Summary

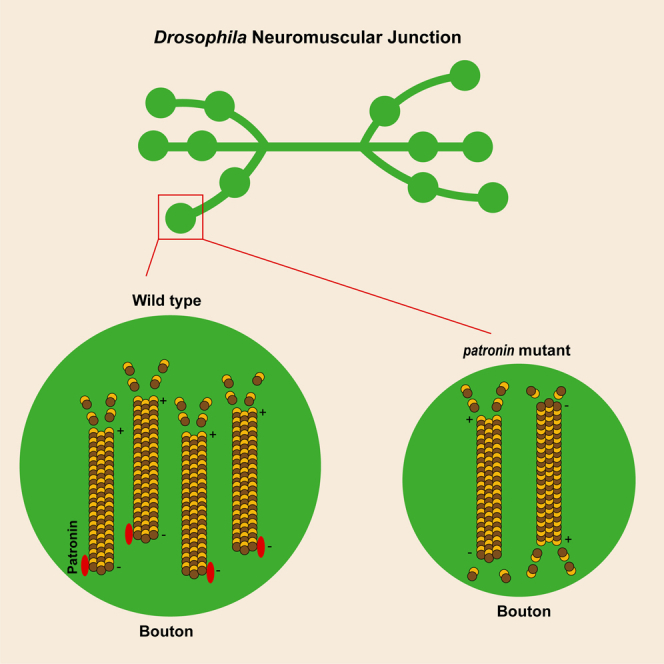

Synapses are fundamental components of the animal nervous system. Synaptic cytoskeleton is essential for maintaining proper neuronal development and wiring. Perturbations in neuronal microtubules (MTs) are correlated with numerous neuropsychiatric disorders. Despite discovering multiple synaptic MT regulators, the importance of MT stability, and particularly the polarity of MT in synaptic function, is still under investigation. Here, we identify Patronin, an MT minus-end-binding protein, for its essential role in presynaptic regulation of MT organization and neuromuscular junction (NMJ) development. Analyses indicate that Patronin regulates synaptic development independent of Klp10A. Subsequent research elucidates that it is short stop (Shot), a member of the Spectraplakin family of large cytoskeletal linker molecules, works synergistically with Patronin to govern NMJ development. We further raise the possibility that normal synaptic MT polarity contributes to proper NMJ morphology. Overall, this study demonstrates an unprecedented role of Patronin, and a potential involvement of MT polarity in synaptic development.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Neuroscience, Developmental neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Presynaptic Patronin functions in the development of the Drosophila NMJ

-

•

The CKK and CH domains are involved in the Patronin-mediated NMJ development

-

•

Patronin controls the bouton size in conjunction with Shot

-

•

Patronin regulates NMJ development by stabilizing microtubules

Biological sciences; Neuroscience; Developmental neuroscience

Introduction

Synapse is the functional unit of the nervous system and forms the basis of the neural circuits that underlie the near-universal behaviors and cognitions of animals. Chemical synapses are specialized asymmetric junctions consisting of presynaptic and postsynaptic compartments, and synaptogenesis is an intricate process that leads to the precise alignment of pre- and postsynaptic specializations.1,2,3 It also involves heterogeneous cellular and subcellular events with the regulations of divergence of signaling networks.4,5,6 Upon establishment, the synapse maintains neurotransmission by controlling the organization and fusion of synaptic vesicles. Understanding the underlying basis of synaptic development and function is essential for demonstrating paramount neuronal activities such as learning and memory and, consequently, a broad spectrum of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders.7 The Drosophila melanogaster neuromuscular junction (NMJ) has been recognized as an appealing model system to unravel the mechanisms underlying synaptic development and function, which shares striking similarities with the glutamatergic synapses of the mammalian brain.8,9 Of note, previous research in invertebrate organisms, for instance, D. melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, has partially shed light on the molecular underpinnings of synaptic development and function.10,11 The nervous systems of these organisms are relatively simple, with fewer neurons, glial cells, and connections contrasted to those of vertebrates.12 They are also feasible with the divergence of genetic manipulations. Importantly, numerous genes related to neuronal development and function are evolutionarily conserved between Drosophila and mammals.

It is nonnegligible that the regulation of the synaptic cytoskeleton is fundamental to proper neuronal development and wiring.13,14 Microtubules (MTs) organize a filamentous cytoskeletal network that serves as scaffolding for a variety of biological processes including cell division, growth and motility, mitotic spindle formation, cargo transport, and the maintenance of cellular shape.15,16,17,18,19 Importantly, MT abnormalities have profound effects on cognitive and other neurological functions and are associated with neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases.13,20,21,22 A growing body of research has elucidated that cytoskeletal stability and dynamics are required for the maintenance, development, plasticity, and functioning of the synapse.16,23,24 Strikingly, MTs exhibit an intriguing characteristic recognized as “dynamic instability”. Plus ends exhibit rapid growth and shrinkage phases, whereas the growth rate of minus ends is two to three times slower than plus ends.25

Previous study reported that Nezha, which can bind to the minus ends of MTs in mammalian cells.26 Subsequently, associated proteins, CAMSAP1, CAMSAP2, and CAMSAP3 have been identified, of which CAMSAP3 is identical to Nezha.27,28,29,30 CAMSAP3 distributes in the apical region of epidermal cell, where it is responsible for establishing the apical-basal array of MTs.27,31 Moreover, a pioneering study in Drosophila has demonstrated that patronin, also known as ssp4, is involved in the regulation of mitotic spindle assembly in S2 cells.32 A single patronin and ptrn-1 are encoded in Drosophila and C. elegans, respectively, that share homology with mammalian CAMSAP3.33,34,35 Previously, investigations have uncovered that the Patronin family belongs to the conserved MT minus-end-binding proteins and prevents the minus ends of MTs from depolymerization by kinesin-13.36,37,38 Patronin/CAMSAP/PTRN-1 consists of a calponin homology (CH) domain at its amino-terminus, three predicted coiled-coil (CC) domains at its central region, and a CAMSAP/KIAA1078/KIA1543 (CKK) domain at its carboxyl-terminus. Noteworthily, the CKK domain has been shown to be localized coincident with MTs, thus may represent a core domain that evolved in the regulation of MTs stability.33 Intriguingly, further works have illustrated that Patronin mediates the orientation of MT arrays in the dendrite, providing a potential mechanism for regulating neuronal remodeling.39,40

In a candidate-based RNA interference (RNAi) screen for synaptic development and function, we identify a previously uncharacterized role of Patronin in the synapse. In the present study, we demonstrate that the MT organization and terminal bouton size are significantly diminished after presynaptic Patronin is ablated in motor neurons. Furthermore, we present a possible indication that MT polarity may be involved in the development of the synapse. Moreover, the Spectraplakin family of large cytoskeletal linker molecules, short stop (Shot), works in conjunction with Patronin to sustain appropriate NMJ morphology. Collectively, our results illuminate, for the first time, the involvement of Patronin in modulating presynaptic MT organization and supporting the normal development of synapses.

Results

Patronin is required for proper NMJ morphology

Synaptic growth is essential for the development and plasticity of neural wiring. The larval neuromuscular system of Drosophila is relatively not complicated, consisting of only 32 motor neurons in each abdominal hemisegment, and has been extensively studied.41 During development, the motor neuron axons of Drosophila build connections with target muscles, forming terminal synaptic boutons. Subsequently, boutons are constantly thriving for sustaining synaptic strength and efficiency during the growth.9,42 Invariably, bouton size, number, and NMJ branch number are utilized for evaluating the status of synaptic growth and development. The abnormalities of synaptic bouton size and number are indicative of neurodevelopmental deficits that are usually delineated in Drosophila models of neurodevelopmental disorders.43,44,45

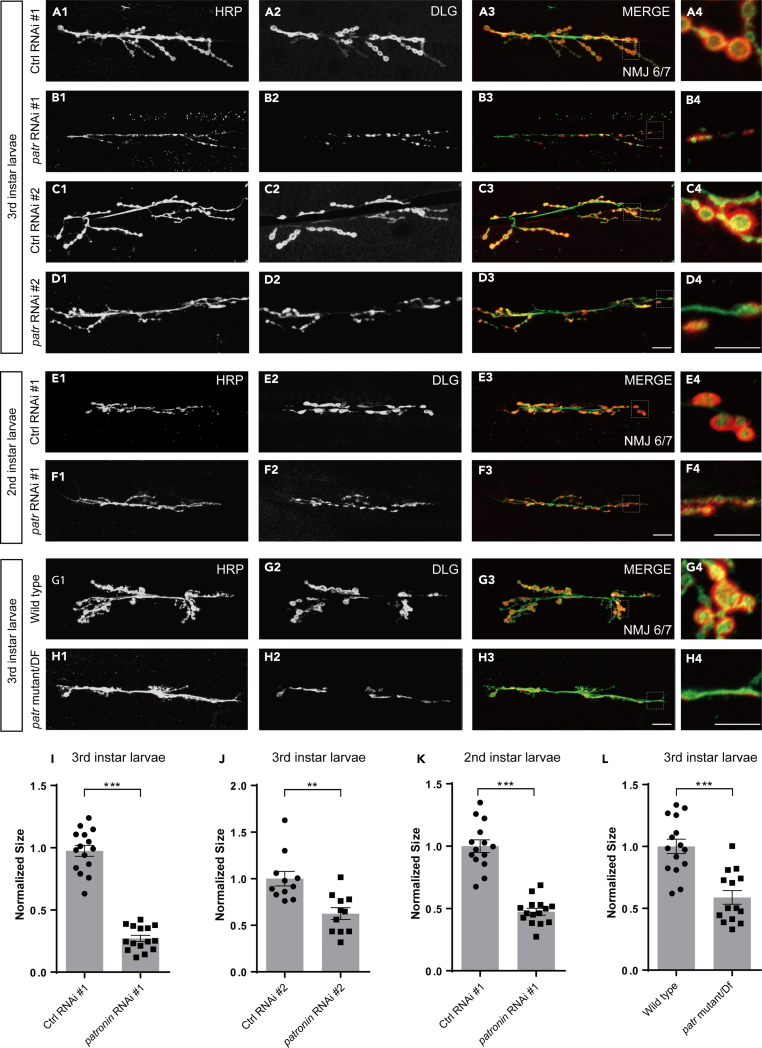

To further gain insight into the molecular basis of controlling synaptic growth and development, we performed a candidate-based RNAi screen by co-expressing OK6-Gal4, a motor neuron-specific driver, and UAS-Dcr2 to enhance RNAi efficacy for examining synaptic morphology defects at the Drosophila NMJ. NMJ morphology is visualized by immunostaining for extensively utilized presynaptic horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and postsynaptic Discs-large (Dlg) markers.24,46,47 In this screen, we isolated Patronin, which is required for maintaining the proper bouton size. Knockdown of Patronin, via two independent RNAi transgenes (#1 BL36659 and #2 V108927), led to prominent synaptic growth defects with significantly reduced synaptic bouton size in NMJ 6/7 at the third (3rd) instar larvae stage, although the V108927 was less effective in knocking down patronin than BL36659. In contrast, the neurons expressing the control RNAi line have been shown with the normal synaptic bouton size at the same time point (Figures 1A1–1D4, 1I, and 1J). We next asked whether Patronin is earlier demand for synaptic development. Therefore, we analyzed the NMJ morphology at the second (2nd) instar larvae stage and found that knockdown of Patronin caused an identical NMJ phenotype with the 3rd instar larvae stage (Figures 1E1–1F4 and 1K). To further verify the requirement of Patronin for synaptic development, we next generated mutant neurons using the hypomorphic allele patroninEY05252 trans to the overlapping deficiency (DF). Consistently, in contrast to no bouton size defect in the control (Figures 1G1–G4 and 1L), we found a similar small-volume bouton phenotype in mutant clones (Figures 1H1–H4 and 1L). Moreover, we also scored the bouton and neuronal branch number, two pivotal indicators to recapitulate the overall NMJ structure. Our study revealed a slight reduction in bouton numbers following inhibition of Patronin function through RNAi and mutant methods (Figures S1A–S1C). Furthermore, there was a mild reduction in branch number observed with the compromised function of Patronin in patronin RNAi #1 and hypomorphic allele mutant. Conversely, no significant changes were identified in patronin RNAi #2 (Figures S1D–S1F). It may be attributed to varied RNAi effectiveness. To test this possibility, we performed a real-time PCR experiment to investigate the efficiency of knockdown in these lines. Our data suggest that the VDRC line is slightly less effective than the BSC line, although this is not a significant difference (Figure S1G). Thus, in the subsequent assays, we primarily focus on the bouton size to assess the synaptic development phenotypes. Additionally, a similar phenotype in terms of bouton size was investigated in larval synapses innervating muscle 4 (Figures S2A1–S2B4 and S2C). Taken together, the bouton growth deficiency examined in NMJ expressing patronin RNAi at different developmental stages and mutant clones collectively corroborate that Patronin is indeed crucial for sustaining NMJ growth and development in Drosophila.

Figure 1.

Patronin is essential for bouton size

(A1–D4) Confocal projections showing representative images of NMJs at muscle 6/7 from the 3rd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of control RNAi #1 (A1–A3), patronin RNAi #1 (B1–B3), control RNAi #2 (C1–C3), and patronin RNAi #2 (D1–D3). (A4, B4, C4, D4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing. Control and patronin RNAi #1 are BDSC lines; control and patronin RNAi #2 are VDRC lines.

(E1–F4) Representative confocal images of NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 2nd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of control RNAi #1 (E1–E3) and patronin RNAi #1 (F1–F3). (E4, F4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(G1–H4) Representative confocal images of NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of wild-type (G1–G3) and patronin mutant (H1–H3). (G4, H4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(I and J) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the denoted genotypes from the 3rd larvae, showing the declined bouton size after Patronin knockdown.

(K) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the denoted genotypes from the wandering 2nd larvae, showing the declined bouton size after Patronin knockdown.

(L) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the denoted genotypes from the wandering 3rd larvae, showing the declined bouton size after Patronin knockout.

In I, J, K and L, data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t test was applied to determine statistical significance. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar in (A1–A3, B1–B3, C1–C3, D1–D3, E1–E3, F1–F3, G1–G3, and H1–H3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, F4, G4, and H4): 10 μm. See also Figures S1 and S2.

Patronin presynaptically promotes synaptic growth at NMJ

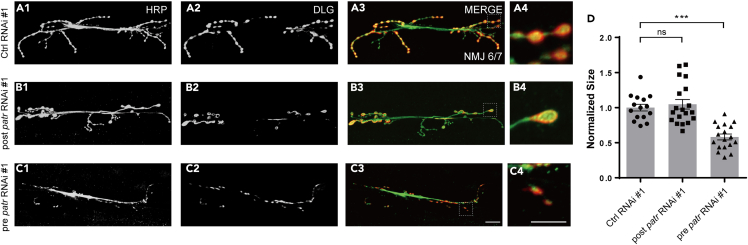

The chemical synapse is characterized by a structural asymmetry between the pre- and postsynaptic apparatuses.48 Our investigation aimed to determine the synaptic region that Patronin regulates for the morphology of larval NMJs. Given that Patronin is an MT minus-end-binding protein, it should be ubiquitously co-localized with MTs at both the pre- and postsynaptic compartments. To clarify whether the developmental deficit of NMJ in patronin mutant is due to the loss of Patronin at pre- and/or postsynapse of NMJs, we subsequently carried out experiments by expressing RNAi transgene specifically in the motor neuron and muscle using OK6-Gal4 and C57-Gal4 drivers, respectively. Our data demonstrated that knockdown of Patronin in the postsynaptic muscle did not significantly impact the bouton size of NMJ6/7 compared to the control (Figures 2A1–2B4 and 2D). In comparison to the wild-type neuron, the size of boutons was substantially reduced following a presynaptic knockdown of Patronin (Figure 2 A1-A4, C1-C4, D). Thus, these findings indicate that Patronin is specifically required at the presynapse for proper NMJ morphology.

Figure 2.

Patronin is presynaptically required for bouton size

(A1–C4) Confocal images of NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green), and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of control RNAi #1 (A1–A3), postsynaptic patronin RNAi #1 (B1–B3), and presynaptic patronin RNAi #1 (C1–C3). (A4, B4, and C4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(D) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the indicated genotypes, showing the neuronal but not muscle-specific knockdown of Patronin resulted in a significant decreased bouton size on muscle 6/7 of the wandering 3rd larvae.

In (D), data are mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance. ns, not significant; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar in (A1–A3, B1–B3, and C1–C3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, and C4): 10 μm.

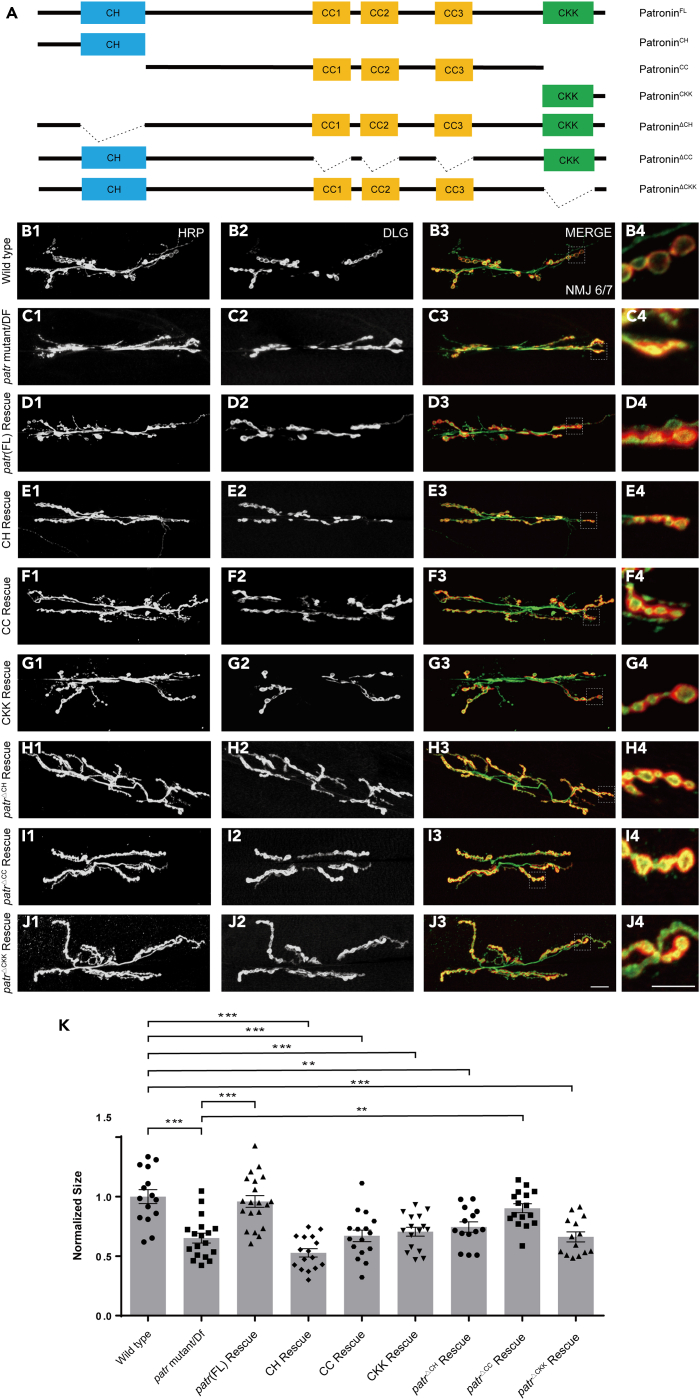

The CH and CKK domains of patronin are important for NMJ morphology

Previous analyses of Patronin have uncovered that it consists of a CH domain at its amino-terminus, three CC domains at its central region, and an MT conjoint CKK domain at its carboxyl-terminus.33,40 To systematically gain insight into the functional domain of Patronin that is required for its role in synaptic growth, we generated a set of domains transgenes, including Patronin-CH, Patronin-CC, Patronin-CKK, and the full-length of Patronin (Figure 3A). To exclude the gain-of-function effects of these Patronin variants, we firstly drove the expression of these truncated transgenes in motor neuron via Ok6-Gal4 and our data suggested that expression of all these UAS transgenes did not lead to any perturbation to NMJ development at the 3rd instar larvae stage contrasted to UAS control (Figures S3A1–S2E4 and S2F). These data demonstrate that ectopic expression of these individual domains does not impair the endogenous function of Patronin on synaptic development.

Figure 3.

The CH and CKK domain of Patronin are involved in sustaining bouton size

(A) A schematic representation of full-length and truncated Patronin variants.

(B1–J4) NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of wild-type (B1–B3), patronin mutant (C1–C3), Patronin full-length rescue (D1–D3), Patronin-CH domain rescue (E1–E3), Patronin-CC domain rescue (F1–F3), Patronin-CKK domain rescue (G1-G3), PatroninΔCH domain rescue (H1–H3), PatroninΔCC domain rescue (I1–I3), and PatroninΔCKK domain rescue (J1–J3). (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, F4, G4, H4, I4, and J4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing. All the rescue experiments were carried out in the background of the patronin mutant.

(K) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the denoted genotypes, showing overexpression of full-length of Patronin and PatroninΔCC could rescue the bouton size defect in patronin mutant, whereas overexpression of Patronin CC, CKK, CH domains, PatroninΔCH, and PatroninΔCKK could not alleviate the bouton size defect in patronin mutant.

In (K), data are mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar in (A1–A3, B1–B3, C1–C3, D1–D3, E1–E3, F1–F3, G1–G3, H1–H3, I1–I3, and J1–J3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, F4, G4, H4, I4, and J4): 10 μm. See also Figure S3.

To comprehensively understand the roles of these variants in NMJ development, we next sought to determine their ability to rescue the NMJ developmental phenotype by expressing these Patronin truncates in patronin mutant neurons. Unfortunately, overexpression of Patronin-CH, Patronin-CC, and Patronin-CKK consistently failed to ameliorate the NMJ phenotype in the patronin mutant (Figures 3B1–3C4, 3E1–3G4, and 3K). Nevertheless, driving the expression of the full-length of Patronin in motor neuron was able to almost totally restore the NMJ deficits (Figures 3B1–3D4 and 3K), indicating that the NMJ morphology defect is a consequence of the lack of Patronin function. The single of Patronin truncated domain seems not necessary for the normal synaptic development. It is feasible that the ineffective rescue is due to functional defects in Patronin resulting from omissions of other protein regions in these variations. Noteworthily, it has been well documented that CKK domain of Patronin directly attaches to MTs and involves in the regulation of MT activity.33 It seems plausible that the expression of CKK domain alone was not efficient to restore the NMJ phenotype in the patronin mutant, might be ascribed to the over-small size of protein domain. To further testify the potential role of CKK domain in NMJ development, we subsequently constructed PatroninΔCKK, PatroninΔCH, and PatroninΔCC, full-length of Patronin without CKK, CH, and CC domains, respectively. Our data suggest that overexpression of Patronin with deleted CKK and CH domains is ineffective in restoring the NMJ phenotype in patronin mutant (Figures 3B1–3C4, 3H1–3H4, 3J1–3J4, and 3K). However, Patronin lacking the CC domain demonstrates the ability to ameliorate the NMJ defect in mutant (Figures 3B1–3C4, 3I1–3I4, and 3K). These results indicate the crucial functional roles of CKK and CH regions and dispensable function of the CC domain in Patronin-mediated NMJ development.

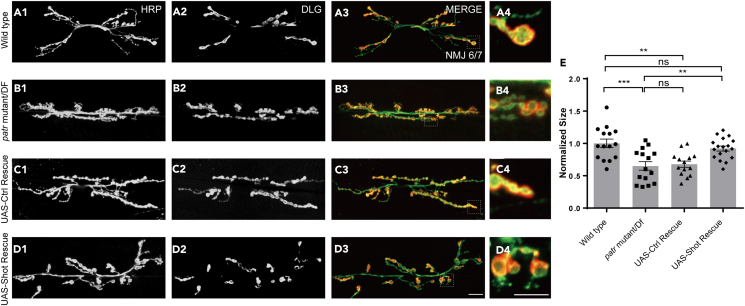

Patronin and shot jointly sustain normal bouton size

To gain insight into the molecular basis of Patronin in the regulation of NMJ development, we attempted to examine the regulatory efficiency of Patronin associated proteins on NMJ morphology. Klp10A is well known as an MT-depolymerizing kinesin-13 of Drosophila melanogaster that depolymerizes cytoplasmic MTs.49,50 Patronin acts as an antagonist by specifically stabilizing MT minus ends against Klp10A-driven depolymerization to regulate MT dynamics and polarity.36,38,40 Additionally, Shot, the single Spectraplakin in Drosophila, serves as a huge cytoskeletal linker protein and contains an actin binding domain at its N-terminal and two C-terminal domains that bind MT.51,52,53 It has been reported that Shot is required for the polarized organization of MTs in the oocyte.53 Further studies have characterized the reciprocal functional links between Shot and Patronin in the construction of non-centrosomal MT array for specifying the Anterior-Posterior Axis of Drosophila embryos.53,54 Moreover, a study has also implicated that Shot and Patronin polarize MT to direct membrane traffic and biogenesis of microvilli in epithelia.55 Firstly, to evaluate potential antagonism between Patronin and Klp10A during NMJ development, we thus attenuated Klp10A via RNAi in patronin mutant neurons and scrutinized NMJ morphology. Unfortunately, knockdown of Klp10A could not alleviate the bouton size phenotype in patronin mutant neurons (Figures S4A1–S4C4 and S4D). Afterward, we interrogated whether the NMJ developmental defect in patronin mutant neurons is caused by the compromised Shot. Thus, we knocked down Shot via OK6-Gal4, and found that undermined Shot resulted in a similar phenotype caused by inhibition of Patronin (Figures S5A1–S5B4 and S5C). To further characterize the interrelation of Shot and Patronin in synaptic development, we subsequently overexpressed Shot in patronin mutant neurons and examined NMJ morphology. Intriguingly, the induction of Shot at presynapse substantially resulted in a considerable recovery of the declined bouton size in patronin mutant neurons. In contrast, the overexpression of UAS-Control failed to alleviate the bouton size phenotype in patronin mutant (Figures 4A1–4D4 and 4E), implicating a potential relationship between Patronin and Shot in NMJ development.

Figure 4.

Shot overexpression ameliorates bouton size defect in patronin mutant

(A1–D4) Confocal images of NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of wild-type (A1–A3), patronin mutant (B1–B3), UAS-Control rescue (C1–C3), and UAS-Shot rescue (D1–D3). (A4, B4, C4, and D4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing. The patronin mutant background was used for all rescue experiments.

(E) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the indicated genotypes, showing overexpression of Shot could rescue the bouton morphology defect in patronin mutant.

In E, data are mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance. ns, not significant; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar in (A1–A3, B1–B3, C1–C3, and D1–D3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, C4, and D4): 10 μm. See also Figures S4 and S5.

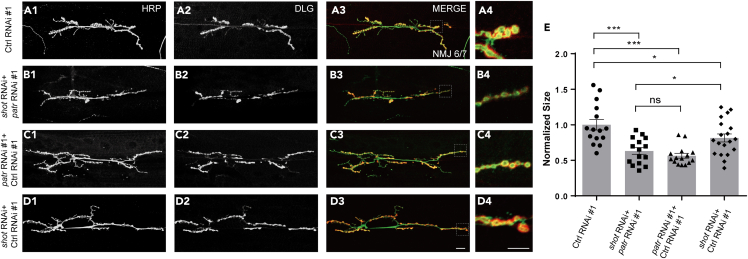

To further ascertain whether Patronin and Shot function in the same pathway or in two parallel pathways during NMJ development, we subsequently double knocked down patronin and shot and contrasted to their single RNAi via OK6-Gal4. We found that knock down patronin and shot individually lead to declined bouton size compared with control RNAi (Figures 5A1–5A4, 5C1–5D4, and 5E). Additionally, our findings suggested that RNAi knockdown of patronin plus the control RNAi caused a stronger bouton size defect than shot RNAi with control RNAi knockdown (Figures 5C1–5D4 and 5E). Whereas, no significant increase in NMJ defect was investigated in mutant motor neurons of the patronin and shot double RNAi constructs, contrasted to patronin RNAi with control RNAi knockdown (Figures 5B1–5C4 and 5E). Hence, these results, together with the rescue experiment, exhibiting that Patronin and Shot are synchronously function to govern NMJ development.

Figure 5.

Patronin and Shot synchronously regulate bouton size

(A1–D4) Representative NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of control RNAi #1 (A1–A3), patronin and shot double RNAi (B1–B3), patronin RNAi #1 plus control RNAi #1 (C1-C3), and shot RNAi plus control RNAi #1 (D1–D3). (A4, B4, C4, and D4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(E) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the denoted genotypes, showing patronin and shot double RNAi could not lead to further decline of bouton size when compared with patronin RNAi #1 plus control RNAi #1.

In (E), data are mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar in (A1-A3, B1-B3, C1-C3, and D1-D3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, C4, and D4): 10 μm.

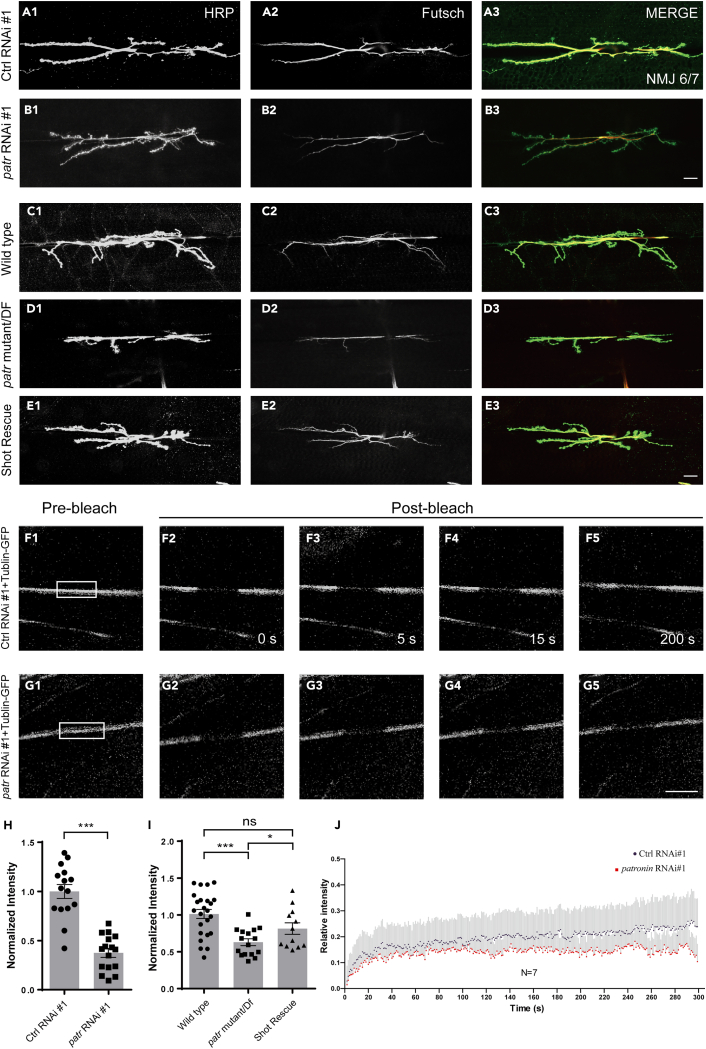

Patronin is essential for the normal level and dynamic organization of presynaptic MTs

Given that Patronin is well known for its MT minus-end protecting function, we then asked whether the attenuation of Patronin would undermine the organization of presynaptic MT. Previous studies have implicated Futsch, the MAP1B homolog, is against by the monoclonal antibody 22C10 that has been broadly recognized as a presynaptic MT marker to visualize neuronal morphology and axonal projections.16,56 To this end, we dove the expression of patronin RNAi specific in motor neuron via Ok6-Gal4 and examined the cytoskeletal structure through the immunostaining of Futsch. In line with our hypothesis, downregulation of Patronin at presynapse resulted in a striking decline in MT intensity, and the whole structure of MT in NMJ appeared constrictively (Figures 6B1–6B3 and 6H). Nevertheless, the neurons expressing the control RNAi displayed normal MT intensity and architecture at the same time point (Figures 6A1–6A3 and 6H). To further elucidate the role of Patronin in synaptic MT regulation, we next examined the level of Futsch in the patronin mutant and found the analogous MT phenotype (Figures 6C1–6D3 and 6I). Our previous results showed that Patronin collaborates with Shot to govern NMJ morphology, we thus suspected whether supplementation of Shot would ameliorate the MT deficiency in the patronin mutant. We subsequently overexpressed Shot, and found that induction of Shot was able to alleviate the attenuated MT intensity in the patronin mutant (Figures 6C1–6E3 and 6I). This is consistent with the results presented in bouton morphology, implicating the functional relevance of Patronin and Shot in both MT stability and NMJ development. To further characterize the requirement of Patronin on the presynaptic MT organization, we attempted to investigate the MT dynamics in the patronin mutant neurons. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) is one of the main techniques that has been broadly applied to discriminate protein dynamics in vivo and in vitro.57 To better characterize the requirement of Patronin in the organization of presynaptic MT, we dove the expression of tubulin-GFP at presynapse via OK6-Gal4 in patronin RNAi and Control RNAi, respectively. Compared to the control group, animals with patronin RNAi displayed a reduced tendency for tubulin dynamic recovery signal after photobleaching in the axons of motor neurons (Figures 6F1–6G5 and 6J). In summary, our findings demonstrate that Patronin modulates the overall level of MTs, and depletion of Patronin, to some extent, results in a decline in the dynamic organization of presynaptic MTs.

Figure 6.

Patronin is required for sustaining MT intensity and dynamic recovery in motor neuron

(A1–E3) Confocal images of NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and MT marker Futsch (Futsch, red). NMJ of control RNAi #1 (A1-A3), patronin RNAi #1 (B1-B3), wild-type (C1-C3), patronin mutant (D1-D3), and UAS-Shot rescue (E1-E3). The rescue experiment was performed on a patronin mutant background.

(F1–G5) The Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments showing the representative time-course images of tubulin-GFP fluorescence in control RNAi #1 and patronin RNAi #1 motor axons. The axons positioned between the ventral nerve cord (VNC) and NMJ, measuring approximately 30μm, were selected for our bleaching analysis. White boxes indicate photobleached regions.

(H) Quantification of normalized Futsch intensity of the indicated genotypes, showing patronin RNAi led to decreased of MT intensity when compared with control.

(I) Quantification of normalized Futsch intensity of the indicated genotypes, showing patronin mutant resulted in declined MT intensity and introduction of Shot could rescue the MT phenotype in patronin mutant.

(J) FRAP recovery curves show the relative GFP fluorescence intensities within the photobleached regions in control RNAi #1 (red, n = 7) and patronin RNAi #1 (blue, n = 7). s.e.m at each time point are shown in the curves.

In H and I, data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t test was applied to determine statistical significance for two groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance for more than two groups. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar: 20 μm (A1-E3); 20 μm (F1-G5). See also Figure S6.

Since it has been reported that Shot interacts with Patronin, and works as a medium between actin and MT,53 we then proceeded to discern its potential role in controlling F-actin in motor neurons. F-actin is usually visualized by using fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin.58 Our result showed a slight decrease in the phalloidin staining at NMJ of patronin RNAi contrasted to the wild-type control (Figures S6A1–S6B3 and S6C). This discovery implies that F-actin may play a part in the process of Patronin-mediated synaptic development. Thus, these data systematically elucidate that Patronin cooperates with Shot for proper presynaptic MT organization and NMJ development.

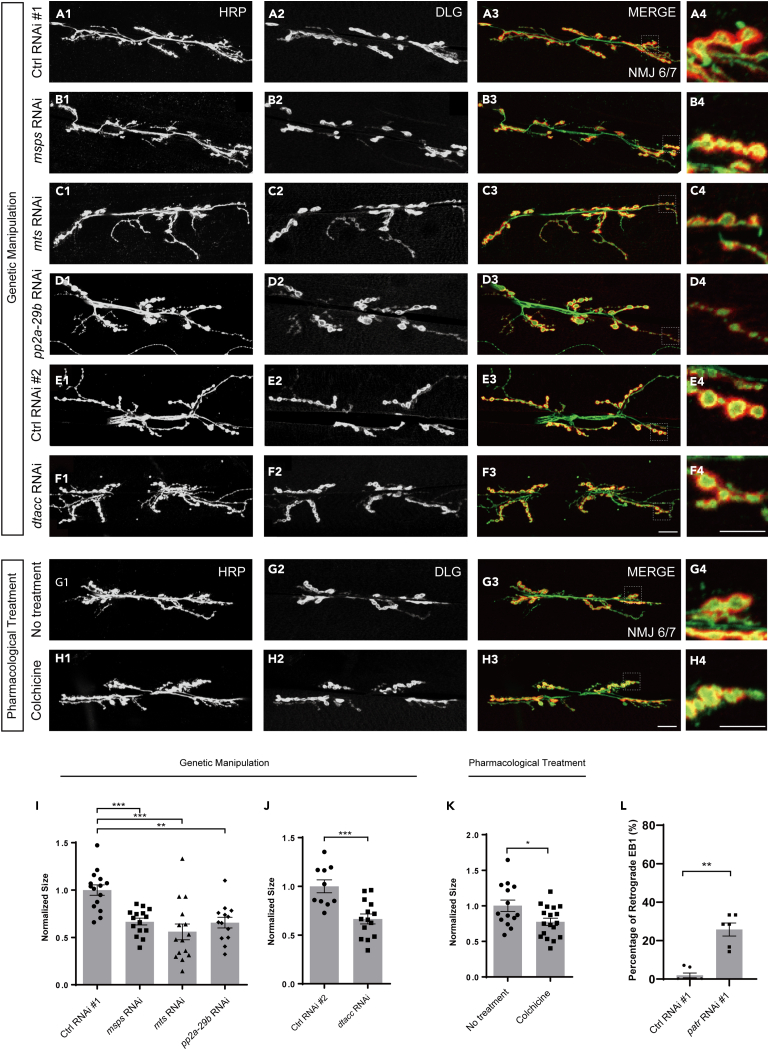

MTs polarity alterations potentially impair bouton size

MTs are polarized cytoskeletal filaments of cells, serving as tracks for intracellular transport and establishing a framework that orients organelles and other cellular constituents and modulates the architecture and mechanics of cells. The geometry, dynamic, and directionality of MT networks are primary determinants of cellular structure, polarity, and function.59,60 Patronin has been recently reported to govern dendritic MT polarity in class IV dendritic arborization sensory neurons (C4da) neurons.39,40 Based on this, we next interrogated whether the undermined morphology of NMJ is due to the altered polarity of MT. Previous studies have shown that Mini spindles (Msps), a conserved MT polymerase, associates with another MT-associated protein, TACC, to orient dendritic MT polarity in the Drosophila C4da neuron.61 Additionally, the catalytic (Microtubule star/Mts) and scaffolding (PP2A-29B) subunits of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) display an important role in modulating the orientation of MTs in the dendrites of the Drosophila C4da neuron.62 At subsequent, we knocked down these MT regulators in motor neuron by OK6-Gal4 and checked the NMJ morphology. Our results showed that interference of MT polarity via genetic attenuation of these MT regulators led to prominent NMJ defects (Figures 7A1–7F4, 7I, and 7J), indicating a possible regulatory function of MT polarity in NMJ development. To further determine the role of MT polarity in NMJ, we next attempted to alter the MT orientation via a pharmacological treatment approach. A well-characterized MT-destabilizing agent (MDA), namely Colchicine, has been reported to induce MT catastrophe at the plus ends63 and dendritic misaligned MT arrays.61 Thus, we fed the flies with standard food containing Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and Colchicine, respectively. Staining of NMJ in DMSO-fed fly showed normal bouton size, whereas Colchicine feeding led to significantly reduced bouton size, analogous to previous genetic manipulation of MT orientation-associated genes (Figures 7G1–7H4 and 7K). These findings raise the possibility that MT polarity is required for normal NMJ development.

Figure 7.

MT polarity is potentially important for bouton size

(A1–F4) NMJs on muscle 6/7 from the wandering 3rd larvae double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). NMJ of control RNAi #1 (A1-A3), msps RNAi (B1-B3), mts RNAi (C1-C3), pp2a-29b RNAi (D1-D3), control RNAi #2 (E1-E3), and dtacc RNAi (F1-F3). (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, and F4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing are shown at the left bottom corner.

(G1–H3) Confocal projections showing representative NMJ images of pharmacological treatment at muscle 6/7 from the 3rd larvae, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). DMSO control (F1-F3) and Colchicine (G1-G3). (G4, H4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(I and J) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the denoted genotypes, showing the declined bouton size after knockdown of MT polarity regulators in NMJ.

(K) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the indicated drug treatment, showing the declined bouton size via Colchicine treatment.

(L) Quantitative analyses of the percentages of retrograde EB1 in the axon of C4da neuron. The PPK-Gal4 (III) was used to drive the expression of UAS-EB1-GFP.

In I, J, K, and L, data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t test was applied to determine statistical significance for two groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance for more than two groups. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar in (A1-A3, B1-B3, C1-C3, D1-D3, E1-E3, F1-F3, G1-G3, and H1-H3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, F4, G4, and H4): 10 μm.

Several studies have observed that EB1-GFP marks the growing plus ends of MTs, and the direction of EB1-GFP movement is recognized as the MT plus end.64,65,66 It has been well documented in the Drosophila C4da neuron that more than 95% of EB1-GFP comets migrate face to the soma in dendrite. Nevertheless, nearly all of the EB1-GFP comets in axon move away from the soma, implicating a uniform minus-end-out MT polarity in dendrites and a plus-end-out axonal MT polarity.40,62 To better characterize the role of MT polarity during synaptic development, we intended to make use of EB1-GFP to precisely track the orientation of MT in the NMJ, whereas it remained ambiguous to depict the movement patterns of the EB1 comet via kymographs due to the relative deep position of the NMJ, even though we could faintly observe the reversed direction of EB1-GFP movement after knockdown of Patronin in our field of vision (Data not shown). We thus turned to analyses of MT polarity by EB1-GFP in the axon of a surface-located Drosophila C4da neuron, and our data suggested that EB1 comets predominantly moved away from the soma in the major axons of wild-type. Remarkably, some parts among EB1 comets moved toward the soma after blocking the function of Patronin in axons (Figure 7L). These data, together with NMJ phenotype in other MT orientation regulators and pharmacological treatment results, validate that the maintenance of normal synaptic development may involve the correct polarity of MTs.

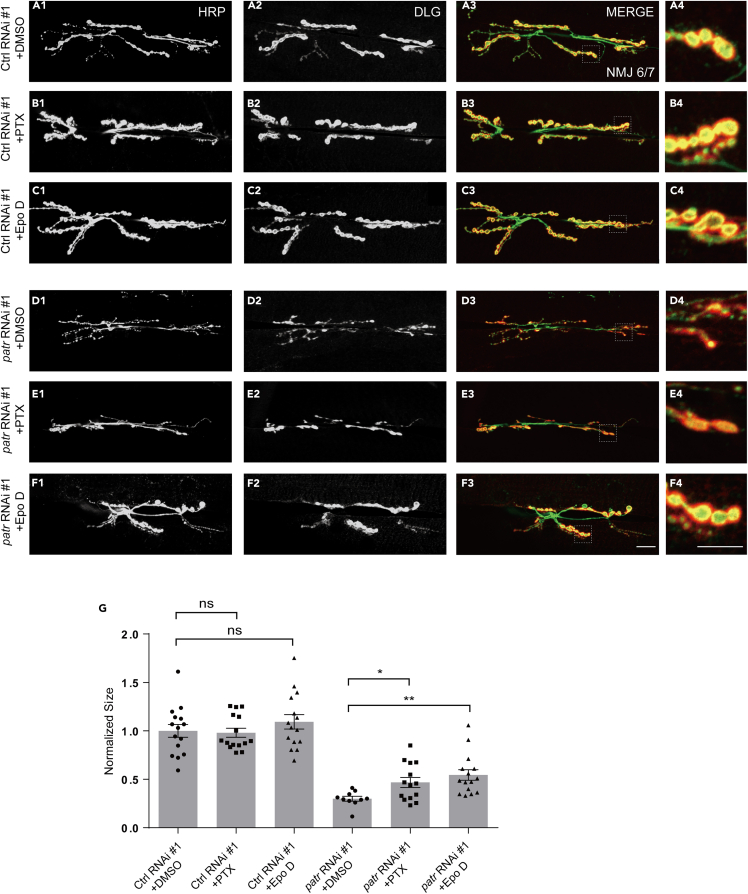

Patronin regulates bouton size via MT stability

To gain a deeper understanding of the role of MTs in Patronin-mediated synaptic development, we aim to investigate whether stabilizing MTs in the absence of Patronin can alleviate defects in synaptic development. Prior research has indicated that MTs can be stabilized by paclitaxel (PTX) and epothilone D (Epo D).67,68,69,70 Accordingly, we administered precise quantities of PTX and Epo D to the diet of wild-type and Patronin RNAi flies, respectively. Through our analysis of third-instar larvae using NMJ imaging, we have discovered that pharmacological treatment did not impact synaptic development in the wild-type flies (Figures 8A1–8C4 and 8G). Nevertheless, drug-stabilized MTs are capable of partially rescuing the synaptic developmental phenotype caused by the loss of Patronin (Figures 8D1–8F4 and 8G). This illustrates the role of Patronin in the promotion of normal synaptic development through the maintenance of MT stability.

Figure 8.

Facilitating the MT stability ameliorates bouton phenotype in Patronin downregulated NMJ

(A1–C3) Confocal projections showing representative NMJ images of pharmacological treatment at muscle 6/7 from the 3rd larvae in control RNAi #1, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). DMSO control (A1–A3), PTP (B1–B3), and Epo D (C1–C3). (A4, B4, and C4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(D1–F3) Confocal projections showing representative NMJ images of pharmacological treatment at muscle 6/7 from the 3rd larvae in patronin RNAi #1, double-stained with the presynaptic motoneuron membrane (Hrp, green) and postsynaptic marker Dlg (DLG, red). DMSO control (D1–D3), PTP (E1–E3), and Epo D (F1–F3). (D4, E4, and F4) The magnified boutons used for analyzing.

(G) Quantification of normalized bouton size of the indicated drug treatment, showing no bouton size alterations via PTP and Epo D treatment in control RNAi #1 and the increased bouton size via PTP and Epo D treatment in patronin RNAi #1.

In (G), data are mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was applied to determine statistical significance for more than two groups. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. The number of neurons (n) examined in each group is shown on the bars. Scale bar: in (A1–A3, B1–B3, C1–C3, D1–D3, E1–E3, and F1–F3): 20 μm; Scale bar in (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, and F4): 10 μm.

Discussion

MTs are broadly considered to play an important role in organizing a filamentous cytoskeletal network that acts as tracks for the transport of intracellular molecules and organelles.15,18 It is notable that an intriguing characteristic of MT has been well documented over the past decades as “dynamic instability”, rapid growth of plus ends, whereas the growth rate of minus ends is strikingly slower.25 Previous analyses have unraveled the prominent role of MT polarity in dendrite pruning.40,62 Nevertheless, it is not yet known whether MT polarity is also required for synapse development and function. Herein, we investigate the unknown role of a conserved MT minus-end-binding protein, Patronin, in the regulation of synaptic MT organization and terminal bouton size at Drosophila NMJ. Patronin was initially discovered for its pivotal function in mitotic spindle regulation in the Drosophila S2 cell.32 At subsequent, important prior studies established that Patronin discerns and protects the free minus ends of MT against kinesin 13-mediated MT depolymerization.36 In the mammalian neuron of hippocamp, CAMSAP2 anchors to the minus ends of MT and displays an indispensable function in axon specification and dendrite formation.71 The C. elegans ortholog, PTRN-1, has been suggested to control the distribution of synaptic vesicle, neurite architecture, and axon regeneration.34,35,72 However, to our knowledge, it remains ambiguous whether there is a crucial role of Drosophila Patronin in neuronal development involving synaptic growth. Previous studies have unambiguously ascertained that synaptic morphogenesis could be well defined at the phenomenological level by investigating Drosophila NMJ.45,73 In the present study, we raise a series of lines of in vivo evidence to determine that Patronin is an unreported regulator of synaptic development at the Drosophila NMJ, and Patronin governs synaptic development mainly via presynaptic apparatus. Firstly, our genetic assay with heterogeneous RNAi lines and mutants, as well as the rescue results, unambiguously corroborate that Patronin is cell-autonomously required for sustaining bouton morphology. Furthermore, we downregulated the expression of Patronin at pre- and postsynapse, respectively, and our data strongly show that presynaptic Patronin is required for the synaptic development of Drosophila NMJ. Therefore, it is inferred that Patronin plays a crucial role in maintaining the accurate synaptic terminal structure at the Drosophila NMJ. Significantly, our findings point to the critical functional role of the CKK and CH domains in Patronin-mediated development of the NMJ, as overexpression of Patronin lacking these domains is unable to rescue the NMJ phenotype in patronin mutant. Further research is necessary to determine whether the removal of these domains affects the overall structure of Patronin. This will help to reinforce the crucial functions of the CKK and CH domains in synaptic development and advance our knowledge of the underlying mechanism via binding proteins associated with these domains.

How does Patronin maintain synaptic morphology in Drosophila NMJ? It has been extensively reported that synapse is the fundamental functional units of the nervous system, and the well-established synaptic cytoskeleton in neuron is prerequisite to guarantee appropriate neuronal development and wiring.13,14 Perturbation of MT in neuron would result in numerous neuropsychiatric disorders.21,22 Patronin is well known for preventing MT depolymerization by counteracting the Klp10A function at the minus end of MT. However, in this study, we find that attenuation of Klp10A in patronin mutant neurons has no rescue efficacy for the NMJ morphology phenotype. Interestingly, the introduction of Shot, substantially ameliorates the NMJ defects in the patronin mutant. Further investigations into downstream targets are warranted to provide insight into the detailed mechanisms that control synaptic morphology in Drosophila NMJ. It has been widely approved that MT cytoskeleton in the cell supports the normal cellular architecture as well as the intracellular transport of proteins and organelles. In mammalian neurons, MTs in axon are polarized with accordant plus-end-out orientation, whereas MTs in dendrite own mixed orientations with both plus-end-out and plus-end-in.74,75 Nevertheless, dendritic MTs are arranged in a primary orientation of plus-end-in of Drosophila and C. elegans neurons.76,77 Intriguingly, our recent observations, together with those of others, have elucidated a high correlation between MT orientation and dendrite pruning.40,61,62,78 Patronin is a minus-end-binding protein and associated with divergence of MT features, we thus propose that MT structure, dynamics, and polarity should be the underlying mechanisms for the regulation of terminal NMJ morphology by Patronin. In the present study, we raise heterogeneous lines of in vivo evidence to ascertain that loss function of presynaptic Patronin attenuates MT dynamics and interferes MT polarity. Nevertheless, we monitor EB1 movement in the axons of surface-located somatosensory neuron to reflex the MT polarity in NMJ due to the relative deep position of motor neuron. Therefore, further technical improvement will be needed to determine whether Patronin directly involves the regulation of MT polarity in motor neurons. In a prior study, it was discovered that the transmembrane proteins Neurexin and Frizzled uphold the levels of atypical kinesin VAB-8/KIF26 at synaptic MT minus ends, promoting the formation of synapses in C. elegans. Loss of VAB-8/KIF26 leads to the incorrect localization of minus-end protein, PTRN-1, the Drosophila ortholog of Patronin on synaptic MTs, ultimately prompting excessive retrograde transportation and hence the loss of synapse.79 Based on this, it is hypothesized that the absence of Patronin and Shot could amplify the retrograde transfer of synaptic supplies by disrupting the polarity of MTs, consequently affecting the development of NMJ. Further research is necessary to explore the fundamental regulatory mechanism of Patronin and Shot in orienting axonal MT, as well as the potential impact of this interaction on the retrograde transport of synaptic material at Drosophila NMJ. Given the fact that the phalloidin signal is also diminished after downregulating Patronin at NMJ, although with a slight degree, it raises the possibility that F-actin might also be involved in the regulation of synaptic development by Patronin. Therefore, additional analysis of F-actin is needed to replenish the regulatory mechanism of Patronin in NMJ development. Altogether, this study illustrates a novel paradigm that a conserved MT minus-end-binding protein, Patronin, plays a crucial role in synaptic development at Drosophila NMJ. Moreover, our data suggest that Patronin is essential for controlling the organization of presynaptic MT and thereby sustaining normal NMJ morphology. Notably, our pharmacological and genetic approaches to alter MT polarity demonstrate a potential significance of MT polarity in synaptic development. Nevertheless, up to this point, the practical relevance linking MT orientation and synaptic development is still not very clear. Considering this, our study will open new avenues for further exploration of the roles of MT polarity in synaptic development and function.

Limitations of the study

Further investigations are required to identify the binding proteins with CH and CKK domains to further elucidate the underlying regulatory mechanism of Patronin in synapse development. To ascertain whether Patronin is directly involved in the regulation of MT polarity in motor neurons, more technological advancements are required. The basic regulatory mechanism by which Patronin and Shot orient axonal MT, as well as any possible consequences of this relationship for the retrograde transport of synaptic material at Drosophila NMJ, require further investigation. To supplement the regulating mechanism of Patronin in synapse development, more research on F-actin is required. The significance of the link between MT orientation and synaptic development requires further investigation.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Dlg | DSHB | Cat# 4F3; RRID: AB_528203 |

| HRP | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 323-005-021; RRID: AB_2314648 |

| Futsch | DSHB | Cat# 22C10; RRID: AB_528403 |

| Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin | Molecular Probes | Cat# T7471 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit | Invitrogen | Cat# A-21206; RRID: AB_2535792 |

| Alexa Fluor 555 anti-mouse | Invitrogen | Cat# A-31570; RRID: AB_2536180 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Colchicine | Aladdin | C106740 |

| Paclitaxel | Macklin | CAS:33069-62-4 |

| Epothilone D | Macklin | CAS:189453-10-9 |

| DMSO | Sigma-Aldrich | D1435 |

| halocarbon oil | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#H8898 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| OK6-Gal4 | BDSC | BL64199 |

| PPK-Gal4 (III) | A gift from Dr Yan Zhu (Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) | N.A |

| UAS-EB1-GFP | A gift from Dr Xin Liang (Tsinghua University) | N.A |

| control RNAi #1 | BDSC | BL35785; mCherry.RNAi, VALIUM20 |

| patronin RNAi #1 | BDSC | BL36659 |

| w1118 | BDSC | BL5905 |

| patroninEY05252 | BDSC | BL16647 |

| DF (Patronin) | BDSC | BL24379 |

| C57-Gal4 | BDSC | BL32556 |

| UAS-control | BDSC | BL35788 |

| shot RNAi | BDSC | BL41858; TRiP.GL01286, VALIUM22 |

| UAS-Shot | BDSC | BL29043 |

| klp10a RNAi | BDSC | BL33963; TRiP.HMS00920, VALIUM20 |

| mts RNAi | BDSC | BL27723; TRiP.JF02805, VALIUM10 |

| pp2a-29b RNAi | BDSC | BL29384; TRiP.JF03316, VALIUM10 |

| msps RNAi | BDSC | BL31138; TRiP.JF01613, VALIUM1 |

| tubulin-GFP | A gift from Dr Xin Liang (Tsinghua University) | N.A |

| patronin RNAi #2 | VDRC | V108927 |

| dtacc RNAi | VDRC | V101439 |

| control RNAi #2 | VDRC | V51446 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software | RRID:SCR_002798 |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://ImageJ.net/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and regents can be directed to the lead contact, Menglong Rui (ruimenglong@seu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

Transgenic fly lines generated in this study: For domains analysis experiments, the full-length of UAS-Patronin-HA, UAS-Patronin-CH, UAS-Patronin-CC, UAS-Patronin-CKK, UAS-PatroninΔCH, UAS-PatroninΔCC, and UAS-PatroninΔCKK constructs were made by cloning the full-length and truncated cDNA into the transformation vector pUAST-attB. Transgenic fly lines were generated by standard germline transformation. The attB/P system was used for integration and they were all integrated into the same genomic location (attp2, chromosome III) to normalise expression. cDNA of Patronin was obtained from reverse transcription of genomic mRNA. Fly head mRNA was extracted using TRIzol (Life Technologies), and reverse transcribed using cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Applied Biosystems). The variants of Patronin were generated by either PCR or site mutagenesis using Patronin CDS as a template. The transgenic lines were established by the UniHuaii Inc.

Data and code availability

-

•

No new code was used in these studies.

-

•

No large dataset was generated in these studies.

-

•

Any additional information will be available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Drosophila melanogaster

The male and female Drosophila melanogaster were maintained at 25°C on standard fly food. The transgenic flies of UAS-Patronin-HA (full-length), UAS-Patronin-CH, UAS-Patronin-CC, UAS-Patronin-CKK, UAS-PatroninΔCH, UAS-PatroninΔCC, and UAS-PatroninΔCKK used in this study were generated in our laboratory. The fly of PPK-Gal4 (III) was obtained from Dr Yan Zhu (Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and the flies of UAS-EB1-GFP and tubulin-GFP were obtained from Dr Xin Liang (Tsinghua University). Other stocks were mainly obtained from Bloomington Stock Center or VDRC. A full list of the fly lines used in this study can be found in the key resources table. The male and female 2nd and wandering 3rd instar larvae of distinct genotypes were used for experiments. The DMSO (Beyotime, ST1276), 20 μg/ml Colchicine (Aladdin, C106740), 10 μM l PTX (Macklin, 33069-62-4), and 10μM Epo D (Macklin, 189453-10-9) were included in fly food to determine the influence of MT stability and polarity on NMJ development. The sex of Drosophila melanogaster has no influence on the results of the study.

Method details

Immunostaining and image analysis

For NMJ staining of the wandering 3rd instar larvae of distinct genotypes, larvae were dissected in pre-cooling Ca2+-free HL3.1 saline (70 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2 ,10 mM NaHCO3 ,5 mM trehalose, 115 mM sucrose, and 5mM Hepes, pH 7.2) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 30 min. At subsequent, the fillets were stained with antibodies after dissection and fixation. The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: mouse anti-DLG (DSHB, 1:50), rabbit anti-HRP (DSHB, 1:500), mouse anti-Futsch (DSHB, 1:50), Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes, 1:10) and Alexa Fluor 488-, Alexa Fluor 555-, or Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:500). For the intensity analysis, the entire Futsch signal region in the NMJ was measured using Image J.

Analysis of synaptic boutons of NMJs

The second-instar larvae and wandering third-instar larvae were dissected, and the body wall muscles were immunostained using anti-HRP and anti-DLG antibodies. Serial confocal images of the NMJs of muscle 4 and 6/7 in abdominal segments A2 and A3 were obtained. Bouton size was determined by calculating the average size of the four boutons situated at the end of the NMJ. Image J and GraphPad Prism 9 were utilized for the analysis. The quantitative measurement of bouton number was based on identifying the rounded profiles of type Ib boutons at muscles 6/7, labeled with HRP and DLG staining. Further, the quantification of NMJ branch number was based on the numbers of primary and secondary neuronal branches at muscles 6/7.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

FRAP experiments were performed on motor neurons expressing tubulin-GFP. The axons positioned between the ventral nerve cord (VNC) and NMJ, measuring approximately 30μm, were selected for our bleaching analysis. Zeiss LSM 900 confocal microscope was utilized to scan the interested region of axon with 100% laser power of the 488 nm for 2-3s. The laser power was then reduced to 1% for monitoring the recovery of the fluorescence signal over time. Recovery after photobleaching was recorded for 5 minutes at 1 frame every 0.93 s. Motor axon moving out of focus during image acquisition were ignored. Fluorescence recovery curves and statistical tests were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.

Drug treatment

Embryos were collected and raised on standard food. The larvae were then transferred to the food containing DMSO (Beyotime, ST1276) and 20μg/ml Colchicine (Aladdin, C106740) according to previous formula.61 10 μM l PTX (Macklin, 33069-62-4), and 10μM Epo D (Macklin, 189453-10-9). The 3rd wandering instar larvae were dissected after 1 day of drug feeding and utilized for confocal imaging.

Live imaging of EB1

Larvae at 96 h AEL were immersed with a drop of halocarbon oil (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#H8898) and mounted to slides for confocal imaging. Confocal time-lapse imaging for EB1-GFP movement in the axons of C4da neuron was recorded with Zeiss LSM 900 using 60× oil lens with 3× zoom. Ninety frames were acquired at 2-s intervals with 3 Z-steps.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For pairwise comparison, two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to determine statistical significance for two groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was applied to determine significance when multiple groups were present. Error bars in all graphs represent s.e.m. Statistical significance was defined as ∗∗∗∗P<0.0001, ∗∗∗P<0.001, ∗∗P<0.01, ∗P<0.05, and ns, not significant. The number of neurons (n) in each group is shown on the bars.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32100784), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20221458), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2242022R10092). We thank the Bloomington Stock Center (BSC), Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC) and Tsinghua RNAi Stock Center for generously providing fly stocks. We thank other members of the Dr Xie and Dr Wang laboratory for stimulating helpful discussion. We thank Dr Fengwei Yu for helpful assistance. We thank Dr Xin Liang (Tsinghua University) for providing tubulin-GFP stock. We thank Mrs. Lei He for technical assistance on the LSM 900 confocal microscope.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.R.; Methodology: Z.G. and M.R.; Software: Z.G. and M.R.; Validation: Z.G., E.H., W.W., W.X., T.Z., and M.R.; Formal analysis: Z.G., E.H., W.W., L.X., W.X., T.Z., and M.R.; Investigation: Z.G., E.H., W.W., L.X., and M.R.; Resources: M.R.; Data curation: Z.G. and M.R.; Writing–original draft: M.R.; Writing–review and editing: M.R.; Visualization: M.R.; Supervision: M.R.; Project administration: M.R.; Funding acquisition: M.R.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 18, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.108944.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Jessell T.M., Kandel E.R. Synaptic transmission: a bidirectional and self-modifiable form of cell-cell communication. Cell. 1993;72:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chia P.H., Li P., Shen K. Cell biology in neuroscience: cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying presynapse formation. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:11–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo Z. Synapse formation and remodeling. Sci. China Life Sci. 2010;53:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-0069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang X., Sando R., Südhof T.C. Multiple signaling pathways are essential for synapse formation induced by synaptic adhesion molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000173118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulkowski M.J., Han T.H., Ott C., Wang Q., Verheyen E.M., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Serpe M. A Novel, Noncanonical BMP Pathway Modulates Synapse Maturation at the Drosophila Neuromuscular Junction. PLoS Genet. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teo S., Salinas P.C. Wnt-Frizzled Signaling Regulates Activity-Mediated Synapse Formation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021;14 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.683035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batool S., Raza H., Zaidi J., Riaz S., Hasan S., Syed N.I. Synapse formation: from cellular and molecular mechanisms to neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurophysiol. 2019;121:1381–1397. doi: 10.1152/jn.00833.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin W., McArdle J.J. The NMJ as a model synapse: New perspectives on synapse formation, function, and maintenance Introduction. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;740 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou V.T., Johnson S.A., Van Vactor D. Synapse development and maturation at the drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neural Dev. 2020;15:11. doi: 10.1186/s13064-020-00147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith L.C., Budnik V. Plasticity and second messengers during synapse development. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2006;75:237–265. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendi A., Kurashina M., Mizumoto K. Intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms of synapse formation and specificity in C. elegans. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019;76:2719–2738. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ardeshiri R., Rezai P. Lab-on-chips for manipulation of small-scale organisms to facilitate imaging of neurons and organs. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2016;2016:5749–5752. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2016.7592033. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goellner B., Aberle H. The synaptic cytoskeleton in development and disease. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012;72:111–125. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz-Cañada C., Budnik V. Synaptic cytoskeleton at the neuromuscular junction. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2006;75:217–236. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parato J., Bartolini F. The microtubule cytoskeleton at the synapse. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;753 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roos J., Hummel T., Ng N., Klämbt C., Davis G.W. Drosophila Futsch regulates synaptic microtubule organization and is necessary for synaptic growth. Neuron. 2000;26:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forth S., Kapoor T.M. The mechanics of microtubule networks in cell division. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:1525–1531. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oelz D.B., Del Castillo U., Gelfand V.I., Mogilner A. Microtubule Dynamics, Kinesin-1 Sliding, and Dynein Action Drive Growth of Cell Processes. Biophys. J. 2018;115:1614–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kline-Smith S.L., Walczak C.E. Mitotic spindle assembly and chromosome segregation: refocusing on microtubule dynamics. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodaleo F.J., Gonzalez-Billault C. The Presynaptic Microtubule Cytoskeleton in Physiological and Pathological Conditions: Lessons from Drosophila Fragile X Syndrome and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016;9:60. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasser M., Tiber J., Lowery L.A. The Role of the Microtubule Cytoskeleton in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018;12:165. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matamoros A.J., Baas P.W. Microtubules in health and degenerative disease of the nervous system. Brain Res. Bull. 2016;126:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao C.X., Xiong Y., Xiong Z., Wang Q., Zhang Y.Q., Jin S. Microtubule-severing protein Katanin regulates neuromuscular junction development and dendritic elaboration in Drosophila. Development. 2014;141:1064–1074. doi: 10.1242/dev.097774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Migh E., Gotz T., Foldi I., Szikora S., Gombos R., Darula Z., Medzihradszky K.F., Maleth J., Hegyi P., Sigrist S., Mihaly J. Microtubule organization in presynaptic boutons relies on the formin DAAM. Development. 2018;145 doi: 10.1242/dev.158519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchison T., Kirschner M. Dynamic Instability of Microtubule Growth. Nature. 1984;312:237–242. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng W., Mushika Y., Ichii T., Takeichi M. Anchorage of microtubule minus ends to adherens junctions regulates epithelial cell-cell contacts. Cell. 2008;135:948–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka N., Meng W., Nagae S., Takeichi M. Nezha/CAMSAP3 and CAMSAP2 cooperate in epithelial-specific organization of noncentrosomal microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:20029–20034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218017109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pongrakhananon V., Saito H., Hiver S., Abe T., Shioi G., Meng W., Takeichi M. CAMSAP3 maintains neuronal polarity through regulation of microtubule stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:9750–9755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803875115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imasaki T., Kikkawa S., Niwa S., Saijo-Hamano Y., Shigematsu H., Aoyama K., Mitsuoka K., Shimizu T., Aoki M., Sakamoto A., et al. CAMSAP2 organizes a gamma-tubulin-independent microtubule nucleation centre through phase separation. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.77365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva V.C., Cassimeris L. CAMSAPs add to the growing microtubule minus-end story. Dev. Cell. 2014;28:221–222. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toya M., Kobayashi S., Kawasaki M., Shioi G., Kaneko M., Ishiuchi T., Misaki K., Meng W., Takeichi M. CAMSAP3 orients the apical-to-basal polarity of microtubule arrays in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:332–337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520638113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goshima G., Wollman R., Goodwin S.S., Zhang N., Scholey J.M., Vale R.D., Stuurman N. Genes required for mitotic spindle assembly in Drosophila S2 cells. Science. 2007;316:417–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1141314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baines A.J., Bignone P.A., King M.D.A., Maggs A.M., Bennett P.M., Pinder J.C., Phillips G.W. The CKK Domain (DUF1781) Binds Microtubules and Defines the CAMSAP/ssp4 Family of Animal Proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:2005–2014. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcette J.D., Chen J.J., Nonet M.L. The Caenorhabditis elegans microtubule minus-end binding homolog PTRN-1 stabilizes synapses and neurites. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.01637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson C.E., Spilker K.A., Cueva J.G., Perrino J., Goodman M.B., Shen K. PTRN-1, a microtubule minus end-binding CAMSAP homolog, promotes microtubule function in Caenorhabditis elegans neurons. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.01498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwin S.S., Vale R.D. Patronin regulates the microtubule network by protecting microtubule minus ends. Cell. 2010;143:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hendershott M.C., Vale R.D. Regulation of microtubule minus-end dynamics by CAMSAPs and Patronin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404133111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H., Brust-Mascher I., Civelekoglu-Scholey G., Scholey J.M. Patronin mediates a switch from kinesin-13-dependent poleward flux to anaphase B spindle elongation. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:35–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng C., Thyagarajan P., Shorey M., Seebold D.Y., Weiner A.T., Albertson R.M., Rao K.S., Sagasti A., Goetschius D.J., Rolls M.M. Patronin-mediated minus end growth is required for dendritic microtubule polarity. J. Cell Biol. 2019;218:2309–2328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201810155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y., Rui M., Tang Q., Bu S., Yu F. Patronin governs minus-end-out orientation of dendritic microtubules to promote dendrite pruning in Drosophila. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.39964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menon K.P., Carrillo R.A., Zinn K. Development and plasticity of the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2013;2:647–670. doi: 10.1002/wdev.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keshishian H., Broadie K., Chiba A., Bate M. The drosophila neuromuscular junction: a model system for studying synaptic development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1996;19:545–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jepson J.E.C., Shahidullah M., Liu D., le Marchand S.J., Liu S., Wu M.N., Levitan I.B., Dalva M.B., Koh K. Regulation of synaptic development and function by the Drosophila PDZ protein Dyschronic. Development. 2014;141:4548–4557. doi: 10.1242/dev.109538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knodel M.M., Geiger R., Ge L., Bucher D., Grillo A., Wittum G., Schuster C.M., Queisser G. Synaptic bouton properties are tuned to best fit the prevailing firing pattern. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2014;8:101. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2014.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou V.T., Johnson S., Long J., Vounatsos M., Van Vactor D. dTACC restricts bouton addition and regulates microtubule organization at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Cytoskeleton. 2020;77:4–15. doi: 10.1002/cm.21578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lobb-Rabe M., DeLong K., Salazar R.J., Zhang R., Wang Y., Carrillo R.A. Dpr10 and Nocte are required for Drosophila motor axon pathfinding. Neural Dev. 2022;17:10. doi: 10.1186/s13064-022-00165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rui M., Qian J., Liu L., Cai Y., Lv H., Han J., Jia Z., Xie W. The neuronal protein Neurexin directly interacts with the Scribble-Pix complex to stimulate F-actin assembly for synaptic vesicle clustering. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:14334–14348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.794040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson A.H.D., Schürmann F.W. Synaptic structure, distribution, and circuitry in the central nervous system of the locust and related insects. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002;56:210–226. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delgehyr N., Rangone H., Fu J., Mao G., Tom B., Riparbelli M.G., Callaini G., Glover D.M. Klp10A, a microtubule-depolymerizing kinesin-13, cooperates with CP110 to control Drosophila centriole length. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Persico V., Callaini G., Riparbelli M.G. The Microtubule-Depolymerizing Kinesin-13 Klp10A Is Enriched in the Transition Zone of the Ciliary Structures of Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:173. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takács Z., Jankovics F., Vilmos P., Lénárt P., Röper K., Erdélyi M. The spectraplakin Short stop is an essential microtubule regulator involved in epithelial closure in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 2017;130:712–724. doi: 10.1242/jcs.193003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ricolo D., Araujo S.J. Coordinated crosstalk between microtubules and actin by a spectraplakin regulates lumen formation and branching. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.61111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nashchekin D., Fernandes A.R., St Johnston D. Patronin/Shot Cortical Foci Assemble the Noncentrosomal Microtubule Array that Specifies the Drosophila Anterior-Posterior Axis. Dev. Cell. 2016;38:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takeichi M., Toya M. Patronin Takes a Shot at Polarity. Dev. Cell. 2016;38:12–13. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khanal I., Elbediwy A., Diaz de la Loza M.D.C., Fletcher G.C., Thompson B.J. Shot and Patronin polarise microtubules to direct membrane traffic and biogenesis of microvilli in epithelia. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:2651–2659. doi: 10.1242/jcs.189076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hummel T., Krukkert K., Roos J., Davis G., Klämbt C. Drosophila Futsch/22C10 is a MAP1B-like protein required for dendritic and axonal development. Neuron. 2000;26:357–370. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan Y., Broadie K. In vivo assay of presynaptic microtubule cytoskeleton dynamics in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;162:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xing G., Li M., Sun Y., Rui M., Zhuang Y., Lv H., Han J., Jia Z., Xie W. Neurexin-Neuroligin 1 regulates synaptic morphology and functions via the WAVE regulatory complex in Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.30457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akhmanova A., Kapitein L.C. Mechanisms of microtubule organization in differentiated animal cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:541–558. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00473-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meiring J.C.M., Shneyer B.I., Akhmanova A. Generation and regulation of microtubule network asymmetry to drive cell polarity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020;62:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang Q., Rui M., Bu S., Wang Y., Chew L.Y., Yu F. A microtubule polymerase is required for microtubule orientation and dendrite pruning in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2020;39 doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rui M., Ng K.S., Tang Q., Bu S., Yu F. Protein phosphatase PP2A regulates microtubule orientation and dendrite pruning in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2020;21 doi: 10.15252/embr.201948843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohan R., Katrukha E.A., Doodhi H., Smal I., Meijering E., Kapitein L.C., Steinmetz M.O., Akhmanova A. End-binding proteins sensitize microtubules to the action of microtubule-targeting agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:8900–8905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300395110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rolls M.M., Satoh D., Clyne P.J., Henner A.L., Uemura T., Doe C.Q. Polarity and intracellular compartmentalization of Drosophila neurons. Neural Dev. 2007;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stepanova T., Slemmer J., Hoogenraad C.C., Lansbergen G., Dortland B., De Zeeuw C.I., Grosveld F., van Cappellen G., Akhmanova A., Galjart N. Visualization of microtubule growth in cultured neurons via the use of EB3-GFP (end-binding protein 3-green fluorescent protein) J. Neurosci. 2003;23:2655–2664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02655.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaughan K.T. TIP maker and TIP marker; EB1 as a master controller of microtubule plus ends. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:197–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang C.P.H., Horwitz S.B. Taxol: The First Microtubule Stabilizing Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1733. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brizuela M., Blizzard C.A., Chuckowree J.A., Dawkins E., Gasperini R.J., Young K.M., Dickson T.C. The microtubule-stabilizing drug Epothilone D increases axonal sprouting following transection injury. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;66:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brizuela M., Chuckowree J.A., Blizzard C.A., Young K.M., Dickson T.C. The Microtubule-Stabilizing Drug Epothilone D Increases Axonal Sprouting Response in an in Vitro Model of Transection Injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2015;32:A51. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao Y.N., Zheng L.L., Wang D., Liang X.X., Gao F., Zhou X.L. Recent advances in microtubule-stabilizing agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;143:806–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yau K.W., van Beuningen S.F.B., Cunha-Ferreira I., Cloin B.M.C., van Battum E.Y., Will L., Schätzle P., Tas R.P., van Krugten J., Katrukha E.A., et al. Microtubule minus-end binding protein CAMSAP2 controls axon specification and dendrite development. Neuron. 2014;82:1058–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chuang M., Goncharov A., Wang S., Oegema K., Jin Y., Chisholm A.D. The Microtubule Minus-End-Binding Protein Patronin/PTRN-1 Is Required for Axon Regeneration in C. elegans. Cell Rep. 2014;9:874–883. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhat S.A., Yousuf A., Mushtaq Z., Kumar V., Qurashi A. Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats Impair Synaptic Growth and Synaptic Transmission at Drosophila larval Neuromuscular Junction. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021;30:1677–1692. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baas P.W., Lin S. Hooks and Comets: The Story of Microtubule Polarity Orientation in the Neuron. Dev. Neurobiol. 2011;71:403–418. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yau K.W., Schätzle P., Tortosa E., Pagès S., Holtmaat A., Kapitein L.C., Hoogenraad C.C. Dendrites In Vitro and In Vivo Contain Microtubules of Opposite Polarity and Axon Formation Correlates with Uniform Plus-End-Out Microtubule Orientation. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:1071–1085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2430-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stone M.C., Roegiers F., Rolls M.M. Microtubules Have Opposite Orientation in Axons and Dendrites of Drosophila Neurons. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4122–4129. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goodwin P.R., Sasaki J.M., Juo P. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5 Regulates the Polarized Trafficking of Neuropeptide-Containing Dense-Core Vesicles in Caenorhabditis elegans Motor Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:8158–8172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0251-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Herzmann S., Gotzelmann I., Reekers L.F., Rumpf S. Spatial regulation of microtubule disruption during dendrite pruning in Drosophila. Development. 2018;145 doi: 10.1242/dev.156950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Balseiro-Gómez S., Park J., Yue Y., Ding C., Shao L., Ҫetinkaya S., Kuzoian C., Hammarlund M., Verhey K.J., Yogev S. Neurexin and frizzled intercept axonal transport at microtubule minus ends to control synapse formation. Dev. Cell. 2022;57:1802–1816.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2022.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

No new code was used in these studies.

-

•

No large dataset was generated in these studies.

-

•

Any additional information will be available from the lead contact upon request.