Abstract

Many college students, especially first-generation and underrepresented racial/ethnic minority students, desire courses and careers that emphasize helping people and society. Can instructors of introductory STEM courses promote motivation, performance, and equity in STEM fields by emphasizing the prosocial relevance of course material? We developed, implemented, and evaluated a prosocial utility-value intervention (UVI): a course assignment in which students were asked to reflect on the prosocial value of biology or chemistry course content; our focus was on reducing performance gaps between first-generation and continuing generation college students. In Studies 1a and 1b, we piloted two versions of a prosocial UVI in introductory biology (N = 282) and chemistry classes (N = 1705) to test whether we could encourage students to write about the prosocial value of course content. In Study 2, we tested a version of the UVI that combines personal and prosocial values, relative to a standard UVI, which emphasizes personal values, using a randomized controlled trial in an introductory chemistry course (N = 2,505), and examined effects on performance and motivation in the course. In Study 3, we tested the prosocial UVI against a standard UVI in an introductory biology course (N = 712). Results suggest that the prosocial UVI may be particularly effective in promoting motivation and performance for first-generation college students, especially those who are more confident that they can perform well in the class, reflecting a classic expectancy-value interaction. Mediation analyses suggest that this intervention worked by promoting interest in chemistry.

Keywords: intervention science, STEM pipeline, STEM diversity, expectancy-value theory, prosocial goals

Despite years of research and policy action to broaden participation in science fields, there remains a substantial gap between the needs of the scientific workforce and the number of qualified applicants (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018; National Science Board, 2019). Even when college students show initial interest in STEM fields (i.e., science, technology, engineering, and math), they drop out or change majors at high rates, especially after gateway or introductory science courses (Koch, 2017; Seymour & Hunter, 2019). Furthermore, the risk of attrition is not equally distributed. For example, first-generation college students (FG; those for whom no parent/guardian has a college degree) are particularly likely to leave science and engineering majors during college, as are students from racial/ethnic groups that are considered to be underrepresented minorities (URM) in STEM by the National Institutes of Health (e.g., Black, Latinx or Hispanic, and Native American individuals; Chang, et al., 2014; National Institutes of Health, 2019; Rosenzweig et al., 2020; Shaw & Barbuti, 2010). Because experiences in gateway courses are especially strong predictors of persistence in STEM (Flanders, 2017; Harris et al., 2020), there is an urgent need to reimagine the introductory science classroom experience in ways that appeal to a larger number of students (Asai et al., 2022; Thorp, 2022). In the studies reported here, we test new curricular interventions designed to make gateway courses more engaging for all students, with the potential to promote more equitable outcomes.

Our approach to intervention is based in expectancy-value theory, advanced by Eccles and Wigfield (2002), who theorized that students’ academic choices are a function of their subjective perceptions of task value and their expectations for success on a task. They emphasized the importance of specific task values – how an individual thinks about and perceives the value of a particular academic task or domain, e.g., a topic covered in class, a lecture, or a field of study. When a student expects to do well and values a task, they should exert more effort, perform better and persist. Expectancies and task values are theorized to positively interact such that students should be most motivated if they both value a task and believe that they can succeed.

Researchers have tested many hypotheses generated from this broad theory, providing a strong base of support for many aspects of the model (Wigfield & Eccles, 2020). Intervention scientists have focused on task values that might be amenable to intervention, with an emphasis on perceptions of utility value or relevance. A large body of research on personal relevance suggests that motivation and performance will be maximized when individuals see course material as useful or personally relevant (e.g., “understanding long and short muscles will help me exercise more efficiently;” Harackiewicz, Tibbetts et al, 2014; Wigfield & Eccles, 2020). Personal relevance is not limited to the self; tasks can be relevant or personally valued for their usefulness for other people (‘understanding photosynthesis is important for helping my mother in her garden”); the critical point is that the individual perceives this relevance connection as personally valuable. In addition, multiple theoretical frameworks, including expectancy-value theory (Eccles et al., 1983), identity-based motivation theory (Oyserman, 2007), and the relevance continuum framework (Priniski et al., 2018), posit that some types of relevance may be more powerful than others, particularly when relevance connections are associated with an individual’s sense of identity. We now consider the importance of a specific type of task value: prosocial utility value, or the perceived usefulness of course content for helping others.

The Power of Prosocial Utility Value

Many students have a strong desire to help other people. Individuals differ in the ways that they construe such prosocial goals; some students want to make the world a better place, others want to give back to their communities and families, and others may simply want to help people in general. Students are motivated to pursue courses and careers that are consistent with their values and goals (Diekman & Steinberg, 2013; Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), and STEM fields are a promising avenue to fulfilling prosocial motives as they have clear implications for public health, the planet, and the human condition. Yet, the STEM classroom experience can be discouraging, in part because introductory courses often emphasize technical and basic knowledge at the expense of real-world applications and larger “why it matters” explanations (e.g., Cech, 2014; Harper et al., 2019).

Personal relevance can be prosocial for many individuals. Helping students to see how STEM course topics are relevant to their prosocial goals (e.g., a task can be perceived as valuable because it can help a student achieve their goal of helping their parents, or for saving the planet) can make coursework more engaging, and stimulate motivation and performance. Moreover, if students make connections between course material and personal goals that are an important part of their identities, those utility-value connections could help students to see the material not just as personally valuable but as something they identify with, making the connections even more personally meaningful (e.g., “understanding diabetes is important for helping my parents, and important to my identity as a good son”; “understanding climate change is important for saving the planet, and I want to have a career in wildlife conservation”). This is significant because relevance connections that extend from personal usefulness into identification are more powerful, leading to higher levels of motivation, interest, and performance in that domain (Priniski et al., 2018).

Prosocial task value can be broad (e.g., a topic might be useful for helping society or people in general) or specific (e.g., course content might be useful for helping friends, family, or one’s community); the key is that the individual focuses on the value of course topics for helping others. Prosocial task value (a situational variable) is of course related to communal values (properties of the person), which are personally held values that include value for helping others, but also include valuing working with and forming bonds with others at a broader and more general level (Brown et al., 2015; Gray et al., 2022). Prosocial task value may also be related to other personal value systems, such as interdependence, which involves interdependent motives or ways of being (focusing on others and adjusting to the requirements of relationships; Stephens, Markus & Phillips, 2014). For example, individuals who endorse communal values or interdependent motives at a general level may be more likely to perceive some tasks as having prosocial utility value in a particular situation. In short, task values are more specific and situational than personal values and motives that transcend contexts, and prosocial task value is more narrowly defined around the utility of a task for helping others, whereas prosocial personal values may be embedded in systems of communal goals and interdependent motives that involve a wider range of values, navigation of interpersonal relationships, and ways of being.

Although all students, on average, may benefit from seeing the prosocial utility of what they are learning (Brown et al., 2015; Yeager et al., 2014), prosocial utility value may be more personally meaningful and more motivationally powerful for FG students and URM students, whose personal goals may include communal values and interdependent motives. These personal goals are likely to be deeply held, culturally based, and highly identity-relevant, and may lead students to appreciate the prosocial utility value of their science courses (Allen et al, 2015; Canning et al., 2014; Gibbs & Griffin, 2013; Harackiewicz, Smith, et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2014; Thoman et al., 2015). Specifically, FG students are likely to come from working class cultures that are characterized by “hard interdependence,” which includes an emphasis on supporting family and community to overcome shared difficulties (Stephens et al., 2014). For URM students, personal prosocial values may arise in reaction to discrimination and historical marginalization (Gray et al., 2022), which can lead individuals to place a greater value on equity, social justice, and helping others through their work (McGee & Bentley, 2017).1 For these students, prosocial task value might be particularly likely to develop into a deeper identity-based sense of task value, as suggested by the relevance continuum (Priniski et al., 2018).

Given that all students, and especially marginalized and underrepresented students are likely to desire courses and careers that emphasize prosocial values (Belanger et al., 2017; Thoman et al., 2015), it is critical that introductory science courses emphasize prosocial applications and that instructors help students find connections between content and their personally (and culturally) held prosocial goals. By intervening to highlight the prosocial value of topics in STEM courses, instructors could broaden participation in STEM for everyone, and especially appeal to FG and URM students. In the current project, we test interventions to promote perceptions of prosocial utility value in introductory science classes.

Interventions to Promote Perceived Prosocial Value in STEM

If science instructors can help students, and in particular FG and URM students, see course content as connected to their prosocial goals, they may become more motivated and perform better in gateway courses, develop a greater interest in STEM, and be more likely to pursue STEM majors and careers (Harackiewicz, Smith, et al., 2016). Harackiewicz and Priniski (2018) reviewed interventions developed to improve educational outcomes in higher education and identified three types of intervention: (a) task value interventions, which focus on how students think about what they are learning, (b) framing interventions, which target how students think about academic challenges and career choices, and (c) values affirmation interventions, which address how students think about themselves. These interventions are all student-centered and share some core features: all convey some information hypothesized to affect psychological processes and engage students in active reflection that often involves writing. Within each type of intervention, however, there are critical differences in their domain specificity and the academic outcomes they target. Some interventions target course-specific outcomes such as performance or interest in the topic, others target field-specific outcomes such as attitudes about STEM careers or STEM persistence, and others target college-general outcomes such as overall GPA or social belonging.

Although values affirmation and framing interventions have been used to help FG and URM students perform better in their college classes (Aronson et al., 2002; Brady et al., 2016; Covarrubias et al., 2018, Harackiewicz et al., 2014; Stephens et al., 2015), task value interventions may be particularly well suited for changing the way that students think about what they are learning in their courses or how they think about STEM fields and careers. In other words, this approach could be used for promoting perceptions of prosocial task value in STEM. For example, research using a task value approach at the field-specific level suggests that students’ perceptions of the prosocial value of STEM are malleable and linked to motivation and performance (Diekman et al., 2019). In laboratory studies, describing STEM careers as prosocial increased students’ interest and motivation to pursue science (Brown et al., 2015; Diekman et al., 2011). In a series of correlational, experimental, and longitudinal studies, Yeager and colleagues (2014) found that having students write testimonials about their self-transcendent purpose goals for learning (which were often prosocially focused) resulted in more effective self-regulation and higher STEM grades, especially among students with low prior performance.

In contrast, recent research using a task value approach at the course-specific level—the approach taken in the current research—has tested curricular interventions that provide students with opportunities to generate personal and/or prosocial connections between what they are learning and their own lives, using utility-value interventions (UVI). Grounded in expectancy-value theory (Eccles et al., 1983; Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), the UVI involves writing assignments, integrated into the curriculum as homework, designed to help students explore the personal usefulness (i.e., utility value) of course material (e.g., Gaspard et al., 2021; Harackiewicz, Canning, et al. 2016; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; Hulleman et al., 2010, 2017; Rosenzweig et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). Unlike other psychological interventions that target students’ general beliefs about learning or careers in a field, or STEM fields in general, a UVI focuses on a specific topic in a class, and it always emphasizes the usefulness of academic content, and how science topics are perceived. This is particularly relevant for stimulating engagement in course content and for promoting interest in a particular academic field, which is an important predictor of persistence in that field (Harackiewicz et al., 2008; Harackiewicz, Smith, et al., 2016).

In utility-value writing assignments, students summarize course material and discuss how it is personally relevant and useful in their own lives or the lives of close others (UVI condition), and these assignments are typically compared to a control condition in which students simply summarize course material (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2020). Although this intervention is not designed to target prosocial value specifically, the open-ended nature of the assignment (to connect the material to students’ own lives and the lives of close others) provides flexibility so that students can write about prosocial value if they so wish. Indeed, the assignments are specifically designed to give students autonomy to make connections to whatever is important to them, and thus students for whom prosocial goals are personally important may be particularly likely to write about the prosocial value of what they are learning.

Harackiewicz, Canning, and colleagues (2016) tested a UVI in an undergraduate introductory biology course and examined intervention effects on course performance as a function of race and generational status. The UVI was effective for all students, on average, and it was particularly effective for first-generation, underrepresented minority (FG-URM) students, increasing their grades in the biology course by about half a grade point (Harackiewicz, Canning et al., 2016). Baseline analyses suggested that FG-URM students were especially motivated by a desire to use their education to help their families and communities (cf., Jackson et al., 2016). Linguistic analyses of students’ essays revealed that all students, on average, and FG-URM students in particular, wrote longer essays in the UVI condition than their counterparts in the control condition (an indicator of increased engagement with the assignments), and their essays were more likely to contain family and social themes. In other words, FG-URM students had the highest levels of prosocial motivation, became more engaged with the writing assignment, and ultimately benefited the most from the intervention.

Here, we test whether we can encourage all students to write about prosocial utility value with a new version of the UVI. Reflecting on ways in which course topics are relevant to prosocial goals might help students develop stronger, more meaningful connections with course topics, and perhaps even perceive STEM fields as having more prosocial potential. Indeed, simply including this type of assignment in the curriculum might convey that an instructor values prosocial applications. Because the UVI is a course assignment, it represents a type of intervention that has the potential to influence students’ perceptions of their instructors, and the field more generally (Benson-Greenwald et al., 2021). But should this new UVI emphasize prosocial value to the exclusion of personal value? It may be that emphasizing prosocial value instead of personal value in the UVI would be a powerful way to convey that STEM fields can be prosocial. On the other hand, this approach might undercut the efficacy of the “standard” UVI, if the power of the standard UVI is due to its focus on personal connections (Hecht, Priniski, et al., 2019; Hidi et al., 2019). For instance, a linguistic measure of personal relevance in the essays students wrote mediated the effects of the intervention tested by Harackiewicz, Canning et al. (2016) on long-term persistence in the biomedical sciences, highlighting the importance of personal connections for motivation and academic choices (Hecht, Harackiewicz, et al., 2019).

Given that our goal in developing a new, more prosocial UVI is to help students find personally meaningful prosocial connections, emphasizing both types of value may be critically important. A focus on both personal and prosocial values might have stronger effects than emphasizing either one alone. However, this may make the essay assignment more complex or more challenging. It is therefore important to explore both ways of promoting prosocial value with a UVI, and to compare them to the standard UVI tested in previous research.

Project Overview

In three studies, we test different versions of a prosocial utility-value intervention and examine students’ writing and experiences in gateway college science classes. We first compare students’ writing in response to two different ways to promote prosocial utility value with a UVI (either an exclusive emphasis on prosocial value or an emphasis on prosocial value in combination with personal value; Studies 1a and 1b). We next present the first randomized test of the prosocial and standard UVI in introductory chemistry (Studies 2a and 2b), examine motivation and course performance outcomes with a diverse group of students, and begin to map the linguistic and psychological mechanisms through which the UVIs work. We then test the impact of the prosocial UVI in an introductory biology course at the same university (Study 3), which allowed for a second test of the prosocial UVI in a different gateway science course. Deidentified data and analysis scripts for Studies 1 and 2 are available at https://osf.io/kmnrw.

Studies 1a and 1b: Designing a Prosocial Utility-Value Intervention

The goal of Studies 1a and 1b was to develop a prosocial version of the standard UVI tested in previous research (Harackiewicz, Canning et al., 2016). Specifically, we aimed to test how different versions of a prosocial UVI affected students’ ability to make high-quality connections about the prosocial usefulness of course material. We designed a Prosocial-Only UVI assignment that focused exclusively on prosocial task value and a Prosocial-Combined UVI assignment that focused on both personal and prosocial task values. In Study 1a, we tested these new assignments alongside the Standard UVI assignment and a Control assignment in which students summarized course material (but did not write about utility value) in an introductory biology course. This design allowed us to examine the essays that students wrote in response to each assignment and explore the quality of the writing content, all relative to a control assignment. In Study 1b, we tested for replication of linguistic results from Study 1a with these same four assignments, adapted for an introductory chemistry class.

These new writing prompts were designed to promote reflection on prosocial value while providing choice with respect to the type of prosocial value to write about. Another key to designing an effective prosocial UVI assignment was to retain as many of the beneficial features of the standard UVI assignment as possible. Previous work suggests that the intervention is more effective if administered three times over the course of the semester (Canning et al., 2018). In addition, the intervention is more effective when students are given a combination of different types of writing tasks (e.g., essays and letters), and provided with a choice regarding the assignment format (Priniski et al., 2019; Rosenzweig et al., 2018). Therefore, we administered the UVIs in three different formats over the course of the semester, with the first being an essay, the second a letter, and the third a choice between an essay and a letter.

Study 1a Method

This study was conducted in an introductory biology course at a large Hispanic-Serving university in southern California in 2018. The course introduces general principles in organismal biology and serves as a key prerequisite to upper division courses in biological science. The study was designed to test the feasibility of incorporating different versions of the UVI writing assignment into the curriculum, and to inform the development of prosocial UVIs, and it was not preregistered. We examined the content of students’ essays to analyze students’ writing in response to the four types of UVI assignment (i.e., the four experimental conditions). We did not, however, test for intervention effects on grades in this study because of concerns about statistical power for tests of interaction terms across four conditions with a small sample, given our predictions that intervention effects should be moderated by student background variables. Tests for effects on grades are tenable with larger samples in Studies 2a, 2b and 3.

Participants

In total, 282 students were enrolled in the course, of whom 231 students consented and completed the course and at least one of the writing assignments (82%). Of the 231 students in our sample, 65 were FG students (28%) and 166 were continuing-generation (CG; at least one parent earned a 4-year-college degree) students (72%). There were 75 URM students (32%; 45 Hispanic or Latinx, 23 Black, 9 American Indian, 1 Pacific Islander), and 156 majority students (105 White and 51 Asian or Asian American). In total, 170 identified as women (74%) and 61 identified as men (26%). The average age was 19.8 years (SD = 1.94).

Procedure

Students were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: a control condition or one of three UVI conditions (“standard,” “prosocial-only,” or “prosocial-combined”). In each condition, students completed three writing assignments (500–600 words) for course credit throughout the semester. Students in the control condition were asked to summarize course material (as in Harackiewicz, Canning et al., 2016), whereas in the three UVI conditions, students were asked to summarize course material and describe its usefulness to themselves and/or to helping others.

For each assignment, students were provided with a condition-specific prompt, delivered via online course software. Students were asked to formulate and answer a question, and examples of scientific questions were provided (e.g., “How do scientists form a hypothesis?”). In the control condition, students were asked to provide references for the scientific content of their essays. In the three UVI conditions, students were asked to explain how the scientific content of their essays could be applied, either to (1) their own life (standard UVI), (2) helping others (prosocial-only UVI), or (3) their own life and to helping others (prosocial-combined UVI).

In each UVI condition, the assignment instructions provided three short examples of potential applications; examples were associated with a common stem (e.g., “Medical researchers use systems biology to study how genes and proteins interact to cause diseases”). In the standard condition, there were three personal examples (e.g., “In your own life, you will have access to more effective treatments for any serious illnesses you develop, thanks to these advances”); in the prosocial-only condition, there were three prosocial connections to society, community and family (e.g., “In our society, these advances help doctors fight public health threats”); in the prosocial-combined condition, there were three pairs of personal and prosocial connections combined (“In your own life, you will have access to more effective treatments for any serious illnesses you develop, thanks to these advances. In our society, these advances help doctors fight public health threats”). Sample questions and examples were developed in conjunction with the course instructor. See Appendix A for instructions and examples; see Supplement for assignment templates.

Measures

Research assistants read and coded each essay (with condition masked), indicating whether it included relevance for: (a) the author or letter recipient (personal relevance), (b) family members, (c) community, or (d) society, and finally, whether each essay included discussion of (e) prosocial value (i.e., the value of material for helping others). Interrater reliability with this coding rubric ranged from 81% (connections to community) to 94% (connections to family) between the five categories. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

We then used Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software (LIWC) to explore students’ writing style and the content of their essays (Pennebaker et al., 2015). LIWC calculates the proportion of words in each essay that falls into psychologically meaningful categories (e.g., family-related words), as well as some general writing style measures. We examined three measures of linguistic style: word count (which is indicative of engagement), analytical thinking, and personal focus. For analytic thinking, lower scores indicate informal, narrative writing and higher scores indicate more formal, abstract writing (Pennebaker et al., 2015). The personal focus measure indicates the extent to which students were writing about themselves and others using first-person singular and second-person pronouns (e.g., I, my, your; Hecht, Harackiewicz, et al., 2019). We also examined three measures of writing content: we used the LIWC dictionary, family words, a dictionary developed by Frimer and colleagues (2014) that counts prosocial words (e.g., help, assist, support) and a dictionary developed by Pietraszkiewicz et al. (2018) measuring communion (e.g., care, generous, shared).

Study 1a Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables for both Study 1a and Study 1b.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of writing variables for Study 1a and Study 1b

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Word count | |||||||||||

| 2. Analytic scores | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| 0.05 | |||||||||||

| 3. Personal focus | 0.06 | −0.59 | |||||||||

| 0.04 | −0.60 | ||||||||||

| 4. Family words | 0.13 | −0.25 | 0.35 | ||||||||

| 0.00 | −0.24 | 0.40 | |||||||||

| 5. Prosocial words | 0.12 | −0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | |||||||

| 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| 6. Communion words | 0.10 | −0.29 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.67 | ||||||

| 0.02 | −0.30 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.66 | |||||||

| 7. Personal connections | 0.13 | −0.37 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.29 | |||||

| 0.06 | −0.33 | 0.59 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.24 | ||||||

| 8. Family connections | 0.16 | −0.40 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.45 | ||||

| 0.07 | −0.28 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.43 | |||||

| 9. Community connections | 0.00 | −0.15 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |||

| 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.18 | ||||

| 10. Society connections | 0.17 | −0.16 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.30 | ||

| 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.21 | |||

| 11. Prosocial connections | 0.13 | −0.33 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.79 | |

| 0.05 | −0.18 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.70 | ||

| Study 1a Mean | 571.14 | 84.10 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 2.46 | 1.04 | 0.57 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.60 | 1.36 |

| Study 1a SD | 51.30 | 8.26 | 1.15 | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.69 |

| Study 1b Mean | 557.53 | 85.90 | 1.43 | 0.10 | 1.32 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| Study 1b SD | 45.23 | 8.58 | 1.31 | 0.13 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.32 |

Note. For each variable in the correlation matrix, there are two rows. The top row shows the Study 1a correlation, and the bottom row shows the Study 1b correlation. For Study 1a, all correlations |r| > .14 are significant at p < .05. For Study 1b, all correlations |r| > .05 are significant at p < .05.

Qualitative Coding

To analyze the types of connections students made in their essays, we used two-level logistic regressions (with assignments nested within students) to test whether the number of personal, family, community, society, and prosocial connections differed by condition. Specifically, for each type of connection we fit three models regressing whether that connection was present (1) or absent (0) for each essay on dummy-coded contrasts, such that we could test every pairwise comparison of conditions (i.e., first with “control” as the reference group, then with “standard UVI” as the reference group), including a random intercept for students. Because every student in the sample completed at least one essay there was no missing data for this analysis. All results discussed below were statistically significant; see Table 2 for full results.

Table 2.

Qualitative Essay Coding: Proportion of Students Making Each Type of Connection

| Control | Standard | Prosocial-Only | Prosocial-Combined | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Connections | ||||

| Study 1a | .02 | .67a | .24 | .75a |

| Study 1b | .02 | .63a | .24 | .67a |

| Study 3 | - | .80a | - | .81a |

| Connections to family | ||||

| Study 1a | .01 | .30a | .14 | .35a |

| Study 1b | .00 | .28a | .18 | .27a |

| Study 3 | - | .43 | - | .51 |

| Connections to Community | ||||

| Study 1a | .03c | .07ac | .15ab | .28b |

| Study 1b | .01 | .06 | .13a | .15a |

| Study 3 | - | .08 | - | .21 |

| Connections to Society | ||||

| Study 1a | .27 | .64a | .75ab | .79b |

| Study 1b | .11 | .19 | .56a | .54a |

| Study 3 | - | .07 | - | .49 |

| Prosocial Connection | ||||

| Study 1a | .40 | .81a | .92ab | .96b |

| Study 1b | .08 | .20 | .42a | .49a |

| Study 3 | - | .11 | - | .45 |

Note. Proportions within studies 1a (biology), 1b (chemistry), or 3 (biology) that share a superscript do not differ significantly from one another; all other differences are significant at the p < .05 level.

Qualitative analyses indicate that the UVIs were successful in promoting different types of relevance in students’ writing. Importantly, prosocial-combined essays were as personal as standard essays and as prosocial as prosocial-only essays, demonstrating that students were able to articulate both types of utility-value connections in a single assignment without a reduction in the number of connections. In fact, there were more of almost every type of relevance connection in the prosocial-combined assignments than in the standard or prosocial-only assignments. Students made personal and family connections most often in the prosocial-combined and standard conditions (relative to the control and prosocial-only conditions), whereas they made more community, society and prosocial connections in the prosocial-combined and prosocial-only conditions (relative to the control and standard conditions).

Linguistic Analysis

We used multiple regression to analyze condition effects on three measures of writing style (word count, analytic writing and personal focus), and three measures of content (family, prosocial, and communion words). Orthogonal contrasts were used for three comparisons: (1) UVI (standard, prosocial-only, and prosocial-combined) compared to the control group, (2) Any Prosocial vs. Standard UVI and (3) Prosocial-Combined vs. Prosocial-Only UVI. We also included FG status, URM status, and gender as covariates. In all analyses for this paper, we handled missing data with FIML using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). Table 3 presents an abbreviated summary of condition effects for linguistic analysis; full results are presented in Supplement.

Table 3.

Linguistic Analysis of Essays: Study 1a (N = 231), Study 1b (N = 1715), and Study 3 (N = 712)

| UVI vs. Control | Prosocial-Combined/Prosocial-Only vs. Standard | Prosocial-Combined vs. Prosocial-Only | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | z | p | β | z | p | β | z | p | |

| Word count | |||||||||

| Study 1a | .13 | 2.01 | .044 | .02 | 0.33 | .740 | −.04 | −0.55 | .583 |

| Study 1b | .07 | 2.83 | .005 | .02 | 0.80 | .426 | .06 | 2.27 | .023 |

| Study 3 | .07 | 1.93 | .054 | ||||||

| Analytic scores | |||||||||

| Study 1a | −.40 | −6.56 | .000 | .01 | 0.21 | .830 | −.06 | −1.06 | .289 |

| Study 1b | −.38 | −16.76 | .000 | .05 | 1.97 | .049 | −.11 | −4.74 | .000 |

| Study 3 | −.10 | −2.63 | .009 | ||||||

| Linguistic Content | |||||||||

| Personal focus | |||||||||

| Study 1a | .57 | 11.79 | .000 | −.28 | −5.91 | .000 | .25 | 5.14 | .000 |

| Study 1b | .59 | 32.67 | .000 | −.19 | −10.06 | .000 | .22 | 11.44 | .000 |

| Study 3 | −.06 | −1.66 | .097 | ||||||

| Family words | |||||||||

| Study 1a | .31 | 4.94 | .000 | .02 | 0.31 | .757 | .08 | 1.28 | .201 |

| Study 1b | .40 | 17.35 | .000 | −.01 | −0.33 | .742 | .00 | 0.17 | .862 |

| Study 3 | −.02 | −0.48 | .634 | ||||||

| Prosocial words | |||||||||

| Study 1a | .29 | 4.65 | .000 | .19 | 3.04 | .002 | .01 | 0.16 | .873 |

| Study 1b | .24 | 10.32 | .000 | .25 | 10.60 | .000 | .04 | 1.47 | .141 |

| Study 3 | .38 | 10.84 | .000 | ||||||

| Communion words | |||||||||

| Study 1a | .35 | 5.79 | .000 | .16 | 2.66 | .008 | .12 | 2.01 | .045 |

| Study 1b | .29 | 12.25 | .000 | .13 | 5.44 | .000 | .08 | 3.33 | .001 |

| Study 3 | .27 | 7.49 | .000 | ||||||

Note. All models control for gender, and the models for Study 1a and Study 3 also control for FG status and URM status. The UVI vs. Control contrast compares the three UVI conditions (each coded + .25) to the control condition (−.75); the Prosocial-Combined/Prosocial-Only vs. Standard contrast compares the Prosocial Combined and Prosocial-Only conditions (each coded +.33) to the Standard UVI condition (−.67); the Prosocial-Combined vs. Prosocial Only contrast compares the prosocial combined UVI (.5) to the prosocial-only UVI (−.5).

With respect to linguistic style, results of the linguistic analysis showed that students in UVI conditions wrote longer essays, β = .13, p = .044, and had lower analytic scores, β = −.38, p < .001, compared to control, suggesting that UVI writing was more narrative and informal. Results with the personal focus measure revealed several significant effects. Students in UVI conditions wrote more personally-focused essays compared to those in the control condition, β = .57, p < .001, and students in the prosocial-combined and prosocial-only conditions wrote less personally-focused essays, compared to those in the standard condition, β = −.28, p < .001. Finally, students in the prosocial-combined condition wrote more personally-focused essays than those in the prosocial-only condition, β = .25, p < .001. In sum, the assignments that required personal connections (standard and prosocial-combined assignments) elicited more personally-focused writing than those that did not (control and prosocial-only assignments).

With respect to linguistic content, students in UVI conditions used significantly more family, prosocial, and communion words compared to the those in the control condition, ps < .001. Students in the prosocial-combined and prosocial-only conditions used more prosocial words than those in the standard condition, β = .19, p = .002, and more communion words, β = .16, p = .008. There was no significant difference in prosocial word usage between the prosocial-combined and prosocial-only conditions, β = .01, p = .873; however, students in the prosocial combined condition used more communion words compared to students in the prosocial-only condition, β = .12, p = .045.

Study 1a Discussion

Results suggest that the prosocial-combined prompt encouraged students to make strong prosocial value connections in their writing without sacrificing personal value connections. The writing produced in response to the prosocial-combined prompt was significantly more personal than that produced in response to the prosocial-only prompt, and just as prosocial. Thus, the prosocial-combined prompt seemed to best balance the two goals of encouraging prosocial value connections, while retaining the personal writing encouraged by the standard prompt.

The linguistic analyses provided insight into how the UVI assignments changed the way students wrote; utility-value essays and letters, whether personal (standard UVI) or prosocial (prosocial-combined and prosocial-only UVIs), were less formal and more personal than in control condition. Standard and both types of prosocial UVI assignments were similar in style, relative to control, but differed in word usage; prosocial assignments contained more words about helping others. Thus, the genre of the assignment—summary of course material (control) vs. summary plus discussion of value (UVI)—can drive changes in writing style, and changes in the UVI writing prompt can lead to differential word usage and themes within that genre.

An important limitation of these findings, however, is that our analysis was conducted in biology classes, where it may be relatively easy to find examples of personal and prosocial utility value. It is important to examine whether UVIs can help students make strong, personally meaningful value connections in other courses.

Study 1b: Testing the Prosocial UVI on Writing in Introductory Chemistry

The topics covered in introductory chemistry are often more abstract than topics in introductory biology, and it may be more challenging for students to make strong personal and prosocial connections with chemistry topics. In addition, because students often take introductory chemistry in their first year of college, writing assignments may be more challenging for students who are not yet comfortable writing college-level essays. Students may need more support or guidance in how to write essays in science courses, especially if those essays differ from more traditional science assignments (Huerta & Garza, 2019). Thus, we tested how the four types of UVI assignments affected writing in Chemistry, to determine whether the results of Study 1a would replicate in this new context—an introductory chemistry course at a large flagship university in the Midwest. These replication analyses were conducted in the context of a large-scale intervention study (described in Studies 2a and 2b).

Study 1b Method and Results

In total, 2,941 students were enrolled in the introductory chemistry course, of whom 2,765 students were over 18 years of age and consented (94%). Of those, 2,679 (2,169 in Fall semester of 2018, 510 in Spring semester of 2019) completed the course and a subset of Fall students comprise the sample for this replication analysis. As will be discussed in greater detail below (Studies 2a and 2b), assignment to condition was constrained by the number of FG and URM students in the class. Of the 2,679 students, only 487 were FG students (18%) and there were only 256 URM students (10%). Thus, there were too few FG and URM students in this course to test three different UVIs against control in a four-cell design with sufficient power. However, there were enough CG-Majority students in the fall semester to test replication of linguistic effects with a four-cell analytic design (N = 1715), including CG-majority students from the intervention study (Study 2a), with the addition of a reserve group of 174 CG-majority students assigned to a Prosocial-Only condition for purposes of these replication analyses. The methods and measures were identical to those in Study 1a, except that the writing assignments were customized for chemistry topics. Research assistants coded each of the approximately 8,000 essays, using the same coding scheme as in Study 1a (interrater agreement ranged from 84–96%). We also analyzed essays using the same six LIWC measures of linguistic style and content.

As in Study 1a, students were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: a control condition or one of three UVI conditions (standard, prosocial-only, or prosocial-combined). We used this four-cell design to test whether differences in the coded and LIWC measures found in Study 1a were replicated in the present study (see Tables 2 and 3). We used the same regression model with orthogonal contrasts for condition as in Study 1a, except that we only covaried gender (because students were all CG-Majority in this study).

The results largely replicated the differences found between conditions in Study 1a. Personal and family connections were significantly higher in the prosocial-combined and standard conditions, relative to the prosocial-only condition, whereas community, society, and prosocial connections were higher in the two prosocial conditions, relative to the standard condition. These findings indicate that, as in Study 1a, the prosocial-combined writing prompt evoked writing that was as personal as the standard prompt and as prosocial as the prosocial-only prompt. As in Study 1a, we found significant effects of the UVI contrast on all six linguistic variables, and all significant condition effects from Study 1a were replicated in Study 1b (see Table 3).2 These results suggest that the prosocial-combined UVI balances the two goals of encouraging prosocial value connections, while retaining the personal writing encouraged by the standard UVI prompt. Although the results of Study 1b replicated Study 1a, it is important to note that they were based on a CG-Majority sample, due to statistical power issues. However, we also examined the effects of different UVIs on writing for FG and URM students to the extent possible in smaller analytic designs in Studies 2a and 2b.2

Study 2: Testing the Effects of Utility-Value Interventions on Performance and Motivation in Introductory Chemistry

At many universities, introductory biology courses are taken in the second year, whereas introductory chemistry courses often serve as the first gateway science course that students take in college. If courses are taken in this sequence, interventions in biology courses, such as that tested by Harackiewicz et al. (2016), may come too late to prevent some attrition from STEM, given that attrition tends to be highest during first-year gateway courses (Gasiewski et al., 2012; Stout et al., 2011). Thus, it may be especially important to help students find value in first-year introductory chemistry, with the goal of promoting motivation and performance for underrepresented students in particular (Morra, 2018; Wang et al., 2021). If UVIs prove to be effective in introductory chemistry, we may be able to help students who might otherwise leave STEM before ever enrolling in introductory biology classes.

In Study 2, we tested the novel prosocial-combined UVI in a large introductory chemistry course, comparing it to the standard UVI and a control group in this new context. Specifically, we sought to answer the following questions: What are the effects of the prosocial-combined and standard UVIs on course performance and motivational outcomes? Are they stronger for FG and URM students? As noted in Study 1b, this course was taken by nearly 3,000 students, and this large sample size allowed us to examine the effects of both UVIs on academic outcomes for FG students in this new context, but the sample size was not large enough to test both versions of the UVI for URM students. We also developed a new measure of prosocial chemistry motivation to test whether the effects of the novel prosocial-combined intervention were stronger for students higher in prosocial motivation.

Prior research with UVIs and purpose interventions has found that such interventions are particularly effective for students who struggle in classes (e.g., Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009, Hulleman et al., 2017; Yeager et al 2014). In previous tests of UVIs in college courses, researchers have tested measures such as prior GPA or early exam scores in the course (Hulleman et al., 2010) as moderators of intervention effects, arguing that such measures help identify students most at risk for poor performance in the class (Hulleman et al., 2017), and others have tested moderation by both prior GPA and confidence (or expectations for success in the course; Harackiewicz, Canning, et al., 2016; Canning et al., 2018; Rosenzweig et al., 2020). We initially planned to test both moderators, but because introductory chemistry is typically taken by first-semester college students, over 90% of participants in this study had no record of prior performance in college (and there were no exams or other performance measures in the course prior to the first UVI assignment). Moreover, there were high levels of missing data on other prior performance variables (e.g., ACT scores). Thus, we deviated from our plan to test both confidence and prior performance as moderators, testing only confidence as a moderator in this first-year chemistry class (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020).

Of course, confidence should be related to prior performance (Bandura, 1982), but in recent studies that included measures of both prior GPA and performance expectations in a course, the correlations have been relatively low (e.g., r =.13 in Harackiewicz, Canning, et al., 2016). Indeed, researchers have more recently argued that confidence is a more forward-looking variable that might affect how students reflect on the utility value of course material in the near and distant future, as opposed to measures of prior performance that indicate a risk for poor performance in a course (see Hecht, Harackiewicz, et al., 2019). That is, confidence is more closely aligned with expectancies for success in an expectancy-value formulation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), whereas prior performance is aligned with students’ history of achievement and preparation for a course.3

To recap, we tested the following hypotheses in Study 2, all pre-registered:

The standard and prosocial-combined UVI would improve students’ chemistry performance, relative to control.

Both UVIs would be particularly effective for FG and URM students in promoting motivation (i.e., engagement, interest, and future STEM plans) and performance. In addition, the new, prosocial-combined utility value intervention may be particularly powerful for FG and URM students, and for students who are higher in prosocial motives.

The effects of both UVIs may differ as a function of confidence. We predicted that less confident students (i.e., struggling students) would benefit the most, to the extent that confidence is an indicator of prior performance. However, if confidence is primarily forward-looking, we might expect more confident students to benefit most (consistent with expectancy-value theory and previous findings; Hecht, Harackiewicz, et al. 2019).

Study 2 Method

We conducted a large-scale randomized intervention trial across two semesters of an introductory chemistry course at a large, flagship state university (Fall 2018 and Spring 2019), preregistered on AsPredicted (see https://aspredicted.org/N7M_HSH, https://aspredicted.org/5LL_2D3, https://aspredicted.org/HX8_12S).4 This chemistry course is required for students on pre-health tracks (e.g., pre-med, pre-dental, pre-pharmacy), as well as students who are studying engineering, agricultural and life sciences, and environmental sciences. Students typically take this course in the fall of their first year of college as a prerequisite to more advanced science courses, though the course is also offered in the Spring semester (in which enrollment is nearly 75% lower). Students in this study were in one of eight lecture sections of the course (six in the Fall semester, two in Spring); taught by one of five instructors. All students were also enrolled in one of 140 lab sections (109 in Fall, 31 in Spring). Course grades were determined by a combination of exams, lab grade, quizzes, online activities, and the writing assignments (worth 1.5% of the total grade).

Participants

As noted in Study 1b, 2,941 students were enrolled in the course, of whom 2,765 students were over 18 years of age and consented (94%). Of those, 2,679 completed the course and 2,505 were assigned to the control, standard utility value, or prosocial-combined utility value condition and comprise the sample for the current study (1995 in Fall, 510 in Spring).5 Although the Fall and Spring sections of the course differed in terms of students’ characteristics (with proportionally more FG and URM students in Spring), the content and structure of the course was the same, and we combined all sections of the course for analytic purposes. Of the 2,505 students, 487 were FG students (19%) and 2,018 were CG students (81%). There were 256 URM students (10%; 168 Hispanic or Latinx, 80 Black, 15 American Indian or Alaska Native, and 10 Pacific Islander) and 2,249 racial/ethnic majority students (90%; 1,974 White, 343 Asian or Asian American). Regarding gender, 1,402 identified as women (56%), 1,100 as men (44%), and three as non-binary (< 1%).6 The average age was 18.8 years (SD = 0.9).

Procedure

Students completed questionnaires in the first and final weeks of the semester via Qualtrics and three UVI or control writing assignments (500–600 words each) over the course of the semester. All assignments were completed for course credit, but students were only included in the research study if they consented. Grades were obtained from instructors.

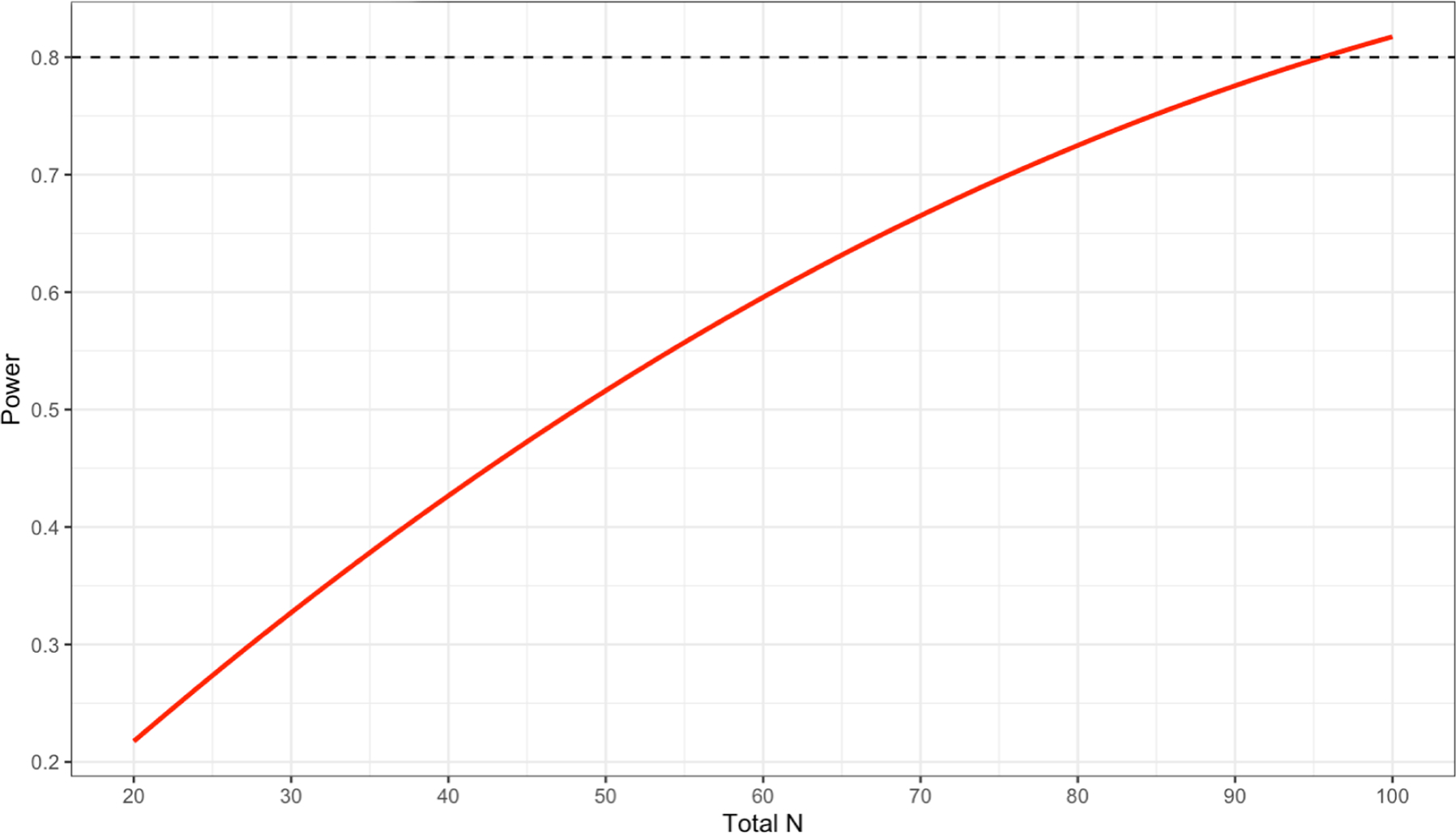

Experimental Design and Assignment to Condition

Students were blocked on FG status, URM status, and gender, and then randomly assigned to condition, within lecture sections. Despite a large overall sample size (N = 2,505, CG-majority students made up 75% of the sample (N = 1,867) whereas the numbers of FG-majority (N = 382), CG-URM (N = 151), and FG-URM (N = 105) students were low. We therefore needed to consider the implications for statistical power when deciding how many versions of the UVI to test with each group. There were too few FG students in this course to test three different UVIs against control in a four-cell design with sufficient power, and too few URM students to even test two UVIs against control in a three-cell design with sufficient power. Accordingly, we developed a procedure for assigning participants to condition within two experimental designs, henceforth referred to as Studies 2a and 2b (Table 4) to address different research questions.

Table 4.

Experimental Designs in Study 2

| A. Study 2a Three-Cell Design (FG- and CG-Majority students in the Fall and Spring semesters) (N = 2,249) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Standard UVI | Prosocial-Combined UVI | |

| CG-Maj: 725 | CG-Maj: 513 | CG-Maj: 629 | |

| FG-Maj: 129 | FG-Maj: 129 | FG-Maj: 124 | |

| Total: 854 (685 in Fall) | Total: 642 (471 in Fall) | Total: 753 (663 in Fall) | |

| B. Study 2b Two-Cell Design (FG- and CG-URM students in the Fall and Spring semesters) (N = 256) | |||

| Control | Standard or Prosocial-Combined UVI* | ||

| CG-URM: 74 | CG-URM: 77 | ||

| FG-URM: 53 | FG-URM: 52 | ||

| Total: 127 (85 in Fall) | Total: 129 (91 in Fall) | ||

Note. CG = continuing-generation college student, FG = first-generation college student, Maj = racial/ethnic majority, URM = underrepresented racial/ethnic minority.

After the conclusion of the Fall semester, in which URM students had been assigned to the Prosocial-Combined UVI, a check for adverse outcomes revealed a negative effect of the intervention on course grades for this group. Therefore, in the spring semester, we assigned URM students to the Standard UVI.

Study 2a: Testing Prosocial-Combined and Standard UVIs against control with majority students.

We randomly assigned CG-majority and FG-majority students in both Fall and Spring to one of three conditions. This allowed us to compare the effects of two versions of the UVI (standard and prosocial-combined) relative to control in a three-cell design, and test how these effects varied for different subgroups of majority students (e.g., FG-majority students).

Study 2b. Testing a single UVI against control with URM students.

We randomly assigned all CG-URM and FG-URM students to a two-cell design, testing the prosocial-combined UVI vs. control. This allowed us to test a single version of the UVI relative to control for the relatively smaller number of URM students in this course. However, a check for adverse outcomes in the Fall semester revealed a negative effect of the prosocial-combined UVI on course grades for URM students. Therefore, in the Spring semester, we randomly assigned URM students to the standard UVI or control.

The analytic procedures for each design were influenced by power considerations. When examining baseline data for all participants combined (prior to assignment to condition), the large sample size afforded statistical power to examine all higher-order interactions between demographic variables. However, when examining subsets of the sample, statistical power was reduced. Therefore, we adjusted the analyses by trimming higher-order interactions that were underpowered.

Deviations of Study 2 from Preregistered Analysis Plan

Here we discuss key deviations from our preregistered analysis plan (see Supplement for full details). We had initially randomly assigned CG-majority students to each of two different designs to compare how different sets of interventions affected FG-majority and URM students, as compared to CG-majority students. However, we later realized that this would lead to imprecise estimates driven by which CG-majority students were assigned to each design. Therefore, we decided to pool CG-majority students into a single three-cell design and analyze data for URM students in a separate two-cell design. We included all CG-majority students from the Fall semester in a four-cell design used only for testing replication of writing results from Study 1a (reported in Study 1b), to avoid using overlapping samples for course grade analyses (our primary preregistered outcome). In addition, we tested effects for URM students in a single two-cell design to prevent overlap between participants in the two-cell and three-cell designs.

In addition, we initially planned to run a large number of models to test similar hypotheses about intervention effects (15 models total). However, conducting so many statistical tests with multiple models would inflate our Type-I error rate and we therefore decided to consolidate models whenever possible (models are described in the Analysis Plan section). We also focused on only two of three possible preregistered non-demographic moderators (confidence about performance and prosocial chemistry motivation, but not prior GPA), and tested both in the same model, to avoid models that would further inflate the number of tests we ran. We determined that confidence about performance and prosocial chemistry motivation would be the most important moderators to keep for consistency with prior research and for alignment with our focus on prosocial motivation (e.g., Harackiewicz, Canning, et al., 2016; Hecht, Harackiewicz, et al., 2019; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; Priniski et al., 2019). As discussed below, we were unable to measure prior GPA for many students and encountered high levels of missingness with other background variables. Finally, we included several new variables to explore the mechanisms of treatment effects (essay grades and essay grade component scores) as well as effects on students’ perceptions of the field of chemistry (instructor perceptions and prosocial chemistry affordances).

Writing Assignments

All students were given three writing assignments over the course of the semester as graded homework and the procedures were the same as those in Study 1a. Examples of utility value connections were changed from biology to chemistry and are presented in the Appendix. Essays were graded by a team of advanced undergraduate students who had been successful in this introductory chemistry course, but they were not teaching assistants in the course and had no direct contact with students. These graders were recruited by the chemistry instructors and trained and supervised by the research team. Each grader graded only one type of assignment, using a rubric (see measures below). See Supplement for grading rubrics.

Measures

Demographics and Background Variables

Students reported their gender, parental education, and race/ethnicity. We categorized students as FG or CG and as URM or majority using the same method as in Study 1a. As measures of students’ academic and family background, we obtained students’ ACT scores from institutional records (11.5% missing data), and their high school GPAs (3.6% missing data) and a self-report measure of family income from the baseline questionnaire. We also obtained information about the high schools that students attended from institutional records and used a database from the National Center of Education Statistics (2022) to determine the percentage of students at each school who were eligible for Free and Reduced Lunch (FRL), an index of high school poverty (18.6% missing data).

Baseline Measures (first week of semester)

Items for all measures are shown in Appendix B. The three motivation variables were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale from Not at all true – Very true. Scales were adapted from those used by Harackiewicz, Canning, et al. (2016).

Confidence about Performance and Concern about Background.

The confidence measure was composed of three items (e.g., “I am confident that I will do well in this course”); α = .84.7 Concern about background was measured using three items (e.g., “I am not sure if I have the right background for this course”); α = .64. Although the reliability for this measure was lower than other measures used in this study, we retained this measure for consistency with previous research and relevance to the experience of FG students (Harackiewicz et al., 2014).

Interest.

Interest in chemistry was measured using ten items (e.g., “I think the field of chemistry is very interesting,” “I think what we’re learning in this course is important,” “The study of chemistry is personally meaningful to me”); α = .92. This measure was expanded beyond the measure used by Harackiewicz et al. (2016), which was primarily affect-based, and instead based on one developed for introductory courses by Harackiewicz, Durik and colleagues (2008), which assessed a deeper level of interest (i.e., personal meaningfulness and importance of the class, in addition to affective measures of enjoyment and interestingness). This new measure reflects maintained situational interest, as defined by the four-phase model of interest development (Renninger & Hidi, 2011).

Prosocial Motives for Attending College.

Students were asked about their motives for attending college by checking each item that was a “very important reason for completing your college degree.” This questionnaire was based on one originally developed by Stephens et al. (2012) to measure interdependent and independent motives for attending college. Harackiewicz, Canning, and colleagues (2016) used three of the six interdependent items as a measure of helping motives8: “Help my family out after I’m done with college,” “Give back to my community,” and “Provide a better life for my own children;” α = .53. Given that this scale focuses specifically on helping family and community, we used these three items to measure Family/Community Helping Motives, and added four new items to assess General Helping Motives: “Gain skills that I can use in a job that helps others,” “Learn things that will help me make a positive impact on the world,” “Make a contribution to society,” and “Help others;” α = .68. We computed scores on the two prosocial motives scales by counting how many relevant items students endorsed.

Prosocial Chemistry Motivation.

We created a new measure of course-specific prosocial motivation, Prosocial Chemistry Motivation, measured on a 7-point Likert scale from Unimportant reason for me – Very important reason for me, in response to the prompt “I want to study chemistry because…”. Prosocial chemistry motivation was measured using three items, “I want to make a contribution to society,” “I want to give back to my community,” and “a background in chemistry will allow me to help other people” (α = .85).

Final Questionnaire Measures (final weeks of semester)

Interest, Deeper Involvement, and Future Plans.

We used the same ten items as at baseline to assess interest in chemistry at the end of the semester (α = .94). In addition, we assessed students’ goals for deeper involvement in the chemical and health fields with a three-item scale (α = .87), “I would like to pursue a summer internship that is related to the chemical and health sciences,” “I intend to learn more about ongoing research opportunities in the chemical and health sciences at [university],” “It is important to me to obtain hands-on research experiences in the chemical and health sciences while I am a student.” We also measured Future Plans with two items (α = .93), “Do you intend to obtain a degree or certificate in the chemical and health sciences,” “Do you intend to pursue a career in the chemical and health sciences?” These scales were included to assess students’ deepening interests in biomedical fields more generally, and their plans for careers in biomedical fields.

Perceptions of Instructors’ Values.

We developed a new measure of students’ perceptions of their instructor’s prosocial values with three items measured on a 7-point Likert scale, using “My instructor” as the stem: “values the application of science to real life problems,” “believes that science can really help people,” “believes that science can help solve some of society’s problems” (α = .90).

Course Grades, Essay Grades, and Grade Components

Instructors provided grades for students in the course (A = 4.0, AB = 3.5, B = 3.0, BC = 2.5, C = 2.0, D = 1.0, F = 0.0). Students’ grades in the course were curved to approximately a B average (M = 2.9, SD = 0.9). Writing assignments were graded on a 20-point scale (essay grade; M = 17.0, SD = 2.8).

Study 2: Student Characteristics

We examined student characteristics across Studies 2a and 2b combined, in two ways. We used the entire sample (N = 2,505) to examine differences in background variables and motivation measures, prior to intervention. This was done to examine differences between different demographic groups on relevant measures such as prosocial motivation (a person variable). In addition, we explored course performance and linguistic variables from the essays, but only in the control group(s) because these variables were measured post-intervention (N = 981). These analyses were conducted to examine demographic differences in writing style and grades when writing assignments involved summaries of course topics but did not involve writing about the personal and/or prosocial utility value of course material. We tested the main effects of FG status, URM status, gender, all two- and three-way interactions between these variables, as well as semester (Spring = high, Fall = low) and all two-way interactions with semester on each variable. Regression results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Effects of FG Status, URM Status, Gender, and Semester on Baseline Measures in Studies 2a and 2b combined (N = 2,505) and Study 3 (N = 712), and on Linguistic Style and Performance Measures in the Control Group of Study 2 (N = 981)

| Study 2 | Study 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | z | p | β | z | p | |

| ACT Score | ||||||

| FG | −0.21 | −10.73 | .000 | −0.24 | −5.98 | .000 |

| URM | −0.12 | −5.62 | .000 | −0.24 | −5.76 | .000 |

| FG × URM | −0.09 | −3.71 | .000 | −0.04 | −0.83 | .406 |

| Gender | −0.10 | −5.10 | .000 | −0.04 | −1.19 | .233 |

| FG × Gender | −0.02 | −0.94 | .345 | 0.02 | 0.63 | .527 |

| URM × Gender | 0.02 | 1.13 | .258 | |||

| Spring | −0.23 | −11.37 | .000 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.03 | 1.48 | .138 | |||

| URM × Spring | −0.02 | −1.07 | .285 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.03 | 1.49 | .136 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | −0.01 | −0.61 | .543 | |||

| High School GPA | ||||||

| FG | −0.07 | −3.64 | .000 | −0.06 | −1.68 | .093 |

| URM | −0.10 | −4.44 | .000 | −0.10 | −2.41 | .016 |

| FG × URM | 0.04 | 1.76 | .078 | −0.01 | −0.25 | .804 |

| Gender | 0.17 | 8.57 | .000 | 0.20 | 5.43 | .000 |

| FG × Gender | 0.03 | 1.62 | .105 | 0.13 | 3.42 | .001 |

| URM × Gender | −0.05 | −2.31 | .021 | |||

| Spring | −0.19 | −8.94 | .000 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.00 | −0.11 | .915 | |||

| URM × Spring | 0.02 | 1.07 | .283 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.02 | 1.05 | .293 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | −0.01 | −0.36 | .721 | |||

| Family Income | ||||||

| FG | −0.44 | −23.95 | .000 | −0.42 | −12.14 | .000 |

| URM | −0.07 | −3.78 | .000 | −0.10 | −2.72 | .007 |

| FG × URM | −0.06 | −3.07 | .002 | −0.09 | −2.60 | .009 |

| Gender | −0.01 | −0.65 | .515 | 0.01 | 0.23 | .818 |

| FG × Gender | −0.02 | −1.12 | .262 | −0.04 | −1.22 | .222 |

| URM × Gender | 0.00 | −0.12 | .906 | |||

| Spring | −0.06 | −3.45 | .001 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.03 | 1.75 | .079 | |||

| URM × Spring | −0.03 | −1.43 | .152 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.02 | 0.95 | .344 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | −0.02 | −1.13 | .258 | |||

| High School Percentage FRL | ||||||

| FG | 0.20 | 9.60 | .000 | 0.29 | 7.28 | .000 |

| URM | 0.19 | 8.48 | .000 | 0.29 | 6.41 | .000 |

| FG × URM | 0.12 | 5.22 | .000 | 0.00 | 0.04 | .970 |

| Gender | −0.03 | −1.44 | .151 | −0.09 | −2.26 | .024 |

| FG × Gender | 0.00 | −0.15 | .883 | −0.05 | −1.29 | .198 |

| URM × Gender | 0.00 | −0.06 | .949 | |||

| Spring | 0.04 | 1.94 | .052 | |||

| FG × Spring | −0.04 | −1.66 | .098 | |||

| URM × Spring | −0.02 | −0.83 | .408 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.01 | 0.67 | .505 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | −0.02 | −0.98 | .328 | |||

| Interest | ||||||

| FG | 0.04 | 1.68 | .094 | 0.04 | 0.88 | .378 |

| URM | 0.03 | 1.43 | .152 | −0.01 | −0.16 | .876 |

| FG × URM | 0.00 | −0.03 | .972 | −0.01 | −0.25 | .804 |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.31 | .756 | 0.06 | 1.49 | .137 |

| FG × Gender | 0.03 | 1.42 | .154 | −0.07 | −1.87 | .061 |

| URM × Gender | −0.02 | −0.94 | .350 | |||

| Spring | −0.09 | −4.40 | .000 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.01 | 0.66 | .512 | |||

| URM × Spring | 0.02 | 0.79 | .431 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.00 | −0.19 | .846 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | 0.01 | 0.35 | .729 | |||

| Confidence | ||||||

| FG | −0.01 | −0.31 | .758 | −0.01 | −0.13 | .893 |

| URM | −0.03 | −1.20 | .230 | 0.00 | −0.08 | .938 |

| FG × URM | 0.03 | 1.19 | .234 | 0.04 | 1.00 | .316 |

| Gender | −0.27 | −13.54 | .000 | −0.18 | −4.71 | .000 |

| FG × Gender | −0.03 | −1.31 | .191 | −0.05 | −1.36 | .173 |

| URM × Gender | 0.02 | 0.79 | .432 | |||

| Spring | −0.13 | −6.31 | .000 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.00 | −0.14 | .887 | |||

| URM × Spring | −0.02 | −1.19 | .235 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.04 | 1.77 | .077 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | 0.02 | 0.77 | .440 | |||

| Concern about Background | ||||||

| FG | 0.05 | 2.27 | .023 | 0.00 | 0.03 | .976 |

| URM | 0.04 | 1.78 | .075 | 0.03 | 0.67 | .501 |

| FG × URM | 0.01 | 0.51 | .611 | 0.02 | 0.39 | .697 |

| Gender | 0.11 | 5.31 | .000 | −0.04 | −1.16 | .248 |

| FG × Gender | 0.01 | 0.58 | .560 | 0.08 | 2.11 | .035 |

| URM × Gender | −0.01 | −0.57 | .572 | |||

| Spring | 0.15 | 6.93 | .000 | |||

| FG × Spring | −0.01 | −0.67 | .503 | |||

| URM × Spring | −0.01 | −0.30 | .764 | |||

| Gender × Spring | −0.04 | −1.76 | .079 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | 0.02 | 0.91 | .365 | |||

| Family/Community Helping Motives | ||||||

| FG | 0.12 | 5.78 | .000 | 0.18 | 4.61 | .000 |

| URM | 0.05 | 2.06 | .039 | 0.02 | 0.45 | .650 |

| FG × URM | 0.06 | 2.71 | .007 | 0.04 | 1.06 | .289 |

| Gender | −0.01 | −0.33 | .745 | −0.07 | −1.91 | .056 |

| FG × Gender | 0.02 | 1.17 | .242 | 0.03 | 0.81 | .419 |

| URM × Gender | −0.05 | −2.47 | .013 | |||

| Spring | −0.02 | −0.89 | .372 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.01 | 0.62 | .539 | |||

| URM × Spring | 0.02 | 0.85 | .393 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.01 | 0.51 | .613 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | 0.00 | 0.05 | .963 | |||

| General Helping Motives | ||||||

| FG | −0.02 | −0.94 | .347 | 0.03 | 0.72 | .471 |

| URM | 0.00 | −0.01 | .990 | −0.04 | −1.05 | .296 |

| FG × URM | 0.00 | 0.22 | .829 | 0.02 | 0.40 | .687 |

| Gender | 0.16 | 7.92 | .000 | 0.04 | 1.12 | .262 |

| FG × Gender | −0.02 | −0.74 | .457 | −0.06 | −1.65 | .100 |

| URM × Gender | −0.04 | −1.65 | .099 | |||

| Spring | −0.04 | −1.83 | .067 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.02 | 0.81 | .420 | |||

| URM × Spring | −0.01 | −0.26 | .795 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.03 | 1.44 | .150 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | −0.03 | −1.42 | .156 | |||

| Prosocial Chemistry/Biology Motivation | ||||||

| FG | 0.02 | 1.15 | .249 | 0.06 | 1.47 | .141 |

| URM | 0.06 | 2.90 | .004 | −0.02 | −0.36 | .719 |

| FG × URM | 0.02 | 0.68 | .497 | 0.06 | 1.41 | .157 |

| Gender | 0.14 | 6.97 | .000 | 0.04 | 1.16 | .246 |

| FG × Gender | 0.03 | 1.26 | .207 | −0.07 | −1.92 | .055 |

| URM × Gender | −0.03 | −1.58 | .114 | |||

| Spring | −0.03 | −1.46 | .143 | |||

| FG × Spring | 0.02 | 1.02 | .308 | |||

| URM × Spring | 0.00 | −0.21 | .836 | |||

| Gender × Spring | 0.01 | 0.52 | .606 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | 0.00 | 0.06 | .952 | |||

| Course grade | ||||||

| FG | −.18 | −5.41 | .000 | |||

| URM | −.11 | −3.22 | .001 | |||

| FG × URM | −.02 | −0.68 | .495 | |||

| Gender | −.10 | −3.25 | .001 | |||

| FG × Gender | .02 | 0.51 | .607 | |||

| URM × Gender | −.06 | −1.76 | .078 | |||

| Spring | .04 | 1.30 | .195 | |||

| FG × Spring | .00 | −0.07 | .945 | |||

| URM × Spring | .00 | −0.07 | .940 | |||

| Gender × Spring | .01 | 0.39 | .697 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | .03 | 0.87 | .385 | |||

| Word Count | ||||||

| FG | −.10 | −2.85 | .004 | |||

| URM | −.02 | −0.45 | .655 | |||

| FG × URM | .01 | 0.19 | .847 | |||

| Gender | .06 | 1.82 | .069 | |||

| FG × Gender | .07 | 2.00 | .046 | |||

| URM × Gender | −.07 | −2.08 | .037 | |||

| Spring | −.02 | −0.56 | .579 | |||

| FG × Spring | .06 | 1.76 | .078 | |||

| URM × Spring | −.05 | −1.42 | .154 | |||

| Gender × Spring | −.01 | −0.30 | .763 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | .01 | 0.39 | .694 | |||

| Analytic words | ||||||

| FG | −.08 | −2.27 | .023 | |||

| URM | −.05 | −1.41 | .158 | |||

| FG × URM | −.02 | −0.56 | .577 | |||

| Gender | .05 | 1.53 | .127 | |||

| FG × Gender | .04 | 1.24 | .216 | |||

| URM × Gender | −.01 | −0.24 | .811 | |||

| Spring | −.13 | −3.97 | .000 | |||

| FG × Spring | .04 | 1.33 | .183 | |||

| URM × Spring | −.04 | −1.17 | .244 | |||

| Gender × Spring | −.03 | −0.98 | .328 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | .05 | 1.51 | .131 | |||

| Essay grade | ||||||

| FG | −.17 | −5.10 | .000 | |||

| URM | .00 | −0.14 | .889 | |||

| FG × URM | .00 | −0.10 | .921 | |||

| Gender | .14 | 4.43 | .000 | |||

| FG × Gender | .12 | 3.64 | .000 | |||

| URM × Gender | −.09 | −2.57 | .010 | |||

| Spring | −.04 | −1.33 | .183 | |||

| FG × Spring | .00 | −0.03 | .975 | |||

| URM × Spring | .01 | 0.40 | .688 | |||

| Gender × Spring | .02 | 0.48 | .635 | |||

| FG × URM × Gender | −.05 | −1.48 | .138 | |||

Note. All predictors were mean centered. FG = first-generation college students (FG = high, continuing-generation = low); URM = underrepresented minority students (URM = high, majority = low); Gender is coded women = high, men = low. In Study 3, we did not test interactions beyond FG × Gender due to power considerations. Study 3 was conducted in a single Fall semester and thus we did not test effects of semester (i.e., the Spring factor tested in Study 2). We were also unable to test effects on linguistic and performance measures in the control group of Study 3, as Study 3 had no control group.

We first examined differences in background variables (ACT, high school GPA, family income, FRL) and motivation measures (interest, confidence, concern about background, family/community and general helping college motives, and prosocial chemistry motivation) as a function of students’ demographic characteristics. All four background measures showed similar patterns for FG and URM students. Specifically, for ACT composite scores, family income, and high school GPA, there were significant negative effects, and on FRL, significant positive effects, for FG status, all p < .001, and URM status, all p < .001. There were no gender differences for family income or FRL, but women had lower ACT scores and higher high school GPAs, both p <.001, compared to men.

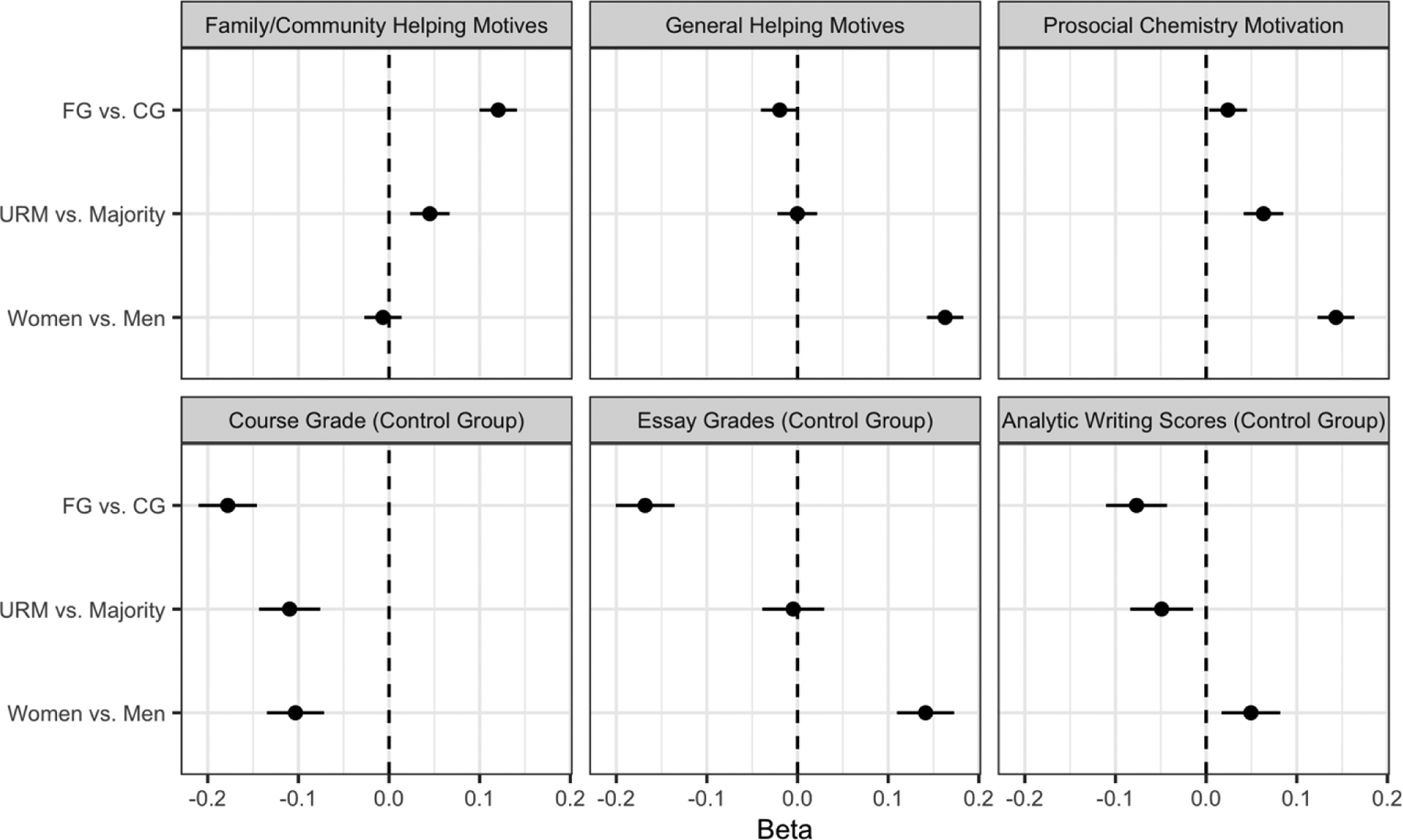

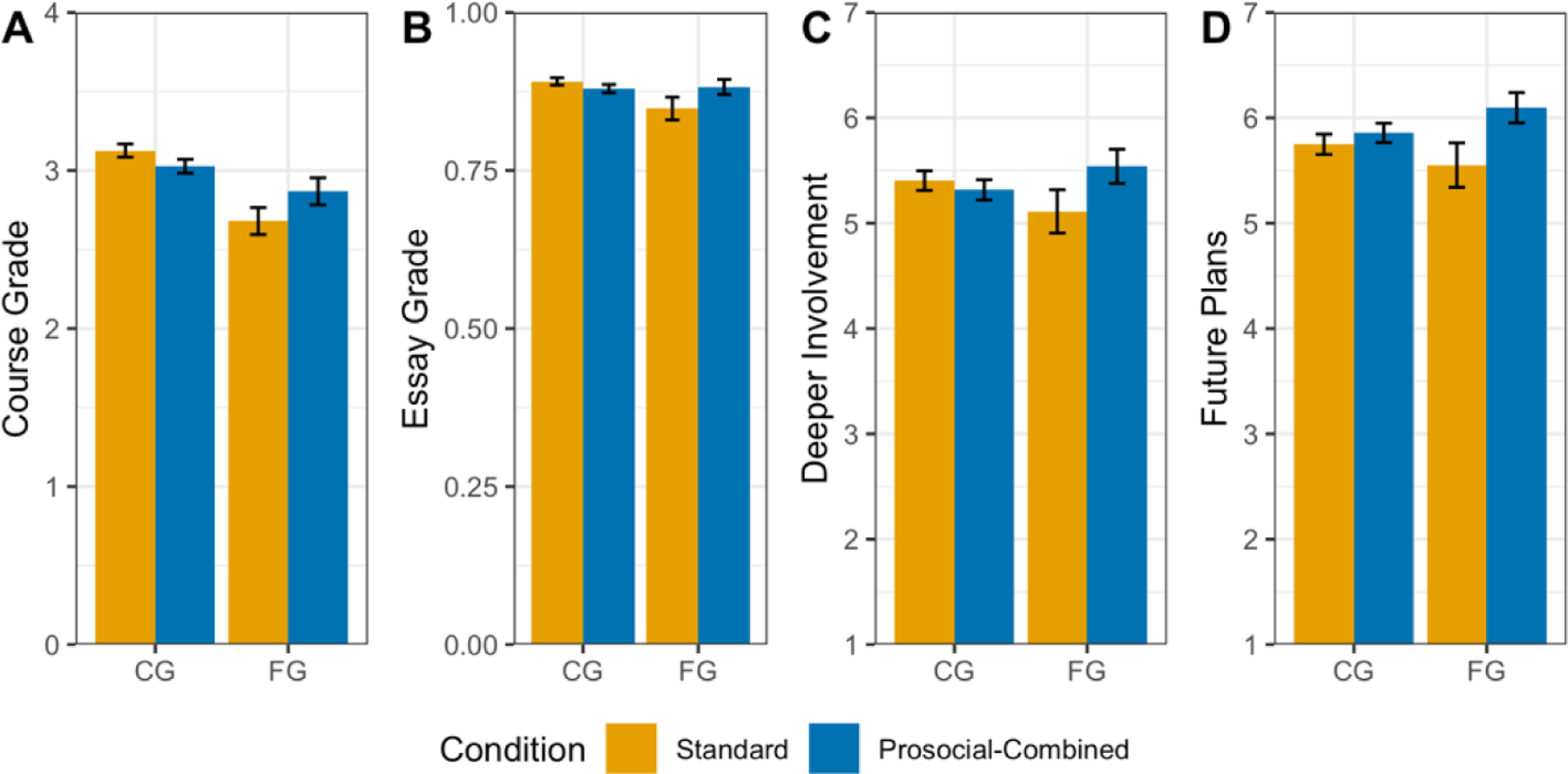

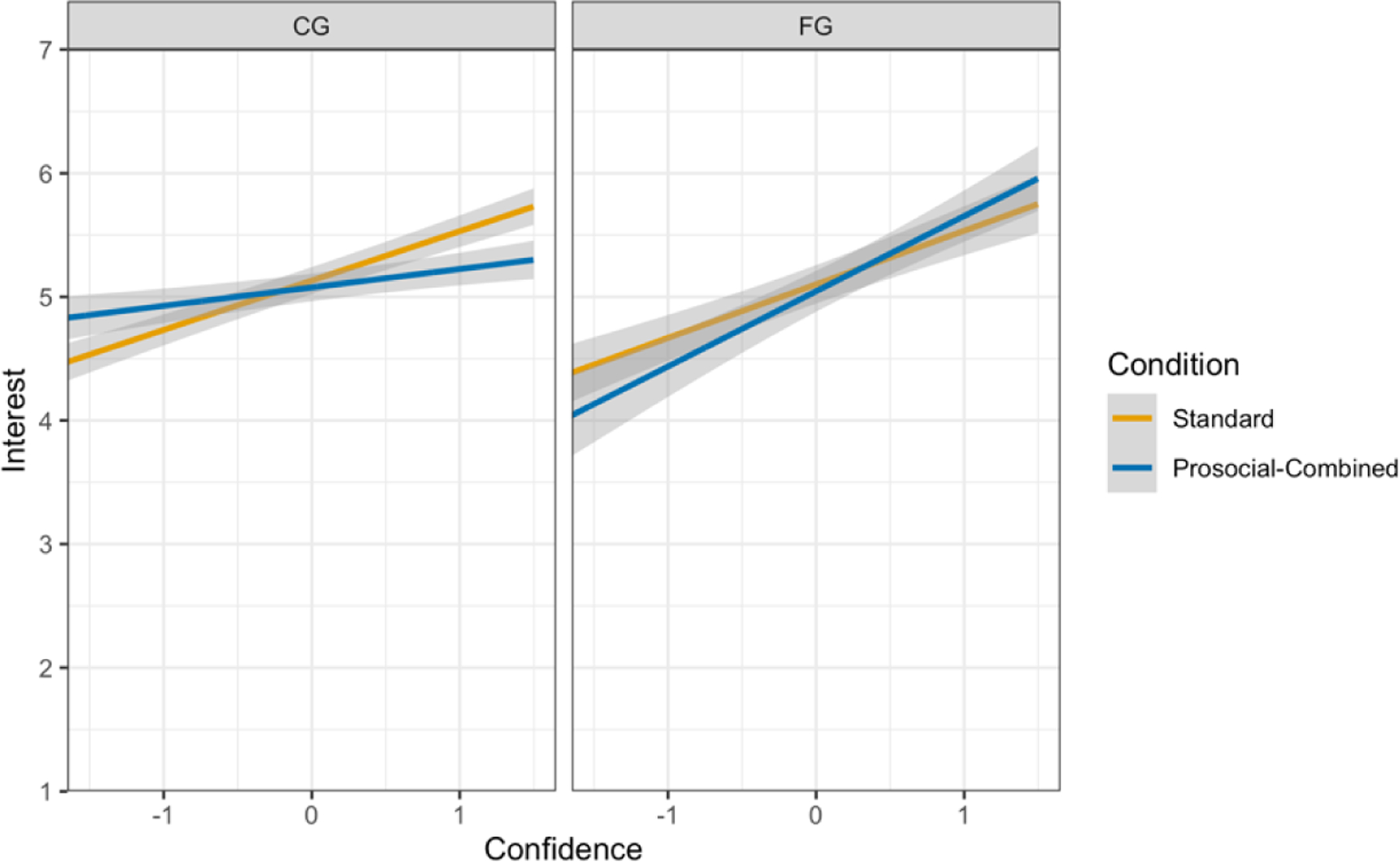

Analyses of motivation measures showed that FG students endorsed more family/community helping motives, p < .001, and reported higher levels of concern about background, p = .023, than CG students. URM students reported higher levels of prosocial chemistry motivation, p = .004, and family/community helping motives, p = .039, than majority students. Women reported higher levels of prosocial chemistry motivation, p < .001, general helping motives, p < .001, and concern about background, p < .001, and lower levels of confidence, p < .001, than men. Figure 1 shows the effect sizes (betas from the regressions) for the three measures of prosociality.

Figure 1.

Differences on Prosocial and Performance Measures, Study 2

Note. Standardized regression coefficients (i.e., betas) and standard errors, plotted from six regressions (three with the entire sample, and three with all students in the control group), each examining effects of FG status, URM status, and gender.

We then examined course grades, essay grades, and linguistic variables among students in the control condition. FG students, p < .001, URM students, p = .001, and women, p = .001, earned significantly lower grades in the course than CG students, majority students, and men, respectively. Figure 1 shows the effect sizes (betas) for course grades, essay grades and analytic writing for each group. Notably, the social class achievement difference in course grades was roughly twice as large as the URM and gender differences in course grades (β = −.18, for FG (vs. CG), compare to β= −.11, for URM (vs. majority), and β = −.10 for gender) in this class.

With respect to essay grades in the control group, FG students earned lower essay grades, p < .001, than CG students. FG students also wrote shorter essays, p = .004, and had lower analytic scores, p = .023. URM students did not differ from majority students in terms of essay grades, component scores, or analytic scores. In contrast, women earned higher essay grades, p < .001, than men, consistent with previous research (Petersen, 2018; Reilly et al, 2019).

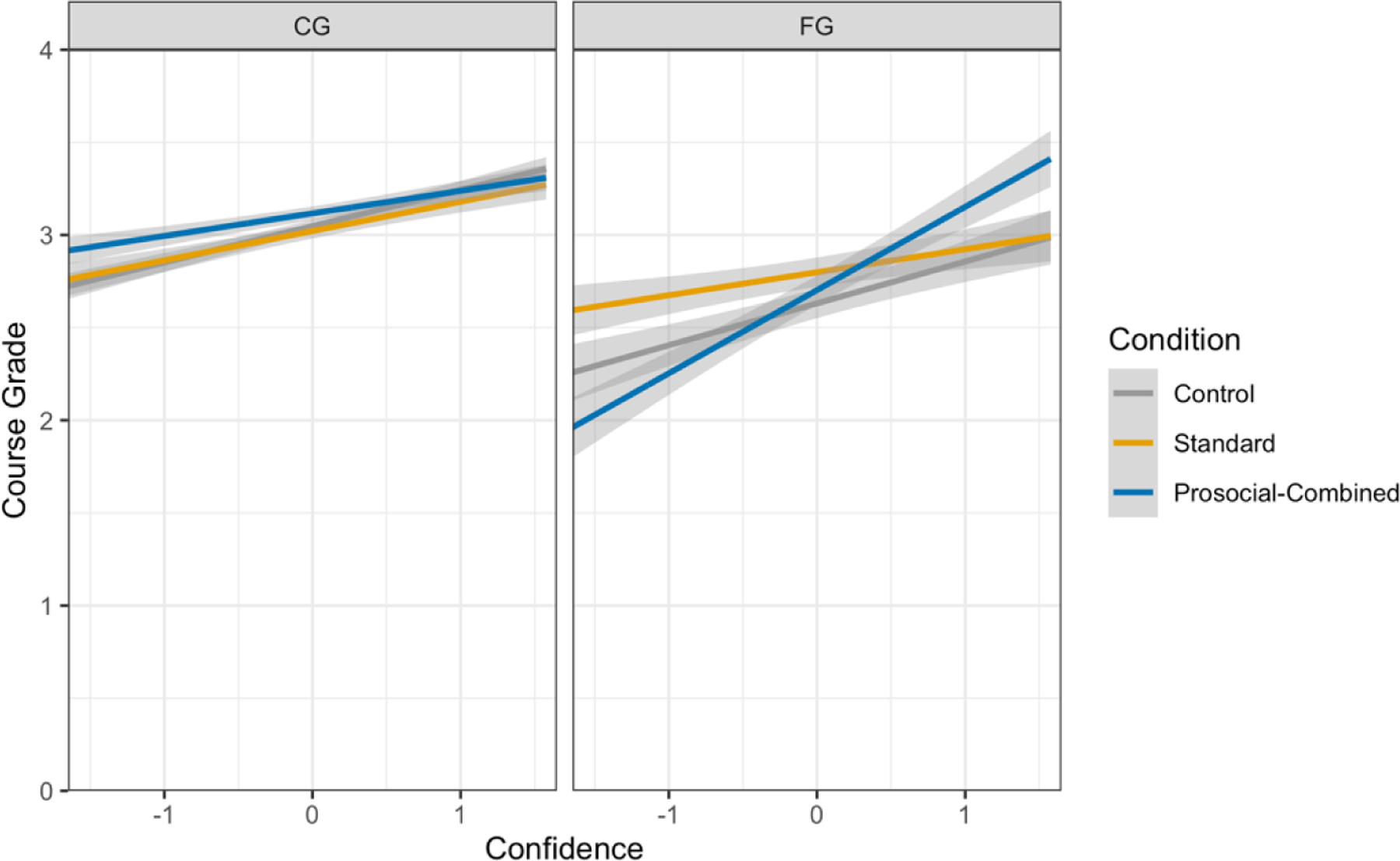

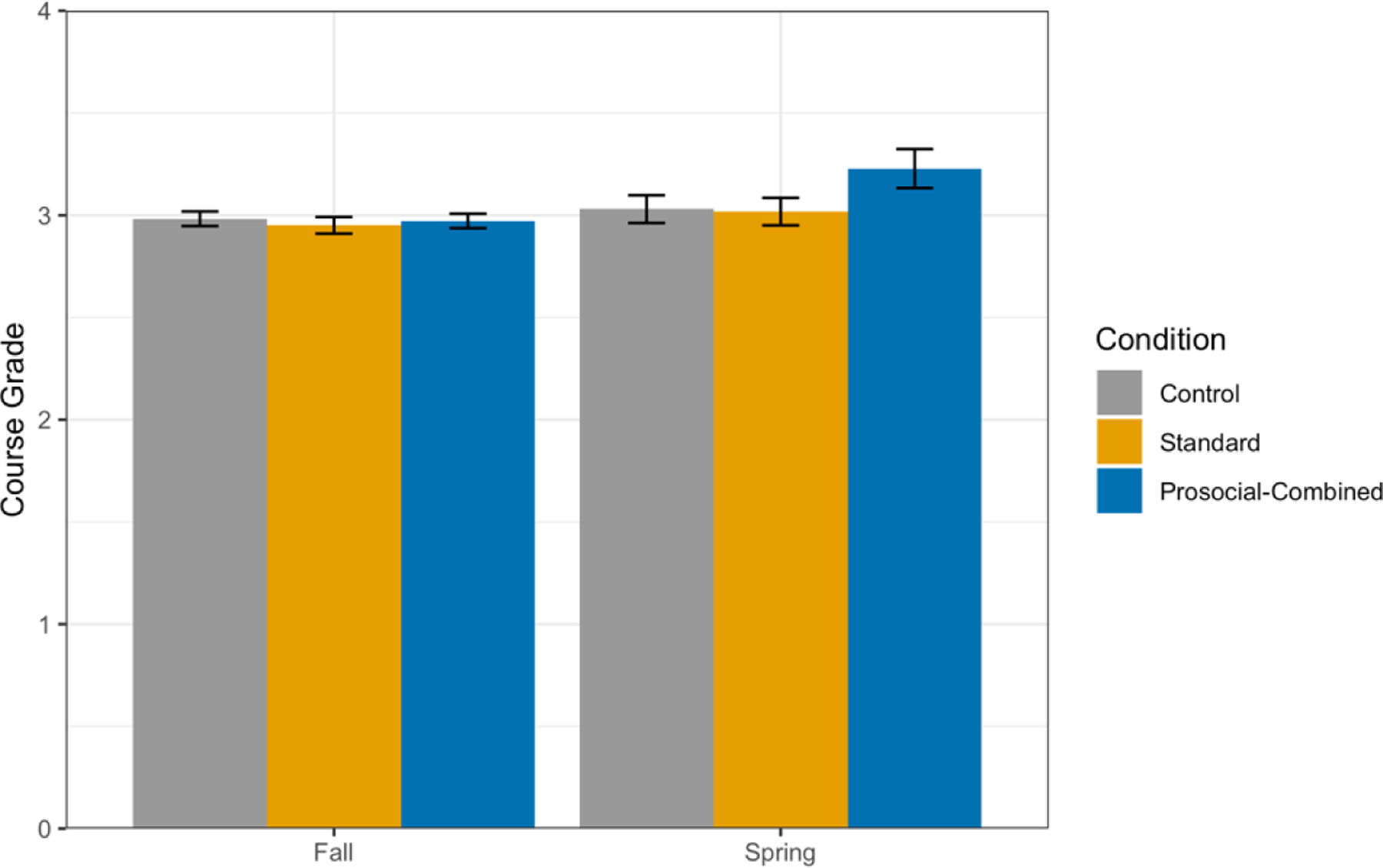

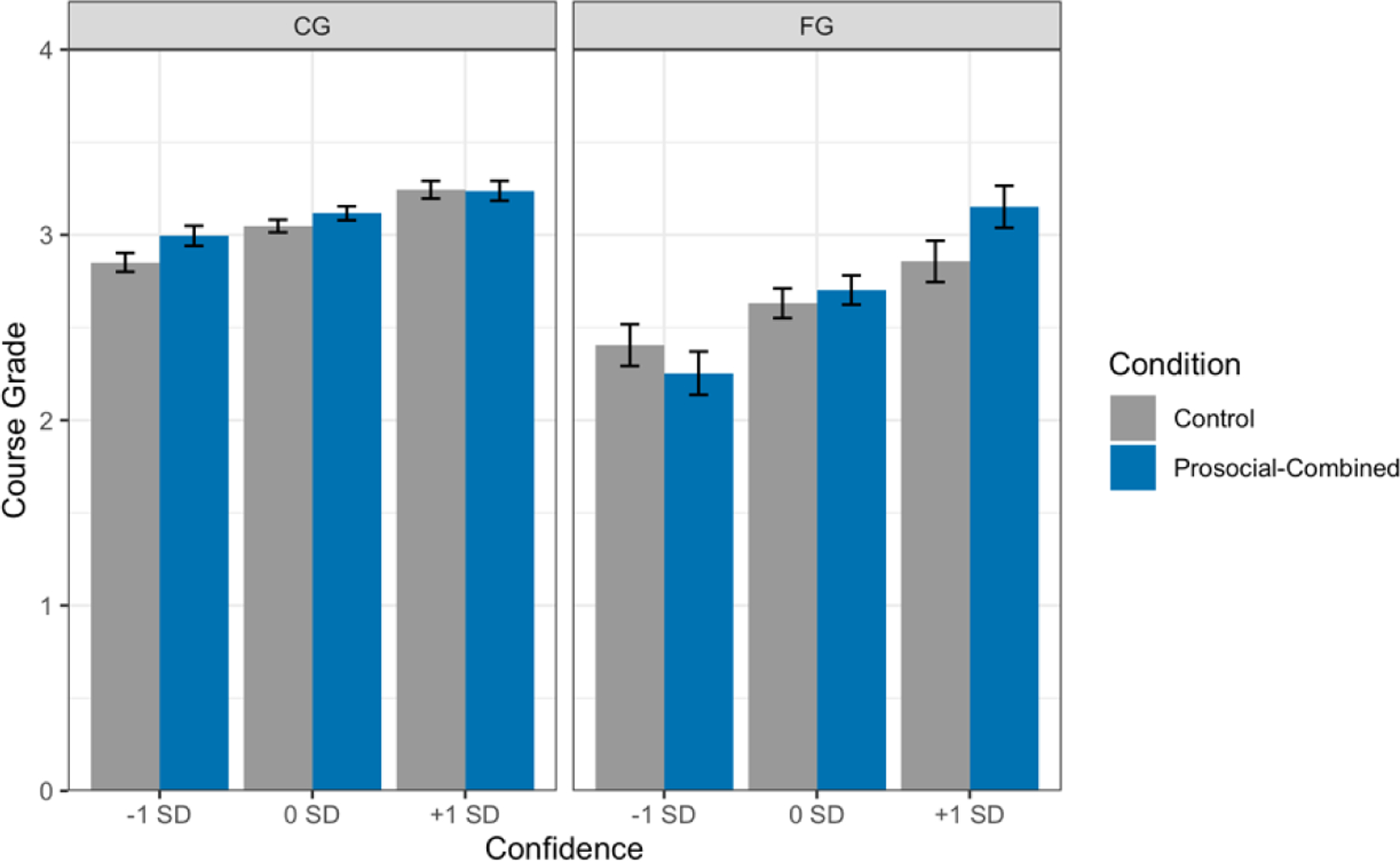

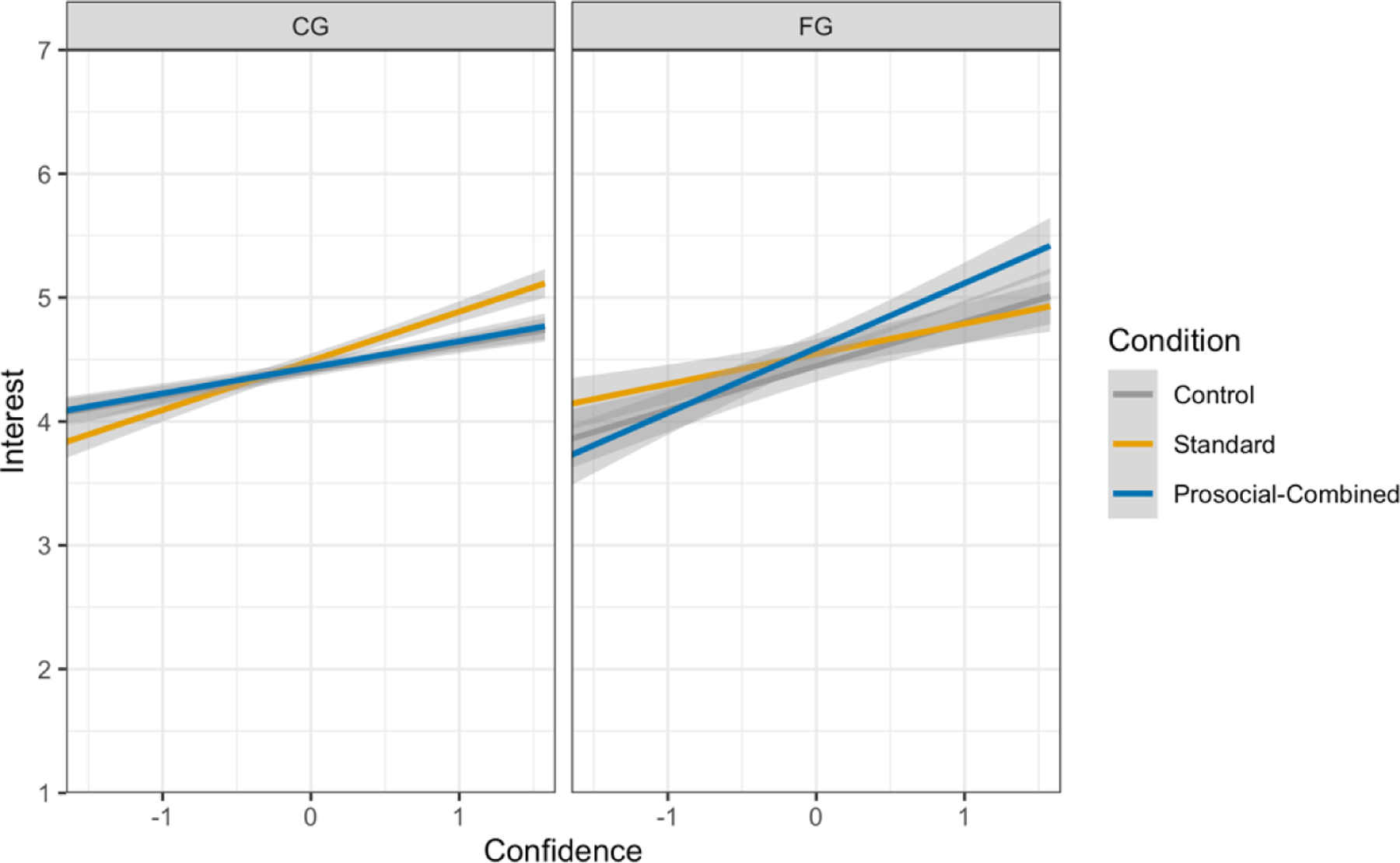

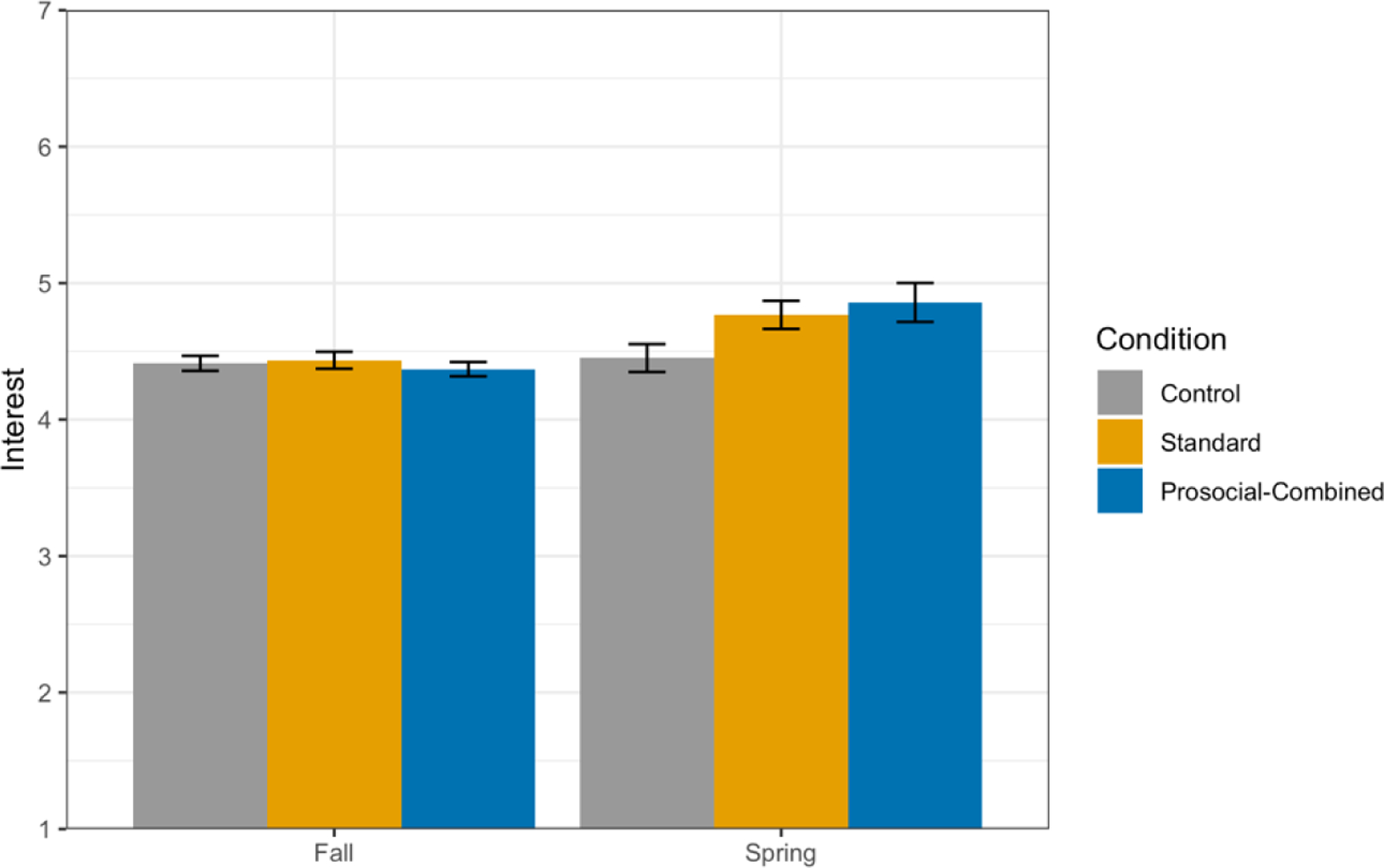

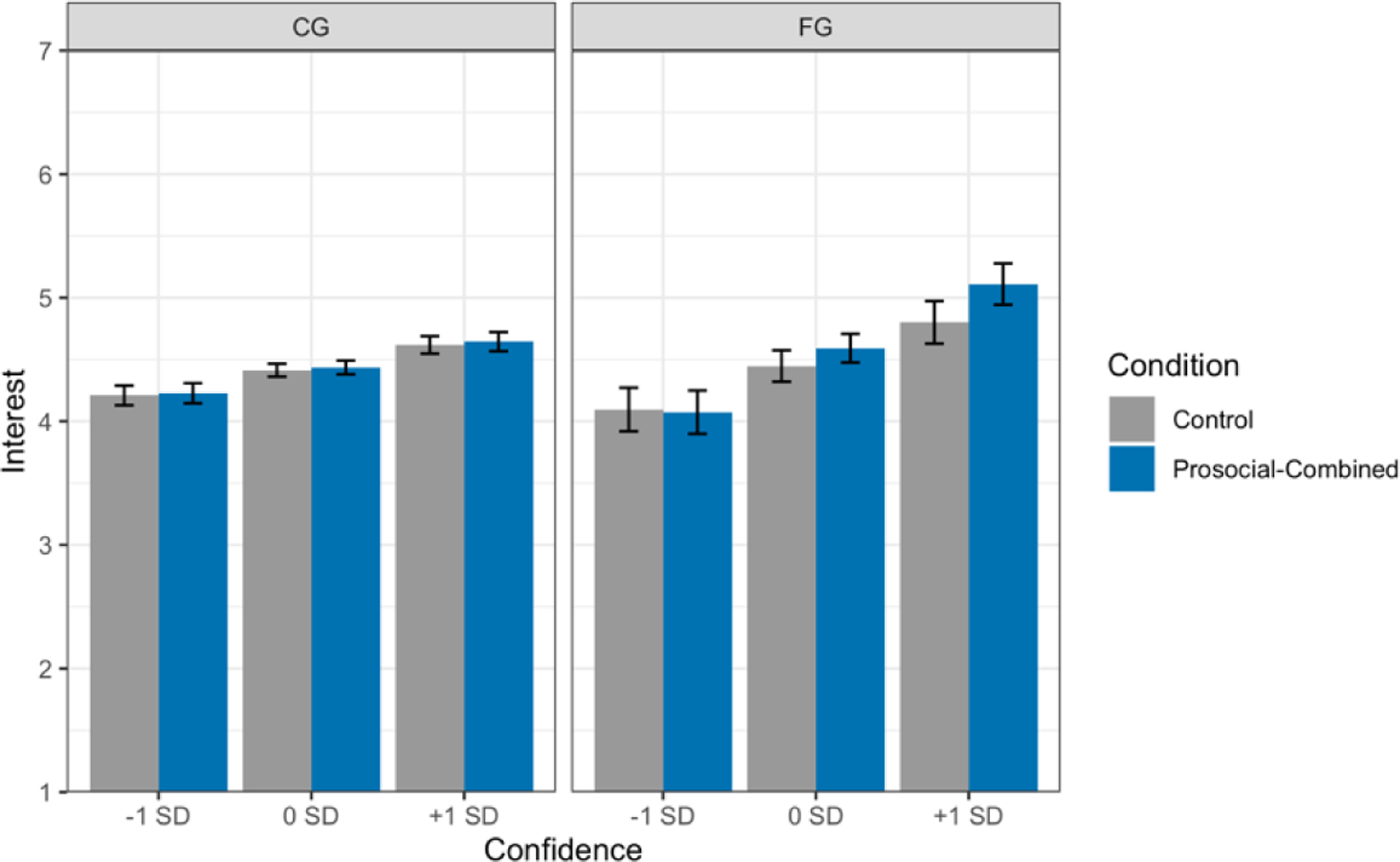

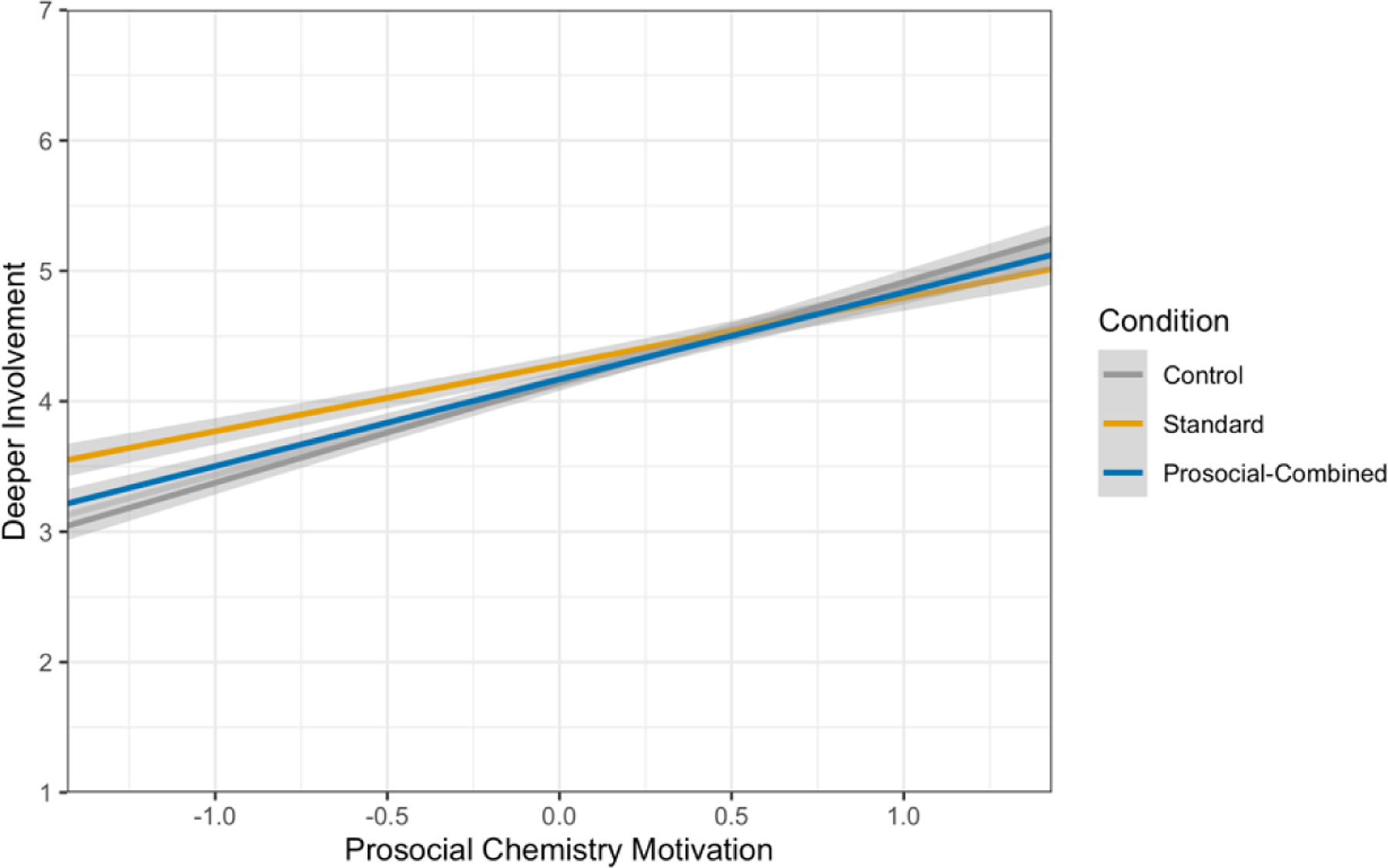

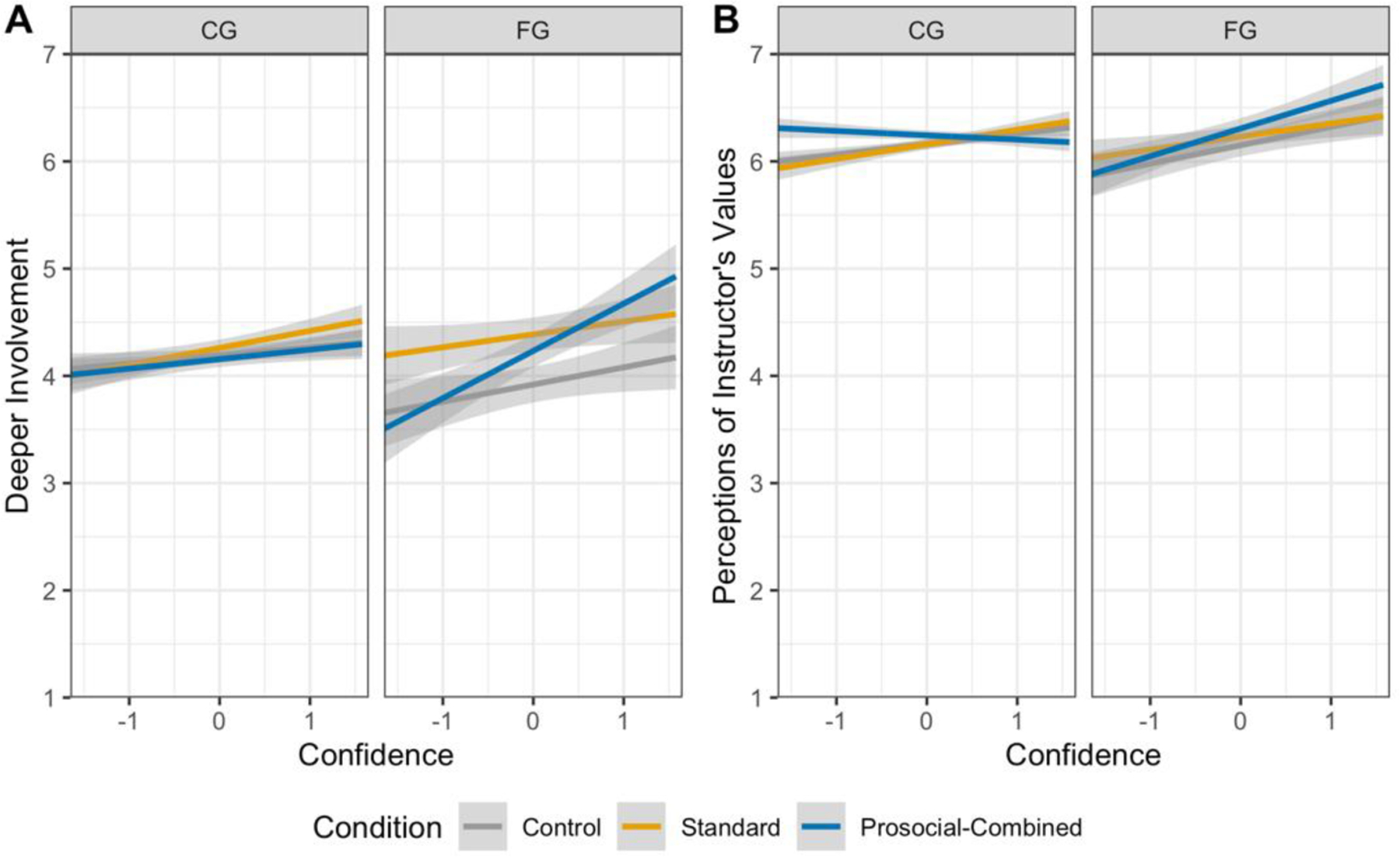

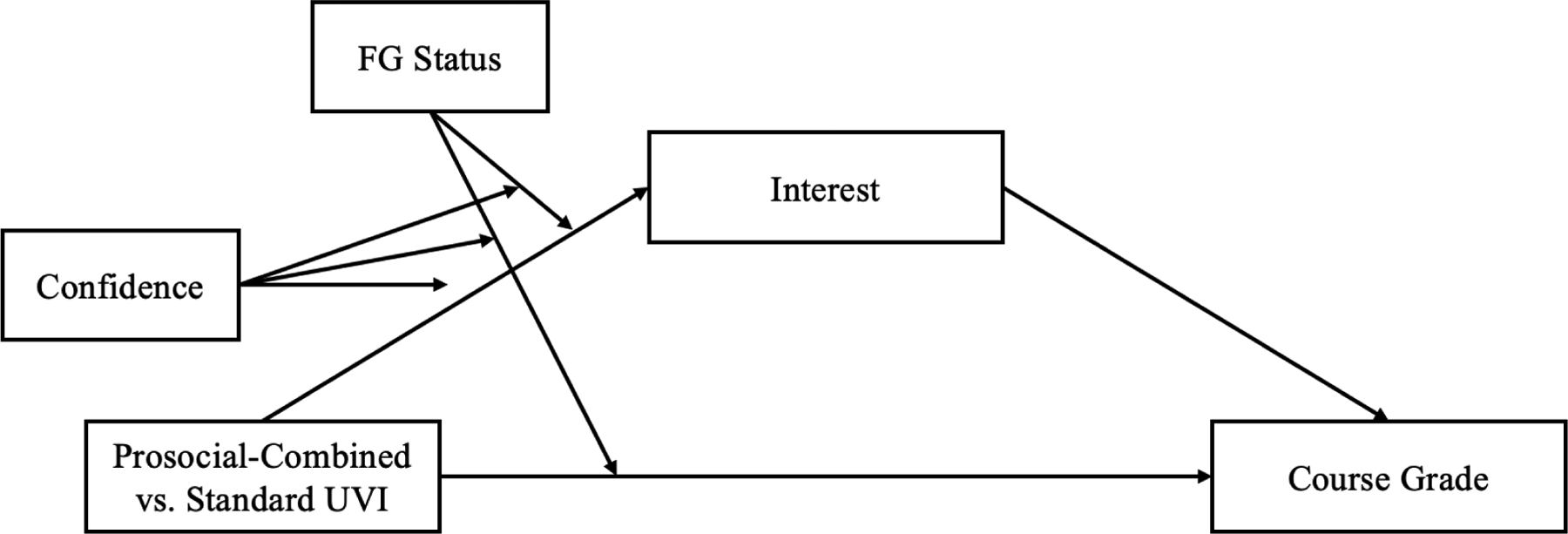

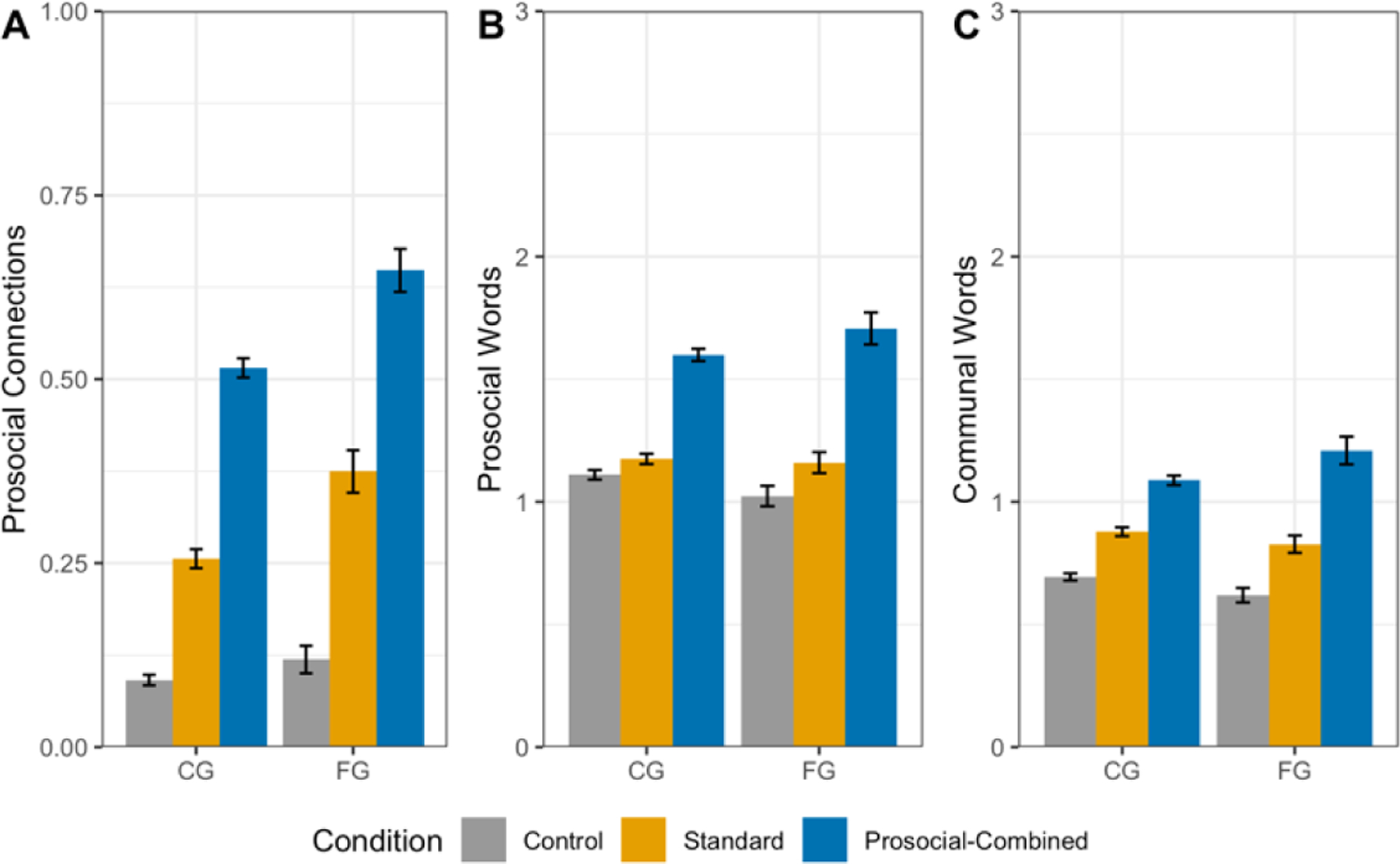

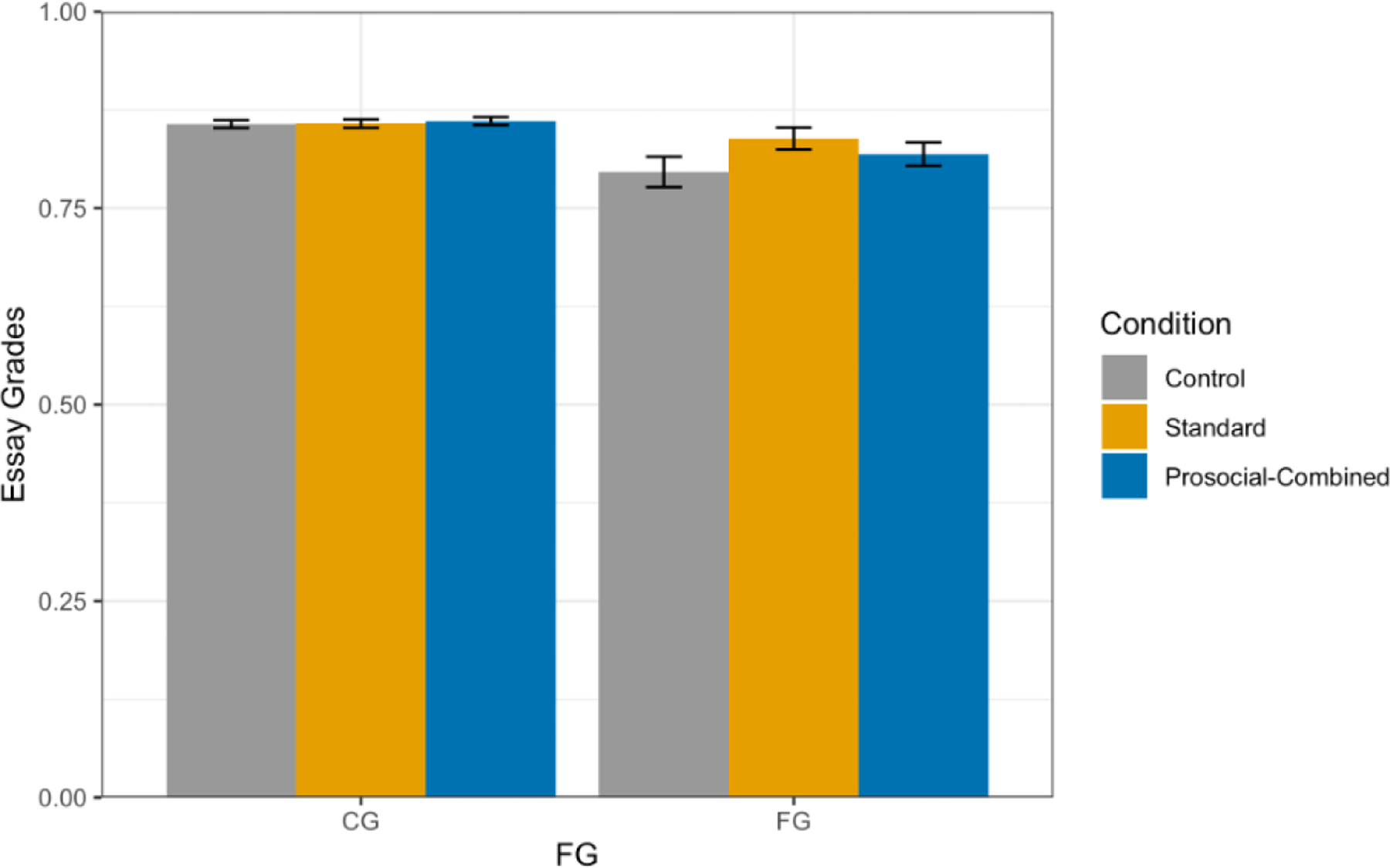

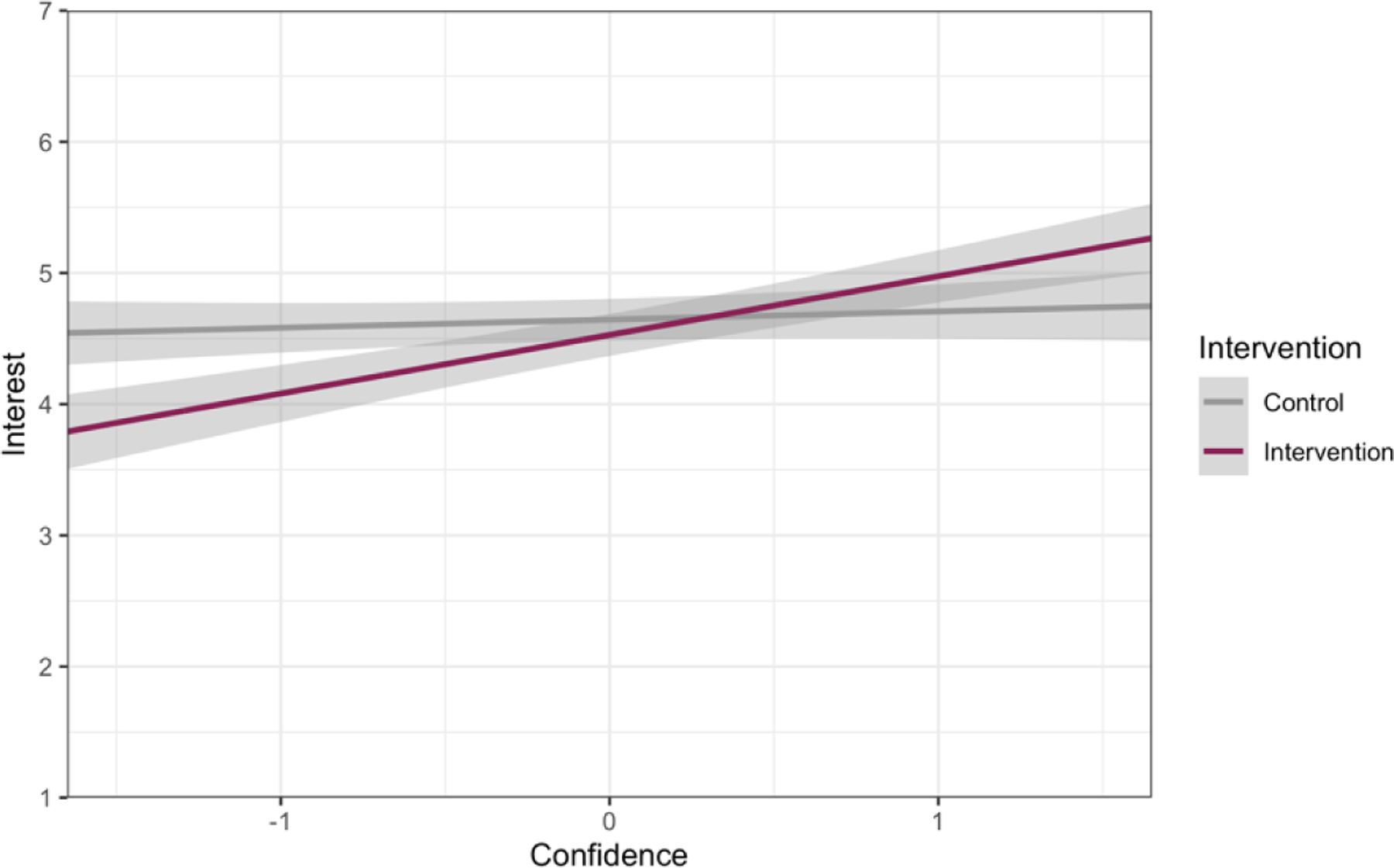

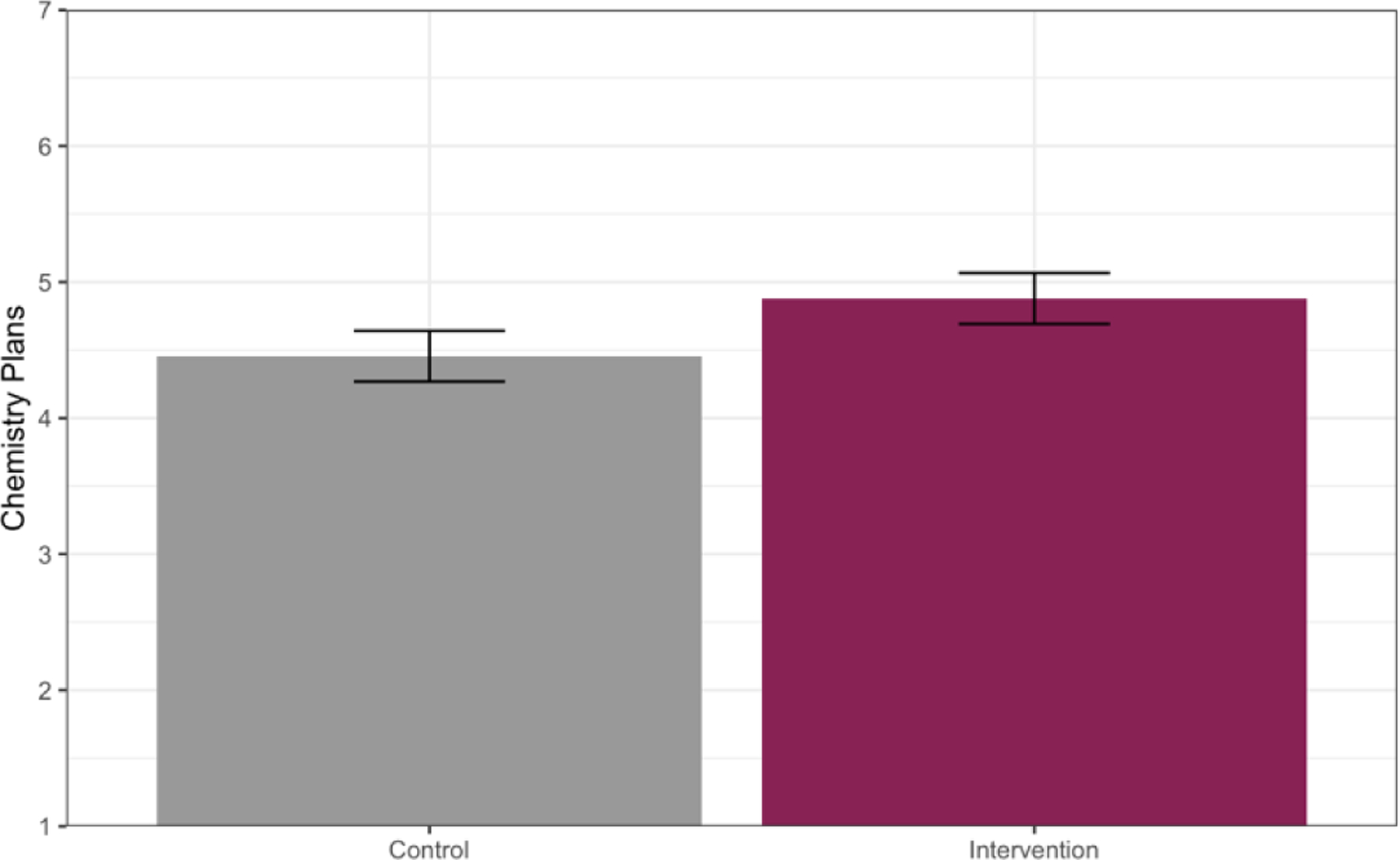

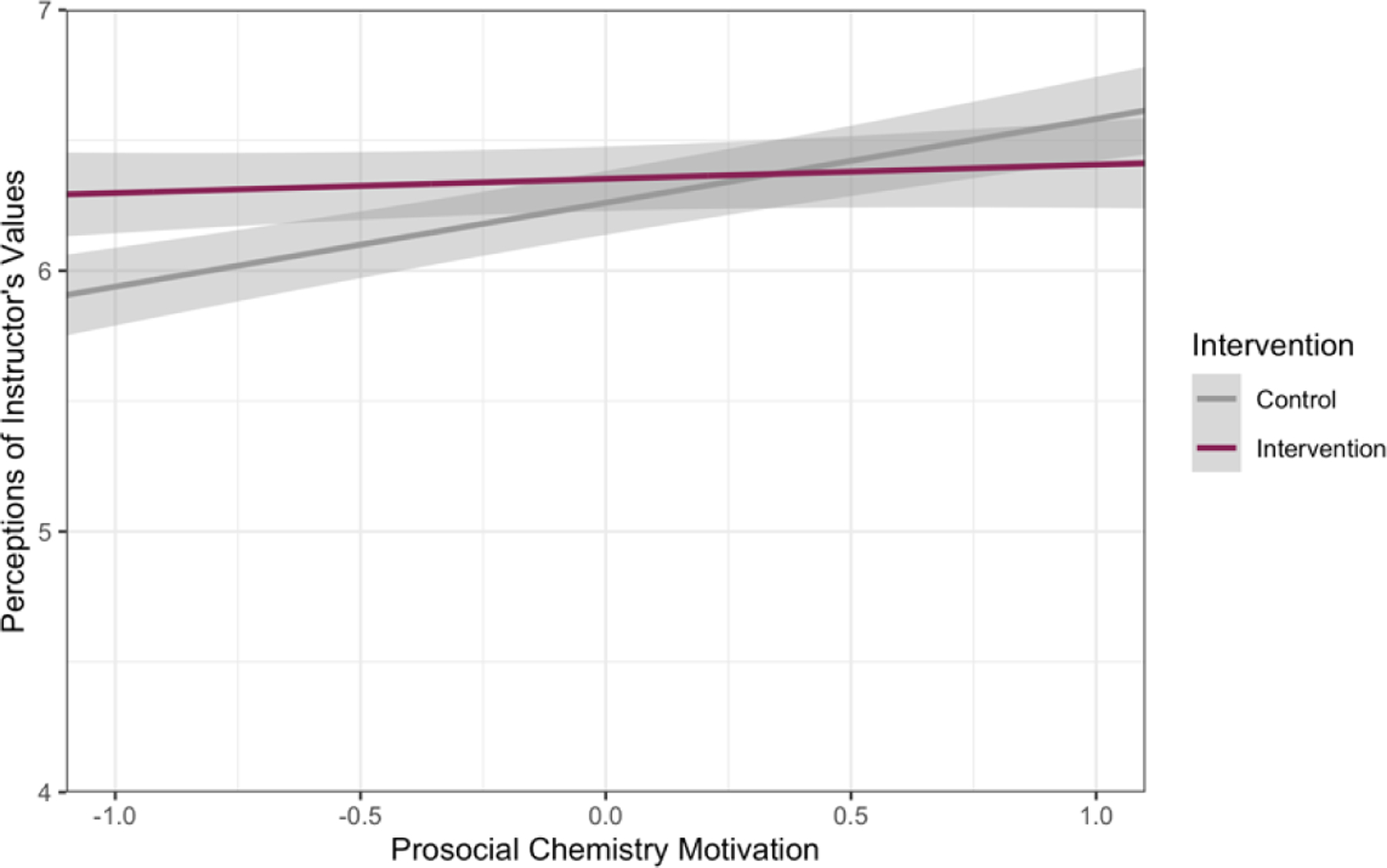

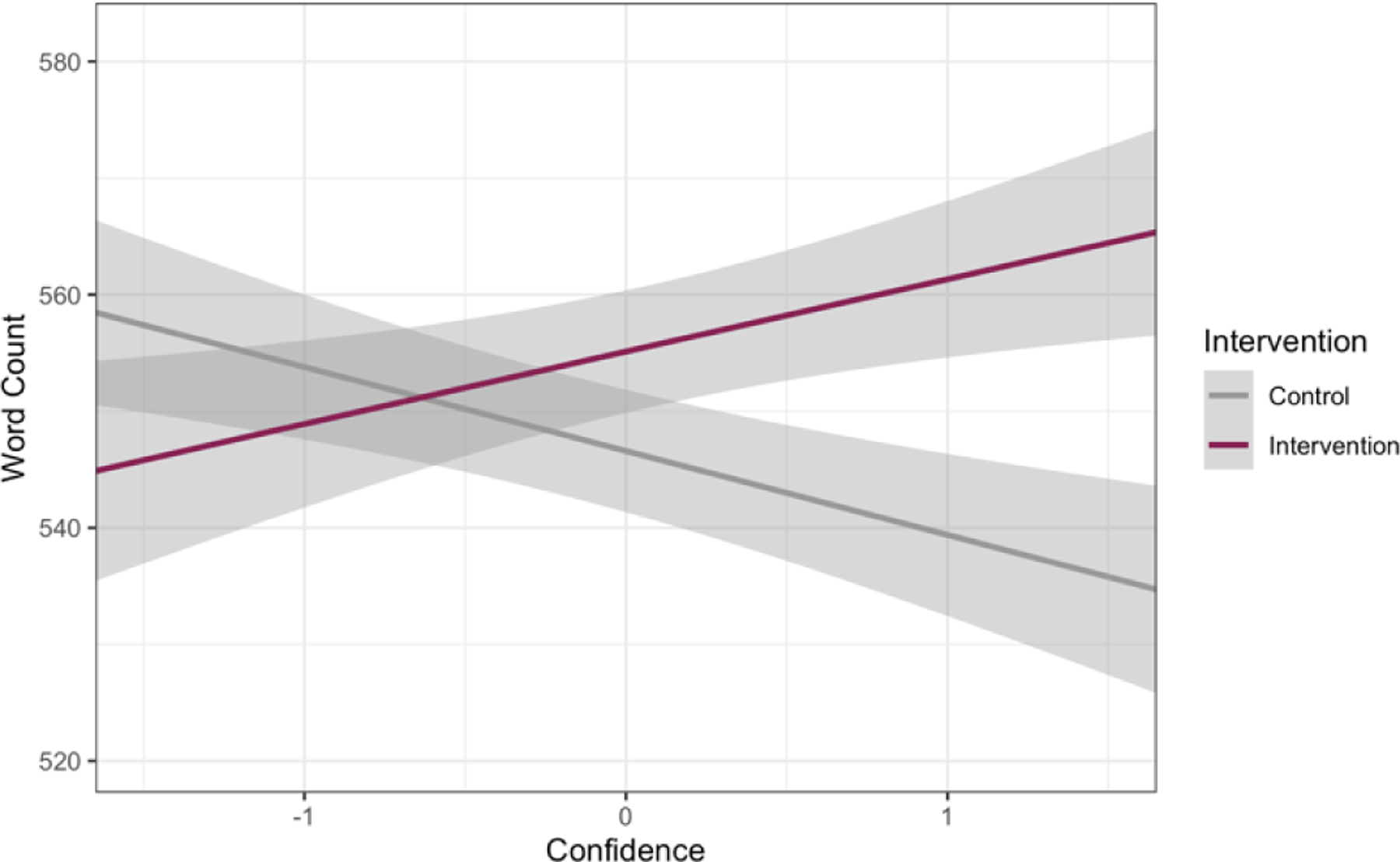

Summary of differences in student characteristics.