Abstract

Pertussis infection is increasingly recognized in older children and adults, indicating the need of booster immunizations in these age groups. We investigated the induction of pertussis-specific immunity in schoolchildren and adults after booster immunization and natural infection. The expression of mRNA of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, and IL-5 in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was assayed by reverse transcription-PCR. The PBMCs of 17 children immunized with one dose of an acellular vaccine containing pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), and pertactin (PRN) significantly proliferated in vitro after stimulation with the vaccine antigens. The PBMCs of seven infected individuals markedly proliferated in the presence of PT and FHA, but the cells of only two of these subjects responded to PRN. At least one of the antigens induced mRNA for IL-4 and/or IL-5 in the cells of 93% of tested vaccinees and patients, and FHA induced IFN-γ mRNA in the cells of two-thirds of them. Expression of mRNA for IFN-γ correlated with the production of the cytokine protein. Anti-FHA immunoglobulin G antibodies significantly correlated with FHA-induced proliferative responses both before and after immunization. These results show that booster immunization with acellular pertussis vaccine induces both antibody- and cell-mediated immune responses in schoolchildren. Further, booster immunization and natural infection seem to induce the expression of mRNA of T-helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 type cytokines in similar manners. This observation supports the use of acellular pertussis vaccines for booster immunizations of older children, adolescents, and adults.

Pertussis is a highly contagious respiratory disease caused by Bordetella pertussis, which particularly threatens nonimmunized infants. The disease has remained endemic and epidemic in immunized populations (6–8, 18, 40). Pertussis infection is increasingly recognized in older children and adults (5, 8, 19, 25, 26, 31). This indicates that the immunity imparted by childhood immunizations wanes below the protective level in these age groups and stresses the need of booster immunizations. Modern acellular vaccines, being less reactogenic than conventional whole-cell vaccines, seem to be suitable not only for primary immunization but also for boostering (11, 12, 16, 17). At present, four components of B. pertussis, pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin (PRN), and fimbrial antigens, are regarded as candidate antigens to be included in acellular vaccines (11, 12). However, the significance of immune responses to each of these components in preventing infection and disease is not fully known.

Antibodies have been traditionally thought to play an important role in protection against pertussis, because B. pertussis was considered to be an extracellular pathogen. PT, FHA, and PRN, used singly or in combination, have induced good antibody responses and protective immunity in experimental animals (21, 35, 37). However, in clinical efficacy trials of acellular vaccines, no clear correlation has been found between serum antibody levels and protection (1).

Increasing evidence suggests that cell-mediated immunity is involved in immune protection against pertussis. Several reports have shown that B. pertussis can survive in mammalian cells, including macrophages, in vitro and in vivo (3, 13, 14, 36). Further, T lymphocytes specific for B. pertussis or its components have been demonstrated in humans and mice after infection (9, 15, 24, 27–30, 39). In a recent study (34), Ryan et al. demonstrated a preferential induction of T-helper 1 (Th1) cells in preschool children with B. pertussis infection. Zepp et al. reported that primary immunization with a tricomponent acellular pertussis vaccine induced predominantly Th1 cells in infants (41). In contrast, Ausiello et al., also by vaccinating infants, found that an acellular vaccine induced cytokines of both types, whereas a whole-cell vaccine induced cytokines of Th1 type (2). However, there are practically no studies comparing the effects of booster immunization and natural infection on cell-mediated immunity in schoolchildren and adults.

We investigated pertussis-specific cell-mediated immune responses by proliferation assay of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in schoolchildren and adults after either natural infection or booster immunization. The mRNAs of Th1 and Th2 type cytokines were assayed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) in the PBMCs of the subjects. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-5 (IL-5) were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the culture media of the PBMCs of the adult vaccinees.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccines.

One dose of the combined diphtheria-tetanus-trivalent acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine contained 1.5 limit of flocculation (Lf) of diphtheria toxoid, 5 Lf of tetanus toxoid, 8 μg of PT, 8 μg of FHA, and 2.5 μg of PRN. The bivalent acellular vaccine contained 25 μg of PT and 25 μg of FHA. Both acellular vaccines were produced by SmithKline Beecham Biologicals (Rixensart, Belgium). The control vaccine (DT), from the National Public Health Institute (NPHI), Helsinki, Finland, included 2 Lf of diphtheria toxoid and 5 Lf of tetanus toxoid.

Subjects.

The study subjects consisted of 20 vaccinees (17 children and 3 adults) and 8 pertussis patients (6 children and 2 adults). The 17 child vaccinees (9 males and 8 females) were randomly selected among 118 10- to 12-year-old children immunized with the DTaP vaccine 1 month before testing. All child vaccinees had been immunized in infancy with three doses of the Finnish whole-cell pertussis vaccine combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and had received a booster dose at 2 years of age. Five children (V1 to V5), randomly selected from the 17 child vaccinees, were tested for cytokine mRNA expression. The three adult vaccinees (V6 to V8; 56, 44, and 47 years, respectively) were all males and belonged to the personnel of the NPHI, Department in Turku. They had received a dose of the bivalent acellular vaccine 6 years before this study. Of them, only V7 had received the primary three doses of the whole-cell vaccine. The eight culture-confirmed pertussis patients (three males and five females) included two adults (P1 and P2; 60 and 26 years) and six 13-year-old children (P3 to P8). P2 to P8 had been immunized with four doses of the whole-cell pertussis vaccine in childhood. P3 to P8 were all from a school class where a pertussis outbreak occurred. At the time of sampling, P6 and P7 were asymptomatic, and the others had had cough for 1 to 17 weeks.

Twenty-five healthy subjects (10 males and 15 females) served as controls. Nine of them were randomly selected among 117 10- to 12-year-old children who had received a booster dose of the DT vaccine 1 month before testing; eight (C1 to C8) were adults (aged 20 to 40 years) recruited from the NPHI, Department in Turku, six (C9 to C14) were 13-year-old healthy pupils, and two (C15 and C16) were newborns. Except for the two newborns, all control subjects had received primary three doses of the whole-cell pertussis vaccine, and all schoolchildren had also received a booster dose at 2 years of age.

Cell preparation and culture.

PBMCs were isolated from heparinized blood by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated (30 min at 56°C) human AB serum (Finnish Blood Bank, Helsinki, Finland) and 1% (wt/vol) glutamine (29.2 mg/ml; Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beth Haemek, Israel), supplemented with penicillin (10,000 U/ml), streptomycin (10 mg/ml), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) (Biological Industries), at 37°C in air with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity in a CO2 incubator.

Proliferation assay.

For proliferation assay, the preliminary experiments indicated the following optimal doses of antigens: PT, 1 μg/ml; FHA, 1 μg/ml, and PRN, 2.5 μg/ml. Cells (105) were cultured in round-bottom microtiter wells (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) in a volume of 200 μl per well in the presence of purified antigens provided by SmithKline Beecham Biologicals (33). The same lots of antigens were used throughout the study. To eliminate mitogenicity, PT was heat inactivated (45 min at 95°C) before use (9). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) M (1:50 [vol/vol]; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and pokeweed mitogen (1:8,000 [vol/vol]; GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.) were used for testing the mitogenic reactivity of PBMCs. PBMCs cultured without stimulus were used for evaluation of spontaneous responses. The cells were cultured for 3 days with PHA and for 6 days with pokeweed mitogen and the antigens. [3H]thymidine (0.5 μCi/well; Dupont, Antwerp, Belgium) was added for the last 16 h of incubation. The cells were harvested, and incorporated radioactivity was assessed with a scintillation counter (Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland). The results were expressed as mean counts per minute for triplicate cultures. An antigen-induced proliferative response four times higher than spontaneous proliferation was considered positive. The specimens of six subjects were handled in one analysis run.

To study the variation of results between runs, blood samples were collected five times during 10 weeks from an adult patient with culture-confirmed pertussis. The first sample was obtained when she had been coughing for 2 weeks. All five samples gave positive proliferative responses to PT and FHA and negative proliferation to PRN. The means and standard deviations of the stimulation index (SI) were as follows: for PT, 11.1 ± 1.8; for FHA, 11.9 ± 4.1; and for PRN, 1.8 ± 1.4.

RNA isolation.

For cytokine RT-PCR, the cell cultures used for mRNA determinations were run in parallel with proliferation cultures. The cells were cultured in triplicate at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells in round-bottom wells in a volume of 200 μl per well in the presence of antigens or PHA. The concentrations of antigens and PHA were the same as those described above. The cells cultured in a plain medium served as controls for spontaneous cytokine expression. After 2 days of culture, the plate was centrifuged (1,000 rpm) for 5 min, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were stored at −20°C for RNA isolation.

Total RNA was extracted from the pelleted cells by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, 100 μl of lysis buffer was added to the pellet; cell lysates from triplicate wells were combined and homogenized with QIAshredder (Qiagen) and then mixed with an equal volume of 70% ethanol. The mixture was applied onto an RNeasy spin column and centrifuged. Flowthrough was discarded. The spin column was washed three times with washing buffer, and total RNA was eluted with 35 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated distilled water.

RT-PCR.

Table 1 shows the primers specific for cytokines and β-actin. Cytokine primers were as described earlier, whereas β-actin primers were modifications of those described earlier (4, 22, 23, 38). Extracted RNA was first treated with DNase I (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) and then used for cDNA synthesis in the SuperScript preamplification system (GIBCO). Briefly, 11 μl of DNase-treated RNA and 1 μl of random hexamers (50 ng) were heated to 70°C for 10 min and then cooled on ice for 2 min. Then 7 μl of reaction mixture containing 2 μl of 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4) and 500 mM KCl, 2 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix and 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol was added, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C for 5 min. After addition of 1 μl (200 U) of reverse transcriptase, the mixture was incubated first at 25°C for 10 min and then at 42°C for 50 min. The reaction was stopped by incubation at 70°C for 15 min; then 1 μl of RNase H was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The cDNA in 21 μl was diluted with 63 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated distilled water and stored at −20°C for the PCR.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primer pairs used for PCR amplification in cytokine RT-PCR

| Cytokine | 5′ sense primer | 3′ antisense primer | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | TGT TAC TGC CAG GAC CCA TAT GTA | TCT TCG ACC TTG AAA CAG CAT CTG | 429 |

| IL-2 | ATG TAC AGG ATG CAA CTC CTG TCT T | GTC AGT GTT GAG ATG ATG CTT TGA C | 458 |

| IL-4 | CCT CTG TTC TTC CTG CTA GCA TGT GCC | CAA CGT ACT CTG GTT GGC TTC CTT CAC | 372 |

| IL-5 | GCA CAC TGG AGA GTC AAA CT | CAC TCG GTG TTC ATT ACA CC | 177 |

| β-Actin | GAA ATC GTG CGT GAC ATT AAG GAG | ATA CTC CTG CTT GCT GAT CCA CAT | 465 |

Cytokine RT-PCR assays were first optimized, and the number of cycles used was adjusted to ensure that PCR products were analyzed before they reached saturation. The differences in RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis were normalized to a housekeeping gene, β-actin. The PCR mixture of 50 μl contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 200 μM each dNTP, and 1 (or 0.5) U of DNA polymerase (DynaZyme; Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland). The primer concentrations were 30 pmol for the PCR of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-5 and 10 pmol for the PCR of IL-4 and β-actin; 4 μl of diluted cDNA was added for the PCR of IL-2 and β-actin, and 8 μl was added for PCR of the other cytokines. In a thermal reactor (TouchDown; Hybaid, Middlesex, England), each PCR program was started with denaturation at 94°C for 5 min and ended with final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Subsequent conditions were as follows: for β-actin, 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min; for IL-2 and IFN-γ, 35 and 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 63°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; for IL-4, 65°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 72°C for 1.5 min, 94°C for 1 min, and 65°C for 1 min; and for IL-5, 38 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min. The resulting PCR products (16 μl) were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Samples in which reverse transcription was omitted but all reagents were included were used as negative controls in the PCR. To verify the performance of the first-strand cDNA synthesis and amplification reaction, 50 ng of control RNA provided with the cDNA synthesis kit was also reverse transcribed, and 1/20 of the cDNA obtained was amplified in the PCR. All samples were tested twice. Patients P5 and P6 were not tested for cytokine mRNA expression because not enough cells were available.

Cytokine assays.

PBMCs at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells were cultured in 96-well plates with the antigens or PHA as described for the proliferation assay, and supernatants were removed after 48 h. IFN-γ and IL-5 were chosen to represent type 1 and type 2 cytokines, respectively. Their concentrations were measured by a commercial ELISA kit (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) with threshold detection values of 15.6 pg/ml for IFN-γ and 7.8 pg/ml for IL-5. IL-5 was selected instead of IL-4 because of well-known low sensitivity of commercial kits for IL-4 and because the level of transcription of the IL-4 gene is lower than the level of transcription of the IL-5 gene (2, 41).

Measurement of IgG antibodies.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against PT, FHA, and PRN were measured by ELISA in the laboratory of SmithKline Beecham Biologicals as described previously (20, 33). The results were expressed as ELISA units per milliliter. The threshold detection level of the test was 5 ELISA units/ml.

Statistical analyses.

Fisher’s exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used for the analysis of statistical significance, and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used for the analysis of correlations. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Proliferative responses to B. pertussis antigens.

The PBMCs of the 17 children immunized with the DTaP vaccine showed significantly higher proliferative responses to PT, FHA, and PRN than the cells of the 9 children immunized with the DT vaccine (for PT, P = 0.0015; for FHA, P < 0.0001; for PRN, P = 0.0053 [Table 2]). The two groups of vaccinees did not differ in their PHA and pokeweed mitogen responses (data not shown). After immunization with DTaP, the proliferative responses of 14 (82%) individuals increased significantly, and all individuals showed a positive proliferative response (SI ≥ 4) to at least one of the three antigens. No corresponding conversions were seen in the proliferative responses of the control subjects immunized with DT. Three adult individuals (V6 to V8) had been immunized with the bivalent vaccine containing PT and FHA 6 years before testing. Proliferation assays of the PBMCs of these three subjects were repeated 1 year after the first testing, and very similar results were obtained (Fig. 1A). The PBMCs of two of these vaccinees (V6 and V7) responded with a significant proliferation to PT and FHA, whereas the cells of the third were totally unresponsive to these antigens. None of these three adult vaccinees had significant SI of PRN (SI ≥ 4).

TABLE 2.

Proliferative response of PBMCs of schoolchildrena before and 1 month after immunization

| Antigen | Median cpm (range)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before immunization

|

After immunization

|

|||

| DT | DTaP | DT | DTaP | |

| Medium | 183 (40–554) | 95 (42–451)b | 220 (114–1,355) | 234 (51–1,352)b |

| PT | 950 (183–3,622) | 272 (66–4,642)b | 501 (121–3,061) | 2,010 (334–21,225)c |

| FHA | 1,500 (248–2,996) | 332 (52–2,654)b | 2,037 (271–2,998) | 4,600 (1961–18,664)c |

| PRN | 470 (77–3,581) | 189 (44–8,077)b | 803 (295–2,551) | 2,374 (366–17,824)c |

Seventeen immunized with a dose of DTaP vaccine; nine immunized with DT vaccine.

No statistically significant difference was found between children who were immunized with DTaP and DT vaccines.

Statistically significant differences were found between children who were immunized with DTaP and DT vaccines: for PT, P = 0.0015; for FHA, P < 0.0001; and for PRN, P = 0.0053.

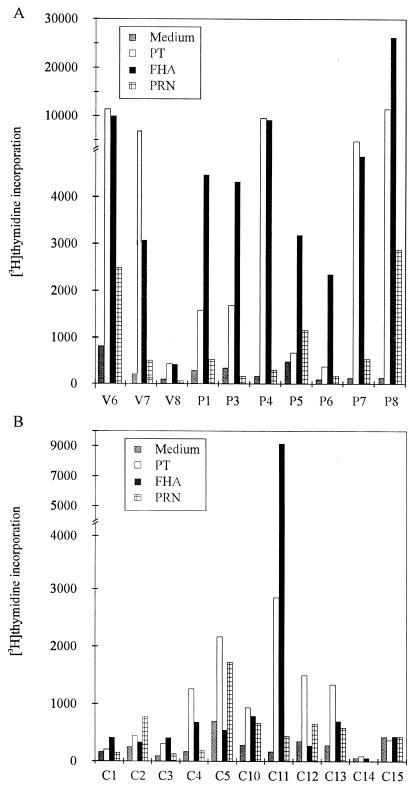

FIG. 1.

Proliferative responses to PT, FHA, and PRN of the PBMCs of the adult vaccinees (V6 to V8) and culture-confirmed pertussis patients (P1 and P3 to P8) (A) and of the healthy controls (B). V6 to V8 had received a dose of bivalent acellular vaccine (PT and FHA) 7 years before testing. The concentrations of PT, FHA, and PRN were 1, 1, and 2.5 μg/ml, respectively.

Of the 26 child vaccinees, 17 immunized with DTaP and 9 immunized with DT, 16 (62%) showed proliferative responses to at least one of the three antigens before immunization: 13 (50%) responded to FHA, nine (35%) responded to PT, and seven (27%) responded to PRN.

The PBMCs of all seven pertussis patients (P1 and P3 to P8) showed positive proliferative responses to FHA and/or PT, but only two of them (P7 and P8) showed positive responses to PRN (SI ≥ 4 [Fig. 1A]). Subjects immunized with DTaP showed a strong proliferative response to PRN more frequently (14 of 17) than the infected individuals (2 of 7) (P = 0.021).

Cytokine mRNA expression induced by B. pertussis antigens.

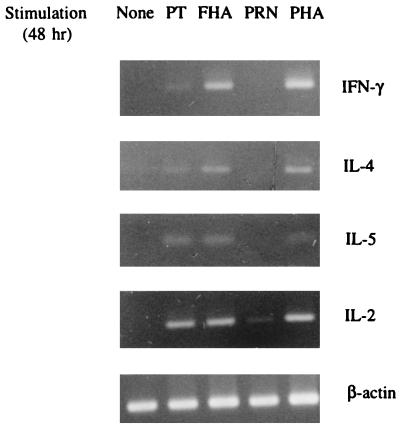

A pilot study on the kinetics of cytokine mRNA expression induced by the antigens was first carried out on the PBMCs of patient P1. The cells were cultured for 5 h, 20 h, 2 days, or 5 days and then subjected to RT-PCR (Fig. 2). PT and FHA induced expression of the IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-5 mRNAs by 2 days, but PRN induced only low expression of the IL-2 mRNA (weakly positive). Spontaneous production of the IL-2 and IL-4 mRNAs reached in 5 days the levels induced by the antigens. The best discrimination between antigen-induced and spontaneous production of cytokine mRNAs was obtained at 2 days of culture, and this incubation time was selected for further studies.

FIG. 2.

Representative cytokine mRNA expression as measured by RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from the PBMCs of the culture-confirmed adult patient with pertussis, unstimulated or stimulated by PT, FHA, PRN, or PHA for 48 h. The antigen and mitogen concentrations used are specified in the legend to Fig. 1. Results for FHA-induced IFN-γ and FHA- and PT-induced IL-2 were interpreted as positive (++), and those for FHA-induced IL-4 and IL-5, PT-induced IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-5, and PRN-induced IL-2 were interpreted as weakly positive (+).

Expression of the cytokine mRNAs in the PBMCs of 20 subjects (8 vaccinees, 6 infected persons, and 6 controls) was measured (Table 3). PHA stimulated the production of the mRNAs of all four cytokines in the PBMCs of all tested subjects (data not shown). Various levels of IL-2 mRNA were also detected in the antigen-stimulated PBMCs of all tested subjects except the two newborns (C15 and C16). In general, the proliferative responses of the PBMCs induced were stronger the higher the IL-2 mRNA expression. Expression of the mRNA for IL-4 and/or IL-5 was induced by at least one antigen in the PBMCs of all tested vaccinees and patients except V8. The PBMCs of the six controls did not produce the mRNAs for IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-5 after stimulation with any antigen. Expression of IFN-γ mRNA was less frequent after stimulation with PRN (2 of 11 tested) than after stimulation with FHA (10 of 14 tested) (P = 0.015). Expression of the cytokine mRNAs in the PBMCs of the immunized and infected subjects did not differ significantly from each other.

TABLE 3.

Cytokine mRNA expression in PBMCs

| Subjects (no.) | Antigen | % of subjects with cytokine mRNA expression

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | IL-2 | IL-4 | IL-5 | ||

| Vaccinees (8)a | PT | 38 | 100 | 38 | 88 |

| FHA | 63 | 100 | 38 | 50 | |

| PRN | 20 | 100 | 60 | 80 | |

| Patients (6)b | PT | 50 | 100 | 67 | 60 |

| FHA | 83 | 100 | 50 | 100 | |

| PRN | 17 | 100 | 33 | 20 | |

| Controls (6)c | PT | 0 | 67 | 0 | 0 |

| FHA | 0 | 67 | 0 | 0 | |

| PRN | 0 | 67 | 0 | 0 | |

Vaccinees (V1 to V5) were immunized with the DTaP vaccine containing PT, FHA, and PRN 1 month earlier; V6 to V8 had been immunized with the bivalent PT-FHA vaccine 7 years earlier and were not included in the results for responses to PRN.

All patients were culture positive for B. pertussis. At the time of sampling, five patients (P1 to P4 and P8) had been coughing for 1 to 17 weeks, and one patient (P7) was asymptomatic. IL-2 mRNA expression was weakly positive in the PBMCs stimulated with PRN; IL-5 mRNA expression was not tested in patient P2.

Four controls (C2 and C6 to C8) were healthy adults; two (C15 and C16) were newborns.

Production of IFN-γ and IL-5 protein.

Antigen-induced proliferation, cytokine mRNA expression, and cytokine production of the PBMCs of four subjects, V6, V7, V8, and C2, were tested in parallel (Fig. 1 and Table 4). Significant proliferation and production of IFN-γ mRNA and IFN-γ were detected in the PBMCs of V6 and V7 after stimulation with PT and FHA but not after stimulation with PRN. The cells of V8 and C2 did not produce IFN-γ after stimulation with any antigen. IL-5 mRNA was detected in the PBMCs of V6 and V7 after stimulation with PT, but no IL-5 was detected.

TABLE 4.

Expression of cytokine mRNAs in and production of cytokine proteins by PBMCs of four subjects

| Subjecta | Antigen | IFN-γ

|

IL-5 mRNA expression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA expressionb | Proteinc (pg/ml) | |||

| V6 | PT | ++ | 47 | + |

| FHA | ++ | 140 | − | |

| PRN | − | <15.6 | − | |

| V7 | PT | ++ | 39 | + |

| FHA | ++ | 46 | − | |

| PRN | − | <15.6 | − | |

| V8 | PT | − | <15.6 | − |

| FHA | + | <15.6 | − | |

| PRN | − | <15.6 | − | |

| C2 | PT | − | <15.6 | − |

| FHA | − | <15.6 | − | |

| PRN | − | <15.6 | − | |

V6 to V8 had been immunized with divalent PT-FHA vaccine 7 years earlier; C2 was a healthy adult control.

Tested by RT-PCR and scored as ++, +, and − (Fig. 2).

Cytokine proteins were measured by ELISA, and the threshold detection values of IFN-γ and IL-5 were 15.6 and 7.8 pg/ml, respectively. For IL-5 protein, levels were below the detection threshold in all subjects.

Relationship between humoral and cellular immune responses.

Immunization of the 17 schoolchildren with the DTaP vaccine induced significant IgG antibody responses to all three pertussis antigens (Table 5). Significant correlation was found between FHA-induced proliferative responses before immunization and anti-FHA IgG antibody levels after immunization (γ = 0.625, P = 0.007), as well as between FHA-induced proliferative responses and anti-FHA IgG antibodies after immunization (γ = 0.623, P = 0.008). Significant correlation was also found between anti-PRN IgG antibodies and PRN-induced proliferative responses after immunization (γ = 0.488, P = 0.047), whereas no correlation was found between proliferative and IgG antibody responses to PT.

TABLE 5.

Serum antibody responses in schoolchildren immunized with the DTaP vaccinea

| Time | Geometric mean ELISA units (95% confidence interval) of IgG antibodies to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PT | FHA | PRN | |

| Preimmunization | 12.9 (5.6–30.1) | 113.1 (59.2–215.8) | 38.2 (14.5–101.0) |

| Postimmunization | 213.5 (127.1–358.8)b | 1145.4 (845.4–2,471.2)b | 712.8 (380.9–1,333.8)b |

Seventeen 10- to 12-year-old children received a dose of the DTaP vaccine, and serum samples were tested before and 30 days after immunization.

P < 0.001 versus preimmunization values.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that in schoolchildren and adults, immunization with acellular pertussis vaccine and natural infection cause arousal of cellular immune functions as assessed by antigen-induced proliferation and cytokine mRNA expression of PBMCs. The mRNA transcripts for both Th1 type cytokines, IFN-γ and IL-2, and for Th2 type cytokines, IL-4 and IL-5, were detected in the PBMCs of the vaccinees and infected individuals after in vitro stimulation with B. pertussis antigens.

These findings are in agreement with the results of earlier studies on the immune responses of infants. Ausiello et al. (2) found that the induction of Th1 or Th2 cytokines is a vaccine- and antigen-dependent phenomenon after primary vaccination with either whole-cell or acellular vaccines. The acellular vaccine induced a basically type 1 cytokine profile, accompanied by some production of type 2 cytokines. Our acellular vaccine was the same as that used by Ausiello et al. Although the concentration of the antigens included in our vaccine had been reduced to one-third, the significant immune responses after the booster immunization were induced. Ryan et al. (34) studied preschool children with B. pertussis infection and demonstrated a preferential induction of Th1 cells. In our study, the PBMCs of five of the six patients with B. pertussis infection expressed mRNA for IFN-γ, a characteristic Th1 cytokine, after stimulation by at least one of the three antigens. The responses were not, however, restricted to the Th1 type, since transcripts of the IL-4 and/or IL-5 mRNA were also detected in the antigen-stimulated cells of these patients.

Our results show that IFN-γ mRNA was expressed at the protein level in the PBMCs stimulated with B. pertussis antigens, although the production of cytokine proteins was studied in a limited number of subjects. This finding further supports the concept that the expression of IFN-γ mRNA can be used as a parameter in assessing the type of immune response. The production of IL-5 mRNA was detected in the cells stimulated with B. pertussis antigens. However, the levels of IL-5 protein remained below the detection threshold of our assay. It is possible that the number of PBMCs which could be used for technological reasons still was too low for production of measurable concentrations of IL-5. Another reason might be that the 2-day culture was not optimal for the production of this particular cytokine.

In our study, the PBMCs of all tested subjects except the two infants expressed IL-2 mRNA after stimulation with pertussis antigens. Thus, some individuals expressed IL-2 but not IFN-γ. The IL-2 in these subjects could be derived from Th2 cells rather than Th1 cells. It has been shown that Th2 cells can produce small quantities of IL-2 (32). Because our cytokine RT-PCR is not a quantitative assay, IL-2 expression could not be used to differentiate the activities of Th1 and Th2 cells.

Whole-cell pertussis vaccines have been used extensively in most industrial countries where, despite high immunization rates, pertussis remains endemic and epidemic (6–8, 18, 40). Moreover, B. pertussis infection is increasingly recognized in older children and adults (5, 8, 19, 25, 26, 31), indicating the need of repeated booster immunizations in these age groups. Our results show, for the first time, that in schoolchildren the booster immunization with the trivalent acellular vaccine induced good responses in both arms of the immune system. The expression of cytokine mRNAs induced after the booster immunization was comparable to that induced after natural infection, suggesting that the acellular vaccine with reduced antigen concentration is suitable for the boostering in this population.

It is not fully known how long the protective immunity provided by pertussis vaccines persists. We have previously shown that Finnish children become susceptible to clinical pertussis after school entry (19), suggesting that the protection persists for about 5 years after the last immunization at 2 years of age. In this study, specific cellular responses to PT and FHA were not observed in one (V8) of three adults who had received a dose of bivalent vaccine (PT and FHA) 6 years before this testing. The significant responses of his cells to tetanus toxoid and mitogens excluded the possibility of a general unresponsiveness in this subject. This result suggests that cell-mediated immunity induced by pertussis immunization starts to decrease and may even become undetectable over 6 years.

Proliferative responses to PRN were more often found after immunization than after natural infection. Since the same antigens were used for immunization and for in vitro stimulation, good responses after immunization were to be expected. The lower responses after natural infection may be due to antigenic differences between the PRN of bacteria causing infections and the PRN used for in vitro stimulation. The selection pressure caused by the immunization program of more than 40 years may have changed the PRN of B. pertussis bacteria existing in the Finnish population. The preliminary results obtained by sequencing and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis indicate that most clinical isolates have differences in the gene encoding PRN compared to the vaccine strains (data not shown). On the other hand, the PRN used for immunizations had been treated with formaldehyde. This treatment may have destroyed some antigenic epitopes which are recognized by T cells induced during natural infection (10). However, we could not exclude the possibility that in some infected individuals, the blood samples were taken too early for any response to PRN to develop.

Our data clearly show that strong and specific cell-mediated immune responses are induced in schoolchildren and adults after B. pertussis infection or after booster immunization with an acellular vaccine containing reduced concentrations of PT, FHA, and PRN. Moreover, the expression of cytokine mRNAs induced after the booster immunization is comparable to that induced after natural infection. These results suggest that the acellular vaccine tested is suitable for the booster immunizations in these age groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Academy of Finland and the Finnish Foundation for Pediatric Research.

We thank Birgitta Aittanen and Tuula Lehtonen for excellent technical assistance and Erkki Nieminen for help in preparing the figures. The language of the manuscript was edited by Simo Merne.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ad Hoc Group for the Study of Pertussis Vaccines. Placebo-controlled trial of two acellular pertussis vaccines in Sweden: protective efficacy and adverse events. Lancet. 1988;i:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausiello C M, Urbani F, la Sala A, Lande R, Cassone A. Vaccine- and antigen-dependent type 1 and type 2 cytokine induction after primary vaccination of infants with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccine. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2168-2174.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bromberg K, Tannis G, Steiner P. Detection of Bordetella pertussis associated with the alveolar macrophages of children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4715–4719. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4715-4719.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caceres-Dittmar G, Tapia F J, Sanchez M A, Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Modlin R L, Bloom B R, Convit J. Determination of the cytokine profile in American cutaneous leishmaniasis using the polymerase chain reaction. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:500–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattaneo L A, Reed G W, Haase D H, Wills M J, Edwards K M. The seroepidemiology of Bordetella pertussis infections: a study of persons ages 1–65 years. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1256–1259. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis—United States, January 1992–June 1995. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1995;44:525–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry, J. D., P. A. Brunell, G. S. Golden, and D. T. Karzon. 1988. Report of the task force on pertussis and pertussis immunization—1988. Pediatrics 81(Suppl.):939–984.

- 8.Christie C D C, Marx M L, Marchant C D, Reising S F. The 1993 epidemic of pertussis in Cincinnati: resurgence of disease in a highly immunized population of children. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:16–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407073310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Magistris M T, Romano M, Nuti S, Rappuoli R, Tagliabue A. Dissecting human T cell responses against Bordetella species. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1351–1362. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Tommaso A, De Magistris M T, Bugnoli M, Marsili I, Rappuoli R, Abrignani S. Formaldehyde treatment of proteins can constrain presentation to T cells by limiting antigen processing. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1830–1834. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1830-1834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards K M, Decker M D. Acellular pertussis vaccines for infants. N Engl J Med. 1996;155:74–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards, K. M., B. D. Meade, M. D. Decker, G. F. Reed, M. B. Rennels, M. C. Steinhoff, E. L. Anderson, J. A. Englund, M. E. Pichichero, M. A. Deloria, and A. Deforest. 1995. Comparison of 13 acellular pertussis vaccines: overview and serologic response. Pediatrics 96(Suppl.):548–557. [PubMed]

- 13.Ewanowich C A, Melton A R, Weiss A A, Sherburne R K, Peppler M S. Invasion of HeLa 229 cells by virulent Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2698–2704. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2698-2704.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman R L, Nordensson K, Wilson L, Akporiaye E T, Yocum D E. Uptake and intracellular survival of Bordetella pertussis in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4578–4585. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4578-4585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gearing A J, Bird C R, Redhead K, Thomas M. Human cellular immune responses to Bordetella pertussis infection. FEMS Microbiol Immunol. 1989;1:205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greco D, Salmaso S, Mastrantonio P, Guiliano M, Tozzi A E, Anemona A, Ciofi Degli Atti M L, Giammanco A, Panei P, Blackwelder W C, Klein D L, Wassilak S G F the Progetto Pertosse Working Group. A controlled trial of two acellular vaccines and on whole-cell vaccine against pertussis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:341–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustafsson L, Hallander H O, Olin P, Reizenstein E, Storsaeter J. A controlled trial of a two-component acellular, a five-component acellular, and a whole-cell pertussis vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:349–355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Q, Schmidt-Schläpfer G, Just M, Matter H C, Nikkari S, Viljanen M K, Mertsola J. Impact of polymerase chain reaction on clinical pertussis research: Finnish and Swiss experiences. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1288–1295. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Q, Viljanen M K, Nikkari S, Lyytikainen R, Mertsola J. Outcomes of Bordetella pertussis infection in different age groups of an immunized population. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:873–877. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He Q, Viljanen M K, Ölander R-M, Bogaerts H, Grave D D, Ruuskanen O, Mertsola J. Antibodies to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis and protection against whooping cough in schoolchildren. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:705–708. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura A, Mountzouros K T, Relman D A, Falkow S, Cowell J L. Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin: evaluation as a protective antigen and colonization factor in a mouse respiratory infection model. Infect Immun. 1990;58:7–16. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.7-16.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung J C K, Lai C K W, Chui Y L, Ho R T H, Chan C H S, Lai K N. Characterization of cytokine gene expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after activation with phorbol myristate acetate and phytohaemagglutinin. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melby P C, Darnell B J, Tryon V V. Quantitative measurement of human cytokine gene expression by polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol Methods. 1993;159:235–244. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90162-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills K H, Barnard A, Watkins J, Redhead K. Cell-mediated immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of Th1 cells in bacterial clearance in a murine respiratory infection model. Infect Immun. 1993;61:399–410. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.399-410.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mink C M, Cherry J D, Christenson P, Lewis K, Pineda E, Shlian D, Dawson J A, Blumberg D A. A search for Bordetella pertussis infection in university students. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:464–471. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.2.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson J D. The changing epidemiology of pertussis in young infants: the role of adults as reservoirs of infection. Am J Dis Child. 1978;132:371–373. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120290043006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peppoloni S, Nencioni L, Di Tommaso A, Tagliabue A, Parronchi P, Romagnani S, Rappuoli R, De Magistris M T. Lymphokine secretion and cytotoxic activity of human CD4+ T-cell clones against Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3768–3773. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3768-3773.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen J W, Andersen P, Ibsen P H, Capiau C, Wachmann C H, Haslov K, Heron I. Proliferative responses to purified and fractionated Bordetella pertussis antigens in mice immunized with whole-cell pertussis vaccine. Vaccine. 1993;11:463–472. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90289-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podda A, Nencioni L, De Magistris T, Di Dommaso A, Bossu P, Nuti S, Pileri P, Peppoloni S, Bugnoli M, Ruggiero P, Marsili I, D’Errico A, Tagliabue A, Rappuoli R. Metabolic, humoral, and cellular responses in adult volunteers immunized with the genetically inactivated pertussis toxin mutant PT-9K/129G. J Exp Med. 1990;172:861–868. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redhead K, Watkins J, Barhard A, Mills K H G. Effective immunization against Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in mice is dependent on induction of cell-mediated immunity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3190–3198. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3190-3198.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson P W, Goldberg H, Jarvie B H, Smith D D, Whybin L R. Bordetella pertussis infection: a cause of persistent cough in adults. Med J Aust. 1987;147:522–525. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1987.tb120392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romagnani S. Biology of human Th1 and Th2 cells. J Clin Immunol. 1995;15:121–129. doi: 10.1007/BF01543103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruuskanen O, Noel A, Putto-Laurila A, Petre J, Capiau C, Delem A, Vandevoorde D, Simoen E, Teuwen D E, Bogaerts H, Andre F E. Development of an acellular pertussis vaccine and its administration as a booster in healthy adults. Vaccine. 1991;9:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90267-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan M, Murphy G, Gothefors L, Nilsson L, Storsaeter J, Mills K H G. Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in children is associated with preferential activation of type 1 T helper cells. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1246–1250. doi: 10.1086/593682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato H, Sato Y. Bordetella pertussis infection in mice: correlation of specific antibodies against two antigens, pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin, with mouse protectivity in an intracerebral or aerosol challenge system. Infect Immun. 1984;46:415–421. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.415-421.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saukkonen K, Cabellos C, Burroughs M, Prasad S, Tuomanen E. Integrin-mediated localization of Bordetella pertussis within macrophages: role in pulmonary colonization. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1143–1149. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahin, R. D., M. J. Brennan, Z. M. Li, B. D. Meade, and C. R. Manclark. Characterization of the protective capacity and immunogenicity of the 69 KD outer membrane protein of Bordetella pertussis. J. Exp. Med. 171:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Tanaka J, Imamura M, Kasai N, Masauzi N, Matsuura A, Ohizumi H, Morii K, Kiyama Y, Naohara T, Saitho M, Higa T, Honke K, Gasa S, Sakurada K, Miyazaki T. Cytokine gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells during graft-verse-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomoda T, Ogura H, Kurashige T. Immune responses to Bordetella pertussis infection and vaccination. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:559–563. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wortis N, Strebel P M, Wharton M, Bardenheier B, Hardy I R B. Pertussis deaths: report of 23 cases in the United States, 1992 and 1993. Pediatrics. 1996;97:607–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zepp F, Knuf M, Habermehl P, Schmitt H J, Rebsch C, Schmidtke P, Clemens R, Slaoui M. Pertussis-specific cell-mediated immunity in infants after vaccination with a tricomponent acellular pertussis vaccine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4078–4084. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4078-4084.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]