Abstract

Purpose:

To develop and validate a novel patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure to assess vision-related functioning in individuals with severe peripheral field loss (PFL).

Design:

Prospective outcome measure development/validation study.

Methods:

A 127-item questionnaire was developed based on a prior qualitative interview study. 116 participants with severe PFL due to retinitis pigmentosa (RP) or glaucoma were recruited at the Kellogg Eye Center and completed the Likert-scaled telephone-administered questionnaire. Included participants had a horizontal extent of their visual field <20 degrees (RP) or a mixed or generalized Stage 4-5 defect using the Enhanced Glaucoma Staging System (glaucoma) in the better seeing eye (or one eye if fellow eye visual acuity was <20/200). Response data was analyzed using exploratory factor analysis and Rasch modeling. Poorly functioning items were eliminated, confirmatory factor analysis was used to ensure scale unidimensionality, and the model was refit to produce the final instrument.

Results:

The final LV-SCOPE Questionnaire contains 53 items across six domains: mobility, object localization, object recognition, reading, social functioning, and technology. There were 74 items removed due to high missingness, poor factor loadings, low internal consistency, high local dependency, low item information, item redundancy, or differential item functioning. Using Rasch item calibrations, person ability scores can be calculated for each of the six unidimensional LV-SCOPE domains with good test-retest stability.

Conclusions:

The LV-SCOPE Questionnaire provides a valid and reliable measure of vision-related functioning across six key domains relevant to individuals with severe PFL. Findings support the clinical utility of this psychometrically valid instrument.

Keywords: low vision, patient-reported outcomes, vision rehabilitation, Glaucoma, retinitis, pigmentosa, Rasch, item-response theory

Graphical Abstract

This paper reports the development and validation of the Low Vision Severely Constructed Peripheral Eyesight Questionnaire (LV-SCOPE) Questionnaire, a novel patient-reported outcome measure designed to measure vision-related functioning in individuals with severe peripheral field loss. The LV-SCOPE Questionnaire is valid and reliable measure of vision-related functioning across six key domains relevant to individuals with severe PFL and many facilitate measurement of vision-related functioning in this population in clinical practice and research.

Introduction

The number of people globally with vision impairment (VI) and blindness is projected to more than double between 2020 and 2050,1 largely due to population growth and aging. The economic, social, and health consequences of poor vision are vast. The global annual productivity loss attributable to VI and blindness is estimated at greater than $400 billion.2 Good vision is associated with greater educational attainment3 and financial success,4 while poor vision is associated with social isolation, depression, and a wide range of systemic health conditions,2,5 as well as impairments in daily functioning and independence.6,7

Vision rehabilitation may improve functioning and performance of daily activities in as many as 85% of patients with chronic VI who seek rehabilitation care.8,9 Commonly, vision rehabilitation includes provision of optical devices (e.g., magnifiers, closed-circuit televisions), occupational therapy to optimize the home environment, and/or orientation and mobility training. Patient reported outcome (PRO) measures are well suited to assess the effectiveness of vision rehabilitation, since by its nature vision rehabilitation aims to facilitate patient goals and improve vision-related functioning and quality of life.

To date, research and clinical innovation in vision rehabilitation has focused predominantly on impaired central vision, resulting from highly prevalent conditions like age-related macular degeneration. Just two randomized controlled trials have used PROs to test the effectiveness of vision rehabilitation for central vision loss resulting from macular disease,10,11 and existing PROs in low vision have variable psychometric properties.12 There is even less evidence about the effectiveness of vision rehabilitation for peripheral field loss (PFL).13,14 However, among those presenting for vision rehabilitation services an estimated 14-21% of individuals have a condition that commonly results in PFL, such as glaucoma or a retinal degeneration.15,16 To date, appropriate outcome measures have not been devised to carry out clinical trials and comparative effectiveness research on vision rehabilitation for PFL.

Numerous PRO and performance-based measures have been developed to assess vision-related performance and quality of life among individuals with glaucoma and RP, the two conditions that cause PFL that were considered in the current study. The Compressed Assessment of Ability Related to Vision is a brief test that measures task performance across key tasks that may be affected by glaucoma.17 Commonly used PROs like the Glaucoma Quality of Life-1518 and Glaucoma Quality of Life Questionnaire19 can be used to assess general vision-related quality of life in glaucoma. Additionally, Turano et al developed an extensive PRO to assess self-reported mobility in both glaucoma20 and RP;21 while this instrument offers a comprehensive assessment of the impact of vision on mobility, it does not treat other areas of performance or vision-related quality of life. The Michigan Retinal Degeneration Questionnaire (MRDQ) was developed and validated to measure various domains of visual function in those with inherited retinal degenerations, such as RP.22 In a newer approach to PRO administration, the Eye-tem bank project23 aims to develop disease-specific item banks for computer adaptive PRO administration in a variety of ophthalmic conditions, including glaucoma24,25 and inherited retinal degenerations.26 Reviews are available that provide a more complete overview of extant PRO measures for glaucoma27,28 and retinal diseases, including RP.29 Severe PFL is a feature of advanced disease in glaucoma and RP and existing glaucoma and retinal degeneration PROs have not specifically focused on the experience of those with severe PFL, despite its large impact on function and vision-related quality of life.

In the field of vision rehabilitation, most existing PROs were developed around the experiences of people with central vision loss. Accordingly, researchers have reported challenges, such as poor content validity and inadequate targeting of items when applying some of these outcome measures to those with severe PFL,30-35 despite evidence that severe PFL has a large negative impact on domains that are central to vision rehabilitation like mobility20,21,36overall vision-related quality of life,24,37,38 and task performance17,39,40

Existing disease specific PROs for glaucoma and RP are not adequately attentive to the challenges that individuals with severe PFL experience due to their vision loss,41 while general vision rehabilitation/low vision PROs suffer from a similar lack of applicability to this sizable population. We therefore aimed to develop an impairment specific PRO developed and validated for use among individuals with severe PFL from varied etiologies, such as glaucoma and RP

We previously reported on content development for the Low Vision Severely Constricted Peripheral Eyesight (LV-SCOPE) Questionnaire.41 The objective of LV-SCOPE is to fill an unmet need for a valid and reliable PRO to assess vision-related function in those with severe PFL. Developed around the lived experiences of individuals with severe PFL due to glaucoma and retinitis pigmentosa (RP), we report herein the psychometric validation of LV-SCOPE. The development of LV-SCOPE has followed best practices in PRO development, including Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)®42 and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines.43 Accordingly, the aim of this instrument is to facilitate measurement of vision-related function, which may be applicable to outcome measurement in clinical trials and comparative effectiveness research on vision rehabilitation for severe PFL.

Methods

This observational measurement development and validation study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent. This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Phase 1: Semi-structured interviewing

As previously reported,41 we conducted semi-structured interviews with 37 individuals with severe PFL due to glaucoma (n=18) and RP (n=19). Thematic content analysis and matrix analyses revealed six vision-related VR-QOL themes relevant across both glaucoma and RP, including: activity limitations, driving, emotional well-being, reading, mobility, and social function. While these themes have been reported in prior studies, the content of these themes (e.g., codes and categories)44 was distinct and reflected challenges that are unique to severe PFL.

Phase 2: Item selection and cognitive interviewing

We conducted a review of existing vision-related and general health-related functioning and quality of life instruments to identify PRO items that correspond to each code identified through qualitative analysis in Phase 1. When existing items were not identified for a given code, we generated novel items. All items were tested through cognitive interviewing with a minimum of five participants to ensure their intended meaning and that they were attentive to the qualitative issues that they were selected to address. In cases where item revisions were required based on cognitive interviews, these items were then retested. Cognitive interview participants were recruited from among those who had also participated in Phase 1.

Phase 3: Administration and validation

Participant recruitment and data collection

Participants were recruited from the Kellogg Eye Center at the University of Michigan. The same criteria used in Phase 1 were used to recruit participants in Phase 3. All participants were age ≥18 years and self-identified as having functional difficulty due to their vision loss.

Inclusion criteria for RP: RP diagnosed by a retina specialist and widest diameter on the III4e isopter of their Goldmann visual field ≤20 degrees in each eye (or one eye if the fellow eye visual acuity was <20/200);

Inclusion criteria for glaucoma: glaucoma diagnosed by a glaucoma specialist; reliable (<33% false-positives, false-negatives, and fixation losses) and repeatable defect on Humphrey 24-2 or 30-2 standard automated perimetry in the better seeing eye (defined by visual acuity), and classified as a mixed or generalized Stage 4 or Stage 5 defect using the Enhanced Glaucoma Staging System;45

Exclusion criteria: Mini-Mental State Exam score ≤23; diagnosed severe mental illness; or need for an English language interpreter.

Demographic information was obtained from participants and clinical data were obtained through chart review. Participants completed the following surveys in this order: i) Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (screening instrument for depression and anxiety); ii) National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25; and iii) the 127 LV-SCOPE pilot items. A subset of participants was re-contacted to retake the LV-SCOPE pilot questionnaire to assess test-retest reliability. The LV-SCOPE was administered with 5 response categories indicating level of difficulty due to vision (none, a little, a fair amount, a lot, cannot do this because of my vision). Respondents could also select “N/A (not applicable)” if the question was not relevant for non-visual reasons. All data were collected via telephone interview.

Data Analysis

Scale Dimensionality and Factor Analysis

Items with >25% missing responses and items with no responses in any one category were eliminated. We then examined correlations of each item using item-mean correlations (correlation with the mean of the remaining items) and partial item-item correlations (correlations of each pair of items controlling for the mean response). Items were eliminated if item-mean correlations were <0.5, which may indicate poor internal consistency, or if partial item-item correlations were >0.6, which may indicate local dependency. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to determine the factor structure, including the number of factors, and to examine factor loadings for each a priori hypothesized domain based on prior qualitative analysis.41 In cases where multiple factors were identified based on Velicer’s minimum average partial test46 or parallel analysis,47 scales were split if theoretically appropriate41 or items with low factor loadings (<0.5) were eliminated. The EFA was then rerun to confirm unidimensionality and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to confirm the fit of a single factor solution for each domain. The ratio of the first two eigenvalues, the percentage of variance explained by the first eigenvector, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were computed. A threshold of >0.9-0.95 is commonly used to indicate good model fit for CFI and TLI.48-50 Factor analysis was performed using the psych package51 in R (version 4.2.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Rasch Model

The Andrich rating scale approach to Rasch analysis52 was employed using the TAM package in R.53 Rasch models use categorical data to produce an objective measure of a latent trait. Items and respondents are quantified on the same scale, which remains valid in other contexts within the range targeted by the items. For comparison, we used a likelihood ratio test to compare the fit of the rating scale model to the partial credit model and we found that the less constrained partial credit model did not fit the data significantly better for any domain (p>0.05).

Person-item maps were examined to ensure appropriate targeting of items to the study sample. Expected item score curves and item response curves were used to examine spacing between response thresholds and the likelihood of respondents selecting different response categories, respectively. Since disordering of thresholds and low item information was noted for two interior response categories (“a little” and “a fair amount”) across domains, these were merged, leaving 4 response categories. Infit and outfit statistics were examined for all items. Items with values <0.5 may not be useful for measurement since their values are too predictable, whereas values >1.5 may denote randomness (e.g., noise or outliers) in the data.54 Items with values <0.5 or >1.5 were therefore eliminated. Dimensionality, threshold ordering, and item fit were then reconfirmed. To examine reliability, Rasch standard error-based, marginal, and person-separation reliability were computed for each domain.

Standardized residuals were computed for each response for each participant based on the estimated Rasch models. To assess residual dimensionality, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed and the largest eigenvalue was compared to the reference boundary of 2.O.55,56

Differential item functioning

We tested for differential item functioning (DIF) by fitting a faceted rating scale model that allowed for different item behavior in different prespecified groups. We separately investigated four covariates for DIF: diagnosis (glaucoma vs RP), gender (male vs female), education (no college degree vs college degree), and age (<70 vs ≥70 years). Statistical contrasts on parameters of the faceted model were used to assess scale invariance and item invariance to the covariate.

Person Scores/Abilities

Each individual’s visual disability was quantified by theta (θ), estimated from weighted least squares (t-score). Person scores for each scale were centered at 0 with variance dependent on item difficulty. We tested for floor and ceiling effects, which were considered present if >15% of respondents achieved the lowest or highest score possible, respectively.57

Domain and participant characteristic associations

The association between each pair of domains was quantified by Pearson’s correlation. Correlations between each domain and clinical covariates were assessed.

Test-retest reliability

Repeated administrations with 18 participants (median 11 weeks between tests) were used to assess test-retest stability. The mean difference between first and second administrations was used to quantify average change or drift; the Pearson correlation was used to measure relative association between measurements and the intraclass correlation (ICC) combined these into a single measure of agreement. An ICC of ∣0.7-0.9∣ is interpreted as “high” and > ∣0.9∣ is considered “very high”.58

Results

Following the item generation process described above, a pilot version of LV-SCOPE containing 127 items was administered to 116 study participants. Demographic characteristics of the full study sample are presented in Table 1. Approximately, 55% identified as female, 81% as White, 54% had a college degree or higher, and 58% were married.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 69 (59, 77) 1 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 64 (55.2) |

| Male | 52 (44.8) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 4 (3.4) |

| Black | 17 (14.7) |

| White | 94 (81.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 17 (14.7) |

| Married/partnered | 67 (57.8) |

| Separated/divorced | 17 (14.7) |

| Widowed | 16 (13.8) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 2 (1.7) |

| High school or equivalent | 23 (19.8) |

| Some college | 28 (24.1) |

| College degree | 36 (31.0) |

| Professional or graduate degree | 27 (23.3) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 11 (9.5) |

| Part-time | 5 (4.3) |

| Unemployed | 19 (16.4) |

| Retired | 71 (61.2) |

| Student | 1 (0.9) |

| Homemaker | 3 (2.6) |

| Other | 6 (5.2) |

presented as median (IQR), whereas categorical data are presented as counts and percentages IQR: Interquartile Range

Clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2. About 70% had a diagnosis of glaucoma and 30% had RP. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) visual acuity was 0.5 logMAR in both eyes (Snellen equivalent approximately 20/63; OD: 0.3-1.5, OS: 0.3-1.3). Of those who underwent HVF testing, the median (IQR) mean deviation (MD) was −21 (−27, −15) dB in right eyes and −21 (−25, −17) dB in left eyes; among those who underwent GVF testing, the median (IQR) horizontal extent of the visual field was 9 (5, 14) degrees in the right eye and 9 (6, 14) degrees in the left eye. More than half (58%) reported using some low vision assistive devices.

Table 2.

Participant clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| Glaucoma | 81 (69.8) |

| Retinitis pigmentosa | 35 (30.2) |

| Visual field type | |

| Kinetic (Goldmann) | 36 (31.0) |

| Standard automated perimetry | 70 (60.3) |

| None1 | 10 (8.6) |

| Chronic medical and psychiatric comorbidities | |

| Anxiety | 16 (13.8) |

| Depression | 20 (17.2) |

| Diabetes | 23 (19.8) |

| Heart disease | 16 (13.8) |

| Stroke | 7 (6.0) |

| Lung disease | 18 (15.5) |

| Vision rehabilitation experience | |

| Assistive device use | 67 (57.8) |

| Braille training | 15 (12.9) |

| Cane use | 35 (30.2) |

| Guide dog use | 2 (1.7) |

| Low vision therapy | 17 (14.7) |

| Occupational therapy | 16 (13.8) |

| Orientation and mobility training | 26 (22.4) |

| Visual function metrics | median (IQR) |

| Mean deviation, Db2 | |

| Right eye | −21 (−27, −15) |

| Left eye | −21 (−25, −17) |

| GVF maximum Horizontal extent, degrees2 | |

| Right eye | 9 (5, 14) |

| Left eye | 9 (6, 14) |

| Visual acuity, logMAR, median [IQR] | |

| Right eye | 0.5 (0.3, 1.5) |

| Left eye | 0.5 (0.3, 1.3) |

met study criteria based on visual acuity

Mean deviation based on participants who underwent standard automated perimetry (n=70) and maximum horizontal extent based on those who underwent kinetic perimetry (n=36) dB: decibels, GVF: Goldmann visual field, SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range

Psychometric analyses and item reduction

Scale Dimensionality, Factor Analysis, Model Fit and Differential Item Functioning

A total of 74 items were eliminated from the 127-item pilot instrument. These were eliminated due to high rate of missingness (e.g., not doing an activity for reasons other than vision), an empty response category, low factor loadings, low item-mean or high partial item-item correlations, extreme infit/outfit values, or item redundancy. Factor analysis identified six unidimensional domains: mobility (MO), object localization (OL), object recognition (OR), reading (RE), social functioning (SF), and technology (TE). The OL and OR domains were derived from an initial larger scale that contained these two factors. Items related to technology use were initially hypothesized to belong to the RE domain, however based on the results of the EFA, separate RE and TE domains were formed. Although issues related to driving were prominent in the qualitative phase of instrument development, too few respondents were still drivers, which led to elimination of all items related to driving. We performed an additional check on the dimensionality of each domain by performing Rasch analysis first, followed by a PCA of the residuals. The first Eigenvalues of the residuals was <2.0 for all domains, confirming their unidimensionality.55,56 Supplemental Table 1 presents results of the factor analyses based on retained items and the PCA of the residuals, demonstrating unidimensionality of each domain.

We tested for DIF by diagnosis, gender, education, and age. There was evidence of significant DIF by diagnosis for only a single item from the SF scale, which was eliminated. There was no DIF detected by gender, education, or age.

Reliability was high for all scales (Supplemental Table 2), though varied somewhat depending on the metric used to assess this. Rasch standard error-based reliability ranged from 0.85 (OL) to 0.96 (RE); marginal reliability ranged from 0.66 (SF) to 0.86 (RE); and the person-separation index ranged from 0.78 (TE) to 0.95 (RE).

Person Scores

As reported in Supplemental Table 3, standard deviations for person abilities ranged from 1.7 (OL) to 2.8 (SF). Floor and ceiling effects were minimal for each scale, ranging from 0% to 10%.

Domain-domain, demographic, and clinical correlations

Table 3 presents the correlations between each pair of the six domains. Domain-domain correlations were generally moderate to strong, ranging from 0.52 (MO-TE) to 0.89 (RE-TE). Correlations with the NEI-VFQ composite score were of a similar magnitude (−0.73 to −0.78), demonstrating convergent validity. LV-SCOPE domain scores were only weakly correlated with PHQ-4 scores (0.16 to 0.18), demonstrating discriminant validity. Correlations between domain scores and clinical variables (visual acuity, visual fields) were moderate, while there was a weak to null correlation with age (0.00 to −0.19).

Table 3.

Correlations of LV-SCOPE domains with each other and demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Mobility | Object localization |

Object recognition |

Reading | Social functioning |

Technology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domains | ||||||

| Mobility | --- | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.52 |

| Object localization | 0.77 | --- | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| Object recognition | 0.62 | 0.74 | --- | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| Reading | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.87 | --- | 0.78 | 0.89 |

| Social functioning | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.78 | --- | 0.75 |

| Technology | 0.52 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.75 | --- |

| Convergent Validity (NEI-VFQ-25) 1 | ||||||

| Composite score | −0.73 | −0.75 | −0.78 | −0.78 | −0.75 | −0.75 |

| Discriminant Validity (PHQ-4) | ||||||

| Score | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Visual acuity, logMAR | ||||||

| Better eye | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.58 |

| Worse eye | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

| SAP visual field mean deviation, decibels 1 | ||||||

| Better eye | −0.40 | −0.46 | −0.43 | −0.45 | −0.43 | −0.40 |

| Worse eye | −0.32 | −0.30 | −0.32 | −0.37 | −0.31 | −0.38 |

| Kinetic perimetry maximum horizontal extent, degrees 1 | ||||||

| Better eye | −0.26 | −0.31 | −0.41 | −0.39 | −0.47 | −0.36 |

| Worse eye | −0.33 | −0.34 | −0.45 | −0.41 | −0.48 | −0.38 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Age | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.12 | 0.02 |

NEI-VFQ: National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire, PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire, SAP: standard automated perimetry

These correlations are negative since LV-SCOPE measures disability and the NEI-VFQ and perimetric tests measure ability

Test-retest reliability

Test-retest reliability was assessed among 18 participants who completed the LV-SCOPE pilot questionnaire a second time after the initial administration (median 11 weeks later). The difference in scores from one administration to the next was not significantly different from zero for any of the six domains. The ICCs for the two administrations ranged from 0.70 (MO domain) to 0.87 (RE domain) and are presented in Supplemental Table 4.

LV-SCOPE Questionnaire

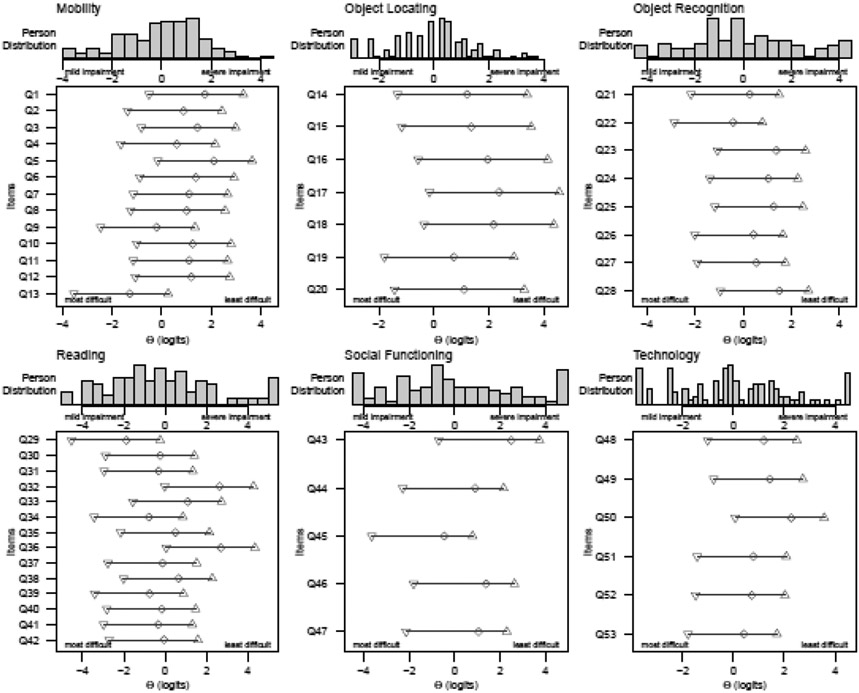

Figure 1 contains a person-item maps for each domain. The final instrument contains 53 items related to MO (13), OL (7), OR (8), RE (14), SF (5), and TE (6). Supplemental Table 5 contains the final LV-SCOPE items and the mean difficulty (ϴ) of each item. The full questionnaire (Supplemental Table 5) and a scoring worksheet using Rasch item calibrations are publicly available for use (http://osf.io/dj7xp).

Figure 1. Person-item maps for each LV-SCOPE domain.

The images illustrate the difficulty of each item relative to the person ability of the participants in the study sample. Item difficulties and person abilities are measured in logits. Items are numbered along the y-axis and correspond to the item numbers in the final instrument.

Discussion

The LV-SCOPE Questionnaire has strong psychometric properties and findings support the clinical utility of this instrument for assessing vision-related function among adults with severe PFL. This novel PRO, developed and validated among individuals with severe PFL, is needed to facilitate patient-centered vision rehabilitation in this sizable and growing population. In fact, as populations continue to grow and age in the U.S. and globally, the need for targeted vision rehabilitation for PFL is likely to increase concomitantly.2 To date, there is little clinical trial or comparative effectiveness data to guide the practice of vision rehabilitation practitioners working with this population.14 Future patient-centered research in the field may therefore be enabled by LV-SCOPE, which provides separate Rasch-calibrated scales across six key domains of vision-related function.

The six domains that comprise LV-SCOPE evolved from qualitative semi-structured interviews in which key themes relevant to this patient population were elicited. The findings from this qualitative study are described in detail in a prior publication.41 The final domains contained in LV-SCOPE were driven by theory and then refined after administering the pilot instrument and performing EFA on survey response data to evaluate the unidimensionality of each domain. This was done to ensure that domains have a strong theoretical foundation and that scores represent a single latent construct. Nonetheless, unidimensionality was further confirmed by the alternative approach of performing Rasch analysis followed by PCA.

The domain-to-domain correlations ranged from 0.52-0.89, similar to other validated instruments.59 The higher end domain-to-domain correlations (e.g., r=0.89 between RE-TE domains) indicate a similar impact of severe PFL on these constructs, though we do observe a difference in the magnitude of their correlation with better-eye visual acuity. Factor loadings and CFA model fit indices indicated that the domains we have reported each represent a unique dimension contributing to the measurement of vision-related functioning in severe PFL.

Items related to some of the themes identified in our qualitative study41 did not have adequate psychometric properties to be included in the final LV-SCOPE instrument. Specifically, in semi-structured interviews, participants often discussed difficulty driving and driving cessation. However, among participants in this validation study nearly all had ceased driving.

Notably, we identified very little DIF, which exists when groups (e.g., by gender, diagnosis, etc.) have different probabilities of a response when controlling for the overall domain score.60 Items displaying DIF are often eliminated in order to make the final instrument generalizable without sacrificing construct validity. In this study we assessed DIF after performing item reduction based on other psychometric criteria. We eliminated a single item for which there was evidence of DIF by diagnosis (glaucoma vs RP), but there was no evidence of DIF by gender, age, education, or diagnosis for any of the remaining items.

Reliability was high across domains. One exception was with the measure of marginal reliability for the SF scale (0.66), which was lower than Rasch standard error (0.91) and person separation index (0.86) measures for the same scale. Marginal reliability assumes less about the distribution of person scores and is thus lower than the model-based reliability estimate, possibly due to small floor (9.5%) and ceiling (10.3%) effects restricting the tails of the SF domain estimates. Test-retest reliability was also high (ICC >0.7) and given a shorter time frame between test administrations might improve even further.

Our study had a number of notable strengths. We followed best practices endorsed by regulatory agencies like the FDA,43,61 PROMIS®,62 and professional bodies63 in the development of PROs, including carrying out qualitative studies within the target population. We also used modern test theory (Rasch analysis) to validate LV-SCOPE. Prior PRO validation studies in low vision have used varied approaches and therefore have often reported less rigorously on the dimensionality and psychometric properties of instruments.12 Using Rasch analysis, item difficulties and person traits are scaled using the same metric; the spacing between response options is allowed to vary for each item; and scores are on an interval scale that enables the use of standard parametric statistical tests.

This study also had several limitations. Participants were, in general, highly educated, and non-Hispanic White. Thus, additional work is needed to confirm the generalizability of our findings and to compare item calibrations in more diverse populations. The sample size to assess retest reliability was small and further work should be done to establish this measurement property. While we performed a large number of validity tests in this study, other validation testing could be performed in future studies to explore further areas such as convergent, divergent, criterion, and content validity. The current study focused on individuals with glaucoma and RP, since these are common causes of severe PFL seen in vision rehabilitation practices.15,16 We did not study the performance of the LV-SCOPE questionnaire among those with other causes of severe PFL, such as a history of pan-retinal photocoagulation, stroke, or non-glaucomatous optic neuropathies. Future research should be done to validate the instrument in those populations. Additionally, studies are needed to assess the sensitivity of the LV-SCOPE questionnaire to change after patients undergo vision rehabilitation.

In summary, the LV-SCOPE Questionnaire is a novel PRO designed and validated among individuals with severe PFL due to glaucoma and RP. This instrument fills a gap in the literature and the PROs available to clinicians and researchers aiming to assess vision-related function in this sizable and growing population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements & Financial Disclosures

Funding/Support: This project was funded by a grant from the National Eye Institute to JRE (K23EY027848) and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the University of Michigan Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: JRE has consulted for MetLife.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):e888–e897. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques AP, et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020. The Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(4):e489–e551. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30488-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma X, Zhou Z, Yi H, et al. Effect of providing free glasses on children’s educational outcomes in China: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g5740. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy PA, Congdon N, Mackenzie G, et al. Effect of providing near glasses on productivity among rural Indian tea workers with presbyopia (PROSPER): a randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(9):e1019–e1027. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30329-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolli A, Seiler K, Kamdar N, et al. Longitudinal Associations Between Vision Impairment and the Incidence of Neuropsychiatric, Musculoskeletal, and Cardiometabolic Chronic Diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. Published online September 17, 2021:S0002-9394(21)00462–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrlich JR, Hu M, Zhou Y, Kai R, De Lott LB. Visual Difficulty, Race and Ethnicity, and Activity Limitation Trajectories Among Older Adults in the United States: Findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Published online January 16, 2022:gbab238. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenwick EK, Ong PG, Man REK, et al. Association of Vision Impairment and Major Eye Diseases With Mobility and Independence in a Chinese Population. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(10):1087–1093. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinds A, Sinclair A, Park J, Suttie A, Paterson H, Macdonald M. Impact of an interdisciplinary low vision service on the quality of life of low vision patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(11):1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leat SJ, Fryer A, Rumney NJ. Outcome of low vision aid provision: the effectiveness of a low vision clinic. Optom Vis Sci. 1994;71(3):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stelmack JA, Tang XC, Reda DJ, et al. Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial (LOVIT). Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(5):608–617. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stelmack JA, Tang XC, Wei Y, et al. Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial II (LOVIT II): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. Published online December 15, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vélez CM, Ramírez PB, Oviedo-Cáceres MDP, et al. Psychometric properties of scales for assessing the vision-related quality of life of people with low vision: a systematic review. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2022;0(0):1–10. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2022.2093919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binns AM, Bunce C, Dickinson C, et al. How effective is low vision service provision? A systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(1):34–65. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrlich JR, Spaeth GL, Carlozzi NE, Lee PP. Patient-Centered Outcome Measures to Assess Functioning in Randomized Controlled Trials of Low-Vision Rehabilitation: A Review. Patient. Published online August 5, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0189-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owsley C, McGwin G, Lee PP, Wasserman N, Searcey K. Characteristics of low-vision rehabilitation services in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(5):681–689. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein JE, Massof RW, Deremeik JT, et al. Baseline traits of low vision patients served by private outpatient clinical centers in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(8):1028–1037. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekici F, Loh R, Waisbourd M, et al. Relationships Between Measures of the Ability to Perform Vision-Related Activities, Vision-Related Quality of Life, and Clinical Findings in Patients With Glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(12):1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.3426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, Worton B, O’Brien C. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(2):139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burr JM, Kilonzo M, Vale L, Ryan M. Developing a preference-based Glaucoma Utility Index using a discrete choice experiment. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(8):797–808. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181339f30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turano KA, Rubin GS, Quigley HA. Mobility performance in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(12):2803–2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turano KA, Geruschat DR, Stahl JW, Massof RW. Perceived visual ability for independent mobility in persons with retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(5):865–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacy GD, Abalem MF, Andrews CA, et al. The Michigan Retinal Degeneration Questionnaire: A Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument for Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;222:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khadka J, Fenwick E, Lamoureux E, Pesudovs K. Methods to Develop the Eye-tem Bank to Measure Ophthalmic Quality of Life. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(12):1485–1494. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khadka J, McAlinden C, Craig JE, Fenwick EK, Lamoureux EL, Pesudovs K. Identifying content for the glaucoma-specific item bank to measure quality-of-life parameters. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(1):12–19. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318287ac11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pesudovs K, Khadka J, Fenwick E, Lamoureux E. Rasch analysis of the glaucoma-specific module of the Eye-tem Bank project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(15):5313–5313.23821194 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prem Senthil M, Khadka J, De Roach J, et al. Development and Psychometric Assessment of Novel Item Banks for Hereditary Retinal Diseases. Optom Vis Sci. 2019;96(1):27–34. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinokurtseva A, Quinn MP, Wai M, Leung V, Malvankar-Mehta M, Hutnik CML. Evaluating measurement properties of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in glaucoma: a systematic review. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. Published online May 2, 2023:S2589-4196(23)00077–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2023.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gazzard G, Kolko M, Iester M, Crabb DP, Educational Club of Ocular Surface and Glaucoma (ECOS-G) Members. A Scoping Review of Quality of Life Questionnaires in Glaucoma Patients. J Glaucoma. 2021;30(8):732–743. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prem Senthil M, Khadka J, Pesudovs K. Assessment of Patient-reported Outcomes in Retinal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Surv Ophthalmol. Published online January 3, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noe G, Ferraro J, Lamoureux E, Rait J, Keeffe JE. Associations between glaucomatous visual field loss and participation in activities of daily living. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2003;31(6):482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stelmack JA, Szlyk JP, Stelmack TR, et al. Psychometric properties of the Veterans Affairs Low-Vision Visual Functioning Questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(11):3919–3928. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haymes SA, Johnston AW, Heyes AD. The development of the Melbourne low-vision ADL index: a measure of vision disability. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(6):1215–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weih LM, Hassell JB, Keeffe J. Assessment of the impact of vision impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(4):927–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finger RP, Tellis B, Crewe J, Keeffe JE, Ayton LN, Guymer RH. Developing the impact of Vision Impairment-Very Low Vision (IVI-VLV) questionnaire as part of the LoVADA protocol. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(10):6150–6158. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stelmack JA, Stelmack TR, Massof RW. Measuring low-vision rehabilitation outcomes with the NEI VFQ-25. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(9):2859–2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turano KA, Broman AT, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Association of visual field loss and mobility performance in older adults: Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81(5):298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prem Senthil M, Khadka J, Pesudovs K. Seeing through their eyes: lived experiences of people with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye. Published online January 13, 2017. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chun YS, Sung KR, Park CK, et al. Factors influencing vision-related quality of life according to glaucoma severity. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(2):e216–e224. doi: 10.1111/aos.13918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhorade AM, Yom VH, Barco P, Wilson B, Gordon M, Carr D. On-road Driving Performance of Patients With Bilateral Moderate and Advanced Glaucoma. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;166:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Y, Lin C, Waisbourd M, et al. The Impact of Visual Field Clusters on Performance-Based Measures and Vision-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. Published online December 14, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lange R, Kumagai A, Weiss S, et al. Vision-related quality of life in adults with severe peripheral vision loss: a qualitative interview study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00281-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Group PC. PROMIS® instrument development and validation scientific standards version 2.0. HealthMeasures Website. Published online 2013. Accessed November 10, 2022. https://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/PROMISStandards_Vers2.0_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Published online December 2009. Accessed April 19, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/…/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf

- 44.Elliott V Thinking about the Coding Process in Qualitative Data Analysis. The Qualitative Report. 2018;23(11):2850–2861. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brusini P, Filacorda S. Enhanced Glaucoma Staging System (GSS 2) for classifying functional damage in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2006;15(1):40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velicer WF. Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika. 1976;41(3):321–327. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Humphreys LG, Montanelli RG Jr. An investigation of the parallel analysis criterion for determining the number of common factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1975;10(2):193–205. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. psychology press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Revelle WR. psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research. Published online 2017. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych Version = 2.2.5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen EB. The Rating Scale Model. In: van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK, eds. Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. Springer; 1997:67–84. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-2691-6_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robitzsch A, Kiefer T, Wu M, et al. Package ‘TAM.’ Test Analysis Modules–Version. Published online 2022:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright B, Linacre J. Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions. 1994;8(3):370. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fox TGB Christine M Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences, Second Edition. 2nd ed. Psychology Press; 2007. doi: 10.4324/9781410614575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hua C SW& Rasch Measurement Theory Analysis in R: Illustrations and Practical Guidance for Researchers and Practitioners. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://bookdown.org/chua/new_rasch_demo2/ [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bobak CA, Barr PJ, O’Malley AJ. Estimation of an inter-rater intra-class correlation coefficient that overcomes common assumption violations in the assessment of health measurement scales. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018;18(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0550-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamoureux EL, Pallant JF, Pesudovs K, Rees G, Hassell JB, Keeffe JE. The Impact of Vision Impairment Questionnaire: An Assessment of Its Domain Structure Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Rasch Analysis. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(3):1001–1006. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holland PW, Wainer H, eds. Differential Item Functioning. 1st edition. Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Varma R, Richman EA, Ferris FL, Bressler NM. Use of patient-reported outcomes in medical product development: a report from the 2009 NEI/FDA Clinical Trial Endpoints Symposium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(12):6095–6103. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Celia D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reeve BB, Wyrwich KW, Wu AW, et al. ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(8):1889–1905. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0344-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.