Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible for high rates of pneumococcal bacteremia, meningitis, pneumonia, and acute otitis media worldwide. Protection from disease is conferred by antibodies specific for the polysaccharide (Ps) capsule of the bacteria. Of the four types of group 9 pneumococci, types 9N and 9V cause the most disease, and both types are included in the polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine. The type 9V capsule consists of repeating pentasaccharide units linearly arranged, with an average of 1 to 2 mol of O-acetate side chains per mol of repeat units, added in a complex pattern in which not all repeat units are alike. α-GlcA residues may be O-acetylated in the 2 (17%) or 3 (25%) position and β-ManNAc residues may be O-acetylated in the 4 (6%) or 6 (55%) position. Under certain conditions, the O-acetate side chains are subject to oxidation, which results in subsequent de-O-acetylation of a significant number of the repeat units. This de-O-acetylation could adversely affect the efficacy of a vaccine containing the 9V Ps. A study was undertaken to compare the relative contributions of O-acetate and Ps backbone epitopes in the immune response to S. pneumoniae 9V type-specific Ps. In both an infant rhesus monkey model and humans, antibodies against the non-O-acetylated 9V backbone as well as against O-acetylated 9V Ps were detected. Functional (opsonophagocytic) activity was observed in antisera in which the predominant species of antibody recognized de-O-acetylated 9V Ps. We concluded that the O-acetate side groups, while recognized, are not essential to the ability of the 9V Ps to induce functional antibody responses.

Streptococcus pneumoniae causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. High rates of pneumococcal meningitis, bacteremia, and pneumonia in children and the elderly are attributable to this pathogen. Elderly patients who develop bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia have a significant risk of mortality (approximately 40%) (15). Additionally, pneumococcal otitis media in children is a serious health problem. Protection from infection and disease caused by S. pneumoniae has been shown to be provided by antibodies specific to the pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides (Ps). In 1983, a vaccine containing 23 serotype-specific capsular Ps was licensed for use in adults and in children 4 years of age and older (6). This vaccine induces type-specific antipneumococcal antibodies (Ab) and has demonstrated efficacy against pneumococcal disease in adults (3, 6, 13). Recent analyses of randomized controlled trials have confirmed the efficacy of pneumococcal Ps vaccines, and in 1997 the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices extended its recommendations for use of this vaccine to include all persons aged 65 and over and persons aged 2 years and over who are at increased risk of pneumococcal disease (1, 7). Ps-protein conjugate vaccines consisting of type-specific pneumococcal Ps coupled to a variety of protein carriers have shown enhanced immunogenicity in children under two years of age (2, 11). Nasopharyngeal carriage of vaccine serotypes also can be reduced by use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in children (5). In addition, vaccination with conjugate prior to administration of the Ps vaccine was shown to increase type-specific pneumococcal Ab responses in high-risk adults, presumably as a result of immunologic priming (4). Thus, the full potential of pneumococcal vaccination is beginning to be realized.

One of the groups included in the 23-valent vaccine, group 9, contains four capsular types (9N, 9A, 9L, and 9V) which together account for 5.8% of all bacteremic infections and 3.7% of all meningeal pneumococcal infections. Of the four types, 9N and 9V cause the most group 9 disease (91% combined) (15). Both 9N and 9V are included in the polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine used in this study. The four group 9 Ps are linear repeating units of five monosaccharides which contain in their backbone structures d-glucose, N-acetylmannosamine, and glucuronic acid (9, 13). The glucuronic acid is an important epitope (15). In addition, type 9V contains O-acetate side chains, which also can be important epitopes (10, 14). The O-acetate groups are found on the α-GlcA, β-ManNAc, and the α-Glc residues in various proportions and positions (12). However, the O-acetate moiety has been found to be labile under conditions of neutral to alkaline pH or in the presence of phosphate anions (8). Loss of O-acetate may reduce the ability of 9V Ps to induce functional immune responses against 9V organisms in vivo. The functional epitopes of capsular Ps of pneumococci have not been clearly defined, and oxidation of important vaccine Ps residues could negatively affect the immunogenicity of a vaccine. Therefore, a series of studies was undertaken in infant rhesus monkeys and in humans to explore the relative contributions of O-acetate and Ps backbone epitopes to the immune response to S. pneumoniae 9V type-specific Ps. For both model systems investigated, it was concluded that the O-acetate side groups can contribute to recognition of pneumococcal Ps but are not essential to the ability of the 9V Ps to induce functional Ab responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccines.

The polyvalent pneumococcal Ps vaccine used in this study was PNEUMOVAX 23 (Merck), containing types 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F (Danish nomenclature). The Ps-protein conjugate vaccine used in this study was prepared as previously described (2, 16). Briefly, type-specific Ps were isolated from fermentations of S. pneumoniae by alcohol precipitation and, to improve handling, were reduced in molecular size to 350,000 to 600,000 Da before conjugation. The type-specific Ps was coupled to an outer membrane protein preparation obtained from Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B (strain B-11) by detergent extraction of intact cells. The conjugate vaccine was adsorbed to aluminum adjuvant at a concentration of 450 mg of Al3+/ml.

Infants.

Infants were enrolled in a study for investigation of a seven-valent Ps-outer membrane protein complex (OMPC) conjugate vaccine, containing types 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F (2). Healthy infants were selected. Infants received the vaccine at 2, 4, and 6 months of age with boosters at 12 months with an adult dose of polyvalent pneumococcal Ps vaccine. Sera were evaluated at 13 months for anti-9V Ab by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Those sera with ELISA titers of approximately 2 μg/ml or greater for which an adequate volume was available were randomly selected for further evaluation by radioimmunoassay (RIA) and opsonin assay. Evaluation by RIA and opsonin assay of preimmune sera was not performed due to the extremely low levels of Ab in most of these sera.

Adults.

Thirty adults were immunized with polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine under Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent. Serum samples were obtained prior to vaccination and 1 month postvaccination for evaluation by ELISA for anti-9V Ab. Sera with the highest ELISA titers (>6 μg/ml) were further evaluated by RIA and opsonin assay.

Animals.

Infant (2- to 3-month-old) rhesus monkeys of both sexes were provided by New Iberia Research Center, Division of the University of Southwestern Louisiana, New Iberia, and were housed with their mothers on site. Three groups of five infant rhesus monkeys were immunized intramuscularly with 0.5 μg of 9V Ps-OMPC conjugate vaccine (by Ps mass) on day 0 and day 28. Serum was collected on days 0 and 42 (0.5 to 1 ml) for analysis. Animal studies were performed in accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Deacetylated 9V Ps.

Pneumococcal 9V Ps was de-O-acetylated by treatment with 2.5 N NaOH. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) confirmed the removal of >99% of the O-acetate groups and also confirmed that the remainder of the Ps structure was intact. Some of the de-O-acetylated Ps was conjugated to N. meningitidis group B OMPC as previously described (16). The resulting conjugate was comparable in terms of Ps size, side chain loading, and Ps/protein ratio to the conjugates made with intact 9V Ps.

ELISA.

ELISAs were performed to measure immunoglobulin G (IgG) against the native, nonsized pneumococcal capsular Ps type 9V. The ELISA was performed as described previously (16).

RIA of anti-9V Ab.

Sera were assayed for Ab to 9V Ps by a Farr-type RIA with native, nonsized 14C-pneumococcal capsular Ps. The presence of O-acetate groups on the labeled 9V Ps was confirmed by its reactivity with O-acetate-specific rabbit antiserum (factor g) from Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark. Hyperimmune antipneumococcal rabbit antiserum (anti-group 9) was purchased from the New York State Department of Health at Albany to use as a standard (16). Due to the extremely small volume of serum available from the children and infant rhesus monkeys, the RIA utilized was a competitive inhibition assay performed by adding an equal volume of unlabeled Ps at 200 μg/ml to the 14C-labeled 9V Ps. Standard curves of individual sera were not used for quantitation because of the low level of Ab in most individuals. Therefore, the proportion of counts per minute (cpm) bound was used to estimate the relative amounts of Ab present with and without a competitor. The proportion of Ab that required O-acetate for recognition was estimated based on the difference in bound cpm in competition with unlabeled 9V Ps (containing both O-acetate and backbone epitopes) and with unlabeled 9A or de-O-acetylated 9V Ps (backbone epitopes only). Type 9A was used as a competitor in the assay since its carbohydrate structure is similar to that of 9V but lacks the O-acetate groups (12). Thus, 9A represents a naturally non-O-acetylated 9V-like structure and therefore would not be affected by the reagents used to chemically de-O-acetylate type 9V Ps. Additionally, chemically de-O-acetylated 9V Ps was utilized to compensate for any differences in heterogeneity or polydispersity between the 9A and 9V preparations. The percentage of O-acetate-specific Ab was calculated with a correction for the cpm bound when native 9V Ps was used as the competitor, as follows: 100 × (cpm bound in the presence of inhibitor Ps − cpm bound in the presence of 9V Ps)/(cpm bound with no inhibitor − cpm bound in the presence of 9V Ps). For example, if the number of cpm bound in the presence of excess unlabeled 9A Ps was reduced to the same extent as it was in the presence of excess unlabeled 9V Ps, the sample would be considered to have no Ab that required O-acetate for binding. In contrast, if addition of excess cold 9A Ps had no effect on the number of cpm bound, the sample would be considered to consist entirely of Ab that required the O-acetate groups for binding. Intermediate values were expressed as percentages between these two extremes.

Higher titers were obtained from adult postvaccination sera than from those of the children. Therefore, it was possible to construct standard curves for each serum. Individual RIA standard curves for unadsorbed serum were prepared by comparing the number of cpm bound with that of the standard rabbit antiserum. The standard curves for each individual donor were then used to convert cpm for unadsorbed serum and for serum adsorbed with 9V, de-O-acetylated 9V, or 9A Ps into micrograms of Ab per milliliter, and the content of Ab recognizing O-acetate groups was calculated as described above but with micrograms of Ab in place of cpm. The percentage of O-acetate-specific Ab was calculated with a correction for the cpm bound when unlabeled native 9V Ps was used as the competitor, as follows: 100 × (micrograms of detectable Ab per milliliter in the presence of inhibitor Ps − micrograms of detectable Ab per milliliter in the presence of 9V Ps)/(micrograms of detectable Ab per milliliter with no inhibitor − micrograms of detectable Ab per milliliter in the presence of 9V Ps). Thus, if the Ab titer in the presence of excess unlabeled 9A Ps was equal to the Ab titer in the presence of excess unlabeled 9V Ps, the sample was considered to have no Ab that required O-acetate for binding. In contrast, if addition of excess cold 9A Ps had no effect on the Ab titer detected, the sample was considered to consist entirely of Ab that required the O-acetate groups for binding. Intermediate values were expressed as percentages between these two extremes.

For statistical analysis, the percentage of O-acetate-specific Ab (determined by RIA) was natural log transformed, and means and 95% confidence intervals of the log-transformed percentages were calculated. These means and confidence ranges were compared for the groups of opsonin-positive and -negative samples. Upper 95% confidence range limits were calculated by adding the 95% confidence intervals to the mean of the natural logs of the percentages. Lower range limits were calculated by subtracting the 95% confidence interval from the mean of the natural logs of the percentages. For convenience, these upper and lower bounds then were converted to antilogs. Natural-log-transformed percentages in the two groups also were compared by the one-tailed t test. Overall, the statistical power of this study was sufficient to detect a threefold difference in mean O-acetate-specific Ab content with 90% confidence.

Opsonophagocytosis assay.

Human and monkey sera were serially diluted (twofold dilutions) in fetal calf serum in a 96-well plate. 9V pneumococci (mouse passaged; Merck) grown to log phase in Todd-Hewitt broth at 37°C in 5% CO2 (2,000 CFU) were preopsonized for 30 min at room temperature with the diluted serum. Rabbit complement (Cedarlane) and freshly isolated human neutrophils were added, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h at room temperature with gentle shaking in a total volume of 100 μl. Ten microliters of suspension was removed at 0 and 120 min and plated on Columbia agar for overnight incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2. Endpoint titers were determined based on a 50% reduction in colony counts in the samples collected at 120 min versus those collected at 0 min. Control wells which contained no complement were included to ensure that pneumococcal killing was complement mediated. Little or no killing by the type-specific antisera occurred in those wells. Opsonin titers were determined on individual sera by twofold serial dilution beginning with a dilution of 1:20. Each sample was tested in at least three independent assays, and the geometric means of all the results were calculated. No results were excluded from analysis. Titers were reported as the geometric means of three to five determinations. The between-assay 95% confidence limits for samples tested repeatedly were found to be twofold or greater. Therefore, 1:40 was chosen as the cutoff for positive opsonin activity since it was at least twofold greater than the minimum response and thus able to be distinguished from no response with at least 95% certainty. Where all three repetitions yielded titers of 1:20 or less, results were reported as negative, i.e., indeterminate or <1:40. Where at least one of three determinations had titers of 1:40 or greater, the geometric mean of all of the determinations was reported. Samples were then classified as opsonin positive or negative for further analysis.

RESULTS

Anti-9V Ab in infant rhesus monkeys.

Since infant rhesus monkeys do not produce Ab responses to unconjugated pneumococcal Ps but do respond to Ps-OMPC conjugates, the contribution of O-acetate groups to the ability of pneumococcal 9V-OMPC conjugate vaccines to induce functional Ab responses was evaluated in infant rhesus monkeys (16). Three different 9V-OMPC conjugate vaccines were prepared for comparison. First, pneumococcal 9V Ps was de-O-acetylated by treatment with 2.5 N NaOH. De-O-acetylated Ps was conjugated to N. meningitidis group B OMPC and was alum adsorbed. Secondly, an alum-adsorbed, monovalent 9V-OMPC conjugate that had been stored at 4°C for 3 years was assayed with an Ab specific for O-acetylated 9V Ps (factor g antiserum from Statens Seruminstitut). The reactivity was determined to be approximately 20% of the reactivity determined at the time of manufacture. Thirdly, a recently prepared aqueous monovalent 9V-OMPC conjugate was used as a control. The reactivity of this material with the factor g antiserum at initiation of the study was found to be approximately 80% of that detected originally at the time of manufacture. The aqueous bulk conjugate was then freshly adsorbed to alum adjuvant. All three lots of vaccine were used to immunize infant rhesus monkeys.

As shown in Table 1, all three conjugates were able to elicit anti-9V Ab detectable by RIA in infant rhesus monkeys. The Ab responses were similar in all three groups. As shown in Table 2, all three conjugates were able to elicit Ab that were comparably opsonophagocytic for pneumococcal 9V organisms. The opsonin titers in the control group given freshly prepared 9V-OMPC conjugate were similar to those in the groups given aged or chemically de-O-acetylated 9V conjugates. Thus, de-O-acetylated 9V Ps administered as an OMPC conjugate was sufficient to induce high-titered opsonophagocytic Ab against pneumococcal 9V Ps in infant rhesus monkeys. Therefore, the O-acetate groups are not required for the induction of biologically active Ab against 9V organisms in infant rhesus monkeys. Unlike the human sera described in this paper and reported elsewhere (6), there was a good correlation between RIA titers and opsonin titers in the infant monkey sera (Spearman rank correlation coefficient, r = 0.65; P = 0.009).

TABLE 1.

Immunogenicity of O-acetylated and de-O-acetylated pneumococcal type 9V-OMPC conjugates at a dose of 0.5 μg of Ps in infant rhesus monkeys

| % Deacetylation of conjugate |

Monkey | RIA titer (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual

|

GMTd

|

||||

| Day 0 | Day 42 | Day 0 | Day 42 | ||

| 20a | 626 | <0.2 | 218 | <0.2 | 166 |

| 633 | <0.2 | 70 | |||

| 687 | <0.2 | 240 | |||

| 707 | <0.2 | 198 | |||

| 714 | <0.2 | 176 | |||

| 99b | 682 | <0.2 | 160 | <0.2 | 194 |

| 698 | <0.2 | 207 | |||

| 710 | <0.2 | 212 | |||

| 708 | <0.2 | 286 | |||

| 746 | <0.2 | 136 | |||

| ≥80c | 701 | <0.2 | 73 | <0.2 | 115 |

| 727 | <0.2 | 188 | |||

| 729 | <0.2 | 82 | |||

| 728 | <0.2 | 158 | |||

| 726 | <0.2 | 115 | |||

9V-OMPC freshly adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide.

Chemically de-O-acetylated 9V-OMPC; confirmation by NMR and chemical analysis.

More than 80% de-O-acetylated 9V-OMPC as detected by immunoassay with type-specific capture Ab to the O-acetate epitope.

GMT, geometric mean titer.

TABLE 2.

Opsonophagocidal Ab in infant rhesus monkeys immunized with 0.5 μg of O-acetylated and de-O-acetylated pneumococcal type 9V-OMPC conjugates

| % Deacetylation of conjugate | Monkey | Opsonin titer (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual

|

GMTd

|

||||

| Day 0 | Day 42 | Day 0 | Day 42 | ||

| 20a | 626 | <100 | ≥4,000 | <100 | 1,099 |

| 633 | <100 | 100 | |||

| 687 | <100 | ≥4,000 | |||

| 707 | <100 | 1,000 | |||

| 714 | <100 | 1,000 | |||

| 99b | 682 | <100 | 1,000 | <100 | 1,320 |

| 698 | <100 | 1,000 | |||

| 710 | <100 | 2,000 | |||

| 708 | <100 | ≥4,000 | |||

| 746 | <100 | 500 | |||

| ≥80c | 701 | <100 | 2,000 | <100 | 1,320 |

| 727 | <100 | 2,000 | |||

| 729 | <100 | 2,000 | |||

| 728 | <100 | 1,000 | |||

| 726 | <100 | 500 | |||

9V-OMPC freshly adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide.

Chemically de-O-acetylated 9V-OMPC; confirmation by NMR and chemical analysis.

More than 80% de-O-acetylated 9V-OMPC as detected by immunoassay with type-specific capture Ab to the O-acetate epitope.

GMT, geometric mean titer.

Anti-9V Ab in humans.

Data on human subjects were collected to assess the magnitude of the O-acetate-dependent Ab response postvaccination in humans and its contribution to the functional Ab response to 9V Ps-OMPC conjugate vaccine and/or to pneumococcal Ps vaccine. Sera from either children immunized with three doses of Ps-OMPC conjugate plus a booster of polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine or adults given a single dose of polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine were subjected to an RIA to determine the percentage of anti-9V Ab which required O-acetate for recognition of the Ps. The sera then were evaluated for opsonin activity to assess whether the relative O-acetate-requiring Ab content might influence the opsonin activity.

To assess the relative contributions of Ab that required O-acetate for recognition and those that recognized the 9V backbone to the repertoire of human Ab responses to pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, sera from 13-month-old children were evaluated after immunization with a seven-valent Ps-OMPC conjugate vaccine at 2, 4, and 6 months and with a booster at 12 months with polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine. Sera were assayed for anti-9V Ab by ELISA, and 10 specimens with positive ELISA responses were selected for further evaluation by competitive RIA and opsonin assay. ELISAs and RIAs of preimmune sera were not performed due to the extremely low levels of Ab in most of these sera.

Two Ps, 9A and 9V (the 9V having been de-O-acetylated by base treatment) were used as competitors. Since the backbone of 9A is very similar to that of 9V, differing principally in its lack of O-acetates (12), use of these Ps in separate experiments provided internal controls for the effects of the chemical treatment used to remove the O-acetates from 9V and also for potential differences in the size or polydispersity of Ps prepared from the two strains that might affect the ability of the de-O-acetylated 9V to act as a competitor. As shown in Table 3, 3 of 10 sera (cases 42, 48, and 63) bound 25% or less of maximal cpm with 9A and with de-O-acetylated 9V Ps as the competitors, indicating a low level of Ab that depended for recognition on the presence of O-acetate (anti-O-acetate Ab). Of the remainder, four (cases 44, 51, 52, and 57) had intermediate levels of anti-O-acetate Ab (26 to 50%) and three had high levels of anti-O-acetate Ab (51 to 80% of maximal cpm bound with 9A or de-O-acetylated 9V Ps as the competitor).

TABLE 3.

O-acetate-specific Ab titers and opsonic Ab in 10 children given three doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and one dose of polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine

| Case | RIA titera | % of O-acetate-specific Abb

|

Opsonin GMTc | Opsonin statusd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d9V | 9A | ||||

| 42 | 8,165 | 12 | 17 | 50 | Pos |

| 44 | 8,405 | 47 | 39 | 63 | Pos |

| 48 | 6,614 | 2 | 5 | 101 | Pos |

| 51 | 6,840 | 23 | 26 | 320 | Pos |

| 52 | 4,899 | 13 | 30 | 101 | Pos |

| 57 | 7,633 | 26 | 8 | 80 | Pos |

| 61 | 8,045 | 42 | 60 | 101 | Pos |

| 62 | 6,833 | 87 | 88 | 127 | Pos |

| 63 | 4,539 | 18 | 18 | 25 | Neg |

| 64 | 7,501 | 63 | 83 | 320 | Pos |

RIA titer of serum (expressed as cpm of 14C-labeled Ps bound) in the absence of any competitor.

Determined by comparison of RIA cpm with de-O-acetylated 9V (d9V) Ps or 9A Ps as the competitor.

Geometric mean titer (GMT) of three to five separate determinations.

Scored positive (Pos) if GMT was >40 and negative (Neg) if GMT was ≤40.

The sera also were assayed for opsonophagocytic Ab activity. The opsonin titers were substantially lower than those observed in infant rhesus monkeys. Therefore, the titers were determined in three to five separate assays, and the geometric means of the titers were calculated across assays. Samples with mean titers above 1:40 were scored as positive. As shown in Table 3, 9V Ab in the children’s sera were found to be composed of from 2 to 88% O-acetate-specific 9V Ab. Opsonin assays against 9V Ps on these sera were positive across the range of 9V Ab compositions with respect to content of O-acetate-specific Ab. Therefore, in these human sera, the contributions of 9V backbone-specific and O-acetate-dependent Ab to the killing of pneumococci appeared to be similar.

Higher ELISA titers were present in adult postvaccination sera, than in the children’s sera. The 23 sera with high anti-9V ELISA values were selected for further evaluation by RIA and opsonin assay. As shown in Table 4, in adult sera, Ab that required O-acetate for recognition constituted from 6% to essentially all of the 9V Ab. Of 23 samples evaluated, 6 had low levels of O-acetate-specific Ab (25% or less of the original Ab titer remaining after absorption with both types of Ps lacking O-acetates), 10 had intermediate levels (26 to 50%), and the remainder had >50% of the Ab remaining after adsorption with de-O-acetylated 9V and with 9A Ps and therefore were considered to have high levels of O-acetate-specific Ab. Adult preimmunization samples had lower Ab titers as determined by RIA and in many instances were not evaluable for O-acetate-specific Ab. In those that were evaluable, individuals with both high and low levels of O-acetate Ab were observed (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

O-acetate-specific Ab titers and opsonic Ab in 23 adults given polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine

| Case | RIA titer (μg/ml) | % O-acetate-specific Abb

|

Opsonin titerc | Opsonin statusd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d9V | 9A | ||||

| 1 | 47.3 | 12 | 32 | 80 | Pos |

| 3 | 31.9 | 14 | 25 | 48 | Pos |

| 5 | 28.4 | 81 | 81 | 127 | Pos |

| 7 | 13.3 | 49 | 48 | 368 | Pos |

| 8 | 60.4 | 14 | 14 | 50 | Pos |

| 9 | 12.3 | 31 | 31 | 80 | Pos |

| 12 | 22.4 | 36 | 25 | 202 | Pos |

| 13 | 35.6 | 52 | 48 | 25 | Neg |

| 14 | 16.9 | 78 | 77 | 226 | Pos |

| 15 | 20.5 | 18 | 11 | 25 | Neg |

| 16 | 4.3 | 43 | 23 | 25 | Neg |

| 17 | 27.2 | 38 | 37 | 202 | Pos |

| 18 | 22.4 | 16 | 12 | 40 | Neg |

| 19 | 15.9 | 31 | 46 | <40 | Neg |

| 20 | 3.1 | 104 | 62 | 127 | Pos |

| 23 | 5.8 | 10 | 37 | <40 | Neg |

| 24 | 20.3 | 18 | 16 | <40 | Neg |

| 25 | 9.4 | 77 | 51 | <40 | Neg |

| 26 | 22.5 | 47 | 32 | <40 | Neg |

| 27 | 27.1 | 52 | 43 | 160 | Pos |

| 28 | 17.5 | 61 | 103 | 160 | Pos |

| 29 | 20.3 | 6 | 11 | <40 | Neg |

| 31 | 12.6 | 41 | 43 | 160 | Pos |

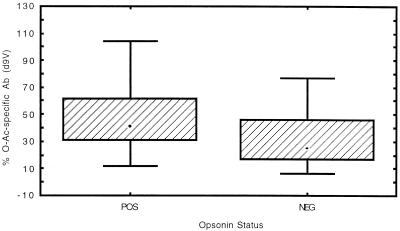

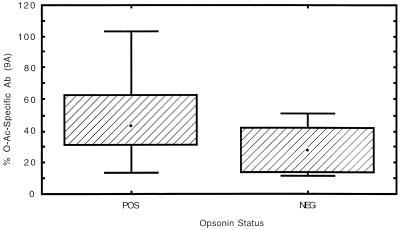

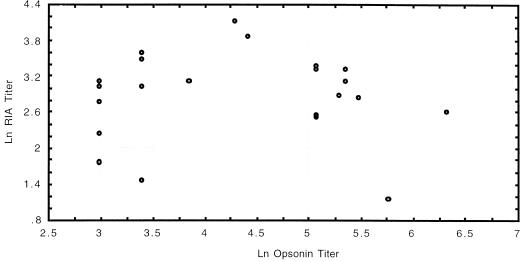

The range of opsonin titers was similar to that observed for the children’s sera described above. Therefore, a similar method of analysis was used, and samples with geometric mean titers greater than 1:40 over three to five separate assays were considered positive. Preimmunization samples were uniformly negative for opsonin activity. Positive opsonin activity was observed in sera that contained from 12 to >99% O-acetate specific Ab. The relationship between the proportion of Ab recognizing O-acetylated Ps and the level of opsonin activity was evaluated by Spearman rank correlation and by comparing 95% confidence limits for sera with and without detectable opsonin activity. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient r was 0.42 (P = 0.049) when de-O-acetylated 9V Ps was used as competitor and 0.38 (P = 0.070) when 9A Ps was used. The geometric mean O-acetate-specific Ab content for opsonin-negative sera based on adsorption with de-O-acetylated 9V Ps was 25%, with 95% confidence limits from 15 to 40%; based on 9A Ps, the geometric mean content was 26% with 95% confidence limits from 16 to 36%. For opsonin-positive sera, the geometric mean content of O-acetate-specific Ab was 36% with 95% confidence limits of 24 to 52% with de-O-acetylated 9V used as the competitor and 38% with 95% confidence limits from 28 to 51% when 9A Ps was used. The one-tailed P values by t test were 0.08 when de-O-acetylated 9V Ps was used as the absorbent and 0.02 when 9A Ps was used. Figures 1 and 2 show box plots comparing O-acetate-specific-Ab content of opsonin-positive and opsonin-negative sera. Thus, the relationship between O-acetate-specific-Ab content and opsonin activity in this study could be considered not significant or marginally significant at best since no consistent trend toward statistical significance was seen between the two sets of experimental conditions and the two methods of analysis used. Figure 3 shows a scatter plot comparing the total RIA titers (without absorption) with opsonin titers in the adult sera; total RIA titer does not appear to be predictive of whether sera will have opsonin activity (Spearman rank correlation coefficient, r = 0.09; P = 0.68). This observation has been previously reported by others (6).

FIG. 1.

Box and whisker plot of percentage of Ab recognizing O-acetylated 9V in opsonin-positive (POS) versus opsonin-negative (NEG) adult sera. Chemically deacetylated 9V Ps (d9V) was used as the competitor. Bars, minimum and maximum values; boxes, middle 50% of observed values; dots, median values.

FIG. 2.

Box and whisker plot of percentage of Ab recognizing O-acetylated 9V in opsonin-positive (POS) versus opsonin-negative (NEG) adult sera. 9A Ps was used as the competitor. Bars, minimum and maximum values; boxes, middle 50% of observed values; dots, median values.

FIG. 3.

Scatter plot comparison of total RIA Ab content of unabsorbed adult sera with opsonin titer. RIA titers are expressed as micrograms per milliliter.

DISCUSSION

In infant rhesus monkeys, Ab raised against O-acetylated 9V Ps and Ab raised against de-O-acetylated 9V Ps are both able to opsonize 9V organisms in vitro. Children immunized with a vaccine regimen of three doses of pneumococcal Ps-OMPC conjugate and one of polyvalent pneumococcal Ps vaccine produced various levels of Ab that required O-acetate for recognition of 9V Ps, yet 9 of 10 produced Ab were able to kill type 9V bacteria. Adults immunized with a single dose of polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine also produced various levels of Ab that required O-acetate for binding. Sera in which O-acetate-specific Ab accounted for more than 50% of total 9V Ab were found in a significant minority (7 of 23) of adults while the remainder exhibited a mixed response phenotype in which most or all of the response appeared to recognize predominantly the non-O-acetylated form of the antigen. Adult sera with O-acetate-specific-Ab contents as low as 11% were effective at opsonizing type 9V bacteria while others with as much as 77% O-acetate-specific Ab were negative in the opsonin assay. The intent of the study was to examine human antisera across the complete range of high to low levels of O-acetate-specific-Ab content to determine whether a difference in functional activity exists. A statistically significant difference in opsonizing activity between the groups with high and low levels of O-acetate-specific Ab was not detected.

While the O-acetate moiety has previously been found to be an important epitope (7), the data obtained in these studies suggest that O-acetate-specific Ab are not absolutely required for opsonization of pneumococcal 9V organisms. In both humans and infant rhesus monkeys, backbone-specific Ab appear to be sufficient for opsonic killing of type 9V. These results might be surprising considering that the 9V Ps is a linear structure having no evidence of secondary structure (12) and is decorated with an average of 1 to 2 mol of O-acetate groups per mol of Ps repeat units (8). This primary structure allows for maximal exposure of the O-acetate groups along the Ps backbone to the external milieu and thus the O-acetylated saccharides might be more accessible to complement-fixing Ab. However, due to the heterogeneity in both the location of the O-acetate groups and the amount of O-acetylation among individual 9V repeat units, the O-acetate containing monosaccharides may present a group of epitopes too diverse to generate a large population of cross-reacting Ab for opsonization. In contrast, the nonacetylated Ps backbone may offer both sufficient solvent exposure to ensure the induction and binding of functional Ab with subsequent opsonic activity and a more consistent structure for recognition by functional Ab. NMR studies have shown that O-acetates can be found in varying proportions on the 2 (17%) and 3 (25%) positions of either of the two α-GlcA residues and on the 4 (4%) and 6 (55%) positions of the β-ManNAc residue in each repeat unit, while O-acetylation of the α-Glc may also be seen (12). Since it is possible to perform NMR studies only on purified Ps, the extent to which purification may affect the number and location of O-acetates is unknown. Further changes in O-acetate content and distribution may occur in solution, but such changes are not apparent when anhydrous Ps powder is stored at temperatures below −15°C (8).

In some individual samples, the percentage of O-acetate-specific Ab observed appeared to differ when de-O-acetylated 9V or 9A Ps was used as the competitor. However, there were no evident trends either with respect to one competitor Ps giving consistently higher values than the other (P > 0.4 by paired t test, sign test, and Wilcoxon matched pairs test) or with respect to differences relating to RIA titer or the presence or absence of opsonin activity. Thus, it appears that the differences are likely to be due to experimental variation. Since type 9N Ps is present in the Ps vaccine that was used for immunization of the adults and as a booster in the children in the studies, a difference could be related to different levels of cross-reactivity in individual responses to the type 9N Ps. A more surprising observation was the absence of detectable opsonin activity against 9V bacteria in 9 of 23 adults given the polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine. However, since individuals with minimal primary responses may still be capable of mounting protective responses on subsequent exposure to a pathogen, it is not appropriate to draw conclusions about the efficacy of type 9V Ps vaccines or the adequacy of opsonizing Ab as surrogate markers for protection from this small serological study. Genetic differences among individual subjects also may play some role since genetic regulation of immune responses to pneumococcal Ps has been observed in human subjects (9).

Comparison of RIA titers and opsonin assay titers for individual sera indicated little direct correlation between the two values. There are several possible explanations for this observation. RIAs detect relatively high-avidity IgG and IgM Ab which are specific for purified Ps. Opsonin assays detect those Ab (IgG and IgM) that can recognize and bind intact capsule Ps, fix complement, and lead to killing of the pneumococci. Differences in Ab populations detected by the two different assay methods may be related to differences in epitopes presented by purified Ps versus capsular Ps, differences in tertiary structure of the Ps, and the presence of minor contaminants in the purified Ps. Most likely, only a well-defined subset of all specific Ab are able to opsonize pneumococci, and in some cases, that subset may be below the limits of detection of the in vitro opsonin assay utilized in this investigation. However, both assays are valuable in the analysis of Ab response to specific antigens.

Various chemical treatments of type 9V Ps can lead to the loss of some or all of its O-acetate groups (8). However, based on the results of this investigation, oxidation of these bonds with subsequent loss of O-acetate groups does not appear likely to affect the ability of the vaccine to induce functional Ab against this important pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Kniskern and P. Burke for determining ELISA serum Ab titers; B. Gray for help with functional Ab analysis; D. Arena for supplying clinical specimens for analysis; W. Hurni and J. Hennessey for antigenicity assays; S. Marburg for preparation of de-O-acetylated 9V conjugate; A. Lee, A. Aunins, and W. Manger for preparation of 9A and 9V conjugates; T. Schofield for help with statistical analysis; and J. Schiffman for preparation of the radiolabeled 9V and 9A Ps.

REFERENCES

- 1.Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson E L, Kennedy D J, Geldmacher K M, Donnelly J J, Mendelman P M. Immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in infants. J Pediatr. 1996;128:649–653. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)80130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolan G, Broome C V, Facklam R R, Plikaytis B D, Fraser D W, Schlech W F. Pneumococcal vaccine efficacy in selected populations in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:1–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan C Y, Molrine D C, George S, Tarbell N J, Mauch P, Diller L, Shamberger R C, Phillips N R, Goorin A, Ambrosino D M. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine primes for antibody responses to polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine after treatment of Hodgkin’s disease. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:256–258. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagan R, Muallem M, Melamed R, Leroy O, Yagupsky P. Reduction of pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in early infancy after immunization with tetravalent pneumococcal vaccines conjugated to either tetanus toxoid or diphtheria toxoid. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:1060–1064. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199711000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedson D S. Pneumococcal vaccine. In: Plotkin S A, Mortimer E A, editors. Vaccines—1988. W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Co.; 1988. pp. 271–299. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine M J, Smith W A, Carson C A, Meffe F, Sankey S S, Weisfeld L A, Detsky A S, Kapoor W N. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2666–2667. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420230051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hepler R W, Ip C C Y. Application of capillary ion electrophoresis and ion chromatography for the determination of O-acetate groups in bacterial polysaccharides. J Chromatogr A. 1994;680:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)80068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musher D M, Groover J E, Watson D A, Pandey J P, Rodriguez-Barradas M C, Baughn R E, Pollack M S, Graviss E A, deAndrade M, Amos C I. Genetic regulation of the capacity to make immunoglobulin G to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. J Invest Med. 1997;45:57–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry M B, Daoust V, Carlo D J. The specific capsular polysaccharide of streptococcus pneumoniae type 9V. Can J Biochem. 1981;59:524–533. doi: 10.1139/o81-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichichero M E, Shelly M A, Treanor J J. Evaluation of a pentavalent conjugated pneumococcal vaccine in toddlers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:72–74. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199701000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutherford T J, Jones C, Davies D B, Elliott A C. Molecular recognition of antigenic polysaccharides: a conformational comparison of capsules from Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 9. Carbohydr Res. 1994;265:97–111. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(94)00212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smit P, Oberholzer D, Hayden-Smith S, Koornhof H J, Hilleman M R. Protective efficacy of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines. JAMA. 1977;238:2613–2616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szu S C, Lee C-J, Parke J C, Jr, Schiffman G, Henrichsen J, Austrian R, Rastogi S C, Robbins J B. Cross-immunogenicity of pneumococcal group 9 capsular polysaccharides in adult volunteers. Infect Immun. 1982;35:777–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.777-782.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Dam J E G, Fleer A, Snippe H. Immunogenicity and immunochemistry of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1990;58:1–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02388078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vella P P, Marburg S, Staub J M, Kniskern P J, Miller W, Hagopian A, Ip C, Tolman R L, Rusk C M, Chupak L S, Ellis R W. Immunogenicity of conjugate vaccines consisting of pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide types 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F and a meningococcal outer membrane protein complex. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4977–4983. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.4977-4983.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]