Abstract

We report the isolation of 153 mouse genes whose expression is dramatically up-regulated during spermiogenesis. We used a novel variation of the subtractive hybridization technique called stepwise subtraction, wherein the subtraction process is systematically repeated in a stepwise manner. We named the genes thus identified as TISP genes (transcript induced in spermiogenesis). The transcription of 80 of these TISP genes is almost completely specific to the testis. This transcription is abruptly turned on after 17 days of age, when the mice enter puberty and spermiogenesis is initiated. Considering that the most advanced cells present at these stages of spermatogenesis are the spermatids, it is likely that we could isolate most of the spermatid-specific genes. DNA sequencing revealed that about half the TISP genes are novel and uncharacterized genes, confirming the utility of the stepwise subtraction approach for gene discovery.

INTRODUCTION

Spermatogonia are derived from the primordial germ cells through a process called spermatogenesis. Male gametes (sperm) subsequently differentiate from the spermatogonia. The first step in spermatogenesis is the arrival of primordial germ cells at the embryonic genital ridge. These germ cells then become incorporated into the sexual cords, which hollow out upon maturity to form seminiferous tubules, the sites of sperm production in the testis. Sertoli cells, which nourish and protect the developing sperm cells, then differentiate from the epithelium of the somatic cell component of the tubules. The ability to identify these developmental stages by microscopic observation allows us to determine precisely when a gene is expressed during development. This means that spermatogenesis is an excellent model system for the identification of the molecular mechanisms that regulate germ-cell differentiation (Hecht, 1998).

Spermatogenesis in the adult animal can be subdivided into three stages. First, after many rounds of mitotic division, the spermatogonia enter meiosis and thus generate the primary spermatocytes. Secondly, the primary spermatocytes undergo two consecutive meiotic divisions and produce four round spermatids. Thirdly, spermiogenesis, which consists of a series of complex morphogenetic events, occurs. This process lasts ∼2 weeks in the mouse and results in the round haploid spermatids developing into morphologically and functionally differentiated spermatozoa. The various morphogenetic events in spermatogenesis appear to be regulated by the organized stage- and cell-specific gene expression in both the germ cells and the supporting somatic cells (Eddy et al., 1993; Eddy and O’Brien, 1998; Hecht, 1998).

During spermiogenesis, histones and non-histone proteins are replaced successively by basic proteins, which are known in round spermatids as transition proteins and in elongating spermatids as protamines (Balhorn, 1989; Hecht, 1995). The genes for these proteins are transcribed within their respective spermatids. The expression of the protamines generates a compacted DNA–protamine complex that may help to safely store chromosomes in the heads of spermatozoa. The complex is also believed to inactivate the transcription of most genes during mid-spermiogenesis (Kierszenbaum and Tres, 1978; Hecht, 1995; Steger, 1999).

The list of genes that are expressed specifically in the mammalian testis is rapidly growing. However, relatively few of these genes have been found to play specific roles in the meiotic phase of spermatogenesis in mammals, and even fewer have been shown to participate in spermiogenesis alone (Eddy and O’Brien, 1998). To identify on a comprehensive scale those genes whose expression is dramatically up-regulated during spermiogenesis, we prepared a subtracted mouse cDNA library enriched in spermiogenesis-specific genes. This was done by using cDNA derived from the testes of adult mice as a tracer and mRNA from the testes of juvenile mice as a driver, given that the haploid spermatid cells are produced only in the adult testes. We then tried to isolate essentially all the genes that are expressed specifically during spermiogenesis in the subtracted cDNA library by a novel variation of the subtraction technique called ‘stepwise subtraction’, in which the subtraction process is systematically repeated in a stepwise manner. This allowed us to isolate 153 mouse genes. DNA sequencing showed that many are uncharacterized novel genes. Of these, 80 genes seem to be specifically expressed during the latter phase of spermatogenesis (spermiogenesis). These observations indicate that our technique is useful for gene discovery.

RESULTS

Stepwise subtraction to isolate genes whose transcription is specifically induced during spermiogenesis

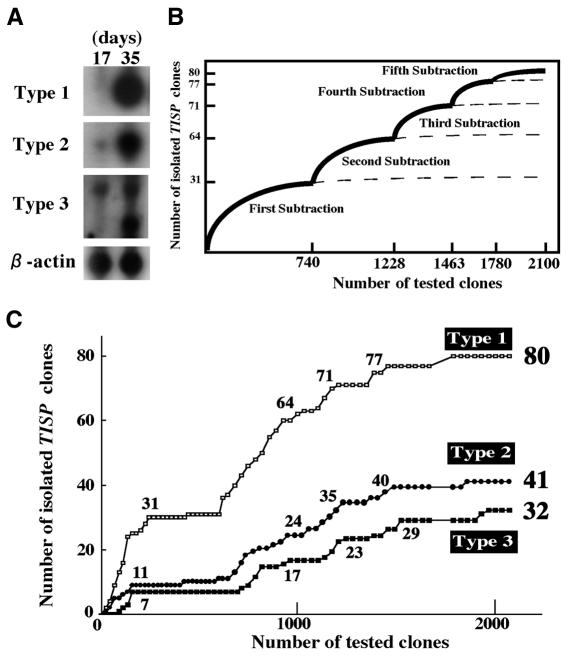

In the present study, we first prepared a cDNA library from adult testes of 35-day-old mice and subtracted it with mRNA from the testes of juvenile (17-day-old) mice. Northern blot analysis indicated that ∼30% of the cDNA clones in the subtracted library were expressed more intensely in the adult testes than in the juvenile testes. These bands could be classified into three types based on the pattern of band intensity (Figure 1A). Type 1 clones showed no expression in the juvenile testis, whereas the expression intensity in the adult testis was very strong. Type 2 clones showed an intense expression in the adult testis, but weak expression in the juvenile testis was also observed. Type 3 clones showed at least two bands, the intensity of one being almost equal in the juvenile and adult testes and the other being found predominantly in the adult testis. We have named all these cDNA clones as TISP clones (transcript induced in spermiogenesis). To assess the effect of the stepwise subtraction on our ability to identify all the potential TISP genes in the library, we plotted the number of TISP clones that were successfully identified at each hybridization step against the total number that had been tested by each step. In the absence of stepwise subtraction, one would see the harvest curve gradually falling and then flattening as the number on the abscissa increases (Figure 1B). Actually, when we plotted the harvest curve for Type 1, 2 and 3 clones isolated at the first subtraction step against the total clones analyzed, we observed a flattened curve in all three cases (Figure 1C). Thus, in the screen of the first-stage subtracted cDNA library, we isolated 31, 11 and seven Type 1, 2 and 3 clones, respectively.

Fig. 1. A stepwise subtraction strategy for comprehensively isolating genes whose transcription is induced during spermiogenesis. (A) The TISP cDNA clones obtained by stepwise subtraction can be classified into three types according to the pattern of band intensity in northern blots with juvenile and adult testicular RNA. A northern blot with radiolabeled β-actin cDNA is shown as a loading control. See text for details. (B) The effect of the stepwise subtractions on the total harvest of TISP clones from the cDNA library can be monitored by plotting the total number of non-redundant cDNA clones analyzed after each stage (abscissa) against the number of TISP cDNA clones that were isolated in each stage (ordinate). The shapes of the harvest curve that might be drawn without performing the stepwise subtractions are shown by broken lines. (C) The actual harvest curve for each type of TISP cDNA clone resulting from performing the five stepwise subtractions. The isolated TISP clones are divided into the three classes. Numbers shown at each node of the curves signify the total number of TISP cDNA clones isolated by the end of each subtraction step. The nodes represent the five hybridizations that were performed on the cDNA library.

When the stepwise subtraction was performed on the first-stage subtracted cDNA library to circumvent the redundant isolation of cDNA clones (see Methods), the harvest curve again started to increase, gradually falling and then flattened. Thus, in the screen of the second-stage subtracted cDNA library, we could isolate another 33 Type 1, 13 Type 2 and 10 Type 3 clones. Similarly, we performed the stepwise subtractions repeatedly to make the fifth-stage subtracted cDNA library and had isolated a total of 80 Type 1, 41 Type 2 and 32 Type 3 cDNA clones. Indicating the success of the five stepwise subtractions in isolating most of the TISP clones in the original library, only 32 of the 320 randomly selected clones in the fifth-stage subtracted cDNA library were unique clones (as assessed by Southern blot analysis), and only three Type 1, one Type 2 and three Type 3 cDNA clones were isolated. This suggests that, by the fifth-stage subtraction, we had isolated almost all of the TISP clones present in the first-stage subtracted cDNA library.

Developmental and tissue-specific expression of TISP cDNA clones

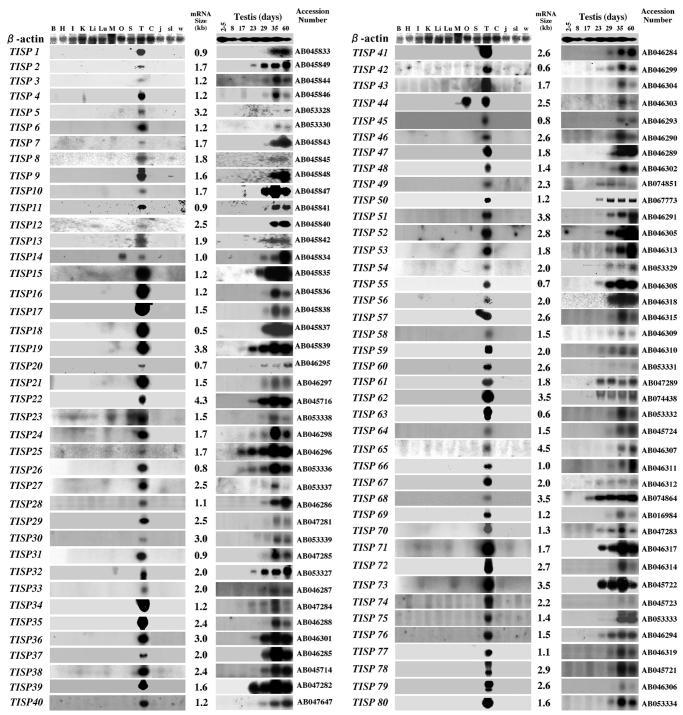

The cDNA inserts in the isolated TISP clones were cut out by digestion with SmaI and NotI restriction enzymes and labeled with 32P. These probes were used for northern blot analysis. Northern blots of the RNA from mouse testis of various ages indicates that expression of all Type 1 TISP genes is very low in the pre-pubertal testis (2–5, 8 and 17 days old) but that transcription of these genes is abruptly induced in the post-pubertal testis (23 days old) and is increased further in the testes of 29-day-old mice (Figure 2). Spermiogenesis occurs only in the postpubertal testis, which suggests that the transcription of many of the Type 1 TISP genes is induced during spermiogenesis. Indeed, northern blot analysis of fractionated samples and in situ hybridization analyses confirm that the transcription of all Type 1 TISP genes examined to date is induced in the germ cells of the postpubertal testis during spermiogenesis (Fujii et al., 1999; Iguchi et al., 1999; Koga et al., 2000; Tosaka et al., 2000; Yamanaka et al., 2000; Carvalho et al., 2002). Northern blot analysis for Type 2 and 3 TISP clones indicate that their expression is not specific to the postpubertal testis during spermiogenesis (see Supplementary figure available at EMBO reports Online). In fact, some of them are expressed even in the infant testis (data not shown), making these clones less interesting for our purposes than the Type 1 TISP clones.

Fig. 2. Expression of each Type 1 TISP cDNA clone. Northern blot analysis was performed by hybridizing the radiolabeled cDNA insert of each TISP clone to RNA from various murine tissues, from the testes of four kinds of mutant mice or from the testes of mice of varying ages. B, brain; H, heart; I, intestine; K, kidney; Li, liver; Lu, lung; M, skeletal muscle; O, ovary; S, spleen; T, testis; C, cryptorchid testis; j, testis of jsd/jsd mouse at 3 months of age; sl, testis of Sl17H/Sl17H mouse; w, testis of W/WV mouse. The number shown at the right of each blot denotes the size of the mRNA as assessed by the RNA size marker run in a parallel lane of each agarose gel (not shown). A northern blot with radiolabeled β-actin cDNA is shown as a loading control. The accession number for each TISP cDNA sequence (registered in the DDBJ data bank) is shown beside each northern blot.

As shown in Figure 2, northern blots using RNA isolated from various murine tissues indicate that all Type 1 TISP clones are expressed predominantly in the testis—except for TISP12, which is also expressed in other tissues (Yamanaka et al., 2000). This suggests that most Type 1 TISP genes function specifically in the testis. TISP14 and TISP44 are exceptional, in the sense that they are also expressed in the ovary, suggesting that they may also play a role in the development of the female gonad. Type 2 and 3 TISP genes appear to be expressed in other tissues as well as in the testis, again making them less interesting (data not shown).

We also analyzed the transcription of TISP clones by northern blot analysis with RNA from testes that cannot produce differentiated germ cells, such as those in cryptorchid (Nishimune et al., 1981), jsd/jsd (Mizunuma et al., 1992; Kojima et al., 1997), Sl17H/Sl17H (Brannan et al., 1992 and W/WV mice (Yoshinaga et al., 1991) (Figure 2). As expected, all Type 1 TISP genes are expressed at almost undetectable levels in these testes, further emphasizing the specific role these genes play in spermiogenesis.

Many of the TISP genes are novel and uncharacterized

DNA sequencing of these genes showed that 30 Type 1, 12 Type 2 and 10 Type 3 TISP genes are identical to the registered genes in the DNA data bank. Of the remaining genes, 12 Type 1, five Type 2 and two Type 3 genes are homologous to previously characterized genes (see Supplementary table). The other 38 Type 1, 24 Type 2 and 20 Type 3 TISP genes are novel and uncharacterized genes. The previously characterized genes include protamine 1 (TISP18), protamine 2 (TISP1) and transition protein 2 (TISP28), all of which are known to play pivotal roles in spermiogenesis (Eddy and O’Brien, 1998; Hecht, 1998). We also encountered genes known to be expressed in a testis-specific manner, including testis-specific phosphoglycerate kinase (TISP4), sperm mitochondrial capsule protein (TISP11), cystatin-related epidermal spermatogenic protein (TISP14), actin-like-7 α and β proteins (TISP61 and TISP19), sperm-egg recognition protein precursor (TISP29), substrate for testis-specific serine kinases Tssk-1 (TISP37) and Tssk-2 (TISP47), testis-specifically expressed cDNAs-2 (Tsec-2; TISP60) and DNA binding protein Hils1 (TISP64) (Eddy et al., 1993; Eddy and O’Brien, 1998; Chadwick et al., 1999). Interestingly, we also isolated the genes for fibrous sheath component (TISP52) and tektin (TISP76), which are potential constituents of the sperm tail (Iguchi et al., 1999). In addition, we identified a splicing isoform of phospholipase C delta 4 (PLC-δ4; TISP30) that is known to be predominantly expressed in the testis and was recently found to function in the acrosome reaction, an exocytotic event required for fertilization (Fukami et al., 2001). These results indicate that the strategy and techniques we used were successful in isolating, on a comprehensive scale, spermiogenesis-specific genes.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report the comprehensive isolation of cDNA clones that putatively encode mouse haploid germ-cell-specific proteins by preparing a spermiogenesis-specific subtracted cDNA library. This library was subjected to a novel variation of the hybridization technique called stepwise subtraction (Figure 1), which allowed us to efficiently isolate 153 genes whose transcription is induced during the spermatogenesis. Among these genes are the 80 so-called Type 1 TISP genes, whose expression is dramatically up-regulated during spermiogenesis in a plus/minus manner. Northern blot analysis during male germ-cell development indicates that the mRNA of these Type 1 TISP genes is detected predominantly in the normal mouse testis but not in the testes of mutant mice known to lack differentiated germ cells in the testis (Figure 2). In addition, it appears that the transcription of all the Type 1 TISP genes is abruptly induced after 17 days of age, at which time spermiogenesis is initiated. This testis-specific expression at the point in development when transcription begins strongly suggests that the 80 TISP genes we identified play major physiological roles in the regulation of spermiogenesis.

DNA sequencing indicated that many of the TISP genes we isolated are novel (see Supplementary table). We analyzed the expression of some of the TISP genes in more detail by northern blot analysis. This indicated that the TISP14 and TISP44 genes are expressed predominantly in both the testis and ovary, suggesting that these TISP genes may be pivotal in both male and female gametogenesis (Figure 2). TISP10, TISP12, TISP15, TISP50, TISP69 and TISP76 genes also showed developmental stage- and location-specific expression (Fujii et al., 1999; Iguchi et al., 1999; Koga et al., 2000; Tosaka et al., 2000; Yamanaka et al., 2000; Carvalho et al., 2002) and may be involved in processes such as supplying energy for sperm motility (TISP12; Yamanaka et al., 2000) and the regulation of polyamine levels in male haploid germ cells (TISP15; Tosaka et al., 2000). Further detailed functional analysis of these novel TISP genes will dramatically expand the current understanding of spermiogenesis at the molecular level.

Recently, it was reported that the X chromosome plays a prominent role in the pre-meiotic stages of mammalian spermatogenesis because, of the 25 genes that are expressed specifically in mouse spermatogonia, three are Y-linked and 10 are X-linked (Wang et al., 2001). However, the chromosomal localizations of TISP genes and some of the haploid-specific genes in the mouse genome (Yoshimura et al., 2001), and the chromosomal positions of the human TISP homologs by using the BLAST network service of NCBI for human genome sequencing (data not shown), indicates that they are scattered throughout the genome and are present on autosomes as well as sex chromosomes. Thus, TISP genes do not appear to be preferentially localized on sex chromosomes.

METHODS

Preparation and analysis of the subtracted cDNA library

An adult testis cDNA library with 2 million independent clones was constructed from 35-day-old mice using the linker-primer method with a pAP3neo vector as described previously (Kobori et al., 1998; Fujii et al., 1999). We next prepared mRNA from the testes of juvenile mice (17 days old) and biotinylated the mRNA with photobiotin. After converting the cDNA library into a single-stranded form by transfection with f1 helper phage, we hybridized it with the biotinylated mRNA and subtracted it by biotin–avidin interaction as described previously (Kobori et al., 1998). The unhybridized clones were converted to the double-stranded form, which was then used to transform competent Escherichia coli cells, generating a subtracted cDNA library of 20 000 independent clones.

To analyze the quality of this first-stage subtracted cDNA library, we prepared plasmid DNA from 740 randomly selected cDNA clones and digested an aliquot of each plasmid DNA with SmaI and NotI restriction enzymes to prepare 10 sheets of Southern blots, each of which included 80 clones arranged in order. We also purified the cDNA inserts of clones 1–20 on 1% agarose gels by digesting them with EcoRI and NotI, and they were then 32P-labeled to use as probes not only for Southern blot analysis to find redundant clones but also for northern blot analysis to identify TISP clones. Each northern sheet included only two lanes—one each with the RNA extracted from the testes of juvenile (17-day-old) and adult (35-day-old) mice (Figure 1A). The DNA sequences of the TISP clones were determined from the 5′ end of the cDNA inserts by the dideoxy-chain termination reaction using an automatic DNA sequencer (Licor 4000L, Lincoln, NE). After these analyses, we selected 20 unhybridized clones by Southern blot analysis (from 21) for the next round of cDNA insert preparation, radiolabeling and northern/Southern blot analysis. This procedure was repeated until we had finished selecting all the unhybridized cDNAs of the 740 clones in Southern blot analysis. In all, we subjected 169 clones to northern/Southern blot analysis.

Stepwise subtraction of the cDNA library

After DNA sequencing of the first-stage subtracted cDNA library, we collected 0.1 µg of each of the 169 plasmid DNAs into one tube, mixed and digested the DNA with NotI and subjected 5 µg to a T7 RNA polymerase reaction to convert the cDNA inserts into the RNA form. The reaction mixture was treated with 70 U of DNase I to remove the DNA substrate. The generated RNA was biotinylated using Photoprobe biotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and mixed with the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) form of the first-stage subtracted cDNA library in 25 µl total volume of hybridization mixture containing 40% formamide, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS and 0.2 M NaCl. In addition, 1 µg of masking oligonucleotide (5′-CCCGGGGATCTAGACGTCGAATTCCC-3′) was added to the mixture to prevent non-specific hybridization via the junctional region between the pAP3neo vector and the cDNA inserts. The reaction mixture was then placed in a FUNA-PCR tube (Funakoshi, Tokyo), heated to 65°C for 10 min and incubated at 42°C for 48 h to allow hybridization between the RNA and ssDNA. After hybridization, we used a modified streptavidin–phenol/chloroform extraction protocol (Sive and St John, 1988) as reported previously (Kobori et al., 1998). The subtracted ssDNA was recovered and converted to the double-stranded form with BcaBEST DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (Kobori et al., 1998). This double-stranded plasmid DNA was used to transform competent E. coli cells by electroporation (Kobori and Nojima, 1993), generating the second-stage subtracted cDNA library, which contained ∼2.0 × 104 independent clones. From this second-stage subtracted cDNA library, we randomly selected 488 clones for plasmid DNA preparation and subjected 259 of them to northern/Southern blot analysis.

To prepare the third-stage subtracted library, we collected 0.1 µg of plasmid DNA from each of the 259 clones, converted them into the RNA form and hybridized with the ssDNA form of the second-stage subtracted cDNA library as described above. To identify novel TISP clones, we randomly selected 235 for plasmid DNA preparation and subjected 84 clones to northern/Southern blot analysis. This procedure was repeated until we obtained a fifth-stage subtracted library. During this process, we randomly selected 317 and 320 clones for plasmid DNA preparation from the fourth- and fifth-stage subtracted libraries, respectively, to identify novel TISP clones and subjected 110 and 32 clones to northern and Southern blot analysis, respectively. To prepare the fourth- and fifth-stage subtracted libraries, we collected 0.1 µg of plasmid DNA for each of 84 and 110 clones, respectively, to convert into RNA form for subtractive hybridization. The third-, fourth- and fifth-stage subtracted cDNA libraries contained ∼1.0 × 104, 1.4 × 104, and 1.2 × 104 independent clones, respectively.

Northern blot analysis

The preparation of RNA from various tissues, the fractionation of germ, Leydig and Sertoli cells from adult mice and northern blot analysis were all performed as described previously (Iguchi et al., 1999; Koga et al., 2000). The cDNA inserts cut out of the plasmids by the SmaI and NotI restriction enzymes were radiolabeled with [32P]dCTP using the Random Primer DNA Labeling kit (TaKaRa) and used as hybridization probes.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EMBO reports Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr P. Hughes for critically reading the manuscript. We also thank Mr I. Nagamori for technical assistance. This work was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and a grant from The Uehara Memorial Foundation (to H.N.).

REFERENCES

- Balhorn R. (1989) Mammalian protamines: structure and molecular interactions. In Adolph, K.W. (ed.), Molecular Biology of Chromosome Function. Springer, New York, NY, pp. 366–395.

- Brannan C.I. et al. (1992) Developmental abnormalities in Steel 17H mice result from a splicing defect in the steel factor cytoplasmic tail. Genes Dev., 10, 1832–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C.E., Tanaka, H., Iguchi, N., Ventelä, S., Nojima, H. and Nishimune, Y. (2002) Biol. Reprod., 66, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick B.P. et al. (1999) Cloning, mapping, and expression of two novel actin genes, actin-like-7A (ACTL7A) and actin-like-7B (ACTL7B), from the familial dysautonomia candidate region on 9q31. Genomics, 58, 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy E.M. and O’Brien, D.A. (1998) Gene expression during mammalian meiosis. In Handel, M.A. (ed.), Meiosis and Gametogenesis. Academic Press, London, UK, pp. 141–200. [PubMed]

- Eddy E.M., Welch, J.E. and O’Brien, D.A. (1993) Gene expression during spermatogenesis. In de Kretser, D.M. (ed.), Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms in Male Reproduction. Academic Press, London, UK, pp. 181–232.

- Fujii T. et al. (1999) Sperizin is a murine RING zinc finger protein specifically expressed in haploid germ cells. Genomics, 57, 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami K. et al. (2001) Requirement of phospholipase Cdelta4 for the zona pellucida-induced acrosome reaction. Science, 292, 920–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht N.B. (1995) The making of a spermatozoon: a molecular perspective. Dev. Genet., 16, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht N.B. (1998) Molecular mechanisms of male germ cell differentiation. BioEssays, 20, 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi N., Tanaka, H., Fujii, T., Tamura, K., Kaneko, Y., Nojima, H. and Nishimune, Y. (1999) Molecular cloning of haploid germ cell-specific tektin cDNA and analysis of the protein in mouse testis. FEBS Lett., 456, 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum A.L. and Tres, L.L. (1978) RNA transcription and chromatin structure during meiotic and postmeiotic stages of spermatogenesis. Fed. Proc., 37, 2512–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori M. and Nojima, H. (1993) A simple treatment of DNA in a ligation mixture prior to electroporation improves transformation frequency. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori M., Ikeda, Y., Nara, H., Kato, M., Kumegawa, M., Nojima, H. and Kawashima, H. (1998) Large scale isolation of osteoclast-specific genes by an improved method involving the preparation of a subtracted cDNA library. Genes Cells, 3, 459–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga M. et al. (2000) Isolation and characterization of a haploid germ cell-specific novel complementary deoxyribonucleic acid; testis-specific homologue of succinyl CoA:3-Oxo acid CoA transferase. Biol. Reprod., 63, 1601–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima Y., Kominami, K., Dohmae, K., Nonomura, N., Miki, T., Okuyama, A., Nishimune, Y. and Okabe, M. (1997) Cessation of spermatogenesis in juvenile spermatogonial depletion (jsd/jsd) mice. Int. J. Urol., 4, 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizunuma M., Dohmae, K., Tajima, Y., Koshimizu, U., Watanabe, D. and Nishimune, Y. (1992) Loss of sperm in juvenile spermatogonial depletion (jsd) mutant mice is ascribed to a defect on intratubular environment to support germ cell differentiation. J. Cell Physiol., 150, 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimune Y., Haneji, T. and Aizawa, S. (1981) Testicular DNA synthesis in vivo: changes in DNA synthetic activity following artificial cryptorchidism and its surgical reversal. Fertil. Steril., 35, 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive H.L. and St John, T. (1988) A simple subtractive hybridization technique employing photoactivatable biotin and phenol extraction. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger K. (1999) Transcriptional and translational regulation of gene expression in haploid spermatids. Anat. Embryol., 199, 471–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosaka Y., Tanaka, H., Yano, Y., Masai, K., Nozaki, M., Yomogida, K., Otani, S., Nojima, H. and Nishimune, Y. (2000) Identification and characterization of testis specific ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (OAZ-t) gene: expression in haploid germ cells and polyamine-induced frameshifting. Genes Cells, 5, 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.J., McCarrey, J.R., Yang, F. and Page, D.C. (2001) An abundance of X-linked genes expressed in spermatogonia. Nature Genet., 27, 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka M. et al. (2000) Molecular cloning and characterization of phosphatidylcholine transfer protein-like protein gene expressed in murine haploid germ cells. Biol. Reprod., 62, 1694–7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura Y., Tanaka, H., Nozaki, M., Yomogida, K., Yasunaga, T. and Nishimune, Y. (2001) Nested genomic structure of haploid germ cell specific haspin gene. Gene, 267, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga K., Nishikawa, S., Ogawa, M., Hayashi, S.-I., Kunisada, T., Fujimoto, T. and Nishikawa, S.-I. (1991) Role of c-kit in mouse spermatogenesis: identification of spermatogonia as a specific site of c-kit expression and function. Development, 113, 689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.