Abstract

Objective:

To determine the degree to which anger arousal and anger regulation (expression, inhibition) in the daily lives of people with chronic pain were related to spouse support, criticism, and hostility as perceived by patients and as reported by spouses.

Method:

Married couples (, 1 spouse with chronic low back pain) completed electronic daily diaries, with assessments 5 times/day for 14 days. On these diaries, patients completed items on their own anger arousal, anger expression, and inhibition, and on perceived spouse support, criticism, and hostility. Spouses reported on their responses toward patients and their negative affect. Hierarchical linear modeling tested concurrent and lagged relationships.

Results:

Patient-reported increases in anger arousal and anger expression were predominantly related to concurrent decreases in patient-perceived and spouse-reported spouse support, concurrent increases in patient-perceived and spouse-reported spouse criticism and hostility, and increases in spouse-reported negative affect. Relationships for anger expression remained significant with anger arousal controlled. These effects were especially strong for male patients. Spouses reported greater negative affect when patients were present than when they were not.

Conclusions:

Social support may facilitate adjustment to chronic pain, with declining support and overt criticism and hostility possibly adversely impacting pain and function. Results suggest that patient anger arousal and expression may be related to a negative interpersonal environment for married couples coping with chronic low back pain.

Keywords: patient anger arousal, anger expression/inhibition, spouse responses, daily diary

Anger-related factors are significantly associated with pain intensity, mood, and function among people with chronic low back pain, with greater anger consistently related to poorer adjustment (Janssen, Spinhoven, & Brosschot, 2001; Kerns, Rosenberg, & Jacob, 1994; Nicholson, Gramling, Ong, & Buenevar, 2003; Wade, Price, Hamer, Schwartz, & Hart, 1990). Although the magnitude and frequency of anger arousal influence pain and function, findings from questionnaire (Burns, Johnson, Mahoney, Devine, & Pawl, 1996), laboratory-based (Bruehl, Burns, Chung, Ward, & Johnson, 2002; Burns, Quartana, & Bruehl, 2008), and daily diary studies (Bruehl, Liu, Burns, Chont, & Jamison, 2012; Burns et al., 2015; van Middendorp et al., 2010) suggest that the way patients regulate anger (expression, inhibition) may have detrimental effects on pain and function beyond those due simply to being angry. Both patient anger arousal and anger regulation directly amplify pain intensity and negative mood as well as reduce function. These kinds of effects may be termed “intrapersonal pathways” by which one’s anger and anger regulation affect adjustment to one’s own chronic pain.

Other evidence suggests that anger arousal and anger regulation among people with chronic pain may adversely affect relationships with friends and family (Burns et al., 1996; Druley, Stephens, Martire, Ennis, & Wojno, 2003; Johansen & Cano, 2007; Schwartz, Slater, Birchler, & Atkinson, 1991). Among married couples in general, angry partners, especially when anger is expressed, are viewed negatively by their spouses and receive low social support from them (Yoo, Clark, Lemay, Salovey, & Monin, 2011). For patients with chronic illness (Lane & Hobfoll, 1992) or chronic pain (Druley et al., 2003; Johansen & Cano, 2007; Schwartz et al., 1991), results indicate that patient anger adversely affects the mood of spouses. For chronic pain sufferers high in trait anger expressiveness, high pain severity and activity interference was partly explained by high levels of patient-perceived critical spouse responses (Burns et al., 1996). Findings suggest that angry patients in pain may disaffect spouses, especially when anger is expressed toward the spouse, thus increasing negative spouse responses and reducing supportive responses (Julkunen, Gustavsson-Lilius, & Hietanen, 2009). Insofar as social support is an important element in successful adaptation to chronic illness (Thoits, 1986; Wortman & Conway, 1985), patient adjustment and well-being may suffer due to estranged and openly hostile friends and family. Indeed, patient anger may also result in elevated spouse negative mood (Schwartz et al., 1991), leading perhaps to spouses avoiding the patient, or, alternatively, to spouses being conditioned to criticize the patient.

Conceptually, we can borrow from Coyne’s (Coyne & DeLongis, 1986) interpersonal model of depression and Smith’s transactional model of hostility (Smith, 1992) to formulate hypotheses. Analogous to depressed people invoking rejection from and worsened mood in potential supporters, anger aroused in people with chronic pain may inspire negative responses from potential supporters. From a transactional view, repeated patient anger arousal could create a chronic critical or hostile interpersonal environment, wherein, far from receiving needed support and help, the patient is faced with outright hostility and criticism. The harm wrought by patient anger and anger regulation tactics on the mood and behavior of potential supporters may be termed “interpersonal pathways.”

In the present study, we used electronic diary methods to extend the work cited above and to evaluate the degree to which anger arousal and behavioral anger regulation—expression and inhibition—in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) were related to both patient perceptions of spouse support, criticism, and hostility, and to spouse reports of their negative affect and their supportive, critical, and hostile responses toward patients. Spouse reports were used to generate cross-spouse effects that were not influenced by the common method variance characteristic of relying solely on patient ratings of their own behavior and perceptions of spouse responses (e.g., Smith et al., 2008). Patients with CLBP and their spouses completed electronic diary entries 5 times/day for 14 days using Personal Data Assistants (PDAs). The current study represents, to our knowledge, the first diary study to simultaneously examine both patient and spouse reports of the interpersonal effects of patient anger in the context of chronic pain.

Previous analyses of these data tested intrapersonal pathways (Burns et al., 2015), and showed that (a) patient-reported increases in state anger arousal were related to their reports of concurrent increases in pain intensity and pain interference and to spouse reports of patient pain intensity and pain behavior; (b) patient-reported increases in state anger arousal (e.g., at 9 a.m.) were related to lagged increases in spouse reports of patient pain intensity and pain behaviors (e.g., at 12 p.m.); (c) patient-reported increases in behavioral anger expression (e.g., at 9 a.m.) were related to lagged increases in patient-reported pain intensity and interference and decreases in function (e.g., at 12 p.m.); (d) most of these relationships remained significant with state anger arousal controlled; and (e) patient-reported increases in behavioral anger inhibition were related to concurrent increases in pain interference and decreases in function, which also remained significant with state anger arousal controlled.

In the present study, we tested interpersonal pathways. If patient anger arousal and behavioral anger regulation, as these occur in everyday life, are related to a critical and hostile interpersonal environment characterized by unsupportive, alienated, and unhappy spouses, then (a) concurrent analyses should reveal that patient anger arousal, behavioral anger expression, and/or inhibition are related to changes in spouse support, criticism, and hostility both as perceived by the patient and as reported by the spouse; (b) concurrent analyses should also reveal that patient anger arousal, behavioral anger expression, and/or inhibition are related to increases in spouse negative affect; (c) lagged analyses would further show that initial patient anger arousal, anger expression, and/or inhibition predict later spouse responses (i.e., patient anger at 9 a.m. → spouse criticism at 12 p.m.), and feelings of negative affect; (d) spouse negative affect should be greater when the patient is present than when he or she is not. Such results would support “interpersonal pathways” based on the interpersonal (Coyne & DeLongis, 1986) and transactional models (Smith, 1992). Furthermore, examining whether patient anger and anger regulation are related adversely to spouse responses toward the patient will shed light on the less studied social component of a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain, and perhaps reveal the importance of interpersonal functioning for optimal adjustment to chronic pain.

In addition, a handful of studies has documented sex differences in the degree to which anger regulation affects the physical health of patients (intrapersonal pathway; Doster, Purdum, Martin, Goven, & Moorefield, 2009; Hogan & Linden, 2005; Suarez, 2006) and their interpersonal function (Julkunen et al., 2009). Indeed, Julkunen and colleagues (2009) found that among female cancer patients, anger inhibition was related negatively to male spouse support, but male patients’ anger inhibition was not related significantly to female spouse support. Based on these findings, we examined whether the degree to which patient anger arousal and anger regulation were related to spouse criticism, hostility, and support depended on the sex of the patient.

Method

Participants

Exactly 121 married couples were recruited through referrals from staff at the pain clinics of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois, Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, Memorial Hospital in South Bend, Indiana, and through advertisements in local newspapers and flyers provided at various health care agencies. Each participant received $150. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Rush University Medical Center, Duke University Medical Center, and University of Notre Dame.

Patient inclusion criteria were (a) pain of the lower back stemming from degenerative disk disease, spinal stenosis, or disk herniation (radiculopathy subcategory), or muscular or ligamentous strain (chronic myofascial pain subcategory); (b) pain duration of at least 6 months, with an average intensity of at least 3/10 (with 0 being “no pain” and 10 “the worst pain possible”); and (c) age between 18 and 70 years. The inclusion criterion for spouses was age between 18 and 70 years.

Exclusion criteria for both patients and spouses were (a) current alcohol or substance abuse problems or else meeting criteria for alcohol or substance abuse or dependence within the past 12 months; (b) current or past psychotic or bipolar disorders; (c) inability to understand English well enough to complete questionnaires; (d) acute suicidality; and (e) meeting criteria for obsessive–compulsive disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder within the past 2 years. A further exclusion criterion for patients was if their pain complaint was due to malignant conditions (e.g., cancer, rheumatoid arthritis), migraine or tension headache, fibromyalgia, or complex regional pain syndrome. A further exclusion criterion for spouses was if they reported currently suffering from a condition that caused recurrent episodes of acute pain (i.e., migraine headaches) or reported a history of chronic pain within the past 12 months.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed by a detailed medical and psychosocial history, including administration of the Mood Disorder, Psychotic Screening, and Substance Use Disorders modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, Non-Patient Edition (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996).

Of the 121 couples recruited, 8 couples declined to participate in the diary portion of the study, 3 couples withdrew before completing 14 days of data collection, 4 couples lost data due to PDA malfunctions, and 1 couple’s data were lost due to failure to upload it from the PDA at an appropriate time. Thus, the final sample was 105 couples. Women patients comprised 48.6% of the sample (). Demographic characteristics of couples not included in this investigation did not differ significantly from those who were included. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Patient | Spouse | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 48.6% (n = 51) | 51.4% (n = 54) |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 46.30 (12.1) | 45.96 (13.2) |

| Hispanic | 4.8% (n = 5) | 5.7% (n = 6) |

| African American | 15.2% (n = 16) | 18.1% (n = 19) |

| White | 80.0% (n = 84) | 76.2% (n = 80) |

| Employed | 40.0% (n = 42) | 63.8% (n = 67) |

| Disability insurance | 34.3% (n = 36) | 13.3% (n = 14) |

| Length of marriage (M, SD) | 14.30 (14.0) | — |

| Pain duration (M, SD) | 9.04 years (7.8) | — |

Electronic Diary

The PDA program signaled participants to complete five assessments each day, for 14 consecutive days, starting at 8:50 a.m. and occurring every 3 hr until 8:50 p.m. Frequent assessments helped minimize retrospective bias in ratings (Stone & Shiffman, 1994). Daily diary data obtained in this manner also appear to suffer little from reactivity effects that are sometimes caused by monitoring (Cruise, Broderick, Porter, Kaell, & Stone, 1996; Jamison et al., 2001). Variability in ratings within the day is also captured well by this method (Peters et al., 2000; Stone, Broderick, Porter, & Kaell, 1997). Electronic diaries with time-stamped entries also allowed us to accurately assess when ratings were made, something that cannot be done with paper diary methods (Jamison et al., 2001). Finally, the software we used to program the PDAs allowed us to include branching algorithms to reduce participant burden. We used the branching algorithms to direct participants to questions about anger expression and inhibition if a state anger threshold was crossed (see below), and to assess whether patients and spouses interacted with each other in the past 3 hr. If patients and spouses reported interacting, they were directed to questions asking about perceived support, criticism, and hostility from the spouse (per patient), and about whether they directed support, criticism, and hostility to the patient (per spouse). If couples did not interact, they were not asked these questions.

We used the Experience Sampling Program (ESP; Barrett & Feldman-Barrett, 2000) that operated on handheld Palm Zire 22 PDAs, running the Palm Operating System platform. The PDA program prevented participants from altering the items or data time stamps.

Measures

Patient and spouse state negative affect.

At each assessment, patients and spouses rated the extent to which they felt annoyed, irritable, and angry during the past 3 hr. These items were averaged to create a composite state anger score. Spouses also rated six other state affective items corresponding to anxiety and sadness. These items were averaged to create composite state anxiety and state sadness scores. Responses were made on 9-point scales with anchors at 0 (not at all), 2 (somewhat), 4 (much), 6 (very much), and 8 (extremely).

Patient behavioral anger expression and inhibition.

If any of the three state anger items were rated a 2 (somewhat) or greater, participants were asked about anger regulation using the following items:

When you felt irritated, annoyed, or angry during the past 3 hr, to what degree did you do the following?

I spoke or shouted about my anger or annoyance.

I did physical things like gesture, pound the table, slam doors, throw things, and so forth.

I kept my anger or annoyance to myself.

I hid from others how angry or annoyed I was.

These four items were rated on the same 9-point Likert scale as the state affect items described above. A behavioral anger expression variable was computed by summing the first two items, and a behavioral anger inhibition variable was computed by summing the last two items.

Patient-perceived spouse criticism, hostility, and support.

At each assessment, patients were asked, “Did you interact with your spouse during the last 3 hr?” If they responded, “yes,” then they indicated the average amount of criticism they received from their spouse during the previous 3 hr. Patient-perceived criticism was assessed with a variation on the Hooley and Teasdale (1989) item, asking “How critical of you was your spouse during the past 3 hr?” Similar to this criticism item, patients were asked to rate how hostile their spouse was during the past 3 hr. We defined hostility for patients as any negative or attacking remark, no matter how mild, especially remarks about the patient in general that are not intended to be helpful, corrective, or supportive in some way. These remarks by the spouse included those that are rejecting or that express dislike of the patient. Following Hooley (2007) and the Expressed Emotion literature, we treated criticism and hostility as separate constructs. Criticism and hostility, as perceived by patients and reported by spouses, were correlated and , respectively (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Means and SDs and Correlations Among Study Variables Aggregated Within Participants Over Time

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. State anger | 3.51 | 3.59 | |||||||||||

| 2. Anger inhibition | 5.58 | 3.73 | .38 | ||||||||||

| 3. Anger expression | 1.15 | 1.37 | .63 | .13 | |||||||||

| 4. Perceived support | 3.74 | 1.74 | .05 | .01 | .03 | ||||||||

| 5. Perceived criticism | .88 | 1.05 | .24 | .15 | .18 | −.30 | |||||||

| 6. Perceived hostility | .34 | .48 | .28 | .06 | .26 | −.26 | .45 | ||||||

| 7. Spouse-reported support | 3.86 | 1.64 | .01 | .01 | −.02 | .49 | −.01 | −.16 | |||||

| 8. Spouse-reported criticism | .45 | .45 | .23 | .04 | .23 | −.21 | .25 | .36 | −.18 | ||||

| 9. Spouse-reported hostility | .22 | .33 | .14 | −.03 | .22 | −.19 | .17 | .42 | −.20 | .74 | |||

| 10. Spouse anger | 2.12 | 2.05 | .18 | .06 | .15 | −.20 | .30 | .28 | −.16 | .51 | .51 | ||

| 11. Spouse anxiety | 2.01 | 2.12 | .17 | .12 | .15 | −.17 | .35 | .26 | −.03 | .54 | .49 | .88 | |

| 12. Spouse sadness | 1.35 | 1.88 | .23 | .02 | .16 | −.19 | .31 | .27 | −.13 | .53 | .57 | .80 | .82 |

Note. For all r values > .19.

p < .05.

Patients were also asked, “How supportive of you was your spouse during the last 3 hr?” We defined support in terms of whether the spouse was receptive to patient’s needs or helped the patient in some way. Responses were made on 9-point scales with anchors at 0 (not at all), 2 (somewhat), 4 (much), 6 (very much), and 8 (extremely).

Spouse-reported criticism and hostility directed toward patient.

A similar algorithm branch was used to ask spouses whether they had interacted with the patient, in which case they were to indicate the average amount of criticism and hostility they directed toward patients and how much support they provided. Responses were made on 9-point scales with anchors at 0 (not at all), 2 (somewhat), 4 (much), 6 (very much), and 8 (extremely).

Procedure

Patients and spouses were screened by phone, and eligible patients and spouses then attended an initial session during which they signed consent forms to participate and complete questionnaires. Patients and spouses were instructed to carry the PDAs with them throughout the day for 14 consecutive days. Research assistants described procedures and defined terms contained in the diary items for participants as well as provided printed instructions and phone support details for technical problems or other questions.

Starting at 8:50 a.m., and then again every 3 hr until 8:50 p.m., participants were prompted by the PDA alarm to complete assessments. Participants had 15 min following this alert in which to respond. After the initial alarm, the PDA would emit a signal every 30 s until participants responded. Participants were also given the option to tap the screen to dismiss the alarms and delay the signal as long as they completed the assessment within 15 min. If participants did not respond in any way within 15 min of the original prompt, the time period was coded as missing data. The data for each assessment session was time stamped. After 14 days of data collection, participants returned the PDA, data were downloaded, and participants were debriefed.

Data Preparation

All responses submitted past the 15-min response interval were discarded. After deleting these responses, out of the 7,350 possible total responses, there were 80.01–87.06% complete data for the various items and algorithm branches of the diary. This amount of complete data is in the range typically found in other electronic diary studies involving pain patients (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008). Patients reported interacting with spouses during 73.2% of intervals, whereas spouses reported interacting with patients during 72.4% of intervals. Patients and spouses had a (88.4%) level of agreement about speaking to each other during the same 3-hr intervals. All analyses involving anger and spouse responses used data when both spouses and patients reported interacting.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 (IBM, 2011). Our main analyses focused on concurrent and lagged relationships between patient behavioral anger regulation and spouse responses. For these analyses, hierarchical linear modeling was used. Predictor variables were centered using person mean centering, with parameters representing a person’s deviance from his or her own average over the course of the study (within-subjects effects). Autocorrelation of the dependent variable (DV) over time was accounted for by controlling for DV values measured 3 hr prior. The equations also adjusted for time since the start of the study to account for patient reactivity, and to account for the unequal spacing of time points due to the nighttime lag between 8:50 p.m. and 8:50 a.m. measurements. Random effects were included for intercept and time to account for individual differences at baseline and over the course of the study. We thus modeled statistical causality to the extent that change in predictor variables preceded and was correlated with change in subsequent DVs, while also ruling out potential extraneous variables (Duckworth, Tsukayama, & May, 2010).

Two general Level 1 models were fit. The first model estimated concurrent effects, and the second model estimated lagged effects. Concurrent models were those in which either patient behavioral anger expression or inhibition (IV) was related to patient-perceived spouse response variables or spouse-reported responses (e.g., criticism) at the same time (DV), while controlling for prior values of the spouse-related factor. The models also tested the hypothesis that the associations between anger and DVs would vary across patient sex by including sex as a Level-2 covariate. A representative combined Level-1 and Level-2 model for concurrent effects (i.e., all variables are measured at the same time point, aside from prior measurement of the dependent variable) is

where represents the time point, and represents the person. Time is measured in hours since the start of the study and is centered at 0 so that the intercept, , represents patient-perceived criticism at the first time point of the study. Behavioral anger expression is the person’s deviation in behavioral anger expression from his or her behavioral anger expression across the entire study. The DV, perceived criticism, is the patient’s present level of perceived criticism. Perceived criticism at represents the score of the DV at the prior time point (viz., 3 hr earlier). The interaction term, (Patient Behavioral Anger Expression at ), represents the entry of Level-2 covariate patient sex to moderate the association between patient anger expression and patient-perceived criticism from the spouse.

The general lagged effects model was the same as the concurrent effects model except that all of the predictor variables (IVs) were lagged or measured at the prior time point, 3 hr earlier. Lagged models tested whether either patient behavioral anger expression or inhibition predicted spouse responses (e.g., patient-perceived or spouse-reported criticism) 3 hr later while controlling for prior values of the spouse-related variables. As above, patient sex was included as a Level-2 covariate. Thus, the general lagged combined Level-1 and Level-2 model of behavioral anger expression and perceived criticism is

Results

Descriptive Values and Correlations

Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of study variables aggregated within participants over time. Aggregated patient state anger was significantly associated with patient behavioral anger expression, behavioral anger inhibition, perceived criticism, perceived hostility, and spouse-reported hostility toward the patient. Patient behavioral anger expression was significantly associated with patient-perceived hostility, and spouse-reported criticism, and hostility toward the patient. Patient perceptions were significantly associated with spouse reports of support, criticism, and hostility.

Concurrent Associations Between Anger Variables and Spouse Responses

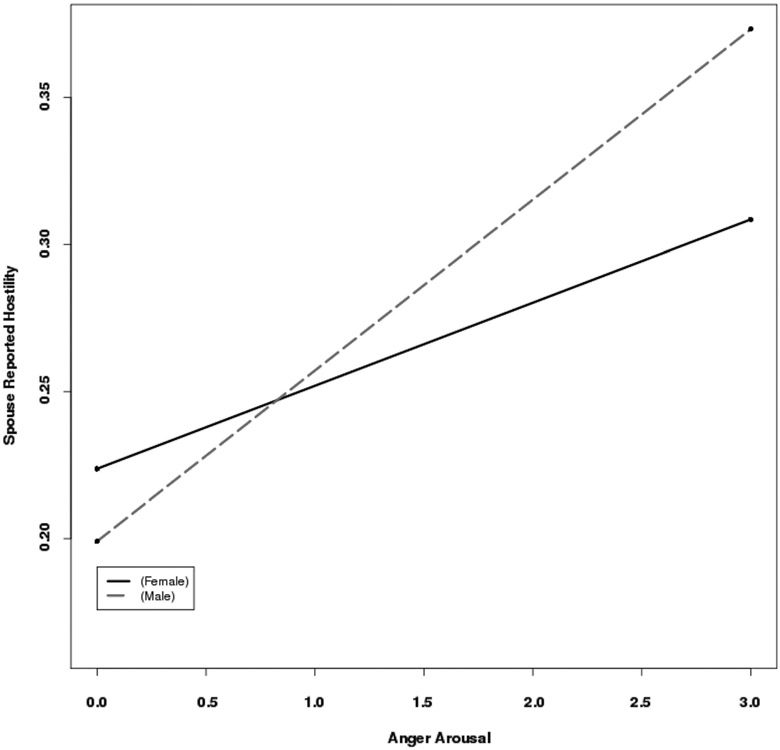

In concurrent analyses, the Patient State Anger × Sex interaction was nonsignificant for both patient-perceived support and spouse-reported support (Tables 3 and 4). However, main effects of patient state anger were significant, with greater patient anger related to decreases (relative to prior time point) in both patient-perceived (β = −.04, SE = .01, p < .001, f2 = .008) and spouse-reported support (β = −.04, SE = .01, p < .001, f2 = .006). The Patient State Anger × Sex interactions were significant for patient-perceived spouse criticism and hostility as well as for spouse-reported criticism and hostility (Tables 3 and 4). The interactions were dissected by computing simple slopes for male and female patients separately. The pattern of simple slopes across the four DVs was similar in that greater patient anger was related significantly to increases in critical and hostile responses by the spouse for both male and female patients, but the relationships were stronger among male patients. For example, for female patients, the simple slope for patient anger arousal and spouse reported hostility was β = .028 (SE = .006; z = 4.52, p < .001), whereas for male patients it was β = .058 (SE = .006, z = 9.75, p < .001). See Figure 1 for a graphical depiction of these relationships.

Table 3.

Concurrent Associations Between Patient Anger and Patient-Perceived Responses

| Hostility |

Criticism |

Support |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | |

| Intercept | ||||||||||||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .547 | .00 | .00 | .898 | .00 | .00 | .188 | |||

| Prior DV | .11 | .02 | .000 | .16 | .02 | .000 | .13 | .02 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .04 | .01 | .000 | .09 | .01 | .000 | −.05 | .01 | .001 | |||

| Gender | .18 | .11 | .094 | .22 | .21 | .301 | .03 | .34 | .929 | |||

| State Anger × Gender | .05 | .01 | .000 | .010 | .05 | .02 | .001 | .005 | .00 | .02 | .814 | |

| Intercept | .19 | .13 | .149 | .81 | .20 | .000 | 3.87 | .30 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .658 | .00 | .00 | .725 | .00 | .00 | .410 | |||

| Prior DV | .12 | .03 | .000 | .19 | .03 | .000 | .13 | .03 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .05 | .01 | .000 | .08 | .01 | .000 | −.03 | .02 | .108 | |||

| Gender | .07 | .03 | .010 | .10 | .04 | .025 | −.03 | .05 | .584 | |||

| Anger express | .35 | .15 | .024 | .34 | .24 | .163 | .08 | .37 | .827 | |||

| Anger Express × Gender | .07 | .04 | .054 | .003 | .08 | .05 | .153 | −.04 | .06 | .487 | ||

| Intercept | .18 | .11 | .108 | .70 | .17 | .000 | 3.74 | .26 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .582 | .00 | .00 | .604 | .00 | .00 | .532 | |||

| Prior DV | .16 | .03 | .000 | .16 | .03 | .000 | .20 | .03 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .08 | .01 | .000 | .11 | .01 | .000 | −.03 | .01 | .007 | |||

| Gender | .00 | .01 | .827 | .00 | .02 | .964 | .02 | .02 | .233 | |||

| Anger inhibit | .28 | .13 | .035 | .27 | .21 | .188 | .14 | .34 | .682 | |||

| Anger Inhibit × Gender | −.02 | .02 | .315 | −.02 | .02 | .470 | .00 | .03 | .948 | |||

Note. DV = dependent variable.

Table 4.

Concurrent Associations Between Patient Anger and Spouse-Reported Responses

| Hostility |

Criticism |

Support |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | |

| Intercept | .22 | .06 | .000 | .38 | .08 | .000 | 4.16 | .24 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .882 | .00 | .00 | .904 | .00 | .00 | .004 | |||

| Prior DV | .03 | .02 | .157 | .19 | .02 | .000 | .13 | .02 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .03 | .01 | .000 | .04 | .01 | .000 | −.03 | .01 | .009 | |||

| Gender | −.02 | .07 | .725 | .12 | .10 | .231 | −.06 | .32 | .853 | |||

| State Anger × Gender | .03 | .01 | .001 | .006 | .04 | .01 | .002 | .004 | .00 | .02 | .981 | |

| Intercept | .22 | .09 | .020 | .35 | .12 | .004 | 4.05 | .28 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .485 | .00 | .00 | .176 | .00 | .00 | .036 | |||

| Prior DV | −.05 | .03 | .106 | .17 | .03 | .000 | .14 | .03 | .000 | |||

| Prior state anger | .04 | .01 | .000 | .06 | .01 | .000 | −.01 | .01 | .499 | |||

| Gender | .00 | .02 | .884 | .05 | .13 | .696 | −.07 | .04 | .102 | |||

| Anger express | −.06 | .11 | .561 | −.06 | .03 | .043 | −.10 | .36 | .780 | |||

| Anger Express × Gender | .14 | .03 | .000 | .020 | .19 | .04 | .000 | .018 | .03 | .06 | .627 | |

| Intercept | .18 | .10 | .070 | .31 | .12 | .014 | 4.05 | .27 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .582 | .00 | .00 | .205 | .00 | .00 | .010 | |||

| Prior DV | −.04 | .03 | .161 | .17 | .03 | .000 | .15 | .03 | .000 | |||

| Prior state anger | .05 | .01 | .000 | .07 | .01 | .000 | −.01 | .01 | .195 | |||

| Gender | −.01 | .01 | .293 | −.01 | .02 | .574 | .02 | .02 | .247 | |||

| Anger inhibit | −.04 | .11 | .742 | .08 | .14 | .572 | −.10 | .36 | .775 | |||

| Anger Inhibit × Gender | .00 | .02 | .949 | −.03 | .02 | .249 | −.01 | .03 | .693 | |||

Note. DV = dependent variable.

Figure 1.

Patient sex moderates the relationship between anger arousal and spouse-reported criticism.

The Patient Anger Inhibition × Sex interactions were all nonsignificant (see Tables 3 and 4). However, the main effect for patient anger inhibition on spouse-reported criticism was significant, such that greater patient anger inhibition was related significantly to decreased spouse-reported criticism directed to the patient, and this association remained significant after controlling for state anger.

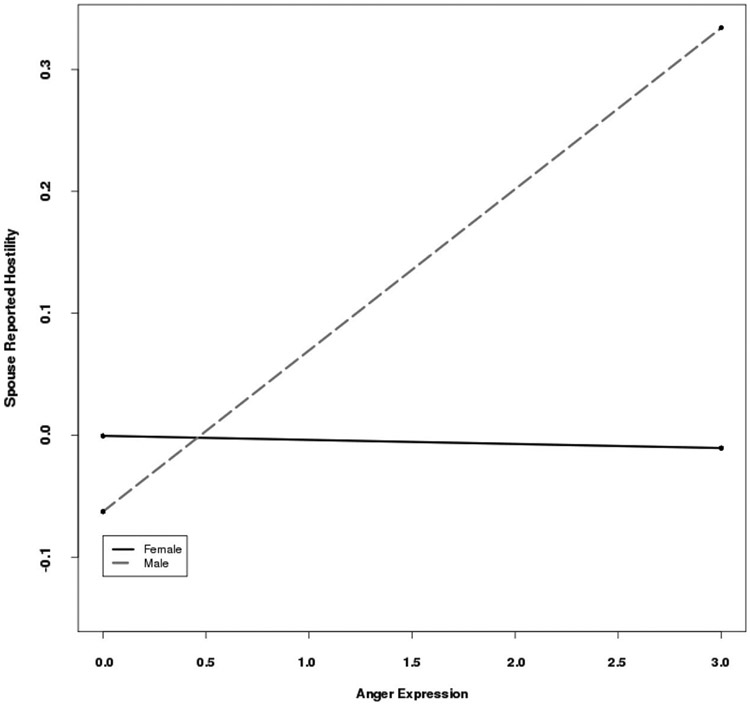

The Patient Anger Expression × Sex interactions for patient-perceived and spouse-reported support were nonsignificant (Tables 3 and 4). The main effects of patient anger expression for both DVs were significant, with greater patient anger expression associated with decreased patient-perceived and spouse-reported support. These associations remained significant with patient state anger controlled. The Patient Anger Expression × Sex interactions for patient-perceived criticism and hostility were also nonsignificant. The main effects, however, were significant, such that greater patient anger expression was significantly associated with increased patient perceptions of spouse criticism and hostility. With state anger controlled, these associations remained significant. The Patient Anger Expression × Sex interactions for spouse-reported criticism and hostility were significant. The pattern of simple slopes across the two DVs was similar, with greater patient anger expression related significantly to increases in critical and hostile responses by the spouse only for male patients. For example, for female patients, the simple slope of patient anger expression on spouse-reported hostility was β = −0.003 (SE = .023, z = .145, p = .884), whereas for male patients it was β = 0.13 (SE = .020, z = 6.54, p < .001). See Figure 2 for a graphical depiction of these relationships.

Figure 2.

Patient sex moderates the relationship between anger expression and spouse-reported criticism.

Lagged Associations Between Anger Variables and Spouse Responses

The 3-hr lagged State Anger × Sex interaction was nonsignificant for patient-perceived support, but was significant for spouse-reported support (B = .05, SE = .01, p = .012, f2 = .006). Simple slopes analyses showed that greater state anger was significantly associated with less spouse-reported support 3 hr later among female patients (β = −0.03, SE = .01, z = −2.456, p < .01) but not for male patients (β = .01, SE = −.01, z = 1.007, p > .10). The Patient Lagged State Anger × Sex interaction for patient-perceived spouse hostility was also significant (see Table 5). Results of simple slopes analyses showed that greater patient anger was related significantly to increases in perceived hostility 3 hr later for male patients (β = 0.034, SE = .008, z = 4.254, p < .001) but not for female patients (β = 0.00, SE = .008, z = .997, p > .10). Although the Patient Lagged State Anger × Sex interaction for spouse-reported hostility was nonsignificant, the main effect was significant, such that greater patient state anger predicted increased spouse-reported hostility directed to the patient 3 hr later. The Patient Lagged Anger Expression × Sex interaction for patient-perceived spouse hostility was, however, significant. Simple slopes analyses showed that greater patient anger expression was related significantly to increases in perceived hostility 3 hr later for male patients (β = .075, SE = .027, z = 2.815, p < .005) but not for female patients (β = −.029, SE = .030, z = −0.974, p > .10). No other lagged relationships for patient anger arousal, anger expression, or inhibition were significant.

Table 5.

Lagged Associations Between Patient Anger and Patient-Perceived Responses

| Hostility |

Criticism |

Support |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | |

| Intercept | .22 | .08 | .006 | 0.82 | 0.16 | .000 | 3.84 | 0.25 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .675 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .262 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .521 | |||

| Prior DV | .12 | .02 | .000 | 0.16 | 0.02 | .000 | 0.17 | 0.02 | .000 | |||

| Prior state anger | .01 | .01 | .356 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .799 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .612 | |||

| Gender | .17 | .10 | .100 | 0.09 | 0.20 | .662 | 0.06 | 0.34 | .859 | |||

| Prior State Anger × Gender | .03 | .01 | .003 | .007 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .307 | −0.03 | 0.02 | .226 | ||

| Intercept | .27 | .12 | .021 | 0.97 | 0.19 | .000 | 3.75 | 0.30 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .885 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .070 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .957 | |||

| Prior DV | .16 | .03 | .000 | 0.23 | 0.03 | .000 | 0.21 | 0.03 | .000 | |||

| Prior state anger | .02 | .01 | .052 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .873 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .844 | |||

| Gender | .21 | .13 | .105 | −0.06 | 0.04 | .200 | 0.06 | 0.05 | .274 | |||

| Prior anger express | −.03 | .03 | .330 | 0.14 | 0.22 | .547 | 0.15 | 0.38 | .702 | |||

| Prior Express × Gender | .10 | .04 | .006 | .008 | 0.12 | 0.05 | .031 | .005 | −0.11 | 0.06 | .082 | |

| Intercept | .26 | .12 | .028 | .97 | .19 | .000 | 3.76 | .30 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .779 | .00 | .00 | .053 | .00 | .00 | .890 | |||

| Prior DV | .17 | .03 | .000 | .24 | .03 | .000 | .21 | .03 | .000 | |||

| Prior state anger | .02 | .01 | .010 | .00 | .01 | .790 | −.01 | .02 | .738 | |||

| Gender | .00 | .02 | .872 | −.01 | .03 | .589 | .02 | .03 | .455 | |||

| Prior anger inhibit | .23 | .13 | .087 | .16 | .23 | .477 | .12 | .38 | .755 | |||

| Prior Anger Inhibit × Gender | .01 | .02 | .721 | .03 | .03 | .290 | −.04 | .04 | .335 | |||

Note. DV = dependent variable.

Associations Between Patient Anger and Spouse Negative Affect

In concurrent analyses, the Patient State Anger × Sex interactions were significant for spouse state anger, anxiety, and sadness (see Table 6). The pattern of simple slopes across the three DVs was similar in that greater patient anger was related significantly to increases in spouse anger, anxiety, and sadness for both male and female patients, but the relationships were stronger for male patients. For example, for female patients, the simple slope for patient anger and spouse anxiety was β = .089 (SE = .019, z = 4.613, p < .001), whereas for male patients, β = .176 (SE = .019, z = 9.267, p < .001).

Table 6.

Concurrent Associations Between Patient Anger and Spouse Affect

| Sad |

Anxious |

Angry |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | B | SE | p | f 2 | |

| Intercept | 1.37 | .30 | .000 | 2.32 | .32 | .000 | 2.38 | .33 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .017 | .00 | .00 | .958 | .00 | .00 | .780 | |||

| Prior time DV | .34 | .02 | .000 | .25 | .02 | .000 | .19 | .02 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .06 | .02 | .000 | .09 | .02 | .000 | .17 | .02 | .000 | |||

| Gender | −.35 | .40 | .385 | −.51 | .42 | .229 | −.29 | .43 | .506 | |||

| State Anger × Gender | .13 | .02 | .000 | .010 | .09 | .03 | .001 | .004 | .14 | .03 | .000 | .006 |

| Intercept | 1.10 | .41 | .008 | 2.19 | .42 | .000 | 2.39 | .47 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .001 | .00 | .00 | .145 | .00 | .00 | .400 | |||

| Prior time DV | .33 | .03 | .000 | .26 | .03 | .000 | .21 | .03 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .09 | .02 | .000 | .10 | .02 | .000 | .19 | .03 | .000 | |||

| Anger express | −.02 | .07 | .829 | −.07 | .07 | .320 | .00 | .09 | .971 | |||

| Gender | −.16 | .52 | .761 | −.34 | .53 | .523 | −.08 | .58 | .887 | |||

| Anger Express × Gender | .42 | .09 | .000 | .021 | .35 | .09 | .000 | .012 | .59 | .12 | .000 | .019 |

| Intercept | .98 | .41 | .018 | 2.11 | .42 | .000 | 2.18 | .47 | .000 | |||

| Time | .00 | .00 | .002 | .00 | .00 | .170 | .00 | .00 | .432 | |||

| Prior time DV | .33 | .03 | .000 | .27 | .03 | .000 | .22 | .03 | .000 | |||

| State anger | .13 | .02 | .000 | .13 | .02 | .000 | .26 | .03 | .000 | |||

| Anger inhibit | −.01 | .04 | .884 | .02 | .04 | .652 | −.04 | .05 | .401 | |||

| Gender | −.09 | .52 | .856 | −.30 | .53 | .571 | −.01 | .58 | .985 | |||

| Anger Inhibit × Gender | −.04 | .05 | .473 | −.08 | .05 | .132 | −.09 | .07 | .211 | |||

Note. DV = dependent variable.

The Patient Anger Inhibition × Sex interactions were nonsignificant in predicting spouse anxiety and sadness, as were the main effects of patient anger inhibition. The main effect of patient anger inhibition on spouse anger, however, was significant, such that greater patient anger inhibition was significantly associated with decreased spouse state anger.

The Patient Anger Expression × Sex interactions for spouse anger, anxiety, and sadness were also significant. The pattern of simple slopes across the three DVs was similar in that greater patient anger expression was related significantly to increases in spouse anger, anxiety, and sadness only for male patients. For example, the simple slope for female patient anger expression and spouse-reported anger was β = −.003 (SE = .092, z = −.037, p > .10), whereas for male patients it was β = .587 (SE = .081, z = 7.224, p < .001).

Lagged analyses showed that patient anger arousal and anger regulation were not significantly associated with spouse negative affect 3 hr later.

Spouse State Negative Affect When Patient Was Present Versus Absent

Mixed models were used to compare mean differences in spouse state negative affect when the patient was present versus absent, aggregated across all observations. Patient presence and absence was dummy coded (0 = absent, 1 = present). All the Presence/Absence × Sex interactions were nonsignificant. However, the main effects for presence/absence were significant. Spouse-reported state anger was significantly higher when patients were present (M = 2.37, SE = .21) than when they were not (M = 1.86, SE = .21), t = 5.53, p < .001. Spouse sad mood was also significantly higher when patients were present (M = 1.45, SE = .19) than when they were not (M = 1.25, SE = .19), t = 2.96, p = .003. Finally, spouse state anxiety was significantly higher when patients were present (M = 2.11, SE = .21) than when they were not (M = 1.90, SE = .21), t = 2.80, p = .005. Together, these findings suggest that spouses of people experiencing chronic pain report greater negative affect when in the presence of the patient than when they were not.

Discussion

Results of this study based on daily diary data suggest that patient anger arousal and expression may negatively affect the interpersonal environment of married couples coping with chronic low back pain, especially among male patients and their female spouses. Patient anger—particularly male patient anger—might increase psychosocial vulnerability to chronic pain via adverse effects on spouse interpersonal behavior.

Concurrent analyses revealed that greater within-patient anger arousal was related to decreased patient perceived spouse support and increased perceived spouse criticism and hostility directed at the patient. Identical relationships were also found for spouses’ own reports of their levels of support, criticism, and hostility directed to patients. Thus, greater patient anger arousal at, for example, 9:00 a.m. was related to simultaneous changes in both patient perceptions of spouse behavior and spouse reports of their own supportive, critical, and hostile behavior at 9:00 a.m. In addition, greater patient anger arousal at, for example, 9:00 a.m. was also related to increases in spouse-reported anger, anxiety, and sad mood at 9:00 a.m. Of note, although these associations were significant for couples containing either male or female patients, the significant interactions we found for patient-perceived and spouse-reported criticism and hostility and spouse negative affect were stronger for couples in which the male was experiencing chronic pain.

Moreover, greater patient verbal and physical expression of anger was related to patient perceptions of decreased spouse support and increased criticism and hostility in ways identical to relationships found for anger arousal. The same pattern emerged for spouse reports of support directed to patients. These associations remained significant when anger arousal was statistically controlled. Unlike for anger arousal, however, significant interactions revealed that patient anger expression was related significantly to increases in spouse reports of critical and hostile responses to patients and to increases in spouse negative affect only among couples with male patients. For couples with female patients, anger expression by the patient was not related significantly to increases in critical and hostile responses by male spouses, or to increases in negative affect among male spouses.

Lagged analyses revealed that for both male and female patients, greater initial patient anger arousal predicted later increases in spouse reports of hostility toward the patient. Thus, for example, patient anger arousal at 9:00 a.m. influenced spouse accounts of their hostility toward the patient at 12:00 p.m. However, lagged effects of both anger arousal and anger expression on patient perceptions of spouse hostility 3 hr later were confined to male patients. Thus, male patient anger arousal and its expression at 9:00 a.m. influenced patients’ perceptions of spouse hostility at 12:00 p.m.

Taken together, these findings suggest that chronic pain patient anger arousal and its verbal and physical expression in the presence of the spouse are related to a pervasive pattern of negative spouse responses to the patient in the form not only of decreased support, but also in the form of increased overt criticism and hostility apparent to both partners. In addition, patient anger arousal was related to increases in spouses’ own feelings of anger, anxiety, and sadness. These findings also point to the distinction between the patient merely becoming angry and how the anger is regulated. While patient anger arousal was related to negative spouse responses toward the patient and to their own mood, the overt expression of anger may magnify these negative responses and so become uniquely important in affecting the patient’s interpersonal environment. Importantly, however, the expression of anger by male patients was related to spouse reports of criticism and hostility directed to the patient and their reports of increased negative affect, whereas this was not the case for couples with female patients. The overt verbal and physical expression of anger by male patients may represent a particularly deleterious factor in fomenting a critical, hostile, and emotionally upsetting interpersonal environment. Insofar as such an environment represents a psychosocial vulnerability, patient anger and expression can indirectly contribute to poor adjustment via strained and damaged social relationships, particularly for men coping with chronic pain.

Although lagged analyses revealed some evidence for longitudinal effects, the bulk of results suggest that the predominant kind of relationship was concurrent. Although concurrent relationships suggest that patient anger and negative spouse responses occur within the same 3-hr period, causal inferences are limited. It may be the case that reverse paths obtain in that initial spouse criticism and hostility could predict later patient anger arousal and its expression to the antagonist.

Of note were significant findings for patient presence versus patient absence. Spouses reported greater feelings of anger, anxiety, and sadness when they were with both male and female patients than when they were not. These findings, coupled with significant relationships among patient anger arousal, its expression, and increases in spouse negative affect hint that patient anger may be related to a pattern of chronic elevated spouse negative mood when they are with the patient. These results are consistent with Coyne’s interpersonal model in which the patient in need of support ironically evokes in others feelings of irritation, nervousness, and feeling “down.” Even in the absence of patient anger at any given moment, the spouse may become conditioned to be critical and rejecting toward someone who routinely makes them feel distressed.

Patient anger inhibition was related significantly to only one spouse response, indicating that greater anger inhibition was related to concurrent decreases in spouse criticism. Given that all other associations for anger inhibition were nonsignificant, patient anger inhibition may not strongly influence spouse responses toward the patient or the spouses’ mood. On the other hand, anger inhibition in questionnaire, laboratory, and diary studies has been linked negatively to patient pain and function (Burns et al., 2015; Burns et al., 2008). Taken together, these findings suggest that anger inhibition may indeed exert detrimental effects on patient pain and function, but it may do so primarily via intrapersonal pathways. Patient anger inhibition may not negatively influence spouse behavior toward the patient or their own mood because the inhibition hides the anger from spouses. Alternatively, spouse responses and mood may only be affected by overt displays of anger—anger expression—that alter the emotional tenor of a situation, are directed toward the spouse, and/or which invite responses from the spouse. Patient anger inhibition—even if the anger arousal is noticed by spouses—may simply be easier to bear.

Results of the present study extend previous findings in at least three ways. First, our use of diary methods allowed us to capture for the first time relationships between patient anger and actual spouse responses to that anger as it unfolded in daily life. Many previous studies used questionnaires to get assessments (mostly from patients) of variability in patient anger and spouse responses cross-sectionally (Burns et al., 1996; Johansen & Cano, 2007; Schwartz et al., 1991). Here, with assessments 5 times per day, we gained a more fine-grained view of how patient anger and spouse criticism and hostility are intimately connected. Second, we asked spouses to report on their own responses to patients. Most previous studies have examined relationships between patient reports of their own mood and behavior and their perceptions of spouse responses (Burns et al., 1996; Druley et al., 2003; Julkunen et al., 2009; Schwartz et al., 1991), thus potentially confounding estimates of the associations among these phenomena with common method variance due to the exclusive examination of within-person associations. Here, spouse reports of their own levels of support, criticism, and hostility allowed us to examine cross-spouse associations in which patient reports of patient behavior were related to spouse reports of spouse behavior. Beyond finding that an angry patient tended to perceive that their spouse was not nice to them, we found that spouses reported that they were indeed not nice to the patient when he or she was angry. Of note, the correlations between patient perceptions of spouse support, criticism and hostility, and spouse reports of their own behavior toward the patient were of moderate size (range: r = .25 to r = .49). These findings also indicate some degree of correspondence between patient and spouse ratings of spouse behavior, bolstering the validity of the assessment of spouse support, criticism, and hostility toward the patient. Third, we found a consistent pattern of sex differences, suggesting that female spouses may respond more negatively to male patient anger arousal and its expression than do male spouses in response to female patients.

Some caveats must be issued. First, as is common with daily diary methods, especially when frequent assessments are made, we used single items to tap key constructs (e.g., perceived criticism), and we used only two items to assess behavioral anger expression and two items to assess behavioral anger inhibition. From the standpoint of psychometrics, this is certainly not ideal. The anger regulation items were adapted from Spielberger’s widely used and validated trait measures of anger-out and anger-in (Spielberger & Reheiser, 2004), and we have reported initial psychometric data for these items (Burns et al., 2015). Still, these data represent preliminary steps to assess reliability and validity of this kind of anger regulation assessment, and caution should be taken when interpreting findings. Second, on one level, the 3-hr lags in assessments may have been too long to capture all of the effects of patient anger arousal and anger regulation on later spouse responses to the patient. Many of the significant concurrent relationships reflect associations collapsed across 3 hr. Significant prospective effects may have emerged had the lags been 1 hr. Thus, more frequent assessments, possibly every hour, may be needed to properly reveal prospective effects of initial patient anger on later spouse criticism. On another level, we confined analyses here to 3-hr lags, as opposed to, say, 6- or 9-hr lags. We chose the 3-hr lag to focus on events linked relatively closely in time and to limit the number of analyses.

Third, the magnitudes of effect size coefficients we report suggest that most of the effects we found were small. It is worth noting, however, that small magnitude effects between patient daily anger and spouse critical and hostile responses might easily accumulate in their corrosive impact when repeated over weeks, months, or even years (Abelson, 1985), ultimately producing a chronically unpleasant interpersonal environment. As we have shown previously, patient perceptions of spouse criticism and hostility are related to increased pain and decreased function, and indeed to spouse observations of increased patient pain behavior (Burns et al., 2013). We have also shown that patient anger arousal and anger expression are related to increased pain and decreased function. Taken together, findings support interpersonal pathways along which patient anger, especially expressed anger, may be a key factor in creating a chronic critical and hostile interpersonal environment. Here, spouse support would erode, and criticism and hostility would increase, thus undermining patients’ ability to adjust adequately to chronic pain.

Results from a number of studies using diverse methods all point to the potential clinical utility of altering problematic anger-related factors as a way to improve patient pain and function. Extension of CBT-based anger reduction interventions to treat problematic anger and anger regulation among chronic pain patients may prove profitable in affecting intrapersonal adjustment. Cognitive restructuring to alter anger-inducing appraisals coupled with relaxation training—per Deffenbacher (1999)—could reduce deleterious effects of anger on pain intensity. Our findings also expand knowledge regarding how patient anger and anger regulation are related adversely to pain and function by shedding light on the social component of a biopsychosocial model. Namely, results reveal the importance of interpersonal functioning for optimal adjustment to chronic pain, particularly among male patients. Present results illuminate interpersonal pathways according to which patient anger may undermine optimal adjustment. As well, our findings suggest clinical efforts may need to be expanded to include interpersonal functioning with significant others, such as spouses. CBT-based anger reduction interventions may need to be modified to manage both patient anger and to alter spouse responses to it. Here, we focused only on the spouse. However, the interpersonal effects of patient anger may even extend to other family, friends, and coworkers. Thus, the application and extension of anger management techniques to treating problematic anger and anger regulation for chronic pain patients may benefit from encompassing the larger interpersonal environment of patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Nursing Research Grant R01 NR010777 (John W. Burns: PI). The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

John W. Burns, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center

James I. Gerhart, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center

Stephen Bruehl, Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Kristina M. Post, Department of Psychology, University of La Verne

David A. Smith, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame

Laura S. Porter, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center

Erik Schuster, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center.

Asokumar Buvanendran, Department of Anesthesiology, Rush University Medical Center.

Anne Marie Fras, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center.

Francis J. Keefe, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center

References

- Abelson RP (1985). A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 129–133. 10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett DJ, & Feldman-Barrett L (2000). The Experience-Sampling Program (ESP). Retrieved from http://www2.bc.edu/~barretli/esp/ [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, Burns JW, Chung OY, Ward P, & Johnson B (2002). Anger and pain sensitivity in chronic low back pain patients and painfree controls: The role of endogenous opioids. Pain, 99, 223–233. 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00104-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, Liu X, Burns JW, Chont M, & Jamison RN (2012). Associations between daily chronic pain intensity, daily anger expression, and trait anger expressiveness: An ecological momentary assessment study. Pain, 153, 2352–2358. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Gerhart JI, Bruehl S, Peterson KM, Smith DA, Porter LS, … Keefe FJ (2015). Anger arousal and behavioral anger regulation in everyday life among patients with chronic low back pain: Relationships to patient pain and function. Health Psychology, 34, 547–555. 10.1037/hea0000091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Johnson BJ, Mahoney N, Devine J, & Pawl R (1996). Anger management style, hostility and spouse responses: Gender differences in predictors of adjustment among chronic pain patients. Pain, 64, 445–453. 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00169-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Peterson KM, Smith DA, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Schuster E, & Kinner E (2013). Temporal associations between spouse criticism/hostility and pain among patients with chronic pain: A within-couple daily diary study. Pain, 154, 2715–2721. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Quartana PJ, & Bruehl S (2008). Anger inhibition and pain: Conceptualizations, evidence and new directions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 259–279. 10.1007/s10865-008-9154-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, & DeLongis A (1986). Going beyond social support: The role of social relationships in adaptation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 454–460. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruise CE, Broderick J, Porter L, Kaell A, & Stone AA (1996). Reactive effects of diary self-assessment in chronic pain patients. Pain, 67, 253–258. 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL (1999). Cognitive-behavioral conceptualization and treatment of anger. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doster JA, Purdum MB, Martin LA, Goven AJ, & Moorefield R (2009). Gender differences, anger expression, and cardiovascular risk. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197, 552–554. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181aac81b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druley JA, Stephens MAP, Martire LM, Ennis N, & Wojno WC (2003). Emotional congruence in older couples coping with wives’ osteoarthritis: Exacerbating effects of pain behavior. Psychology and Aging, 18, 406–414. 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Tsukayama E, & May H (2010). Establishing causality using longitudinal hierarchical linear modeling: An illustration predicting achievement from self-control. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1, 311–317. 10.1177/1948550609359707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (1996). Structured clinical interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP). New York, NY: Biometrics Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BE, & Linden W (2005). Curvilinear relationships of expressed anger and blood pressure in women but not in men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 59, 97–102. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM (2007). Expressed emotion and relapse of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 329–352. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, & Teasdale JD (1989). Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: Expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 229–235. 10.1037/0021-843X.98.3.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison RN, Raymond SA, Levine JG, Slawsby EA, Nedeljkovic SS, & Katz NP (2001). Electronic diaries for monitoring chronic pain: 1-year validation study. Pain, 91, 277–285. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00450-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen SA, Spinhoven P, & Brosschot JF (2001). Experimentally induced anger, cardiovascular reactivity, and pain sensitivity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51, 479–485. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00222-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen AB, & Cano A (2007). A preliminary investigation of affective interaction in chronic pain couples. Pain, 132, S86–S95. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julkunen J, Gustavsson-Lilius M, & Hietanen P (2009). Anger expression, partner support, and quality of life in cancer patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66, 235–244. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Rosenberg R, & Jacob MC (1994). Anger expression and chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17, 57–67. 10.1007/BF01856882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane C, & Hobfoll SE (1992). How loss affects anger and alienates potential supporters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 935–942. 10.1037/0022-006X.60.6.935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson RA, Gramling SE, Ong JC, & Buenevar L (2003). Differences in anger expression between individuals with and without headache after controlling for depression and anxiety. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 43, 651–663. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters ML, Sorbi MJ, Kruise DA, Kerssens JJ, Verhaak PFM, & Bensing JM (2000). Electronic diary assessment of pain, disability and psychological adaptation in patients differing in duration of pain. Pain, 84, 181–192. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00206-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L, Slater MA, Birchler GR, & Atkinson JH (1991). Depression in spouses of chronic pain patients: The role of patient pain and anger, and marital satisfaction. Pain, 44, 61–67. 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90148-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, & Hufford MR (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW (1992). Hostility and health: Current status of a psychosomatic hypothesis. Health Psychology, 11, 139–150. 10.1037/0278-6133.11.3.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Uchino BN, Berg CA, Florsheim P, Pearce G, Hawkins M, … Yoon HC (2008). Associations of self-reports versus spouse ratings of negative affectivity, dominance, and affiliation with coronary artery disease: Where should we look and who should we ask when studying personality and health? Health Psychology, 27, 676–684. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, & Reheiser EC (2004). Measuring anxiety, anger, depression, and curiosity as emotional states and personality traits with the STAI, STAXI and STPI. In Hilsenroth MJ & Segal DL (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2: Personality assessment (pp. 70–86). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Broderick JE, Porter LS, & Kaell AT (1997). The experience of rheumatoid arthritis pain and fatigue: Examining momentary reports and correlates over one week. Arthritis Care & Research, 10, 185–193. 10.1002/art.1790100306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, & Shiffman S (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez EC (2006). Sex differences in the relation of depressive symptoms, hostility, and anger expression to indices of glucose metabolism in nondiabetic adults. Health Psychology, 25, 484–492. 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (1986). Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 416–423. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Middendorp H, Lumley MA, Moerbeek M, Jacobs JWG, Bijlsma JWJ, & Geenen R (2010). Effects of anger and anger regulation styles on pain in daily life of women with fibromyalgia: A diary study. European Journal of Pain, 14, 176–182. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade JB, Price DD, Hamer RM, Schwartz SM, & Hart RP (1990). An emotional component analysis of chronic pain. European Journal of Pain, 40, 303–310. 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91127-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortman CB, & Conway TL (1985). The role of social support in adaptation and recovery from physical illness. In Cohen S & Syme SL (Eds.), Social support and health (pp. 281–302). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Clark MS, Lemay EP Jr., Salovey P, & Monin JK (2011). Responding to partners’ expression of anger: The role of communal motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 229–241. 10.1177/0146167210394205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]