Abstract

Background:

Recommendations for apixaban dosing based on kidney function are inconsistent between the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Optimal apixaban dosing in chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains unknown.

Methods:

Using de-identified electronic health record data from the Optum Labs Data Warehouse, patients with AF and CKD stage 4/5 initiating apixaban between 2013–2021 were identified. Risks of bleeding and stroke/systemic embolism were compared by apixaban dose (5 versus 2.5 mg), adjusted for baseline characteristics by the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Fine-Grey subdistribution hazard model was used to account for the competing risk of death. Cox regression was used to examine risk of death by apixaban dose.

Results:

Among 4313 apixaban new users, 1705 (40%) received 5 mg and 2608 (60%) received 2.5 mg. Patients treated with 5 mg apixaban were younger (mean age 72 versus 80 years), with greater weight (95 versus 80 kg) and higher serum creatinine (2.7 versus 2.5 mg/dL). Mean eGFR was not different between the groups (24 versus 24 ml/min/1.73 m2). In IPTW analysis, apixaban 5 mg was associated with a higher risk of bleeding (incidence rate 4.9 versus 2.9 events per 100 person-years; incidence rate difference [IRD] [95% CI], 2.0 [0.6 to 3.4] events per 100 person-years; subdistribution hazard ratio [sub-HR] [95% CI], 1.63 [1.04 to 2.54]). There was no difference between apixaban 5 mg and 2.5 mg groups in the risk of stroke/systemic embolism (3.3 versus 3.0 events per 100 person-years; IRD [95% CI], 0.2 [−1.0 to 1.4] events per 100 person-years; sub-HR [95% CI], 1.01 [0.59 to 1.73]), nor death (9.9 versus 9.4 events per 100 person-years; IRD [95% CI], 0.5 [−1.6 to 2.6] events per 100 person-years; HR [95% CI], 1.03 [0.77 to 1.38]).

Conclusions:

Compared with 2.5 mg, use of 5 mg apixaban was associated with a higher risk of bleeding in patients with AF and severe CKD, with no difference in the risk of stroke/systemic embolism or death, supporting the apixaban dosing recommendations based on kidney function by EMA, which differ from those issued by the FDA.

Keywords: apixaban, atrial fibrillation, severe chronic kidney disease, medication dose, bleeding, stroke, systemic embolism

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, affecting 37.6 million people worldwide in 2017, and the disease burden is projected to increase by >60% in 2050.1,2 The prevalence of AF is estimated from 16% to 21% in people living with chronic kidney disease (CKD), two- to three-times the burden in the general population.3–6 AF is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including a 5-fold higher risk of stroke/systemic embolism,7,8 and presence of CKD is associated with even higher risk for cardiovascular events such as stroke/systemic embolism and risk of death.4,9

Apixaban is a non-vitamin K-dependent anticoagulant approved for reducing the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular AF, without requirement for therapeutic monitoring.10 It is recommended in clinical guidelines and increasingly prescribed over warfarin for better safety profiles, in addition to superior efficacy and convenience of fixed doses.11–14 However, bleeding risk remains a safety concern in patients with severe CKD (i.e. CKD stage 4/5: estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <30 ml/min/1.73 m2) because impaired kidney function is independently associated with higher risk of bleeding.15 Apixaban trials have excluded patients with Cockroft-Gault estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) <25 mL/min.16–19 Therefore, optimal dosing in severe CKD is unclear owing to the lack of trial data. Post-marketing observational studies focusing on patients with severe CKD are also limited. Determining optimal apixaban dosing is thus of great clinical importance in this high-risk population.

Apixaban dosing recommendations are inconsistent between the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for patients with AF and severe CKD. The FDA indicates dose reduction for apixaban in patients with AF who have ≥2 of the following characteristics: age ≥80 years, body weight ≤60 kg, or serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL.10 On the other hand, the EMA indicates the reduced dose of apixaban for patients with eCrCl 15–30 ml/min.20–22 According to the FDA’s dosing recommendations based on serum creatinine rather than eGFR or eCrCl, some patients with CKD stage 4/5 may be prescribed the standard dose of apixaban (5 mg twice daily) and some may be prescribed the reduced dose of apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily). Of note, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) suggests consideration of the reduced dose of apixaban to reduce risk of bleeding in this population.23

The objective of this study was to evaluate the risks for bleeding (potential harm) and stroke/systemic embolism (potential benefit) associated with two apixaban doses in a large cohort of patients with AF and severe CKD who newly started on apixaban.

METHODS

Data source and study population

This retrospective cohort study used de-identified electronic health record (EHR) data from 40 health systems participating in the Optum Labs Data Warehouse (OLDW). The OLDW database includes longitudinal de-identified administrative claims and EHR data on enrollees and patients, representing a mixture of ages and geographical regions across the United States.24 EHR data contains health care encounters, medication prescriptions, and laboratory measurements. The informed consent was waived as this study used fully de-identified data and presented no more than minimal risk of harm to participants. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review board of Johns Hopkins University. Data are not available per Optum Labs data use agreement; verification analysis requests will be run.

Adult patients with AF and non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5 (defined as eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2) who initiated apixaban (5 mg versus 2.5 mg) between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2021 were eligible for inclusion. The index date was the date of first apixaban prescription. A one-year wash-out period without apixaban prescriptions was required to ensure that the study participants were new apixaban users. Patients were required to have a documented diagnosis of AF by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 9 code 427.3 or version 10 code I48 on or before the index date. The most recent outpatient serum creatinine measurement within one year before or on the index date was used to calculate the eGFR according to the 2021 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine-based equation.25,26 Information on apixaban dose as well as systolic blood pressure and body weight within one year before or on the index date was required. Patients diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism were excluded because apixaban dosing is different (standard dose of 10 mg and reduced dose of 5 mg). Individuals undergoing dialysis and kidney transplant recipients were also excluded. Centers were excluded if there were insufficient affiliated laboratory or vital sign measurements (defined as <5% of the population with serum creatinine or systolic blood pressure) or had ≤10 eligible participants (Figure S1).

Treatment strategies

Apixaban standard dose 5 mg initiation was ascertained from outpatient prescription records, and was compared with reduced apixaban dose 2.5 mg (new users, active comparator design).

Treatment assignment: emulation of randomization by propensity score-based weighting

To account for differences in baseline characteristics between the groups, stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) based on propensity score was applied.27 Propensity score (i.e. the conditional probability of receiving apixaban 5 mg over 2.5 mg given all the measured baseline covariates) was estimated using multivariable logistic regression. Then, stabilized IPTW was derived using the marginal probability of treatment instead of 1 in the weight numerator to improve statistical efficiency.28 Standard mean difference (SMD) was used to examine the balance on measured covariates between the treatment groups, and covariates with absolute SMD less than 10% were considered well balanced.29

The propensity score model included variables (shown in Table 1) that are associated with the risk of bleeding or stroke/systemic embolism, including polynomial terms of age and an interaction term of body weight with serum creatinine (i.e. two patient characteristics to be considered for apixaban dose according to the FDA label), as well as indicators for health systems and the calendar year of apixaban initiation. Demographic information (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), health insurance coverage (categorized as Medicaid, Medicare, commercial, uninsured/unknown), and measurements on body weight, serum creatinine, and systolic blood pressure within one year prior to the index date were extracted from the EHR. The serum creatinine-based eGFR values calculated from 2021 CKD-EPI equation25 were also included. Baseline comorbidities were defined and identified by the presence of relevant diagnostic codes (Table S1) in the problem list, or one inpatient record, or at least two outpatient records within two years before or at the index date.30–33 The Charlson comorbidity index, the weighted sum score of 17 specific comorbid conditions according to the validated ICD-9 and ICD-10 algorithms,30,31 was used to capture overall disease burden. The CHA2DS2-VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and sex category) was included to capture the overall risk of ischemic stroke,32 and the HAS-BLED score (hypertension, abnormal kidney/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio [not included in the score calculation], elderly >65 years, and drugs/alcohol concomitantly) to capture the overall risk of bleeding.33 Use of warfarin, antidepressants, and antibiotics within one year prior to the index date and concurrent use of medications at baseline, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiplatelets (categorized as adenosine diphosphate P2Y12 receptor inhibitors alone, aspirin alone, and dual antiplatelet therapy), statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, insulin, metformin, sulfonylurea, sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA), inhibitors and inducers for cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) enzyme and/or P-glycoprotein (P-gp), were extracted from the outpatient prescription records.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of apixaban initiators (n=1705 with 5 mg and n=2608 with 2.5 mg) before and after the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW)

| Unweighted cohort | Weighted cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban dosing | 5 mg | 2.5 mg | SMD (%) | 5 mg | 2.5 mg | SMD (%) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 72 (9) | 80 (7) | −109.3 | 77 (9) | 77 (9) | 1.3 |

| Female | 53.5% | 58.2% | −9.5 | 58.0% | 56.4% | 3.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 78.0% | 83.3% | −13.6 | 82.1% | 80.5% | 4.0 |

| Black | 15.7% | 9.9% | 17.6 | 11.0% | 12.0% | −3.1 |

| Hispanic | 2.1% | 2.1% | −0.7 | 2.5% | 2.2% | 2.2 |

| Other | 4.3% | 4.6% | −1.5 | 4.4% | 5.3% | −4.2 |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Medicaid | 5.7% | 2.5% | 16.6 | 4.2% | 4.1% | 0.8 |

| Medicare | 58.2% | 66.2% | −16.6 | 61.9% | 62.3% | −0.9 |

| Commercial | 28.3% | 24.5% | 8.6 | 27.0% | 26.4% | 1.4 |

| Uninsured/unknown | 7.8% | 6.8% | 4.1 | 6.9% | 7.3% | −1.4 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Body weight, kg, mean (SD) | 95 (24) | 80 (21) | 69.3 | 87 (22) | 87 (26) | −1.4 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 128 (21) | 128 (20) | 0.6 | 128 (21) | 128 (21) | 1.8 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.5 (0.9) | 19.0 | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.1) | −0.9 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2, mean (SD) | 24 (6) | 24 (5) | 1.5 | 24 (5) | 24 (5) | −0.6 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.8) | 3.0 (1.7) | −5.0 | 3.0 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.7) | 5.3 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, mean (SD) | 3.6 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.5) | −10.9 | 3.7 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.6) | 4.7 |

| HAS-BLED score, mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.6 (0.9) | −16.2 | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.8 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 94.6% | 95.3% | −3.1 | 95.8% | 94.9% | 4.0 |

| Diabetes | 61.8% | 51.6% | 20.7 | 55.8% | 55.6% | 0.4 |

| Coronary heart disease | 68.3% | 69.7% | −3.2 | 69.5% | 68.4% | 2.3 |

| Stroke | 33.2% | 35.7% | −5.3 | 35.1% | 33.9% | 2.7 |

| Heart failure | 62.1% | 66.0% | −8.1 | 65.5% | 64.5% | 2.1 |

| Stroke/systemic embolism hospitalization within 1 year prior | 4.4% | 5.6% | −5.4 | 5.8% | 4.8% | 4.6 |

| Bleeding hospitalization within 1 year prior | 3.6% | 3.5% | 0.3 | 4.1% | 3.6% | 2.6 |

| Alcoholism | 1.9% | 1.0% | 7.7 | 1.5% | 1.3% | 1.1 |

| Medications | ||||||

| ACEI | 15.1% | 11.7% | 10.2 | 12.2% | 12.4% | −0.8 |

| ARB | 13.7% | 12.4% | 3.7 | 12.3% | 13.7% | −4.2 |

| Beta blocker | 21.4% | 19.4% | 5.0 | 19.2% | 19.8% | −1.7 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 20.3% | 17.2% | 8.0 | 17.3% | 18.3% | −2.6 |

| Diuretics | 33.1% | 34.4% | −2.6 | 32.4% | 33.7% | −2.7 |

| Insulin | 21.9% | 14.3% | 20.3 | 17.6% | 17.4% | 0.7 |

| Sulfonylurea | 12.1% | 9.9% | 7.2 | 11.5% | 10.8% | 2.2 |

| Metformin | 8.4% | 4.2% | 18.0 | 5.7% | 5.8% | −0.7 |

| SGLT2i | 0.8% | <0.4%* | 8.7 | 0.6% | 0.7% | −1.4 |

| GLP-1RA | 3.8% | 1.0% | 20.1 | 2.0% | 1.9% | 1.2 |

| Adenosine diphosphate P2Y12 receptor inhibitors alone | 9.3% | 8.9% | 1.2 | 8.6% | 8.8% | −0.7 |

| Aspirin alone | 5.3% | 6.2% | −3.8 | 5.7% | 5.8% | −0.5 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 3.2% | 2.3% | 5.4 | 2.7% | 3.0% | −2.0 |

| Statin | 28.7% | 23.7% | 11.5 | 24.4% | 26.1% | −3.7 |

| NSAIDs | 5.3% | 4.3% | 4.7 | 5.0% | 5.2% | −0.8 |

| CYP3A4/P-gp inducers | <0.6%* | <0.4%* | 1.6 | <0.6%* | <0.4%* | 1.1 |

| CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitor | 34.2% | 29.7% | 9.7 | 29.6% | 30.7% | −2.4 |

| Warfarin use within 1 year prior | 13.8% | 16.8% | 8.4 | 16.1% | 15.7% | 1.2 |

| Antidepressant use within 1 year prior | 16.9% | 15.3% | 4.5 | 16.1% | 16.3% | −0.7 |

| Antibiotic use within 1 year prior | 6.2% | 4.1% | 10.0 | 5.6% | 5.2% | 1.8 |

| Calendar year of initiation | ||||||

| 2013–2015 | 11.4% | 13.3% | −5.9 | 12.1% | 12.1% | 0.2 |

| 2016–2018 | 39.0% | 40.9% | −3.9 | 39.0% | 38.8% | 0.4 |

| 2019–2021 | 49.6% | 45.7% | 7.8 | 48.9% | 29.2% | −0.6 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CHA2DS2-VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75, diabetes, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and sex category; CYP3A4, cytochrome P450 3A4 isozyme; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal kidney/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio (not included in the score calculation), elderly >65 years, drugs/alcohol concomitantly; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2i, sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; SMD, standard mean difference.

Exact proportions cannot be presented due to small cell data policy by Optum Labs.

Note: All characteristics above and indicators for health systems were included in the propensity score model. After weighting, the effective group size was 1636 for the 5 mg dose and 2703 for the 2.5 mg dose.

Outcomes and follow-up

The outcome for potential harm was bleeding at any site, and was ascertained by the primary diagnosis of hospitalization using ICD-9/10 codes (Table S1); these codes were previously shown to have sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 88%, positive and negative predictive values greater than 91% for bleeding-related hospitalization.34,35 The outcome for potential benefit was stroke/systemic embolism, which was captured by the primary diagnosis of hospitalization using a previously validated algorithm (Table S1), with a nearly perfect classification agreement with medical record review.36–38 Secondary outcome was all-cause death. Using the as-treated approach, participants were followed up to the outcome events, death, switching dosage, discontinuation (defined as gap in apixaban therapy >90 days), initiation of other oral anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, etc.), kidney failure (i.e. initiation of dialysis or receipt of kidney transplantation), or last encounters by the data frozen date (February 25, 2022), whichever came first.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize baseline characteristics of the study population by apixaban dose before and after weighting. Means with standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables, percentages for categorical variables, and standardized mean difference (SMD) for assessing covariate balance were reported. In the weighted analysis, Poisson regression was used to estimate incidence rate (IR) of the outcomes per 100 person-years in each group and incidence rate difference (IRD) between the groups. The Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model was used to estimate subdistribution hazard ratios (sub-HR) of bleeding and stroke/systemic embolism, accounting for competing risk of death, with the variance correctly estimated using the robust standard errors.39 Cumulative incidence curves were also depicted for each outcome. Cox proportional regression was used to estimate the risk of death. The proportional hazards assumption was visually evaluated by Schoenfeld residuals and statistically examined by goodness-of-fit tests.

A priori, eight baseline variables were selected for subgroup analyses for each outcome: baseline age (<80 and ≥80 years), body weight (<80 and ≥80 kg: approximate median weight), the FDA dose reduction criteria (with <2 and ≥2 of the following characteristics: age ≥80 years, body weight ≤60 kg, or serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL), sex, diabetes, HAS-BLED score (<3 and ≥3), CHA2DS2-VASc score (<4 and ≥4), and Charlson comorbidity index (<2 and ≥2). For each subgroup analysis, the Cox model with IPTW included an indicator for treatment, an indicator for subgroup, and the product term of these two variables.

A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, an intention-to-treat approach was used. Second, two negative control outcomes (pneumonia and fracture) thought to be unaffected by apixaban dose were used to evaluate for unmeasured or residual confounding. Third, in subgroup analyses, the Cox models with IPTW were further adjusted for covariates that were imbalanced between the treatment groups within subgroups. Fourth, both primary and non-primary inpatient diagnosis codes of stroke/systemic embolism were included in the analysis, to address potential measurement errors in outcome assessment. Fifth, the risk of major bleeding, defined as hospitalization with a primary diagnosis code of intracranial, gastrointestinal, retroperitoneal, intraspinal, intraocular, pericardial, or intra-articular hemorrhage (see a full list of validated diagnosis codes in Table S1) was compared between two dose groups.34,35 Cardiovascular death was further analyzed, which was defined as death within one month after hospitalization for cardiovascular diseases (see related diagnosis codes in Table S1), as well as non-cardiovascular death. In an additional analysis, a wash-out period was used, with three different time windows starting the follow-up one week, one month, and three months after the apixaban initiation. Two-tailed tests with a significance level of 0.05 were used. All analyses were conducted using Stata software (version 16.1; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 4313 patients with AF and non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5 initiated apixaban between 2013 and 2021. Approximately 40% of patients (n=1705) started with a standard dose of 5 mg twice per day and 60% (n=2608) with a reduced dose of 2.5 mg twice per day. The groups differed in 17 of 48 covariates (35%) with SMDs of 10% or greater before weighting (Table 1). In unweighted analyses of the study population, patients treated with the 5 mg of dose were younger (mean age 72 years versus 80 years), had higher body weight (95 kg versus 80 kg) and higher serum creatinine (2.7 mg/dL versus 2.5 mg/dL) than those treated with the 2.5 mg dose. The 5 mg group also had lower HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc scores than the 2.5 mg group (2.4 versus 2.6 and 3.6 versus 3.8, respectively). Mean eGFR was not different between the groups (24 ml/min/1.73 m2 for both). After weighting, the baseline covariates were well balanced.

Risks of bleeding

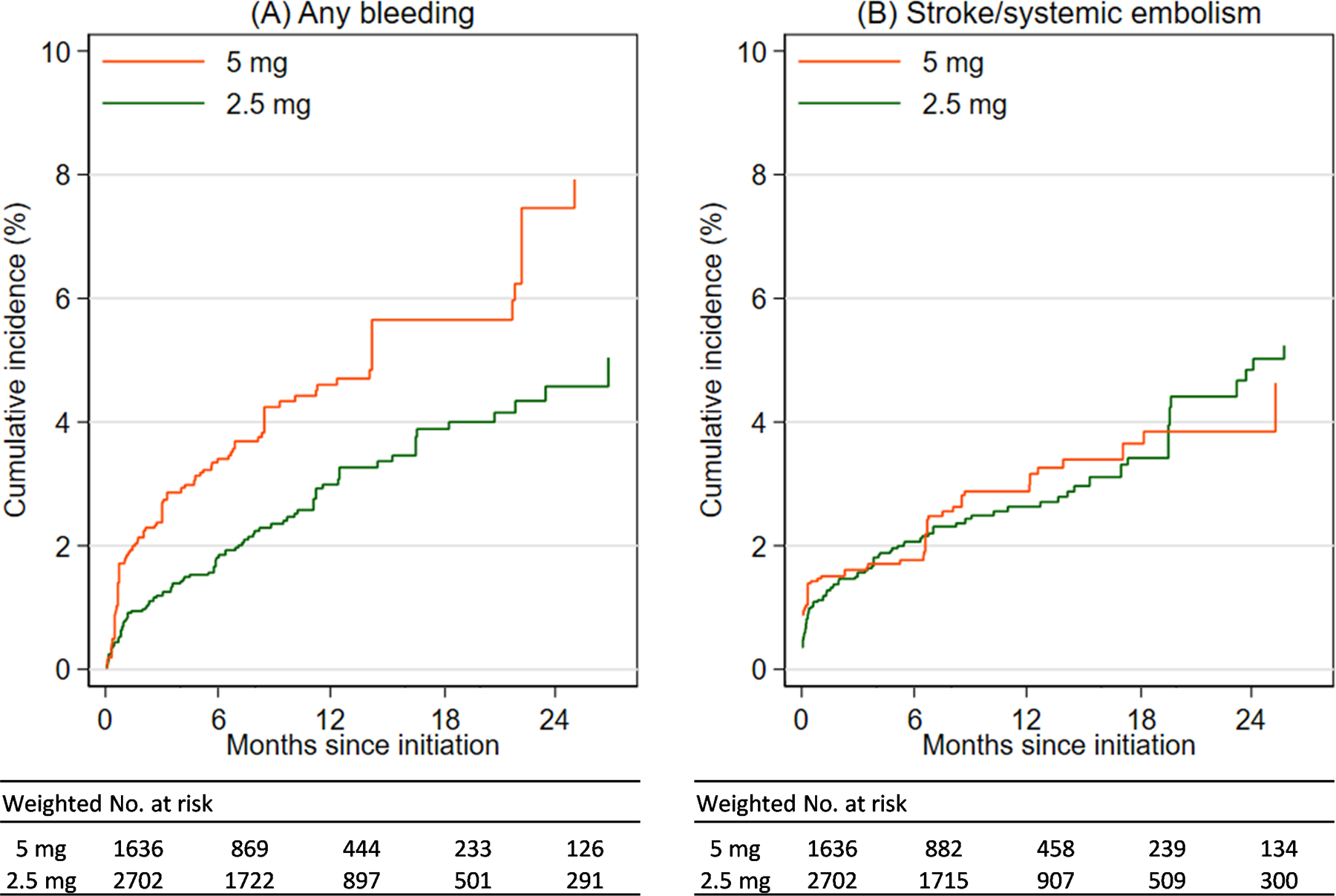

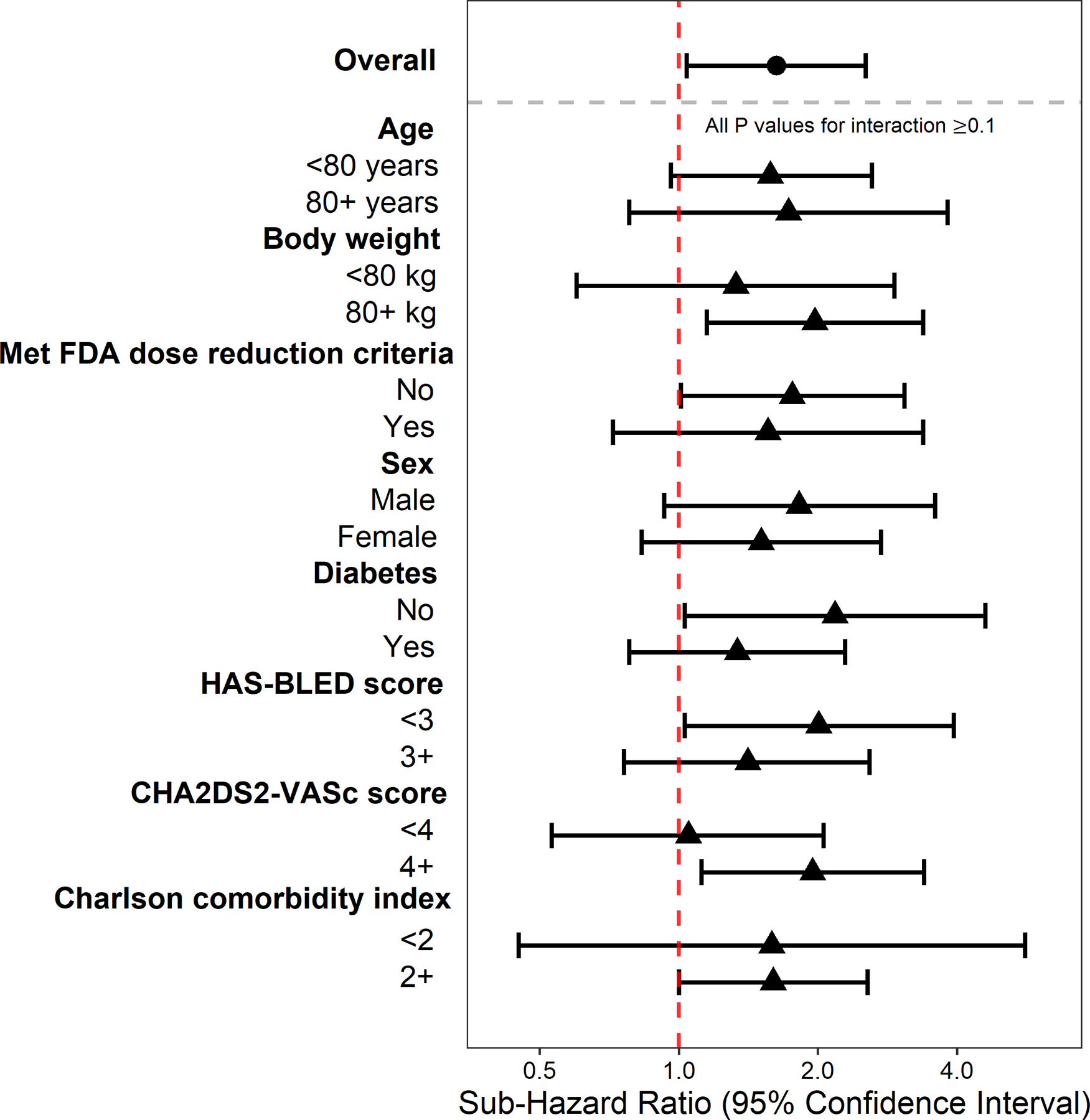

There were 61 (4%) patients on the 5 mg dose versus 81(3%) patients on the 2.5 mg dose who experienced a bleeding-related hospitalization during a median follow-up of 8 months (interquartile interval: 4 to 15 months). Patients who did not experience bleeding events were censored after an initiation of different anticoagulants (0.4%), kidney failure (7.5%), death (8.5%), dosage switch (12.9%), discontinuation (22.3%), or the last encounter (44.8%). In IPTW analyses, treatment with the 5 mg dose was significantly associated with a higher risk of any bleeding compared with treatment with the 2.5 mg dose (Table 2), with an absolute risk difference of 3.1% over a 2-year follow-up (Figure 1A). The results were consistent for major bleeding, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table S2 and Figure S2). The higher risk of bleeding associated with 5 mg apixaban dose was consistent in all subgroups (all p-for interaction ≥0.10, Figure 2 and Figure S3).

Table 2.

Risk of bleeding, stroke/systemic embolism, and death associated with apixaban dose

| Outcome | Unweighted n (%) of events | Weighted incidence rate (95% CI), events per 100 person-years | Weighted incidence rate difference (95% CI), events per 100 person-years | Weighted hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg (N=1705) | 2.5 mg (N= 2608) | 5 mg | 2.5 mg | 5 mg vs. 2.5 mg | 5 mg vs. 2.5 mg | |

| Any bleeding | 61 (4%) | 81 (3%) | 4.9 (3.7 to 6.1) |

2.9 (2.2 to 3.6) |

2.0 (0.6 to 3.4) |

1.63 (1.04 to 2.54) a |

| Stroke/systemic embolism | 39 (2%) | 86 (3%) | 3.3 (2.3 to 4.2) |

3.0 (2.4 to 3.7) |

0.2 (−1.0 to 1.4) |

1.01 (0.59 to 1.73)a |

| Death | 116 (7%) | 288 (11%) | 9.9 (8.2 to 11.6) |

9.4 (8.2 to 10.6) |

0.5 (−1.6 to 2.6) |

1.03 (0.77 to 1.38)b |

The subdistribution hazard ratios of bleeding and stroke/systemic embolism are estimated using Fine-Gray regression model with competing risk of death.

The hazard ratio of death is estimated using Cox proportional regression model.

Figure 1. Weighted cumulative incidence of any bleeding (A) and stroke/systemic embolism (B) by apixaban dose.

Patients with atrial fibrillation and non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease stage 4/5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <30 ml/min/1.73 m2) were followed up since apixaban initiation until the earliest of outcome events, death, switching dosage, discontinuation, anticoagulant type change, kidney failure, or last encounter. The panel figure shows cumulative incidence of any bleeding (A) and stroke/systemic embolism (B) among patients initiating apixaban on 5 mg (orange) and 2.5 mg (green) using as-treated analysis.

Figure 2. Risk of any bleeding by apixaban dose (5 mg versus 2.5 mg) in subgroups of patients with atrial fibrillation and severe chronic kidney disease.

Figure shows subdistribution hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval for any bleeding estimated using Fine-Gray regression model with competing risk of death comparing apixaban 5 mg to 2.5 mg among patients with atrial fibrillation and non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease stage 4/5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <30 ml/min/1.73 m2), overall and among subgroups. All P values for interaction ≥0.1.

Risk of stroke/systemic embolism

There were 39 (2%) patients in the 5 mg dose group versus 86 (3%) in the 2.5 mg dose group who experienced a stroke or systemic embolism over the follow-up period. In IPTW analyses, the risk of stroke/systemic embolism did not differ by apixaban dose (IRD, 0.2 events per 100 person-years, 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 1.4 events per 100 person-years; sub-HR, 1.01, 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.73, Table 2 and Figure 1B). Subgroup analyses showed consistent results (all p-for interaction ≥0.10, Figure S4).

Risk of death

Death occurred in 116 (7%) of the 5 mg dose group versus 288 (11%) of the 2.5 mg dose group. In IPTW analyses, there were no statistical differences observed between the two groups in the risk of death (5 mg versus 2.5 mg dose: IRD, 0.5 events per 100 person-years, 95% CI, −1.6 to 2.6 events per 100 person-years; HR, 1.03, 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.38, Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

Results were consistent in an analysis using an intention-to-treat approach (Table S3 and Figure S5). In subgroup analyses, results were similar after further adjusting for between-subgroup imbalances in covariates (Figure S6–S8). In analyses with negative control outcomes, there were no differences between the two apixaban doses in terms of risk of pneumonia, nor with fracture (Table S4). In the analysis including both primary and non-primary diagnosis codes of stroke/systemic embolism, there was no difference observed in the risk between two dose groups (Table S5). There was no difference in the risk of cardiovascular death between apixaban 5 mg and 2.5 mg dose groups (HR, 1.05, 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.66), nor for non-cardiovascular death (HR, 1.02, 95% CI, 0.70 to 1.48) (Table S6). Analyses applying three different wash-out periods showed consistent results (Table S7).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the associations of apixaban dose (5 mg twice daily versus 2.5 mg twice daily) with bleeding, stroke/systemic embolism, and death, in a geographically diverse US cohort of 4313 patients with AF and non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5 who initiated apixaban. Apixaban 5 mg (versus 2.5 mg) was associated with a 63% higher risk of bleeding, suggesting 1 out of 32 patients prescribed apixaban 5 mg rather than 2.5 mg would be hospitalized for bleeding within 2 years. Higher risk of bleeding associated with 5 mg apixaban was consistently observed in various subgroups of patients, including those who appropriately received 5 mg apixaban according to the FDA dosing recommendations based on age, body weight, and serum creatinine. In contrast, the risk of stroke/systemic embolism and death did not differ by apixaban dose. These findings were robust in both as-treated and intention-to-treat analyses. Taken together, these findings suggest apixaban 2.5 mg may be a better choice to reduce the risk of bleeding for patients with AF and non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5, without diminishing the effectiveness for stroke/systemic embolism prevention.

Clinical trial data on apixaban use in severe CKD are lacking, as major apixaban trials did not include patients with serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL or eCrCl <25 ml/min.16–19 The FDA acknowledges the lack of data to inform apixaban use for patients with eCrCl <15 ml/min, and the FDA label allows patients with non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5 to use a standard or a reduced dose of apixaban because the dose reduction is only recommended for those with at least two of the following characteristics: age ≥80 years, body weight ≤60 kg, or serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL.10 Indeed, in this cohort, almost 40% of patients with severe CKD received a standard dose of apixaban. Among 2305 patients with severe CKD who were recommended to have dose reduction by the FDA labeling, 15% received a standard dose. On the other hand, the EMA recommends a reduced dose of apixaban in patients with eCrCl 15–29 ml/min and no use in those with eCrCl <15 ml/min.20 The inconsistency in dosing recommendations of apixaban based on kidney function reflects the uncertainty about the balance between the potential harm of bleeding and the potential benefit of stroke/systemic embolism prevention in this high-risk population. The KDIGO recommends consideration of apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily in patients with CKD stage 4/5 to reduce risk of bleeding until clinical safety data are available.23

The existing evidence on the comparative safety and efficacy (or effectiveness) of apixaban in severe CKD has been limited to subgroup analyses of clinical trials and relatively small observational studies. Sample size in these studies varied from 40 to 302, which is insufficient to determine whether risk varies by apixaban dose.40–44 One post-hoc analysis of patients with eCrCl 25–30 ml/min in the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial reported higher event rate of bleeding in patients prescribed 5 mg apixaban (n=48) compared with those prescribed 2.5 mg apixaban (n=87) (4.4 versus 3.4 events per 100 person-years), without a definitive conclusion.45 These bleeding rates were similar to the bleeding rates in the present study (4.9 and 2.9 events per 100 person-years for 5 mg and 2.5 mg groups). Of note, mortality rates were higher than bleeding or stroke/systemic embolism rates among patients with severe CKD in both studies. Providers might be reluctant to start anticoagulation for stroke prophylaxis, given the unclear benefits of oral anticoagulation in the population with severe CKD who are at increased risk of death.46 Future studies, including randomized clinical trials, are required to provide guidance on the decision to initiate anticoagulation and which anticoagulant to use in this very high-risk population for death.

There has been even greater uncertainty about whether anticoagulation is warranted in patients dependent on dialysis with AF. Though the risk of stroke/systemic embolism is high in patients requiring dialysis, not all experts endorse use of anticoagulants.8,47 The benefits of anticoagulants in the setting of severe CKD are controversial, with little real-world evidence to inform the debate. Results from analyses of one relatively large cohort of 2351 Medicare patients with AF undergoing dialysis (1034 for 5 mg and 1317 for 2.5 mg) found no difference in bleeding between apixaban doses, but lower risks for ischemic stroke/systemic embolism and death with the standard compared with reduced dose.48 However, hemodialysis does remove some apixaban (~4%) and might offset the elevated apixaban area under the curve caused by poor kidney function.49 Therefore, the outcome data from a dialysis population cannot be extrapolated to non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5 population.

This large population-based study examined different apixaban doses with a focus on patients with AF and CKD stage 4/5, where the evidence is lacking. The geographically diverse sample increases confidence in the generalizability of the study results. The study design, with incident user/active comparators and propensity score-based weighting, minimizes confounding bias. However, there were some limitations. First, medication use was ascertained by prescriptions and thus may not reflect true use (e.g., medication adherence and over-the-counter use of medication cannot be assessed). Second, residual confounding is an inherent limitation of observational studies, despite the rigorous attempts (i.e. IPTW) to minimize treatment by indication bias. However, the null results with two negative control outcomes provide reassurance that results of the present study were robust. Lastly, the follow-up was relatively short. There was no data on out-of-hospital death due to fatal bleeding or stroke/systemic embolism for outcome assessment, and this might underestimate the event rates. Nevertheless, the event rates in the present study were similar to the rates in the severe CKD subgroup of participants enrolled in the ARISTOTLE trial.45 There were few major bleeding events observed in both dose groups, which might limit the statistical power. The hemorrhagic stroke was not separately examined because of the small number of events (<11 events).

In conclusion, results of analyses of this large population-based cohort showed a 1.6 times risk of bleeding associated with 5 mg apixaban (versus 2.5 mg) twice daily in patients with AF and non-dialysis dependent CKD stage 4/5, but no differences in stroke/systemic embolism or death. These findings suggest that a 2.5 mg apixaban may be a better choice than a 5 mg for patients with AF and severe CKD, supporting the KDIGO’s dosing suggestion for this population and apixaban dosing recommendations based on kidney function by EMA, which differ from those issued by the FDA.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

Results from analyses of this large population-based cohort study showed that forty percent of patients with atrial fibrillation and severe chronic kidney disease treated with apixaban were prescribed 5 mg twice daily.

There was a 1.6-fold higher risk of bleeding associated with 5 mg apixaban versus 2.5 mg twice daily in patients with atrial fibrillation and severe chronic kidney disease, but no difference in stroke/systemic embolism or death.

What are the clinical implications?

The US Food and Drug Administration’s recommendations for apixaban dosing based on serum creatinine instead of estimated glomerular filtration rate or creatinine clearance often lead to prescription of apixaban 5 mg twice daily for patients with atrial fibrillation and severe chronic kidney disease.

Apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily versus 5 mg twice daily may reduce the risk of bleeding for patients with atrial fibrillation and severe chronic kidney disease, without increasing the risk of stroke/systemic embolism or death.

Sources of Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by R01 DK115534 and K24 HL155861 (PI: Dr. Grams), and K01 DK121825 (PI: Dr. Shin) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, analyses or interpretation of the data, and preparation or final approval of the manuscript before publication.

Disclosures

A. Chang reports having consultancy agreements with Amgen, Novartis, and Reata; reports receiving research funding from a Novo Nordisk Investigator Sponsored Study; reports having an advisory or leadership role with Reata, Relypsa; and reports having other interests or relationships with National Kidney Foundation grant support and the NKF Patient Network. L. Inker reports having consultancy agreements with Diamtrix; reports receiving research funding to the institution for research and contracts with the National Institutes of Health, National Kidney Foundation, Omeros, Reata Pharmaceuticals; reports having consulting agreements to her institution with Omeros and Tricida Inc.; reports having an advisory or leadership role with the Alport Syndrome Foundation; and reports having other interests or relationships as a member of the American Society of Nephrology, the National Kidney Disease Education Program, and the National Kidney Foundation. M. Grams reports having an advisory or leadership role with AJKD, CJASN, JASN Editorial Board, KDIGO Executive Committee, NKF Scientific Advisory Board, and the USRDS Scientific Advisory Board; and reports having other interests or relationships with grant funding from NKF, which receives funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies, and grant funding from the National Institutes of Health. J. Shin reports receiving research funding from Merck and the National Institutes of Health.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACEi

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor

- AF

Atrial Fibrillation

- ARB

Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker

- ARISTOTLE

Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation

- CHA2DS2-VASc

Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years, Diabetes, prior Stroke/transient ischemic attack, Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, and Sex category

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CKD

Chronic Kidney Disease

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- CYP3A4

Cytochrome P450 3A4

- eCrCl

Estimated Creatinine Clearance

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- HER

Electronic Health Record

- eGFR

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GLP-1RA

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist

- HAS-BLED

Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio, Elderly >65 years, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IPTW

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting

- IR

Incidence Rate

- IRD

Incidence Rate Difference

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

- OLDW

Optum Labs Data Warehouse

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SGLT2i

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor

- SMD

Standardized Mean Difference

- sub-HR

Subdistribution Hazard Ratio

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Cervellin G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke. 2021;16:217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornej J, Börschel CS, Benjamin EJ, Schnabel RB. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st nllCentury. Circulation Research. 2020;127:4–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding WY, Gupta D, Wong CF, Lip GYH. Pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. Cardiovascular Research. 2021;117:1046–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magnocavallo M, Bellasi A, Mariani MV, Fusaro M, Ravera M, Paoletti E, Di Iorio B, Barbera V, Della Rocca DG, Palumbo R, Severino P, Lavalle C, Di Lullo L. Thromboembolic and Bleeding Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: Role of Anticoagulation Therapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ananthapanyasut W, Napan S, Rudolph EH, Harindhanavudhi T, Ayash H, Guglielmi KE, Lerma EV. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation and Its Predictors in Nondialysis Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. CJASN. 2010;5:173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamprea-Montealegre JA, Zelnick LR, Shlipak MG, Floyd JS, Anderson AH, He J, Christenson R, Seliger SL, Soliman EZ, Deo R, Ky B, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, deFilippi CR, Wolf MS, Shafi T, Go AS, Bansal N, Appel LJ, Lash JP, Rao PS, Rahman M, Townsend RR. Cardiac Biomarkers and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation in Chronic Kidney Disease: The CRIC Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, Lau CP, Fain E, Yang S, Bailleul C, Morillo CA, Carlson M, Themeles E, Kaufman ES, Hohnloser SH. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan G-A, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau J-P, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulkarni N, Gukathasan N, Sartori S, Baber U. Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: A Contemporary Overview. J Atr Fibrillation. 2012;5:448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliquis (apixaban) [package insert] Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2012. [cited 2021 Jan 5];Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202155s000lbl.pdf.

- 11.January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140:e125–e151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohnloser SH, Hijazi Z, Thomas L, Alexander JH, Amerena J, Hanna M, Keltai M, Lanas F, Lopes RD, Lopez-Sendon J, Granger CB, Wallentin L. Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2821–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, Gallus AS, Lee TC, Pak R, Raskob GE, Weitz JI, Yamabe T. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:2187–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young A, Phillips J, Hancocks H, Hill C, Joshi N, Marshall A, Grumett J, Dunn JA, Lokare A, Chapman O. OC-11 - Anticoagulation therapy in selected cancer patients at risk of recurrence of venous thromboembolism. Thrombosis Research. 2016;140:S172–S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lip GYH, Frison L, Halperin JL, Lane DA. Comparative validation of a novel risk score for predicting bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation: the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eikelboom JW, O’Donnell M, Yusuf S, Diaz R, Flaker G, Hart R, Hohnloser S, Joyner C, Lawrence J, Pais P, Pogue J, Synhorst D, Connolly SJ. Rationale and design of AVERROES: Apixaban versus acetylsalicylic acid to prevent stroke in atrial fibrillation patients who have failed or are unsuitable for vitamin K antagonist treatment. American Heart Journal. 2010;159:348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener H-C, Hart R, Golitsyn S, Flaker G, Avezum A, Hohnloser SH, Diaz R, Talajic M, Zhu J, Pais P, Budaj A, Parkhomenko A, Jansky P, Commerford P, Tan RS, Sim K-H, Lewis BS, Van Mieghem W, Lip GYH, Kim JH, Lanas-Zanetti F, Gonzalez-Hermosillo A, Dans AL, Munawar M, O’Donnell M, Lawrence J, Lewis G, Afzal R, Yusuf S, AVERROES Steering Committee and Investigators. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:806–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopes RD, Alexander JH, Al-Khatib SM, Ansell J, Diaz R, Easton JD, Gersh BJ, Granger CB, Hanna M, Horowitz J, Hylek EM, McMurray JJV, Verheugt FWA, Wallentin L. Apixaban for Reduction In Stroke and Other ThromboemboLic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: Design and rationale. American Heart Journal. 2010;159:331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FWA, Zhu J, Wallentin L. Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eliquis (Apixaban): product information [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 2];Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/eliquis-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- 21.Reply: Apixaban Dosing in Chronic Kidney Disease: Differences Between U.S. and E.U. Labeling. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69:1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apixaban Dosing in Chronic Kidney Disease: Differences Between U.S. and E.U. Labeling. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69:1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turakhia MP, Blankestijn PJ, Carrero J-J, Clase CM, Deo R, Herzog CA, Kasner SE, Passman RS, Pecoits-Filho R, Reinecke H, Shroff GR, Zareba W, Cheung M, Wheeler DC, Winkelmayer WC, Wanner C, Conference Participants. Chronic kidney disease and arrhythmias: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2314–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Optum Labs. Optum Labs and Optum Labs Data Warehouse (OLDW) Descriptions and Citation. PDF. 2022. Reproduced with permission from Optum Labs. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, Grams ME, Greene T, Grubb A, Gudnason V, Gutiérrez OM, Kalil R, Karger AB, Mauer M, Navis G, Nelson RG, Poggio ED, Rodby R, Rossing P, Rule AD, Selvin E, Seegmiller JC, Shlipak MG, Torres VE, Yang W, Ballew SH, Couture SJ, Powe NR, Levey AS. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C–Based Equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1737–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney inter, Suppl. 2013;3:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, Shetterly S, Blanchette C, Smith D. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health. 2010;13:273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webster-Clark M, Stürmer T, Wang T, Man K, Marinac-Dabic D, Rothman KJ, Ellis AR, Gokhale M, Lunt M, Girman C, Glynn RJ. Using propensity scores to estimate effects of treatment initiation decisions: State of the science. Stat Med. 2021;40:1718–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA. Coding Algorithms for Defining Comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 Administrative Data. Medical Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation Using a Novel Risk Factor-Based Approach: The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, De Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH. A Novel User-Friendly Score (HAS-BLED) To Assess 1-Year Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnason T, Wells PS, Van Walraven C, Forster AJ. Accuracy of coding for possible warfarin complications in hospital discharge abstracts. Thrombosis Research. 2006;118:253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jun M, James MT, Manns BJ, Quinn RR, Ravani P, Tonelli M, Perkovic V, Winkelmayer WC, Ma Z, Hemmelgarn BR, Alberta Kidney Disease Network. The association between kidney function and major bleeding in older adults with atrial fibrillation starting warfarin treatment: population based observational study. BMJ. 2015;350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsieh M-T, Hsieh C-Y, Tsai T-T, Wang Y-C, Sung S-F. Performance of ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Codes for Identifying Acute Ischemic Stroke in a National Health Insurance Claims Database. CLEP. 2020;12:1007–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang TE, Tong X, George MG, Coleman King SM, Yin X, O’Brien S, Ibrahim G, Liskay A, Wiltz JL. Trends and Factors Associated With Concordance Between International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes and Stroke Clinical Diagnoses. Stroke. 2019;50:1959–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT. Validating Administrative Data in Stroke Research. Stroke. 2002;33:2465–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36:4391–4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanton BE, Barasch NS, Tellor KB. Comparison of the Safety and Effectiveness of Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Severe Renal Impairment. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarratt SC, Nesbit R, Moye R. Safety Outcomes of Apixaban Compared With Warfarin in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed D, Palkimas S, Hockman R, Abraham S, Le T, Maitland H. Safety and effectiveness of apixaban compared to warfarin in dialysis patients. Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2018;2:291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herndon K, Guidry TJ, Wassell K, Elliott W. Characterizing the Safety Profile of Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Moderate to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease at a Veterans Affairs Hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schafer JH, Casey AL, Dupre KA, Staubes BA. Safety and Efficacy of Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Patients With Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:1078–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanifer JW, Pokorney SD, Chertow GM, Hohnloser SH, Wojdyla DM, Garonzik S, Byon W, Hijazi Z, Lopes RD, Alexander JH, Wallentin L, Granger CB. Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jegatheswaran J, Hundemer GL, Massicotte-Azarniouch D, Sood MM. Anticoagulation in Patients With Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease: Walking the Fine Line Between Benefit and Harm. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2019;35:1241–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennett WM. Should Dialysis Patients Ever Receive Warfarin and for What Reasons? CJASN. 2006;1:1357–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siontis KC, Zhang X, Eckard A, Bhave N, Schaubel DE, He K, Tilea A, Stack AG, Balkrishnan R, Yao X, Noseworthy PA, Shah ND, Saran R, Nallamothu BK. Outcomes Associated With Apixaban Use in Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation in the United States. Circulation. 2018;138:1519–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vu A, Qu TT, Ryu R, Nandkeolyar S, Jacobson A, Hong LT. Critical Analysis of Apixaban Dose Adjustment Criteria. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2021;27:10760296211021158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.