Abstract

This work features the use of amber suppression-mediated unnatural amino acid (UAA) incorporation into proteins for various imaging purposes. The site-specific incorporation of the UAA, p-azido-L-phenylalanine (pAzF), provides an azide handle that can be used to complete the strain promoted azide-alkyne click cycloaddition (SPAAC) reaction to introduce an imaging modality such as a fluorophore or a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer on the protein of interest (POI). Such methodology can be pursued directly in mammalian cell lines or on proteins expressed in vitro, thereby conferring a homogeneous pool of protein conjugates. A general procedure for UAA incorporation to use with a site-specific protein labeling method is provided allowing for in vitro and in vivo imaging applications based on the representative protein PTEN and αPD-L1 Fab fragment. This approach would help elucidate the cellular or in vivo biological activities of the POI.

Keywords: unnatural amino acid (UAA), site-specific protein labeling, fluorescent imaging, positron emission tomography (PET)

1. Introduction

Most protein conjugation methods target the reactive side chains of amino acids such as lysine1,2 or cysteine2. However, reliance on native moieties lacks specificity as one peptide or protein usually has multiple copies of the same amino acid residue3. This results in heterogeneous conjugate mixtures that compromise the in vitro and in vivo performance of protein conjugates as diagnostic tools or potential therapeutics2–4.

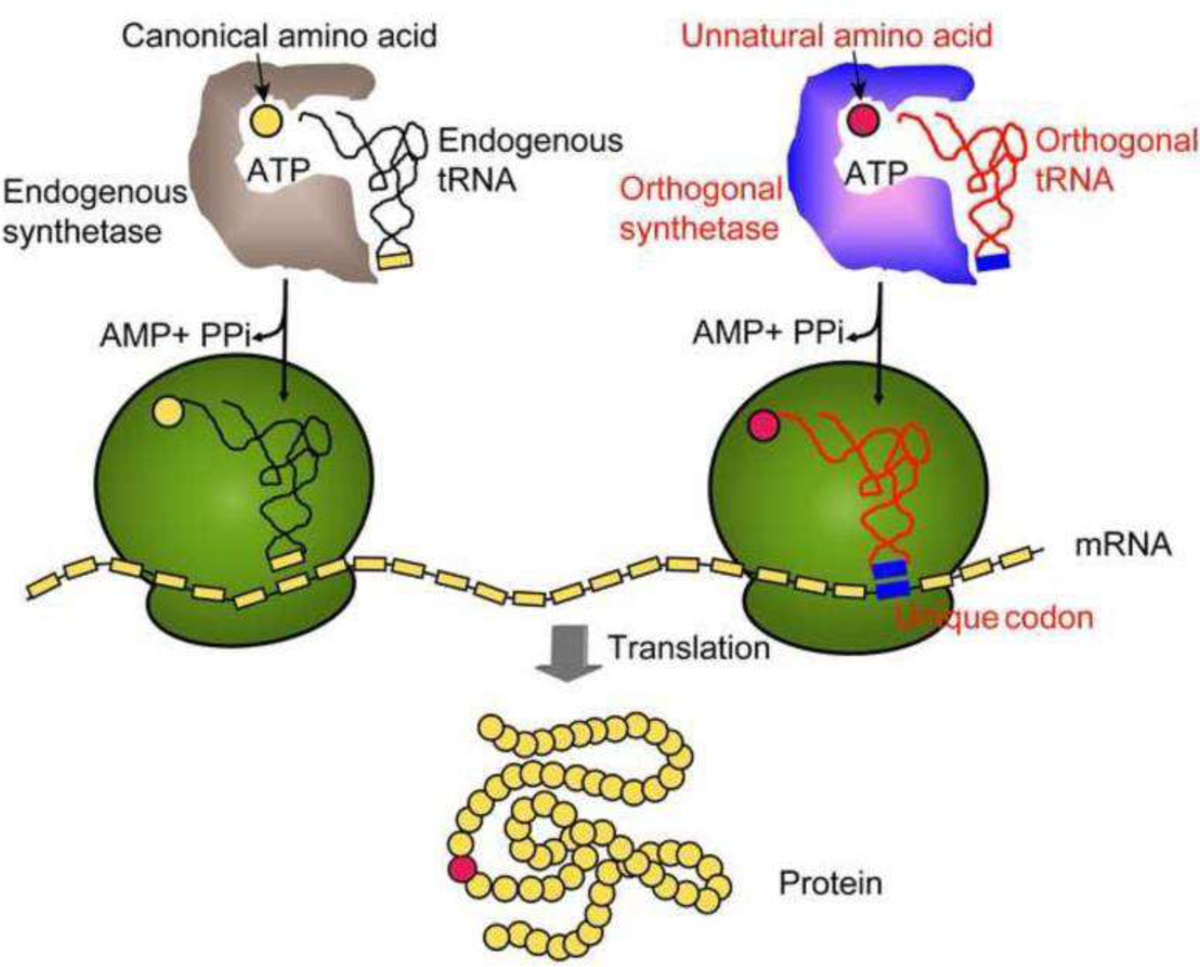

To overcome this problem, the suppression of the amber, ochre, and opal stop codons for unnatural amino acid (UAA) incorporation has become prevalent as an orthogonal and site-specific protein tagging strategy (Fig. 1)5,6. To date, over 50 different UAAs have been designed and incorporated for various purposes7. Spanning across species, the tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pairs have been evolved over the years to be functional in bacteria2,8, yeast2, mammalian cells2,5, fruit fly9,10, or C. elegans10,11. Amber suppression allows for a site-selective reaction as the UAA incorporation occurs at a specific amino acid site which has been permanently mutated in the original genetic sequence12. The stop codon can be generated through the mutation of an existing amino acid or by insertion between two existing residues in the genetic sequence anywhere within the protein. The stop codon is then charged by a tRNA/synthetase orthogonal pair designed to specifically incorporate UAAs6. Recently, the incorporation efficiency has increased as well due to the advancement of molecular biology that combines the coding fragments of tRNA/synthetase pair along with those for the required release factors within one plasmid6,13. The UAA specific release factors compete with release factor 1 in the organisms’ natural machinery to prevent amber codon recognition and terminating translation13–15.

Figure 1.

A general scheme to demonstrate the mechanism of unnatural amino acid (UAA) incorporation through amber-mediated suppression. Figure was adapted with permission from Wang,Q., Parrish,A.R., & Wang,L. (2009). Expanding the genetic code for biological studies. Chemical Biology, 16(3), 323–336. Copyright (2009) Elsevier Ltd.

As a result, UAA-based site-specific protein labeling has found great applications in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which as a homogenous pool of proteins facilitates conjugation optimization15,16 and provides additional advantages in delivery due to the superior pharmacokinetics.2,4,17 Despite these well-known applications2,4,8,15,18, few UAA-based protein conjugates have been employed for imaging studies so far19. Most often, imaging strategies have focused on the use of either fluorescent fusion proteins such as GFP20 or other protein tags such as Halo-tag21,22 and Snap-tag23 for stepwise in situ conjugation with small molecule fluorophores. As a more facile and general labeling approach, the UAA incorporation can either utilize fluorescent amino acids24 that directly fulfill the imaging purpose or amino acids with an orthogonal and specifically reactive side chain to serve as a handle for conjugation with a diverse set of fluorophores. One such representative, p-azido-L-phenylalanine (pAzF), possesses an azide group that undergoes a bio-orthogonal “click” chemistry reaction either catalyzed by copper (I) or strain- induced19,25. Due to the toxic nature of copper in live cells, the use of strain promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) has recently become more popularly utilized26.

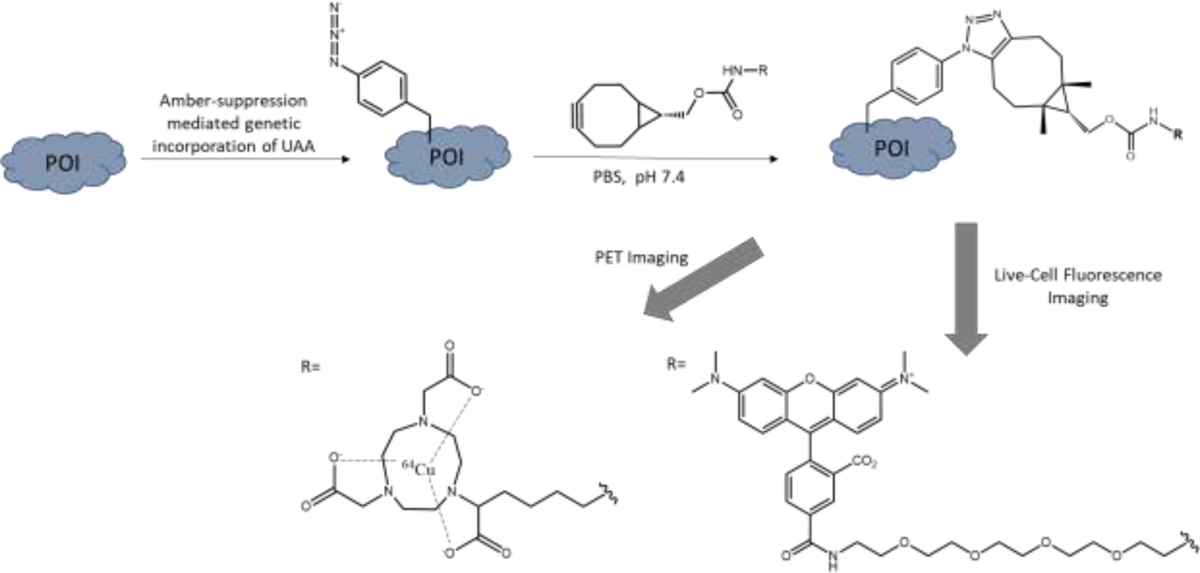

Our lab has recently developed a pAzF-based protein conjugation platform that makes use of strain-promoted SPAAC for site-specific appendence of proteins with imaging modalities derivatized by bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-yne (BCN) (Fig. 2)8,26. We further expanded on this work by fluorescently labeling a tumor suppressor protein, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), to pursue live cell tracing of PTEN’s spatiotemporal distribution. PTEN is of interest to us due to its tumor suppressor function and the various structural conformations this protein can adopt27–29. Yet, it is still greatly debated with respect to how the intracellular PTEN activity is regulated due to the many dynamic post-translational modifications it can undergo at real-time and the lack of tools available to image the intrinsically-expressed PTEN27,30. With this UAA labeling method, the location of intracellular PTEN can be identified, and further expanded on to study specific PTEN activity in the cell. For in vivo application of this technique, we turned our attention to programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which is an immune-checkpoint protein and has been closely associated with immune response evasion by tumor cells31. Despite the recent success of immunotherapies targeting these checkpoint proteins, clinical side-effects emergence suggests the potential off-target effects. Thus, technology to help image PD-L1 would significantly aid in discovering these off-target effects. We have utilized the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of an αPD-L1 antibody, which retains the strong binding affinity and allows for effective imaging. The small size of the Fab provides better tissue penetration and in vivo circulation kinetics for the imaging needs versus the full length antibody8,32. The following protocol provides details for constructing site-specific pAzF-incorporated protein conjugates first on PTEN and then on αPDL1-Fab, as well as the respective imaging applications in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2).

Figure 2:

Site-specific amber suppression on the protein of interest to incorporate p-azido-lphenylalanine (pAzF), followed by SPAAC reaction with the bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-yne (BCN) moiety of the imaging modality of choice. For PET imaging, 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N′,N″-triacetic acid (NOTA) was employed here. For fluorescent imaging, tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) was used for live-cell applications.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Molecular Cloning to Introduce TAG Codon Site-Specifically

Create a stock solution of 100 mM pAzF (Click Chemistry Tools, catalogue #1406-1G) in deionized H2O. Use concentrated NaOH to bring the pH value of the solution to ~ 9–10 to ensure full solubility of pAzF. Store the stock solution at −20°C until needed.

2.1.1. Preparation of Protein Expression Plasmids

For most proteins of interest, the related expression plasmids can be either obtained directly from Addgene or constructed through fusion-based PCR assembly. For PTEN, the mammalian expression plasmid pcDNA3 was directly obtained from Addgene (plasmid #78777)33 (Fig. 3B). For αPD-L1 Fab antibody fragment, the coding sequence was synthesized by IDT based on previously published results34. The sequence was then cloned into the E. coli expression plasmid pBAD with restriction enzymes (NheI, ApaI) and T4-ligase mediated ligation (New England Biolabs (NEB)).

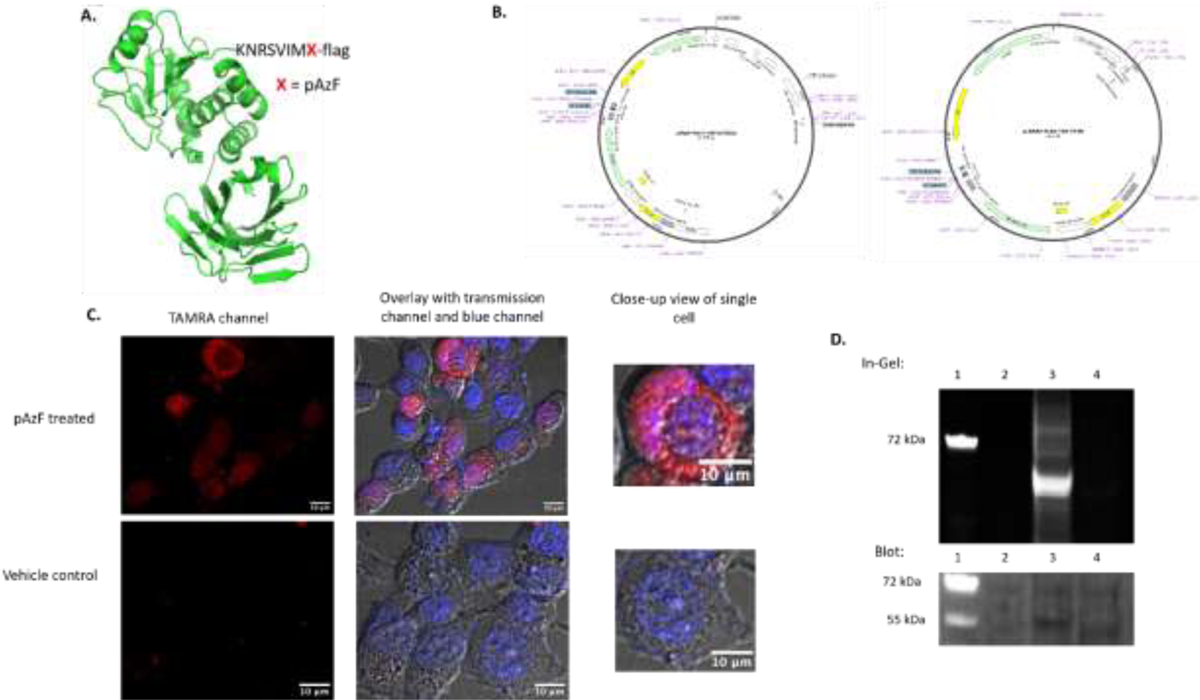

Figure 3.

(A) PTEN protein structure (PDB 1D5R) created via Pymol, with the site of UAA indicated by X in the sequence. (B) The Plasmid vector maps for PTEN and the vector for tRNA/synthetase. (C) Live-cell imaging results with the first row showing cells having received pAzF treatment, with TAMRA fluorescence. The second row was a vehicle control without pAzF treatment, which displayed no discernible fluorescence as the lack of pAzF prevented amber suppression. The transmission channel confirms the presence of fluorescence within the HEK293 cells, and the blue channel indicates Hoechst nuclear staining. (D) The SDS-PAGE based in-gel fluorescence detection of TAMRA labeling and the western blot detection of PTEN protein. The lanes are marked as: 1. Ladder; 2. Untransfected HEK293 cells; 3. Transfected HEK293 cells with the treatment of pAzF; 4. Vehicle control using transfected HEK293 cells but without pAzF treatment.

The pair of orthogonal tRNA synthetase/tRNA is usually introduced into the cellular synthetic machinery for incorporation of the desired unnatural amino acid through a separate coding plasmid for expression in E. coli or mammalian cells. For incorporation of the unnatural amino acid pAzF into PTEN in mammalian cells, we acquired the pMAH vector (as a gift from the Ai lab)35. This enables the expression of a polyspecific aminoacyl-tRNA tyrosyl synthetase with Y37I/D182S/F183M/D265R mutations and four copies of amber suppression tRNAs for pAzF incorporation (Fig. 3B). For charging pAzF onto αPD-L1 protein in E. coli, we constructed a pULTRA plasmid4,8 that encodes the tRNA/archaea Methanococcus jannaschii tyrosyl aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pair which was optimized to aminoacylate pAzF in the prokaryotic system.

2.1.2. Site-Directed Mutagenesis to Introduce Amber Codon

The TAG mutation can be introduced in through a PCR primer and would be facilitated through commercially available kits such as Q5 (NEB), QuikChange (Agilent), or In-Fusion (Takara Bio). The following steps are exemplified with the use of Q5-directed mutagenesis (NEB).

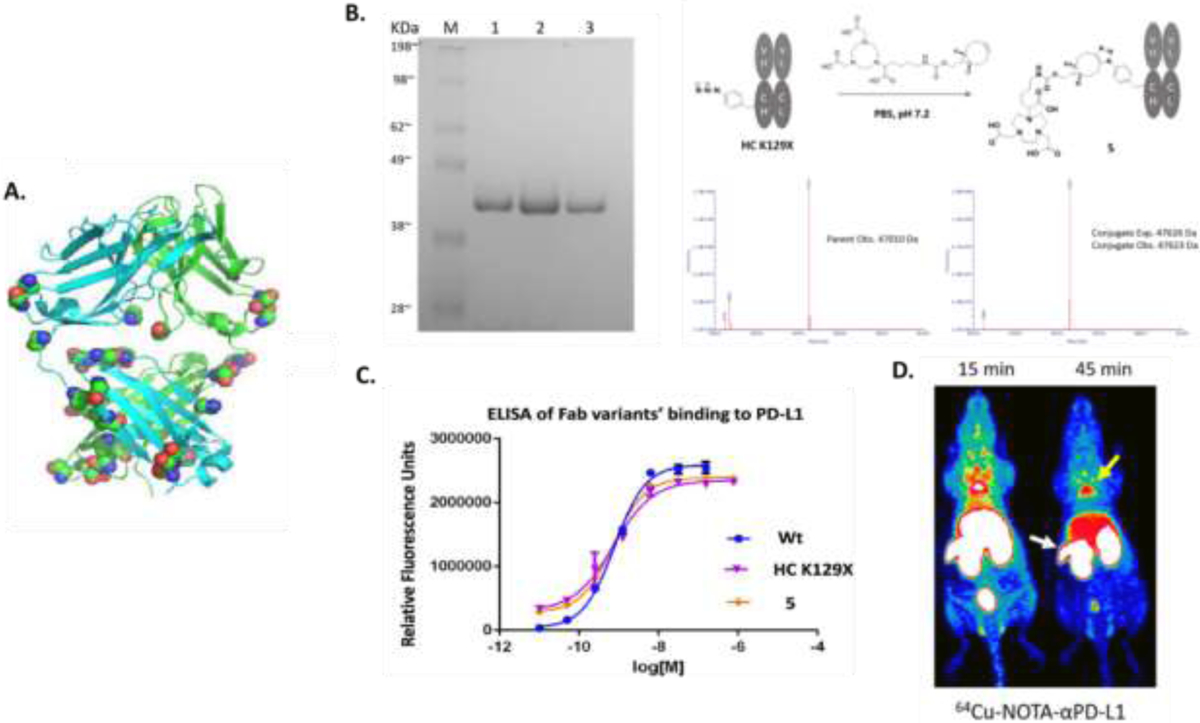

To introduce the TAG codon mutation, non-overlapping DNA primers were designed using NEBasechanger (NEB) to replace the targeted mutation site with the TAG codon. Specifically, the phenylalanine in the linker sequence between PTEN and the N-terminal FLAG tag was chosen for a test expression (Fig. 3A). Whereas for αPD-L1, the heavy chain HC_K129 was mutated to minimize protein folding disruption, as revealed by in silico screening8 (Fig. 4A).

- Set up PCR using a T100™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) with the following conditions as optimized from NEB Site-directed Mutagenesis procedure:

Denaturation: 98°C for 30 seconds Annealing: 25 cycles, 98°C for 10 seconds 60°C for 30 seconds (αPD-L1) or 67°C for 30 seconds (PTEN) 72°C for 4 minutes Extension: 72°C for 2 minutes To remove the unmutated parent vectors, add 1 μL of the PCR product to a total volume of 10 μL master mix (5 μL total of 2x Kinase, Ligase, and Dpn1 (KLD) Reaction Buffer; 1 μL 10x KLD Enzyme Mix, 3 μL Nuclease-free Water). Mix well and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

Transform the KLD treated DNA into NEB 5-alpha competent cells (catalogue #C2987H) through chemical heat-shock transformation. Add 5 μL of KLD mix to thawed cells and incubate on ice for 30 minutes. Heat shock the cells at 42°C for 30 seconds, and place back on ice for 5 minutes.

Add 950 μL of SOC media (NEB, catalogue #B9020S) to cells to help with their recovery. Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 60 minutes while shaking at 250 rpm. Plate 100 μL of these cells evenly onto an LB agar plate that was pre-treated with Ampicillin (VWR, catalogue #IC19014825). Incubate the plate overnight at 37°C.

Pick the colonies from the agar plate and inoculate in 10 mL of culture media treated with Ampicillin. Grow cultures overnight at 37°C. Extract the plasmids using a ZymoPURE II Plasmid Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, catalogue #D4210). Verify the correct TAG codon mutation by Sanger sequencing (Azenta).

For longer storage of the plasmid-containing E. coli, mix the cell culture with 50% glycerol at 1:1 ratio and store this at −80°C as stock solutions.

For plasmids to be used for expression in mammalian cells, inoculate the related E. coli stock in at least 200 mL of LB media culture. After overnight shaking at 37°C, extract the plasmids with a ZymoPURE II Maxiprep kit (Zymo Research, catalogue #D4203) which provides the endotoxin filtration.

Figure 4.

(A) αPD-L1 protein structure with the potential mutation sites highlighted for in silico simulation. (B) In vitro PAGE gel characterization and MS characterization of protein before and after conjugation. (C) In vitro ELISA to confirm affinity was not compromised by the mutation and the conjugation. (D) In vivo PET imaging result. The white arrow is pointed to the spleen and the yellow arrow points to brown adipose tissue. Figure was adapted with permission from Wissler,H.L., Ehlerding,E.B., Lyu,Z., Zhao,Y., Zhang,S., Eshraghi,A., et al. (2019). Site-specific immuno-PET tracer to image PD-L1, Molecular Pharmaceutics, 16, 2028—2036. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society

2.2. Protein Expression in E. coli or Mammalian Cells with Site-Specific UAA Incorporation

Here, we showcase the pAzF incorporation into proteins expressed by both prokaryotic (pBAD for αPD-L1) and eukaryotic systems (pcDNA3 for PTEN). For proteins expressed in E. coli, we will also introduce follow-up purification procedures. For purification of UAA-containing protein agents expressed in mammalian cells, particularly antibodies, there are reported protocols on the use of HEK293 or CHO cells for scaled up production of UAA-incorporated proteins17,36. In this work, we will focus on live mammalian cell labeling and imaging suitable for most academic labs.

2.2.1. E. coli Expression

Inoculate the E. coli stock with the desired plasmids in 8 mL of 2x YT media that contains 100 μg/mL ampicillin (for pBAD) (VWR, catalogue IC19014825) and 100 μg/mL spectinomycin (for pULTRA) (Fisher Sci, catalogue J61820-06). Incubate the solution by shaking at 37 °C, 250 rpm overnight. Notably, 2xYT media was found by us and other colleagues to particularly facilitate the expression of proteins incorporating UAAs compared to other medium.

Dilute the starter culture in 800 mL of 2x YT media containing the same concentrations of antibiotics and 1 mM pAzF and continue to shake at 37 °C, 250 rpm.

After 2–3 hours begin to check the OD600 detected on a Cell Density Meter. Once the OD600 reading reaches 0.8 – 1.0, induce the culture with 0.2% L-arabinose to activate expression of the pULTRA plasmid and 0.5 mM IPTG (Combi-Blocks, catalogue #SS-7533) to stimulate expression of the pBAD vector. Incubate the mixture for 24 hours at 18°C, 200 rpm to allow for maximum expression.

Harvest the cells by centrifuging at 4°C and 4000 × g for 30 minutes. Discard the supernatant and freeze the cell pellets at −80°C for at least three hours. Briefly thaw and resuspend the pellets using a periplasmic lysis buffer (20% sucrose, 30 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2 mg/mL lysozyme). Mix all the components by pipetting up and down. The suspension is then incubated at 37°C, 250 rpm for 20 minutes to allow for complete lysis.

Pellet insoluble debris by centrifuging at 4°C, 4000 × g for 30 minutes. Once finished, the supernatant is filtered through a 2.0 μm membrane to remove any remaining debris.

Purify the Fab proteins from the cell lysates by passing through a CH1 affinity column (Thermo Fisher, catalogue #1943462005) and eluting the proteins out with an elution buffer of 100 mM glycine, pH 2.8. Neutralize the eluent immediately with 1M Tris Buffer. Confirm the correct Fab identities and purity using SDS-PAGE and LC-MS.

2.2.2. Mammalian Cell Expression

Seed HEK293 cells at 50–70% confluency into an eight-well chambered cover glass (Cellvis C8-1.5P) at a dilution of 80,000–100,000 cells/well in DMEM (Fisher Sci, catalogue #MT10013CV) supplemented with Corning® 10% fetal bovine serum (VWR, catalogue #45000-736) and 1x Antibiotic/Antimycotic Solution (AAS) (Fisher Sci, catalogue #SV3007901) for a final volume of 150 μL in each well.

Incubate the plated cells overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to allow attachment to the plate.

Perform transfection of HEK293T cells using Xfect Transfection Reagent (Takara Bio, catalogue #631318) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with final DNA amount of 0.4 μg each for the pcDNA3-FLAG-TAG-PTEN and pMAH-POLY-eRF1 (E55D) plasmids per well. The transfected cells were incubated again at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6–8 hours to allow for maximum transfection efficiency.

Dilute the 100 mM pAzF stock in supplemented DMEM to a final concentration of 2 mM. After 6 hours, replace the existing media in each transfected well with 100 μL of fresh pAzF-containing DMEM. Incubate for another 16–24 hours for sufficient pAzF incorporation.

2.3. Individual Applications for Imaging

The azide side chain of pAzF site-specifically incorporated on PTEN (N terminal) ((Fig. 3A) and αPD-L1 Fab antibody (HC-K129 site) (Fig. 4A) can now undergo the SPAAC reaction. The reaction introduces a fluorophore TAMRA onto PTEN for live cell fluorescent imaging observation, which is aimed at elucidating the protein’s cellular location. Such bioorthogonal reaction also occurs on αPD-L1 Fab in vitro to empower its radioactive function which is needed for in vivo immunoconjugate-based positron emission tomography (immune-PET) imaging of mice (Fig. 4D).

2.3.1. In Situ Protein Labeling for Mammalian Cell Imaging (Fig. 3C–3D)

With the treated 8-well plate from section 2.2.2. step 4, add 100 μL of 1 μM endo-BCN-PEG2-TAMRA linker (BroadPharm, catalogue #BP-24286) to complete the SPAAC-mediated labeling on PTEN expressed inside HEK293 cells.

Incubate the well plate for a minimum of 30 minutes to allow for maximum labeling. Remove solution from wells and wash away excess linker from the wells using PBS (VWR, catalogue #45000-434).

Add 100 μL 1x Hoechst dye (Fisher Sci, catalogue #H1399) to each well and let it incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. Remove the solution from wells and replace with a final 100 μL PBS for imaging.

Image cells using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus) equipped with a 60x objective. Observe the nuclear staining by Hoechst under excitation 392 nm/emission 440 nm. The TAMRA-labeled PTEN was monitored under excitation 552 nm/emission 558 nm (Fig. 3C). Image processing was completed using ImageJ software.

To further verify the proper UAA incorporation and labeling of PTEN by TAMRA, additional in vitro assays can be performed. The TAMRA-labeled PTEN cellular samples prepared as listed above can be lysed with cell lysates analyzed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The TAMRA fluorescence coupled with western blotting was used to detect the expression of the mutated PTEN in HEK239 cells and to confirm the labeling by TAMRA (Fig. 3D).

-

5a.SDS-PAGE In-Gel Fluorescence

-

5a.1.Prepare TAMRA-labeled PTEN as stated in sections 2.2.2 and 2.3.1 and scale up to 106 HEK293 cells in a 6-well plate with a final well volume of 2 mL to ensure protein overexpression. With the TakraBio Xfect transfection kit, use a DNA concentration of 2 μg per plasmid. The remaining concentrations and steps stay the same.

-

5a.2.After 30 min BCN-TAMRA incubations, wash cells once with PBS. Add 200 μL mammalian protein extraction reagent (VWR, catalogue #P168501) with protease inhibitor to each well and shake at 4°C for 20 minutes.

-

5a.3.Collect lysed cells and centrifuge at 10,000 g for 10 minutes. Remove supernatant containing extracted proteins and keep on ice to prepare samples for SDS-PAGE gel.

-

5a.4.Use a BCA assay to determine protein concentration of each sample. Prepare samples containing 60 μg protein mixed with 1x LDS sample buffer (Fisher Sci, catalogue #B0007) and DTT (Ambeed, catalogue #A587635). Boil samples at 90°C for 10 minutes. Load onto SurePAGE™, Bis-Tris, 10×8, 4–12% gel (GeneScript, catalogue #M00653) and run at 140V for 40 minutes.

-

5a.5.Once finished, image gel with a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (BioRad) with the rhodamine setting.

-

5a.1.

-

5b.Western Blotting for PTEN Detection

-

5b.1.Activate a blotting membrane (Fisher Sci, catalogue #45-004-110) with 100% methanol immersion for 30 seconds. Place the membrane within two pieces of western blotting filter paper (Fisher Sci, catalogue #PI88620) and soak in 1x NuPAGE™ transfer buffer (Fisher Sci, catalogue #NP00061) for 5 minutes. Set up the transfer with the gel ran in steps 5a using a TransBlot SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (BioRad) set at 20 V for 1 hour.

-

5b.2.Remove the membrane from transfer cell and place it in 5% BSA blocking buffer with constant shaking for 1–2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

-

5b.3.Incubate the blocked membrane for 1 hour with the anti-PTEN primary antibody (Biolegend, catalogue #655002) that was 1:500 diluted in 5% BSA. Wash the membrane 3x with 0.05% tween containing PBS (PBST) for 10 minutes each time.

-

5b.4.Incubate the membrane for 1 hour with the complementary secondary antibody anti-mouse Alexa Fluor488 (Invitrogen, catalogue #S34253) that was diluted 1:2000 in 5% BSA. Wash the membrane 3x with PBST for 10 minutes each time. Image the final membrane with the same ChemiDoc MP imaging system on the Alexa488 setting.

-

5b.1.

2.3.2. Protein Conjugation and Radiolabeling for In vivo PET Imaging (Fig. 4B)

The previously expressed Fab fragments from section 2.2.2 were buffer exchanged using an Amicon filter (Sigma Aldrich, catalogue #UFC801008) and concentrated to 2.5 mg/mL (0.50 mM) in PBS buffer. Mix and incubate the protein solution with 500 μM NOTA-BCN at 4°C for 12 hours for complete SPAAC conjugation.

Purify the antibody-conjugate using the size-exclusion column on FPLC or through a Zeba-spin desalting column (VWR, catalogue #P189883) for a minimum of two rounds using PBS as the equilibrium buffer. Reconfirm antibody-conjugate identities and purities via LC-MS and SDS-PAGE analysis. The affinity of mutated or conjugated αPD-L1 towards PD-L1 fusion protein was tested via traditional ELISA assay and was comparable to that of wild-type αPD-L1 antibody.

The NOTA-αPD-L1 conjugate was radiolabeled and purified using 64CuCl2 as previously reported4,8.

Mice (Crl: NU (NCr)-Foxn1nu, Envigo) used for PET imaging were purchased at age 4–6 weeks old (Jackson Labs) and sorted n=3 per group. PET scans were acquired at time points of 15 minutes and 45 minutes respectively using an Inveon microPET/CT scanner.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Live-Cell Imaging of PTEN

The SPAAC conjugation of TAMRA dye towards the N-terminal pAzF expressed on PTEN was efficiently achieved with the observation of clear red fluorescence in live HEK293 cell images (Fig 3C). After carrying out the same set of SPAAC conjugation, we did not observe any red fluorescence from the control cell samples which had been transfected with the same set of plasmids but not treated with pAzF (Fig. 3C). The high cell permeability of TAMRA molecules also resulted in small speckles in the control wells. However, this background was negligible compared to the significant signal in the treated wells. The additional characterization with the cell lysates verified the TAMRA labeling was specific to the amber-suppressed PTEN (Fig. 3D). The in-gel fluorescence assay revealed the presence of TAMRA only in the lane that received pAzF treatment and not in the vehicle control lane. A follow-up western blotting assay further confirmed that the TAMRA fluorescent band observed in the fluorescent channel corresponds to the protein band PTEN (Fig. 3D).

Furthermore, PTEN has been previously found to be expressed in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of mammalian cells27,37. Hoechst stain was used to ensure proper nucleus identification here. As shown in Figure 3C, the TAMRA fluorescence can be seen throughout the cellular space surrounding the nucleus indicating the cytoplasmic location of PTEN. There is also overlap with the Hoechst nuclear staining indicating that some PTEN may either reside or translocate in the nucleus as well. We demonstrated that this protein labeling method can be used to study PTEN’s cellular location and probe its function based on spatiotemporal distribution. In addition, the existence of PTEN as a homodimer was documented but under studied29 and it is possible that the percentage of PTEN dimerization could be dependent on its subcellular distributions as well, which remains to be revealed by this UAA-based live cell imaging.

3.2. PET Imaging of PD-L1

The initial mutation site on this antibody Fab fragment was revealed through in silico screening using the RosettaBackrub algorithm and was determined to be HC-K129 (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the predicted stability, the Fab mutant fragment yield remained significant after UAA incorporation. The wild-type αPD-L1 Fab had a yield of 4.2 mg/L and the Fab mutant had an expression yield of 2.5 mg/L8. After complete construction and SPAAC conjugation, the αPD-L1 conjugates were confirmed to be stable and withstood little to no effect on their binding properties (Fig. 4C)8. The corresponding PET imaging revealed that the Fab fragments provide a higher clearance rate from organs along with lesser nonspecific levels of radiolabeled fragments remaining in nontargeted locations (Fig. 4D). In vivo application of the radiolabeled conjugates suggested the expression of PD-L1 immune checkpoint in the spleen and brown adipose tissues (BAT) (Fig 4D)8. The finding of the expression of PD-L1 in the spleen was consistent with other reports, which suggested that PD-L1 expression could occur in secondary lymphatic organs and not only extralymphatic organs, as was previously regarded to be the primary expression site. This finding further indicates the expression of PD-L1 may be utilized by the mentioned organs in suppressing unwanted T-cell responses, as such the spleen and adipose tissue8. Finally, the PET imaging results also show the spleen and BAT tissues as the off targets of immune checkpoint antibodies could be the partial cause of the clinically observed immunotherapeutic toxicity.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have developed an imaging platform using site-specific protein labeling based on amber suppression-mediated genetic incorporation of UAA. We demonstrated the applications on representative proteins of interest, PTEN and αPD-L1, respectively. Notably, in silico simulation was shown to be a facile method to select the optimal incorporation site, in the case of site-specific labeling of αPD-L1, which can be potentially extended to all future proteins of interest. The successfully incorporated pAzF unnatural tag served as the handle or an anchoring point to flexibly react with different imaging modalities, with the help of the bioorthogonal SPAAC reaction either happening in vitro or in situ in mammalian cells. With respect to the biological discoveries, live-cell fluorescent imaging of PTEN through this method enabled the real time tracking of PTEN’s cellular location, affirming the previous findings of this specific protein’s cellular behaviors while opening the door to more future discoveries regarding PTEN’s spatiotemporal dynamics. The in vivo PET imaging with αPD-L1-Fab on the other hand revealed PD-L1’s unexpected distribution on secondary lymphatic organs, which along with the level uncovered on adipose tissues may help elucidate the mysterious clinical toxicities observed for the current cancer immunotherapy.

Highlights.

Proteins of interest such as PTEN and αPD-L1 can be site-specifically labeled or conjugated using amber-suppression mediated genetic incorporation of unnatural amino acid (UAA).

Human PTEN intracellular activity can be tracked using UAA-based fluorescent imaging.

The in vivo biodistribution of the immune checkpoint protein PD-L1 can be mapped using UAA-based positron emission tomography (PET).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (grant #15-175-22 to R.E.W.), the National Cancer Institute of the National Institute of Health (NIH) under Award Number P30 CA006927 (to R.E.W.), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under Award R35GM133468 (to R.E.W.). Funding support by the National Science Foundation (CHE-2144075) is greatly appreciated. Rongsheng E. Wang is a Cottrell Scholar of Research Corporation for Science Advancement, and Parmila Kafley acknowledges the support from the Diversity Supplement Award from NIH under Award Number 3R35GM133468-04S1. The pMAH vector for the mammalian synthetase of pAzF is a generous gift from Dr. Huiwang Ai’s lab.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests

Data Availability

Data is available upon request

References

- (1).Kim E; Koo H Biomedical Applications of Copper-Free Click Chemistry: In Vitro, in Vivo, and Ex Vivo. Chem. Sci 2019, 10 (34), 7835–7851. 10.1039/C9SC03368H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lieser RM; Yur D; Sullivan MO; Chen W Site-Specific Bioconjugation Approaches for Enhanced Delivery of Protein Therapeutics and Protein Drug Carriers. Bioconjug. Chem 2020, 31 (10), 2272–2282. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kim CH; Axup JY; Schultz PG Protein Conjugation with Genetically Encoded Unnatural Amino Acids. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2013, 17 (3), 412–419. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Lyu Z; Kang L; Buuh ZY; Jiang D; McGuth JC; Du J; Wissler HL; Cai W; Wang RE A Switchable Site-Specific Antibody Conjugate. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (5).Schmied WH; Elsässer SJ; Uttamapinant C; Chin JW Efficient Multisite Unnatural Amino Acid Incorporation in Mammalian Cells via Optimized Pyrrolysyl TRNA Synthetase/TRNA Expression and Engineered ERF1. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (44), 15577–15583. 10.1021/ja5069728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Guo J; Melançon III CE; Lee HS; Groff D; Schultz PG Evolution of Amber Suppressor TRNAs for Efficient Bacterial Production of Proteins Containing Nonnatural Amino Acids. Angew. Chem 2009, 121 (48), 9312–9315. 10.1002/ange.200904035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Young TS; Schultz PG Beyond the Canonical 20 Amino Acids: Expanding the Genetic Lexicon*. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285 (15), 11039–11044. 10.1074/jbc.R109.091306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wissler HL; Ehlerding EB; Lyu Z; Zhao Y; Zhang S; Eshraghi A; Buuh ZY; McGuth JC; Guan Y; Engle JW; Bartlett SJ; Voelz VA; Cai W; Wang RE Site-Specific Immuno-PET Tracer to Image PD-L1. Mol. Pharm 2019, 16 (5), 2028–2036. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bianco A; Townsley FM; Greiss S; Lang K; Chin JW Expanding the Genetic Code of Drosophila Melanogaster. Nat. Chem. Biol 2012, 8 (9), 748–750. 10.1038/nchembio.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Brown W; Liu J; Deiters A Genetic Code Expansion in Animals. ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13 (9), 2375–2386. 10.1021/acschembio.8b00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Parrish AR; She X; Xiang Z; Coin I; Shen Z; Briggs SP; Dillin A; Wang L Expanding the Genetic Code of Caenorhabditis Elegans Using Bacterial Aminoacyl-TRNA Synthetase/TRNA Pairs. ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7 (7), 1292–1302. 10.1021/cb200542j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Pott M; Schmidt MJ; Summerer D Evolved Sequence Contexts for Highly Efficient Amber Suppression with Noncanonical Amino Acids. ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 9 (12), 2815–2822. 10.1021/cb5006273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Takimoto, J. K; Adams, K. L; Xiang Z; Wang L Improving Orthogonal TRNA - Synthetase Recognition for Efficient Unnatural Amino Acid Incorporation and Application in Mammalian Cells. Mol. Biosyst 2009, 5 (9), 931–934. 10.1039/B904228H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kwok HS; Vargas-Rodriguez O; Melnikov SV; Söll D Engineered Aminoacyl-TRNA Synthetases with Improved Selectivity toward Noncanonical Amino Acids. ACS Chem. Biol 2019, 14 (4), 603–612. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yin G; Stephenson HT; Yang J; Li X; Armstrong SM; Heibeck TH; Tran C; Masikat MR; Zhou S; Stafford RL; Yam AY; Lee J; Steiner AR; Gill A; Penta K; Pollitt S; Baliga R; Murray CJ; Thanos CD; McEvoy LM; Sato AK; Hallam TJ RF1 Attenuation Enables Efficient Non-Natural Amino Acid Incorporation for Production of Homogeneous Antibody Drug Conjugates. Sci. Rep 2017, 7 (1), 3026. 10.1038/s41598-017-03192-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kim CH; Axup JY; Dubrovska A; Kazane SA; Hutchins BA; Wold ED; Smider VV; Schultz PG Synthesis of Bispecific Antibodies Using Genetically Encoded Unnatural Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (24), 9918–9921. 10.1021/ja303904e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Axup JY; Bajjuri KM; Ritland M; Hutchins BM; Kim CH; Kazane SA; Halder R; Forsyth JS; Santidrian AF; Stafin K; Lu Y; Tran H; Seller AJ; Biroc SL; Szydlik A; Pinkstaff JK; Tian F; Sinha SC; Felding-Habermann B; Smider VV; Schultz PG Synthesis of Site-Specific Antibody-Drug Conjugates Using Unnatural Amino Acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2012, 109 (40), 16101–16106. 10.1073/pnas.1211023109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Garidel P; Hegyi M; Bassarab S; Weichel M A Rapid, Sensitive and Economical Assessment of Monoclonal Antibody Conformational Stability by Intrinsic Tryptophan Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Biotechnol. J 2008, 3 (9–10), 1201–1211. 10.1002/biot.200800091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Beatty KE; Fisk JD; Smart BP; Lu YY; Szychowski J; Hangauer MJ; Baskin JM; Bertozzi CR; Tirrell DA Live-Cell Imaging of Cellular Proteins by a Strain-Promoted Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition. ChemBioChem 2010, 11 (15), 2092–2095. 10.1002/cbic.201000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hirano M; Ando R; Shimozono S; Sugiyama M; Takeda N; Kurokawa H; Deguchi R; Endo K; Haga K; Takai-Todaka R; Inaura S; Matsumura Y; Hama H; Okada Y; Fujiwara T; Morimoto T; Katayama K; Miyawaki A A Highly Photostable and Bright Green Fluorescent Protein. Nat. Biotechnol 2022, 40 (7), 1132–1142. 10.1038/s41587-022-01278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Los GV; Encell LP; McDougall MG; Hartzell DD; Karassina N; Zimprich C; Wood MG; Learish R; Ohana RF; Urh M; Simpson D; Mendez J; Zimmerman K; Otto P; Vidugiris G; Zhu J; Darzins A; Klaubert DH; Bulleit RF; Wood KV HaloTag: A Novel Protein Labeling Technology for Cell Imaging and Protein Analysis. ACS Chem. Biol 2008, 3 (6), 373–382. 10.1021/cb800025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Murrey HE; Judkins JC; am Ende CW; Ballard TE; Fang Y; Riccardi K; Di L; Guilmette ER; Schwartz JW; Fox JM; Johnson DS Systematic Evaluation of Bioorthogonal Reactions in Live Cells with Clickable HaloTag Ligands: Implications for Intracellular Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (35), 11461–11475. 10.1021/jacs.5b06847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bosch PJ; Corrêa IR; Sonntag MH; Ibach J; Brunsveld L; Kanger JS; Subramaniam V Evaluation of Fluorophores to Label SNAP-Tag Fused Proteins for Multicolor Single-Molecule Tracking Microscopy in Live Cells. Biophys. J 2014, 107 (4), 803–814. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pantoja R; Rodriguez EA; Dibas MI; Dougherty DA; Lester HA Single-Molecule Imaging of a Fluorescent Unnatural Amino Acid Incorporated Into Nicotinic Receptors. Biophys. J 2009, 96 (1), 226–237. 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Baskin JM; Prescher JA; Laughlin ST; Agard NJ; Chang PV; Miller IA; Lo A; Codelli JA; Bertozzi CR Copper-Free Click Chemistry for Dynamic in Vivo Imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2007, 104 (43), 16793–16797. 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lang K; Davis L; Wallace S; Mahesh M; Cox DJ; Blackman ML; Fox JM; Chin JW Genetic Encoding of Bicyclononynes and Trans-Cyclooctenes for Site-Specific Protein Labeling in Vitro and in Live Mammalian Cells via Rapid Fluorogenic Diels–Alder Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (25), 10317–10320. 10.1021/ja302832g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bononi A; Pinton P Study of PTEN Subcellular Localization. Methods 2015, 77–78, 92–103. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Masson GR; Williams RL Structural Mechanisms of PTEN Regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2020, 10 (3), a036152. 10.1101/cshperspect.a036152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Heinrich F; Chakravarthy S; Nanda H; Papa A; Pandolfi PP; Ross AH; Harishchandra RK; Gericke A; Lösche M The PTEN Tumor Suppressor Forms Homodimers in Solution. Struct. Lond. Engl. 1993 2015, 23 (10), 1952–1957. 10.1016/j.str.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hopkins BD; Parsons RE Molecular Pathways: Intercellular PTEN and the Potential of PTEN Restoration Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res 2014, 20 (21), 5379–5383. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Pardoll DM The Blockade of Immune Checkpoints in Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12 (4), 252–264. 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ilovich O; Natarajan A; Hori S; Sathirachinda A; Kimura R; Srinivasan A; Gebauer M; Kruip J; Focken I; Lange C; Carrez C; Sassoon I; Blanc V; Sarkar SK; Gambhir SS Development and Validation of an Immuno-PET Tracer as a Companion Diagnostic Agent for Antibody-Drug Conjugate Therapy to Target the CA6 Epitope. Radiology 2015, 276 (1), 191–198. 10.1148/radiol.15140058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lee M-S; Jeong M-H; Lee H-W; Han H-J; Ko A; Hewitt SM; Kim J-H; Chun K-H; Chung J-Y; Lee C; Cho H; Song J PI3K/AKT Activation Induces PTEN Ubiquitination and Destabilization Accelerating Tumourigenesis. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 7769. 10.1038/ncomms8769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Boyerinas B; Jochems C; Fantini M; Heery CR; Gulley JL; Tsang KY; Schlom J Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Activity of a Novel Anti-PD-L1 Antibody Avelumab (MSB0010718C) on Human Tumor Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res 2015, 3 (10), 1148–1157. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chen Z; Zhang S; Li X; Ai H A High-Performance Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Biosensor for Imaging Physiological Peroxynitrite. Cell Chem. Biol 2021, 28 (11), 1542–1553.e5. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).VanBrunt MP; Shanebeck K; Caldwell Z; Johnson J; Thompson P; Martin T; Dong H; Li G; Xu H; D’Hooge F; Masterson L; Bariola P; Tiberghien A; Ezeadi E; Williams DG; Hartley JA; Howard PW; Grabstein KH; Bowen MA; Marelli M Genetically Encoded Azide Containing Amino Acid in Mammalian Cells Enables Site-Specific Antibody–Drug Conjugates Using Click Cycloaddition Chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem 2015, 26 (11), 2249–2260. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Song MS; Salmena L; Pandolfi PP The Functions and Regulation of the PTEN Tumour Suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2012, 13 (5), 283–296. 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request