Abstract

Background:

Controlling high blood pressure (BP) continues to be a major concern because the associated complications can lead to an increased risk of heart, brain, and kidney disease. Those with hypertension, despite lifestyle and diet modifications and pharmacotherapy, defined as resistant hypertension, are at increased risk for further risk for morbidity and mortality. Understanding inflammation in this population may provide novel avenues for treatment.

Objectives:

This study aimed to examine a broad range of cytokines in adults with cardiovascular disease and identify specific cytokines associated with resistant hypertension.

Methods:

A secondary data analysis was conducted. The parent study included 156 adults with a history of myocardial infarction within the past 3 to 7 years and with a multiplex plasma analysis yielding a cytokine panel. A network analysis with lasso penalization for sparsity was performed to explore associations between cytokines and BP. Associated network centrality measures by cytokine were produced, and a community graph was extracted. A sensitivity analysis BP was also performed.

Results:

Cytokines with larger node strength measures were sTNFR2 and CX3. The graphical network highlighted six cytokines strongly associated with resistant hypertension. Cytokines IL-29 and CCL3 were found to be negatively associated with resistant hypertension, while CXCL12, MMP3, sCD163, and sIL6Rb were positively associated with resistant hypertension.

Discussion:

Understanding the network of associations through exploring oxidative stress and vascular inflammation may provide insight into treatment approaches for resistant hypertension.

Keywords: cytokines, hypertension, inflammation, inflammatory response, network analysis, resistant

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, with approximately 697,000 deaths annually, accounting for 1 in every 4 deaths (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2021). High blood pressure (BP) or hypertension is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease, leading to high morbidity and mortality (Whelton et al., 2018). Approximately 121.5 million or 47% of adults in the U.S. have hypertension (CDC, 2021). Despite the American Heart Association and Joint National Committee on hypertension focusing on hypertension, little progress has been made to affect the downstream effects of hypertension, such as stroke and chronic kidney disease. Interventions to manage hypertension are essential in improving health outcomes and cardiovascular disease mortality.

Current interventions focus on the traditional three-pronged approach of diet modification, medication adherence, and increased physical activity. Even with adherence to a low sodium diet, prescribed BP medications, and consistent physical activity, the landmark Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) revealed a subset of participants who continued to manifest hypertension: resistant hypertension (SPRINT Research Group, 2015). As a result of SPRINT, new BP classification guidelines were established in 2017 to define hypertension and offer comprehensive guidance on managing adults with hypertension to decrease the risk of overall cardiovascular disease complications and death (Whelton et al., 2018). This change in guidelines broadened the definition of hypertension and resulted in an increase in the prevalence of hypertension and those with resistant hypertension (rHTN). In fact, the prevalence of rHTN in U.S. adults is now 15.95%, representing a 4% increase compared with the previous 7th report of the Joint National Committee Blood Pressure Guidelines in 2003 (Patel et al., 2019). Those with rHTN, defined as BP remaining elevated despite the use of three or more antihypertensive medications of different classes at their maximally tolerated dose—with one ideally being a diuretic—have a marked increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Carey et al., 2018). Thus, rHTN has been identified as a high-priority area by the American Heart Association for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment (Carey et al., 2018).

Understanding mechanisms associated with rHTN would be a first step in developing therapeutics for treatment. The American Heart Association Scientific Statement (Carey et al., 2018) distinguishes that, as a subgroup, those with rHTN have not been widely studied. Consequently, further exploration of the multifactorial etiology of rHTN is warranted.

Well-recognized factors contributing to rHTN include obesity, excessive salt intake, Black race, being female, genetics, and living conditions (Acelajado et al., 2019). Another factor postulated to contribute to rHTN is the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Chu et al., 2022). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is triggered by the stress response, resulting in the increased release of cortisol and a cascade effect of physiological responses, including a release of catecholamines and vasoconstriction, resulting in a central stress response (Chu et al., 2022). Other novel mechanisms of rHTN, such as inflammation, warrant exploration.

Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow and cell oxygenation, resulting in cell damage or death and an inflammation response. Further, oxidative stress, a cellular imbalance of antioxidants and free radicals due to aging, environmental, or other factors, is also associated with inflammation. Studies have shown that oxidative stress and increased inflammatory processes coexist and are a common pathophysiological pathway for hypertension (Chamarthi et al., 2011; De Miguel et al., 2015). However, it is unclear if inflammation is a primary or a secondary effect of hypertension.

Studies of vascular inflammation related to atherosclerosis and hypertension have demonstrated the importance of small, secreted proteins known as cytokines. After cell injury, cytokines are released by immune system cells to regulate vascular dysfunction (Libby et al., 2011) and recruit other cells in the inflammatory and reparative process. Additionally, an increase in mean arterial pressure and plasma norepinephrine resulting from the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis response also stimulates the expression of the cytokines, specifically, interleukin (IL) IL-1B, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a; Barrows et al., 2019). Because hypertension limits perfusion—which may lead to cell damage, death, and ultimately, end-organ damage (McMaster et al., 2015)—the process results in the reinitiation of the inflammatory cascade. Prior studies have associated inflammation with hypertension and rHTN (Chen et al., 2019).

Determining inflammasomes associated with rHTN may assist in elucidating therapeutic strategies for intervention to reduce the rHTN and associated negative health outcomes. Understanding the complex interactions of the cytokine network in research is challenging due to the redundancy of cytokines. Statistical approaches may provide a better understanding of the cytokine networks and assist in developing testable predictions for therapies. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine a broad range of cytokines obtained through multiplex technology in a high-risk population with rHTN.

Methods

This study was exempted from the East Carolina University and Medical Center institutional review board approval as it was a secondary analysis of data collected to examine recurrence of myocardial infarction in adults. The original data in the parent study were collected from 2011 to 2014 from a convenience sample of adults (N = 156) with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction who were discharged within the prior 3 to 7 years from two area medical centers in the South Atlantic region, with average BP greater than or equal to systolic BP of 130mm Hg and on at least three antihypertensive agents. The parent study used a cross-sectional design to investigate the influence of factors on recurrent myocardial infarctions.

In the parent study (Abel et al., 2021), all participants had their BP assessed twice 5 min apart by an RN using the standardized protocols of the 7th report of the Joint National Committee for Measurement, and all completed demographic health information, including comorbidities and other physiological measures (height, weight). Participants provided all their pharmaceutical containers with the type of drugs and directions on each container. The research nurse recorded each medication, verbally read the drug and the dose regime, and confirmed with the participants that they were taking the medication as prescribed. All participants also provided a venous blood sample, collected and processed as previously published by Abel et al. (2021). Plasma not used in the primary cytokine analysis in the parent study was stored in a secured freezer at −81 Celsius using standardized recommended protocols. A multiplex cytokine assay was conducted in 2018 on frozen plasma (N = 156), resulting in the measurement of 62 cytokines. Cytokine results from the multiplex were used in our study, and rHTN was defined as a systolic BP level equal to or above 130 mmHg to correct for the change in the definition of rHTN. It was coded as a binary variable.

Network Analysis

Because directionality of cytokine-based associations was not assumed, an undirected graph was created using all cytokines and binary systolic BP (≥ 130 mmHg defined as rHTN, and < 130 mmHg defined as no rHTN). A nonparanormal skeptic approach (Liu et al., 2012) was utilized to address and mitigate potential nonnormality of the cytokine distributions. A graphical lasso estimation was performed using a conservative tuning parameter of 0.5 to control the sparsity level (Foygel & Drton, 2010) and to extract only the stronger associations for visualization.

Different standardized centrality measures of the network were calculated including (a) strength, which is measured by the weights of edges connected to each node and represents the strength of associations of that node with all other nodes in the network; (b) closeness, which is represented by the reciprocal of the sum of the lengths of the shortest paths with all other nodes and represents how close the node is to all other nodes in the network; (c) betweenness, which is measured by how often a node sits on the shortest path between other nodes and represents how central it is within the network; and (d) expected influence, which is similar to strength but accounts for differential signs in edge weights when some associations are positive but others are negative (Robinaugh et al., 2016). Absolute edge weights were calculated, and communities (groups of nodes with similar characteristics) of cytokines and BP were detected and used to define neighborhoods. A heatmap was also produced to represent all partial correlations across variables, with clustering represented through a dendrogram, and a sensitivity analysis was performed using a continuous BP metric instead of the rHTN binary marker. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.3).

Results

The total sample (N = 156) comprised primarily males (57%, n = 89) and White participants (68%, n = 106). The average age was 65.4 (SD = 12.1). Ninety-six participants were married (62%), and most adults had obtained a high school graduate equivalency degree or below (51%, n = 79). The average BMI for the total sample was 31.1 (SD = 7.3), with an obesity prevalence of 52% (BMI ≥ 30). The following cardiac comorbidities for this sample included: Only 36 (23%) currently smoked, 57 (37%) had diabetes, 99 (56%) had high cholesterol, 88 (65%) had BMIs indicating obesity, and 66 (42%) stated participating in physical activity daily.

Those with rHTN (n = 88) had an average age of 66.5 (SD = 11.79), were primarily White (71%; n = 62) and male (56%; n = 49) adults. Fifty-two participants were married (59%), and most (56%, n = 49) had received high school graduate equivalency education or below. The mean BMI for those with rHTN was 30.88 (SD = 7.79).

Individuals without rHTN (n = 68) were similar to those with rHTN, as the group was composed mainly of males (58%, n = 40) and White adults (65%, n = 44). The average age and BMI were 63.9 (SD = 12.5) and 31.39 (SD = 7.01). Most (56%; n = 38) were considered obese. Forty-four (65%) were married, and 30 (44%) had a high school degree or below. Descriptive statistics by rHTN status are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Participants With and Without Resistant Hypertension (N = 156) *

| Baseline Characteristic | rHTN (n=88) | No rHTN (n=68) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 62 | 70.5 | 44 | 64.7 |

| Not white | 26 | 29.5 | 24 | 35.3 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 39 | 44 | 28 | 41 |

| Male | 49 | 56 | 40 | 59 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 9 | 10.2 | 7 | 10.3 |

| Married/partnered | 52 | 59.1 | 44 | 64.7 |

| Divorced | 15 | 17 | 12 | 17.6 |

| Widowed | 10 | 11.4 | 5 | 7.4 |

| Highest educational Level | ||||

| GED or less | 49 | 55.7 | 30 | 44.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree or less | 37 | 42 | 30 | 44.1 |

| Some graduate school or more | 2 | 2.2 | 8 | 11.8 |

Note. Participants with rHTN were an average 66.5 years old (SD=11.79). Participants without rHTN were an average age of 63.9 (SD=12.50). Body Mass Index were an average of 30.88 (SD=7.79) in those with rHTN and an average of 31.39 (SD=7.01) in those with no rHTN. rHTN = resistant hypertension; BMI = Body Mass Index; MI = Myocardial Infarction; GED = Graduate Equivalency Degree

no significant difference noted for each variable

n = 46 Black (1 other and 3 Asian)

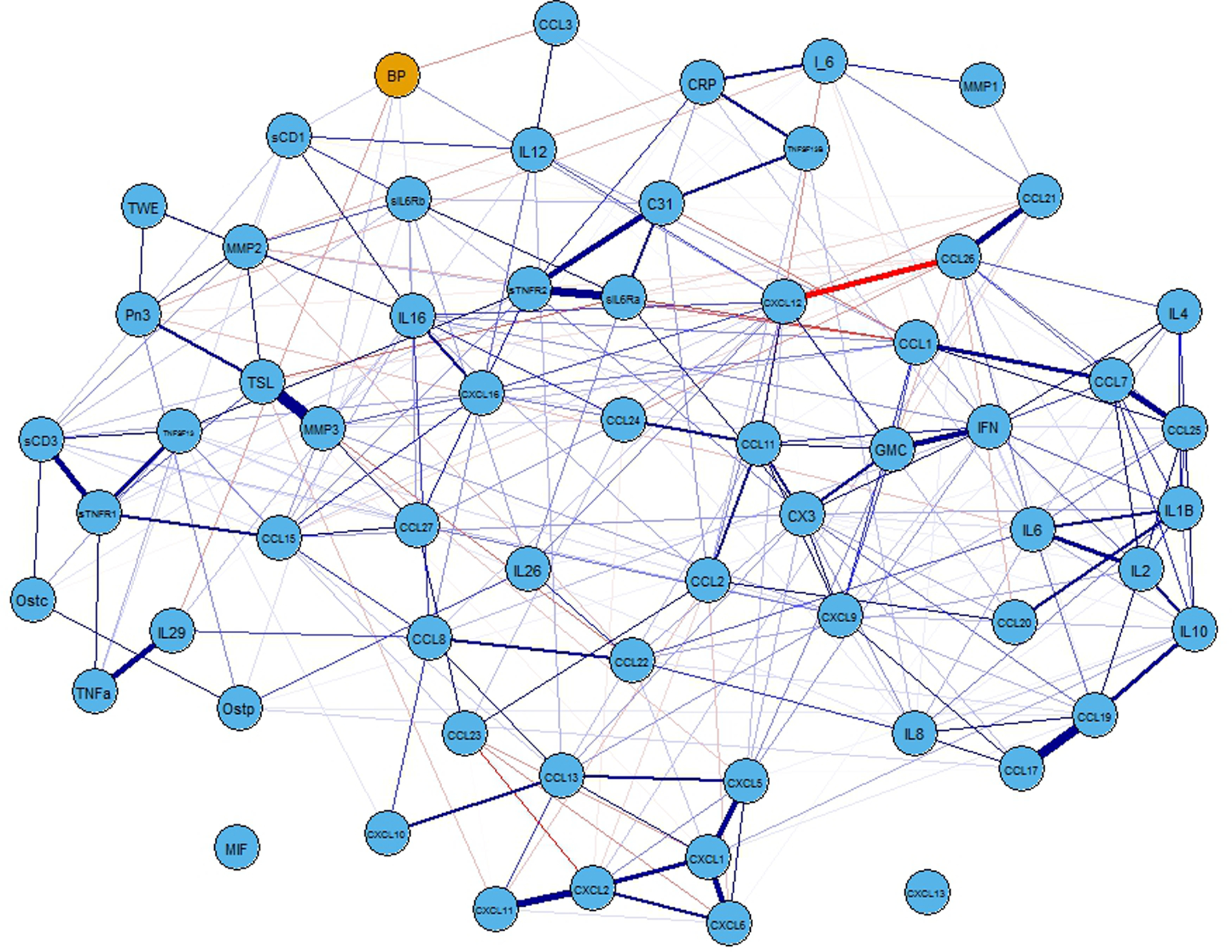

A comprehensive list of all cytokines measured from all participants is noted in Table 2. Because the distributions of most cytokines were largely skewed, Table 2 includes medians and interquartile ranges, as well as percentages of missing observations across all participants. Missing cytokine information ranged from 3.21% (Chitinase3like1, CRP-hs, IL-29, IL-6, MMP2, MMP3, Osteocalcin, Osteopontin, sCD30, sIL6Ra, sIL6Rb, sTNFR1, sTNFR2, TNFa, TNFSF13B, TSLP, TWEAK) to 19.23% (IL1B). Figure 1 portrays the full network for all cytokines and systolic BP (binary).

TABLE 2.

Medians, interquartile ranges, and missing percentages for cytokines and blood pressure for all participants

| Cytokine | Median | IQR | Missing (%) | Cytokine | Median | IQR | Missing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL1 | 16.16 | 10.16 | 3.85 | GMCSF | 23.79 | 25.49 | 3.85 |

| CCL11 | 20.63 | 14.97 | 3.85 | IFNg | 16.41 | 10.46 | 3.85 |

| CCL13 | 25.81 | 16.92 | 3.85 | IL10 | 11.22 | 8.63 | 4.49 |

| CCL15 | 1434 | 1093.6 | 6.41 | IL12p70 | 0.3 | 0.23 | 3.85 |

| CCL17 | 50.31 | 71.69 | 3.85 | IL16 | 135.07 | 79.18 | 3.85 |

| CCL19 | 123.43 | 140.43 | 3.85 | IL1B | 1.15 | 0.69 | 19.23 |

| CCL2 | 13.56 | 10.63 | 3.85 | IL2 | 5.34 | 4.1 | 3.85 |

| CCL20 | 2.88 | 2.55 | 3.85 | IL26 | 3.85 | 2.9 | 5.77 |

| CCL21 | 1304.5 | 939.52 | 3.85 | IL-29 | 13.73 | 6.28 | 3.21 |

| CCL22 | 245.15 | 161.4 | 3.85 | IL4 | 4.72 | 1.61 | 10.9 |

| CCL23 | 69.22 | 65.91 | 3.85 | IL6 | 3.87 | 2.43 | 3.85 |

| CCL24 | 129.35 | 133.43 | 4.49 | IL8 | 5.2 | 2.69 | 3.85 |

| CCL25 | 148.95 | 95.4 | 3.85 | Interleukin_6 | 2.61 | 2.43 | 3.21 |

| CCL26 | 4.97 | 6.7 | 3.85 | MIF | 297.59 | 432.86 | 3.85 |

| CCL27 | 265.04 | 140.21 | 3.85 | MMP1 | 324.72 | 359.53 | 3.85 |

| CCL3 | 2.68 | 1.52 | 9.62 | MMP2 | 6512 | 4815 | 3.21 |

| CCL7 | 35.25 | 26.54 | 3.85 | MMP3 | 1300 | 860.58 | 3.21 |

| CCL8 | 15.61 | 9.74 | 3.85 | Osteocalcin | 487.04 | 410.34 | 3.21 |

| Chitinase3like1 | 2663 | 1758 | 3.21 | Osteopontin | 6866 | 5511 | 3.21 |

| CRPFinal | 2.91 | 3.19 | 3.21 | Pentraxin3 | 161.43 | 121.63 | 3.85 |

| CX3CL1 | 64.76 | 48.51 | 3.85 | sCD163 | 20657.5 | 10516 | 3.85 |

| CXCL1 | 73.21 | 35.34 | 3.85 | sCD30 | 90.92 | 55.75 | 3.21 |

| CXCL10 | 45.67 | 26.13 | 3.85 | sIL6Ra | 1037 | 745.72 | 3.21 |

| CXCL11 | 5.7 | 4.98 | 3.85 | sIL6Rb | 9424 | 2446 | 3.21 |

| CXCL12 | 727.16 | 809.09 | 3.85 | sTNFR1 | 829.28 | 426.35 | 3.21 |

| CXCL13 | 4.93 | 2.97 | 3.85 | sTNFR2 | 305.69 | 408.82 | 3.21 |

| CXCL16 | 132.77 | 60.77 | 3.85 | TNFa | 1.29 | 1.32 | 3.21 |

| CXCL2 | 133.26 | 136.15 | 3.85 | TNFSF13 | 30629 | 20955 | 5.77 |

| CXCL5 | 215.4 | 157.66 | 17.95 | TNFSF13B | 2285 | 1120.5 | 3.21 |

| CXCL6 | 13.26 | 9.91 | 3.85 | TSLP | 11.77 | 7.05 | 3.21 |

| CXCL9 | 122.34 | 104.44 | 3.85 | TWEAK | 65.89 | 30.27 | 3.21 |

| Blood Pressure | Measure | IQR | % Missing | ||||

| *Blood Pressure Marker % | 56.41 | - | 0.00 | ||||

| Median Systolic | 131.0 | 28.5 | 0.00 | ||||

| Median Diastolic | 78.0 | 19.25 | 0.00 | ||||

Note. IQR=Interquartile range

Blood pressure marker is defined as having a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg.

FIGURE 1.

Full network representation of the associations among all cytokines and blood pressure. Nodes (circles) represent the cytokines (blue)) and the blood pressure (defined as having a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg: orange) marker. Edges connecting the nodes represent the sign (positive=purple) and strength (thicker=stronger) of the associations between each connected pair of nodes. Note. mmHg = millimeters of mercury

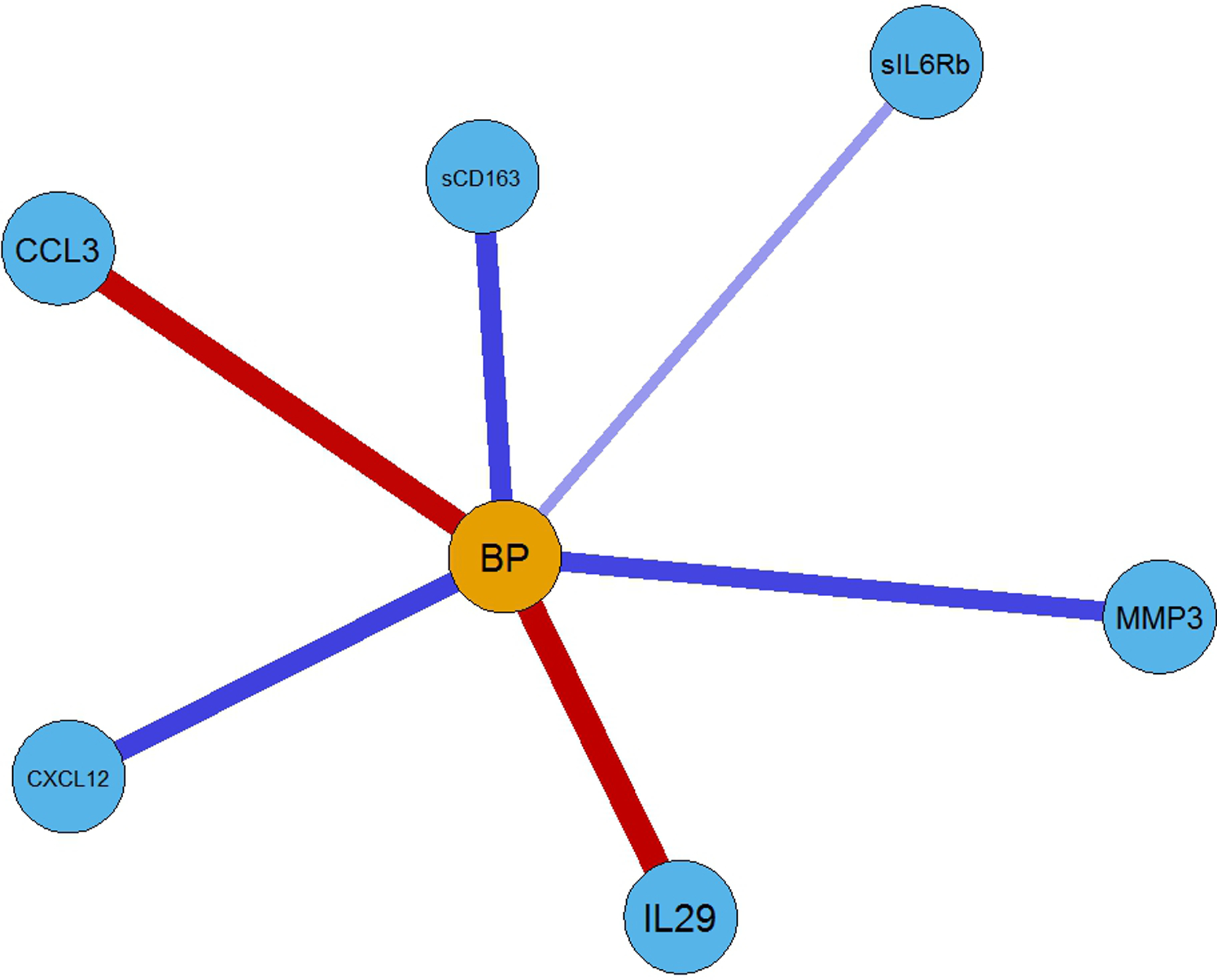

Although a conservative penalization parameter was used to induce sparsity in the network, the resulting graph is still very dense (Figure 1). To better visualize the vertices connecting nodes to high systolic BP status, Figure 2 contains a subgraph portraying only the nodes connected to this variable, two of them representing negative associations (CCL3 and IL-29), and four representing positive associations (CXCL12, MMP3, sCD163, and sIL6Rb). Because inflammation is associated with obesity, we examined BMI and cytokines related to rHTN. BMI was weakly associated with only CXCL12 (r = .23, p < .01) and sCD163 (r = .24; p < .01).

FIGURE 2.

Partial network representation (subgraph of Figure 1) of the associations of the cytokines connected to the blood pressure (defined as having a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg) marker. Note: BP = Blood Pressure

Supplemental Figure 1 shows a partial correlation heatmap, providing an additional visualization of the network associations, with darker cells corresponding to stronger associations and related hierarchical-clustered dendrograms for the cytokines and BP using the network’s raw inputs (partial correlations).

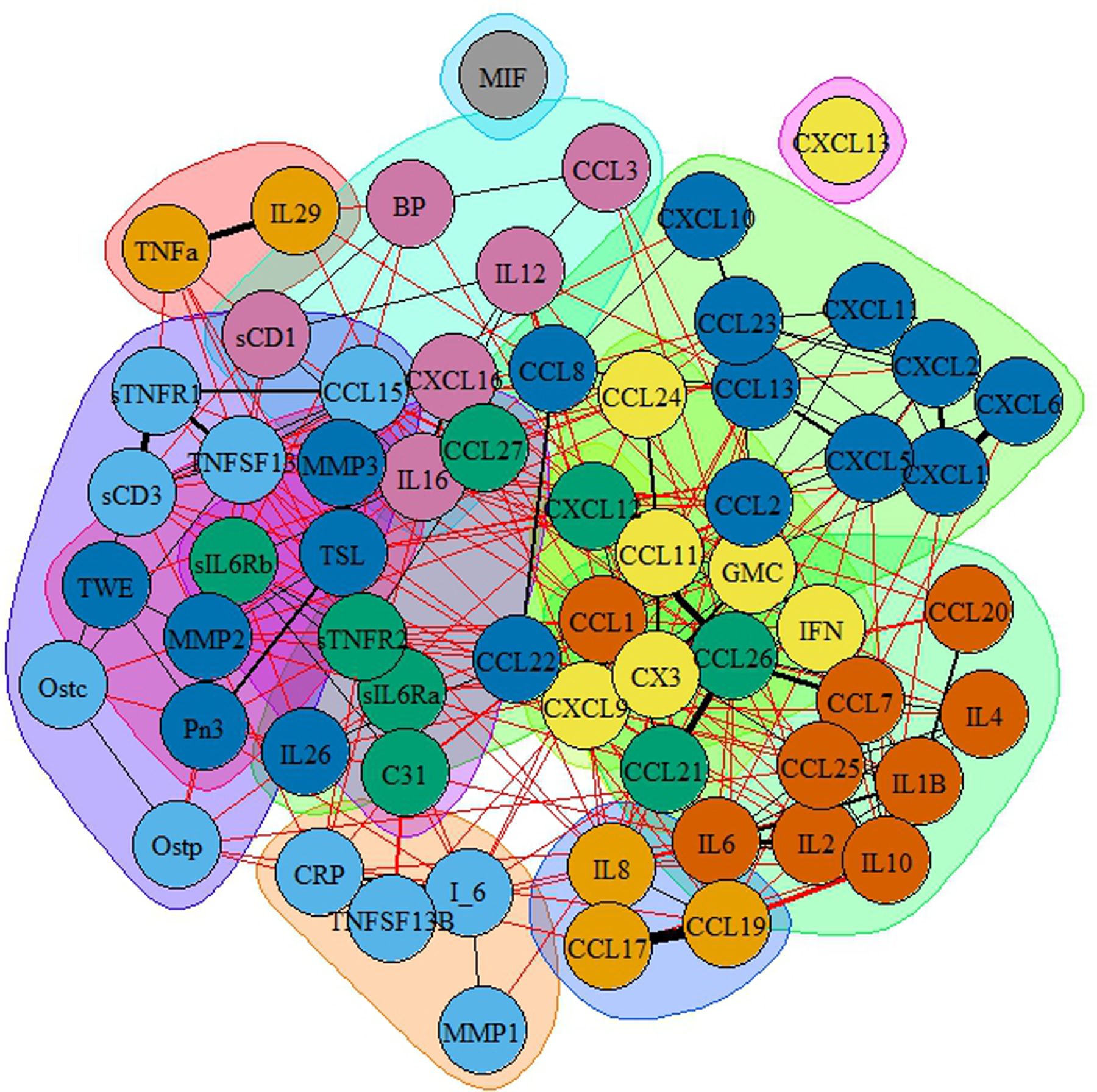

Supplemental Figure 2 contains multiple normalized centrality measures by node, sorted by node strength. The left panel represents the strength of each of the nodes. The cytokines with larger strength measures were sTNFR2 and CX3, while CXCL13 and MIF were found to have the lowest strength. Figure 3 contains a community graph built on positive edge weighting. BP appears in a relatively sparse community, with several communities largely populated.

FIGURE 3.

Community graphs based on propagating levels for the full network. Communities are shaded in the same color.

Upon further analysis, when performing an exploratory network analysis on all the participants, using the continuous BP measures (both systolic and diastolic), the resulting network (Supplemental Figure 3) noted two cytokines, Pentraxin3 and CXCL12, with sufficient strength after lasso penalization. Interestingly, neither is directly associated with rHTN, defined by systolic BP. In fact, these are indirectly related to systolic BP through the diastolic BP. Only one of the cytokines also appeared in the primary network (CXCL12).

Discussion

This study is the first to measure a large range of cytokines in those with prior cardiovascular disease events who have rHTN. Hypertension initiates an immune response. The various subsets of immune cells, including chemokines and cytokines, comprise cellular environment of hypertensive organs. These cells have both protective/reparative and inflammatory actions that may facilitate hypertensive end-organ damage (Rudemiller & Crowley, 2017; Zhang & Crowley, 2015). A subgroup of cytokines, known as chemokines, has been extensively studied in animal models (Rudemiller & Crowley, 2017) and was found to stimulate the migration of white blood cells (Hughes & Nibbs, 2018), resulting in an infiltration of immune cells into the kidney vasculature and central nervous system. No human studies were found that comprehensively examined cytokine panels in those with hypertension or rHTN. In our sample, those post-myocardial infarction individuals were all under medical management for cardiovascular disease, with over half classified as having rHTN.

Studies have examined select cytokines associated with hypertension. Cytokines associated with hypertension include CRP (Salles et al., 2007), IL-6, TNF-a, TGF b (Chen et al., 2019), CCL2, CCL5, CXCL8, CXCL16, CS3CL1, and others (McMaster et al., 2015; Mikolajczyk et al., 2021); however, it remains unknown which cytokines are associated with rHTN. CXCL2 has been associated with atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, obesity, and diabetes (Guo et al., 2020). Moreover, other cytokines, such as IL-29, affect comorbid conditions such as obesity and diabetes, contributing to atherosclerosis and hypertension (Lin et al., 2020), but rHTN was not examined. There are multiple complex interactions of cytokines, some of which influence, overlay, and intercommunicate. In our sample, six cytokines were associated with rHTN. The cytokines IL-29 and CCL3 had a negative association with rHTN status, whereas CXCL12, MMP3, sCD163, and sIL6Rb were positively associated with rHTN status.

The mechanism(s) associated with high BP and the associated inflammatory cascading events are not clear (Odewusi & Osadolor, 2019). IL-29 is regulated by viral infections (Doyle et al., 2006) that activate a downstream cellular response. Thus, IL-29 is often present in viral liver diseases as well as autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, osteoarthritis, and systemic sclerosis (Wang et al., 2019). No studies were found that explored the direct relationship between IL-29 and rHTN. A recent animal study noted an increase of IL-29 associated with bone morphogenetic protein 2 in calcified carotid arteries. Lin et al. (2020) found that IL-29 was produced in adipose tissue and promoted inflammation. However, our results noted a negative association between IL-29 and rHTN status. However, more complex causal associations with other cytokines may influence these results.

The proinflammatory cytokine CCL3 is a member of the CC subfamily of chemokines (Warrington et al., 2011) and is also referred to as macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1α). In an animal model, CCL3 was found in acute inflammation and increased atherosclerotic lesion formation, contributing to atherosclerosis (de Jager et al., 2013). In humans, CCL3 (Dregoesc et al., 2022), along with CCL2 (Tucci et al., 2006) and CCL5 (Krebs et al., 2012) were found to be associated with atherosclerosis and hypertension. Gibaldi et al. (2020) found an association between CCL3 and heart infection with increased levels of cardio injury in animal models. Because we did not measure white blood cells or query current infectious processes, we cannot determine if this negative relationship was due to confounding inflammation. Another possibility for the negative association may be that atherosclerosis was stable. Although there is a clear association between CCL3 and heart disease, the negative relationship of CCL3 with rHTN suggests other possible mechanisms.

Of the four cytokines (sCD163, MMP3, CXCL12) found to be positively associated with rHTN, soluble CD163 (sCD163) had the closest relationship. As a scavenger receptor, sCD163 is produced by monocytes and macrophages as an anti-inflammatory response. Primarily, sCD163 protects tissues from inflammation and increases with acute and chronic inflammation. As such, sCD163 is associated with atherosclerosis and is correlated with coronary artery disease (Aristoteli et al., 2006) and pulmonary artery hypertension (Jasiewicz et al., 2014). The rationale for this finding may be related to the sample who had experienced at least one myocardial infarction, as atherosclerosis is associated with coronary heart disease.

The enzyme matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3) was also positively associated with rHTN in this study. High BP increases arterial wall remodeling, and this remodeling results in the recruitment of inflammatory cells that release proinflammatory cytokines. Expressed by macrophages, MMP3 increases during this remodeling and contributes to arterial stiffness (Bisogni et al., 2020). The genotype of MMP3 was also noted to predict the size of arterial calcified lesions when adjusting for hypertension and other multimorbidities that affect coronary morbidity (Pöllänen et al., 2002). As MMP3 affects extracellular matrix remodeling, it establishes proteolytic activity of plaque, resulting in a break in the plaque and increasing the risk of a stroke or myocardial infarction (Sherva et al., 2011). As hypertension is one of the major morbidities associated with cardiovascular remodeling, our results of increased MMP3 with rHTN are understood. However, whether this relates to remodeling or the result of rHTN is unclear.

The proinflammatory chemokine CXCL12, also noted as stromal cell-derived factor-1, also plays a role in vascular disease. The expression of CXCL12 occurs in neurons, heart, lung, liver, spleen, platelets, and bone marrow. This cytokine and the receptor (CXCR4) are associated with angiogenesis. However, the role of CXCL12 in atherosclerosis is not clear (Döring et al., 2014). In animal studies, CXCL12 increased mean BP and heart rate.

Further, those animals with heart failure had greater production of CXCL12 than the sham (Wei et al., 2012). In adults, the correlation between CXCL12 and systolic BP and left ventricular mass index was noted in one study of those with chronic kidney disease (Klimczak-Tomaniak et al., 2018). Concentrations of CXCL12 are also increased in those with pulmonary arterial hypertension, and an increased level is associated with poorer outcomes for this population (McCullagh et al., 2015). It is unclear why CXCL12 is increased in those with rHTN in this study. Because no studies were found examining CXCL12 and rHTN, further research is needed and should include measures of pulmonary hypertension and heart failure.

The cytokine soluble interleukin-6 receptor beta (sIL6rb), also known as glycoprotein 130 or CD130, had a positive but weaker relationship to rHTN. Interleukin-6 is a major proinflammatory cytokine in chronic inflammation, and sIL6rb is one of the receptors. Hypertension and IL6 are positively correlated (Tanase et al., 2019) as hypertension stimulates an inflammatory response via activator of transcription signaling through sIL6rb. Persons with hypertension have higher IL-6 levels than controls, and IL-6 increased with angiotensin II in both controls and those with hypertension. Thus, angiotensin II was inflammatory (Chamarthi et al., 2011). Those with rHTN may not have fully attenuated angiotensin II, resulting in an increase in the receptor SIL6rb.

When exploring the associations using continuous systolic and diastolic BP measures, only two cytokines, Pentraxin3 and CXCL12, had sufficient strength for an association after lasso penalization. Interestingly, none of the cytokines were directly associated with the systolic BP but indirectly related to the systolic BP through the diastolic BP. One of those cytokines also appeared in the primary network: CXCL12. Van der Vorst et al.’s (2015) report on CXCL12 having a protective function in atherosclerotic lesion development, which we would expect in our population of those with post-myocardial infarction. Whereas Pentrazin3 did not appear in the primary network. Although Pentrazin3 has been found to be elevated in beginning stages of hypertension (Parlak et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2019), it has not been explored in those with rHTN. Despite this, it is clear from this additional sensitivity analysis that CXCL12 is potentially associated with rHTN status and increased hypertension.

In summary, this study of participants 3 to 7 years post-myocardial infarction highlights cytokines associated with rHTN status. While cytokines relating to our findings have been studied, no studies examined cytokines groups in those with rHTN. Inflammation may be amplified in the presence of comorbid conditions, such as obesity (Alberts et al., 2002); however, our finding cannot be explained solely by comorbid conditions as BMI was only weakly associated with two cytokines: CXCL12 and sCD163. Examining other comorbid conditions associated with inflammation and rHTN may yield different results. Thus, as various factors influence the immune response and must be considered when reviewing data, these findings should be considered exploratory. However, because rHTN may result in end-organ damage, such as chronic kidney disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke, examining the role of inflammation may be important in understanding potential therapeutic targets for this high-risk population.

Limitations

The cross-sectional convenience sample was restricted to a specific geographical area of the southeastern U.S. where lifestyle and socioeconomic status do not reflect the general population. Further, epigenetics may have influenced inflammatory responses. According to Lackland (2014), racial disparities are associated with hypertension in the southeast, with a higher cardiovascular disease risk factor. The majority of our sample consisted of male and White participants; therefore, findings should be interpreted with caution when applying to female populations and Black individuals or those identifying with a race other than White. Further studies should specifically focus on these populations, which are underrepresented in research and may benefit the most from findings related to rHTN. Although we could calculate BMI in our sample, we did not account for diet and salt intake of participants, nor did we control for anti-inflammatory medications in our analyses. Lastly, we are missing some cytokine data due to limited serum specimens.

Despite the limitations, our data have many strengths. Although the samples were drawn prior to the 2017 BP classification guidelines, we reclassified those according to their recorded BP. We had access to a very specific population, providing a focused sample. Those with rHTN live with a complex condition that often requires an individualized approach to care. Nurses could potentially identify subgroups of patients with similar cytokine profiles by examining associations between cytokines and inflammation. This understanding could support the development of personalized care plans targeting inflammatory pathways, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes. Further research is warranted.

Conclusion

Through various analyses, we determined that the associations of the cytokines connected to the rHTN were CCL3 and IL-29, representing negative associations, and CXCL12, MMP3, sCD163, and sIL6Rb, representing positive associations. These cytokines are potential biomarkers for poor rHTN and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease outcomes. Understanding the network of associations through exploring oxidative stress and vascular inflammation may provide further insight for nurse scientists in designing future studies, as well as for nurse providers in implementing new treatment approaches for rHTN, especially in high-risk populations.

Supplementary Material

This study was exempted from the East Carolina University and Medical Center institutional review board approval as it was a secondary analysis of data collected to examine recurrence of myocardial infarction in adults.

Funding Disclosure:

No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: No conflicts of interests noted by the authors.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Conduct of Research: This study was exempted from IRB approval, as it was a secondary analysis of data collected to examine recurrence of myocardial infarction in adults.

Contributor Information

Linda P. Bolin, College of Nursing, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Patricia B. Crane, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC.

Laura H. Gunn, Department of Public Health Sciences & School of Data Science, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC.

References

- Abel WM, Scanlan LN, Horne CE & Crane PB (2021). Factors associated with myocardial infarction reoccurrence. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 37, 359–367. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acelajado MC, Hughes ZH, Oparil S, & Calhoun DA (2019). Treatment of resistant and refractory hypertension. Circulation Research, 124, 1061–1070. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, & Walter P (2002). The adaptive immune system. In Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, & Walter P, Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed). Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- Aristoteli LP, Moller HJ, Bailey B, Moestrup SK, & Kritharides L (2006). The monocytic lineage specific soluble CD163 is a plasma marker of coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis, 184, 342–347. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows IR, Ramezani A, & Raj DS (2019). Inflammation, immunity, and oxidative stress in hypertension-partners in crime? Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 26, 122–130. 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni V, Cerasari A, Pucci G, & Vaudo. G. (2020). Matrix metalloproteinases and hypertension-mediated organ damage: Current insights. Integrated Blood Pressure Control, 2020, 157–169. 10.2147/IBPC.S223341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, Brook RD, Daugherty SL, Dennison- Himmelfarb CR, Egan BM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Judd E, Lackland DT, Laffer CL, Newton-Cheh C, Smith S, M., Taler SJ, Textor SC, Turan TN, & White WB (2018). Resistant hypertension: Detection, evaluation, and management: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension, 72, e53–e90 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Facts about Hypertension. Hypertension cascade: Hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control estimates among U.S. adults aged 18 Years and older applying the criteria from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association’s 2017 Hypertension guideline—NHANES 2015–2018. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm

- Chamarthi B, Williams GH, Ricchiuti V, Srikumar N, Hopkins PN, Luther JM, Jeunemaitre X, & Thomas A (2011). Inflammation and hypertension: The interplay of interleukin-6, dietary sodium, and the renin–angiotensin system in humans. American Journal of Hypertension, 24, 1143–1148. 10.1038/ajh.2011.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bundy JD, Hamm LL, Hsu C-Y, Lash J, Miller ER III, Thomas G, Cohen DL, Weir MR, Raj DS, Chen H-Y, Xie D, Rao P, Wright JT Jr., Rahman M, & He J (2019). Inflammation and apparent treatment-resistant hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease. Hypertension, 73, 785–793. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Marwaha K, Sanvictores T, & Ayers D (2022). Physiology, stress reaction. In: StatPearls StarPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jager SCA, Bot I, Kraaijeveld AO, Korporaal SJA, Bot M, van Santbrink PJ, van Berkel TJC, Kuiper J, & Biessen E A L. (2013). Leukocyte-specific CCL3 deficiency inhibits atherosclerotic lesion development by affecting neutrophil accumulation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 33, e75–e83. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel C, Rudemiller NP, Abais JM, & Mattson DL (2015). Inflammation and hypertension: New understandings and potential therapeutic targets. Current Hypertension Reports, 17, 507. 10.1007/s11906-014-0507-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring Y, Pawig L, Weber C, & Noels H (2014). The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Fronters in Physiology, 5, 212. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle SE, Schreckhise H, Khuu-Duong K, Henderson K, Rosler R, Storey H, Yao L, Liu H, Barahmand-pour F, Sivakumar P, Chang C, Birks C, Foster D, Clegg CH, Wietzke-Braun P, Mihm S & Klucher KM (2006). Interleykin-29 uses a type 1 interferon-like program to promote antivirial response in human hepatocytes. Hepatology, 44, 896–906. 10.1002/hep.21312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dregoesc MI, Tigu AB, Bekkering S, van der Heijden CDCC, Bolboacǎ SD, Joosten LAB, Visseren FLJ, Netea MG, Riksen NP, & Iancu AC (2022). Relation between plasma proteomics analysis and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 9, 731325. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.731325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foygel R & Drton M (2010). Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 23, 2020–2028. 10.48550/arXiv.1011.6640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibaldi D, Vilar-Pereira G, Pereira IR, Silva AA, Barrios LC, Ramos IP, Mata dos Santos HA, Gazzinelli R, & Lannes-Vieira J (2020). CCL3/Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α is dually involved in parasite persistence and induction of a TNF- and IFNγ-enriched inflammatory milieu in Trypanosoma cruzi-induced chronic cardiomyopathy. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 306. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L-Y, Yang F, Peng L-J, Li Y-B, & Wang A-P (2020). CXCL2, a new critical factor and therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension, 42, 428–437. 10.1080/10641963.2019.1693585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CE, & Nibbs RJB (2018). A guide to chemokines and their receptors. FEBS Journal, 285, 2944–2971. 10.1111/febs.14466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasiewicz M, Kowal K, Kowal-Bielecka O, Knapp M, Skiepko R, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A, Sobkowicz B, Musial WJ, & Kaminski KA (2014). Serum levels of CD163 and TWEAK in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cytokine, 66, 40–45. 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimczak-Tomaniak D, Pilecki T, Żochowska D, Sieńko D, Janiszewski M, Pączek L, & Kuch M (2018). CXCL12 in patients with chronic kidney disease and healthy controls: Relationships to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure and echocardiographic measures. Cardiorenal Medicine, 8, 249–258. 10.1159/000490396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C, Fraune C, Schmidt-Haupt R, Turner J-E, Panzer U, Quang MN, Tannapfel A, Velden J, Stahl RA, & Wenzel UO (2012). CCR5 deficiency does not reduce hypertensive end-organ damage in mice. American Journal of Hypertension, 25, 479–486. 10.1038/ajh.2011.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackland DT (2014). Racial differences in hypertension: Implications for high blood pressure management. American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 348, 135–138. 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Ridker PM, & Hansson GK (2011). Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature, 473, 317–325. 10.1038/nature10146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T-Y, Chiu C-J, Kuan C-H, Chen F-H, Shen Y-C, Wu C-H, & Hsu Y-H (2020). IL-29 promoted obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 17, 369–379. 10.1038/s41423-019-0262-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Han F, Yuan M, Lafferty J, & Wasserman L (2012). The nonparanormal skeptic 10.48550/arXiv.1206.6488 [DOI]

- McMaster WG, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, & Harrison DG (2015). Inflammation, immunity, and hypertensive end-organ damage. Circulation Research, 116, 1022–1033. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh BN, Costello CM, Li L, O’Connell C, Codd M, Lawrie A, Morton A, Kiely DG, Condliffe R, Elliot C, McLoughlin P, & Gaine S (2015). Elevated plasma CXCL12α is associated with a poorer prognosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS ONE, 10, e0123709. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk TP, Szczepaniak P, Vidler F, Maffia P, Graham GJ, & Guzik TJ (2021). Role of inflammatory chemokines in hypertension. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 223, 107799. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odewusi OO, & Osadolor HB (2019). Interleukin 10 and 18 levels in essential hypertensive. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 23, 819–824. 10.4314/jasem.v23i5.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parlak A, Aydoğan U, Lyisoy A, Dikililer MA, Kut A, Çakir E, & Sağlam K (2012). Elevated pentraxin-3 levels are related to blood pressure levels in hypertensive patients: An observational study. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg, 12, 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel KV, Li X, Kondamudi N, Vaduganathan M, Adams-Huet B, Fonarow GC, Vongpatanasin W, & Pandey A (2019). Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension in the United States according to the 2017 High Blood Pressure Guideline. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94, 776–782. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöllänen PJ, Lehtimäki T, Ilveskoski E, Mikkelsson J, Kajander OA, Laippala P, Perola M, Goebeler S, Penttilä A, Mattila KM, Syrjäkoski K, Koivula T, Nikkari ST, & Karhunen PJ (2002). Coronary artery calcification is related to functional polymorphism of matrix metalloproteinase 3: The Helsinki Sudden Death Study. Atherosclerosis, 164, 329–335. 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00107-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh DJ, Millner AJ, & McNally RJ (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 747–757. 10.1037/abn0000181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudemiller NP, & Crowley SD (2017). The role of chemokines in hypertension and consequent target organ damage. Pharmacological Research, 119, 404–411. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles GF, Fiszman R, Cardoso CRL, & Muxfeldt ES (2007). Relation of left ventricular hypertrophy with systemic inflammation and endothelial damage in resistant hypertension. Hypertension, 50, 723–728. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherva R, Ford CE, Eckfeldt JH, Davis BR, Boerwinkle E, & Arnett DK (2011). Pharmacogenetic effect of the stromelysin (MMP3) polymorphism on stroke risk in relation to antihypertensive treatment: The genetics of hypertension associated treatment study. Stroke, 42, 330–335. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPRINT Research Group. (2015). A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. New England Journal of Medicine, 373, 2103–2116. 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanase DM, Gosav EM, Radu S, Ouatu A, Rezus C, Ciocoiu M Costea CF, & Floria M (2019). Arterial hypertension and interleukins: Potential therapeutic target or future diagnostic marker? International Journal of Hypertension, 2019, 3159283. 10.1155/2019/3159283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci M, Quatraro C, Frassanito MA, & Silvestris F (2006). Deregulated expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in arterial hypertension: Role in endothelial inflammation and atheromasia. Journal of Hypertension, 24, 1307–1318. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000234111.31239.c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst EPC, Döring Y, & Weber C (2015). MIF and CXCL12 in cardiovascular disease: Functional differences and similarities. Frontiers in Immunology, 6, 373. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J-M, Huang A-F, Xu W-D, & Su L-C (2019). Insights into IL-29: Emerging role in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 23, 7926–7932. 10.1111/jcmm.14697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington R, Watson W, Kim HL, & Antonetti FR (2011). An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology, 7, S1. 10.1186/1710-1492-7-S1-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S-G, Zhang Z-H, Yu Y, Weiss RM, & Felder RB (2012). Central actions of the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 contribute to neurohumoral excitation in heart failure rats. Hypertension, 59, 991–998. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.188086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr., Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr., . . . Wright JT Jr. (2018). 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension, 71, 1269–1324. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Zhu B, Zhu Q, Tursun D, Liu S, Liu S, Hu J, & Li N (2019). Study on serum Pentrazin-3 levels in vasculitis with hypertension. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research, 39, 522–530. 10.1089/jir.2018.0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, & Crowley SD (2015). Role of T lymphocytes in hypertension. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 21, 14–19. 10.1016/j.coph.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.