SUMMARY

Tumor microbiota can produce active metabolites that affect cancer and immune cell signaling, metabolism, and proliferation. Here, we explore tumor and gut microbiome features that affect chemoradiation response in patients with cervical cancer using a combined approach of deep microbiome sequencing, targeted bacterial culture and in vitro assays. We identify that an obligate L-lactate-producing lactic acid bacterium found in tumors, Lactobacillus iners, is associated with decreased survival in patients, induces chemotherapy and radiation resistance in cervical cancer cells, and leads to metabolic rewiring, or alterations in multiple metabolic pathways, in tumors. Genomically similar L-lactate-producing lactic acid bacteria commensal to other body sites are also significantly associated with survival in colorectal, lung, head and neck, and skin cancers. Our findings demonstrate that lactic acid bacteria in the tumor microenvironment can alter tumor metabolism and lactate signaling pathways, causing therapeutic resistance. Lactic acid bacteria could be promising therapeutic targets across cancer types.

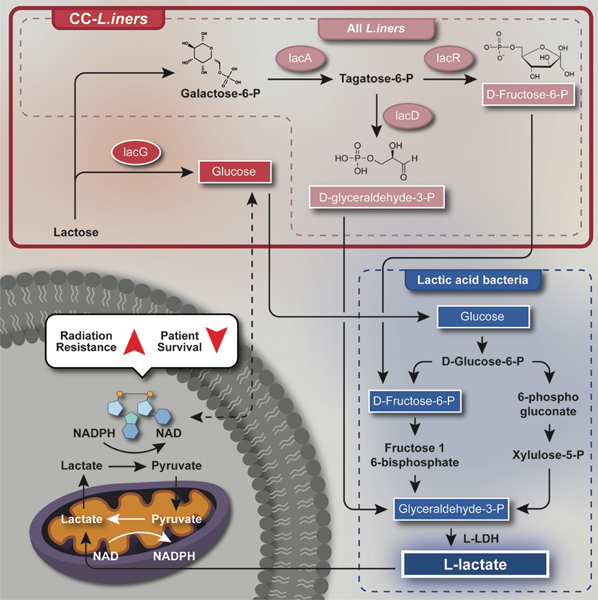

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Colbert et al. describe how tumoral Lactobacillus iners strongly predict poor chemoradiation response and survival for patients with cervical cancer. Further, L. iners, and potentially other obligate L-lactate producing Lactic acid bacteria, appear to rewire tumor metabolism and could serve as biomarkers or therapeutic targets in multiple cancer types.

INTRODUCTION

Tumors, even in allegedly sterile organs, have unique microbiomes that can modify treatment response and survival1–8. While the gut microbiome indirectly affects tumor response through systemic mechanisms, including innumerable immune9–12 and metabolism-mediated pathways13–16,17–20, tumor-resident bacteria may directly impact tumor growth, survival, and function4–7.

There are several challenges to understanding the complex mechanisms of tumor-microbiota interactions. In preclinical models, microbiome manipulation of in vivo tumor models does not reliably recapitulate changes in the human microbiome. In clinic, studies of the tumor microbiome are limited by longitudinal tumor biopsy availability, pitfalls of optimized sequencing and analysis protocols for formalin-embedded tumor samples21–26, and sequencing reference libraries. Tumor strains develop in a unique environmental niches and selective pressures, and adapt or acquire additional genes and functions necessary to survive in low nutrient, low oxygen, or low pH environments. In-depth mechanistic study of the tumor microbiome remains a significant challenge in most tumor types.

Exophytic cervical cancers develop in mucosal surfaces and are amenable to repeated tumor microbiome sampling. For this reason, we used cervical cancer and a combined deep sequencing, immune profiling, and targeted bacterial culture platform to explore the potential mechanisms of direct tumor-microbiome interactions during cancer therapy. In this study, we analyzed tumor-resident bacteria for associations with poor treatment responses in 101 patients with cervical cancer undergoing chemoradiation, enrolled in a prospective, serial biomarker collection study across two institutions (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX; Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital of Harris Health System, Houston TX). We then integrated these data with targeted culture to identify and profile the key tumor microbiota associated with treatment resistance.

RESULTS

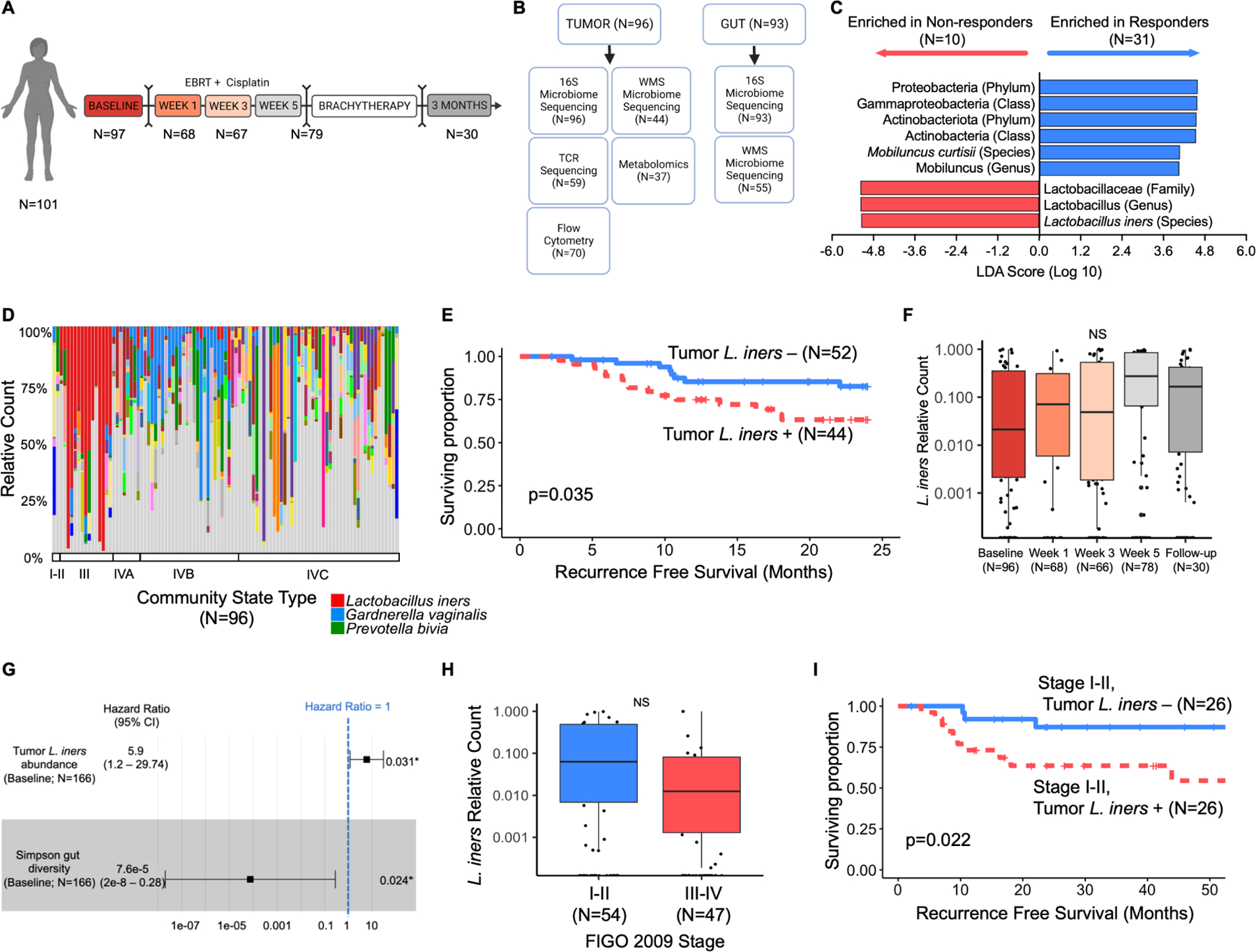

A total of 101 patients with newly diagnosed, locally advanced cervical cancer were enrolled; ninety-six patients had pre-treatment samples collected prior to standard of care treatment (CRT; 45Gy of external beam radiation therapy with weekly concurrent cisplatin at 40mg/m2 and brachytherapy) (Fig. 1A–B, Supp. Table 1). Samples were sent for 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing (16S), shotgun metagenome sequencing (SMS), T cell repertoire sequencing (TCR), and/or metabolomics (Supp. Table 2). 93 baseline gut microbiome samples were collected for 16S and/or SMS. 244 serial tumor swabs were also collected during and after treatment (1, 3 and 5 weeks of RT and 12-week follow-up).

Figure 1. Tumor-resident Lactobacillus iners is associated with decreased recurrence-free and overall survival in cervical cancer patients.

A. Study design and standard of care treatment algorithm for patients on study with number of cervical tumor swabs collected at each timepoint for 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing (16S). Patients received 5 weeks of EBRT with concurrent cisplatin followed by brachytherapy and repeat imaging for disease response at 3 months. Sampling was at baseline, Weeks 1, 3 and 5 of radiation, and at 3 month follow up.

B. Sample types collected and available for each analysis at baseline (pre-treatment). Tumor and gut samples were collected where possible from each patient at each timepoint; however, not all samples were collected or available for sequencing at each timepoint.

C. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis of 16S data from cervical tumor swabs for bacteria enriched in non-responders to radiation in a pilot cohort (N=41). Default parameters were used for LEfSe analysis with an LDA threshold of 4.0 for statistical significance and visualization.

D. 16S compositional stacked bar plots of cervical tumor swabs for all patients at baseline (N=97), sorted by vaginal community state type (CST), including L. iners (red), G. vaginalis (blue), and P. bivia (green).

E. Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival (RFS) curves stratified by presence (N=44) or absence (n=52) of tumoral L. iners. Survival curves censored at 24 months. Log-rank test for comparison. Total # of events = 33.

F. 16S relative counts of L. iners in cervical tumor swabs collected during CRT. Week 1 (N=68), week 3 (N=66), week 5 (N=78), and follow-up (N=30) compared to baseline (N=96) using paired t-tests and false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-value. Box represents interquartile range (25th to 75th), bar indicates median, whiskers represent minimum and maximum values.

G. Multivariate cox proportional hazard analysis for overall survival (OS), adjusting for gut microbiome diversity (N=90) and tumoral L. iners (N=90). Total # of events = 14. Square represents hazard ratio (HR), bars represent 95% confidence intervals on HR.

H. Baseline relative counts of L. iners stratified by tumor size (FIGO 2009 Stage I-II [N=54] vs Stage III-IV [N=47]). Unpaired t-test. NS=p>0.05. Box represents interquartile range (25th to 75th), bar indicates median, whiskers represent minimum and maximum values.

I. Kaplan-Meier RFS curves for patients with FIGO 2009 Stage I-II tumors, stratified by presence (N=26) or absence (n=26) of tumoral L. iners. Survival curves censored at 54 months. Log-rank test for comparison.

Tumor Lactobacillus iners are associated with non-response to CRT and decreased recurrence-free survival

To identify initial bacteria of interest in the tumor microbiome (tumor-resident bacteria), we first performed linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) in a pilot cohort of 43 patients using 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing data (16S) for associations with chemoradiation response. Lactobacillus iners (L. iners) was significantly associated with non-response to CRT (N=10), while Proteobacteria (phylum), Gammaproteobacteria (class), and Actinobacteriota (phylum) were associated with response to CRT (Fig. 1C; N=31; CDA score >4) in the pilot cohort. Next, we evaluated the relationship of these organisms with recurrence-free survival (RFS). Increased relative counts of tumor-resident L. iners were significantly associated with decreased RFS (RFS; Cox Proportional hazard ratio [Cox HR] 5.29 [95% CI 2.44–8.14]; log-rank p=0.0003), while Proteobacteria (phylum), Gammaproteobacteria (class), and Actinobacteriota (Phylum) were not associated with RFS in the pilot cohort (Supp. Fig. 1A–C; all p>0.05). Cervical tumor microbial diversity (Simpson, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, Fisher) evenness (Pielou), or richness (total observed features) were not associated with response or RFS (Supp. Fig. 1D–M), using both rarefied and non-rarefied data and MaAsLin2 (FDR q value=0.07, p value=0.0007). To validate the association of L. iners with RFS, we enrolled an additional 58 patients across both institutions. The presence of any tumor-resident L. iners at baseline remained significantly associated with CRT non-response. In all patients, tumoral L. iners was present in 46% of samples (Fig. 1D) and the presence of L. iners remained associated with decreased RFS (log-rank p=0.035; Fig. 1E).

In univariate analysis of all patients with baseline samples (N=96), increased relative counts of L. iners at baseline were also significantly associated with lower RFS (Table 1; Cox HR 3.7 [95% CI 1.0 – 13.3; p=0.04) and lower overall survival ([OS], Table 1; Cox HR 10.4 [95% CI 1.8 – 60.3]; p=0.009). Proteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Actinobacteriota remained unassociated with RFS or OS, as did tumor microbiome evenness, diversity, and richness (Supp. Table 3). Other clinical and demographic variables associated with shorter RFS on univariate analysis included higher FIGO 2009 stage (III-IV vs. I-II; p=0.01) and lower gut microbiome diversity (p=0.049).

Table 1.

Univariate (UV) and multivariate (MV) Cox proportional hazard models for recurrence-free and overall survival for all patients with baseline samples (N=96).

| Variable | Recurrence-free Survivala | Overall Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV | MV | UV | MVl | ||||

| pval |

HR (95%CI)b | pval | pval |

HR (95%CI) |

pval |

||

| Tumor L. Iners c | <0.01 d | 5.79 (1.98–16.95) | <0.01 | 0.02 | 8.60 (1.77–71.77) | <0.01 | |

| Institution | |||||||

| LBJe | – | – | |||||

| MDACCf | 0.29 | 0.07 | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.36 | 0.41 | |||||

| Race | |||||||

| Asian/Black/Other | – | – | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.16 | 0.99 | |||||

| White | 0.52 | 0.20 | |||||

| BMIf (kg/m2) | 0.84 | 0.40 | |||||

| Smoking Status | |||||||

| Never | – | – | |||||

| Former | 0.76 | 0.29 | |||||

| Current | 0.43 | 0.63 | |||||

| Histology | |||||||

| Non-squamousg | – | – | |||||

| Squamous | 0.68 | 0.12 | |||||

| LVSI | |||||||

| No | – | – | |||||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.86 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.57 | 0.79 | |||||

| FIGO 2009 Stage h | |||||||

| II-II | – | – | – | ||||

| III-IV | 0.01 | 2.49 (1.18–5.25) | 0.02 | 0.27 | 2.82 (0.93–8.49) | 0.07 | |

| Grade | |||||||

| Other/Unknown | – | – | |||||

| 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||||

| 2 | 0.09 | 0.22 | |||||

| 3 | 0.83 | 0.70 | |||||

| HPV Type | |||||||

| HPV 16/18 | – | – | |||||

| Negative/Other | 0.19 | 0.07 | |||||

| Cisplatin Cycles | 0.36 | 0.81 | |||||

| Radiation Dose (Gy) | 0.92 | 0.03 | |||||

| Antibiotic Use i | |||||||

| No | – | – | |||||

| Yes | 0.58 | 0.08 | |||||

| Nodal Status | |||||||

| Negative | – | – | |||||

| Positive | 0.84 | 0.99 | |||||

| Tumor Dimension (cm) | 0.51 | 0.44 | |||||

| Gut Diversity j | <0.05 | 0.03 (5.6E–05 –21.19) | 0.30 | 0.01 | |||

| Gut Evenness k | 0.18 | 0.03 | |||||

N=33 recurrence events.

Hazard Ratio and 95% Confidence interval on HR for cox proportional hazard (Cox PH) models.

Increasing relative counts in baseline (pretreatment) tumor swabs.

Bold font indicates p<0.05 variables included in multivariate Cox PH models.

Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital, Harris Health System, Houston TX.

The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX.

Adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Antibiotic use within 30 days of baseline swab collection extracted from inpatient and outpatient pharmacy and electronic medical record data, antifungals not included.

Simpson gut diversity (continuous).

Pielou’s evenness metric.

Overall survival multivariate model includes only gut diversity due to limited number of events.

Relative counts of L. iners and overall tumor microbiome diversity (Simpson, Faith, Fisher), evenness (Pielou) or overall richness (Observed features) did not change significantly during or after CRT (Fig. 1F; Supp. Fig. 2A–E).

L. iners abundance is an independent predictor of poor recurrence-free and overall survival on multivariate analysis

On multivariate (MV) Cox proportional hazard (PH) analysis for RFS in all patients, adjusting for stage and gut microbiome diversity, only higher L. iners abundance remained associated with decreased RFS (Table 1; Cox HR 5.79 [1.98–16.95]; p=0.001), as did higher FIGO stage (2.49 [1.18–5.25]; Cox PH p=0.016). Gut microbiome diversity was no longer significant (Cox PH p=0.30). Sensitivity analyses for model stability with only gut diversity and L. iners abundance confirmed L. iners was significant for RFS, while gut diversity was not. There was no difference in RFS based on relative counts of L. iners for patients with small tumors (FIGO 2009 stage I-II; N=52) versus large tumors (Fig. 1H, FIGO 2009 stage III-IV; N=47). Even in these patients, the presence of tumoral L. iners (N=26) still predicted significantly shorter RFS (Fig. 1I; 26; log-rank p=0.022).

High L. iners abundance was also significantly associated with worse OS on MV analysis (Table 1; Cox HR 12.7 [2.4–66.5]; p=0.006) when adjusted for stage (p=0.07). Independent models for L. iners adjusted for gut microbiome diversity and evenness were constructed independently due to small OS event numbers, and L. iners remained significant in both models (Fig. 1G, Gut Simpson diversity L. iners Cox HR 5.9 [95% CI 1.2–29.7]; p<0.0031; Supp. Fig. 3A, Gut Pielou evenness L. iners Cox HR 6.5 [95% CI 1.3–32.9]; p=0.024).

L. iners is not a surrogate for another gut or tumor microbe, microbial signature or clinical feature

No clinical, demographic, or gut microbiome metrics were associated with tumoral L. iners (Table 2). L. iners+ tumors had slightly lower overall tumor microbiome alpha diversity; however, diversity was not associated with RFS or OS. No other tumor or gut compositional metrics, besides gut Simpson diversity and Pielou evenness, were significantly associated with L. iners, RFS, or OS (Supp. Table 3), including gut and tumor Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, Fisher’s alpha, observed features, Shannon diversity, or Simpson evenness (all p>0.05).

Table 2.

Pathologic and clinical variables associated with the presence of tumoral L. iners (N=96).

| Tumor L. Iners Status |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | L. iners − (N=52) | L. iners + (N=44) | |||

| N (%) |

Mean (SD) |

N (%) |

Mean (SD) |

p-valuea |

|

| Institution | 0.07 | ||||

| LBJ Hospitalb | 15 (29) | 6 (14) | |||

| MDACCc | 37 (71) | 38 (86) | |||

| Age (years) | 47.1 (9) | 43.0 (11) | 0.06 | ||

| Race | 0.21 | ||||

| Black/Asian/Other | 6 (12) | 6 (14) | |||

| Hispanic | 27 (52) | 15 (34) | |||

| White | 19 (37) | 23 (52) | |||

| BMId (kg/m2) | 30.2 (6) | 28.9 (7) | 0.34 | ||

| Smoking Status | 0.61 | ||||

| Never | 32 (62) | 26 (59) | |||

| Former | 14 (27) | 15 (34) | |||

| Current | 6 (12) | 3 (7) | |||

| Histology | 0.50 | ||||

| Non-squamouse | 10 (19) | 11 (25) | |||

| Squamous | 42 (81) | 33 (75) | |||

| LVSI f | 0.80 | ||||

| No | 12 (23) | 9 (21) | |||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 4 (9) | |||

| Unknown | 37 (71) | 31 (70) | |||

| FIGO 2009 Stage g | 0.37 | ||||

| I-II | 26 (50) | 26 (59) | |||

| III-IV | 26 (50) | 18 (41) | |||

| Grade | 0.08 | ||||

| Indeterminate/ Unknown | 7 (14) | 11 (25) | |||

| 1 | 6 (12) | 1 (2) | |||

| 2 | 25 (48) | 15 (34) | |||

| 3 | 14 (27) | 17 (39) | |||

| HPV Genotype | 0.11 | ||||

| HPV 16/18 | 35 (71) | 24 (56) | |||

| Negative/Other | 14 (29) | 19 (44) | |||

| Cisplatin Cycles | 5.0 (1) | 5.0 (1) | 0.92 | ||

| Antibiotic Use h | 0.12 | ||||

| No | 36 (69) | 23 (54) | |||

| Yes | 16 (31) | 20 (47) | |||

| Nodal Status | 0.98 | ||||

| Negative/Unknown | 20 (38) | 17 (39) | |||

| Positive | 32 (62) | 27 (61) | |||

| Tumor Dimension (cm) | 5.5 (2) | 5.1 (2) | 0.38 | ||

| Faith's PDi (Gut) | 12.1 (3) | 12.7 (3) | 0.30 | ||

| Fisher's Alpha (Gut) | 20.5 (9) | 23.0 (8) | 0.17 | ||

| Observed Features (Gut) | 150.8 (61) | 166.4 (58) | 0.22 | ||

| Pielou's Evenness (Gut) | 0.7 (0) | 0.7 (0) | 0.23 | ||

| Shannon Diversity (Gut) | 5.0 (1) | 5.2 (1) | 0.15 | ||

| Simpson's Evenness (Gut) | 0.1 (0) | 0.1 (0) | 0.53 | ||

| Simpson Diversity (Gut) | 0.9 (0) | 0.9 (0) | 0.36 | ||

Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. T-test for continuous variables.

Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital, Harris Health System, Houston TX.

The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX.

Body mass index.

Adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma.

Lymphovascular space invasion.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Antibiotic use within 30 days of baseline swab collection extracted from inpatient and outpatient pharmacy and electronic medical record data, antifungals not included.

Unsupervised clustering revealed two L. iners+ clusters, co-occurring with either Gardnerella vaginalis (G. vaginalis) or Atopobium vaginae (A. vaginae), and an L. iners-cluster with Prevotella bivia (P. bivia); cluster membership did not change significantly during CRT and was not indepentently associated with outcomes (Supp. Fig. 2F–I, Supp. Fig. 2J–N, Supp. Table 3, all p>0.05).

There was also no association of overall viral, HPV-specific viral load or fungal load with presence of L. iners (Supp. Fig. 2N–P). Antibiotic use was not associated with L. iners (Table 2) or outcomes (Table 1).

Presence and abundance of L. iners in the gut was significantly associated with initial CRT response on LEfSe, in addition to Escherichia/shigella (E/shigella) (Supp. Fig. 3B), but not with RFS or OS (Supp. Fig. 3C–D; Supp. Table 3; all Cox PH and KM p>0.05). Patients with gut L. iners also had tumor L. iners: the only bacterial species in the gut enriched (LDA score ≥4) in patients with L. iners+ tumors was L. iners with no direct correlation between abundances (Supp. Fig. 3E–FG).

L. iners does not affect baseline or dynamic overall or antigen-specific T cell repertoire

In other cancers, bacteria prime immune response to standard cancer therapy and immunotherapy. To explore whether there were differences in T cell repertoire or clonal expansion in response to cancer therapy, we performed tumoral T cell repertoire at serial timepoints27 (N=199). L. iners− tumors had overall higher counts of TCR templates (8,175 vs. 14,600 t-test p=0.03; Supp. Fig. 4A), CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells (Supp. Fig. 4B, C) at baseline, suggesting higher T cell infiltration. Both L. iners+ and L. iners- tumors had a decrease during CRT in productive clonality and overall templates (Supp. Fig. 4D–I), L. iners – tumors rebounded slightly earlier at the end of treatment and by week 12; We identified no differences in serial clonal TCR repertoire or motifs (Supp. Fig. 4), or in clonal expansion of HPV-specific TCRs (Supp. Fig. 4U). T cell recognition and expansion did not appear to be the primary mechanism for poor survival.

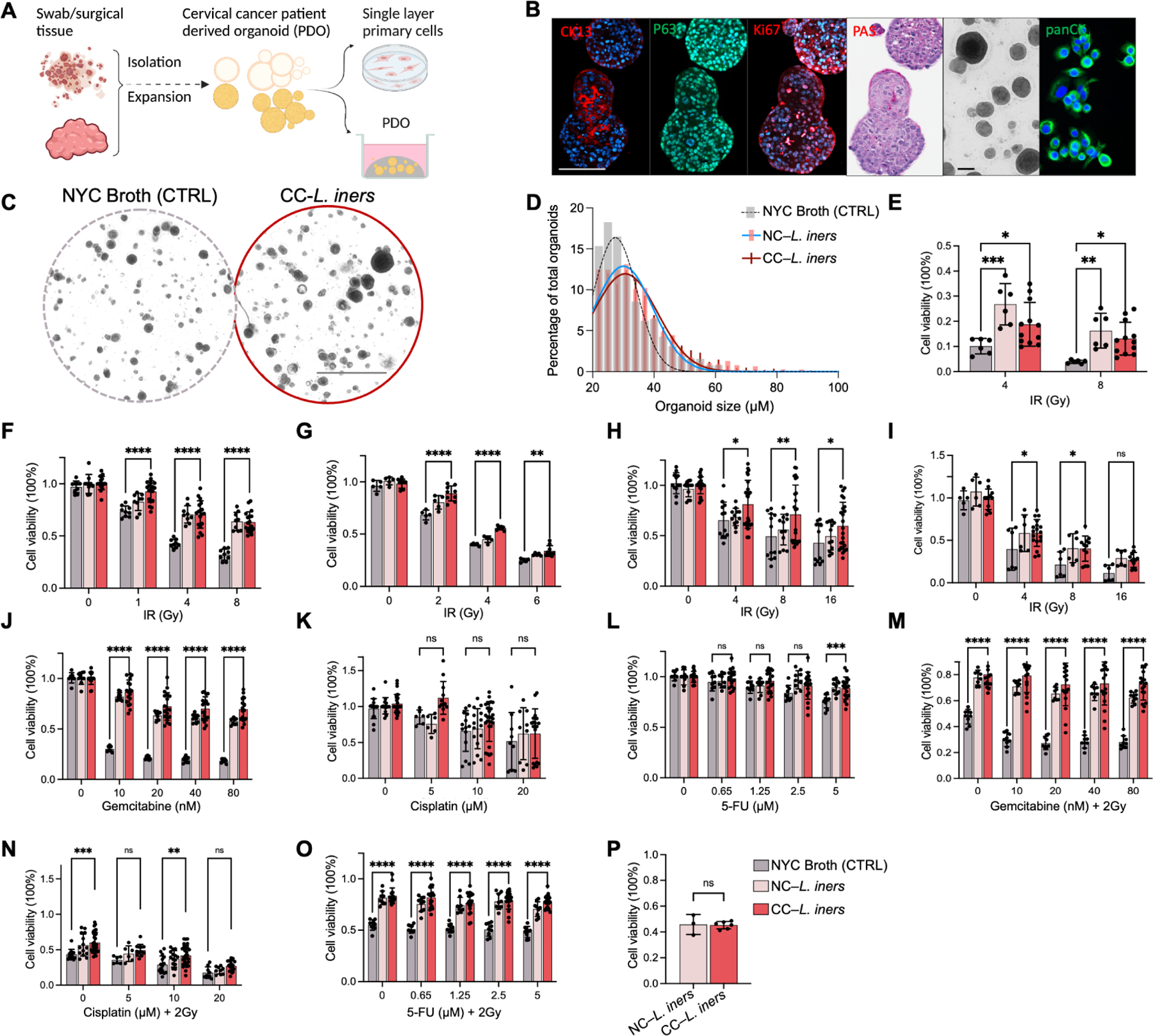

L. iners induces chemoradiation resistance in cervical cancer cell lines

To test whether L. iners from cervical cancers could directly cause radiation resistance independent of an immune effect, we cultured, isolated and characterized L. iners strains from cervical tumors, then filtered bacterial supernatant for cell-free supernatant (CFS). To identify the optimal supplement ratio of CFS in the cell culture medium and the culture condition, we performed serial dilution assays using a HPV16+ cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) cell line, CaSki (Supp. Fig. 5A). We generated a cervical cancer patient-derived organoid line (PDO, B1188) which develops a dense 3D morphology, exhibits immunofluorescence profiles consistent with CSCC (Fig. 2A, B), and is sensitive to both IR and cisplatin treatments (Supp. Fig. 5B, C). A line of genomically stable primary cells was generated after several passages (B1188 primary cells).

Figure 2. L. iners induces treatment resistance in vitro.

A) Workflow for the establishment and maintenance of patient-derived organoids (PDO) and B188 primary cells.

B) Positive staining of PDOs B1188 with antibodies for anti-P63 and anti-Ki67, together with decreased expression of the differentiation marker staining of anti-CK13 antibody and PAS, confirming squamous carcinoma origin. Positive staining of anti-panCK marker demonstrates primary cancer cell origin. Scale bars,100 μm

C) Bright view of PDO B1188 pretreated with cancer-derived L. iners (CC-L. iners) cell-free supernatant (CFS) vs. control (NYC Broth) followed by 4Gy irradiation. Scale bars,1 mm

D) Histogram of organoid size and count (percentage of total counted) for organoids from PDO B1188 pretreated with CC-L. iners CFS (red) vs. non-cancer derived L. iners (NC-L. iners; pink) vs. control (NYC Broth; grey) followed by 4Gy irradiation.

E) Cell viability (measured by CellTiter Glo) of irradiated organoids from PDO B1188 pretreated with CC-L. iners cell-free supernatant (CFS) vs. control (NYC Broth) followed by 4Gy and 8Gy irradiation. 2 experiments, 3 replicates. One way ANOVA (CFS vs. control).

F) B1188 cell viability after irradiation.

G) HeLa cell viability after irradiation.

H) SiHa cell viability after irradiation.

I) CaSki cell viability after irradiation.

J) B1188 cell viability after gemcitabine (GEM) treatment.

K) B1188 cell viability after cisplatin (CIS) and 2Gy irradiation.

L) B1188 cell viability after 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).

M) B1188 cell viability after GEM and 2Gy irradiation.

N) B1188 cell viability after CIS + 2Gy irradiation.

O) B1188 cell viability after = 5-FU and 2 Gy.

P) B1188 cell viability with UV-killed bacterial fragments and IR.

1 experiment, 3 replicates. Cell viability (measured by CellTiter Glo) following pretreatment of cells with control (NYC Broth), NC-L. iners CFS or CC-L. iners CFS (F-O); 3 experiments, 3 replicates each (F-O); 2 patient-derived CC-L. iners strains pooled (E-P); one way ANOVA between CC-L. iners with Mean and SEM are presented (E-P).

B1188 PDOs were incubated for two weeks with 20% CFS harvested from two cancer-derived L. iners strains (CC-L. iners), one commercial non-cancer-associated L. iners strains (NC-L. iners), or Control (CTRL, 20% NYC Broth), prior to treatment with ionizing radiation (IR), cisplatin (CIS), gemcitabine (GEM) or 5-fluorouracil (5FU), or their combination. PDOs cultured with CC-L. iners CFS displayed more aggressive growth and radiation resistance than CTRL, with higher organoid count, larger organoid size (Fig 2C, D; Supp. Fig 5D, E), and increased cell viability after IR (Fig 2E). CC-L. iners and NC-L. iners CFS also caused increased cell viability in B1188 primary cells (Fig. 2F). HeLa, SiHa, and CaSki cells all exhibited significantly increased cell viability with L. iners treatment at all doses of irradiation (Fig. 2G–I). CC-L. iners treated B1188 cells were resistant to GEM (Fig. 2J), but not cisplatin (CIS; Fig. 2K) or 5-fluorouracil (5FU; Fig. 2L) alone. With the addition of IR, they exhibited resistance to GEM-IR, CIS-IR, and 5FU-IR (Fig. 2M–O). L. iners similarly induced GEM resistance in CaSki cells (Supp. Fig. 5F–H), but to no chemotherapeutics without IR in SiHa or HeLa cells (Supp. Fig. 5I–M). We also evaluated cell viability after IR in HeLa cells using cancer-derived and non-cancer derived L. crispatus. L. crispatus did not induce treatment resistance (Supp. Fig. 5N). We observed no radiation sensitization with UV-killed, PBS-washed L. iners (Fig. 2P), suggesting the factors mediating radiation resistance were secreted by L. iners rather than an effect of bacterial cell wall components.

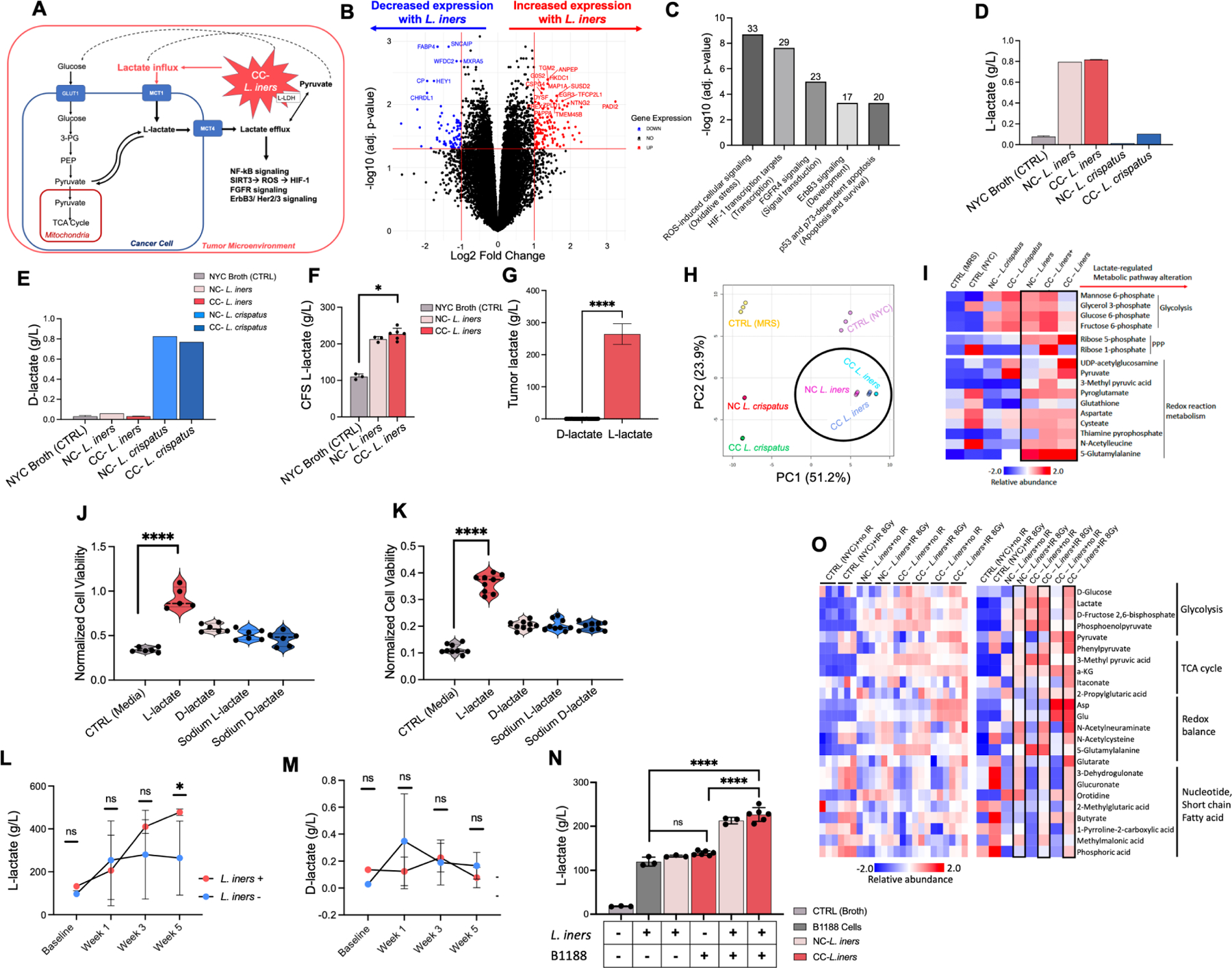

L. iners alter gene expression in lactate signaling pathways

Next, to explore how L. iners CFS could alter cancer cell sensitivity to IR, we performed RNA sequencing of pretreated B1188 cells. Our proposed mechanism for the effect of L. iners on cancer cell metabolism is given in Fig. 3A. We found that cells treated with L. iners CFS versus NYC broth control had significantly altered gene expression (Fig 3B). Metacore pathway analysis revealed enrichment in several pathways closely linked to lactate signaling and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, including reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced cellular signaling and hypoxia-inducible-factor 1 (HIF-1) transcription targets, FGFR signal transduction28–30, Her2/ERBB2 signaling31–33, and p53/p73 dependent apoptosis34 (Fig. 3C); Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Hallmark Pathway analysis confirmed enrichment in oxidative stress/ ROS-induced cellular signaling and HIF-1a transcription targets, along with the GSEA pathway for skeletal muscle genes, which is also highly regulated by lactate (Supp. Fig. 6A).

Figure 3. L. iners causes treatment resistance through increased L-lactate production in the tumor microenvironment.

A. Hypothetical schematic of L. iners production of L-lactate in the tumor microenvironment “priming” cervical cancer cells for lactate addiction, driving the feedback loop of lactate utilization via upregulation of GLUT1, MCT1 and MCT4, and lactate-regulated induction of reactive oxygen species signaling, HIF-1, NFkB, FGFR, ErbB3/HER 2/3, and p53 dependent pathways.

B. B1188 cells pre-treated with L. iners (1 NC-L. iners strain, 2 CC-L. iners strains) vs. control (NYC broth) CFS prior to RNA sequencing. Fold change in gene expression from control (right) to L. iners (left) is shown. Log2 (Fold Change) threshold of −1, 1. –Log10 (FDR-adjusted p-value) threshold is 1.2.

C. Metacore pathway analysis of significantly altered genes. Top 5 most significantly altered pathways are shown ranked by -Log10 (FDR-adjusted p-value). Number above bar represents the proportion of genes altered in each pathway.

D. L-lactate production in bacterial culture of cancer-derived CC-L. crispatus, CC-L. iners, NC-L. crispatus, NC-L. iners, and control (NYC broth).

E. D-lactate production in bacterial culture of cancer-derived CC-L. crispatus, CC-L. iners, NC-L. crispatus, NC-L. iners, and control (NYC broth).

F. L-lactate levels in bacterial culture for control (NYC Broth), NC-L. iners or CC-L. iners.

G. L-lactate and D-lactate relative levels (g/L) for cervical tumor Cytobrush samples (log scale). N=29.

H. Principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolites.

I. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of most differentially abundant metabolites, grouped by metabolic process.

J. Cell viability (CellTiter Glo) of pretreated B1188 cells with 20mM lactate isoforms (L-lactate, D-lactate, Sodium L-lactate, Sodium D-lactate, media control) after irradiation (4Gy).

K. Cell viability (CellTiter Glo) of pretreated B1188 cells with 20mM lactate isoforms after GEM.

L. L-lactate levels in cervical tumor Cytobrush samples before, during (Week 1, Week 3) and after EBRT (Week 5) for L. iners + patients (BL N=1; Wk1 N=6; Wk3 N=2; Wk5 N=4) and L. iners− patients (BL N=3; Wk1 N=4; Wk3 N=6; Wk 5 N=4).

M. D-lactate levels in cervical tumor Cytobrush samples.

N. L-lactate levels for media control (−/−), L. iners in culture alone (+/−), B1188 cells in culture alone(−/+), vs. B1188 cells treated with L. iners CFS (+/+) for NC-L. iners and CC-L. iners.

O. Differentially abundant metabolites present in primary cells B1188 treated with NYC Broth (control), NC-L. iners (N=1) CFS, and CC-L. iners (N=2) CFS, either nonirradiated (0Gy) or irradiated (8Gy), grouped by metabolic process.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of most differentially abundant metabolites, grouped by metabolic process (I,O); Analyzed by Megazyme Kit (D,E), TC-MS (L-N) or HR-MS/IC-MS (I,O); Wilcoxon rank-sum test (J-M), unpaired t-test with mean and SEM (G) or 2-way ANOVA (F) with NS P > 0.05, *P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001; 1 (B,F,J),N, 2 (H-J) or 3 (K) experiments, 3 replicates each, 2 CC-L. iners strains pooled (B,F,J); 1 experiment, 1 culture plate, no statistical comparisons (D-E). Wilcoxon rank-sum test vs. CTRL unadjusted (J-L) and adjusted (N); Comparisons for cells treated with MRS Broth (L. crispatus control), NYC Broth (L. iners control), and cancer and non-cancer derived L. iners (N=3) and L. crispatus strains (N=2) (H-I). Normalized to unirradiated media control (J-K).

L. iners are obligate L-lactate producers and CC-L. iners+ tumors are L-lactate enriched

All lactobacilli produce lactate as the final product of fermentation via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity after carbohydrate utilization35–37. One of the distinguishing characteristics of L. iners, compared to beneficial lactobacilli38, is that its smaller genome uniformly does not contain the D-LDH gene, rendering it an obligate L-lactate producer. L-lactate is also the predominant enantiomer (97–99%) in mammalian cells and tumors39. Although cancer cells can produce D-lactate by the methylglyoxal pathway, this likely negligibly affects metabolism.

CC-L. iners produced only L-lactate in vitro (Fig. 3D), while cancer-derived and non-cancer derived L. crispatus produced primarily D-lactate (Fig. 3E); All cancer-derived L. iners genomes did not contain D-LDH. We validated this using quantitative L and D-lactate ion chromatography-mass spectrometry (IC-MS) assays. CC and NC-L. iners had significantly higher L-lactate levels than broth controls (Fig. 3F). In cervical tumor samples, we confirmed that L-lactate levels were >1,000 fold greater than D-lactate (Fig. 3G).

Non-targeted metabolic profiling of CFS from NC and CC-L. iners and L. crispatus strains revealed distinct metabolic network alterations in glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the regulation of redox balance for CC-L. iners, all of which are linked to oncogenic lactate metabolism (Fig. 3H, I).

L-lactate recapitulates treatment resistance in cervical cancer cell lines

To determine whether L-lactate alone could induce chemotherapy and IR resistance similar to L. iners CFS, we pretreated cervical cancer cell lines with four isoforms of lactate: L-lactate, D-lactate, sodium L-lactate and sodium D-lactate for two weeks prior to chemotherapy or IR treatment. The lactate concentrations and pH were maintained until harvest. L-lactate, but not other isoforms, in the culture medium consistently recapitulated the treatment resistance of cervical cancer cells to IR and GEM in all cell lines, with varying effects observed for CIS and 5-FU (Fig. 3J–K; Supp. Fig. 6B–E), which was consistent with the effect of L. iners CFS.

L. iners increases tumor metabolic activity in response to radiation-induced stress

Although at baseline, there was no difference in measured L-lactate levels between L. iners+ and L. iners – tumors; interestingly, L-lactate levels (but not D-lactate levels) in L. iners+ tumors increased steeply from baseline to the end of CRT, nearly doubling by week 5 (Fig. 3L–M). Irradiated L. iners treated B1188 cells also significantly increased L-lactate production versus broth (CTRL) or L. iners alone, and demonstrated remarkable upregulation in glycolysis, TCA cycle, redox balance and nucleotide, short chain fatty acid assembly, particularly after irradiation (Fig. 3N–O).

These data demonstrate that L. iners can potentiate lactate utilization, production and metabolic activity in response to metabolic stress, including from IR.

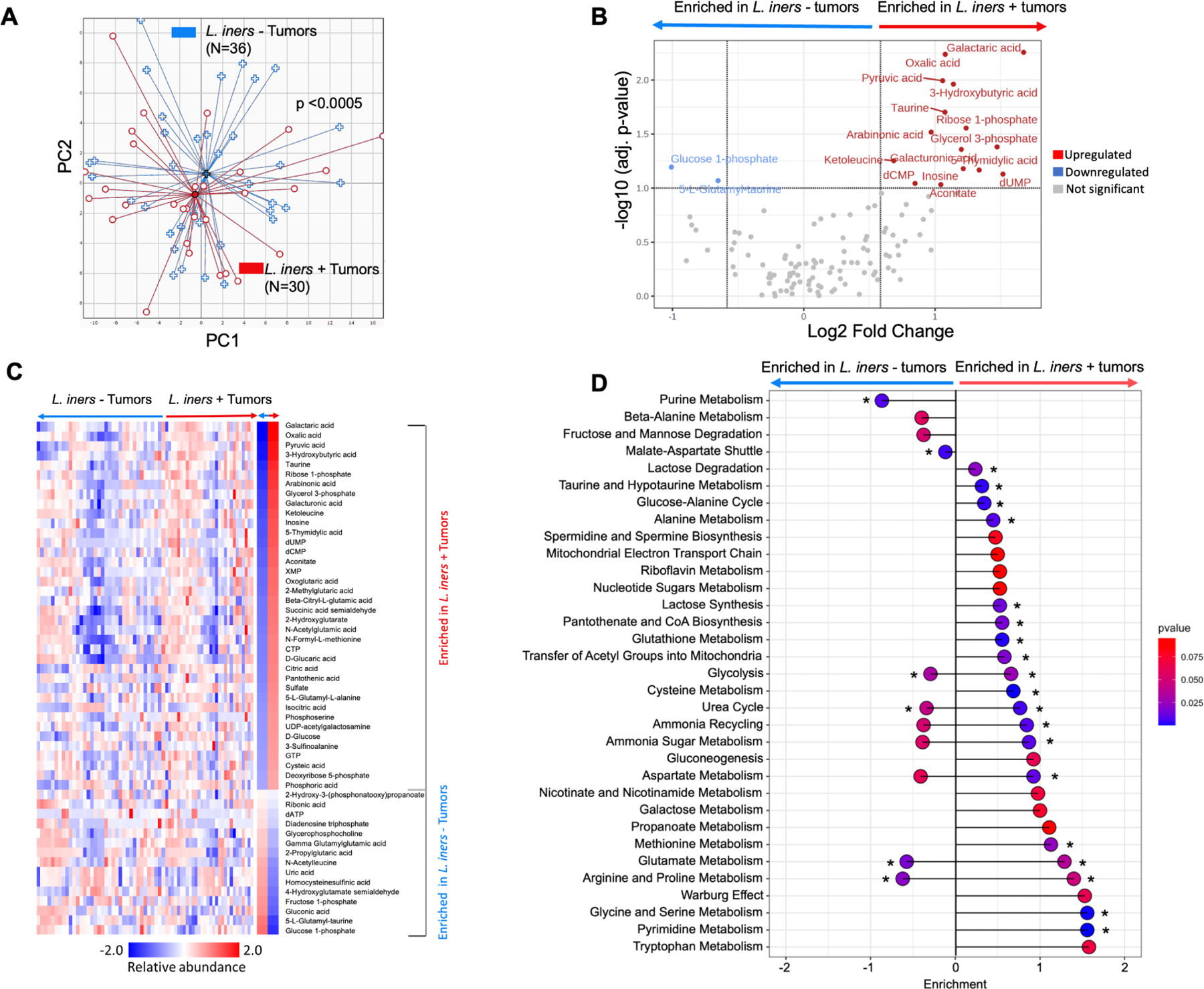

L. iners+ tumors have upregulated glycolysis compared to L. iners− tumors

L. iners is a facultative anaerobe, and can make ATP via aerobic respiration or switch to fermentation under anaerobic conditions, efficiently producing lactate. Thus, we hypothesized that the lactate production and metabolic rewiring might be magnified in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment in patients. Principal component analysis (PCA) of non-targeted metabolomics confirmed distinct metabolite profiles for L. iners+ (N=30) and L. iners- tumors (N=36; Fig 4A; DSC p<0.005), and significant enrichment of unique metabolites in L. iners+ tumors (Fig. 4B), overall indicative of higher metabolic activity. Supervised clustering confirmed clusters of metabolites differentially enriched in L. iners+ vs. L. iners− tumors (Fig. 4C). Metabolites significantly enriched in L. iners+ tumors were pyruvate, indicative of increased glycolysis, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and NADH, both indicative of upregulated TCA cycling and downstream electron transport chain activity, and deoxyguanosine triphosphate (dGTP) and deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP), both precursors for increased DNA synthesis, which can be driven by excess ATP. Galactaric acid was also significantly enriched in L. iners+ tumors; galactaric acid is an indicator of increased fermentation and lactate production in lactobacilli. The metabolic pathways most upregulated in L. iners + tumors were the Warburg effect, glycolysis, glutamate metabolism, and galactose metabolism (Fig. 4D, Supp. Fig. 6F–H).

Figure 4. L. iners positive tumors have metabolic alterations compared to L. iners negative tumors.

A. Principal coordinate analysis of relative abundances of tumor metabolites for L. iners+ (N=36) and L. iners− tumors (N=30). Dispersion Separability Criterion, p<0.005.

B. Volcano plot of differentially abundant metabolites. –Log10 (adj. p-value) threshold=1.0; log2 (Fold Change) threshold −1 to 1.

C. Supervised hierarchical clustering of differentially abundant metabolites.

D. Lollipop plot of pathway assignments for differentially enriched metabolites. Sorted by effect size on a log10 scale. * FDR-adj p<0.05.

Analyzed by HR-MS and IC-MS (A-D).

The most significantly enriched metabolite in L. iners- tumors was 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR). AICAR is an analog of adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and activates the AMP-kinase cascade in response to ATP deprivation, such as in downregulated glycolysis. AICAR is pro-apoptotic in this setting, and strongly suppresses cancer cell proliferation in response to ATP deprivation. It is used as a cancer therapy sensitizer in various cancers27–32 and can reverse Warburg metabolism33. These findings strongly suggest that L. iners plays a significant role in contributing to energy production and DNA synthesis within the tumor microenvironment.

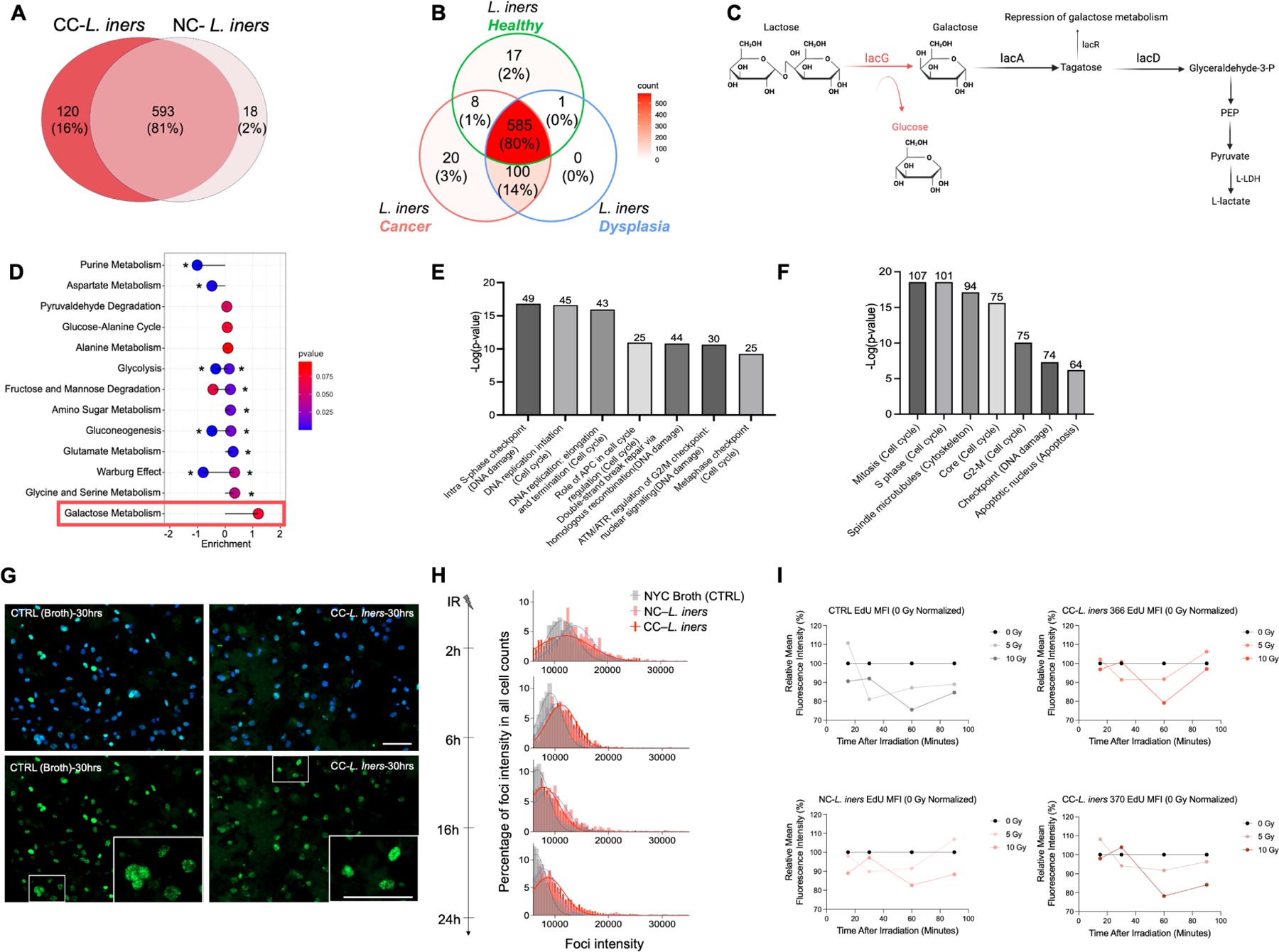

Cancer-derived L. iners acquires additional genes for lactose utilization during carcinogenesis

L. iners is a common organism in a healthy cervicovaginal microbiome and regularly undergoes horizontal gene transfer to evade antibiotics and adapt to changing nutrient, pH and oxygenation conditions40. We hypothesized that CC-L. iners in patients with cervical cancer acquired additional genes during carcinogenesis, which may contribute to the metabolic affects observed.

To identify potential functions unique to CC-L. iners, we sequenced the complete genomes of two CC-L. iners isolates and two NC-L. iners isolates. We also performed SMS on baseline tumor samples (N=44) and assembled Lactobacillus genomes. We compared these to complete genomes of L. iners KY41, isolated from a healthy individual. All contigs annotated by L. iners in the metagenomes were combined and contigs that were annotated by any Lactobacillus (99% L. iners) to represent a cervical cancer Lactobacillus “pan-genome” (Supp. Fig. 7A). 593 genes (81%) were shared between CC-L. iners and NC-L. iners. 120 (16%) genes were unique to CC-L. iners, while NC-L. iners contained only 18 unique genes (2%; Fig. 5A). There were also more shared KOs (N=100; 14%) between dysplasia- associated L. iners (N=14) and CC-L. iners than between NC-L. iners and CC-L. iners (Fig. 5B). Overall, this higher genetic commonality between dysplasia-associated L. iners and CC-L. iners suggests these genes were acquired prior to or during carcinogenesis, rather than after cancer development.

Figure 5. Cancer-derived L. iners acquires additional genes for lactate production over NC-L. iners and alters cancer cell gene expression in pathways involved in intrinsic radiation sensitivity.

A. Overlapping and unique Genes on comparative genomic analysis for CC- L. iners (16%) vs NC-L. iners (2%) vs. shared (81%).

B. Overlapping genes on comparative genomic analysis for Healthy L. iners vs. dyplasia L. iners vs. CC- L. iners.

C. Sequential genes in pathways common to CC- L. iners and CC- L. iners (black) and unique to CC- L. iners (red) on comparative genomic analysis. LacG in CC- L. iners encodes the reversible enzyme, 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase, which converts lactose to galactose, while CC- L. iners ers utilizes only lactose in the lacDRA pathway. LacR is a repressor switch to turn off lactose metabolism to lactate.

D. Lollipop plot of metabolite pathways assignments for metabolites enriched in CC- L. iners isolates vs. NC-L. iners isolates. Galactose metabolism is the only upregulated pathway, consistent with lacG gene acquisition and 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase activity.

E. Top 7 differentially expressed metacore pathways for B1188 cells.

F. Top 7 differentially expressed metacore processes for B1188 cells.

G. Gamma H2AX and DAPI fluorescent staining of pretreated B1188 cells 30 hours after irradiation (8 Gy). Scale bars,100 μm

H. Gamma H2AX dynamics for primary cells B1188 treated with 8Gy in each CFS condition.

I. Radio-resistant EdU DNA synthesis assays for pretreated B1188 primary cells. Normalized to 0 Gy (black).

Log2 (Fold Change) cutoff of 2.0 (E,F); 1 independent experiment, 1 (I) or 3 (E) replicates, 2 CC-L. iners strains pooled (E) or separate (I); No statistical comparisons made (H,I).

We also performed gene, function, and pathway analysis (KO, KEGG, BRITE) to determine the function of genes acquired by CC-L. iners that were not present in NC-L. iners. We compared the genomes of CC-L. iners isolates and a near complete assembly of L. iners obtained from a patient sample with NC-L. iners. A complete comparison of genes, functions, and pathways unique to and shared by CC-L. iners and NC-L. iners (Supp. Fig. 7B–C, Supp. Table 4) demonstrated that, while all L. iners strains had the lacA, lacD, and lacR genes involved in conversion of galactose to D-glyceraldehyde-3-P and Fructose-6-P, only CC-L. iners also contained the additional lacG gene, which encodes 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase, which converts lactose to Galactose-6-P and Glucose (Fig. 5C, Supp. Fig 7C–D, Supp. Table 4). Lactobacilli can easily convert lactose to lactate, and galactose to lactate in the reverse direction, via the Leloir pathway and the Tagatose-6-phosphate pathway36,42,43. All L. iners+ patient samples and L. iners isolates contained only L-LDH, while none contained the gene for D-LDH. Non-targeted metabolomics of CC-L. iners and NC-L.iners isolates revealed the only upregulated pathway in CC-L. iners vs. NC-L. iners was galactose metabolism, consistent with the genomic findings (Fig. 5D).

DNA damage and response in cervical cancer cells after CFS treatment

We also investigated intrinsic DNA sensitivity and repair in CC-L. iners and NC-L. iners treated cells. While gene expression with any L. iners versus control involved lactate signaling pathways (Fig. 3, Supp. Fig. 7E), there were also notable differences in gene expression specifically for unirradiated CC-L. iners treated cells versus NC-L. iners treated cells (Fig. 5E, F; Supp. Fig. 7F–G), with significant downregulation of several DNA damage response pathways, DNA replication and initiation, G2/M and intra-S phase checkpoints and E2F transcription targets. We also noted a general, slightly higher resistance to IR for CC-L. iners vs NC-L. iners treated cells (Fig 2). After irradiation, CC-L. iners versus NC-L. iners treated cells demonstrated significant gene expression alterations, with upregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT), NFKb signaling, and KRAS signaling, and downregulation of hypoxia response signaling (Supp. Fig. 7H Supp. Table 5). The gene expression data for treatment with L. iners demonstrated increased expression of oxidative stress/ ROS-induced cellular signaling and HIF-1 transcriptional targets in the cells cultured with L. iners CFS compared to cells cultured with broth both before (Fig. 3C and Supp. Fig. 7C) and after irradiation (Supp. Fig. 7D), suggestive of increased ROS and hypoxia in the microenvironment. ROS elevation correlates with increased γ-H2AX and causes induction of double-strand breaks and assurance of DNA damage response activation44–47. We evaluated γ-H2AX foci kinetics at different time points (2 hours [2h] to 24 hours [24h]) after 8Gy irradiation. All cells expressed the strongest foci intensity 2h after IR, with decreasing intensity over time, indicating DNA damage repair. CC-L. iners exhibited less initial foci generation as compared to NC-L. iners, while both exhibited more initial foci formation versus CTRL (Fig. 5G, H). CC-L. iners exhibited the most rapid return to normal levels, indicating efficient repair overall.

We also noted altered expression in S phase and G2/M checkpoint regulation genes (Fig. 4E-F), and a trend toward increased incorporation of EdU by cells treated with L. iners (Fig. 5I) suggestive of a dysfunctional intra-S phase checkpoint, and slight distinctions in redox reaction metabolism for CC-L. iners vs. NC-L. iners (Fig. 3H, 3O). Lactose degradation via the lacG gene in CC-L. iners produces glucose as a byproduct (Fig. 5D), which can also induce G2/M checkpoint arrest by the Cdk1/ CyclinB complex, and enhance tumor survival post-irradiation despite DNA damage52–55, consistent with the gene expression data. Further investigation is needed.

L. iners and similar lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are relevant in other cancer types

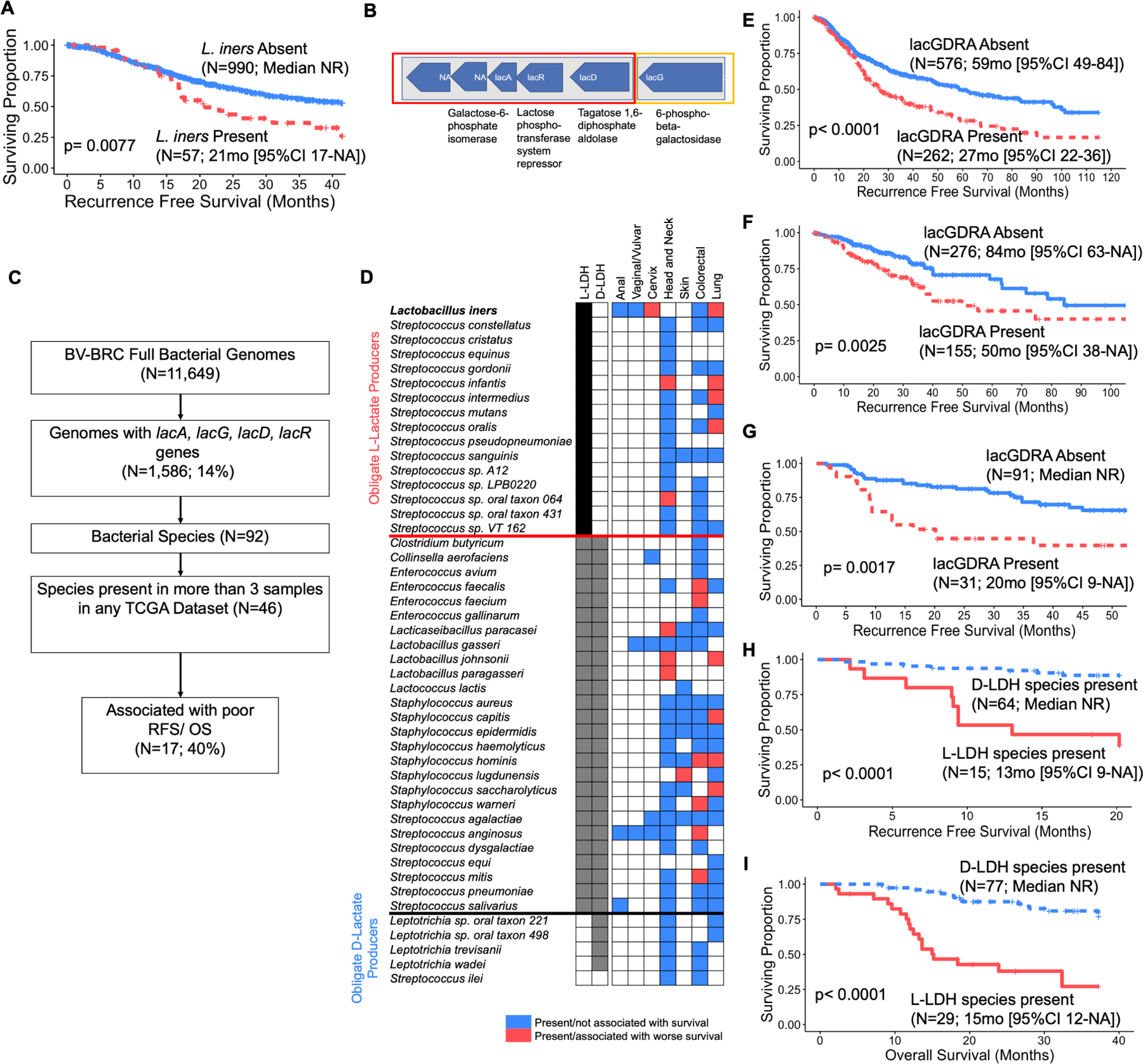

We also analyzed microbiome composition of tumor samples from anal, (N=70), vaginal and vulvar cancer (N=44) at MDACC and reprocessed raw reads from whole genome sequencing (WGS) and RNA sequencing (RNAseq) in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC; N= 171), colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD; N=502), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; N=1047), and melanoma (SKIN; N= 106). L. iners was identified in anal, vaginal, vulvar, colorectal and lung cancers but, not unexpectedly, extremely rarely, since L. iners is a commensal vaginal microbe. Still, L. iners in NSCLC (N=57; 5.4%) was strongly associated with decreased RFS (Fig 6A; 21 months vs. Not reached [NR]; log-rank p=0.0077).

Figure 6. L. iners and genomically similar, commensal, L-lactic acid producing bacteria (LAB) portend poor prognosis across cancer types.

A. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) for L. iners presence (N=57) or absence (N=990) in primary tumor samples from the non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) TCGA dataset.

B. Consecutive operons found in L. iners isolates and deposited genomes (CC-L. iners = 2, NC-L. iners = 2) on comparative genomic analysis. Orange denotes lacG gene found only in CC-L. iners isolates, vs. red which denotes lac genes found in all L. iners isolates.

C. Flowchart for identification of genetically similar LAB species in TCGA datasets.

D. Frequency of lacGDRA bacteria genomically similar to L. iners (N=46) across MDACC (anal, vaginal/vulvar, cervix) and TCGA datasets (head and neck, skin, colorectal, lung). Red box denotes species is present and associated with decreased RFS and/or overall survival (OS) in individual dataset. Blue box denotes species is present in dataset, but not associated with RFS or OS.

E. RFS for patients with NSCLC stratified by presence (N=262) or absence (N=576) of any lacGDRA species from Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC).

F. RFS for patients with Colorectal adenocarcinoma stratified by presence (N=155) or absence (N=276) of any lacGDRA species.

G. RFS for patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) stratified by presence (N=31) or absence (N=91) of any lacGDRA species.

H. RFS for patients with HNSCC stratified by presence of at least one obligate D-lactate producing lacGDRA bacterial species (Leptotrichia trevisanii or Leptotrichia wadei) and no obligate L-lactate producing lacGDRA bacterial species (N=64) vs. at least one L-lactate producing species (Lactobacillus paragasseri, Streptococcus infantis, Lactobacillus johnsonii, Streptococcus sp. oral taxon 064, or Lacticaseibacillus paracasei; N=15).

I. OS for patients with HNSCC stratified by presence of at least one obligate D-lactate producing lacGDRA bacterial species (Leptotrichia trevisanii or Leptotrichia wadei) and no obligate L-lactate producing lacGDRA bacterial species (N=77) vs. at least one L-lactate producing species (Lactobacillus paragasseri, Streptococcus infantis, Lactobacillus johnsonii, Streptococcus sp. oral taxon 064, or Lacticaseibacillus paracasei; N=29).

Kaplan-meier survival curves with log-rank test for comparison. (A, E-I).

Although L. iners is almost exclusively a cervicovaginal microbe, LAB are ubiquitous across body sites. We hypothesized that functionally similar LAB could impact tumors in their respective niches. We identified 92 bacterial species whose genomes (N=1,586) contained the lacA, lacG, lacD, and lacR genes found in CC-L. iners; 46 in more than 3 patients (Fig. 6B–D). 40% of these species (17/46) were associated with decreased RFS and/ or OS in other cancers (Fig. 6D, Supp. Table 5).

The presence of any tumoral lacGDRA bacteria was significantly associated with lower RFS in all four cancers, including NSCLC (Fig. 6E; 27 months vs. 59 months; p<0.0001), COAD (Fig. 6F; 50 months vs. 84 months; log-rank p=0.0025), HNSCC (Fig. 6G; 20 months vs. NR; p=0.0017), and SKIN (Supp. Table 5; 6 months vs. NR; log-rank p=0.0041). Significant species included: Enterococcus (E.) faecalis (COAD), E. faecium (COAD), L. paracaseii (HNSCC), L. johnsonii (HNSCC, NSCLC), L. paragaseii (HNSCC). Staphylococcus (S.) capitis (NSCLC), S. hominis (COAD, NSCLC), S. lugdunensis (SKIN), S. saccharolyticus (NSCLC), S. warneri (COAD), S. anginosus (COAD), and Streptococcus mitis (COAD) (Supp. Table 5).

Obligate L or D-lactate production by genetically similar LAB is associated with survival.

Thirty percent (5/16) of the obligate L-lactate producers (with L-LDH gene but no D-LDH) were associated with poor patient survival (L. iners, S. infantis, S. intermedius, S. oralis, and S. sp. Oral taxon 064), while none of the five obligate D-lactate producers (Leptotrichia sp. oral taxons 221 and 498, Leptrotrichia trevisanii [L. trevisanii], Leptrotrichia wadeii [L. wadeii], S. ilei) were (Fig. 6D); 40% (2/5) of the D-lactate producers (L. trevisanii and L. wadeii) were associated with increased rather than decreased RFS and/or OS, consistent with previous reports that D-lactate producing LAB in the gut microbiome are protective56–59,59–61. No other obligate L-lactate or mixed L/D-lactate producers were associated with decreased RFS.

In HNSCC, there was nearly 100% RFS (Fig. 6H; Median NR vs. 13 months; p<0.0001) and OS (Fig. 6I; Median NR vs. 15 months; p<0.0001) in patients with only obligate D-lactate producers versus a median of 13 months in patients with at least one detrimental L-lactate producing LAB, suggesting that D-lactate could outcompete L-lactate for monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) in tumor cells. While L. iners is a commensal cervicovaginal microbe, its functions are likely relevant in other cancers.

DISCUSSION

Here, we demonstrate that cervical cancer-associated Lactobacillus iners, an obligate L-lactate producing facultative anaerobic bacterium, induces treatment resistance through efficient L-lactate production and metabolic rewiring in tumors. This is supported by strong clinical associations, the induction of chemotherapy and radiation resistance by L. iners or L-lactate, and its high lactate production in vitro and in tumors after irradiation. This finding is not limited to cervical tumor bacteria or cervical tumors; instead, we argue that tumor-associated LAB participate in lactate-mediated metabolic rewiring in a similar fashion to described tumor-stroma or tumor-immune cell interactions, with broad implications in many cancer types.

Lactate is a powerful exchangeable metabolic coupling molecule between cancer cells, rather than simply a metabolic waste product, and cross-talks with many known treatment resistance mechanisms. Metabolic coupling occurs via exploitation of the reversible LDH enzyme to convert lactate to pyruvate or vice versa, and in turn, recycling NAD to NADH+. Tumor lactate and LDH expression are correlated with aggressive tumor biology and poor survival across cancer types62–65, including cervical cancer66, perhaps because a higher lactate level in tumors is representative of higher glucose-to-lactate metabolic flux. It can serve as a metabolic fuel, a ‘hormone’ sensed by membrane receptors, and an epigenetic modifier through histone lactylation, all of which can directly affect DNA synthesis and lead to radiation and chemotherapy resistance.

Lactate is a “lactormone,” acting in a hormonal positive feedback loop and serving as an exchangeable molecule and a key regulator of interactions between tumor cells and surrounding cells,67 including tumor-stroma, cancer cell-cancer cell, cancer cell- astrocyte, and cancer cell-fibroblast interactions. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)68–70 can be activated by SIRTUIN3 release as a result of tumor-stroma contact, which in turn causes mitochondrial oxidation and upregulates MCT4 expression, lactate biosynthesis, glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and glycolysis. SIRTUIN3 is a key molecule in cervical cancer71. Lactate is also a strong promoter of dendritic cells and tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) recruitment in the tumor microenvironment. We propose that L. iners in the tumor microenvironment has a symbiotic relationship with cancer cells to fuel growth via these pathways, similar to what has been demonstrated for fibroblasts or immune cells.

Lung cancers, which share many key metabolic genes with cervical cancers, including PI3K/AKT, STK11, and TP53, exhibit a striking preference for lactate utilization over glucose to fuel the citric acid cycle63. This activity is particularly profound when cancer cells adapt to oxidative stress, wherein excess lactate leads to upregulation of MCT1 and MCT4 for overall lactate influx and efflux. This phenomenon of “lactate addiction” results in efficient use of lactate to fuel the TCA cycle and other metabolic pathways, and an even higher preference for lactate over glucose. L. iners in the tumor microenvironment may similarly “prime” cervical cancer cells and magnify the lactate feedback loop that results from oxidative stress after radiation or chemotherapy.

Many therapeutic opportunities exist to target LAB involved in therapeutic resistance. Modification of the vaginal microbiome is feasible, inexpensive, and relatively low risk. For example, in bacterial vaginosis (BV), the application of topical metronidazole followed by reconstitution of a beneficial strain of L. crispatus, known as LACTIN-V, resulted in vaginal colonization by L. crispatus in nearly 80% of patients72. Other potential therapies to eliminate L. iners, such as topical application of bacteriocins, lytic phages, bioengineered bacteria, or clinically proven probiotics73,74 could be repurposed for cancer therapy. Lactobacilli themselves are promising candidates for bioengineered microbial cancer therapeutics, due to the simplicity of genome editing and general lack of pathogenicity36,75–79. L. iners itself could be exploited to deliver anti-cancer drugs with tumor specificity, given its strong commensality to cervical tumors and the cervicovaginal niche.

Outside of bacterial targeting, systemic use of targeted therapies related to lactate uptake and conversion could also be useful in patients with tumoral LAB. Several clinically available LDH inhibitors exist, which could prevent conversion of lactate to pyruvate in these tumors. There is known strong synergy between gemcitabine and LDH inhibitors, so our data demonstrating extreme treatment resistance with L-lactate provides rationale for adjuvant or concurrent use of an LDH inhibitor in these patients80. Further, there are several promising MCT inhibitors in various stages of clinical and pre-clinical development, including first in class single inhibitors of MCT1 and MCT2, and MCT1/MCT4 and MCT2/MCT4 dual inhibitors81. MCT1 inhibitors with tumor specificity and a very high affinity for MCT182 or LDH inhibitors could be used as a targeted therapy in patients with lactate-producing bacteria.

Overall, these data provide strong evidence of an opportunity for targeted interventions in the tumor microenvironment of lactic-acid bacteria populated tumors for future clinical translation.

Limitations of the Study

Our study is limited by the absence of an in vivo L. iners colonization model to distinguish tumor and gut microbiome effects, assess tumor metabolism, or explore reversibility by eliminating L. iners, as such models arenť currently available for mice or non-human primates. Future models are needed for these investigations. Our analysis of L. iners in the tumor microenvironment only considered CD4+ CD8+ T cell composition and clonal expansion. Lactate in the tumor microenvironment affects various unexamined immune processes, including macrophage polarization and dendritic cell recruitment. Additionally, iťs unclear if L. iners, especially cancer-associated strains, confer intrinsic resistance to double-stranded DNA breaks or repair mechanisms beyond lactate's effects on radiation resistance and DNA damage. Further mechanistic studies are required and it is possible that there are other mechanisms of DNA damage and repair, which are outside the scope of this study.

STAR METHODS

Resource Availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Lauren Colbert (lcolbert@mdanderson.org)

Materials availability

Patient-derived Lactobacilli are grown at MD Anderson and available for sharing per request under an MTA, where applicable. The sequences of these strains have been uploaded to NCBI. The cervical cancer patient-derived organoid line, B1188, is also available at MD Anderson and available for sharing upon request under an MTA. They have been characterized, and sequencing data uploaded to SRA.

Data and code availability

16S and WGS have been deposited in SRA and will be made publicly available upon publication of the manuscript (BioProject accession numbers: PRJNA989630, PRJNA702617, PRJNA685389). L. iners strain assemblies using WMS have been deposited in NCBI and will be made publicly available upon publication (BioSample accession numbers: SAMN27176861, SAMN27176862, SAMN27176863, SAMN27176864). TCR Sequencing data has been deposited in immuneACCESS and will be made public upon acceptance. Processed microbiome, TCR sequencing, RNA Sequencing and TCGA data are available in supplementary material, along with sample metadata and clinical data.

All original code used to generate figures or tables is available in this paper’s supplemental information.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data or code reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental Model and Study Participant Details

Study design, patient inclusion criteria and chemoradiation treatment

Patients with cervical cancer were enrolled on a University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) institutional review board (IRB) approved prospective biomarker collection study (MDACC 2014–0543, 2019–1059). We upheld all required ethical standards and approvals during the study, including, but not limited to, those set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki, Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committees, and relevant national and international guidelines. Patients with locally advanced, non-metastatic cervical cancer planned for standard-of-care chemoradiation with curative intent were consented to the study. Patients were required to have visible cervical tumor amenable to sampling. 101 patients were enrolled from MDACC main campus and 23 from Harris Health System, Lyndon B. Johnson General Hospital Oncology Clinic (LBJ) (Supp. Table 1) between September 2015 and March 2022. Patients underwent initial staging including PET/CT and MRI prior to enrollment. The majority of tumors were International Federation of Gynecologic Oncology (FIGO) 2009 stage IIB (37%). Patients with stage IB1 disease were treated with CRT due to gross nodal disease. Patients received a minimum of 45Gy of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) using intensity modulated- radiation therapy (IMRT) in 25 fractions over five weeks concurrently with weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 in 2Gy fractions, followed by two pulsed- dose rate brachytherapy treatments at approximately week five and week seven with EBRT between brachytherapy treatments for gross nodal disease or persistent disease in the parametria to a minimum dose to gross disease of 60Gy including brachytherapy contributions. Fused PET/CT and MRI scans were used for treatment planning. Brachytherapy was planned using 3-D volumetric planning, generally with MRI guidance in addition to CT. The week five sample was taken in the operating room during the first brachytherapy treatment. Response to radiation was monitored using clinical exams through the course of treatment, MRI at week five, and surveillance PET/CT +/− MRI at approximately three months post-treatment. Non- response to radiation was defined as residual FDG-avidity at the time of first follow-up PET/CT. For survival analysis, any biopsy-proven recurrence identified on physical exam or follow-up imaging was coded as a recurrence event, and any recurrence or death due to any cause was coded as an overall survival event. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) time was calculated from diagnosis to first recurrence event or last known MDACC/ LBJ clinic visit with physical exam and/or imaging. Overall survival (OS) time was calculated from diagnosis to last known contact with patient or tumor board vital status record.

Cell Lines

HeLa cells were a generous gift of the Sam Mok lab. Cells were cultured in 1X MEM with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. These cells have not been authenticated. SiHa cells were ordered from ATCC (HTB-35). SiHa cells were cultured in 1XMEM with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. CaSki cells were ordered from ATCC (CRL-1550). CaSki cells were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Both SiHa and CaSki cells were authenticated through ATCC. HeLa, SiHa, and CaSki cell lines are female.

Bacterial Strains

Lactobacillus iners isolates (ATCC, Pt-1 (IN366), Pt-2 (IN370)) were cultured in NYC III broth at 37°C in anaerobic conditions (10% CO2, 5% H2, nitrogen balance). Lactobacillus crispatus isolates (ATCC and Pt-3 (I012T4)) were cultured in MRS broth at 37°C in anaerobic conditions (10% CO2, 5% H2, nitrogen balance).

Method Details

Sample Collection

Physicians collected swabs and cytobrush samples of the cervical tumor at five time points: baseline, week one (after five radiotherapy fractions), week three (10–15 fractions), week five (20–25 fractions; first brachytherapy treatment), and first follow-up (12 weeks post-treatment). Tumor swabs for microbiome sequencing were collected with an Isohelix Buccal Swab (Isohelix, DSK-50). Swabs were placed into individual collection tubes and transported at room temperature to the lab within 4 hrs. 400 μLs of stabilization buffer (Isohelix) was added to each tube, or prefilled tubes were used when available (BFX S1/05/50). Tubes were vortexed for 15 secs and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction. DNA for TCR sequencing was extracted from tumor swabs using the Isohelix Xtreme DNA lysis kit per the manufacturer’s instructions (Isohelix, cat. #XME-50). Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using MoBIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen). DNA samples were stored at −20°C.

Tumor cells and supernatant for metabolomics and flow cytometry were collected using Cytobrush Plus Endocervical Samplers (Cooper Surgical) from the tumor and immediate region using previously validated techniques. Brushes were placed into individual conical tubes and immediately transported at room temperature to the lab. In the lab, 10 mLs of sterile complete RPMI-1640 media, containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin and gentamicin antibiotics (HyClone, Corning, Lonza, respectively) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning), were added to each tube, which were then vortexed for 1 min to dislodge and suspend cells. When large amounts of mucus were present, 5 mLs of dithiothreitol solution (1X Hank’s balanced salt solution, 4% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM dithiothreitol; Invitrogen) were added to the cell suspensions and passed through a 70-μm cell strainer into new conical tubes. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in sterile complete RPMI-1640 media for counting. For flow cytometry, pellets were immediately used for flow cytometry. For metabolomics, cells were pelleted again and resuspended in sterile freeze media, composed of 90% FBS (Corning) and 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), and stored at −80°C.

Two BBL CultureSwabs (BD Biosciences) were swabbed in the tumor region by a physician and transported to the lab within 30 minutes for downstream culturing to isolate patient Lactobacillus strains.

For blood samples, 1 mL of blood was collected into 3 6-mL serum clot activator-containing vacutainers (BD Biosciences) and transported at room temperature to the lab within 4 hrs. Upon arrival in the lab the blood was immediately stored at −80°C until metabolomics processing.

For human tissue used for organoid culture, fresh cancer tissue was obtained from a surgical resection specimen of a cervical cancer patient under the designated ethical protocol. She participated in this study under an IRB-approved protocol (2019–1059) and signed informed consent form approved by the responsible authority.

16S rRNA Sequencing

16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed at the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research (CMMR) at Baylor College of Medicine. 16S rRNA was sequenced using methods adapted from the methods used for the Human Microbiome Project and Earth Microbiome Project83,84 Briefly, the 16S rDNA V4 region was amplified by PCR using a 515F-806R primer pair and sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina) using the 2×250 bp paired-end protocol. The primers used for amplification contain adapters for MiSeq sequencing and single-end barcodes allowing pooling and direct sequencing of PCR products83.

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (SMS)

For clinical isolates, DNA was isolated from Lactobacillus strains with Gentra Puregene Yeast/Bact. Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. For patient tumor samples, after 16Sv4 sequencing, DNA isolates from tumor swabs were sequenced with Illumina sequencers. SMS was performed by personnel of the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research at Baylor College of Medicine. Whole Genome Shotgun sequencing was performed on genomic bacterial DNA (gDNA), which was extracted to maximize bacterial DNA yield from specimens while keeping background amplification to a minimum83–85. Libraries were constructed from each sample using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeqX platform with the 2 × 150 bp paired-end read protocol. Sequencing reads were derived from raw BCL files which were retrieved from the sequencer and called into fastqs by Casava v1.8.3 (Illumina). Appropriate read preparation steps, such as quality control, trimming and filtering and host DNA removal prior to further analysis were performed using an in-house pipeline (Statistical analysis section).

T cell Receptor Repertoire Sequencing (TCR)

DNA isolated from tumor swabs was submitted for TCR sequencing to the Cancer Genomics Laboratory at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). Survey depth sequencing was performed using the Adaptive Biotechnologies immunoSEQ human T cell receptor beta (hsTCRB) Kit, Version 3 (Adaptive Biotechnologies, ISK10101). Two replicates of 200 ng DNA per sample were prepared for qPCR with the V- and J-gene specific primers provided in the immunoSEQ hsTCRB kit and the QIAGEN Multiplex PCR Kit (Qiagen, catalog no. 206145). First, 31 cycles of qPCR were performed on all replicates, then, sample manifest barcodes generated with immuSEQ Analyzer and Illumina adapters were added to each PCR replicate for eight additional qPCR cycles. The libraries were purified using a bead-based system to remove residual primers, pooled at equal volume, and checked for quality control with Agilent D1000 screen tapes to determine the size-adjusted concentration. The libraries were quantified with the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 and the KAPA Biosystems library quantification kit, using manufacturer's instructions.

On the basis of the qPCR results, approximately 15 pmol/L of the pooled libraries were loaded onto the Miseq Sequencing System for a single end read which includes a 156-cycle Read 1 and a 15-cycle Index 1 read run. Raw sequences output from the Miseq were transferred to Adaptive's immunoSEQ Data Assistant, where the data were processed to report the normalized and annotated TCRB repertoire profile for each sample.

Isolation of L. iners strains from patient tumors

Culture swabs were collected from tumors and immediately placed in an anaerobic transport bag (BD 260683). Within 30 minutes of collection, tumor swabs were plated onto a TSA plate (BD Biosciences, Cat# 221239) and a MRS plate (Moltox, Cat# 51–40S020.140) and incubated at 37°C in anaerobic conditions for 3–5 days. Bacterial growth from plates was sub-cultured until single colonies could be isolated. MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy was used to identify the bacterial isolate species and performed according to the standard protocol described in the Bruker MALDI-TOF user manual.

Generation of patient-derived organoids

Patient-derived organoids were generated as described by Lõhmussaar et al86, with several modifications. Cervical cancer tissue was mechanically minced using scalpels, followed by digestion in a dissociation mixture (1 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma) and 0.4 mg/ml Hyaluronidase (Sigma) in complete RPMI medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, for 1.5 hours at 37°C in a water bath shaker. The resulting cells were centrifuged down at 350g for 5 min, followed by adding 1–5ml of Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) supplemented with 100ug/ml DNase I (Sigma) and digesting the cell clumps for 8–10 min at 37°C waterbath shaker. The resulting cell suspensions were washed three times with AdDF+++ (Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1x Glutamax, 10 mM HEPES, and penicillin-streptomycin), and erythrocytes were lysed in Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Roche). The cells and small cell clumps were embedded into Basement Membrane Extract (BME, Cultrex BME RGF type 2, Trevigen) and plated in 10 ul-volume droplets on a pre-warmed 24-well suspension culture plates and allowed to solidify at 37°C for 30 min before addition of full growth medium (AdDF+++ supplemented with 1% Noggin conditioned medium (made in-house), 10% of RSPO1 conditioned medium (made in-house), 1x B27 supplement (GIBCO), 2.5 mM nicotinamide (Sigma), 1.25 mM n-Acetylcystein (Sigma), 10 mM ROCK inhibitor (Abmole), 500 nM A83–01 (Tocris), 10 mM forskolin (Bio-Techne), 25 ng/ml FGF7 (Peprotech), 100 ng/ml FGF10 (Peprotech) and 1 mM p38 inhibitor SB202190 (Sigma), 50 ng/ml EGF (Peprotech) and 100 mg/ml Primocin (InvivoGen)). For splitting, organoids were pipetted up and down 300 times using an electronic pipettor through a small-bore pipette tip to break up the BME and separate organoids from the BME. After centrifugation, organoids were dissociated with TrypLE (Gibco) for 5 min in a cell culture incubator. The cells were pipetted up and down by 100 to break up the remaining cell clumps and organoids into single cells. The approximate splitting ratio was 1:4 every two weeks.

Immunostaining and imaging of organoids

Organoids were fixed 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room tempreture followed by dehydration and paraffin embedding. Serial sections were cut as 5 μm and hydrated before staining. Sections were subjected to PAS staining following the manufacturer’s instructions or immunohistochemical staining by using overnight incubation with antibodies raised against P63 (Abcam), KI67 (Abcam), and CK13 (Abcam). The antigen retrieval was performed in citric acid solution (pH 6.0). Fluorescent images were acquired on Axio Observer microscope (Zeiss). The bright view images were taken on Cytation5 Cell Imaging Multimode Reader (Agilent). For organoids size counting, the diameter of each PDO in the image larger than 20 μm was taken in count using GEN 5 software.

Lactobacilli Treatments and cell viability assay

Bacterial strains were cultured under anaerobic conditions at 37°C and 190 rpm for 3–4 days until the cells reached a density of approximately 1 × 109 cells/mL87. The cultures were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 40 min at 20°C. The supernatants were sterile-filtered to prepare the CFS. After centrifugation, the bacterial pellets were resuspended in PBS to a final concentration of 108/ml and killed using under UV-light for 1h.

For CFS treatment, HeLa, SiHa, and CaSki cells and cervical cancer-derived primary cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 106 cells/well and left to adhere overnight. Once adhered, the cell media was changed to 20% v/v CFS and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 for two weeks; passages occurred once a week. After incubation, cells were seeded in 96 well plates at 1000 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight. The cells were then treated with or without ionizing radiation and cisplatin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# P4394), 5-fluorouracil (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# F6627), gemcitabine (Selleck Chemical LLC S1149100MG), or a combination, as indicated in the figures. After all treatments, cells were allowed to grow for 4–6 days in 20% CFS v/v culture medium until the negative control wells reached approximately 75% confluence before cell viability was assessed. For PDOs, single cells were resuspended in ice cold BME (Trevigen, Cat#3533-005-02) and irradiated as indicated, and then the cells were seeded as 5 µL of BME in a U-bottom 96-well microplate. After 2–3 days, when small organoids emerged from single cells, 20% CFS diluted in full growth medium was added to the wells and incubated overnight for 16h, followed by cisplatin treatments for 1h. After all treatments, the medium was replaced with a full growth medium containing 20% v/v CFS and incubated for 14 days. The PDO in BME were then subjected to a cell viability assay. For the dead bacteria test, cervical cancer-derived primary cells were seeded into 96-well microplates and treated with irradiation or cisplatin. After washing with full growth medium, the dead bacterial pellets were diluted and added to the cells at a density of 160 CFU/cell and co-cultured with the cells for five days, followed by a cell viability assay.

For HeLa, CaSki, SiHa, and cervical cancer-derived primary cells (B1188), a cell viability assay was performed using CellTiter-Glo according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, CellTiter-Glo Reagent (Promega) was applied to the culture medium at a 1:1 ratio. The CellTiter-Glo 3D Reagent (Promega) was applied to the PDOs. The plates were shaken every 5 minutes and incubated for 30 minutes. The luminescence was measured using a Perkin Elmer Victor X3 plate reader. Percent cell viability for each treatment group was calculated by normalizing luminescence readings to those of the non-treated IR or chemo group.

Immunofluorescence staining

For γH2AX and panCK staining, cells were fixed in ice cold methanol for 5 min at room temperature and washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After fixation, the cells were incubated with antibody overnight in cold room. After primary antibody incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody (Invitrogen) containing DAPI for 1 hr at room temperature. Finally, cells were mounted in mounting solution ProLong Gold (Invitrogen). Fluorescent images of panCK were acquired on Axio Observer microscope (Zeiss). Image acquisition of γH2AX was performed with a Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multimode Reader. Microscopy image analyses were performed using the GEN 5 software. Nuclei were segmented using the DAPI channel and the resulting regions of interest transferred to the fluorescence channel of interest (488 for gammaH2AX). Prism 9 (GraphPad Software) was used to calculate P values based on T-test analyses. Data were considered statistically significant for P values < 0.05.

Bulk RNA sequencing

RNA samples were submitted to Cancer Genomics Center at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. The RNA sample quality was assessed by RNA ScreenTape on a Tapestation (Agilent Technologies Inc., California, USA) and quantified by Qubit 2.0 RNA HS assay (ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA). Paramagnetic beads coupled with oligo d(T)25 are combined with total RNA to isolate poly(A)+ transcripts based on NEBNext® Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module manual (New England BioLabs Inc., Massachusetts, USA). Prior to first strand synthesis, samples are randomly primed (5´ d(N6) 3´ [N=A,C,G,T]) and fragmented based on manufacturer’s recommendations. The first strand is synthesized with the Protoscript II Reverse Transcriptase with a longer extension period, approximately 30 minutes at 42°C. All remaining steps for library construction were used according to the NEBNext® Ultra™ II Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England BioLabs Inc., Massachusetts, USA). Final libraries quantity was assessed by Qubit 2.0 (ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA) and quality was assessed by TapeStation HSD1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies Inc., California, USA). Final library size was about 500bp with an insert size of about 350bp. Illumina® 8-nt dual-indices were used. Equimolar pooling of libraries was performed based on QC values and sequenced on an Illumina® [NovaSeq S4] (Illumina, California, USA) with a read length configuration of 150 PE for [40] M PE reads per sample (20M in each direction).

Lactate isoform treatment of cell lines

Stock solutions of L-lactic acid, D-lactic acid, sodium L-lactate and sodium D-lactate were made at the same concentration, 4M. We used 20 mM lactic acid or lactate to culture the cells for two weeks. And the cells were seeded 1000 cells/well in a 96-well plate for chemoradiation treatments. After treatments, the cells were cultured in medium containing 20 mM lactic acid or lactate for 3–5 days, followed by CellTiterGlo assay.

DNA Synthesis Assay

Cancer derived primary cells were cultured in either broth (control), NC-L. Iners CFS, or CC-L. Iners CFS supplemented culture medium for 2 weeks, and then re-seeded and cultured for 1 day, followed by IR and serial timepoints of recovery. The cells were subjected to the DNA synthesis analysis using the Click-iT™ EdU Alexa Fluor™ 488 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Invitrogen, cat. No. C10425). EdU at a final concentration of 40 µM was applied for 15 minutes, then cells were recovered for 60, 90, 120, 150 min and fixed and stained following the manufacturer’s instructions with the PI staining step included. Cells were analyzed on a Thermo Fisher Attune Nxt Flow Cytometer using the 488 nm BL3 filter for EdU and 638 RL2 filter for PI.

Tumor and Clinical isolate Metabolomics

To determine the relative abundance of polar metabolites in samples, extracts were prepared and analyzed by ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). Metabolites were extracted using ice-cold 0.1% Ammonium hydroxide in 80/20 (v/v) methanol/water. Extracts were centrifuged at 17,000 g for 5 min at 4°C, and supernatants were transferred to clean tubes, followed by evaporation to dryness under nitrogen. Dried extracts were reconstituted in deionized water, and 5 μL was injected for analysis by ion chromatography (IC)-MS. IC mobile phase A (MPA; weak) was water, and mobile phase B (MPB; strong) was water containing 100 mM KOH. A Thermo Scientific Dionex ICS-5000+ system included a Thermo IonPac AS11 column (4 µm particle size, 250 × 2 mm) with column compartment kept at 30°C. The autosampler tray was chilled to 4°C. The mobile phase flow rate was 350 µL/min and gradient from 1mM to 100mM KOH was used. The total run time was 60 min. To assist the desolvation for better sensitivity, methanol was delivered by an external pump and combined with the eluent via a low dead volume mixing tee. Data were acquired using a Thermo Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Mass Spectrometer under ESI negative ionization mode at a resolution of 240,000.

Analysis of D/L-Lactate levels