Highlights

-

•

Green synthesized MgO NPs investigated for shelf life enhancement of Vitis vinifera.

-

•

28.60 nm, 25.56 nm and 21.78 nm MgO NPs were prepared by 20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM solutions of salts.

-

•

28.6 nm crystalline particle were more effective to control bacterial and fungal growth on fruit.

-

•

MgO NPs coated fruit survived for 20 days as 4 °C.

-

•

Present research may contributed toward achievement of SDG-2.

Keywords: MgO NPs, Antimicrobial, Shelf life, Packaging, Azospirilum brasilense and Trichoderma viride

Abstract

The objective of the study was to extend shelf life of Vitis vinifera (L.) by the application of green synthesized Magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica A. juss. and various concentrations of 20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM solutions of Magnesium nitrate hexa hydrate salt, were used to synthesize nanoparticles of different size. The characterization of nanoparticles was done by SEM, XRD, and UV. The antimicrobial activity of MgO NPs was evaluated for Azospirilum brasilense and Trichoderma viride, representative of microbes responsible for V. vinifera fruits spoilage. Nanoparticles with crystal size of 28.60 nm has more pronounced effect against microbes. The Shelf life of the Vitis vinifera L. was evaluated by application of 28.60 nm MgO NPs through T1 (nanoparticles coated on packaging), T2 (nanoparticles coated directly on fruit) at 4 °C and 25 °C. T1 at 4 °C was effective to extend the shelf life of Vitis vinifera (L) for an average of 20 days.

1 Introduction

The phenomenon of food insecurity is not unique to low and middle income countries it is also prevalent in high-income countries. This highlights the challenge and difficulty in achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2, set by the United Nations to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030. Statistics showed that between 691 and 783 million people faced hunger in 2022 (Canbolat, Rutkowski, & Rutkowski, 2023). Malnutrition now affects over two billion people worldwide, resulting in poor health, low productivity, high rates of mortality, increased rates of chronic diseases, and permanent impairment of cognitive abilities of infants born to micronutrient-deficient mothers.

The basic nutrient need of every human being should be fulfilled and it is crucial challenge of the present world. Although crops like wheat and rice are major sources to overcome hunger. But the compounds that are required to get balanced diet also need fruits and vegetables. Fruits and vegetables are an important nutritive food source (Ali, Shahid, and Shahid, 2023). They are rich source of carbohydrates, vitamins, proteins, and minerals. Fresh fruits and vegetables have always been in demand. Harvested fruits and vegetables require adequate and advanced postharvest processing technologies to minimize the qualitative as well as quantitative post-harvest losses. Nearly 40 % of fruits and vegetables are wasted every year due to improper handling, storage, packaging, and transportation. Wastage of fruits and vegetables in huge amounts also reduces the per capita availability of fruits and vegetables (Singh et al., 2014). Raw fruits are good source of energy for every age group of the population. Grapes possess cardio protective, hepato protective and neuro protective effects due to protein, carbohydrates, lipids and polyphenols.

Grapes are non-Climatic type of fruit. The cultivation of the domesticated grape began 6,000–8,000 years ago in East. It is very important fruit and gives more income to farmers than the other crops. China, France, United America, South Africa, Italy, Chile, Iran, Turkey, Spain, and Argentina are the top ten countries for grapes production in the world. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 75,866 square kilometers of the world are dedicated to grapes (Khan et al., 2020). Like many other fruits, grapes undergo numerous physicochemical, biochemical, and microbiological changes during storage, accelerating the ripening process and reducing their shelf life. Many microorganisms are responsible for the decomposition of grapes as E. coli, Aspergillus, listeria, yeast, and moulds. These changes are accompanied by economic postharvest aftermaths due to weight losses and the occurrence of decay. Therefore, it is very important to find low-cost and efficient nontoxic preservation method to improve the internal quality and commercial value of grapes.

Several studies have documented for effective postharvest management of grapes as they are very vulnerable to easy deterioration. Food packaging biomaterials have important role in food protection from environmental factors (light, moisture, oxygen, bacteria, mechanical stress), therefore must exhibit barrier property to retard the oxygen permeability, the antimicrobial activity toward bacteria and greater mechanical strength to environmental stress to retain food quality, and prolong shelf life of food. The application of nanotechnology in food to overcome quality-keeping issues is a novel approach (Batool et al., 2022, Batool et al., 2022). Various nanoparticles (Ag, Cu, Fe, Zn, and Au) with antimicrobial activities have been synthesized. However, these nanoparticles showed unacceptable toxic effects on human health and the environment. Chronic exposure to silver causes toxic effects like liver and kidney damage, irritation of the eyes, skin, respiratory and intestinal tract, and changes to blood cells (Ahmed et al., 2010). In contrast to the above-mentioned nanoparticles, the use of Magnesium nanoparticles for the enhancement of shelf life of fruits and vegetables can be beneficial for obtaining desired results in food safety and storage (Chowdury et al., 2020). Magnesium oxide is resourceful oxide material with numerous attributes such as high chemical and photo stability, large band gap, low dielectric constant, and refractive found in many industrial applications and scientific applications in diverse fields of catalysis, antimicrobial and antibacterial materials (Kumar et al., 2021). Green synthesis of MgO is considered potential and eco-friendly way to create Inorganic metal oxide nanoparticles. Azadirachta indica A. Juss. commonly known Neem was selected to synthesize MgO NP’s. The literature study confirmed that Neem leaf extract showed excellent antimicrobial activity against fungus and foodborne pathogenic bacteria (Ahmed et al., 2023, Masnilah et al., 2023). Neem is native plant of India and China, mainly cultivated throughout Pakistan and India. Almost every part of the plant, especially the leaves, is of great medicinal importance (El-Mernissi et al., 2023). The bioactive isolates of plant includes nimbin, nimbolide, azadiracticin, meliacin, gedunin and salanin (Maji & Modak, 2021). Therefore present study was designed to synthesis magnesium nanoparticles by using aqueous extract of neem leaves and evaluate their potential to prolong shelf life of Vitis vinifera.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All the materials were purchased from Sigma Chemical Limited.

2.2. Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles

2.2.1. Collection of plant material

Leaves of Azadirachta indica (Neem) were collected from the Botanical garden of Lahore College for Women University (LCWU). The leaves were washed thoroughly with water and dried for 2–3 days at room temperature, crushed into powder and stored in airtight containers for further use.

2.2.2. Preparation of the plant extract

The aqueous plant extract was prepared by following the methodology of Aftab et al., 2020 with slight modifications. Freshly prepared aqueous Neem leaf extract was used to synthesize MgO NP’s.

2.2.3. Stock solutions preparation

Although there are different salts of magnesium like magnesium citrate, glycinate, chloride, malate and sulfate but magnesium nitrate hexahydrate salt (MgNO3)2·6H2O was used as precursor material because it was highly soluble in water (NCBI, 2023). Magnesium oxide nanoparticles were synthesized using different concentrations of magnesium nitrate salt (20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM) from 1 M stock solutions following the methodology of Sharma, Sharma, and Sahu (2017). The objective of using different concentrations was to obtain variation in nanoparticles size. The formation of MgO NP’s was confirmed by the color change of the solutions from yellow to yellowish brown (Moorthy, Ashok, Rao, & Viswanathan, 2015). The solutions was shaken for 24 h at 150 rpm on rotary shaker, then dried overnight at 100 °C in an oven to evaporate its water content. After evaporation, the residue was powdered using pestle and mortar. The powdered sample was calcinated at 500 °C for 1 h in muffle furnace to obtain MgO NP’s (Moorthy et al., 2015). These MgO NP’s were used for further analysis.

2.2.4. Characterization of magnesium oxide nanoparticles

The characterization (morphology, size and shape) of green synthesized magnesium oxide nanoparticles was done by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) (EVO-LS-10), X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) (D8-Discover) and UV–visible spectroscopy (UV-2000).

2.2.5. Antimicrobial analysis of MgO NP’s

The antimicrobial analysis of MgO NP’s was evaluated by the agar well diffusion method according to the methodology of (Erhonyota ete al., 2023). Bacterial strain Azospirilum brasilense (FCBP-SB-0025) and fungal strain Trichoderma viride (FFCB-DNA-639) were collected from the First Fungal Culture Bank of Pakistan (FCBP), Institute of Agricultural Sciences (IAGS) University of Punjab, Lahore. These strains were used as representative microorganisms for fruits spoilage.

2.3. Application of magnesium nanoparticles to enhance shelf life of grapes

2.3.1. Collection and pretreatment of grapes

Fresh green grapes of approximately similar size, shape, maturity, and color were collected from grape vines located in Lahore, Pakistan, and transferred to the laboratory. The grapes were cleaned and MgO NP’s coating treatment was performed on the same day. Experimental design was Complete Randomized split block design. It consisted of two treatments (T1 and T2), control (T0) and three different packaging materials (Cardboard, paper, and Plastic bag). All treatments were in triplicate and stored at room temperature (25 °C) and cold temperature (4 °C). T1 treatment represented nanoparticles coating inside the packaging material. Whereas, T2 indicate nanoparticles coating on fruits and T0 is control.

2.3.2. Sample preparation

Weight of each replicate sample of grapes consisted of 250 mg. The experimental samples were stored at room temperature (25 °C) and cold temperature (4 °C). Coating solution was prepared by dissolving 0.5 mg of MgO-NP’s/ mL of distilled water. Then the solution was coated directly on the fruits and inside packaging materials. Effect of MgO NP’s on shelf life of grapes was checked at 4 days intervals by observing the physiological weight loss, moisture content, Decay loss, peroxidase activity, total phenolic content, total antioxidant activity and DPPH radical scavenging assay (Batool et al., 2022, Batool et al., 2022).

2.3.4. Physiological weight loss (PWL)

The % physiological weight loss was calculated by using the formula (Hayat et al., 2017).

Where,

A = weight of the fruit at the time of harvest and B = weight of fruit at a specific interval.

2.3.5. Decay loss

During Storage samples of each treatment were visually evaluated for decay loss by 4 days intervals. The decayed fruits were removed by detecting the extent of gray and brown spots on surface in daylight. (Kadi, 2023). The % decay loss was calculated by using the formula as,

Where;

nr = the number of decayed grapes, n0 = the number of total Grapes.

2.3.6. Moisture content

For moisture content determination 1 g of grapes from each replicate of both treatments and control were taken and placed in weighed petri dish.. The samples were placed in an electric oven at 120 °C for 4hrs until the constant weight was attain. Then cooled and weighed again. Moisture content was calculated by using the formula (Sinha et al., 2019):

Where,

IW = initial weight and FW = final weight (g).

2.3.7. Total phenolic content (TPC) assay

Total phenolic contents were determined using the procedure described by Dewanto, Wu, and Liu (2002). The extract of grapes (0.1 mL) was added to 2.8 mL of 10 % Na2CO3 and 0.1 mL of 2 N Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 725 nm in UV–visible spectrophotometer. TPC were calculated as ug/g of dry weight by using the following standard equation. Gallic acid equivalent standard calibration curve prepared by variable Gallic acid concentrations using

Y = 0.005x + 0.047, where (R2 = 0.998).

2.3.8. Total antioxidants assay (TAA)

The total antioxidant potential of the fruits was determined according to the method of Aftab et al. (2020). The extract of each sample (2 mL) was mixed with 2 mL of reagent solutions (0.6 M sulphuric acid, 4 mM ammonium molybdate, and 28 mM sodium phosphate). The reaction mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 60 min and cooled to room temperature. The antioxidant activity was expressed in terms of absorption at wavelength of 695 nm. Alpha-tocopherol was used as standard at variable concentrations ranging from 200 − 1.562 mg/ml.

2.3.9. Diphenyl picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) radical assay

The DPPH radical scavenging activity assay was carried out according to the method of Aftab et al., 2020. The reaction mixture was prepared by dissolving 0.0008 g of DPPH in 28 mL of DMSO. Then 2 mL of above solutions was mixed with 2 mL of the test sample and kept in dark for half an hour. The scavenging activity was measured in terms of absorption at 517 nm in triplicate. The antioxidant activity was expressed as % scavenging activity (SC%) of DPPH radical. Alpha-tocopherol was used as standard at variable concentrations ranging from 200 to 1.562 mg/ml. The formula used to compute DPPH inhibition was:

% inhibition of DPPH = (1-abs of sample/abs of control) × 100.

2.3.10. Determination of peroxidase activity (POD)

The peroxidase activity was estimated by the methodology of Kamińska et al. (2022). Sample of 0.2 g of grapes was taken from each replicate and ground in liquid nitrogen, then added 0.5 mL of 1 mM phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.0); 1 mL of 1 mM EDTA, 1 mL of 1 mM ascorbic acid, 1 mL riboflavin, 1 mL of 0.1 % PVP. The samples were centrifuged at 0.0118 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and used for the determination of peroxidase by taking 1 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.0), 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide, 1 mL guaiacol, and 0.5 mL enzyme extract to make the final reaction mixture, and absorbance was checked with UV–vis spectrophotometer at 420 nm.

2.3.11. Anti-microbial analysis

The antimicrobial analysis of fruit samples from both treatments was determined by agar well diffusion method Daoud, Douadi, Hamani, Chafaa, and Al-Noaimi (2015). Analysis was performed for bacterial strain Azospirilum brasilense (FCBP SB 0025) and fungal strain Trichoderma viride (FFCB DNA 639). Fluconazole drug was used as standard against fungal strains and amoxicillin drug was used as standard against bacterial strains to compare the results. The experiment was performed in replicates.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data collected to determine effects of different treatments, storage condition: temperature (4 °C and 25 °C) and packaging materials on grapes shelf life was subjected to two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using IBM SPSS statistics 20 software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of green synthesized of magnesium oxide nanoparticles

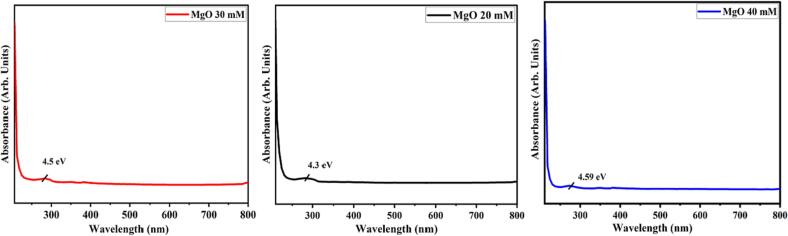

3.1.1. Uv–vis spectrophotometry

The optical characteristics of MgO NP’s synthesized from 20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM concentrations were examined using electronic spectra over the 210 to 800 nm wavelength range (Fig. 1). An absorption peak can be seen at wavelength of 288 nm in MgO NP’s from 20 mM of salt. As the concentration of the precursor salt increased, a blue shift, known as a hypochromic shift, was observed in the absorption spectra. The blue shift that coincides with the absorption of synthesized nanoparticles is suggestive of either morphological processes involving a large number of active sites or quantum confinement effect. The photo energy equation, E = hc/λ, was used to compute the Eg value as 4.3, 4.5, and 4.59 eV for MgO NP’s from 20, 30, and 40 mM concentrations of salt (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Absorption spectrum of 20 mM, 30 mM and 40 mM MgO NPs.

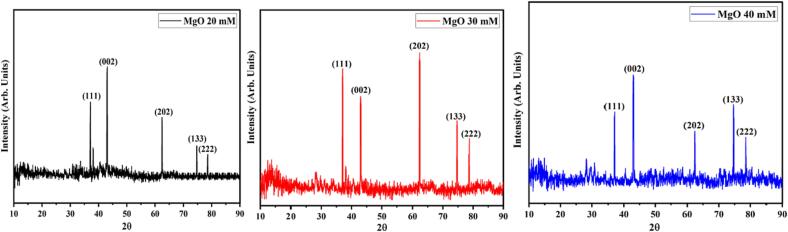

3.1.2. XRD pattern

The crystal structure and phase identification of MgO NP’s synthesized from different concentrations of salt (20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM) were investigated through XRD in the 2θ range from 10 to 90° (Fig. 2). Diffraction peaks at 36.98° (1 1 1), 42.76° (0 0 2), 62.56° (2 0 2), 74.71° (1 1 3) and 78.67° (2 2 2) revealed cubic configuration (a = 4.2 Å) of MgO NPs with space group Fm-3 m confirmed by (JCPDS card no. 01-087-0653). The XRD analysis reveals no additional impurity phases were observed upon increasing the salt concentration from 20 mM to 40 mM. The XRD pattern showed a highly intense (0 0 2) orientation plane, indicating that the synthesized material is highly crystalline. The Debye Scherrer formula (D = 0.89 /βcosθ) was used to calculate the average crystalline size of MgO NP’s synthesized from 20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM concentrations of salt. The sizes were as 28.60 nm, 25.46 nm, and 21.78 nm respectively.

Fig. 2.

XRD pattern of 20 mM, 30 mM and 40 mM MgO NPs.

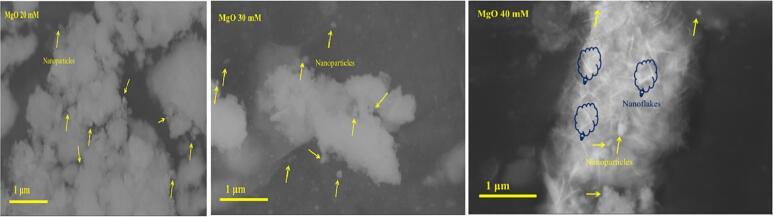

3.1.3. Scanning electron microscopy

The morphology and structural analysis of MgO NP’s from 20 mM, 30 mM, and 40 mM of salts were investigated using scanning electron micrographs (SEM) (Fig. 3). The resulted images indicated that the nanoparticles with smooth surfaces were virtually spherical. Some of the particles were found to be well dispersed, whereas the majority of them were aggregated (Fig. 3). SEM micrograph studies ensure the attachment of MgO NP’s onto the surface of MgO Nano flakes in sample 40 mM concentrations.

Fig. 3.

SEM micrograph of 20 mM 30 mM and 40 mM MgO NPs.

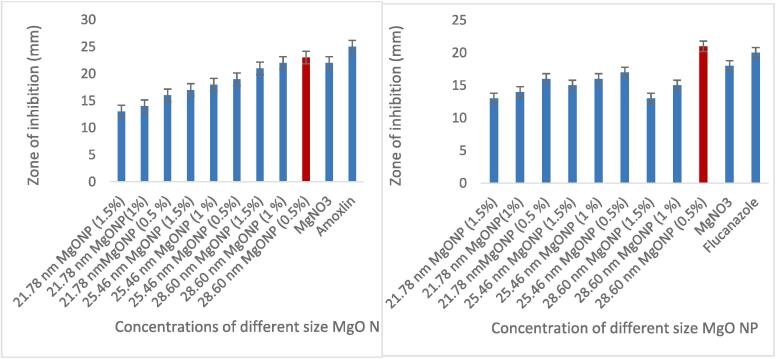

3.1.4. Antimicrobial activity of magnesium oxide nanoparticles

Antimicrobial potential of MgO NP’s were examined for selection of efficient sized nanoparticles in further application on shelf life. As fruits and juices are vulnerable to deterioration easily due to the microbes. The antimicrobial potential of different size MgO NPs in three different concentrations (0.5, 1 and 1.5 mg/mL) were evaluated by agar well diffusion method against bacterial strain (Azospirilum brasilense) and fungal strain (Trichoderma viride). The results showed that maximum zones of inhibition produced by different sized 28.60 nm, 25.46 nm, and 21.78 nm MgO NP’s against bacteria were as 18 ± 0.4, 19 ± 0.2 mm and 23 ± 0.4 mm respectively. The maximum zone of inhibition against bacterial and fungal strains was resulted by 28.60 nm (0.5 %) as presented in Fig. 4. Therefor, 0.5 % of 28.60 nm MgO NP’s were selected for application in further experiment specified for the shelf life extension of grapes.

Fig. 4.

Zone of inhibition (mm) for antibacterial activity of MgO NPs (R) Zone of inhibition (mm) for antifungal activity of MgO NPs (L).

3.2. Effect of magnesium nanoparticles on shelf life of grapes

3.2.1. Physiological parameter analysis

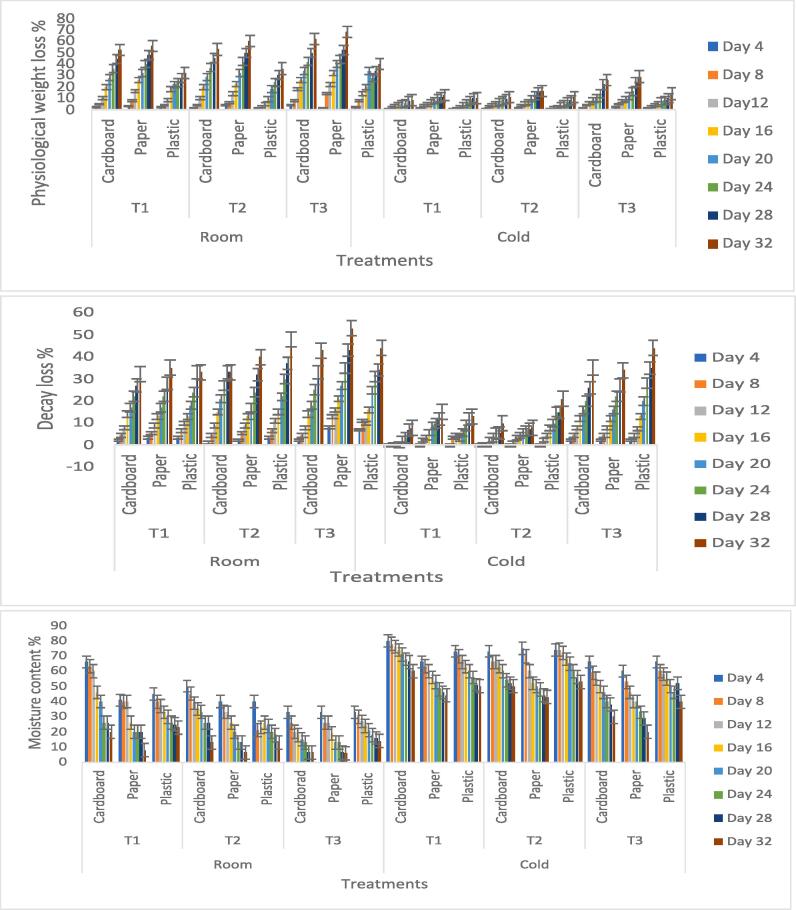

3.2.1.1. Physiological weight loss

Physiological weight loss is an important parameter for the estimation of the shelf life of fruits. The weight of fresh fruits and vegetables declines substantially with time. Normally, the maximum 5 % weight loss is acceptable and the fruits with higher weight loss reduce their market value (Batool et al., 2022, Batool et al., 2022). The physiological weight loss of grapes was analyzed during storage period at room and cold temperature. It was estimated that weight loss at cold temperature in T1 (cardboard) is 4.8 % at 20th day which is significantly lower than control (cardboard) 10 % at same day and temperature (Fig. 5a). The weight loss at room temperature is comparatively higher than cold temperature. The temperature, packaging and application of nanoparticles are collectively effective for the specific parameter of physiological weight loss in fruits. The basic mechanism behind weight loss is desiccation, which normally depends upon the gradient of water pressure between the produce (fruits or vegetables) tissues as well as storage temperature and surrounding atmosphere. The loss in weight generally leads to visible symptoms of wrinkling or wilting of fruit surface, eventually resulting in significant economic loss. The weight loss of nanoparticles treated stored grapes (T1 cardboard) was probably reduced, owing the barrier between the storage environment and fruits. Nanoparticles restricted the water loss by providing an additional hydrophobic layer on the fruit.

Fig. 5.

(a-c) Effect of treatments on Physiological weight loss%, treatments Dcay loss % and moisture content % of grapes at room and cold temperature.

3.2.1.2. Decay loss % of stored grapes

Decay in grapes is caused by microbial activity responsible for qualitative and quantitative deterioration. Decay loss can be visualized by browning, firmness loss, and temperature injuries. There was an increase in the decay loss of the grapes during the storage. At room temperature, the % decay of berries increased rapidly and maximum decay loss occurred in paper packaging, it was 53 % in control on the 32nd day. Whereas, the minimum decay of fruit was observed at cold temperature in T1 cardboard 7.7 % with the same interval. The % decay loss was significantly lower at at cold temperature in comparison to the room temperature. The maximum decay was observed in non-treated grapes but it was also high in T1 and T2 of plastic packaging at both room and cold temperature ((Fig. 5b). At room temperature, it was the microbes, and at cold temperature chilling injuries were also observed in the plastic. Khalil (2014) studied the decay loss of grapes in post-harvest treatment of salicylic acid and recorded the effect of temperature on decay loss as the cold temperature slowed down the ripening of fruits and kept them fresh for longer period. As it was evident that the applied MgO NP’s have the antimicrobial properties therefore, the treated grapes were less vulnerable to decay loss by the microbial spoilage. The other factor for the reduced decay loss of treated grapes was the packaging which is effective to reduce the decaying process. The low temperature could be of benefit to the above mentioned elements for the delay in grapes deterioration.

3.2.1.3. Moisture content

The moisture content in treated and non-treated grapes at two temperatures indicated different patterns of decline with kept time of storage. Moisture content is an important parameter for shelf life determination. In the present study, the T1 cardboard exhibited maximum moisture till the end of the trial at cold temperature. T1 cardboard showed 60 % moisture on the 32nd day. Retention of moisture at cold temperatures is due to the reduced rate of evaporation to the environment (Fig. 5c). The research study of EL-Mesery, Sarpong, and Atress (2022) in which the moisture content of tomatoes was estimated in modified packaging and that was effective in preventing moisture loss from tomato. It showed that the modified atmosphere around the fruit helps to retain the moisture. That phenomenon was very prominent in lower temperature. Thus it can be appraised that the packaging and the nanoparticles gave combined effect on the moisture maintenance in stored grapes at low temperature.

3.2.2. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities

3.2.2.1. Total Phenolic content

The total phenolic content of the grapes at room temperature was observed lower than the cold temperature. The minimum absorbance value of total phenolic content was recorded in T0 (plastic) 17 ± 0.3 at room temperature. The total phenolic content of fruits initially increased at cold temperature in nanoparticles treated samples of T1 and T2. Overall in T1 (cardboard) the maximum value of phenolic content was observed (Table 1). The total phenolic content is a determining factor for the shelf life expansion of grapes. The increase in the total phenolic during the storage period at the initial stage is due to the ripening of fruits. A higher amount of phenolic was observed in cold storage grapes than at room temperature. It was observed that the weight loss of fruit started after the higher amount of the phenolics accumulation. Amini et al. (2016) evaluated the Phenolic content and the shelf life span of Juglans regia L. to predict the patterns of phenolic content with time. An increase in the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity during timeline of storage (4 C) was observed in the control and treated samples. It has been reported that phenolic content generally increases with the ripening of fruits. The increased phenolic in the nanoparticles treated fruits may be acclaimed to continuous biosynthesis and reduced oxidation because phenolic are prone to oxidative reduction during storage. Increased phenolic have also been reported in basil seed mucilage coated fresh cut apricots (Lima et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Total phenolic content of stored grapes at 4 °C and 25 °C.

|

ROOM TEMPERTURE 4 °C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days |

T1 |

T2 |

T0 |

||||||

| CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | |

| 4 | 140 ± 0.3 | 140 ± 0.6 | 129 ± 0.4 | 120 ± 0.4 | 110 ± 0.4 | 130 ± 0.4 | 88 ± 0.4 | 84 ± 0.45 | 69 ± 0.5 |

| 8 | 141 ± 0.2 | 141 ± 0.5 | 132 ± 0.4 | 121 ± 0.5 | 109 ± 0.4 | 120 ± 0.4 | 75 ± 0.4 | 80 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.4 |

| 12 | 148 ± 0.3 | 125 ± 0.3 | 138 ± 0.4 | 114 ± 0.4 | 107 ± 0.3 | 109 ± 0.3 | 80 ± 0.4 | 74 ± 0.4 | 55 ± 0.4 |

| 16 | 126 ± 0.3 | 118 ± 0.5 | 129 ± 0.4 | 110 ± 0.3 | 100 ± 0.4 | 86 ± 0.3 | 60 ± 0.3 | 64 ± 0.4 | 49 ± 0.3 |

| 20 | 114 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 0.26 | 115 ± 0.4 | 80 ± 0.4 | 86 ± 0.4 | 64 ± 0.2 | 50 ± 0.3 | 55 ± 0.3 | 40 ± 0.3 |

| 24 | 84 ± 0.4 | 71 ± 0.25 | 88 ± 0.3 | 65 ± 0.3 | 49 ± 0.3 | 54 ± 0.2 | 35 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.3 | 42 ± 0.4 |

| 28 | 70 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.25 | 60 ± 0.3 | 50 ± 0.4 | 41 ± 0.2 | 52 ± 0.2 | 25 ± 0.3 | 33 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 0.4 |

| 32 | 64 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.30 | 44 ± 0.3 | 42 ± 0.2 | 37 ± 0.2 | 40 ± 0.1 | 20 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 0.3 |

| COLD TEMPERATURE 25 °C | |||||||||

| 4 | 186 ± 0.4 | 161 ± 0.2 | 156 ± 0.4 | 170 ± 0.4 | 150 ± 0.4 | 160 ± 0.4 | 120 ± 0.4 | 100 ± 0.3 | 100 ± 0.4 |

| 8 | 196 ± 0.4 | 164 ± 0.4 | 147 ± 0.6 | 160 ± 0.4 | 141 ± 0.4 | 156 ± 0.4 | 110 ± 0.4 | 105 ± 0.3 | 116 ± 0.4 |

| 12 | 190 ± 0.4 | 162 ± 0.4 | 141 ± 0.4 | 152 ± 0.7 | 138 ± 0.5 | 152 ± 0.3 | 100 ± 0.6 | 95 ± 0.3 | 80 ± 0.3 |

| 16 | 178 ± 0.3 | 144 ± 0.4 | 140 ± 0.4 | 140 ± 0.5 | 141 ± 0.4 | 141 ± 0.5 | 98 ± 0.7 | 85 ± 0.3 | 64 ± 0.5 |

| 20 | 161 ± 0.26 | 125 ± 0.3 | 130 ± 0.4 | 134 ± 0.4 | 136 ± 0.3 | 136 ± 0.6 | 81 ± 0.4 | 64 ± 0.4 | 58 ± 0.4 |

| 24 | 148 ± 0.2 | 100 ± 0.4 | 106 ± 0.3 | 119 ± 0.3 | 120 ± 0.3 | 120 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.4 | 40 ± 0.3 |

| 28 | 124 ± 0.1 | 88 ± 0.4 | 86 ± 0.3 | 100 ± 0.3 | 113 ± 0.3 | 109 ± 0.4 | 64 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.4 | 39 ± 0.4 |

| 32 | 20 ± 0.1 | 66 ± 0.45 | 77 ± 0.4 | 84 ± 0.3 | 70 ± 0.4 | 84 ± 0.4 | 40 ± 0.3 | 39 ± 0.4 | 32 ± 0.4 |

3.2.2.2. Total antioxidant activity and DPPH radical scavenging activity

The antioxidant activity has major role in the shelf life of fruits. The antioxidant potential of fruits prevents them from oxidative deterioration thus extending the shelf life. The antioxidant potential of stored grapes at specific intervals during the storage period included total antioxidant and DPPH scavenging activity was observed. Antioxidants are compounds that can delay or inhibit the oxidation of lipids or other molecules by inhibiting the initiation or propagation of oxidative chain reactions. The ant oxidative effect is mainly due to phenolic components, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, and phenolic diterpenes (Javanmardi, Stushnoff, Locke, & Vivanco, 2003). Overall the antioxidant components extend the shelf life of fruit by delaying oxidation, maintaining color and appearance, preserving flavor and aroma and maintain nutritional value.

The antioxidant of all treated samples of T1 and T2 exhibited higher antioxidant activity, The maximum antioxidant activity was observed was observed in T1 cardboard packaging at cold temperature i.e 0.98 ± 0.0. Minimum antioxidant activity was observed in T0 paper packaging 0.002 ± 0.0. The antioxidant activity of grapes increased till day 20th of storage and then declined. The results indicated that in the treated grapes, decreasing the rates of oxidation reactions could reduce the damage of reactive oxygen species (Table 2). DPPH scavenging activity was higher in the T1 cardboard 80 % at day 4 in cold temperature. The minimum scavenging activity of the grapes was observed in the control group (Table 3). A higher percentage of DPPH is effective against the reactive oxygen species, which are the reason for damage and spoilage of fruits. The higher value of DPPH and antioxidant activity also have a positive relation with the phenolic.

Table 2.

Antioxidant activity of stored grapes at 4 °C and 25 °C.

|

ROOM TEMPERATURE 25 °C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days |

T1 |

T2 |

T0 |

||||||

| CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | |

| 4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.36 ± 0.0 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.79 ± 0.1 | 0.35 ± 0.0 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.31 ± 0.0 |

| 12 | 0.86 ± 0.0 | 0.37 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.0 | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.08 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.0 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.53 ± 0.0 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 24 | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.43 ± 0.0 | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| 28 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.22 ± 0.0 | 0.02 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 32 | 0.21 ± 0.0 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| COLD TEMPERATURE 4 °C | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.92 ± 0.0 | 0.81 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.52 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.94 ± 0.0 | 0.85 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.61 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| 12 | 0.97 ± 0.0 | 0.81 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.54 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.92 ± 0.0 | 0.70 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.56 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.81 ± 0.0 | 0.65 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 24 | 0.72 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.02 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 28 | 0.62 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 32 | 0.53 ± 0.0 | 0.31 ± 0.0 | 0.14 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

Table 3.

DPPH activity of stored grapes at 4 °C and 25 °C.

|

ROOM TEMPERATURE 25 °C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days |

T1 |

T2 |

T0 |

||||||

| CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | |

| 4 | 62 ± 0.2 | 52 ± 0.3 | 59.4 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 0.3 | 55 ± 0.4 | 57 ± 0.4 | 49 ± 0.3 | 46 ± 0.4 | 49 ± 0.4 |

| 8 | 53 ± 0.3 | 51 ± 0.4 | 60.4 ± 0.4 | 55 ± 0.4 | 59 ± 0.3 | 55 ± 0.3 | 52 ± 0.4 | 38 ± 0.3 | 43 ± 0.4 |

| 12 | 52 ± 0.4 | 50 ± 0.4 | 57.4 ± 0.4 | 54 ± 0.2 | 60 ± 0.4 | 54 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 0.4 | 41 ± 0.2 | 55 ± 0.4 |

| 16 | 50 ± 0.4 | 48 ± 0.3 | 52.4 ± 0.4 | 52 ± 0.4 | 53 ± 0.4 | 49 ± 0.4 | 45 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.4 | 50 ± 0.4 |

| 20 | 48 ± 0.4 | 43 ± 0.3 | 49.5 ± 0.4 | 50 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.4 | 40 ± 0.4 | 34 ± 0.7 | 42 ± 0.25 |

| 24 | 46 ± 0.3 | 35 ± 0.3 | 42.5 ± 0.4 | 39 ± 0.2 | 35 ± 0.2 | 34 ± 0.3 | 32 ± 0.3 | 28 ± 0.4 | 35 ± 0.4 |

| 28 | 42 ± 0.3 | 34 ± 0.3 | 37.33 ± 0.3 | 38 ± 0.1 | 32 ± 0.4 | 34 ± 0.4 | 27 ± 0.4 | 21 ± 0.4 | 33 ± 0.4 |

| 32 | 37 ± 0.4 | 33 ± 0.4 | 31.1 ± 0.1 | 34 ± 0.1 | 29 ± 0.4 | 27 ± 0.2 | 20 ± 0.4 | 18 ± 0.3 | 27 ± 0.4 |

| COLD TEMPERATURE 4 °C | |||||||||

| 4 | 80 ± 0.4 | 72 ± 0.4 | 74 ± 0.4 | 76 ± 0.4 | 69 ± 0.4 | 70 ± 0.4 | 54 ± 0.35 | 53 ± 0.3 | 55 ± 0.4 |

| 8 | 84 ± 0.4 | 74 ± 0.4 | 75 ± 0.3 | 74 ± 0.3 | 71 ± 0.3 | 68 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 0.3 | 54 ± 0.3 | 57 ± 0.4 |

| 12 | 85 ± 0.4 | 76 ± 0.4 | 77 ± 0.4 | 75 ± 0.4 | 70 ± 0.4 | 69 ± 0.3 | 49 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 0.4 | 54 ± 0.4 |

| 16 | 76 ± 0.17 | 69 ± 0.3 | 72 ± 0.3 | 70 ± 0.3 | 67 ± 0.2 | 65 ± 0.4 | 46 ± 0.4 | 45 ± 0.4 | 52 ± 0.4 |

| 20 | 73 ± 0.4 | 67 ± 0.4 | 70 ± 0.2 | 69 ± 0.3 | 64 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.4 | 45 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 0.2 |

| 24 | 68 ± 0.3 | 65 ± 0.4 | 69 ± 0.3 | 67 ± 0.3 | 59 ± 0.3 | 57 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.3 | 38 ± 0.2 | 46 ± 0.3 |

| 28 | 64 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 0.4 | 59 ± 0.4 | 52 ± 0.3 | 54 ± 0.4 | 40 ± 0.3 | 37 ± 0.4 | 42 ± 0.4 |

| 32 | 54 ± 0.4 | 50 ± 0.3 | 53 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 0.4 | 43 ± 0.3 | 45 ± 0.25 | 38 ± 0.4 | 35 ± 0.4 | 37 ± 0.2 |

3.2.2.3. Peroxidase activity

The enzymatic activity of the grapes was evaluated by the peroxidase activity. POD value increases with the increase in storage interval of samples at both temperatures. In T1 cardboard samples, the POD values were lower but increased over the time. In control the fruit sample at room temperature has higher POD because of higher temperature (Table 4). The relation between peroxidase and shelf life is that the enzyme can impact the quality and shelf life of certain food products. Specifically, peroxidase can accelerate the degradation of certain compounds, such as vitamins and pigments, through oxidative reaction. This can lead to decrease in the nutritional value and color of foods, ultimately affecting their shelf life. Peroxidase enzyme plays significant role in browning of fruits and vegetables when they are cut. The enzyme catalyzed the oxidation of phenolic compounds in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, leading to formation of brown pigments and the deterioration of fruits quality. Rabiei, Shirzadeh, Sharafi, and Mortazavi (2011) examined that POD activity was lower in Calcium treated “Jonagold” fruits in comparison with control fruits in cold temperature. The increased POD activity in control and treated fruits was increased with storage period.

Table 4.

Peroxidase activity of the stored grapes at 4 °C and 25 °C.

|

ROOM TEMPERATURE 25 °C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 |

T2 |

T0 |

|||||||

| Days | CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL | CB | PP | PL |

| 4 | 0.29 ± 0.0 | 0.43 ± 0.0 | 0.48 ± 0.0 | 0.48 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.46 ± 0.0 | 0.61 ± 0.0 | 0.71 ± 0.0 | 0.76 ± 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.36 ± 0.0 | 0.48 ± 0.0 | 0.48 ± 0.0 | 0.52 ± 0.0 | 0.56 ± 0.0 | 0.47 ± 0.0 | 0.63 ± 0.0 | 0.73 ± 0.0 | 0.76 ± 0.0 |

| 12 | 0.43 ± 0.0 | 0.55 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.57 ± 0.0 | 0.57 ± 0.0 | 0.52 ± 0.0 | 0.70 ± 0.0 | 0.75 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.49 ± 0.0 | 0.61 ± 0.0 | 0.55 ± 0.0 | 0.66 ± 0.0 | 0.61 ± 0.0 | 0.54 ± 0.0 | 0.73 ± 0.0 | 0.78 ± 0.0 | 0.84 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.56 ± 0.0 | 0.65 ± 0.0 | 0.62 ± 0.0 | 0.68 ± 0.0 | 0.66 ± 0.0 | 0.57 ± 0.0 | 0.77 ± 0.0 | 0.82 ± 0.0 | 0.85 ± 0.0 |

| 24 | 0.64 ± 0.0 | 0.71 ± 0.0 | 0.76 ± 0.0 | 0.73 ± 0.0 | 0.71 ± 0.0 | 0.65 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.84 ± 0.0 | 0.88 ± 0.0 |

| 28 | 0.64 ± 0.0 | 0.74 ± 0.0 | 0.77 ± 0.0 | 0.77 ± 0.0 | 0.78 ± 0.0 | 0.69 ± 0.0 | 0.82 ± 0.0 | 0.87 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 |

| 32 | 0.68 ± 0.0 | 0.78 ± 0.0 | 0.78 ± 0.0 | 0.81 ± 0.0 | 0.84 ± 0.0 | 0.75 ± 0.0 | 0.84 ± 0.0 | 0.88 ± 0.0 | 0.93 ± 0.0 |

| COLD TEMPERATURE 4 °C | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.21 ± 0.0 | 0.25 ± 0.0 | 0.22 ± 0.0 | 0.33 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.35 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.44 ± 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.23 ± 0.0 | 0.27 ± 0.0 | 0.25 ± 0.0 | 0.37 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.43 ± 0.0 | 0.38 ± 0.0 | 0.53 ± 0.0 | 0.49 ± 0.0 |

| 12 | 0.25 ± 0.0 | 0.28 ± 0.0 | 0.31 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.44 ± 0.0 | 0.47 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.60 ± 0.0 | 0.54 ± 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.31 ± 0.0 | 0.31 ± 0.0 | 0.33 ± 0.0 | 0.43 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.53 ± 0.0 | 0.44 ± 0.0 | 0.63 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.33 ± 0.0 | 0.37 ± 0.0 | 0.37 ± 0.0 | 0.46 ± 0.0 | 0.53 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.69 ± 0.0 | 0.63 ± 0.0 |

| 24 | 0.36 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.44 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.63 ± 0.0 | 0.61 ± 0.0 | 0.57 ± 0.0 | 0.72 ± 0.0 | 0.79 ± 0.0 |

| 28 | 0.37 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.47 ± 0.0 | 0.54 ± 0.0 | 0.69 ± 0.0 | 0.64 ± 0.0 | 0.66 ± 0.0 | 0.73 ± 0.0 | 0.81 ± 0.0 |

| 32 | 0.41 ± 0.0 | 0.44 ± 0.0 | 0.51 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.72 ± 0.0 | 0.69 ± 0.0 | 0.76 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.82 ± 0.0 |

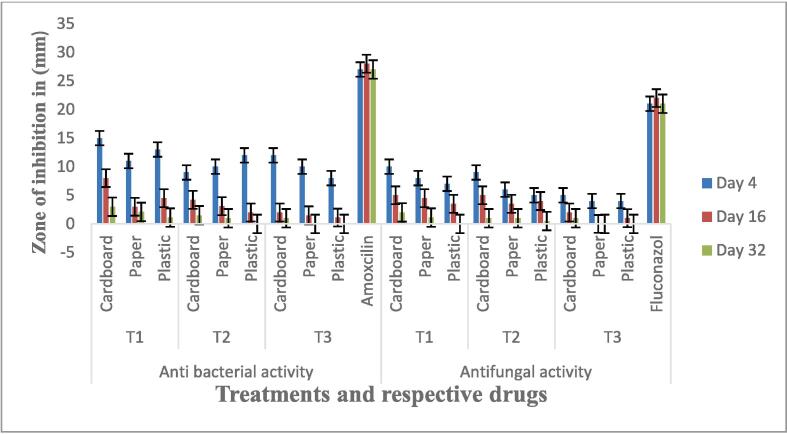

3.2.2.4. Microbial susceptibility analysis

Microbial susceptibility analysis was carried out to check the MgO NP effect on microbes present in stored fruits at different storage periods and packaging. Fruit samples were evaluated against the respective bacterial strain (Azospirilum brasilense) and fungal strain (Trichoderma viride). The microbial susceptibility is an important phenomenon for shelf life analysis. It provides the evidence for the stage of shelf life of fruits either its marketable or not and it also provide reasoning for the effectiveness of treatments applied on fruits.

The antimicrobial analysis of treated barriers of grapes was evaluated at room (25 °C) and cold temperature (4 °C). The T1 (cardboard) at room temperature showed maximum zone of inhibition against bacterial strains 15 ± 0.4 mm and antifungal potential 10 ± 0.4 mm at the end of keeping storage which is significantly higher than the T2 and T0 in all packaging (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Zone of Inhibition (mm) shown by bacteria against various treatments and Zone of Inhibition (mm) shown by fungi against various treatment.

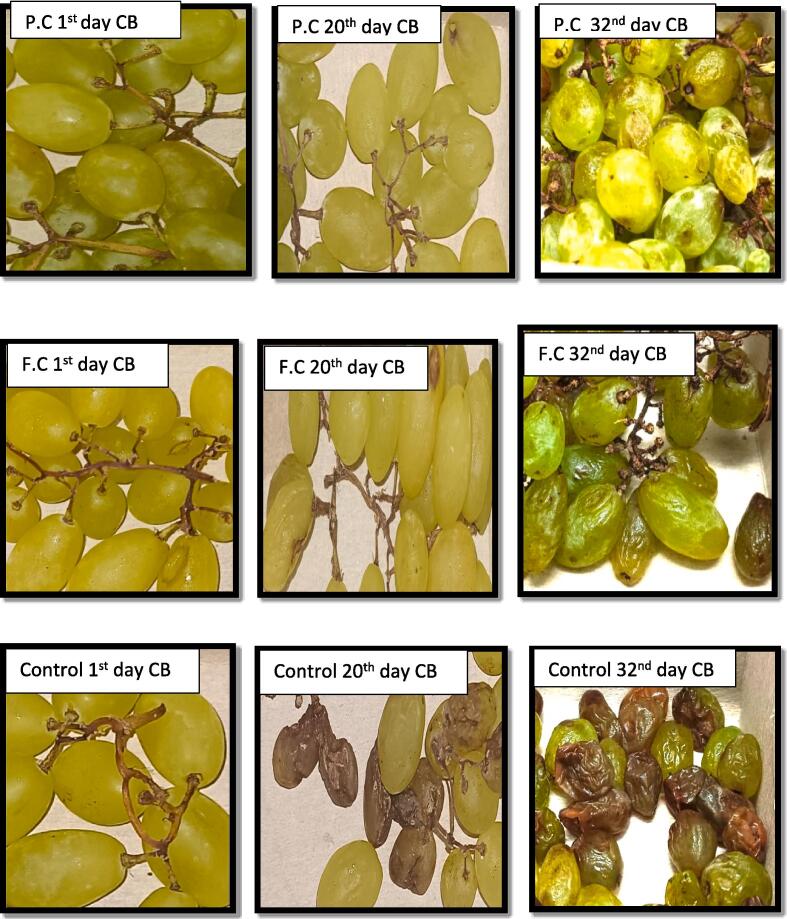

3.3. Increase in shelf life

The effect of different parameter on the shelf life of grapes was observed. The length of the shelf life was calculated by observing the grapes after an interval of 4 days and then the treatments with no decay signs were allowed to proceed further, whereas the decay was documented. In non-treated stored grapes T0 of all packaging and temperatures, a very short life span was observed that was up to 4 days approximately. Significant increase in the shelf life of grapes was observed at 4 °C. T1 treated grapes were marketable up to 16 days. However, decline in the moisture content was detected on day 20 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Changes in visual appearance of treated and non-treated grapes during storage time. KEY: P.C (Package coating T1) F.C (Fruit coating T2) CB: Cardboard.

4. Conclusion

The use of green synthesized MgO NPs for the extension of the shelf life of grapes at 4 °C is eco-friendly, cost-effective, and non-toxic. The physiological parameters such as Physiological weight loss, decay loss, moisture content and enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities of treated grapes stored at two temperatures 4 °C and 25 °C showed good results. Grapes treated with MgO NPs in cardboard packaging T1 (CB) at cold temperatures showed minimum weight loss during storage period of 32 days. Decay loss and moisture content were also maintained in the T1 (CB) packaging. Antioxidant activity and enzymatic activity along with other physiological parameters indicate that grapes stored at cold temperature in cardboard with nanoparticles treatment T1 showed considerable results for marketable shelf life of 20 days during the 32-day trial of storage. At room temperature, the T0 (control) stored grapes showed prominent decline in weight, moisture content, and antioxidant activities on day 4. Therefore, it can be concluded that the results of this experiment will be useful with particular reference to medium-term storage, quality control, transportation and marketing, and consumers. Moreover, further studies are suggested to examine the effects of other post-harvest treatments on the shelf life, quality, and safety of Grapes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shahneela Mushtaq: Investigation. Zubaida Yousaf: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision. Irfan Anjum: Formal analysis, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Shahzeena Arshad: Investigation. Arusa Aftab: Formal analysis, Software. Zainab Maqbool: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Zainab Shahzadi: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Riaz Ullah: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Essam A. Ali: Funding acquisition, Validation, Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Research Supporting Project Number RSP2024R110 at King Saud University Riyadh Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aftab A., Yousaf Z., Aftab Z.E.H., Younas A., Riaz N., Rashid M., Javaid A. Pharmacological screening and GC-MS analysis of vegetative/reproductive parts of Nigella sativa L. Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2020;33(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M., AlSalhi M.S., Siddiqui M.K.J. Silver nanoparticle applications and human health. Clinica chimica acta. 2010;411(23–24):1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E., Maamoun, D., Abdelrahman, M. S., Hassan, T. M. and Khattab, T. A. 2023.Imparting cotton textiles glow-in-the-dark property along with other functional properties.

- Ali F., Shahid F., Shahid T. Aqueous Extract of Malus domestica inhibits human platelet aggregation induced by multiple agonists. Phytopharmacological Communications. 2023;3(01):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Amini M., Ghoranneviss M. Effects of cold plasma treatment on antioxidants activity, phenolic contents, and shelf life of fresh and dried walnut (Juglans regia L.) cultivars during storage. Food Science and Technology. 2016;73:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Batool M., Abid A., Khurshid S., Bashir T., Ismail M.A., Razaq M.A., Jamil M. Quality control of nano-food packing material for grapes (Vitis vinifera) based on ZNO and polylactic acid (pla) biofilm. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering. 2022:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Batool R., Kazmi S.A.R., Khurshid S., Saeed M., Ali S., Adnan A., Fatima N. Postharvest shelf life enhancement of peach fruit treated with glucose oxidase immobilized on ZnO nanoparticles. Food Chemistry. 2022;366 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canbolat Y., Rutkowski D., Rutkowski L. Global pattern in hunger and educational opportunity: A multilevel analysis of child hunger and TIMSS mathematics achievement. Large-scale Assessments in Education. 2023;11(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s40536-023-00161-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, R., Heng, K., Shawon, M. S. R., Goh, G., Okonofua, D., Ochoa-Rosales, C., ... & Global Dynamic Interventions Strategies for COVID-19 Collaborative Group. (2020). Dynamic interventions to control COVID-19 pandemic: a multivariate prediction modelling study comparing 16 worldwide countries. European journal of epidemiology, 35, 389-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Daoud D., Douadi T., Hamani H., Chafaa S., Al-Noaimi M. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel by two new S-heterocyclic compounds in 1 M HCl: Experimental and computational study. Corrosion Science. 2015;94:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dewanto V., Wu X., Liu R.H. Processed sweet corn has higher antioxidant activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(17):4959–4964. doi: 10.1021/jf0255937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mernissi Y., Zouhri A., Labhar A., El Menyiy N., El Barkany S., Salhi A., Amhamdi H. Indigenous Knowledge of the Traditional Use of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants in Rif Mountains Ketama District. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2023:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2023/3977622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EL-Mesery H.S., Sarpong F., Atress A.S. Statistical interpretation of shelf-life indicators of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) in correlation to storage packaging materials and temperature. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization. 2022:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat F., Nawaz Khan M., Zafar S.A., Balal R., Azher Nawaz M., Malik A.U., Saleem B.A. Surface coating and modified atmosphere packaging enhance the storage life and quality of Kaghzi lime. Journal of Agricultural science and Technology. 2017;19(5):1151–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Javanmardi J., Stushnoff C., Locke E., Vivanco J.M. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of Iranian Ocimum accessions. Food chemistry. 2003;83(4):547–550. [Google Scholar]

- Kadi R.H. Development of zinc oxide nanoparticles as a safe coating for the shelf life extension of grapes (Vitis vinifera L., Red Globe) fruits. Materials Express. 2023;13(1):182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kamińska I., Lukasiewicz A., Klimek-Chodacka M., Długosz-Grochowska O., Rutkowska J., Szymonik K., Baranski R. Antioxidative and osmoprotecting mechanisms in carrot plants tolerant to soil salinity. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):7266. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10835-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil H. Effects of pre-and postharvest salicylic acid application on quality and shelf life of ‘Flame seedless’ grapes. European Journal of Horticultural Science. 2014;79(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Khan A., Shabir D., Ahmad P., Khandaker M.U., Faruque M.R.I., Din I.U. Biosynthesis and antibacterial activity of MgO-NPs produced from Camellia-sinensis leaves extract. Materials Research Express. 2020;8(1) [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.A., Jarvin M., Sharma S., Umar A., Inbanathan S.S.R., Lalla N.P. Facile and Green synthersis of MgO nanoparticles for the degradation of Vectora blue dye under UV irradiation and their antibacterial activity. ES Food and Agro forestry. 2021;5:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lima M.D.C., de Sousa C.P., Fernandez-Prada C., Harel J., Dubreuil J.D., De Souza E.L. A review of the current evidence of fruit phenolic compounds as potential antimicrobials against pathogenic bacteria. Microbial pathogenesis. 2019;130:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji S., Modak S. Neem: Treasure of natural phytochemicals. Chemical Science Review and Letters. 2021;10:396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Masnilah R., Dewi I.I., Pradana A.P. Antifungal efficacy of piper betle l. and Azadiractha indica a. juss leaves extract in controlling damping-off diseases in groundnut. Pakistan. Journal of Phytopathology. 2023;35(1):145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy S.K., Ashok C.H., Rao K.V., Viswanathan C. Synthesis and characterization of MgO NP’s by Neem leaves through green method. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2015;2(9):4360–4368. [Google Scholar]

- NCBI (2023). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 25212, Magnesium nitrate. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- Rabiei V., Shirzadeh E., Sharafi Y., Mortazavi N. Effects of postharvest applications of calcium nitrate and acetate on quality and shelf-life improvement of “Jonagold” apple fruit. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5(19):4912–4917. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Sharma M.C., Sahu N.K. Simultaneous determination of Nitazoxanide and Ofloxacin in pharmaceutical preparations using UV-spectrophotometric and high performance thin layer chromatography methods. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2017;10:S62–S66. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Prasad S.M. Growth, photosynthesis and oxidative responses of Solanum melongena L. seedlings to cadmium stress: mechanism of toxicity amelioration by kinetin. Scientia Horticulturae. 2014;176:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S.R., Singha A., Faruquee M., Jiku M.A.S., Rahaman M.A., Alam M.A., Kader M.A. Post-harvest assessment of fruit quality and shelf life of two elite tomato varieties cultivated in Bangladesh. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 2019;43:1–12. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.