Abstract

Background

Persons living with dementia (PLWD) experience high rates of hospitalization and re-hospitalization, exposing them to added risk for adverse outcomes including delirium, hastened cognitive decline, and death. Hospitalizations can also increase family caregiver strain. Despite disparities in care quality surrounding hospitalizations for PLWD, and evidence suggesting that exposure to neighborhood-level disadvantage increases these inequities, experiences with hospitalization among PLWD and family caregivers exposed to greater levels of neighborhood disadvantage are poorly understood. This study examined family caregiver perspectives and experiences of hospitalizations among PLWD in the context of high neighborhood-level disadvantage.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Stakeholders Understanding of Prevention Protection and Opportunities to Reduce HospiTalizations (SUPPORT) study, an in-depth, muti-site qualitative study examining hospitalization and re-hospitalization of PLWD in the context of high neighborhood disadvantage, to identify caregiver perspectives and experiences of in-hospital care. Data were analyzed using Rapid Identification of Themes; duplicate transcript review was used to enhance rigor.

Results

Data from N=54 individuals (47 individual interviews, 2 focus groups with 7 individuals) were analyzed. Sixty-three percent of participants identified as Black/African American, 35% as Non-Hispanic White, and 2% declined to report. Caregivers’ experiences were largely characterized by PLWD receiving sub-optimal care that caregivers viewed as influenced by system pressures and inadequate workforce competencies, leading to communication breakdowns and strain. Caregivers described poor collaboration between clinicians and caregivers with regards to in-hospital care delivery, including transitional care. Caregivers also highlighted the lack of person-focused care and exclusion of the PLWD from care.

Conclusions

Caregiver perspectives highlight opportunities for improving hospital care for PLWD in the context of neighborhood disadvantage and recognition of broader issues in care structure that limit their capacity to be actively involved in care. Further work should examine and develop strategies to improve caregiver integration during hospitalizations across diverse contexts.

Keywords: Disparities, Caregivers, Dementia, Hospitalizations

INTRODUCTION

Although hospitalization carries considerable risk of harm (including accelerated cognitive and functional decline) for persons living with dementia (PLWD), these events remain common, with PLWD experiencing at least a 40% greater risk of being hospitalized compared to other older adults.1-8 In-hospital care systems and environments are generally not optimized to provide dementia-specific care, leading to hospitalized PLWD frequently experiencing traumatic disruptions in familiar routines and environments which increases strain among family caregivers.9,10

First-hand perspectives from PLWD and family caregivers are necessary to understand factors that shape experiences with in-hospital care.9 Prior work suggests that caregivers identify multiple opportunities to improve hospital care for PLWD, including ensuring adequate staff training, providing increased support with personal care tasks, and consistently delivering person-directed care.5

However, the experiences of individuals who are exposed to high levels of neighborhood disadvantage (i.e., areas lacking key socioeconomic supports) are under-examined, despite individuals experiencing a disproportionate incidence and burden of dementia within these contexts.10-15 While it is unclear whether the perspectives of individuals exposed to high neighborhood-level disadvantage- which shapes opportunities and sites of care- are context-specific or represent more universal experiences, their under-inclusion in prior research is a significant gap. Neighborhood-level disadvantage has been strongly associated with adverse hospitalization outcomes (including increased re-admission risk, in-hospital mortality, and costs) across a number of conditions.16-21 Among PLWD, residing within a highly disadvantaged region is associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission, which may exacerbate the health and financial burdens faced by some PLWD and caregivers.22 Insights from caregivers living in under-resourced neighborhoods are important for informing our understanding of barriers to optimal in-hospital care for PLWD. These perspectives can also highlight the unique resources and strengths within these contexts.

To better understand in-hospital care delivery for PLWD in the context of high neighborhood disadvantage, we examined family caregiver perspectives of in-hospital care for PLWD residing within highly disadvantaged regions.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the Stakeholders Understanding of Prevention Protection and Opportunities to Reduce HospiTalizations (SUPPORT) study to explore caregiver perspectives of in-hospital care for PLWD. The SUPPORT study is an intensive, multi-site qualitative study designed to examine caregiver, community, and hospital provider perspectives regarding risks and protective factors surrounding hospitalizations and re-hospitalizations. Details of the study protocol and arms have been previously published.23 This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board, with verbal informed consent obtained prior to interviews. Methods and results followed the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) (Supplementary Table S1).24

Family caregivers (individuals providing unpaid care to a family or friend) participated in in-depth interviews or focus groups eliciting their overall caregiving experiences, experiences with hospitalization/rehospitalization, and protective resources. The current analysis focused on perspectives surrounding in-hospital care.

Study setting and participants

The SUPPORT study engaged a tiered sampling strategy to purposefully sample and recruit participants residing in areas with high neighborhood-level disadvantage and higher regional rehospitalization rates. An area of high neighborhood-level disadvantage was identified as the top 20th percentile of the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), a validated geospatial measure of neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage.25 Our highly-focused recruitment strategy targeted contacts with hospitals and community programs located within two metropolitan cities that serve highly-concentrated areas of high neighborhood-level disadvantage (and very few neighborhoods with low disadvantage) using precise ADI criteria. Self-reported financial security and racial/ethnic identity were also collected. Inclusion criteria for caregivers included: 1) current or prior experience providing unpaid care at least monthly to a PLWD and 2) conversational English ability. Participants received a $35 honorarium.

Interview procedures

Members of the study team (LB, QC, AGB) with formal training and prior experience in qualitative interviewing conducted interviews (in-person/phone) and focus groups (in-person only) between March 2019 and January 2020. Consistent with strategies to establish rapport and to not introduce bias (as participants may not interpret their lived experiences through the lens of the ADI), interviewers were sensitive to not probe about or ask participants to explicitly reflect on neighborhood disadvantage. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and de-identified prior to analysis.

Analysis

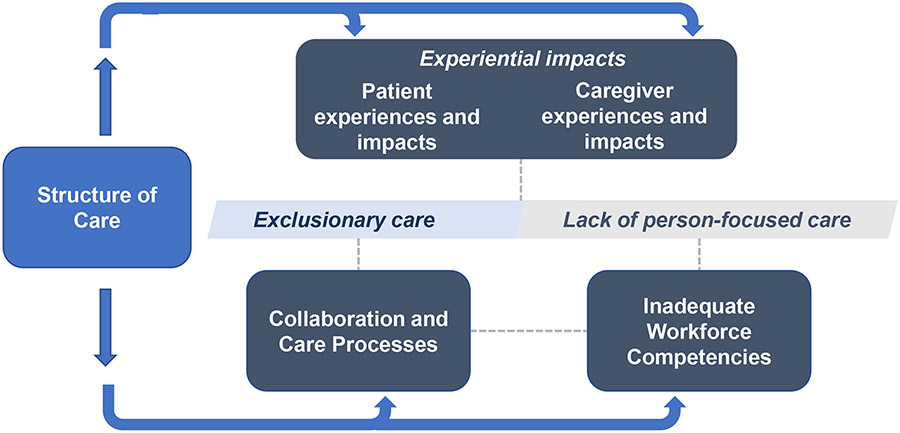

Analysis took place between November 2021 and December 2022. We analyzed all data related to caregivers’ descriptions of hospitalizations and in-hospital care (including transitional care planning) using the Rapid Identification of Themes approach.26,27 Initial themes were identified through a review of interview transcripts by all authors without the use of an existing framework. We resolved discrepancies through team-based discussion and data review, and developed an analytic summary of themes by incorporating input from all authors (Figure 1). To strengthen rigor and corroborate the accuracy of themes, several authors (BPG, AW, FK) iteratively reviewed transcripts to comprehensively examine areas of variation or disagreement from our thematic categories, and modified description and organization of themes in response to conflicting or inconsistent data.

Figure 1:

Overview of study findings

RESULTS

Forty-seven individual interviews and two focus groups (7 participants total) were conducted. Interviews lasted 31 to 129 minutes (mean 64, SD: 22) and focus groups lasted 64 to 70 minutes (mean 67, SD: 4). The self-identified race and ethnic composition of participants was 63% Black/African American, 35% White Non-Hispanic, and 2% unreported (Table 1). Most caregivers (91%) identified as female.

Table 1:

Caregiver Demographics (N=54)

| Interview Format | |

| Individual Interviews | 47 (87%) |

| Focus Groups | 7 (13%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4 (7%) |

| Female | 49 (91%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) |

| Race | |

| White Non-Hispanic | 19 (35%) |

| Black or African American | 34 (63%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) |

| Age Range | |

| 18-44 years old | 7 (13%) |

| 45-64 years old | 17 (31%) |

| 65 years or older | 29 (54%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) |

| PLWD relationship to caregiver | |

| Spouse | 1 (2%) |

| Parent | 21 (39%) |

| Grandparent or great-grandparent | 3 (6%) |

| Multiple individuals | 6 (11%) |

| Other* | 6 (11%) |

| Not reported | 14 (26%) |

| Educational background | |

| High School Diploma or Equivalent | 4 (7%) |

| Technical School, Vocational Training, Community College | 12 (22%) |

| Some College | 2 (4%) |

| 4-Year College | 13 (24%) |

| Post-College | 21 (39%) |

| Unknown | 2 (4%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single, never married | 20 (37%) |

| Married, or domestic partnership | 21 (39%) |

| Widowed | 5 (9%) |

| Divorced | 7 (13%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) |

| Occupation Status | |

| Full-time | 15 (28%) |

| Part-time | 11 (20%) |

| Not working | 3 (6%) |

| Retired | 23 (43%) |

| Unknown | 2 (4%) |

| Finances | |

| Things could be a lot better, I worry almost every day | 7 (13%) |

| Things are okay, but I worry often | 4 (7%) |

| Things are good, but I worry a couple times a month | 14 (26%) |

| Things are really good, I have no worries | 11 (20%) |

| Unknown | 18 (33%) |

Includes caregivers caring for step-parents, aunts/uncles, siblings, adult children, and friends.

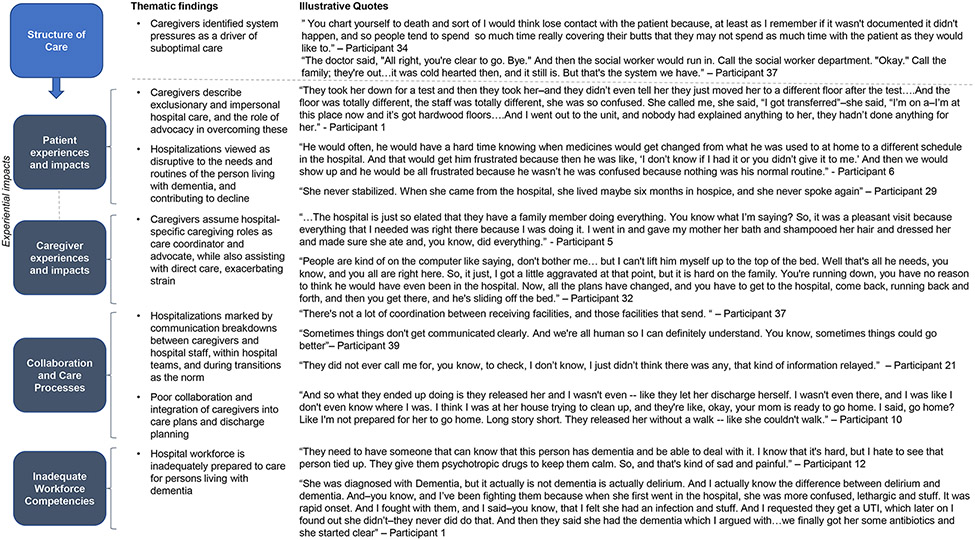

Overall study findings highlight caregivers’ primarily negative experiences with in-hospital care. Relationships between cross-cutting themes are displayed in Figure 1. Caregivers described the impact of inadequate hospital care for both themselves and the PLWD, linking this poor care to system pressures, inadequate workforce competencies, communication breakdowns, and a lack of person-centered care. Specific thematic findings and representative quotes are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Thematic findings and illustrative quotes

Structure of Care

Caregivers identified system pressures as a driver of suboptimal care

Caregivers highlighted numerous structural factors with negative impacts on hospitalization experiences for PLWD and caregivers including inadequate staffing, overburdened staff, and financial pressures. Caregivers perceived that inconsistent and inadequate hospital staffing reflected system-level financial considerations and constraints. Caregivers also perceived that clinical decision-making (including discharge timelines) were driven by financial or other system-level factors. One individual (Participant 41) observed, “There's not enough people. And it always relates to money. Nobody wants to pay.”

Caregivers observed that system-level factors influenced interpersonal interactions between clinicians, caregivers, and patients. Caregivers described that physicians were not well engaged with patients or caregivers due to competing responsibilities, and that most communication came from nursing. No caregivers described positive, systematic strategies for ensuring consistent communication and engagement of caregivers during hospitalizations. Caregivers perceived hospital clinicians as transient, interchangeable figures who did not generally know the patient well. Caregivers also described staff as being pre-occupied with required tasks (e.g., charting). One caregiver (Participant 33) commented, “at the hospital, it was just a job to them…. some just don't care or [are] there for a paycheck.”

Caregivers perceived that in-hospital care quality varied across different health systems and regions, and that the availability and quality of care received by PLWD was tied to their geography and insurance coverage. One caregiver observed, “The care that he got at the VA was absolutely inept” (Participant 16). Another caregiver (Participant 22) observed that higher resource settings provided more optimal care: “I do see a difference …it was just that much more information, that much more knowledge, that much more people that were able to communicate with, you know, the different teams.” One participant (Participant 4) felt that hospital systems in certain geographies preferentially kept patients admitted based on insurance coverage: “Hospitals, unfortunately, here in [county], they never keep people very long, especially if, you know, you have Medicaid and what not. It's like you only get paid for so many days and you only get paid so much per patient. So, you know, let's get those in that have Blue Cross Blue Shield, you know?”

Patient Experiences and Impacts

Caregivers describe exclusionary and impersonal hospital care, and the role of advocacy in overcoming these

Caregivers observed that hospitalized PLWD were frequently excluded or under-included in their own care and identified clinician behaviors that contributed to this dynamic. One caregiver (Participant 17) recalled, “Would they [clinicians] listen? I would say 90% of them did not…She [PLWD] is still a human being …who deserved to be treated and be able to be asked questions of herself. Especially if they’re trying to assess pain or say does this hurt.” One participant recalled that clinicians “treated him [PLWD] like a child” (FG 5, Participant 1). Another (Participant 37) described their mother not being incorporated into discharge planning: “My mother got so angry…I think she reamed them a new one until they said, ‘Okay…we won’t ship her out.’” One caregiver (Participant 44) perceived that disposition planning could seem punitive: “When she was in the hospital, she then got a little aggravated with the nurses. So, I think… to punish her, they sent her over to a nursing home.”

Caregivers readily identified strategies to better incorporate PLWD into their care. One recommendation was to have someone at bedside to facilitate patient comprehension and advocacy. One caregiver observed that hospitalized PLWD “need an advocate…they need someone to go to bat for them” (Participant 5). Others suggested it could be helpful for clinicians to incorporate details about the patient's identity (i.e., professional background) into patient-clinician interactions.

Hospitalizations viewed as disruptive to the needs and routines of the person living with dementia, and contributing to decline

Caregivers’ perspectives of hospitalizations were characterized by witnessing disruptive and distressing changes experienced by PLWD in the hospital. Some caregivers described PLWD experiencing more frequent hospitalizations and transitions of care, with one participant recalling that their family member “was yo-yoing” between nursing facilities and hospitals (Participant 40). Caregivers perceived disruptions of regular routines (e.g., home medication timing, sleep-wake cycles) as being driven by systems-level factors, such as hospital formularies or staffing constraints. One caregiver observed, “Getting her medications straight was difficult. We had had her on Aricept…well, the hospital had to get that in because it wasn’t something they were carrying… that caused a disturbance or a break in the continuity of her care” (Participant 29).

Caregivers perceived hospitalizations as transition points in the independence and wellbeing of PLWD. One caregiver said that “mental wise [the hospitalization] seemed like [it] was the demise” (Participant 31). Other caregivers described a functional decline and the need for a higher level of care after discharge. One recalled, “When she stayed there [hospital] for a month, then she couldn’t walk anymore. They had to go to rehab. I think that if they had gave her rehab while she was in the hospital, she wouldn’t have gotten to the point where she couldn’t walk” (Participant 33).

Participants also recognized that some PLWD unfortunately never regained their pre-hospitalization degree of health or quality of life. Given the negative impacts of hospitalizations, one participant observed that, “I have come to the decision that keeping them out of the hospital is the most important thing you can do… Because almost every time either one of them went into the hospital, they came out worse” (Participant 8).

Caregiver Experiences and Impacts

Caregivers assume hospital-specific caregiving roles as care coordinator and advocate, while also assisting with direct care, exacerbating strain

A commonly reported contributor to caregiver stress was the perceived addition of work and responsibilities throughout a hospitalization. Caregivers described feeling stress and overwhelmed by the task of preventing errors and serving as an advocate for the PLWD. Caregivers also described assisting with care tasks (e.g., bathing, toileting) to offset care burden on hospital staff. One caregiver recalled, “I would go [to the hospital] and help … do what I could. … you know, cleaning her up and making the bed” (Participant 23). Caregivers described challenges balancing caregiving tasks inside and outside of the hospital, including preparing home environments for discharge and touring skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). One explained, “I was trying to do double duty. I was trying to -- it was really dreadful -- take care of my own household and, you know, try to figure out when I was going to start work, be there, because the hospital I didn't trust.” (Participant 10).

Caregivers described difficulty taking care of themselves while fulfilling caregiving roles during hospitalization. One participant observed, “Everything else went by the wayside …housework didn’t get done, nothing got done” (Participant 1). Caregivers felt that staff acknowledgment and validation of caregiver contributions could be beneficial for strain: “When it comes to your own caregiving, and your own family, life is a little different, you know? Emotions get in the way…you just want to be reassured you’re doing the right thing” (Participant 21). Another participant observed that staff “seldom… ask me did I want a cup of water or did I want—you know, a juice or something. And that has been so rewarding, so heartwarming for anyone to even ask that” (Participant 39).

Some caregivers relied on their caregiving network to alternate caregivers present at bedside. A small number of participants described hospitalizations as facilitating greater support or a higher level of care for PLWD after discharge, potentially reducing caregiver strain. One caregiver (Participant 16) observed, “I was getting to the breaking point where I literally could not do this anymore…Having that decision [to not discharge home] taken off my shoulders…was just the biggest godsend.” Some caregivers were prompted to seek more support by hospital clinicians, with one recalling that “The nurse is the one that told me that. She said, ‘You’re going to have to get her 24-hour care’” (Participant 20).

Collaboration and Care Processes

Hospitalizations marked by communication breakdowns between caregivers and hospital staff, within hospital teams, and during transitions as the norm

Caregivers identified multiple points where communication breakdowns and information loss occurred in the context of a hospitalization, including 1) between caregivers and hospital staff, 2) within hospital care teams, and 3) during care transitions (e.g., between hospitals and SNFs). One caregiver described being asked repetitive questions by hospital staff, stating “you keep answering the same questions over and over again to different people… are you all not communicating?” (Participant 32).

Caregivers shared instances in which they felt clinicians failed to communicate with them or ignored their expertise. One caregiver recalled, “the staff did not tell me that he had been transported to the hospital…I kept wondering what’s going on, I didn’t even know he was in the hospital for hours” (Participant 31). Other participants expressed frustration that clinicians did not proactively communicate with caregivers. One caregiver (Participant 12) reflected, “You’re trying to explain to that doctor they have dementia, and that doctor is talking to them and ignoring the caregiver, then when something happens, then they want to pay attention to the caregiver.”

Caregivers felt that improved communication between hospital teams and caregivers could improve in-hospital care. The lack of a “universal health record” led to caregivers’ needing to “take control” to ensure that information was not lost during care transitions. The same participant commented, “Why isn’t that recorded in Epic for dementia patients so that people can understand some of the behaviors that that person has and what they can do to make it easier for staff to work with that person” (FG 5, Participant 1).

Poor collaboration and integration of caregivers into care plans and discharge planning

Caregivers described challenges collaborating with hospital care teams during hospitalizations. One caregiver said that it could be difficult for caregivers to navigate working with hospital staff, balancing how to “be present but not interfering…I've seen a lot of families just be nasty and that doesn’t help” (Participant 8). Caregivers described being poorly integrated into discharge planning, causing them to feel unprepared and rushed. One caregiver recalled, “You’re not giving us a heads up at least so we would know where she’s going, when she’s going” (Participant 37). Some caregivers felt that factors such as financial concerns (as opposed to patient or caregiver readiness) may drive discharge timelines.

Caregivers perceived that there were missed opportunities for reciprocal learning between caregivers and clinicians. One caregiver observed:

“Be sure you're talking to the families. Let them, you know, if you're frustrated with something and you're handling it a certain way and you learn that way, tell the family. …Because if you're having problems with it, the family is definitely going to be having problems with it.”

– Participant 21

Among the relatively few caregivers who had neutral or positive experiences during hospitalizations, caregivers frequently mentioned that they had professional experience within healthcare. Caregivers with neutral or positive experiences in-hospital care often did not provide specific or elaborate detail regarding what made care experiences positive: “The hospital stay, I’d say was fine…the care in the hospital was just the care in the hospital” (Participant 22). A few mentioned effective communication, with one caregiver (Participant 17) recalling their mother “had a fantastic surgeon who got it, who understood, who tried to talk to her and what not.”

Inadequate Workforce Competencies

Hospital workforce is inadequately prepared to care for persons living with dementia

Caregivers expressed concern that hospital staff lack dementia-specific competencies around functional needs, acute cognitive changes, and behavioral symptoms. One participant observed that hospital clinicians “don’t really cater to memory problems…just basically physical problems” (Participant 28). Caregivers felt that clinicians used approaches that were inappropriate for PLWD, such as assessing pain with numeric severity scales. Caregivers also felt that hospital staff were unable to consistently meet the care needs of PLWD, specifically with tasks such as toileting and bathing.

Another domain highlighted across multiple caregivers was a lack of attention to cognitive changes among hospitalized PLWD. Caregivers felt that staff struggled to identify acute symptoms of confusion, and described sub-optimal delirium prevention and management approaches. Caregivers described potentially avoidable and unnecessary use of chemical and pharmacologic restraints to handle behavioral symptoms. One participant recalled, “they put him in restraints. And you know, he pulled so hard against the restraints that his wrists were all bruised up and down.” (Participant 8). Caregivers also described PLWD receiving potentially inappropriate medications: “When my mom goes in the hospital…I don't want you to give her Ativan, that's probably just going to make it worse” (Participant 1).

Caregivers indicated additional in-hospital geriatrics expertise could be beneficial. One caregiver identified having “a geriatric doctor there and a doctor that was certified and trained in dementia and Alzheimer's behaviors” (Participant 12) as a strategy for improving in-hospital care. Caregivers contrasted the perceived inadequate training in dementia care among the hospital workforce with that of outpatient clinicians, who they felt benefit from additional geriatrics training in addition to longitudinal relationships with patients.

DISCUSSION

First-hand perspectives from caregivers are critical to understanding in-hospital care delivery for PLWD. In this study, we found that caregivers exposed to high neighborhood-level disadvantage perceived a pervasive lack of person-focused care and exclusion of the PLWD from their own care during hospitalizations. Caregivers also identified care practices and structural factors that shaped negative hospitalization experiences, many of which could be modified through improved caregiver integration during hospitalizations. One novel finding with regards to caregiver perceptions of hospitalizations was the observation that the ability of PLWD to access hospital care across different regions or health systems influenced the quality of in-hospital care received.5

Education and income are noted as important contributors in shaping healthcare access and navigation of healthcare services including hospitalizations, yet our findings do not reflect this. Caregivers did not generally perceive benefits based on social characteristics that are traditionally viewed as providing protective capacity to care recipients and caregivers with when utilizing health care services, despite some caregivers having high educational attainment or reporting financial security. Our findings corroborate other studies especially from racial and ethnic populations who describe structural failures within health care systems.28 Globally, our findings underscore the importance of the hospital and broader community environments as a target for intervention.

Caregivers described being poorly integrated into discharge planning. Effective communication surrounding care transitions may improve post-hospitalization outcomes, including decreasing risk of unplanned readmission.29 Neighborhood-level factors may hold implications for transitional care education and caregiver support surrounding hospitalizations. Community-dwelling PLWD residing in areas of high neighborhood-level disadvantage are less likely to discharge to a SNF following hospitalization.30 Family caregivers provide considerable unpaid effort within SNFs, and these hardships may be experienced differently by caregivers across differing contexts.31 Disparities may be exacerbated by documented discrepancies in caregiver training surrounding care transitions, with prior research demonstrating that caregivers who are Black, experiencing financial hardship, or caring for a Black, female, or Medicaid-enrolled patient are less likely to receive adequate training.15 Initiatives to improve caregiver inclusion (such as standardized caregiver discharge assessments) may strengthen caregiver-clinician collaboration and potentially mitigate some of these documented disparities.

Our findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting poor communication between clinicians and families in the hospital, which may in turn contribute to sub-optimal care and caregiver strain.32 Prior work by Toye et al. exploring implementation of systematic conversations between hospital staff and dementia caregivers to support patient-centered care has demonstrated that such initiatives must be tailored to specific clinical contexts based on stakeholder input.33 Findings from this study suggest that broader systematic reform (such as interventions tailored to transitions of care) are also essential to improve communication and collaboration between caregivers and clinical teams.

Initiatives such as Age-Friendly Health Systems, Acute Care for the Elders units, and the Hospital Elder Life Program represent important efforts that, if more broadly implemented and sustained, could improve dementia-specific hospital competencies.34-36 Our finding that caregivers perceive hospital environments lacking in dementia-friendly competencies is not new, but reinforces the critical need for ongoing care improvement.5 Given clinician difficulties distinguishing delirium and dementia, caregiver engagement models should be implemented more broadly to incorporate caregiver expertise in delirium identification.

There are limitations in our work. First, we performed interviews within two geographic regions, and findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Second, we only interviewed English-speaking participants. Third, while we purposefully recruited individuals exposed to high neighborhood-level disadvantage, our sample may not be representative of all individuals residing in such contexts. We recruited caregivers from contacts with formalized community services, which may introduce selection bias. Future studies should further examine the intersectionality between individual and neighborhood-level demographics with regards to dementia caregiving experiences, as well as understand unique sources of strength within areas that are appraised as having a high ADI.37 Finally, we did not specifically ask participants to reflect on neighborhood-level disadvantage and it is not possible to confirm whether experiences are unique or specific to this socio-contextual environment in the absence of a comparison group. Many of the challenges and care issues perceived by caregivers are well-described in other contexts, but the inclusion of diverse caregiver perspectives in this work is important.5,9,32,38,39

Our findings highlight opportunities to improve in-hospital care and integration of caregivers and PLWD in care processes. Many challenges during hospitalizations reflect broader issues in care structure, and interventions must continue to address these challenges in parallel.

Supplementary Material

S1. Interview Guide Questions Related to Hospitalization Events

S2. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): 32-item checklist

S3. Additional Information Regarding COREQ Checklist Items

Key Points

In this study of family caregivers of persons living with dementia (PLWD) who are exposed to high levels of neighborhood-level disadvantage, caregiver perspectives and experiences with hospitalization events were largely characterized by PLWD receiving sub-optimal care.

Caregivers viewed that sub-optimal hospital care was driven by system pressures and inadequate workforce competencies, leading to communication breakdowns and strain.

Caregivers also highlighted a lack of person-focused care and the exclusion of PLWD from involvement in their care.

Why does this paper matter?

Many of the factors contributing to adverse experiences during hospitalization events for patients living with dementia and their caregivers can be addressed through improved integration of caregivers into care delivery, although interventions must also continue to develop solutions for broader issues in care structures in parallel.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Sponsor's Role: The sponsor played no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis or preparation of this paper.

Funding Source:

This work is supported by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (PI Kind). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Prior Submissions: A preliminary version of this analysis was presented at the 2022 AGS Scientific Meeting.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudolph JL, Zanin NM, Jones RN, et al. Hospitalization in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer's disease: frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc. Aug 2010;58(8):1542–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02924.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fillenbaum G, Heyman A, Peterson B, Pieper C, Weiman AL. Frequency and duration of hospitalization of patients with AD based on Medicare data: CERAD XX. Neurology. Feb 8 2000;54(3):740–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.3.740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Langa KM, Kales HC. Predicting Risk of Potentially Preventable Hospitalization in Older Adults with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. Oct 2019;67(10):2077–2084. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oesterhus R, Dalen I, Bergland AK, Aarsland D, Kjosavik SR. Risk of Hospitalization in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Lewy Body Dementia: Time to and Length of Stay. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;74(4):1221–1230. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beardon S, Patel K, Davies B, Ward H. Informal carers' perspectives on the delivery of acute hospital care for patients with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. Jan 25 2018;18(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0710-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepherd H, Livingston G, Chan J, Sommerlad A. Hospitalisation rates and predictors in people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Jul 15 2019;17(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1369-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. Oct 15 2009;361(16):1529–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. Jan 11 2012;307(2):165–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Digby R, Lee S, Williams A. The experience of people with dementia and nurses in hospital: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. May 2017;26(9-10):1152–1171. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boltz M, Chippendale T, Resnick B, Galvin JE. Anxiety in family caregivers of hospitalized persons with dementia: contributing factors and responses. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Jul-Sep 2015;29(3):236–41. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke PJ, Weuve J, Barnes L, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Cognitive decline and the neighborhood environment. Ann Epidemiol. Nov 2015;25(11):849–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aranda MP, Kremer IN, Hinton L, et al. Impact of dementia: Health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jul 2021;69(7):1774–1783. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vassilaki M, Aakre JA, Castillo A, et al. Association of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. Jun 6 2022;doi: 10.1002/alz.12702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, et al. Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer's disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgdorf JG, Fabius CD, Riffin C, Wolff JL. Receipt of Posthospitalization Care Training Among Medicare Beneficiaries' Family Caregivers. JAMA Netw Open. Mar 1 2021;4(3):e211806. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson AE, Zhu J, Garrard W, et al. Area Deprivation Index and Cardiac Readmissions: Evaluating Risk-Prediction in an Electronic Health Record. J Am Heart Assoc. Jul 6 2021;10(13):e020466. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghirimoldi FM, Schmidt S, Simon RC, et al. Association of Socioeconomic Area Deprivation Index with Hospital Readmissions After Colon and Rectal Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. Mar 2021;25(3):795–808. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04754-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. Dec 2 2014;161(11):765–74. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michaels AD, Meneveau MO, Hawkins RB, Charles EJ, Mehaffey JH. Socioeconomic risk-adjustment with the Area Deprivation Index predicts surgical morbidity and cost. Surgery. Nov 2021;170(5):1495–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu J, Bartels CM, Rovin RA, Lamb LE, Kind AJH, Nerenz DR. Race, Ethnicity, Neighborhood Characteristics, and In-Hospital Coronavirus Disease-2019 Mortality. Med Care. Oct 1 2021;59(10):888–892. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arias F, Chen F, Fong TG, et al. Neighborhood-Level Social Disadvantage and Risk of Delirium Following Major Surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. Dec 2020;68(12):2863–2871. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Zuelsdorff M, Block L, et al. Disparities in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare enrollees with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. Mar 10 2023;doi: 10.1111/jgs.18311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Cotton Q, Morgan J, Block L. Diverse perspectives on hospitalisation events among people with dementia: protocol for a multisite qualitative study. BMJ Open. Feb 5 2021;11(2):e043016. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. Dec 2007;19(6):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible - The Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med. Jun 28 2018;378(26):2456–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neal JW, Neal ZP, VanDyke E, Kornbluh M. Expediting the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Evaluation:A Procedure for the Rapid Identification of Themes From Audio Recordings (RITA). American Journal of Evaluation. 2015;36(1):118–132. doi: 10.1177/1098214014536601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, Litchfield I, Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. Oct 8 2018;8(10):e019993. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander K, Oliver S, Bennett SG, et al. "Falling between the cracks": Experiences of Black dementia caregivers navigating U.S. health systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. Feb 2022;70(2):592–600. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. Apr 2016;176(4):484–93. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Temkin-Greener H, Yan D, Cai S. Post-acute care transitions and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with dementia: Associations with race/ethnicity and dual status. Health Serv Res. Feb 2023;58(1):164–173. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coe NB, Werner RM. Informal Caregivers Provide Considerable Front-Line Support In Residential Care Facilities And Nursing Homes. Health Aff (Millwood). Jan 2022;41(1):105–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurgens FJ, Clissett P, Gladman JR, Harwood RH. Why are family carers of people with dementia dissatisfied with general hospital care? A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. Sep 24 2012;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toye C, Slatyer S, Quested E, et al. Obtaining information from family caregivers to inform hospital care for people with dementia: A pilot study. Int J Older People Nurs. Mar 2019;14(1):e12219. doi: 10.1111/opn.12219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr., Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM Jr. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. Dec 2000;48(12):1697–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox MT, Sidani S, Persaud M, et al. Acute care for elders components of acute geriatric unit care: systematic descriptive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jun 2013;61(6):939–946. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers SE, Flood KL, Kuang QY, et al. The current landscape of Acute Care for Elders units in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. Oct 2022;70(10):3012–3020. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allan AC, Gamaldo AA, Wright RS, et al. Differential Associations Between the Area Deprivation Index and Measures of Physical Health for Older Black Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Feb 19 2023;78(2):253–263. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbac149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morandi A, Bellelli G. Delirium superimposed on dementia. Eur Geriatr Med. Feb 2020;11(1):53–62. doi: 10.1007/s41999-019-00261-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gwernan-Jones R, Abbott R, Lourida I, et al. The experiences of hospital staff who provide care for people living with dementia: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Older People Nurs. Dec 2020;15(4):e12325. doi: 10.1111/opn.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1. Interview Guide Questions Related to Hospitalization Events

S2. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): 32-item checklist

S3. Additional Information Regarding COREQ Checklist Items