Abstract

The inner membrane protein YidC is associated with the preprotein translocase of Escherichia coli and contacts transmembrane segments of nascent inner membrane proteins during membrane insertion. YidC was purified to homogeneity and co-reconstituted with the SecYEG complex. YidC had no effect on the SecA/SecYEG-mediated translocation of the secretory protein proOmpA; however, using a crosslinking approach, the transmembrane segment of nascent FtsQ was found to gain access to YidC via SecY. These data indicate the functional reconstitution of the initial stages of YidC-dependent membrane protein insertion via the SecYEG complex.

INTRODUCTION

In Escherichia coli, most secretory preproteins are translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane by a multimeric integral membrane complex termed translocase (reviewed in Manting and Driessen, 2000). Periplasmic and outer membrane proteins are synthesized with an N-terminal, cleavable signal sequence (preproteins), and stabilized in a translocation-competent state by the SecB chaperone. The SecB–preprotein complex is targeted to the peripheral subunit of the translocase, the ATPase SecA. SecA drives the translocation of the preprotein through a transmembrane pore formed by SecY, SecE and SecG (Manting et al., 2000). Insertion of most inner membrane proteins also depends on translocase, but these proteins are co-translationally targeted to the SecYEG complex by the signal recognition particle (SRP) and the SRP receptor FtsY (Luirink et al., 1994; De Gier et al., 1997; Valent et al., 1998). SRP interacts with hydrophobic transmembrane segments (TMSs) of nascent membrane proteins (Valent et al., 1995, 1997; Beck et al., 2000). Upon interaction with membrane-associated FtsY, SRP delivers the ribosome–nascent chain complex to the translocase (Valent et al., 1998). Insertion of TMSs can occur in the absence of SecA (Scotti et al., 1999; Neumann-Haefelin et al., 2000), while translocation of large periplasmic loops has been shown to require SecA (Lee et al., 1992; Andersson and von Heijne, 1993; Urbanus et al., 2001). Recently, the 60 kDa inner membrane protein YidC was identified as a translocase-associated component that interacts with TMSs of Sec-dependent inner membrane proteins during insertion (Houben et al., 2000; Samuelson et al., 2000; Scotti et al., 2000). YidC is a homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Oxa1p, which plays a crucial role in the biogenesis of some mitochondrial inner membrane proteins (He and Fox, 1997; Hell et al., 1997, 1998). Depletion of YidC in E. coli affects both Sec-dependent and Sec-independent membrane protein insertion (Samuelson et al., 2000). Here, we report the functional co-reconstitution of the E. coli YidC protein with the SecYEG complex, yielding proteoliposomes that catalyze Sec-dependent membrane protein insertion.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

YidC purifies as monomeric and dimeric forms

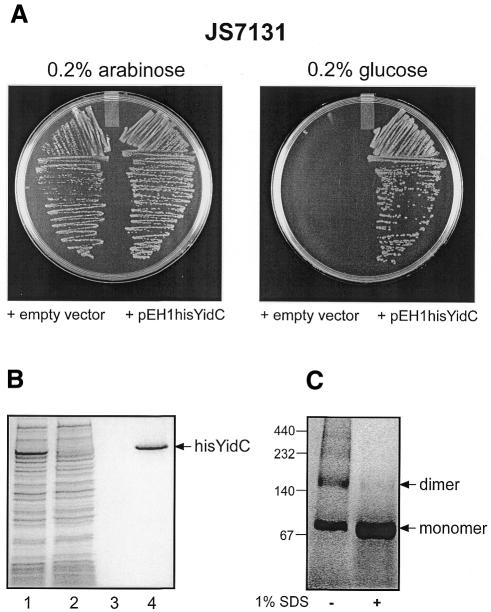

YidC is a polytopic inner membrane protein with a molecular mass of 60 kDa. To facilitate its purification, a histidine tag was introduced at the C-terminus of YidC, and the gene was placed under control of the lac promoter yielding the expression vector pEH1hisYidC. To determine whether His-tagged YidC is functional in vivo, pEH1hisYidC was transformed to the YidC depletion strain JS7131 (Samuelson et al., 2000). In this strain, the chromosomal yidC gene is disrupted and an intact yidC gene under control of the araBAD promoter has been introduced. JS7131 is not viable on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 0.2% glucose, since under these conditions expression of yidC from the araBAD promoter is tightly repressed. Transformation with pEH1hisYidC restored growth of JS7131 in the presence of glucose (Figure 1A), indicating that plasmid-encoded, His-tagged YidC is functional. For overproduction, pEH1hisYidC was transformed to strain E. coli SF100 (Baneyx and Georgiou, 1990). YidC could be overproduced to up to 10% of total membrane protein (Figure 1B, lane 1). Inner membrane vesicles (IMVs) were solubilized with dodecylmaltoside (DDM) and YidC was purified by Ni2+-NTA agarose chromatography (Figure 1B, lane 4). On Blue Native PAGE, two major bands were observed with molecular masses of ∼80 and ∼160 kDa (Figure 1C, lane 1). These two bands were also observed when YidC was solubilized and purified in Triton X-100, n-octylglucoside or Aminoxid W35 (data not shown). After pre-treatment of the sample with 1% SDS, only the 80 kDa band could be detected (Figure 1C, lane 2). Apparently, the protein purifies as a mixture of monomers and dimers. We do not know whether YidC is functional in a multimeric form. However, it is of interest to note that detergent-solubilized SecYEG complex also migrates as monomers and dimers on Blue Native PAGE (data not shown), whereas under translocation conditions, they are recruited by SecA to form a tetrameric pore (Manting et al., 2000).

Fig. 1. (A) His-tagged YidC complements YidC depletion strain E.coli JS7131. Cells containing pEH1hisYidC or the empty expression vector were grown on LB plates under conditions of induction (0.2% arabinose) or repression (0.2% glucose) of the chromosomally encoded yidC gene. (B) Purification of YidC. SDS–PAGE and CBB staining of solubilized IMVs (lane 1) and the unbound (lane 2), wash (40 mM imidazole) (lane 3) and eluted (400 mM imidazole) (lane 4) protein fractions of the Ni2+-NTA chromatography. (C) Blue Native PAGE of purified YidC. Purified YidC protein (20 µg) was pre-incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the presence or absence of 1% SDS prior to gel electrophoresis.

YidC does not affect SecA/SecYEG-mediated translocation of proOmpA into proteoliposomes

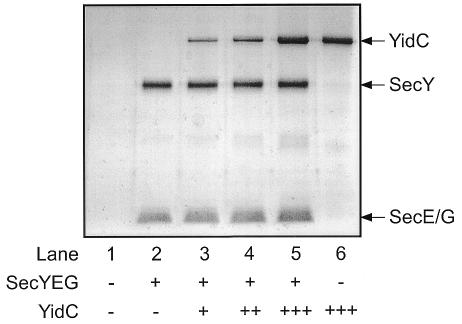

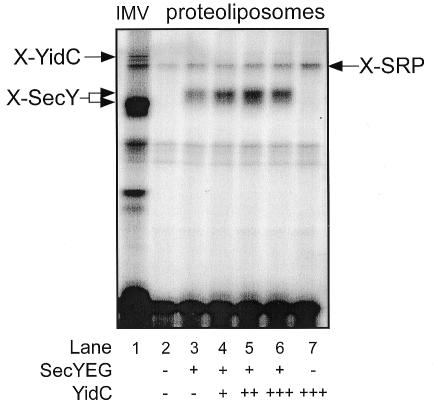

For functional studies, varying amounts of YidC were co-reconstituted with SecYEG into liposomes composed of E. coli phospholipids (Figure 2). The majority of SecYEG and YidC was stably integrated into the liposomes, as 70–80% of the protein was resistant to carbonate extraction (data not shown). To analyze the effect of YidC on the SecA-SecYEG-mediated translocation of secretory preproteins, the translocation of the precursor proOmpA was tested. Increasing amounts of YidC only slightly inhibited the translocation of proOmpA (Figure 3), and this correlated with a reduced level of the proOmpA-stimulated SecA ATPase activity (Figure 3). As expected, YidC proteoliposomes did not stimulate the SecA ATPase (Figure 3, lane 5). These results are consistent with in vivo studies (Samuelson et al., 2000) and demonstrate that YidC is not involved in proOmpA secretion.

Fig. 2. Protein profiles of proteoliposomes reconstituted with YidC and the SecYEG complex. Proteoliposomes were reconstituted with 0 (–) or 20 (+) µg of SecYEG complex with 0 (–), 10 (+), 30 (++) or 60 (+++) µg of YidC protein. Samples were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and silver staining.

Fig. 3. Effect of reconstituted YidC on proOmpA translocation and proOmpA-stimulated SecA ATPase activity of SecYEG proteoliposomes. Translocation of [125I]proOmpA was carried out for 10 min at 37°C. SecA ATPase activity was assayed in the presence (white bars) or absence (black bars) of proOmpA. The activity measured with SecYEG proteoliposomes in the presence of proOmpA was set to 100%.

Sequential interaction of the transmembrane segment of FtsQ with SecY and YidC during membrane insertion into proteoliposomes

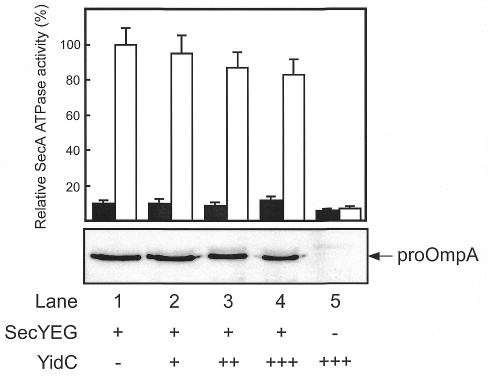

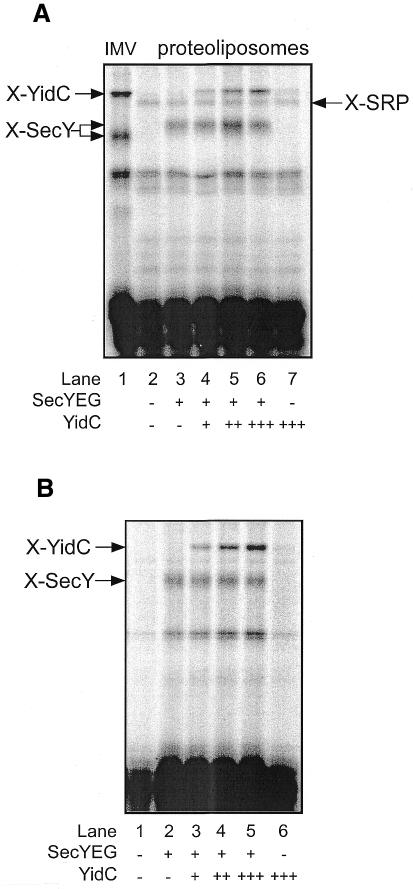

The E. coli FtsQ is a monotopic type II membrane protein that interacts with YidC in vitro (Scotti et al., 2000), and that depends on YidC for efficient membrane insertion in vivo (Urbanus et al., 2001). Site-specific crosslinking has been used to demonstrate an interaction between YidC and the TMS of a nascent FtsQ during insertion into E. coli IMVs (Scotti et al., 2000). To determine whether YidC was functionally reconstituted into the liposomes, insertion intermediates of a FtsQ 108mer (108FtsQ) were generated by in vitro translation of truncated mRNAs and SRP-/FtsY-mediated targeting of the ribosome-bound nascent chains to the proteoliposomes. In these nascent chains, the photoreactive amino acid analog 4-(3-trifluoromethyl-3-diazirinyl)phenylalanine [(Tmd)Phe] was introduced into the middle of the TMS (position 40) by suppression of a TAG codon using (Tmd)Phe-tRNAsup. As shown previously, UV irradiation leads to crosslinking of SecY and YidC in IMVs (Figure 4A, lane 1) (Scotti et al., 2000; Urbanus et al., 2001). With SecYEG proteoliposomes, a crosslink to SecY was obtained (Figure 4A, lane 3). However, in SecYEG/YidC proteoliposomes, an additional crosslink to YidC was found, which increased with the amount of YidC present in the proteoliposomes (Figure 4A, lanes 4–6). Strikingly, no YidC crosslink was observed with proteoliposomes containing YidC alone (Figure 4A, lane 7). The same results were obtained with 108FtsQ containing a unique cysteine at position 40 (Figure 4B). In this case, crosslinking was induced by the homo-bifunctional reagent bis-maleimidoethane (BMOE). These data demonstrate that the purified YidC has been functionally reconstituted into proteoliposomes, and that YidC co-operates with SecY to mediate the membrane insertion of FtsQ.

Fig. 4. The TMS of membrane-inserted 108FtsQ interacts with reconstituted YidC in a SecYEG-dependent manner. (A) In vitro synthesis of a FtsQ 108mer with a UAG codon at position 40 was carried out in the presence of (Tmd)Phe-tRNAsup. After the addition of reconstituted SRP, SRP–ribosome–nascent chain complexes were purified by centrifugation through a high-salt sucrose cushion, and used in targeting reactions containing IMVs or proteoliposomes. Samples were UV irradiated, subsequently extracted with carbonate and analyzed on 13% SDS–PAGE. (B) In vitro synthesized nascent FtsQ 108mer with a unique cysteine at position 40 was incubated with IMVs or proteoliposomes, and crosslinked with 1 mM BMOE. The higher molecular mass of the crosslinking products (X-SecY and X-YidC) in the proteoliposomes as compared with IMVs is due to the presence of His tags on YidC and SecY.

The crosslinking data indicate that the TMS of inserted 108FtsQ is in the vicinity of SecY and YidC. However, since YidC can only be crosslinked to 108FtsQ in the presence of SecYEG, it appears that the TMS first interacts with SecY before gaining access to YidC. To test this hypothesis, a shorter nascent chain of FtsQ was used, i.e. a 77mer with the TAG codon at position 40. At this nascent chain length, the crosslinking probe is just exposed outside the ribosome. The 77FtsQ derivative was strongly crosslinked to SecY and barely to YidC (Figure 5). The efficiency of SecY crosslinking to 77FtsQ increased with the amount of YidC. Apparently, YidC stabilizes the interaction between the TMS of nascent FtsQ and SecY.

Fig. 5. The TMS of membrane-inserted 77FtsQ interacts with SecY and not with YidC. In vitro translation of 77FtsQTAG40, targeting and photo-crosslinking are as described in the legend to Figure 4.

Concluding remarks

In this paper we report the functional reconstitution of purified YidC into proteoliposomes. Our crosslinking data indicate that YidC cooperates with SecYEG in mediating membrane insertion of nascent FtsQ. Remarkably, crosslinking to YidC depends on the presence of SecYEG in the proteoliposomes and on a sufficient length of the nascent chain. These results support a model in which ribosome-bound nascent inner membrane proteins are first targeted by SRP to the SecYEG complex (Valent et al., 1998), a process that is likely to involve high affinity binding of the ribosome to the SecYEG complex (Prinz et al., 2000). Next, the nascent chain is transferred to SecY, and concomitantly with chain elongation, inserted TMSs move to YidC. YidC presumably mediates the lateral diffusion of TMS into the lipid phase (Samuelson et al., 2000; Scotti et al., 2000; Urbanus et al., submitted). The observation that nascent FtsQ gains access to YidC via SecYEG indicates that there is at least a transient interaction between SecYEG and YidC. However, stable complexes between SecYEG and YidC in the proteoliposomes could not be detected by immunoprecipitation (data not shown).

Our study is a first step towards the complete reconstitution of membrane protein biogenesis into proteoliposomes. Complete assembly of full-length FtsQ, as monitored in IMVs by the formation of a protease-protected fragment representing the C-terminal periplasmic domain (data not shown), was not observed in SecYEG/YidC proteoliposomes with or without SecA. Other protein components might be involved in the process of FtsQ biogenesis, such as SecDFyajC, a translocase-associated complex whose exact function is not clear yet. In contrast to IMVs, proteoliposomes are also unable to generate a proton motive force, which might be required for assembly. Future studies will focus on the role of these components and factors to realize a complete reconstitution of membrane protein biogenesis into proteoliposomes.

METHODS

Strains and plasmids. Escherichia coli strain JS7131 (Samuelson et al., 2000) was used for complementation studies, and strain SF100 (Baneyx and Georgiou, 1990) was used for overexpression of YidC. Plasmid pEH1hisYidC encodes C-terminally His-tagged YidC under control of the lac promoter. The His6 tag on yidC was introduced by PCR using the primers 5′-CAGTATTTCGCGACGGCGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGAAAGCTTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGGATTTTTTCTTCTCGCGG (reverse), and plasmid pAra14-YidC (Scotti et al., 2000) as template. The KpnI–SmaI fragment of pEH1YidC (a gift from J.-W. de Gier) was replaced by the KpnI-digested PCR product. For the preparation of truncated mRNAs, plasmids pC4Meth108FtsQTAG40 (Scotti et al., 2000), pC4Meth77FtsQTAG40 (Urbanus et al., 2001) and pC4Meth108FtsQCys40, constructed by replacing the TAG codon at position 40 of FtsQ in pC4Meth108FtsQTAG40 by a TGC codon, were used. Strain MC4100 was used to obtain translation lysate and IMVs for the targeting reactions.

Overexpression and purification of YidC. An overnight culture of E. coli SF100 carrying pEH1hisYidC was diluted 40-fold into fresh LB medium supplemented with 50 µg/ml kanamycin and grown to mid-logarithmic phase (OD660 = 0.6). Expression of yidC was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and growth was continued for another 2 h. Cells were disrupted by passage through a French press (10 000 psi) and IMVs were isolated as described (Kaufmann et al., 1999). IMVs at 1 mg of protein/ml were solubilized in 2% (w/v) DDM, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM imidazole and 20% (v/v) glycerol. After 1 h at 4°C, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (30 min at 100 000 g), and the supernatant was mixed with Ni2+-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) equilibrated with buffer A [10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% (w/v) DDM] containing 10 mM imidazole. The suspension was gently shaken at 4°C, and after overnight incubation poured into a column. Beads were washed with 5 column volumes of buffer A containing 40 mM imidazole, and bound proteins were eluted with 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 400 mM imidazole, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% (w/v) DDM. YidC-containing fractions were pooled, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C.

Reconstitution of YidC and SecYEG into proteoliposomes. Acetone/ether-washed E. coli phospholipids (100 µl; 4 mg/ml) (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., Birmingham, AL) were solubilized with 7 mM Triton X-100, and mixed with the indicated amounts of purified SecYEG (van der Does et al., 1998) and/or YidC. After 30 min on ice, the mixture was diluted with 800 µl of buffer R (50 mM HEPES–KOH pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl) and supplemented with Bio-Beads SM-2 (20 mg wet weight) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The suspension was gently shaken at 4°C, and the Bio-Beads were replaced after 2, 4 and 6 h. After overnight incubation, the Bio-Beads were discarded and the proteoliposomes were collected by centrifugation (20 min at 200 000 g). The pellet was washed twice with 2 ml of buffer R and finally suspended in 100 µl of buffer R. Proteoliposomes were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C.

In vitro transcription, translation, targeting and crosslinking. Truncated mRNAs were prepared by linearizing the FtsQ derivative plasmids with HindIII followed by transcription using T7 polymerase according to the manufacturer’s conditions (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). For photocrosslinking, (Tmd)Phe was site-specifically incorporated into nascent FtsQ by suppression of UAG stop codons using (Tmd)Phe-tRNAsup in an in vitro translation system as described by Houben et al. (2000). After 3 min of incubation at 37°C, 1 mM aurintricarboxylic acid (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH) was added to inhibit further initiation of translation resulting in a homogeneous nascent chain length. Translation reactions were stopped after 20 min by adding 30 µM chloramphenicol. Reconstituted SRP (Valent et al., 1998) was added at 260 nM, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min at 37°C. SRP–ribosome–nascent chain complexes were purified from the translation mixture by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion (High et al., 1991). They were resuspended in 100 mM KOAc, 5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 50 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.9 and used in targeting reactions together with 0.56 µM FtsY, 50 µM GTP, 50 µM ATP and either IMVs or proteoliposomes as described (Scotti et al., 1999). Photocrosslinking was induced by UV irradiation (Scotti et al., 2000). Soluble and peripheral membrane proteins were extracted with 0.18 M Na2CO3 pH 11.3 for 10 min on ice. Membrane fractions were collected by centrifugation (10 min, 110 000 g) and analyzed by 13% SDS–PAGE and phosphoimaging. For chemical crosslinking, the same procedure was followed except that a standard in vitro translation system was used (Valent et al., 1998). Crosslinking was induced with 1 mM BMOE (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and after 10 min at 26°C reactions were quenched by the addition of 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Other methods. Purification of E. coli SecA, SecB and proOmpA was carried out as described previously (van der Does et al., 1998). Blue Native PAGE was performed on 6–16% gradient gels as described (Schägger and von Jagow, 1991). ProOmpA translocation (van der Does et al., 2000) and SecA translocation ATPase activity (Lill et al., 1989) were assayed as described. Protein concentrations were determined with the DC Protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Corinne ten Hagen-Jongman for the construction of plasmid pEH1hisYidC, Jan-Willem de Gier for providing plasmid pEH1YidC, Ross Dalbey for providing strain E. coli JS7131 and Chris van der Does, Jelto Swaving and Pier Scotti for discussion. This work was supported by the Earth and Life Sciences Foundation (ALW), which is subsidized by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

REFERENCES

- Andersson H. and von Heijne, G. (1993) Sec-dependent and Sec-independent assembly of E.coli inner membrane proteins: the topological rules depend on chain length. EMBO J., 12, 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baneyx F. and Georgiou, G. (1990) In vivo degradation of secreted fusion proteins by the Escherichia coli outer membrane protease OmpT. J. Bacteriol., 172, 491–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck K., Wu, L.F., Brunner, J. and Müller, M. (2000) Discrimination between SRP- and SecA/SecB-dependent substrates involves selective recognition of nascent chains by SRP and trigger factor. EMBO J., 19, 134–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gier J.W., Valent, Q.A., von Heijne, G. and Luirink, J. (1997) The E.coli SRP: preferences of a targeting factor. FEBS Lett., 408, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman J., Mendel, D., Anthony-Cahill, S., Noren, C.J. and Schultz, P.G. (1991) Biosynthetic method for introducing unnatural amino acids site-specifically into proteins. Methods Enzymol., 202, 301–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S. and Fox, T.D. (1997) Membrane translocation of mitochondrially coded Cox2p: distinct requirements for export of N- and C-termini and dependence on the conserved protein Oxa1p. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 1449–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell K., Herrmann, J., Pratje, E., Neupert, W. and Stuart, R.A. (1997) Oxa1p mediates the export of the N- and C-termini of pCoxII from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space. FEBS Lett., 418, 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell K., Herrmann, J.M., Pratje, E., Neupert, W. and Stuart, R.A. (1998) Oxa1p, an essential component of the N-tail protein export machinery in mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 2250–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High S., Flint, N. and Dobberstein, B. (1991) Requirements for the membrane insertion of signal-anchor type proteins. J. Cell Biol., 113, 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben E.N., Scotti, P.A., Valent, Q.A., Brunner, J., de Gier, J.L., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (2000) Nascent Lep inserts into the Escherichia coli inner membrane in the vicinity of YidC, SecY and SecA. FEBS Lett., 476, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann A., Manting, E.H., Veenendaal, A.K., Driessen, A.J.M. and van der Does, C. (1999) Cysteine-directed cross-linking demonstrates that helix 3 of SecE is close to helix 2 of SecY and helix 3 of a neighboring SecE. Biochemistry, 38, 9115–9125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.I., Kuhn, A. and Dalbey, R.E. (1992) Distinct domains of an oligotopic membrane protein are Sec-dependent and Sec-independent for membrane insertion. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 938–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R., Cunningham, K., Brundage, L.A., Ito, K., Oliver, D. and Wickner, W. (1989) SecA protein hydrolyzes ATP and is an essential component of the protein translocation ATPase of Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 8, 961–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luirink J., ten Hagen-Jongman, C.M., van der Weijden, C.C., Oudega, B., High, S., Dobberstein, B. and Kusters, R. (1994) An alternative protein targeting pathway in Escherichia coli: studies on the role of FtsY. EMBO J., 13, 2289–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manting E.H. and Driessen, A.J.M. (2000) Escherichia coli translocase: the unravelling of a molecular machine. Mol. Microbiol., 37, 226–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manting E.H., van der Does, C., Remigy, H., Engel, A. and Driessen, A.J.M. (2000) SecYEG assembles into a tetramer to form the active protein translocase channel. EMBO J., 19, 852–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann-Haefelin C., Schäfer, U., Müller, M. and Koch, H. (2000) SRP-dependent co-translational targeting and SecA-dependent translocation analyzed as individual steps in the export of a bacterial protein. EMBO J., 19, 6419–6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz A., Behrends, C., Rapoport, T.A. and Kalies, K.U. (2000) Evolutionarily conserved binding of ribosomes to the translocation channel via the large ribosomal RNA. EMBO J., 19, 1900–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson J.C., Chen, M., Jiang, F., Möller, I., Wiedmann, M., Kuhn, A., Phillips, G.J. and Dalbey, R.E. (2000) YidC mediates membrane protein insertion in bacteria. Nature, 406, 637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H. and von Jagow, G. (1991) Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal. Biochem., 199, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti P.A., Valent, Q.A., Manting, E.H., Urbanus, M.L., Driessen, A.J.M., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (1999) SecA is not required for signal recognition particle-mediated targeting and initial membrane insertion of a nascent inner membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29883–29888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti P.A., Urbanus, M.L., Brunner, J., de Gier, J.W., von Heijne, G., van der Does, C., Driessen, A.J.M., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (2000) YidC, the Escherichia coli homologue of mitochondrial Oxa1p, is a component of the Sec translocase. EMBO J., 19, 542–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanus M.L., Scotti, P.A., Fröderberg, L., Sääf, A., de Gier, J.W., Brunner, J., Samuelson, J.C., Dalbey, R.E., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (2001) Sec-dependent membrane protein insertion: sequential interaction of nascent FtsQ with SecY and YidC. EMBO Rep., 2, 524–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent Q.A., Kendall, D.A., High, S., Kusters, R., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (1995) Early events in preprotein recognition in E.coli: interaction of SRP and trigger factor with nascent polypeptides. EMBO J., 14, 5494–5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent Q.A., de Gier, J.W., von Heijne, G., Kendall, D.A., ten Hagen-Jongman, C.M., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (1997) Nascent membrane and presecretory proteins synthesized in Escherichia coli associate with signal recognition particle and trigger factor. Mol. Microbiol., 25, 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent Q.A., Scotti, P.A., High, S., de Gier, J.W., von Heijne, G., Lentzen, G., Wintermeyer, W., Oudega, B. and Luirink, J. (1998) The Escherichia coli SRP and SecB targeting pathways converge at the translocon. EMBO J., 17, 2504–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Does C., Manting, E.H., Kaufmann, A., Lutz, M. and Driessen, A.J.M. (1998) Interaction between SecA and SecYEG in micellar solution and formation of the membrane-inserted state. Biochemistry, 37, 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Does C., Swaving, J., van Klompenburg, W. and Driessen, A.J.M. (2000) Non-bilayer lipids stimulate the activity of the reconstituted bacterial protein translocase. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 2472–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]