Abstract

Context

Metrnl is a novel adipokine mainly produced by white adipose tissue, which plays important roles in insulin sensitization, and energy homeostasis. However, information about the function of Metrnl in Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) remains unclear.

Methods

This is a control study, which enrolled 176 adults with MAFLD and 176 normal controls. They were matched in body mass index (BMI), age, and sex. Serum Metrnl was determined by ELISA. Other biochemical data were also collected.

Results

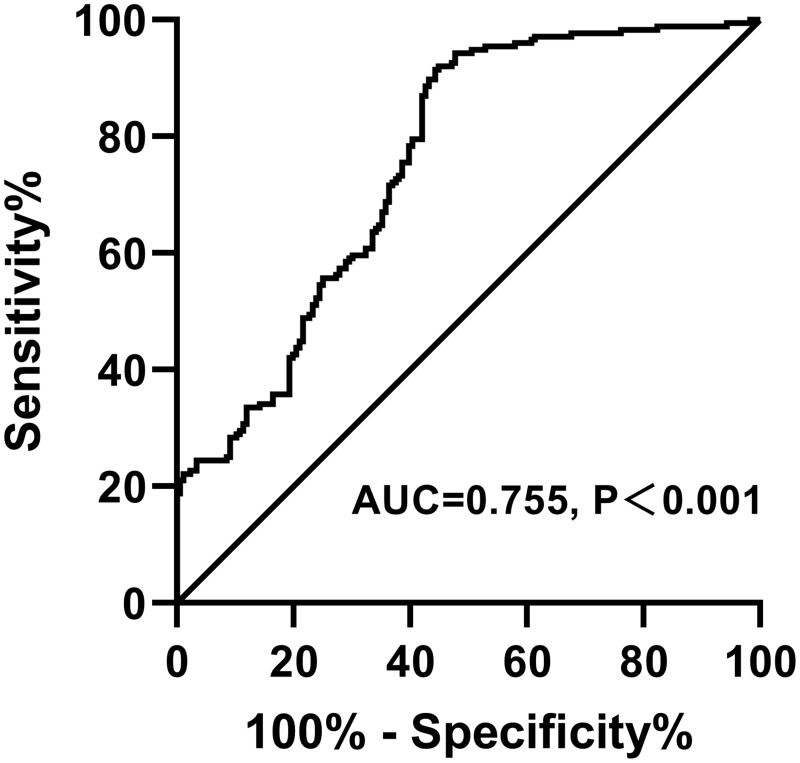

Compared to the controls, circulating Metrnl was prominently decreased in the MAFLD adults (P<0.001). Next, binary logistic regression model indicated that sex, waist circumference (WC), triglyceride, γ-gamma glutamyl transferase(γ-GGT), and Metrnl was independently associated with MAFLD. Further, as Metrnl levels elevated across its tertiles, the rate of MAFLD decreased (67.52, 66.95, and 15.38%; P value for trend<0.001). Data from multivariate logistic regression models evidenced that compared with the lowest tertile of Metrnl, the odds ratio of MAFLD was 0.023(95% CI 0.006–0.086, P<0.001) for the highest tertile after adjusting for potential confounders. Besides, area under ROC curve of Metrnl for diagnosis MAFLD was 0.755(95% CI 0.705–0.805). Metrnl was positively correlated with diastolic blood pressure, WC, BMI, systolic blood pressure, γ-GGT, and Creatinine in MAFLD. Finally, we found systolic blood pressure and Creatinine were independently related to serum Metrnl in MAFLD.

Conclusion

Serum Metrnl is reduced in adult with MAFLD. The results suggest that Metrnl may be a protective factor associated with the pathogenesis of MAFLD.

Keywords: metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, metrnl, adipokine, adipose tissue

Introduction

Nowadays, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the most popular chronic liver disease worldwide.1 Owing to its high prevalence, NAFLD becomes the leading cause of liver-related mortality in several countries.2 NAFLD varies from the more benign situation of non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and may progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis.3 Adults with NAFLD often have one or more components of the metabolic syndrome (MS) like diabetes, insulin resistance, or systemic hypertension. In 2020, an international expert group proposed the concept of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) to emphasize the contribution of cardiac metabolic risk factors to the development and progression of liver disease.4 Many inflammatory markers have been related with MAFLD, include hemogram derived inflammatory indices and uric acid based markers.5 According to a large amount of literature data, many doctors alleviate NAFLD by using natural products such as berberine and resveratrol.6 Although valuable progress has been made, there are several obstacles to developing efficient treatment interventions. One of the most important challenges is to continue to rely on liver biopsy for MAFLD diagnosis. At present, there is no reliable biomarker that can accurately diagnose and stage MAFLD throughout the entire disease spectrum.

Adipokines secreted by adipose tissue play crucial effects in energy balance and glucose metabolism. Dysregulation of adipokines has been implicated in several inflammatory conditions, such as glucose intolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus(T2DM), diabetic nephropathy, and heart conditions.7–9 Recent study found that adipokines including adiponectin, adipsin, and visfatin were associated with the prevalence of MAFLD.10

Meteorin-like hormone (Metrnl), mainly expressed in white adipose tissue, is a protein homologous to the neurotrophic factor Metrn.11 Metrnl regulates white adipose browning, insulin sensitization, energy expenditure, lipid metabolism, inflammation, and neural development.12–14 Besides, Metrnl promotes muscle regeneration in skeletal muscle, glucose uptake, and fat oxidation.15 Consistent with Metrnl in improving insulin resistance at cellular and animal levels, several clinical studies accessed the relationship between circulating Metrnl and metabolic diseases. Dadmanesh, M. et al14 reported that serum Metrnl was reduced in patients with T2DM and coronary artery disease and negatively associated with inflammatory cytokines and insulin resistance. In thyroid autoimmune diseases, Gong et al16 found that Metrnl levels in Graves’ disease (GD) patients were significantly lower than those in normal controls. Recently, two independent team both found that Metrnl concentration decreased in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and presented inverse correlation with insulin resistance.17,18 However, information is not available regarding the role of Metrnl in NAFLD/MAFLD. Only Du et al19 reported that Metrnl overexpression can effectively ameliorate fulminant hepatitis in mice. Considering the role of Metrnl in inflammation and metabolic disorders, we tried to assess the clinical relevance of Metrnl in patients with MAFLD.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Study Design

This is a case-control study. The study included 176 patients with MAFLD and 176 healthy adults. These patients with MAFLD were screened from the physical examination Center of Binzhou Medical University Hospital from August 2021 to December 2022. According to the design, MAFLD patients and healthy volunteers were matched in age and sex. Ultrasound imaging technology was used for liver steatosis diagnosis. The typical ultrasound features of fatty liver include the presence of echogenic differences between the kidney and liver, posterior attenuation of the ultrasound beam with or without, blurred blood vessels, and difficulty in displaying the diaphragm or gallbladder wall. According to the diagnostic criteria for the Asian population in the 2020 international expert consensus,4 the diagnostic standard of MAFLD is one of the following three conditions based on liver steatosis, namely overweight/obesity, T2DM or metabolic dysfunction. Metabolic dysfunction is defined as having at least two metabolic risk abnormalities: (1) Plasma triglyceride (TG) ≥1.70 mmol/L or current use of lipid-lowering drugs; (2) Blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, or currently using antihypertensive drugs; (3) High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C): female <1.3 mmol/L, male <1.0 mmol/L, or currently using lipid-lowering drugs; (4) Blood glucose 7.8~11.0 mmol/L or fasting glucose (FG) 5.6~6.9 mmol/L or HbA1c 5.7%~6.4%.

All human rights were observed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University Hospital. Everyone signed an informed consent form about the study.

Anthropometric Data Collection

The anthropometric data includes hip circumference (HC), waist circumference (WC), height, weight, and blood pressure were collected by professional nurses. Body mass index (BMI) =weight (kg)/height (m2). Before measuring blood pressure, each person should rest for no less than 10 minutes. Via an electronic sphygmomanometer (OMRON, Japan) blood pressure was measured two times. Then the average of two values was calculated.

Biochemical Measurements

Fasting blood samples were taken and separated through centrifuge. Fasting glucose (FG), serum lipid profile, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ-gamma glutamyl transferase (γ-GGT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using the AU680 automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter, USA). The remaining serum samples were stored at −80°C until Metrnl measurement.

Measurements of Metrnl

Serum Metrnl was detected by human ELISA kit (Catalog Number: DY7867-05; R&D systems, USA). Measurements were made in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA) and SPSS version 26 (IBM, USA). Data for normal distributions as mean ± SD and Data for skew distributions were expressed as median (IQR, 25th-75th). Chi-square test was used to compare the enumeration data. Kruskal–Wallis test or one-way ANOVA were used for multiple tests between groups. Multiple stepwise regression analysis was used to identify the independent factors associated with Metrnl. All subjects were stratified according to Metrnl tertiles (T1: <233.65pg/mL; T2: 233.65–346.24 pg/mL; T3: ≥346.24pg/mL, and then the association between Metrnl and MAFLD prevalence was assessed using trend Chi-square test. To control for potential confounding factors that may be risk factors for MAFLD, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for MAFLD were calculated using multivariate logistic regression models. ROC curve was used to verify the detection effect of Metrnl level on MAFLD. P value <0.05 (two side) was considered statistically significant.

Results

General Characteristics of the Subjects

All subjects’ clinical parameters are shown in Table 1. There is no notable difference between MAFLD group and normal group in sex, age, uric acid, creatinine, LDL-C, and White blood cell. As expected, BMI, WC, HC, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), fasting glucose, TG, TC, ALT, AST, γ-GGT of MAFLD group are significantly higher than those in control group, while HDL-C and Metrnl are significantly lower (P<0.001).

Table 1.

General Clinical and Laboratory Parameter in Participants with and without MAFLD

| Variable | Controls | MAFLD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 176 | 176 | |

| Sex(M/F) | 88/88 | 88/88 | 1.000 |

| #Age(years) | 40(31−54) | 44(35−56) | 0.103 |

| #BMI(kg/m2) | 23(21−24) | 26(24−28) | <0.001 |

| #WC(cm) | 83(75−88) | 93(88−99) | <0.001 |

| *HC (cm) | 98.29±6.32 | 102.40±6.32 | <0.001 |

| #SBP (mmHg) | 120(109−133) | 132(121−142) | <0.001 |

| #DBP (mmHg) | 77(72−87) | 85(80−90) | <0.001 |

| #FBG(mmol/L) | 4.96(4.60−5.33) | 5.32(4.95−5.83) | <0.001 |

| #TG(mmol/L) | 1.03(0.76−1.39) | 1.07(1.21−2.14) | <0.001 |

| *TC (mmol/L) | 4.76±0.83 | 5.17±0.98 | <0.001 |

| #UA(μmol/L) | 332.40(271.45−377.87) | 342.40(299.60−409.70) | 0.006 |

| #Creatinine(μmol/L) | 68(57−81) | 66(57−77) | 0.126 |

| #ALT(U/L) | 15(12−20) | 22(16−35) | <0.001 |

| #AST(U/L) | 21(18−25) | 23(20−28) | <0.001 |

| #γ-GGT(mmol/L) | 18.50(14.30−24.07) | 26.80(20.40−40.90) | <0.001 |

| *LDL-C(mmol/L) | 2.94±0.63 | 3.30±0.74 | 0.231 |

| *HDL-C(mmol/L) | 1.36±0.25 | 1.24±0.27 | <0.001 |

| #WBC(×109/L) | 5.90(5.10−7.00) | 6.50(5.50−7.33) | 0.007 |

| #Metrnl(pg/mL) | 379.06(248.81−504.70) | 240.40(176.28−305.75) | <0.001 |

Notes: *Data normally distributed are shown as mean ± SD. Independent Sample t test was performed. #Data with skewed distribution are shown as median (25th−75th). Mann–Whitney U-test was performed.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HC, hip circumference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TG, Triglyceride; TC, Total cholesterol; UA, uric acid; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GGT, γ-gamma glutamyl transferase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; WBC, white blood cell.

Serum Metrnl

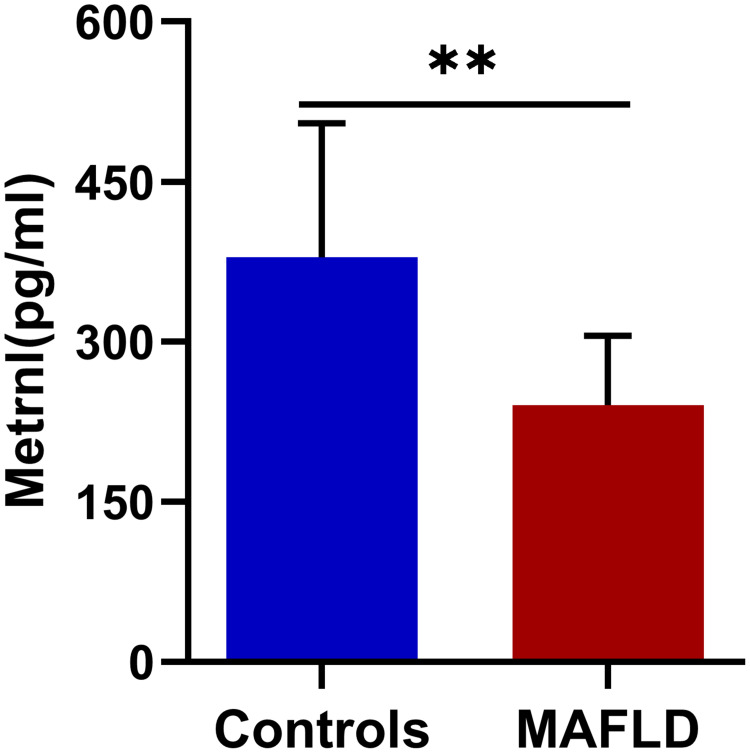

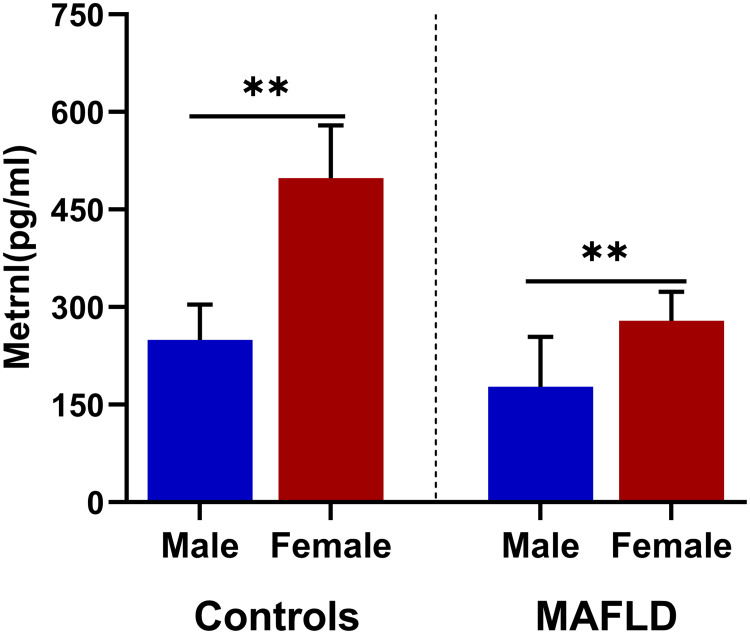

As presented in Figure 1, serum Metrnl is significantly decreased in the MAFLD group compared to the controls [379.06(248.81−504.70) vs 240.40(176.28−305.75) pg/mL, median (25th−75th), P<0.001]. Interestingly, there is a significant gender difference in serum Metrnl. Both in the MAFLD group and the normal group, serum Metrnl is significantly higher in female (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Serum Metrnl levels (median (IQR) marked) in MAFLD and control group. ** P<0.01.

Figure 2.

Gender differences of serum Metrnl (median (IQR) marked) in MAFLD and control group. ** P<0.01.

Correlations Between Serum Metrnl and Clinical Parameters

As listed in Table 2, Pearson correlation analysis indicates that the levels of serum Metrnl is positively correlated with SBP(r=−0.169, P=0.036), DBP(r=−0.215, P=0.008), γ-GGT(r=−0.162, P=0.032), Creatinine(r=−0.284, P<0.001). In the stepwise linear regression model, when adjusting for covariates of Metrnl in the Pearson correlation analysis, DBP and γ-GGT are finally excluded from the model. SBP and Creatinine are independently related to Metrnl in MAFLD (P=0.027, P=0.008, respectively).

Table 2.

Correlation Between Serum Metrnl and Other Variables

| Metrnl | Univariate Correlations | Multivariate Regression Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | Standardβ | P | |

| Age | 0.010 | 0.900 | − | − |

| BMI | −0.027 | 0.730 | − | − |

| WC | −0.122 | 0.142 | − | − |

| SBP | −0.169 | 0.036 | −0.177 | 0.027 |

| DBP | −0.215 | 0.008 | − | − |

| FBG | −0.024 | 0.750 | − | − |

| ALT | −0.127 | 0.093 | − | − |

| AST | 0.019 | 0.798 | − | − |

| γ-GGT | −0.162 | 0.032 | ||

| UA | −0.138 | 0.071 | − | − |

| Creatinine | −0.284 | <0.001 | −0.213 | 0.008 |

| TG | −0.004 | 0.961 | − | − |

| TC | −0.140 | 0.066 | − | − |

| LDL-C | −0.028 | 0.718 | − | − |

| HDL-C | 0.079 | 0.302 | − | − |

| WBC | −0.054 | 0.479 | − | − |

Note: Data with statistical differences have been bolded.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GGT, γ-gamma glutamyl transferase; UA, uric acid; TG, Triglyceride; TC, Total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; WBC, white blood cell.

Serum Metrnl and MAFLD

To access the risk factors associated with MAFLD, further we constructed binary logistic regression model. In the univariate models, enhanced Sex, WC, DBP, Fasting glucose, Creatinine, γ-GGT, Metrnl, and reduced Creatinine Metrnl levels are proved to be related to higher incidence of MAFLD. Interestingly, only Sex, WC, TG, γ-GGT and Metrnl are independently correlated to higher MAFLD risk in the multivariate model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent Factors Associated with MAFLD in Binary Logistic Regression Models

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | β±SE | Wald | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex | 0.010 | 2.318±0.662 | 12.268 | 10.156(2.766–37.158) | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.125 | ||||

| BMI | 0.166 | ||||

| WC | 0.006 | 0.114±0.028 | 16.588 | 1.121(1.061–1.184) | <0.001 |

| SBP | 0.166 | ||||

| DBP | 0.044 | 0.013±0.021 | 0.409 | 1.013(0.973–1.056) | 0.523 |

| FBG | 0.017 | 0.330±0230 | 2.057 | 1.391(0.886–2.183) | 0.152 |

| TG | 0.085 | 0.808±0.291 | 7.718 | 2.244 (1.269–3.969) | 0.005 |

| TC | 0.236 | ||||

| LDL-C | 0.105 | ||||

| HDL-C | 0.277 | ||||

| Creatinine | 0.046 | −0.031±0.017 | 3.132 | 0.097(0.937–1.003) | 0.077 |

| UC | 0.219 | ||||

| WBC | 0.759 | ||||

| ALT | 0.707 | ||||

| AST | 0.400 | ||||

| γ-GGT | 0.008 | 0.058±0.017 | 12.317 | 1.060(1.026–1.095) | <0.001 |

| Metrnl | <0.001 | −0.010±0.002 | 29.915 | 0.990(0.987–0.994) | <0.001 |

Note: Data with statistical differences have been bolded.

Abbreviations: β, Regression coefficient; SE, standard error; BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TG, Triglyceride; TC, Total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; UA, uric acid; WBC, white blood cell; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GGT, γ-gamma glutamyl transferase.

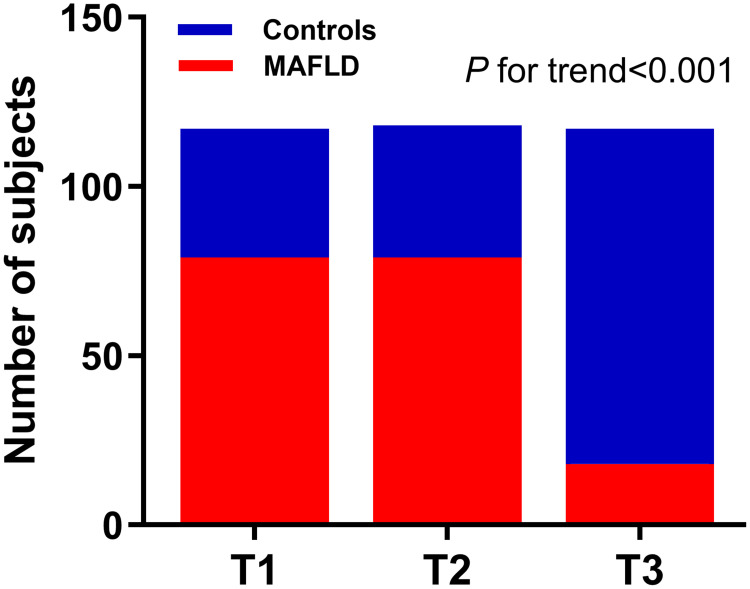

Next, according to Metrnl tertiles (T1: <233.65pg/mL; T2: 233.65–346.24pg/mL; T3: ≥346.24pg/mL), all the participants were stratified into trisection. The clinical parameters are shown in Table 4. Variables including Sex, BMI, WC, percentage of MAFLD, SBP, DBP, FG, TG, TC, Uric acid, ALT, AST, γ-GGT, and Creatinine present obvious discrepancy across the tertiles. In Figure 3, trend Chi-square test indicates that the percentage of MAFLD gradually increased, as Metrnl levels elevated across its tertiles (T1: 67.52%, T2: 66.95%, and T3: 15.38%; P value for trend<0.001).

Table 4.

General Clinical and Laboratory Parameter of All Subjects According to Serum Metrnl

| Variable | T1 | T2 | T3 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Metrnl (pg/mL) | <233.65 | 233.65–346.24 | ≥346.24 | − |

| N | 117 | 118 | 117 | − |

| Percentage of MAFLD (%) | 67.52 | 66.95 | 15.38 | <0.001 |

| Sex(M/F) | 99/18 | 58/60 | 12/105 | <0.001 |

| #Age(years) | 40(32−55) | 46(33−58) | 41(32−51) | 0.103 |

| #BMI(kg/m2) | 26(24−27) | 25(23−27) | 23(21−24) | <0.001 |

| #WC(cm) | 91(86−98) | 89(84−95) | 82(74−88) | <0.001 |

| *HC (cm) | 101.76±6.36 | 100.10±5.81 | 98.71±7.27 | 0.003 |

| #SBP (mmHg) | 131(120−142) | 128(117−139) | 114(106−133) | <0.001 |

| #DBP (mmHg) | 84(78−90) | 83(78−88) | 75(71−85) | <0.001 |

| #FBG(mmol/L) | 5.23(4.87−5.89) | 5.25(4.88−5.59) | 4.92(4.58−5.23) | <0.001 |

| #TG(mmol/L) | 1.44(1.04−1.95) | 1.50(1.08−2.06) | 1.01(0.71−1.42) | <0.001 |

| *TC (mmol/L) | 5.11±0.87 | 5.09±1.02 | 4.68±0.83 | <0.001 |

| *LDL-C(mmol/L) | 3.17±0.67 | 3.24±0.79 | 2.94±0.63 | 0.003 |

| *HDL-C(mmol/L) | 1.27±0.29 | 1.27±0.28 | 1.35±0.25 | 0.027 |

| #UC(μmol/L) | 363.20(307.35−423.50) | 342.00(298.70−395.80) | 299.40(260.75−347.45) | <0.001 |

| #ALT(U/L) | 22.60(17.40−33.68) | 17.90(14.57−26.95) | 15.20(10.90−20.40) | <0.001 |

| #AST(U/L) | 23.10(20.10−27.80) | 22.40(19.70−26.70) | 20.50(18.00−24.60) | <0.001 |

| #γ-GGT(U/L) | 26.50(20.15−38.05) | 22.60(19.05−31.30) | 15.90 (13.30−22.65) | <0.001 |

| #Creatinine(μmol/L) | 77(65−83) | 67(59−80) | 59.30(51.90−68.10) | <0.001 |

| #WBC(×109/L) | 6.50(5.45−7.35) | 6.30(5.50−7.30) | 5.60(4.90−6.80) | 0.005 |

Notes: *Data normally distributed are shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA test was performed. #Data with skewed distribution are shown as median (25th−75th). Kruskal–Wallis test was performed.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HC, hip circumference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TG, Triglyceride; TC, Total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; UA, uric acid; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GGT, γ-gamma glutamyl transferase; WBC, white blood cell.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of MAFLD according to serum Metrnl tertiles. T1–T3: 67.52%, 66.95%, and 15.38%. P<0.001.

In logistic regression model 1 (reference, T1), an OR of 0.087 (95% CI 0.046–0.165) in the 3rd tertile is observed for MAFLD prevalence(P for trend<0.001) (Table 5). In model 2, when further controlled BMI, WC, HC, age, and sex, the OR was 0.022 (95% CI 0.007–0.069) for the 3rd tertile(P for trend<0.001). In model 3, even after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, WC, HC, SBP, DBP and FBG, which could be confounders of Metrnl, the tendency persists with an OR of 0.030 (95% CI 0.009–0.098) in the 3rd tertile(P for trend<0.001). Finally, after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, WC, HC, SBP, DBP, FBG, TC, TG, HDL, LDL, γ-GGT, AST, ALT, Creatinine, UA, and WBC, the tendency still persists (P for trend<0.001).

Table 5.

MAFLD Risk According to Metrnl Tertiles in Multinomial Logistic Regression Models

| OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1(Reference) | T2 | T3 | P for Trend | |

| Model 1 | 1 | 0.794(0.565–1.680) | 0.087(0.046–0.165) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1 | 0.539(0.259–1.121) | 0.022(0.007–0.069) | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1 | 0.592(0.270–1.296) | 0.030(0.009–0.098) | <0.001 |

| Model 4 | 1 | 0.580(0.244–1.380) | 0.023(0.006–0.086) | <0.001 |

Notes: Model 1: crude; Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, WC, HC; Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, WC, HC, SBP, DBP, FBG. Model 4: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, WC, HC, SBP, DBP, FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, γ-GGT, AST, ALT, Creatinine, UA, WBC.

As illustrated in Figure 4, ROC curve of Metrnl values for MAFLD diagnosis has been constructed. Area under the curve (AUC) is 0.755(95% CI 0.7047–0.8054), P<0.001.

Figure 4.

ROC curves of Metrnl values for MAFLD diagnosis. AUC= 0.755 (95% CI 0.7047–0.8054), P<0.001.

Discussion

The current study firstly observed that circulating Metrnl decreased in patients with MAFLD when compared to that in controls. After adjusting multiple confounding factors, the incidence of MAFLD gradually decreases following increasing Metrnl concentration. Our data suggest that Metrnl may be a protective factor associated with the pathogenesis of MAFLD.

The development of MAFLD is closely related to systemic metabolic disorders.20 Adipokines play a central role in the occurrence of MAFLD by triggering metabolic regulation, inducing pleiotropic effects, and chronic low-grade inflammation.21 For instance, a correlation has been found between increased circulating leptin levels and MAFLD severity. Although leptin is an anti-lipotropic hormone that prevents the accumulation of liver lipids and promotes their mobilization, leptin resistance may result in leptin’s inability to relieve hepatic steatosis.22 In addition, high leptin plasma levels from obese adipose tissue are associated with fibrosis mechanisms and liver inflammation.22 On the contrary, adiponectin has been reported to protect the liver from fibrosis, and inflammation steatosis.23 Most importantly in bariatric surgery there is a complete rearrangement of adipokines and gut hormones. For example, after short-term (<3 months) fasting after weight loss surgery such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the levels of serum ghrelin, Glucagon-like peptide-1, Insulin, and Leptin are decreased.24 Therefore, modulation of adipokine levels may be potential therapeutic targets for MAFLD. Antagonists, monoclonal humanized antibodies against adipokines receptors, and MicroRNAs targeting specific adipokines are likely to be viable options.25 However, these methods may cross-react with endogenous adipokines, which limited their therapeutic effectiveness. Hence, the role of other novel adipokines in MAFLD is worth exploring.

Previous studies have suggested Metrnl have been implicated in glucose homeostasis, such as improving increasing energy expenditure, facilitating adipose tissue browning, and insulin sensitivity.13,26 To bridge the gap between bench and bedside, clinical studies have been performed to explore the relationship between circulatory Metrnl and metabolic diseases. Andreas Schmid et al27 confirmed that systemic Metrnl is transiently upregulated during massive weight loss and gene expression in adipocytes is differentially regulated. Moradi, N et al shown that serum Metrnl decreased in obese children, especially in children with metabolic syndrome.28 Similarly, in adult, serum Metrnl is significantly reduced in Graves’ disease and PCOS than in healthy controls.16–18 Interestingly, there are contradictory data regarding circulating Metrnl in T2DM.29 Given the fact that Metrnl alleviates insulin resistance and inflammation, we tried to find the role of Metrnl in MAFLD. Findings from an Australian team indicate that hepatic Metrnl expression of obese patients decrease after bariatric surgery.30 Via the rigorous case-control study, we elucidate that serum Metrnl decreases in patients with MAFLD and negatively correlates with the prevalence of MAFLD, even after adjustment for common risk factors of MAFLD such as WC, FG, blood pressure, γ-GGT, etc. Our data suggest circulating Metrnl might be a protective factor of MAFLD.

NAFLD has a close causal relationship with CAD.31 The present study demonstrated that circulating Metrnl is inversely associated with SBP, DBP, and γ-GGT. In particular, SBP and Creatinine were the independent factors associated with Metrnl. Our data are consistent with the findings from a cross-sectional study in T2DM.32 Several studies have focused on the protective role of Metrnl in CAD.14,33,34 Recent study suggests Metrnl is a therapeutic target against endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis.35 Considering the association of atherosclerosis and blood pressure,36 the inverse correlation between Metrnl and blood pressure can be well explained. Zhou et al37 reported that recombinant Metrnl administration or Metrnl-specific overexpression in the kidney relieves renal injuries in diabetic mice. Here we show serum Metrnl is inversely related to Creatinine, in line with previous result.32 Our data provide a basis for Metrnl to improve kidney disease from clinical data.

Obesity is an important trigger for chronic and low-grade inflammatory status and lipid accumulation directly or indirectly involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD.38,39 Ding, X et al40 evidenced that lower circulating Metrnl concentrations are linked to obesity, and were independently associated with adverse lipid profile. However, Löffler et al41 argued that Metrnl was highly expressed in adipocytes of obese compared to lean children. Similarly, Li et al42 discovered that Metrnl was enhanced in adipose tissue and circulation of obese mice. Contradictory to these findings, no significant correlation was found between serum Metrnl and obesity parameters in our work, which is consist with the results from Zheng and colleagues.43 Collectively, more rigorous experimental designs and larger sample sizes for clinical studies are needed to identify the correlation between circulating Metrnl and obesity parameters. Adipose tissue dysfunction and inflammatory response have a fundamental role during MAFLD development.44 As an inexpensive marker of inflammation used in clinical practice, white blood cell (WBC) serves as a significant predictor for NAFLD.45 Although Metrnl has anti-inflammation effects, we failed to found the association between serum Metrnl and WBC.

Several adipokines such as adiponectin have sex discrepancy. Our data present a significant gender difference in serum Metrnl. Either in the MAFLD group or the normal controls, serum Metrnl was significantly higher in female. We speculate that sex hormones may affect serum Metrnl.

The alarming trend of MAFLD potentially contributes to the burden of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and become the major cause of chronic liver disease in children and adults. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct early screening for MAFLD patients with the highest risk of liver related complications and develop successful management strategies. In clinical practice, people are increasingly paying attention to the non-invasive diagnostic indicators of MAFLD. Adipokines have been identified as diagnostic biomarkers of MAFLD. However, ROC curve in our work indicates that serum Metrnl is not an ideal tool for predicting the incidence of MAFLD.

There are some advantages of our study. This is a rigorous case-control study, with gender and age matched. This study has a large sample size, which reduces the bias caused by grouping. Nevertheless, the current study limited conclusions about casualties and possible associations. Prospective cohort studies conducted through paired biopsies, long-term follow-up, and carefully matched controls can provide higher levels of evidence for the pathophysiological role of adipokines in MAFLD.

We thoroughly assessed the association between circulating Metrnl and MAFLD. In conclusion, serum Metrnl is decreased in MAFLD patients. Our results suggest that Metrnl might be a protective factor correlated with the development of MAFLD. The findings provide new clinical evidences into the mechanism of adipokines in the pathogenesis of MAFLD.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund of Binzhou Medical University (BY2021KYQD032); Scientific Research Initiation Fund of Binzhou Medical University Hospital (2021-05). We express our sincere thanks to all the volunteers and nurses who offered help in the study.

Abbreviations

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FG, fasting glucose; GD, Graves’ disease; HC, hip circumferences; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MAFLD, Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; MS, metabolic syndrome; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NAFL, non-alcoholic fatty liver; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PCOS, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WBC, white blood cell; WC, waist circumference; γ-GGT, γ-gamma glutamyl transferase.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paik JM, Golabi P, Younossi Y, Mishra A, Younossi ZM. Changes in the Global Burden of Chronic Liver Diseases From 2012 to 2017: the Growing Impact of NAFLD. Hepatology. 2020;72(5):1605–1616. doi: 10.1002/hep.31173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machado MV, Diehl AM. Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(8):1769–1777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eslam M, Newsome P, Sarin S, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosekli MA, Kurtkulagii O, Kahveci G, et al. The association between serum uric acid to high density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the abund study. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2021;67(4):549–554. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.20201005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarantino G, Balsano C, Santini SJ, et al. It Is High Time Physicians Thought of Natural Products for Alleviating NAFLD. Is There Sufficient Evidence to Use Them? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13424. doi: 10.3390/ijms222413424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aktas G, Alcelik A, Ozlu T, et al. Association between omentin levels and insulin resistance in pregnancy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2014;122(3):163–166. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1370917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocak MZ, Aktas G, Erkus E, et al. Neuregulin-4 is associated with plasma glucose and increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019;149:w20139. doi: 10.4414/smw.2019.20139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kocak MZ, Aktas G, Atak BM, et al. Is Neuregulin-4 a predictive marker of microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus? Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50(3):e13206. doi: 10.1111/eci.13206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan J, Ding Y, Sun Y, et al. Associations between Adipokines and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease Using Three Different Diagnostic Criteria. J Clin Med. 2023;12(6):2126. doi: 10.3390/jcm12062126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng SL, Li ZY, Song J, Liu JM, Miao CY. Metrnl: a secreted protein with new emerging functions. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(5):571–579. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung TW, Lee SH, Kim HC, et al. METRNL attenuates lipid-induced inflammation and insulin resistance via AMPK or PPARdelta-dependent pathways in skeletal muscle of mice. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(9):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0147-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li ZY, Song J, Zheng SL, et al. Adipocyte Metrnl Antagonizes Insulin Resistance Through PPARgamma Signaling. Diabetes. 2015;64(12):4011–4022. doi: 10.2337/db15-0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadmanesh M, Aghajani H, Fadaei R, Ghorban K. Lower serum levels of Meteorin-like/Subfatin in patients with coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus are negatively associated with insulin resistance and inflammatory cytokines. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alizadeh H. Myokine-mediated exercise effects: the role of myokine meteorin-like hormone (Metrnl). Growth Factors. 2021;39(1–6):71–78. doi: 10.1080/08977194.2022.2032689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong L, Huang G, Weng L, et al. Decreased serum interleukin-41/Metrnl levels in patients with Graves’ disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(10):e24676. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouani FZ, Fadaei R, Moradi N, et al. Circulating levels of Meteorin-like protein in polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deniz R, Yavuzkir S, Ugur K, et al. Subfatin and asprosin, two new metabolic players of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;41(2):279–284. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2020.1758926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du YN, Teng JM, Zhou TH, Du BY, Cai W. Meteorin-like protein overexpression ameliorates fulminant hepatitis in mice by inhibiting chemokine-dependent immune cell infiltration. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44(7):1404–1415. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-01049-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nugent C, Younossi ZM. Evaluation and management of obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4(8):432–441. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang ML, Yang Z, Yang SS. Roles of Adipokines in Digestive Diseases: markers of Inflammation, Metabolic Alteration and Disease Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8308. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez-Cortegana C, Garcia-Galey A, Tami M, et al. Role of Leptin in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7):762. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heydari M, Cornide-Petronio ME, Jimenez-Castro MB, Peralta C. Data on Adiponectin from 2010 to 2020: therapeutic Target and Prognostic Factor for Liver Diseases? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(15):5242. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finelli C, Padula MC, Martelli G, Tarantino G. Could the improvement of obesity-related co-morbidities depend on modified gut hormones secretion? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(44):16649–16664. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otvos L Jr, Shao WH, Vanniasinghe AS, et al. Toward understanding the role of leptin and leptin receptor antagonism in preclinical models of rheumatoid arthritis. Peptides. 2011;32(8):1567–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alizadeh H. Meteorin-like protein (Metrnl): a metabolic syndrome biomarker and an exercise mediator. Cytokine. 2022;157:155952. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2022.155952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmid A, Karrasch T, Schaffler A. Meteorin-Like Protein (Metrnl) in Obesity, during Weight Loss and in Adipocyte Differentiation. J Clin Med. 2021;10(19):4338. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moradi N, Fadaei R, Roozbehkia M, et al. Meteorin-like Protein and Asprosin Levels in Children and Adolescents with Obesity and Their Relationship with Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome. Lab Med. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao ZW, Hu WJ, Li ZY, Miao CY. Involvement of the secreted protein Metrnl in human diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(12):1525–1530. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-00529-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grander C, Grabherr F, Enrich B, et al. Hepatic Meteorin-like and Kruppel-like Factor 3 are Associated with Weight Loss and Liver Injury. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022;130(6):406–414. doi: 10.1055/a-1537-8950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren Z, Simons P, Wesselius A, Stehouwer CDA, Brouwers M. Relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2023;77(1):230–238. doi: 10.1002/hep.32534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung HS, Hwang SY, Choi JH, et al. Implications of circulating Meteorin-like (Metrnl) level in human subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2018;136:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu ZX, Ji HH, Yao MP, et al. Serum Metrnl is associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(1):271–280. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferns GA, Fekri K, Shahini Shams Abadi M, Banitalebi Dehkordi M, Arjmand MH. A meta-analysis of the relationship between serums metrnl-like protein/subfatin and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2021;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng S, Li Z, Song J, et al. Endothelial METRNL determines circulating METRNL level and maintains endothelial function against atherosclerosis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(4):1568–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegler MG. Atherosclerosis and Blood Pressure Variability. Hypertension. 2018;71(3):403–405. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y, Liu L, Jin B, et al. Metrnl Alleviates Lipid Accumulation by Modulating Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes. 2023;72(5):611–626. doi: 10.2337/db22-0680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu H, Ballantyne CM. Skeletal muscle inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(1):43–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI88880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu H, Ballantyne CM. Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Circ Res. 2020;126(11):1549–1564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding X, Chang X, Wang J, et al. Serum Metrnl levels are decreased in subjects with overweight or obesity and are independently associated with adverse lipid profile. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:938341. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.938341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loffler D, Landgraf K, Rockstroh D, et al. METRNL decreases during adipogenesis and inhibits adipocyte differentiation leading to adipocyte hypertrophy in humans. Int J Obes Lond. 2017;41(1):112–119. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li ZY, Zheng SL, Wang P, et al. Subfatin is a novel adipokine and unlike Meteorin in adipose and brain expression. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20(4):344–354. doi: 10.1111/cns.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C, Pan Y, Song J, et al. Serum Metrnl Level is Correlated with Insulin Resistance, But Not with beta-Cell Function in Type 2 Diabetics. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:8968–8974. doi: 10.12659/MSM.920222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuster S, Cabrera D, Arrese M, Feldstein AE. Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(6):349–364. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0009-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S, Zhang C, Zhang G, et al. Association between white blood cell count and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in urban Han Chinese: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010342. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]