Introduction

Evolutionary observations have often served as an inspiration for biological design. Decoding of the central dogma of life at a molecular level and understanding of cellular biochemistry have been elegantly used to engineer various synthetic biology applications including building genetic circuits in vitro and in cells1,2, building synthetic translational systems3–5, and metabolic engineering in cells to biosynthesize and even bio-produce complex high value molecules6–8. Here, we review three broad areas of synthetic biology that are inspired by evolutionary observations: (i) combinatorial approaches towards cell-based biomolecular evolution, (ii) engineering interdependencies to establish microbial consortia, and (iii) synthetic immunology. In each of the areas we will highlight the evolutionary premise that was central towards designing these platforms. These are only a subset of the examples where evolution and natural phenomena directly or indirectly serve as a powerful source of inspiration in shaping synthetic biology.

Combinatorial approach towards cell-based biomolecular evolution

Combinatorial approaches for the evolution of biomolecules including catalytic RNAs, peptides, β-lactamase, and triose-phosphate isomerase, demonstrated that the principles of Darwinian evolution can be applied to evolve biomolecules by linking biomolecular diversity to selection processes9–16. Many application-driven in vitro evolution technologies subsequently began to arise17–19. In vitro evolution quickly became a powerful and versatile tool used in myriad ways such as in the development of de novo enzyme function20–22, the improvement of enzyme function in harsh environments23,24, high throughput compartmentalized catalysis25–29, and protein engineering30. Early work on in vitro evolution experiments, along with emerging insights into biomolecular evolution in natural systems (e.g., antibody evolution and maturation in adaptive immune system) and advances in molecular biology, launched a new era of biomolecular directed evolution by linking evolution to cell survival. In this section we focus on bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cell-based directed evolution platforms that use the concept of linking evolution to cell survival as an underlying principle. We will not discuss virus-based or Lenski-like continuous evolution methods that are reviewed in depth elsewhere31–35.

One powerful example of biomolecular evolution by linking evolutionary outcomes to cell survival was the directed evolution of orthogonal tRNA/tRNA synthetase pairs in E. coli36 to expand the genetic code37–40. In these experiments tRNA/tRNA synthetase pairs were evolved to recognize a unique genetic code and incorporate a defined non-canonical amino acid at a defined position in a protein of interest. This system has been developed and utilized abundantly to recombinantly express proteins encoding non-canonical amino acids41–45 in bacteria46, yeast47–51, plants52,53, mammalian cells54–61, Drosophila melanogaster62, Caenorhabditis elegans63, and mice64–68. This technology has been used for translational synthetic biology applications including antibody drug conjugates69, other protein biologics70,71, cell and virus-based vaccines70, and even applied in organisms with synthetic genomes and contracted genetic codes72,73. Another experiment linking evolution to survival was used to evolve and develop genomic base editors. D. Liu and coworkers evolved a tRNA adenosine deaminase to utilize DNA substrates when fused to dCas9, allowing for specific base pair changes at a desired genomic locus74. Several base editors are now in preclinical and clinical trials75,76. Other in vivo evolution experiments in E. coli where evolution is linked to cell survival utilize error-prone polymerase I77, mutagenesis plasmids78, random mutagenesis using mutator strains79,80, processive protein chimera (T7 polymerase + cytidine deaminase) constructs81, CRISPR guided DNA pol82, retroelement-based genome editing and evolution83 and DNA shuffling84.

The principle of linking biomolecular evolution to survival has also been extended to eukaryotic cell-based directed evolution experiments. Some of the pioneering studies demonstrating the use of sophisticated synthetic biology tools for directed evolution in yeast were performed by Cornish and coworkers where they utilized reiterative recombination to sequentially assemble DNA constructs at a defined locus for the in vivo assembly of libraries of multigene pathways85,86. Analogous to the highly error prone DNA pol I system77 developed in E. coli, C. Liu and coworkers developed Orthorep, a continuous evolution platform which utilizes a highly error prone orthogonal DNA polymerase to evolve genes of interest87. This system has been used for applications such as enzyme evolution88, fragment antibody evolution89, and optimizing cis, cis-muconic acid production90, an important bioplastic precursor, in yeast. Several groups have also translated the processive protein chimera and CRISPR guided DNA Pol technologies developed in E. coli, to S. cerevisiae91,92,90. Other synthetic biology tools developed for in vivo directed evolution in S. cerevisiae include utilization of retrotransposon Ty1 for continuous mutagenesis of genes and pathways93 and mutagenic homologous recombination for targeted mutagenesis94. In vivo yeast-based selection platforms have also been utilized to engineer synthetic chromosomes95–97, as well as to study and evolve translationally important viral enzymes89,98,99. In a recent example from our lab, Ornelas et al. developed a modular, phenotypic yeast-based complementation platform (YeRC0M) for molecular characterization and directed evolution of viral RNA capping enzyme to identify attenuation mutations in these essential viral enzymes99.

An example of linking evolution to survival in mammalian cells naturally exists in the adaptive immune system, where B cell selection occurs through combinatorial libraries of immunoglobulins followed by selection and evolution of antigen binding cells. There are a few examples of harnessing these mechanisms to evolve antibodies100 and fluorescent proteins101 in B cells. Evolution experiments have also been performed in mammalian cell lines to evolve ACE2 variants as decoy proteins that bind more tightly to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein than the endogenous ACE2 receptor102. Our immune system uses similar decoy protein strategies103. Mammalian cell-based platforms have also been developed for linking biomolecular evolution to cell survival. Few examples include studies where AID has been fused to dCas9 to evolve the target of the cancer therapeutic bortezomib, PSMB5104 or to diversify genomes105. Similarly, a T7 polymerase-driven continuous editing (TRACE) system was developed which utilizes an AID-T7 polymerase fusion to evolve MEK1 by linking evolution to survival106 (concept from81).

Metabolic crosstalk as a basis of microbial communities

Microbial communities engage in complex behaviors that are often distinct from those in monoculture107. Key features of several natural symbiotic microbial communities of the marine, gut, root and food source microenvironments are microbial crosstalk through metabolic interdependencies, communication networks and spatial organization108,109. Synthetic biologists have leveraged this premise to build synthetic microbial communities and demonstrate their coevolution through amino acid or signaling molecule exchanges107,110–119. There are several reviews on this area of research120–122. Here we will cover a few examples of how evolutionary observations of cell-cell communications beyond amino acid or signaling molecule exchanges have been used to expand the scope of interdependencies in synthetic microbial communities.

Nature has expanded the breadth and scope of ligand-receptor pairs in higher eukaryotes through the evolution of crosstalk mediated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and their corresponding ligands, which include proteins, oligopeptides, biogenic amines, and lipids. These molecular interactions modulate diverse cellular and physiological responses such as growth, death, migration, muscle contraction, neurotransmission, and secretion123,124. Inspired by these observations, Cornish and co-workers identified 32 peptide-GPCR pairs which were then used to construct a language for cell-to-cell communication in yeast125,126. Through the principle of evolution linked to survival, it is anticipated that such GPCR-peptide interfaces could be significantly expanded further by using genome mining and directed evolution approaches127,128.

A remarkable example of bioenergetically driven microbial consortia is the evolution of modern-day eukaryotic organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts, which are believed to have evolved from once free-living life forms that were established as endosymbionts inside a host cell (cell-in-cell system). Extensive metabolite exchange has been observed in naturally existing endosymbiotic systems129. A frontier of synthetic biology is to engineer such endosymbiotic chimeric life forms that are sustained and driven by complex metabolite interdependencies (we term this area of research as directed endosymbiosis). There have been several efforts since the 1930s to build cell-within-cell systems130–142. However more recently, directed endosymbiosis has resulted in engineering cell-within-cell systems where the endosymbiont sustains the growth of the host cell under selection conditions and vice versa. Directed endosymbiosis has been established between yeast cells (host) and engineered E. coli143,144 and cyanobacteria145 (endosymbionts) to develop yeast/bacteria chimera where endosymbiotic bacteria are necessary to support the bioenergetic functions of the host cells. One such example is the engineering of artificial photosynthetic lifeforms composed of cyanobacterial endosymbionts inside of the yeast cells, where the cyanobacteria perform chloroplast like functions for the yeast cell.145 Other efforts to build cell-in-cell systems include B. subtilis in macrophage146,147 and E. coli inside HeLa cells148.

Metabolite driven exchanges also play an important role in organisms like Anabaena spp. that display multicellular behavior.149 Remarkably, laboratory evolution experiments have also demonstrated that multicellular behaviors can be evolved in some extant unicellular organisms. For example, of experimental evolution, selection experiments with unicellular yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, have resulted in generating snowflake variants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae150,151 that demonstrate multicellular behaviors. Similarly multicellular behaviors has also been evolved in algal strains of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.152 In these studies, surprisingly the transition occurred in a rapid manner by subjecting organisms to conditions which favor clustered phenotypes or division of labor150. Multicellular crosstalk and consortia are central to the development and functioning of animal tissues, such as in the immune system. The principles of multicellular eukaryotic cell consortia also see translational applications in the case of tissue regeneration117,153–155 and synthetic immunology.

Synthetic immunology

In this section, we will discuss a few examples of how our molecular understanding of the adaptive immune system can be combined with synthetic biology to develop modern-day therapeutics (synthetic immunology). We will mainly discuss examples of mammalian cell-based therapeutics, and will not cover bacteria, virus and phage based therapies which are discussed in depth elsewhere156–158.

Previously adaptive immune system in animals has been effectively used to evolve catalytic and therapeutic antibodies159. More recently, our molecular understanding of the adaptive immune system has been effectively coupled to advances in synthetic biology to engineer adaptive immune cells (B and T cells) as therapeutics. Particularly, engineered immune cells expressing chimeric receptors (CRs) expressed in mammalian cells have been widely developed as therapeutic modules. CRs are engineered protein fusions between a receptor-binding domain of a targeted protein and a domain that initiates a signaling cascade within the effector cells. CRs were initially reported for EGFR reception linking EGFR signal to insulin production160 and have since been expanded for affecting signaling in various cell lines and tissues160–163. A leading example of this approach is T cells expressing Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs)164–167. The CAR-T cells merge the binding recognition ability of B cells with the neutralizing potential of T cells. The development and identification of the receptor binding domain of CARs targeting specific antigens has often benefited from a variety of directed evolution platforms, including display technologies168–172. Engineered T cells expressing CARs (CAR-T cell therapy) are now used to treat blood lymphoma173–176 as well as to combat solid tumors177–181. In addition to this, synthetic circuits have also been engineered in T cells to instruct T cells to sequentially activate multiple cellular programs such as proliferation and antitumor activity to drive synergistic therapeutic responses182. CAR-independent gene circuits that induced IL-2 secretion in tumor tissue specifically have also been engineered. These are suggested to minimize the toxicity of the CAR T therapies183.

Similar to T-cell based therapies, engineered B-cell-based therapies have also been tested. B cell engineering followed by their interactions within cellular consortia of adaptive immune cells has been repurposed to potentially develop novel therapeutic strategies. For example, B cell technologies have been engineered in non-human cells to develop libraries of human antibodies and select those libraries in vivo184–187. In one example, Lin and coworkers utilized alternative RNA splicing to engineer antibody libraries by fusion of IgG segments to IgM segments that were displayed and selected for on the surface of chicken DT40 cells188. Similar display technologies are undergoing engineering in human cells; for example, Moffett and coworkers developed a method to directly fuse the Ig light chain to the Ig heavy chain using a 60-a.a. linker sequence in an effort to overcome the challenge of combined antibody expression in the evolution of Fab domains189. Engineered B cells expressing evolved anti-HIV antibodies have also been tested as potential therapeutics190,191. Similarly, plasma cells have also been engineered for potential applications in enzyme replacement therapies192.

Summary and Conclusions

In this review we have highlighted how evolutionary observations have directly or indirectly shaped modern-day synthetic biology. We first discussed how the principle of linking biomolecular diversity to cell survival was used to evolve biomolecules with defined functions and properties. Next, we discussed how evolutionary observations of cell-cell communications beyond amino acid or signaling molecule exchanges have inspired the engineering of synthetic microbial communities and artificial endosymbiosis. Lastly, we discussed how the molecular understanding of the adaptive immune system can be combined with synthetic biology to engineer cell-based therapeutics. We believe that these are only a subset of the examples where evolution has inspired synthetic biology. There are a wide range of other fascinating evolutionary phenomena193 such as transition from abiotic information storage to cells and life-forms, origin of viruses, transition from unicellular cells to multicellularity, evolution of tissues and neural networks, evolution of sexual population, evolution of cell differentiation amongst others, that can be potentially leveraged to build new synthetic biology platforms. In addition to this, we believe that the growing involvement of machine learning and modern-day modeling techniques will play a crucial role in synthetic biology advances. As always, advancements made until today will serve as steps towards the greater leaps of tomorrow and we think evolutionary observations and the lessons learned from the molecular understanding and modeling of evolution and natural phenomena will play a central role in synthetic biology of the future.

Figure 1:

Combinatorial approaches for the evolution of biomolecules in bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells. Methods for diversifying biomolecules highlighted in this review include orthogonal tRNA/tRNA synthetase pairs, base editors, error-prone DNA polymerases, T7 RNA polymerase - cytidine deaminase fusions, DNA polymerase - CRISPR Cas9 fusions, and synthetic genomes. All methods outlined here follow the approach of mutate, screen, and select.

Figure 2:

Synthetic microbial communities based on natural observation. A) Naturally occurring microbial consortia exist in all habitats and display distinct characteristics from mono-culture organisms. These communities are largely defined by obligate metabolite exchange and demonstrate division of labor in which growth and bioproduction in one species each carry metabolic burden. B) Mating of fungal species is mediated by secretion of peptide hormones, which bind a GPCR and affect downstream processes which allow mating. Peptide/GPCR pairs are not conserved between all fungi. C) Eukaryotic cells contain metabolically essential organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplast. These organelles are thought to have evolved from endosymbiotic bacteria which propagated inside host cells through syntrophy and/or parasitism. D) The principles of naturally occurring microbial communities have been leveraged by synthetic biologists for a number of purposes. Mee et al., have engineered a 14-member consortium defined by amino acid auxotrophs. Synthetic consortia have also been used as the basis of circuits which can be used to control populations of different species in the consortium. Through the principle of division of labor, consortia can be used to more efficiently synthesize natural products and biofuels which place excessive burden on mono-culture microbes. E) Orthogonal peptide-GPCR pairs from many fungal taxa have been expressed in mutant S. cerevisiae to engineer communication networks based on cell survival. F) Model bacteria have been engineered to express genes associated with modern-day endosymbionts and organelles. These mutant bacteria were fused with mutant S. cerevisiae, where they fulfill an essential bioenergetic role from within the yeast cytosol in the manner of an organelle.

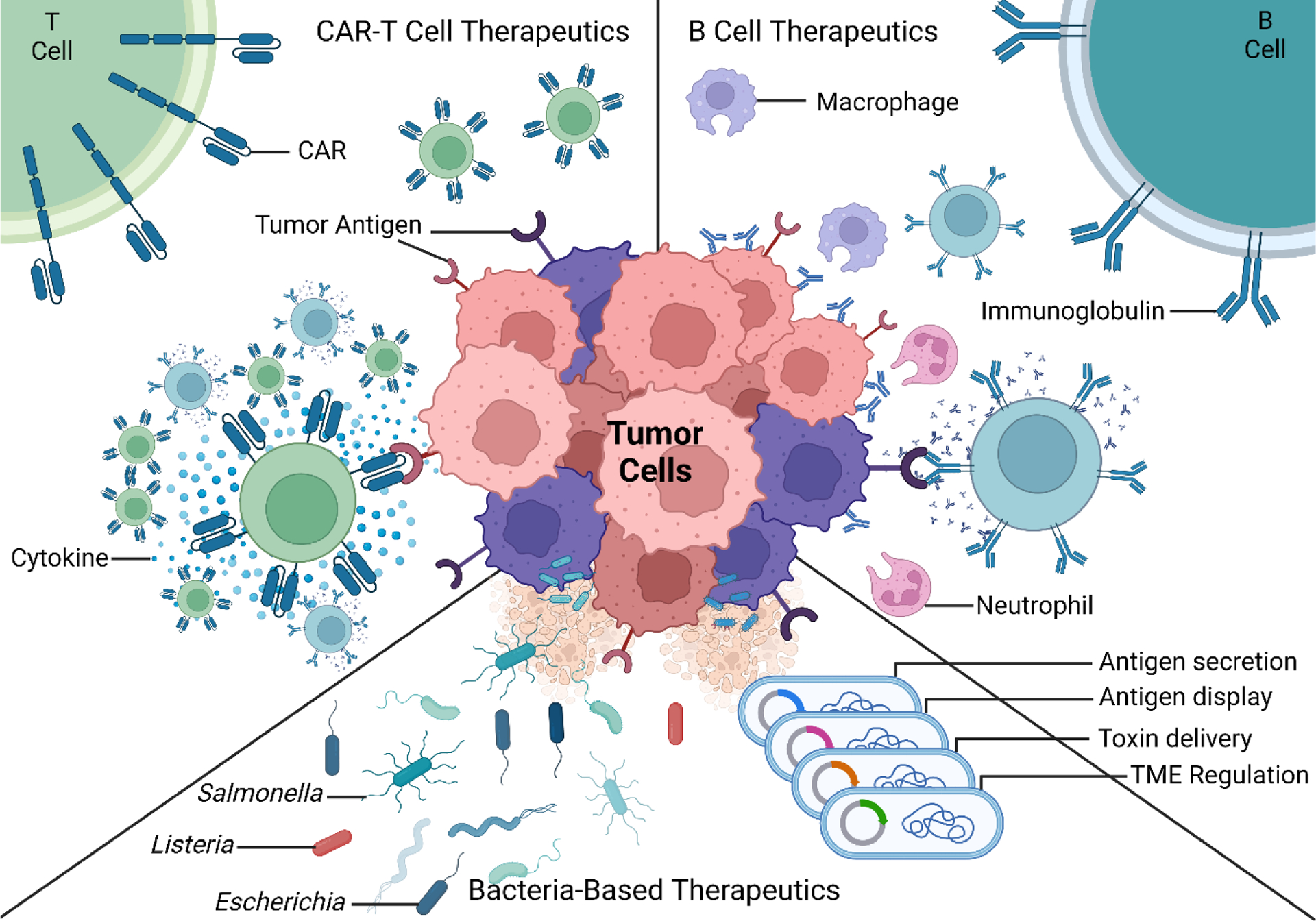

Figure 3:

Modalities of tumor elimination by cellular consortia. CAR T cells act as signaling agents in cellular consortia by means of cytokine release, which stimulates proliferation of T and B cells during the adaptive immune response. Engineered B cells are also used in treating tumors by means of their specific antibody secretion tagging of tumor tissue for elimination by neutrophils and macrophages within the cellular consortia of both the innate and adaptive immune responses. Bacteria-based therapeutics are also used as anti-cancer modalities by means of recruiting cellular consortia by antigen secretion, antigen display on their surfaces, metabolite secretion in the TME, as well as direct toxin delivery for tumor elimination. All methods directly benefit from biomolecular evolution of various receptors (i.e., CARs, antibodies).

Acknowledgements

A.P.M. thanks National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM139949 for the support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We have attempted to cover a board theme in this review to illustrate the importance of evolutionary observations in inspiring synthetic biology technology. Authors acknowledge that the scope of this theme is much broader than what we were able to cover. Therefore, we would like to offer our apologies to any investigators whose relevant work was omitted due to space constraints for this review.

Funding

National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM139949 (A.P.M.) National Institutes of Health Chemical Biology Interface Training Program grant #T32-GM136629 and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (M.Y.O.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicting interests.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

No data were used for the research described in this article

References

- (1).Gardner TS; Cantor CR; Collins JJ Construction of a Genetic Toggle Switch in Escherichia Coli. Nature 2000, 403 (6767), 339–342. 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hockenberry AJ; Jewett MC Synthetic in Vitro Circuits. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2012, 16 (3), 253–259. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.05.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Liu Y; Kim DS; Jewett MC Repurposing Ribosomes for Synthetic Biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2017, 40, 87–94. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wang K; Neumann H; Peak-Chew SY; Chin JW Evolved Orthogonal Ribosomes Enhance the Efficiency of Synthetic Genetic Code Expansion. Nat. Biotechnol 2007, 25 (7), 770–777. 10.1038/nbt1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Melo Czekster C; Robertson WE; Walker AS; Söll D; Schepartz A In Vivo Biosynthesis of a β-Amino Acid-Containing Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138 (16), 5194–5197. 10.1021/jacs.6b01023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Paddon CJ; Keasling JD Semi-Synthetic Artemisinin: A Model for the Use of Synthetic Biology in Pharmaceutical Development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2014, 12 (5), 355–367. 10.1038/nrmicro3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Luo X; Reiter MA; d’Espaux L; Wong J; Denby CM; Lechner A; Zhang Y; Grzybowski AT; Harth S; Lin W; Lee H; Yu C; Shin J; Deng K; Benites VT; Wang G; Baidoo EEK; Chen Y; Dev I; Petzold CJ; Keasling JD Complete Biosynthesis of Cannabinoids and Their Unnatural Analogues in Yeast. Nature 2019, 567 (7746), 123–126. 10.1038/s41586-019-0978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Srinivasan P; Smolke CD Biosynthesis of Medicinal Tropane Alkaloids in Yeast. Nature 2020, 585 (7826), 614–619. 10.1038/s41586-020-2650-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bartel DP; Szostak JW Isolation of New Ribozymes from a Large Pool of Random Sequences. Science 1993, 261 (5127), 1411–1418. 10.1126/science.7690155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wright MC; Joyce GF Continuous in Vitro Evolution of Catalytic Function. Science 1997, 276 (5312), 614–617. 10.1126/science.276.5312.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Green R; Szostak JW Selection of a Ribozyme That Functions as a Superior Template in a Self-Copying Reaction. Science 1992, 258 (5090), 1910–1915. 10.1126/science.1470913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Irvine D; Tuerk C; Gold L Selexion: Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment with Integrated Optimization by Non-Linear Analysis. J. Mol. Biol 1991, 222 (3), 739–761. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hermes JD; Blacklow SC; Knowles JR Searching Sequence Space by Definably Random Mutagenesis: Improving the Catalytic Potency of an Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1990, 87 (2), 696–700. 10.1073/pnas.87.2.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hermes JD; Parekh SM; Blacklow SC; Koster H; Knowles JR A Reliable Method for Random Mutagenesis: The Generation of Mutant Libraries Using Spiked Oligodeoxyribonucleotide Primers. Gene 1989, 84 (1), 143–151. 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Keefe AD; Szostak JW Functional Proteins from a Random-Sequence Library. Nature 2001, 410 (6829), 715–718. 10.1038/35070613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Clackson T; Wells JA In Vitro Selection from Protein and Peptide Libraries. Trends Biotechnol. 1994, 12 (5), 173–184. 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Smith GP Filamentous Fusion Phage: Novel Expression Vectors That Display Cloned Antigens on the Virion Surface. Science 1985, 228 (4705), 1315–1317. 10.1126/science.4001944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Simon AJ; d’Oelsnitz S; Ellington AD Synthetic Evolution. Nat. Biotechnol 2019, 37 (7), 730–743. 10.1038/s41587-019-0157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Golynskiy MV; Haugner JC; Morelli A; Morrone D; Seelig B In Vitro Evolution of Enzymes. In Enzyme Engineering: Methods and Protocols; Samuelson JC, Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2013; pp 73–92. 10.1007/978-1-62703-293-3_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Donnelly AE; Murphy GS; Digianantonio KM; Hecht MH A de Novo Enzyme Catalyzes a Life-Sustaining Reaction in Escherichia Coli. Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14 (3), 253–255. 10.1038/nchembio.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tong CL; Lee K-H; Seelig B De Novo Proteins from Random Sequences through in Vitro Evolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2021, 68, 129–134. 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chen K; Arnold FH Engineering New Catalytic Activities in Enzymes. Nat. Catal 2020, 3 (3), 203–213. 10.1038/s41929-019-0385-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).You L; Arnold FH Directed Evolution of Subtilisin E in Bacillus Subtilis to Enhance Total Activity in Aqueous Dimethylformamide. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 1996, 9 (1), 77–83. 10.1093/protein/9.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Moore JC; Arnold FH Directed Evolution of a Para-Nitrobenzyl Esterase for Aqueous-Organic Solvents. Nat. Biotechnol 1996, 14 (4), 458–467. 10.1038/nbt0496-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Tawfik DS; Griffiths AD Man-Made Cell-like Compartments for Molecular Evolution. Nat. Biotechnol 1998, 16 (7), 652–656. 10.1038/nbt0798-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bernath K; Hai M; Mastrobattista E; Griffiths AD; Magdassi S; Tawfik DS In Vitro Compartmentalization by Double Emulsions: Sorting and Gene Enrichment by Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting. Anal. Biochem 2004, 325 (1), 151–157. 10.1016/j.ab.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Agresti JJ; Antipov E; Abate AR; Ahn K; Rowat AC; Baret J-C; Marquez M; Klibanov AM; Griffiths AD; Weitz DA Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening in Drop-Based Microfluidics for Directed Evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2010, 107 (9), 4004–4009. 10.1073/pnas.0910781107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ghadessy FJ; Ong JL; Holliger P Directed Evolution of Polymerase Function by Compartmentalized Self-Replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2001, 98 (8), 4552–4557. 10.1073/pnas.071052198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ellefson JW; Meyer AJ; Hughes RA; Cannon JR; Brodbelt JS; Ellington AD Directed Evolution of Genetic Parts and Circuits by Compartmentalized Partnered Replication. Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32 (1), 97–101. 10.1038/nbt.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gao C; Mao S; Lo C-HL; Wirsching P; Lerner RA; Janda KD Making Artificial Antibodies: A Format for Phage Display of Combinatorial Heterodimeric Arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1999, 96 (11), 6025–6030. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hendel SJ; Shoulders MD Directed Evolution in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Methods 2021, 18 (4), 346–357. 10.1038/s41592-021-01090-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Rix G; Liu CC Systems for in Vivo Hypermutation: A Quest for Scale and Depth in Directed Evolution. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2021, 64, 20–26. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Badran AH; Liu DR In Vivo Continuous Directed Evolution. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 24, 1–10. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Lenski RE Experimental Evolution and the Dynamics of Adaptation and Genome Evolution in Microbial Populations. ISME J. 2017, 11 (10), 2181–2194. 10.1038/ismej.2017.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Morrison MS; Podracky CJ; Liu DR The Developing Toolkit of Continuous Directed Evolution. Nat. Chem. Biol 2020, 16 (6), 610–619. 10.1038/s41589-020-0532-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wang L; Brock A; Herberich B; Schultz PG Expanding the Genetic Code of Escherichia Coli. Science 2001, 292 (5516), 498–500. 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Young DD; Schultz PG Playing with the Molecules of Life. ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13 (4), 854–870. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Liu CC; Schultz PG Adding New Chemistries to the Genetic Code. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2010, 79 (1), 413–444. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chin JW Expanding and Reprogramming the Genetic Code. Nature 2017, 550 (7674), 53–60. 10.1038/nature24031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Xiao H; Schultz PG At the Interface of Chemical and Biological Synthesis: An Expanded Genetic Code. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2016, 8 (9), a023945. 10.1101/cshperspect.a023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).He X; Gao T; Chen Y; Liu K; Guo J; Niu W Genetic Code Expansion in Pseudomonas Putida KT2440. ACS Synth. Biol 2022, 11 (11), 3724–3732. 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hoppmann C; Wong A; Yang B; Li S; Hunter T; Shokat KM; Wang L Site-Specific Incorporation of Phosphotyrosine Using an Expanded Genetic Code. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13 (8), 842–844. 10.1038/nchembio.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Park H-S; Hohn MJ; Umehara T; Guo L-T; Osborne EM; Benner J; Noren CJ; Rinehart J; Söll D Expanding the Genetic Code of Escherichia Coli with Phosphoserine. Science 2011, 333 (6046), 1151–1154. 10.1126/science.1207203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).van Hest JCM; Kiick KL; Tirrell DA Efficient Incorporation of Unsaturated Methionine Analogues into Proteins in Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122 (7), 1282–1288. 10.1021/ja992749j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Chin JW; Santoro SW; Martin AB; King DS; Wang L; Schultz PG Addition of P-Azido-l-Phenylalanine to the Genetic Code of Escherichia Coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124 (31), 9026–9027. 10.1021/ja027007w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lin S; Zhang Z; Xu H; Li L; Chen S; Li J; Hao Z; Chen PR Site-Specific Incorporation of Photo-Cross-Linker and Bioorthogonal Amino Acids into Enteric Bacterial Pathogens. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (50), 20581–20587. 10.1021/ja209008w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47)*.Zackin MT; Stieglitz JT; Van Deventer JA Genome-Wide Screen for Enhanced Noncanonical Amino Acid Incorporation in Yeast. ACS Synth. Biol 2022, 11 (11), 3669–3680. 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zackin et al screened a pooled Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast knockouts to find single-gene knockout strains that exhibited improved ncAA incorporation at amber (TAG) stop codons. This study is an important foundation for future efforts to engineer cells that incorporate ncAA at more efficiently.

- (48).Ai H; Shen W; Brustad E; Schultz PG Genetically Encoded Alkenes in Yeast. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49 (5), 935–937. 10.1002/anie.200905590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Chin JW; Cropp TA; Anderson JC; Mukherji M; Zhang Z; Schultz PG An Expanded Eukaryotic Genetic Code. Science 2003, 301 (5635), 964–967. 10.1126/science.1084772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50)*.Stieglitz JT; Lahiri P; Stout MI; Van Deventer JA Exploration of Methanomethylophilus Alvus Pyrrolysyl-TRNA Synthetase Activity in Yeast. ACS Synth. Biol 2022, 11 (5), 1824–1834. 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stieglitz et al demonstrate that Methanomethylophilus alvus PylRS (MaPylRS) and tRNACUAMaPyl support the incorporation of ncAAs Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins using stop codon suppression technologies. The addition of the MaPylRS/tRNACUAMaPyl pair to the S. cerevisiae orthogonal translation machinery toolkit opens the door to hundreds of ncAAs that had not previously been genetically encodable.

- (51).Hancock SM; Uprety R; Deiters A; Chin JW Expanding the Genetic Code of Yeast for Incorporation of Diverse Unnatural Amino Acids via a Pyrrolysyl-TRNA Synthetase/TRNA Pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (42), 14819–14824. 10.1021/ja104609m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Li F; Zhang H; Sun Y; Pan Y; Zhou J; Wang J Expanding the Genetic Code for Photoclick Chemistry in E. Coli, Mammalian Cells, and A. Thaliana. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52 (37), 9700–9704. 10.1002/anie.201303477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Schwessinger B; Li X; Ellinghaus TL; Chan LJG; Wei T; Joe A; Thomas N; Pruitt R; Adams PD; Chern MS; Petzold CJ; Liu CC; Ronald PC A Second-Generation Expression System for Tyrosine-Sulfated Proteins and Its Application in Crop Protection. Integr. Biol 2016, 8 (4), 542–545. 10.1039/c5ib00232j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Chen PR; Groff D; Guo J; Ou W; Cellitti S; Geierstanger BH; Schultz PG A Facile System for Encoding Unnatural Amino Acids in Mammalian Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48 (22), 4052–4055. 10.1002/anie.200900683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Beránek V; Willis JCW; Chin JW An Evolved Methanomethylophilus Alvus Pyrrolysyl-TRNA Synthetase/TRNA Pair Is Highly Active and Orthogonal in Mammalian Cells. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (5), 387–390. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Italia JS; Peeler JC; Hillenbrand CM; Latour C; Weerapana E; Chatterjee A Genetically Encoded Protein Sulfation in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Chem. Biol 2020, 16 (4), 379–382. 10.1038/s41589-020-0493-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57)*.Mondal S; Wang S; Zheng Y; Sen S; Chatterjee A; Thompson PR Site-Specific Incorporation of Citrulline into Proteins in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Commun 2021, 12 (1), 45. 10.1038/s41467-020-20279-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Citrullination is a physiologically important post-translational modification of arginine. Mondal et al utilized an engineered E. coli-derived leucyl tRNA synthetase-tRNA pair that incorporates a photocaged-citrulline in response to a nonsense codon in order to enable the site-specific incorporation of citrulline into mammalian cell proteins.

- (58)*.Jewel D; Kelemen RE; Huang RL; Zhu Z; Sundaresh B; Cao X; Malley K; Huang Z; Pasha M; Anthony J; van Opijnen T; Chatterjee A Virus-Assisted Directed Evolution of Enhanced Suppressor TRNAs in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Methods 2023, 20 (1), 95–103. 10.1038/s41592-022-01706-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jewel et al developed virus-assisted directed evolution of tRNAs (VADER) in mammalian cells. This system enriches active and orthogonal tRNA mutants from libraries. The authors use VADER to develop improved mutants of Methanosarcina mazei pyrrolysyl-tRNA and a bacterial tyrosyl-tRNA.

- (59).Liu W; Brock A; Chen S; Chen S; Schultz PG Genetic Incorporation of Unnatural Amino Acids into Proteins in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Methods 2007, 4 (3), 239–244. 10.1038/nmeth1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Mukai T; Kobayashi T; Hino N; Yanagisawa T; Sakamoto K; Yokoyama S Adding L-Lysine Derivatives to the Genetic Code of Mammalian Cells with Engineered Pyrrolysyl-TRNA Synthetases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2008, 371 (4), 818–822. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Gautier A; Nguyen DP; Lusic H; An W; Deiters A; Chin JW Genetically Encoded Photocontrol of Protein Localization in Mammalian Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (12), 4086–4088. 10.1021/ja910688s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Bianco A; Townsley FM; Greiss S; Lang K; Chin JW Expanding the Genetic Code of Drosophila Melanogaster. Nat. Chem. Biol 2012, 8 (9), 748–750. 10.1038/nchembio.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Greiss S; Chin JW Expanding the Genetic Code of an Animal. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (36), 14196–14199. 10.1021/ja2054034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Han S; Yang A; Lee S; Lee H-W; Park CB; Park H-S Expanding the Genetic Code of Mus Musculus. Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (1), 14568. 10.1038/ncomms14568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Ernst RJ; Krogager TP; Maywood ES; Zanchi R; Beránek V; Elliott TS; Barry NP; Hastings MH; Chin JW Genetic Code Expansion in the Mouse Brain. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12 (10), 776–778. 10.1038/nchembio.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Buvoli M; Buvoli A; Leinwand LA Suppression of Nonsense Mutations in Cell Culture and Mice by Multimerized Suppressor TRNA Genes. Mol. Cell. Biol 2000, 20 (9), 3116–3124. 10.1128/MCB.20.9.3116-3124.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Kang J-Y; Kawaguchi D; Coin I; Xiang Z; O’Leary DDM; Slesinger PA; Wang L In Vivo Expression of a Light-Activatable Potassium Channel Using Unnatural Amino Acids. Neuron 2013, 80 (2), 358–370. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68)**.Wang J; Zhang Y; Mendonca CA; Yukselen O; Muneeruddin K; Ren L; Liang J; Zhou C; Xie J; Li J; Jiang Z; Kucukural A; Shaffer SA; Gao G; Wang D AAV-Delivered Suppressor TRNA Overcomes a Nonsense Mutation in Mice. Nature 2022, 604 (7905), 343–348. 10.1038/s41586-022-04533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang et al demonstrate the recombinant adeno-associated virus delivery of a suppressor tRNA safely and efficiently rescued a genetic disease in a mouse model carrying a nonsense mutation. The effects of a single dose of this treatment lasted for more than 6 months.

- (69).Tian F; Lu Y; Manibusan A; Sellers A; Tran H; Sun Y; Phuong T; Barnett R; Hehli B; Song F; DeGuzman MJ; Ensari S; Pinkstaff JK; Sullivan LM; Biroc SL; Cho H; Schultz PG; DiJoseph J; Dougher M; Ma D; Dushin R; Leal M; Tchistiakova L; Feyfant E; Gerber H-P; Sapra P A General Approach to Site-Specific Antibody Drug Conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111 (5), 1766–1771. 10.1073/pnas.1321237111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Rezhdo A; Islam M; Huang M; Van Deventer JA Future Prospects for Noncanonical Amino Acids in Biological Therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2019, 60, 168–178. 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Des Soye BJ; Patel JR; Isaacs FJ; Jewett MC Repurposing the Translation Apparatus for Synthetic Biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 28, 83–90. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Fredens J; Wang K; de la Torre D; Funke LFH; Robertson WE; Christova Y; Chia T; Schmied WH; Dunkelmann DL; Beránek V; Uttamapinant C; Llamazares AG; Elliott TS; Chin JW Total Synthesis of Escherichia Coli with a Recoded Genome. Nature 2019, 569 (7757), 514–518. 10.1038/s41586-019-1192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Wang HH; Isaacs FJ; Carr PA; Sun ZZ; Xu G; Forest CR; Church GM Programming Cells by Multiplex Genome Engineering and Accelerated Evolution. Nature 2009, 460 (7257), 894–898. 10.1038/nature08187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Gaudelli NM; Komor AC; Rees HA; Packer MS; Badran AH; Bryson DI; Liu DR Programmable Base Editing of A•T to G•C in Genomic DNA without DNA Cleavage. Nature 2017, 551 (7681), 464–471. 10.1038/nature24644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Verve Therapeutics, Inc. Open-Label, Phase 1b, Single-Ascending Dose and Optional Re Dosing Study to Evaluate the Safety of VERVE-101 Administered to Patients With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia, Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease, and Uncontrolled Hypercholesterolemia; Clinical trial registration NCT05398029; clinicaltrials.gov, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05398029 (accessed 2023-02-12).

- (76).Kingwell K Base Editors Hit the Clinic. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2022, 21 (8), 545–547. 10.1038/d41573-022-00124-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Camps M; Naukkarinen J; Johnson BP; Loeb LA Targeted Gene Evolution in Escherichia Coli Using a Highly Error-Prone DNA Polymerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2003, 100 (17), 9727–9732. 10.1073/pnas.1333928100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Badran AH; Liu DR Development of Potent in Vivo Mutagenesis Plasmids with Broad Mutational Spectra. Nat. Commun 2015, 6 (1), 8425. 10.1038/ncomms9425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Muteeb G; Sen R Random Mutagenesis Using a Mutator Strain. In In Vitro Mutagenesis Protocols: Third Edition; Braman J, Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2010; pp 411–419. 10.1007/978-1-60761-652-8_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Chou HH; Keasling JD Programming Adaptive Control to Evolve Increased Metabolite Production. Nat. Commun 2013, 4 (1), 2595. 10.1038/ncomms3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Moore CL; Papa LJI; Shoulders MD A Processive Protein Chimera Introduces Mutations across Defined DNA Regions In Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (37), 11560–11564. 10.1021/jacs.8b04001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Halperin SO; Tou CJ; Wong EB; Modavi C; Schaffer DV; Dueber JE CRISPR-Guided DNA Polymerases Enable Diversification of All Nucleotides in a Tunable Window. Nature 2018, 560 (7717), 248–252. 10.1038/s41586-018-0384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Simon AJ; Morrow BR; Ellington AD Retroelement-Based Genome Editing and Evolution. ACS Synth. Biol 2018, 7 (11), 2600–2611. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Yano T; Oue S; Kagamiyama H Directed Evolution of an Aspartate Aminotransferase with New Substrate Specificities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1998, 95 (10), 5511–5515. 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Wingler LM; Cornish VW Reiterative Recombination for the in Vivo Assembly of Libraries of Multigene Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108 (37), 15135–15140. 10.1073/pnas.1100507108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Romanini DW; Peralta-Yahya P; Mondol V; Cornish VW A Heritable Recombination System for Synthetic Darwinian Evolution in Yeast. ACS Synth. Biol 2012, 1 (12), 602–609. 10.1021/sb3000904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Ravikumar A; Arrieta A; Liu CC An Orthogonal DNA Replication System in Yeast. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10 (3), 175–177. 10.1038/nchembio.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Rix G; Watkins-Dulaney EJ; Almhjell PJ; Boville CE; Arnold FH; Liu CC Scalable Continuous Evolution for the Generation of Diverse Enzyme Variants Encompassing Promiscuous Activities. Nat. Commun 2020, 11 (1), 5644. 10.1038/s41467-020-19539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89)**.Wellner A; McMahon C; Gilman MSA; Clements JR; Clark S; Nguyen KM; Ho MH; Hu VJ; Shin J-E; Feldman J; Hauser BM; Caradonna TM; Wingler LM; Schmidt AG; Marks DS; Abraham J; Kruse AC; Liu CC Rapid Generation of Potent Antibodies by Autonomous Hypermutation in Yeast. Nat. Chem. Biol 2021, 17 (10), 1057–1064. 10.1038/s41589-021-00832-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wellner et al develop a synthetic recombinant antibody generation technology that imitates somatic hypermutation inside engineered yeast to produce high-affinity clones. The authors used this system to generate potent nanobodies against the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein, a G-protein-coupled receptor and other targets.

- (90)*.Jensen ED; Ambri F; Bendtsen MB; Javanpour AA; Liu CC; Jensen MK; Keasling JD Integrating Continuous Hypermutation with High-Throughput Screening for Optimization of Cis,Cis-Muconic Acid Production in Yeast. Microb. Biotechnol 2021, 14 (6), 2617–2626. 10.1111/1751-7915.13774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jensen et al integrate a directed evolution workflow for metabolic pathway enzymes using a recently developed orthogonal replication system, OrthoRep. The authors screen for enzyme pathway performance using a high throughput transcription factor-based biosensor. They demonstrate the strength of this approach by evolving the rate-limiting enzymatic reaction of the cis,cis-muconic acid biosynthetic pathway.

- (91)**.Cravens A; Jamil OK; Kong D; Sockolosky JT; Smolke CD Polymerase-Guided Base Editing Enables in Vivo Mutagenesis and Rapid Protein Engineering. Nat. Commun 2021, 12 (1), 1579. 10.1038/s41467-021-21876-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cravens et al describe TaRgeted In vivo Diversification ENabled by T7 RNAP (TRIDENT), a platform for targeted, continual, and inducible diversification at genes of interest. The authors use TRIDENT to evolve a red-shifted fluorescent protein and drug-resistant mutants of an essential enzyme.

- (92).Tou CJ; Schaffer DV; Dueber JE Targeted Diversification in the S. Cerevisiae Genome with CRISPR-Guided DNA Polymerase I. ACS Synth. Biol 2020, 9 (7), 1911–1916. 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Crook N; Abatemarco J; Sun J; Wagner JM; Schmitz A; Alper HS In Vivo Continuous Evolution of Genes and Pathways in Yeast. Nat. Commun 2016, 7 (1), 13051. 10.1038/ncomms13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Finney-Manchester SP; Maheshri N Harnessing Mutagenic Homologous Recombination for Targeted Mutagenesis in Vivo by TaGTEAM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41 (9), e99. 10.1093/nar/gkt150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Dymond JS; Richardson SM; Coombes CE; Babatz T; Muller H; Annaluru N; Blake WJ; Schwerzmann JW; Dai J; Lindstrom DL; Boeke AC; Gottschling DE; Chandrasegaran S; Bader JS; Boeke JD Synthetic Chromosome Arms Function in Yeast and Generate Phenotypic Diversity by Design. Nature 2011, 477 (7365), 471–476. 10.1038/nature10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Blount BA; Lu X; Driessen MRM; Jovicevic D; Sanchez MI; Ciurkot K; Zhao Y; Lauer S; McKiernan RM; Gowers G-OF; Sweeney F; Fanfani V; Lobzaev E; Palacios-Flores K; Walker R; Hesketh A; Oliver SG; Cai Y; Stracquadanio G; Mitchell LA; Bader JS; Boeke JD; Ellis T Synthetic Yeast Chromosome XI Design Enables Extrachromosomal Circular DNA Formation on Demand. bioRxiv July 16, 2022, p 2022.07.15.500197. 10.1101/2022.07.15.500197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Hutchison CA; Chuang R-Y; Noskov VN; Assad-Garcia N; Deerinck TJ; Ellisman MH; Gill J; Kannan K; Karas BJ; Ma L; Pelletier JF; Qi Z-Q; Richter RA; Strychalski EA; Sun L; Suzuki Y; Tsvetanova B; Wise KS; Smith HO; Glass JI; Merryman C; Gibson DG; Venter JC Design and Synthesis of a Minimal Bacterial Genome. Science 2016, 351 (6280), aad6253. 10.1126/science.aad6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Ho CK; Martins A; Shuman S A Yeast-Based Genetic System for Functional Analysis of Viral MRNA Capping Enzymes. J. Virol 2000, 74 (12), 5486–5494. 10.1128/JVI.74.12.5486-5494.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99)*.Ornelas MY; Thomas AY; Johnson Rosas LI; Scoville RO; Mehta AP Synthetic Platforms for Characterizing and Targeting of SARS-CoV-2 Genome Capping Enzymes. ACS Synth. Biol 2022, 11 (11), 3759–3771. 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ornelas et al developed a synthetic, phenotypic yeast-based complementation platform (YeRC0M) for molecular characterization and targeting of SARS-CoV-2 genome-encoded RNA cap-0 (guanine-N7)-methyltransferase (N7-MTase) enzyme, nsp14. The authors identified important protein domains and amino acid residues that are essential for SARS-CoV-2 nsp14 N7-MTase activity and combined YeRC0M with directed evolution to identify attenuation mutations in SARS-CoV-2 nsp14.

- (100).Bowers PM; Horlick RA; Neben TY; Toobian RM; Tomlinson GL; Dalton JL; Jones HA; Chen A; Altobell L; Zhang X; Macomber JL; Krapf IP; Wu BF; McConnell A; Chau B; Holland T; Berkebile AD; Neben SS; Boyle WJ; King DJ Coupling Mammalian Cell Surface Display with Somatic Hypermutation for the Discovery and Maturation of Human Antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108 (51), 20455–20460. 10.1073/pnas.1114010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Wang L; Jackson WC; Steinbach PA; Tsien RY Evolution of New Nonantibody Proteins via Iterative Somatic Hypermutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2004, 101 (48), 16745–16749. 10.1073/pnas.0407752101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Chan KK; Dorosky D; Sharma P; Abbasi SA; Dye JM; Kranz DM; Herbert AS; Procko E Engineering Human ACE2 to Optimize Binding to the Spike Protein of SARS Coronavirus 2. Science 2020, 369 (6508), 1261–1265. 10.1101/2020.03.16.994236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Mantovani A; Locati M; Vecchi A; Sozzani S; Allavena P Decoy Receptors: A Strategy to Regulate Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines. Trends Immunol. 2001, 22 (6), 328–336. 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)01941-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Hess GT; Frésard L; Han K; Lee CH; Li A; Cimprich KA; Montgomery SB; Bassik MC Directed Evolution Using DCas9-Targeted Somatic Hypermutation in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Methods 2016, 13 (12), 1036–1042. 10.1038/nmeth.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Ma Y; Zhang J; Yin W; Zhang Z; Song Y; Chang X Targeted AID-Mediated Mutagenesis (TAM) Enables Efficient Genomic Diversification in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Methods 2016, 13 (12), 1029–1035. 10.1038/nmeth.4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Chen H; Liu S; Padula S; Lesman D; Griswold K; Lin A; Zhao T; Marshall JL; Chen F Efficient, Continuous Mutagenesis in Human Cells Using a Pseudo-Random DNA Editor. Nat. Biotechnol 2020, 38 (2), 165–168. 10.1038/s41587-019-0331-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Wintermute EH; Silver PA Emergent Cooperation in Microbial Metabolism. Mol. Syst. Biol 2010, 6 (1), 407. 10.1038/msb.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Zelezniak A; Andrejev S; Ponomarova O; Mende DR; Bork P; Patil KR Metabolic Dependencies Drive Species Co-Occurrence in Diverse Microbial Communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2015, 112 (20), 6449–6454. 10.1073/pnas.1421834112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Ponomarova O; Patil KR Metabolic Interactions in Microbial Communities: Untangling the Gordian Knot. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 2015, 27, 37–44. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Mee MT; Collins JJ; Church GM; Wang HH Syntrophic Exchange in Synthetic Microbial Communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111 (20), E2149–E2156. 10.1073/pnas.1405641111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (111).Shou W; Ram S; Vilar JMG Synthetic Cooperation in Engineered Yeast Populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2007, 104 (6), 1877–1882. 10.1073/pnas.0610575104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (112)*.Machado D; Maistrenko OM; Andrejev S; Kim Y; Bork P; Patil KR; Patil KR Polarization of Microbial Communities between Competitive and Cooperative Metabolism. Nat. Ecol. Evol 2021, 5 (2), 195–203. 10.1038/s41559-020-01353-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, the authors used genome-scale metabolic modelling to reveal two microbial community types at the poles of a trade-off between metabolic competition and cooperation. Competitive communities were characterized by larger genomes and overlapping nutritional requirements, while cooperative communities were characterized by smaller genomes and many auxotrophies.

- (113).Machado D; Andrejev S; Tramontano M; Patil KR Fast Automated Reconstruction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for Microbial Species and Communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (15), 7542–7553. 10.1093/nar/gky537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (114).Hong SH; Hegde M; Kim J; Wang X; Jayaraman A; Wood TK Synthetic Quorum-Sensing Circuit to Control Consortial Biofilm Formation and Dispersal in a Microfluidic Device. Nat. Commun 2012, 3 (1), 613. 10.1038/ncomms1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (115).Chen Y; Kim JK; Hirning AJ; Josić K; Bennett MR Emergent Genetic Oscillations in a Synthetic Microbial Consortium. Science 2015, 349 (6251), 986–989. 10.1126/science.aaa3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (116).You L; Cox RS; Weiss R; Arnold FH Programmed Population Control by Cell–Cell Communication and Regulated Killing. Nature 2004, 428 (6985), 868–871. 10.1038/nature02491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (117)*.Ma Y; Budde MW; Mayalu MN; Zhu J; Lu AC; Murray RM; Elowitz MB Synthetic Mammalian Signaling Circuits for Robust Cell Population Control. Cell 2022, 185 (6), 967–979.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mammalian cells were engineered to send and receive signals using the plant hormone auxin, allowing cells to control population size through quorum sensing. In this study, population control was made avoid cheater mutations through a paradoxical circuit design, whereby attenuating signal sensing leads to cell death.

- (118).Din MO; Danino T; Prindle A; Skalak M; Selimkhanov J; Allen K; Julio E; Atolia E; Tsimring LS; Bhatia SN; Hasty J Synchronized Cycles of Bacterial Lysis for in Vivo Delivery. Nature 2016, 536 (7614), 81–85. 10.1038/nature18930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (119).Lentini R; Martín NY; Forlin M; Belmonte L; Fontana J; Cornella M; Martini L; Tamburini S; Bentley WE; Jousson O; Mansy SS Two-Way Chemical Communication between Artificial and Natural Cells. ACS Cent. Sci 2017, 3 (2), 117–123. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (120).Robinson AO; Venero OM; Adamala KP Toward Synthetic Life: Biomimetic Synthetic Cell Communication. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2021, 64, 165–173. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (121).McCarty NS; Ledesma-Amaro R Synthetic Biology Tools to Engineer Microbial Communities for Biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37 (2), 181–197. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (122).Brenner K; You L; Arnold FH Engineering Microbial Consortia: A New Frontier in Synthetic Biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26 (9), 483–489. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (123).Yang D; Zhou Q; Labroska V; Qin S; Darbalaei S; Wu Y; Yuliantie E; Xie L; Tao H; Cheng J; Liu Q; Zhao S; Shui W; Jiang Y; Wang M-W G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Structure- and Function-Based Drug Discovery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther 2021, 6 (1), 1–27. 10.1038/s41392-020-00435-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (124).Insel PA; Sriram K; Gorr MW; Wiley SZ; Michkov A; Salmerón C; Chinn AM GPCRomics: An Approach to Discover GPCR Drug Targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2019, 40 (6), 378–387. 10.1016/j.tips.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (125).Billerbeck S; Brisbois J; Agmon N; Jimenez M; Temple J; Shen M; Boeke JD; Cornish VW A Scalable Peptide-GPCR Language for Engineering Multicellular Communication. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 5057. 10.1038/s41467-018-07610-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (126)*.Billerbeck S; Cornish VW Peptide-Dependent Growth in Yeast via Fine-Tuned Peptide/GPCR-Activated Essential Gene Expression. Biochemistry 2022, 61 (3), 150–159. 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Through: 1) transcriptional control of GPCR-activated TFs, 2) promoters with different output dynamics, and 3) recoded peptide ligands, the authors establish three control points allowing fine-tuning of synthetic GPCR response, activation, and sensitivity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

- (127).Lengger B; Jensen MK Engineering G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signalling in Yeast for Biotechnological and Medical Purposes. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 20 (1), foz087. 10.1093/femsyr/foz087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (128).Schütz M; Schöppe J; Sedlák E; Hillenbrand M; Nagy-Davidescu G; Ehrenmann J; Klenk C; Egloff P; Kummer L; Plückthun A Directed Evolution of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Yeast for Higher Functional Production in Eukaryotic Expression Hosts. Sci. Rep 2016, 6 (1), 21508. 10.1038/srep21508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (129).McCutcheon JP; McDonald BR; Moran NA Convergent Evolution of Metabolic Roles in Bacterial Co-Symbionts of Insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2009, 106 (36), 15394–15399. 10.1073/pnas.0906424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (130).Buchsbaum R Chick Tissue Cells and Chlorella in Mixed Cultures. Physiol. Zool 1937, 10 (4), 373–380. 10.1086/physzool.10.4.30151423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (131).Anderson JC; Clarke EJ; Arkin AP; Voigt CA Environmentally Controlled Invasion of Cancer Cells by Engineered Bacteria. J. Mol. Biol 2006, 355 (4), 619–627. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (132).Narayanan K; Warburton PE DNA Modification and Functional Delivery into Human Cells Using Escherichia Coli DH10B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (9), e51. 10.1093/nar/gng051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (133).Grillot-Courvalin C; Goussard S; Huetz F; Ojcius DM; Courvalin P Functional Gene Transfer from Intracellular Bacteria to Mammalian Cells. Nat. Biotechnol 1998, 16 (9), 862–866. 10.1038/nbt0998-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (134).Critchley RJ; Jezzard S; Radford KJ; Goussard S; Lemoine NR; Grillot-Courvalin C; Vassaux G Potential Therapeutic Applications of Recombinant, Invasive E. Coli. Gene Ther. 2004, 11 (15), 1224–1233. 10.1038/sj.gt.3302281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (135).Zhao M; Yang M; Li X-M; Jiang P; Baranov E; Li S; Xu M; Penman S; Hoffman RM Tumor-Targeting Bacterial Therapy with Amino Acid Auxotrophs of GFP-Expressing Salmonella Typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2005, 102 (3), 755–760. 10.1073/pnas.0408422102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (136).Agapakis CM; Niederholtmeyer H; Noche RR; Lieberman TD; Megason SG; Way JC; Silver PA Towards a Synthetic Chloroplast. PLoS ONE 2011, 6 (4), e18877. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (137).Alvarez M; Reynaert N; Chávez MN; Aedo G; Araya F; Hopfner U; Fernández J; Allende ML; Egaña JT Generation of Viable Plant-Vertebrate Chimeras. PLOS ONE 2015, 10 (6), e0130295. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (138).Özugur S; Chávez MN; Sanchez-Gonzalez R; Kunz L; Nickelsen J; Straka H Green Oxygen Power Plants in the Brain Rescue Neuronal Activity. iScience 2021, 24 (10), 103158. 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (139).Matsunaga T; Hashimoto K; Nakamura N; Nakamura K; Hashimoto S Phagocytosis of Bacterial Magnetite by Leucocytes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 1989, 31 (4), 401–405. 10.1007/BF00257612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (140).Bielecki J; Youngman P; Connelly P; Portnoy DA Bacillus Subtilis Expressing a Haemolysin Gene from Listeria Monocytogenes Can Grow in Mammalian Cells. Nature 1990, 345 (6271), 175–176. 10.1038/345175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (141).Elani Y; Trantidou T; Wylie D; Dekker L; Polizzi K; Law RV; Ces O Constructing Vesicle-Based Artificial Cells with Embedded Living Cells as Organelle-like Modules. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 4564. 10.1038/s41598-018-22263-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (142).Karas BJ; Moreau NG; Deerinck TJ; Gibson DG; Venter JC; Smith HO; Glass JI Direct Transfer of a Mycoplasma Mycoides Genome to Yeast Is Enhanced by Removal of the Mycoides Glycerol Uptake Factor Gene GlpF. ACS Synth. Biol 2019, 8 (2), 239–244. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (143).Mehta AP; Supekova L; Chen J-H; Pestonjamasp K; Webster P; Ko Y; Henderson SC; McDermott G; Supek F; Schultz PG Engineering Yeast Endosymbionts as a Step toward the Evolution of Mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2018, 115 (46), 11796–11801. 10.1073/pnas.1813143115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (144).Mehta AP; Ko Y; Supekova L; Pestonjamasp K; Li J; Schultz PG Toward a Synthetic Yeast Endosymbiont with a Minimal Genome. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (35), 13799–13802. 10.1021/jacs.9b08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (145)*.Cournoyer JE; Altman SD; Gao Y; Wallace CL; Zhang D; Lo G-H; Haskin NT; Mehta AP Engineering Artificial Photosynthetic Life-Forms through Endosymbiosis. Nat. Commun 2022, 13 (1), 2254. 10.1038/s41467-022-29961-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors established engineered, endosymbiotic Synechococcus elongatus within the cytosol of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where the cyanobacterium establishes bioenergetically relevant endosymbiosis. The platform could be utilized in further efforts to transfer photosynthetic capabilities in yeast.

- (146)*.Madsen CS; Makela AV; Greeson EM; Hardy JW; Contag CH Engineered Endosymbionts That Alter Mammalian Cell Surface Marker, Cytokine and Chemokine Expression. Commun. Biol 2022, 5 (1), 1–12. 10.1038/s42003-022-03851-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bacillus subtilis was engineered as an endosymbiont to reside in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells, avoid phagosome destruction and act as a protein delivery chassis for delivery into the nucleus. This platform comprises a new tool for directing gene expression in mammalian cells.

- (147).Madsen CS; Makela AV; Greeson EM; Hardy JW; Contag CH Engineered Endosymbionts Capable of Directing Mammalian Cell Gene Expression. bioRxiv October 7, 2021, p 2021.10.05.463266. 10.1101/2021.10.05.463266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (148)*.Gäbelein CG; Reiter MA; Ernst C; Giger GH; Vorholt JA Engineering Endosymbiotic Growth of E. Coli in Mammalian Cells. ACS Synth. Biol 2022. 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors injected diverse bacteria, including E. coli, into the cytosol of HeLa cells. In order to control the rate of intracellular growth, the authors introduced multiple auxotrophies into E. coli, thereby extending the survival of the host-endosymbiont pair.

- (149).Camargo S; Leshkowitz D; Dassa B; Mariscal V; Flores E; Stavans J; Arbel-Goren R Impaired Cell-Cell Communication in the Multicellular Cyanobacterium Anabaena Affects Carbon Uptake, Photosynthesis, and the Cell Wall. iScience 2021, 24 (1), 101977. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (150).Ratcliff WC; Denison RF; Borrello M; Travisano M Experimental Evolution of Multicellularity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2012, 109 (5), 1595–1600. 10.1073/pnas.1115323109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (151).Ratcliff WC; Fankhauser JD; Rogers DW; Greig D; Travisano M Origins of Multicellular Evolvability in Snowflake Yeast. Nat. Commun 2015, 6 (1), 6102. 10.1038/ncomms7102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (152).Ratcliff WC; Herron MD; Howell K; Pentz JT; Rosenzweig F; Travisano M Experimental Evolution of an Alternating Uni- and Multicellular Life Cycle in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Nat. Commun 2013, 4 (1), 2742. 10.1038/ncomms3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (153).Toda S; McKeithan WL; Hakkinen TJ; Lopez P; Klein OD; Lim WA Engineering Synthetic Morphogen Systems That Can Program Multicellular Patterning. Science 2020, 370 (6514), 327–331. 10.1126/science.abc0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (154).Stapornwongkul KS; de Gennes M; Cocconi L; Salbreux G; Vincent J-P Patterning and Growth Control in Vivo by an Engineered GFP Gradient. Science 2020, 370 (6514), 321–327. 10.1126/science.abb8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (155).Green DW; Watson JA; Ben-Nissan B; Watson GS; Stamboulis A Synthetic Tissue Engineering with Smart, Cytomimetic Protocells. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 120941. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (156)*.Gurbatri CR; Arpaia N; Danino T Engineering Bacteria as Interactive Cancer Therapies. Science 2022, 378 (6622), 858–864. 10.1126/science.add9667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gurbatri et al. reviews advancements made towards designing genetics circuits in bacteria, for their subsequent use as cancer therapeutics by payload delivery, antigen expression, and immune system recruitment.

- (157).Gordillo Altamirano FL; Barr JJ Phage Therapy in the Postantibiotic Era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2019, 32 (2), e00066–18. 10.1128/CMR.00066-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (158)*.Pires DP; Costa AR; Pinto G; Meneses L; Azeredo J Current Challenges and Future Opportunities of Phage Therapy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2020, 44 (6), 684–700. 10.1093/femsre/fuaa017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pires et al. discusses the current state and techniques of phage therapy in treating antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, and presents challenges to future adoption of this technology due limited complete clinical trials.

- (159).Lerner RA; Benkovic SJ; Schultz PG At the Crossroads of Chemistry and Immunology: Catalytic Antibodies. Science 1991, 252 (5006), 659–667. 10.1126/science.2024118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (160).Riedel H; Schlessinger J; Ullrich A A Chimeric, Ligand-Binding v-ErbB/EGF Receptor Retains Transforming Potential. Science 1987, 236 (4798), 197–200. 10.1126/science.3494307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (161).Roussel MF; Downing JR; Ashmun RA; Rettenmier CW; Sherr CJ Colony-Stimulating Factor 1-Mediated Regulation of a Chimeric c-Fms/v-Fms Receptor Containing the v-Fms-Encoded Tyrosine Kinase Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1988, 85 (16), 5903–5907. 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (162).Hatakeyama M; Doi T; Kono T; Maruyama M; Minamoto S; Mori H; Kobayashi M; Uchiyama T; Taniguchi T Transmembrane Signaling of Interleukin 2 Receptor. Conformation and Function of Human Interleukin 2 Receptor (P55)/Insulin Receptor Chimeric Molecules. J. Exp. Med 1987, 166 (2), 362–375. 10.1084/jem.166.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (163).Green S; Chambon P Oestradiol Induction of a Glucocorticoid-Responsive Gene by a Chimaeric Receptor. Nature 1987, 325 (6099), 75–78. 10.1038/325075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (164).Fesnak AD; June CH; Levine BL Engineered T Cells: The Promise and Challenges of Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16 (9), 566–581. 10.1038/nrc.2016.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (165).June CH; Sadelain M Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med 2018, 379 (1), 64–73. 10.1056/NEJMra1706169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (166).Neelapu SS; Tummala S; Kebriaei P; Wierda W; Gutierrez C; Locke FL; Komanduri KV; Lin Y; Jain N; Daver N; Westin J; Gulbis AM; Loghin ME; de Groot JF; Adkins S; Davis SE; Rezvani K; Hwu P; Shpall EJ Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy — Assessment and Management of Toxicities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2018, 15 (1), 47–62. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (167).June CH; O’Connor RS; Kawalekar OU; Ghassemi S; Milone MC CAR T Cell Immunotherapy for Human Cancer. Science 2018, 359 (6382), 1361–1365. 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (168)*.Zajc CU; Salzer B; Taft JM; Reddy ST; Lehner M; Traxlmayr MW Driving CARs with Alternative Navigation Tools – the Potential of Engineered Binding Scaffolds. FEBS J. 2021, 288 (7), 2103–2118. 10.1111/febs.15523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zajc et al. discusses the advancements of alternative antigen-targeting domains used in CARs, to provide a versatile repertoire of binders in addition to the most engineered binding domain, scFvj.

- (169).Gacerez AT; Hua CK; Ackerman ME; Sentman CL Chimeric Antigen Receptors with Human ScFvs Preferentially Induce T Cell Anti-Tumor Activity against Tumors with High B7H6 Expression. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 2018, 67 (5), 749–759. 10.1007/s00262-018-2124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (170)*.Sharma P; Marada VVVR; Cai Q; Kizerwetter M; He Y; Wolf SP; Schreiber K; Clausen H; Schreiber H; Kranz DM Structure-Guided Engineering of the Affinity and Specificity of CARs against Tn-Glycopeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2020, 117 (26), 15148–15159. 10.1073/pnas.1920662117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sharma et al. subjects antibody sequences to directed evolution to develop antibodies that are specific to epitopes of glycoproteins that contain serine/threonine-linked GalNAc, common motifs present in the aberrant Tn-glycans of solid tumors. When expressed as CARs, the engineered scFv sequences showed much higher specificity as compared to wild-type control.

- (171).Zhao Q; Ahmed M; Tassev DV; Hasan A; Kuo T-Y; Guo H-F; O’Reilly RJ; Cheung N-KV Affinity Maturation of T-Cell Receptor-like Antibodies for Wilms Tumor 1 Peptide Greatly Enhances Therapeutic Potential. Leukemia 2015, 29 (11), 2238–2247. 10.1038/leu.2015.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (172)*.Butler SE; Brog RA; Chang CH; Sentman CL; Huang YH; Ackerman ME Engineering a Natural Ligand-Based CAR: Directed Evolution of the Stress-Receptor NKp30. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 2022, 71 (1), 165–176. 10.1007/s00262-021-02971-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Butler et al. targeted NKp30, a natural CAR receptor on T cells that does not rely on scFv, and developed better binding variants of NKp30 to its natural immunoligand, B7H6. By utilizing the yeast-display evolved variants as CAR domains, engineered T cells mounted a more robust immune response that was retained over a broader range of B7H6 concentrations.

- (173).Kalos M; Levine BL; Porter DL; Katz S; Grupp SA; Bagg A; June CH T Cells with Chimeric Antigen Receptors Have Potent Antitumor Effects and Can Establish Memory in Patients with Advanced Leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med 2011, 3 (95), 95ra73–95ra73. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (174).Schuster SJ; Bishop MR; Tam CS; Waller EK; Borchmann P; McGuirk JP; Jäger U; Jaglowski S; Andreadis C; Westin JR; Fleury I; Bachanova V; Foley SR; Ho PJ; Mielke S; Magenau JM; Holte H; Pantano S; Pacaud LB; Awasthi R; Chu J; Anak Ö; Salles G; Maziarz RT Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med 2019, 380 (1), 45–56. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (175).Lee DW; Kochenderfer JN; Stetler-Stevenson M; Cui YK; Delbrook C; Feldman SA; Fry TJ; Orentas R; Sabatino M; Shah NN; Steinberg SM; Stroncek D; Tschernia N; Yuan C; Zhang H; Zhang L; Rosenberg SA; Wayne AS; Mackall CL T Cells Expressing CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia in Children and Young Adults: A Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Trial. The Lancet 2015, 385 (9967), 517–528. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (176).Neelapu SS; Locke FL; Bartlett NL; Lekakis LJ; Miklos DB; Jacobson CA; Braunschweig I; Oluwole OO; Siddiqi T; Lin Y; Timmerman JM; Stiff PJ; Friedberg JW; Flinn IW; Goy A; Hill BT; Smith MR; Deol A; Farooq U; McSweeney P; Munoz J; Avivi I; Castro JE; Westin JR; Chavez JC; Ghobadi A; Komanduri KV; Levy R; Jacobsen ED; Witzig TE; Reagan P; Bot A; Rossi J; Navale L; Jiang Y; Aycock J; Elias M; Chang D; Wiezorek J; Go WY Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med 2017, 377 (26), 2531–2544. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (177).Newick K; O’Brien S; Moon E; Albelda SM CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Annu. Rev. Med 2017, 68 (1), 139–152. 10.1146/annurev-med-062315-120245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (178).Bonifant CL; Jackson HJ; Brentjens RJ; Curran KJ Toxicity and Management in CAR T-Cell Therapy. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2016, 3. 10.1038/mto.2016.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (179).Cherkassky L; Morello A; Villena-Vargas J; Feng Y; Dimitrov DS; Jones DR; Sadelain M; Adusumilli PS Human CAR T Cells with Cell-Intrinsic PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade Resist Tumor-Mediated Inhibition. J. Clin. Invest 2016, 126 (8), 3130–3144. 10.1172/JCI83092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (180).Beatty GL; Haas AR; Maus MV; Torigian DA; Soulen MC; Plesa G; Chew A; Zhao Y; Levine BL; Albelda SM; Kalos M; June CH Mesothelin-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor MRNA-Engineered T Cells Induce Antitumor Activity in Solid Malignancies. Cancer Immunol. Res 2014, 2 (2), 112–120. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (181).Lee DW; Santomasso BD; Locke FL; Ghobadi A; Turtle CJ; Brudno JN; Maus MV; Park JH; Mead E; Pavletic S; Go WY; Eldjerou L; Gardner RA; Frey N; Curran KJ; Peggs K; Pasquini M; DiPersio JF; Brink M. R. M. van den; Komanduri KV; Grupp SA; Neelapu SS ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 2019, 25 (4), 625–638. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (182)**.Li H-S; Israni DV; Gagnon KA; Gan KA; Raymond MH; Sander JD; Roybal KT; Joung JK; Wong WW; Khalil AS Multidimensional Control of Therapeutic Human Cell Function with Synthetic Gene Circuits. Science 2022, 378 (6625), 1227–1234. 10.1126/science.ade0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Li et al. engineered transcription regulators (synZiFTRs) that could be activated by FDA-approved small molecules (grazoprevir, 4-hydroxytamoxifen/tamoxifen, abscisic acid), and leveraged the ability of synZiFTRs to control the gene expression of CARs, effectively and selectively modulating CAR activity against cancer cells by the addition of these small molecules.

- (183)**.Allen GM; Frankel NW; Reddy NR; Bhargava HK; Yoshida MA; Stark SR; Purl M; Lee J; Yee JL; Yu W; Li AW; Garcia KC; El-Samad H; Roybal KT; Spitzer MH; Lim WA Synthetic Cytokine Circuits That Drive T Cells into Immune-Excluded Tumors. Science 2022, 378 (6625), eaba1624. 10.1126/science.aba1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Allen et al. developed an alternative set of CARs that rely on Notch receptor signaling, to target immune-excluded tumor by supplementing the activity of T cells with robust signaling by inflammatory cytokine, IL-2. The researchers leveraged the targeting ability of CARs with the signaling capacity of IL-2 to illicit a robust anti-tumor response, locally, where in isolation, the response would have been broad and toxic.

- (184).Fusil F; Calattini S; Amirache F; Mancip J; Costa C; Robbins JB; Douam F; Lavillette D; Law M; Defrance T; Verhoeyen E; Cosset F-L A Lentiviral Vector Allowing Physiologically Regulated Membrane-Anchored and Secreted Antibody Expression Depending on B-Cell Maturation Status. Mol. Ther 2015, 23 (11), 1734–1747. 10.1038/mt.2015.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (185).Hashimoto K; Kurosawa K; Seo H; Ohta K Rapid Chimerization of Antibodies. In Human Monoclonal Antibodies: Methods and Protocols; Steinitz M, Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, 2019; pp 307–317. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8958-4_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (186).Hashimoto K; Kurosawa K; Murayama A; Seo H; Ohta K B Cell-Based Seamless Engineering of Antibody Fc Domains. PLOS ONE 2016, 11 (12), e0167232. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (187).Doerner A; Rhiel L; Zielonka S; Kolmar H Therapeutic Antibody Engineering by High Efficiency Cell Screening. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588 (2), 278–287. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (188).Lin W; Kurosawa K; Murayama A; Kagaya E; Ohta K B-Cell Display-Based One-Step Method to Generate Chimeric Human IgG Monoclonal Antibodies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (3), e14. 10.1093/nar/gkq1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (189).Moffett HF; Harms CK; Fitzpatrick KS; Tooley MR; Boonyaratanakornkit J; Taylor JJ B Cells Engineered to Express Pathogen-Specific Antibodies Protect against Infection. Sci. Immunol 2019, 4 (35), eaax0644. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (190)*.Nahmad AD; Lazzarotto CR; Zelikson N; Kustin T; Tenuta M; Huang D; Reuveni I; Nataf D; Raviv Y; Horovitz-Fried M; Dotan I; Carmi Y; Rosin-Arbesfeld R; Nemazee D; Voss JE; Stern A; Tsai SQ; Barzel A In Vivo Engineered B Cells Secrete High Titers of Broadly Neutralizing Anti-HIV Antibodies in Mice. Nat. Biotechnol 2022, 40 (8), 1241–1249. 10.1038/s41587-022-01328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nahmad et al. developed a viral method to rapidly produce B cell populations, in vivo, that secrete specific antibodies (anti-HIV). The method is inspired by ex vivo transplantation of B cells, but overcomes the clinical limitations of transplantation by direct generation of cell lines, and their selection in vivo.