Abstract

Introduction:

Stigmatization of an opioid addiction serves as a barrier to seeking substance use treatment. As opioid use and overdoses continue to rise and affect minority populations, understanding the impact that race and other identities have on stigma is pertinent.

Methods:

This study aimed to examine the degree to which race and other identity markers (i.e., gender and type of opioid used) interact and drive the stigmatization of an opioid addiction. To assess public perceptions of stigma, a randomized, between-subjects case vignette study (n = 1833) was conducted with a nation-wide survey. Participants rated a hypothetical individual who became addicted to opioids on four stigma indices (responsibility, dangerousness, positive affect and negative affect) based on race (White or Black), gender (male or female) and end point (an individual who transitioned to using heroin or who continued using prescription painkillers).

Results:

Our results first showed that the White individual had higher stigma ratings compared to the Black individual (range of partial η2 = .002 −.004). An interaction effect demonstrated that a White female was rated with higher responsibility for opioid use than a Black female (Cohen’s d = .21) and a Black male was rated with higher responsibility for opioid use than a Black female (Cohen’s d = .26). Lastly, we showed that a male and an individual who transitioned to heroin had higher stigma than a female and an individual who continued to use prescription opioids (range of partial η2 = .004 −.007).

Conclusions:

This study provides evidence that information about multiple identities can impact stigmatizing attitudes, which can provide deeper knowledge on the development of health inequities for individuals with an opioid addiction.

Keywords: race, gender, opioids, stigma, heroin, nonmedical prescriptions

Introduction

Over the past three decades, the United States has been battling an opioid crisis with no end in the foreseeable future. Despite a reduction in opioid prescription misuse, due in part to restrictive policy measures, discontinuation of prescription opioids may lead to the use of other forms of opioids such as heroin (Jones, 2013; Martins et al., 2019) and a greater increase in overdose and suicide deaths (Oliva et al., 2020). In addition, the opioid epidemic has led to a greater use of illicit fentanyl and its analogs (Ciccarone, 2017) and a spike of fentanyl overdoses (Spencer et al., 2019), which has only worsened the ongoing problem.

In the wake of the impact that the opioid crisis has had on communities, more evidence is emerging on the devastating effects it is having on minority individuals. Despite a historical association between overdose deaths and White, middle-class individuals at the onset of the opioid epidemic, data have shown a shift in trends over the past twenty years, with rates of overdose deaths may be doubling among Black individuals (James & Jordan, 2018). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the rates of opioid overdose deaths and has disproportionately impacted minority communities, with an increase in deaths in 2020 compared to 2019 and more Black individuals overdosing than White individuals (Patel et al., 2021).

In addition to the increasing racial disparities concerning overdose deaths, other manifestations of racial biases have further contributed to health inequities. Studies have demonstrated that Black individuals are less likely to be prescribed prescription opioids due to biases about pain tolerance in minorities (James & Jordan, 2018; Meghani et al., 2012), which has the unintended effect of leading minority individuals to seek illicit forms of opioids (Drake et al., 2020). In addition, minority individuals may be less likely to receive substance use treatment due to lack of access or financial barriers (Lagisetty et al., 2019). Furthermore, women in general, and specifically Black women, are less likely to engage in treatment and to have access to appropriate levels of care (Green, 2006; Redmond et al., 2020).

Given persistent racial health disparities, it is especially important to consider the effect that race has on the stigmatization of substance use. Stigma remains a strong barrier to seeking substance use treatment. Stigma is a multifaceted concept and can be a negative belief or stereotype and may lead to discrimination of an individual or groups of individuals (Crocker et al., 1998; Goffman, 1963). Stigma can be in the form of self/internalized stigma felt by an individual person, public stigma projected on behalf of the perceiver(s) about the individual(s), or structural stigma, which are institutional polices or societal conditions that place restrictions or inequities on an individual.

Research has indicated that stigma towards people who use opioids may depend on characteristics such as gender (Goodyear & Chavanne, 2020; Goodyear et al., 2018), race (Kulesza et al., 2016) or social class (Wood & Elliott, 2020). Our previous work has demonstrated that an individual framed as a male was rated with higher public stigma than an individual framed as female. Since social identities such as race, gender and economic status often interact, it is vital to look at how these characteristics intersect and to understand their complex effects in worsening health disparities (Bowleg, 2012). To our knowledge, there have been only two studies that have investigated race and public stigma towards individuals with addictions from an intersectional standpoint. Wood and Elliott (2020) found that participants judged working-class individuals addicted to opioids more harshly than middle-class individuals and expressed greater stigma toward a White individual than a Black individual. They also searched for, but did not find, differences across gender. Another study investigated differences across gender and race (White, Black and Latino/a) among persons who inject drugs and found no effect of race or gender on explicit stigma (Kulesza et al., 2016). However, they did show that a Latino/a person who injected drugs was implicitly rated more deserving of punishment (as opposed to help) compared to a White, but not a Black, person.

We aim to extend these limited findings by examining the degree to which race and other identity markers (i.e., gender and type of opioid used) interact and how they drive the stigmatization of an opioid addiction. With the past history of health disparities and negative biases towards minority individuals, we hypothesized that a Black individual would be stigmatized more than a White individual. Based on our past research on the role of gender and the type of opioid used (Goodyear & Chavanne, 2020; Goodyear et al., 2018; Weeks & Stenstrom, 2020), we also hypothesized that a male would be stigmatized more than a female and an individual who transitioned to heroin from painkillers would be stigmatized more than an individual who continued to use painkillers.

Methods

Participants

Participants were ≥ 18 years old, lived in the United States and were recruited and paid through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk; http://www.mturk.com) (n = 1833). MTurk is a crowdsourcing platform that connects “Requesters,” who have online tasks to be completed, and “Workers,” allowing researchers to access a large pool of participants. After accepting the request on MTurk, participants were taken to Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com), where they completed the anonymous online survey. All participants were randomly assigned to one of eight possible conditions (see vignettes below) and the survey took 10-15 minutes to complete. Participants were informed that they would be asked comprehension questions throughout the survey to ensure they were paying attention and 16% participants who did not answer these questions correctly were excluded from the analyses (2,182 completers, 349 excluded). This study was approved by Brown University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Vignettes

The vignette varied by three conditions: target race (Black or White), target gender (male or female) and end point (heroin or pills). The hypothetical individual was either Black or White, male or female and transitioned to injecting heroin or continued taking prescription painkillers.

Vignette:

Recent reports have shown that opioid use among Black/White Americans has increased over the years. The following scenario describes a Black/White man/woman who has an opioid addiction.

For the past several years, this Black/White man/woman has been using prescription opioid painkillers. Despite frequent attempts to stop over the years, he/she has had a persistent desire to use and has been unable to resist his/her cravings. Opioid use has caused him/her to have many problems with work and has significantly damaged his/her relationships with family and friends.

Nowadays, opioid prescription painkillers have become difficult/remained easy to find. He/she spends much of his/her time obtaining and injecting heroin/taking painkillers.

Measures

Participants rated the hypothetical individual in the vignette on interval items for the six stigma questions: 1) How responsible is the person in the scenario for his/her drug use? (1 is not responsible at all and 6 is completely responsible), 2) How dangerous is the person in the scenario? (1 is not dangerous at all and 6 is extremely dangerous), 3) How much sympathy do you have for the person in the scenario? (1 is not at all sympathetic and 6 is extremely sympathetic), 4) How much concern do you have for the person in the scenario? (1 is not concerned at all and 6 is extremely concerned), 5) How much anger do you feel toward the person in the scenario (1 is not angry at all and 6 is extremely angry), and 6) How much disappointment do you feel toward the person in the scenario? (1 is not disappointed at all and 6 is extremely disappointed). The stigma variables were selected based on our previous work on opioid addiction stigma (Goodyear & Chavanne, 2020; Goodyear et al., 2018). See Table 1 for further information on stigma items.

Table 1.

Descriptive means (Ms) and standard deviations (SDs) by condition (N = 1833).

| White-Male-Pills (n = 219) | White-Female-Pills (n = 199) | White-Male-Heroin (n = 240) | White-Female-Heroin (n = 242) | Black-Male-Pills (n = 240) | Black-Female-Pills (n = 229) | Black-Male-Heroin (n = 236) | Black-Female-Heroin (n = 228) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Item | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Responsible | 4.19 | 1.51 | 4.38 | 1.39 | 4.36 | 1.45 | 4.43 | 1.50 | 4.30 | 1.47 | 4.12 | 1.48 | 4.26 | 1.46 | 4.07 | 1.53 |

| Dangerous | 3.66 | 1.37 | 3.52 | 1.45 | 3.93 | 1.40 | 3.74 | 1.50 | 3.55 | 1.39 | 3.36 | 1.46 | 3.82 | 1.37 | 3.58 | 1.55 |

| Sympathy | 4.44 | 1.33 | 4.68 | 1.23 | 4.33 | 1.47 | 4.39 | 1.45 | 4.33 | 1.52 | 4.67 | 1.34 | 4.52 | 1.40 | 4.56 | 1.47 |

| Concern | 4.74 | 1.29 | 4.94 | 1.20 | 4.86 | 1.30 | 4.96 | 1.16 | 4.69 | 1.40 | 4.93 | 1.17 | 4.92 | 1.32 | 5.01 | 1.20 |

| Anger | 2.58 | 1.57 | 2.66 | 1.51 | 2.79 | 1.61 | 2.67 | 1.59 | 2.57 | 1.54 | 2.41 | 1.58 | 2.48 | 1.64 | 2.45 | 1.55 |

| Disappointment | 3.94 | 1.48 | 3.88 | 1.50 | 3.95 | 1.52 | 4.02 | 1.57 | 3.82 | 1.57 | 3.72 | 1.46 | 3.77 | 1.59 | 3.93 | 1.53 |

After completing the vignette questions, participants were asked their assumptions of the hypothetical individual’s level of income (a 200-point scale in thousands) and social class (poor, working class, middle class and rich). Lastly, participants were asked to answer self-report questions about their own sociodemographic characteristics, opioid use history, familiarity with addiction (i.e., knowing someone with an opioid addiction) and their perception of addiction controllability (a 100-point scale ranging from a belief that someone has no control over an addiction to a belief that someone has full control) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive and inferential statistics on sociodemographic characteristics

| Measure | N (%) | M ± SD | Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | 41.28 ± 13.25 | F(7, 1833) = 0.83 | .567 | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | χ2 (7) = 4.36 | .737 | ||

| Male | 930 (50.5) | |||

| Female | 903 (49.0) | |||

|

| ||||

| Gender identity | χ2 (14) = 11.39 | .655 | ||

| Male | 926 (50.2) | |||

| Female | 881 (47.8) | |||

| Other | 26 (1.41) | |||

|

| ||||

| Race | χ2 (21) = 21.31 | .440 | ||

| Black/African American | 181 (9.8) | |||

| White | 1397 (75.8) | |||

| Asian | 162 (8.8) | |||

| Other1 | 93 (0.9) | |||

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | χ2 (7) = 3.49 | .836 | ||

| Not of Hispanic/Latino origin | 1654 (89.7) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 179 (9.7) | |||

|

| ||||

| Income ($) | χ2 (42) = 37.88 | .652 | ||

| Less than 12,000 | 78 (4.2) | |||

| 12,001-30,000 | 244 (13.2) | |||

| 30,001-45,000 | 274 (14.9) | |||

| 45,001-60,000 | 357 (19.4) | |||

| 60,001-75,000 | 249 (13.5) | |||

| 75,001-100,000 | 302 (16.4) | |||

| 100,000 or more | 329 (17.9) | |||

|

| ||||

| Education | χ2 (35) = 39.96 | .259 | ||

| No schooling | 11 (0.6) | |||

| High school graduate | 153 (8.3) | |||

| Some college | 249 (13.5) | |||

| Professional training/license | 208 (11.3) | |||

| College graduate | 821 (44.6) | |||

| Graduate degree | 391 (21.2) | |||

|

| ||||

| Familiarity2 | χ2 (7) = 4.95 | .666 | ||

| Yes | 727 (39.5) | |||

| No | 1106 (60.0) | |||

|

| ||||

| Current/past opioid use | χ2 (7) = 9.04 | 0.250 | ||

| Yes | 345 (18.7) | |||

| No | 1488 (80.7) | |||

|

| ||||

| Control3 | 49.92 ± 27.0 | F(7, 1833) = 1.63 | .124 | |

Due to low cell counts, the following races were combined: Native American or Alaska Native, Hawaiian Native or Pacific Islander, other race, unknown race and multiracial

Knowing someone with an opioid addiction

Belief that someone has control over their addiction

M = mean

SD = standard deviation

Statistical analysis

To assess any differences across conditions, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square (χ2) analyses were conducted for continuous and binary sociodemographic characteristics and other measures (see Table 1). Similar to our past work (Goodyear & Chavanne, 2020; Goodyear et al., 2018), a principal component factor analysis using parallel analysis (O’connor, 2000) with oblique rotation was conducted on four stigma items that measured affect towards the hypothetical individual (concern, sympathy, anger and disappointment). Two components were found and scores for anger and disappointment were combined for a measure of negative affect with an eigenvalue of 1.748 (43.69% of the variance) and concern and sympathy were combined for a measure of positive affect with an eigenvalue of 1.358 (33.96% of the variance). A 2 (target race) x 2 (target gender) x 2 (end point) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was implemented with the stigma responses (responsibility (range: 1-6), dangerousness (range: 1-6), positive affect (range: 2-12) and negative affect (range: 2-12)) as dependent variables.

We conducted several exploratory analyses to probe additional factors that may have contributed to participants’ responses. In addition to understanding the effects of our treatment conditions on stigmatizing attitudes, we first aimed to assess how a participant’s race may have contributed to responses about the hypothetical individual’s race. All other races included the Asian and Other categories specified in Table 2. We conducted independent samples t-tests sorted by participant race [White, Black, non-Black (all other races and White participants) and non-White (all other races and Black participants)] and by condition (Target Race: White and Black) to compare differences across the stigma outcomes. We aimed to see if there was an effect in other races in our sample (e.g., Asian participants) and created non-Black and non-White categories due to sample size restrictions. Lastly, to assess the participants’ assumptions of the hypothetical individual’s income and class we conducted a three-way ANOVA with income as the outcome variable. Since perceived class was selected among the categories of poor, working class, middle class or wealthy, we used an ordered logistic regression with social class as the outcome variable. Data analysis was conducted with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 26.0 (SPSS 26.0, IBM Corp.) and with alpha set to p < .05.

Results

Participant characteristics

The sample (49% female) was mostly White (75.8%), college graduates (44.6%) and not of Hispanic or Latino origin (89.7%), however, the inferential statistics on the sociodemographic characteristics and other measures collected showed no differences across conditions (Table 1). Our sample was slightly less heterogenous than the U.S. population (e.g., 60.1% White race alone, 18.5% Hispanic or Latino origin) (Bureau, 2022). Almost 40% of the sample knew someone with an opioid addiction and 18.7% of participants had current or past opioid use. Participants’ beliefs about control over an addiction was at average of 49.9 (standard deviation SD: 27.0) on a scale from 1 to 100.

Stigma Results

All stigma items were correlated (r range: −.05 to .47, p < .05) except for disappointment and concern (r = .04, p = .12). The final stigma dependent variables, responsibility, dangerousness, positive affect and negative affect were also all correlated (r range: −.13 to .49, p < .001). Table 1 provides means and SDs for each stigma item broken down by condition.

Target race: Black versus White

Our results demonstrated that there was overall main effect of target race for responsibility (F(1, 1832) = 4.70, p = .030, partial η2 = .003), dangerousness (F(1, 1832) = 3.91, p = .048, partial η2 = .002) and negative affect (F(1, 1832) = 6.90, p < .01, partial η2 = .004), demonstrating that the individual framed as a White individual had higher stigma ratings compared to a Black individual (Figure 1a). In addition, there was an interaction effect of target race × gender for responsibility (F(1, 1832) = 5.24, p = .022, partial η2 = .003). Post hoc analysis showed that a White female was rated with higher responsibility than a Black female (t(896) = −3.15, p < .005, Cohen’s d = .21) and a Black male was rated with higher responsibility than a Black female (t(931) = −1.96, p = .05, Cohen’s d = .26) (Figure 1b). No significant main effect of positive affect or any other interaction effects were found (all p’s > .05)

Figure 1.

a. Race Condition. Participants rated the White individual with higher responsibility (p = .030, partial η2 = .003), dangerousness (p = .048, partial η2 = .002) and negative affect (p < .01, partial η2 = .004) compared to a Black individual. b. The interaction effect showed that a White female was rated with higher responsibility than a Black female (p < .005, Cohen’s d = .21) and a Black male was rated with higher responsibility than a Black female (p = .05, Cohen’s d = .26). Item ranges: responsibility (1-6), dangerousness (1-6) and negative affect (2-12). ** p < .005, * p = .05, error bars represent standard errors.

Target gender: male versus female

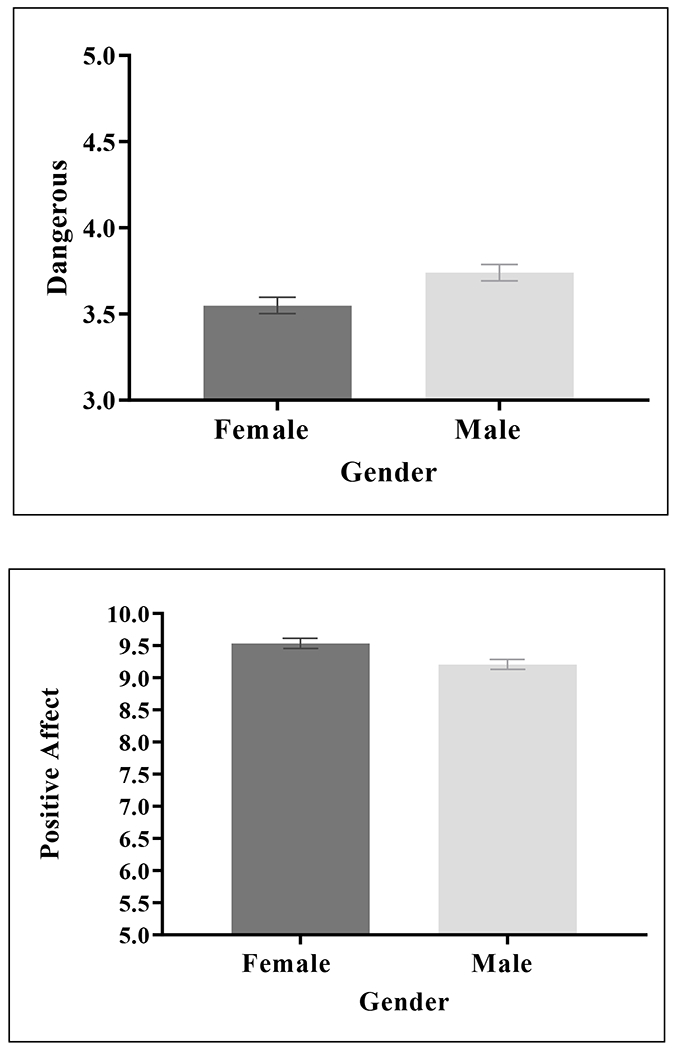

We also found a significant main effect of target gender for dangerousness (F(1, 1832) = 7.98, p < .005, partial η2 = .004) and positive affect (F(1, 1832) = 8.88, p < .005, partial η2 = .005), illustrating that the individual framed as a male was rated with higher dangerousness and lower positive affect. No significant main effects of responsibility and negative affect or any other interaction were found (all p’s > .05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Gender Condition.

Participants rated the male with higher dangerousness (p < .005,partial η2 = .004) and lower positive affect (p < .005, partial η2 = .005) compared to the female. Item ranges: dangerousness (1-6) and positive affect (2-12), error bars represent standard errors.

End point: heroin versus pills

Lastly, our results showed a significant main effect of end point for dangerousness (F(1, 1832) = 5.24, p = .022, partial η2 = .007), demonstrating that the individual who transitioned to heroin was rated with higher dangerousness than the individual who continued using painkillers. No other main effects of responsibility, negative affect and positive affect or interaction effects were found (all p’s > .05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. End Point Condition.

Participants rated the individual who transitioned to heroin with higher dangerousness than the individual who continued using painkillers (p = .022, partial η2 = .007). Item range: dangerousness (1-6), error bars represent standard errors.

Exploratory Results

Our first set of exploratory results based on participant race first showed that White participants rated the White individual with higher responsibility (t(1395) = −2.90, p < .005, Cohen’s d = .16), dangerousness (t(1395) = −2.47, p = .014, Cohen’s d = .13), and negative affect (t(1395) = −3.81, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .20) compared to ratings for the Black individual. Black participants rated the White individual with lower responsibility (t(179) = 2.58, p = .01, Cohen’s d = .39) compared to ratings for the Black individual. The results remained the same when replacing White participants with non-Black participants (all other races and White). No significant findings were found for non-White participants (all other races and Black) (all p’s > .05).

Our next set of exploratory results based on the race of the hypothetical individual (target race: White and Black) first showed that the hypothetical White individual was rated with higher responsibility by White participants compared to non-White participants (t(898) = −3.00, p < .005, Cohen’s d = .24). The results remained the same, with a slightly higher effect size when replacing White participants with non-Black participants (t(898) = 3.67, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .45). Next, White participants compared to non-White participants rated the hypothetical Black individual with lower dangerousness (t(931) = 2.86, p < .005, Cohen’s d = .22) and negative affect (t(931) = 4.08, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .31); Black participants compared to non-Black participants rated the hypothetical Black individual with higher dangerousness (t(931) = −4.17, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .43) and negative affect (t(931) = −4.39, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .45).

Our findings on participants’ assumptions of the hypothetical individual’s income showed that there was a main effect of target race (F(1, 1832) = 21.20, p < .001, partial η2 = .011), indicating that participants believed that the White individual had a higher income than the Black individual. We also found an interaction effect of target gender × end point (F(1, 1832) = 7.20, p < .01, partial η2 = .004). Post hoc analysis showed that in the heroin condition, participants believed that the male had a higher income than the female (t(944) = −2.40, p = .017, Cohen’s d = .16) and that the female in the pill condition had a higher income than in the female in the heroin condition (t(896) = 2.61, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .17). There were no other significant main or interaction effects (all p’s > .05). Lastly, our results on assumptions of the hypothetical individual’s class demonstrated an effect of race and endpoint, as participants believed that the Black individual had a lower social class compared to the White individual (β = −.70, p < .001) and the individual continuing to use pills had a higher social class compared to the individual who transitioned to heroin (β = .28, p = .001). No effect of gender was found (all p’s > .05).

Discussion

In the changing landscape of the opioid crisis, the current study aimed to expand on the limited past research on how race and other identities contribute to stigmatization of an opioid addiction. In light of the racialized history of the crack epidemic, where crack was coded as a “Black” problem (Hartman & Golub, 1999), and the shift of more Black individuals to using opioids (James & Jordan, 2018; Patel et al., 2021), we first theorized that an individual framed as Black would be stigmatized more than a White individual given the multitude of evidence showing negative racial biases towards minority individuals. However, our results demonstrated that a White individual was rated with higher responsibility, dangerousness and negative affect, which may be attributed to the fact that the opioid epidemic has been coded predominantly as a “White” problem and coincides with the prototype of a person who has historically used opioids. In addition, racial attitudes may have shifted during antiracist social movements like Black Lives Matter, which could have created less “pro-White” preferences (Sawyer & Gampa, 2018). Although we expected a different direction for our effects, these findings are in line with a previous study that found expressed higher stigma (negative stereotypes, negative feelings, desire for social distance and acceptability of discrimination) towards an individual framed as White compared to Black (Wood & Elliott, 2020). Wood and Elliott (2020) postulate that the findings could be attributed to a “black sheep effect” where members of one’s own group treat a person more harshly than outgroup members to preserve their social identity (Marques et al., 1988) or to avoid the appearance of racial prejudice (Bamberg & Verkuyten, 2021; Plant & Devine, 1998). Our exploratory results support these notions in part; the White respondents rated the White individual with higher stigma, but the Black respondents rated the White individual with lower stigma. However, the fact that all respondents judged their own “in-group” more harshly than the “outgroup” does not support in-group favoritism or in-group–out-group bias (Chen & Li, 2009; Lickel et al., 2000), which is a typical bias associated with favoring one’s own in-group over an out-group. Further testing on explicit measures that directly measure in-group and out-group tendencies are warranted given the preliminary and exploratory nature of these results. In addition, investigating other substances like crack versus pills could help to further discern the history on the crack epidemic, which was racialized as more of a “Black problem”.

In addition to the main effect of target race, we also saw an interaction of target race and target gender. The results first indicated that a White female was rated with higher responsibility than a Black female and this finding provides a further perspective of how multiple identities can contribute to stigma associated with an opioid addiction. Given the limitations of our sample size, we could not explore the interaction effect by respondent race or gender. However, as indicated earlier, respondents may have felt inclined to avoid appearing prejudiced towards the Black female. Our results also showed that a Black male was rated with higher responsibility than a Black female. While very little is known about how the public perceives Black males and females with opioid addictions, a qualitative study demonstrated that Black male participants believed their substance use problems were viewed more negatively than non-minority individuals, which could perpetuate health disparities (Scott & Wahl, 2011). The scarcity of research on this topic points to a need for future studies to investigate intersectional differences in judgments of Black individuals who have opioid addictions.

The findings from the current study coincide with our previous findings on gender (Goodyear et al., 2018) and end point (pills versus heroin) (Goodyear & Chavanne, 2020). We demonstrated that an individual framed as a male was rated with higher dangerousness and lower positive affect compared to individual framed as a female. Other studies of similar nature showed little to no effects of gender (Kulesza et al., 2016; Wood & Elliott, 2020); nonetheless, the findings of the current study substantiate that information pertaining to gender/sex of the individual creates stigmatizing attitudes. The differences across studies could be attributed to the fact that our vignette did not include the age or names of the hypothetical individuals, which can potentially create separate and additional biases (Newman et al., 2018). Lastly, our results indicated that an individual who transitioned to heroin was rated with higher dangerousness compared to individual who continued using pills, which is in line with our previous findings on end point (Goodyear & Chavanne, 2020). To our knowledge, no other groups have investigated the comparison of heroin and pills, and future studies are needed to validate our findings and to further examine intersectional components that may contribute to stigmatizing attitudes.

Lastly, our exploratory analysis on participants’ assumptions of the hypothetical individual’s income and class illustrated that participants believed that the White individual had a higher income than the Black individual, the male had a higher income than the female, the female in the pill condition had a higher income than in the female in the heroin condition, the Black individual had a lower social class compared to a White individual and the individual continuing to use pills had higher social class compared to the individual who transitioned to heroin. A previous study did not find any differences when comparing hypothetical White and Black individuals, but did find that a White working-class individual was rated with more acceptability of discrimination than a White middle-class individual (Wood & Elliott, 2020). While these findings do not directly align with our results due to differences across study conditions and participant populations, this does point to a need for further exploration on the topic.

Although our study extends on past research on opioid-addiction stigma, our study does have a few limitations. First, our sample had relatively low heterogeneity in terms of race, which decreased our ability to conduct some of our analyses. As a result, the analysis became exploratory in nature and reduced the generalizability of our findings. While we examined additional factors (e.g., participant race) that may have affected responses, we cannot conclude with certainty that those characteristics are solely what drove our results. The race effect could be a product of how we asked people to judge the individual in the vignette, which could potentially change if we had a description of groups of individuals. Therefore, future studies should include different types of hypothetical scenarios such as groups and examine potential mediators and moderators (e.g. class) that may affect participant responses and to help refine the selected stigma items. Lastly, we found small partial η2 effect sizes and small to medium Cohen’s d effect sizes, which should be considered carefully when interpreting our results. All of our stigma results were small effect sizes. We found the largest effect for Black respondents who rated the White individual with lower stigma, but it was still a medium effect size. Future studies should consider alternative methods for measuring stigma, as well as more salient stimuli that vary race within a vignette, which may generate larger effects.

In conclusion, this study aimed to expand on the limited past research investigating the relationship between race and other identities and how these associations drive public stigma towards an individual with an opioid addiction. Our study results further validate past research that has shown that race, gender and opioid use history can impact stigmatizing attitudes. Given the complexity of stigma, comprehending the interactions between multiple identities can help to deepen our knowledge of how the public views individuals with an opioid addiction. This understanding can provide important information on ways to destigmatize individuals with an opioid addiction and provide ways to break down treatment barriers. This study provides evidence that a Black individual was rated with lower stigma and, while this a step towards progress, further scrutiny of how minority individuals are perceived in the wake of increasing opioid use and overdoses is warranted. The facilitation of treatment access and quality care for minority individuals, who are differentially impacted by opioid addictions, is of high priority given the health and racial disparities that many communities have and are facing. The study results can be used to inform future work to help reduce health inequities for individuals who are disproportionally affected by the opioid epidemic.

Funding

This study was funded by the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University, Research Enhancement Action Fund (GR200022; PI: Goodyear). Dr. Goodyear is supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K01 AA026874). Dr. Ahluwalia is supported in part by a NIH funded Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE - P20GM130414).

References

- Bamberg K, & Verkuyten M (2021). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice: a person-centered approach. The Journal of Social Psychology, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. 10.2105/ajph.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, U. S. C (2022). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

- Chen Y, & Li SX (2009). Group identity and social preferences. American Economic Review, 99(1), 431–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D (2017). Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: A rapidly changing risk environment. International Journal of Drug Policy, 46, 107–111. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, & Steele C (1998). Social stigma. The handbook of social psychology., Vols. 1–2, 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Drake J, Charles C, Bourgeois JW, Daniel ES, & Kwende M (2020). Exploring the impact of the opioid epidemic in Black and Hispanic communities in the United States. Drug Science, Policy and Law, 6, 2050324520940428. 10.1177/2050324520940428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear K, & Chavanne D (2020). Stigma and policy preference toward individuals who transition from prescription opioids to heroin Accepted for publication: Addictive Behaviors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear K, Haass-Koffler CL, & Chavanne D (2018). Opioid use and stigma: The role of gender, language and precipitating events. Drug Alcohol Depend, 185, 339–346. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CA (2006). Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Research & Health, 29(1), 55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman DM, & Golub A (1999). The social construction of the crack epidemic in the print media. J Psychoactive Drugs, 31(4), 423–433. 10.1080/02791072.1999.10471772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James K, & Jordan A (2018). The Opioid Crisis in Black Communities. J Law Med Ethics, 46(2), 404–421. 10.1177/1073110518782949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM (2013). Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 2002-2004 and 2008-2010. Drug Alcohol Depend, 132(1-2), 95–100. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, Matsuda M, Ramirez JJ, Werntz AJ, Teachman BA, & Lindgren KP (2016). Towards greater understanding of addiction stigma: Intersectionality with race/ethnicity and gender. Drug Alcohol Depend, 169(Supplement C), 85–91. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, & Maust DT (2019). Buprenorphine Treatment Divide by Race/Ethnicity and Payment. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(9), 979–981. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickel B, Hamilton DL, Wieczorkowska G, Lewis A, Sherman SJ, & Uhles AN (2000). Varieties of groups and the perception of group entitativity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(2), 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques JM, Yzerbyt VY, & Leyens JP (1988). The “black sheep effect”: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European journal of social psychology, 18(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Ponicki W, Smith N, Rivera-Aguirre A, Davis CS, Fink DS, … Cerdá M (2019). Prescription drug monitoring programs operational characteristics and fatal heroin poisoning. International Journal of Drug Policy, 74, 174–180. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH, Byun E, & Gallagher RM (2012). Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med, 13(2), 150–174. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LS, Tan M, Caldwell TL, Duff KJ, & Winer ES (2018). Name Norms: A Guide to Casting Your Next Experiment. Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 44(10), 1435–1448. 10.1177/0146167218769858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’connor BP (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers, 32(3), 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva EM, Bowe T, Manhapra A, Kertesz S, Hah JM, Henderson P, … Trafton JA (2020). Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: observational evaluation. BMJ, 368, m283. 10.1136/bmj.m283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel I, Walter LA, & Li L (2021). Opioid overdose crises during the COVID-19 pandemic: implication of health disparities. Harm Reduct J, 18(1), 89. 10.1186/s12954-021-00534-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant EA, & Devine PG (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of personality and social psychology, 75(3), 811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond ML, Smith S, & Collins TC (2020). Exploring African‐American womens’ experiences with substance use treatment: A review of the literature. Journal of community psychology, 48(2), 337–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer J, & Gampa A (2018). Implicit and Explicit Racial Attitudes Changed During Black Lives Matter. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(7), 1039–1059. 10.1177/0146167218757454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MC, & Wahl OF (2011). Substance abuse stigma and discrimination among African American male substance users. Stigma research and action, 1(1), 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer M, Warner M, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, & Hedegaard H (2019). Drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl, 2011–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks C, & Stenstrom DM (2020). Stigmatization of opioid addiction based on prescription, sex and age. Addict Behav, 108, 106469. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, & Elliott M (2020). Opioid Addiction Stigma: The Intersection of Race, Social Class, and Gender. Subst Use Misuse, 55(5), 818–827. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1703750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]