Abstract

Purpose.

Abnormalities in notochordal development can cause a range of developmental malformations, including the split notochord syndrome and split cord malformations. We describe two cases that appear related to unusual notochordal malformations, in a female and a male infant diagnosed in the early postnatal and prenatal periods, which were treated at our institution. These cases were unusual from prior cases given a shared constellation of an anterior cervicothoracic meningocele with a prominent “neural stalk”, which coursed ventrally from the spinal cord into the thorax in proximity to a foregut duplication cyst.

Methods.

Two patients with this unusual spinal cord anomaly were assessed clinically, and with neuroimaging and genetics studies.

Results.

We describe common anatomical features (anterior neural stalk arising from the spinal cord, vertebral abnormality, enteric duplication cyst, and diaphragmatic hernia) that support a common etiopathogenesis and distinguish these cases. In both cases, we opted for conservative neurosurgical management in regards to the spinal cord anomaly. We proposed a preliminary theory of the embryogenesis that explains these findings related to a persistence of the ventral portion of the neurenteric canal.

Conclusion.

These cases may represent a form of spinal cord malformation due to a persistent neurenteric canal and affecting notochord development that has rarely been described. Over more than one year of follow-up while managed conservatively, there was no evidence of neurologic dysfunction, so far supporting a treatment strategy of observation.

Keywords: notochord, neurenteric canal, split cord malformation, spinal dysraphism, tethered cord

Introduction and Historical Background:

Congenital abnormalities of the spinal cord can arise from abnormal development of the notochord (as in split cord malformations, SCM), or errors in neurulation (as in spina bifida and limited dorsal myeloschisis, LDM). This spectrum of malformations can result in chronic injury to the spinal cord and other neurologic sequelae, and are therefore often treated surgically.

By the end of the third week of development, the notochord induces overlying epiblast to form thickened neuroectoderm, the neural plate. Therefore, abnormalities of the notochord can result in malformations of the spinal cord and derivatives of the paraxial mesoderm. For example, Pang et al. proposed a “unified theory” of SCM embryogenesis that postulates an accessory neurenteric canal that bridges endoderm and ectoderm and bisects the developing notochord [1]. The neurenteric canal is a structure formed in notochordal development that is contiguous with the amniotic cavity through Hensen’s node, corresponding with the embryonic coccyx at its dorsal aspect [2]. The split notochord syndrome can encompass additional abnormalities, including a dorsal neurentric fistula [3]. Treatment of patients with these notochord-related malformations is tailored to the anatomical features and current/predicted future neurologic sequelae.

In recent years we have encountered two cases of a novel malformation that we believe to arise from errors in notochord formation, characterized by a cervicothoracic anterior neural stalk, arising from the spinal cord and traversing ventrally into the thorax, and joining an enteric duplication cyst that traverses via a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. This syndrome highly correlates with a theorized persistent neurenteric canal, thereby revealing the presence and location of this elusive embryonic structure. We report the clinical and radiographic characteristics of these cases, in addition to the postulated embryogenesis and our treatment strategy. Our experience with these patients yields insight into its neurodevelopmental origins and guides management for future patients.

Report of Cases:

We report two cases of patients in which we identified this novel form of notochord malformation. Informed consent was obtained for inclusion in the study.

Case 1:

A newborn baby girl of Caucasian (maternal) and mixed Caucasian-Native American (paternal) ancestry with a late prenatal diagnosis of right congenital diaphragmatic hernia, heterotaxy, azygous continuation of the inferior vena cava, asplenia, and duplicated left kidney and renal collection system was born at an outside hospital at 37 weeks gestational age. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 7 and 8, respectively. She had pulmonary hypoplasia and presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with respiratory distress.

During her hospital course, the congenital diaphragmatic hernia was repaired at 4 days of age, along with Ladd procedure without appendectomy. Following laparotomy, the small intestine, colon, and a small segment of liver were seen protruding into a right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and were reduced in the abdomen. A mediastinal cyst was visualized. At 13 days, an MRI was obtained for evaluation of continued respiratory distress and mediastinal cystic collections, and demonstrated a complex ventral spinal dysraphism at C5-7 with a neural stalk arising from the spinal cord. The morphology of the thecal sac was unusual, and had only a thin separation from the thoracic cysts. Given that a CSF leak would necessitate treatment, and in addition in order to assess the bony anatomy, we obtained a CT myelogram (Fig. 1a). There was no CSF communication visualized. At 33 days, surgical resection of the thoracic cysts via thoracotomy was pursued. Instillation of contrast agent into the thoracic cysts, followed by intraoperative fluoroscopy, did not identify any connection to the thecal sac. The cysts, which were contiguous, were resected entirely. Pathology was consistent with foregut duplication cyst. The thecal sac cyst was not resected or opened, and so its histologic characteristics could not be confirmed, and the neural stalk was not directly visualized. Trio whole exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray were unrevealing.

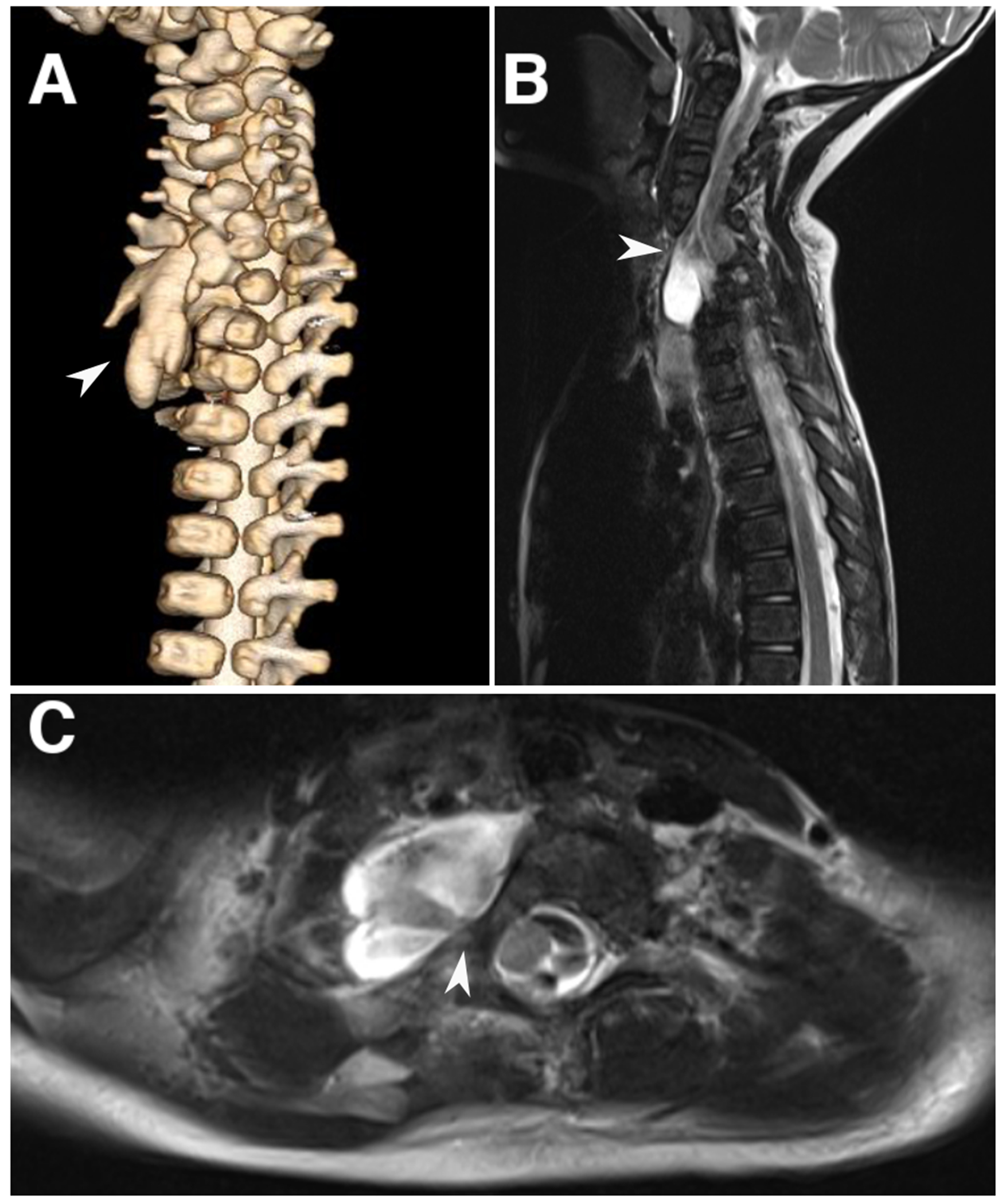

Fig. 1.

Spinal imaging for case 1. a) 3D reconstruction of CT myelogram at birth demonstrating a complex vertebral abnormality and dysplastic lobulated thecal sac protruding from the bony defect (arrowhead). b, c). Sagittal and axial T2-weighted MRI imaging at 3-year follow-up demonstrating the neural stalk coursing anteriorly and toward the right (arrowhead)

At follow-up at two years of age, the patient exhibited appropriate neurologic milestones (spoke 50 words, and was able to walk, run, and climb stairs independently). At 3 years and 7 months of age, her developmental trajectory progressed normally, and an MRI was obtained showing stable configuration of the spinal cord anomaly (Fig. 1b).

Case 2:

A newborn baby boy of Caucasian (maternal) and Native American (paternal) ancestry presented at 35 weeks gestational age, after emergent delivery following preterm labor in breech position and maternal Caesarian section scar dehiscence at an outside hospital. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 7 and 8, respectively. Gestational history was remarkable for prominent and dilated loops of small bowel on 23-week ultrasound examination. A fetal MRI was obtained which identified cervicothoracic junction vertebral abnormalities/Klippel-Feil anomaly and possible diastematomyelia, which was further characterized on a follow-up MRI at 32 weeks gestational age (Fig. 2b). A tubular structure in the right chest suggestive of an enteric duplication, and dilated bowel raising concern for jejunal atresia, were also seen. Other gestational events include maternal COVID-19 infection at 22 weeks gestational age.

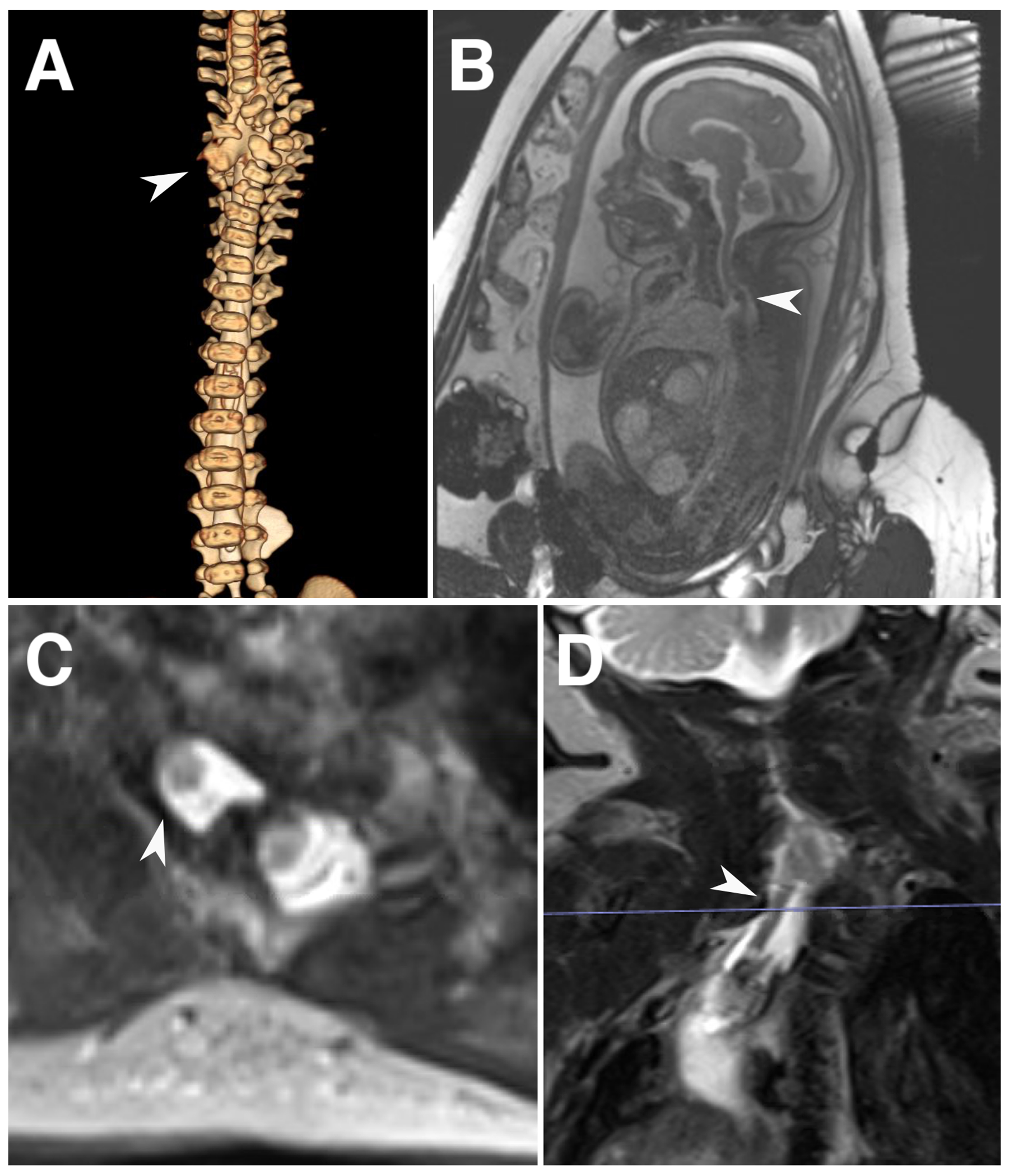

Fig. 2.

Spinal imaging for case 2. a) 3D reconstruction of CT myelogram at birth demonstrating a complex vertebral abnormality and thecal sac protruding from the bony defect (arrowhead). b) Fetal MRI in the sagittal plane demonstrating the diagnosis of a split cord malformation (arrowhead). c, d). Axial and coronal T2-weighted MRI imaging showing a dysplastic neural stalk directing anteriorly and toward the right side

Initial examination showed some transient respiratory distress, otherwise, he was well-appearing with normal neurologic examination including appropriate tone and reflexes. There were no clear cutaneous stigmata. MRI and a CT myelogram was obtained, demonstrating a ventrally directed neural stalk arising from the spinal cord, and ending in proximity to an abnormal tubular structure consistent with a thoracic enteric duplication. Cervicothoracic kyphoscoliosis, jejunal atresia, and microcolon were also noted (Fig. 2a,c–d). A CT myelogram did not show any CSF communication between the thecal sac and the enteric duplication, despite only a thin membrane separating the abnormal thecal sac from the thoracic cysts. In addition, there was a congenital porto-systemic shunt between the extrahepatic portal vein and the azygous vein.

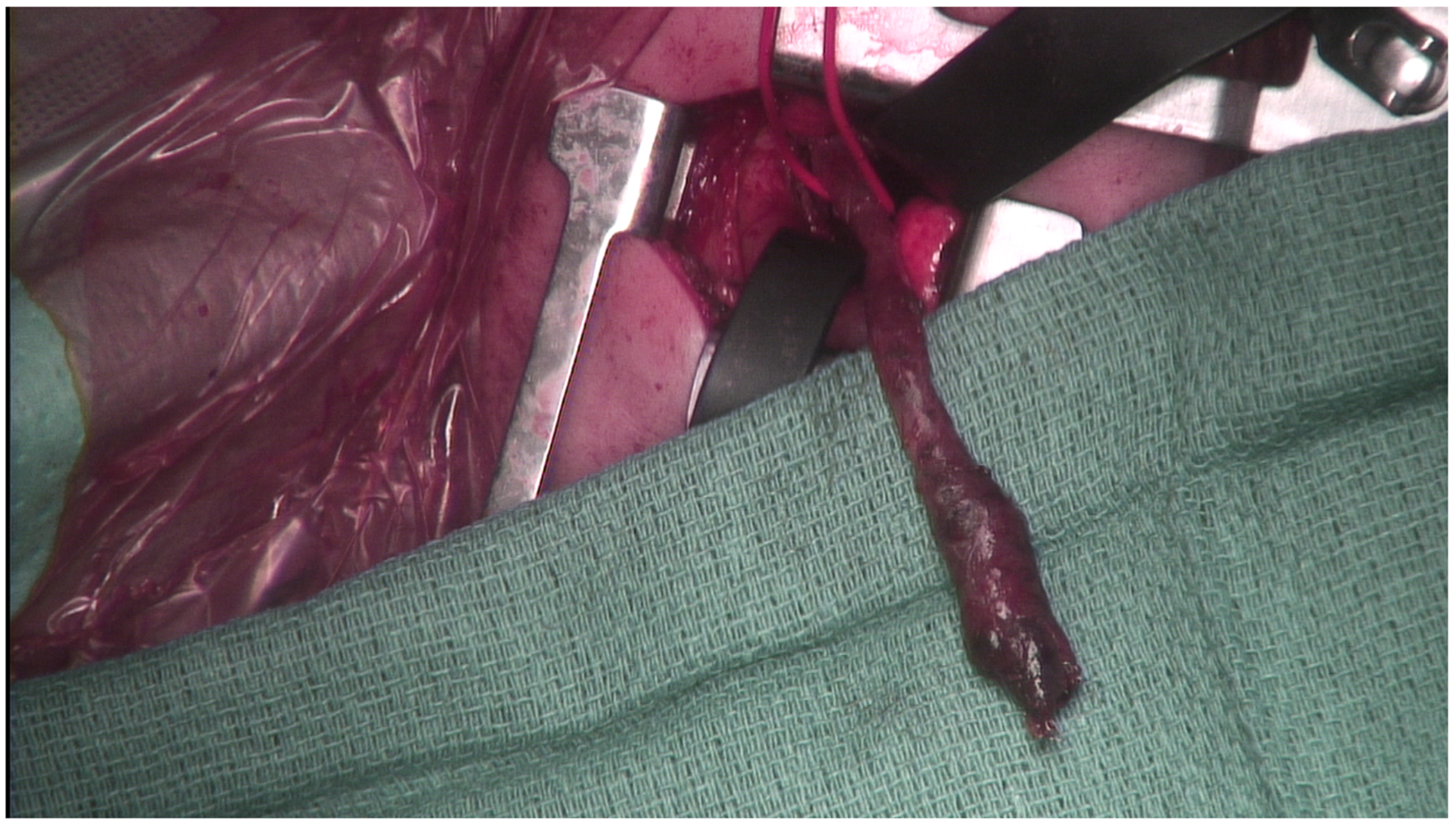

As in the first case, we advocated for conservative management in regards to the duplication of the spinal cord. At 10 days of age, surgical correction of suspected jejunal atresia and resection of enteric duplication cyst was pursued. Flexible bronchoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy were performed, which did not identify any communication between the trachea and esophagus with the thoracic duplication. Laparotomy/thoracotomy was performed which identified a large thoracoabdominal enteric duplication cyst arising from the mid-small bowel and terminating adjacent to the duplicated thecal sac (Fig. 3). This traversed a postero-medial right diaphragmatic defect, posterior to the liver and lateral to the hepatic veins. There was not a clear communication between the thecal sac and the cyst, but also no clear plane between the two tissues. Therefore, a small cuff was left on the thecal sac, while the rest of the cyst was resected en toto. A small dimple at the juncture of the thecal sac and the cyst remnant was observed and oversewn to prevent any intrathecal communication. The thecal sac cyst was not resected or opened. No intestinal atresia was found. The distal aspect of the neuro-enteric duplication communicated with the mid-small bowel, with associated partial obstruction of the bowel. The thoraco-abdominal enteric duplication was resected along with the short segment of jejunum where it communicated. The remaining jejunum was re-anastomosed to restore continuity. A Ladd procedure with appendectomy was performed to address the intestinal malrotation. The small right diaphragmatic hernia was repaired primarily and a gastrostomy tube was placed. Histologic analysis of the resected thoraco-abdominal cyst was consistent with foregut duplication cyst.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative photograph demonstrating the foregut duplication cyst (red loop) arising near the dysplastic thecal sac through a thoracotomy incision

The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by thoracotomy wound infection, respiratory failure which was attributed to restrictive lung disease of kyphoscoliosis and pulmonary hypoplasia related to congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and gut dysmotility and feeding intolerance, for which he required a prolonged hospital stay. Neurologic status has remained stable over more than one year of follow-up. Genetic workup, including rapid trio whole genome sequencing, showed a de novo missense variant of uncertain significance in the MINK1 gene.

Discussion

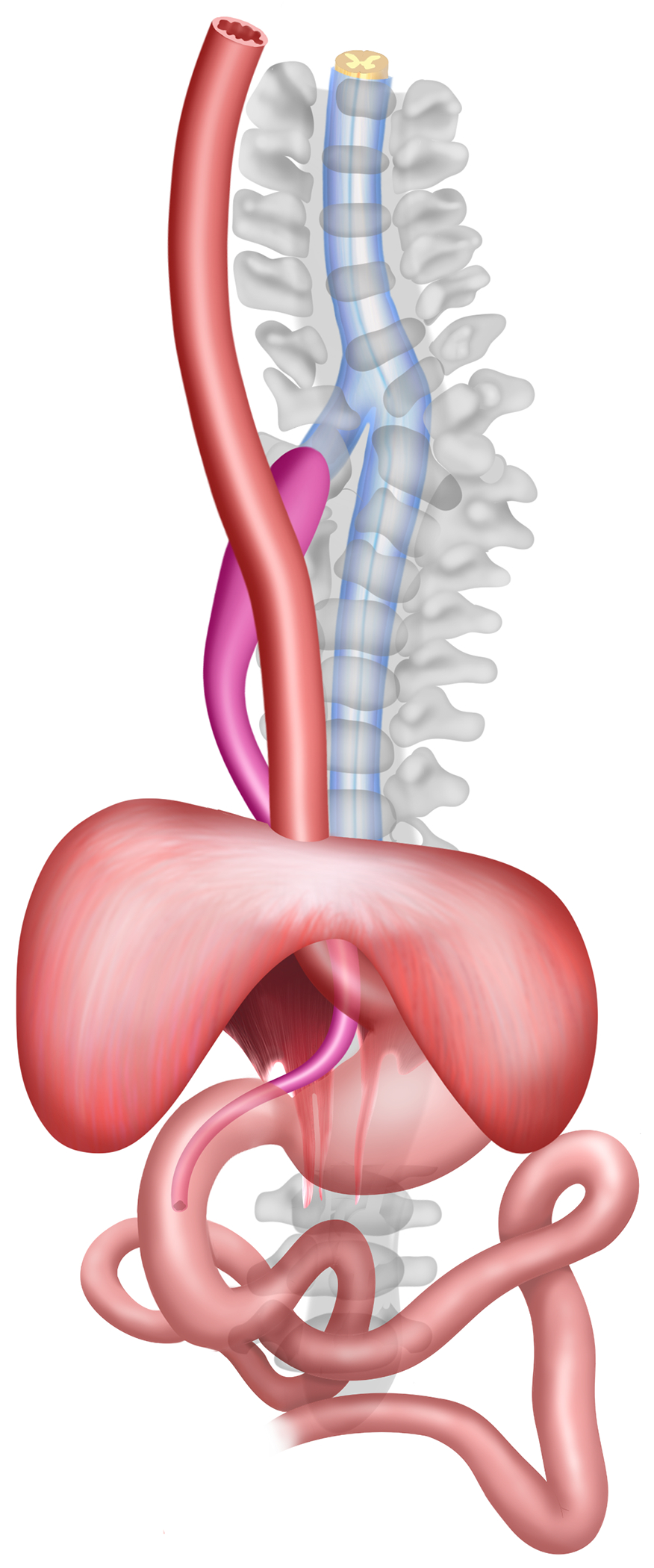

We describe a novel malformation defined by anteriorly directed “neural stalk” arising from the spinal cord, vertebral abnormality, foregut duplication cyst, and congenital diaphragmatic hernia in two patients (Fig. 4). Aside from the co-occurrence of this tetralogy of features, these spinal cord anomalies were morphologically unusual in several aspects that differentiate it from similar-appearing entities such as limited dorsal myeloschisis and split cord malformation. So far, there has been no evidence of neurologic dysfunction and they have been managed conservatively from the neurosurgical perspective.

Fig. 4.

Artist rendition of the tetralogy of anterior neural stalk arising from the spinal cord, vertebral abnormality, enteric duplication cyst, and diaphragmatic hernia

A review of the literature identified similar cases in the pediatrics literature but the full set of features were not described. In Pang’s series, one patient (Patient 1) had an anterior vertebral defect at C7 with an anteriorly clefted cervical cord, and duplicated duodenal cyst through a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Another patient (Patient 9) was found to have anterior-posterior orientation of a cervical hemicord, gut malrotation, and a cervical prevertebral cyst [1]. Recently, a case report by Ye et al. described a patient with anterior-posterior cervical “diplomyelia”, esophageal duplication, and cervical vertebral malformation, presenting with torticollis [4]. These cases may be related in etiology to the cases we reported, though with some differences. The route of the hemicord in Pang’s cases is unclear, as is any association with the reported prevertebral cyst. That patient presented with neurologic deficit and was treated surgically, at which point a fibrous septum was identified. In the second case, Ye et al. found that the anterior hemicord partially rejoined the posterior hemicord unlike in our cases, and reported the presence of a neurenteric cyst; it was thought that case resulted from notochord division from the neurenteric cyst. That patient also presented with torticollis. We present two cases that lack a potentially intervening neurenteric cyst and in which the anterior hemicord did not rejoin the posterior, signifying a different variety of spinal cord malformation. Our cases also did not have a neurologic deficit and therefore did not have surgical intervention for the spine, since there was no apparent associated tethering lesion. However, the striking similarities in the location and orientation of the split hemicord, as well as reported associations with gut abnormalities, suggest that these may represent cases with similar developmental origins as those that we have described.

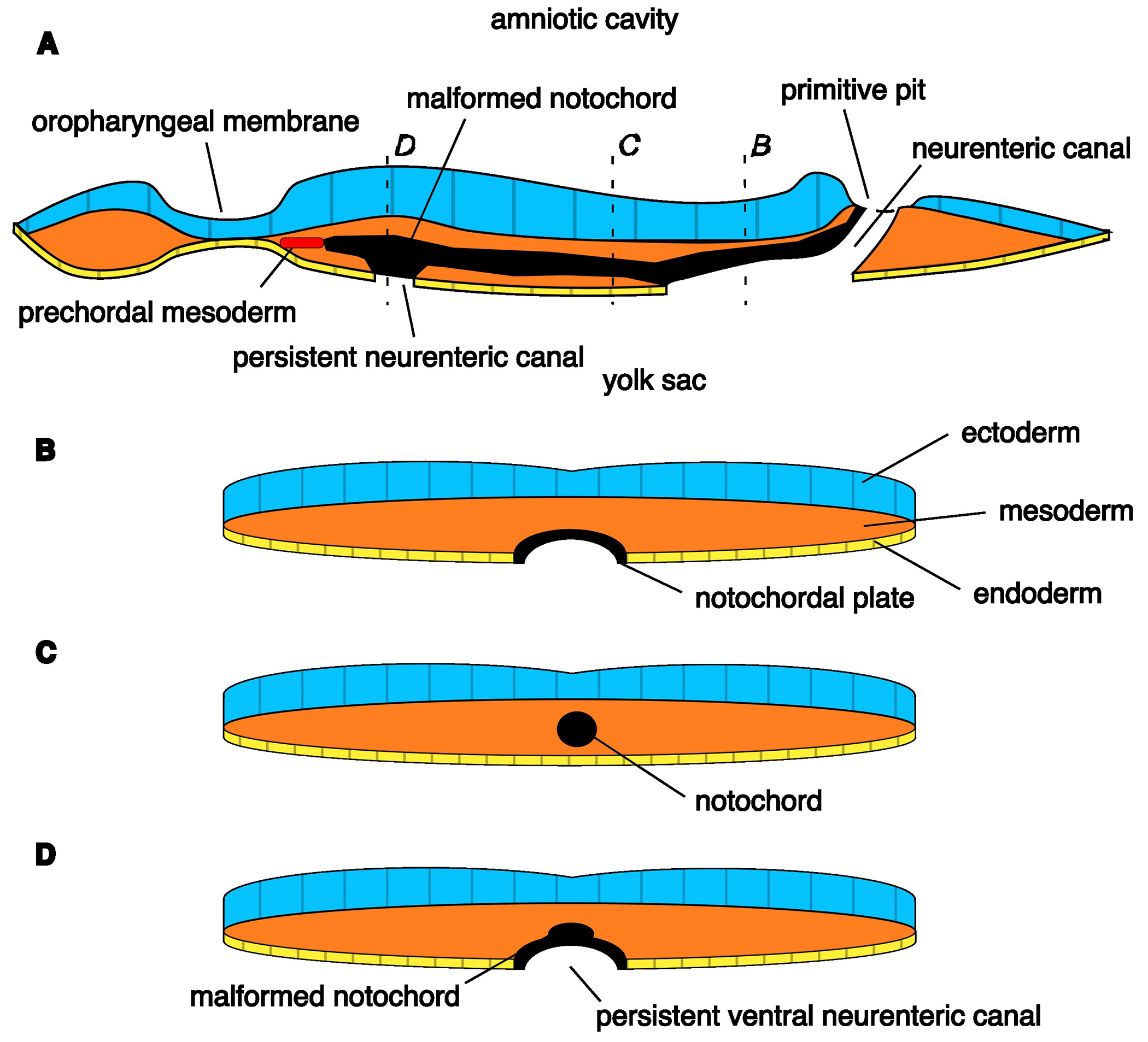

We hypothesize that the malformations observed in our cases originate from anomalies in notochord development, due to abnormal persistence of the ventral part of the neurenteric canal at the cervicothoracic junction. The formation of the notochord follows gastrulation and is a primary step in the patterning of the nervous system [5]. Along the midline, anterior to Hensen’s node, but limited posterior to the prechordal plate, invaginating mesenchymal cells form the notochordal process, which is then canalized through the primitive pit into the notochordal canal. The subchordal mesoderm forming the floor of the notochordal canal disintegrates; this establishes continuity between the amniotic cavity (though the primitive pit) and the yolk sac cavities via a “neurenteric canal” [2]. The canonical neurenteric canal connects at Hensen’s node (expected coccygeal location) dorsally but extends through the notochord cranially to communicate with the yolk sac at its ventral aspect following its formation from the notochordal canal. The notochordal process continues to fuse with the endoderm and intercalates into it, forming the notochordal plate. The plate proliferates and folds, starting cranially and progressing caudally, lifting off of the now-continuous layer of endoderm to form the definitive notochord. The notochord and other tissues also induce the formation of segmented paraxial mesoderm, forming the somites that contribute to the development of the vertebral column, and the neural tube then further develops into the structures of the central nervous system, including the brain and spinal cord.

Persistence of the neurentric canal would prevent the separation of the definitive notochord from the endoderm, forming a divergent notochordal process (Fig. 5). Failure of the divergent notochord to separate from the endoderm in the presence of the persistent neurenteric canal could lead to the proximity of the thecal sac to cysts of endodermal origin, as seen in our cases. The ventral orientation of the neural stalk can be explained by this failure of dorsal separation of the notochord, rather than an interruption in the notochord resulting in lateral splitting. Based on our cases and others through the literature, the persistent neurenteric canal exists around the cervicothoracic junction at the ventral aspect, although theoretically a similar occurrence could occur along the notochord [7]. Neurulation otherwise proceeds in both heminotochords. Maintenance of the abnormal notochord-endodermal connection, through which the vestigial hemicord and surrounding dura, and foregut duplication cyst form, could explain the defects in the surrounding mesenchymal tissue (i.e., vertebral anomaly and congenital diaphragmatic hernia), explaining the observed tetralogy.

Fig. 5.

Diagram of notochord malformation from persistent ventral neurenteric canal, approx. 17 day embryo. a) Sagittal section through the embryonic disc, as the notochord forms from the notochordal plate, in a cranial-to-caudal progression. The cranial side of the notochord has been formed. b) Transverse section through the marked plane, demonstrating the notochordal plate intercalated into the endoderm layer at its caudal aspect where it has yet to detach. c) Transverse section through the marked plane, demonstrating the formed notochord that has fully detached from the endoderm. d) Transverse section through the marked plane, demonstrating malformation of the notochord due to persistence of a ventral portion of the neurenteric canal, preventing full detachment from the endoderm and resulting in a ventrally-directed accessory notochordal process

In our proposed model, the neural stalk is a vestigial spinal cord-like tissue induced by an abnormal notochord, differentiating it from the fibroneural stalks seen for example in LDM, which are thought to be remnants of incomplete disjunction of the neuroectoderm and cutaneous ectoderm [8]. Consistent with this mechanism, the ventral location argues against a defect of primary neurulation; the neural stalk is similar in caliber to the normal spinal cord; and a central canal-like structure can be seen as the stalk splits from the spinal cord. This latter point also argues against similarity to nonterminal myelocystoceles, which can also present with neural stalks [9]. And, unlike in SCM, the spinal cord otherwise develops normally below the level of the anomaly, and no lower extremity neurologic deficits were noted. This model lends support to the existence of a transient neurenteric canal and furthermore localize it to the foregut-cervical spine interface. Other abnormalities of the neurenteric canal include neurenteric or neuroendodermal cysts, which can occur in intracranial and intraspinal locations. Most typically they occur as ventral, intradural, extramedullary cysts of the cervical, cervicothoracic, or upper thoracic spine [10]. The persistent neurenteric canal hypothesis explains this phenomenon; failure of separation of the notochord from the ventral endoderm resulting in ventral neurenteric cysts in the regions of the notochord. We also make note of shared Native American ancestry in both of our patients; however, it is unclear whether this is contributory to the malformation, and so far genetic studies have not identified a causative genetic etiology.

Treatment of congenital abnormalities of the spinal cord centers around the relief and prevention of chronic injury to the involved spinal cord, and the decision for surgical treatment depends on the natural history. Indications for operative intervention include new or progressive signs or symptoms (e.g. upper motor neuron symptoms, progressive scoliosis) or a secondary tethering lesion (e.g. filum lipoma) [11]. In dorsal abnormalities, e.g. spina bifida and LDM, more superficial lesions may also necessitate surgical correction [12]. In our cases, there was no clear septum or associated tethering lesion. The patients have no neurologic symptoms currently. Therefore we saw no benefit to intraspinal exploration, only addressing the concomitant digestive tract anomalies. So far, in more than three years follow-up for Case 1, and over one year of follow-up for Case 2, neurologic function has remained normal.

The cases we have observed may comprise a new class of spinal cord malformation with distinct embryology (notochordal malformation resulting from persistence of the neurenteric canal and failure to separate from the endoderm) with consequences for surgical management (non-tethering lesion). However, our observations are limited by currently short-term follow-up and no neurosurgical intervention thus far. Although we describe only two cases, suggestive reports in the literature may represent additional cases. Our preliminary theory of the embryogenesis of this malformation, although speculative based on the limited case series to date, explains the features that were observed. We hope to establish an awareness of this distinct form of spinal cord malformation, and as more cases are identified, the embryologic basis, genetics, natural history, and management of this syndrome can be further clarified.

Conclusion

We describe a novel syndrome of anterior neural stalk, vertebral abnormalities, thoraco-abdominal enteric duplication cyst, and diaphragmatic hernia that is proposed to represent a malformation arising from persistence of a neurenteric canal and failure to separate from the endoderm. No clear genetic contributors have been identified. These cases demonstrate the possibility of ventral malformations of the notochord, for which we have proposed a preliminary theory of embryogenesis.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge foremost our patients and their families to who this work is dedicated; and the Neonatal ICU, General Surgery, Neuroradiology, Medical Genetics, and Orthopedic Surgery services at the Boston Children’s Hospital who have been our collaborators in the care of these patients. Dr. Saibaba Guggilapu. MBBS, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, assisted with the illustration of Fig. 4.

Abbreviations:

- CT

computed tomography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- SCM

split cord malformation

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

JAC is a founder and holds an equity stake in Verge Genomics, and holds an equity stake in Gravity Medical Technology. JAC was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, 5 T32 AG 23480-17. JDB has an equity position in Treovir Inc. and is a member of the board of scientific advisors for Upfront Diagnostics, Centile Biosciences, and NeuroX1. The remaining authors have no pertinent conflicts of interest to declare.

Consent to publish:

The participants (patients’ parents) consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

References

- [1].Pang D, Dias MS, Ahab-Barmada M (1992) Split Cord Malformation: Part I: A Unified Theory of Embryogenesis for Double Spinal Cord Malformations. Neurosurgery 31: 451–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rulle A, Tsikolia N, de Bakker B, Drummer C, Behr R, Viebahn C (2018) On the Enigma of the Human Neurenteric Canal. Cells Tissues Organs 205: 256–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mathkour M, Scullen T, Huang B, Werner C, Gouveia EE, Abou-Al-Shaar H, Maulucci CM, Steiner RB, Hilaire H, Bui CJ (2021) Multistage surgical repair for split notochord syndrome with neuroenteric fistula: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr 27: 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ye DH, Kim DY, Ko EJ (2022) An Unusual Case of Torticollis: Split Cord Malformation with Vertebral Fusion Anomaly: A Case Report and a Review of the Literature. Children 9: 1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L, Pinter JD (2011) Chapter 4, Neuroembryology. In: Winn HR (ed) Youmans Neurological Surgery, 6th edn. Saunders/Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, pp 78–97 [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bentley JF, Smith JR (1960) Developmental posterior enteric remnants and spinal malformations: the split notochord syndrome. Arch Dis Child 35: 76–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chaurasia BD, Runwal PM, Dharker RS (1975) Evidence for normal cum accessory neurenteric canals in a human fetus. Acta Anat (Basel) 93: 574–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pang D, Zovickian J, Oviedo A, Moes GS (2010) Limited Dorsal Myeloschisis: A Distinctive Clinicopathological Entity. Neurosurgery 67: 1555–1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rossi A, Piatelli G, Gandolfo C, Pavanello M, Hoffmann C, Van Goethem JW, Cama A, Tortori-Donati P (2006) Spectrum of Nonterminal Myelocystoceles. Neurosurgery 58: 509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Santos de Oliveira R, Cinalli G, Roujeau T, Sainte-Rose C, Pierre-Kahn A, Zerah M (2005) Neurenteric cysts in children: 16 consecutive cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Pediatr 103: 512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Proctor MR, Scott RM (2001) Long-term outcome for patients with split cord malformation. Neurosurgical Focus FOC 10: 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pang D, Zovickian J, Wong S-T, Hou YJ, Moes GS (2013) Limited dorsal myeloschisis: a not-so-rare form of primary neurulation defect. Childs Nerv Syst 29: 1459–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]