Abstract

Objective

To assess efficacy and tolerability of stiripentol (STP) as adjunctive treatment in Dravet syndrome and non‐Dravet refractory developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DREEs).

Methods

Retrospective observational study of all children and adults with DREE and prescribed adjunctive STP at Hospital Ruber Internacional from January 2000 to February 2023. Outcomes were retention rate, responder rate (proportion of patients with ≥50% reduction in total seizure frequency relative to baseline), seizure freedom rate, responder rate for status epilepticus, rate of adverse event and individual adverse events, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months and at final visit. Seizure outcomes are reported overall, and for Dravet and non‐Dravet subgroups.

Results

A total of 82 patients (55 Dravet syndrome and 27 non‐Dravet DREE) were included. Median age was 5 years (range 1–59 years), and median age of epilepsy onset was younger in the Dravet group (4.9 [3.6–6] months) than non‐Dravet (17.9 [6–42.3], P < 0.001). Median follow‐up time STP was 24.1 months (2 years; range 0.3–164 months) and was longer in the Dravet group (35.9 months; range 0.8–164) than non‐Dravet (17 months range 0.3–62.3, P < 0.001). At 12 months, retention rate, responder rate and seizure free rate was 68.3% (56/82), 65% [48–77%] and 18% [5.7–29%], respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between groups on these seizure outcomes. Adverse events were reported in 46.3% of patients (38/82), without differences between groups.

Significance

In this population of patients with epileptic and developmental encephalopathies, outcomes with adjunctive STP were similar in patients with non‐Dravet DREE to patients with Dravet syndrome.

Keywords: antiseizure medication, developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, Dravet syndrome, status epilepticus, stiripentol

Key Points.

There are limited treatment options for refractory epileptic encephalopathies (REEs)

STP is approved for adjunctive use in Dravet syndrome, but not in non‐Dravet DREEs

We studied 82 patients (55 with Dravet and 27 with non‐Dravet DREE) for a median of 2 years after addition of STP

We observed a good response to add‐on STP in patients with all types of DREE, without significant differences between the Dravet and non‐Dravet groups

Adjunctive STP may be a treatment option in non‐Dravet DREE

1. INTRODUCTION

Stiripentol (STP) is an antiseizure medication (ASM) approved as add‐on therapy for Dravet syndrome by the European Medicines Agency in 2007 (as add‐on to clobazam and valproate) 1 and by the US Food Drug Administration in 2018 (as add‐on to clobazam). 2 STP was the first drug specifically approved for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, and the only one until the recent approval of cannabidiol (CBD) in 2018 and fenfluramine in 2020 by the European Medicines Agency. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

Multiple mechanisms of action have been proposed for STP, 7 including augmentation of GABAergic neurotransmission, 8 , 9 , 10 modulation of cerebral glucose metabolism by inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase, 11 decreased calcium‐mediated toxicity in hippocampal neurons with NMDA receptors, 12 and inhibition of calcium channels. 13

At the present time, STP is only formally indicated in Dravet syndrome, and although experience in other epilepsies is limited, there is no evidence to suggest that STP has a specific or exclusive action in Dravet syndrome. Because treatment options for severe, refractory developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DREEs) are limited, understanding the efficacy and tolerability of potential new treatment options for non‐Dravet DREEs could clinically valuable.

This study, therefore, was designed to evaluate the outcomes with prescribed add‐on STP in real world clinical practice in patients with Dravet syndrome and in patients with non‐Dravet DREEs, in a retrospective cohort of patients in a tertiary epilepsy center.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

This was a single‐tertiary care center, retrospective, observational study of patients with DREE consecutively treated with STP as add‐on therapy. This was performed under conditions of standard clinical practice in the Epilepsy Program of the Hospital Ruber International in Madrid, Spain, from January 2000 to February 2023. The study was designed and conducted in accordance with all relevant regulations and guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki code of ethics and principles of Good Clinical Practice. Because this was a retrospective study of existing drug, and treatment was indicated based on best clinical options for each patient, there was no need for Ethics Committee approval. The study is reported according to applicable STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. 14

2.2. Participants

All eligible consecutive children and adults with DREE who received treatment with STP as add‐on therapy during the time period in the Epilepsy Program of the Neurology Service in the Ruber International Hospital in Madrid, Spain, were included. Eligibility criteria were diagnosis with DREE, as defined by the International League Against Epilepsy, 15 prescription of add‐on STP by the treating clinician as the most appropriate treatment choice, based on patient profile, epilepsy clinical characteristics and other available therapeutic options and consent of patients. All patients had seizures and neurodevelopmental comorbidities which could be explained by epileptic activity, underlying pathology or both. Etiology was assessed based on clinical history examination, EEG, brain imaging and genetic testing in all patients. In addition, metabolic studies were preformed when necessary.

Patients were divided into two groups depending on the epileptic syndrome of the DREE: (1) refractory epileptic encephalopathies due to Dravet syndrome; (2) refractory epileptic encephalopathies due to etiologies other than Dravet syndrome (non‐Dravet DREE). Non‐Dravet DREE patients were sub‐classified based on their epilepsy etiology, according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) operational classification. 12

2.3. Treatment

STP was initiated according to the titration schedule included in the Summary of Product Characteristics and as per the discretion of the physician, to an optimal maintenance dose that was adjusted by each clinician based on clinical response and tolerability. Routine clinical monitoring of plasma levels of other ASMs was performed at the treating physician discretion, and dosage of other ASMs adjusted based on predicted drug–drug interactions, adverse events and efficacy.

2.4. Data collection

Baseline demographics, physical examination, weight, vital signs, medical history, including history of patients' seizures, seizure type and epilepsy syndrome, seizure frequency, prior treatment and ASM prescription were retrospectively collected from the epilepsy database of our hospital.

Medications were recorded at each visit (STP dose, and number and type of concomitant ASMs). The numbers of monthly seizures and seizure days (documented each month or as a monthly average since the previous 3‐month review by the clinician) were obtained from case notes or seizure diaries if available. Baseline seizure and status epilepticus frequency was determined from the seizure frequency before the start of STP. Adverse events (AEs) were collected based on the reports recorded in the clinical notes.

End of follow‐up was considered by default at 36 months after the start of STP. When patients discontinued the treatment or clinical tracking was lost, the last recorded visit was considered as the end of follow‐up. For each case, the time of discontinuation and time of last follow up was registered.

Final cognitive status, seizure and status epilepticus frequency were assessed at the end of the follow‐up period or after the discontinuation of the treatment in those who discontinued STP.

2.5. Outcomes

2.5.1. Retention

Discontinuation was defined as the time point at which medication was stopped, while censoring was considered when the follow up was lost. Reasons for discontinuation, as well as length of treatment (time in months between the start of the treatment and the last evaluation) was calculated for each case. Retention rates were calculated at 3, 6 and 12 months following an intention‐to‐treat approach, as the number of patients on treatment divided by the total number of patients at the start of the follow‐up. Analysis of the retention rates was performed through a survival analysis, considering discontinuation as the event of interest.

2.5.2. Efficacy assessments

All types of seizures were counted and status epilepticus was counted separately. Baseline seizure frequency was calculated as the mean seizure frequency over the 3 months before STP initiation. Monthly seizure frequency was recorded at each visit.

Change in seizure frequency was calculated as difference between seizure frequency at each visit since baseline, divided by the baseline seizure frequency. Patients were considered responders when the seizure frequency was reduced at least a 50% and seizure free when a 100% reduction of baseline seizure frequency was achieved. For each patient, the time when the patient first reached the 50% reduction, the 90% reduction and the seizure free status was registered. In patients who never reached the outcome, the last follow up was considered as the censor time. For the estimation of responder and seizure free rates at 3, 6, 12 and 36 months, a survival analysis was performed considering the first achievement of 50% or 100% reduction as the event.

Status epilepticus outcomes were assessed before the start of STP and at the end of follow up in patients who had at least one episode of status during the 3 months before STP initiation. Status epilepticus was defined as a seizure lasting at least 30 min or a series of epileptic seizures during which function is not regained between ictal events in a 30‐min period. Status responder rate and status‐free rate was defined at the end of follow up period as the percentage of participants with a ≥50% and 100% reduction in frequency of status episodes relative to baseline, respectively.

Improved cognition was defined as improvement in attention and/or language defined subjectively by the physician based on examination and caregiver's reports in the last follow up visit.

2.5.3. Safety and tolerability assessments

All adverse events were collected verbatim and translated into standard terms. Regarding serious adverse events, just death was registered.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize continuous variables (mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range). Absolute frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables.

Demographics, status epilepticus and cognitive outcomes were compared between Dravet syndrome and non‐Dravet DREE groups using Chi‐Square, Fisher or Wilcoxon test as appropriate. Responder, seizure‐free and retention rates were estimated employing a survival analysis, fitting a Kaplan–Meier curve for each outcome. Survival probability was employed for retention rates, considering discontinuation as the event of interest. Responder rates and seizure‐free rates were estimated through the risk probability estimator, considering achieving a 50% or 100% reduction of baseline frequency as the event. For each outcome, the 95% confidence interval was estimated at 3, 6, 12 and 36 months after the start of follow‐up. Comparisons in responder, seizure free and retention rates between Dravet and non‐Dravet groups were performed fitting a Cox proportional hazards model. For the analysis, a 95% level of confidence and a bilateral alpha value of 0.05 were considered.

Individual missing data were excluded from the analysis. Loss to follow‐up was considered in the analysis, recording each follow‐up period. Statistical analyses were performed with R 3.1.2 software. 16

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

82 patients received STP as add‐on treatment for DREE: 55 for Dravet syndrome (67%), and 27 for non‐Dravet DREE (32.9%).

Clinical and demographic characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. Of the overall population, 43 patients were female (43/82, 52.4%) and the age ranged from 1.1 to 59.8 years (median 10 years). The median age of epilepsy onset was 5 months (range 0.5–264 months). Most patients had multiple seizure types (70/82, 85.4%): focal to bilateral tonic–clonic or secondary generalized tonic–clonic (SGTC) seizures were the most common type (58/82, 70.7%), followed by focal seizures (50/82, 60.9%) and absences (41/82, 50%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort.

| All (N = 82) | Dravet syndrome (N = 55) | Non‐Dravet DREE (N = 27) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the start of STP (months), median [IQR] | 62.1 [35.2;152] | 52.5 [32.2;118] | 114 [49.8;183] | 0.035 |

| Age at the start of epilepsy (months), median [IQR] | 5.00 [3.90;9.82] | 4.90 [3.60;6.00] | 17.9 [6.00;42.3] | <0.001 |

| Sex (female), N (%) | 43 (52.4%) | 27 (49.1%) | 16 (59.3%) | 0.528 |

| Disability | ||||

| No disability | 10 (12.2%) | 8 (14.5%) | 2 (7.41%) | 0.207 |

| Mild disability | 38 (46.3%) | 28 (50.9%) | 10 (37.0%) | |

| Moderate to severe disability | 34 (41.5%) | 19 (34.5%) | 15 (55.6%) | |

| Seizures | ||||

| Absences | 41 (50%) | 29 (52.3%) | 12 (48.1%) | 0.638 |

| Secondary TCS | 58 (70.7%) | 45 (81.8%) | 13 (44.4%) | <0.001 |

| Focal | 50 (60.9%) | 37 (67.3%) | 13 (48.1%) | 0.147 |

| Other | 45 (54.8%) | 25 (45.4%) | 20 (74.1%) | 0.01 |

| Follow up on STP (months), median (range) | 24.1 [0.3;164] | 35.9 [0.8;164] | 17.0 [0.3;62.9] | 0.007 |

| Dose STP total (mg), median [IQR] | 750 [500;1000] | 750 [500;1000] | 812 [500;1000] | 0.632 |

| Adjusted dose STP (mg/kg), median [IQR] | 38.5 [22.3;46.9] | 38.9 [23.9;48.1] | 30.0 [19.2;44.1] | 0.167 |

| Number of ASM at the start of STP, median (range) | 3 (1;6) | 3 (1;6) | 3 (2–5) | 0.166 |

| Baseline monthly seizure frequency (seizures per month), median [IQR] | 4.64 [2.19;30.0] | 3.33 [1.88;6.00] | 60.0 [22.5;150] | <0.001 |

| Number of status epilepticus before STP (only in patients with at least 1 status), median (range) | 2 (1;15) | 2 (1; 15) | 3 (1; 4) | 0.217 |

| Concomitant ASM | ||||

| Valproic acid, n (%) | 71 (86.6%) | 51 (92.7%) | 20 (74.1%) | 0.035 |

| Levetiracetam, n (%) | 19 (23.2%) | 13 (23.6%) | 6 (22.2%) | 1.000 |

| Clobazam, n (%) | 47 (57.3%) | 36 (65.5%) | 11 (40.7%) | 0.059 |

| Topiramate, n (%) | 18 (22.0%) | 17 (30.9%) | 1 (3.70%) | 0.012 |

| Zonisamide, n (%) | 3 (3.66%) | 2 (3.64%) | 1 (3.70%) | 1.000 |

| Ethosuximide, n (%) | 6 (7.32%) | 3 (5.45%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.390 |

| Lamotrigine, n (%) | 11 (13.4%) | 2 (3.64%) | 9 (33.3%) | 0.001 |

| Rufinamide, n (%) | 5 (6.10%) | 1 (1.82%) | 4 (14.8%) | 0.038 |

| Perampanel, n (%) | 6 (7.32%) | 2 (3.64%) | 4 (14.8%) | 0.088 |

| Oxcarbazepine, n (%) | 1 (1.22%) | 1 (1.82%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.000 |

| Steroids, n (%) | 3 (3.66%) | 1 (1.82%) | 2 (7.41%) | 0.251 |

| Fenfluramine, n (%) | 2 (2.44%) | 2 (3.64%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.000 |

| Cannabidiol, n (%) | 7 (8.54%) | 6 (10.9%) | 1 (3.70%) | 0.416 |

| Briviact, n (%) | 6 (7.32%) | 1 (1.82%) | 5 (18.5%) | 0.014 |

| Lacosamide, n (%) | 4 (4.88%) | 1 (1.82%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.102 |

| Clonazepam, n (%) | 10 (12.2%) | 4 (7.27%) | 6 (22.2%) | 0.073 |

| Phenytoin, n (%) | 2 (2.44%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (7.41%) | 0.106 |

| Phenobarbital, n (%) | 2 (2.44%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (7.41%) | 0.106 |

Dravet syndrome was diagnosed, based on the ILAE definition. A variant in the SCN1A gene was identified in 45/55 (81.8%) patients, missense variants being the most frequent (28/45, 62.2%) followed by truncating variants (14/45, 31.1%) and others (3/45, 6.6%).

Of the 27 patients in the non‐Dravet DREE group, a genetic diagnosis was achieved in 10/27 (37%; Table 2), and a specific syndromic diagnosis was possible in 13/27 (48.1%): Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in 8, myoclonic atonic epilepsy (Doose syndrome) in three and malignant migrating partial epilepsy of infancy in two. Genetic variants in the non‐Dravet DREE group are shown in Table S1. The two cases with malignant migrating partial epilepsy were diagnosed by the electro‐clinical phenotype and in one it was confirmed by a mutation in the KCN2 gene. Regarding the three cases affected by Doose syndrome all of them were diagnosed by the electro‐clinical picture, and in one a mutation in the SLC2A1 gene was detected. The other etiologies in the non‐Dravet DREE group were structural (4/27, 14.8%) and idiopathic (13/27, 48.1%).

TABLE 2.

Clinical outcomes.

| All (n = 54) | Dravet (n = 30) | Non Dravet (n = 24) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responder rate | ||||

| 3 months (%, 95%CI) | 36% [21–49%] | 38% [17–54%] | 34% [9.7–52%] | 0.4 |

| 6 months (%, 95%CI) | 55% [38–68%] | 58% [34–73%] | 51% [22–69%] | |

| 12 months (%, 95%CI) | 65% [48–77%] | 66% [42–81%] | 63% [32–80%] | |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | – | 0.76 [0.39–1.49] | ||

| 90% reduction | ||||

| 3 months (%, 95%CI) | 14% [3.9–24%] | 14% [0.3–26%] | 15% [0–29%] | 0.4 |

| 6 months (%, 95%CI) | 28% [14–40%] | 26% [7.3–41%] | 31% [6.7–49%] | |

| 12 months (%, 95%CI) | 33% [18–46%] | 26 [7.3–41%] | 43% [15–62%] | |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | – | 1.44 [0.58–3.56] | ||

| Seizure free | ||||

| 3 months (%, 95%CI) | 8.3% [0.2–16%] | 7.1 [0–16%] | 10% [0–23%] | 0.8 |

| 6 months (%, 95%CI) | 15 [4.1–25%] | 15% [0.2–27%] | 16% [0–30%] | |

| 12 months (%, 95%CI) | 18% [5.7–29%] | 15% [0.2–27%] | 22 [0.1–39%] | |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | – | 0.87 [0.29–2.6] | ||

| Status epilepticus | ||||

| ≥50% reduction (n, %) | 11/13 (84.6%) | 8/8 (100%) | 3/4 (66%) | 0.33 |

| Status epilepticus free (n, %) | 8/13 (61.5%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | 3/4 (66%) | 1 |

| Other outcomes | ||||

| Cognitive improve (n, %) | 13/54 (24.1%) | 9/30 (30%) | 4/24 (16%) | 0.35 |

| Number of ASM at the end of the study, median (range) | 3 (0–5) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (0–5) | 0.82 |

| Discontinuation of ≥1 ASM (n, %) | 9/54 (16.7%) | 3/30 (10%) | 6/24 (25%) | 0.16 |

| Discontinuation of ≥2 ASM (n, %) | 5/54 (9.2%) | 1/30 (3.3%) | 4/24 (16.7%) | 0.15 |

There was a statistically significant difference between Dravet and non‐Dravet DREE groups in the age of epilepsy onset (4.9 [3.6–6] vs 17.9 [6–42.3] months, Wilcoxon test P < 0.001), age of the start of STP (52.5 [32.2–118] vs 114 [49.8–183] months, Wilcoxon test P = 0.035), proportions with SGTC seizures (45/55, 81.8% vs 13/27, 48.1%, Fisher test P = 0.004) and seizure frequency at baseline (3.3 [1.8–6] vs 60 [22.5–150] over 3 months, Wilcoxon test P < 0.001).

The median number of concomitant ASMs at STP onset was 3 (range 1–6): being valproate the most commonly used concomitant ASMs (71/82, 86.6%), followed by clobazam (47/82, 57.3%) and levetiracetam (19/82, 23.3%). Differences in baseline treatments between Dravet and non‐Dravet cohorts are found in Table 1.

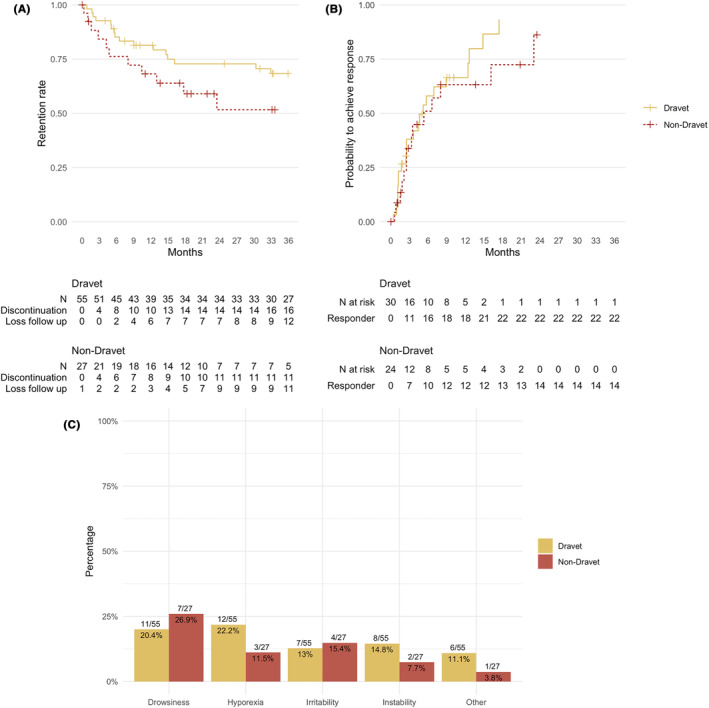

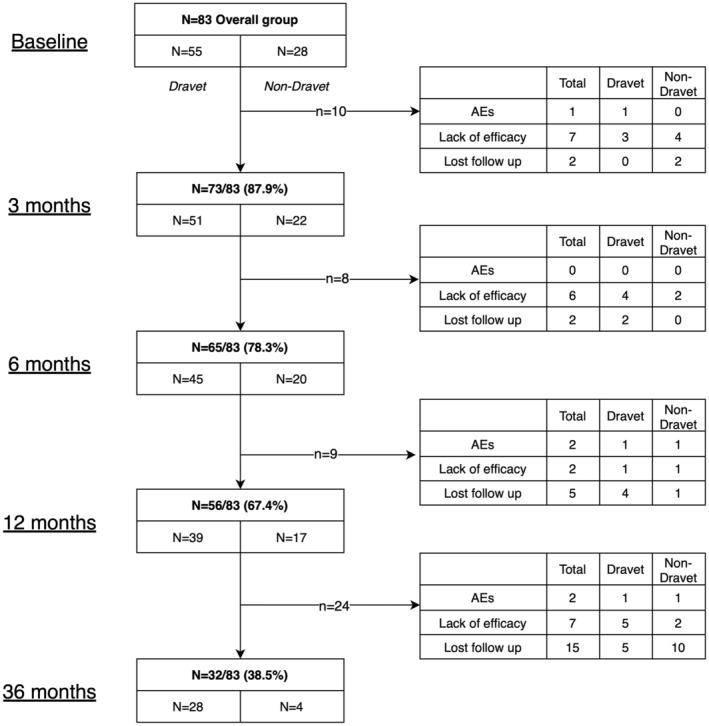

3.2. STP exposure and retention

The median STP maintenance dose was 38.5 mg/kg/day (IQR 22.4–46.9 mg/kg/day). In 1/82 patients, only the initial information was available due to loss of follow up. In the remaining 81 patients (55 Dravet, 26 non‐Dravet DREE), median duration of follow up with STP treatment was 24.8 months (~2 years; range 0.3–164 months), equivalent to a total of 267 patients‐year of exposure. Differences in time of exposure were found depending on group of the DREE, being longer in the Dravet subgroup (median 35.9 months, range 0.8–164 months) than the non‐Dravet DREE group (17.3 months, range 0.3–62.9 months, Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001). Cox regression analysis showed no statistically significant differences in retention over time between both groups (Hazard ratio (HR) for non‐Dravet vs Dravet 2.01 [0.98–4.13], P = 0.06; Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Outcomes in the study. Panel (A) shows the survival analysis of the retention rates between groups. Panel (B) shows the probability to achieve a 50% seizure reduction. Panel (C) shows the adverse events in the study.

The retention rate at 3 months was 87.8% (72/82), at 6 months 78% (64/82), and at 12 months was 68.3% (56/82). The reasons for discontinuation are shown in Figure 2. At the final visit (up to 36 months), 32 patients were ongoing on STP, 27 had discontinued STP (retention rate 32/82 39%) and 23 were lost to follow‐up. The reasons for discontinuation were AEs (6/27, 18.5%) and lack of efficacy (21/27, 77.7%).

FIGURE 2.

Causes of withrawal over time according to groups of patients.

3.3. Efficacy

Information about seizure frequency was available in 82 patients, of whom 1 of them was already seizure free at the start of the follow‐up. In this patient, STP was initiated due to the presence of language problems associated with continuous spike waves during sleep. In 27 patients, STP was initiated prior to the first visit. As the time of the start of STP could not be ascertained in these patients, they were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 54 patients (30 Dravet, 24 Non‐Dravet), the median number of seizures before the initiation of STP was 8 seizures per month (IQR 3–60). Clinical outcomes (responder rate, seizure‐free rate, status epilepticus response, status epilepticus‐free rate and cognitive status) at each time point are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1B.

In the remaining 54 patients, the responder rates at 3, 6, 12, and 36 months were 36% (95% CI [21–49%]), 55% (95% CI [36–68%]), 65% (95% CI [48–77%]) and 83% (95% CI [69–91%]), respectively, while seizure‐free status was achieved in 8.3% [0.2–16%], 15% [4.1–25%], 18% [5.7–29%], and 25% [9.7–38%] of patients, respectively. Additionally, a 90% response was observed in 14% [3.9–24%], 28% [14–40%], 33 [18–46%], and 52% [28–68%] of patients at 3, 6, 12, and 36 months, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in responder rate between non‐Dravet and Dravet subgroups (HR for non‐Dravet 0.76 [0.39–1.49], P = 0.4), 90% response (HR 1.44 [9.58–3.56], P = 0.4), or seizure‐free rate (HR 0.87 [0.29–2.6], P = 0.8) over time between Dravet and non‐Dravet DREE subgroups.

Regarding efficacy in subgroups, responder rate, 90% response and seizure free rates at 12 months in the Lennox Gastaut group were not statistically significant different than those of the Dravet group (HR for responder rate 0.83 [0.31–2.21], P = 0.7, HR for 90% response 1.36 [0.37–5.00] P = 0.6, HR for seizure‐free 0 [0‐Inf] P > 0.9). In two out of three patients diagnosed with myoclonic atonic epilepsy and in one out of two with malignant migrating partial epilepsy of infancy, seizure freedom was achieved. Regarding genetic variants, no differences in outcomes could be found depending on the affected gene nor the type of genetic variation (Tables S1 and S2).

The change in status epilepticus frequency could be assessed in 12 patients who had history of status epilepticus at baseline: in the final evaluation 11 were responders (91.6%), and 8 (66.7%) were free of epileptic status. No differences between Dravet and non‐Dravet groups were found in status epilepticus responder rate (P = 0.33) nor status‐free rate (P = 1).

Overall, 16.7% of the patients (n = 9) could discontinue at least one ASM at the end of follow‐up. No statistically significant differences between groups were found in the adjustment of other concomitant ASMs at the end of the study (10% in Dravet vs 25% in non‐Dravet could discontinue one ASM, P = 0.16). Also, in 13 patients (24.1%) a cognitive improvement was clinically noted, without statistically significant differences between syndromic groups (30% vs 16% P = 0.35).

3.4. Tolerability and safety

Out of the whole cohort of 82 patients, 38 (46.3%) reported at least one AE during STP treatment, but just 6 (7.3%) discontinued STP as a result of AEs. The most common AEs were drowsiness (18/82, 21.9%), reduced appetite (15/82, 18.3%), irritability (11/82, 13.4%) and gait instability (10/82, 12.2%). AEs were not statistically significant different between Dravet and non‐Dravet subgroups (Fisher test, P = 0.632), as shown in Figure 1C. Regarding the Lennox–Gastaut group, 5/8 demostrated at least one AE, being the most common drowsiness (2/8) and irritability (2/8) followed by other (1/8), without differences with the Dravet group (Fisher test, P = 0.39). Two patients in the Dravet group died during the follow‐up due to infectious pneumonia, which was not considered related to the medication.

4. DISCUSSION

In our cohort of 55 patients with Dravet syndrome and 27 with non‐Dravet DREE, add‐on STP (median dose 38.5 mg/kg/day) was maintained for a median of 2 years, with a 12‐month retention rate of 67.4%. Seizure outcomes were not different between the two groups, with an estimated responder rate and seizure‐free rate of 60% [45–70%] and 16% [6.2–24%] at 12 months. Of 12 patients with status epileptic episodes at baseline, freedom from status epilepticus was achieved in 66.7% at final visit. AEs occurred in 46.3% of patients but only 6 patients (7.3%) discontinued STP as a result. The most common AEs were somnolence (21.9%), reduced appetite (18.3%) and irritability (13.4%).

Outcomes in this study in patients with Dravet syndrome are consistent with previous data in this population, obtained from pivotal trials 17 and longer‐term follow‐up, 18 , 19 , 20 which have reported responder rates between 47 and 71%. In a retrospective study of add‐on STP in patients with various types of refractory epilepsies (including Dravet syndrome and other genetic etiologies), 21 30 of 132 patients had Dravet syndrome and 19 had non‐Dravet genetic epilepsies. Overall, the response rate was 50%, with 13 patients (9.8%) becoming seizure‐free. Interestingly, the genetic etiology group (n = 49, of whom 30 had Dravet syndrome) had a higher responder rate than the overall group. In a subsequent analysis of the same cohort, 22 which added 64 new patients, responder rate was confirmed to be around 68% [58–77%] at 12 months, consistent with our responder rate of 60% [45–70%] at 12 months.

Furthermore, retention rates at 12 months for STP are consistent with other similar cohorts who reported a 53% 22 and were comparable to other drugs employed in the treatment of DREE such as valproate (78%), 23 lamotrigine (69%), 24 clobazam (67–51%), 24 , 25 and cannabidiol (61.4%), 26 and higher than others such as vigabatrin (55%), 27 brivaracetam (41%) 28 and topiramate (37%), 24 which may be explained by the good balanced profile of tolerability and efficacy in this cohort.

Within our small sample, we were unable to find differences in outcomes and retention rates between the Dravet syndrome group and the non‐Dravet DREE group. This lack of differences contrasts with the Balestrini study, 22 which found a beneficial effect of STP in the Dravet group in terms of outcomes and retention. The lack of differences in response rates between the two groups in our study may be due to the smaller number of patients in the non‐Dravet group, which may have reduced the statistical power of our analysis. However, other strengths emerge in comparison with the Balestrini study. 22 Although our non‐Dravet group is heterogeneous, the number of patients with non‐specified DREE was smaller (12/83, 14.4%) compared to the Balestrini study (33%). These findings point towards a more homogeneous cohort in our case, which supports the validity of our results.

Despite the limited number of patients, we identified some notable differences between the two groups. The Dravet group had a lower age of epilepsy onset and a younger age of STP initiation compared to the non‐Dravet DREE group, which likely reflects the early onset of Dravet syndrome and the diverse etiologies within the non‐Dravet group. Furthermore, the Dravet syndrome group had a longer duration of STP treatment, likely due to the earlier onset of this disease and the approval of STP for this indication, while it is not approved in non‐Dravet DREEs. The differences in proportions of SGTC seizures or baseline seizure frequency may be attributed to the heterogeneous clinical and genetic characteristics of the non‐Dravet DREE group.

Interestingly, we found an excellent response in two out of three patients with myoclonic atonic epilepsy. Both of them achieved seizure freedom and were eventually off medication after the addition of STP and reduction of background medication (valproic acid, ethosuximide and clobazam). While this is a small number of patients, we could argue that because of its mechanism of action as a modulator of cerebral glucose metabolism, 11 STP may mimic the effect of the ketogenic diet, a first‐line therapy in this epileptic syndrome. 29 Also, in our series one patient with severe migrating focal epilepsy of infancy achieved complete seizure control with STP associated with levetiracetam and clonazepam, an outcome previously reported by Merdariu et al. 30 No differences could be found in efficacy or AE between the Dravet and Lennox–Gastaut groups, although this analysis is strongly underpowered due to the small number of cases in the Lennox–Gastaut group.

Few previous studies have explored add‐on STP in non‐Dravet DREEs, despite a multi‐faceted mode of action that is proposed to target long‐lasting tonic inhibition, 31 glucose metabolism, 11 excitotoxicity, 12 and inhibition of calcium channels. 13 STP potentiates GABA inhibition via GABAA receptors containing the gamma subunit but also those containing the delta subunit, which modulate long‐lasting tonic inhibition in response to low ambient levels of GABA. This suggests that STP could be especially effective in prolonged epileptic status. 31 STP also inhibits lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), leading to decreased pyruvate–lactate–ATP conversion and effects on cerebral glucose metabolism. 11 This pathway is not known to be targeted by any other ASMs but is modulated by the ketogenic diet. STP also has possible neuroprotective effects, decreasing high glutamate‐mediated toxicity in hippocampal neurons and decreasing neuronal injury following status epilepticus. 12 Finally, STP inhibits T‐type calcium channels, involved in thalamo‐cortical oscillations, leading to decreased absence seizures. 13 Despite this strong neurobiological rationale, the clinical experience with STP treatment in non‐Dravet DREEs is limited. STP has been studied in other epilepsy types, including refractory focal and generalized epilepsies, 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 super‐refractory status epilepticus and malignant migrating partial epilepsy of infancy, 30 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 with beneficial results. Given this efficacy and the lack of solid evidence, further prospective studies are needed to explore the efficacy and tolerability of this drug in the treatment of DREE.

STP was in general well tolerated in our study, being the most common adverse events drowsiness and loss of apetite, as described in the early clinical trials of the drug. 17 Although the tolerability in our study was better than in the seminal clinical trial (38/84 with at least one AE; 46.3%), where all but one of the stiripentol recipients (32/33; 97%) experienced one or more AEs, it was significantly higher than in the real‐world data reported by Balestrini (38/196; 19.4%). Although we cannot know the exact causes of these differences, we hypothesize factors such as dosage, concomitant ASM or methods to report AEs can be responsible of these differences.

An additional complication when interpreting clinical outcomes with STP is its inhibition of CYP450 enzymes, which can lead to interactions with many ASMs and necessitate changes in baseline ASM dosing. Of note, STP increases the levels of clobazam and its active metabolite, norclobazam. 40 However, the beneficial effect of add‐on STP in patients receiving clobazam is not solely due to increased levels of these compounds. 41 We did not control for the concomitant use of ASM (such as clobazam) or other variables that could potentially impact the efficacy of STP, which may be a limitation of our study.

Our study has some limitations, including its retrospective design, the small sample size, and differences in demographics and background ASM use between the Dravet syndrome and non‐Dravet DREE groups. Given the small sample size, we acknowledge our study may be underpowered to detect statistically significant differences, and that other previous studies have already studied the drug in real world. However, given the relative rarity of epileptic encephalopaties and the scarcity of available data, our series provide a significant contribution to the literature.

5. CONCLUSION

This study evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of add‐on STP in patients with Dravet syndrome and non‐Dravet DREE. We observed a good response to add‐on STP in patients with all types of DREE, without significant differences between the Dravet and non‐Dravet groups. Treatment options are limited for patients with rare and serious DREEs. Although further prospective studies are needed, our findings suggest that add‐on STP may be a therapeutic option for many patients with DREE, not just those with Dravet syndrome.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Antonio Gil‐Nagel conceived and designed the study, visited patients, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; Adrian Valls‐Carbó, Adolfo Jiménez‐Huete and Laura Martínez‐Vicente wrote the statistical analysis plan and analyzed data; Angel Aledo‐Serrano visited patients, collected and analyzed data; Rafael Toledano‐Delgado and Irene García‐Morales visited patients, and all authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Antonio Gil‐Nagel has received research support from Biocodex, GW‐Pharmaceuticals, PTC Therapeutics, and Zogenix and has served as a paid consultant and/or received speaker fees from Angelini, Bial, Eisai, Esteve, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Stoke, UCB Pharma, and Zogenix. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest. Editorial support was provided by Kate Carpenter and funded by Neurociencias Aplicadas. All the authors confirm that have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Table S1.

Table S2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the clinical staff and study coordinators for collecting data and ensuring completeness and accuracy of information. We thank the patients and family members who participated in the study.

Gil‐Nagel A, Aledo‐Serrano A, Beltrán‐Corbellini Á, Martínez‐Vicente L, Jimenez‐Huete A, Toledano‐Delgado R, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of add‐on stiripentol in real‐world clinical practice: An observational study in Dravet syndrome and non‐Dravet developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Epilepsia Open. 2024;9:164–175. 10.1002/epi4.12847

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data can be accessible to other researchers through a reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. European Medicines Agency . EPAR summary for the public, STP. [Accessed 2023 Mar 13]. Available from www.ema.europa.eu

- 2. Food and Drug Administration . Drug Approval Package: Diacomit (STP). [Accessed 2023 Mar 13]. Available from www.fda.gov/medwatch

- 3. European Medicines Agency . Epidyolex (cannabidiol): An overview of Epidyolex and why it is authorised in the EU. [Accessed 2023 Mar 13]. Available from www.ema.europa.eu/contact

- 4. Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, Marsh E, Miller I, Nabbout R, et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug‐resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2011–2020. 10.1056/NEJMOA1611618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lagae L, Sullivan J, Knupp K, Laux L, Polster T, Nikanorova M, et al. Fenfluramine hydrochloride for the treatment of seizures in Dravet syndrome: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10216):2243–2254. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32500-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fintepla|European Medicines Agency. [Accessed 2023 Mar 13]. Available from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/fintepla#authorisation‐details‐section

- 7. Grosenbaugh DK, Mott DD. Stiripentol in refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2013;54(SUPPL. 6):103–105. 10.1111/EPI.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frampton JE. Stiripentol: a review in Dravet syndrome. Drugs. 2019;79(16):1785–1796. 10.1007/S40265-019-01204-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fisher JL. The anti‐convulsant stiripentol acts directly on the GABA(a) receptor as a positive allosteric modulator. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):190–197. 10.1016/J.NEUROPHARM.2008.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vasquez A, Wirrell EC, Youssef PE. Stiripentol for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome in patients 6 months and older and taking clobazam. Expert Rev Neurother. 2023;23(4):297–309. 10.1080/14737175.2023.2195550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sada N, Lee S, Katsu T, Otsuki T, Inoue T. Epilepsy treatment. Targeting LDH enzymes with a stiripentol analog to treat epilepsy. Science. 2015;347(6228):1362–1367. 10.1126/SCIENCE.AAA1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verleye M, Buttigieg D, Steinschneider R. Neuroprotective activity of stiripentol with a possible involvement of voltage‐dependent calcium and sodium channels. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94(2):179–189. 10.1002/JNR.23688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riban V, Heulard I, Reversat L, Si Hocine H, Verleye M. Stiripentol inhibits spike‐and‐wave discharges in animal models of absence seizures: a new mechanism of action involving T‐type calcium channels. Epilepsia. 2022;63(5):1200–1210. 10.1111/EPI.17201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. 10.1016/J.JCLINEPI.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E, Jansen FE, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the international league against epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):522–530. 10.1111/EPI.13670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Core Team; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiron C, Marchand MC, Tran A, Rey E, d'Athis P, Vincent J, et al. Stiripentol in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy: a randomised placebo‐controlled syndrome‐dedicated trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9242):1638–1642. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiron C, Helias M, Kaminska A, Laroche C, de Toffol B, Dulac O, et al. Do children with Dravet syndrome continue to benefit from stiripentol for long through adulthood? Epilepsia. 2018;59(9):1705–1717. 10.1111/EPI.14536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Myers KA, Lightfoot P, Patil SG, Cross JH, Scheffer IE. Stiripentol efficacy and safety in Dravet syndrome: a 12‐year observational study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(6):574–578. 10.1111/DMCN.13704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yıldız EP, Ozkan MU, Uzunhan TA, Bektaş G, Tatlı B, Aydınlı N, et al. Efficacy of stiripentol and the clinical outcome in Dravet syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2019;34(1):33–37. 10.1177/0883073818811538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosati A, Boncristiano A, Doccini V, Pugi A, Pisano T, Lenge M, et al. Long‐term efficacy of add‐on stiripentol treatment in children, adolescents, and young adults with refractory epilepsies: a single center prospective observational study. Epilepsia. 2019;60(11):2255–2262. 10.1111/EPI.16363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Balestrini S, Doccini V, Boncristiano A, Lenge M, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Efficacy and safety of long‐term treatment with Stiripentol in children and adults with drug‐resistant epilepsies: a retrospective cohort study of 196 patients. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2022;9(3):451–461. 10.1007/S40801-022-00305-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heger K, Lund C, Larsen Burns M, Bjørnvold M, Sætre E, Johannessen SI, et al. A retrospective review of changes and challenges in the use of antiseizure medicines in Dravet syndrome in Norway. Epilepsia Open. 2020;5(3):432–441. 10.1002/EPI4.12413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mills JKA, Lewis TG, Mughal K, Ali I, Ugur A, Whitehouse WP. Retention rate of clobazam, topiramate and lamotrigine in children with intractable epilepsies at 1 year. Seizure. 2011;20(5):402–405. 10.1016/J.SEIZURE.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gonzalez‐Giraldo E, Baner N, Nutt A, Kossoff E, Kessler S. Clobazam retention rate in pediatric epilepsy (P1.5‐031). Neurology. 2019;92(15 Supplement). https://n.neurology.org/content/92/15_Supplement/P1.5‐031 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Villanueva V, García‐Ron A, Smeyers P, Arias E, Soto V, García‐Peñas JJ, et al. Outcomes from a Spanish expanded access program on cannabidiol treatment in pediatric and adult patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;137(Pt A):108958. 10.1016/J.YEBEH.2022.108958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kozak S, Russ W, Wieser HG. An audit of the use of vigabatrin in the treatment of medically refractory epilepsy at a presurgical unit. J Epilepsy. 1998;11(6):290–295. 10.1016/S0896-6974(98)00033-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Willems LM, Bertsche A, Bösebeck F, et al. Efficacy, retention, and tolerability of brivaracetam in patients with epileptic encephalopathies: a multicenter cohort study from Germany. Front Neurol. 2018;9(JUL):569. 10.3389/FNEUR.2018.00569/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nickels K, Kossoff EH, Eschbach K, Joshi C. Epilepsy with myoclonic‐atonic seizures (Doose syndrome): clarification of diagnosis and treatment options through a large retrospective multicenter cohort. Epilepsia. 2021;62(1):120–127. 10.1111/EPI.16752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Merdariu D, Delanoë C, Mahfoufi N, Bellavoine V, Auvin S. Malignant migrating partial seizures of infancy controlled by stiripentol and clonazepam. Brain Dev. 2013;35(2):177–180. 10.1016/J.BRAINDEV.2012.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nickels KC, Wirrell EC. Stiripentol in the management of epilepsy. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):405–416. 10.1007/S40263-017-0432-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brigo F, Igwe SC, Bragazzi NL. Stiripentol add‐on therapy for focal refractory epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(5):CD009887. 10.1002/14651858.CD009887.PUB4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Perez J, Chiron C, Musial C, Rey E, Blehaut H, d'Athis P, et al. Stiripentol: efficacy and tolerability in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1999;40(11):1618–1626. 10.1111/J.1528-1157.1999.TB02048.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chiron C, Tonnelier S, Rey E, Brunet ML, Tran A, d'Athis P, et al. Stiripentol in childhood partial epilepsy: randomized placebo‐controlled trial with enrichment and withdrawal design. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(6):496–502. 10.1177/08830738060210062101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rascol O, Squalli A, Montastruc JL, Garat A, Houin G, Lachau S, et al. A pilot study of stiripentol, a new anticonvulsant drug, in complex partial seizures uncontrolled by carbamazepine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1989;12(2):119–123. 10.1097/00002826-198904000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Djuric M, Kravljanac R, Kovacevic G, Martic J. The efficacy of bromides, stiripentol and levetiracetam in two patients with malignant migrating partial seizures in infancy. Epileptic Disord. 2011;13(1):22–26. 10.1684/EPD.2011.0402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The treatment of super‐refractory status epilepticus: a critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 10):2802–2818. 10.1093/BRAIN/AWR215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Strzelczyk A, Schubert‐Bast S. A practical guide to the treatment of Dravet syndrome with anti‐seizure medication. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(3):217–237. 10.1007/S40263-022-00898-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uchida Y, Terada K, Madokoro Y, Fujioka T, Mizuno M, Toyoda T, et al. Stiripentol for the treatment of super‐refractory status epilepticus with cross‐sensitivity. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;137(4):432–437. 10.1111/ANE.12888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Giraud C, Treluyer JM, Rey E, Chiron C, Vincent J, Pons G, et al. In vitro and in vivo inhibitory effect of stiripentol on clobazam metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(4):608–611. 10.1124/DMD.105.007237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mott DD, Grosenbaugh DK, Fisher JL. Polytherapy with stiripentol: consider more than just metabolic interactions. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;29(3):585. 10.1016/J.YEBEH.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Table S2.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessible to other researchers through a reasonable request.