Abstract

Despite its central importance in gene regulation, chromatin in mammalian cells remains relatively poorly understood—a predicament due to the paucity of robust genetic tools in mammals, the complexity of the chromatin remodeling machinery, and the dynamic properties of chromatin in vivo. Here we review recent developments in understanding endogenous mammalian gene regulation via the use of designed transcription factors (TFs). These include mutated forms of naturally occurring TFs that exhibit dominant-negative activity, and designed proteins with novel, predetermined DNA-binding specificities. Systematic targeting of designed TFs to particular promoters is helping to illuminate the complex rules that chromatin imposes on TF access and action in vivo. We evaluate the potential applications of these proteins as probes of mammalian chromatin-based regulatory pathways and their potential for the therapy of human disease, highlighting leukemia in particular.

Introduction

Once assembled into chromatin inside the nucleus, the human genome acquires the ability to regulate ontogeny. Of the many ‘emergent properties’ gained by DNA following chromatin assembly, the regulatory program embedded in the genome is particularly salient. This program is determined by complex interactions between the DNA, the core and linker histones, nonhistone regulators, and a large number of activities that modify and remodel chromatin structure (Wolffe, 1998). In yeast, programming at the chromatin level has been successfully studied by reverse genetics and various genome-wide analysis methods (Gregory, 2001; Wyrick and Young, 2002), and is well understood in specific cases such as the mating type loci, the PHO genes or the HO endonuclease promoter (Gregory, 2001). With the notable exception of embryonic stem cells, the mammalian genome resists homologous recombination, and thus reverse genetics in human cells is difficult, though feasible (Sedivy, 2002). Understanding the interplay between chromatin and the genome is further hampered by the complications arising from the existence of functionally redundant genes within each family of chromatin regulators, including, for example, the following pairs: CBP and p300, HDAC1 and 2, Brg1 and hBrm, N-CoR and SMRT (Berger, 2001; Fyodorov and Kadonaga, 2001; Khochbin et al., 2001). Consequently, with some exceptions, including the mouse serum albumin gene (Zaret, 1995), the MMTV LTR (Hager, 2001) and the β-interferon enhanceosome (Merika and Thanos, 2001), the relationship between ‘packaging’ and regulation of mammalian genes is not as well understood as it is for the genes of budding yeast.

This predicament may soon be resolved in part due to improvements in technologies that allow in vivo regulation of specific mammalian genes. These include post-transcriptional approaches such as RNA interference (in certain, but not all, cell types; reviewed in Hutvagner and Zamore, 2002), but also techniques that appropriate the cells’ own machinery for transcriptional regulation. It is now feasible to change the expression level of a mammalian gene via the use of a transcription factor (TF) that was designed to do so. Dominant-negative allelic forms of naturally occurring proteins can be used for this purpose and molecules with novel DNA-binding specificities can also be designed. For example, polyamides or peptide-nucleic acids that recognize sequences by engaging the DNA via the major or minor groove can now be synthesized (Braasch and Corey, 2001; Demidov and Frank-Kamenetskii, 2001; Dervan, 2001). Alternatively, a protein domain can be designed to bind to a particular sequence with high specificity (Pavletich and Pabo, 1991); this is convenient from a technical standpoint because the DNA-binding module fused to a functional domain relevant to the specific experimental goal can be encoded by a single chimeric cDNA which the cell transcribes and translates.

This review describes the use of designed TFs to regulate endogenous mammalian genes in vivo, the promise and limitations of this approach in basic science and clinical settings, and what its application has taught us about mammalian chromatin.

The positives of being negative

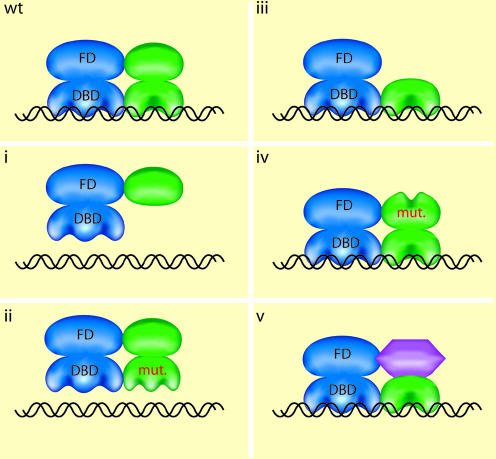

A regulatory pathway can be analyzed by the introduction of proteins that act as repressors of its components (Figure 1). This approach recapitulates regulatory mechanisms used by the cell: for example the basic helix–loop–helix leucine zipper (bHLH-ZIP) protein MAD interacts with MAX and represses the transcription of genes regulated by c-MYC/MAX heterodimers (Grandori et al., 2000), and splicing variants of the estrogen or glucocorticoid receptor act as dominant-negative (DN) repressors (Oakley et al., 1996; Ogawa et al., 1998). In addition, the etiology of various human diseases has been traced to genetic lesions that yield DN proteins. For example, mutated forms of the thyroid hormone receptor β interfere with wild-type receptor function in patients with RTH (resistance to thyroid hormone) syndrome (Figure 1iv; Chatterjee, 1997) and mutations in the homeobox protein PITX2, which heterodimerizes with other homeodomain proteins, cause Rieger syndrome (Figure 1ii or iv, depending on the allele; Cushman and Camper, 2001).

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of potential configurations for a dominant-negative (DN) allelic form of an endogenous wild-type (wt) regulator. In this hypothetical example, based on nuclear hormone receptors, the wt functional TF (upper left) is a heterodimer between two subunits (blue and green), each possessing a distinct DNA-binding domain (DBD) and functional domain (FD). The various DN forms are: (i) a deletion of the DBD; (ii) a mutated DBD; (iii) a deleted FD; (iv) a mutated FD; and (v) a different FD with a functional heterodimerization interface. Impairment in DNA binding is indicated by the ‘floating’ of the complex above the DNA.

The effects of DN repressors are consequences of the fact that many proteins contain separable functional domains (Figure 1). This property has been exploited to design artificial DN repressors in which a non-functional amphipathic acidic extension is linked to a leucine zipper to yield proteins that dimerize with high affinity and specificity to bHLH-Zip and bZIP TFs and abolish DNA binding (Figure 1ii; Krylov et al., 1997). This type of DN repressor has also successfully been used to ablate various pathways in transgenic animals (e.g. Moitra et al., 1998).

Design of transcription factors with novel DNA-binding specificities

A comprehensive endogenous gene control platform requires the ability to select or design DNA-binding domains (DBDs) with novel, pre-determined DNA-sequence specificities. The Cys2–His2 zinc finger—the most common natural DNA-binding motif (Tupler et al., 2001)—has emerged as the domain of choice for this method. Naturally occurring zinc finger proteins (ZFPs) have diverse target sites (Wolfe et al., 2000a), proving that this motif is adaptable. Structural studies of ZFP–DNA complexes (Pavletich and Pabo, 1991; Houbaviy et al., 1996) showed that these proteins use multiple, tandem fingers to interact with a series of adjacent subsites (typically, 3 or 4 base pairs each) in the major groove of the DNA. Considerable functional autonomy in the recognition of a subsite target by each finger enables ‘mix and match’ DNA-binding protein design, in which fingers with known subsite preferences are linked to yield multifinger proteins with a high affinity for desired target sequences (reviewed in Choo and Isalan, 2000; Pabo et al., 2001; Segal and Barbas, 2001; Beerli and Barbas, 2002). Numerous fingers with distinct sequence preferences have been described. Some of these have been derived from naturally occurring proteins, but most have been produced by selection or design efforts aimed at modifying zinc finger specificity in order to expand the combined repertoire and, thus, encompass the broadest possible range of target sites (Desjarlais and Berg, 1992; Choo and Klug, 1994; Jamieson et al., 1994; Rebar and Pabo, 1994; Greisman and Pabo, 1997). Multiple fingers (usually 3–6) have been joined to obtain ZFPs which recognize target sequences of 9–18 base pairs (Choo and Isalan, 2000; Wolfe et al., 2000b; Pabo et al., 2001).

Naturally occurring Cys2–His2 ZFPs perform a variety of functions (Davidson, 2001): for example, Sp1 is a transcriptional activator, Kox-1 is a transcriptional repressor, and CTCF is an insulator. This indicates that a wide spectrum of functional domains may be used in fusions with a designed ZFP-based DBD. In agreement with this expectation, various modules including activation domains from viral protein 16 (VP16), nuclear hormone receptors, and NF-κB, and repression domains from Krüppel-associated box (KRAB)-containing regulators, have been successfully used in the context of designed ZFP TFs (Table I). Studies in Drosophila have shown that regulatory domain efficacy can be distance dependent (Mannervik et al., 1999). The active range of functional domains fused to designed ZFPs within a chromatin environment has not been comprehensively investigated, and most published studies (Table I) use designed proteins that target the immediate promoter region, although some exceptions exist. The silent erythropoietin gene has been activated by a single ZFP–VP16 fusion bound to [–862] relative to the transcription start site (Zhang et al., 2000). A ZFP–KRAB fusion that binds to and represses the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) γ2 promoter also affects transcription originating from the PPARγ1 promoter located ∼60 kb upstream (Ren et al., 2002), but it is not clear whether this latter repression occurs at the level of transcriptional initiation or elongation. Both for basic science and therapeutic purposes, it will be of interest to investigate how (and if) the behavior of specific functional domains changes depending on the promoter type to which they are targeted, and on the distance from the transcription start site.

Table I. Regulation of endogenous genes resident in their native chromosomal locus using designed ZFP TFs.

| Target gene | ZFP used | Functional domain | Location of target sequence relative to [+1] and its chromatin organization | Effect on gene | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDR1 | 5-finger | KRAB (two copies) | [–50]; n.d. | Repression of induction | ZFP target overlaps Sp1 site | Bartsevich and Juliano (2000) |

| Erythropoietin | 3-finger | VP16 | [–862]; linker DNA between two nucleosomes | Activation | In cell line used, gene is completely silent and unresponsive to hypoxia | Zhang et al. (2000) |

| VEGF-A | 3-finger | VP16 and NF-κB p65 | [–500], [+1], [+500]; all 3 in DNase I hypersensitive site | Activation | Multiple splice isoforms upregulated proportionately | Liu et al. (2001) |

| erbB-2 | 6-finger | VP64 (VP16 × 4) | [+20]; n.d. | Activation | ErbB-2 activators do not activate ErbB-3 | Beerli et al. (2000a); Dreier et al. (2001) |

| erbB-3 | 6-finger | VP64 (VP16 × 4) | [+50]; n.d. | |||

| erbB-3 | 6-finger | KRAB | [+50]; n.d. | Repression | Cells exhibit growth arrest when erbB-2 is repressed. | Beerli et al. (2000a); Dreier et al. (2001) |

| PPARγ1 and 2 | 6-finger | KRAB | [–200] of γ2; DNase I hypersensitive site | Repression of induction | Repression prevents adipogenesis | Ren et al. (2002) |

n.d., not determined.

The activity of the ZFP–functional domain chimera can be controlled through several strategies. For example, the level of the designed TF in the cell can be modulated by driving its synthesis with a promoter that responds to a small molecule, such as an ecdysteroid or tetracycline, whose titer has been shown to accurately correlate with the activity of the gene targeted by the TF (for example, see Kang and Kim, 2000; Zhang et al., 2000). Alternatively, a synthetic ‘nuclear hormone receptor’ that fuses a designed ZFP DBD to a functional ligand-responsive module (for example, progesterone- or estrogen-responsive) can be created (Beerli et al., 2000b; Beerli and Barbas, 2002). With respect to the latter, class II nuclear hormone receptors function as repressors in the absence of ligand and as activators in its presence (Urnov and Wolffe, 2001). Thus, in principle, one could even use the same designed TF to either activate or repress the target gene.

Table I summarizes published data on the use of designed ZFP-based TFs to regulate endogenous genes in vivo (also reviewed in Reik et al., 2002). As discussed in the next section, it is important to make a distinction between the control of genes residing in their native chromosomal environment, and that of genes in other situations (e.g. in vitro, on transiently transfected episomes, etc.).

The challenge of chromatin

Chromatin imposes a complicated set of rules on TF action (Wolffe and Hansen, 2001). For example, locus-wide (Horak et al., 2002) and genome-wide (Ren et al., 2000) analysis of TF binding in vivo showed that only a fraction of ‘consensus’ sites are actually engaged by the TF inside the nucleus. Furthermore, major differences have been observed between the actions of a given TF in transient transfection-based reporter gene assays and its behavior on the chromosomal copy of the same DNA sequence (Smith and Hager, 1997). Interestingly, several ZFP TFs, including Sp1 (Li et al., 1994) and GATA-1 (Boyes et al., 1998), can bind chromatin in vitro with only moderate decreases in affinity relative to naked DNA, and in some cases can induce an ATP-independent perturbation in histone–DNA contacts (Boyes et al., 1998; Cirillo et al., 2002). Thus, simple models of the ‘chromatin is an obstacle’ variety are insufficient (Urnov, 2002).

A growing body of data describes the interplay between designed TFs and chromatin: in several studies (Table I) ZFPs were deliberately designed to bind DNase I hypersensitive sites in gene promoters in order to facilitate access and activation by the TF. In one notable study, a panel of 3-finger ZFPs was designed against various sites in the EPO gene promoter. In vitro, these proteins bound their intended target sites with high affinity and robustly activated a transiently transfected reporter plasmid (Zhang et al., 2000), and their efficiency was not significantly affected by the location of the ZFP target site within the promoter. However, in the case of the endogenous promoter, these same proteins exhibited markedly different behavior and only ZFPs designed to target a sequence upstream of an Alu element upregulated EPO to pharmacological levels (Zhang et al., 2000). Because Alu elements are known to direct translational and rotational histone octamer positioning (Englander and Howard, 1995), this suggested that chromatin at the silent EPO locus assumes a non-random organization. In fact, nucleosomes were found to assume a specific translational frame over the silent EPO gene promoter (Zhang et al., 2000).

Two other studies, which have illustrated the importance of TF target sites, examined designed ZFP regulation of the HER-2/neu/erbB-2 gene. In the case of this promoter, one ZFP–KRAB fusion directed to a target site located at ∼[+100] repressed the endogenous copy of this gene (Beerli et al., 2000a), but a second that was targeted closer to the transcription start site (∼[+30]) failed to do so (Dreier et al., 2001). This illuminates a poorly understood role for native nucleoprotein organization of the promoter in controlling regulatory factor access and action, as well as suggesting that designed regulators abide by the rules of chromatin, and may therefore be useful probes of its structure in vivo.

Various applications for these proteins in functional studies of the genome can also be envisaged. For example, designed ZFP-based repression of transcription of both isoforms of the PPARγ gene was recently used in a ‘mutation-free reverse genetics’ study and illuminated a unique contribution made by the PPARγ2 isoform (Ren et al., 2002). Similar conditional ‘transcription knockouts’ may be used to reversibly up- or downregulate endogenous genes, which code for components of the chromatin-based regulatory machinery, in order to gauge their role in regulating the genome.

Towards ‘transcription therapy’ with designed regulators

In addition to their applications in basic science, designed TFs also have the potential to effect therapeutic control of specific genes in vivo, since aberrant gene transcription underlies a significant proportion of human disease. Remission could potentially be achieved by selectively down- or upregulating a relatively small number of genes. Increased transcription of the fetal γ-globin gene (by inhibiting its normal silencing) in sickle cell anemia patients has already been shown to alleviate the phenotype caused by mutation of the adult β-globin gene (Noguchi et al., 1988), and designed ZFPs may even be capable of activating silenced fetal globin genes (A. Reik, unpublished). The possibility of using ZFPs to regulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in pro- and anti-angiogenic therapies (Liu et al., 2001) is also being actively investigated, as is the use of ‘transcription therapy’ in treating cancer, for which aberrant activity of oncogenic and tumor suppressive TFs has been directly and extensively implicated (see Table II and Pandolfi, 2001).

Table II. Transcription factor aberrations in cancer and possible ‘transcription therapies’.

| Transcription factor | Aberration | Cancer type | References | Possible transcription therapy? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RARα | Translocation leading to fusion with PML | Acute promyelocytic leukemia | Look et al. (1997) | Designed TF (DBD only) mimicking RAR to compete at RAREs |

| AML1-ETO | ′′ | M2 (acute myelogenous leukemia) | Piazza et al. (2001) | Designed TF (DBD only) mimicking AML1 to compete at AML1 sites |

| c-Myc | Translocation leading to upregulated protein levels | Burkitt’s lymphoma | Gaidano and Dalla-Favera (2001) | Designed TF repressor for Ig promoter |

| BCL6 | ′′ | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Gaidano and Dalla-Favera (2001) | Designed TF that activates BCL6-repressed genes |

| WT1 | Nonsense mutations leading to truncation | Renal; soft tissue sarcoma | Lee et al. (1999) | Designed TF activator for WT1 targets |

| TLS/FUS and EWS | Translocation leading to chimeric fusion protein | Sarcoma | Aman (1999) | Unclear |

| p53 and Rb | Loss-of-function mutations | Many | Hanahan and Weinberg (2000) | Designed TF activator for Rb target genes |

Oncogenic transcriptional events are potentially amenable to correction through transcription therapy at various levels of intervention (Table II): (i) blockage of the aberrant function of chimeric TFs or the reversal of excessive transcriptional activity through the use of DN proteins; (ii) de-repression of tumor suppressor gene expression when epigenetically silenced through chromatin remodeling, for example by hypermethylation of CpG islands in gene promoters (Baylin et al., 1998); and (iii) repression/de-repression of biologically relevant targets of TFs whose expression is aberrant in cancer pathogenesis. Transcriptional regulatory approaches are already proving to be effective in diseases such as acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), which is caused by a chromosomal translocation that fuses the retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) gene to heterologous partners (Piazza et al., 2001), forming a DN transcriptional repressor that targets histone deacetylase (HDAC) (Grignani et al., 1998; He et al., 1998; Lin et al., 1998). The overexpression of inhibitors of HDACs (HDACIs) in combination with RA have induced leukemia remission and prolonged survival (Warrell et al., 1998; He et al., 2001), indicating that the approach in general may be very successful. Nevertheless, the lack of specificity for aberrant transcription complexes and target genes may prove to be a major potential limitation of this approach. Hence there is a need to focus on more targeted methods that use ZFPs, polyamides or other molecules that selectively regulate genes. Not only may this intervention render the therapeutic effects more selective, but possibly also less toxic. Furthermore, ZFPs or other molecules that can bind a DNA sequence with high specificity could be utilized to mimic the transcriptional activity of powerful tumor suppressor proteins such as p53 or Rb, thus exerting a broader antitumor activity in cancers of various histological origins.

The utilization of ZFPs or polyamides for cancer therapy does not preclude, but in fact calls for, the use of ‘transcription therapy’ modalities, either in combination or sequentially. While combinatorial/sequential regimens for cancer treatment are known to often reach greater efficacy by reducing resistance to therapy, in a ‘transcription therapy’ setting, such regimens might in fact be essential for successful reactivation of gene expression, since the combinatorial use of transcriptionally active compounds may convey specificity and potentiate efficacy, in turn reducing toxicity and immunogenicity. Finally, transcription therapy for cancer may be combined with known effective chemotherapeutic agents and even tailored to enhance their efficacy. It is conceivable that drug uptake and/or the biological response to a chemotherapeutic agent (i.e. the apoptotic response) in cancer cells may be modulated at the transcription level through repression or induction of relevant target genes (e.g. by modulating the expression of detoxifying pumps or anti-apoptotic molecules). Based on these premises, there is little doubt that chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation with transcriptionally active compounds will have a remarkable and immediate impact on the ways in which cancer and other diseases are treated in the post-genomic era.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We sincerely apologize to the many authors of important primary research studies whose work could not be cited directly due to space limitations. We would encourage the reader to consult the many comprehensive reviews cited for details. We thank Casey Case, Carl Pabo, Sean Brennan and Philip Gregory for comments on the manuscript, and Erica Dumais for drawing Figure 1. Along with this entire review series, the present paper is dedicated to the memory of our colleague and friend Alan Wolffe, who did so much to illuminate the central role of chromatin in genome control.

References

- Aman P. (1999) Fusion genes in solid tumors. Semin. Cancer Biol., 9, 303–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsevich V.V. and Juliano, R.L. (2000) Regulation of the MDR1 gene by transcriptional repressors selected using peptide combinatorial libraries. Mol. Pharmacol., 58, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S.B., Herman, J.G., Graff, J.R., Vertino, P.M. and Issa, J.P. (1998) Alterations in DNA methylation: a fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv. Cancer Res., 72, 141–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli R.R. and Barbas, C.F., III (2002) Engineering polydactyl zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat. Biotechnol., 20, 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli R.R., Dreier, B. and Barbas, C.F., III (2000a) Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes by designed transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 1495–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli R.R., Schopfer, U., Dreier, B. and Barbas, C.F., III (2000b) Chemically regulated zinc finger transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 32617–32627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S.L. (2001) An embarrassment of niches: the many covalent modifications of histones in transcriptional regulation. Oncogene, 20, 3007–3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes J., Omichinski, J., Clark, D., Pikaart, M. and Felsenfeld, G. (1998) Perturbation of nucleosome structure by the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. J. Mol. Biol., 279, 529–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch D.A. and Corey, D.R. (2001) Synthesis, analysis, purification, and intracellular delivery of peptide nucleic acids. Methods, 23, 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee V.K. (1997) Resistance to thyroid hormone. Horm. Res., 48, 43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Y. and Isalan, M. (2000) Advances in zinc finger engineering. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 10, 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Y. and Klug, A. (1994) Selection of DNA binding sites for zinc fingers using rationally randomized DNA reveals coded interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 11168–11172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo L.A., Lin, F.R., Cuesta, I., Friedman, D., Jarnik, M. and Zaret, K.S. (2002) Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol. Cell, 9, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman L.J. and Camper, S.A. (2001) Molecular basis of pituitary dysfunction in mouse and human. Mamm. Genome, 12, 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E.H. (2001) Genomic Regulatory Systems. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Demidov V.V. and Frank-Kamenetskii, M.D. (2001) Sequence-specific targeting of duplex DNA by peptide nucleic acids via triplex strand invasion. Methods, 23, 108–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervan P.B. (2001) Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem., 9, 2215–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais J.R. and Berg, J.M. (1992) Toward rules relating zinc finger protein sequences and DNA binding site preferences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 7345–7349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier B., Beerli, R.R., Segal, D.J., Flippin, J.D. and Barbas, C.F., III (2001) Development of zinc finger domains for recognition of the 5′-ANN-3′ family of DNA sequences and their use in the construction of artificial transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 29466–29478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander E.W. and Howard, B.H. (1995) Nucleosome positioning by human Alu elements in chromatin. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 10091–10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov D.V. and Kadonaga, J.T. (2001) The many faces of chromatin remodeling. SWItching beyond transcription. Cell, 106, 523–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidano G. and Dalla-Favera, R. (2001) Molecular biology of lymphomas. In DeVita, V.T., Hellman, S. and Rosenberg, S.A. (eds), Principles and Practice of Oncology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, New York, NY, pp. 2215–2235.

- Grandori C., Cowley, S.M., James, L.P. and Eisenman, R.N. (2000) The Myc/Max/Mad network and the transcriptional control of cell behavior. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol., 16, 653–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory P.D. (2001) Transcription and chromatin converge: lessons from yeast genetics. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 11, 142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greisman H.A. and Pabo, C.O. (1997) A general strategy for selecting high-affinity zinc finger proteins for diverse DNA target sites. Science, 275, 657–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grignani F. et al. (1998) Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-α recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature, 391, 815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager G.L. (2001) Understanding nuclear receptor function: from DNA to chromatin to the interphase nucleus. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 66, 279–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. and Weinberg, R.A. (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell, 100, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.Z., Guidez, F., Tribioli, C., Peruzzi, D., Ruthardt, M., Zelent, A. and Pandolfi, P.P. (1998) Distinct interactions of PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα with co-repressors determine differential responses to RA in APL. Nat. Genet., 18, 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.Z., Tolentino, T., Grayson, P., Zhong, S., Warrell, R.P., Jr, Rifkind, R.A., Marks, P.A., Richon, V.M. and Pandolfi, P.P. (2001) Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce remission in transgenic models of therapy-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Invest., 108, 1321–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak C.E., Mahajan, M.C., Luscombe, N.M., Gerstein, M., Weissman, S.M. and Snyder, M. (2002) GATA-1 binding sites mapped in the β-globin locus by using mammalian chIp-chip analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 2924–2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houbaviy H.B., Usheva, A., Shenk, T. and Burley, S.K. (1996) Co-crystal structure of YY1 bound to the adeno-associated virus P5 initiator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 13577–13582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G. and Zamore, P.D. (2002) RNAi: nature abhors a double-strand. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 12, 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson A.C., Kim, S.H. and Wells, J.A. (1994) In vitro selection of zinc fingers with altered DNA-binding specificity. Biochemistry, 33, 5689–5695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J.S. and Kim, J.S. (2000) Zinc finger proteins as designer transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 8742–8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khochbin S., Verdel, A., Lemercier, C. and Seigneurin-Berny, D. (2001) Functional significance of histone deacetylase diversity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 11, 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov D., Echlin, D.R., Taparowsky, E.J. and Vinson, C. (1997) Design of dominant negatives to bHLHZip proteins that inhibit DNA binding. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 224, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.B. et al. (1999) The Wilms tumor suppressor WT1 encodes a transcriptional activator of amphiregulin. Cell, 98, 663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Adams, C.C. and Workman, J.L. (1994) Nucleosome binding by the constitutive transcription factor Sp1. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 7756–7763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R.J., Nagy, L., Inoue, S., Shao, W., Miller, W.H., Jr and Evans, R.M. (1998) Role of the histone deacetylase complex in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature, 391, 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.Q. et al. (2001) Regulation of an endogenous locus using a panel of designed zinc finger proteins targeted to accessible chromatin regions. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor A. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 11323–11334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Look A.T. (1997) Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science, 278, 1059–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannervik M., Nibu, Y., Zhang, H. and Levine, M. (1999) Transcriptional coregulators in development. Science, 284, 606–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapp A.K., Ansari, A.Z., Ptashne, M. and Dervan, P.B. (2000) Activation of gene expression by small molecule transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 3930–3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merika M. and Thanos, D. (2001) Enhanceosomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 11, 205–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra J. et al. (1998) Life without white fat: a transgenic mouse. Genes Dev., 12, 3168–3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi C.T., Rodgers, G.P., Serjeant, G. and Schechter, A.N. (1988) Levels of fetal hemoglobin necessary for treatment of sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med., 318, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley R.H., Sar, M. and Cidlowski, J.A. (1996) The human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform. Expression, biochemical properties, and putative function. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 9550–9559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S., Inoue, S., Watanabe, T., Orimo, A., Hosoi, T., Ouchi, Y. and Muramatsu, M. (1998) Molecular cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor βcx: a potential inhibitor of estrogen action in human. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 3505–3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabo C.O., Peisach, E. and Grant, R.A. (2001) Design and selection of novel Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 70, 313–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi P.P. (2001) Transcription therapy for cancer. Oncogene, 20, 3116–3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavletich N.P. and Pabo, C.O. (1991) Zinc finger–DNA recognition: crystal structure of a Zif268–DNA complex at 2.1 Å. Science, 252, 809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza F., Gurrieri, C. and Pandolfi, P.P. (2001) The theory of APL. Oncogene, 20, 7216–7222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebar E.J. and Pabo, C.O. (1994) Zinc finger phage: affinity selection of fingers with new DNA-binding specificities. Science, 263, 671–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik A., Gregory, P.D. and Urnov, F.D. (2002) Biotechnologies and therapeutics: chromatin as a target. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 12, 233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B. et al. (2000) Genome-wide location and function of DNA binding proteins. Science, 290, 2306–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D., Collingwood, T.N., Rebar, E.J., Wolffe, A.P. and Camp, H.S. (2002) PPARγ knockdown by engineered transcription factors: exogenous PPARγ2 but not PPARγ1 reactivates adipogenesis. Genes Dev., 16, 27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedivy J.M. (2002) Gene targeting comes to top-down drug screens. Trends Biotechnol., 20, 92–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal D.J. and Barbas, C.F. (2001) Custom DNA-binding proteins come of age: polydactyl zinc-finger proteins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 12, 632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.L. and Hager, G.L. (1997) Transcriptional regulation of mammalian genes in vivo. A tale of two templates. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 27493–27496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupler R., Perini, G. and Green, M.R. (2001) Expressing the human genome. Nature, 409, 832–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov F.D. (2002). A feel for the template: zinc finger proteins and chromatin. Biochem. Cell Biol., 80, 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov F.D. and Wolffe, A.P. (2001) A necessary good: nuclear hormone receptors and their chromatin templates. Mol. Endocrinol., 15, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrell R.P. Jr, He, L.Z., Richon, V., Calleja, E. and Pandolfi, P.P. (1998) Therapeutic targeting of transcription in acute promyelocytic leukemia by use of an inhibitor of histone deacetylase. J. Natl Cancer Inst., 90, 1621–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe S.A., Nekludova, L. and Pabo, C.O. (2000a) DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 29, 183–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe S.A., Ramm, E.I. and Pabo, C.O. (2000b) Combining structure-based design with phage display to create new Cys2His2 zinc finger dimers. Structure Fold Des., 8, 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe A.P. (1998) Chromatin Structure and Function. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Wolffe A.P. and Hansen, J.C. (2001) Nuclear visions: functional flexibility from structural instability. Cell, 104, 631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrick J.J. and Young, R.A. (2002) Deciphering gene expression regulatory networks. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 12, 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaret K.S. (1995) Nucleoprotein architecture of the albumin transcriptional enhancer. Semin. Cell Biol., 6, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. (2000) Synthetic zinc finger transcription factor action at an endogenous chromosomal site. Activation of the human erythropoietin gene. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 33850–33860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]