Abstract

Pif1 helicase is a molecular motor enzyme and is conserved from yeast to mammals. It translocates on ssDNA with a directional bias (5′→3′) and unwinds duplexes using the energy obtained from ATP hydrolysis. Pif1 is involved in dsDNA break repair, resolution of G-quadruplex (G4) structures, negative regulation of telomeres, and Okazaki fragment maturation. An important property of this helicase is to exert force and disrupt protein-DNA complexes, which may otherwise serve as a barrier to various cellular pathways. Previously, Pif1 has been reported to displace streptavidin from biotinylated DNA, Rap1 from telomeric DNA, and telomerase from DNA ends. Here we have investigated the ability of S. cerevisiae Pif1 helicase to disrupt protein barriers from G-quadruplex and telomeric sites. Yeast chromatin-associated transcription co-activator, Sub1 was characterized as a G4 binding protein. We found evidence for physical interaction between Pif1 helicase and Sub1 protein. Here we demonstrate that Pif1 is capable of catalyzing the disruption of Sub1-bound G4 structures in an ATP-dependent manner. We also investigated Pif1-mediated removal of yeast telomere-capping protein, Cdc13 from DNA ends. Cdc13 exhibits a high-affinity interaction with a 11mer derived from the yeast telomere sequence. Our results show that Pif1 uses its translocase activity to enhance dissociation of this telomere specific protein from its binding site. The rate of dissociation increased with an increase in helicase loading site length. Additionally, we examined the biochemical mechanism for Pif1-catalyzed protein displacement by mutating the sequence of the telomeric 11-mer on the 5’-end and the 3’-end. The results support a model whereby Pif1 disrupts Cdc13 from the ssDNA in steps.

Helicases exhibit several biochemical properties such as ATP binding and hydrolysis, DNA and or RNA binding, translocation on single-stranded nucleic acids and unwinding of duplex nucleic acid1,2. Coupling of many of these properties are essential for the cellular functions of helicases. Less studied is the ability of many helicases to displace proteins from nucleic acids,3–5 or push proteins along DNA6. One of the earliest examinations of a protein being dislodged from DNA or RNA was reported by Jankowsky et al., who demonstrated the disruption of an RNA-protein interaction by an RNA helicase7. The ability of helicases to produce force and disrupt protein-DNA complexes may facilitate the removal of protein barriers from DNA, which may otherwise serve as a roadblock to different cellular processes8. Genetic and biochemical evidence from various studies indicate that S. cerevisiae Pif1 helicase (referred to as Pif1) is capable of removing telomerase from DNA ends to regulate telomere length9–12. Rrm3, a Pif1 homolog in S. cerevisiae has been reported to disrupt non-nucleosomal protein-DNA complexes in vivo13,14. The human helicase FANCJ has been reported to dislodge the shelterin proteins TRF1 and TRF2 from telomeric duplex DNA in an RPA-stimulated manner15. This evidence suggests that protein displacement is an important biochemical function shared by many helicases that allows them to facilitate various cellular pathways, such as replication, repair or transcription through protein barriers. A study reported that human RECQL5 binds the Rad51 recombinase and displaces it from ssDNA using ATP hydrolysis16. This activity was shown to be required to suppress double-stranded break accumulation. The defects in disruption of protein-DNA complexes due to the activity of helicases was linked to tumorigenesis in humans, thereby suggesting the biological significance of this fundamental property of helicases.

Here we have investigated the ability of S. cerevisiae Pif1 helicase to remove protein roadblocks encountered at specific DNA sites such as G-quadruplex structures and telomeric regions. Two different yeast proteins were selected as model protein barriers for disruption studies: 1) Sub1 (a chromatin-associated protein involved in transcription activation) and 2) Cdc13 (a telomere-capping protein involved in the maintenance of chromosome ends). Previous studies have reported that Sub1 interacts with RNA polymerase II and III17–19 and it plays an essential regulatory role in transcription initiation and mRNA 3′-end formation20,21. Sub1 has been characterized as a G-quadruplex binding protein in yeast22. Since Pif1 helicase is known to process G4 structures and allow replication fork progression through quadruplex regions23,24, we tested if Sub1-G4 interaction presents an additional barrier to Pif1 activity.

Cdc13 is known to serve as an essential regulator of telomere maintenance as part of a heterotrimeric complex with Stn1 and Ten125,26. It protects the ends of the chromosomes from resection and activation of the DNA damage response27,28. Pif1 helicase has also been reported to overcome replication blocks at telomeric regions29–31. Importantly, Cdc13 binds to single-stranded telomeric DNA in a sequence selective manner, making it an excellent candidate for biochemical studies of helicase-catalyzed protein-DNA complex disruption. We have investigated the ability of Pif1 to disrupt Sub1 and Cdc13 from their respective binding sites. Additionally, by altering the preferred DNA sequence for Cdc13, we have explored the mechanism of helicase-catalyzed disruption of Cdc13-DNA complexes by Pif1 helicase.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Fluorescent dyes were obtained from Lumiprobe. Mutagenesis primers and DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The sequences are indicated in Table 1. Oligonucleotides were purified and radiolabeled as described32. DNA strands with G-rich sequences were incubated at 60 ⁰C for 2 h in 100 mM KCl and 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5 such that they form intramolecular quadruplexes. Using circular dichroism, the formation of G-quadruplex fold in DNA substrates was confirmed.

Table 1:

Substrates used for protein dissociation studiesa

| Name | Use | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| G4DNA | Fig. 1 | 5′- TTT TTT TTT TTT TT TGA GGG TGG GTA GGG TGG GTAA |

| Cy3Cy5-G4DNA | Fig. 3 | 5′-Cy5-(T)14 GAGGGTGGGTAGGGTGGGT-Cy3-3′ |

| Cy3-G4 DNA | Fig. 3 | 5′-(T)14 GAGGGTGGGTAGGGTGGGT-Cy3-3′ |

| Tel11 telomere seq | Fig. 4, 6 | 5′-GTGTGGGTGTG −3′ |

| 12 nt Mixed seq | Fig. 4 | 5′-CGCTGATGTCGC-3′ |

| Tel11 (G1C) | Fig. 6 | 5′-CTGTGGGTGTG −3′ |

| Tel11 (G7C/G9C) | Fig. 6 | 5′-GTGTGGCTCTG −3′ |

| G4 DNA Reporter (14TPu22–12bp) | Fig. 2 | 5′-(T)14GAGGGTGGGTAGGGTGGGTAACGCTGATGTCGC-3′ 5′-GCGACTACAGCG-3′ |

| 8Ttel11–16bp | Fig. 5 | 5′-(T)8 GTGTGGGTGTGCGCTGATGTCGCCTGG-3′ 5′-CCAGGCGACATCAGCG-3′ |

| 15Ttel11–16bp | Fig. 5, 7 | 5′-(T)15 GTGTGGGTGTGCGCTGATGTCGCCTGG-3′ 5′-CCAGGCGACATCAGCG-3′ |

| 30Ttel11–16bp | Fig. 8 | 5′-(T)30 GTGTGGGTGTGCGCTGATGTCGCCTGG-3′ 5′-CCAGGCGACATCAGCG-3′ |

| 15Ttel11(G1C)-16bp | Fig. 5 | 5′-(T)15 cTGTGGGTGTGCGCTGATGTCGCCTGG-3′ 5′-CCAGGCGACATCAGCG-3′ |

| 15Ttel11(G7C/G9C)-16bp | Fig. 5 | 5′-(T)15 GTGTGGcTcTGCGCTGATGTCGCCTGG-3′ 5′-CCAGGCGACATCAGCG-3′ |

Duplex forming regions of reporter substrates are indicated in italics. Base substitution is indicated in lowercase. Guanines with the potential to form G-quadruplex structures in KCl are underlined.

Expression and purification of yeast proteins (Pif1, Sub1 and Cdc13).

Yeast wtPif1 helicase and wtSub1 were overexpressed and purified as described previously22,33. The preparation of Sub1 variant was carried out using site-directed mutagenesis. The codon for a cysteine residue was introduced into the original pSUMO-Sub1 plasmid at the C-terminal end of the open reading frame by site-directed mutagenesis. Forward and reverse primers used for the site-directed mutagenesis were 5’-GAACAAGGCTGAAGACGACATAAGTGAAGAAGAATGCTAATAGTAAC TCGAGCACCACCACCACCAC-3’ and 5’-GTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTTACTATTAGCATTC TTCTTCACTTATGTCGTCTTCAGCCTTGTTC-3’, respectively (codon introduced for cysteine residue is underlined). The mutant plasmid was purified and the sequence was confirmed. The transformation, over-expression and purification of this variant Sub1 were performed in the same way as described for wtSub122.

Full-length Cdc13 was cloned into pSUMO vector with an N-terminal SUMO tag and it was over-expressed and purified from E. coli. The initial steps of its expression and purification are very similar to Pif1 purification described above. Following protein expression and preparation of the lysate, the clarified supernatant was passed through a TALON metal affinity columns (Clontech) and the SUMO tag was cleaved with Ulp1 protease. A second TALON column was used to remove the tag and the protease. The protein was further purified by loading onto a 10 ml Superdex 75 gel filtration column and was eluted using a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 2.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5. Fractions containing Cdc13 were pooled, dialyzed against buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 50 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5) and was finally passed through a heparin sepharose column. Bound protein was eluted on a linear gradient from 50 mM to 1 M NaCl. The purified recombinant Cdc13 was stored in −80 °C in storage buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM BME, 0.1 mM EDTA and 30% glycerol).

Fluorescence labeling of Sub1 variant with Cyanine dye.

The cysteine-labeled Sub1 protein (1 mg/ml) was dialyzed against degassed PBS (phosphate buffered saline), pH 7.4 at 4 °C. A 100 molar excess of TCEP (180 μg per 1 mg protein) was added to the protein solution to reduce any disulfide bonds. The vial was flushed with nitrogen gas and the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. The mono-reactive dye (Cy5 maleimide) was prepared by reconstituting in dimethylformamide at 1 mg/ml and added to the protein solution at a dye:protein molar ratio of 3:1. After mixing, the solution was incubated at room temperature for 1 h and subsequently, the reaction was allowed to occur overnight at 4 °C. Labeled Sub1 was subsequently separated from the excess, unconjugated dye by gel filtration chromatography using a G-25 Sephadex column. Cy5-labeled Sub1 has an excitation of 648 nm and emission wavelength of 665 nm. The concentration of the labeled protein was initially determined by UV absorbance. The degree of labeling (DOL) was calculated using Equation 1, where Ax is the absorbance value of the dye at the absorption maximum wavelength and ε is the molar extinction coefficient of the dye at the absorption maximum wavelength.

| (1) |

DNA binding assay.

Nitrocellulose and positively charged nylon membranes were soaked in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM MgCl2 for 1 hour. A sandwich containing from top to bottom: nitrocellulose (to capture protein-bound DNA), nylon (to capture free DNA), and filter paper was assembled in a dot-blot apparatus. The wells were washed with soaking buffer. 32P labeled G4DNA (1 nM) was incubated with increasing concentrations of enzyme (wtSub1 or Cy5-Sub1) in reaction buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 10 mM MgCl2) for 30 min. Samples were applied to the membranes followed by washing with soaking buffer. Membranes were exposed to a phosphor screen and imaged using a Typhoon Trio phosphorimager (GE Healthcare). The results were quantified using ImageQuant software and the fraction bound DNA was plotted against enzyme concentration using KaleidaGraph software. Data were fit to the quadratic equation to obtain the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values.

Fluorescence anisotropy assay for protein-protein interactions.

Experiments were conducted at 25 °C in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM BME and 0.1 mg/ml BSA. In a microtiter plate, a solution containing Cy5-Sub1 (50 nM) was incubated with increasing concentrations of Pif1 for 30 minutes. Fluorescence polarization values were measured using a PerkinElmer Life Sciences Victor3 V 1420 with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 642 and 665 nm, respectively. Fluorescence anisotropy was calculated and plotted versus the enzyme concentration using KaleidaGraph software. The data were fit to the quadratic equation to obtain the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Telomeric DNA sequence Tel11 and all the altered substrates (Table 1) with 5′ and 3′ base substitutions were radiolabeled with 32P. Different concentrations of Cdc13 (0–1000 nM) were prepared in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA). Each substrate (1 nM) was incubated with increasing concentrations of Cdc13 at 25 °C for 15 min. The full-length Cdc13 was used in all of our assays. The DNA-protein complexes were fractionated electrophoretically by EMSA on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel at 4 °C overnight. The gel with the protein-DNA complex separated from the free DNA was then exposed to a phosphor screen and imaged using a Typhoon Trio phosphorimager (GE Healthcare). The fraction of DNA bound was plotted against Cdc13 concentration using KaleidaGraph software. The data were fit to the Hill equation to obtain the apparent KD value for each substrate.

Gel-based reporter assay for helicase-mediated protein dissociation.

The reporter assays were conducted at 25 °C under multi-turnover conditions. The helicase reaction buffer for quadruplex unwinding and Sub1 dissociation consisted of 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT. In reporter assays involving G4 DNA reporter, 2 nM radiolabeled substrate was pre-incubated in the absence or presence of Sub1 as indicated in each figure. Pif1 (25 nM) was added to the reaction prior to the reaction initiation. The reaction was initiated by addition of 5 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2 and a 30-fold excess annealing trap. The dissociation reactions were quenched with 150 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 6% glycerol, 0.6 % SDS and 100 μM T50 at various time points. On the other hand, Cdc13 dissociation reactions were carried out in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA. They were performed at 25 °C under multi-turnover conditions. The reporter substrates (1 nM) containing canonical or altered telomere sequence for Cdc13 dissociation reactions were pre-incubated with the appropriate concentration of Cdc13 at room temperature for 5 min. Varying concentrations of Pif1 (30, 60, 120, 250 and 500 nM) were added just before the reaction initiation. The reaction was initiated in the presence of 5 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2 and a 30-fold excess annealing trap and it was quenched with 150 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 6% glycerol, 0.6 % SDS, 200 nM T50 and 50 nM Tel11 at increasing time points. All concentrations listed are final i.e., after initiation of the reaction, unless otherwise stated. The substrate and ssDNA product in each reaction were resolved by 20% native PAGE. The gels were exposed to a phosphor screen, imaged using a Typhoon Trio phosphorimager (GE Healthcare). The results were quantified using ImageQuant software and the data were fit to a single exponential to determine the observed rate constants.

Stopped-flow assay for helicase-mediated removal of protein roadblocks.

In order to measure protein dissociation from G4 substrates, Cy3-G4 DNA (25 nM) was pre-incubated with Cy5-Sub1 (50 nM) in reaction buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 10 mM MgCl2. Pif1 (200 nM) was added to this reaction mixture. The dissociation reaction was initiated by rapid mixing with 5 mM ATP and 10 mM MgCl2 in an SX.18MV stopped flow reaction analyzer (Applied Photophysics). All concentrations listed are final unless otherwise stated. The mixture was excited at 550 nm, and the change in fluorescence was measured using a 665-nm cut-on filter (Newport Corp., catalog number 51330). Data were fit to a single exponential equation to obtain the observed rate constant.

Simultaneous measurement of helicase-mediated protein dissociation and G4 unfolding was carried out by pre-incubating Cy3Cy5-G4 DNA with unlabeled wtSub1. The experiment was performed in the presence of Pif1 (200 nM), ATP (5 mM) and MgCl2 (10 mM) under reaction and instrumentation conditions essentially similar to the stopped-flow assay described above for protein dissociation. The observed rate constant was obtained by fitting the data to a single exponential equation.

Results

Pif1 helicase binds to transcription co-activator Sub1.

Studies have shown that Pif1 localizes to quadruplex sequences in vivo34 and has the ability to unwind tetramolecular23,24 and intramolecular G4 structures35 in vitro. Pif1 exhibits a tight binding and slow unfolding of an intramolecular parallel quadruplex derived from the c-myc promoter sequence36,37. Sub1 protein binds to G4 structures with a KD value in the low nanomolar range22. “In addition, evidence has been provided that Pif1 and Sub1 proteins may interact with one another although the strength of this protein-protein interaction has not been examined38. Taken together, these findings involving the preference of Sub1 and Pif1 for G4 structures triggered the question of whether the Pif1 helicase or translocase activity could disrupt Sub1 interaction with G4 DNA.

To assess the interaction between Sub1 and Pif1, a fluorescently-labeled form of Sub1 was created. Sub1 is a small protein (~33 kDa) that consists of only 292 amino acid residues with no cysteine residues. Therefore, a cysteine residue was added to the C-terminal end of the protein via site-directed mutagenesis. The Sub1-Cys variant protein was subsequently labeled with Cy5-maleimide dye. Molar concentrations of dye and protein were calculated, and the ratio of these values provided the average number of dye molecules coupled per protein molecule. Labelling efficiency calculated using Equation 1 indicated one molecule of Cy5 dye per Cy5-Sub1 protein. The ability of Cy5-Sub1 to bind to G4 DNA was determined by using a dot blot assay (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pif1 and Sub1 interact. (A) Measurement of the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for Sub1 interaction with G4DNA. G4DNA, 1 nM, 5′−32P labeled, was titrated with the wild type or Cy5-Sub1 protein. Samples were loaded onto a dot-blot apparatus then pulled through nitrocellulose and nylon membranes. Protein binds to the nitrocellulose membrane. (B) The fraction of G4DNA bound was plotted against the enzyme concentration using KaleidaGraph software and the data were fit to the quadratic equation. The KD values for Sub1 and Cy5-Sub1 are 0.86 ± 0.18 and 2.9 ± 1.3 nM, respectively. The errors indicate the standard deviation of three independent experiments. (C) Cy5-labeled Sub1 (50 nM) was titrated with Pif1 and the corresponding changes in fluorescence anisotropy were measured. The anisotropy values were plotted against enzyme concentration using KaleidaGraph software. The data were fit to the quadratic equation and the resulting KD value for Pif1-Sub1 interaction is 53 ± 2 nM. The error indicates the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Radiolabeled G4 DNA was incubated with Cy5-Sub1 or with Sub1. The fraction of G4 DNA bound to protein was determined. Cy5-Sub1 exhibited tight binding to G4 DNA (blue squares in Figure 1B) with a similar affinity to Sub1 binding to the same G4 DNA (red circles in Figure 1B).

The interaction between Pif1 and Sub1 was determined by measuring the change in fluorescence anisotropy upon titration of Cy5-Sub1 with Pif1 (Figure 1C). This indicated a direct physical interaction between the two proteins. The changes in the anisotropy values were not as large as normally observed in a protein–DNA binding experiment. This is expected for protein–protein interactions due to the greater molecular mass of labeled Sub1 compared to labeled oligonucleotides. The resulting KD value (53 ± 2 nM) from the binding assay indicates there is a tight interaction between Pif1 and Cy5-Sub1. This finding is also consistent with the qualitative Pif1-Sub1 affinity isolation results shown previously38.

Pif1 helicase catalyzes disruption of Sub1-stabilized G-quadruplex structures.

G4 DNA is known to serve as a structural barrier to the yeast replication pathway and its adverse cellular effects have been proposed to be countered by Pif123,24. Proteins capable of binding to DNA secondary structures (e.g., Sub1) may stabilize these structures, thereby presenting an additional block to helicase-catalyzed G4 unfolding. Alternatively, these G4-binding proteins may serve as a mediator for recruiting helicases at quadruplex regions through protein-protein interactions. It is possible that the two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. In order for Pif1 helicase to unfold G4 DNA, it must first remove proteins interacting with these secondary structures. Pif1 helicase has previously been reported to exert force and disrupt streptavidin-biotin blocks, which suggests that it exhibits protein displacement activity39.

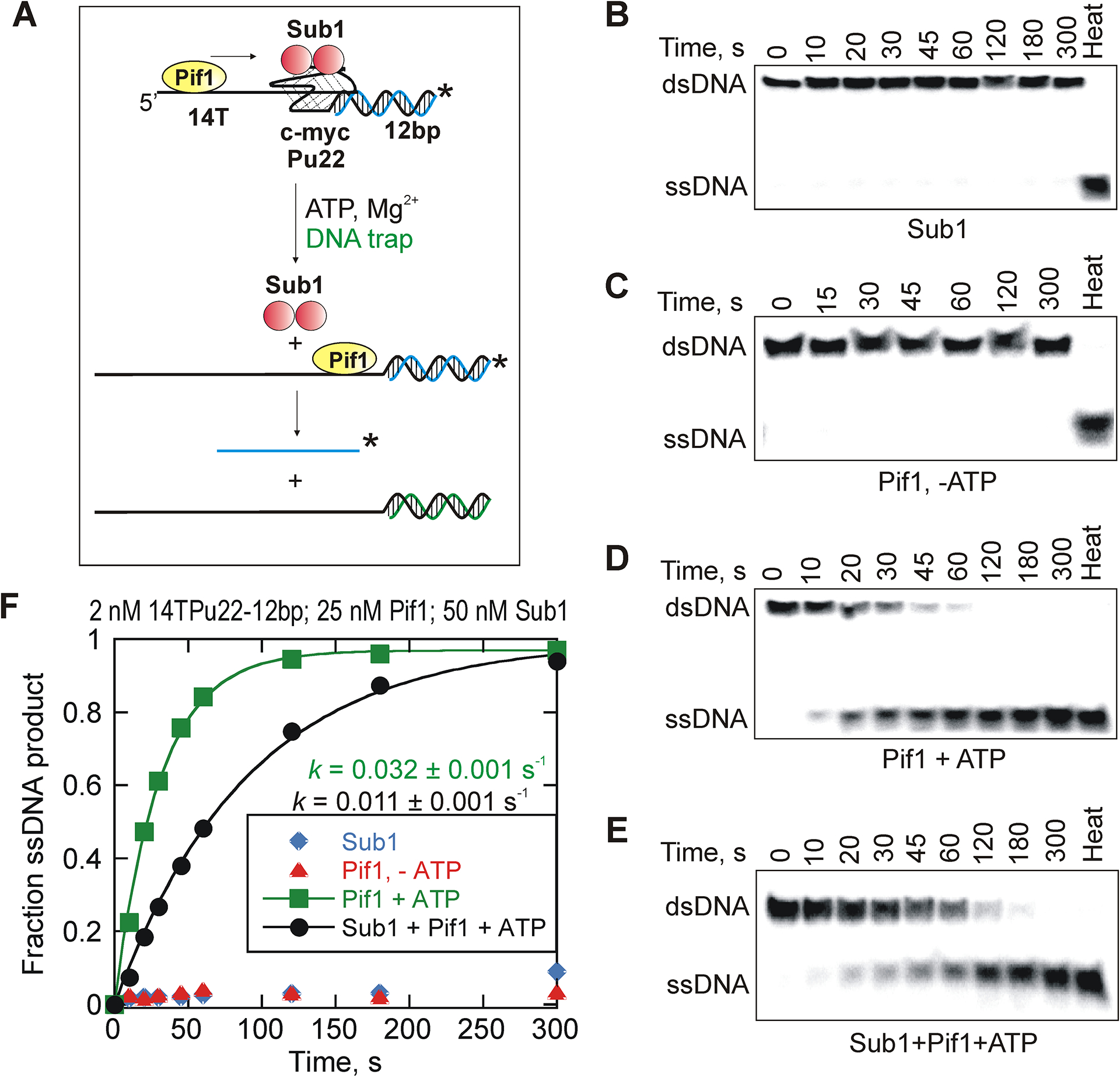

The protein displacement reactions were tested by using a ‘G4 DNA reporter substrate’ (Figure 2A). This assay allowed helicase-mediated protein dissociation and G4 unfolding to be analyzed simultaneously by monitoring the unwinding of a short duplex past the quadruplex.

Figure 2.

Pif1-catalyzed disruption of G4 quadruplex-bound Sub1. (A) A schematic representation of Sub1 dissociating due to Pif1action and subsequent unfolding of the quadruplex structure causing removal of the barrier leading to unwinding of the reporter duplex. Representative gel images for unwinding of 2 nM G4 DNA reporter in the absence of Pif1 (B), in the presence of 25 nM Pif1 but absence of ATP (C), in the presence of 25 nM Pif1 and saturating concentrations of ATP (D), and in the presence of Pif1 (25 nM), ATP and protein barrier Sub1 (50 nM) (E). (F) The results were quantified and the plot shows reaction progress curves for Pif1-catalyzed unwinding of G4 DNA reporter under each specific condition. Data were fit to a single-exponential equation. The observed rate constants for Pif1-mediated G4 unfolding in the absence and presence of Sub1 are 0.032 ± 0.001 s−1 and 0.0109 ± 0.0011 s−1, respectively. The errors indicate the standard error of the fit.

This reporter substrate consists of a 14 nt long single-stranded overhang on the 5′-end that serves as Pif1 loading site followed by a 22 nt purine-rich G-quadruplex fold. On the 3′-end of the substrate, adjacent to the G4 fold, a 12 bp duplex region is present which serves as the reporter. Pif1-catalyzed unwinding of the reporter strand indirectly reports the ability of the helicase to cause Sub1 dissociation and unwind a G4 structure that is present upstream of the reporter duplex, hence termed ‘reporter assay’.

The reporter substrate was initially incubated with Sub1 prior to adding Pif1 in the reaction. The 5′ overhang/loading site (14 nt) of the reporter substrate was designed to accommodate two Pif1 molecules. Pif1 was tested to determine whether it can disrupt Sub1-bound quadruplex structures using its helicase activity.

Single-turnover conditions resulted in no product formation. The substrate is too stable to observe any product under single-turnover conditions (not shown).

The reactions were carried out under multiple turnover conditions in which Pif1 molecules can rebind the substrate multiple times before the reaction is quenched. The unwinding of the reporter duplex was measured under each condition in these dissociation assays. Product formation was not observed in the absence of Pif1, indicating that Sub1 binding alone does not cause reporter melting under the concentrations used here (Figure 2B). We have previously shown that Sub1 binding does not cause G4 unfolding22. Additionally, Pif1 did not catalyze the reaction in the absence of ATP (Figure 2C). Pif1-catalyzed melting of the reporter occurred more slowly in the presence of Sub1 (Figures 2D and 2E). The observed rates for Pif1-driven reactions with and without Sub1 are 0.0109 ± 0.0005 s−1 and 0.032 ± 0.001 s−1, respectively (Figure 2F). The results showed a 2-fold decrease in the rate of product formation in the presence of Sub1 protein, which suggests that Pif1-catalyzed melting of G4 structures bound by protein barriers, is slow and requires multiple catalytic events. However, Pif1 is capable of enhancing Sub1 dissociation from its binding site eventually in order to gain access to G4 DNA.

The mechanism of the dissociation reactions was investigated by stopped-flow using Cy3-labeled tailed quadruplex substrate and Cy5-labeled Sub1 protein. The substrate consisted of a 14 nt Pif1 binding site and 22 nt G-rich region with a potential to form G4 structure for Sub1 interaction. Cy5-Sub1 was pre-incubated with Cy3-G4 substrate and FRET was monitored as Sub1 was released from G4 DNA in the presence of Pif1 (Figure 3A). No change in FRET was observed in the absence of ATP (Figure 3B). However, a decrease in FRET was observed in the presence of ATP, indicating that Pif1 may push Sub1 off the G4 substrate using the energy obtained from ATP hydrolysis (Figure 3C). However, another mechanism is that Pif1 might partially unfold the G4, reducing the affinity of Sub1 for the DNA. In both mechanisms, Sub1 dissociation from the DNA is enhanced due to the activity of Pif1.

Figure 3.

Pif1-mediated disruption of Sub1-G4DNA complex. (A) Schematic of Pif1-catalyzed dissociation of Sub1 from a tailed G4 DNA. Pif1 (200 nM) was added to a mixture of 25 nM Cy3-G4DNA and 50 nM Cy5-Sub1 and the reaction was carried out in the (B) absence or (C) presence of 5 mM ATP. The reaction was monitored by measuring changes in FRET. Data were fit to single exponential to obtain the observed rate constant (k = 0.069 ± 0.005 s−1). (D) Shown is a diagrammatic representation of Pif1-mediated Sub1 dissociation from quadruplex region and subsequent processing of the G4 structure. Unfolding of 25 nM Cy3Cy5-G4DNA bound by unlabeled Sub1 (50 nM) was performed with 200 nM Pif1.The reaction was carried out in the (E) absence or (F) presence of 10 mM ATP and the changes in fluorescence were monitored. Fitting the data to a single exponential revealed the observed rate constant (k = 0.016 ± 0.0007 s−1). The errors in each case represent the standard error of the fit. No protein dissociation and/or G4 unfolding was observed in the absence of ATP.

The observed rate for protein dissociation is 0.069 ± 0.005 s−1. In order to investigate whether Pif1 also unfolds the quadruplex region of the substrate after dissociation of Sub1 from its binding site, we carried out another stopped–flow assay with a dual-fluorophore labeled substrate and an unlabeled Sub1 protein. Sub1 was pre-incubated with a 3′Cy3-5′Cy5 tailed G4 DNA substrate and FRET was monitored in the presence of Pif1 and ATP (Figure 3D). In this case, a decrease in fluorescence will be observed only when the G4-DNA structure sequestered by Sub1 is disrupted. We did not observe a fluorescence change in the absence of ATP (Figure 3E). Pif1 helicase, however, in the presence of ATP unfolded the quadruplex region of the substrate bound by Sub1 at a rate of 0.016 ± 0.0007 s−1, as evident from the decrease in FRET (Figure 3F). The slower rate compared to dissociation of Sub1 (Figure 3C) indicates that unfolding of G4 occurs after dissociation of Sub1. These results demonstrated that Pif1 processes both structural as well as protein barriers from DNA.

Yeast Cdc13 exhibits a high-affinity interaction with 11mer telomere sequence.

Pif1 helicase facilitates replication of the yeast telomere sequence past a telomeric protein barrier29,30. Depletion of Pif1 helicase in yeast cells caused increased stalling at a telomere sequence bound protein. The Galletto lab found that Pif1 could remove Rap1 from telomeric DNA, thereby allowing DNA synthesis by Pol δ5. Cdc13 is part of a protein complex that includes Stn1 and Ten1 proteins which together, protects telomere ends40. Cdc13 alone can bind tightly to telomeric ssDNA consisting of a minimum 11 nucleotides which is required for high affinity binding41. For the current study, Cdc13 binding to a specific ssDNA sequence posed an excellent substrate to study disruption of protein-DNA interactions.

In order to determine the binding affinity and test the reported specificity of Cdc13, an 11mer ssDNA (Tel11) derived from the yeast telomere sequence was designed (Figure 4A). For the purposes of comparison, an oligonucleotide of a similar length with a mixed sequence composition was also designed (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Yeast telomere capping protein, Cdc13, shows high affinity binding to a 11mer telomeric sequence. (A) Shown are the sequences of the oligonucleotides used in the gel shift assay. Additional circular dichroism spectra of 10 μM 11mer telomeric ssDNA (GTGTGGGTGTG) in the presence or absence of 100 mM KCl provides no evidence of inter-molecular quadruplex formation. (B) SDS-PAGE gel image of the purified recombinant full-length protein Cdc13. Representative EMSA gel images for Cdc13 bound to (C) yeast telomere sequence or (D) the mixed sequence oligonucleotide. (E) The gel bands were quantified and the fraction of DNA bound was plotted against Cdc13 concentration using KaleidaGraph software. The data were fit to the Hill equation and the apparent dissociation constant values (K0.5) for the oligonucleotides with telomeric sequence (pink circles) and mixed sequence (blue squares) were 15.3 ± 0.9 nM and 124.2 ± 8.8 nM, respectively. The Hill coefficients for Tel11 and mixed sequence DNA are 1.44 ± 0.14 and 2.86 ± 0.71, respectively. The errors indicate the standard deviation of three independent experiments. (F) Data in panel (E) expanded to illustrate the initial phase in protein-DNA complex formation.

The 11mer telomeric sequence was rich in guanine, therefore, prior to performing binding assays, possible formation of inter-molecular G-quadruplex structures in the presence of KCl was explored. The circular dichroism spectrum of this DNA sequence (10 μM) was obtained in the presence and absence of KCl (Figure 4A). However, the CD spectra did not show any peak corresponding to G4 formation, indicating that Tel11 does not form a quadruplex structure at the concentrations used here.

Yeast telomere-binding protein Cdc13 was over-expressed and purified (Figure 4B) from E.coli as described in materials and methods. Gel shift assays were performed to characterize the high-affinity interaction between Cdc13 and the telomere sequence. As the concentration of Cdc13 was increased in the reaction mixture, the formation of protein-DNA complex was clearly visualized on the gel for both substrates; Tel11 as well as the oligo with mixed sequence composition (Figures 4C and 4D). The bands were quantitated, and the fraction of substrate bound was plotted against Cdc13 concentration (Figure 4E). The apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (K0.5) values for the telomere sequence and that of the mixed sequence were determined to be 15.3 ± 0.9 nM and 124.2 ± 8.8 nM, respectively. These results indicate that Cdc13 binds to the telomere sequence approximately 8–10 fold tighter compared to ssDNA with mixed sequence composition. These results are consistent with previously reported findings about the specificity of Cdc13 for yeast telomere sequence41. Another point to be noted here is that Cdc13 exhibits cooperative binding behavior, which is more apparent in case of the mixed sequence oligo compared to the binding curve for the telomeric DNA (Figure 4F). However, previous studies have indicated that Cdc13 shows cooperativity for binding telomeric substrates41 and it is possible that due to the tight interaction between Cdc13 and Tel11, a sigmoidal curve was not detected in the current study.

Pif1 uses its translocase activity to enhance the dissociation of Cdc13 from its binding site.

We designed new reporter substrates that consisted of a 16 bp duplex region with a 5′-single-stranded overhang comprising Tel11 and a Pif1 binding site, such that Tel11 lies in between the duplex and the Pif1 loading site as shown in Figure 5A. Therefore, Cdc13 would form a barrier to Pif1 between the ssDNA binding site and the reporter duplex. The kinetics of Cdc13 dissociation was measured under multiple turnover conditions, in which Pif1 molecules can rebind the substrate multiple times if they dissociate. This assay measures the appearance of the radiolabeled reporter strand that is generated by the unwinding of the duplex past the Cdc13 barrier. Previous kinetic studies indicate that a 16 bp duplex is unwound in less than one second by Pif139; therefore, DNA unwinding is very rapid compared to protein dissociation.

Figure 5.

Pif1-enhanced dissociation of Cdc13 from telomeric sites. (A) The cartoon represents Pif1 enhanced dissociation of Cdc13 from its DNA binding site leading to unwinding of the reporter duplex past the protein barrier. (B) Representative gel images indicating helicase-catalyzed unwinding of the reporter duplex with or without the Cdc13 block. No protein dissociation or duplex unwinding was observed in the absence of ATP. (C – F) Substrates (1 nM) with varying length overhangs (8T, 15T or 30T), a Cdc13 binding site and a 16 bp reporter duplex were tested for Pif1 enhanced protein dissociation. The Cdc13 binding site was saturated with 60 nM Cdc13. The protein dissociation reactions for each DNA substrate were performed in the presence of increasing Pif1 concentrations (30 nM, 60 nM, 120 nM, and 240 nM) and unwinding of the reporter duplex in each case was measured. Shown are the reaction progress curves for (C) 8T overhang, (D) 15T overhang, and (E) 30T overhang. The data were fit to a single exponential equation to obtain the rate constants. (F) Shown is a re-plot of the observed rate constants for helicase-enhanced Cdc13 dissociation/duplex unwinding from C-E as a function of Pif1 concentration. The data were fit to a linear equation.

The results show that the Cdc13 barrier was removed by Pif1 only in the presence of ATP (Figure 5B). The length of the Pif1 loading site on the reporter substrate was increased from 8 nt to 15 nt and 30 nt. Cdc13 dissociation from each substrate was performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of Pif1. The fraction product was plotted as a function of time in each case (Figures 5C, D and E) and the results indicated that the observed rate constants for Cdc13 dissociation increased modestly with increasing Pif1 concentration (Figure 5F). An approximately 4-fold increase in the rate of Cdc13 dissociation was observed as the binding site for Pif1 helicase was increased from 8 to 30 nucleotides (Figure 5F).

This result supports the conclusion that multiple Pif1 molecules can work together to enhance protein dissociation which is in agreement with previous results for Pif1-catalyzed removal of streptavidin from varying lengths of biotinylated DNA39. This activity has been described as “functional cooperativity” and is explained in part by the ability of the trailing enzyme molecules to move forward and push the lead molecules to facilitate protein dissociation42,43.

Varying the affinity of Cdc13 for ssDNA by altering the sequence of the DNA; impact on Pif1-enhanced protein dissociation.

When a helicase collides with a DNA-bound protein, protein-DNA interactions can be disrupted by force imparted through protein-protein interactions. The protein-DNA bonds can be broken in a “stepwise” manner or it is possible that strain builds up and the DNA-bound protein is dislodged from the DNA in one major step (i.e., a “spring-loaded” mechanism) (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

A base substitution within the 11mer telomere sequence affects Cdc13 binding affinity. (A) Schematic representation of the two models proposed for helicase-enhanced dissociation of protein roadblocks during helicase translocation on ssDNA. The “stepwise” dissociation model indicates the removal of protein-DNA contacts incrementally by breaking the points of interaction in discrete steps. On the other hand, the “spring-loaded” mechanism indicates complete dissociation of the protein block in one kinetic event after buildup of strain. (B) Shown is a schematic representation of the 5′- and 3′-mutations introduced in the Cdc13-binding site of the reporter substrate. Guanine at position 1 was replaced with cytosine to create 5′-end mutation in Tel11, whereas base substitution at positions 7 and 9 created a 3′-end mutation in the 11mer telomeric sequence. Representative EMSA gel images for Cdc13 bound to (C) Tel11 with substitution at position 1 or (D) Tel11 with substitution at positions 7 & 9, indicate a shift in the mobility of species as the protein-DNA complex forms. (E) The gels were quantified and the fraction of DNA bound is plotted against Cdc13 concentration using KaleidaGraph software. For the purposes of comparison, the binding data for the canonical telomere sequence Tel11 (red circles) has been included in this plot along with the binding data sets for Tel11 with 5′-end mutation (purple triangles) and 3′-end mutation (green inverted triangles). The data were fit to the Hill equation and the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant values (K0.5) for Tel11, Tel11 (G1C) 5′ mutant and Tel11 (G7C/G9C) 3′ mutant are 15 ± 1 nM, 150 ± 15 nM and 97 ± 3 nM, respectively. The Hill coefficients for Tel11, Tel11 (G1C) 5′-mutant and Tel11 (G7C/G9C) 3′-mutant are 1.4 ± 0.2, 2.1 ± 0.3 and 4.5 ± 0.3, respectively. The errors indicate the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

The solution structure of the Cdc13-DNA binding domain (DBD) in complex with telomeric ssDNA provides interactions that lead to sequence selective binding44. Cdc13-DBD specifically recognizes a GxGT motif in the 5′ end of the telomeric ssDNA, conferring the ability to recognize the degenerate S. cerevisiae telomere sequence45. Although a 11mer of the telomeric GT-rich sequence is required for full binding activity, only three of these 11 bases are recognized with high specificity (G1, G3 and T4). The bases at the 3′ end of Tel11 are not individually required for binding specificity but are important for maintaining affinity45.

In order to explore the mechanism for protein dissociation, rates of Pif1-enhanced protein dissociation from the altered sequences were determined. We selected two positions/mutations from the degenerate sequence, one on the 5′ end and the other at the 3′ end. For the 5′-end mutation, we replaced guanine at position 1 with cytosine (G1C). This base has been reported to be one of the critical bases contributing to the binding specificity between Cdc13 and Tel1145. However, studies indicate that there are no bases at the 3′ end of Tel11 that may cause a similar impact in binding affinity upon mutation as guanine at position 1. Therefore, our strategy was to replace two bases at a time at the 3′ end of Tel11 and create a double mutation. Guanines at positions 7 and 9 were replaced with cytosines (G7C/G9C). A diagram of the specific location of each base substitution is indicated in Figure 6B.

Base substitution within the telomere sequence and its effects on Cdc13 binding affinity.

Prior to performing the dissociation reactions, the binding affinity of Cdc13 for the altered telomeric DNA substrates was measured using a gel shift assay. Tel11 and its altered counterparts were radiolabeled at 5′ end and each of them was titrated individually with Cdc13. Subsequently, the protein-DNA complex and free DNA were resolved on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel (Figures 6C and D). The bands were quantified and the fraction of substrate bound was plotted against Cdc13 concentration (Figure 6E). Data was fit to the Hill equation. The resulting apparent dissociation constant (K0.5) values for Tel11 (G1C) 5′-mutation and Tel11 (G7C/G9C) 3′-double mutation were 149.5 ± 14.7 nM and 96.7 ± 3.0 nM, respectively. The binding curve for the canonical Tel11 has also been included in the same plot (Figure 6E) for the purpose of comparison with the altered substrates.

Cooperativity in protein binding to the altered T11 sequences was evident from the sigmoidal curves. These results indicate formation of a protein oligomer. Lewis et al. have reported previously that Cdc13 in solution exhibits dimer formation and that the N-terminal domain of the full-length protein mediates its homodimerization41. Cdc13 appears capable of oligomerization in the absence of Stn1 and Ten1. However, recent structural data favors formation of a heterodimer within the context of the CST complex40.

Pif1-mediated dissociation of Cdc13 from the mutated Tel11 (G1C or G7C/G9C).

The altered 11mer ssDNA sequences were introduced into the partial duplex reporter substrates. The reporter DNA substrates consisted of a 16 bp duplex region with a 5′-single-stranded overhang comprising Tel11 (with 5′ or 3′ base substitutions) and a Pif1 loading site, as shown in Figure 7A. The kinetics of Cdc13 dissociation from the altered telomeric sites was investigated under multiple turnover conditions (Figure 7B). The fraction product in each case was plotted as a function of time (Figure 7C). The rates obtained for Cdc13 dissociation from substrates consisting of 5′ and 3′ mutations are 0.008 ± 0.0002 s−1 and 0.014 ± 0.004 s−1, respectively. The results indicate that the presence of base substitutions in Tel11 and the corresponding reduction in Cdc13 binding affinity led to an increase in the protein dissociation rates by 2–3 fold, when compared with the original telomere sequence (Figure 7C). Cdc13 dissociated more rapidly from the substrate that was bound more tightly, 3′-mTel. If a spring-loaded mechanism was operating, then we would expect Cdc13 to dissociate more rapidly from the weaker binding sequence. The observed rate of protein dissociation was relatively faster with the substrate that harbored a 3′-end (G7C/G9C) mutation and bound more tightly. Therefore, these results are supportive of the ‘stepwise dissociation’ model, whereby the protein-DNA contacts are broken by the helicase incrementally with the critical points of interaction being located at the 3′-end of the substrate (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Pif1-mediated dissociation of Cdc13 from the mutated Tel11 (G1C or G7C/G9C). (A) Pif1 translocates unidirectionally (5′ to 3′) on ssDNA in order to remove protein roadblocks and unwind DNA duplex. Cdc13 bound to mutant Tel11 is displaced by Pif1 leading to unwinding of the reporter duplex past the barrier. (B) Representative gel images show unwinding of the reporter strand that indirectly reports Pif1-catalyzed dissociation of Cdc13 in the presence of ATP from the canonical as well as the mutated telomeric sites. 1 nM reporter substrate (15Ttel11–16bp) with the appropriate mutation was pre-incubated with 250 nM Cdc13. The helicase-catalyzed protein dissociation reactions were carried out in the presence of 250 nM Pif1. (C) Shown are the reaction progress curves for 15Ttel11–16bp substrate with or without mutations. The data were fit to a single exponential equation to obtain the respective rate constants. The observed rate constants for Cdc13 dissociation from canonical Tel11 (red circles), Tel11 harboring 5′ mutation (purple triangles) and Tel11 consisting of 3′ mutation (green diamonds) are 0.005 ± 0.001 s−1, 0.008 ± 0.001 s−1 and 0.014 ± 0.004 s−1, respectively. The errors indicate the standard deviation of three independent experiments. (D) Schematic representation of the “stepwise” dissociation model for Pif1-catalyzed disruption of Cdc13-telomeric DNA complex.

Discussion

Helicase-catalyzed dissociation of nucleoprotein blocks from possible biological substrates are indicated in Figure 8. The biological requirement for helicase catalyzed removal or bypass of proteins on DNA has been recognized for decades46,47. Proteins bound to template DNA may serve to stall replication or transcription, which may interfere with the accurate duplication of the genetic material or expression of specific genes.

Figure 8.

Model for Pif1-mediated disruption of protein-DNA complexes and its relevance in various cellular activities. Shown are the biological substrates from which the occurrence of Pif1-catalyzed protein dissociation may promote genome stability. The recruitment of Pif1 to G4 sites through specific interactions with G4-binder Sub1 can play a role in destabilization or processing of Sub1-bound quadruplex structures. Pif1-mediated removal of Cdc13 from the telomere sequence may play an important role in the clearance of protein blocks from DNA ends.

Removal of these barriers is a prerequisite for faithful progression of various cellular pathways. Numerous helicases are now being recognized to couple ATP hydrolysis to aid in the clearance of protein blocks to prevent specific cellular processes from collapsing48,49.

The removal of proteins from nucleic acids by helicases can have numerous biological implications within the cellular context (Figure 8). For example, the removal of yeast telomere capping protein Cdc13 from the telomeric DNA sequence by Pif1 may facilitate in overcoming replication blocks at these regions. On the other hand, the interaction of yeast transcription co-activator Sub1 with G4 structures present in the promoter regions may play an important role in transcription regulation. Pif1 regulates telomere length negatively by dislodging telomerase bound to DNA ends9,10,12. Previously, the protein displacement activity of Pif1 has successfully been studied using streptavidin-biotinylated DNA complexes as model nucleoprotein obstacles39. The Galletto lab examined Pif1 protein displacement of Rap1 molecules bound to telomeric DNA. Pif1 was able to remove single Rap1 molecules as well as an array of Rap1 molecules5. The activity of Pif1 allowed Pol δ to carry out DNA synthesis past the Rap1 block. Other studies indicated that Pif1 was primarily needed for replication through G4 structures in the lagging strand50. Here, we extend these protein dissociation experiments by examining protein barriers formed by Sub1 when bound to G4 DNA and Cdc13, when bound to single-stranded telomeric DNA. These blocks can form in S. cerevisiae but have not been explored for inhibition of Pif1.

G4 DNA binding proteins, such as Sub1, may provide additional stability to these structural barriers that must be removed by Pif1 for the helicase to process G4 DNA in vivo. Using a DNA unwinding reporter assay and fluorescence-based experiments, we demonstrated that Pif1 can displace Sub1 from an intramolecular G4 DNA. However, the rate is slower than with G4 DNA alone, indicating that Sub1 does impart additional stability (Figures 2 and 3). Another report indicated that the human helicase FANCJ dislodges the shelterin proteins TRF1 and TRF2 from the telomeric duplex DNA in an RPA-stimulated manner15. Whether RPA would stimulate Pif1-disruption of Sub1-bound G4 DNA remains to be determined. Pif1 helicase has previously been reported to interact specifically with the mitochondrial SSB Rim1, and this interaction enhances the ability of this helicase to unwind duplex DNA33. Unlike Rim1 and unwinding of dsDNA, Sub1 stabilizes G4DNA leading to Pif1 disruption at slower rates. From the results of the current study, it is possible that Sub1 acts as a mediator protein that enables the recruitment of Pif1 helicase to G4 DNA. Pif1 helicase, subsequently, dislodges Sub1 from its G4 DNA site in order to gain access to the DNA secondary structure to be processed.

Considerable evidence suggests that accessory replicative helicases also facilitate disruption of nucleoprotein complexes ahead of the replication fork within the context of the replisome48,51. This allows resumption of blocked forks and prevention of replisome inactivation. For example, E. coli Rep helicase aids progression of a replisome through nucleoprotein complexes in vitro52. Similarly, a homologous E. coli helicase, UvrD, also causes progression of the replication fork through protein-DNA complexes53. These helicases provide a potential means to increase the rate of dissociation of protein-DNA replicative barriers29.

Different accessory helicases appear to overcome replication blocks at different DNA sites. Pif1 helicase overcomes replication blocks arising due to protein barriers at telomeric regions30. Depletion of Pif1 in yeast cells results in an increased stalling of the replication fork at a telomeric protein barrier29,41. It is possible that Cdc13 may pose a block to a moving replication fork near the ends of telomeres. Here we have shown that Pif1 utilizes the energy from ATP hydrolysis to enhance dissociation of Cdc13 from its binding site. The simplest explanation for this reaction is that Pif1 translocates on ssDNA, collides with Cdc13, and then displaces it presumably by exerting force. There is no duplex or G-quadruplex DNA to distort, only ssDNA. Rap1 binds to the duplex region of telomeres and slows DNA replication movement54. Pif1 can displace Rap1 from telomeres5. After displacing Rap1 in duplex telomeric DNA, Pif1 may continue along the telomere to encounter and displace Cdc13, which binds the single-stranded 3’-end of the telomere.

Cdc13 displacement activity was enhanced when multiple Pif1 molecules were aligned on the substrate (helicase trains) indicating that helicase molecules can work together to dislodge proteins effectively (Figure 5F). Pif1 was shown to bypass an inactive Cas9 R-loop barrier in a concentration dependent manner55. The concentration dependence could be due to distributive activity of Pif1, but the sigmoidal dependence of Pif1’s ability to displace streptavidin from biotinylated oligonucleotides is best explained by Pif1 producing force on proteins blocking its path. The trailing helicase molecules can push the lead molecule to move forward in order to push protein from the DNA by force through steric interactions.

A recent study concluded that Pif1 was incapable of removing Cdc13 from a DNA-Cdc13 complex in which DNA was shortened by the bound Cdc1356. It is possible that only one or two molecules of Pif1 were able to bind to the substrate used by Lin et al. If multiple Pif1 molecules must work together to dislodge Cdc13 then Pif1 might not be capable of dislodging Cdc13 from the particular substrate in Lin et al. It is not clear whether multiple helicase molecules form “trains” in vivo. Similar results were previously observed with T4 Dda helicase42 which belongs to the same family as Pif1. It was reported that monomers of Dda can unwind duplex DNA, however, multiple Dda molecules are needed to efficiently disrupt protein-DNA interactions57.

The results from the mutational analysis have been interpreted as a ‘stepwise dissociation’ model, which relies on the findings that the observed rate for protein displacement was faster for the tighter binding sequence (Figure 7C/D). More evidence is needed from sources such as single-molecule FRET to test this mechanism. Pif1 has previously been reported to exhibit 1 bp stepping mechanism for unwinding DNA duplex that is powered by the hydrolysis of 1 ATP molecule per base pair unwound39. Due to the large number of interactions for proteins bound to DNA, the activation barrier for disrupting a protein-DNA complex is higher than separating a single base pair within two strands of a duplex. Therefore, Pif1 disrupts bonds that stabilize a nucleoprotein complex by hydrolyzing multiple ATP molecules per protein-DNA bond.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Matthew Bell for technical assistance with the purification of the variant Sub1. Additionally, we acknowledge Dr. Amit Ketkar for his assistance with Cdc13 purification steps.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant [R01 GM098922, R01 GM117439, and R35 GM122601 to K.D.R.], the UAMS Research Council, and the UAMS Vice Chancellor for Research. UAMS Proteomics Core is partially supported by the Arkansas IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence, National Institutes of Health Grant P20 GM103429 (L. Cornett). The UAMS DNA Sequencing Core is supported by the UAMS Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Inflammatory Response (National Institutes of Health Grant P20 GM103625), and the UAMS Translational Research Institute (National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR000039).

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- (1).Brosh RM, and Matson SW (2020, March 1) History of DNA helicases. Genes (Basel). MDPI; AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gao Y, and Yang W (2020, April 1) Different mechanisms for translocation by monomeric and hexameric helicases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Brüning JG, Howard JAL, Myka KK, Dillingham MS, and McGlynn P (2018) The 2B subdomain of Rep helicase links translocation along DNA with protein displacement. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 8917–8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hawkins M, Dimude JU, Howard JAL, Smith AJ, Dillingham MS, Savery NJ, Rudolph CJ, and McGlynn P (2019) Direct removal of RNA polymerase barriers to replication by accessory replicative helicases. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 5100–5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Koc KN, Singh SP, Stodola JL, Burgers PM, and Galletto R (2016) Pif1 removes a Rap1-dependent barrier to the strand displacement activity of DNA polymerase δ. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 3811–3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Sokoloski JE, Kozlov AG, Galletto R, and Lohman TM (2016) Chemo-mechanical pushing of proteins along single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 6194–6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Jankowsky E, Gross CH, Shuman S, and Pyle AM (2001) Active disruption of an RNA-protein interaction by a DExH/D RNA helicase. Science 291, 121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).McGlynn P, Savery NJ, and Dillingham MS (2012) The conflict between DNA replication and transcription. Mol. Microbiol 85, 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Boulé JB, Vega LR, and Zakian VA (2005) The yeast Pif1p helicase removes telomerase from telomeric DNA. Nat. 2005 4387064 438, 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Li JR, Yu TY, Chien IC, Lu CY, Lin JJ, and Li HW (2014) Pif1 regulates telomere length by preferentially removing telomerase from long telomere ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 8527–8536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Mateyak MK, and Zakian VA (2006) Human PIF helicase is cell cycle regulated and associates with telomerase. Cell Cycle 5, 2796–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhou JQ, Monson EK, Teng SC, Schulz VP, and Zakian VA (2000) Pif1p helicase, a catalytic inhibitor of telomerase in yeast. Science (80-. ). 289, 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ivessa AS, Zhou JQ, Schulz VP, Monson EK, and Zakian VA (2002) Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5’ to 3’ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 16, 1383–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ivessa AS, Lenzmeier BA, Bessler JB, Goudsouzian LK, Schnakenberg SL, and Zakian VA (2003) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol. Cell 12, 1525–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sommers JA, Banerjee T, Hinds T, Wan B, Wold MS, Lei M, and Brosh RM (2014) Novel function of the Fanconi anemia group J or RECQ1 helicase to disrupt protein-DNA complexes in a replication protein A-stimulated manner. J. Biol. Chem 289, 19928–19941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hu Y, Raynard S, Sehorn MG, Lu X, Bussen W, Zheng L, Stark JM, Barnes EL, Chi P, Janscak P, Jasin M, Vogel H, Sung P, and Luo G (2007) RECQL5/Recql5 helicase regulates homologous recombination and suppresses tumor formation via disruption of Rad51 presynaptic filaments. Genes Dev. 21, 3073–3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).García A, Rosonina E, Manley JL, and Calvo O (2010) Sub1 globally regulates RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol 30, 5180–5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sikorski TW, Ficarro SB, Holik J, Kim TS, Rando OJ, Marto JA, and Buratowski S (2011) Sub1 and RPA associate with RNA polymerase II at different stages of transcription. Mol. Cell 44, 397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tavenet A, Suleau A, Dubreuil G, Ferrari R, Ducrot C, Michaut M, Aude JC, Dieci G, Lefebvre O, Conesa C, and Acker J (2009) Genome-wide location analysis reveals a role for Sub1 in RNA polymerase III transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 14265–14270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).García A, Collin A, and Calvo O (2012) Sub1 associates with Spt5 and influences RNA polymerase II transcription elongation rate. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 4297–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rosonina E, Willis IM, and Manley JL (2009) Sub1 functions in osmoregulation and in transcription by both RNA polymerases II and III. Mol. Cell. Biol 29, 2308–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gao J, Zybailov BL, Byrd AK, Griffin WC, Chib S, Mackintosh SG, Tackett AJ, and Raney KD (2015) Yeast transcription co-activator Sub1 and its human homolog PC4 preferentially bind to G-quadruplex DNA. Chem. Commun 51, 7242–7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Paeschke K, Bochman ML, Daniela Garcia P, Cejka P, Friedman KL, Kowalczykowski SC, and Zakian VA (2013) Pif1 family helicases suppress genome instability at G-quadruplex motifs. Nature 497, 458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ribeyre C, Lopes J, Boulé JB, Piazza A, Guédin A, Zakian VA, Mergny JL, and Nicolas A (2009) The yeast Pif1 helicase prevents genomic instability caused by G-quadruplex-forming CEB1 sequences in vivo. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chandra A, Hughes TR, Nugent CI, and Lundblad V (2001) Cdc13 both positively and negatively regulates telomere replication. Genes Dev. 15, 404–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wu ZJ, Liu JC, Man X, Gu X, Li TY, Cai C, He MH, Shao Y, Lu N, Xue X, Qin Z, and Zhou JQ (2020) Cdc13 is predominant over Stn1 and Ten1 in preventing chromosome end fusions. Elife 9, e53144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Grandin N, Reed SI, and Charbonneau M (1997) Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13. Genes Dev. 11, 512–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Pennock E, Buckley K, and Lundblad V (2001) Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell 104, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Anand RP, Shah KA, Niu H, Sung P, Mirkin SM, and Freudenreich CH (2012) Overcoming natural replication barriers: Differential helicase requirements. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1091–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Smith S, Banerjee S, Rilo R, and Myung K (2008) Dynamic regulation of single-stranded telomeres in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178, 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Stewart JA, Wang Y, Ackerson SM, and Schuck PL (2018) Emerging roles of CST in maintaining genome stability and human disease. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed 23, 1564–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Morris PD, Tackett AJ, and Raney KD (2001) Biotin-streptavidin-labeled oligonucleotides as probes of helicase mechanisms. Methods 23, 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ramanagoudr-Bhojappa R, Blair LP, Tackett AJ, and Raney KD (2013) Physical and functional interaction between yeast Pif1 helicase and Rim1 single-stranded DNA binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1029–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Paeschke K, Capra JA, and Zakian VA (2011) DNA Replication through G-Quadruplex Motifs Is Promoted by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pif1 DNA Helicase. Cell 145, 678–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhou R, Zhang J, Bochman ML, Zakian VA, and Ha T (2014) Periodic DNA patrolling underlies diverse functions of Pif1 on R-loops and G-rich DNA. Elife 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Byrd AK, and Raney KD (2015) A parallel quadruplex DNA is bound tightly but unfolded slowly by Pif1 helicase. J. Biol. Chem 290, 6482–6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Byrd AK, Bell MR, and Raney KD (2018) Pif1 helicase unfolding of G-quadruplex DNA is highly dependent on sequence and reaction conditions. J. Biol. Chem 293, 17792–17802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lopez CR, Singh S, Hambarde S, Griffin WC, Gao J, Chib S, Yu Y, Ira G, Raney KD, and Kim N (2017) Yeast Sub1 and human PC4 are G-quadruplex binding proteins that suppress genome instability at co-transcriptionally formed G4 DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 5850–5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ramanagoudr-Bhojappa R, Chib S, Byrd AK, Aarattuthodiyil S, Pandey M, Patel SS, and Raney KD (2013) Yeast Pif1 helicase exhibits a one-base-pair stepping mechanism for unwinding duplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem 288, 16185–16195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ge Y, Wu Z, Chen H, Zhong Q, Shi S, Li G, Wu J, and Lei M (2020) Structural insights into telomere protection and homeostasis regulation by yeast CST complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 27, 752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lewis KA, Pfaff DA, Earley JN, Altschuler SE, and Wuttke DS (2014) The tenacious recognition of yeast telomere sequence by Cdc13 is fully exerted by a single OB-fold domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Byrd AK, and Raney KD (2004) Protein displacement by an assembly of helicase molecules aligned along single-stranded DNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11, 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Levin MK, Wang YH, and Patel SS (2004) The functional interaction of the hepatitis C virus helicase molecules is responsible for unwinding processivity. J. Biol. Chem 279, 26005–26012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Mitton-Fry RM, Anderson EM, Theobald DL, Glustrom LW, and Wuttke DS (2004) Structural basis for telomeric single-stranded DNA recognition by yeast Cdc13. J. Mol. Biol 338, 241–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Eldridge AM, Halsey WA, and Wuttke DS (2006) Identification of the determinants for the specific recognition of single-strand telomeric DNA by Cdc13. Biochemistry 45, 871–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Barry J, and Alberts B (1994) A role for two DNA helicases in the replication of T4 bacteriophage DNA. J. Biol. Chem 269, 33063–33068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Liu B, and Alberts BM (1995) Head-On Collision Between a DNA Replication Apparatus and RNA Polymerase Transcription Complex. Science (80-. ). 267, 1131–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Brüning JG, Howard JL, and McGlynn P (2014) Accessory replicative helicases and the replication of protein-bound DNA. J. Mol. Biol 426, 3917–3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Brüning JG, Howard JAL, and McGlynn P (2016) Use of streptavidin bound to biotinylated DNA structures as model substrates for analysis of nucleoprotein complex disruption by helicases. Methods 108, 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Dahan D, Tsirkas I, Dovrat D, Sparks MA, Singh SP, Galletto R, and Aharoni A (2018) Pif1 is essential for efficient replisome progression through lagging strand G-quadruplex DNA secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 11847–11857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Syeda AH, Wollman AJM, Hargreaves AL, Howard JAL, Bruning JG, McGlynn P, and Leake MC (2019) Single-molecule live cell imaging of Rep reveals the dynamic interplay between an accessory replicative helicase and the replisome. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 6287–6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Guy CP, Atkinson J, Gupta MK, Mahdi AA, Gwynn EJ, Rudolph CJ, Moon PB, van Knippenberg IC, Cadman CJ, Dillingham MS, Lloyd RG, and McGlynn P (2009) Rep provides a second motor at the replisome to promote duplication of protein-bound DNA. Mol. Cell 36, 654–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Gupta MK, Guy CP, Yeeles JTP, Atkinson J, Bell H, Lloyd RG, Marians KJ, and McGlynn P (2013) Protein-DNA complexes are the primary sources of replication fork pausing in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 7252–7257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Makovets S, Herskowitz I, and Blackburn EH (2004) Anatomy and dynamics of DNA replication fork movement in yeast telomeric regions. Mol. Cell. Biol 24, 4019–4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Schauer GD, Spenkelink LM, Lewis JS, Yurieva O, Mueller SH, van Oijen AM, and O’Donnell ME (2020) Replisome bypass of a protein-based R-loop block by Pif1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 117, 30354–30361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Lin Y-Y, Li M-H, Chang Y-C, Fu P-Y, Ohniwa RL, Li H-W, and Lin J-J (2021) Dynamic DNA Shortening by Telomere-Binding Protein Cdc13. J. Am. Chem. Soc 143, 5815–5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Byrd AK, and Raney KD (2006) Displacement of a DNA binding protein by Dda helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 3020–3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]