Abstract

Previous results have implicated an important role for the enzyme IIScr, the sucrose-specific permease, in the transport of sucrose by cariogenic Streptococcus mutans. The product of the scrB gene, sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase (Suc-6PH), is required for the metabolism of phosphorylated sucrose. The results from the utilization of scrB::lacZ fusions in S. mutans GS-5 have suggested that sucrose-grown cells have higher levels of scrB gene expression than do cells grown with glucose or fructose. Northern blot analysis of scrB transcripts has also confirmed the relative strengths of expression as sucrose>glucose>fructose. Immediately downstream from the scrB gene, an open reading frame with homology to regulatory proteins of the GalR-LacI family as well as to ScrR proteins from several other bacteria has been identified. In addition, this gene appears to be transcribed in the same operon as scrB. Inactivation of this gene, scrR, did not alter the relative expression of the scrB gene in the presence of sucrose or fructose but did increase SUC-6PH levels in the presence of glucose to that observed with sucrose. Furthermore, the S. mutans ScrR homolog appears to bind to the scrB promoter region as determined from the results of gel shift assays. These results suggest that the scrR gene is involved in the regulation of scrB, and likely scrA, expression. However, it is not clear whether sucrose acts as an inducer of expression of these genes or, alternatively, whether glucose and fructose act as repressors.

The role of dietary sucrose and mutans streptococci, particularly Streptococcus mutans, in the development of human dental caries has been well documented (14). Sucrose is required by these organisms for the synthesis of insoluble glucans, which play an important role in the colonization of tooth surfaces leading to dental plaque formation. However, under certain conditions, a portion of the sucrose metabolized by the mutans streptococci appears to be converted to fermentation end products such as lactic acid (32). This process likely involves the initial transport of sucrose into the cells by the sucrose phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system (PTS) (28). In addition, alternate pathways for sucrose transport into S. mutans have also been identified (19, 20) and may be prominent under certain environmental conditions as proposed earlier (14).

The sucrose PTS converts sucrose to sucrose-6-phosphate, which is then hydrolyzed to fructose and glucose-6-phosphate, the reaction being catalyzed by the product of the scrB gene, sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase (Suc-6PH) (10, 15). These sugars can then be metabolized to lactic acid through the classical fermentation pathways of the homofermentative streptococci (32). However, it is likely that an alternate sucrose transport system is involved in lactic acid production under rapid growth conditions (7a). Recent results (24) have indicated that the expression of the scrA gene encoding the enzyme IIScr (EnzIIScr) of the sucrose PTS is induced in the presence of sucrose rather than of glucose or fructose. However, a similar analysis of the regulation of scrB expression utilizing reporter gene constructs has not yet been carried out. Earlier results have suggested that this gene may be inducible by sucrose in S. mutans (9, 31). However, this conclusion was based upon nonspecific Suc-6PH (previously termed invertase) assays which could be confounded by the glucosyltransferase (Gtf), fructosyltransferase, and fructanase activities known to be expressed by these organisms (13). However, subsequent utilization of a more specific Suc-6PH assay did confirm that the Suc-6PH activity in the presence of sucrose was elevated relative to that in the presence of fructose and glucose by an unknown mechanism in the mutans streptococci (30). Furthermore, in view of the demonstration that the scrA and scrB genes are tandemly arranged on the S. mutans GS-5 chromosome but are transcribed from opposite DNA strands (23), it was of interest to examine the regulation of expression of the scrB gene.

The present results with specific scrB::lacZ fusions demonstrate that the regulation of scrB expression is similar to that previously demonstrated for the scrA gene (24). In addition, a novel regulatory gene, scrR, has been identified immediately downstream from scrB within the same operon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

S. mutans GS-5, its spontaneous colonization-defective mutant SP2 (18), and the Gtf mutant strain SP2ΔgtfBCD (27a) were maintained and grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) or TYNa (1% Bacto tryptone, 0.5% Bacto yeast extract, and 0.4% Na2HPO4) broth. This latter growth medium is sugar deficient and allows only minimal growth (<10% of that of sugar-supplemented cultures) in the absence of exogenous sugars (24). S. mutans V1355 with an inactivated scrB gene (15) was obtained from F. Macrina (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond). Transformants of S. mutans were selected following growth on THB agar plates supplemented with erythromycin (10 μg/ml) or tetracycline (8 μg/ml).

DNA manipulations.

DNA isolation, endonuclease restriction, ligation, and transformation of competent Escherichia coli cells were carried out as previously described (1, 21) while transformation of S. mutans was accomplished by procedures routinely carried out in this laboratory (18). Nucleotide sequencing and sequence analysis were carried out as indicated earlier (23).

Construction of scrB::lacZ fusion plasmids.

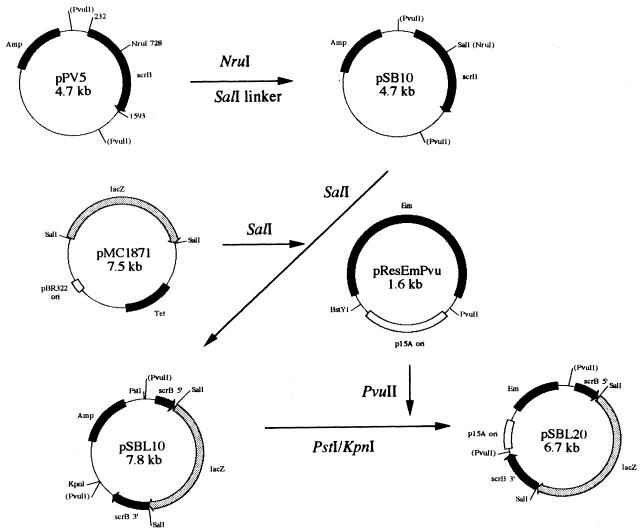

Plasmid pPV5 containing the scrB gene has been described earlier (22). A 10-bp SalI linker was inserted into the NruI site which is present at position 728 of the published scrB nucleotide sequence (22) for constructing plasmid pSD10. The promoterless lacZ SalI cartridge was excised from the pMC1871 fusion vector (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) and inserted in frame into the SalI site of pSB10 (see Fig. 1). A scrB::lacZ fusion fragment digested with PstI and KpnI from pSBL10 was treated with T4 DNA polymerase to obtain blunt ends and ligated to PvuII-digested pResEmPvu (27) with T4 ligase. The resultant plasmid, pSDL20, was used to transform S. mutans SP2, and one selected transformant, designated SP2C4, was used for further study.

FIG. 1.

Construction of pSBL20. A 3.1-kb lacZ cartridge from pMC1871 was inserted in frame into the scrB gene of pSB10. A blunt-ended PstI-KpnI fragment containing the scrB::lacZ fusion was then cloned into the PvuII site of pResEmPvu.

Construction of the scrR-defective mutants.

Plasmid pSYZ4 (21a), containing the 5′ and 3′ ends of the scrR (previously designated ds1, [23]) gene as well as the tetracycline (derived from Tn916) and kanamycin resistance genes (27), served as the source of the former gene. The plasmid was linearized by digestion with EcoRI and used to transform S. mutans SP2C4 such that the resultant scrR mutant (Tetr) was designated SP2CL1. In order to remove the 400-bp fragment of scrR which could express the N-terminal domain of the ScrR protein from the latter construct, an additional scrR mutant was constructed. Chromosomal DNA from SP2CL1 was used to transform strain SP2, and colonies were isolated on Trypticase soy (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) agar plates containing tetracycline (10 μg/ml) and erythromycin (10 μg/ml). The resultant mutant, SP2ΔscrR, lacks the lacZ′ reporter gene and the additional 5′ scrR fragment present in SP2CL1.

Preparation of the labeled scrB PCR probe.

For Southern and Northern blot analyses, a 1,112-bp probe containing the scrB region was prepared and labeled by PCR amplification with pPV5 as the template with primers ScrBORF-F (5′-TCGCCGCTATCAAGATTGGAC-3′; nucleotides 258 to 278 in the scrB sequence [22]) and ScrBORF-R (5′-GCGATCGATCAGAATGGTTCC-3′; nucleotides 1348 to 1369 in the scrB sequence) and digoxigenin-dUTP with the PCR DIG labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation for 5 min at 95°C and 30 cycles of 30 s each at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C, followed by 7 min at 72°C in a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus Corp., Norwalk, Conn.). Amplified products were purified by the Wizard PCR-Prep System (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.).

Southern blot analysis.

One microgram of genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI or EcoRV, and the DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond-N+; Amersham International, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) with 0.4 N NaOH for 3 h, and fixed with a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The blots were hybridized with the digoxigenin-labeled PCR probe at 50°C. Hybridization and detection were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Boehringer Mannheim).

Extraction of RNA.

Total RNA was isolated from 15 ml of log-phase cell cultures. After centrifugation, the cells were suspended with 0.3 ml of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. The samples were transferred to FastRNA tubes with blue caps (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.), and 0.9 ml of TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL) was then added. Cells were broken by a FastPREP FP120 homogenizer (Bio 101) at a speed setting of 6.0 for 30 s. After samples stood on ice for 2 min, 0.2 ml of chloroform was added and the tubes were vortexed for 1 min. The mixtures were then placed at room temperature for 2 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, 0.5 ml of chloroform was added to the supernatant fluids, and the mixtures were vortexed and centrifuged again as described above. RNA was finally precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol, and the resulting pellets were dried and resuspended in 20 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water.

Northern blot analysis.

A quantity (4.5 μl) of RNA (15 μg) was mixed with 15.5 μl of sample buffer (2.0 μl of 10× MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid], 3.5 μl of 37% [vol/vol] formaldehyde, 10 μl of formamide) and denatured at 65°C for 10 min. After dye solution was added, the RNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels containing 3% formaldehyde at 4°C. The gel was washed with 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 15 min twice to remove formaldehyde, and blotting was carried out with 20× SSC overnight. The blotted membrane was washed with dH2O twice for 5 min and fixed by UV cross-linking. Hybridization was then carried out with 50% formamide–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate–5× SSC–10× Denhardt’s solution–10 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 6.5)–salmon sperm DNA (0.1 mg/ml)–digoxigenin-labeled PCR probe at 50°C.

Primer extension analysis.

Total RNA was prepared as described above, and primer extension (11) was carried out with a [32P]dATP (DuPont NEN, Boston, Mass.)-labeled oligonucleotide primer complementary to the 5′ end of the gene (5′-GGTTCTATATGATACGTTGTA-3′; nucleotides 330 to 350 in the scrB sequence) and reverse transcriptase (Superscript II; Gibco BRL). Nucleotide sequencing of the region was carried out in parallel as described above with the same primer.

Gel mobility shift assays.

A 215-bp DNA fragment corresponding to nucleotides 19 to 235 (22) containing the scrA and scrB promoter region was amplified by PCR primers (5′-CTACTTTGCTATAATCCATTTGC-3′ and 5′-CATCGTTTATCTACTCCTAATAA-3′) and 5′ end labeled with 32P with T4 polynucleoside kinase (Gibco BRL). The mobility shift assays were carried out essentially as previously described (6) with 2 to 20 μg of DNA probe (10,000 to 20,000 cpm) and by incubation with the protein samples in 20 μl of reaction buffer (12% glycerol, 12 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.9], 4 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 60 mM KCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM dithiothreitol) at 30°C for 15 min. After incubation, the samples were electrophoresed on 5% polyacrylamide gels and then subjected to autoradiography. For the specificity assays, potential competitors were added on a weight basis relative to the labeled probe.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

RNA from S. mutans SP2 was prepared as described above, and RT-PCR was carried out with Superscript II (Gibco BRL) and Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) as previously described with 35 cycles (denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min) (2). Four synthetic oligonucleotide primers (B-RT1, 5′-ACAACAGTCTCTTTTGCTTGG-3′; B-RT2a, 5′-TCCTGATGGCCGTGTTTATGC-3′; R-RT1, 5′-GAAAACTCTAGGATACAAGCC-3′; and scrR1, 5′-GAAAACTCTAGGATACAAGCC-3′) were used as three primer pairs as described in the text.

Determination of β-galactosidase activity.

S. mutans scrB::lacZ constructs which were precultured overnight in TYNa broth without added sugars were grown in the same broth containing the indicated sugars (1%) into the mid-log phase. Maximum expression of both scrA and scrB occurred at approximately 0.4% glucose or fructose levels, and therefore, 1% levels were chosen for all of the experiments described in this study. Under these conditions, little or no growth was detected in the absence of exogenous carbohydrate addition. Cultures were then centrifuged, and the cell pellets were washed and resuspended with Z buffer (60 mM Na2PO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.0) at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.93 to 0.95. β-Galactosidase activities were determined with o-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG) as follows. The cell suspension (0.1 ml) and 0.9 ml of Z buffer were added to FastRNA tubes. After standing on ice for 30 min, the cells were disrupted by a homogenizer (FastPREP) at a speed setting of 6.0 for 30 s. The samples were then equilibrated at 28°C for 15 min, and 0.2 ml of ONPG (4 mg of ONPG/ml in Z buffer) was next added. The cells were incubated at 28°C for 30 min, and the reactions were terminated by addition of 0.5 ml of 1 M Na2CO3. After being mixed well, the samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min and the optical density at 420 nm of the supernatant fluids was measured spectrophotometrically. All reactions were carried out in triplicate, and the data presented are the averages of the determinations. The units of activity were determined as described earlier (16).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the scrR gene is available from the GenBank database under accession no. U46902.

RESULTS

Construction of scrB::lacZ fusion strains.

In order to develop a system for monitoring specific scrB expression, S. mutans SP2 strains containing scrB::lacZ translational fusions were constructed. The promoterless lacZ gene derived from plasmid pMC1871 was introduced in frame into the scrB gene of plasmid pPV5 (Fig. 1). A blunt-ended fragment from the resulting plasmid, pSBL10, was then introduced into the streptococcal suicide vector pResEmPvu to construct pSBL20. Transformation of S. mutans SP2 (a spontaneous GS-5 mutant which is defective in insoluble glucan synthesis, eliminating aggregation during growth in the presence of sucrose) with intact circular pSBL20 resulted in integration of the plasmid into the SP2 chromosome following a Campbell-like integration event. This resulted in the formation of two copies of the scrB gene: one containing the lacZ fusion and one intact copy of the gene. The latter allows for growth of the construct, SP2C4, in the presence of sucrose since the disaccharide is toxic to cells lacking Suc-6PH activity (15). Transformants selected on THB-erythromycin agar plates containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) allowed for convenient isolation of the proper constructs.

Confirmation of integration of pSBL20 into the SP2 chromosome was obtained following Southern blot analysis of the transformants (data not shown). Cleavage of SP2 and SP2C4 chromosomal DNA with EcoRI or EcoRV and analysis with an scrB probe yielded the predicted fragments (SP2 yielded one positive 6.6-kb fragment while the mutant SP2C4 expressed two bands, of 3.7 and 6.9 kb, following EcoRI digestion).

Regulation of scrB expression.

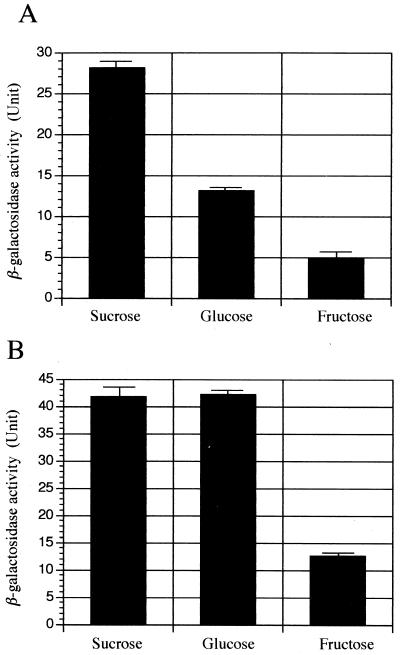

Since previous results (24) indicated that another gene involved in sucrose transport, scrA encoding EnzIIScr, was differentially regulated by sugars, it was of interest to examine the effects of various sugars which S. mutans would be expected to encounter in the oral cavity on scrB expression. With SP2C4, it was demonstrated that maximal scrB expression was detected when the cells were grown in the presence of sucrose (Fig. 2A). Expression was approximately twice as high in the presence of sucrose as in that of glucose and almost fivefold higher relative to growth in the presence of fructose. Growth of the cells in the presence of sucrose plus glucose or sucrose plus fructose resulted in scrB expression similar to that with growth in the presence of glucose or fructose alone, respectively (data not shown). In addition, growth of SP2C4 in the presence of either maltose or sorbitol resulted in a Suc-6PH level similar to that of cells grown in the presence of fructose (data not shown). This latter result is in contrast to previous studies indicating higher levels of scrB expression in mannitol- or sorbitol-grown cells than those in fructose-grown cells (30). Whether this difference is related to the utilization of distinct species of mutans streptococci in these two studies is unknown at present.

FIG. 2.

β-Galactosidase activities of S. mutans SP2C4 (scrB::lacZ) (A) and SP2CL1 (scrB::lacZ scrR mutant) (B). S. mutans strains were grown in TYNa broth with 1% sucrose, glucose, or fructose as described in the text.

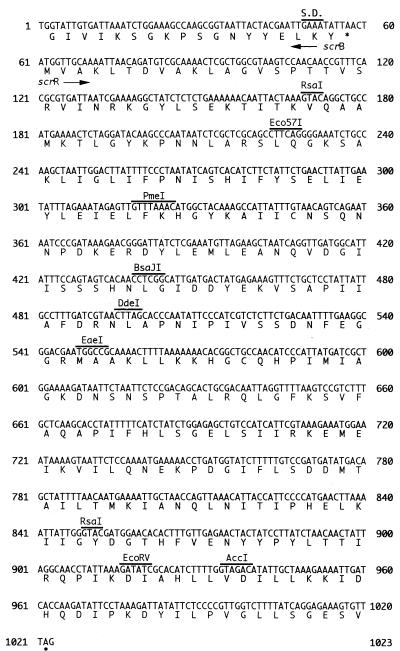

Since bacteria present in dental plaque are subject to fluctuations in pH influenced by the availability of nutrients (14), it was of interest to determine the effects of acidity on scrB expression. The availability of S. mutans scrA::lacZ constructs (24) also allowed for a similar analysis of this gene. The results (Fig. 3) clearly indicated that the expression of both the scrA and scrB genes was reduced under acidic conditions, pH 5.6, relative to neutral pH. Thus, two of the key enzymes involved in the major sucrose transport and metabolism system of S. mutans appear to be down regulated under acidic growth conditions.

FIG. 3.

Relative β-galactosidase activities of S. mutans IS3AZ4 (scrA::lacZ) and SP2CL1 (scrB::lacZ) grown at different pHs in 1% glucose. Each strain was inoculated into THB at pH 7.0 (A) or pH 5.6 (B). Cells were harvested at mid-log phase, and the activities were measured as described in the text. Relative activities (percent) were calculated with the activity at pH 7.0 set at 100% for each strain.

Identification and characterization of the scrR gene.

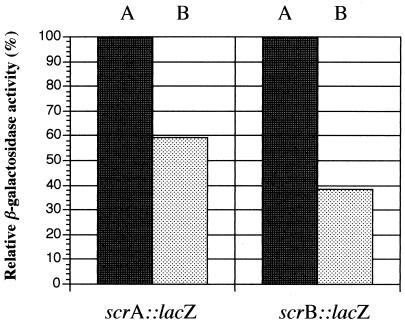

The apparent inducibility of the scrB gene with different sugars suggested the presence of a scrB regulatory gene on the S. mutans chromosome. Sequencing of the scrB gene (22) revealed the presence of an open reading frame (ORF) previously named ds1 immediately downstream from the gene. Additional nucleotide sequencing (Fig. 4) confirmed the presence of a significant ORF in this region. This putative gene would code for a protein of approximately 35 kDa beginning at nucleotide position 61. A potential Shine-Dalgarno sequence, AGG, which was present within the 3′ end of the scrB gene, was detected 5 nucleotides upstream of the likely initiation codon. This suggested the possibility of translational coupling of the scrB gene and the ORF. In addition, no sequences similar to promoter sequences were identified in the region upstream of the ds1 gene, and this suggested that both genes may be present within the same operon.

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide sequence of the scrR gene and the deduced amino acid sequence. The putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence (S.D.) and restriction enzyme sites are shown.

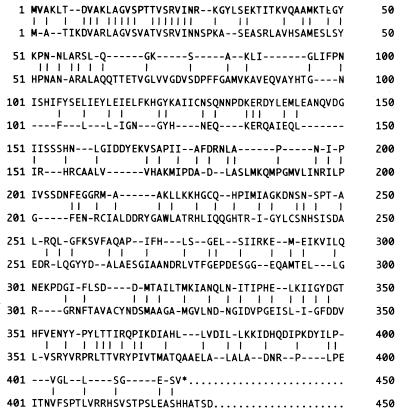

A comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of ds1 with the National Biomedical Research Foundation protein database indicated that extensive homology was observed between the S. mutans ds1 protein and the N-terminal regions of the GalR-LacI family (17) of regulatory proteins (Fig. 5). However, this homology did not extend beyond the N-terminal region. Since the N-terminal region of the GalR-LacI family of regulatory proteins has been implicated in DNA binding, these results suggested that the S. mutans ORF might also be involved in such interactions. Therefore, this ORF was tentatively named scrR since it appeared to be a regulatory gene present in the same operon as scrB. Moreover, the S. mutans ScrR protein exhibited homology with other DNA-binding proteins including the DegA regulatory protein of Bacillus subtilis (32% identity [4]), as well as the ScrR proteins of Staphylococcus xylosus (8) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (12), with 25 and 26% identity, respectively. In addition, the S. mutans gene is highly homologous (50.8% identity) with that for the recently identified ScrR protein from Pediococcus pentosaceus (SwissProt accession no. P43472).

FIG. 5.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of S. mutans scrR (top) and E. coli galR (bottom).

Role of ScrR in the regulation of ScrB expression.

In order to determine if ScrR plays a role as a regulatory protein in affecting scrB expression, an ScrR mutant was constructed. For this purpose, an RsaI Tetr gene cassette was introduced into the scrR gene to produce plasmid pSYZ4 (Fig. 6). Linearization of plasmid pSYZ4 with EcoRI and transformation of strain SP2C4 resulted in the introduction of the Tetr gene into the S. mutans chromosome following a double-crossover recombination event. Tetr transformants were then analyzed for the predicted integration event following Southern blot analysis (data not shown). With an scrB gene probe, it was demonstrated that the predicted hybridizing fragments were observed following cleavage of the chromosomal DNA from one of the Tetr transformants, SP2CL1, with either EcoRI or EcoRV (i.e., EcoRI produced 3.7- and 10.9-kb hybridizing bands compared to 3.7- and 6.9-kb bands for SP2C4).

FIG. 6.

Integration of linearized pSYZ4 into S. mutans (S.m.) SP2C4. Plasmid pSYZ4 containing the 5′ and 3′ ends of scrR was linearized with EcoRI and transformed into S. mutans SP2C4. The resultant scrR mutant was designated SP2CL1. Abbreviations for restriction endonuclease sites: EI, EcoRI; R, RsaI; H, HindIII.

Growth of strain SP2CL1 (scrB::lacZ scrR::tet) in the presence of different sugars (Fig. 2B) indicated that glucose and sucrose were equally effective in inducing scrB expression relative to that with fructose. Thus, inactivation of scrR appeared to increase the ability of glucose to elevate scrB expression relative to that with sucrose and fructose. Alternatively, if glucose is a repressor of scrB expression, the scrR mutation abolishes such repressive effects. Lactose, maltose, and sorbitol behaved like fructose in affecting scrB expression in the scrR mutant (data not shown).

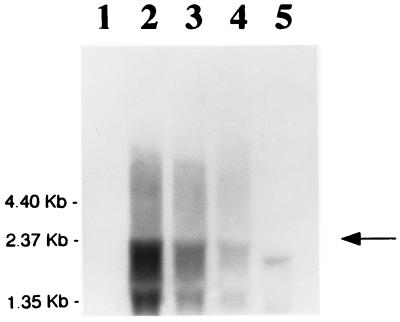

Transcriptional regulation of scrB expression.

In order to determine if the differential regulation of scrB expression by the sugars occurs at the level of transcription, Northern blot analysis was carried out (Fig. 7). Two major mRNA bands corresponding to the scrB transcript of 2.37 and 1.35 kb were identified. The smaller species may represent binding of the probe to rRNA or a degraded mRNA, although the distinct size of this band suggests that the former possibility is more likely. It is also possible that this species could represent a product of alternate transcription initiation or termination. The larger transcript is compatible in size with an mRNA containing both the scrB and the scrR genes. Maximal expression of the scrB transcript occurs in the presence of sucrose, lower levels occur for cells grown in the presence of glucose, and only trace amounts of mRNA occur in the presence of fructose. Cells cultured in the absence of exogenous sugars (Fig. 7, lane 1) or sucrose-grown cells of the scrB mutant V1355 (lane 5) displayed no detectable levels of the transcripts. These results confirm those from the translational fusion studies and further indicate that the sugars affect scrB expression at the transcriptional level. However, it is not clear whether these effects result from repression or from induction by the sugars.

FIG. 7.

Northern blot analysis of the S. mutans SP2ΔgtfBCD RNA with a digoxigenin-labeled scrB probe. The cells were grown in TYNa broth containing 1% sucrose (lane 2), glucose (lane 3), or fructose (lane 4). Cells inoculated without any sugar (lane 1) and S. mutans V1355 cultured with sucrose (lane 5) were used as negative controls. Arrow indicates scrB transcript.

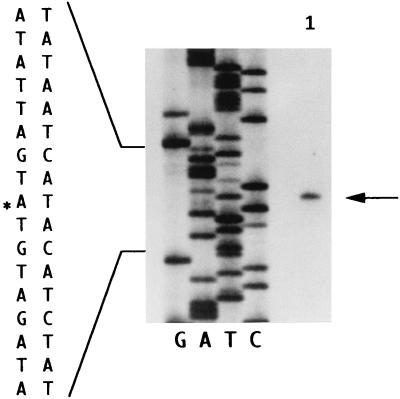

Since the transcription start site for the scrB gene had not yet been identified and such a determination might provide information regarding how the gene was regulated, primer extension analysis of the scrB transcript was carried out (Fig. 8). The results clearly identified an A residue at position 198 of the previously published scrB sequence (22) as the initiation site. Based upon this transcription start site, putative −10 (TACTAT) and −35 (TTGATT) regions were identified (see reference 22 for the scrB sequence). Neither of these regions overlapped the deduced −10 and −35 regions of the divergently transcribed scrA gene (10a).

FIG. 8.

Primer extension analysis of the scrB gene. A labeled 21-mer oligonucleotide primer complementary to nucleotides 330 to 350, 132 bp from the initiation codon of the scrB gene (22), was used to define the transcription start site indicated in lane 1. Asterisk indicates start site.

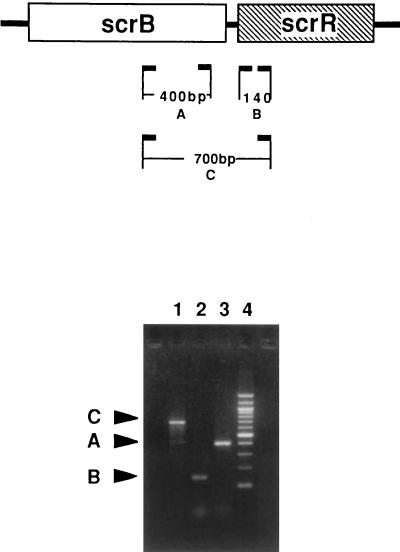

RT-PCR analysis of transcription.

In order to confirm the coexpression of the scrB and scrR genes, RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expressed by strain SP2 was carried out (Fig. 9). Primers B-RT1 and B-RT2a amplified a 400-bp fragment which is part of the scrB gene. Likewise, primers R-RT1 and scrR amplified a small 140-bp fragment which is internal to the scrR gene. In addition, primers R-RT1 and B-RT2a amplified a 700-bp DNA fragment which could be synthesized only if both genes were cotranscribed on a polycistronic message. Omission of the reverse transcriptase from each reaction mixture indicated that the amplified fragments were not produced from contaminating chromosomal DNA. Interestingly, the more intense band for fragment A compared to that for fragment C might be explained by the presence of a shorter mRNA species in addition to the full-length scrB-scrR transcript. However, additional experiments will be necessary to determine if the 1.35-kb mRNA (Fig. 7) is responsible for this difference.

FIG. 9.

RT-PCR amplification of the scrB-scrR genes. (Top) Diagrammatic representation of RT-PCR-amplified fragments. (Bottom) Agarose gel patterns of amplified fragments. Lanes: 1, C fragment (700 bp) amplified with primers B-RT2a and R-RT1; 2, B fragment (140 bp) produced with primers R-RT1 and scrR; 3, A fragment (400 bp) amplified with primers B-RT2a and B-RT1; 4, molecular size markers.

Gel mobility shift assays.

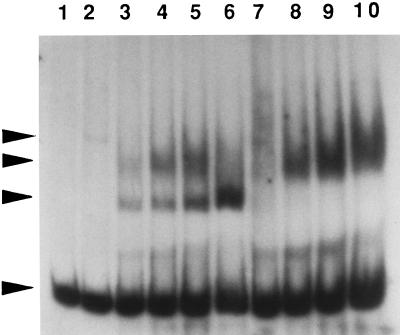

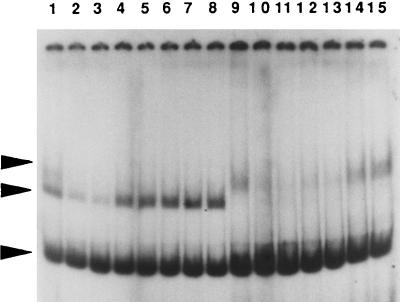

In order to confirm that the scrR gene codes for a regulatory protein which may bind to the scrB promoter region, gel shift assays were carried out. Crude cell extracts of SP2 as well as of the scrR mutant SP2ΔscrR were mixed with a DNA fragment containing the promoter regions of both the scrB and the scrA genes, and the mobilities of the fragments were determined (Fig. 10). The SP2 extract produced two prominent shifted bands. However, the extract from the scrR mutant demonstrated only the less mobile of the two bands. This suggested that the more rapidly migrating shifted band represented a complex of ScrR and the promoter fragment. The identity of the other protein which binds the DNA fragment is unknown, but it could represent RNA polymerase. The specificity of binding by the ScrR protein was indicated by the inability of nonspecific DNA fragments (a fragment from the S. mutans scrK [25] promoter region, the S. mutans dgk structural gene [35], or a fragment from the Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 chromosome) to interfere with the formation of the putative ScrR-DNA complex (Fig. 11). However, the band intensities of the less mobile shifted band were decreased in the presence of the two S. mutans DNA fragments but not the T. denticola fragment. This latter result would be compatible with an S. mutans RNA polymerase-scrB promoter fragment complex in the less mobile shifted band.

FIG. 10.

Gel mobility shift assays with cell extracts of S. mutans and the end-labeled 215-bp DNA fragment containing the scrA and scrB promoter regions. Lanes: 1, no protein added; 2, 0.5 μg of MBP-ScrR fusion protein; 3 to 6, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg, respectively, of SP2 extract; 7 to 10, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg, respectively, of extract from SP2ΔscrR. Arrowheads: top, MBP-ScrR-scrA scrB fragment complex; second from top, putative RNA polymerase-scrA scrB fragment complex; second from bottom, ScrR-scrA scrB fragment complex; bottom, labeled scrA scrB fragment.

FIG. 11.

Specificity of gel mobility shift assays with extracts of S. mutans. Lanes 1 to 8, crude extracts of SP2; lanes 9 to 15, crude extracts of SP2ΔscrR. Lanes: 1, no competitor; 2, 10-fold excess of unlabeled promoter fragment relative to labeled fragment; 3, 20-fold excess of promoter fragment; 4, 10-fold excess of S. mutans scrK DNA fragment; 5, 20-fold excess of scrK fragment; 6, 20-fold excess of fragment from T. denticola dBII; 7, 20-fold excess of T. denticola fragment; 8, 10-fold excess of S. mutans dgk gene fragment; 9, no competitor; 10, 10-fold excess of scrB-scrA promoter fragment; 11, 20-fold excess of scrB promoter fragment; 12, 10-fold excess of scrK fragment; 13, 20-fold excess of scrK fragment; 14, 10-fold excess of T. denticola fragment; 15, 20-fold excess of T. denticola fragment. Arrowheads: top, putative RNA polymerase-scrA scrB fragment complex; middle, ScrR-scrA scrB fragment complex; bottom, scrA scrB fragment.

Attempts were made to examine the interaction of purified ScrR protein with the scrA-scrB promoter region following expression of MBP (maltose binding protein)-ScrR and transcarboxylase-ScrR fusion proteins constructed as previously described for other S. mutans genes (26, 34). Although both fusion proteins were readily expressed in E. coli and bound to the scrB promoter fragment (Fig. 10), neither fusion protein could be demonstrated to bind to the promoter fragment in a specific manner (data not shown). This suggested that the fusion of ScrR to either MBP or transcarboxylase altered the ability of the regulatory protein to specifically bind to the scrB promoter fragment. In addition, cleavage of the ScrR protein from the fusion proteins did not result in the formation of a DNA-binding protein, probably due to the propensity of DNA-binding proteins to aggregate when highly expressed in E. coli (8).

DISCUSSION

Because of the pivotal role of dietary sucrose in the etiology of human dental caries, the effect of this sugar on dental plaque bacterial metabolism is of considerable interest. The results of earlier studies have demonstrated that most of the sucrose metabolized by cariogenic mutans streptococci is converted to lactic acid (32). Since significant amounts of sucrose are taken up by the cells by the sucrose PTS (28), the influence of the environment of the oral cavity on this system is clearly relevant to cariogenesis. Because of the utilization of less specific assays in earlier studies of sucrose metabolism by the mutans streptococci (9, 30, 31), it was not clear how sucrose influenced sucrose transport by the cells. Nevertheless, earlier studies with different strains of the mutans streptococci did suggest that higher cell-associated invertase activities were observed for cells grown in the presence of sucrose than for those grown with glucose or fructose (9, 31). More recent results with specific gene fusion technology (24) as well as the present results with the same approach have confirmed that growth in the presence of sucrose results in enhanced expression of two key enzymes in the major transport system of the sugar: EnzIIScr and Suc-6PH. For both enzymes, the relative strengths of expression in the presence of common sugars present in the human oral cavity were demonstrated to be sucrose>glucose>fructose. This confirms similar observations made earlier with permeabilized cells of Streptococcus sobrinus 6715 (30). Thus, as previously suggested (9, 30, 31), dietary sucrose appears to alter the expression of a major sucrose transport system in S. mutans. It should also be noted that the relative strengths of expression of the scrA and scrB genes by sucrose may be greater than actually demonstrated since the multiple extracellular glycosidases of the organism likely produce both glucose and fructose during growth in the presence of the disaccharide. Since fructose appears to repress the enhancing effects of sucrose, the sucrose effects may be underestimated in these experiments. It is also of interest that sucrose also appears to induce the expression of other sucrose-metabolizing enzymes in S. mutans, such as fructosyltransferase and the Gtfs (33).

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated that plaque bacteria are subjected to fluctuations in pH (14). Therefore, the present demonstration (Fig. 3) that acidity appears to modulate the expression of both scrA and scrB suggests that such a mechanism could play a role as a feedback repression system. Enhanced fermentation of sugars leading to lactic acid formation would decrease the environmental pH, leading to repression of two key enzymes involved in sucrose transport and metabolism. However, the present results do not indicate whether such effects are directly dependent upon pH or upon altered growth rates since acidic pHs decrease the growth rate of S. mutans.

It is of interest that, among the microorganisms able to transport and metabolize sucrose, a variety of scr gene organizations and regulatory mechanisms are apparent (29). However, only in the mutans streptococci (5, 23) are the scrA and scrB gene homologs transcribed from opposite DNA strands. For most bacteria, both genes are transcribed either within the same operon or independently from the same DNA strand. In addition, a variety of different regulatory gene arrangements have been demonstrated. For B. subtilis, the regulatory sacT gene involved in antitermination is found upstream of the scrA and scrB homologs (7). For the enterobacterial plasmid pUR2100 sucrose-metabolizing system, the regulatory scrR gene is located immediately downstream from the scrB gene but is expressed from its own promoter (12). Likewise, the scrR gene of Vibrio alginolyticus is transcribed from its own promoter divergently from the scrA-scrK-scrB operon (3). Therefore, the S. mutans system appears to be unique in that the scrR gene appears to be present in the same operon as one of its target genes, scrB.

The present results together with recent studies (24) indicate that both the S. mutans scrA and scrB genes are similarly regulated by different sugars. In most other bacteria, such regulation results from the presence of both genes within the same operon (29). However, the mutans streptococci also appear to be unique in that both genes are present in divergently transcribed operons (5, 23). In the case of S. sobrinus, this may result from the partial overlapping of the scrA and scrB promoters (5). Primer extension analysis of the two genes from S. mutans GS-5 (Fig. 8) (10a) indicates that the two promoters do not overlap. A comparable scrR gene has not yet been identified for S. sobrinus.

The present results suggest that sucrose (or one of its metabolites) is involved in increased expression of the scrB and scrA genes. A similar observation has been made for the scr genes of S. xylosus (8). However, for the K. pneumoniae and enteric pUR4000 systems (12), fructose and fructose-1-phosphate appear to induce scr gene expression. By contrast, fructose appears to repress scr gene expression in S. mutans. Likewise, scr operator sequences were identified upstream of the K. pneumoniae scrB gene (12), but comparable sequences could not be detected upstream of either the S. mutans scrA or scrB gene. A direct repeating sequence was detected upstream of the scrB gene, including part of the putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence (22), but its role in the regulation of scrB expression remains to be determined.

Based upon the properties of other scrR genes (29), together with the results of inactivating the strain GS-5 scrR gene, it is likely that the scrR gene acts as a repressor of the scrB operon. Likewise, the present results suggest that ScrB binds in the intergenic region between the scrA and scrB genes. According to such a model, sucrose (or one of its metabolites) inactivates the repressor better than do glucose derivatives. However, fructose metabolites apparently are not effective in inactivating the putative ScrR repressor. Since scrR mutants are still repressible with fructose, another regulatory protein together with fructose derivatives may also repress scrB expression. Alternatively, both fructose and, to a lesser extent, glucose may act as corepressors in conjunction with ScrR. Therefore, a complex system of regulation may be involved in modulating the expression of a major sucrose transport system in S. mutans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This investigation was supported in part by grant DE03258 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki H, Shiroza T, Hayakawa M, Sato S, Kuramitsu H K. Cloning of a Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferase gene coding for insoluble glucan synthesis. Infect Immun. 1986;53:587–594. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.587-594.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beverly S M. Enzyme amplification of RNA by PCR. In: Ausubel F M, et al., editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. pp. 15.4.1–15.4.6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blatch G L, Scholle R R, Woods D R. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of the Vibrio alginolyticus sucrose uptake-encoding genes. Gene. 1990;95:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90408-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussey L B, Switzer R L. The degA gene product accelerates degradation of Bacillus subtilis phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6348–6353. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6348-6353.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y-Y M, LeBlanc D J. Genetic analysis of scrA and scrB from Streptococcus sobrinus 6715. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3739–3746. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3739-3746.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chodosh L A. Mobility shift DNA-binding assay using gel electrophoresis. In: Ausubel F M, et al., editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. pp. 12.2.1–12.2.10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debarbouille M, Arnaud M, Fouet A, Klier A, Rapoport G. The sacI gene regulating the sacPA operon in Bacillus subtilis shares strong homology with transcriptional antiterminators. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3966–3973. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3966-3973.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Ellwood D C, Hamilton I R. Properties of Streptococcus mutans Ingbritt growing on limiting sucrose in a chemostat: repression of phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase transport system. Infect Immun. 1982;36:576–581. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.2.576-581.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gering M, Bruckner R. Transcriptional regulation of the sucrase gene of Staphylococcus xylosus by the repressor ScrR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:462–469. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.462-469.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons R J. Presence of an invertase-like enzyme and a sucrose permeation system in strains of Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res. 1972;6:122–131. doi: 10.1159/000259784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayakawa M, Aoki H, Kuramitsu H K. Isolation and characterization of the sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase gene from Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1986;53:582–586. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.582-586.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Hiratsuka, K., and H. Kuramitsu. Unpublished results.

- 11.Inoue T, Cech T R. Secondary structure of the circular form of Tetrahymena rRNA intervening sequence: a technique for RNA structure analysis using chemical probes and reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:648–652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jahreis K, Lengeler J W. Molecular analysis of two ScrR repressors and of a ScrR-FruR hybrid repressor for sucrose and D-fructose specific regulons from enteric bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:195–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuramitsu H K. Virulence factors of mutans streptococci: role of molecular genetics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:159–176. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loesche W J. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental caries. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:353–380. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lunsford R D, Macrina F L. Molecular cloning and characterization of scrB, the structural gene for the Streptococcus mutans phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sucrose phosphotransferase system sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:426–434. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.426-434.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen C C, Saier M H., Jr Phylogenetic, structural and functional analyses of the LacI-GalR family of bacterial transcription factors. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:98–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry D, Wondrack L M, Kuramitsu H K. Genetic transformation of putative cariogenic properties in Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1983;41:722–727. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.722-727.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poy F, Jacobson G R. Evidence that a low-affinity sucrose phosphotransferase activity in Streptococcus mutans GS-5 is a high-affinity trehalose uptake system. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1479–1480. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1479-1480.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell R R B, Aduse-Opoku J, Sutcliffe I C, Tao L, Ferretti J J. A binding protein-dependent transport system in Streptococcus mutans responsible for multiple sugar metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4631–4637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Sato, Y. Unpublished results.

- 22.Sato Y, Kuramitsu H K. Sequence analysis of the Streptococcus mutans scrB gene. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1956–1960. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1956-1960.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato Y, Poy F, Jacobson G R, Kuramitsu H K. Characterization and sequence analysis of the scrA gene encoding enzyme IIScr of the Streptococcus mutans phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sucrose phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:263–271. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.263-271.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato Y, Yamamoto Y, Suzuki R, Kizaki H, Kuramitsu H K. Construction of scrA::lacZ fusions to investigate regulation of the sucrose PTS of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;79:339–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato Y, Yamamoto Y, Kizaki H, Kuramitsu H K. Isolation, characterization and sequence analysis of the scrK gene encoding fructokinase of Streptococcus mutans. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:921–927. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-5-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibata Y, Kuramitsu H K. Identification of the Streptococcus mutans frp gene as a potential regulator of fructosyltransferase expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;140:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiroza T, Kuramitsu H K. Construction of a model secretion system for oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3745–3755. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3745-3755.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Shiroza, T., and H. K. Kuramitsu. Unpublished results.

- 28.Slee A M, Tanzer J M. Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sucrose phosphotransferase activity in five serotypes of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1979;26:783–786. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.783-786.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinmetz M. Carbohydrate catabolism: pathways, enzymes, genetic regulation, and evolution. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 30.St. Martin E J, Wittenberger C L. Regulation and function of sucrose 6-phosphate hydrolase in Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1979;26:487–491. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.487-491.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanzer J M, Brown A T, McInerney M F. Identification, preliminary characterization, and evidence for regulation of invertase in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1973;116:192–202. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.1.192-202.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanzer J M, Chassy B M, Krichevsky M I. Sucrose metabolism by Streptococcus mutans SL-1. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1972;261:379–387. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(72)90062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wexler D L, Hudson M C, Burne R A. Streptococcus mutans fructosyltransferase (ftf) and glucosyltransferase (gtfBC) operon fusion strains in continuous culture. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1259–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1259-1267.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J, Cho M-I, Kuramitsu H K. Expression, purification, and characterization of a novel G protein, SGP, from Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2516–2521. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2516-2521.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamashita Y, Takehara T, Kuramitsu H K. Molecular characterization of a Streptococcus mutans mutant altered in environmental stress responses. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6220–6228. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6220-6228.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]