Abstract

Detection and analysis of pathogens by PCR plays an important role in infectious disease research. The value of these studies would be diminished if nuclear material from dead parasites were found to remain in circulation for extended periods and thus result in positive amplification. This possibility was tested in experimental rodent malaria infections. Blood samples were obtained from infected mice during and following drug or immune clearance of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi parasitemias. Detection of parasite DNA by a sensitive Plasmodium-specific PCR amplification assay was associated with the presence of viable parasites, as detected by subinoculation. No parasite DNA could be detected by PCR 48 h after the injection of killed parasites into mice. Nuclear material from parasites removed by drug or immune responses is rapidly cleared from the circulation and does not contribute significantly to amplification. Thus, results from PCR analysis of malaria-infected blood accurately reflect the presence of live parasites.

Detection and analysis of Plasmodium parasites by PCR are done in numerous investigations. PCR assays are more sensitive than microscopy and are therefore often used to detect the parasite and identify the species (3, 17, 18, 29, 32, 33). The specificity of PCR has also been exploited for the analysis of parasite populations. Investigations of the diversity of Plasmodium falciparum from fresh field isolates have been greatly improved by the analysis of polymorphic genetic markers through PCR (7, 13, 25, 34, 36). DNA amplification is thus becoming an important tool for the study of malaria parasites. This technique is also being increasingly applied to other parasitic diseases, as well as bacterial and viral infections. As a result of this high sensitivity, DNA amplification is often observed in the absence of microscopically demonstrable parasites. Concern has therefore been expressed that, in some cases, the target of PCR amplification might be circulating DNA derived from dead parasites or from parasites ingested by peripheral phagocytic cells. To resolve this issue, one must investigate whether positive amplification can be obtained in the absence of viable parasites.

This issue was addressed experimentally with mice by using P. chabaudi chabaudi. The efficiency of clearance of nonviable parasites was ascertained in three distinct experiments. In a first instance, parasites killed by freeze-thawing were injected directly into the bloodstream. The two other sets of experiments are representative of parasite clearance under natural conditions: (i) elimination of parasites by drug treatment and (ii) resolution of parasitemia by immune mechanisms. Throughout the experiments, blood was collected daily and each sample was divided equally, with one aliquot used for PCR analysis and the other subinoculated into reporter mice to test for the presence of viable parasites. The sensitivity of a previously described PCR detection assay, in which conserved sequences of the small-subunit rRNA (ssrRNA) gene are targeted (14), was improved by the addition of a nested reaction. We have found that positive amplification was associated with the presence of viable parasites as detected by subinoculation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

CBA/Ca male mice 3 to 4 months old and weighing 24 to 26 g at the time of primary infection were used throughout the study. Infectivity tests were done by using outbred Parkes’ male (reporter) mice. All mice were obtained, housed, and used as previously described (16).

Parasites.

P. c. chabaudi AS-parasitized erythrocytes (PE), prepared as previously described (16), were used to initiate primary infections in normal mice, to reinfect immune mice in order to produce hyperimmune animals, and to challenge these or normal mice so as to provide samples for DNA analysis. Unless otherwise stated, all infections were initiated by the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route using defined numbers of PE.

Blood collection and analysis.

Thin tail blood smears were collected daily, methanol fixed, and Giemsa stained. Parasites were enumerated by microscopic examination, and the data was presented as log parasitemia for individual experimental mice or, where appropriate, as log geometric mean parasitemia for groups of animals. The raw data was transformed and evaluated as previously described (16). Blood samples for subinoculation and PCR analysis were also collected from individual mice immediately before clearance of parasites was initiated and on a regular basis thereafter until the experiment was terminated. For each sample, 20 μl of blood was taken from individual mice from the tip of the tail and mixed into 400 μl of Krebs saline-glucose-heparin (5). All of the experiments were repeated at least twice, and similar results were obtained.

Infectivity testing.

A 200-μl volume of each sample obtained as described above was then immediately injected i.p. into a reporter mouse. We have established by using serial dilution of parasites in whole blood, that patent infections are consistently observed following inoculation with very few (1 to 10) PE. Infections in reporter mice were assessed by microscopy (Giemsa-stained tail blood smears) for 14 days after the inoculation before being considered negative.

PCR template preparation.

Parasites in the remaining 200 μl were released by addition of 1 μl of saponin (10%, wt/vol) and concentrated by centrifugation (8,000 × g for 5 min). The supernatant was discarded, and the parasite pellet was stored at −60°C before template preparation. DNA was prepared by resuspending the pellet in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2.0 mg of pronase E per ml). The DNA was purified by phenol extraction followed by ethanol precipitation (24) and resuspended in 10 μl of water. Mouse genomic DNA was used as negative controls.

PCR analysis.

Amplification was carried out in a total volume of 20 μl containing, in all cases, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 0.1 mg of gelatin per ml, 2 mM MgCl2, 125 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 0.4 U of AmpliTaq polymerase. In the first amplification reaction of the nested PCR protocol, 5 μl of the DNA template prepared as described above was used to initiate the amplification with 250 nM (each) rPLU1 (5′-TCA AAG ATT AAG CCA TGC AAG TGA) and rPLU2 (5′-ATC TAA GAA TTT CAC CTC TGA CAT CTG). In the second reaction, 1 μl of the product from the first reaction was used to initiate amplification with a 250 nM concentration of each of the previously described primers (14) rPLU3 (5′-TTT TTA TAA GGA TAA CTA CGG AAA AGC TGT) and rPLU4 (5′-TAC CCG TCA TAG CCA TGT TAG GCC AAT ACC). The cycling parameters were as follows. Reaction mixtures were heated to 95°C for 5 min prior to cycling at 62°C (first reaction) or at 64°C (second reaction) for 2 min of annealing, 72°C for 2 min of extension, and 94°C for 1 min of denaturation. We carried out 25 cycles for the first reaction and 30 for the second. The amplification cycles were completed by one further annealing step, followed by a 5-min extension step, and the product was stored at 4°C and analyzed as described in the figure legend.

Clearance experiments. (i) Injection of freeze-thawed material.

The parasites were obtained by total exsanguination of an infected mouse. After removal of the plasma, the erythrocytes were then frozen as a thin shell of material in a round-bottom flask in a dry ice-methanol bath (−65°C) and kept at this temperature for 2 min before being rapidly thawed at 37°C for 2 min. This freeze-thaw cycle was repeated four times. An aliquot of this material was removed and used as a positive PCR control, and the remainder was equally divided and injected intravenously into two recipient mice. Each mouse received 9.5 × 108 freeze-thawed PE.

(ii) Drug treatment.

Infections were initiated with 5 × 104 P. c. chabaudi AS PE in a group of five mice. On day 10 postinfection, the mice were injected i.p. with pyrimethamine (Sigma) at 30 mg/kg of body weight daily up to and including day 16.

(iii) Immune clearance.

Five mice with homologous immunity to P. c. chabaudi AS were obtained as follows. Following clearance of a primary infection initiated by inoculation with 5 × 104 PE, three further inoculations of PE (3 × 108, 4 × 108, and 1 × 109, respectively) were performed on days 128, 149, and 160. In all cases, parasites from these booster infections were cleared within 6, 5, and 3 days, respectively. On day 225, blood samples were removed from two of these mice for PCR-subinoculation analysis in order to confirm that no parasites were present in the circulation before a challenge inoculation with 6 × 108 PE.

RESULTS

Specificity and sensitivity of the PCR assay.

The detection of parasites was achieved by PCR amplification using oligonucleotide primers which hybridize to sequences conserved in the ssrRNA genes of all Plasmodium organisms. A nested PCR approach was used to enhance the sensitivity of the assay. Amplification of a fragment of approximately 230 bp was obtained for all of the parasite species tested, and no PCR product could be detected when human or mouse DNA was present alone. The parasites tested included all of the species infecting humans (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale) and all of the species and subspecies infecting rodents (P. c. chabaudi, P. c. adami, P. berghei, P. vinckei vinckei, P. v. lentum, P. v. petteri, P. yoelii yoelii, P. y. nigeriensis, and P. y. killicki). The sensitivity of detection was close to the maximum theoretical value of 1 parasite per sample, as determined by amplification of purified DNA from serial dilutions of known quantities of viable P. c. chabaudi AS parasites in whole blood. Ten-microliter blood samples expected to contain one PE consistently gave positive amplification. The intensity of the amplified fragment was, as expected in nested PCR amplification, the same with as few as 1 parasite to 10,000 parasites present in the reaction mixture but faded rapidly at lower parasite contents (there are less than 10 ssrRNA genes per genome).

Parasite clearance. (i) Injection of freeze-thawed parasites.

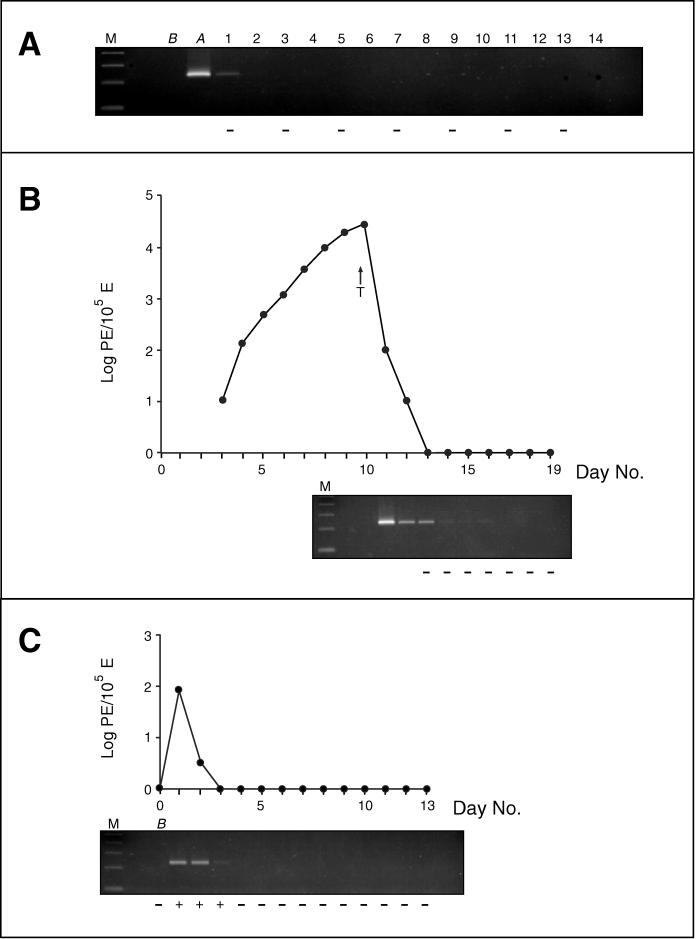

In a first experiment, freeze-thawed P. c. chabaudi AS parasites were injected into two normal mice in order to determine the rate of clearance of DNA derived from dead parasites. The mice were sampled for PCR analysis immediately before and after the injection and daily for the next 13 days. Subinoculations were performed on day 1 and then on alternate days. The freeze-thawed material injected did not contain any viable parasites, as demonstrated by the fact that patent parasitemia could not be detected in any of the reporter mice injected with the daily samples. Moreover, on day 14, the experimental animals were sacrificed and exsanguinated, and all of the blood from each mouse was equally divided and injected i.p. into two reporter mice which also remained negative. The PCR assay proved positive for the sample taken immediately following the injection of the freeze-thawed material and that taken 24 h later. Specific amplification of Plasmodium DNA from any later sample was not observed (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Following the addition of 5 μl of loading buffer, 15 μl of the PCR product was electrophoresed on a 3% MetaPhor agarose gel (Flowgen Instruments Ltd.) in TBE buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM boric acid, 5 mM EDTA) and visualized by UV transillumination after ethidium bromide staining. Molecular weight markers (lanes M) are a 100-bp ladder; the size of the lowest band visible is 100 bp. Results (+ or −) of subinoculations are given for reporter mice below each gel. The gels and the subinoculation results are aligned under the corresponding day when the sample analyzed was collected. (A) PCR and subinoculation analyses of blood samples obtained after injection of freeze-thawed P. c. chabaudi AS parasites into a representative mouse. The sample taken from the mouse before injection of parasite material is designated B, and the one taken immediately after is A. Values above the gel are the numbers of days following the injection of parasite material. (B) Parasitemia curve and PCR-subinoculation analyses of a representative mouse in which the parasitemia was cleared by pyrimethamine treatment (initiated on day 10, as indicated by the arrow designated T). (C) Parasitemia curve and PCR-subinoculation analyses of parasite clearance in a representative hyperimmune mouse. The challenge inoculum was administered immediately after collection of sample B. E, erythrocytes.

(ii) Drug treatment.

In another experiment, the presence of parasite DNA in the circulation following the elimination of parasites by drug treatment was determined. Samples for subinoculation testing were obtained from two mice following drug treatment and after the parasites could not be detected microscopically (days 13 to 19 inclusive). Viable parasites were detected by subinoculation on day 13 in only one mouse. In only one of the other reporter mice, a single parasite was seen 7 days after the subinoculation with the blood samples collected on day 15. This reporter mouse, however, remained negative throughout the duration of the experiment. This observation was not repeated for any of the reporter mice from the duplicate experiment. PCR analysis was performed on samples collected from day 11 to day 19 inclusive and proved negative for day +17 on. The PCR product obtained from the day 14 to 16 samples was of very low intensity and might not be reproduced faithfully in Fig. 1B.

(iii) Immune clearance.

In a final experiment, the possibility that parasite DNA remained in the peripheral blood after removal of parasites by immune mechanisms was ascertained by injecting 6 × 108 viable parasites into two hyperimmune mice. These mice were then sampled for subinoculation and PCR analysis for the next 13 days. Patent parasitemia was only observed in reporter mice inoculated with blood taken on days 1 to 3. PCR amplification was also only observed for samples taken on days 1 to 3 (Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

Malaria infections are chronic and often can last for many months or years. When these infections remain untreated or are suboptimally treated, patent parasitemic episodes punctuate relatively long periods in which no parasites can be demonstrated microscopically. Throughout the course of the infection, parasites are destroyed mainly by immune mechanisms or drug treatment. Damaged or dying parasites also arise when merozoites fail to reinvade or if the physiological environment of the host is unsuitable for parasite development (e.g., in the presence of fever, nutritional deficiencies, or hemoglobinopathies). The removal of these parasites is undertaken primarily by circulating phagocytic cells and spleen macrophages. The abilities of parasite-specific PCR assays to detect low-grade parasitemias and to characterize the composition of the parasite populations are being increasingly exploited in diverse epidemiological studies. In addition to providing accurate prevalence data (4, 23, 27, 28), important insights into the biology of P. falciparum are derived from the PCR analysis of parasite dynamics (9, 12), morbidity associations (8, 11, 19), transmission (2, 20, 22), and the emergence of drug resistance (1, 10, 15, 26, 35). The role of PCR detection and analysis in the evaluation of vaccine trials is now recognized and is likely to expand in the future (6, 30). The possibility that any of the results obtained from PCR analysis might be due to parasite DNA lingering in the circulation long after the parasites have been eliminated has often been raised. If this were often the case, some conclusions derived from amplification data would have to be revised. Experimental infections of mice were used to address this issue through the analysis of peripheral blood obtained following clearance of very high parasite burdens (rarely seen in human infections) either by chemotherapy or through immune mechanisms. Parasites in individual blood samples were detected by using a sensitive nested PCR assay, and their viability was determined by subinoculation. It was found that parasite material is cleared very quickly from the circulation and that the PCR signal is associated mainly with the presence of viable parasites. In a few samples, the PCR and subinoculation results were not in agreement. Twenty-four hours following injection of freeze-thawed parasite material, PCR amplification was positive but subinoculation was not (Fig. 1A); thus, full clearance of the DNA present in this material from the circulation requires more than 24 h but less than 48 h. In the drug clearance experiment, the PCR assay was positive on days 13 to 16 while subinoculation proved negative (Fig. 1B). The prolonged detection of parasites by PCR alone, observed only in the drug clearance experiment, might be due to the presence of live but drug-damaged parasites, which would be unable to initiate an infection in a reporter mouse. This is supported by the microscopic detection of a single parasite once in a reporter mouse (inoculated with day 15 blood, Fig. 1B), which did not develop an infection. Another possible explanation rests with the exquisite sensitivity of both methods of parasite detection; thus, when only one or two parasites are present in a sample, there is a probability that one of the aliquots analyzed would not contain any parasites. This all-or-none effect has been previously noted in the PCR detection of parasites (29). Indeed, a negative PCR amplification and a positive subinoculation result were obtained with one sample from the immune clearance experiment (data not shown). These few cases, however, occurred only with samples obtained soon after the last sample found to be positive by both methods.

In malaria, parasites are removed by circulating and reticuloendothelial phagocytes (31). In the present experiments, large numbers of parasites were eliminated by drug treatment or immunity. Nonetheless, positive PCR amplification was associated with the presence of viable parasites. Thus, either parasite nuclear material is degraded rapidly after phagocytosis, or the loaded phagocytic cells are not found in the peripheral circulation.

Although the experiments were necessarily performed with mice, since human experimentation is ethically excluded, the conclusion drawn should be equally applicable to the clearance of parasites in human infections. Some indirect evidence derived from the PCR analysis of P. falciparum populations in longitudinal blood samples supports this view. Genetically different populations are often seen in the circulation on consecutive days or for only part of the sampling period, in both untreated and treated infections (12, 15). The fact that a particular parasite line is no longer detectable by PCR analysis of peripheral blood following natural clearance or clearance through drug treatment implies that material from this line is quickly removed from the circulation. In a separate study, it was also found that DNA from asexual parasites is also removed within 48 h after ingestion by anopheline mosquitoes, as determined by nested PCR amplification (21).

We therefore conclude that specific amplification of parasite sequences from blood samples accurately reflects the presence of viable or very recently killed or damaged parasites. These results add further confidence to information obtained by PCR analysis of malaria parasites. It remains to be established whether these conclusions are applicable to other diseases caused by blood-dwelling parasites, such as leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, and filariasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank K. Neil Brown for support, highly valuable comments and suggestions, and reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babiker H, Ranford-Cartwright L, Sultan A, Satti G, Walliker D. Genetic evidence that RI chloroquine resistance of Plasmodium falciparum is caused by recrudescence of resistant parasites. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:328–331. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babiker H A, Ranford-Cartwright L C, Currie D, Charlwood J D, Billingsley P, Teuscher T, Walliker D. Random mating in a natural population of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1994;109:413–421. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker R H J, Banchongaksorn T, Courval J M, Suwonkerd W, Rimwungtragoon K, Wirth D F. A simple method to detect Plasmodium falciparum directly from blood samples using the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:416–426. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottius E, Guanzirolli A, Trape J-F, Rogier C, Konate L, Druilhe P. Malaria: even more chronic in nature than previously thought; evidence for subpatent parasitaemia detectable by the polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown K N, Jarra W, Hills L A. T cells and protective immunity to Plasmodium berghei in rats. Infect Immun. 1976;14:858–871. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.4.858-871.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng Q, Lawrence G, Reed C, Stowers A, Ranford-Cartwright L, Creasy A, Carter R, Saul A. Measurement of Plasmodium falciparum growth rates in vivo: a test for malaria vaccine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:495–500. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contamin H, Fandeur T, Bonnefoy S, Skouri F, Ntoumi F, Mercereau-Puijalon O. PCR typing of field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:944–951. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.944-951.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contamin H, Fandeur T, Rogier C, Bonnefoy S, Konate L, Trape J-F, Mercereau-Puijalon O. Different genetic characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum isolates collected during successive clinical malaria episodes in Senegalese children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:632–643. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daubersies P, Sallenave-Sales S, Magne S, Trape J-F, Contamin H, Fandeur T, Rogier C, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Druilhe P. Rapid turnover of Plasmodium falciparum populations in asymptomatic individuals living in a high transmission area. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:18–26. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duraisingh M T, Drakeley C J, Muller O, Bailey R, Snounou G, Targett G A T, Greenwood B M, Warhurst D C. Evidence for selection for the tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr 1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum by chloroquine and amodiaquine. Parasitology. 1997;114:205–211. doi: 10.1017/s0031182096008487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelbrecht F, Felger I, Genton B, Alpers M, Beck H-P. Plasmodium falciparum: malaria morbidity is associated with specific merozoite surface antigen 2 genotypes. Exp Parasitol. 1995;81:90–96. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Färnert A, Snounou G, Ingegerd R, Björkman A. Daily dynamics of Plasmodium falciparum subpopulations in asymptomatic children in a holoendemic area. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:538–547. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felger I, Tavul L, Beck H-P. Plasmodium falciparum: a rapid technique for genotyping the merozoite surface protein 2. Exp Parasitol. 1993;77:372–375. doi: 10.1006/expr.1993.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulier E, Pétour P, Snounou G, Nivez M-P, Miltgen F, Mazier D, Rénia L. A method for the quantitative assessment of malaria parasite development in organs of the mammalian host. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irion, A., I. Felger, S. Abdullah, T. Smith, R. Mull, M. Tanner, C. Hatz, and H.-P. Beck. Distinction of recrudescences from new infections by PCR-RFLP analysis in comparative trial of CGP56697 and chloroquine in Tanzanian children. Trop. Med. Int. Health, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Jarra W, Brown K N. Protective immunity to malaria: studies with cloned lines of Plasmodium chabaudi and P. berghei in CBA/Ca mice. I. The effectiveness of inter- and intra-species specificity of immunity induced by infection. Parasite Immunol. 1985;7:595–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1985.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaureguiberry G, Hatin I, Auriol L D, Galibert G. PCR detection of Plasmodium falciparum by oligonucleotide probes. Mol Cell Probes. 1990;4:409–414. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(90)90031-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kain K C, Lanar D E. Determination of genetic variation within Plasmodium falciparum by enzymatically amplified DNA from filter paper disks impregnated with whole blood. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1171–1174. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.6.1171-1174.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ntoumi F, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Ossari S, Luty A, Reltien J, Georges A, Millet P. Plasmodium falciparum: sickle-cell trait is associated with higher prevalence of multiple infections in Gabonese children with asymptomatic infections. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:39–46. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul R E L, Packer M J, Walmsley M, Lagog M, Ranford-Cartwright L C, Paru R, Day K P. Mating patterns in malaria parasite populations of Papua New Guinea. Science. 1995;269:1709–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.7569897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto J, Arez A P, Franco S, de Rosario V E, Palsson K, Jaenson T G T, Snounou G. Simplified methodology for PCR investigation of midguts from mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae complex, in which the vector and Plasmodium species can both be identified. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:217–219. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1997.11813132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranford-Cartwright L C, Balfe P, Carter R, Walliker D. Frequency of cross-fertilization in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1993;107:11–18. doi: 10.1017/s003118200007935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roper C, Elhassan I M, Hviid L, Giha H, Richardson W, Babiker H, Satti G M H, Theander T G, Arnot D E. Detection of very low level Plasmodium falciparum infections using the nested polymerase chain reaction and a reassessment of the epidemiology of unstable malaria in Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:325–331. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snewin V A, Herrera M, Sanchez G, Scherf A, Langsley G, Herrera S. Polymorphism of the alleles of the merozoite surface antigens MSA1 and MSA2 in Plasmodium falciparum wild isolates from Colombia. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90070-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snounou, G., and H.-P. Beck. The use of PCR-genotyping in the assessment of recrudescence or reinfection after antimalarial drug treatment. Parasitol. Today, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Snounou G, Pinheiro L, Gonçalves A, Fonseca L, Dias F, Brown K N, de Rosario V E. The importance of sensitive detection of malaria parasites in the human and mosquito hosts in epidemiological studies, as shown by the analysis of field samples from Guinea Bissau. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:649–653. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90274-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown K N. Identification of the four human malaria species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of a high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu X P, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, de Rosario V E, Thaithong S, Brown K N. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoute J A, Slaoui M, Heppner D G, Momin P, Kester K E, Desmons P, Wellde B T, Garçon N, Krzych U, Marchand M, Ballou W R, Cohen J D. A preliminary evaluation of a recombinant circumsporozoite protein vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:86–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talliaferro W H. Immunity to malaria infections. In: Boyd M F, editor. Malariology. A comprehensive survey of all aspects of this group of diseases from a global standpoint. II. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1949. pp. 935–965. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tirasophon W, Ponglikitmongkol M, Wilairat P, Boonsaeng V, Panyim S. A novel detection of a single Plasmodium falciparum in infected blood. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tirasophon W, Rajkulchai P, Ponglikitmongkol M, Wilairat P, Boonsaeng V, Panyim S. A highly sensitive, rapid, and simple polymerase chain reaction-based method to detect human malaria (Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax) in blood samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:308–313. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viriyakosol S, Siripoon N, Petcharapirat C, Petcharapirat P, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown K N, Snounou G. Genotyping of Plasmodium falciparum isolates by the polymerase chain reaction and potential uses in epidemiological studies. Bull W H O. 1995;73:85–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Seidlein L, Jaffar S, Pinder M, Haywood M, Snounou G, Gemperli B, Gathmann I, Royce C, Greenwood B. Treatment of African children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria with a new antimalarial drug, CGP 56697. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1113–1116. doi: 10.1086/516524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wooden J, Gould E E, Paull A T, Sibley C H. Plasmodium falciparum: a simple polymerase chain reaction method for differentiating strains. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90180-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]