Abstract

N.BstNBI is a nicking endonuclease that recognizes the sequence GAGTC and nicks one DNA strand specifically. The Type IIs endonuclease, MlyI, also recognizes GAGTC, but cleaves both DNA strands. Sequence comparisons revealed significant similarities between N.BstNBI and MlyI. Previous studies showed that MlyI dimerizes in the presence of a cognate DNA, whereas N.BstNBI remains a monomer. This suggests that dimerization may be required for double-stranded cleavage. To test this hypothesis, we used a multiple alignment to design mutations to disrupt the dimerization function of MlyI. When Tyr491 and Lys494 were both changed to alanine, the mutated endonuclease, N.MlyI, no longer formed a dimer and cleaved only one DNA strand specifically. Thus, we have shown that changing the oligomerization state of an enzyme changes its enzymatic function. This experiment also established a protocol that could be applied to other Type IIs endonucleases in order to generate more novel nicking endonucleases.

INTRODUCTION

Few nucleases break just one strand of DNA thereby introducing a nick into DNA. Most such proteins are involved in DNA replication, DNA repair and other DNA-related metabolisms [e.g. gpII (Higashitani et al., 1994) and MutH (Modrich, 1989)], and cannot easily be used to manipulate DNA. Indeed they usually recognize long sequences and associate with other proteins to form active complexes that are difficult to manufacture. None of these nicking enzymes is commercially available. Recently two nicking enzymes with unprecedented features were isolated from the thermophilic bacteria Bacillus stearothermophilus: N.BstSEI (Abdurashitov et al., 1996) and its isoschizomer N.BstNBI (Morgan et al., 2000). They differ from typical restriction enzymes in that they cleave only the top DNA strand (as the site is conventionally represented), which contains the sequence 5′-GAGTC-3′, four bases downstream from that sequence. These nicking enzymes can be used to introduce nicks and gaps into DNA substrates and thus are useful for studying mismatch repair (Wang and Hays, 2000). A more general potential application is in strand displacement amplification (SDA), which is a fast, isothermal DNA amplification technology (Walker et al., 1992; Walker, 1993). SDA is being used as a diagnostic method for detecting infectious agents, such as Chlamydia trachomatis (Spears et al., 1997). Currently SDA reactions require incorporation of α-thio-deoxynucleotides (dNTPαS) into the DNA, to prevent cleavage on one DNA strand. A restriction endonuclease will only cleave the unmodified strand in the primer region, producing a nick. This nick is then extended by a DNA polymerase, which displaces the parental DNA strand. Use of nicking enzymes could potentially eliminate the need for dNTPαS, increase the flexibility of the protocol, as well as lowering the cost and increasing the efficiency of SDA reactions.

It would be helpful if there were other nicking endonucleases available. The rarity of reported nicking enzymes might reflect their limited natural occurrence or the difficulty in unambiguously detecting their nicking activity. An alternative source of nicking endonucleases might be the engineering of existing restriction endonucleases. Interestingly, previous investigations suggested that N.BstNBI is a naturally mutated Type IIs endonuclease (Higgins et al., 2001). To assess whether Type IIs enzymes can be engineered into nicking endonucleases, we have chosen the Type IIs endonuclease MlyI as a model for conversion because MlyI shares several similar features with the naturally existing nicking enzyme N.BstNBI. Both enzymes recognize the same DNA sequence, 5′-GAGTC-3′, and share significant sequence similarity (Higgins et al., 2001). In this paper we demonstrated the feasibility of converting a Type IIs endonuclease into a strand-specific nicking enzyme by changing its oligomerization state using PCR-mediated mutagenesis.

RESULTS

Disrupting the dimerization interface of MlyI

Previous gel filtration results showed that MlyI and N.BstNBI are both monomers in solution and that MlyI apparently dimerizes in the presence of specific DNA, whereas N.BstNBI remains as a monomer (Higgins et al., 2001). This suggests that mutations may have disrupted the N.BstNBI dimerization interface, altering its double-stranded cleavage activity into a nicking activity. Therefore, if the dimerization function of a Type IIs restriction enzyme could be abolished by mutation, it might become a nicking enzyme. To engineer MlyI into a nicking endonuclease, the first step was to search for the potential dimerization interface of MlyI.

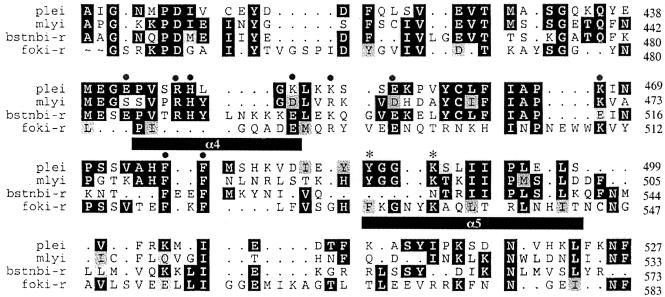

FokI crystallization studies showed that FokI dimerization is mediated primarily through helix α4 and possibly parallel helix α5 of the cleavage domain, located <10 amino acid residues away from its catalytic site PD–DTK (Wah, 1998). The amino acid sequences of the C-terminal half of PleI, MlyI, N.BstNBI and FokI endonucleases were aligned using the programs Pileup and Prettybox (Figure 1). The computer alignment of the last 200 amino acid residues of PleI, MlyI and FokI showed some clusters of conserved residues. Some charged residues, which seemed to be in a region corresponding to the FokI dimerization domain, were changed in MlyI (S446A, R450A, H451A, D454A, R457A, D460A, K471A, K471E, P473K, S436K and F480A/F481A). None of these mutations abolished the double-stranded DNA cleavage activity of MlyI, suggesting that none of these residues is essential for DNA cleavage or dimerization.

Fig. 1. Multiple sequence alignment of the C-terminal domains of PleI, MlyI, N.BstNBI and FokI. Identical residues are shown as white on black, and conservative replacements are black on gray. Dots represent gaps introduced to improve the alignment. Filled circles indicate the residues that were changed to alanine by mutagenesis. Motif YGGK is conserved in PleI and MlyI but absent in N.BstNBI. In FokI this pattern seemed to be reversed as KGNY. Both tyrosine (Tyr491) and lysine (Lys494) were changed to alanine in MlyI and are indicated by stars. The α4 and α5 helices of FokI dimerization interface are drawn under the FokI amino acid sequence. Pileup and Prettybox programs were used with a gap creation penalty of 3 and gap extension penalty of 1.

A closer look at the residues conserved in PleI, MlyI and FokI, but not in N.BstNBI, suggested a new potential mutagenesis target. We focused on a short region (four amino acids) that seems to be missing in N.BstNBI, but is present in PleI, MlyI and FokI (Figure 1). The conserved residues of this region were a tyrosine, a lysine and a glycine. In MlyI and in PleI the conserved pattern was YGGK. Both Tyr491 and Lys494 in MlyI were changed to alanine. Preliminary activity assays using crude cell extracts containing the mutated MlyI showed specific DNA nicking activity and MlyI-Y491A/K494A was renamed N.MlyI.

N.MlyI is a specific nicking endonuclease with high specific activity

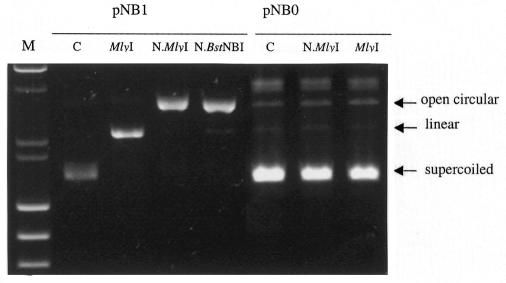

N.MlyI was purified to >95% homogeneity (see Methods). The purified N.MlyI was tested with λ DNA. No double-stranded DNA cleavage was detected. The nicking activity of N.MlyI was further examined using plasmid DNAs. The supercoiled form of an undigested plasmid can be converted into a nicked open circular form when one strand is cleaved by a nicking endonuclease, or into a linear form when both strands are cleaved in proximity by a restriction enzyme. When plasmid pNB1 containing one MlyI recognition site was used in the digestion assay, pNB1 was converted into a nicked open circular form by N.MlyI and the nicking enzyme N.BstNBI, and into linear form by wild-type MlyI (Figure 2). When plasmid pNB0 containing no MlyI site was used in the same assay, pNB0 remained in the supercoiled form following the digestions (Figure 2). This result suggested that the nicking activity of N.MlyI was sequence specific. N.MlyI activity was titrated using pNB1. One unit was defined as the amount of N.MlyI needed to achieve complete nicking of 1 µg of pNB1 in 1 h at 37°C. The specific activity of the mutated MlyI was ∼400 000 units per mg of protein, which is very similar to that of wild-type MlyI.

Fig. 2. Specific nicking activity of N.MlyI. Agarose gel electrophoresis showing plasmid pNB1 undigested (C, control), or digested by MlyI, N.MlyI or N.BstNBI. Plasmid pNB0 was also used as a specificity control either undigested (C), or digested by N.MlyI or MlyI. M, molecular weight marker (λ DNA/HindIII and φX174/HaeIII).

Mapping the nicking site of N.MlyI

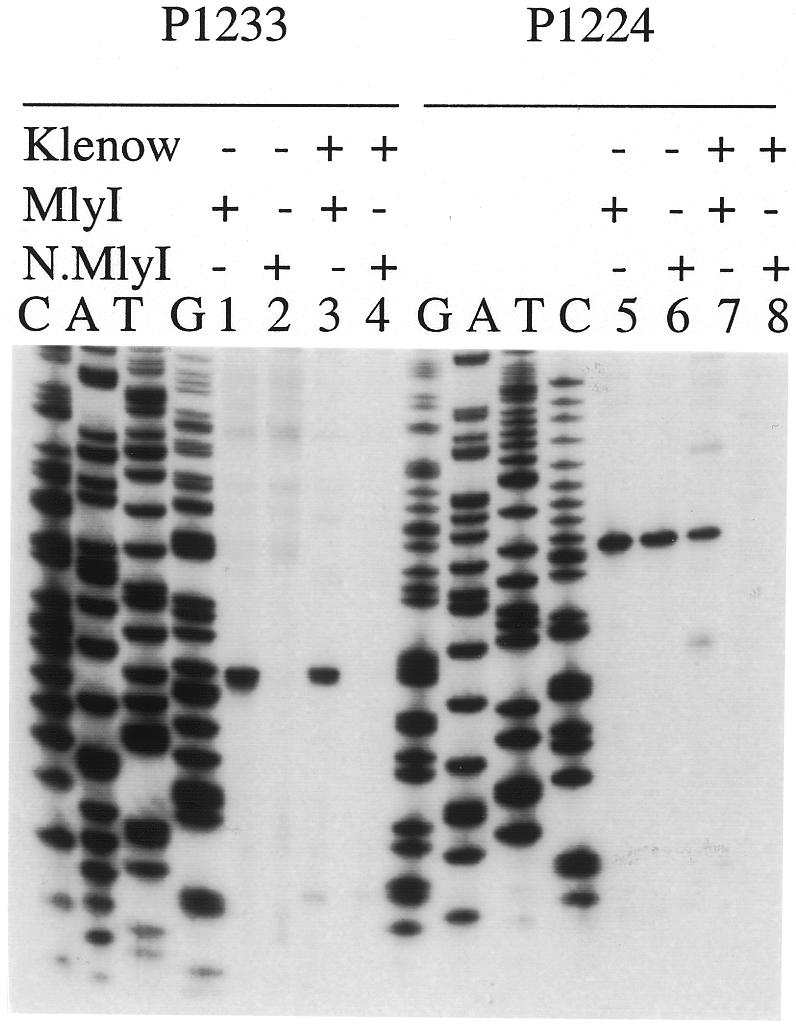

The nicking site of N.MlyI was precisely determined by comparing dideoxy sequencing ladders with polymerized extension products digested with the engineered N.MlyI as well as with wild-type MlyI (Figure 3). Plasmid pUC19 was used as a template, with two primers: forward primer 1224 (for the top strand) and reverse primer 1233 (for the bottom strand). Wild-type MlyI cleaved the bottom strand five bases away from the recognition sequence (Figure 3, lane 1), but N.MlyI did not cleave at all (Figure 3, lane 2). In contrast, N.MlyI cleaves the top DNA strand five bases away from the recognition sequence, as in wild-type MlyI (Figure 3, lanes 5 and 6). When the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I was added to the digested products, no further extension was detected for the MlyI-cleaved fragment, showing that MlyI cleavage generates blunt-ended fragments (Figure 3, lanes 3 and 7). However, in the case of N.MlyI the top strand was extended from the nick to a much larger sized band (Figure 3, lane 8 beyond the display window) as is observed in nick translations. All these results suggested that N.MlyI is an active nicking endonuclease, which cleaves only the DNA strand containing the sequence 5′-GAGTC-3′.

Fig. 3. Determination of the cleavage sites of N.MlyI. Plasmid pUC19, which contains a GAGTC recognition sequence and two synthetic primers, was used in sequencing reactions based upon the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method. Additional extension reactions were carried out with the same plasmid and primer in the presence of four deoxynucleotides and [33P]dATP. The labeled substrate was then digested with MlyI or the engineered N.MlyI. After the digestion, the reaction mixture was divided into two aliquots: one was mixed with stop solution immediately (lane: Klenow – ); the other was treated with Klenow fragment at room temperature for 10 min and then mixed with stop solution (lane: Klenow +). The cleavage reaction products were then separated on an 8% denatured polyacrylamide gel along with standard A, C, G and T ladders, and detected by autoradiography.

N.MlyI remains a monomer in the presence of cognate DNA

We have converted the Type IIs endonuclease MlyI into a strand-specific nicking endonuclease N.MlyI by introducing mutations in the putative dimerization interface. To obtain direct evidence that the Y491A/K494A mutation disrupted the dimerization of MlyI, gel filtration experiments were performed to measure the molecular mass of N.MlyI in solution with wild-type MlyI and N.BstNBI as controls.

Previous gel filtration data showed that MlyI dimerizes in the presence of DNA containing its recognition sequence and a divalent cation (Higgins et al., 2001). Under these conditions, a stable MlyI–DNA complex was formed with an apparent molecular mass of 158.4 kDa (Figure 4), which is consistent with a complex containing two molecules of MlyI plus two DNA duplexes [(2 × 63 865) + (2 × 17 476) =162 682]. A similar gel filtration experiment was performed with N.MlyI (deduced molecular weight = 63 715) under the same conditions. The molecular mass of N.MlyI with specific DNA was 60 kDa based on the standard linear curve generated from molecular weight standards (Figure 4), suggesting that no dimers of N.MlyI were formed. In the case of N.BstNBI, the molecular mass of the N.BstNBI–DNA complex was measured as 99.4 kDa, which corresponds to a complex composed of one N.BstNBI molecule bound to one DNA molecule (70 769 + 17 476 = 88 245). An increase of molecular mass of N.BstNBI–DNA reflects the formation of one N.BstNBI plus one DNA complex (Figure 4). However, no such increase was observed with N.MlyI. Nevertheless, N.MlyI bound and shifted the specific DNA under the same conditions in DNA binding assays (not shown). One explanation is that the apparent molecular mass of the N.MlyI–DNA complex was basically unchanged because the protein might become more compact upon binding its specific substrate. A more likely explanation is that the association between the enzyme and the DNA is weak and the complex dissociates as it is diluted on the column.

Fig. 4. Gel filtration results. The Kav value for each protein standard (on the linear scale) was plotted against the corresponding molecular weight (on the logarithmic scale). Those standard proteins (ovalbumin, 43 kDa; albumin, 67 kDa; aldolase, 158 kDa; catalase, 232 kDa) are represented by unfilled squares. The Kav of the proteins of interest (black diamonds) were located on this calibration curve and the corresponding molecular weights were calculated using the calibration curve equation: Kav = –0.266 log(molecular weight) + 1.658.

DISCUSSION

Although most endonucleases cleave both DNA strands, only one has been reported to have two catalytic centers (Christ et al., 1999). To cleave two DNA strands with one catalytic center, the endonuclease either has to form a dimer or undergo major conformational changes between the two cleavage events. Most of the Type II and Type IIs restriction endonucleases catalyze double-stranded cleavage by forming dimers (Wilson and Murray, 1991). Some restriction endonucleases exist as monomers in solution, but form dimers in the presence of DNA and divalent metal ion, e.g. FokI (Vanamee et al., 2001), Sau3AI (Friedhoff et al., 2001) and MlyI (Higgins et al., 2001).

If the dimerization function of a restriction enzyme was eliminated by mutation, it might become a nicking enzyme. Pingoud and coworkers generated a nicking endonuclease from the Type II endonuclease EcoRV by combining a subunit with an inactive catalytic center with a subunit that had a defect in the DNA binding site. The mutated EcoRV is a heterodimer that only nicks DNA within the EcoRV recognition sequence (Stahl et al., 1996). However, since the recognition site is palindromic this type of heterodimer does not have strand-specific activity. Type IIs endonucleases recognize non-palindromic sequences. Thus, abolition of their dimerization function may convert them into strand-specific nicking endonucleases. When the dimerization function of the Type IIs endonuclease FokI was abolished by site-directed mutagenesis, the resulting monomeric FokI showed very low DNA nicking activity, probably due to the fact that FokI cleaves two DNA strands concertedly (Bitinaite et al., 1998).

In contrast, N.MlyI shows very high DNA nicking activity (∼400 000 units per mg of protein). This high specific activity not only eliminates suspicion that N.MlyI might be a near-dead MlyI variant, which was not active enough to perform double-stranded cleavage, but also sheds some light on the mechanism of the cleavage reaction catalyzed by Type IIs endonucleases. A previous study showed that MlyI cleaves DNA in two sequential steps: DNA is nicked on one strand and then the nicked DNA is further cleaved via dimerization of MlyI (Higgins et al., 2001). Results from this study are consistent with the two-step cleavage theory. Mutation in the YGGK motif of MlyI resulted in a monomeric N.MlyI, which can still catalyze the first step of the cleavage reaction but completely fails to catalyze the second cleavage step.

This mechanistic distinction between MlyI and FokI may be the reason why the monomeric N.MlyI is a much more active nicking enzyme than the monomeric FokI. Mutating the dimerization function of MlyI blocks only the second step reaction, which by hypothesis is mediated by dimerization; but lack of dimerization has little (if any) effect on the first-step DNA nicking reaction. In contrast, abolishing the FokI dimerization function may affect DNA cleavage on both DNA strands because the two cleavage steps are concerted and coupled.

In addition, N.MlyI specifically cleaves only the top strand containing its recognition sequence 5′-GAGTC-3′, as in N.BstNBI. Based on these results, we suggest that MlyI binds to its asymmetric recognition sequence 5′-GAGTC-3′ in an orientation enabling it to cleave only the top strand, with the bottom strand cleaved normally by a second MlyI molecule interacting with the first enzyme molecule.

In this study, we successfully demonstrated that a Type IIs endonuclease, such as MlyI, could be converted into a strand-specific nicking enzyme by changing its oligomerization state (from dimer to monomer). More generally, we have shown that changing the oligomerization state of an enzyme changes its enzymatic function. This study suggests that the Type IIs endonucleases, which generate nicking intermediates before complete digestion on both DNA strands, may be the preferred candidates for conversion. Our data also support the idea that N.BstNBI is a mutated Type IIs enzyme, whose dimerization function was probably limited by mutations. It would be interesting to test whether the double-stranded cleavage activity of N.BstNBI can be restored by protein engineering.

METHODS

Strains and plasmids. Escherichia coli strain ER2502 [fhuA2 ara-14 leu D(gpt-proA)62 lacY1 glnV44 galK2 rpsL20 endA1 R(zgb210::Tn10) Tet S xyl-5 mtl-1 D(mcrC-mrr) HB101] was obtained from E. Raleigh and M. Sibley (New England Biolabs). To express the gene encoding MlyI endonuclease (mlyIR) cloned into pUC19 without damaging the host DNA, a pSYX20 plasmid carrying the gene encoding N.BstNBI methylase was transformed into E. coli strain ER2502. The pNB0 and pNB1 plasmids contain zero or one N.BstNBI site, respectively. To construct those pNB0 and pNB1 plasmids, six or five N.BstNBI sites were, respectively, removed from Litmus28 plasmid by site-specific mutagenesis (Morgan et al., 2000).

Gel filtration. Gel filtration was performed on an Amersham Pharmacia Akta FPLC system using a Pharmacia Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column. The column was equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 7 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol. Protein elution was detected by recording the absorption at 280 nm. The linear standard curve was generated by using the calibration kits (low and high molecular weight) from Pharmacia. Four nanomoles of purified MlyI or N.MlyI were mixed with an excess of either non-specific or specific DNA duplexes, which were generated by annealing two complementary oligodeoxynucleotides (27mer) in a buffer containing 50 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM Tris–acetate pH 7.9, 10 mM calcium chloride, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The samples were incubated for 5 min at 37°C before being loaded onto the column. As controls the protein or the oligodeoxynucleotides were loaded alone. A similar experiment was carried out with N.BstNBI with a few changes: a buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT was used and the samples were incubated for 5 min at 55°C.

Construction of dimerization-deficient mutated MlyI. MlyI residues that were conserved among MlyI, PleI and FokI, and that aligned with residues thought to be important for FokI dimerization, were changed into alanine by PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis (Morrison and Desrosiers, 1993). Two residues, conserved among the three Type IIs restriction endonucleases but not found in N.BstNBI, were changed to alanine as well. The following forward mutagenic primer was used for changing both Tyr491 and Lys494 to alanine: 5′-ACATGCTGGTGGAGCAACAAAGATTATTCC-3′. The constructs were sequenced to confirm the mutations and to check that no additional mutations were introduced during PCR.

Expression and purification of N.MlyI. Escherichia coli ER2502 cells containing pUC19-mlyIR-Y491A/K494A (pUC19-N.MlyI) were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin. The cells were harvested by centrifugation. The following procedures were performed on ice or at 4°C. One hundred grams of cell pellet (wet weight) were resuspended in 327 ml of buffer A (20 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.9, 0.1 mM EDTA, 7 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol) supplemented to 50 mM NaCl, and broken with a Manton-Gaulin homogenizer. Sigma Protease Inhibitor solution (25 ml) was added after the first pass. The extract was centrifuged at 15 000 g for 40 min at 4°C. The supernatant was passed through a 392 ml Heparin HyperD AP5, an 80 ml (3.5 × 8.3 cm) Source-15Q Fineline 35, a 6 ml (1.6 × 3.0 cm) Source 15S and an 8 ml (1 × 11.3 cm) Heparin TSK5pw column. The purification steps were all performed using Pharmacia AKTA FPLC system. The activity assays were carried out on T7 DNA in order to detect specific nicking activity at MlyI sites (Morgan et al., 2000).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Lauren Higgins for valuable technical support. We thank Michael Dalton, Christine Sanderson and Andrew Gardner for assistance in protein purification, gel filtration and sequencing experiments. We thank Aneel Aggarwal for sharing unpublished FokI results. We would like to thank Richard Roberts and Elisabeth Raleigh for critical reading of this manuscript. We thank Donald Comb for his support. Part of this work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM60057 (to H.K.).

REFERENCES

- Abdurashitov M., Belitchenko, O., Shevchenko, A. and Degtyarev, S. (1996) N.BstSE—a site-specific nickase from Bacillus stearothermophilus SE-589. Mol. Biol. (Mosk.), 30, 1261–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitinaite J., Wah, D., Aggarwal, A. and Schildkraut, I. (1998) FokI dimerization is required for DNA cleavage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 10570–10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ F., Schoettler, S., Wende, W., Steuer, S., Pingoud, A. and Pingoud, V. (1999) The monomeric homing endonuclease PI-SceI has two catalytic centres for cleavage of the two strands of its DNA substrate. EMBO J., 18, 6908–6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedhoff P., Lurz, R., Luder, G. and Pingoud A. (2001) Sau3AI—a monomeric type II restriction endonuclease that dimerizes on the DNA and thereby induces DNA loops. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 23581–23588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashitani A., Greenstein, D., Hirokawa, H., Asano, S. and Horiuchi, K. (1994) Multiple DNA conformational changes induced by an initiator protein precede the nicking reaction in a rolling circle replication origin. J. Mol. Biol., 237, 388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins L., Besnier, C. and Kong, H. (2001) The nicking endonuclease N.BstNBI is closely related to type IIs restriction endonucleases MlyI and PleI. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 2492–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrich P. (1989) Methyl-directed DNA mismatch correction. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 6597–6600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R.D., Calvet, C., Demeter, M., Agra, R. and Kong, H. (2000) Characterization of the specific DNA nicking activity of restriction endonuclease N.BstNBI. Biol. Chem., 381, 1123–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison H. and Desrosiers, R. (1993) A PCR-based strategy for extensive mutagenesis of a target DNA sequence. Biotechniques, 14, 454–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears P., Linn, C., Woodard, D. and Walker, G. (1997) Simultaneous strand displacement amplification and fluorescence polarization detection of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA. Anal. Biochem., 247, 130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl F., Wende, W., Jeltsch, A. and Pingoud, A. (1996) Introduction of asymmetry in the naturally symmetric restriction endonuclease EcoRV to investigate intersubunit communication in the homodimeric protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 6175–6180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanamee E., Santagata, S. and Aggarwal, A. (2001) FokI requires two specific DNA sites for cleavage. J. Mol. Biol., 309, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wah D.A. (1998) Structure of FokI has implications for DNA cleavage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 10564–10569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker G.T. (1993) Empirical aspects of strand displacement amplification. PCR Methods Appl., 3, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker G.T., Fraiser, M.S., Schram, J.L., Little, M.C., Nadeau, J.G. and Malinowski, D.P. (1992) Strand displacement amplification—an isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 1691–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. and Hays, J. (2000) Preparation of DNA substrates for in vitro mismatch repair. Mol. Biotechnol., 15, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson G.G. and Murray, N.E. (1991) Restriction and modification systems. Annu. Rev. Genet., 25, 585–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]