Abstract

Objective:

Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone produced by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis that is regularly assessed in modern human and non-human populations in saliva, blood, and hair as a measure of stress exposure and stress reactivity. While recent research has detected cortisol concentrations in modern and archaeological permanent dental tissues, the present study assessed human primary (deciduous) teeth for cortisol concentrations.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-one dentine and enamel samples from nine modern and 10 archaeological deciduous teeth were analyzed for cortisol concentrations via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results:

Detectable concentrations of cortisol were identified in 15 (of 32) dentine and 8 (of 19) enamel samples coming from modern and archaeological deciduous teeth.

Conclusions:

This study is the first known analysis of cortisol from deciduous dental tissues, demonstrating the potential to identify measurable concentrations.

Significance:

The ability to analyze deciduous teeth is integral to developing dental cortisol methods with multiple potential future applications, including research on the biological embedding of stress in the skeleton. This study marks a key step in a larger research program to study stress in primary dentition from living and archaeological populations.

Limitations:

Multiple samples generated cortisol values that were not detectable with ELISA. Minimum quantities of tissue may be required to generate detectable levels of cortisol.

Suggestions for Further Research:

Future research should include larger sample sizes and consideration of intrinsic biological and extrinsic preservation factors on dental cortisol. Further method validation and alternative methods for assessing dental cortisol are needed.

Keywords: Glucocorticoid hormone, Dentine, Enamel, Circumpulpal Dentine, Fetus, Dentition

1. Introduction

The influence of stress on health and well-being is an integral research theme in palaeopathology, as well as clinical, biological, and health sciences, often forming the foundation of investigations into the detrimental impact of social inequalities (Ford et al., 2016; Goodman et al., 1984; Goodman and Leatherman, 1998; Larsen, 1997; McDade, 2002; Reitsema and McIlvaine, 2014; Schreier and Evans, 2003; Temple and Goodman, 2014). Cortisol is a key biomarker of stress, being one of the primary hormones produced in response to psychosocial, physiological, and environmental stressors (Charmandari et al., 2005). Cortisol concentrations from bodily fluids (e.g., saliva, blood) and hair are regularly tested in modern human and animal populations as a measure of stress levels (Bozovic et al., 2013; Fischer et al., 2017; Gow et al., 2010; Kambalimath et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2015; Novak et al., 2013; Preis et al., 2019; Šušoliaková et al., 2018; Van Uum et al., 2008). However, studies of stress in past populations and across time have been limited by methodological constraints. For example, in archaeological settings, often only skeletonized individuals are available for analysis. In living populations, retrospective analysis of cortisol is restricted to hair, which may be limited by sample availability and length (Ford et al., 2016; Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2021).

Recently, cortisol concentrations were obtained from permanent tooth structures from modern (Nejad et al., 2016) and archaeological contexts (Quade et al., 2021). However, further investigation is necessary to develop this new methodology and appropriately interpret dental cortisol concentrations. Although as yet untested, there are many potential benefits to examining cortisol in deciduous teeth. Deciduous dental cortisol (DDC) from archaeological contexts could provide productive comparisons with other skeletal stress markers (e.g., dental enamel hypoplasia), or reveal differences in stress experience and frailty not currently accessible through non-destructive methods (Aucott et al., 2008; Baylis et al., 2013; Temple and Goodman, 2014; Wood et al., 1992). Because free cortisol in the bloodstream is hypothesized to be incorporated into tooth structures during tissue development (Balíková, 2005; Camann et al., 2013; Cattaneo et al., 2003; Cippitelli et al., 2018; Gow et al., 2010; Sharpley et al., 2012), DDC could reflect stress exposure during the intrauterine period and early infancy, a critical and sensitive period in development (AlQahtani et al., 2010; Brickley et al., 2020; Camann et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2020; Dunn et al., 2022). Further, DDC has the potential to link paleopathology with studies of stress in living populations, providing new ways to understand the skeletal embodiment of stress. Deciduous teeth from living populations are comparatively abundant and can be ethically sourced (Buikstra et al., 2022; Squires et al., 2022, 2019) from willing and informed donors. Access to larger numbers of teeth permits further testing and validation of the method, which are crucial for advancing the technique. Additionally, living donors can provide relevant demographic and contextual information, including histories of stressful life events.

In this pilot study, we assess human deciduous teeth from living and archaeological populations for cortisol concentrations for the first time, using methods previously applied to permanent teeth (Quade et al., 2021). Our primary aim is to identify if it is possible to detect cortisol concentrations from deciduous teeth, establishing the groundwork for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Six living individuals from the Czech Republic donated nine deciduous teeth. Three individuals provided two teeth each, which were used to test intraindividual differences in DDC concentrations (Table 1). Archaeological teeth came from the 11th-12th century cemetery known as ‘Brno-Vídeňská Street’ (modern Czech Republic) (Černá and Sedláčková, 2016) because of the relatively high number of non-adults with deciduous teeth available for analysis. Ten deciduous teeth were selected from nine non-adults. Skeletal sex was not estimated. In one individual (5813), two teeth were selected for analysis. For individual 4890, the extracted enamel was divided into two samples as a preliminary test for consistency in detection methods.

Table 1.

Number of individuals, teeth, and tissue samples included in this analysis

| Site | Dating | Individuals | Teeth | Circumpulpal Dentine Samples | Dentine Samples | Enamel samples | Total samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brno-Vídeňská Street | 11th–12th c. | 9 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 27 |

| Modern | - | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 24 |

| Total | - | 15 | 19 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 51 |

This research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Living participants provided written informed consent for their teeth to be used in these analyses and all data were stored in compliance with General Data Protection Regulation standards (Masaryk University Research Ethics committee reference number EKV-2021–103).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Tooth sampling

Dentine (D) and enamel (E) samples were extracted from 19 teeth, coming from 15 individuals (Table 1). Circumpulpal dentine (CD) (dentine immediately surrounding the pulp chamber) (Montgomery, 2002) was also extracted and tested for cortisol concentrations (13 samples). It was not always possible to test all tissue types from each tooth due to insufficient or unsuitable sample quality. Each tooth was assessed macroscopically for stage of mineralization (AlQahtani et al., 2010) and signs of pathology (Brothwell, 1981; Hillson, 1996). Only teeth free from visible pathological lesions or wear that exposed the dentine were selected. The entire crown of each selected tooth was utilized, yielding the maximum possible tissue mass, and ensuring the highest likelihood of generating detectable levels of cortisol. The utilization of tissues from different tooth types resulted in variable sample masses, ranging from 2.3 to 297.2 milligrams. Results are reported as initial calculated cortisol concentrations (μg/dL) and as concentrations divided by the respective sample mass to account for these differences, rendering the data comparable.

Selected teeth were photographed (BABAO Working Group for Ethics and Practice, 2019) (Fig. 1), chemically and mechanically cleaned before bisection from crown to root apices. Dental tissues were sequentially removed using a micromotor drill, beginning with circumpulpal dentine, represented by a layer of approximately 0.5 mm of dentine surrounding the crown pulp chamber, followed by dentine and enamel. All tools and surfaces were cleaned between sample preparation to prevent cross contamination (Quade et al., 2021). Each sampled tissue was ground into a powder and placed in 1 mL of methanol for 24 hours to extract the cortisol. After extraction, the samples were dehydrated and frozen until the day of analysis via ELISA.

Fig.1.

A. Individual 4813, Brno-Vídeňská Street. Five surfaces of the 1st left mandibular deciduous molar; B. Individual 9738, Modern. Five surfaces of the 1st left mandibular deciduous molar

2.2.2. Cortisol Analysis

Two competitive ELISA salivary cortisol kits by Salimetrics (USA) were used to quantify the cortisol concentrations in the tooth dentine and enamel. Although no kit has been manufactured to test cortisol in mineralized tissues, salivary kits have been successfully used in modern and archaeological hair and permanent teeth. Future research is needed to investigate any potential error this may introduce. The ELISA kit was run according to the manufacturer’s instructions and wells were read in a Tecan Sunrise™ ELISA plate reader at 450 nm with a secondary filter correction at 490 nm. A standard curve was generated for each kit based on standards and controls, and fourth order polynomial curve fit regressions were produced to define the cortisol concentrations within each sample.

3. Results

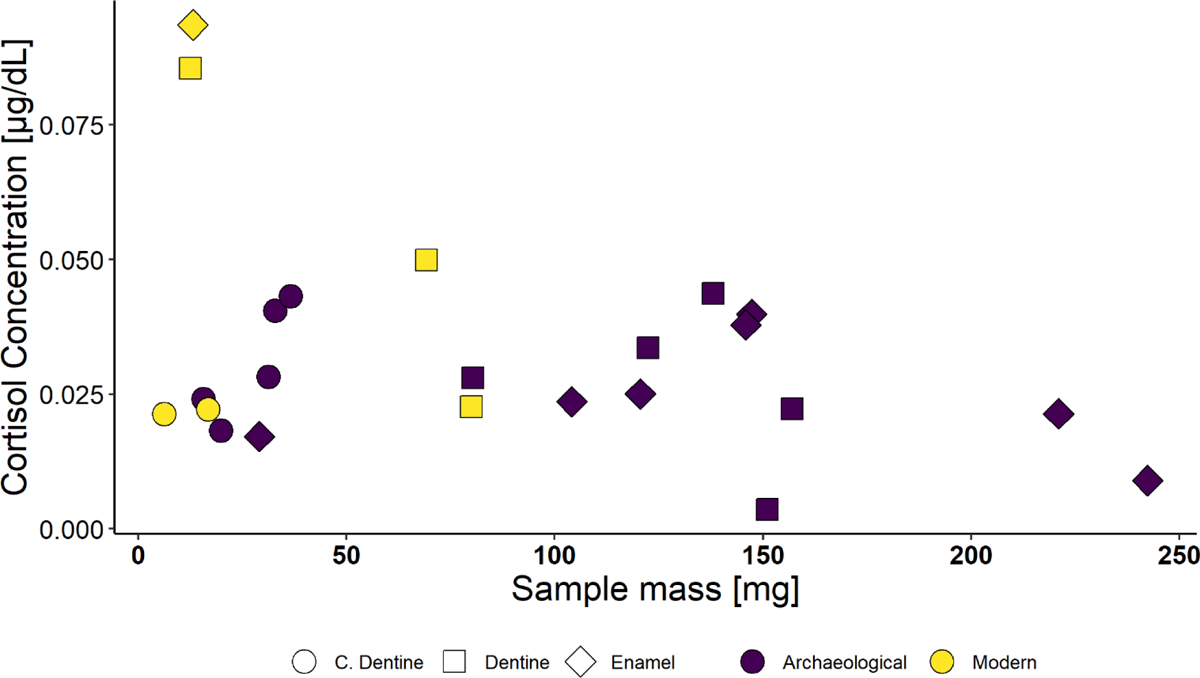

Detectable concentrations of cortisol were identified in 23 out of 51 samples (45%), with measurable results coming from both modern and archaeological deciduous tooth tissues (Figs. 2–3; Tables 2–3). The remaining 28 samples generated cortisol values below the ELISA kit’s minimum detection threshold (0.007μg/dL), meaning they could not be quantified within the parameters of the assay.

Fig. 2.

Samples with detectable levels of cortisol

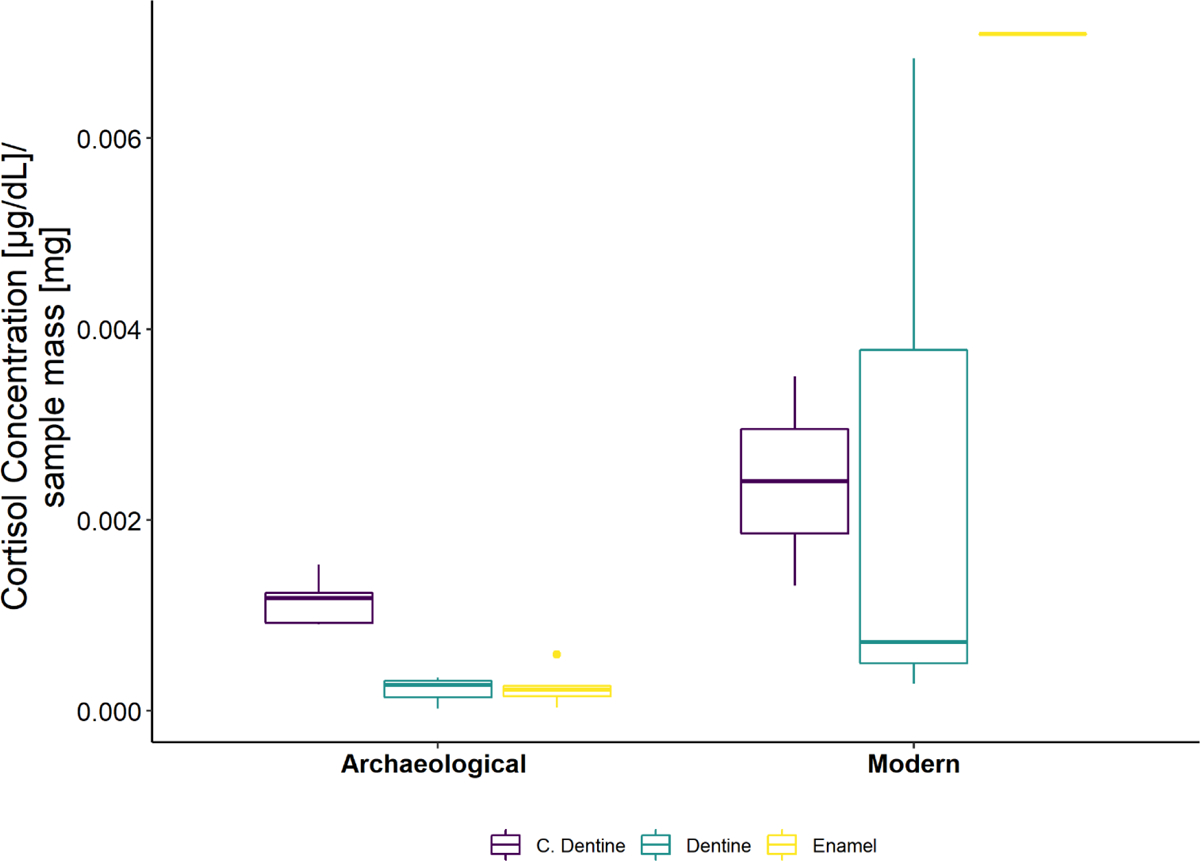

Fig. 3.

Box and whisker plot of samples with detectable levels of cortisol, adjusting for different sample mass. The line in this plot is the sample median, the box represents the second and third quartiles, and whiskers are the maximum and minimum values, not including outliers. Additional dots are outliers.

Table 2.

Dental cortisol concentration results

| Site | Ind. | Sex | Tooth | Circumpulpal Dentine (CD) | Dentine (D) | Enamel (E) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smp Mass mg | Cortisol μg/dL | Cortisol μg/dL/Smp Mass | Smp Mass mg | Cortisol μg/dL | Cortisol μg/dL/Smp Mass | Smp Mass mg | Cortisol μg/dL | Cortisol μg/dL/Smp Mass | ||||

| Brno-Vídeňská | 3000 | ulm2 (65) | 12.5 | ND+ | - | 122.4 | 0.0336 | 0.00027 | 147.4 | 0.0398 | 0.00027 | |

| Brno-Vídeňská | 4813 | llm1 (74) | - | - | 80.5 | 0.0281 | 0.00035 | 120.6 | 0.0250 | 0.00021 | ||

| Brno-Vídeňská* | 4890 | urm2 (55) | 32.8 | 0.0405 | 0.00124 | 156.9 | 0.0223 | 0.00014 | 145.8 | 0.0379 | 0.00026 | |

| - | - | - | - | - | 104.0 | 0.0236 | 0.00023 | |||||

| Brno-Vídeňská | 4892 | urm2 (55) | 15.7 | 0.0241 | 0.00153 | 168.6 | ND | - | 173.8 | ND | - | |

| Brno-Vídeňská | 4895 | ulm2 (65) | 36.5 | 0.0432 | 0.00118 | 138.1 | 0.0437 | 0.00032 | 242.5 | 0.0090 | 0.00004 | |

| Brno-Vídeňská | 4897 | urm2 (55) | 19.8 | 0.0182 | 0.00092 | 151.1 | 0.0035 | 0.00002 | 221.1 | 0.0214 | 0.00010 | |

| Brno-Vídeňská | 5802 | uli1 (61) | 2.3 | ND+ | - | 26.1 | ND+ | - | - | - | - | |

| Brno-Videnska | 5804 | uli1 (61) | - | - | 67.3 | ND+ | - | 45.5 | ND+ | - | ||

| Brno-Vídeňská | 5813 | urm2 (55) | 31.1 | 0.0282 | 0.00091 | 117.7 | ND | - | 126.4 | ND | - | |

| Brno-Vídeňská | 5813 | uri1 (51) | - | - | - | 52.4 | ND+ | - | 29 | 0.0171 | 0.00059 | |

| Detectable | 5 | 5 | 7 | |||||||||

| Total | 9 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| Modern | 3881 | F | lrc (83) | - | - | - | 69.1 | 0.0499 | 0.00072 | 48.9 | ND+ | - |

| Modern | 3937 | F | uli1 (61) | 6.1 | 0.0214 | 0.00350 | 12.5 | 0.0855 | 0.00684 | 13.2 | 0.0935 | 0.00709 |

| Modern | 3937 | F | uri1 (51) | - | - | - | 80.1 | 0.0227 | 0.00028 | 74.3 | ND+ | - |

| Modern | 7650 | M | ulm1 (64) | - | - | - | 94 | ND+ | - | 116.1 | ND | - |

| Modern | 9024 | F | urm2 (55) | 16.1 | ND+ | - | 134.7 | ND | - | 288.4 | ND | - |

| Modern | 9024 | F | lrm2 (85) | 19.8 | ND+ | - | 112.3 | ND | - | 297.2 | ND | - |

| Modern | 9117 | M | lrm2 (85) | 15.4 | ND | - | 166.3 | ND | - | 148.6 | ND | - |

| Modern | 9117 | M | urm2 (55) | 31.1 | ND | - | 118.2 | ND | - | 204 | ND | - |

| Modern | 9748 | F | llm1 (74) | 16.9 | 0.0222 | 0.00131 | 82.4 | ND+ | - | 120.1 | ND | - |

| Detectable | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||

| Total | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 9 | |||||||

Ind=Individual; ND= Not Detectable; Tooth types are abbreviated where the first letter= upper (maxillary) or lower (mandibular), the second letter= side (right or left); the 3rd letter= tooth type (incisor, canine, molar); the 4th character= tooth position number; numbers in parentheses refer to the FDI tooth notation system (FDI, 1971);

denotes sample not tested due to insufficient or unsuitable material;

enamel tissue homogenized and split into two samples to test broad consistency;

indicates samples that did not have detectable levels of cortisol, but which also have notably low sample mass

Table 3.

Dental cortisol concentrations from intraindividual and intra-tooth analyses. Cortisol concentrations are presented as μg/dL divided by sample mass

| Brno-Vídeňská | Modern | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | 4890 | 5813 | 3937 | 9024 | 9117 | |||||

| Tooth | urm2 (55)* | urm2 (55)* | urm2 (55) | uri1 (51) | uli1 (61) | uri1 (51) | urm2 (55) | lrm2 (85) | lrm2 (85) | urm2 (55) |

| Circumpulpal Dentine | - | - | 0.00091 | - | 0.00350 | - | ND+ | ND+ | ND | ND |

| Dentine | - | - | ND | ND+ | 0.00684 | 0.00028 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Enamel | 0.00026 | 0.00023 | ND | 0.00059 | 0.00709 | ND+ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

ND= Not Detectable; Tooth types are abbreviated where the first letter= upper (maxillary) or lower (mandibular), the second letter= side (right or left); the 3rd letter= tooth type (incisor, canine, molar); the 4th character= tooth position number; numbers in parentheses refer to the FDI tooth notation system (FDI, 1971);

denotes sample not tested due to insufficient or unsuitable material;

enamel tissue homogenized and split into two samples to test broad consistency;

indicates samples that did not have detectable levels of cortisol, but which also have notably low sample mass

A larger percentage of archaeological samples generated results with detectable levels of cortisol than modern samples (63% versus 25%)(Fig. 2). When detectable in modern samples, cortisol concentrations were more variable, especially in relation to sample mass (Fig. 3).

Cortisol was detected in 17 archaeological samples (CD-5; D-5; E-7), coming from different individuals and teeth. Six modern samples (CD-2; D-3; E-1) generated results detectable within the assay (Table 2)1. Differences between circumpulpal dentine, dentine, and enamel cortisol concentrations were not formally evaluated due to small sample sizes.

In individual 4890, whose enamel was divided into two separately tested samples, there was consistency in the calculated cortisol concentrations (0.00026; 0.00023 μg/dL/Sample Mass) (Table 3). Four of the detectable modern samples came from individual 3937 in multiple tissues, where cortisol concentrations ranged from 0.00028 (D) to 0.00709 (E).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that it is possible to detect cortisol from deciduous dental tissues in some individuals using methods previously tested in permanent teeth. Archaeological teeth more consistently yielded detectable cortisol results than modern teeth, though cortisol values were higher overall in modern samples. Future studies, particularly with directly comparable datasets and life history measures, can help reveal the full extent to which deciduous teeth record cortisol exposure. To that end, we interpret our results and encourage research in several specific areas.

First, baseline levels of cortisol within dental tissues are unknown. Although cortisol can/should reach every tissue (Beisel et al., 1964; Dallman and Hellhammer, 2011; Kudielka and Kirschbaum, 2005), cortisol may only be detectable in teeth when a person is exposed to a certain degree of stress. This hypothesis may explain why multiple modern and archaeological deciduous teeth had sub-detection levels of cortisol in all tested tissues; and could suggest why several modern individuals, presumably exposed to fewer stressors, had no detectable DDC. In analyses of permanent teeth, not all samples yielded detectable results either (Quade et al., 2021). Therefore, determining ‘expected’ dental cortisol concentrations represents an opportunity for future research.

Second, intrinsic biological factors such as sex or age-related maturational events (Goldstein et al., 2016; Greaves et al., 2014; Kirschbaum et al., 1992; Panagiotakopoulos and Neigh, 2014) may influence DDC. Of the living individuals, only females had detectable DDC, although sample sizes are small, and sex was not estimated for archaeological individuals. Additionally, taphonomic, or diagenetic factors could affect DDC (Cappellini et al., 2018; Hollund et al., 2015; Kendall et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2017; Turner-Walker, 2008). Cortisol is thought to be fairly resistant to degradation (Hamel et al., 2011), but can be affected by long-term exposure to temperatures above 37°C (Khonmee et al., 2020). Although diagenesis in the archaeological teeth was anticipated, those individuals died and were buried with their teeth intact, anchored within the jaw. In contrast, when modern deciduous teeth are exfoliated, they can be conserved in different ways, including boiling or disinfecting teeth. Data related to the storage of modern teeth prior to donation were not collected. This represents a potential problem and future studies will need to explore this hypothesis.2

Third, the current methods may need additional optimization to capture cortisol from dental tissues. As one example: although ELISA kits are extensively tested for cross-reactivity, sensitivity and linearity by kit manufacturers and through independent research (Russell et al., 2015; Slominski et al., 2015), some studies have noted problems and inconsistencies with the comparability and quantification processes (Hendy, 2021). Ultimately, other methods and technologies (e.g., mass spectrometry) may be preferable.

Several limitations of the study are noted. Eleven samples had very small quantities of tissue available for analysis; these samples may have been too small to generate detectable results. Additionally, three living individuals donated multiple teeth, comprising the majority of modern tooth samples (17/24, 71%). Therefore, their teeth could be exerting an undue influence on this analysis.

4.1. Conclusions

This study is the first known analysis of cortisol derived from deciduous dental tissues, acting as a proof of concept for future research. The ability to detect cortisol from deciduous teeth is integral to expanding and developing techniques to assess early life stress, facilitating research on the biological embedding of stress in the skeleton, new methodological approaches, and comparisons with alternative forms of stress evidence from living and archaeological populations.

Acknowledgements

Deepest thanks to all donors; and to Eva Suchánková; Tomáš Kohoutek, Klára Marečková; Zita Goliášová, Marek Joukal (Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University) for their help and support of this project in various stages of development. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their comments that improved this research.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Postdoc2MUNI [grant number CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/18_053/0016952]; and a Wenner-Gren Post PhD Grant [grant number 1248655869]. Dr. Dunn receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (E.C.D., Award Number R21MH129030). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In archaeological samples, the lowest sample masses to yield detectable cortisol concentrations were CD=15.7 mg, D=80.5 mg; E=29 mg. In modern teeth, samples as low as CD=6.1 mg, D=12.5 mg; E=13.2 mg yielded detectable cortisol concentrations.

Modern individual 3937 provided two teeth for analysis, where one (uli1) was processed very shortly after receipt and the second (uri1) several months later. DDC differed between the two teeth, possibly indicating that storage of teeth is an important factor

Declarations of interest:

None

References

- AlQahtani SJ, Hector MP, Liversidge HM, 2010. Brief communication: the London atlas of human tooth development and eruption. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 142, 481–490. 10.1002/ajpa.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aucott SW, Watterberg KL, Shaffer ML, Donohue PK, 2008. Do cortisol concentrations predict short-term outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants? Pediatrics 122, 775–781. 10.1542/peds.2007-2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABAO Working Group for Ethics and Practice, 2019. British association of biological anthropology and osteoarchaeology code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.babao.org.uk/assets/Uploads-to-Web/code-of-ethics.pdf (Accessed: 01 March 2021).

- Balíková M, 2005. Hair analysis for drugs of abuse. Plausibility of interpretation. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czech Republic. 149, 199–207. 10.5507/bp.2005.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis D, Bartlett DB, Syddall HE, Ntani G, Gale CR, Cooper C, Lord JM, Sayer AA, 2013. Immune-endocrine biomarkers as predictors of frailty and mortality: a 10-year longitudinal study in community-dwelling older people. AGE 35, 963–971. 10.1007/s11357-012-9396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisel WR, DiRaimondo VC, Forsham PH, 1964. Cortisol transport and disappearance. Ann. Intern. Med 60, 641–652. 10.7326/0003-4819-58-4-722_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozovic D, Racic M, Ivkovic N, 2013. Salivary Cortisol Levels as a Biological Marker of Stress Reaction. Med. Arch 67, 374–377. 10.5455/medarh.2013.67.374-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley MB, Kahlon B, D’Ortenzio L, 2020. Using teeth as tools: Investigating the mother–infant dyad and developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis using vitamin D deficiency. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 171, 342–353. 10.1002/ajpa.23947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothwell DR, 1981. Digging up bones: the excavation, treatment, and study of human skeletal remains. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Buikstra JE, DeWitte SN, Agarwal SC, Baker BJ, Bartelink EJ, Berger E, Blevins KE, Bolhofner K, Boutin AT, Brickley MB, Buzon MR, de la Cova C, Goldstein L, Gowland R, Grauer AL, Gregoricka LA, Halcrow SE, Hall SA, Hillson S, Kakaliouras AM, Klaus HD, Knudson KJ, Knüsel CJ, Larsen CS, Martin DL, Milner GR, Novak M, Nystrom KC, Pacheco-Forés SI, Prowse TL, Robbins Schug G, Roberts CA, Rothwell JE, Santos AL, Stojanowski C, Stone AC, Stull KE, Temple DH, Torres CM, Toyne JM, Tung TA, Ullinger J, Wiltschke-Schrotta K, Zakrzewski SR, 2022. Twenty-first century bioarchaeology: Taking stock and moving forward. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 178, 54–114. 10.1002/ajpa.24494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camann DE, Schultz ST, Yau AY, Heilbrun LP, Zuniga MM, Palmer RF, Miller CS, 2013. Acetaminophen, pesticide, and diethylhexyl phthalate metabolites, anandamide, and fatty acids in deciduous molars: potential biomarkers of perinatal exposure. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 23, 190–196. 10.1038/jes.2012.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellini E, Prohaska A, Racimo F, Welker F, Pedersen MW, Allentoft ME, de Barros Damgaard P, Gutenbrunner P, Dunne J, Hammann S, 2018. Ancient biomolecules and evolutionary inference. Annu. Rev. Biochem 87, 1029–1060. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo C, Gigli F, Lodi F, Grandi M, 2003. The detection of morphine and codeine in human teeth: an aid in the identification and study of human skeletal remains. J. Forensic Odonto-Stomatol 21, 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Černá L, Sedláčková L, 2016. Nálezová zpráva o provedení záchranného archeologického výzkumu „Bytový dům Vídeňská, III. etapa, Brno” (No. NZ no. A19/16). Archaia Brno o.p.s., Brno.

- Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G, 2005. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu. Rev. Physiol 67, 259–284. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cippitelli M, Mirtella D, Ottaviani G, Tassoni G, Froldi R, Cingolani M, 2018. Toxicological Analysis of Opiates from Alternative Matrices Collected from an Exhumed Body. J. Forensic Sci 63, 640–643. 10.1111/1556-4029.13559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Hellhammer D, 2011. Regulation of the hypothalamopituitary-adrenal axis, chronic stress, and energy: the role of brain networks, in: Contrada RJ, Baum A (Eds.), The Handbook of Stress Science: Biology, Psychology, and Health. Springer Publishing Company, New York, pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA, Mountain RV, Pickett OR, Den Besten PK, Bidlack FB, Dunn EC, 2020. Teeth as potential new tools to measure early-life adversity and subsequent mental health risk: An interdisciplinary review and conceptual model. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 502–513. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Mountain RV, Davis KA, Shaffer I, Smith ADAC, Roubinov DS, Den Besten P, Bidlack FB, Boyce WT, 2022. Association Between Measures Derived From Children’s Primary Exfoliated Teeth and Psychopathology Symptoms: Results From a Community-Based Study. Front. dent. med 3. 10.3389/fdmed.2022.803364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI). 1971. Two-digit system of designating teeth. Int. Dent. J 21, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Duncko R, Hatch SL, Papadopoulos A, Goodwin L, Frissa S, Hotopf M, Cleare AJ, 2017. Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and psychosocial determinants of hair cortisol in a South London community sample. Psychoneuroendocrinology 76, 144–153. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JL, Boch SJ, McCarthy D, 2016. Feasibility of Hair Collection for Cortisol Measurement in Population Research on Adolescent Health. Nurs. Res 65, 249–255. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Holsen L, Huang G, Hammond BD, James-Todd T, Cherkerzian S, Hale TM, Handa RJ, 2016. Prenatal stress-immune programming of sex differences in comorbidity of depression and obesity/metabolic syndrome. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci 18, 425–436. 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.4/jgoldstein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AH, Leatherman TL, 1998. Traversing the chasm between biology and culture: an introduction, in: Leatherman TL (Ed.), Building a New Biocultural Synthesis: Political-Economic Perspectives on Human Biology. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AH, Martin DL, Armelagos George J., 1984. Indications of stress from bones and teeth, in: Cohen MN, Armelagos GJ (Eds.), Paleopathology at the Origins of Agriculture. Academic Press, Orlando, pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gow R, Thomson S, Rieder M, Van Uum S, Koren G, 2010. An assessment of cortisol analysis in hair and its clinical applications. Forensic Sci. Int 196, 32–37. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves RF, Jevalikar G, Hewitt JK, Zacharin MR, 2014. A guide to understanding the steroid pathway: New insights and diagnostic implications. Clin. Biochem 47, 5–15. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel AF, Meyer JS, Henchey E, Dettmer AM, Suomi SJ, Novak MA, 2011. Effects of shampoo and water washing on hair cortisol concentrations. Clin. Chim. Acta 412, 382–385. 10.1016/j.cca.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy J, 2021. Ancient protein analysis in archaeology. Sci. Adv 7, eabb9314. 10.1126/sciadv.abb9314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillson S, 1996. Dental anthropology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Hollund HI, Arts N, Jans MME, Kars H, 2015. Are teeth better? Histological characterization of diagenesis in archaeological bone–tooth pairs and a discussion of the consequences for archaeometric sample selection and analyses. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol 25, 901–911. 10.1002/oa.2376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kambalimath HV, Dixit UB, Thyagi PS, 2010. Salivary cortisol response to psychological stress in children with early childhood caries. Indian. J. Dent. Res 21, 231. 10.4103/0970-9290.66642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall C, Eriksen AMH, Kontopoulos I, Collins MJ, Turner-Walker G, 2018. Diagenesis of archaeological bone and tooth. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 491, 21–37. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.11.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khonmee J, Brown JL, Li M-Y, Somgird C, Boonprasert K, Norkaew T, Punyapornwithaya V, Lee W-M, Thitaram C, 2020. Effect of time and temperature on stability of progestagens, testosterone and cortisol in Asian elephant blood stored with and without anticoagulant. Conserv. Physiol 7. 10.1093/conphys/coz031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Wüst S, Hellhammer D, 1992. Consistent sex differences in cortisol responses to psychological stress.: Psychosom. Med 54, 648–657. 10.1097/00006842-199211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C, 2005. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: a review. Biological psychology 69, 113–132. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen CS, 1997. Bioarchaeology: Interpreting Behavior from the Human Skeleton. Cambridge University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Kim E, Choi MH, 2015. Technical and clinical aspects of cortisol as a biochemical marker of chronic stress. BMB Rep. 48, 209. 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.4.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDade TW, 2002. Status incongruity in Samoan youth: a biocultural analysis of culture change, stress, and immune function. Med. Anthropol. Q 16, 123–150. 10.1525/maq.2002.16.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J, 2002. Lead and strontium isotope compositions of human dental tissues as an indicator of ancient exposure and population dynamics (PhD Thesis). The University of Bradford. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad JG, Jeong C, Shahsavarani H, Sung KIL, Lee J, 2016. Embedded dental cortisol content: a pilot study. Endocrinol. Metab. Syndr 5, 2161–1017. 10.4172/2161-1017.1000240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Hamel AF, Kelly BJ, Dettmer AM, Meyer JS, 2013. Stress, the HPA axis, and nonhuman primate well-being: a review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci 143, 135–149. 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakopoulos L, Neigh GN, 2014. Development of the HPA axis: where and when do sex differences manifest? Front. Neuroendocrinol 35, 285–302. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preis A, Samuni L, Deschner T, Crockford C, Wittig RM, 2019. Urinary Cortisol, Aggression, Dominance and Competition in Wild, West African Male Chimpanzees. Front. Ecol. Evol 7. 10.3389/fevo.2019.00107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quade L, Chazot P, Gowland RL, 2021. Desperately Seeking Stress: A pilot study of cortisol in archaeological tooth structures. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 174, 532–541. 10.1002/ajpa.24157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsema LJ, McIlvaine BK, 2014. Reconciling “stress” and “health” in physical anthropology: What can bioarchaeologists learn from the other subdisciplines? Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 155, 181–185. 10.1002/ajpa.22596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Gonzalez B, Puertas-Gonzalez JA, Gonzalez-Perez R, Davila M, Peralta-Ramirez MI, 2021. Hair cortisol levels in pregnancy as a possible determinant of fetal sex: a longitudinal study. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis 12, 902–907. 10.1017/S2040174420001300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell E, Kirschbaum C, Laudenslager ML, Stalder T, de Rijke Y, van Rossum EF, Van Uum S, Koren G, 2015. Toward standardization of hair cortisol measurement: results of the first international interlaboratory round robin. Ther. Drug Monit 37, 71–75. 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CW, Quataert R, Zalzala F, D’Anastasio R, 2017. Taphonomy of Teeth, in: Schotsman EMJ, Márquez-Grant N, Forbes SL (Eds.), Taphonomy of Human Remains: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, pp. 92–100. 10.1002/9781118953358.ch7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier A, Evans GW, 2003. Adrenal Cortical Response of Young Children to Modern and Ancient Stressors. Curr. Anthropol 44, 306–309. 10.1086/367974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley CF, McFarlane JR, Slominski A, 2012. Stress-linked cortisol concentrations in hair: what we know and what we need to know. Rev. Neurosci 23, 111–121. 10.1515/rns.2011.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski R, Rovnaghi CR, Anand KJ, 2015. Methodological considerations for hair cortisol measurements in children. Ther. Drug Monit 37, 812. https://doi.org/10.1097%2FFTD.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires K, Errickson D, Márquez-Grant N (Eds.), 2019. Ethical Approaches to Human Remains: A Global Challenge in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland. 10.1007/978-3-030-32926-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Squires K, Roberts CA, Márquez-Grant N, 2022. Ethical considerations and publishing in human bioarcheology. Am J Biol Anthropol 177, 615–619. 10.1002/ajpa.24467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šušoliaková O, Šmejkalová J, Bičíková M, Hodačová L, Málková A, Fiala Z, 2018. Assessment of work-related stress by using salivary cortisol level examination among early morning shift workers. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 26, 92–97. 10.21101/cejph.a5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple DH, Goodman AH, 2014. Bioarcheology has a “health” problem: Conceptualizing “stress” and “health” in bioarcheological research. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 155, 186–191. 10.1002/ajpa.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Walker G, 2008. The Chemical and Microbial Degradation of Bones and Teeth, in: Pinhasi R, Mays S (Eds.), Advances in Human Palaeopathology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 3–29. 10.1002/9780470724187.ch1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Uum SHM, Sauve B, Fraser LA, Morley-Forster P, Paul TL, Koren G, 2008. Elevated content of cortisol in hair of patients with severe chronic pain: a novel biomarker for stress. Stress 11, 483–488. 10.1080/10253890801887388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JW, Milner GR, Harpending HC, Weiss KM, Cohen MN, Eisenberg LE, Hutchinson DL, Jankauskas R, Cesnys G, Katzenberg MA, Lukacs JR, McGrath JW, Roth EA, Ubelaker DH, Wilkinson RG, 1992. The Osteological Paradox: Problems of Inferring Prehistoric Health from Skeletal Samples [and Comments and Reply]. Current Anthropology 33, 343–370. 10.1086/204084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]