Abstract

Western blot analysis of proteins from a cell culture isolate (USG3) of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) agent has identified a number of immunoreactive proteins, including major antigenic proteins of 43 and 45 kDa. Peptides derived from the 43- and 45-kDa proteins were sequenced, and degenerate PCR primers based on these sequences were used to amplify DNA from USG3. Sequencing of a 550-bp PCR product revealed that it encodes a protein homologous to the MSP-2 proteins of Anaplasma marginale. Concurrently, an expression library made from USG3 genomic DNA was screened with granulocytic Ehrlichia (GE)-positive immune sera. Analysis of two clones showed that they contain one partial and three full-length highly related genes, suggesting that they are part of a multigene family. Amino acid alignment showed conserved amino- and carboxy-terminal regions which flank a variable region. The conserved regions of these proteins are also homologous to the MSP-2 proteins of A. marginale; thus, they were designated GE MSP-2A (45 kDa), MSP-2B (34 kDa), and MSP-2C (38 kDa). The PCR fragment obtained as a result of peptide sequencing was completely contained within the msp-2A clone, and all of the sequenced peptides were found in the GE MSP-2 proteins. Recombinant MSP-2B protein and an MSP-2A fusion protein were expressed in Escherichia coli and reacted with human sera positive for the HGE agent by immunofluorescence assay. These data suggest that the 43- and 45-kDa proteins of the HGE agent are encoded by members of the GE MSP-2 multigene family.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE), a disease characterized by fever, lethargy, thrombocytopenia, and occasionally death (5, 6), is caused by a tick-borne agent that is similar or identical to the veterinary pathogens Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila (4–6, 12, 16, 17, 23). Sequencing of the 16S rRNA genes (2, 6, 24) and, more recently, the groESL operons (15, 25) of these organisms shows that their DNA is 98.9 to 99% identical in these conserved regions. Convalescent-phase sera from either HGE patients or animals infected or immunized with E. equi or E. phagocytophila all react with E. equi antigen in an indirect fluorescent-antibody assay (IFA) (9, 18, 20, 26). Western blot analysis shows that the three organisms probably share related immunoreactive antigens, especially in the 42- to 49-kDa range (3, 9, 26, 28).

In an effort to characterize the immunoreactive antigens of the HGE agent and to further analyze the genetic relatedness of the members of this granulocytic Ehrlichia (GE) genogroup, we have sequenced peptides derived from two GE proteins, of 43 and 45 kDa, and constructed and screened a genomic expression library made from the DNA of strain USG3 of the HGE agent (20, 27). Previously, we reported the sequencing and immunoreactivity of three high-molecular-mass proteins encoded by this agent (24). Here, we report the isolation of additional genes which appear to comprise a multigene family with homology to the msp-2 genes of Anaplasma marginale (22). DNA sequencing, peptide sequencing, and Western blot analysis with GE-positive human and animal sera all indicate that the MSP-2 antigens of the HGE agent are highly immunoreactive and may be important diagnostic reagents for the detection of HGE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and purification of GE.

GE strain USG3 was isolated and purified as described previously (20, 24, 27).

Human sera.

Serum samples were obtained from 11 Wisconsin and 8 Minnesota residents with PCR- and/or IFA-confirmed HGE during various stages of illness or convalescence. Three additional serum samples were obtained from Wisconsin residents who participated in an HGE seroprevalence study. All sera contained E. equi-reactive antibodies by polyclonal (immunoglobulin G [IgG], IgA, and IgM) IFA (see Table 2). Two serum samples from patients diagnosed with Ehrlichia chaffeensis were also tested.

TABLE 2.

HGE patient profiles and diagnostic laboratory test resultsa

| Patient | Sex | Age (yr) | Location (state) | Convalescence stage (mo) | Morulae | PCRb | IFAc | Western blotd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 57 | MN | 0.5 | + | ND | 320 | + |

| 2 | M | 56 | WI | 12 | + | + | 160 | + |

| 3 | M | 59 | MN | 6 | + | ND | 320 | − |

| 4 | M | 74 | WI | 12 | + | + | 160 | + |

| 5 | M | 40 | WI | 12 | + | + | 320 | − |

| 6 | M | 71 | WI | 24 | + | + | 320 | − |

| 7 | M | 80 | WI | 36 | + | − | >2,560 | + |

| 8 | M | 60 | MN | 6 | − | ND | 320 | + |

| 9 | F | 44 | MN | 42 | − | − | >2,560 | + |

| 10 | M | 50 | WI | Random | ND | ND | >2,560 | + |

| 11 | F | 50 | WI | Random | ND | ND | >2,560 | + |

| 12 | M | 64 | WI | Random | ND | ND | 160 | − |

| 13e | F | 65 | RI | 1 | − | + | 512 | + |

| 14 | F | 29 | MA | NA | ND | ND | <32 | − |

| 15 | M | 56 | MN | 1 | + | ND | >2,560 | + |

| 16 | M | 41 | WI | 1 | + | + | >2,560 | + |

| 17 | M | 62 | WI | 6 | + | ND | >2,560 | + |

| 18 | M | 79 | MN | 1 | + | + | 2,560 | + |

| 19 | M | 59 | WI | 1 | + | ND | >2,560 | + |

| 20 | F | 83 | MN | 6 | ND | ND | >2,560 | +(GE)/−(MSP) |

| 21 | F | 76 | WI | 1 | + | + | >2,560 | + |

| 22 | M | 84 | WI | 6 | ND | ND | >2,560 | − |

| 23 | M | 34 | MN | 1 | + | ND | >2,560 | + |

| 24 | M | 76 | WI | 1 | + | + | 1,280 | + |

Abbreviations and symbols: F, female; M, male; NA, not applicable; +, positive; −, negative; ND, not done. States are given as U.S. Postal Service abbreviations.

With primers GE9F and GE10R (6).

With E. equi antigen.

Western blot results with GE antigen, MSP-2A, and MSP-2B.

Data from reference 27.

Peptide sequencing of immunoreactive proteins.

Fifty microliters of a cocktail consisting of RNase (33 μg/ml) and aprotinin (0.2 mg/ml) and 9 μl of DNase (0.17 mg/ml) was added per 5 mg of USG3 pellet in buffer containing 2 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Twenty microliters of 25× Boehringer Mannheim protease inhibitor cocktail was added per 0.5 ml of cell suspension, and 2 μl of a phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride solution (1 M in dimethyl sulfoxide) was added just prior to USG3 disruption. Cells were disrupted at 30-s intervals for a total of 3 min in a Mini-Beadbeater cell disrupter, type BX-4 (BioSpec), agitated at room temperature for 30 min, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was suspended in Laemmli sample buffer, adjusted to 1.4 mg of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) per mg of protein, and heated at 90 to 100°C for 5 min. The protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.). Electrophoresis was performed on an SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel, and proteins were transferred to a 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Half of the blot was probed with anti-GE dog serum (6), and the other half was stained with Ponceau S. Two protein bands which matched the molecular masses of the two most immunoreactive bands on the Western blot (43 and 45 kDa) were excised.

A portion of each band was used for direct N-terminal sequencing. The remaining material was digested with trypsin in situ, and individual peptides were separated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a ZORBAX C18 (1- by 150-mm) column. The peptides were analyzed and screened by MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight) mass spectrometry. Sequencing of peptides was performed by Edman degradation (Harvard Microchemistry, Cambridge, Mass.).

Degenerate-primer PCR.

Pools of degenerate oligonucleotides corresponding to the reverse translation of each sequenced peptide were synthesized. The reverse complement of each oligonucleotide was also synthesized, with the exception of the one corresponding to the N-terminal peptide. PCR amplifications were performed with one forward and one reverse primer set using USG3 genomic DNA as a template and an annealing temperature of 55°C. Primer pairs gave either no PCR product or a single band. The primer pair that resulted in the longest product, 550 bp, consisted of the forward primer 5′ ACNGGNGGNGCWGGNTAYTTY 3′ (N-terminal peptide HDDVSALETGGAGYF) and the reverse primer 5′ CCNCCRTCNGTRTARTCNGC 3′ (peptide SGDNGSLADYTDGGASQTNK). Sequencing of the PCR product was performed as described below.

Construction of a GE genomic library.

Genomic DNA was isolated from purified USG3, mechanically sheared, and ligated to EcoRI linkers for expression library preparation. The library was prepared with the Lambda ZAP II vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), as described previously (24).

Preparation of screening sera.

Mixtures of 100 μg of purified heat-inactivated USG3 antigen were used to immunize goats. Goats received three subcutaneous doses of antigen at biweekly intervals. Serum was collected 2 weeks after the third immunization.

Expression screening of the genomic library.

Bacteriophage were plated with XL1-Blue MRF′ and induced to express protein with 10 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and the filters were washed with TBS (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5 M NaCl). Washed filters were blocked in TBS containing 0.1% polyoxyethylene-20-cetyl ether (Brij 58) and incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of goat serum depleted of anti-E. coli antibodies. The filters were washed and incubated with rabbit anti-goat Ig horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:2,000 dilution), rewashed, and developed with 4-chloronaphthol. Positive plaques were isolated, replated, and screened again. Plasmid DNA containing the putative recombinant clones was obtained by plasmid rescue (Stratagene).

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

DNA sequencing of recombinant clones was performed by the primer walking method and with an ABI 373A DNA sequencer (ACGT, Northbrook, Ill.). Sequences were analyzed by using the MacVector (Oxford Molecular Group) sequence analysis program, version 6.0. The BLAST algorithm, D version 1.4 (13, 14), was used to search for homologous nucleic acid and protein sequences available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information server.

PCR analysis of USG3 and HL60 DNA.

PCR primer sets were designed based on the sequences of each GE clone and are as follows: E8 (forward, 5′ GCGTCACAGACGAATAAGACGG 3′; reverse, 5′ AGCGGAGATTACAGGAGAGAGCTG 3′), E46.1 (forward, 5′ TGTTGAATACGGGGAAAGGGAC 3′; reverse, 5′ AGCGGAGATTTCAGGAGAGAGCTG 3′), and E46.2 (forward, 5′ TGGTTTGGATTACAGTCCAGCG 3′; reverse, 5′ ACCTGCCCAGTTTCACTTACATTC 3′). Each 50-μl reaction mix contained a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer, 1× PCR Supermix (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.), and either 100 ng of USG3 DNA, 100 ng of HL60 DNA, or 250 ng of plasmid DNA. PCR amplification was performed under the following conditions: 94°C for 30 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. After 30 cycles, a single 10-min extension at 72°C was done. PCR products were analyzed on 4% Nusieve 3:1 agarose gels (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine).

Western blot analysis.

Individual recombinant plasmid-containing cultures were induced to express protein with 5 mM IPTG. Bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 5× Laemmli buffer (12% glycerol, 0.2 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 5% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol) at 200 μl per 1 optical density unit of culture. Samples were boiled and 10 μl of each sample was analyzed on NuPage or Tris glycine gels (Novex, San Diego, Calif.). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose filters, the filters were blocked in TBS-Brij 58, and the blots were probed with either a 1:500 dilution of pooled sera from dogs that had been infected with GE by tick exposure (7), a 1:500 dilution of the goat serum described above, or a 1:1,000 to 1:5,000 dilution of human serum. Blots were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). After several additional washes, the blots were developed with the Pierce Super Signal chemiluminescence kit and viewed by autoradiography.

Southern blot analysis.

Digoxigenin-labeled probes were prepared by PCR with the PCR Dig Probe Synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Two sets of primers were used to generate a 240-bp product (probe A) from the 5′ end of the E8 gene (forward primer, 5′ CATGCTTGTAGCTATG 3′; reverse primer, 5′ GCAAACTGAACAATATC 3′) and a 238-bp product (probe B) from the 3′ end of the E8 gene (forward primer, 5′ GACCTAGTACAGGAGC 3′; reverse primer, 5′ CTATAAGCAAGCTTAG 3′). Genomic DNA was prepared from USG3 or HL60 cells as described above, and aliquots of 0.6 μg of DNA were digested with SphI, NdeI, SacI, or SspI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). These restriction endonucleases do not cut within the sequence of E8 msp-2A. Calf thymus DNA was digested identically, as a control. Recombinant pBluescript E8 plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI and used as a positive control for probe hybridization. Digested fragments were separated by gel electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel. Southern blotting was performed under prehybridization and hybridization conditions of 65°C in Dig Easy Hyb (Boehringer Mannheim), and hybridization was performed overnight. Two membrane washes in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS were performed at room temperature for 5 min each, followed by two washes in 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min each. Bound probe was detected by chemiluminescence with anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphate-conjugated antibody (Boehringer Mannheim).

Cloning and expression of recombinant GE MSP-2B.

PCR amplification of the first gene in pBluescript clone E46 was performed to generate an insert for subcloning in E. coli. Primer sets were designed to contain restriction sites for cloning, a translation termination codon, and a six-residue histidine sequence for expressed protein purification (forward, 5′ CCGGCATATGCTTGTAGCTATGGAAGGC; reverse, 5′ CCGGCTCGAGCTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGAAAAGCAAACCTAACACCAAATTCCCC). The 100-μl reaction mix contained 500 ng of each primer, 500 ng of E46 template, and 1× PCR Supermix (Life Technologies). Amplification was performed under the following conditions: 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. After 37 cycles, a single 10-min extension at 72°C was performed. Following analysis on a 1% Tris-borate-EDTA agarose gel, amplified product was purified by using a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) and digested with restriction enzymes NdeI and XhoI (New England Biolabs) under the manufacturer’s recommended conditions. The 1,004-bp fragment was ligated into NdeI- and XhoI-digested pXA and transformed into E. coli MZ-1 (19). Expression vector pXA is a pBR322-based vector containing the bacteriophage lambda pL promoter, a ribosome binding site, an ATG initiation codon, and transcription and translation termination signals. Recombinant MSP-2B was induced by growing the MZ-1-transformed clone to an A550 of 1.0 at 30°C and then shifting the temperature to 38°C for an additional 2 h. Aliquots (1.5 ml) of preinduced and induced cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 5× Laemmli buffer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the genes described here have been assigned the following GenBank accession numbers: GE msp-2A, AF029322; GE msp-2B and GE msp-2C, AF029323.

RESULTS

Protein analysis and peptide sequencing of immunoreactive USG3 antigens.

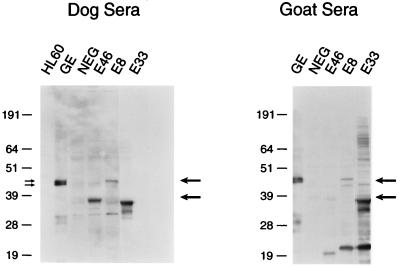

Immune sera from either animals or humans exposed to the HGE agent recognize several immunoreactive antigens by Western blotting (24) (see Fig. 1 and 7, lanes GE). To determine the identity of the immunoreactive GE proteins in the 42- to 45-kDa range, samples of purified USG3 were prepared and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The proteins which comigrated with two immunoreactive proteins of approximately 43 and 45 kDa (indicated in Fig. 1 by double arrows on the left) were excised. A portion of each protein sample was used for N-terminal sequencing, and the remaining protein was used for internal peptide sequencing. An N-terminal peptide and two internal peptides were obtained for each protein (Table 1). The results showed that the N-terminal peptides from the two proteins are identical. A BLAST homology search showed that two of the internal peptides from the 43-kDa protein are homologous to the MSP-2 proteins of A. marginale, a rickettsial hemoparasite of livestock (22) which is phylogenetically closely related to GE (9). To obtain additional sequence information for these proteins, degenerate pools of oligonucleotides were synthesized based on the reverse translation of the peptide sequences and were used to amplify DNA from USG3. The combination of the forward primer based on the N-terminal peptide and the reverse primer based on the 45-kDa peptide SGDNGSL… (Table 1) produced a PCR product of 550 bp. This DNA was sequenced and found to contain an open reading frame encoding a product with homology to the MSP-2 proteins of A. marginale (Fig. 2). Two other peptides, one from the 45-kDa protein and one from the 43-kDa protein, were also contained within this sequence. PCR of USG3 genomic DNA with degenerate primers reverse translated from these peptide sequences produced DNA products of the sizes expected based on the locations of the peptide-coding regions within the gene (data not shown). The similarity in protein sequence between the two immunoreactive 43- and 45-kDa proteins may indicate that they are differentially modified or processed versions of the same protein or that they represent proteins expressed from two different members of a gene family.

FIG. 1.

Expression of GE proteins by Western blotting. Samples containing purified USG3 antigen (GE), uninfected HL60 cell proteins, a pBluescript library clone with no insert (NEG), E46, E8, or E33 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose blots. Blots were probed with either dog or goat sera. Molecular size markers are given on the left of each blot (in kilodaltons). Positions of expressed proteins are indicated by arrows on the right side of each blot. The double arrows on the left indicate the proteins that were excised for peptide sequencing.

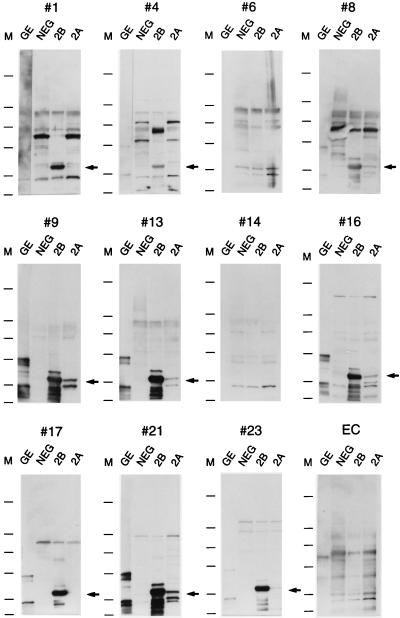

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis of purified GE, MSP-2B, and MSP-2A with HGE patient sera. Bacterial cultures of E4 (no plasmid insert [NEG]), E33 MSP-2A and MSP-2B, and a sample of purified GE were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose blots. The blots were probed with the patient sera described in Table 2. The number above each blot corresponds to the patient number given in Table 2. The last blot was probed with an E. chaffeensis-positive serum sample (EC). Molecular size markers are given on the left side of each blot and correspond to molecular masses of 250, 98, 64, 50, 36, and 30 kDa (from top to bottom). The arrows show the positions of the MSP-2 proteins.

TABLE 1.

Peptide sequences from transblotted GE proteins

| Protein and amino acid sequencea | Frag- mentb | Homology to A. marginale MSP-2 | Locationc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 kDa | |||

| HDDVSALETGGAGYF | N | No | MSP-2A, MSP-2C (1) |

| SGDNGSLADYTDGGASQTNK | I | No | MSP-2A |

| AVGVSHPGIDK | I | No | MSP-2A, MSP-2C (2) |

| 43 kDa | |||

| HDDVSALETGGAGYF | N | No | MSP-2A, MSP-2C (1) |

| FDWNTPDPR | I | Yes | MSP-2A, MSP-2C |

| LSYQLSPVISAFAGGFYH | I | Yes | MSP-2A, MSP-2B (1) |

Amino acids are given in single-letter code.

N, N-terminal; I, internal.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of amino acid changes from the sequence shown.

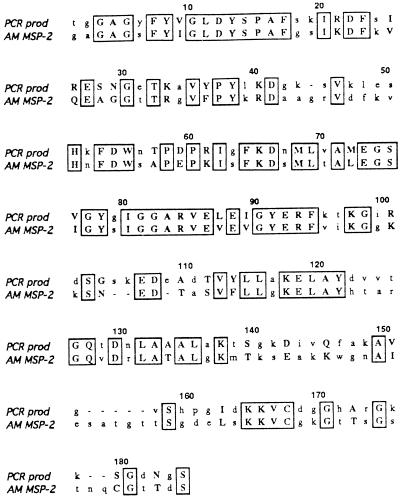

FIG. 2.

ClustalW alignment of amino acids encoded by the 550-bp PCR product and the MSP-2 protein of A. marginale (GenBank accession no. U07862). Identical amino acids are enclosed by boxes. Amino acids which represent conservative codon changes are shown in uppercase letters.

Isolation of recombinant clones identified with serum from USG3-immunized goats.

A goat serum reactive against proteins of the HGE agent was obtained by immunizing animals three times with purified USG3 antigen. Western blot analysis showed that many proteins of various molecular mass were recognized by this serum, including the 43- and 45-kDa proteins (Fig. 1, lane GE). The USG3 genomic expression library was screened with immune goat serum, and several immunoreactive plaques were identified for further analysis. To eliminate clones previously isolated with immune dog sera, phage supernatants from the plaques were screened by PCR with primers based on the sequences of those previously identified clones (GE ank, GE rea, and GE gra [24]). pBluescript plasmids were rescued from the remaining clones, and they were assessed for relatedness by restriction enzyme analysis. Two clones, E8 and E33, appeared to contain similar inserts in opposite orientation from the lacZ promoter. Two other clones, E46 and E80, had restriction enzyme fragments in common, but E46 contained a larger insert than E80.

DNA sequencing and database analysis of recombinant clones.

Three clones, E8, E33, and E46, were sequenced by the primer walking method. Both strands of each insert were sequenced. The sequences of the three clones had considerable homology. The E8 clone contained a larger version of the E33 insert but in opposite orientation with respect to the lacZ promoter (Fig. 3). Both clones contained the same open reading frame, but E33 was missing 420 nucleotides from the 5′ end of the gene. The deduced amino acid sequence of the E33 open reading frame was in frame with the partial β-galactosidase amino acid sequence encoded by the vector (data not shown). The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the pBluescript E8 insert (which did contain the entire gene) are shown in Fig. 4. The predicted molecular mass of the protein encoded by this gene is 45.9 kDa.

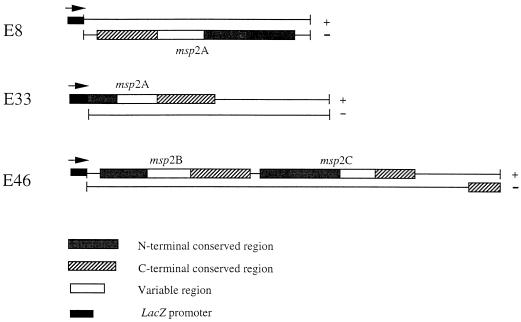

FIG. 3.

Schematic diagram of E8, E33, and E46 pBluescript inserts. Each strand of the DNA insert is shown as a line. +, plus-strand DNA; −, minus-strand DNA. Boxed regions indicate related open reading frames. The positions and orientations (arrows) of the lacZ promoter are indicated.

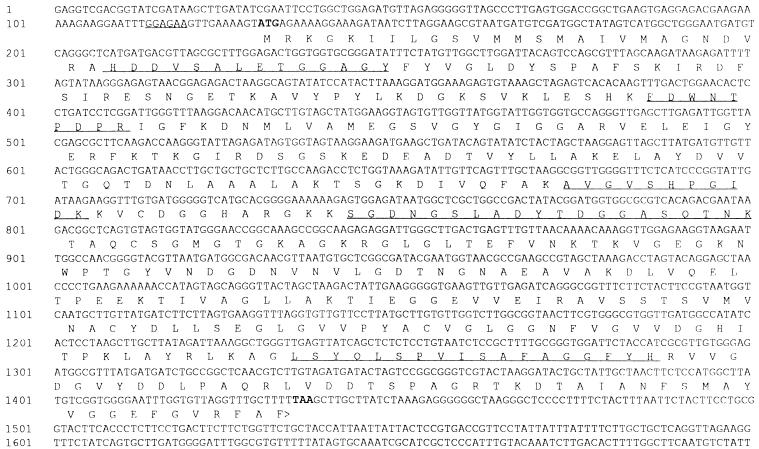

FIG. 4.

Sequence of the GE E8 msp-2 gene. Nucleotide numbers are given on the left. The ATG start codon and TAA stop codon are shown in boldface type. The translated amino acid sequence for the open reading frame is displayed underneath the DNA sequence in single-letter code. Peptide sequences shown in Table 1 are underlined. A possible ribosome binding site upstream of the ATG codon is also underlined.

The E46 insert contained one partial and two complete open reading frames which all had considerable homology with the protein encoded by the E8 gene. Figure 3 shows how the DNA sequences (plus and minus strands) and deduced amino acid sequences from E46 compare with those from E8 and E33. The boxed regions represent the open reading frames, and shaded areas indicate homologous sequences. All three of the complete genes showed similar patterns for the encoded proteins: a variable domain flanked by conserved amino- and carboxy-terminal regions. The lengths of the conserved regions varied among the encoded proteins, with the longest amino- and carboxy-terminal conserved regions present in the E8 protein.

The sequences present in the E8, E33, and E46 pBluescript plasmids were confirmed to be derived from USG3 genomic DNA and not HL60 DNA by PCR analysis with the primers described in Materials and Methods (data not shown).

When the sequences of the three full-length genes isolated by expression library cloning were compared with the sequence of the PCR product derived from the peptide analysis, it was found that the PCR fragment was contained within the E8 sequence, bp 232 to 760 (Fig. 4). In fact, the N-terminal peptide and all four internal peptides sequenced from the 43- and 45-kDa proteins were found within the amino acid sequence of the E8 protein. The sequenced peptides are underlined in Fig. 4. The N-terminal peptide (HDDVSALE…) was found beginning at amino acid 27; this may indicate that the first 26 amino acids are part of a signal peptide which is cleaved to produce the mature protein.

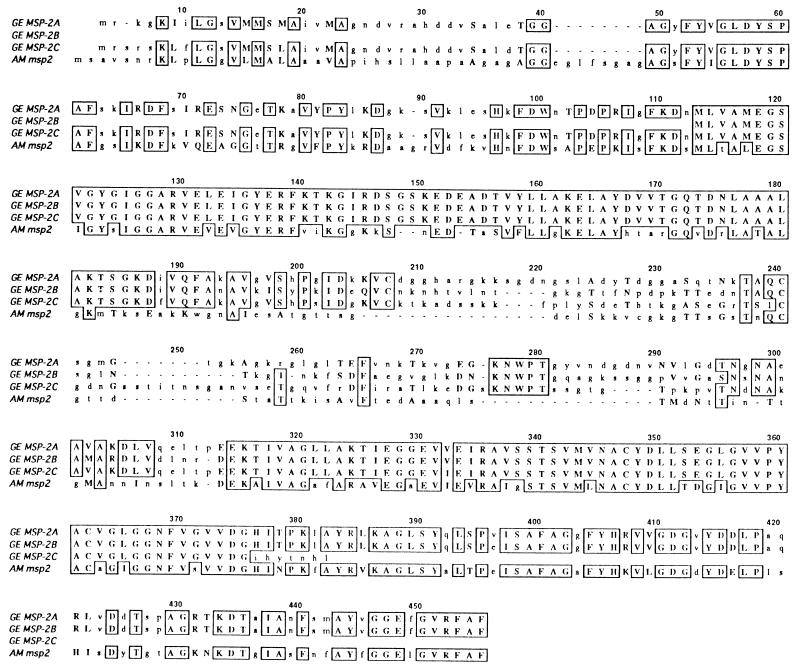

Since the PCR product had both nucleotide and amino acid homology to the A. marginale msp-2 gene family, a BLAST homology search was performed to assess the relatedness of the E8 and E46 gene products to this family as well. Strong matches for all of the GE proteins described here to the A. marginale MSP-2 proteins were observed. A ClustalW amino acid alignment of the GE proteins (designated GE MSP-2A [E8], MSP-2B [E46.1], and MSP-2C [E46.2]) with one of the A. marginale MSP-2 proteins (GenBank accession no. U07862) is shown in Fig. 5. The homology of the GE MSP-2 proteins with A. marginale MSP-2 occurred primarily in the conserved regions shown in Fig. 3. Amino acid identity ranged from 40 to 50% between the proteins of the two species, and amino acid similarity was close to 60%. The A. marginale MSP-2 proteins contain signal peptides (22), and the data indicating that GE MSP-2A has a signal peptide is consistent with the homology observed between the MSP-2 proteins of the two species.

FIG. 5.

ClustalW alignment of the GE MSP-2 and A. marginale MSP-2 (U07862) protein sequences. Identical amino acids are enclosed by boxes. Amino acids which represent conservative codon changes are indicated by uppercase letters. Dashes denote gaps used to achieve optimal alignment between the sequences.

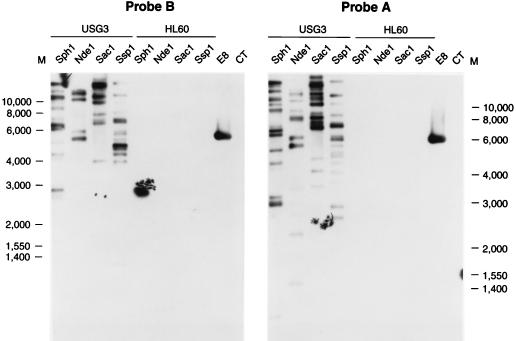

Southern blot analysis of GE msp-2 sequences.

To determine whether additional copies of msp-2 were present in the genome, genomic DNA was isolated from USG3 and digested with restriction enzymes. Digested DNA was Southern blotted to nylon membranes and probed with either probe A (derived from the 5′-terminal conserved region of E8 msp-2A) or probe B (from the 3′-terminal conserved region of E8 msp-2A). HL60 DNA was digested in the same way and used as a negative control. The restriction enzymes SphI, NdeI, SacI, and SspI were chosen because they do not cut within the msp-2A, msp-2B, or msp-2C sequences. Figure 6 shows that multiple bands were present on Southern blots with both probes, indicating the presence of multiple msp-2 copies. The exact number of genes cannot be determined since sequence differences may generate additional restriction enzyme sites in some of the msp-2 copies, resulting in more than one band from a single copy. Also, more than one msp-2 gene might be present on a single restriction fragment, an event which does occur with the msp-2B and msp-2C genes.

FIG. 6.

Southern blot analysis of msp-2 in USG3 genomic DNA. Genomic DNA from USG3 or HL60 cells was digested with the restriction enzymes indicated above the lanes and Southern blotted. EcoRI-digested E8 plasmid DNA was used as a positive control for probe hybridization, and calf thymus DNA (CT) was used as a negative control. The blots were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled probe A (5′ end of E8 msp-2A) or probe B (3′ end of E8 msp-2A).

Western blot analysis of proteins encoded by GE clones.

Bacterial lysates from the genomic library clones E8, E33, and E46 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The blots were probed with either pooled sera from dogs that were infected with GE by tick exposure (7) or with the goat serum used to screen the library. Figure 1 shows that a protein of approximately 37 kDa from the E46 clone, a 45-kDa protein from the E8 clone, and a 34- to 36-kDa protein doublet from the E33 clone were specifically detected by dog and goat sera (indicated by arrows on the right side of each blot). The reactivity of the sera differed somewhat in that the dog sera reacted much better than the goat sera with the E46 protein and the goat sera had better reactivity to the E8 and E33 proteins. Whether the 37-kDa E46 protein is encoded by the first or second E46 gene is unknown, and the reason for the expression of two closely sized immunoreactive E33 proteins is also unclear. Preimmune sera did not detect these proteins (data not shown), and expression was observed in the absence of IPTG induction. The molecular mass of the proteins is consistent with the coding capacity of the msp-2 genes found in the library clones. The negative control (Fig. 1, lane NEG) was a pBluescript library clone without an insert. Figure 1 also shows a couple of proteins of smaller molecular masses from E46, E33, and E8 that react specifically with the goat serum. It is not known whether they are breakdown products of the full-length MSP-2 proteins or whether they are produced by internal initiation within the msp-2 genes.

Recognition of MSP-2A and MSP-2B by GE-positive human sera.

Since expression levels of the GE MSP-2A and MSP-2BC proteins from the library clones E8 and E46 were quite poor (Fig. 1; also data not shown), the coding regions for MSP-2A and MSP-2B were recloned with a heat-inducible E. coli expression system. Expression of the MSP-2A protein with this system remained low and appeared to be toxic to the cells. However, the recombinant MSP-2B protein was expressed and detected with both dog and goat GE-positive sera and visualized by Coomassie blue staining (data not shown).

The recombinant MSP-2B protein and the E33 MSP-2A protein (which was expressed in E. coli at a higher level than E8 MSP-2A [Fig. 1] but was not detectable by Coomassie blue staining [data not shown]) were then tested for reactivity with human serum samples which had previously been shown to be positive for GE by IFA. Table 2 shows the patient profiles and diagnostic laboratory results from 24 individuals. Twenty of these individuals were clinically diagnosed with HGE (patients 1 to 9, 13, and 15 to 24), three of them participated in a seroprevalence study (patients 10 to 12), and one was a negative control (patient 14). Three additional serum samples not shown in the table, two E. chaffeensis-positive sera and one negative serum sample, were also tested.

Figure 7 shows the reactivity of 12 of these human serum samples with purified USG3 (lanes GE) and lysates from a pBluescript clone with no insert (lanes NEG), MSP-2B (lanes 2B), and MSP-2A (lanes 2A). Western blot results for all human sera listed in Table 2 are indicated in the last column of the table. Of the 23 E. equi IFA-positive sera, 17 reacted with purified GE (predominantly 34-, 43-, and 45-kDa proteins) and MSP-2B (Fig. 7; Table 2). Most of these also recognized MSP-2A, although the reactivity was much less than for MSP-2B, probably due in part to its lower expression level. Some of the sera had high E. coli reactivity (Fig. 7, panels 1 and 8), which may have obscured reactivity to MSP-2A. One additional serum sample (from patient 20) reacted weakly with purified GE but did not detect MSP-2B or MSP-2A (data not shown). All of the negative control samples, including the E. chaffeensis sera, were negative in the Western blot assay (Fig. 7, panels 14 and EC). From these data, it appears that IFA may be more sensitive than Western blotting for diagnosis of HGE. However, the use of purified recombinant proteins would allow longer exposure times and increased sensitivity.

DISCUSSION

The ability to grow the agent of HGE in cell culture (11, 20, 27) has made it possible to characterize the organism for its important antigens and for its phylogenetic relationships to other obligate intracellular rickettsiae. Phylogenetic analyses have historically been based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and show that the HGE agent, E. equi, and E. phagocytophila form a distinct genogroup (2, 6). The same analysis indicates that A. marginale, currently classified in another genus (8), also groups with GE. A recent study comparing the sequences of the groESL heat shock operons in the GE genogroup (25) showed that they were very similar (99.9 to 99.0% identity). However, variations in less conserved genes, such as those encoding surface proteins, may be more important in elucidating subtle differences between the organisms which impact host range and disease patterns.

In a previous study we reported the sequences and immunoreactivity profiles of three potential surface proteins from the HGE agent found by screening a genomic expression library with convalescent dog sera (24). In this study we describe three other genes which appear to be part of a multigene family. These genes were identified both by expression library screening and by peptide sequencing of immunoreactive proteins in the 43- to 45-kDa range. Sequence analysis of the three full-length genes revealed that the encoded proteins contain highly homologous amino- and carboxy-terminal regions related to the MSP-2 proteins of A. marginale.

In addition to the three full-length and one truncated msp-2-like genes reported here, there are likely to be others present in the genome of the HGE agent. Hybridization studies using probes from either the 5′ or 3′ end of the E8 msp-2 gene identified multiple copies of homologous msp-2 genes in the genome of strain USG3 of the HGE agent. Sequencing of several other GE library clones has revealed short (100- to 300-nucleotide) stretches of DNA homologous to msp-2 (18a). Because of the possible polymorphism in restriction sites and the possibility that several msp-2 genes may be present on the same restriction fragment, it is difficult to determine the exact number of copies of this gene in the HGE agent genome. Several different MSP-2 proteins ranging in size from 33 to 41 kDa have been reported for A. marginale (22), and >1% of its genome may consist of msp-2 (22).

Analysis of human sera from patients recovering from HGE or sera from animals infected with GE shows that a 44-kDa protein and often a 42-kDa protein are detected on Western blots using E. equi antigen (3, 9, 26). Using six different cell culture isolates of the HGE agent, Zhi et al. (28) found that the molecular sizes and numbers of major antigens varied among the isolates but that most had one or two immunodominant antigens of 47 and 49 kDa. One isolate had a major antigen of 43 kDa. The USG3 isolate (provided by our laboratory) was also analyzed by Zhi et al. (28) and was found to have a 49-kDa immunodominant protein. This protein likely corresponds to the 45-kDa protein described in this study since the same cell line and dog antisera were used for analysis. Differences in apparent molecular mass are probably due to the different gel systems and SDS-PAGE standards used. We have found that there are at least two proteins from USG3 in this 43- to 45-kDa region which can be resolved under different SDS-PAGE conditions. Both the DNA and peptide sequencing results presented in this paper support the conclusion that these immunoreactive antigens of the HGE agent are likely to be the GE MSP-2 proteins. Recombinant versions of these proteins expressed in E. coli are recognized by a majority of HGE patient sera. This number could potentially be improved both by increasing the expression of recombinant protein (in particular, MSP-2A) and by purification of these proteins. The fact that the MSP-2 antigens are encoded by a multigene family would explain the molecular mass polymorphism observed for different isolates. Multigene families and polymorphism of surface antigens have also been described for A. marginale (1, 22) and E. chaffeensis (21), two related rickettsiae.

The function of the GE MSP-2 proteins is unknown. Zhi et al. demonstrated that the antigens are present in outer membrane fractions of purified ehrlichiae (28). Thus, they may play a role in the interaction between the pathogen and the host cell. In A. marginale, expression of antigenically unique MSP-2 variants by individual organisms during acute rickettsemia in cattle suggests that the multiple msp-2 gene copies may provide a mechanism for evasion of the protective immune response directed against these antigens (10). This may explain the observation that the GE MSP-2A protein is present in purified USG3 but MSP-2B and MSP-2C are not. These antigens may be expressed only after natural or experimental infection. Whether such a mechanism for immune evasion exists for the agent of HGE, and the impact this would have on vaccine development for this disease, awaits further study of the organism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Durland Fish (Yale University) and Thomas Mather (University of Rhode Island) for the experimental challenge work with dogs which led to the isolation of GE in cell culture. We also thank Thomas Mather for the kind gift of human serum and William Nicholson and James Olson (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for the E. chaffeensis sera.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alleman A R, Palmer G H, McGuire T C, McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Barbet A F. Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 3 is encoded by a polymorphic, multigene family. Infect Immun. 1997;65:156–163. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.156-163.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson B E, Dawson J E, Jones D C, Wilson K H. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2838–2842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2838-2842.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asanovich K M, Bakken J S, Madigan J E, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Wormser G P, Dumler J S. Antigenic diversity of granulocytic Ehrlichia isolates from humans in Wisconsin and New York and a horse in California. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1029–1034. doi: 10.1086/516529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakken J S, Dumler J S, Chen S-M, Eckman M R, Van Etta L L, Walker D H. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the upper Midwest. A new species emerging? JAMA. 1994;272:212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Wison-Nordskog C, Tilden R L, Asanovich K, Dumler J S. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 1996;275:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S-M, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Walker D H. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.589-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coughlin R T, Fish D, Mather T N, Ma J, Pavia C, Bulger P. Protection of dogs from Lyme disease with a vaccine containing outer surface protein (Osp) A, Osp B, and the saponin adjuvant QS-21. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1049–1052. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drancourt M, Raoult D. Taxonomic position of the Rickettsiae: current knowledge. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;13:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumler J S, Asanovich K M, Bakken J S, Richter P, Kimsey R, Madigan J E. Serologic cross-reactions among Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia phagocytophila, and human granulocytic ehrlichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1098–1103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1098-1103.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eid G, French D M, Lundgren A M, Barbet A F, McElwain T F, Palmer G H. Expression of major surface protein 2 antigenic varients during acute Anaplasma marginale rickettsemia. Infect Immun. 1996;64:836–841. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.836-841.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman J L, Nelson C, Vitale B, Madigan J E, Dumler J S, Kurtti T J, Munderloh U G. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardalo C J, Quagliarello V, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Connecticut: report of a fatal case. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:910–914. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlin S, Altschul S F. Methods for assessing the statistical significance of molecular sequence features by using general scoring schemes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2264–2268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlin S, Altschul S F. Applications and statistics for multiple high scoring segments in molecular sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5873–5877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolbert C P, Bruinsma E S, Abdulkarim A S, Hofmeister E K, Tompkins R B, Telford III S R, Mitchell P D, Adams-Stich J, Persing D H. Characterization of an immunoreactive protein from the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1172–1178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1172-1178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madigan J E, Richter P J, Kimsey R B, Barlough J E, Bakken J S, Dumler J S. Transmission and passage in horses of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1141–1144. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madigan J E, Barlough J E, Dumler J S, Schankman N S, DeRock E. Equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Connecticut caused by an agent resembling the human granulocytotropic ehrlichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:434–435. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.434-435.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnarelli L A, Dumler J S, Anderson J F, Johnson R C, Fikrig E. Coexistence of antibodies to tick-borne pathogens of babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme borreliosis in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3054–3057. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3054-3057.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Murphy, C. I., et al. Unpublished observations.

- 19.Nagai K, Thogerson H C. Generation of beta-globin by sequence-specific proteolysis of a hybrid protein produced in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1984;309:810–812. doi: 10.1038/309810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson W L, Comer J A, Sumner J W, Gingrich-Baker C, Coughlin R T, Magnarelli L A, Olson J G, Childs J E. An indirect immunofluorescence assay using a cell culture-derived antigen for detection of antibodies to the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1510–1516. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1510-1516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohashi N, Zhi N, Zhang Y, Rikihisa Y. Immunodominant major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:132–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.132-139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer G H, Eid G, Barbet A F, McGuire T C, McElwain T F. The immunoprotective Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 is encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3808–3816. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3808-3816.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikihisa Y. The tribe Ehrlichieae and ehrlichial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:286–308. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storey J R, Doros-Richert L A, Gingrich-Baker C, Munroe K, Mather T N, Coughlin R T, Beltz G A, Murphy C I. Molecular cloning and sequencing of three granulocytic Ehrlichia genes encoding high-molecular-weight immunoreactive proteins. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1356–1363. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1356-1363.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumner J W, Nicholson W L, Massung R F. PCR amplification and comparison of nucleotide sequences from the groESL heat shock operon of Ehrlichia species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2087–2092. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2087-2092.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong S J, Brady G S, Dumler J S. Serological responses to Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and Borrelia burgdorferi in patients from New York State. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2198–2205. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2198-2205.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh M-T, Mather T N, Coughlin R T, Gingrich-Baker C, Sumner J W, Massung R F. Serologic and molecular detection of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Rhode Island. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:944–947. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.944-947.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhi N, Rikihisa Y, Kim H Y, Wormser G P, Horowitz H W. Comparison of major antigenic proteins of six strains of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent by Western immunoblot analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2606–2611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2606-2611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]