Abstract

Low‐grade epilepsy‐associated tumors (LEATs) are a common cause of drug‐resistant epilepsy in children. Herein, we demonstrate the feasibility of using tumor tissue derived from stereoelectroencephalography (sEEG) electrodes upon removal to molecularly characterize tumors and aid in diagnosis. An 18‐year‐old male with focal epilepsy and MRI suggestive of a dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNET) in the left posterior temporal lobe underwent implantation of seven peri‐tumoral sEEG electrodes for peri‐operative language mapping and demarcation of the peri‐tumoral ictal zone prior to DNET resection. Using electrodes that passed through tumor tissue, we show successful isolation of tumor DNA and subsequent analysis using standard methods for tumor classification by DNA, including Glioseq targeted sequencing and DNA methylation array analysis. This study provides preliminary evidence for the feasibility of molecular diagnosis of LEATs or other lesions using a minimally invasive method with microscopic tissue volumes. The implications of sEEG electrodes in tumor characterization are broad but would aid in diagnosis and subsequent targeted therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: LEATs, methylation, mutation, sEEG

Key Points.

Tissue extracted from sEEG electrodes can be used to detect molecular abnormalities in LEATs through next generation sequencing and methylation arrays.

Methylation analysis of LEAT DNA from electrodes can be used to effectively study copy number variation.

Development of this technique and could aid in tandem identification of underlying genetic and molecular factors for epilepsy diagnosis and treatment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Low‐grade epilepsy‐associated tumors (LEATs), which include dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNETs) and gangliogliomas (GG), are some of the most common etiologies of drug‐resistant focal epilepsy in children. 1 Resection surgery for LEATs is associated with seizure freedom rates of 80%–90% in appropriately selected patients; however, optimal strategy for localization of the epileptogenic zone and extent of resection remain debated. 2 While many LEATs and associated seizures are “cured” by surgery, pathologic and molecular diagnosis of LEATs provide the basis for long‐term monitoring, prognosis, and tumor therapy if, and when, relapse occurs. Furthermore, advances in less invasive molecular diagnosis of LEATs may lead to targeted tumor therapies, which would obviate the need for traditional surgery and enable LEATs and associated seizures to be treated more selectively.

In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of molecular diagnosis of an epilepsy‐associated DNET via a microbulk brain tissue sample collected from stereoelectroencephalography (sEEG) electrodes. Previously, tissue adherent to sEEG electrodes has been used to diagnose the molecular signature of a periventricular nodular heterotopia, 3 to study mosaic gradients in pathogenic variants, 4 and detecting brain somatic mutations in focal cortical dysplasia. 5 This approach demonstrates that sEEG electrodes (and the tissue remaining after removal) can play a role in diagnosis of tumoral epilepsy, as well as other epilepsy pathologies. This also serves as a proof of principle for the feasibility of molecular diagnosis of LEATs using microbulk tissue volumes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Case report

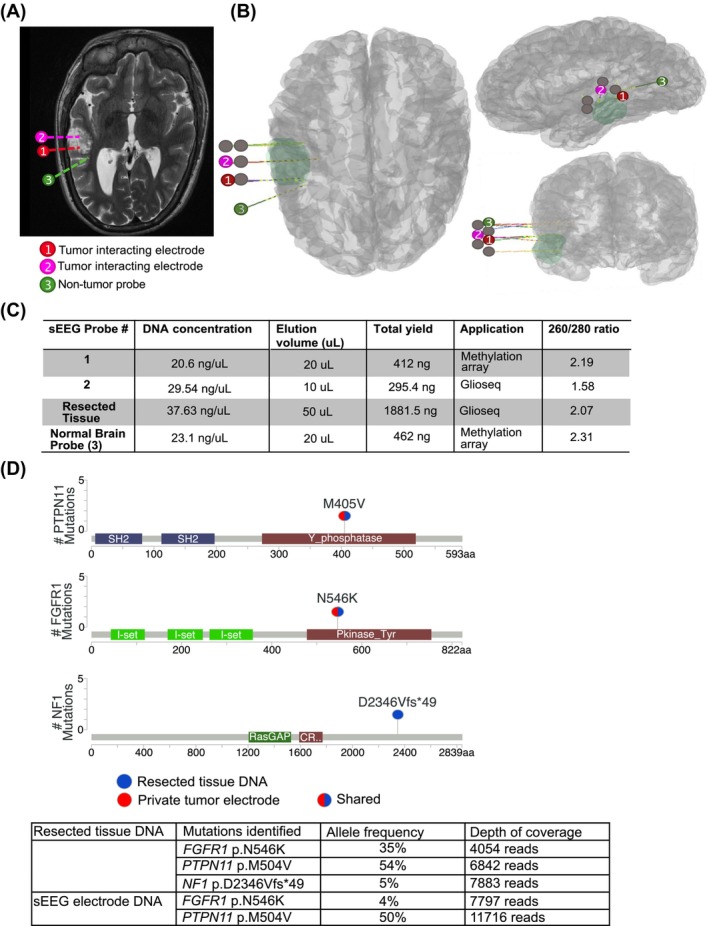

An 18‐year‐old male with Noonan syndrome was previously confirmed via blood genetic analysis to have a heterozygous germline mutation in the Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non‐Receptor Type 11 [PTPN11 c.1510A > G (p.M504V)] gene presented with focal impaired awareness seizures and neuroimaging suggestive of a DNET in the left posterior temporal lobe. The patient was started on anti‐seizure medications and an EEG was obtained, which did not capture seizure‐like activity, but did show rare spike wave discharges arising from the left mid temporal region (T3 > T5). The patient consented to proceed with tumor resection. Given the proximity of the tumor to the language cortex and a relative contraindication to awake language mapping craniotomy, left peri‐tumoral sEEG electrode implantation was planned for perioperative language mapping and delineation of the peri‐tumoral region of interictal discharges (the irritative zone). Seven sEEG electrodes were implanted (two of which passed through tumor tissue) in standard fashion using frameless robot‐assisted technique via percutaneous anchor bolts. 6 Intra‐operative CT was acquired to confirm positioning of electrodes. Figure 1A,B show a merged pre‐operative T2‐weighted MRI and post‐sEEG implant CT demonstrating the positioning of the seven electrodes within the left‐temporal lobe DNET (n = 2) and surrounding temporal lobe (n = 5).

FIGURE 1.

Use of sEEG electrode isolated DNA for Glioseq mutation analysis. (A) T2‐weighted MR image demonstrating relationship of electrode contacts to tumor, highlighting only the electrodes used for this study. (B) 3D renderings of 7 electrode trajectories with tumoral mask. (C) Measurement of isolated DNA from sEEG electrodes and resected tumor tissue. (D) Glioseq mutations detected in sEEG electrode isolated DNA and biopsy resected tissue DNA with allelic frequencies.

Recording in the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit across 4 days captured epileptiform discharges noted most prominently from the electrode on the posterior bank of the tumor and functional mapping demonstrated a language‐positive site on the upper bank. sEEG electrodes were removed in sterile fashion through each anchor bolt and harvested for research. The patient underwent a left temporal craniotomy for language‐sparing tumor resection, leaving a small residual of tumor that coincided with the language‐positive site. Postoperative brain MRI confirmed a small residual DNET.

2.2. DNA‐extraction

Following removal, sEEG electrodes were individually stored in sterile culture tubes and placed on ice. sEEG electrodes were thoroughly washed with 1X PBS, and tissue/blood washed from electrodes were collected in individual microcentrifuge tubes. Samples were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min and resuspended in 200 μL PBS and 20 μL proteinase K. Following initial washing steps, the DNeasy® Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) was employed according to the manufacturer's protocol, with omission of RNase treatment, as RNA was also isolated for use in Glioseq analysis. Nucleic acids were eluted in a 20 μL warm AE buffer, and AE buffer elution was completed twice so as to maximize yield. Extraction was completed in tandem with flash frozen, resected tumor tissue following the same protocol as sEEG electrode DNA extraction. DNA was quantified and analyzed for quality using the Promega Glomax Discover (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained and isolated from patient blood samples, and DNA was extracted following the DNeasy® Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). PBMC DNA was analyzed for FGFR1 mutation using Sanger sequencing with 10 ng of DNA.

2.3. GlioSeq targeted NGS

Genomic DNA isolated from sEEG electrode‐derived samples was used to prepare a next‐generation sequencing (NGS) library. GlioSeq next‐generation sequencing is a custom, amplification‐based, targeted method for molecularly profiling brain tumors. 7 , 8 The GlioSeq (v3) panel consists of DNA and RNA portions. Input for GlioSeq is 10–20 ng of DNA. GlioSeq‐DNA investigates point mutations/SNVs and indels in 47 key brain tumor genes, and copy number changes in >1360 brain tumor‐related hotspots. Additionally, GlioSeq‐RNA can detect structural alterations and gene expression in 103 genes. Validation of this method was completed using Sanger sequencing, in situ hybridization, and RT‐PCR. Sensitivity of this assay is 5% allele frequency for detection of SNVs and short indels. For GlioSeq‐DNA sequencing, raw signal was analyzed using Torrent Suite (v4.4.3) (ThermoFisher, Carlsbad, CA). After signal processing, base calling, and alignment with a reference genome (GRCh37 human reference genome [GCA_000001405.1]), aligned sequences (BAM files) were generated. Variant calling was performed using Torrent Suite Variant Caller.

2.4. Infinium MethylationEPIC array

Methylation data were generated using the Illumina MethylationEPIC (850 k) array platform. Approximately, 250 ng of tumor electrode‐isolated DNA was processed using the Illumina starter equipment (Illumina, San Diego). Sodium bisulfite conversion was completed using the Zymo EZ Methylation Kit (Zymo Research Irvine, USA), and the converted product was purified using the Zymo DNA Clean Kit (Zymo Research Irvine, USA). This DNA was hybridized to an Infinium BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego), and bead chips were scanned using iScan (Illumina, San Diego). iScan output was in the form of raw methylation profiles (.idat files).

2.5. Bioinformatics

Raw methylation profiles (.idat files) were uploaded to the “Classifier” to define a methylation‐based classification of the tumor (www.molecularneuropathology.org). The Classifier, using a reference library of defined CNS tumor profiles, recognizes methylation profiles to classify tumors into distinct tumor entities. 9 Copy number alterations (CNA) and plots were generated from .idat files using the R “conumee” package in Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.orgpackages/release/bioc/html/conumee.html). 10 From .seg files generated in the “conumee” package, more detailed analyses of specific genes within the chromosomal area of interest were performed using Integrative Genomics Viewer. 11

3. RESULTS

3.1. Tumor DNA isolated and extracted from cells attached to sEEG electrodes can be used for Glioseq

We hypothesized that residual tissue on sEEG electrodes could be a potential source of diagnostic material for downstream sequencing applications. We extracted DNA from two sEEG electrodes that passed through tumor tissue (Figure 1A,B), both having sufficient concentration of DNA for methylation analysis (Infinium MethylationEPIC array) and GlioSeq (Figure 1C,D). 12 , 13 We compared the performance of GlioSeq on DNA extracted from resected tumor tissue versus sEEG electrode. GlioSeq of resected tissue identified hotspot mutations in the Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non‐Receptor Type 11 gene (PTPN11 [NG_007459.1] [NM_001330437.2] M405V), Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 (FGFR1 [NG_007729.1] [NM_001174064.2] N546K), and Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1 [NG_009018.1] [NM_000267.3] D2346Vfs*49), which are all observed in pediatric gliomas inclusive of DNETs (Figure 1D). However, NF1 mutation could represent a subclonal mutation or artifact of sequencing, as the mutation represents less than 5% allele frequency. GlioSeq of sEEG electrode‐derived samples also detected the PTPN11 (M405V) and FGFR1 (N546K) mutations (Figure 1D). Only PTPN11 mutation was previously seen in genetic testing, and in order to confirm that FGFR1 was not a germline mutation, Sanger sequencing was completed on DNA isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Sanger sequencing confirmed the wild‐type FGFR1 sequence at this locus, indicating the FGFR1 is a somatic mutation seen in sEEG isolated DNA (Figure S1). Unfortunately, we did not possess enough DNA from resected or probe isolated tissue to complete Sanger sequencing on these samples, but both detected mutation in FGFR1 with Glioseq.

3.2. Tumor DNA isolated from sEEG electrode shafts can be used for methylation classification and copy number variation analysis

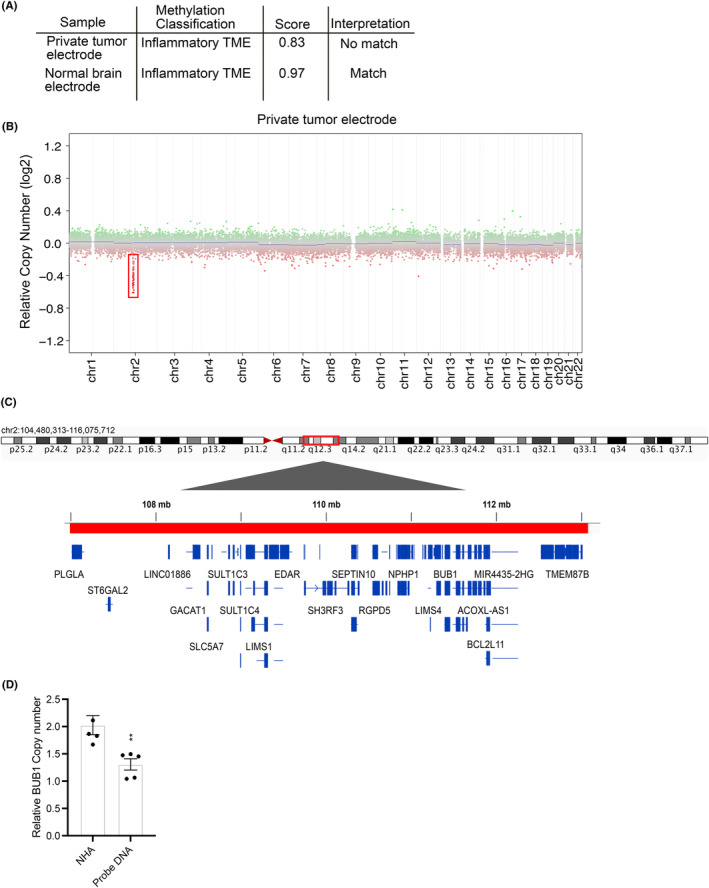

DNA methylation‐based CNS tumor classification is an emerging array for confirming histopathological diagnoses. 14 We had sufficient quantity and quality of DNA from a single electrode to complete an Infinium MethylationEPIC array. Using the Molecular Neuropathology classifier, the tumor classification provided a result of inflammatory tumor microenvironment (TME) but was not interpreted as a high‐confidence match (Figure 2A). To determine whether this was due to poor methylation array or the rarity of DNET methylation arrays available for comparison, we also completed a methylation array on non‐tumor tissue, which confidently matched to TME (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Use of methylation tumor classification to identify class and copy number variation in sEEG electrode isolated DNA. (A) Methylation classification of sEEG electrode isolated DNA. (B) Copy number analysis in isolated tumor DNA. (C) Gene map of chromosome 2q12.3 via integrated genomics viewer. (D) qPCR CNV analysis of BUB1, a gene embedded in chromosome 2q12.3 in prime DNA versus control normal human astrocyte (NHA) cell culture line.**P = 0.0072. Data were normalized to RNAseP housekeeping gene (known to have 1 copy).

DNA methylation arrays can also be used to investigate copy‐number alterations (CNA). The “conumee” R package in bioconductor provides a good overview of gross structural alterations in the tumor genome. 9 CNA analysis from our sEEG electrode identified a bland copy number profile (Figure 2B) with a possible microdeletion in chromosome 2q12.3, which encodes approximately 20 genes (Figure 2C). Deletion of BUB1 Mitotic Checkpoint Serine/Threonine Kinase (BUB1 [NG_012048.2][NM_004336.5]), a gene in this region, was confirmed by using CNA quantitative PCR analysis (Figure 2D). Using this method of CNV analysis, a deep deletion is defined as having a shift from baseline below a ‐log2 value of −0.4, while our potential microdeletion at chromosome 2q12.3 occurs above −0.4, indicating this is likely a shallow deletion. 6 EPIC methylation array was also carried out on probes isolated from control tissue, and the same microdeletion was indicated during CNV analysis, likely suggesting a germline mutation although this is not definitive.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate tissue extracted from sEEG electrodes can be used to detect molecular abnormalities in LEATs, one of the most common causes of drug‐resistant epilepsy. This finding adds to a small group of literature (ie, Montier et al, 2019, Ye et al, 2022, Checri et al, 2023) suggesting sEEG electrodes can be used to identify localized genetic abnormalities. We validate our findings through comparison of tissue analyzed from the electrode to tissue obtained from a subsequent standard resection surgery of that same tissue. Similar to how sEEG electrodes are able to provide minimally invasive, yet direct, exploration of seizure propagation networks, development of this technique may allow for tandem identification of underlying genetic and molecular factors which could contribute to epilepsy diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, use of electrode tissue for Glioseq and methylation arrays could expand our knowledge and serve as diagnostic tools for LEATs or other hard to resect tumors.

We demonstrate successful isolation of LEAT tissue from sEEG electrodes, followed by extraction of brain tissue containing tumor DNA. Glioseq analysis of electrode DNA showed mutations in two genes (PTPN11 M405V and FGFR1 N546K) which were also found in the initial sequencing of resected tumor tissue at an allele frequency within the accurate range of Glioseq. At initial genetic testing for Noonan syndrome diagnosis, this PTPN11 mutation was also found. Both FGFR1 and PTPN11 mutations have been commonly seen in DNETs. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Regarding PTPN11, mutational rates of 54% (resected tissue) and 50% (electrode DNA) are consistent with suggesting a heterozygous germline mutation, consistent with the patient's previous diagnosis of Noonan syndrome. The diagnostic conclusion could be interpreted that, while PTPN11 heterozygous deletion could predispose the patient to tumor development, FGFR1 mutation is somatic and contributes to tumor formation. Although Sanger sequencing did not detect the FGFR1 variant in PBMCs, this could be due to low percentage mosaicism throughout the body, and future studies could include more sensitive techniques for variant validation. Methylation analysis was unable to match tumor DNA extracted from sEEG electrodes to a tumor methylation class. Additionally, electrode DNA was also not matched to tumor microenvironment, indicating that sample methylation was not normal tissue, but could not be specifically matched to a tumor type. This could be due to the heterogeneity of the DNA from differing cell types isolated from the electrode, and the possibility that DNET methylation profiles are not as robust in the classifier as other brain tumors. Control brain from an area not affected by tumor effectively matched to tumor microenvironment, indicating methylation analysis of electrode DNA simply may not be able to match directly to DNET (Figure 2A). Additionally, the use of methylation arrays allows for CNA analysis, which here identified a micro‐deletion in Chr2q12.3 which was validated by qPCR. The 2q12.3 microdeletion is likely a germline mutation or a post‐zygotic/mosaic mutation. Interestingly, the region of 2q deleted in our methylation array overlaps with 2q microdeletion syndrome, a condition that manifests in seizures, developmental delays, and intellectual disability of patients. This highlights the potential for DNA‐methylation arrays in detection of molecular abnormalities in LEATs.

5. LIMITATIONS

The amount of tissue that can be obtained from sEEG depth electrodes is uniformly small, but variable. As such, there are several unique features of obtaining tissue from sEEG electrodes that should be carefully considered. This includes the analysis of possible subclonal tumor populations. Thus, molecular testing studies should be chosen carefully to maximize information obtained from tissue. In the future, electrodes could potentially be customized to retain microscopic amounts of tissue to optimize diagnosis. A limitation of this specific case study is the use of two electrodes (one for glioseq and the other for methylation classification), which could contribute to small differences in tissue or tumor classification. Future work and more cases will allow us to better understand the clinical utility of merging sEEG electrode DNA with NGS.

Secondly, with sEEG electrodes, it cannot be certain from which tissues the material collected along the tract of the electrode originated. While bulk tumor tissue is resected and represents a large tissue sample, sEEG electrodes pass through healthy portions of tissue during implantation and explantation and interact with a small portion of the tumor. For example, a standard orthogonal trajectory to the tumor in our patient may pass through tumor‐free gray matter of the superior temporal sulcus en route to the tumor. When electrodes are removed, the electrode tip passes through this tissue again prior to harvesting, which may make interpretation of molecular abnormalities detected from sEEG electrodes more difficult, particularly as it relates to differences in variant allele frequency. Additionally, differences in VAF for somatic mutations could be due to the small portion of tumor interacting with the probes. With the addition of more cases and use of NGS and methylation arrays, we could further analyze the infiltration of TME or healthy brain into tumor isolated samples. Future work in methodology, such as deconvolution of bulk methylation data, could aid in elucidating how much sEEG isolated DNA is from tumor tissue versus normal brain or microenvironment. In future studies including more cases, somatic variants detected with targeted next‐generation sequencing (GlioSeq) could be orthogonally validated with other sensitive sequencing methods, such as digital droplet PCR (ddPCR). This would exclude possible sequencing artifacts and guarantee true somatic mutation status. In the current study, we chose to confirm mutation status of somatic mutations via Sanger sequencing of PBMCs, however, a more sensitive method of sequencing would include digital droplet PCR, which we were unable to complete in the current study. Additionally, more cases will allow us to better test the clinical utility of merging sEEG electrode DNA with Glioseq or other next‐generation sequencing.

6. CLINICAL RELEVANCE

In conclusion, sEEG electrodes could serve as a useful tool for identifying genetic abnormalities of LEAT tissue in drug‐resistant epilepsy cases. We demonstrate successful isolation of tumor DNA from sEEG electrodes and characterization of tumor with Glioseq and methylation analysis, routine methods of CNS tumor classification.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: SA, TA, TG, and JH. Methodology: TG, SA, and TA. Acquisition of data: TG, JS, MN, and SA. Data curation: TG, JH, BJ, HP, JS, SA, and TA. Writing original draft: TG, JH, SA, and TA. Review and editing: BJ, HP, JS, MN, IP, SA, and TA. Supervision: SA and TA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Figure S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH NINDS R21 NS127064 to McClung and Abel. Agnihotri was funded by NIH NINDS R01 NS115831 and National Cancer Institute CA268634.

Gatesman TA, Hect JL, Phillips HW, Johnson BJ, Wald AI, McClung C, et al. Characterization of low‐grade epilepsy‐associated tumor from implanted stereoelectroencephalography electrodes. Epilepsia Open. 2024;9:409–416. 10.1002/epi4.12840

Taylor J. Abel and Sameer Agnihotri senior authors.

Contributor Information

Taylor J. Abel, Email: abeltj@upmc.edu.

Sameer Agnihotri, Email: sameer.agnihotri@pitt.edu.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blümcke I, Aronica E, Becker A, Capper D, Coras R, Honavar M, et al. Low‐grade epilepsy‐associated neuroepithelial tumours — the 2016 WHO classification. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:732–740. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Englot DJ, Chang EF. Rates and predictors of seizure freedom in resective epilepsy surgery: an update. Neurosurg Rev. 2014;37:389–404. 10.1007/s10143-014-0527-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Montier L, Haneef Z, Gavvala J, Yoshor D, North R, Verla T, et al. A somatic mutation in MEN1 gene detected in periventricular nodular heterotopia tissue obtained from depth electrodes. Epilepsia. 2019;60:e104–e109. 10.1111/epi.16328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ye Z, Bennett MF, Neal A, Laing JA, Hunn MK, Wittayacharoenpong T, et al. Somatic mosaic pathogenic variant gradient detected in trace brain tissue from stereo‐EEG depth electrodes. Neurology. 2022;99:1036–1041. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Checri R, Chipaux M, Ferrand‐Sorbets S, Raffo E, Bulteau C, Rosenberg SD, et al. Detection of brain somatic mutations in focal cortical dysplasia during epilepsy presurgical workup. Brain Commun. 2023;5:fcad174. 10.1093/braincomms/fcad174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abel TJ, Varela Osorio R, Amorim‐Leite R, Mathieu F, Kahane P, Minotti L, et al. Frameless robot‐assisted stereoelectroencephalography in children: technical aspects and comparison with Talairach frame technique. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics PED. 2018;22:37–46. 10.3171/2018.1.Peds17435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Melan MA, Roy S, Zhong S, Hamilton RL, et al. Targeted next‐generation sequencing panel (GlioSeq) provides comprehensive genetic profiling of central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2015;18:379–387. 10.1093/neuonc/nov289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roy S, Agnihotri S, el Hallani S, Ernst WL, Wald AI, Santana dos Santos L, et al. Clinical utility of GlioSeq next‐generation sequencing test in pediatric and young adult patients with brain tumors. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2019;78:694–702. 10.1093/jnen/nlz055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V, Schrimpf D, Sturm D, et al. DNA methylation‐based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555:469–474. 10.1038/nature26000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. conumee: Enhanced copy‐number variation analysis using Illumina DNA methylation arrays. 2017.

- 11. Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Melan MA, Roy S, Zhong S, Hamilton RL, et al. Targeted next‐generation sequencing panel (GlioSeq) provides comprehensive genetic profiling of central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:379–387. 10.1093/neuonc/nov289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roy S, Agnihotri S, el Hallani S, Ernst WL, Wald AI, Santana dos Santos L, et al. Clinical utility of GlioSeq next‐generation sequencing test in pediatric and young adult patients with brain tumors. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78:694–702. 10.1093/jnen/nlz055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karimi S, Zuccato JA, Mamatjan Y, Mansouri S, Suppiah S, Nassiri F, et al. The central nervous system tumor methylation classifier changes neuro‐oncology practice for challenging brain tumor diagnoses and directly impacts patient care. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:185. 10.1186/s13148-019-0766-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.