the background provided by MV130 regarding heat-killed bacteria as a TI inducer, we here demonstrate the capacity of a commercial preparation of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) as a TI inducer in human monocytes. This demonstration supports a recently published study using environmental Mycobacterium manresensis contained in a food supplement as a TI inducer.31 Furthermore, the HKMtb-induced trained heterologous response against both the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the TLR7/8 ligand R848 relies on spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, and epigenetic reprogramming, generating a glycolytic rewiring. Of note, HKMtb induced TI in vivo when administered both intraperitoneally and intranasally. Altogether, our results indicate that a simple and commercially available HKMtb preparation constitutes a TI inducer. Furthermore, considering that our in vivo data reinforce the importance of the administration route of these compounds, more relevant from the clinical perspective is that intranasal/mucosal delivery of heat-killed mycobacterial preparations generates robust TI responses.

Results

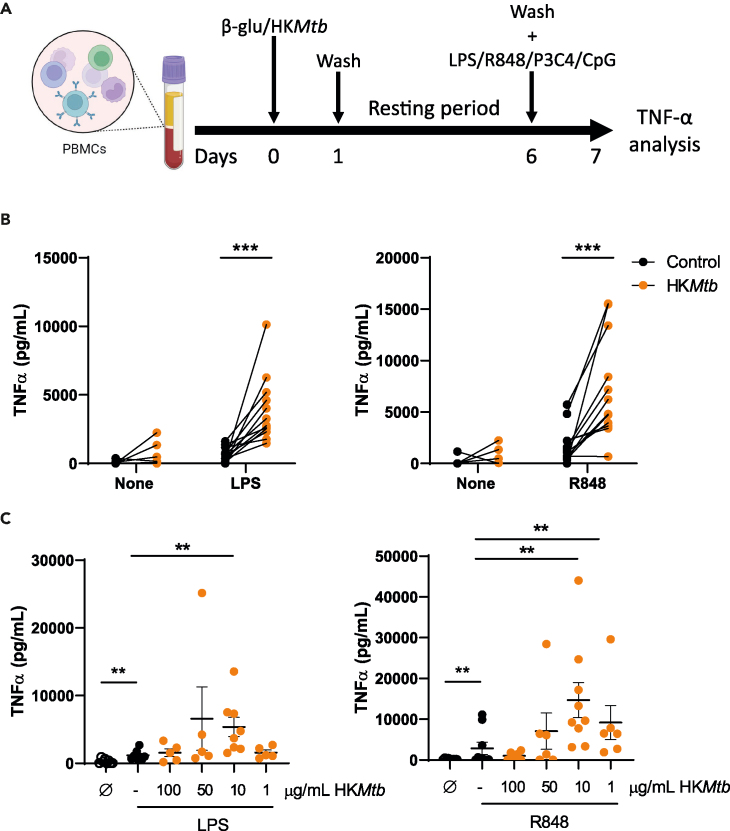

HKMtb induces TI against heterologous challenges

The BCG vaccine, which is a live-attenuated mycobacteria-based vaccine, has been found to induce TI. Another known TI inducer is MV130, a complex mix of heat-killed bacteria. Based on these examples, we investigated whether heat-killed mycobacteria could also trigger TI. To assess the validity of this hypothesis, we selected a commercially available preparation of HKMtb for a prototypical in vitro long-term TI experiment.1 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were exposed to β-glucan (as a standard TI inducer) or HKMtb. After 1 day, stimuli and non-adherent cells were washed out, and adherent cells rested in a complete medium for 5 days. A flow cytometry analysis of these cultures confirmed that they were primarily CD14+ monocytes/macrophages (≈90%) (Figure S1A). Next, the medium was removed and the cells were stimulated with a panel of pathogen-associated molecular patterns, including LPS as a TLR4 ligand, R848 as a TLR7/8 ligand, Pam3CSK4 as a TLR2 ligand, and CpG as a TLR9 ligand. The production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in the supernatants was analyzed to evaluate the training process (Figure 1A). Note that the 2 latter stimuli produced negligible amounts of this proinflammatory cytokine, independent of pretreatment with either β-glucan or HKMtb (data not shown). As a control, β-glucan training generated increased TNF-α production upon restimulation (Figure S1B), confirming the performance of our model. Next, HKMtb-pretreated monocytes showed a robust enhanced TNF-α production in response to both LPS and R848 (Figure 1B), suggesting that the mycobacterial preparation induced TI.

Figure 1.

Heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces trained immunity

(A) Trained immunity in vitro model in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Created with BioRender.com.

(B and C) PBMCs were trained with 10 μg/mL (B) or the indicated concentrations (C) of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) for 1 day, washed, and left to rest for 5 days. After washing, remaining adherent monocytes were rechallenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (TLR4 ligand) (left panels) or R848 (TLR7/8) (right panels) for another day; supernatants were collected, and TNF-α was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).Each dot represents an independent donor. (B) N = 4, n = 12. Paired Student’s t test comparing control (not trained) versus trained cells. (C) N = 3, n = 6–9. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Paired Student’s t test comparing control (not trained) versus trained cells or non-treated (Ø) versus LPS or R848 stimulation, and (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). See also Figure S1.

At this stage, we evaluated whether the training effect induced by HKMtb depended on its concentration. A titration experiment was conducted, using HKMtb concentrations ranging from 1 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL. Note that the experiments shown in Figure 1B were performed with 10 μg/mL concentrations. As shown in Figure 1C and 1A robust TI was only revealed against LPS at 10 μg/mL, whereas boosted TNF-α production upon secondary R848 stimulation was detected at both 10 and 1 μg/mL of HKMtb. Interestingly, β-glucan-induced training was comparable across a wide range of concentrations (Figure S1C). Therefore, considering these results, 10 μg/mL of HKMtb was employed as the training stimulus for the subsequent experiments.

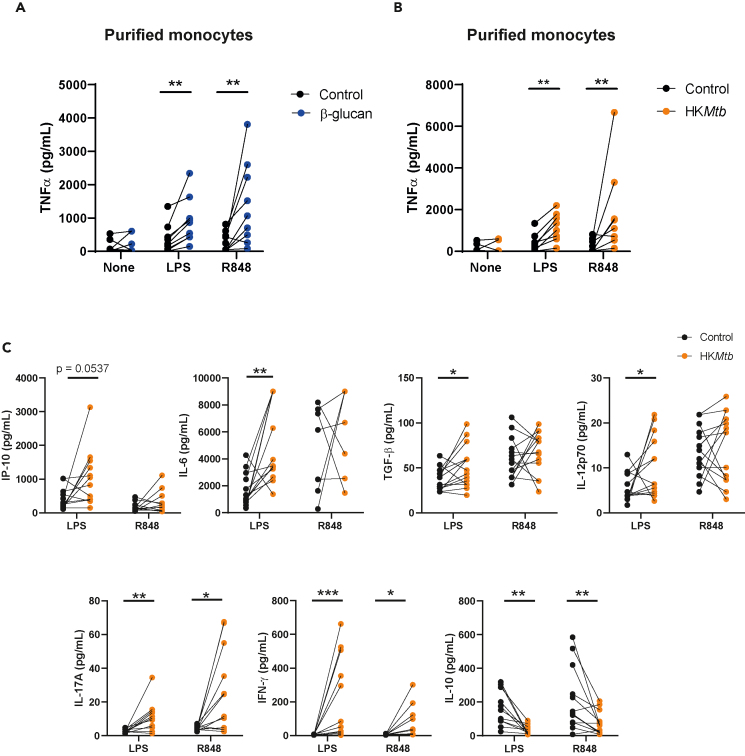

Following our previous study,8 our aim with regard to the training stimulations of total PBMCs was to perform these challenges under more native conditions, maintaining the blood’s full mononuclear cellular environment. Afterward, the washing step removes non-adherent cells, primarily leaving adherent monocytes/macrophages (Figure S1A) to be secondarily stimulated. Nonetheless, to confirm that the observed training effects were intrinsic to monocytes, these cells were magnetically purified from PBMCs and subjected to the in vitro training scheme. As shown in Figures 2A and 2B, β-glucan as well as HKMtb induced increased TNF-α production in purified monocytes following both LPS and R848 secondary stimulation.

Figure 2.

Heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a robust trained immunity response against lipopolysaccharide and R848

(A and B) Monocytes were magnetically purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), plated, and subjected to the protocol indicated in Figure 1A. Ten μg/mL of both β-glucan and heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) were used as training stimuli, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or R848 as secondary challenge. TNF-α was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

(C) PBMCs were trained with 10 μg/mL of HKMtb following the protocol indicated in Figure 1A, rechallenging with LPS or R848. Supernatants were collected, and a panel of cytokines was analyzed by a multiparametric cytokine determination kit. Each dot represents an independent donor. (A, B) N = 3, n = 9. (C) N = 6, n = 14. Paired Student’s t test comparing control (not trained) versus trained cells. (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Specific p value is shown for clarification.

To further explore the TI process induced by HKMtb, a broad panel of cytokines was analyzed after training with the mycobacterial stimulus and secondary rechallenge with either LPS or R848. Cytokines such as inducible protein-10 (IP-10), interleukin (IL)-6, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, and IL-12p70 were upregulated in response to LPS upon HKMtb-trained conditions, whereas IL-17A and interferon (IFN)-γ production was enhanced following both LPS and R848 (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the levels of the immunoregulatory cytokine IL-10 were downregulated in HKMtb-trained cells after restimulation (Figure 2C), reinforcing the proinflammatory trained phenotype generated after training with HKMtb.

Altogether, these data demonstrate that HKMtb induces TI in human monocytes, with a specific profile of response against secondary heterologous challenges.

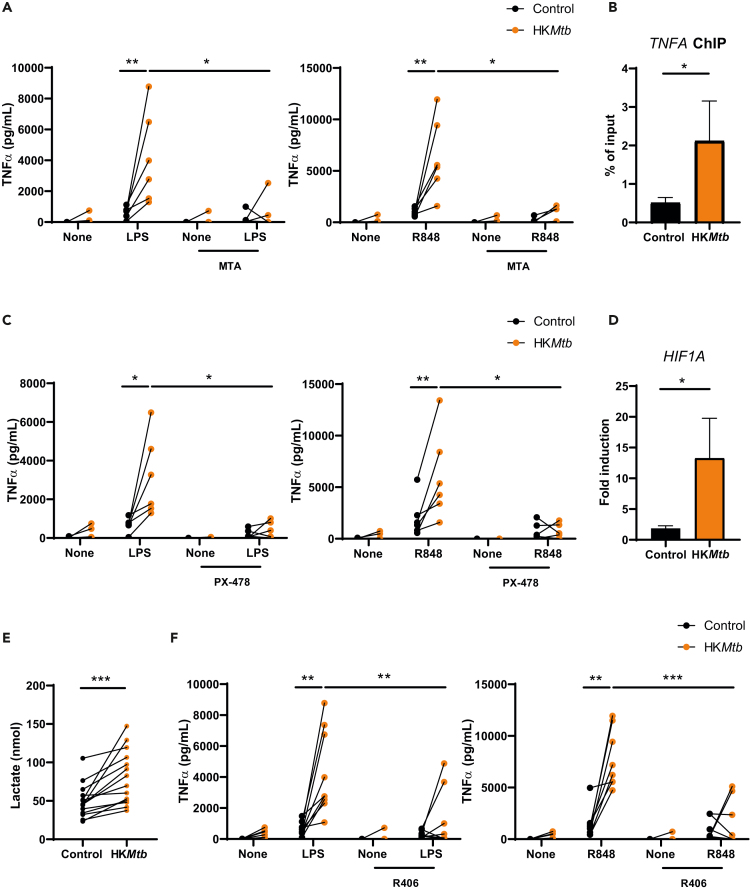

HKMtb-induced TI relies on epigenetic reprogramming, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, and Syk kinase

The epigenetic reprogramming generated by the training stimulus constitutes the underlying mechanism responsible for the long-term trained process.2 To assess the ability of epigenetic rewiring to sustain HKMtb-induced TI, we used the methyltransferase inhibitor 5′-deoxy-5’-(methylthio) adenosine (MTA), a widely accepted TI regulator.1,8 Preincubation of PBMCs with MTA dampened HKMtb-induced TI in response to both LPS and R848 (Figure 3A). To further confirm the generation of an epigenetic rewiring by HKMtb stimulation, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays capturing trimethyl-Histone H3 activating residue on the TNFA promoter3 showed enrichment following HKMtb training (Figure 3B). These results confirmed that TI induced by HKMtb depends on epigenetic reprogramming.

Figure 3.

Heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced trained immunity relies on epigenetic reprogramming, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, and Syk kinase

(A, C, and F) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were incubated with the methyltransferase inhibitor 5′-deoxy-5’-(methylthio) adenosine (MTA) (A), the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α inhibitor PX-478 (C), and the Syk inhibitor R406 (F) before training with heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) for 1 day. Cells were then washed and left to rest for 5 days. Remaining adherent monocytes were washed and rechallenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or R848 for another day, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α in the supernatants was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

(B, D and E) PBMCs were trained with HKMtb for 1 day. Cells were then washed and left to rest for 5 days (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed against trimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys4), analyzing the enrichment of this residue at the TNFA promoter by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). (D) Total RNA was extracted and HIF1A expression was analyzed by qPCR. (E) Supernatants were collected, and lactate was analyzed by a colorimetric assay. Each dot represents an independent donor. (A–D, F) N = 2–3, n = 6–9. (E) N = 6, n = 14. (B, D) Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Paired Student’s t test comparing control (not trained) versus trained cells or exposed versus not exposed to the various inhibitors (A, C, F). (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

HIF-1α is critical for the innate training process induced by β-glucan.3 To address whether the activity of this transcription factor is relevant for the TI induced by HKMtb, we employed the HIF-1α-specific inhibitor, PX-478.32 Based on this experimental approach, we observed a significant impairment of HKMtb-induced TI after secondary stimulation with both LPS and R848 when PBMCs were pretreated with PX-478 (Figure 3C), indicating the role of HIF-1α in HKMtb-induced training. Importantly, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analyses showed a clear induction on the expression of this transcription factor following HKMtb training (Figure 3D), further illustrating that HKMtb-induced TI relies on HIF-1α.

As previously mentioned, metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis is also critical for the induction of TI in myeloid cells.4 Lactate production following HKMtb training was analyzed as a subrogate of glycolytic metabolism, showing a clear increase (Figure 3E). Thus, these data indicate that HKMtb induces TI, involving metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming and HIF-1α. Moving upstream, HKMtb is known to be recognized by the C-type lectin receptor (CLR), macrophage inducible C-type lectin (Mincle),33 triggering a primary signaling pathway involving the proximal adaptor Syk.34 To explore whether HKMtb-induced TI relied on this signaling module, we used the Syk inhibitor, R406.35 HKMtb-induced TI was impaired by Syk inhibition upon both LPS and R848 rechallenge (Figure 3F), indicating that HKMtb-induced TI depends on Syk kinase, most probably through the Mincle receptor.

Altogether, these mechanistic results indicate that epigenetic reprogramming underlies HKMtb-induced TI in an HIF-1α- and Syk-dependent manner, also involving a glycolytic switch, independent of the secondary heterologous stimuli.

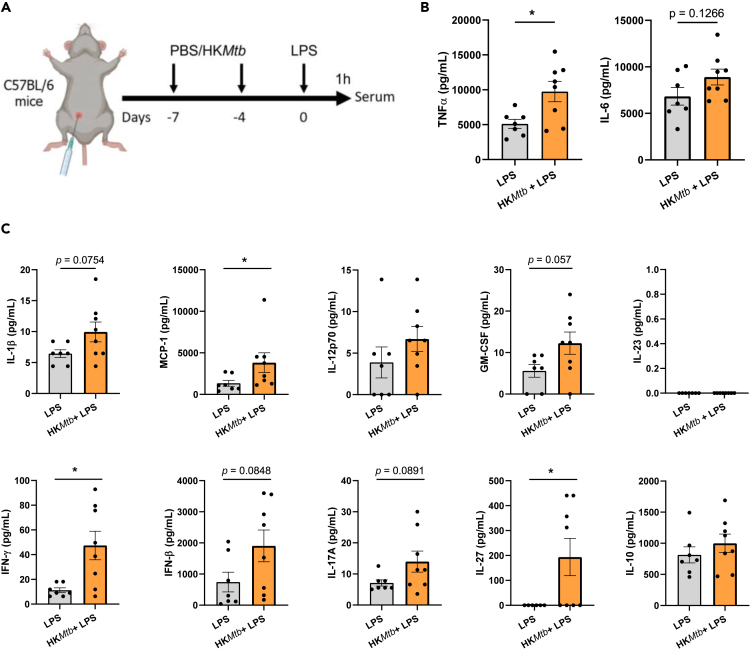

In vivo systemic administration of HKMtb induces TI

Once we had established that HKMtb induces TI in vitro, we examined its training capabilities in vivo. Intraperitoneal injection of β-glucan is a well-established administration route resulting in TI induction.1,3 We adopted this schedule to test whether HKMtb ignites a boosted inflammatory reaction against systemic heterologous LPS administration (Figure 4A). Serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6, quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), were chosen as the main readouts. Intraperitoneal training with HKMtb generated boosted TNF-α production following LPS stimulation, with a trend in the same direction in the case of IL-6 (Figure 4B). To go deeper in this analysis, we performed a multiparametric assay to assess a panel of serum cytokines in these settings. Our findings show that HKMtb training induced higher levels of MCP-1, IFN-γ, and IL-27, with a similar trend for IL-1β, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-β, and IL-17A (Figure 4C). These data indicate that the systemic administration of HKMtb trains mice against a heterologous LPS challenge, generating a mildly enhanced proinflammatory profile.

Figure 4.

In vivo systemic administration of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces trained immunity

(A) In vivo model of training systemically by 2 intraperitoneal injections of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) or control with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by a secondary intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge for measuring serum cytokines. Created with BioRender.com.

(B) Serum tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α and interleukin (IL)-6 were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

(C) Serum IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, IL-12p70, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-23, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-β, IL-17A, IL-27, and IL-10 were analyzed by a multiparametric cytokine determination kit. (B, C) n = 7–8 mice per experimental condition. Unpaired Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney test comparing mice trained or not with HKMtb (∗p < 0.05). For clarity, some p values are indicated.

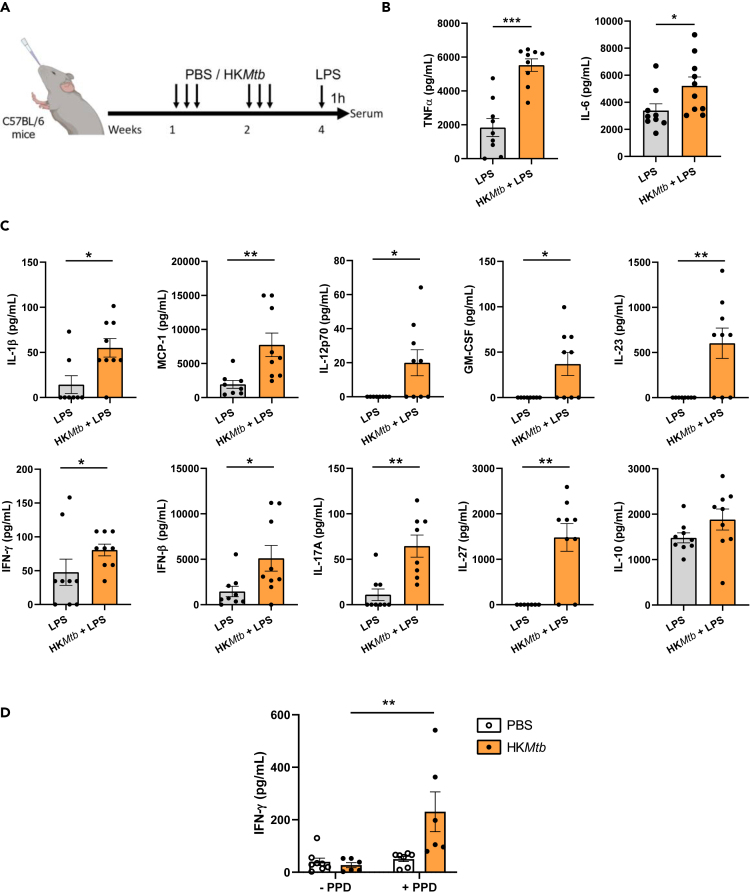

Intranasal administration of HKMtb robustly induces TI in vivo

Previously, we had demonstrated that the heat-killed polybacterial immunotherapy, MV130, consistently induces TI when administered intranasally.17,18 Therefore, we examined here whether this route of administration could also be used to induce TI with HKMtb, comparatively evaluating the potential responses with those observed upon systemic administration (see Figure 4). Mice were administered HKMtb intranasally following the schedule previously tested for MV130 (3 times per week for 2 weeks) and challenged with LPS 1 week after the last HKMtb inoculation (Figure 5A). As previously performed, serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6, analyzed by ELISA, were chosen as the primary endpoints. Levels of both proinflammatory cytokines were enhanced in those mice trained with HKMtb (Figure 5B). Furthermore, the multiparametric serum analysis indicated a general and robust increase in the amount of proinflammatory cytokines detected in the HKMtb-trained mice, with higher levels of virtually all cytokines, except the immunomodulatory cytokine IL-10 (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Intranasal administration of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis robustly induces trained immunity in vivo

(A) In vivo model of intranasal training. Mice were intranasally administered with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (HKMtb) 3 times per week for 2 weeks. After a resting week, the mice were exposed to a secondary intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge for measuring serum cytokines. Created with BioRender.com.

(B) Serum tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α and interleukin (IL)-6 were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

(C) Serum IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, IL-12p70, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-23, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-β, IL-17A, IL-27 and IL-10 were analyzed by a multiparametric cytokine determination kit.

(D) Mice were intranasally administered HKMtb or PBS as indicated in panel A. Following the 1-week resting period and before lipopolysaccharide stimulation, the mice were euthanized, and spleens recovered. Single-cell suspensions were plated and re-stimulated or not with the purified protein derivative (PPD). Three days afterward, supernatants were collected and IFN-γ analyzed by ELISA. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. (B,C) n = 6–9 mice per experimental condition. Unpaired Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney test comparing mice trained or not with HKMtb (B, C) or restimulated or not with PPD (D) (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). See also Figure S2.

Considering the high proinflammatory profile observed with the intranasal HKMtb administration scheme, we sought signs of potential autoimmune reactions. To this end, we analyzed the impact of HKMtb-mediated training on some steady-state inflammatory features, in the absence of secondary LPS stimulation. No signs of splenomegaly were found in the HKMtb-trained mice at the end of the 3-week training period (Figure S2A), nor did we find basal levels of circulating TNF-α (Figure S2B). These data indicate that the trained status generated by intranasal HKMtb administration is not accompanied by a proinflammatory profile unless a secondary stimulation takes place.

Considering the potential clinical application of HKMtb-induced trained responses, we evaluated whether this training generated positive reactions when employing the gold-standard method to identify an exposure to Mycobacterium. Thus, we tested purified protein derivative (PPD)-specific responses by exposing splenocytes to tuberculin obtained from Mycobacterium tuberculosis.36 The production of IFN-γ was evaluated in an IFN-γ release assay (IGRA).36 As shown in Figure 5D, HKMtb intranasal training conferred positive responses against PPD.

In summary, the administration of HKMtb through the intranasal route confers a robust trained response in vivo, with no apparent autoimmune symptoms and trackable by PPD test.

Discussion

The heterologous nature of TI is opening new opportunities in vaccinology, promoting the development of TI-based vaccines (TIbVs), which are defined as vaccine formulations that seek the induction of TI in innate immune cells.28 The goal of these vaccines, unlike conventional formulations based on antigens plus adjuvant, is the priming of proinflammatory responses against a broad spectrum of heterologous insults, mainly infections.37,38 The potential application of these formulations would be the generation of a broad prophylaxis against pathogens lacking specific vaccination, or even to improve the protection conferred by antigen-specific vaccines.28 This concept was applied during the COVID-19 pandemic before severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-specific vaccines were developed.18,39

The growing clinical relevance of these training processes has sparked an urgency to identify and apply new TI inducers in clinical settings. Herein, we describe that a commercially available preparation of HKMtb induces TI, both in human monocytes in vitro and in mouse in vivo models. As mentioned in the Introduction, other mycobacteria, such as BCG, are the gold-standard stimuli to induce TI, both in vitro12 and in vivo in humans.13,14 Nevertheless, the use of HKMtb as a TI inducer provides some advantages over BCG. The key differentiating factor is the use of metabolically inactive (killed) mycobacteria instead of live-attenuated mycobacteria, such as BCG. This difference is relevant because the use of heat-killed bacteria to induce TI overcomes some of BCG’s limitations. For instance, it avoids the risk of infection due to uncontrolled bacterial growth in immunodeficient patients.26 In addition, the logistic and clinical handling of heat-killed bacteria would be much easier, facilitating its distribution and implementation. Furthermore, our data indicate that HKMtb induces TI through the airways, opening the possibility to be self-administered by patients as a nasal or sublingual spray, as occurs with MV130.27

An alternative heat-killed mycobacterium included in a food supplement, Mycobacterium manresensis, has also been described as an in vitro TI inducer.31 In these experiments, Percoll-purified adherent mononuclear cells after CD3 lymphocyte depletion were employed, reaching almost 80% of CD14+ monocytes/macrophages.31 Note, IFN-γ from lymphocytes has been described as responsible for TI induction in monocytes following a Plasmodium falciparum encounter.40 Along these lines, we initially trained total PBMCs, aiming to reproduce the encounter of blood circulating mononuclear immune cells with HKMtb as a training stimulus, revealing the trained phenotype in adherent monocytes upon secondary heterologous stimulations. Thus, our initial setting did not allow us to discriminate a potential cooperation between lymphocytes and monocytes for the generation of the HKMtb-mediated trained response. To clarify this concern, monocytes cells were magnetically purified from total PBMCs and trained with HKMtb, confirming that the mycobacterial preparation trains isolated monocytes in a cell-intrinsic manner.

To reach potential clinical applications, it is important to understand the molecular mechanisms implicated in HKMtb-induced TI. Based on our findings, we can determine a signaling pathway implicating Syk/HIF-1α leading to epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming. Syk kinase is a proximal molecule implicated in the signaling triggered by most of the activating CLRs34,41; among these receptors, Dectin-1 is key to inducing TI in response to the prototypical inducer β-glucan, also activating HIF-1α.3 According to our data, Syk participates in the induction of TI by HKMtb, suggesting that this kinase is shared for the direct and the training-related signaling pathway, most probably downstream Mincle.33 Of note, the scaffold protein FcRγ is necessary for the signaling triggered by downstream Mincle, leading to Syk activation.34,41 This feature suggests that other FcRγ-coupled CLRs activating Syk might also induce TI.

Resiquimod, the commercial name for R848, has been extensively tested as a vaccine adjuvant in various contexts, such as experimental protein-based vaccine candidates,42 or antiviral or antitumor vaccines.43,44 One of the aims of TIbV is to improve the immunogenic responses of antigen-specific vaccines,28 due to either low vaccine immunogenicity or poor target population response, for instance, in the elderly. In this context, the administration of TIbV in a prophylactic manner (we postulate HKMtb in this case) would be necessary before administering vaccine formulations containing Resiquimod as an adjuvant. We have observed this regimen improving antigen-specific responses when combining MV130-induced TI and COVID-19 vaccination.18 Thus, our results raise the possibility of combining training with HKMtb with vaccines harboring Resiquimod as an adjuvant, thereby improving the immunogenicity of those vaccine formulations.

The epigenetic proinflammatory profile imprinted during the development of TI could also have detrimental effects due to uncontrolled inflammatory responses, potentially leading to autoimmunity.30 In this sense, HKMtb training alone did not lead to substantial TNF-α production in the long term in human adherent monocytes in the absence of secondary stimulation. Additionally, neither splenomegaly nor circulating TNF-α was found in steady-state HKMtb-trained mice at the end of the 3-week scheme of intranasal administration. These results suggest a lack of uncontrolled proinflammatory reactions due to the exposure to HKMtb, although this aspect would need to be further addressed in clinical settings, as would the possibility that intranasal administration of HKMtb could generate PPD-specific responses.

Importantly, we have observed that HKMtb induces TI in vivo when administered both systemically through the intraperitoneal route and intranasally. Nevertheless, the trained response was more robust when the mucosal intranasal route of administration was chosen, given that we detected enhanced production of virtually all the analyzed cytokines, except IL-10, against the heterologous challenge. Notably, in one clinical trial, the oral administration of alternative heat-killed mycobacteria included in a food supplement, Mycobacterium manresensis, did not induce TI, despite generating the trained process in vitro.31 This discrepancy points to the route of administration as a decisive factor to be considered for the induction of TI-based protective responses triggered by these mycobacterial preparations, as suggested by the effectiveness of BCG against SARS-CoV-2 infection when mice are vaccinated intravenously instead of subcutaneously.20

Focusing on the strong induction of TI following intranasal administration of HKMtb, there are several examples of the power of this route for triggering TI. We have observed that the mucosal polybacterial immunotherapy MV130 confers protection against viral and fungal infection when provided through the airways.17,18 Indeed, successful results against pathologies of infectious etiology have been observed in clinical settings using MV130 when administered sublingually,27,45 indicating the effectiveness of the airway mucosae for the induction of TI. Along these lines, the induction of TI by BCG or the alternative Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine, MTBVAC, was stronger when non-human primates were vaccinated through the lung mucosae than intradermally.22 The exploitation of the intranasal route to administer immunomodulators of various types has been proposed as an effective approach to trigger antitumor immunity,46 as well as to generate potent antigen-specific responses47 that are comparatively stronger than, for example, subcutaneous vaccination.48 In addition, despite preclinical data suggesting that intragastric administration of β-glucans could improve antitumor responses,49,50 suggestive of heterologous TI,51,52 no enhanced innate immune responses were observed in a controlled clinical trial in which participants ingested β-glucan once daily for 7 days.53 Altogether, these data suggest the great potential of the intranasal route of administration to trigger potent TI responses.

Nonetheless, we can only speculate about the cellular mechanisms underlying this better TI induction through the airways because the current knowledge in this sense is scarce. A longer persistence in the airways of the training stimulus could play a role, perhaps due to a limited capacity of removal compared with the peritoneum in the case of intraperitoneal administration, or the liver when administering the training stimulus directly into the bloodstream. An alternative explanation would be the direct stimulation of TI-prone myeloid cells in the lungs, postulating a preponderant role for alveolar or interstitial macrophages in the lungs. Along these lines, MV130-induced intranasal TI is CCR2 independent,17 suggesting that the recruitment of monocytes from the bone marrow is not required to confer heterologous protection, pointing to local lung-resident populations.

In summary, we have herein described the capacity of HKMtb to induce TI in vitro through epigenetic rewiring in a Syk/HIF-1α-dependent manner, leading to enhanced heterologous responses against LPS and R848. HKMtb induces TI in vivo as well, administered both systemically and intranasally, with the latter generating more robust proinflammatory trained responses. The presented data suggest an avenue whereby this immunotherapy could be deployed in pathophysiological contexts that require protective inflammatory responses.

Limitations of the study

The lack of a parallel comparison between HKMtb and Mycobacterium manresensis in the in vivo settings studied in this work (systemic and intranasal administration) represents a limitation of the study. Nevertheless, conclusions regarding this topic have been made strictly based on the provided experimental data and were only further extended in the discussion section based on solid references.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| CD3 – BV510 | Biolegend | Cat# 317332; RRID: AB_2561943 |

| CD14 - SparkBlue550 | Biolegend | Cat# 367148; RRID: AB_2820021 |

| CD56 – BV750 | Biolegend | Cat# 362556; RRID: AB_2801001 |

| ChIPAb+ Trimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys4) | Millipore | Cat# 17-614; RRID: AB_11212770 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Blood samples of healthy health personnel | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ficoll-Plus | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17-1440-03 |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11594506 |

| Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) | Sigma | Cat# P4417-100TAB |

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11560636 |

| Pharm Lyse Lysing Buffer | BD | Cat# 555899 |

| Penicillin Streptomycin | Gibco | Cat# 15140-148 |

| Whole glucan particles | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-wgp |

| Heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-hkmt |

| Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# L4391 |

| R848 (Resiquimod) | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-r848 |

| Pam3CSK4 | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-pms |

| CpG ODN 2216 | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-2216 |

| 5′-Deoxy-5′-(methylthio) adenosine (MTA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D5011 |

| PX-478 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-10231 |

| R406 free base | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-11108 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Human TNF-alpha DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# DY210 |

| Mouse TNF-alpha DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# DY410 |

| Mouse IL-6 DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# DY406 |

| Mouse IFNγ DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# DY485 |

| KPL SureBlue TMB Microwell Substrate | Seracare | Cat# 5120-0076 |

| LEGENDplex Mouse Inflammation Panel (13-plex) with Filter Plate | BioLegend | Cat# 740150 |

| LEGENDplex human Essential Immune Response Panel (13-plex) with Filter Plate | BioLegend | Cat# 740930 |

| Pan Monocyte Isolation kit | Miltenyi | Cat# 130-096-537 |

| Magna ChIP A/G | Millipore | Cat# 17-10085 |

| Monarch Total RNA Miniprep kit | New England Biolabs | Cat# T2010S |

| High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 10400745 |

| PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat# A25742 |

| Lactate Assay kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# MAK064 |

| Blue LIVE/DEAD Fixable staining | ThermoFisher | Cat# L23105 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C57BL/6 mice | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID: MSR_JAX:000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| TNFA-ChIP Forward | CAGGCAGGTTCTCTTCCTCT | N/A |

| TNFA-ChIP Reverse | GCTTTCAGTGCTCATGGTGT | N/A |

| HIF1A Forward | AGTGTACCCTAACTAGCCGAGGAA | N/A |

| HIF1A Reverse | CTGAGGTTGGTTACTGTTGGTACA | N/A |

| β-ACTIN Forward | CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC | N/A |

| β-ACTIN Reverse | CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| LEGENDplex software v.8 | Biolegend | https://www.biolegend.com/en-us/legendplex |

| Prism version 8.3 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | https://products.office.com/ |

| Biorender | Biorender.com | https://www.biorender.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Carlos del Fresno (carlos.fresno@salud.madrid.org).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Blood samples

Healthy volunteers of unspecified age and sex were recruited from the Blood Donor Service at La Paz University Hospital (Madrid, Spain). The experiments have been reviewed and approved by the La Paz University Hospital Ethics Committee (PI-5270) in the framework of the ISCIII grant PI21/01178 awarded to the PI of this project.

Mice

The mice we used were bred at the La Paz University Hospital Institute for Health Research (IdiPAZ). We employed mice from the Jackson Laboratory, mouse strain C57BL/6 (RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664), age-matched 6 to 8 weeks, regardless of sex. Otherwise, mice were included in the studies in a blinded fashion and randomly assigned to receive HKMtb or PBS/excipient (simple 1:1 randomization).

Experiments were approved by the “Dirección General de Agricultura, Ganadería y Alimentación” of Comunidad de Madrid as part of the project PROEX number 348.2/21.

Method details

Culture conditions of primary cells

Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulant (EDTA) venous blood of healthy donors were isolated by gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Cat# 17-1440-03). PBMCs were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma, Cat# P4417-100TAB) and counted by trypan blue staining. Thereafter, cells were resuspended in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 11594506) supplemented with antibiotics (0.1% penicillin and 0.1% streptomycin, Gibco, Cat# 15140-148) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 11560636) (RPMIc). PBMCs were cultured at 37 °C at 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Trained immunity in PBMCs and purified monocytes

We plated 2x105 PBMCs in 100 μL RPMIc per well in 96-well flat bottom plates. On day 0, cells were stimulated with 100 μg/mL (or the indicated concentration) of β-glucan particles (InvivoGen, Cat# tlrl-wgp) or 10 μg/mL (or the indicated concentration) HKMtb (strain H37Ra, InvivoGen, Cat# tlrl-hkmt-1) to a final volume of 200 μL of RPMIc for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed with PBS and allowed to rest for 5 days in RPMIc. On day 6, cells were washed again and further stimulated with 10 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# L4391), 10 μg/mL R848 (InvivoGen, Cat# tlrl-r848), 10 ng/mL Pam3CSK4 (P3C4) (InvivoGen, Cat# tlrl-pms), or 2,5 μM CpG (ODN p2216) (InvivoGen, Cat# tlrl-2216). After 24 h, supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C for subsequent processing. The composition of the cultures after the 5-day resting period was analyzed by flow cytometry with the Aurora 5L device (Cytek), using antibodies against CD3, (lymphocytes); CD14, (monocytes/macrophages); and CD56 (NKs).

Alternatively, monocytes were purified from PBMCs using the Pan monocyte isolation kit (Miltenyi, Cat# 130-096-537) following the manufacturer’s instructions. We plated 2x104 purified monocytes in 100 μL RPMIc per well in 96-well flat bottom plates and trained them according to the above-described workflow, using 10 μg/mL of both β-glucan and HKMtb as training stimuli.

The bacterial concentration of HKMtb was determined by flow cytometry as follows.54 Briefly, a calibration curve was prepared, using a log-phase growth culture of attenuated BCG, assuming that the whole culture was viable. Then, serial dilutions (1:2) were prepared and analyzed by flow cytometry. Bacterial viable units in the culture were calculated by plating in solid medium and counting colonies. Given that 10 μg/mL of HKMtb contains 1.4x104 heat-killed bacteria, it corresponds to a 1:0.7 ratio (monocyte/HKMtb).

In vitro stimulation and peripheral blood mononuclear cell inhibition

When required, prior to β-glucan particles or HKMtb stimulation, cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 1-mM epigenetic inhibitor 5′-Deoxy-5′-(methylthio) adenosine (MTA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# D5011), or with 3-μM Syk pathway inhibitor R406 (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-11108), or for 16 h with 15-μM HIF-1α inhibitor PX-478 (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-10231).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP)

We plated 107 PBMCs in 5 ml RPMIc per well in p100 flat-bottom plates. On day 0, cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL HKMtb to a final volume of 10 ml RPMIc for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed with PBS and allowed to rest for 5 days in RPMIc. ChIP was performed with the Magna ChIP A/G kit (Millipore) following the manufacturer’s indications. Immunoprecipitated DNA and input DNA were amplified by means of quantitative PCR with specific primers for the promoter region of TNFA.

Lactate determination

PBMCs were stimulated with 10 μg/mL of HKMtb in p96 wells as indicated before, collecting supernatants at the end of the 5-day resting period. Lactate was quantified in these supernatants (diluted 1/10) with the colorimetric assay Lactate Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

HIF1A expression

We plated 107 PBMCs in 1 mL RPMIc per well in p6-well flat-bottom plates. On day 0, the cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL HKMtb to a final volume of 2 ml RPMIc, for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed with PBS and allowed to rest for 5 days in RPMIc. At the end of the 5-day resting period, total RNA was extracted by means of the Monarch Total RNA Miniprep kit (New England Biolabs). The cDNA was prepared with the High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR was performed with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and primers for β-ACTIN and HIF1A. mRNA levels were normalized to β-ACTIN expression.

In vivo models of trained immunity

In one experiment, following a well-established in vivo trained immunity model,3,8 mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 125 μg HKMtb (8.75x105 bacteria) or PBS alone (as a control) on days -7 and -4. One week later, the mice were challenged i.p. with 5 μg E. coli lipopolysaccharide serotype O111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# L4391) diluted in sterile PBS; 60 min later, blood was collected, clotted, and centrifuged, and serum was frozen at −20°C for subsequent analyses.

In another experiment, to evaluate an alternative administration route, mice were intranasally (i.n.) challenged with 12.5 μg HKMtb (8.75x104 bacteria) or PBS 3 times a week for 2 weeks. One week after the last challenge, the mice were intraperitoneally administered 5 μg E. coli lipopolysaccharide diluted in sterile PBS. Blood was collected 60 min later, and serum was frozen at −20°C for subsequent analyses.

Purified protein derivative assay

After intranasal administration of HKMtb according to the previous section, mice were euthanized before lipopolysaccharide rechallenge. Spleens were collected and single-cell suspensions prepared under sterile conditions. We plated 106 total splenocytes in U-bottom 96-well plates for 3 days, exposed or not to purified protein derivative (PPD), kindly provided by Dr. Aguiló. Supernatants were collected and IFN-γ analyzed by ELISA.

Cytokine measurement

A commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Cat# DY210) was used to determine TNF-α concentration in cell culture supernatant samples from human donors. The manufacturer’s instructions were followed to determine these concentrations.

The remaining cytokines (IL-4, IL-2, CXCL10 [IP-10], IL-1β, CCL2 [MCP-1], IL-17A, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-12p70, CXCL8 [IL-8], TGF-β1 [Free Active Form]) were measured in culture supernatants with the LEGENDplex human Essential Immune Response Panel (BioLegend, Cat# 740930), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, plasma samples were incubated with premixed capture antibody-coated beads, washed, incubated with detection antibodies and streptavidin with phycoerythrin conjugate, acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD), and analyzed with Biolegend v8.0 software (Biolegend). Cytokines shown represent those whose detection was within the quantification range of the assay.

An ELISA kit was also used to determine TNF-α (R&D Systems, Cat# DY410) and IL-6 (R&D Systems, Cat# DY406) concentrations in mouse serum. The manufacturer’s instructions were followed to determine these concentrations.

The remaining cytokines (IL-1β, MCP-1, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, IL-23, IFN-γ, IFN-β, IL-17A, IL-27, and IL-10) were measured in mouse serum samples with the LEGENDplex Mouse Inflammation Panel, following the manufacturer’s instructions (BioLegend, Cat# 740150).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Outliers were identified by means of a ROUT test. The D’Agostino–Pearson Normality test was performed for all the studied variables. We performed Student’s t-test for 2 group comparisons of quantitative variables, either unpaired (t-test or Mann–Whitney) or paired (t-test or Wilcoxon). Only statistically significant differences were denoted, or p-values that might be visually confusing based on the charts. P-values are denoted as ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.01, ∗∗∗p<0.001 and explained in figure legends. In these figure legends, "N" represents the number of independent experiments performed and "n" the number of individuals included in the experiment shown, illustrated with single dots throughout. Prism Software was used to perform all the statistical analyses.

Acknowledgments

The laboratory of CdF is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the projects CP20/00106 and PI21/01178 and co-funded by the European Union, Fundación para la Investigación Biomédica Hospital la Paz (FIBHULP - Luis Álvarez 2021), Scientific Foundation of the Spanish Association Against Cancer (IDEAS222745DELF), Fundación Familia Alonso, Comunidad de Madrid (CAM) (IND2022-BMD-23669), and Inmunotek. P.M.-M. and J.F.-P. are funded by Consejería de Educación y Universidades (CAM). L.M. is funded by ISCIII, Sara Borrel program (CD22/00042). L.B. and G.B. are funded by the European Union, NextGenerationEU.

Author contributions

C.d.F. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. L.M., M.B.-G., P.M.-M., J.F.-P., V.T., L.B.-R., G.B., and G.Z.-F. performed the experiments. N.A. performed critical analyses and provided essential reagents. N.A., E.L.-C., and C.d.F. discussed the results. All the authors have read, reviewed, and agreed to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 11, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.108869.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Quintin J., Saeed S., Martens J.H.A., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Ifrim D.C., Logie C., Jacobs L., Jansen T., Kullberg B.-J., Wijmenga C., et al. Candida albicans Infection Affords Protection against Reinfection via Functional Reprogramming of Monocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Netea M.G., Domínguez-Andrés J., Barreiro L.B., Chavakis T., Divangahi M., Fuchs E., Joosten L.A.B., van der Meer J.W.M., Mhlanga M.M., Mulder W.J.M., et al. Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:375–388. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng S.-C., Quintin J., Cramer R.A., Shepardson K.M., Saeed S., Kumar V., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Martens J.H.A., Rao N.A., Aghajanirefah A., et al. mTOR- and HIF-1α–mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014;345:1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penkov S., Mitroulis I., Hajishengallis G., Chavakis T. Immunometabolic Crosstalk: An Ancestral Principle of Trained Immunity? Trends Immunol. 2019;40:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mata-Martínez P., Bergón-Gutiérrez M., del Fresno C. Dectin-1 Signaling Update: New Perspectives for Trained Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.812148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodridge H.S., Reyes C.N., Becker C. a, Katsumoto T.R., Ma J., Wolf A.J., Bose N., Chan A.S.H., Magee A.S., Danielson M.E., et al. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse. Nature. 2011;472:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith A.J., Graves B., Child R., Rice P.J., Ma Z., Lowman D.W., Ensley H.E., Ryter K.T., Evans J.T., Williams D.L. Immunoregulatory Activity of the Natural Product Laminarin Varies Widely as a Result of Its Physical Properties. J. Immunol. 2018;200:788–799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saz-Leal P., del Fresno C., Brandi P., Martínez-Cano S., Dungan O.M., Chisholm J.D., Kerr W.G., Sancho D. Targeting SHIP-1 in Myeloid Cells Enhances Trained Immunity and Boosts Response to Infection. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalafati L., Kourtzelis I., Schulte-Schrepping J., Li X., Hatzioannou A., Grinenko T., Hagag E., Sinha A., Has C., Dietz S., et al. Innate Immune Training of Granulopoiesis Promotes Anti-tumor Activity. Cell. 2020;183:771–785.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinnijenhuis J., Quintin J., Preijers F., Joosten L.A.B., Ifrim D.C., Saeed S., Jacobs C., van Loenhout J., de Jong D., Stunnenberg H.G., et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17537–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J., Gao L., Wu X., Fan Y., Liu M., Peng L., Song J., Li B., Liu A., Bao F. BCG-induced trained immunity: history, mechanisms and potential applications. J. Transl. Med. 2023;21:106. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-03944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arts R.J.W., Carvalho A., La Rocca C., Palma C., Rodrigues F., Silvestre R., Kleinnijenhuis J., Lachmandas E., Gonçalves L.G., Belinha A., et al. Immunometabolic Pathways in BCG-Induced Trained Immunity. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2562–2571. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arts R.J.W., Moorlag S.J.C.F.M., Novakovic B., Li Y., Wang S.-Y., Oosting M., Kumar V., Xavier R.J., Wijmenga C., Joosten L.A.B., et al. BCG Vaccination Protects against Experimental Viral Infection in Humans through the Induction of Cytokines Associated with Trained Immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:89–100.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirovic B., de Bree L.C.J., Groh L., Blok B.A., Chan J., van der Velden W.J.F.M., Bremmers M.E.J., van Crevel R., Händler K., Picelli S., et al. BCG Vaccination in Humans Elicits Trained Immunity via the Hematopoietic Progenitor Compartment. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:322–334.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buffen K., Oosting M., Quintin J., Ng A., Kleinnijenhuis J., Kumar V., van de Vosse E., Wijmenga C., van Crevel R., Oosterwijk E., et al. Autophagy Controls BCG-Induced Trained Immunity and the Response to Intravesical BCG Therapy for Bladder Cancer. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cirauqui C., Benito-Villalvilla C., Sánchez-Ramón S., Sirvent S., Diez-Rivero C.M., Conejero L., Brandi P., Hernández-Cillero L., Ochoa J.L., Pérez-Villamil B., et al. Human dendritic cells activated with MV130 induce Th1, Th17 and IL-10 responses via RIPK2 and MyD88 signalling pathways. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018;48:180–193. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandi P., Conejero L., Cueto F.J., Martínez-Cano S., Dunphy G., Gómez M.J., Relaño C., Saz-Leal P., Enamorado M., Quintas A., et al. Trained immunity induction by the inactivated mucosal vaccine MV130 protects against experimental viral respiratory infections. Cell Rep. 2022;38 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.del Fresno C., García-Arriaza J., Martínez-Cano S., Heras-Murillo I., Jarit-Cabanillas A., Amores-Iniesta J., Brandi P., Dunphy G., Suay-Corredera C., Pricolo M.R., et al. The Bacterial Mucosal Immunotherapy MV130 Protects Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Improves COVID-19 Vaccines Immunogenicity. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:748103–748112. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufmann E., Sanz J., Dunn J.L., Khan N., Mendonça L.E., Pacis A., Tzelepis F., Pernet E., Dumaine A., Grenier J.C., et al. BCG Educates Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Generate Protective Innate Immunity against. Tuberculosis. Cell. 2018;172:176–182.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilligan K.L., Namasivayam S., Clancy C.S., O’Mard D., Oland S.D., Robertson S.J., Baker P.J., Castro E., Garza N.L., Lafont B.A., et al. Intravenous administration of BCG protects mice against lethal SARS-CoV-2 challenge. J. Exp. Med. 2022;219:2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.20211862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derrick S.C., Kolibab K., Yang A., Morris S.L. Intranasal Administration of Mycobacterium bovis BCG Induces Superior Protection against Aerosol Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Mice. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:1443–1451. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00394-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vierboom M.P.M., Dijkman K., Sombroek C.C., Hofman S.O., Boot C., Vervenne R.A.W., Haanstra K.G., van der Sande M., van Emst L., Domínguez-Andrés J., et al. Stronger induction of trained immunity by mucosal BCG or MTBVAC vaccination compared to standard intradermal vaccination. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García González L.A., Arrutia Díez F. Mucosal bacterial immunotherapy with MV130 highly reduces the need of tonsillectomy in adults with recurrent tonsillitis. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019;15:2150–2153. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1581537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guevara-Hoyer K., Saz-Leal P., Diez-Rivero C.M., Ochoa-Grullón J., Fernández-Arquero M., Pérez de Diego R., Sánchez-Ramón S. Trained immunity based-vaccines as a prophylactic strategy in common variable immunodeficiency. A proof of concept study. Biomedicines. 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8070203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Puffelen J.H., Keating S.T., Oosterwijk E., van der Heijden A.G., Netea M.G., Joosten L.A.B., Vermeulen S.H. Trained immunity as a molecular mechanism for BCG immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020;17:513–525. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange C., Aaby P., Behr M.A., Donald P.R., Kaufmann S.H.E., Netea M.G., Mandalakas A.M. 100 years of Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022;22:e2–e12. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieto A., Mazón A., Nieto M., Calderón R., Calaforra S., Selva B., Uixera S., Palao M.J., Brandi P., Conejero L., et al. Bacterial Mucosal Immunotherapy with MV130 Prevents Recurrent Wheezing in Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021;204:462–472. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0520OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Ramón S., Conejero L., Netea M.G., Sancho D., Palomares Ó., Subiza J.L. Trained Immunity-Based Vaccines: A New Paradigm for the Development of Broad-Spectrum Anti-infectious Formulations. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mora V.P., Loaiza R.A., Soto J.A., Bohmwald K., Kalergis A.M. Preprint at Elsevier Ltd; 2022. Involvement of Trained Immunity during Autoimmune Responses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mora V.P., Loaiza R.A., Soto J.A., Bohmwald K., Kalergis A.M. Involvement of trained immunity during autoimmune responses. J. Autoimmun. 2023;137 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Homdedeu M., Sanchez-Moral L., Violán C., Ràfols N., Ouchi D., Martín B., Peinado M.A., Rodríguez-Cortés A., Arch-Sisquella M., Perez-Zsolt D., et al. Mycobacterium manresensis induces trained immunity in vitro. iScience. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palayoor S.T., Mitchell J.B., Cerna D., DeGraff W., John-Aryankalayil M., Coleman C.N. PX-478, an inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, enhances radiosensitivity of prostate carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:2430–2437. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa E., Ishikawa T., Morita Y.S., Toyonaga K., Yamada H., Takeuchi O., Kinoshita T., Akira S., Yoshikai Y., Yamasaki S. Direct recognition of the mycobacterial glycolipid, trehalose dimycolate, by C-type lectin Mincle. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:2879–2888. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.del Fresno C., Iborra S., Saz-Leal P., Martínez-López M., Sancho D. Flexible signaling of Myeloid C-type lectin receptors in immunity and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanco-Menéndez N., Del Fresno C., Fernandes S., Calvo E., Conde-Garrosa R., Kerr W.G., Sancho D. SHIP-1 couples to the Dectin-1 hemITAM and selectively modulates reactive oxygen species production in dendritic cells in response to Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 2015;195:4466–4478. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pahal P., Pollard E.J., Sharma S. StatPearls; 2023. PPD Skin Test. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin-Cruz L., Sevilla-Ortega C., Benito-Villalvilla C., Diez-Rivero C.M., Sanchez-Ramón S., Subiza J.L., Palomares O. A Combination of Polybacterial MV140 and Candida albicans V132 as a Potential Novel Trained Immunity-Based Vaccine for Genitourinary Tract Infections. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.612269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ochoa-Grullón J., Benavente Cuesta C., González Fernández A., Cordero Torres G., Pérez López C., Peña Cortijo A., Conejero Hall L., Mateo Morales M., Rodríguez de la Peña A., Díez-Rivero C.M., et al. Trained Immunity-Based Vaccine in B Cell Hematological Malignancies With Recurrent Infections: A New Therapeutic Approach. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:611566–611569. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.611566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivas M.N., Ebinger J.E., Wu M., Sun N., Braun J., Sobhani K., Van Eyk J.E., Cheng S., Arditi M. BCG vaccination history associates with decreased SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence across a diverse cohort of healthcare workers. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI145157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crabtree J.N., Caffrey D.R., de Souza Silva L., Kurt-Jones E.A., Dobbs K., Dent A., Fitzgerald K.A., Golenbock D.T. Lymphocyte crosstalk is required for monocyte-intrinsic trained immunity to Plasmodium falciparum. J. Clin. Invest. 2022;132 doi: 10.1172/JCI139298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sancho D., Reis e Sousa C. Signaling by myeloid C-type lectin receptors in immunity and homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:491–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnston D., Bystryn J.C. Topical imiquimod is a potent adjuvant to a weakly-immunogenic protein prototype vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:1958–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crofts K.F., Holbrook B.C., D’agostino R.B., Alexander-Miller M.A. Analysis of R848 as an Adjuvant to Improve Inactivated Influenza Vaccine Immunogenicity in Elderly Nonhuman Primates. Vaccines. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/vaccines10040494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sciullo P.D., Menay F., Cocozza F., Gravisaco M.J., Waldner C.I., Mongini C. Systemic administration of imiquimod as an adjuvant improves immunogenicity of a tumor-lysate vaccine inducing the rejection of a highly aggressive T-cell lymphoma. Clin. Immunol. 2019;203:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sánchez-Ramón S., Fernández-Paredes L., Saz-Leal P., Diez-Rivero C.M., Ochoa-Grullón J., Morado C., Macarrón P., Martínez C., Villaverde V., de la Peña A.R., et al. Sublingual Bacterial Vaccination Reduces Recurrent Infections in Patients With Autoimmune Diseases Under Immunosuppressant Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.675735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang T., Zhang J., Wang Y., Li Y., Wang L., Yu Y., Yao Y. Influenza-trained mucosal-resident alveolar macrophages confer long-term antitumor immunity in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 2023;24:423–438. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan A.O., Kafai N.M., Dmitriev I.P., Fox J.M., Smith B.K., Harvey I.B., Chen R.E., Winkler E.S., Wessel A.W., Case J.B., et al. A single-dose intranasal ChAd vaccine protects upper and lower respiratory tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;183:169–184.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma C., Li Y., Wang L., Zhao G., Tao X., Tseng C.T.K., Zhou Y., Du L., Jiang S. Intranasal vaccination with recombinant receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein induces much stronger local mucosal immune responses than subcutaneous immunization: Implication for designing novel mucosal MERS vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32:2100–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung N.K.V., Modak S., Vickers A., Knuckles B. Orally administered β-glucans enhance anti-tumor effects of monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2002;51:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0321-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li B., Cai Y., Qi C., Hansen R., Ding C., Mitchell T.C., Yan J. Orally administered particulate β-glucan modulates tumor-capturing dendritic cells and improves antitumor t-cell responses in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:5153–5164. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Priem B., van Leent M.M.T., Teunissen A.J.P., Sofias A.M., Mourits V.P., Willemsen L., Klein E.D., Oosterwijk R.S., Meerwaldt A.E., Munitz J., et al. Trained Immunity-Promoting Nanobiologic Therapy Suppresses Tumor Growth and Potentiates Checkpoint Inhibition. Cell. 2020;183:786–801.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding C., Shrestha R., Zhu X., Geller A.E., Wu S., Woeste M.R., Li W., Wang H., Yuan F., Xu R., et al. Inducing trained immunity in pro-metastatic macrophages to control tumor metastasis. Nat. Immunol. 2023;24:239–254. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01388-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leentjens J., Quintin J., Gerretsen J., Kox M., Pickkers P., Netea M.G. The effects of orally administered beta-glucan on innate immune responses in humans, a randomized open-label intervention pilot-study. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esteso G., Aguiló N., Julián E., Ashiru O., Ho M.M., Martín C., Valés-Gómez M. Natural Killer Anti-Tumor Activity Can Be Achieved by In Vitro Incubation With Heat-Killed BCG. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.622995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.