Abstract

A live oral recombinant Salmonella vaccine strain expressing pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) was developed. The strain was attenuated with Δcya Δcrp mutations. Stable expression of PspA was achieved by the use of the balanced-lethal vector-host system, which employs an asd deletion in the host chromosome to impose an obligate requirement for diaminopimelic acid. The chromosomal Δasd mutation was complemented by a plasmid vector possessing the asd+ gene. A portion of the pspA gene from Streptococcus pneumoniae Rx1 was cloned onto a multicopy Asd+ vector. After oral immunization, the recombinant Salmonella-PspA vaccine strain colonized the Peyer’s patches, spleens, and livers of BALB/cByJ and CBA/N mice and stimulated humoral and mucosal antibody responses. Oral immunization of outbred New Zealand White rabbits with the recombinant Salmonella strain induced significant anti-PspA immunoglobulin G titers in serum and vaginal secretions. Polyclonal sera from orally immunized mice detected PspA on the S. pneumoniae cell surface as revealed by immunofluorescence. Oral immunization of BALB/cJ mice with the PspA-producing Salmonella strain elicited antibody to PspA and resistance to challenge by the mouse-virulent human clinical isolate S. pneumoniae WU2. Immune sera from orally immunized mice conferred passive protection against otherwise lethal intraperitoneal or intravascular challenge with strain WU2.

Orally administered live avirulent Salmonella vaccine strains colonize the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (Peyer’s patches) and reach deep tissues, including the liver and spleen, via the circulatory system (8, 10, 30, 33). Avirulent Δcya Δcrp Δasd Salmonella strains expressing foreign antigens from bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens have been constructed as live recombinant Salmonella-based antigen delivery systems for oral vaccinations (11, 27). The recombinant avirulent Salmonella strains, while eliciting anti-Salmonella immune responses, can also induce antigen-specific humoral, mucosal, and cellular immune responses to recombinant proteins expressed by the immunizing organism. This avirulent Salmonella technology offers prospects for developing multivalent vaccines (8, 11, 13, 14, 30, 33) that can be used to eventually develop safe, easy-to-use, and cost-effective oral vaccines for mass immunization against a wide variety of disease-causing pathogens.

Streptococcus pneumoniae causes life-threatening diseases, including pneumonia and meningitis. It is also associated with otitis media (ear infections) in young children and acute respiratory infections in humans of all age groups (1, 31). Ninety distinct capsular serotypes of S. pneumoniae have been associated with human infections (16). People with human immunodeficiency virus infection or AIDS have been shown to have invasive pneumococcal infections more frequently than the population at large (17). Pneumococcal diseases kill more people than any other infectious disease, claiming around 10 million lives yearly worldwide (29), including at least 1 million children with respiratory infections in developing countries. Pneumonia is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. The estimated annual cost of pneumococcal morbidity and mortality in the United States is $23 billion (21). The emergence of penicillin resistance and multi-drug-resistant strains threatens the clinical management of pneumococcal disease (28, 36). The reservoir of pneumococci infecting humans is maintained largely by nasopharyngeal carriage, which is usually asymptomatic.

The present 23-valent capsular polysaccharide vaccine is only 60% effective against pneumococcal pneumonia in the elderly (35) and is not immunogenic enough in children under 2 years of age to warrant its use in that high-risk population (18). Chemical conjugates of capsular polysaccharides and proteins are being developed as immunogenic forms of the polysaccharides for immunization of children. Another approach that is being investigated is immunization with pneumococcal proteins that have been shown to elicit protective immunity in mice (6, 29). These proteins should be highly immunogenic in children and in the elderly, and they could be produced inexpensively enough for application in the developing world, where cost is a major factor in vaccine production and use. Protein antigens have the added advantage that they can be easily delivered through oral immunization with a live vaccine vector such as an avirulent Salmonella strain.

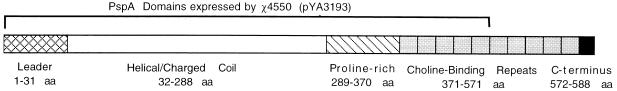

Pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) is expressed on all pneumococci (5, 9) and has been shown to elicit protection against pneumococcal sepsis (25, 40) and carriage (42) in mice. The mature PspA from S. pneumoniae Rx1 has a molecular mass of 65 kDa and contains four distinct domains: an NH2-terminal charged α-helical coiled-coil domain, a proline-rich domain, 10 tandem-repeat regions, and a 17-amino-acid carboxy terminus (44). The repeat region of PspA forms a choline binding site which mediates the attachment of PspA to the cell surface lipoteichoic acids of pneumococci (46). The α-helical domain comprises almost half of the protein and contains the protection-eliciting epitopes. PspA has been shown to exhibit serologic and molecular weight variability (9). However, in spite of this variability, many of the protection-eliciting epitopes of different PspAs are cross-reactive, and immunization with a single PspA can elicit protection against strains expressing different capsular polysaccharide types and serologically divergent PspAs (25, 40). As a result, any future PspA vaccine would probably require only a few different PspAs to elicit optimal protection (6).

In this report, we describe the construction and evaluation of a recombinant oral live Salmonella typhimurium vaccine strain which stably expresses a fragment of Streptococcus pneumoniae Rx1 PspA that includes its leader, α-helical region, proline-rich region, and the first five repeats of the choline binding region. The DNA encoding this fragment was cloned into a high-copy-number Asd+ vector (pUC replicon based) in the avirulent Δcya Δcrp Δasd S. typhimurium χ4550. The immunogenicity and protective properties of the vaccine were evaluated in animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Table 1 lists the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work. S. typhimurium vaccine strains (Δcya Δcrp Δasd mutants) were grown in Luria broth (L broth) or on Luria agar (L agar) containing diaminopimelic acid (DAP; 50 μg/ml) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (20). S. typhimurium χ4550 (37) harboring the Asd+ vector pYA3148 or the recombinant plasmid pYA3193 was grown in L broth or on L agar with no DAP supplementation. All Salmonella strains were grown with aeration from a nonaerated static overnight culture. Buffered saline containing 1% gelatin was routinely used as a diluent. S. typhimurium vaccine clones were stored frozen at −70°C in 1% peptone containing 5% glycerol (12, 27). Escherichia coli DH1(pJY4347) (45) was grown in L broth containing erythromycin (200 μg/ml) and stored frozen at −70°C in L broth containing 10% glycerol. For challenge studies, virulent S. pneumoniae type 3 strain WU2 (4), stored at −70°C in Todd-Hewitt broth containing 20% glycerol, was grown at 37°C under anaerobic conditions in the BBL Gas Pack Plus anaerobic system (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) in Todd-Hewitt broth plus 0.5% yeast extract (4).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype, phenotype, and/or characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. typhimurium χ4550 | SR-11 pStSR101+gyrA1816 Δcrp-1 ΔasdA1 Δ(zhf-4::Tn10) Δcya-1 | 34 |

| E. coli | ||

| χ6212 | Asd− DH5α derivative | 27 |

| DH1 | Host strain for pJY4347 | 38, 45 |

| S. pneumoniae WU2 | Encapsulated type 3; virulent | 4 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJY 4347 | Harbors 2.0-kb HindIII-KpnI fragment encoding the entire PspA+ (65 kDa)a cloned into HindIII-KpnI sites of pJY4313 | 44, 45 |

| pYA 3148 | Asd+ vector, high copy number (PUC-based Kmr) | 33 |

| pYA 3193 | Recombinant Asd+ vector harboring the C-terminally truncated pspA gene (1.5 kb); specifies 55-kDa PspA protein | This study |

| pYA 232 | Low-copy-number (pSC101 ori) plasmid containing lacIq repressor gene; Tcr | 27 |

The apparent molecular mass of a PspA monomer on SDS gels is 85 kDa.

PCR.

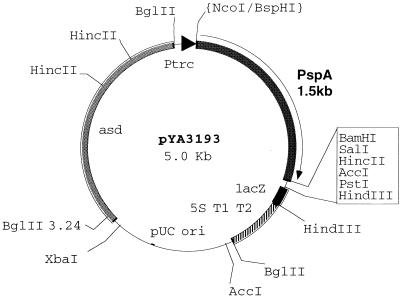

A fragment of the pspA gene was PCR amplified from plasmid DNA from E. coli DH1(pJY4347). The amplified fragment included the 5′ region of the pspA gene from the ATG (nucleotides 127 to 129) start codon through the signal peptide leader sequence up to the end of the fifth tandem repeat in the choline binding region (Fig. 1 and 2). This fragment includes 1,503 bp and encodes the first 470 amino acids of S. pneumoniae Rx1 PspA. The PCR primer sequences were as follows: NH2 primer (33 bp), 5′ CAT GTC ATG AAT AAG AAA AAA ATG ATT TTA ACA 3′; and COOH primer (28 bp), 5′ C GGG ATC CTA TGC CAT AGC GCC GTT AGC 3′ (The Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, Tex.). The TC ATG A BspHI site was created on the NH2 primer for ligation into the NcoI site of the Asd+ vector pYA3148. The C-terminal PCR primer has the BamHI site for ligation into the BamHI site of the Asd+ vector pYA3148. Vent polymerase and Vent buffer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) were used in the PCR mixture. The PCR was carried out with 30 cycles of 95°C (1 min), 56°C (1 min), and 72°C (2 min) with the 480 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Calif.). The amplified PCR product of the 1.5-kb pspA gene was evaluated in a 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE)–agarose gel and purified by using a Gene Clean kit (BIO 101 Inc., La Jolla, Calif.).

FIG. 1.

PspA domains expressed by recombinant S. typhimurium. The diagram shows the domains of PspA from S. pneumoniae Rx1 and the portions expressed in S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193) and E. coli χ6212(pYA3193). aa, amino acids.

FIG. 2.

Structure of the recombinant plasmid vector. High-copy-number pUC replicon-based Asd+ plasmid expression-cloning vector pYA3148 (3.5 kb) that harbors the truncated S. pneumoniae pspA gene (1.5 kb) was electroporated into S. typhimurium χ4550 and E. coli χ6212. Restriction enzyme sites are indicated. asd, aspartate β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase.

Construction, cloning, and expression of the pspA gene in E. coli and S. typhimurium.

The Asd+ vector pYA3148 was digested with NcoI and BamHI restriction enzymes (Promega buffer C, 5 h, 37°C), while the pspA PCR product was digested first with BspHI (NEBuffer 4, 2 h 30 min, 37°C) and then separately with BamHI (Promega buffer C, 2 h, 37°C). The ligation reaction was done overnight at 16°C in the presence of T4 DNA ligase (International Biotechnologies, Rochester, N.Y.). The 5.0-kb size of the ligated product (Fig. 2) was checked by electrophoresis in a 1% TAE–agarose gel. The identity of the recombinant plasmid was confirmed by restriction digestion analysis with SacI and BamHI. The recombinant plasmid was then electroporated into E. coli χ6212(pYA232) and the S. typhimurium χ4550 (Δasd Δcya Δcrp) vaccine strain. Initial selection of the recombinant clones was on L agar plates without DAP since only clones harboring the recombinant plasmid would grow on that medium. The expression of the PspA antigen was checked by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis with the anti-PspA monoclonal antibody (MAb) Xi126 (23). S. typhimurium χ4550 (pYA3193) (Table 1) was further characterized for the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), growth on minimal medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose, the presence of the 90.0-kb virulence plasmid, and growth in L broth with and without DAP.

To check the expression of recombinant PspA by S. typhimurium and E. coli, cells from 4-h aerated cultures were harvested, placed in 2× SDS sample buffer, and boiled at 95°C for 5 min. The proteins separated by (32), 12% SDS–PAGE (Miniprotean II system; Bio-Rad) were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or immunoblotted with the anti-PspA mouse MAb Xi126 (24). To make sure the vaccine strain did not lose the ability to express PspA during in vivo colonization, colony dot blots of bacteria retrieved from mouse tissues were developed like Western blots and visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate(BCIP)–nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) in accordance with published procedures (32). The periplasmic localization of recombinant PspA synthesized by S. typhimurium was determined by the cold osmotic shock-based cell fractionation method (7, 15). The presence of PspA in the culture supernatant was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (45).

Immunization of mice and rabbits.

For oral-vaccination studies, groups of 15 BALB/cJ H-2d and CBA/N xid J H-2k inbred 8-week-old female mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were deprived of food and water for 4.5 h and then given 30 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium bicarbonate (pipetted inside the mouth with a micropipettor) to neutralize stomach acidity. Approximately 30 min later, the recombinant S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193)-PspA vaccine (1.5 × 109 CFU in 30 μl of buffered saline containing 1% gelatin) was orally administered at the back of the mouth. Food and water were returned to the animals 30 to 45 min later. Two months later, a second oral dose was given according to the above procedures. Control groups of mice were orally immunized with S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3148) (host-vector controls) or given nothing (naive unimmunized controls). Blood (retroorbital puncture) and vaginal-secretion specimens (collected in a 50 μl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] wash) were obtained at weekly or biweekly intervals and stored at −70°C. Intestinal washes were conducted by washing the contents of the mouse large intestine into 1.0 ml of PBS and pelleting the debris by centrifugation. Supernatants were stored frozen. The responses of the common mucosal immune system were monitored by examining the vaginal washings since this method provides a means of obtaining serial secretions from each animal.

Two 8-week-old female outbred New Zealand White rabbits (Doe Valley Farm, Bentonville, Ark.) were kept separately in isolator cages and deprived of food and water for 4 h prior to oral vaccination with strain χ4550(pYA3193). Thirty minutes before immunization, the rabbits were allowed to drink 6 ml of a 10% sodium bicarbonate solution. The rabbits were immunized orally with 1.6 × 1010 CFU of strain χ4550(pYA3193). A second oral immunization was given 1 month later. Sera and vaginal secretions were then collected at biweekly intervals and were stored at −70°C prior to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Vaginal secretions from rabbits were collected in a wash of 0.5 ml of PBS.

Colonization of mice with the recombinant Salmonella strain.

After being given a single oral dose of S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193) or χ4550(pYA3148) (1.5 × 109 CFU/mouse for both of the strains used), three mice were euthanized each on days 7 and 14 post-oral immunization. Their Peyer’s patches, spleens, and livers were collected aseptically. The tissues were homogenized and plated on MacConkey agar plates with 1% maltose to examine colonization and persistence of the recombinant vaccine.

Immunoassays. (i) Antibodies.

Anti-PspA antibodies of the immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA classes in sera and vaginal secretions of BALB/c and CBA/N xid mice and anti-PspA IgG levels in rabbit sera and vaginal washings were determined by ELISA. Anti-S. typhimurium whole-cell lysate antigens and anti-S. typhimurium LPS-specific antibodies were also titrated to monitor the responses to the Salmonella strains. Purified, native, full-length PspA isolated from S. pneumoniae R36A (2) was coated onto Immulon 4 plates (Dynatech) at a concentration of 1.0 μg/well. The cloned PspA expressed by S. typhimurium in this study was derived from the pspA gene of strain Rx1, which was derived from strain R36A. Strains Rx1 and R36A are believed to express identical PspAs from identical pspA genes (4, 9, 26, 41). S. typhimurium whole-cell lysate or methylated S. typhimurium LPS (1.0 μg/well; Sigma) was coated onto Immulon 3 plates. Antigens were suspended in sodium carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer, pH 9.6 (100 μl/well), and the coated plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 to 6 h followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C. Free binding sites were blocked with a blocking buffer (PBS [pH 7.4]–0.1% bovine serum albumin). Samples were serially diluted in the blocking buffer (dilutions were done in duplicate [100 μl/well]) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were treated with goat anti-mouse IgG–biotin, goat anti-mouse IgM–biotin, goat anti-mouse IgA–biotin, or goat anti-rabbit IgG, followed by development with excess avidin-peroxidase and orthophenylenediamine. All immunoreagents were purchased from Sigma. Plates were read in an automated microtiter plate ELISA reader at 450 nm (model EL311SX; Biotek, Winooski, Vt.). The titer of each serum specimen was denoted as the log10 of the reciprocal dilution of serum giving five times the absorbance of the undiluted preimmune serum.

(ii) ELISPOT.

BALB/cJ mice were orally immunized once, as described earlier, with either strain χ4550(pYA3193) or strain χ4550(pYA3148). The numbers of antibody-secreting B cells producing anti-PspA-specific IgG, IgA, and/or IgM per 106 cells of the spleen, Peyer’s patches, and peripheral blood were counted. Three mice were euthanized each on days 2, 4, and 7. For these determinations, tissue samples from all three mice euthanized on the same day were pooled. The assays were done as described previously (43). Millicell-HA plates (Millipore, Mass.) coated with PspA at 2 μg/well were used in the assay. Bound anti-PspA antibodies were revealed as immunodots with Sigma Fast BCIP-NBT chromogen (Sigma).

Surface immunofluorescence.

Surface immunofluorescence assays of WU2 pneumococci and S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193) were done with sera from orally vaccinated mice. Pooled sera from mice orally immunized with the recombinant Salmonella strain, sera from mice immunized with the host Salmonella strain, and preimmune sera were used in the study. Control sera used in these studies were normal mouse sera and sera from mice immunized with the Salmonella vector (lacking PspA) only. Faint background fluorescence was observed with the control sera, but it was easily distinguished from the bright fluorescence detected with sera from mice immunized with strain χ4550(pYA3193). For these studies, pneumococci were harvested, incubated with pooled immune or nonimmune sera for 2 h at 37°C, washed twice in cold PBS, and stained with goat anti-mouse IgG–fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma) at a 1:50 dilution for 2 h at 4°C. Surface fluorescence of pneumococcal cells was observed microscopically. S. pneumoniae WU2 stained with anti-PspA MAb Xi126 was the positive control.

Protection studies.

BALB/cJ inbred mice were orally immunized twice with recombinant S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193). Anti-PspA antibody titers were measured by ELISA prior to challenge. During the fourth week after administration of the second oral dose, mice were challenged by the intraperitoneal (i.p.) or intravenous (i.v.) route with different doses of virulent pneumococci (WU2 type 3 strain). Mice orally immunized with S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3148) and unimmunized naive mice were used as control groups. Infected mice were observed for deaths for 15 to 21 days. Virtually all deaths occurred within the first week postchallenge. Passive protection was carried out by i.p. injection of various dilutions of immune serum 1 h prior to i.v. or i.p. challenge with different doses of S. pneumoniae WU2 in 0.1 ml of Ringer solution.

RESULTS

Expression and localization of the recombinant truncated PspA in S. typhimurium.

The Δcya Δcrp Δasd mutant S. typhimurium vaccine strain (χ4550) transformed with recombinant plasmid pYA3193 stably expressed PspA as detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels and by development of Western immunoblots with anti-PspA MAb Xi126. The level of PspA expression observed in the recombinant E. coli χ6212 DH5α-derived construct was higher in cells grown in the presence of isopropyl-β-dthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) than in its absence, as expected due to the presence of pYA232 encoding the LacIq repressor in χ6212. Based on Coomassie blue staining, the level of expression of PspA was from 5 to 6% of the total protein in both the S. typhimurium and E. coli strains. These results were consistent with those of earlier studies of the expression of PspA in E. coli (45). Although the expected size of the cloned truncated PspA was 55 kDa, the recombinant product migrated as a series of bands ranging from 30 to about 75 kDa. This microheterogeneity was observed for recombinant PspA expressed in both S. typhimurium and E. coli, was consistent with previous studies demonstrating heterogeneity in the size of a single full-length native PspA produced by pneumococci and E. coli (25, 39, 45), and was shown previously to be due to both polymerization and degradation of PspA (39). The periplasmic fraction and the supernatant contained virtually all of the expressed PspA. The majority of the recombinant PspA was exported to the periplasmic space of S. typhimurium, with little remaining in the cytoplasm, as had previously been reported for PspA cloned in E. coli (4, 45).

Persistence, tissue distribution, and recovery of the live vaccine after oral immunization of mice.

After a single oral dose of strain χ4550(pYA3193) or the vector-only control strain χ4550(pYA3148), the bacteria reached the Peyer’s patches, spleens, and livers of mice of both strains. The numbers of CFU recovered from these tissues at 14 days were as high or higher than what was observed at 7 days (Table 2). In BALB/c mice, the PspA-producing strain showed less colonization of the spleen and liver than did the nonvaccine host strain (vector control). This difference in colonization by the host and vaccine strain was not observed in CBA/N mice. Most importantly, the vaccine strain showed very similar levels of PspA in all tissues regardless of whether the Salmonella-susceptible BALB/cJ mice or the more Salmonella-resistant CBA mice were used. The vaccine bacteria recovered on days 7 and 14 still produced PspA as detected by colony immunoblotting (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Recovery of host and PspA-expressing S. typhimurium from BALB/c and CBA/N mice after a single oral inoculation with 1.5 × 109 CFU of each strain

| Mouse strain | Tissue | Log10 CFU recovered of strain on day:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Salmonella host χ4550 (pYA3148)a

|

PspA-expressing S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193)b

|

||||||||

| 7 | 14 | 7

|

14

|

||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| BALB/c | Peyer’s patch | 3.0 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.2 |

| Liver | 3.9 | 3.1 | <1.0 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 3.1 | |

| Spleen | 3.8 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | |

| CBA/N | Peyer’s patch | 3.0 | 3.7 | <1.0 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| Liver | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 4.1 | |

| Spleen | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | |

Data are averages of values for three mice.

Data are individual values for each mouse (numbered 1 to 6).

Anti-PspA immune responses in mice and rabbits to oral vaccination with the recombinant S. typhimuriumχ4550(pYA 3193)-PspA vaccine.

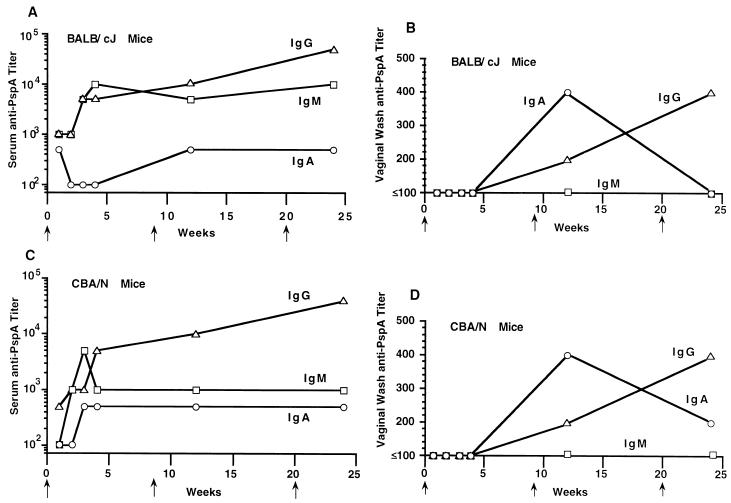

The kinetics of the anti-PspA of IgG, IgM, and IgA classes of antibody in sera and vaginal secretions of mice were measured. The vaccine induced humoral IgG, IgM, and IgA anti-PspA antibody responses in the BALB/c and CBA/N xid mouse strains (Fig. 3A and C). Within a week after administration of a single oral dose, the reciprocal serum IgG anti-PspA titers had reached ≥1,000 and the titers of IgA and IgM had reached ≥100. A single oral immunization of mice with the vaccine stimulated the production, in vaginal secretions, of reciprocal IgG, IgM, and IgA anti-PspA titers of 400, 100, and 500, respectively (Fig. 3B and D). Anti-PspA immunoglobulins titers (IgG, 100; IgA, 500; and IgM, 100) were also observed in mouse intestinal washings.

FIG. 3.

Class-specific anti-PspA IgG (▵), IgM (□), and IgA (○) antibody titers in sera and secretions of mice orally immunized with 1.5 × 109 CFU of S. typhimurium vaccine strain χ4550(pYA3193) at weeks 0, 8, and 20 (as indicated by arrows on the horizontal axis). The titers represent the maximum end-point dilutions from the pooled sera yielding an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) five times that of undiluted preimmune serum from the vector-immunized group (OD450, ≤0.1). The anti-PspA titer was <1 for NMS (preimmune mice). All mice were challenged 22 weeks postimmunization with live S. pneumoniae WU2 (see Table 5). (A) Class-specific anti-PspA antibody titers in the pooled sera of 10 BALB/c mice. (B) Anti-PspA antibody titers in pooled vaginal secretions of 10 BALB/c mice. (C) Anti-PspA antibody titers in pooled sera of 10 CBA/N xid mice. (D) Anti-PspA antibody titers in pooled vaginal secretions of 10 CBA/N xid mice.

At weeks 8 and 20, oral booster immunizations were given to the mice. The serum IgA anti-PspA titers in mice were no higher following the last boost than after the primary immunization (reciprocal titer range, 100 to 1,000). Although IgM anti-PspA titers were generally higher than those of IgA antibodies, they also showed no net increase following the second and third oral immunizations (reciprocal titers of 50,000 and 140,000 were observed in BALB/c and CBA/N mice, respectively). The serum IgG titers, however, increased at least slightly following each immunization or boost (Fig. 3A and C).

In vaginal secretions, levels of IgA antibody to PspA peaked after the first boost, but this antibody was present in most mice at low levels following the primary infection (Fig. 3B and D). In both strains, the level of IgG in the vaginal secretions continued to increase over the 24-week period of the study. IgM antibody, on the other hand, was virtually undetectable in the vaginal secretions. Both BALB/c and CBA/N mice gave strong antibody responses to LPS and anti-S. typhimurium lysates, although the level of response in the BALB/c mice was slightly higher (Table 3). Using the ELISPOT assay, PspA-specific IgG, IgM, and IgA antibody-secreting cells were detected in the spleens, Peyer’s patches, and peripheral blood of orally immunized mice at days 2, 4, and 7 (data not shown). All three anti-PspA ELISPOT responses peaked on day 4. Peak PspA-specific IgG and IgM ELISPOTS were about 2,000/106 lymphocytes (about 1,000-fold over background). The maximum IgA ELISPOT response was about 500/106 lymphocytes for the spleen and two to three times that number for peripheral blood and Peyer’s patches. The orally immunized mice were healthy throughout the immunization study period.

TABLE 3.

Reciprocal titers of antibody to LPS and S. typhimurium lysate in sera and vaginal secretions of BALB/c mice orally immunized with PspA-expressing S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193)a

| Sample | Reciprocal titer of antibody reactive with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Salmonella LPS

|

Salmonella lysate

|

|||||

| IgG | IgM | IgA | IgG | IgM | IgA | |

| Serum | 5 × 104 | 103 | 5 × 102 | 105 | 4 × 104 | 5 × 102 |

| Vaginal secretions | 102 | 5 × 102 | 102 | 103 | 5 × 102 | 2 × 102 |

Serum and vaginal secretions from 10 BALB/c mice were pooled separately 4 weeks after the second oral immunization. Anti-LPS and anti-Salmonella titers were not detected (<101) in preimmune serum or vaginal secretions.

After a single oral dose of strain χ4550(pYA3193), both rabbits developed reciprocal serum anti-PspA titers of about 1,000. Anti-PspA IgG titers of about 100 were detected in rabbit vaginal secretions. The rabbits were boosted with a second oral immunization at 1 month. Two weeks later, their reciprocal serum IgG titers were 8,000, and their IgG anti-PspA titers in vaginal secretions were as high as 500. The orally immunized rabbits also had serum anti-LPS IgG titers as high as 40,000 and IgG anti-LPS titers of up to 100 in vaginal secretions. The orally immunized rabbits were healthy throughout the immunization period. For comparison, a recombinant PspA-enriched fraction (periplasmically expressed in S. typhimurium) formulated with Titremax adjuvant was injected into a single outbred rabbit at multiple intermuscular and subcutaneous sites. The rabbit was similarly boosted 1 month later. The rabbit produced a serum IgG anti-PspA reciprocal titer of 10,000 (data not shown).

Surface fluorescence of S. pneumoniae WU2.

Polyclonal immune sera (pooled from 10 mice) collected after oral immunizations with S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193) reacted with the native PspA expressed on the surface of the virulent WU2 human isolate of S. pneumoniae as revealed by an immunofluorescence assay test, demonstrating that sera from vaccinated mice could recognize native PspA (data not shown).

Evaluation of protective immunity.

BALB/cJ mice were vaccinated with either the recombinant Salmonella strain χ4550(pYA3193) or the host strain χ4550(pYA3148), lacking PspA expression, or were left unimmunized. After two oral immunizations, the mice were challenged i.p. with 3 × 103 CFU of S. pneumoniae WU2 (Table 4). In unimmunized BALB/cJ mice, the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of S. pneumoniae WU2 was <102 CFU by this route. When mice immunized with the PspA-expressing vaccine strain were challenged, 66% survived, compared to 30% of the mice immunized with the non-PspA-expressing host strain. This challenge dose killed 100% of unimmunized control mice, indicating that the host strain by itself had elicited some level of nonspecific host immunity. The time to death/survival ratio of mice immunized with the PspA− vector was significantly (P = 0.009) greater than that of nonimmunized mice and significantly (P = 0.004) less than that of mice immunized with the PspA+ Salmonella strain.

TABLE 4.

Oral immunization with PspA-expressing Salmonella strains protects BALB/cJ mice against i.p. challenge with 3 × 103 CFU of capsular type 3 S. pneumoniae

| Vaccine straina | PspA expressionb | No. of mice | % Alive on post- challenge dayc

|

Median day of deathd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 15 | ||||

| χ4550(pYA3193) | + | 35 | 97 | 66 | >15.0** |

| χ4550(pYA3148) | − | 10 | 100 | 30 | 4.0 |

| None (not immunized) | NA | 10 | 80 | 0 | 3.0* |

Mice were orally immunized two times at 1-month intervals with the indicated vaccine strains.

+, PspA expressed; −, PspA not expressed; NA, not applicable.

Four weeks after the second oral immunization, mice were challenged in two experiments with approximately 3 × 103 CFU of S. pneumoniae WU2. Both experiments gave similar results, and the data from each have been pooled for presentation and analysis. The LD50 of WU2 in nonimmunized BALB/c mice was <102 (data not shown).

* and **, respectively, indicate P values of 0.009 and 0.004 versus the time to death of mice immunized with the PspA− vector pYA3148, as calculated by the two-tailed Wilcoxon two-sample rank test.

Since PspA− Salmonella strains elicit some protection against pneumococcal infection, it was possible that the manifestation of the specific immunity elicited by the PspA+ S. typhimurium might be seen only if there was a concomitant induction of inflammation by the organism. To eliminate the confounding effects of the Salmonella-induced nonspecific immunity, we conducted passive protection studies with pooled sera from BALB/c mice immunized orally with strain χ4550(pYA3193). Control mice received serum from nonimmune BALB/c mice or, in one case, from mice immunized with the Salmonella vector YA3148. Sera from mice immunized with the vector alone, like sera from normal mice, did not protect against fatal infection in amounts as high as 0.1 ml of a 1/2 dilution. CBA/N mice injected i.p. with 0.1 ml of 1/2- or 1/10-diluted immune serum were significantly protected from i.v. challenge with almost 104 WU2 cells (Table 5). The protective effect of the immune serum was also seen when mice were challenged i.p. (Table 5). The LD50 of strain WU2 when injected i.p. or i.v. into CBA/N mice was <102 (data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Passive protection of mice from fatal pneumococcal infection with anti-PspA serum from mice orally immunized with S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193)a

| Challenge dose (log10) | Challenge route | Passive serum administered | Serum dilution | Days to death | P value vs PspA immuneb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.7 | i.v. | Nonimmune | 1/2 | 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 0.007 |

| i.v. | Vector immune | 2, 2, 3, 4, 4 | 0.029 | ||

| i.v. | PspA immune | 1/2 | 1, >21, >21, >21, >21, >21, >21, >21, >21 | ||

| 3.9 | i.v. | Nonimmune | 1/10 | 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 0.0086 |

| i.v. | PspA immune | 1/10 | 2, 3, 3, 4, >15, >15 | ||

| 3.0 | i.p. | Nonimmunec | 1/5 | 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4 | 0.038 |

| i.p. | PspA immune | 1/5 | 2, 3, 4, 5, >15, >15, >15 |

i.v. challenge studies were conducted with CBA/N recipients; i.p. challenge studies were conducted with BALB/cJ recipients.

P values comparing the days to death were calculated by using the Wilcoxon two-sample rank test between mice given PspA-immune sera and mice receiving vector-immune or nonimmune serum. In the case of the i.p. challenge, the P value was calculated between immune and the pooled data for nonimmune serum and no serum.

Includes two mice which received no serum.

DISCUSSION

These studies have demonstrated that oral immunization with an attenuated live Salmonella strain expressing PspA can be used to elicit protective humoral immunity to an encapsulated bacterium, S. pneumoniae. In these studies, protection against pneumococcal sepsis was measured. However, since the vaccine also induced mucosal immune responses, it was anticipated that immunization by this route might also induce protection against normal acquisition of pneumococci and carriage of that organism in the upper respiratory tract (42). Intraperitoneal immunization of mice with recombinant bacillus Calmette-Guerin (rBCG) expressing PspA induced a protective humoral response against pneumococcal challenge, but mucosal immune responses against PspA delivered by rBCG have not been reported (19). This is the first report of oral immunogenicity resulting from administration of a Δcya Δcrp-based recombinant Salmonella strain to rabbits.

The Salmonella vaccine was attenuated by deletion of the genes encoding adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP receptor protein. This approach can render wild-type Salmonella strains completely avirulent but still immunogenic (12). Since Salmonella strains with Δcya Δcrp mutations do not possess antibiotic resistance genes, they are appropriate for vaccines intended for use in humans or animals. The ability of strain χ4550(pYA 3193) to produce PspA at immunogenic concentrations was probably an important element of its ability to elicit high-level mucosal and serum antibody responses to PspA.

The vaccine strain was designed so that the fragment of PspA produced would contain the PspA signal peptide; the entire α-helical region, which makes up the N-terminal half of PspA; the central proline-rich region; and a portion of the first five repeats of the C-terminal choline binding domain of PspA. The PspA α-helical region contains the known protection-eliciting epitopes of PspA (22, 40). By including the proline-rich region and a portion of the repeat region in the construct, we hoped to optimize the conformational stability of the α-helical portion of the molecule. Since PspA, as well as the truncated fragment of it cloned here, has a leader sequence but lacks a membrane attachment site, it was anticipated that the cloned molecule would be secreted into the periplasmic space. This was observed, but there was a considerable (but smaller) amount of PspA that appeared in the supernatant fluid. Whether this represents secretion across the outer membrane or lysis and release of periplasmic proteins will have to be determined in future studies.

The use of recombinant live Salmonella vaccines for mucosal immunization may have several advantages over immunization with isolated antigens. With mucosal immunization with isolated antigens such as PspA, adjuvants must be used to obtain significant mucosal responses (42, 43). One advantage of using live S. typhimurium to produce the vaccine antigen in vivo is that the presence of the live Salmonella cells alleviates the need for any additional adjuvant. Another advantage is that the immunizing protein need not be produced in vitro, isolated, purified, and characterized. Finally, the ability of S. typhimurium to colonize gut tissue following oral administration should permit elicitation of strong mucosal as well as humoral immune responses.

The present study demonstrated that the recombinant Salmonella strain was well tolerated by both rabbits and mice. The S. typhimurium χ4550-PspA-based recombinant vaccine persisted in the spleen, liver, and gut lymphatic system. The elicitation of common mucosal immunity was apparent from the detection of anti-PspA antibodies in vaginal washings following oral immunization. The observation that the anti-LPS titers induced by strains χ4550(pYA3148) and χ4550(pYA3193) were comparable indicated that the expression of PspA by S. typhimurium χ4550(pYA3193) did not interfere with the immunogenic potential of the bacteria. Oral immunization combined with another route of administration (37), such as intranasal or systemic, might stimulate even better combined mucosal and humoral immune responses. It is likely that the combination of mucosal and systemic immunity to PspA will be more protective against natural infections than systemic immunity alone.

Mice orally immunized with PspA-expressing S. typhimurium were more resistant to pneumococcal infection than mice immunized with the Salmonella host (nonvaccine) strain. It was also observed, however, that compared to mice given no immunization, those immunized with the host strain were somewhat resistant to infection with pneumococci and exhibited a significant delay in time to death. This partial resistance elicited by the vector alone did not appear to be able to be transferred with serum and may have been the result of a nonspecific host immune response to immunization caused by the live Salmonella cells. These results are very reminiscent of our previous data showing that pneumococcal infection itself elicits a host immune response that can play a major role in extending the lives of mice infected with pneumococci (2, 3).

It is important to note that the host strain exhibited a greater capacity to colonize the livers and spleens of BALB/cJ mice (and presumably elicited more nonspecific host immunity) than did the PspA-producing strain. Thus, the contribution of the anti-PspA immunity to immunization-enhanced resistance in BALB/cJ mice may have been even greater than was apparent from these studies. The efficacy of the anti-PspA immunity was further documented by passive transfer studies, in which it was apparent that as little as 0.1 ml of a 1/10 dilution of serum from the immunized animals could provide statistically significant protection from a fatal pneumococcal infection. The fact that the oral vaccine elicited specific and nonspecific protection even 4 weeks postboost argues for the overall efficacy of live Salmonella oral vaccines.

This is the first report of an avirulent Δcya Δcrp-based recombinant oral Salmonella vaccine that has been employed in mouse protection studies by using a clinical human isolate of mouse-virulent S. pneumoniae WU2. Recombinant Salmonella strains may be a valuable vaccine vehicle for inducing primary protection against a wide range of pathogens which gain entry via mucosal surfaces. In addition, this vehicle has the potential to be an inexpensive delivery system for polyvalent vaccines. This demonstration that a mucosal attenuated Salmonella vaccine can elicit protection against systemic infection with pneumococci may encourage subsequent studies evaluating and identifying Salmonella attenuation systems that would be safe for immunization of young children. As a group, young children, especially those in developing countries, who may be malnourished or infected with other agents, may provide the most demanding environment for establishing the correct balance between attenuation and virulence of live bacterial and viral vector vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Janet Yother for E. coli(pJY4347) and Colynn Forman for assistance with S. pneumoniae WU2. We appreciate the excellent animal care provided by Dan Piatcheck (Biology Department Animal Facility, Washington University). We thank Josephine Clark-Curtiss for comments on the manuscript.

This research project was supported by the grants from the U.S. Public Health Service through the National Institutes of Health (DE06669 and AI21548) and from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Company.

REFERENCES

- 1.Austrian R A. Pneumococcal infections. In: Germanier R, editor. Bacterial vaccines. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1984. pp. 257–288. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benton K A, Everson M P, Briles D E. A pneumolysin-negative mutant of Streptococcus pneumoniae causes chronic bacteremia rather than acute sepsis in mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:448–455. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.448-455.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benton K A, Paton J C, Briles D B. Differences in virulence of mice among Streptococcus pneumoniae strains of capsular types 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are not attributable to differences in pneumolysin production. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1237–1244. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1237-1244.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briles D E, King J D, Gray M A, McDaniel L S, Swiatlo E, Benton K A. PspA, a protection-eliciting pneumococcal protein: immunogenicity of isolated native PspA in mice. Vaccine. 1996;14:858–867. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(96)82948-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briles, D. E., R. C. Tart, E. Swiatlo, J. P. Dillard, P. Smith, K. A. Benton, A. Brooks-Walter, M. J. Crain, S. K. Hollingshead, and L. S. McDaniel. Pneumococcal diversity: considerations for new vaccine strategies with an emphasis on pneumococcal surface protein A. (PspA). Clin. Microbiol. Rev., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Briles D E, Tart R C, Wu H-Y, Ralph B A, Russell M W, McDaniel L S. Systemic and mucosal protective immunity to pneumococcal surface protein A. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;797:118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brockman R E, Heppel L A. On the localization of alkaline phosphatase and cyclic phosphodiesterase in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1968;7:2554–2562. doi: 10.1021/bi00847a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardenas L, Clements J D. Stability, immunogenicity and expression of foreign antigens in bacterial vaccine vectors. Vaccine. 1993;11:126–135. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crain M J, Waltman II W D, Turner J S, Yother J, Talkington D E, McDaniel L S, Gray B M, Briles D E. Pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) is serologically highly variable and is expressed by all clinically important capsular serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3293–3299. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3293-3299.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtiss R., III Antigen delivery systems for analyzing host immune responses and for vaccine development. Trends Biotechnol. 1990;8:237–240. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(90)90184-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtiss R., III . Attenuated Salmonella strains as live vectors for the expression of foreign antigens. In: Woodrow G C, Levine M M, editors. New generation vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1990. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtiss R, III, Kelly S M. Salmonella typhimurium deletion mutants lacking adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP receptor protein are avirulent and immunogenic. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3035–3043. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3035-3043.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtiss R, III, Kelly S M, Gulig P A, Nakayama K. Selective delivery of antigens by recombinant bacteria. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1989;146:35–49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74529-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis R W, Douglas G J. New vaccine technologies. JAMA. 1994;271:929–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazerbaurer G L, Harayama S. Mutants in transmission of chemotactic signals from two independent receptors of Escherichia coli. Cell. 1979;16:617–625. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henrichsen J. Six newly recognized types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2759–2762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2759-2762.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janoff E N, O’Brien J, Thompson P, Ehret J, Meiklejohn G, Duvall G, Douglass J M J. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization, bacteremia, and immune response among persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:49–56. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jernigan D B, Cetron M S, Breiman R F. Defining the public health impact of drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: report of a working group. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1996;45:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langermann S, Palaszynski S R, Burlein J E, Koenig S, Hanson M S, Briles D E, Stover C K. Protective humoral response against pneumococcal infection in mice elicited by recombinant Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccines expressing PspA. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2277–2286. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luria S E, Burrous J W. Hybridization between Escherichia coli and Shigella. J Bacteriol. 1957;74:461–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.74.4.461-476.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marrie T J. Community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:501–515. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDaniel L S, Ralph B A, McDaniel D O, Briles D E. Localization of protection-eliciting epitopes on PspA of Streptococcus pneumoniae between amino acid residues 192 and 260. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:323–337. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDaniel L S, Scott G, Kearney J F, Briles D E. Monoclonal antibodies against protease sensitive pneumococcal antigens can protect mice from fatal infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 1984;160:386–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDaniel L S, Scott G, Widenhofer K, Carroll J M, Briles D E. Analysis of a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae recognized by protective monoclonal antibodies. Microb Pathog. 1986;1:519–531. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(86)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDaniel L S, Sheffield J S, Delucchi P, Briles D E. PspA, a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, is capable of eliciting protection against pneumococci of more than one capsular type. Infect Immun. 1991;59:222–228. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.222-228.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDaniel L S, Sheffield J S, Swiatlo E, Yother J, Crain M J, Briles D E. Molecular localization of variable and conserved regions of pspA, and identification of additional pspA homologous sequences in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90036-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakayama K, Kelly S M, Curtiss R., III Construction of an Asd+ expression vector: stable maintenance and high expression of cloned genes in a Salmonella vaccine strain. Bio/Technology. 1988;6:693–697. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neu H C. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science. 1992;257:1064–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paton J, Andrew P, Boulnois G, Mitchell T. Molecular analysis of the pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae: the role of pneumococcal proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:89–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts M, Chatfield S N, Dougan G. Salmonella as carriers of heterologous antigens. In: O’Hagen D T, editor. Novel delivery systems for oral vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1994. pp. 27–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts R B. Streptococcus pneumoniae. In: Mandell G L, Douglas R G, Bennet J E, editors. Infectious diseases and their agents. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. pp. 1142–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. p. E.3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schödel F. Prospects for oral vaccination using recombinant bacteria expressing viral epitopes. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:409–446. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schödel F, Kelly S M, Peterson D L, Milich D R, Curtiss R., III Hybrid hepatitis B virus core–pre-S proteins synthesized in avirulent Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella typhi for oral vaccination. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1669–1676. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1669-1676.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro E D, Berg A T, Austrian R, Schroeder D, Parcells V, Margolis A, Adair R K, Clemmens J D. Protective efficacy of polyvalent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1453–1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siber G R. Pneumococcal disease: prospects for a new generation of vaccines. Science. 1994;265:1385–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.8073278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan J, Nayak A, Curtiss III R, Rubino S. Effect of the route of immunization using recombinant Salmonella on mucosal and humoral immune responses. In: Chanock R M, Brown F, Ginsberg H S, Norrby E, editors. Molecular approaches to the control of infectious diseases. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talkington D F, Crimmins D L, Voellinger D C, Yother J, Briles D E. A 43-kilodalton pneumococcal surface protein, PspA: isolation, protective abilities, and structural analysis of the amino-terminal sequence. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1285–1289. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1285-1289.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talkington D F, Voellinger D C, McDaniel L S, Briles D E. Analysis of pneumococcal PspA microheterogeneity in SDS polyacrylamide gels and the association of PspA with the cell membrane. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:343–355. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tart R C, McDaniel L S, Ralph B A, Briles D E. Truncated Streptococcus pneumoniae PspA molecules elicit cross-protective immunity against pneumococcal challenge in mice. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:380–386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waltman W D, II, McDaniel L S, Gray B M, Briles D E. Variation in the molecular weight of PspA (pneumococcal surface protein A) among Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90008-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu H-Y, Nahm M, Guo Y, Russell M, Briles D E. Intranasal immunization of mice with PspA (pneumococcal surface protein A) can prevent intranasal carriage and infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:839–846. doi: 10.1086/513980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto M, McDaniel L S, Kawabata K, Briles D E, Jackson R J, McGhee J R, Kiyono H. Oral immunization with PspA elicits protective humoral immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:640–644. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.640-644.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yother J, Briles D E. Structural properties and evolutionary relationships of PspA, a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, as revealed by sequence analysis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:601–609. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.601-609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yother J, Handsome G L, Briles D E. Truncated forms of PspA that are secreted from Streptococcus pneumoniae and their use in functional studies and cloning of the pspA gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:610–618. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.610-618.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yother J, White J M. Novel surface attachment mechanism of the Streptococcus pneumoniae protein PspA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2976–2985. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2976-2985.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]