Abstract

Introduction:

Despite high cost and wide prevalence of PTSD in veteran populations, and Veterans Health Administration (VA)-wide mental health provider training in evidence-based treatments for PTSD, most veterans with PTSD do not receive best practices interventions. This may be because virtually all evidence-based PTSD treatment is offered through specialty clinics, which require multiple steps and referrals to access. One solution is to offer PTSD treatment in VA primary care settings, which are often the first and only contact point for veterans.

Methods:

The present study Improving Function Through Primary Care Treatment of PTSD (IMPACT) used a randomized controlled design to compare an adaptation of Prolonged Exposure for PTSD to primary care (PE-PC) vs best practices Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) clinic Treatment as Usual (TAU) in terms of both functioning and psychological symptoms in 120 Veterans recruited between April 2019 and September 2021.

Results:

Participants were mostly males (81.7%) with mean age of 43.6 years (SD=12.8), and more than half were non-White veterans (50.8%). Both conditions evinced significant improvement over baseline across functioning, PTSD, and depression measures, with no differences observed between groups. As observed in prior studies, PTSD symptoms continued to improve over time in both conditions, as measured by structured clinical interview.

Discussion:

Both PE-PC and best-practices TAU are effective in improving function and reducing PTSD severity and depression severity. Although we did not observe differences between two treatments, note that this study site and 2 PCMHI clinics employs primarily cognitive behavioral therapies (e.g., exposure, behavioral activation).

Keywords: primary care, posttraumatic stress disorder, treatment, behavioral health, exposure therapy

Introduction

PTSD remains a high-cost illness, and evidence-based treatments for PTSD could improve function and greatly reduce service costs by about $86.2 million (Mueller et al., 2019; Watkins et al., 2011). Veterans Health Administration (VA) has invested in training and disseminating effective PTSD interventions, but most veterans do not access first-line treatments (Maguen et al., 2020). PTSD interventions typically occur in specialty mental health clinics, contributing to reduced use when veterans do not follow referral required to access specialty care (Possemato et al., 2018). Although VHA has implemented screening for PTSD in primary care (PC), no wide-spread, PC-based PTSD psychotherapeutic intervention has been implemented (VA/DOD, 2017). These difficulties in accessing effective PTSD intervention are exacerbated for rural and non-White Veterans suggesting additional resources and care models are needed (Gross et al., 2021; Grubbs et al., 2017).

Prolonged Exposure for Primary Care (PE-PC), a brief PTSD therapy emphasizing trauma exposure, was developed to address this gap. In a randomized clinical trial (RCT) in military facilities, PE-PC demonstrated significantly greater reduction in PTSD than minimal attention control, and half of those with a diagnosis of PTSD at baseline who received PE-PC no longer met PTSD criteria six months posttreatment (Cigrang et al., 2017). The study team adapted PE-PC for the VA Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) setting and developed a training program for VA PCMHI providers (Rauch et al., 2020). PCMHI is a Primary Care Behavioral Health model specific to the VA setting. PE-PC is typically provided in a co-located collaborative care model where embedded behavioral health providers deliver brief treatment as part of the PC team. Of note, for the study recruitment site, referrals to specialty care where evidence-based PTSD treatments are readily available is detailed in intervention descriptions.

The present study, Improving Function Through Primary Care Treatment of PTSD (IMPACT), is the first RCT of PE-PC in the VA and evaluates improvement in functional and symptoms in veterans with PTSD and/or subsyndromal PTSD presenting for treatment in VA PCMHI clinics. We randomized eligible participants to receive either PE-PC or treatment as usual (TAU). If PE-PC effectively reduces disability and PTSD symptoms, this intervention may provide a more widely available access point for effective PTSD care resulting in greater numbers of veterans obtaining treatment. As reported in our detailed methods article (Rauch et al., 2022), we hypothesized that PE-PC would result in larger reductions in disability (i.e., improvements in functioning) than best practices PCMHI-TAU (Week 0 to Week 6), and these differences would remain at 12- and 24-weeks post-baseline. We hypothesized that PE-PC would result in larger reductions in PTSD severity and in depression severity than PCMHI-TAU (Week 0 to Week 6), and that these differences would remain at 12- and 24-weeks post-baseline. We assessed combat experience severity as a potential moderator of improvements in function and PTSD symptoms in an exploratory analysis.

Methods

Study Design

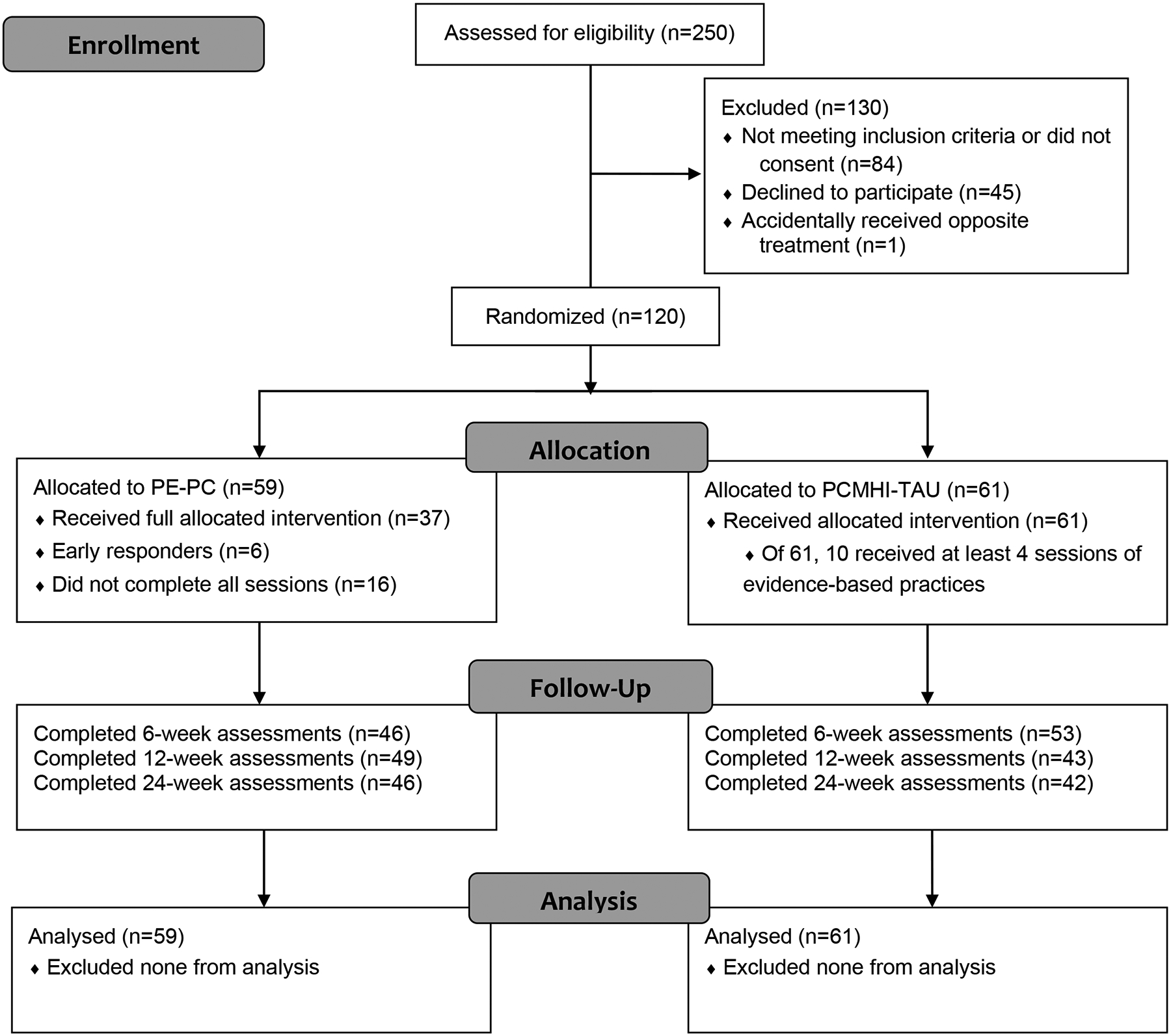

Details on the study design and methods appear in the previously published methods article (Rauch et al., 2022). See Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram. Authors complied with APA ethical standards and human subject committees for all sites approved the study protocol. All veterans were consented prior to study procedures. Between April 2019 and September 2022, we randomized veterans (N = 120) who presented in VA PCMHI at two VA clinics in the Southeast US serving both rural and urban populations with chronic PTSD symptoms [PTSD Symptom Checklist for DSM5 (Bovin et al., 2016) PCL-5 ≥ 28] and met inclusion/exclusion criteria to receive PE-PC or PCMHI-TAU. Inclusion criteria were: 1) any era veteran with PCL-5 ≥ 28 seeking care for PTSD in VA PCMHI, 2) age 18–70, 3) English speaking, 4) significant functional impairment on WHODAS (≥3 in any of the six domains). Exclusion criteria were: 1) other primary clinical issue that would interfere with PTSD treatment, 2) level of suicidal risk that requires intervention based on Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, 3) severe cognitive impairment, 4) psychosis or unmanaged bipolar disorder, 5) moderate to severe substance use disorder in the past 8 weeks, 6) currently receiving talk therapy for trauma- related symptoms. We asked participants meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria to maintain medications at current dosages when medically appropriate. If a new medication started within 2 weeks, we asked patients to wait 2 weeks prior to baseline assessment.

Figure 1:

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Veterans completed baseline (week 0) and follow-up assessments at weeks 6 (post), 12, and 24 that included interview and self-report measures. We used total score of WHODAS 2.0 (Axelsson et al., 2017) as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included CAPS-5 (Weathers et al., 2018) and PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001). WHODAS 2.0 and CAPS-5 were assessed by trained, independent evaluators who remained blinded to treatment condition; we assessed inter-rater reliability of evaluators, who completed recalibration twice per year.

Participants

We enrolled 120 veterans who received randomized treatments [best practices PCMHI-TAU (n=61) or PE-PC (n=59, Figure 1)]. Demographic and clinical characteristics appear in Table 1 by treatment group. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups. Participants were mostly males (81.7%) with mean age of 43.6 years (SD=12.8), and more than half were non-White veterans. Target traumas included 51% combat trauma, 9.5% sexual trauma, 8.8% other military trauma, and 30.6% other traumas. Baseline WHODAS-36 as measured by item-response theory summary score had a mean of 47.4 (SD=17.1), with lowest mean of 21.7 (SD=22.2) in the Self-care domain indicating this domain showed the highest function, and highest mean of 59.7 (SD=20.9) in the Participation domain indicating lowest function, with negative impact on one’s health problems on self and one’s family. A total of 17 (14%) enrollees did not complete any follow-up assessments. Follow-up assessment rates at 6, 12, and 24 weeks were 82.5%, 76.7%, and 73.3% and did not differ by treatment groups. There were no baseline characteristics that predicted missing week 6 outcomes (primary endpoint).

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Enrollees by Treatment Group

| TAU N = 61 (50.8%) |

PE-PC N = 59 (49.2%) |

Total N = 120 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.7 (14.0) | 44.6 (11.6) | 43.6 (12.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 46 (75.4%) | 52 (88.1%) | 98 (81.7%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 26 (42.6%) | 26 (44.1%) | 52 (43.3%) |

| Black | 30 (49.2%) | 31 (52.5%) | 61 (50.8%) |

| Other1 | 5 (8.2%) | 2 (3.4%) | 7 (5.8%) |

| Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity2, n (%) | 5 (8.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | 6 (5.2%) |

| Married, n (%) | 38 (62.3%) | 36 (61.0%) | 74 (61.7%) |

| Education3, n (%) | |||

| High School (or equivalent) | 11 (18.9%) | 10 (17.2%) | 21 (17.7%) |

| Some College (13–15 years) | 29 (47.5%) | 30 (51.7%) | 59 (49.6%) |

| Bachelor’s or Above (16+) | 21 (34.4%) | 18 (31.0%) | 39 (32.8%) |

| OIF/OEF/OND Service, n/N (%) | |||

| Served in Iraq | 17/47 (36.2%) | 23/51 (45.1%) | 40/98 (40.8%) |

| Served in Afghanistan | 17/51 (33.3%) | 16/48 (33.3%) | 33/99 (33.3%) |

| Served in Both post 9/11/2001 | 12/46 (26.1%) | 13/48 (27.1%) | 25/94 (26.6%) |

| Measures (possible range), mean (SD) | |||

| Combat Experiences Scale (1–7) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.0) |

| Credibility (standardized) | 0.04 (.85) | −0.04 (0.91) | −0.00 (0.88) |

| Expectation (standardized) | 0.03 (0.83) | −0.03 (0.93) | −0.00 (0.88) |

| WHODAS 2.0 36-item Raw Mean (0–4) | 1.66 (0.61) | 1.77 (0.71) | 1.71 (0.66) |

| WHODAS 2.0 36-item Item Response4 (0–100) | 46.7 (16.1) | 48.8 (18.1) | 47.7 (17.1) |

| Cognition Domain (0–100) | 43.0 (17.0) | 43.2 (21.0) | 43.1 (19.0) |

| Mobility Domain (0–100) | 38.3 (26.8) | 43.0 (25.6) | 40.6 (26.2) |

| Self-care Domain (0–100) | 18.9 (20.1) | 25.6 (24.1) | 21.7 (22.2) |

| Getting along Domain (0–100) | 56.8 (24.1) | 58.1 (26.1) | 57.4 (25.0) |

| Life Activities – Household Domain (0–100) | 49.5 (25.6) | 56.8 (25.4) | 53.1 (25.6) |

| Life Activities – Work Domain (0–100) | 48.2 (28.5) | 47.4 (25.7) | 57.9 (27.1) |

| Participation (0–100) | 60.0 (19.4) | 59.4 (22.5) | 59.7 (20.9) |

| CAPS-5 Total (3–59) | 34.1 (9.3) | 34.0 (8.8) | 34.0 (9.0) |

| PHQ-9 Total (0–27) | 15.0 (5.5) | 14.1 (5.1) | 14.6 (5.3) |

| PCL-5 Total (0–80) | 50.9 (13.0) | 49.4 (11.6) | 50.1 (12.3) |

Abbreviations: TAU is treatment as usual; PE-PC is Prolonged Exposure Primary Care; SD = standard deviation; OIF=Operation Iraqi Freedom; OEF=Operation Enduring Freedom; OND=Operation New Dawn; CAPS5=Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (30 items); WHODAS=World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (36 items); PHQ=Patient Health Questionnaire (9 items); PCL-5=PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (20 items).

Note: None showed statistically significant (p<0.05) differences.

Includes Asian, unknown, Hawaiian, American Indian, Alaskan and multiracial.

Excluded those reporting unknown ethnicity (3 in TAU and 2 in PE-PC).

Excluded one PE-PC participant whose response was ‘prefer not to answer”.

36 item summary; if 4 remunerated work items are not applicable, then 32 item score is used.

Interventions

Prolonged Exposure for Primary Care (PE-PC).

Four PCMHI providers (social workers, psychologist and/or licensed professional counselors) conducted in person or via telehealth PE-PC in 4 to 6, 30-minute appointments scheduled approximately once per week over 4–6 weeks (to accommodate scheduling and missed appointments). PE-PC includes: target trauma exposure in a written format; in vivo exposure to avoided people, places, and situations; and processing of exposure in written format and in sessions with a PCMHI provider (Rauch et al., 2020). All veterans received 6 visits unless they met the early response criteria (i.e., PCL-5 score of 20 or lower in visit 4 or 5). Providers completed the PE-PC training program (4-hour didactic training and 6 months of 30-minute weekly consultation calls). Treatment followed the PE-PC manual and veteran workbook (Cigrang et al., 2017). PE-PC providers did not conduct best-practices TAU.

Treatment As Usual (TAU).

PCMHI providers who were not PE-PC study providers administered TAU, an active treatment which at these clinics followed best-practices standard of care and could include medication, brief CBT in PCMHI (e.g., for depression, insomnia) or referral to specialty mental health to be seen within two weeks, for trauma focused therapy. One patient assigned to TAU received PE-PC in error and was withdrawn from study analyses but continued in clinical care. TAU providers did not conduct PE-PC. Of note, wait times for PTSD specialty care in this facility are reduced relative to the norm for VA (i.e., less than 2 weeks).

Provider Fidelity

All providers attended weekly ongoing supervision for PE-PC led by the study site PI (BW) for the duration of the trial to ensure provider competence and fidelity. In addition, a trained fidelity evaluator reviewed and rated a randomly selected 10% of visit recordings. Recordings were rated on three factors: (1) Essential Elements, (2) Essential but not Unique Elements, (3) Adherence. Therapists completed 93% of the Essential Elements with an average adequacy rating on a scale of 0 to 5 of 4.6; 100% of the Essential but not Unique Elements with an average adequacy rating on a scale of 0 to 5 of 4.7; 100% of the Adherence Questions with an average adequacy rating on a scale of 0 to 5 of 4.6.

Measures

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule [WHODAS 2.0 (Axelsson et al., 2017)].

The WHODAS is a 36-item disability assessment covering six domains of function: cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities and participation. Scores range from 0 (no disability) to 100 (full disability) with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment. WHODAS has high overall internal consistency (α = .96) and test- retest reliability (r = 0.98). Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.93.

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale-5 [CAPS-5 (Weathers et al., 2018)].

The CAPS-5 is an interview measure of PTSD severity assessed in relation to a target trauma. CAPS-5 has high overall internal consistency (α = .88) and adequate test- retest reliability (r = 0.83) with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD.

PTSD Checklist – Stressor-Specific Version [PCL-5(Bovin et al., 2016; Marx et al., 2022)].

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure of past month PTSD severity. The PCL-5 has high overall internal consistency (α = .96) and adequate test- retest reliability (r = 0.84) with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD. Within our sample Chronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 [PHQ-9(Kroenke et al., 2001)].

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item measure of past two weeks depression severity. The PHQ-9 detects treatment changes in depression in PC settings and has excellent internal and test-retest reliability and high overall internal consistency (α = .89) and adequate test-retest reliability (r = 0.84) with higher scores indicating more severe depression. Within our sample Chronbach’s alpha was 0.82.

Combat Experiences Scale [CES(Keane et al., 1989)].

The CES is a seven-item measure of combat exposure severity. CES total scores range from 0 to 41 with reported good reliability with higher scores indicating more exposure to combat.

Remission and Response.

We defined remission as CAPS-5 below 20 (Hinton et al., 2021) and response as 10 point or larger reduction in CAPS-5 per the National Center for PTSD interpretation standards (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp).

Treatment Drop and Missing Data.

We used an intent-to-treat approach and continued to assess participants regardless of treatment completion to reduce missingness to a minimum. For missing items within scales, we used recommended imputation procedures.

Statistical Analysis

Study design enrolled 120 patients (60 per group) for 80% power to detect a meaningful difference of 0.54 standardized effect size in WHODAS total score at 6 months with 0.05 two-sided tests assuming about 10% lost-to-follow-up. We examined baseline variables between PE-PC and PCMHI-TAU groups for comparability. Potential covariates or confounding variables included military era (Vietnam, Persian Gulf, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)/Operation New Dawn (OND)), baseline function, baseline PTSD and depression severity, and demographic characteristics (males, non-white veterans).

Main analyses compared effectiveness and maintenance of function between PE-PC and PCMHI-TAU on the WHODAS. We defined effectiveness as significant improvement at week 6 and assessed maintenance at weeks 12 and 24. We first visualized the trends in outcomes between two groups over time and used a mixed model with WHODAS total scores (using both 36-item raw mean and item response summary score) at weeks 0, 6, 12 and 24 as the dependent variable to model the trends in outcomes in the two groups. Mixed models permit flexible specification of the covariance matrix of the repeated measures and give unbiased estimate with incomplete data assuming missingness at random. We included random intercepts in the model for participants and adjusted for study clinic, age and sex, and potential confounding patient characteristics identified in baseline analysis. Primary predictors included PE-PC group indicator, categorical time indicators (with week 0 as the referent time), and interactions of treatment group by time indicators. We first assessed for differential improvement across follow-up times between treatment groups based on a likelihood ratio test (LRT) for the significance of the 3 degrees of freedom interaction terms. We prespecified to estimate and compare improvement at week 6 relative to baseline between treatment groups (effectiveness) and at 12 and 24 weeks (for maintenance) based on the model coefficients and contrasts of the coefficients. We also specified to test for a drop in function from week 6 to 12 and from week 6 to 24 within PE-PC group for loss in initial gain (another type of maintenance). Upon finding no differential PE-PC effect across follow-up times both graphically and based on a LRT, we fit a simpler mixed model with PE-PC group indicator, a post randomization time indicator, and their interactions and tested if the time-averaged PE-PC effect during weeks 6 to 24 was significant based on the coefficient of the interaction term. Lastly, when we found that time-averaged PE-PC effect during weeks 6 to 24 was not significant, we further simplified the model by dropping the interaction term and estimated the coefficient of the post randomization time indicator as the time-averaged combined treatment effect during weeks 6 to 24.

For each secondary outcome measure [PTSD severity (CAPS and PCL-5) and depression severity], we also tested if between-group changes in symptoms differed across follow-up weeks using similar analytic steps for WHODAS. We also compared the proportion of veterans remitted from PTSD (CAPS-5<20) and the proportion with treatment response (10-point decrease in CAPS-5) between groups at week 6, 12, and 24 based on a generalized linear mixed model with a logit link with the dependent variable of remission at 6, 12 and 24 weeks. Primary predictors included the PE-PC group indicator, indicators for week 12 and for week 24, and the interactions of follow-up time indicators by treatment group. We used a 2 degrees of freedom LRT for significant interaction coefficients, i.e., to test if the relative odds of remission between the two groups differed across the follow-up times, adjusting for study clinic. When we found no differential proportions between groups, we reported remission and response combined across groups at each follow-up time with their confidence intervals. We explored CES as a potential moderator to assess if the treatment effect differed by the level of the CES. We repeated analysis after excluding the control (PCMHI-TAU) participants who used at least 4 sessions of evidence-based practices during the first six weeks to examine if it explained improvement in function or symptoms, which might have reduced differential effects.

Results

In PE-PC, 43 (72.9%) participants completed PE-PC sessions including six early responders (determined by change in PCL-5 score), and 16 (27%) participants were not early responders but dropped out of PE-PC. Excluding those who had PCL reductions qualifying them as “early completers,” 97%, 88%, 80%, 73%, 70%, and 68% completed session 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively.

In PCMHI-TAU among those who received therapy, only 22% received therapy in PCMHI. Specialty mental health therapy occurred through referrals as standard of care. Ten participants received at least 4 sessions of an evidence based cognitive behavioral therapy that most often included referral to specialty mental health where they received many interventions including PE, CPT, CBT for insomnia, CBT for depression and others.

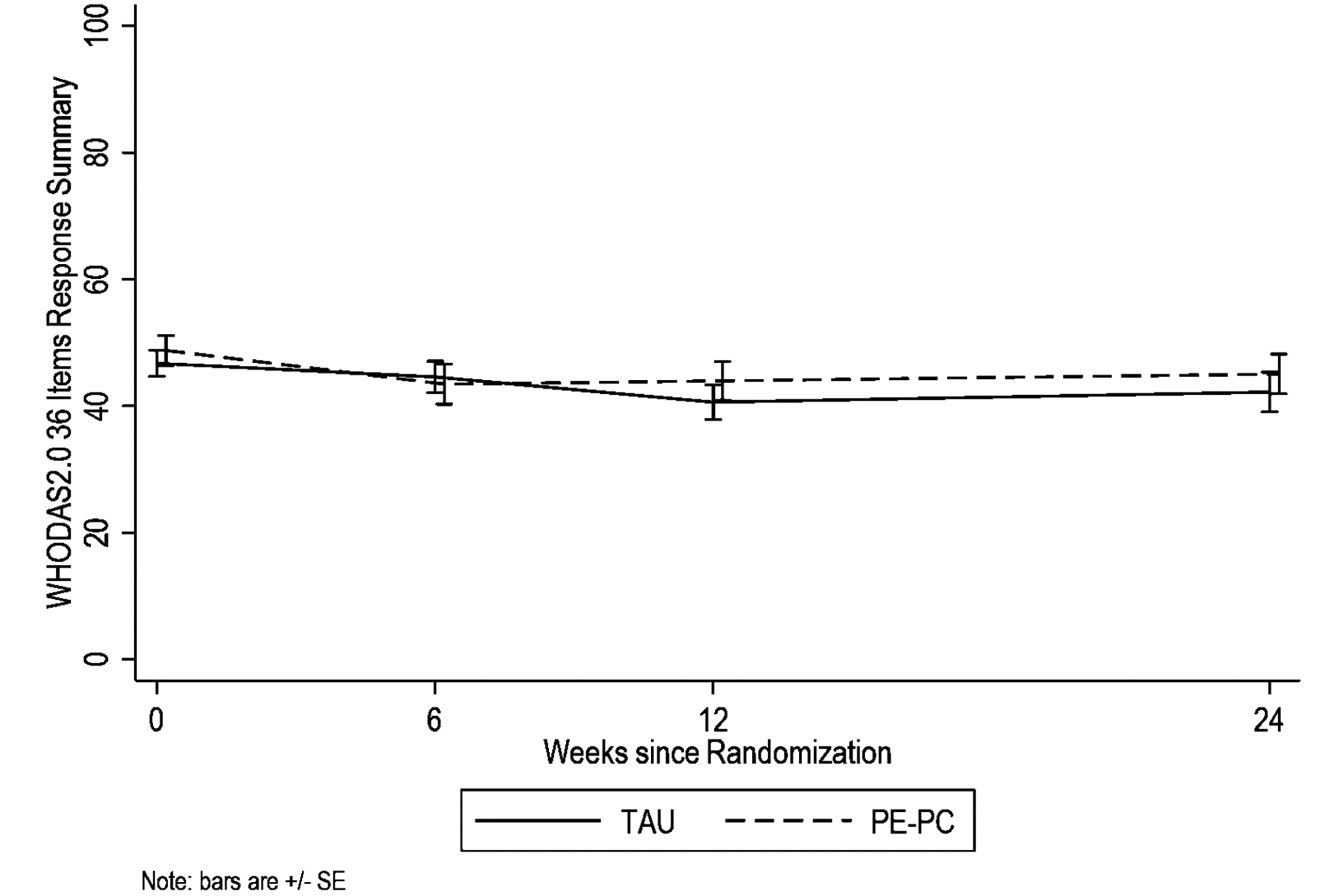

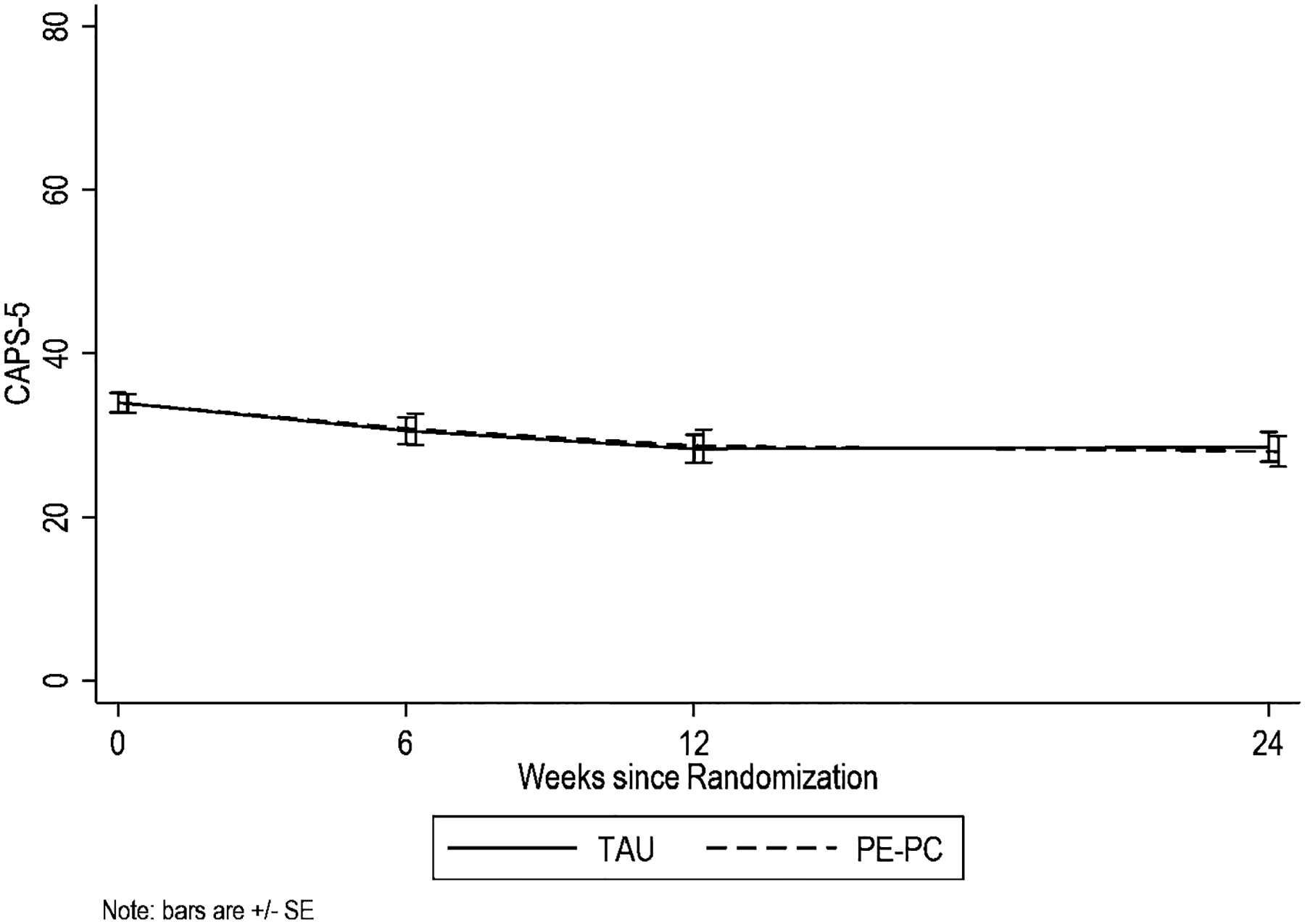

None of the primary (WHODAS) and secondary outcome measures (CAPS-5, PHQ-9, and PCL-5) showed differential improvement across follow-up times between treatment groups (Table 2). Figures 2 and 3 illustrate these changes over the six months of the study. Specifically, overall function as measured by WHODAS-36 summary score showed means to significantly drop from 46.7 at baseline to 44.6, 40.6, and 42.2 in PCMHI-TAU and from 48.8 at baseline to 43.5, 44.0, and 45.1 in PE-PC at weeks 6, 12 and 24, respectively, with no significant difference between groups in changes from baseline based on LRT for the interaction terms (χ2df= 3=0.63, p=.89). Results based on WHODAS domain scores (e.g., Getting Along domain) and other symptom measures (e.g., CAPS-5) showed similar results with significant reduction from baseline on most measures and no differential changes from baseline between groups.

Table 2:

Cross-sectional Raw Means of the Four Outcome Measures by Treatment Group and Test of Treatment Group by Time1

| Weeks since Randomization | Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Group | 0 | 6 | 12 | 24 | (p-value)1 |

| WHODAS Raw Mean (0–4) | TAU | 1.66 (0.61) | 1.58 (0.67) | 1.43 (0.67) | 1.50 (0.78) | 0.50 |

| PE-PC | 1.77 (0.71) | 1.56 (0.80) | 1.58 (0.80) | 1.61 (0.82) | (0.92) | |

| WHODAS 36-item Summary | TAU | 46.7 (16.1) | 44.6 (17.7) | 40.6 (17.4) | 42.2 (20.3) | 0.63 |

| PE-PC | 48.8 (18.1) | 43.5 (20.9) | 44.0 (21.2) | 45.1 (21.3) | (0.89) | |

| WHODAS Getting Along | TAU | 56.8 (24.1) | 52.7 (27.2) | 49.0 (23.4) | 49.2 (28.7) | 1.54 |

| PE-PC | 58.1 (26.1) | 53.3 (31.6) | 54.3 (31.9) | 56.2 (27.8) | (0.67) | |

| WHODAS LA – Household | TAU | 49.5 (25.6) | 50.2 (30.2) | 44.3 (27.6) | 48.8 (26.8) | 3.36 |

| PE-PC | 56.8 (25.4) | 47.4 (27.6) | 50.0 (28.0) | 49.4 (27.1) | (0.34) | |

| WHODAS LA - Work | TAU | 48.3 (28.5) | 43.7 (24.2) | 41.0 (24.0) | 46.6 (29.3) | 0.30 |

| PE-PC | 47.4 (25.7) | 43.8 (26.9) | 46.4 (26.3) | 41.9 (26.7) | (0.96) | |

| CAPS-5 Total (3–59) | TAU | 34.1 (9.3) | 30.6 (11.6) | 28.4 (11.2) | 28.6 (11.8) | 0.00 |

| PE-PC | 34.0 (8.8) | 30.8 (12.7) | 28.8 (14.0) | 28.1 (12.7) | (0.99) | |

| PHQ-9 Total (0–27) | TAU | 15.1 (5.5) | 12.8 (5.8) | 12.8 (5.9) | 12.2 (6.0) | 2.94 |

| PE-PC | 14.1 (5.1) | 12.8 (7.0) | 12.5 (6.8) | 13.1 (6.6) | (0.40) | |

| PCL-5 Total (0–80) | TAU | 50.9 (13.0) | 45.3 (13.1) | 40.2 (15.6) | 40.5 (16.6) | 1.46 |

| PE-PC | 49.4 (11.6) | 43.1 (21.6) | 41.1 (20.4) | 42.1 (20.5) | (0.69) | |

Abbreviation: TAU is treatment as usual; PE-PC is Prolonged Exposure Primary Care; WHODAS=World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (36 items); LA is life activities; CAPS5=Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (30 items); WHODAS=World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (36 items); PHQ=Patient Health Questionnaire (9 items); PCL-5=PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (20 items).

Note: Cell values are mean (SD). N of respondents at weeks 0, 6, 12 and 24 were 61, 50, 42, and 42 in TAU group, and 59, 43, 48, 46 in PE-PC group, respectively, for CAPS-5 and WHODAS 2.0.

Likelihood ratio test χ2 statistic based on a mixed model with outcomes at all assessment times and testing for significance of the 3 degrees of freedom interactions of PE-PC group by follow-up time indicators for differential treatment effects over three follow-up times. The model also included random intercepts for participants, time as categorical indicators, treatment group indicator, age, sex, and location as fixed effects.

Figure 2.

WHODAS 2.0 Across Treatment and 6 Month Follow-up

Figure 3.

CAPS-5 Across Treatment and 6 Month Follow-up

As PE-PC and PCMHI-TAU did not differ in improvement on primary and secondary outcomes (described above), we estimated effectiveness averaged across groups at each follow-up (Table 3). Across treatment groups, function improved/disability reduced significantly at week 6 with predicted mean reduction in WHODAS of −3.7 points (p=0.006; standardized change=0.31), and improvement was maintained at week 12 (p=0.60) and week 24 (p=0.66). PTSD and depression symptoms were also significantly reduced from baseline to week 6 [CAPS-5 = −2.9 (p=.002; standardized change=0.35); PCL-5 = −5.8 (p<.001; standardized change=0.46); PHQ-9 = −1.4 (p=.005; standardized change=0.28)]. For PCL-5 and PHQ-9, improvement from baseline seen at week 6 was maintained at week 12 and 24. On the other hand, CAPS-5 showed further improvement in PTSD symptoms at weeks 12 and 24 from week 6 as evidenced by a significant difference in predicted mean changes between weeks 6 and 12 (p=0.02) and between weeks 6 and 24 (p=0.003). For outcomes showing no difference across three follow-up times in predicted mean changes from baseline, we estimated time-averaged mean change from baseline based on the parameter estimate of the post-baseline time indicator (all follow-up times vs. baseline) from fitting a mixed model with random intercepts for each participant, adjusting for intervention group, age, sex, and clinic (last column of Table 3).

Table 3:

Predicted Mean Changes (95% confidence intervals) from Baseline at Each Follow-up Time Averaged across Treatment Groups1 and Time-Averaged Predicted Mean Change2; For All Measures, Negative Mean Changes Imply Improvement.

| Outcome Variables | Time-averaged2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 61 | Week 121 | Week 241 | Treatment Effect | |

| WHODAS Raw Mean | −0.1 (−0.2, −0.04) | −0.2 (−0.3, −0.07) | −0.2 (−0.3, −0.06) | −0.2 (−0.2, −0.08) |

| WHODAS 2.0 36-item Summary | −3.7 (−6.4, −1.1) | −4.5 (−7.2, −1.8) | −4.4 (−7.1, −1.6) | −4.2 (−6.3, −2.0) |

| WHODAS Getting Along | −3.8 (−8.0, 0.4) | −4.1 (−8.3, 0.2) | −4.4 (−8.7, −0.1) | −4.1 (−7.5, −0.7) |

| WHODAS Life Activities Household | −4.4 (−8.9, 0.1) | −4.9 (−9.5, −0.4) | −4.0 (−8.6, 0.6) | −4.4 (−8.0, −0.8) |

| WHODAS Life Activities Work | −3.7 (−8.6, 1.2) | −1.4 (−6.3, 3.6) | −4.2 (−9.3, 0.8) | −3.1 (−7.0, 0.9) |

| CAPS-5 | −2.9 (−4.6, −1.1) | −5.1 (−6.9, −3.3) | −5.7 (−7.5, −3.9) | --3 |

| PHQ-9 | −1.4 (−2.4, −0.4) | −1.4 (−2.4, −0.4) | −1.5 (−2.5, −0.5) | −1.5 (−2.3, −0.7) |

| PCL-5 | −5.8 (−8.4, −3.1) | −8.0 (−10.7, −5.3) | −8.2 (−10.8, −5.5) | −7.3 (−9.4, −5.2) |

Abbreviation: TAU is treatment as usual; PE-PC is Prolonged Exposure Primary Care; WHODAS=World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (36 items); LA is life activities; CAPS5=Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (30 items); WHODAS=World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (36 items); PHQ=Patient Health Questionnaire (9 items); PCL-5=PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (20 items).

Parameter estimate of each categorical time indicator based on a mixed model with random intercepts for participants and with categorical time indicators, adjusting for intervention group, age, sex, and clinic. In bold, p > .05.

Predicted change from baseline averaged across follow-up times and group. They are reported only if no difference in predicted mean changes from baseline across the three follow-up times is shown, i.e., no significant difference in categorical time effects. They are estimated from the parameter estimates of the post-baseline time indicator (all follow-up times vs. baseline) based on a mixed model with intervention group, post-baseline time indicator, age, sex, and clinic, and with random intercepts for participants.

For CAPS-5, further symptom improvement from week 6 was seen at weeks 12 (p=0.02) and 24 (p=0.003) in the combined treatment groups.

The proportion of veterans with PTSD symptom remission (CAPS-5 < 20) during follow-up did not show significant difference between groups at weeks 6, 12 and 24 (χ2df=2=2.52; p=0.28). Collapsed across groups, remission was 17.2% (95% CI=10.9%, 26.0%) at week 6, 23.9% (95% CI=16.2%, 33.8%) at week 12, and 22.7% (95% CI=15.1%, 32.8%) at week 24. Although slightly increased, remission collapsed across groups was not different between weeks 12 vs. 6 (p=0.07) and between weeks 24 vs. 6 (p=0.14). The proportion of veterans with treatment response (CAPS-5 improvement > 10) during follow-up times also did not show differences between groups at weeks 6, 12 and 24 (χ2df=2=4.38; p=0.11). Collapsed across groups, 19.4% (95% CI=12.5%, 28.8%) responded at week 6 and increased significantly to 32.2% (95% CI=23.3%, 42.7%; p=0.004) at week 12 and 34.1% (95% CI=24.9%, 44.7%; p=0.002) at week 24. Recent research suggests 8 points or larger CAPS-5 reduction may better capture response and no differences in results were found with the 8-point criterion (Marx et al., 2022).

We explored if improvements in function and PTSD symptoms differed by CES within each treatment group and across groups and found the magnitude of improvements did not vary by CES. We repeated the between-group comparison excluding the 10 PCMHI-TAU participants who received at least 4 CBT sessions and did not find between-group differences in differential changes in function or PTSD symptoms (Supplementary Table 1). All results remained substantively similar.

Discussion

Previous research supported the efficacy of PE-PC in reducing PTSD symptoms compared to minimal attention control (Cigrang et al., 2017). The current study examined whether this brief intervention provided in PC improved function and reduced symptoms of PTSD and related mental health problems in veterans and compared the reductions to current best practices PCMHI-TAU in VA settings. Both PE-PC and PCMHI-TAU as provided in the selected clinics, reduced disability (i.e., improved function) and improved mental health symptoms, including PTSD and depression, with no significant differences between the two active conditions. Only one study has examined change in WHODAS among Veterans receiving PTSD treatment and it included Veterans in a specialty PTSD outpatient clinic as well as a residential setting receiving cognitive processing therapy (Schumm et al., 2017). As expected, changes in WHODAS in the current study are notable, though slightly smaller than those found in the more time intensive models provided to populations with generally higher impairment. Of note, caution must be used when comparing interventions and studies conducted in different patient populations (such as PC versus specialty mental health), as patients likely have different levels of impairment, investment in treatment, and knowledge and familiarity with mental health treatments that can significantly impact results. Both trauma-focused PE-PC and PCMHI TAU, which varied widely and included interventions for PTSD for some and targeted other concerns (e.g., insomnia, depression) for others, were related to remission that was sustained for a portion of veterans. Specifically, at 12 weeks 23.9% and at 24 weeks 22.7% of veterans reported remission of PTSD. Thus, these treatments are effective for some and others require additional intervention.

Increasing veteran access to effective PTSD treatment represents a priority for VHA, and treatment in PC can accelerate access to care. In addition, avoidance is a hallmark of PTSD. Providing quick access to effective treatment when PTSD is first identified or when the veteran first considers treatment can prevent some barriers to care and potentially increase retention and overall population outcomes. The current study found that both PE-PC and PCMHI-TAU provided clinical benefits to veterans with PTSD who received care in PCMHI. This is excellent news for PCMHI providers and veterans who now have both trauma-focused (PE-PC) and standard PCMHI options for care.

Simplified versions of effective interventions can provide a springboard for implementation in new settings and modes of care. As we have developed PE-PC, additional work on other brief exposure formats and self-guided formats have also been ongoing (McLean et al., 2021; Sloan et al., 2018). The expected mechanisms of exposure therapy remain the same, though the intervention is provided in a manner that patients can access more easily and even independently. Bringing effective treatment into new settings can transform how veterans and others with PTSD access care, providing additional avenues to response and remission. These additional options may also address the mental health provider shortage by allowing lighter touch interventions that require less provider time. Although such modifications represent important steps for the field, ensuring that these new models of care provide adequate effectiveness remains critical. The current study supports PE-PC as an accessible effective treatment option for VA PCMHI.

Of note, the study utilized a rigorous control condition. The recruitment site with two clinics has been conducting PTSD focused treatment research for over 20 years, has accessible PTSD specialty care with typical wait of two weeks or less, and has high-quality EBP-focused PCMHI-TAU. To have each of these characteristics is uncommon and all three is rare. Previous review of PCMHI in VA found that usual PCMHI care for PTSD was primarily medication management and supportive therapy with referral to specialty mental health (Possemato et al., 2011). Thus, the PCMHI-TAU in the current study may not represent “standard” PCMHI at other VA facilities where referral wait times for PTSD specialty services typically exceed 2 weeks and practices may vary.

We note some study limitations. Additional examination of heterogeneity of response or who will most likely complete treatment and who is most likely to respond to PE-PC and PCMHI is needed. The current study was not powered to examine potentially important demographic (e.g., race, gender), contextual (e.g., levels of social support), and experiential (e.g., childhood or prior trauma vs. not; multiple combat traumas vs. single; trauma in the context of traumatic grief) moderation/mediation factors. Another limitation is the use of the WHODAS 2.0 during PTSD treatment. While this measure was intentionally chosen as the study primary outcome was function, it is novel within the PTSD population and as a result, it is unclear what is clinically meaningful change. Exclusion of those with significant comorbid substance use, over 70, and speakers of other languages are also limitations. Finally, examination of long-term follow-up is warranted to determine maintenance of change beyond six months.

In conclusion, the IMPACT study supports that both PE-PC and PCMHI-TAU for PTSD improve function and reduce PTSD, thereby providing multiple options for brief effective interventions in PC. Veterans can obtain PTSD treatment quickly in VA PCMHI at the time of screening positive for PTSD.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement.

Veterans with PTSD can be effectively treated in the primary care setting. Specifically, Veterans who received either Prolonged Exposure for Primary Care or usual VA integrated primary care showed reductions in PTSD and improvement in PTSD function.

Disclosures & Acknowledgements:

This work received support from VA Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development grant titled “Improving Function Through Primary Care Treatment of PTSD” (Award # I01RX002625; PI: Rauch). This material results from work supported by resources and the use of facilities at the Atlanta VA Healthcare System and Ralph H. Johnson VA Health Care System. The VA had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Rauch receives support from Wounded Warrior Project (WWP), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), National Institute of Health (NIH), McCormick Foundation, Tonix Pharmaceuticals, Woodruff Foundation, and Department of Defense (DOD). Dr. Rauch receives royalties from Oxford University Press and American Psychological Association Press. Dr. Zivin receives support from VA HSRD Research Career Scientist (VA RCS 21-138 & VA HSRD Merit IIR 17-262). Drs Kim, Acierno, & Wangelin have nothing to disclose. Ms. Muzzy receives support from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DOD). HM Kim takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Jeffrey Cigrang as a training consultant and collaborator on treatment development. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect an endorsement by or the official policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03581981

References

- Axelsson E, Lindsäter E, Ljótsson B, Andersson E, & Hedman-Lagerlöf E (2017). The 12-item Self-Report World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0 Administered Via the Internet to Individuals With Anxiety and Stress Disorders: A Psychometric Investigation Based on Data From Two Clinical Trials. JMIR Ment Health, 4(4), e58. 10.2196/mental.7497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess, 28(11), 1379–1391. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigrang JA, Rauch SA, Mintz J, Brundige AR, Mitchell JA, Najera E, Litz BT, Young-McCaughan S, Roache JD, & Hembree EA (2017). Moving effective treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder to primary care: A randomized controlled trial with active duty military. Families, Systems, & Health, 35(4), 450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GM, Smith N, Holliday R, Rozek DC, Hoff R, & Harpaz-Rotem I (2021). Racial Disparities in Clinical Outcomes of Veterans Affairs Residential PTSD Treatment Between Black and White Veterans. Psychiatric Services, 73(2), 126–132. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs KM, Fortney JC, Kimbrell T, Pyne JM, Hudson T, Robinson D, Moore WM, Custer P, Schneider R, & Schnurr PP (2017). Usual Care for Rural Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The Journal of Rural Health, 33(3), 290–296. 10.1111/jrh.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton M, O’Donnell M, Cowlishaw S, Kartal D, Metcalf O, Varker T, McFarlane AC, Hopwood M, Bryant RA, Forbes D, Howard A, Lau W, Cooper J, & Phelps AJ (2021). Defining post-traumatic stress disorder recovery in veterans: Benchmarking symptom change against functioning indicators. Stress and Health, 37(3), 547–556. 10.1002/smi.3019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane T, Fairbank J, Caddell J, Zimering R, Taylor K, & Mora C (1989). Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychological Assessments, 1, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Holder N, Madden E, Li Y, Seal KH, Neylan TC, Lujan C, Patterson OV, DuVall SL, & Shiner B (2020). Evidence-based psychotherapy trends among posttraumatic stress disorder patients in a national healthcare system, 2001–2014. Depress Anxiety, 37(4), 356–364. 10.1002/da.22983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Lee DJ, Norman SB, Bovin MJ, Sloan DM, Weathers FW, Keane TM, & Schnurr PP (2022). Reliable and clinically significant change in the clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 among male veterans. Psychological assessment, 34(2), 197–203. 10.1037/pas0001098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Foa EB, Dondanville KA, Haddock CK, Miller ML, Rauch SAM, Yarvis JS, Wright EC, Hall-Clark BN, Fina BA, Litz BT, Mintz J, Young-McCaughan S, & Peterson AL (2021). The effects of web-prolonged exposure among military personnel and veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Trauma, 13(6), 621–631. 10.1037/tra0000978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller L, Wolfe WR, Neylan TC, McCaslin SE, Yehuda R, Flory JD, Kyriakides TC, Toscano R, & Davis LL (2019). Positive impact of IPS supported employment on PTSD-related occupational-psychosocial functional outcomes: Results from a VA randomized-controlled trial. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal, 42(3), 246–256. 10.1037/prj0000345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Ouimette P, Lantinga LJ, Wade M, Coolhart D, Schohn M, Labbe A, & Strutynski K (2011). Treatment of Department of Veterans Affairs primary care patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services, 8(2), 82–93. 10.1037/a0022704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Wray LO, Johnson E, Webster B, & Beehler GP (2018). Facilitators and Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Care Among Primary Care Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(5), 742–752. 10.1002/jts.22327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SAM, Kim HM, Acierno R, Ragin C, Wangelin B, Blitch K, Muzzy W, Hart S, Zivin K, & Cigrang J (2022). Improving function through primary care treatment of PTSD: The IMPACT study protocol. Contemporary clinical trials, 120, 106881. 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SAM, Wilson CK, Jungerman J, Bollini A, & Eilender P (2020). Implementation of Prolonged Exposure for PTSD: Pilot Program of PE for Primary Care in VA. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Gore WL, Chard KM, & Meyer EC (2017). Examination of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment System as a measure of disability severity among veterans receiving cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(6), 704–709. 10.1002/jts.22243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, & Resick PA (2018). A Brief Exposure-Based Treatment vs Cognitive Processing Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Noninferiority Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(3), 233–239. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Smith B, Paddock SM, Mannle TE Jr., Woodroffe A, Solomon J, Sorbero ME, Farmer CM, Hepner KA, Adamson DM, Forrest L, & Call C (2011). The Cost and Quality of VA Mental Health Services. RAND Corporation. 10.7249/RB9594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, Sloan DM, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM, & Marx BP (2018). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. 10.1037/pas0000486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.