In the modulator era of cystic fibrosis (CF) care, there are some answers that are clearly established. Elexacaftor (ELX)/tezacaftor (TEZ)/ivacaftor (IVA) therapy significantly increases CFTR (CF transmembrane regulator) protein function for approximately 90% of people with CF (pwCF) who have responsive CF mutations such as the common phe508del mutation (1). It has been shown to significantly improve lung function, reduce pulmonary exacerbations, and improve quality of life (1), with registry data modeling suggesting a substantial increase in life expectancy, possibly to near normal if started in childhood (2). Yet in this translational phase of the era, there are many questions that cannot yet be answered—so many, in fact, that the “state of the art” seems to be coming to terms with this and accepting that attempts to answer new questions only raise even more.

One very important question arose when ELX/TEZ/IVA was first licensed in 2019, with the emergence of case reports and small case series suggesting that some pwCF reported increased depression symptoms in association with initiation (3–8). In this issue of the Journal, Ramsey and colleagues (pp. 299–306) report on a valuable study systematically assessing whether there is any association between ELX/TEZ/IVA use and depression symptoms in pwCF (9). They used four main sources: pooled clinical trial data, registry information and postmarketing surveillance data, and a systematic literature review. The resulting data suggest that depression-related events observed in pwCF taking ELX/TEZ/IVA are generally consistent with the background epidemiology of these events in the CF population.

Reassuring perhaps, but is the question answered? Not quite. There may be a subgroup of pwCF who have worsening depression symptoms masked by a group of patients who experience improvement. Certainly, case reports and small series have suggested that a small proportion of individuals may have worsening depression symptoms that in some cases may improve with dose reduction or cessation of ELX/TEZ/IVA (7, 8). Ramsey and colleagues (9) discount these because of the lack of control groups and the fluctuating nature of depression symptoms, but it would seem wise to gain more data on these individuals before we dismiss these studies completely, as some patients did report subjective benefit from dose reduction or cessation. On the other hand, there are clearly individuals who have reported huge transformative gains in health and quality of life with ELX/TEZ/IVA that would be anticipated to improve mental health. Correspondingly, it might be considered strange that Ramsey and colleagues were unable to show a reduction in depression symptoms overall in pwCF after ELX/TEZ/IVA initiation. In fact, their Figure 1 suggests that the prevalence of depression, certainly in the United States CF Foundation Patient Registry, continues to increase year on year, despite the introduction of ELX/TEZ/IVA. The question of whether this is at least partly due to the additional impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown on mental health remains unanswered.

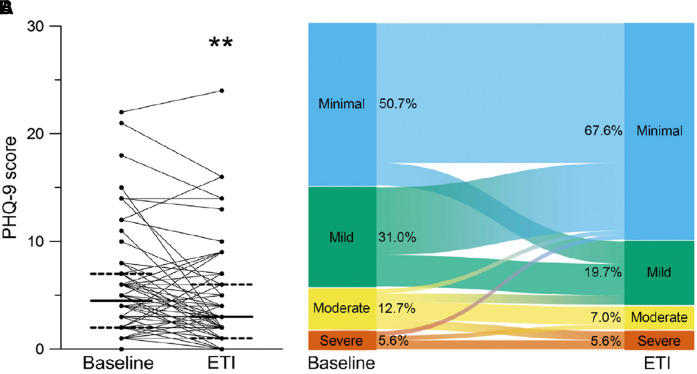

Figure 1.

Effects of ELX/TEZ/IVA on symptoms of depression measured by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score, measured at baseline and at 8–16 weeks after the initiation of ELX/TEZ/IVA in 70 adults with cystic fibrosis. (A) Paired individual PHQ-9 scores. Solid lines represent the group median and dashed lines represent 25th and 75th percentile. (B) Alluvial graphic showing the flow of individuals’ PHQ-9 scores among minimal, mild, moderate, and severe depression symptom categories, demonstrating that a proportion of individuals had worse PHQ-9 scores with ELX/TEZ/IVA therapy. **Denotes P < 0.01 compared with baseline. Reprinted by permission from Reference 11. ELX = elexacaftor; ETI = elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor; IVA = ivacaftor; TEZ = tezacaftor.

The 12 studies assessing change in Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score (the depression symptom module of a wider screening measure) cited by Ramsey and colleagues (in their Table 3) suggest generally reassuring population mean responses, but looking at each study in detail paints a more complex picture (9). Seven of the 12 studies present the ranges of individual changes in PHQ-9 score with ELX/TEZ/IVA initiation, and all seven show a subgroup of pwCF who had worsening depression symptoms associated with initiation (determined by increased PHQ-9 score). Borawska-Kowalczyk and colleagues (10) reported that although there was no overall change in PHQ-9 score, 15% of pwCF had increased scores after ELX/TEZ/IVA initiation. Piehler and colleagues (11) demonstrated clearly that although overall the group showed reduction in depression symptoms as measured by PHQ-9, there was certainly a proportion of subjects who had worse PHQ-9 scores after commencing ELX/TEZ/IVA therapy; indeed PHQ-9 score increased by 17% in the group with minimal depression symptoms at baseline (see Figure 1).

Similarly, Blackwelder and colleagues (12) reported that in adults with low PHQ-9 scores at baseline, scores increased by a mean of 0.53 after ELX/TEZ/IVA initiation, in contrast to a control group of pwCF not taking ELX/TEZ/IVA, who had an average decrease of 0.58, removing a pandemic-effect explanation. Zhang and colleagues (13) reported that although there was no overall significant change in PHQ-9 score, 5% of patients received new mental health diagnoses, and 22% increased, switched, or added psychotropic drugs, suggesting that a subgroup may have had worsening depression symptoms. Pudukodu and colleagues (14) focused their analysis on data that were exclusively prepandemic and reported that 21% of patients initiating ELX/TEZ/IVA therapy had significant increases in PHQ-9 score, balanced by 18% who had significant decreases. A study by Sakon and colleagues (15), although showing a reassuring mean decrease in PHQ-9 score of −1.11, saw a range of −22 to +14, and 9% of respondents reported that ELX/TEZ/IVA therapy had been associated with a decline in mental health. Lastly, Dell and colleagues’ (16) data were collected during the pandemic, and five respondents reported shifts from “normal” to “severe” mental health symptoms associated with ELX/TEZ/IVA initiation.

As the CF community transitions to the new era, there are many things that were known that are no longer known. There are now questions that have no adequate answers. However, this does not mean that helpful responses cannot be generated. Ramsey and colleagues’ (9) paper will reassure the CF community that at a population level, ELX/TEZ/IVA therapy does not appear to be associated with a worsening in depression symptoms. Yet important questions remain. Are a small proportion of individuals particularly prone to mental health issues on ELX/TEZ/IVA, and can we identify them in advance? Are the reported depressive side effects simply a “starting phenomenon” that will improve as the therapy delivering life-changing benefits is continued? Are there any effects on anxiety or behavior in younger children? Questions, questions, questions.

Footnotes

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202311-2159ED on December 19, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Heijerman HGM, McKone EF, Downey DG, Van Braeckel E, Rowe SM, Tullis E, et al. VX17-445-103 Trial Group Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutaton: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet . 2019;394:1940–1948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lopez A, Daly C, Vega-Hernandez G, MacGregor G, Rubin JL. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor projected survival and long-term health outcomes in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for F508del. J Cyst Fibros . 2023;22:607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tindell W, Su A, Oros SM, Rayapati AO, Rakesh G. Trikafta and psychopathology in cystic fibrosis: a case report. Psychosomatics . 2020;61:735–738. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heo S, Young DC, Safirstein J, Bourque B, Antell MH, Diloreto S, et al. Mental status changes during elexacaftor/tezacaftor / ivacaftor therapy. J Cyst Fibros . 2022;21:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arslan M, Chalmers S, Rentfrow K, Olson JM, Dean V, Wylam ME, et al. Suicide attempts in adolescents with cystic fibrosis on elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bathgate CJ, Muther E, Georgiopoulos AM, Smith B, Tillman L, Graziano S, et al. Positive and negative impacts of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor: healthcare providers’ observations across US centers. Pediatr Pulmonol . 2023;58:2469–2477. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spoletini G, Gillgrass L, Pollard K, Shaw N, Williams E, Etherington C, et al. Dose adjustments of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in response to mental health side effects in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros . 2022;21:1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baroud E, Chaudhary N, Georgiopoulos AM. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in adults treated with elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor. Pediatr Pulmonol . 2023;58:1920–1930. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramsey B, Correll CU, DeMaso DR, McKone E, Tullis E, Taylor-Cousar JL, et al. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor treatment and depression-related events. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2024;209:299–306. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202308-1525OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borawska-Kowalczyk U, Walicka-Serzysko K, Postek M, Milczewska J, Sands D. Mental health after initiating triple CFTR modulators in a Polish paediatric cystic fibrosis centre; a preliminary report [abstract] J Cyst Fibros . 2023;22:S170–S171. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piehler L, Thalemann R, Lehmann C, Thee S, Röhmel J, Syunyaeva Z, et al. Effects of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy on mental health of patients with cystic fibrosis. Front Pharmacol . 2023;14:1179208. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1179208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blackwelder J, Indihar V, Finke J, Oder A, Riddle J, Meyers M, et al. Depression and anxiety scores after highly effective cmodulator therapy in pandemic times in an adult cystic fibrosis clinic [abstract] J Cyst Fibros . 2022;21:S188. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang L, Albon D, Jones M, Bruschwein H. Impact of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on depression and anxiety in cystic fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis . 2022;16:17534666221144211. doi: 10.1177/17534666221144211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pudukodu H, Howe K, Donaldson S, Goralski J, Powell M, Wendel K, et al. Worsening anxiety after initiation of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in an adult cohort of patients with cystic fibrosis [abstract] J Cyst Fibros . 2021;20:S135–S136. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sakon C, Vogt H, Brown CD, Tillman EM. A survey assessing the impact of COVID-19 and elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ifavacaftor on both physical and mental health in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol . 2023;58:662–664. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dell M, May A, Pasly KE, Johnson M, Sliemers S, Nemastil CJ, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis after six months on elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry . 2022;63:S119–S120. [Google Scholar]