Abstract

Background:

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) catalyzes the trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 via the polycomb recessive complex 2 (PRC2) and plays a time-specific role in normal fetal liver development. EZH2 is overexpressed in hepatoblastoma (HB), an embryonal tumor. EZH2 can also promote tumorigenesis via a non-canonical, PRC2-independent mechanism via proto-oncogenic, direct protein interaction, including β-catenin. We hypothesize that pathological activation of EZH2 contributes to HB propagation in a PRC2-independent manner.

Methods and Results:

We demonstrate that EZH2 promotes proliferation in HB tumor-derived cell lines through interaction with β-catenin. While aberrant EZH2 expression occurs, we determine that both canonical and noncanonical EZH2 signaling occurs based on specific gene expression patterns and interaction with SUZ12, a PRC2 component, and β-catenin. Silencing and inhibition of EZH2 reduces primary HB cell proliferation.

Conclusions:

EZH2 overexpression promotes HB cell proliferation, with both canonical and noncanonical function detected. However, because EZH2 directly interacts with β-catenin in human tumor and EZH2 overexpression is not equal to SUZ12, it seems that a noncanonical mechanism is contributing to HB pathogenesis. Further mechanistic studies are necessary to elucidate potential pathogenic downstream mechanisms and translational potential of EZH2 inhibitors for treatment of HB.

Keywords: HB tumor-derived cell line, organoid, β-catenin, PRC2

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Hepatoblastoma (HB) is the most common pediatric liver malignancy worldwide1,2. HB belongs to a subset of pediatric solid tumors termed “embryonal” as these neoplasms arise from precursor cell populations that have not reached terminal differentiation 3-9. Also, HB is unique as it manifests very few genomic mutations; the only ubiquitous mutations occur in CTNNB1 with one study demonstrating 87% of tumors harboring these mutations.

Prior single-cell nuclear RNA-seq analysis (snRNAseq) identified significant overexpression of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in human HB tumors 10. Specifically, pronounced EZH2 overexpression was detected in an HB tumor cell subpopulation, labelled Tr2 and characterized by a strong mitotic and DNA replication signature. EZH2 is of specific interest in embryonal tumorigenesis due to its role in the expansion and proliferation of both human pluripotent stem cell-derived, hepatocyte-like, and murine derived fetal liver cells 11-14. Another tumor cell subcluster, Tr0, has a gene signature consistent with a hepatic precursor cell, which gives rise to the Tr2 population, indicating a transition from a stem-like precursor to a cell with a potentially malignant phenotype. Additional snRNA-seq data from human fetal liver at chronological gestational ages demonstrated a window of EZH2 overexpression from weeks 12 to 14, indicating a temporally dependent role for EZH2 activation in normal human liver development 15.

Canonical EZH2 represses gene transactivation as the catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) which trimethylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) 16,17. The PRC2.1 complex, composed of EZH2, SUZ12, and EED, can also directly interact with numerous other proteins and demonstrate aberrant activity in malignancy18-20. “Noncanonical” EZH2 alternatively may directly interact with other proteins to promote transcriptional activation, independent of PRC2 21. Canonical EZH2 downregulates β-catenin repressors, thereby promoting hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell proliferation 22-25. However, EZH2 can also directly interact with β-catenin to form a protein complex in other epithelial cancers 26-29. Interestingly, simultaneous inhibition of the canonical and noncanonical functions of EZH2 in leukemia demonstrated a potent antineoplastic effect, indicating that both functions can play a role in cancer 30.

Prior studies have implicated EZH2 in HB pathogenesis by demonstrating that shRNA-mediated inhibition of EZH2 limits the proliferation of HB cell lines Huh-6 and HepG2 10,31. Additionally, one of the subunits of PRC2.1, SUZ12, has been identified by Cairo et al. in more clinically aggressive HB 32. Although EZH2 has been reported to play a role in HB pathogenesis in vitro and indicate clinical aggressiveness, no mechanism has been identified 31,33,34. Our investigations describe the role of aberrant EZH2 expression in HB tumor proliferation and explore the possible direct interaction with β-catenin in this process.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples

HB tumors (T) and associated adjacent background liver tissue (B) were obtained with IRB approval (2016-9497) and informed patient (parent or guardian) consent was obtained to conduct molecular and mechanistic studies of hepatoblastoma and to generate tumor models for molecular evaluation and drug studies. Tumors were utilized to determine gene and protein expression patterns and to develop HB tumor-derived cell lines. Thirty-five paired T and B patient samples were utilized in these experiments (Supplemental table 1). For clarity, tumor specimens are annotated as “HB” followed by a deidentified number.

Cell culture

HB tumor-derived cell lines (HBc30, HBc45, HBc60, HBc74, and HBc81) were generated from patient tumors from respective established patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models using basic explant culture 35,36 (Supplemental table 2). PDX models were established with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval (IACUC # 2022-0069) and following the criteria defined by the “Guide for the Care and Use for Laboratory Animals”, as described previously 37. PDX tumors were utilized to create cell lines.

Experiments were conducted in vitro in monolayer cultures from these cell lines and the established liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Huh6 for up to 12 passages. HB-derived cells were validated using bulk RNA sequencing and compared with human hepatocytes (Lonza), human dermal fibroblasts (Lonza), and HepG2 cells (ATCC). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 20 μM Rho kinase inhibitor, Y27632, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cultures tested negative for mycoplasma using the Mycoalert detection kit from Lonza.

For organoid cultures, 200 cells/microwell were seeded into Aggrewell 400, 24 well dishes (Stemcell technologies). siEZH2 organoids were incubated for 48 hours to observe aggregation and tumor formation, fixed with 4% PFA, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

Cell proliferation

Cultured cells were plated in 96-well dishes and serum-starved for 6 hours prior to treatment with siRNA or inhibitors, as described above. For cell proliferation assays, WST-1 Cell Proliferation reagent was added at a concentration of 1:10 and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Takara Bio Inc.). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Synergy HI microplate reader (BioTek).

Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was performed on paraffin sections for H&E, Ki67 (MA5-14520, 1:300; Thermo Fisher), CTNNB1 (β-catenin- Roche 760-4242, 1:200), and EZH2 (3147, 1:200; Cell Signaling). Tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and the antibody was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-containing 2% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20. Tissue sections were incubated with antibody overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS+0.05% tween 20, then visualized with Vectastain elite ABC HRP (vector labs) per protocol instructions. Immunofluorescence (IF) was performed on the cells in vitro cultured on chamber slides. Cells were washed with 1x PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature (EZH2 3147, 1:200, Cell Signaling, H3K27me3 9733, 1:1000, Cell Signaling, GPC3 ab207080, 1:200, Abcam). IHC staining was performed using the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Pathology Core. Serial sections were imaged and indicated in figure legends.

Real Time PCR and Western Blot Analysis

Transcriptional gene expression analysis was performed by quantitative real-time PCR, and comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCt) values were normalized to GAPDH. Relative values were normalized to the expression levels of the averaged background liver samples or control treated cells, as previously described 38. Briefly, the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit from Qiagen, VILO cDNA synthesis kit from Invitrogen, and RT2 SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen) were used. Reactions were run in a CFX Connect real-time thermocycler (Bio-Rad). RT2 Primers from Qiagen were used and are listed in supplemental table 3. Each biological sample was run in triplicate.

Protein analysis was evaluated by western blot as previously described 38. Samples were lysed with Mammalian Cell Lysis Kit (Sigma Aldrich) and run on 4-20% gradient polyacrylamide gels using a Bio-Rad system, transferred to 0.45μm nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted for respective antibodies. Antibodies are listed in supplemental table 3.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) was performed using Pierce Crosslink Magnetic IP/Co-IP Kit (Thermo, 88805) following the manufacturer’s protocol to reduce the detection of IgG. 100μg of protein was used for IP, pre-cleared, and run on western blot. EZH2 was pulled down using Cell Signaling, 5246 rabbit monoclonal antibody, blotted as described above, and detected for EZH2, SUZ12, and β-catenin, as listed in supplemental table 3.

Bulk RNA Sequencing

Bulk RNA sequencing was performed as described previously 10. The Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini Kit was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Tumor-derived cell lines HepG2 cells, human hepatocytes (HH) and human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) were used for this analysis.

150 to 300 ng of total RNA as determined by Qubit (Invitrogen) measurement was poly A selected and reverse transcribed. RNAseq libraries were prepared using TruSeq polyA-stranded library preps from Illumina and sequenced with paired-ends, with 100bp parameters on the NovaSeq 6000 instrument. Quality control evaluation of the FASTQ files was performed using FastQC. Sequencing was performed by the CCHMC DNA Sequencing and Genotyping Core.

Following removal of primers and barcodes, raw reads were processed using kallisto (Pachter lab), which uses pseudoalignment to accurately quantify RNA reads with transcripts per million (TPM) as output. GRCh38/Hg38 annotations were provided by UCSC. Prior to analysis, the data were log2-transformed and baselined to the overall median. Only reasonably expressed transcripts (TPM>3 in >20% of samples) were included in differential analyses, where significance was set at p<0.05 and FC>2. Ontological analyses of differentially expressed transcripts were performed using ToppGene and ToppCluster suites.

siRNA

All experiments were performed in triplicate using HB30, HB74, and HB81 cells and HepG2 cells. Cells were plated in 6 well dishes at 15-20,000 cells/cm2, grown to 70-80% confluence, and serum-starved in DMEM + 1% FBS + 1% NEAA for 6 hours. EZH2 was silenced using silencer select siRNA and Lipofectamine RNAimax, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). The final concentration of siEZH2 was 100pmol in the control samples using nonsense siRNA (Invitrogen). The cells were cultured for 48 hours post-treatment and harvested for analysis.

EZH2 inhibitors

Cells grown as described for the siRNA experiments were treated with GSK126 and EPZ-6438 (Tazemetostat), which are S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) competitive inhibitors. SAM is known to be involved in methylation reactions in biological systems. 3-deazaneplanocin (DZNep) is an inhibitor of S-adenosylhomocysteine, an indirect competitive inhibitor of EZH2, through DNA methyltransferase activity. Concentrations ranging from 1μM to 100μM of these inhibitors were used in vitro for up to 72 hours following culturing and serum starvation, as described above, to determine their potential in reducing proliferation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-tests or ANOVA to evaluate normally distributed data with multiple comparisons using GraphPad Prism 9.3.1. Error bars in each figure represent mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Significance is indicated in the figures and associated legends with exact p-values indicated.

Data availability

Sequencing data that support the findings in this study have been assigned Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession number GSE235202; figure 3 and supplemental figure 2 contain bulk RNA sequencing data with associated GEO files.

Figure 3.

Patient-derived HB cell lines recapitulate HB in vitro. A. Growth and morphological evaluation of cell lines, HBc30, 74, and 81, compared to HepG2 (20X, scale bar 100 μm). B. Bulk RNAseq gene transcripts per million to show GPC3 tumor marker expression in HB cell lines (HBc30, 60, 74, 81) compared to human dermal fibroblasts (HDF), human hepatocytes (HH), and HepG2 cells. C. Heat maps of hierarchical clustering for differentially expressed genes show enhanced expression of Wnt signaling in HB cells, overexpression of tumor suppressors that are known oncogenes, and elevated EZH2 with patterns outside traditional canonical signaling, including PRC2 components (MYC is downregulated and SUZ12 and EED expression does not align with EZH2 expression). Fibroblasts and hepatocytes from Lonza were used as controls.

Results

EZH2 is overexpressed in human HB tumor

HB tumors overexpressed EZH2 and β-catenin RNA compared to background liver in a subset of 35 paired patient tumors and adjacent background liver samples (Figure 1.A). EZH2 is not uniformly expressed within tumor homogenates which may result from EZH2 overexpression being most prominent in the Tr2 subpopulation 10. To further characterize EZH2 gene expression, additional PRC2 complex genes were evaluated (Figure 1.A). Tumors demonstrated SUZ12 overexpression, but EED was not elevated compared to background liver. Other genes of interest, including Lef1, Ki67, Axin2, and Jarid2, were also elevated in tumor compared to background liver. Additional genes were evaluated including HB tumor markers, AFP and GPC3, as well as other genes of interest related to EZH2 (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

EZH2 overexpression correlates with β-catenin and Ki67 in HB tumor. A. Gene expression in tumor shows overexpression in EZH2, SUZ12, Jarid2, β-catenin, Lef1, Axin2, and Ki67. B. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) shows H&E with more nuclei and an embryonal with some fetal pattern in tumor (T) and more organized background liver (B) with parenchymal and stromal areas with organized hepatocytes, as well as elevated Ki67 (proliferation marker), EZH2 and β-catenin staining in HB T compared to B in two representative patient samples (ki67- MA5-14520, EZH2- 3147, β-catenin - 760-4242) 40x objective Nikon Ti. C. Representative protein expression from three patients shows EZH2, β-catenin, and SUZ12 with GAPDH as a loading control, to show differences between B and T (β-catenin shows full length 92kD and smaller band in tumor, in line with possible mutation).

Nuclear prominence of EZH2 and β-catenin was observed in serial tumor sections on IHC staining. Furthermore, increased Ki67 staining correlated with these histological findings (Figure 1.B). To determine whether gene overexpression correlated with protein expression, we examined protein concentrations from human tumors and demonstrated that EZH2 and SUZ12 concentrations were elevated in HB tumors (Figure 1.C.). Taken together EZH2 overexpression correlates with Ki67 and β-catenin, supporting further examination of the roles of these molecules in HB.

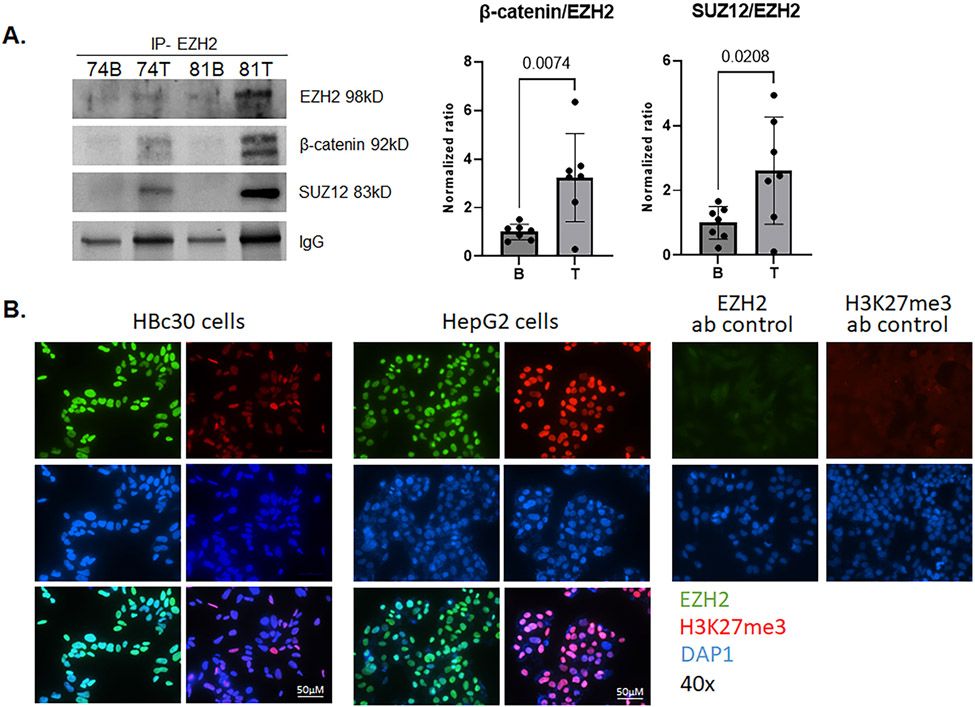

EZH2 interacts with SUZ12 and β-catenin independent of H3K27me3 trimethylation

To determine the mechanism by which EZH2 overexpression contributes to HB development, we examined EZH2-related protein interactions in human HB tumors. Specifically, to explore whether canonical or noncanonical EZH2 activity occurs in HB, we performed co-immunoprecipitation of EZH2 with SUZ12, a member of the PRC2 complex, as well as with β-catenin. EZH2 and SUZ12 had an overall greater interaction in tumors compared to background (Figure 2.A). Similarly, though, a greater interaction between EZH2 and β-catenin in tumor was observed (Figure 2.A).

Figure 2.

Molecular interactions of EZH2 in HB. A. EZH2 was co-immunoprecipitated from T and B from seven patients and immunoblotted for EZH2, β-catenin, and SUZ12. EZH2 has greater affinity for β-catenin and SUZ12 in HB T than B (representative blot shown). The ratio of capture (EZH2) to bait (β-catenin or SUZ12) is shown graphically. IP with EZH2 (5246, rabbit), and blotted with EZH2 (3147, mouse), β-catenin (2698, mouse), and SUZ12 (3737, rabbit) antibodies (1:1000). B. Immunofluorescence of EZH2 (3147, mouse, AF488) and H3K27me3 (9733, rabbit, AF594) in HBc30 cells and HepG2 cells with nuclear staining (DAPI) shows prominent EZH2 nuclear staining with lower expression of H3K27me3 in HB cells compared to HepG2. Negative control staining for EZH2 and H3K27me3 are also shown (40x objective Nikon Ti).

To clarify these results, we evaluated H3K27 trimethylation as a marker of PRC2-dependent EZH2 function. EZH2 protein overexpression occurs in HB cell lines as well as the established HB cell line HepG2, but there is much less H3K27me3 trimethylation in HB cell lines than in HepG2 cells (Figure 2.B).

HB derived cell lines as a disease model for HB

Four HB-derived cell lines (HBc30, HBc60, HBc74, and HBc81) were derived from previously created PDXs and compared to HepG2 cells, Huh6 cells, human hepatocytes, and human dermal fibroblasts. Protein overexpression of EZH2 and β-catenin was observed in these cells (Supplemental figure 2.A). HepG2 cells are reported to have a large exon 3 deletion and Huh6 cells have a point mutation in CTNNB1 39.

Using principal component analysis, all primary tumor cell lines clustered with HepG2 (Supplemental figure 2.B). Overall gene signature showed similarity between all HB tumor-derived cells while some differences were noted between HepG2 cells and the more fibroblast-like HBc60 cells in comparison to HBc30, HBc74, HBc81 (Supplemental figure 2.C). Gene expression in these cell lines is more consistent with a hepatocyte-derived tumor cell signature, whereas HBc60 possesses features of tumor-associated fibroblasts (Supplemental figure 2.D).

Therefore, our studies focused on HBc30, HBc74, HBc81, and HepG2 cells (Figure 3.A). Of the three cell lines utilized in our study, two were derived from primary tumor samples from the liver and one was derived from a pulmonary metastasis (Supplemental table 2). To characterize these cell lines as models of HB, transcript levels of GPC3, a known marker of HB, were assayed and found to be elevated in these cell lines as well as in HepG2 cells in comparison to human hepatocytes and fibroblasts. HBc60 demonstrated GPC3 overexpression, but not to the same degree as the others (Figure 3.B). Additionally, GPC3 was visualized by IF in HB derived cells and HepG2 cells to show predominantly GPC3 positive tumor cells in derived cell populations (Supplemental Figure 3).

Bulk RNA-seq gene expression profiles from HBc30, HBc74, and HBc81 cells for pathways related to Wnt, EZH2, and tumor suppressor signaling are presented in Figure 3.C. Tumor cells demonstrate Wnt activation/overexpression with some intertumoral variability. Wnt signaling and EZH2 were elevated but the canonical PRC2 genes SUZ12 and EED were not. Canonical/histone methyltransferase PRC2 activity has been demonstrated to require EZH2, SUZ12, and EED, further indicating a non-canonical tumorigenic mechanism 40. MYC, a downstream indirect target of PRC2 activity, was downregulated, although interaction is still possible, given the overexpression of EZH2 (Figure 3.C). Finally, overexpression of tumor suppressors, specifically PTEN, TP53, SORBS2/ARGBP2, and CDKN2A, in this data set is not consistent with other malignancies where pathologic PRC2 function results in suppression of these genes 41-44.

Silencing EZH2 expression in HB cell lines and organoids

EZH2 gene expression was effectively reduced in all cell lines compared to the vehicle control via transfection with siRNA (Figure 4.A). To corroborate the relationship of EZH2 and canonical Wnt signaling as necessary for HB proliferation, we evaluated the gene expression of Lef1, a downstream target of Wnt/β-catenin. Lef1 expression was significantly reduced in HB-derived cells but not HepG2 cells. Ki67 gene expression, previously demonstrated to be elevated in human HB (Figure 1.A), was reduced in HBc30 and HBc81. Reduction of protein expression was variable across the cell lines, with the most effective reduction of EZH2 protein expression observed in HBc30 and HBc81 (Figure 4.B). β-catenin was also modestly reduced when EZH2 expression was silenced but SUZ12 was unchanged.

Figure 4.

Silencing gene expression using siEZH2 results in reduced proliferation and tumorgenicity. EZH2 silencer select siRNA reduces EZH2 gene and protein expression at 100 pmol concentration. A. Gene expression of EZH2, Lef1, and Ki67 are reduced following EZH2 silencing in HB cells, but increased Lef1 and Ki67 are seen in HepG2 cells. B. EZH2 protein is reduced 48 hours after siEZH2 transfection with moderate change in β-catenin. (EZH2- 3147, β-catenin - 8480, GAPDH- 10R-G109a, qRT-PCR primers from Qiagen RT2 assay #330001). C. Cell proliferation is reduced in HB cell lines with reduced EZH2 protein following siEZH2, representative cell images are shown for control and siEZH2 treatment (10X, Nikon Ts2). D. Two HB cell lines show reduced cell aggregation into organoids following EZH2 gene silencing by siRNA. HB control cells form organoids, but siEZH2 treated cells show less cell aggregation and clustering (organoid in aggrewell and H&E staining 10x, 40x). EZH2 gene expression is greatly reduced in siEZH2 condition as determined by qRT-PCR.

We found that proliferation was reduced in HB cell lines with effective EZH2 protein reduction (Figure 4.C). To further understand the role of EZH2 in tumor generation, we transfected two HB cell lines with siRNA against EZH2 and cultured cells in aggrewell 400 plates. These clusters were fixed and stained with H&E (Figure 4.D). Following EZH2 silencing, HB cell organoids showed less tumor cell aggregation than control cells, with smaller cell clusters observed due to reduced cell adhesion.

EZH2 inhibition differentially reduces cell proliferation in vitro

In vitro drug studies were performed to evaluate the therapeutic potential of targeting EZH2 using commercially available inhibitors. Tazemetostat and GSK126 are potent, direct EZH2 inhibitors currently FDA-approved for the treatment of follicular lymphoma and advanced epithelioid sarcoma 45,46. DZNep, an S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine (SAH) hydrolase inhibitor, causes cell death in some cancers47. HepG2, Huh6, and HB cells were treated with increasing doses of EZH2 inhibitors for 72 hours. DZNep of 1μM, generally demonstrated a modest reduction in EZH2 protein. No additional protein changes were observed following treatment with Tazemetostat or GSK126 (Figure 5.A).

Figure 5.

EZH2 inhibition reduces proliferation in a dose dependent manner. A. Western blot of samples treated with 1μM of inhibitors (to ensure adequate protein yield) for 72 hours shows reduced EZH2 after 3-deazaneplanocin treatment (EZH2- 3147, β-catenin-8480, SUZ12- 3737, GAPDH- 10R-G109a). No change in protein was seen following Tazemetostat (EPZ-6438, Taze) and GSK-126 treatment. B. All cell lines were treated with 1 and 10μM concentrations of EZH2 inhibitors (Tazemetostat, GSK-126,3-deazaneplanocin) for 72 hours and proliferation was measured by WST-1 assay. Reduced proliferation and cell death were observed in all cell lines, except HepG2, with Tazemetostat and GSK-126, but not 3-deazaneplanocin. GSK-126 elicited a more prominent reduction in proliferation. C. Representative cell images are shown to demonstrate growth and morphologic differences between treatment groups at 72 hours post-treatment. Again, GSK-126 shows the greatest change following treatment (20x objective, Nikon Ts2).

Cell proliferation was reduced by Tazemetostat and GSK126 in a dose-dependent manner. Cell death was also observed in response to Tazemetostat and GSK126 starting at a concentration of 10 μM (Figure 5.B). DZNep elicited minimal response though HepG2 cells demonstrated a modest increase in proliferation. DZNep’s mechanism of action results in increased concentration of SAH which negatively feeds back on S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent histone methyltransferase. DZNep does not specifically inhibit EZH2; rather it inhibits all cellular methyltransferases which may result in off target effects that may explain the lack of primary tumor cell response 48.

Reduced growth and morphologic changes were also observed microscopically at 72 hours post-treatment, with the greatest observed difference in GSK126 treated cells (Figure 5.C). A dose dependent, reduction in growth after 24 hours was also observed at 25 and 100μM treatments with profound cell death at 100 μM (Supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

Previous studies proposed a role for EZH2 in HB pathogenesis using the Huh6 and HepG2 cell lines 49-51,48-50. The current study expands on these data by demonstrating that EZH2 gene and protein expression are elevated in human hepatoblastoma tumors as well as in primary tumor cell lines. Our data suggests, however, that elevated levels of EZH2 may vary from specimen to specimen. While this finding may be explained by clinical sampling variability, it may also be consistent with our previous finding that EZH2 expression is mostly limited to the Tr2 cell subcluster. Using scRNAseq, other groups have also postulated that HB consists of multiple genomically-unique cell populations 10,52,53,10,51,52. Therefore, isolation and characterization of these cell subclusters will become important to understand tumor development, evolution, self-renewal, and metastasis, to target the HB patients most in need of novel therapies. Indeed, in a clinical study, elevated serum EZH2 may be related to more aggressive disease 33,34.

Our data demonstrates that EZH2 co-immunoprecipitates with both SUZ12 and β-catenin, but the level of EZH2 protein expression does not equal protein level of SUZ12, a PRC2 cofactor. Additionally, H3K27me3 protein level is not elevated in human tumor. These findings suggest that EZH2 operates in a predominantly non-canonical manner because canonical EZH2 interacts with and requires EED and SUZ12 16. The stoichiometry of the PRC2 complex requires correspondingly elevated protein levels of EED and SUZ12 54,53. Non-canonical mechanisms of EZH2 function as they relate to β-catenin function have been reported. A recent study demonstrated that EZH2 and SUZ12 are able to bind to the Wnt2 promoter region which, when activated, transactivated downstream β-catenin55. It is also possible that direct interaction between EZH2 and β-catenin plays a role in HB tumorigenesis as it does in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 46. Given that EZH2 and β-catenin play a prominent role in fetal liver development, it is logical that some perturbation of this normal process can lead to cancer development. Considering the embryonal nature of HB tumors, abnormal regulation of normal liver development may represent a target for future preclinical studies of alternative HB chemotherapies.

Downregulation of EZH2 via both pharmacologic inhibitors and siRNA-mediated silencing results in cytostatic and cytotoxic tumor impairment in vitro including reduction of proliferation, impaired cell aggregation, and enhanced cell death in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, cells treated with DZNep demonstrated minimal response which may be explained by its mechanism of action. DZNep does not specifically inhibit EZH2; rather it inhibits all cellular methyltransferases by increasing the concentration of SAH which negatively feeds back on S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent histone methyltransferase. This global methyltransferase inhibition may result in off target effects that may explain lack of primary tumor cell response. Currently, tazemetostat can be used to treat metastatic or locally advanced epitheloid sarcoma in patients aged 16 years or older as well as for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma that is EZH2 mutation-positive or for salvage. One National Cancer Institute-sponsored phase II trial is currently enrolling pediatric patients with relapsed or refractory advanced solid tumor, including HB, where tazemetostat is a therapeutic option in the context of an EZH2 mutation (NCT03155620). Yet, while there is a robust body of pre-clinical literature reporting EZH2 inhibition in solid malignancies including HCC, focused studies on the role of EZH2 in HB are warranted 56.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the CCHMC DNA sequencing and genotyping core and the Research pathology core for facilities, technical expertise, and support. This work was supported by NIH grant P30 DK078392 (Research pathology and DNA sequencing and genotyping core) of the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center in Cincinnati. Paperpal preflight was used to review manuscript pre-submission.

Abbreviations

- AFP

Alpha fetoprotein

- B

adjacent background liver tissue

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- DZNep

3-deazaneplanocin

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GPC3

Glypican 3

- H3K27me3

histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation

- HB

Hepatoblastoma

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HDF

Human dermal fibroblasts

- HH

Human hepatocytes

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PDX

Patient-derived xenograft

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- SAM

S-adenosyl methionine

- snRNAseq

single-cell nuclear RNA-seq analysis

- Taze

Tazemetostat, EPZ-6438

- T

HB tumor

- TPM

transcripts per million

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1.Hubbard AK, Spector LG, Fortuna G, Marcotte EL, Poynter JN. Trends in international incidence of pediatric cancers in children under 5 years of age: 1988–2012. JNCI cancer spectrum. 2019;3(1):pkz007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson DC, Meyers RL. Malignant tumors of the liver in children. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2016;25(5):265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López-Terrada D, Alaggio R, de Dávila MT, et al. Towards an international pediatric liver tumor consensus classification: proceedings of the Los Angeles COG liver tumors symposium. Modern Pathology. 2014;27(3):472–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairo S, Wang Y, de Reyniès A, et al. Stem cell-like micro-RNA signature driven by Myc in aggressive liver cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(47):20471–20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumazin P, Chen Y, Trevino LR, et al. Genomic analysis of hepatoblastoma identifies distinct molecular and prognostic subgroups. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):104–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooks KB, Audoux J, Fazli H, et al. New insights into diagnosis and therapeutic options for proliferative hepatoblastoma. Hepatology. 2018;68(1):89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrillo-Reixach J, Torrens L, Simon-Coma M, et al. Epigenetic footprint enables molecular risk stratification of hepatoblastoma with clinical implications. J Hepatol. 2020;73(2):328–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekiguchi M, Seki M, Kawai T, et al. Integrated multiomics analysis of hepatoblastoma unravels its heterogeneity and provides novel druggable targets. npj Precision Oncology. 2020;4(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagae G, Yamamoto S, Fujita M, et al. Genetic and epigenetic basis of hepatoblastoma diversity. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondoc A, Glaser K, Jin K, et al. Identification of distinct tumor cell populations and key genetic mechanisms through single cell sequencing in hepatoblastoma. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki R, Chiba T, Miyagi S, et al. The polycomb group gene product Ezh2 regulates proliferation and differentiation of murine hepatic stem/progenitor cells. J Hepatol. 2010;52(6):854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koike H, Ouchi R, Ueno Y, et al. Polycomb group protein Ezh2 regulates hepatic progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in murine embryonic liver. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pistoni M, Helsen N, Vanhove J, et al. Dynamic regulation of EZH2 from HPSc to hepatocyte-like cell fate. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0186884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B, Liu Y, Liao Z, Wu H, Zhang B, Zhang L. EZH2 in hepatocellular carcinoma: progression, immunity, and potential targeting therapies. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2023;12(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Yang L, Wang YC, et al. Comparative analysis of cell lineage differentiation during hepatogenesis in humans and mice at the single-cell transcriptome level. Cell Res. 2020;30(12):1109–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackledge NP, Klose RJ. The molecular principles of gene regulation by Polycomb repressive complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(12):815–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer S, Weber LM, Liefke R. Evolutionary adaptation of the Polycomb repressive complex 2. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2022;15(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laugesen A, Hojfeldt JW, Helin K. Role of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) in Transcriptional Regulation and Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomassi S, Romanelli A, Zwergel C, Valente S, Mai A. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Modulation through the Development of EZH2-EED Interaction Inhibitors and EED Binders. J Med Chem. 2021;64(16):11774–11797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi Y, Wang XX, Zhuang YW, Jiang Y, Melcher K, Xu HE. Structure of the PRC2 complex and application to drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38(7):963–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang J, Gou H, Yao J, et al. The noncanonical role of EZH2 in cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(4):1376–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang W, Shi C, Hong W, et al. Super-enhancer-driven lncRNA-DAW promotes liver cancer cell proliferation through activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;26:1351–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng AS, Lau SS, Chen Y, et al. EZH2-mediated concordant repression of Wnt antagonists promotes β-catenin-dependent hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(11):4028–4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei A, Chen L, Zhang M, et al. EZH2 Regulates Protein Stability via Recruiting USP7 to Mediate Neuronal Gene Expression in Cancer Cells. Front Genet. 2019;10:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi B, Liang J, Yang X, et al. Integration of estrogen and Wnt signaling circuits by the polycomb group protein EZH2 in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(14):5105–5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung HY, Jun S, Lee M, et al. PAF and EZH2 induce Wnt/β-catenin signaling hyperactivation. Mol Cell. 2013;52(2):193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X, Shao F, Guo D, et al. WNT/β-catenin-suppressed FTO expression increases m(6)A of c-Myc mRNA to promote tumor cell glycolysis and tumorigenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(5):462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Gonzalez ME, Toy K, Filzen T, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Targeted overexpression of EZH2 in the mammary gland disrupts ductal morphogenesis and causes epithelial hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(3):1246–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedley S, Nag JK, Rudina T, Bar-Shavit R. PAR-Induced Harnessing of EZH2 to beta-Catenin: Implications for Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Yu X, Gong W, et al. EZH2 noncanonically binds cMyc and p300 through a cryptic transactivation domain to mediate gene activation and promote oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24(3):384–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Xiao Y, Chen K, et al. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 depletion arrests the proliferation of hepatoblastoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13(3):2724–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cairo S, Armengol C, De Reynies A, et al. Hepatic stem-like phenotype and interplay of Wnt/beta-catenin and Myc signaling in aggressive childhood liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(6):471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hajósi-Kalcakosz S, Dezső K, Bugyik E, et al. Enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) is a reliable immunohistochemical marker to differentiate malignant and benign hepatic tumors. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlachter K, Gyugos M, Halász J, et al. High tricellulin expression is associated with better survival in human hepatoblastoma. Histopathology. 2014;65(5):631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bissig-Choisat B, Kettlun-Leyton C, Legras XD, et al. Novel patient-derived xenograft and cell line models for therapeutic testing of pediatric liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2016;65(2):325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kats D, Ricker CA, Berlow NE, et al. Volasertib preclinical activity in high-risk hepatoblastoma. Oncotarget. 2019;10(60):6403–6417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valanejad L, Cast A, Wright M, et al. PARP1 activation increases expression of modified tumor suppressors and pathways underlying development of aggressive hepatoblastoma. Commun Biol. 2018;1:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schepers EJ, Lake C, Glaser K, Bondoc AJ. Inhibition of Glypican-3 Cleavage Results in Reduced Cell Proliferation in a Liver Cancer Cell Line. J Surg Res. 2023;282:118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Masi A, Viganotti M, Antoccia A, et al. Characterization of HuH6, Hep3B, HepG2 and HLE liver cancer cell lines by WNT/beta - catenin pathway, microRNA expression and protein expression profile. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2010;56 Suppl:OL1299–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao R, Zhang Y. SUZ12 is required for both the histone methyltransferase activity and the silencing function of the EED-EZH2 complex. Mol Cell. 2004;15(1):57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu L, Qu Y, An Y, et al. Induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype underlies the therapeutic efficacy of PRC2 inhibition in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(2):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang R, Wang M, Zhang G, et al. E2F7-EZH2 axis regulates PTEN/AKT/mTOR signalling and glioblastoma progression. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1445–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Q, Zheng P-S, Yang W-T. EZH2-mediated repression of GSK-3β and TP53 promotes Wnt/β-catenin signaling-dependent cell expansion in cervical carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(24):36115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tong Y, Li Y, Gu H, et al. HSF1, in association with MORC2, downregulates ArgBP2 via the PRC2 family in gastric cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(4 Pt A):1104–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoy SM. Tazemetostat: First Approval. Drugs. 2020;80(5):513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen YT, Zhu F, Lin WR, Ying RB, Yang YP, Zeng LH. The novel EZH2 inhibitor, GSK126, suppresses cell migration and angiogenesis via down-regulating VEGF-A. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77(4):757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Girard N, Bazille C, Lhuissier E, et al. 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep), an inhibitor of the histone methyltransferase EZH2, induces apoptosis and reduces cell migration in chondrosarcoma cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekric D, Neureiter D, Ablinger C, et al. Evaluation of Tazemetostat as a Therapeutically Relevant Substance in Biliary Tract Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clavería-Cabello A, Herranz JM, Latasa MU, et al. Identification and experimental validation of druggable epigenetic targets in hepatoblastoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waldherr M, Misik M, Ferk F, et al. Use of HuH6 and other human-derived hepatoma lines for the detection of genotoxins: a new hope for laboratory animals? Arch Toxicol. 2018;92(2):921–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao H, Xu Y, Mao Y, Zhang Y. Effects of EZH2 gene on the growth and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013;2(2):78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song H, Bucher S, Rosenberg K, et al. Single-cell analysis of hepatoblastoma identifies tumor signatures that predict chemotherapy susceptibility using patient-specific tumor spheroids. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang H, Wu L, Lu L, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics uncovers cellular architecture and developmental trajectories in hepatoblastoma. Hepatology. 2023;77(6):1911–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conway E, Healy E, Bracken AP. PRC2 mediated H3K27 methylations in cellular identity and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;37:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao W, Lee H, Wu W, et al. Multi-faceted epigenetic dysregulation of gene expression promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim KH, Roberts CW. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data that support the findings in this study have been assigned Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession number GSE235202; figure 3 and supplemental figure 2 contain bulk RNA sequencing data with associated GEO files.

Figure 3.

Patient-derived HB cell lines recapitulate HB in vitro. A. Growth and morphological evaluation of cell lines, HBc30, 74, and 81, compared to HepG2 (20X, scale bar 100 μm). B. Bulk RNAseq gene transcripts per million to show GPC3 tumor marker expression in HB cell lines (HBc30, 60, 74, 81) compared to human dermal fibroblasts (HDF), human hepatocytes (HH), and HepG2 cells. C. Heat maps of hierarchical clustering for differentially expressed genes show enhanced expression of Wnt signaling in HB cells, overexpression of tumor suppressors that are known oncogenes, and elevated EZH2 with patterns outside traditional canonical signaling, including PRC2 components (MYC is downregulated and SUZ12 and EED expression does not align with EZH2 expression). Fibroblasts and hepatocytes from Lonza were used as controls.