Abstract

Elevated dopamine transmission in psychosis is assumed to unbalance striatal output through D1- and D2-receptor-expressing spiny-projection neurons (SPNs). Antipsychotic drugs are thought to re-balance this output by blocking D2 receptors (D2Rs). In this study, we found that amphetamine-driven dopamine release unbalanced D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ activity in mice, but that antipsychotic efficacy was associated with the reversal of abnormal D1-SPN, rather than D2-SPN, dynamics, even for drugs that are D2R selective or lacking any dopamine receptor affinity. By contrast, a clinically ineffective drug normalized D2-SPN dynamics but exacerbated D1-SPN dynamics under hyperdopaminergic conditions. Consistent with antipsychotic effect, selective D1-SPN inhibition attenuated amphetamine-driven changes in locomotion, sensorimotor gating and hallucination-like perception. Notably, antipsychotic efficacy correlated with the selective inhibition of D1-SPNs only under hyperdopaminergic conditions—a dopamine-state-dependence exhibited by D1R partial agonism but not non-antipsychotic D1R antagonists. Our findings provide new insights into antipsychotic drug mechanism and reveal an important role for D1-SPN modulation.

Antipsychotic drugs have been used to manage psychosis for over a half century. Early on, it was recognized that antipsychotics act on the dopamine system1. Specifically, a correlation between D2 receptor (D2R) binding and clinical potency led to a ‘dopamine hypothesis’ for schizophrenia and antipsychotic drug efficacy2,3. Therapeutic development ensued to fine-tune D2-like receptor signaling, yielding compounds with lower D2R affinities4, partial D2R agonism5, selectivity for specific D2-like receptors6 or specific signal transduction pathways7,8. Despite these advances, comparatively little progress has been made in the actual efficacy of antipsychotic treatments9. Given this discrepancy, there is an urgent need to understand the neural circuits that drive psychosis and how they are affected by antipsychotic drugs.

In schizophrenia, increased dopamine in the associative striatum is predicted to unbalance activity in the striatum’s principal output neurons: the D1R-expressing and D2R-expressing spiny-projection neurons (SPNs)10. Specifically, Gαs-coupled D1R signaling is thought to increase D1-SPN activity and Gαi-coupled D2R signaling to decrease D2-SPN activity11. D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs input to the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways, respectively, which converge to modulate basal ganglia output12. Theoretically, treatments that modulate either SPN type could normalize basal ganglia output, but the pharmacology of antipsychotics predicts that they preferentially modulate D2-SPNs. However, whether increased dopamine unbalances D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity and whether antipsychotic drugs preferentially modulate D2-SPNs have never been determined in vivo.

Presently, the variable efficacies and side-effect profiles of antipsychotic drugs are conceptualized by their binding to different brain receptors13. For instance, D2R binding is thought to confer antipsychotic activity, extrapyramidal symptoms and hyperprolactinemia, whereas serotonin receptor affinity confers atypicality and susceptibility to metabolic syndrome. However, this taxonomy provides limited insight into actual antipsychotic drug mechanism because these receptors are expressed throughout the brain. In fact, this receptor–symptom framework has, at times, misguided therapeutic development. For instance, it was predicted that mimicking the effects of D2R antagonism11 by inhibiting the enzyme PDE10A to increase the second-messenger cAMP in the striatum14 would alleviate psychosis. Although this is a logical strategy within a receptor–symptom framework, the selective PDE10 inhibitor MP-10 proved to be inefficacious in patients with schizophrenia15.

Because antipsychotics bind many different receptors, understanding how they modulate the function of neural circuits involved in psychosis could provide a more meaningful understanding of their mechanism. Due to its large-scale and cell-type specificity, in vivo imaging is well suited to provide these physiological insights. Using miniature microscopes to image D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ activity in vivo, we and others showed that D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs equally co-activate in spatially clustered ensembles and scale their activity with locomotor speed16,17. Conditions modeling the loss of dopamine in Parkinson’s disease disrupt both the levels and spatially clustered dynamics of D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity16. Notably, the extent to which treatments normalize these dynamics correlates with their clinical efficacy16. In the current study, we applied this same approach to understand the neural basis of psychosis and antipsychotic drug efficacy. Specifically, we imaged D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ activity in the dorsomedial striatum (DMS) during antipsychotic drug treatment under normal and hyperdopaminergic conditions. We initially compared three effective antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine and haloperidol) to the ineffective drug MP-10 (refs. 9,15). All four of the drugs suppressed amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion but differentially affected the levels, spatially clustered dynamics and amplitudes of D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ activity. Notably, drug effects on D2-SPN activity did not correlate with clinical efficacy. Rather, clinically effective drugs (but not MP-10) suppressed the levels and spatiotemporal de-correlation of D1-SPN activity, specifically during periods of rest after amphetamine treatment. These findings provide a novel explanation for antipsychotic drug efficacy.

Next, we tested contemporary antipsychotic drug candidates without affinity for any dopamine receptor. Xanomeline (M1/M4 cholinergic receptor agonist18), VU0467154 (M4 cholinergic receptor positive allosteric modulator (PAM)19) and SEP-363856 (trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and 5-HT1A agonist20) all suppressed amphetamine’s effects on the levels and spatiotemporal dynamics of D1-SPN activity during periods of rest, analogous to the other effective antipsychotics. Consistent with antipsychotic effect, chemogenetically inhibiting DMS D1-SPNs attenuated amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion, sensorimotor gating deficits and hallucination-like auditory perception21. Given the correlation between D1-SPN modulation and clinical antipsychotic efficacy, we evaluated three D1R-targeted compounds. A D1R partial agonist (SKF38393) and two D1R antagonists (SCH23390 and SCH39166) all attenuated amphetamine-driven D1-SPN hyperactivity during periods of rest. Notably, SKF38393 had a D1R stabilization-like profile that was consistent with D1R agonism under basal conditions and D1R antagonism under hyperdopaminergic conditions. These dopaminergic state-dependent effects on D1-SPN activity were shared by every effective antipsychotic that we tested, whereas the D1R antagonists exhibited no such state dependence, potentially explaining their therapeutic limitations22.

Altogether, our results highlight the power of a neural ensemble imaging approach for distinguishing between treatments for brain diseases and uncovering the basis of their efficacy. This approach outperformed basic behavioral correlates of drug efficacy and revealed pathological D1-SPN activity as a novel therapeutic target for psychosis. This new perspective and its underlying technical advances provide a framework for developing novel treatments for psychosis and the many other diseases for which striatal dysfunction is implicated.

Results

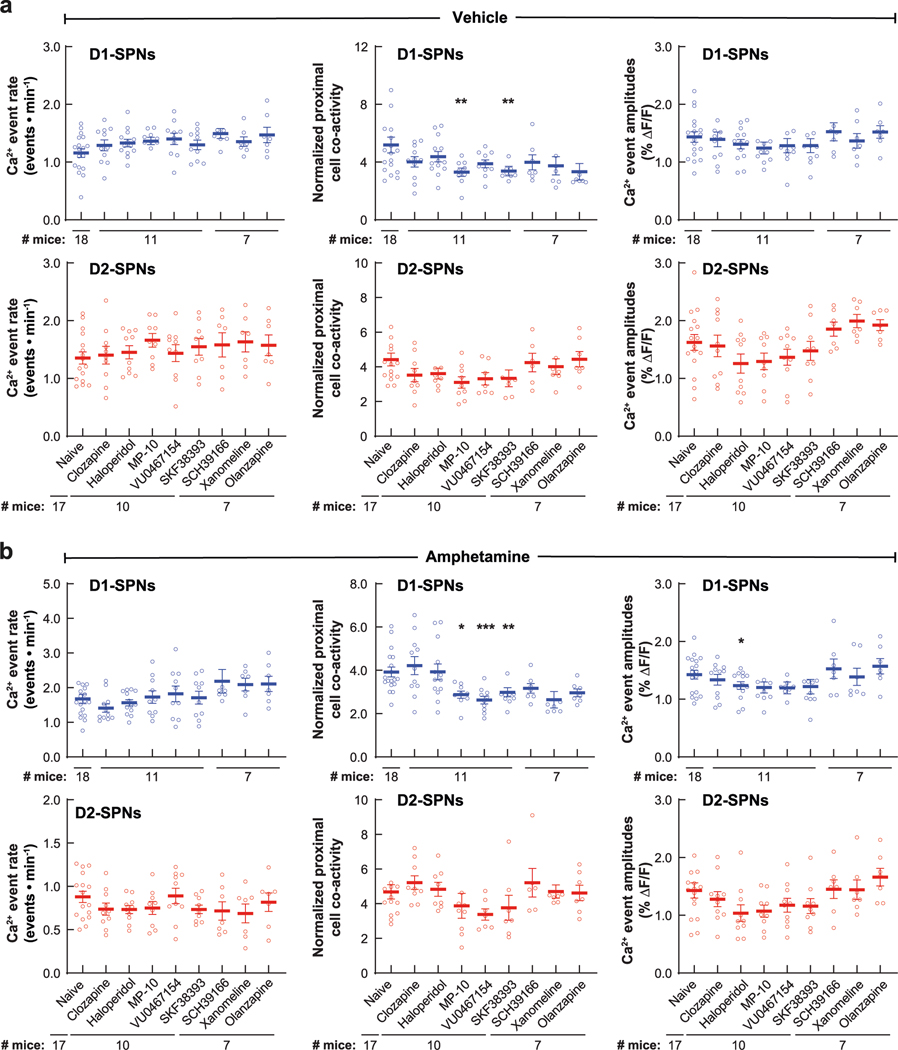

Distinct hyperdopaminergic D1-SPN and D2-SPN dynamics

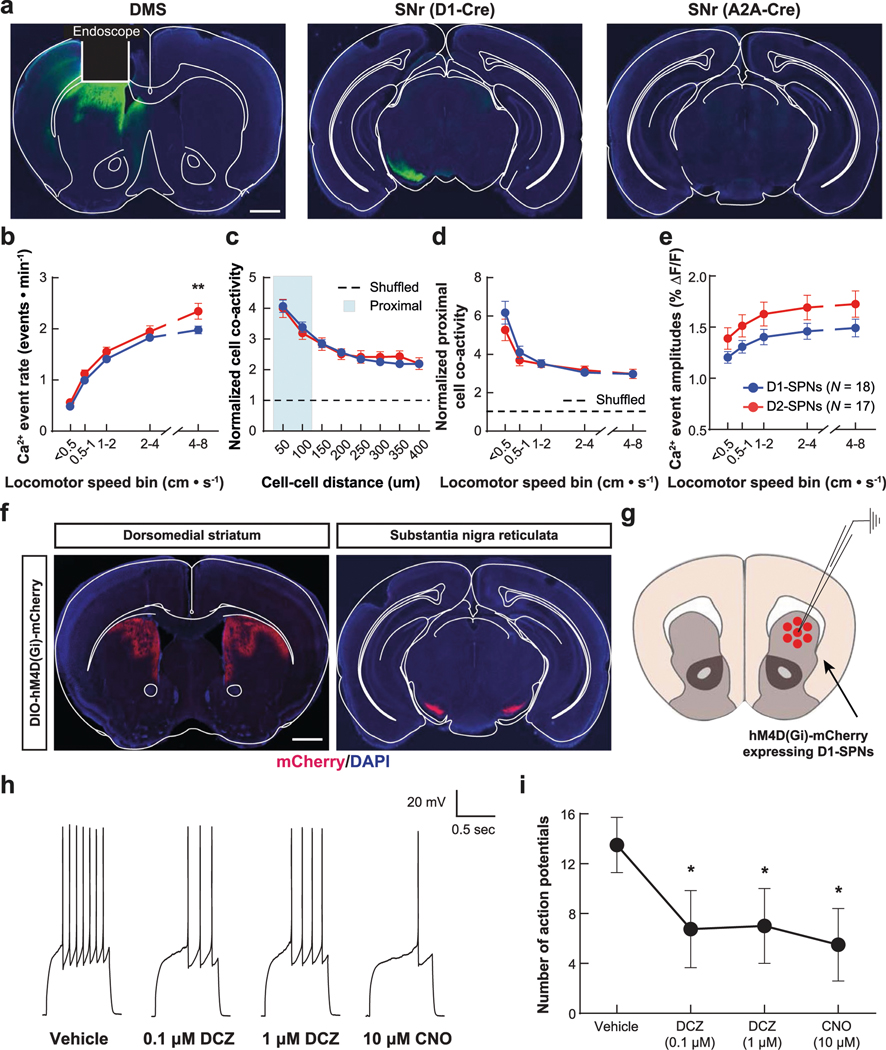

To record D1-SPN or D2-SPN activity in vivo, we virally expressed the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator GCaMP7f in the DMS of Drd1aCre (D1-Cre) or Adora2aCre (A2A-Cre) mice, respectively. We implanted an optical guide tube and microendoscope into the DMS and mounted the mice with a miniature fluorescence microscope (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). This approach allowed us to monitor Ca2+ activity in hundreds of individual D1-SPNs or D2-SPNs as mice freely explored an open field arena (Fig. 1b; 224 ± 11 D1-SPNs per mouse over 279 imaging sessions and 183 ± 12 D2-SPNs per mouse over 256 sessions; mean ± s.e.m.). D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs had similar Ca2+ event rates that increased with locomotor speed to a slightly greater degree in D2-SPNs (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Consistent with previous findings16, both SPN types exhibited spatiotemporally coordinated patterns of activity, particularly among proximal (25–125 μm) neurons (Extended Data Fig. 1c). In contrast to event rates, proximal SPN co-activity decreased with increased locomotor speed (Extended Data Fig. 1d). The amplitudes of Ca2+ transients were slightly, but not significantly, larger in D2-SPNs than D1-SPNs and increased with locomotor speed in both SPN types (Extended Data Fig. 1e). To account for their speed dependence, we subsequently analyzed these Ca2+ dynamics as a function of each mouse’s running speed.

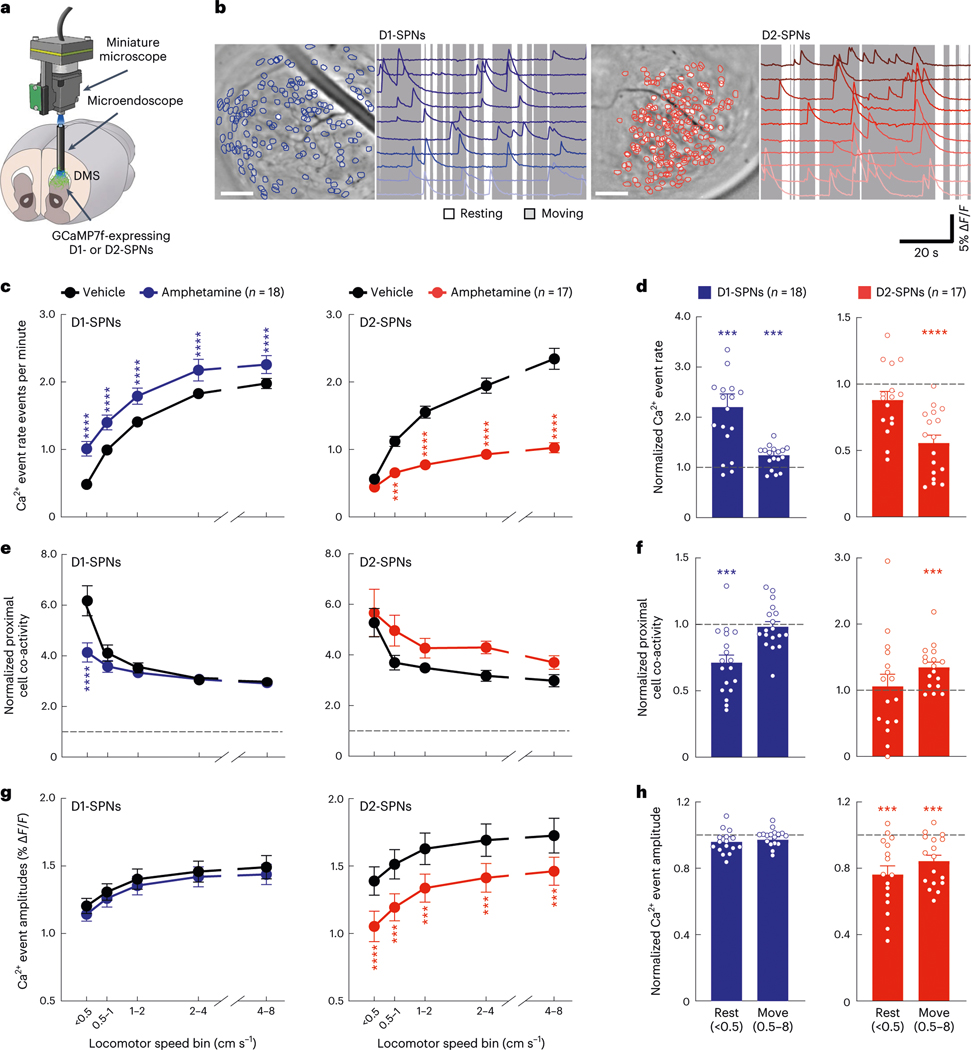

Fig. 1 |. Effects of amphetamine treatment on D1-SPN/D2-SPN Ca2+ activity in freely behaving mice.

a, We used a miniature microscope and microendoscope to image Ca2+ activity in D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs by expressing GCaMP7f in the DMS. b, Cell centroid locations overlaid on mean fluorescence images of DMS and example Ca2+ activity traces from D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs in representative D1-Cre (left) and A2A-Cre (right) mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. c,d, Effects of vehicle or amphetamine on D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ event rates across increasing locomotor speed bins (c) or averaged across resting (< 0.5 cm s−1) and moving (0.5–8 cm s−1) speed bins (d) and normalized to mean values after vehicle-only treatment. e,f, Effects of vehicle or amphetamine on the co-activity of proximal D1-SPN and D2-SPN pairs (25–125-μm separation), normalized to temporally shuffled comparisons, across different speed bins (e) or averaged across resting and moving speed bins (f) and normalized to mean values after vehicle-only treatment. g,h, Effects of vehicle or amphetamine on D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ event amplitudes across different speed bins (g) or averaged between resting and moving speed bins (h) and normalized to mean values after vehicle-only treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 18 D1-Cre and n = 17 A2A-Cre mice; ****P < 10−4 and ***P < 10−3 for comparison to vehicle treatment; two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test for c,e,g; Wilcoxon, two-tailed signed-rank test for d,f,h). Exact P values for these and all other analyses are in the Supplementary Table. All n values reported within the actual figures or legends refer to the number of mice.

To determine how dopamine affects these dynamics, we treated mice with amphetamine, which causes dopamine to efflux through its membrane transporter23. Consistent with excitatory D1R and inhibitory D2R modulation, amphetamine treatment increased D1-SPN and decreased D2-SPN activity levels (Fig. 1c). These effects were also speed dependent, with greater D1-SPN activation during periods of rest and more D2-SPN suppression during movement (Fig. 1d). Amphetamine also differentially altered the spatiotemporal dynamics of D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs in a speed-dependent manner, disrupting proximal co-activity in D1-SPNs at rest and augmenting it during movement in D2-SPNs (Fig. 1e,f). Finally, amphetamine significantly reduced the Ca2+ transient amplitudes of D2-SPNs but not D1-SPNs during both rest and movement (Fig. 1g,h). Because these amplitude effects were independent of running speed, we subsequently analyzed them across all speed bins.

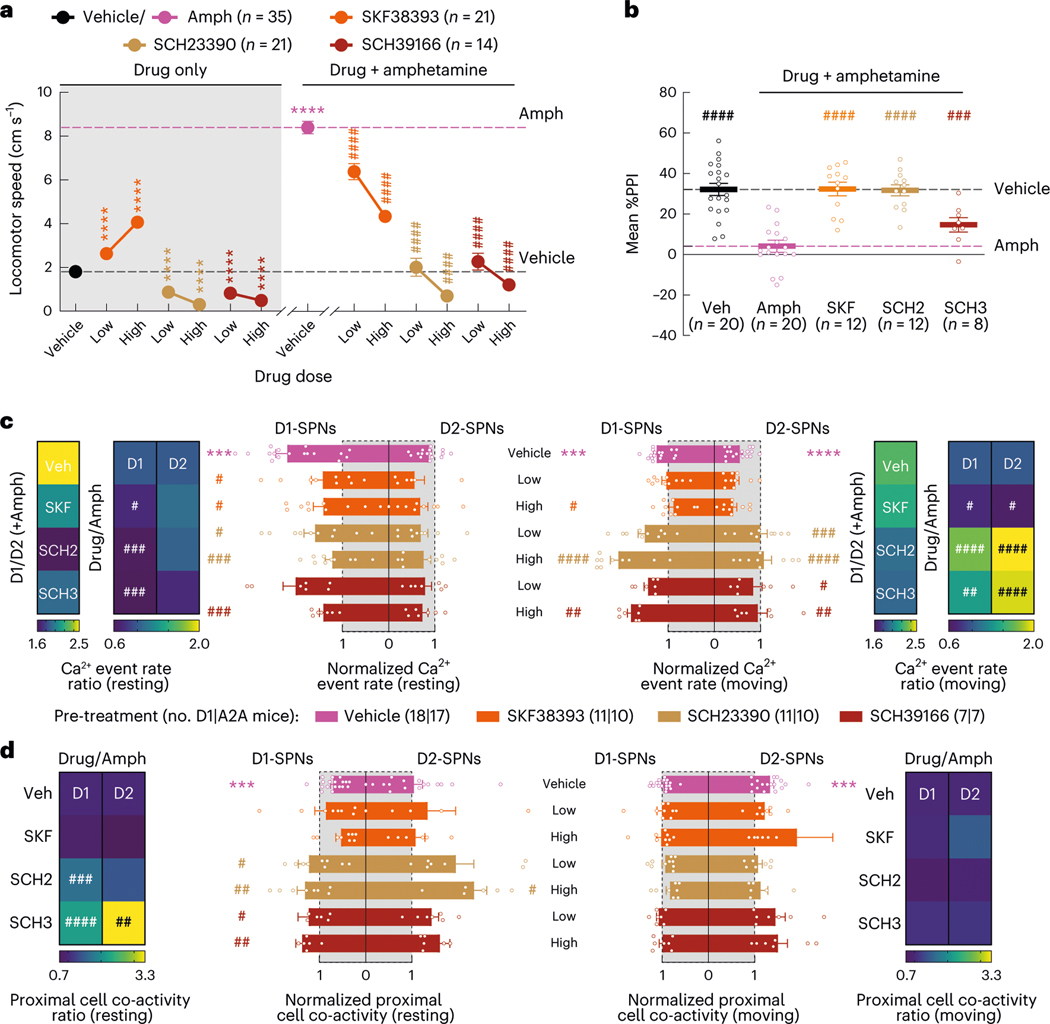

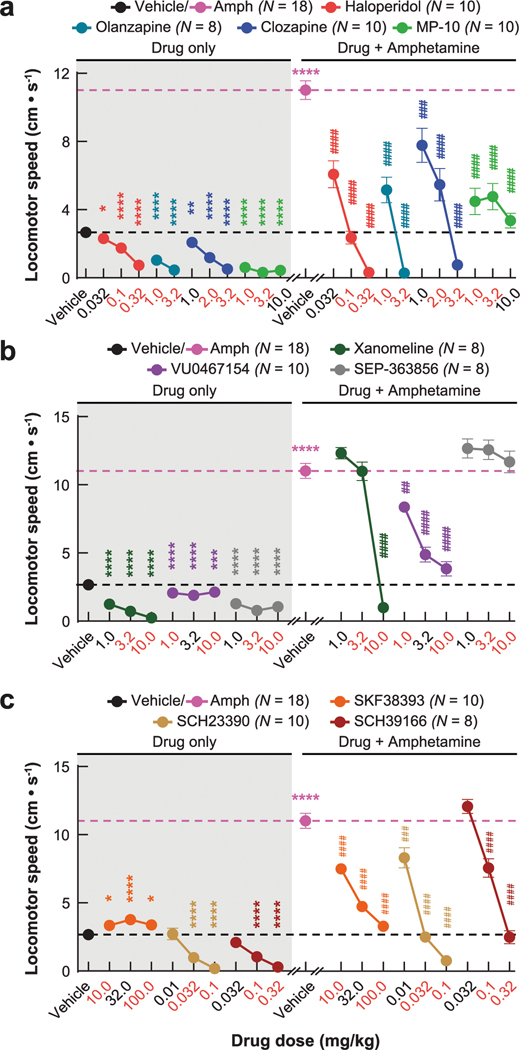

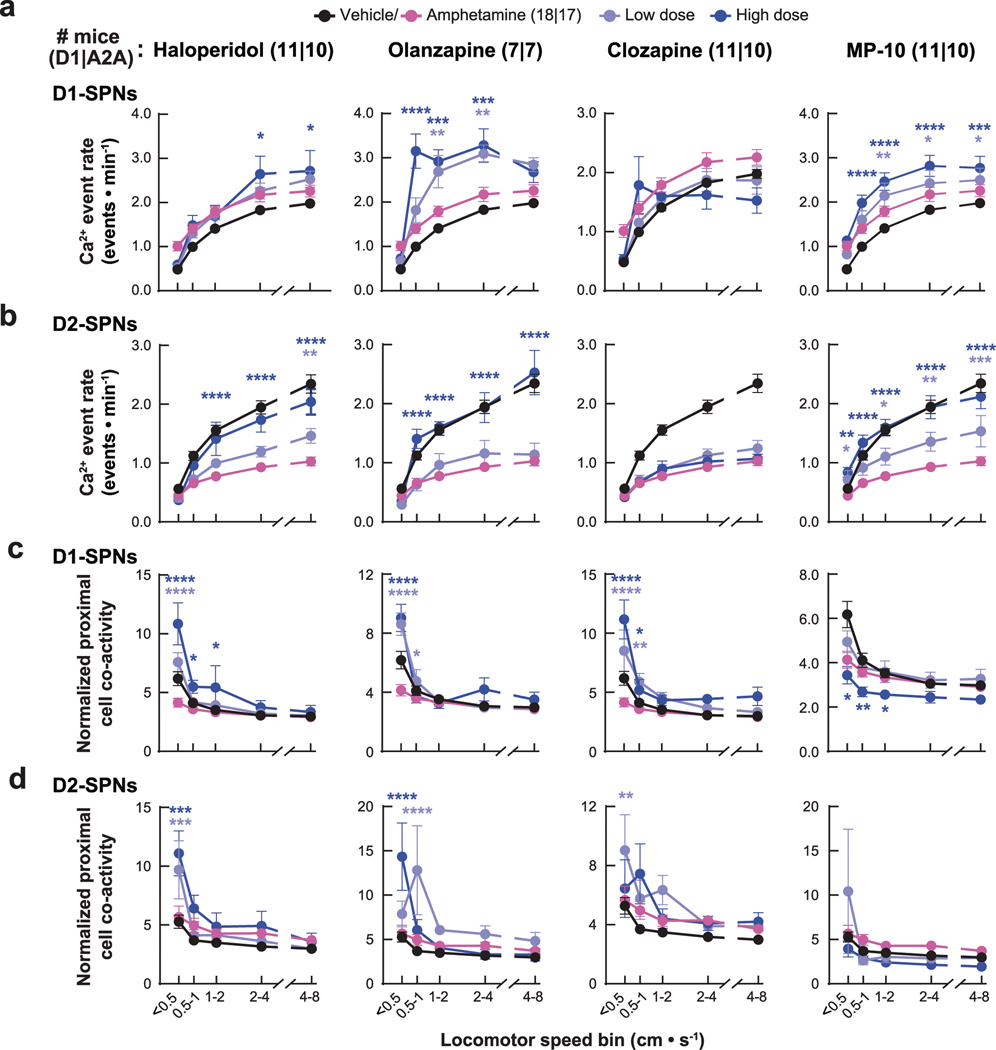

The neural correlates of clinical antipsychotic efficacy

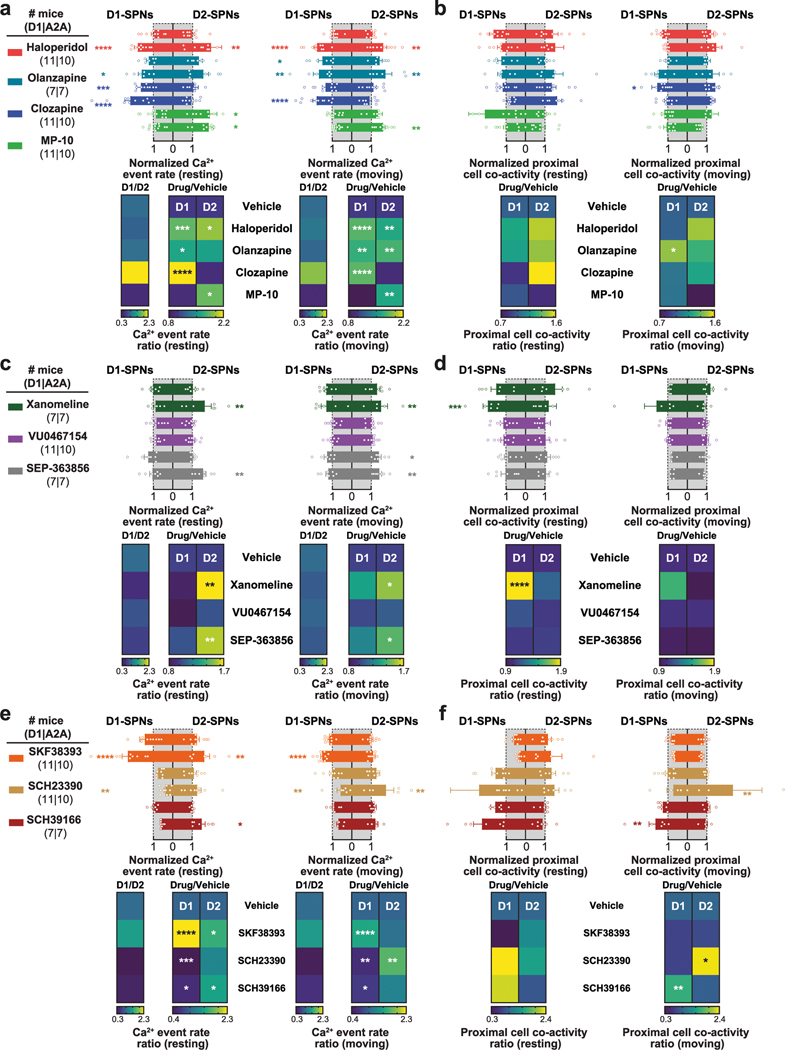

Next, we asked how these dynamics were impacted by four drugs with different clinical profiles. Specifically, we compared haloperidol, an efficacious antipsychotic with significant motor side effects, to clozapine and olanzapine, efficacious atypical antipsychotics with fewer motor side effects, and MP-10, a drug candidate that failed in clinical trials for schizophrenia8,24. To identify appropriate doses of each drug, we examined locomotor activity in C57BL/6J mice after treatment with different doses of each drug and selected low and high doses with similar effects on basal and amphetamine-driven locomotion for imaging experiments (Extended Data Fig. 2a). We recorded behavior and D1-SPN or D2-SPN Ca2+ activity after treatment with vehicle or a low/high dose of each drug followed by amphetamine (Fig. 2a). All four drugs inhibited locomotor activity before amphetamine treatment and suppressed amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion (Fig. 2b). High doses of the clinically effective antipsychotics, but not MP-10 or vehicle, also corrected amphetamine-driven deficits in sensorimotor gating as measured by pre-pulse inhibition (PPI; Fig. 2c–e)25.

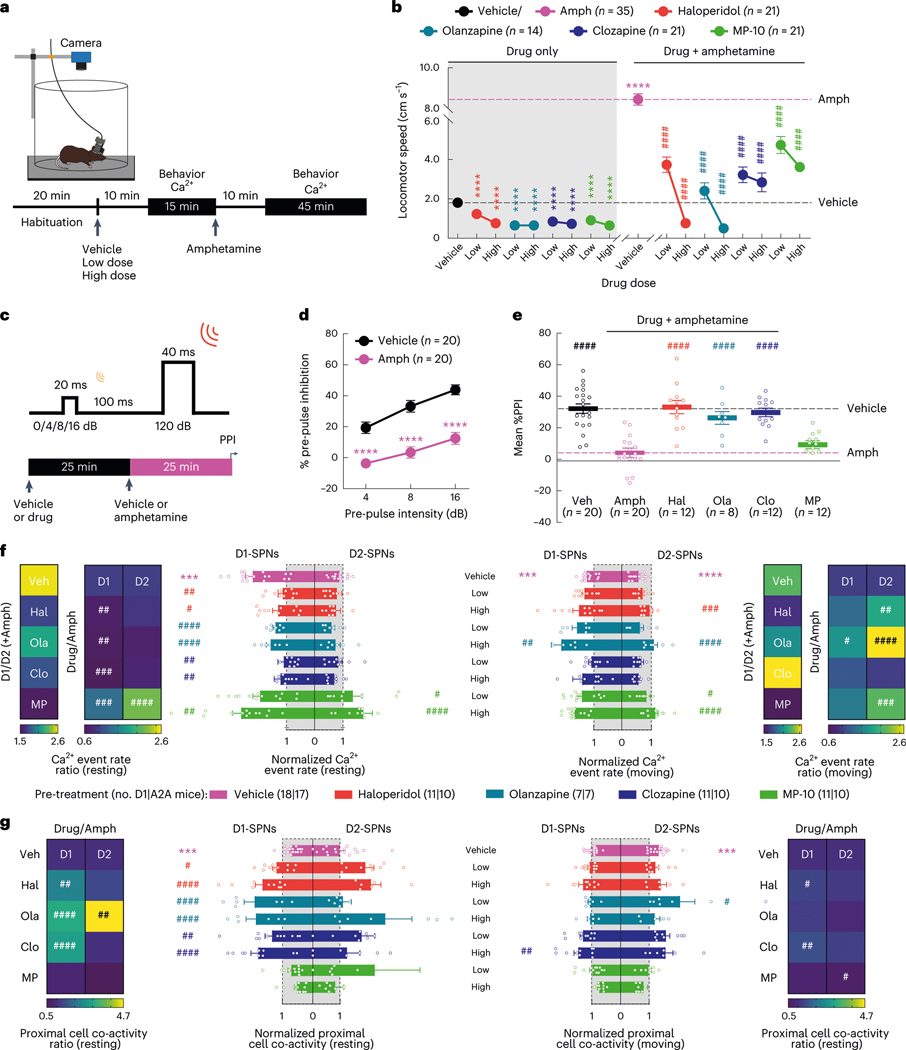

Fig. 2 |. Effects of antipsychotic drugs or a failed drug candidate on behavior and D1-SPN/D2-SPN dynamics.

a, Schematic of recording behavior and Ca2+ activity. b, Mean ± s.e.m. locomotor speed during the 15-min recording period after vehicle or antipsychotic drug treatment and the 45-min recording period after amphetamine treatment (****P < 10−4 for comparison to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). c, We injected vehicle or antipsychotic drug 25 min before amphetamine treatment and measured PPI 25 min after amphetamine treatment. d,e, Mean ± s.e.m. percent PPI of startle response at three pre-pulse intensities after vehicle or amphetamine-only treatment (d) and averaged across all pre-pulse intensities after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment (e) (****P < 10−4 for comparison to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; two-way ANOVA (d) and one-way ANOVA (e) with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). f, Mean ± s.e.m. D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ event rates after vehicle or low/high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to values after vehicle-only treatment during periods of rest (left) and movement (right). Heat maps depict the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity (D1/D2), normalized to the ratio after vehicle-only treatment, or the vehicle-normalized D1-SPN or D2-SPN event rate after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to the corresponding value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment (Drug/Amph). g, Mean ± s.e.m. proximal co-activity of D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs after vehicle or low/high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to values after vehicle-only treatment during periods of rest (left) and movement (right). Heat maps depict the vehicle-normalized D1-SPN or D2-SPN proximal co-activity after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to the corresponding value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment (for f,g; ***P < 10−3 compared to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4, ###P < 10−3, ##P < 10−2 and #P < 0.05 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test).

Despite their similar effects on basal and amphetamine-driven locomotion, each drug differently affected D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity. At baseline (before amphetamine treatment), the effective antipsychotics (but not MP-10) increased D1-SPN activity during both rest and movement, whereas every drug besides clozapine increased D2-SPN activity with variable specificity for locomotor state (Extended Data Figs. 3a and 4a,b). These changes resulted in clozapine increasing the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity, which was reduced by MP-10 and unaffected by haloperidol or olanzapine under baseline conditions (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The drugs had minimal effects on the spatiotemporal dynamics and amplitudes of D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ events except for MP-10, which reduced event amplitudes in both SPN types (Extended Data Figs. 3b, 4c,d and 5a). Under hyperdopaminergic conditions, every drug attenuated the increase in the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity at rest, but they did so in different ways. The effective antipsychotics selectively attenuated D1-SPN hyperactivity, whereas MP-10 increased activity in both SPN types (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 6a). During periods of movement, only olanzapine increased D1-SPN activity levels, and every drug but clozapine attenuated amphetamine-driven D2-SPN hypoactivity (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 6b). The effective antipsychotics (but not MP-10) also attenuated the disruption of D1-SPN spatiotemporal dynamics at rest (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 6c). No drug alleviated the heightened spatiotemporal coordination of D2-SPNs during movement or their reduced Ca2+ transient amplitudes after amphetamine treatment (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Figs. 5a and 6d).

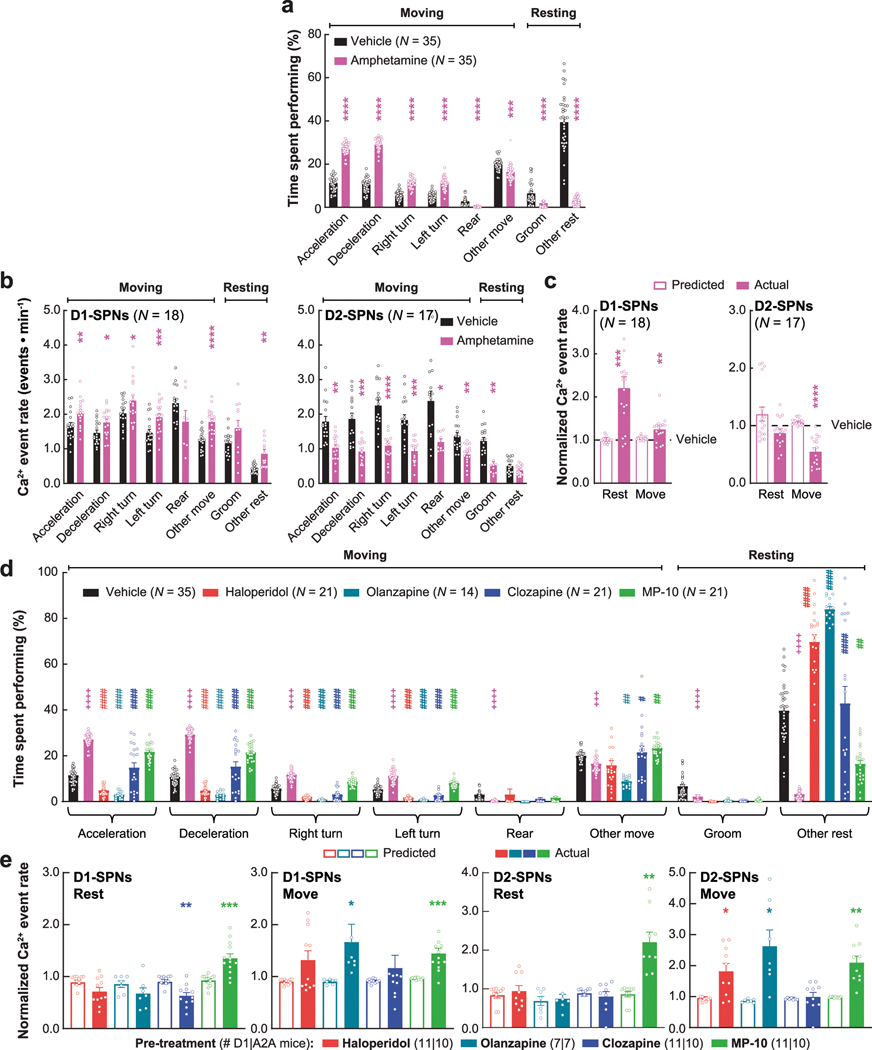

To determine whether the ordering of drug treatments contributed to our observations, we compared these dynamics after vehicle-only or vehicle + amphetamine treatment across all sessions. Except for slight variability in the proximal co-activity and event amplitudes in D1-SPNs, these metrics were largely unchanged after vehicle or amphetamine treatment in each experimental block (Extended Data Fig. 7). Therefore, the ordering of drug treatment did not appear to contribute to the observed differences between each drug’s effect on D1-SPN and D2-SPN dynamics. Changes in behavioral state not accounted for by our analysis could also have contributed these differences. To address this possibility, we used automated pose estimation and behavior classification (Mouse Action Recognition System (MARS)26) to discern how neural activity related to specific behaviors under each treatment condition. Beyond decreasing rest and increasing movement, amphetamine treatment increased periods of acceleration, deceleration and turning but decreased grooming and rearing (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Although these different behaviors were associated with different SPN activity levels, amphetamine increased D1-SPN activity levels during every behavior except grooming and rearing, which were less frequent after amphetamine, and decreased D2-SPN activity levels during every movement-associated behavior (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Using the SPN activity levels associated with each behavior after vehicle-only treatment, we calculated a predicted Ca2+ event rate during rest and movement by taking the product of the observed event rate during each behavior, multiplied by the fraction of time spent engaged in that behavior after amphetamine treatment. Grouping these predicted rates according to resting (groom or other rest) or moving behaviors (everything else) showed that changes in the time spent engaged in specific behaviors did not account for the experimentally observed changes in D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity after amphetamine (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Likewise, antipsychotic drug/candidate pre-treatment also altered the time spent engaged in specific behaviors after amphetamine, but these changes also did not fully explain the effects of drug pre-treatment on the observed changes in D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e).

Overall, the three clinically efficacious drugs attenuated amphetamine-driven disruption of D1-SPN ensemble dynamics, hyperlocomotion and deficits in sensorimotor gating. By contrast, the inefficacious drug MP-10—even though it attenuated amphetamine-driven D2-SPN hypoactivity and hyperlocomotion—exacerbated amphetamine-driven D1-SPN hyperactivity and failed to normalize sensorimotor gating. Our imaging results did not depend on the ordering of drug treatment or specific changes in behavior and suggest that normalizing D1-SPN dynamics may be more important than D2-SPN dynamics for antipsychotic effect.

Non-dopaminergic drugs normalize D1-SPN dynamics

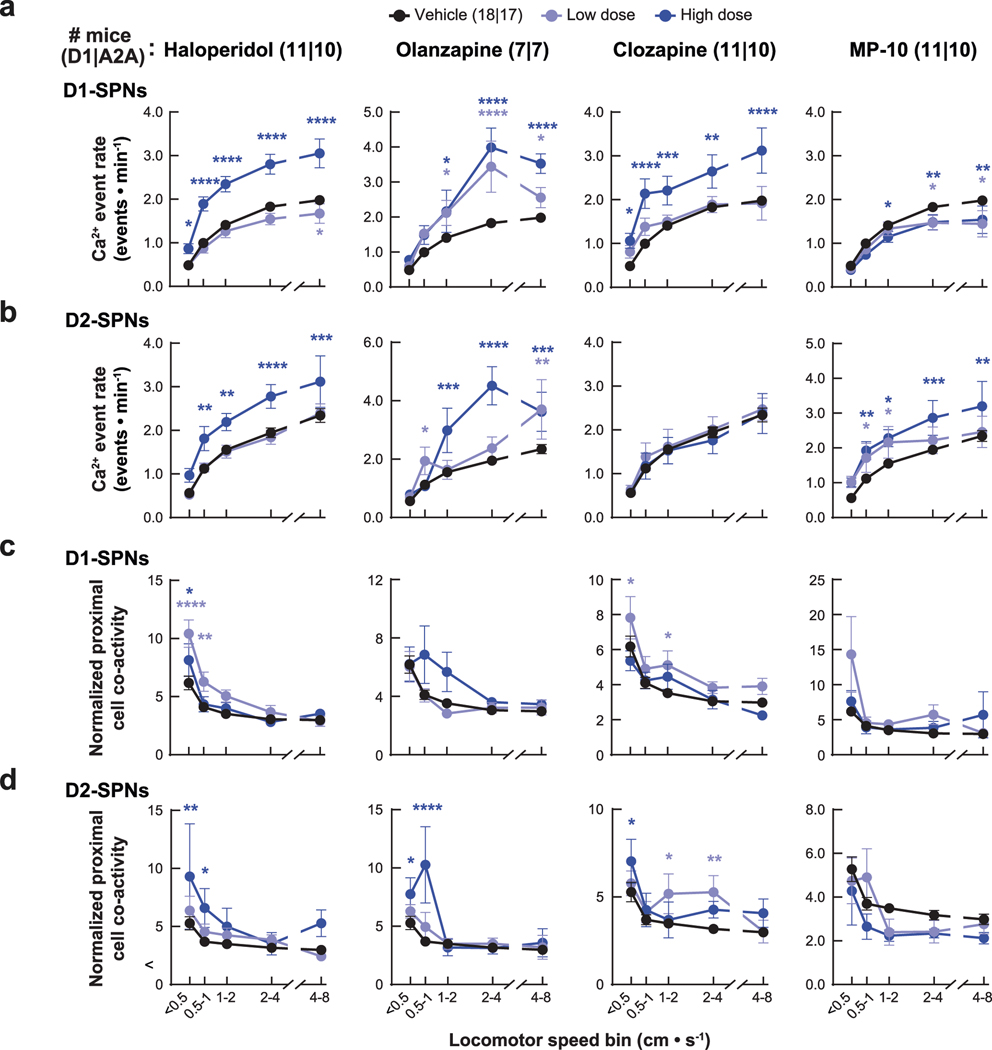

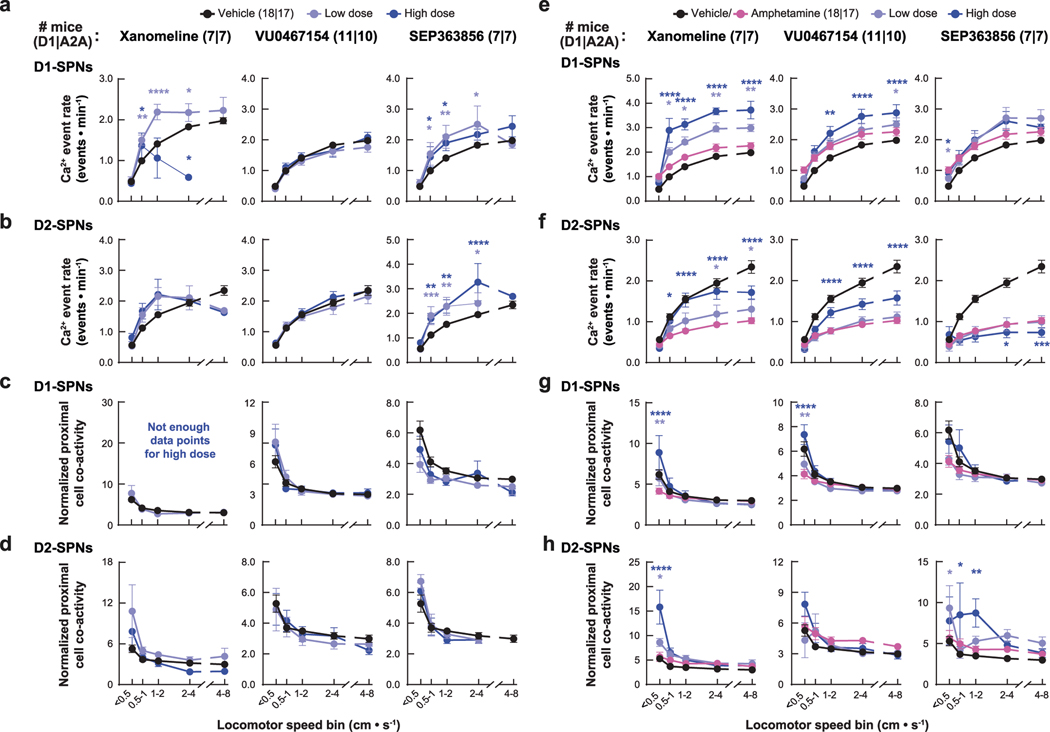

Several recent antipsychotic drug candidates, such as xanomeline and SEP-363856, have demonstrated clinical efficacy without binding to dopamine receptors18,20. Although these drugs lack dopamine receptor affinity, they may still act on SPNs. For instance, the cholinergic agonist xanomeline could engage Gαi-coupled M4 receptors in D1-SPNs and Gαq-coupled M1 receptors in both SPN types27, whereas SEP-363856 could engage TAAR1 to modulate dopamine turnover in axon terminals28. However, whether these drugs modulate the dynamics of D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs in vivo has not been determined. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of these drugs and an M4 PAM (VU0467154 (ref. 19)) on D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity under normal and hyperdopaminergic conditions.

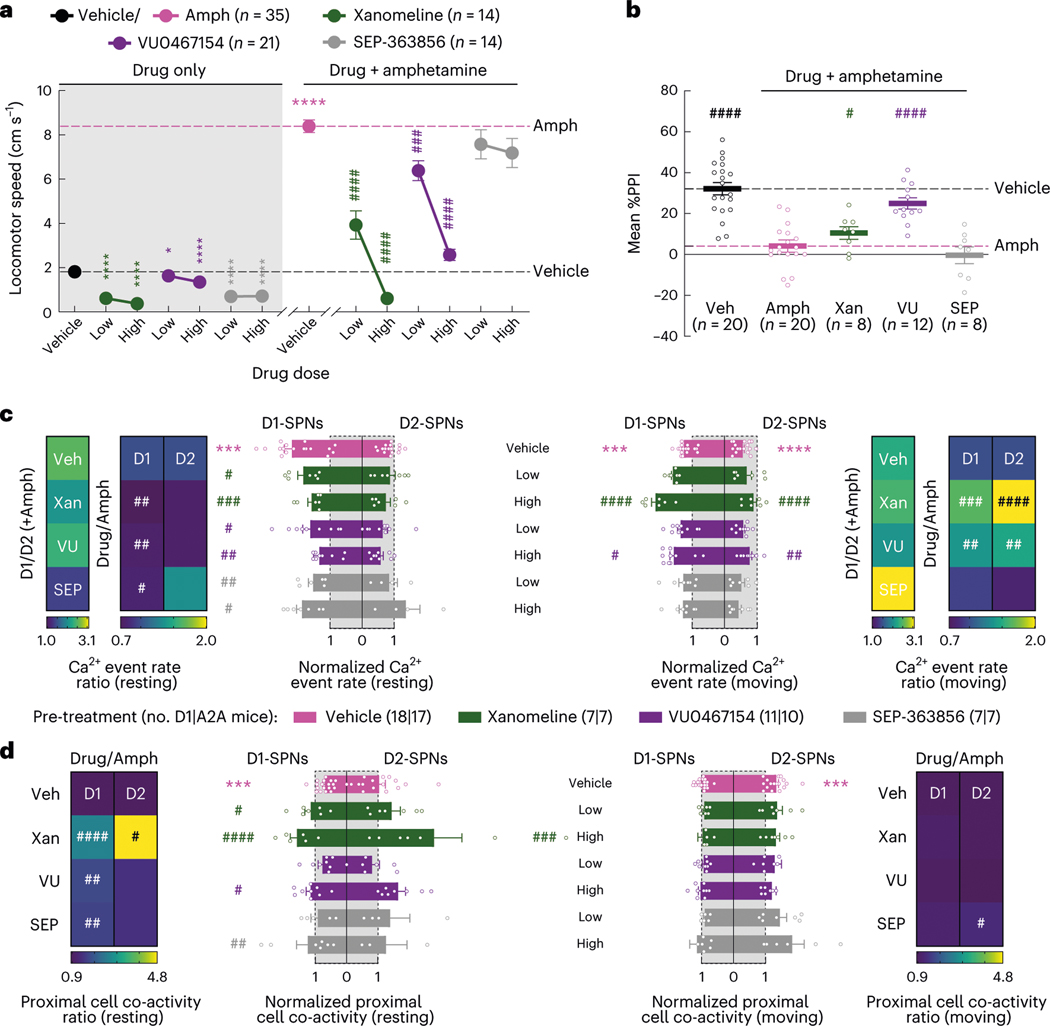

Behaviorally, xanomeline and VU0467154 decreased locomotion under both normal and hyperdopaminergic conditions and prevented amphetamine-driven PPI deficits; by contrast, SEP-363856 decreased basal locomotion but did not reverse amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion or PPI deficits (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2b). These observations were consistent with previous studies using these drugs19,29,30. Under baseline conditions, none of the drugs affected D1-SPN activity levels, but xanomeline and SEP-363856 increased D2-SPN activity (Extended Data Figs. 3c and 9a,b). Xanomeline increased the spatially clustered co-activity of D1-SPNs and the amplitude of Ca2+ transients in both SPN types, whereas VU0467154 reduced transient amplitudes in both SPN types (Extended Data Figs. 3d, 5b and 9c,d).

Fig. 3 |. Effects of drugs lacking dopamine receptor affinity on behavior and D1-SPN/D2-SPN dynamics.

a, Mean ± s.e.m. locomotor speed during the 15-min recording period after vehicle or drug treatment and the 45-min recording period after amphetamine treatment (****P < 10−4 and *P < 0.05 for comparison to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4 and ###P < 10−3 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). b, Mean ± s.e.m. percent PPI, averaged across all pre-pulse intensities after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment (####P < 10−4 and #P < 0.05 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). c, Mean ± s.e.m. D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ event rates after vehicle or low/high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to values after vehicle-only treatment during periods of rest (left) and movement (right). Heat maps depict the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity (D1/D2), normalized to the ratio after vehicle-only treatment, or the vehicle-normalized D1-SPN or D2-SPN event rate after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to the corresponding value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment (Drug/Amph). d, Mean ± s.e.m. proximal co-activity of D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs after vehicle or low/high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to values after vehicle-only treatment during periods of rest (left) and movement (right). Heat maps depict the vehicle-normalized D1-SPN or D2-SPN proximal co-activity after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to the corresponding value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment. ***P < 10−3 compared to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4, ###P < 10−3, ##P < 10−2 and #P < 0.05 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidakʼs multiple comparison test.

Under hyperdopaminergic conditions, all three compounds attenuated the spatially de-correlated D1-SPN hyperactivity caused by amphetamine treatment during periods of rest (Fig. 3c,d and Extended Data Fig. 9e,g). In doing so, every drug decreased the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity at rest (Fig. 3c). During periods of movement, xanomeline and VU0467154 increased activity in both SPN types, whereas SEP-363856 had no effects on activity in either SPN type (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 9e,f). Xanomeline also increased the spatially clustered dynamics of D2-SPN activity during periods of rest, but not movement, when these dynamics were heightened by amphetamine (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 9g,h). Xanomeline was the only drug that increased the amplitudes of D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ transients, thereby attenuating the amphetamine-driven decrease in D2-SPN event amplitudes (Extended Data Fig. 5b). In summary, these effective antipsychotic drug candidates normalized resting D1-SPN dynamics under hyperdopaminergic conditions, with very little effect on D1-SPN activity under baseline conditions.

D1-SPN inhibition normalizes amphetamine-driven behaviors

Given that every clinically efficacious drug we tested attenuated, and the ineffective drug MP-10 exacerbated, dopamine-driven D1-SPN hyperactivity, we asked whether inhibiting D1-SPNs was sufficient to suppress psychosis-related behaviors. We virally expressed the inhibitory DREADD (DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry) or a control fluorophore (DIO-mCherry) in the DMS of D1-Cre mice31 (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 1f). The DREADD agonist deschloroclozapine32 (DCZ) suppressed current-induced D1-SPN spiking in brain slices from hM4D(Gi)-expressing mice (Extended Data Fig. 1g–i). In vivo DCZ treatment (10 μg kg−1) attenuated amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion and PPI deficits in hM4D(Gi)-expressing, but not mCherry-expressing, mice (Fig. 4b,c), although these effects were less robust than systemic antipsychotic treatment.

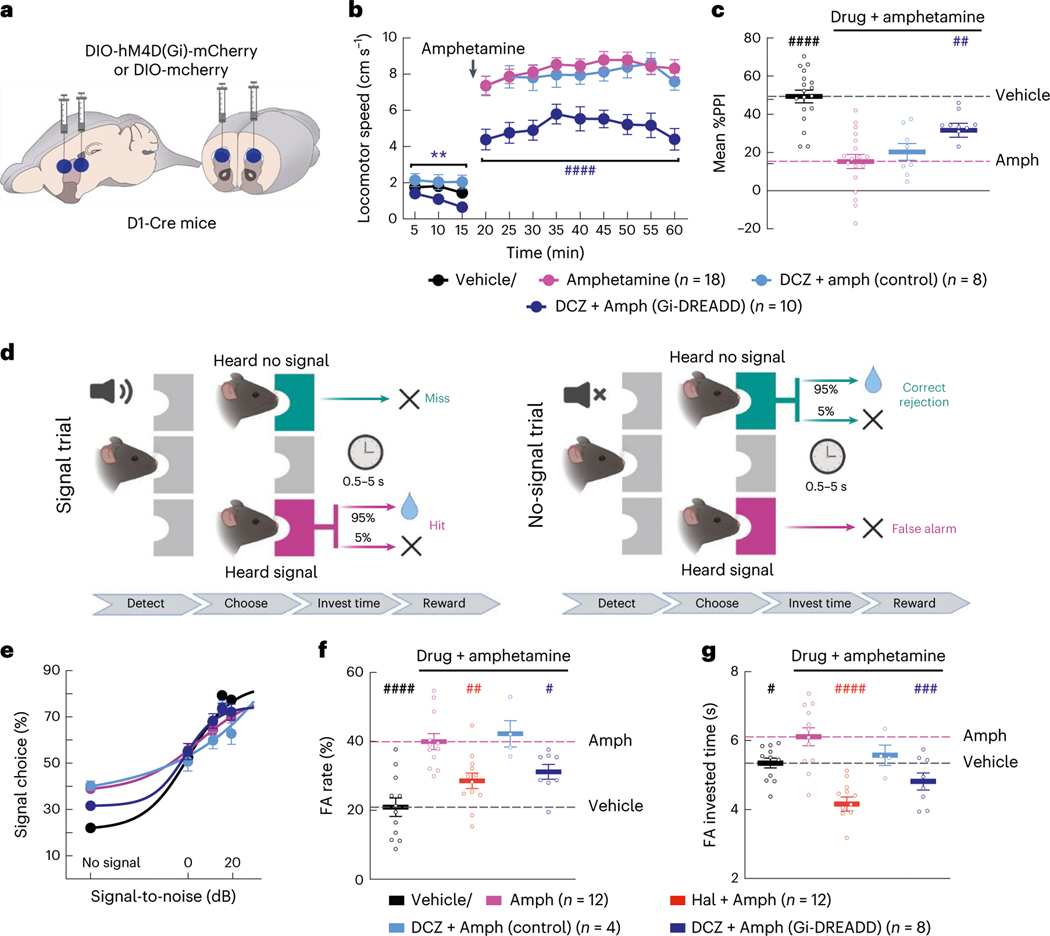

Fig. 4 |. Inhibiting D1-SPNs is sufficient to rescue amphetamine-driven behaviors.

a, We injected DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry or DIO-mCherry virus bilaterally at two sites in the DMS of D1-Cre mice. b,c, Treatment with the DREADD agonist DCZ reduced baseline locomotion and attenuated amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion (b) and PPI disruption (c) in DREADD, but not mCherry-expressing, mice (**P < 10−2 for comparison to vehicle-only treatment; ####P < 10−4 and ##P < 10−2 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; two-way ANOVA (b) and one-way ANOVA (c) with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). d, Schematic of hallucination-like perception assay in which mice initiate trials by nose poking in the center port and choosing the left or right reward port depending on whether a tone is or is not embedded in the background white noise (created with BioRender). e–g, Psychometric function of the percentage of ‘heard signal’ choice (e), false alarm (FA) rate (f) and FA investment times (g) after vehicle or amphetamine treatment with or without haloperidol or DCZ pre-treatment. Data in e are mean ± 1 s.d. binomial confidence intervals and mean ± s.e.m. in f and g (####P < 10−4, ###P < 10−3, ##P < 10−2 and #P < 0.05 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test).

Next, we asked if D1-SPN inhibition was sufficient to normalize amphetamine-driven hallucination-like auditory perceptions (HALIPs)21. We trained mice in a two-choice auditory discrimination task to self-report the presence or absence of an acoustic stimulus embedded in white noise (Fig. 4d). Consistent with previous studies, mice correctly reported having heard the acoustic stimulus more often when the signal-to-noise ratio of the stimulus increased (Fig. 4e). On ‘no signal’ trials, mice occasionally chose the ‘heard signal’ port. The amount of time invested at the incorrectly chosen port on these ‘false alarm’ trials is interpreted to reflect the mouse’s confidence in its decision. Notably, the frequency of high-confidence false alarms, or HALIPs, correlates with self-reported hallucinations in humans performing a similar version of this task, suggesting that they reflect overlapping neural processes21. Consistent with this idea, amphetamine treatment increased the rate of HALIPs in mice, and haloperidol pre-treatment blocked this effect (Fig. 4e–g). Likewise, chemogenetic D1-SPN inhibition blocked amphetamine-driven HALIPs as measured by false alarm rate and investment time (Fig. 4f,g). These results indicate that the suppression of D1-SPN activity is sufficient to reduce the effects of excess dopamine on psychosis-related behaviors, consistent with antipsychotic effect.

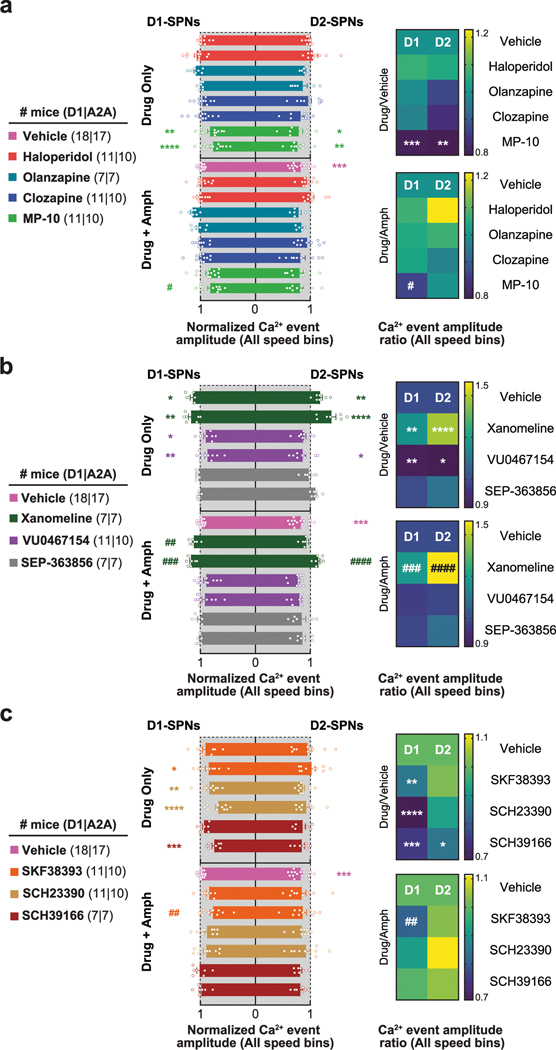

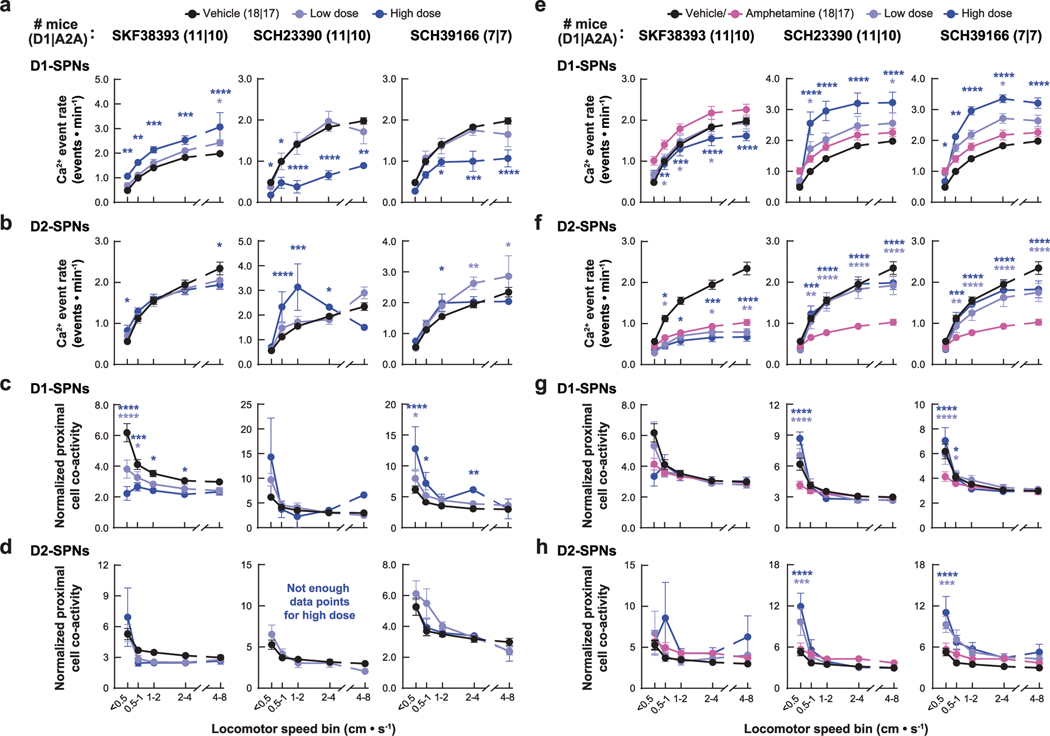

State-dependent D1-SPN modulation via D1Rs

Given the association between normalizing D1-SPN dynamics and antipsychotic effect, we tested three drugs predicted to decrease D1-SPN activity under hyperdopaminergic conditions: the D1R partial agonist SKF38393 (1) and the D1R antagonists SCH23390 (2) and SCH39166 (3). Consistent with previous studies33–35, SCH23390 and SCH39166 decreased, whereas SKF38393 increased, locomotor speed under baseline conditions, and all three attenuated amphetamine-driven locomotion and sensorimotor gating deficits (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2c). Administered alone, SKF38393 increased, whereas SCH23390 and SCH39166 decreased, D1-SPN activity during periods of rest and movement, and all three drugs increased D2-SPN activity during either rest or movement (Extended Data Figs. 3e and 10a,b). The net of these effects resulted in the partial agonist increasing and antagonists decreasing the ratio of D1/D2-SPN activity (Extended Data Fig. 3e). SCH23390 and SCH39166 also increased proximal cell co-activity during movement in D2-SPNs and D1-SPNs, respectively, and all three drugs reduced the amplitude of Ca2+ transients in D1-SPNs but not D2-SPNs (Extended Data Figs. 3f, 5c and 10c,d).

Fig. 5 |. Effects of D1R-targeted compounds on behavior and D1-SPN/D2S-PN dynamics.

a, Mean ± s.e.m. locomotor speed during the 15-min recording period after vehicle or drug treatment and the 45-min recording period after amphetamine treatment (****P < 10−4 for comparison to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). b, Mean ± s.e.m. percent PPI, averaged across all pre-pulse intensities after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment (####P < 10−4 and ###P < 10−3 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test). c, Mean ± s.e.m. D1-SPN and D2-SPN Ca2+ event rates after vehicle or low/high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to values after vehicle-only treatment during periods of rest (left) and movement (right). Heat maps depict the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity (D1/D2), normalized to the ratio after vehicle-only treatment, or the vehicle-normalized D1-SPN or D2-SPN event rate after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to the corresponding value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment (Drug/Amph). d, Mean ± s.e.m. proximal co-activity of D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs after vehicle or low/high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to values after vehicle-only treatment during periods of rest (left) and movement (right). Heat maps depict the vehicle-normalized D1-SPN or D2-SPN proximal co-activity after vehicle or high dose of drug + amphetamine treatment, normalized to the corresponding value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment (***P < 10−3 compared to vehicle treatment; ####P < 10−4, ###P < 10−3, ##P < 10−2 and #P < 0.05 compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test).

Under hyperdopaminergic conditions, all three compounds selectively attenuated D1-SPN hyperactivity during periods of rest, although only SCH23390 and SCH39166 also prevented the loss of spatially clustered D1-SPN dynamics (Fig. 5c,d and Extended Data Fig. 10e,g). During rest, the net effect of each drug treatment was to lower the ratio of D1-SPN/D2-SPN activity compared to vehicle + amphetamine treatment, exclusively through D1-SPN inhibition (Fig. 5c). During movement, SKF38393 also decreased D1-SPN activity, whereas SCH23390 and SCH39166 increased both D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 10e,f). SCH23390 increased the clustered co-activity of D2-SPNs during periods of rest, whereas no drug affected the co-activity of either SPN type during movement (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 10g,h). Finally, SKF38393 decreased amplitudes of D1-SPN activity (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

Overall, the three compounds had similar effects on amphetamine-driven hyperlocomotion and D1-SPN hyperactivity but varied in their effects on the other D1-SPN and D2-SPN ensemble dynamics. Differences between the antagonists and SKF38393 were most notable under baseline conditions, where the antagonists markedly suppressed D1-SPN activity. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of D1R partial agonism, which state-dependently modulated D1-SPNs similarly to the other effective antipsychotics. At the same time, they underscore the potential limitations of D1R antagonism, which markedly suppressed D1-SPN activity under baseline conditions.

Discussion

For decades, it has been known that antipsychotics act on the dopamine system, but their actual mechanism of action is less clear. Here, each drug had multi-faceted and state-dependent effects on neural ensemble dynamics in the DMS, underscoring their complex effects on the brain. The fact that D2 and the other receptors bound by these drugs are expressed throughout the cortico-basal-ganglia circuit36–44 poses a challenge to linking their effects to their specific brain–receptor interactions. Although it is not possible to holistically determine how each drug exerts its actions, their divergent effects on D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity did distinguish them, even when their effects on locomotor activity were similar. Combining our observations with clinical observations allowed us to understand which effects were most relevant to psychosis and explore novel therapeutic strategies based on these insights.

Hyperdopaminergic striatal ensemble dynamics

Although amphetamine treatment is an imperfect proxy for dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to detail how it alters D1-SPN and D2-SPN ensemble dynamics. Consistent with classical models and amphetamine’s heterogeneous effects on unidentified SPNs45, amphetamine enhanced D1-SPN activity and suppressed D2-SPN activity (Fig. 1c,d) and reduced D1-SPN spatiotemporal coordination and increased D2-SPN spatiotemporal coordination16 (Fig. 1e,f). These changes were reminiscent of the dynamics associated with dyskinesia in our previous study16. Intriguingly, dyskinesia and disorganized behavior are also prevalent in schizophrenia, even in drug-naive patients46, suggesting that their neural substrates may overlap with psychosis. The spatially de-correlated D1-SPN hyperactivity could result from D1R modulation of intrinsic excitability or synaptic strength in D1-SPNs (ref. 47). By contrast, hyper-correlated, D2-SPN hypoactivity could result from D2R-mediated suppression of intrinsic excitability, synaptic strength or lateral inhibition between D2-SPNs (ref. 48). Although these changes account for how dopamine alters striatal dynamics, they do not specify which changes specifically underlie psychosis.

Neural ensemble correlates of antipsychotic drug efficacy

The drugs that we tested did not normalize every amphetamine-driven effect on striatal dynamics. For example, no drug prevented the increased spatiotemporal coordination of D2-SPN Ca2+ events (Fig. 1e,f). Some, but not all, drugs attenuated D2-SPN hypoactivity (Fig. 2f). This included the ineffective drug MP-10 but not the efficacious antipsychotic clozapine, arguing against a causal role for D2-SPN hypoactivity in psychosis. By contrast, every effective drug attenuated D1-SPN hyperactivity at rest, which was exacerbated by MP-10 (Fig. 2f). This was even the case for the non-dopaminergic drugs xanomeline, SEP-363856 and VU0467154 (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that resting D1-SPN hyperactivity may be a key driver of psychosis and its normalization a key indicator of antipsychotic effectiveness. However, which specific hyperdopaminergic D1-SPN dynamics (levels versus spatiotemporal coordination or both) are most therapeutically relevant is unclear. We have argued that the spatiotemporal coordination of SPN activity is important for striatal function and striatum-dependent behavioral processes16,49. However, the lack of tools to independently manipulate the rates and spatiotemporal dynamics of neural activity in vivo precludes a causal determination of their separate roles. Although we did not determine how it affects their spatiotemporal dynamics, chemogenetically reducing D1-SPN excitability partially rescued several psychosis-related behavioral processes (Fig. 4), implicating D1-SPN hyperactivity in psychosis.

Aside from a correlate of antipsychotic efficacy, our results provide insights into the different therapeutic profiles of these drugs. For instance, clozapine differed from the other antipsychotics in that it had no effects whatsoever on D2-SPN activity (Fig. 2f,g and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Although a lower D2R affinity and higher affinity for 5-HT2 receptors is thought to confer atypicals a lower propensity for extrapyramidal symptoms50–52, clozapine even stood apart from olanzapine. Clozapine’s D1-SPN-selective effects could explain its clinical superiority23, particularly for treatment-resistant schizophrenia53,54, and its affinity for D1Rs may underlie these effects55.

Although we cannot definitively determine the mechanisms by which each drug affects D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity, we can speculate. Direct D1R and D2R antagonism could explain the effects of the D1R antagonists and haloperidol on D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity, respectively. SKF38393’s effects on D1-SPN activity (after amphetamine treatment) could result from its lower intrinsic activity than dopamine at D1Rs. The fact that PDE10A is expressed in both D1-SPNs and D2-SPNs could explain MP-10’s effects on both SPN types after amphetamine treatment56. The cholinergic drugs xanomeline and VU0467154 likely suppressed D1-SPN hyperactivity via Gαi-coupled M4 receptors. Xanomeline may also have promoted the levels and event amplitudes of D1-SPN and D2-SPN via Gαq-coupled M1 receptors27. How haloperidol suppresses D1-SPN hyperactivity, and how the D1R antagonists attenuated D2-SPN hypoactivity after amphetamine treatment, is less clear but may involve their effects on striatal interneurons or inhibitory SPN collaterals57,58. It is also unclear how SEP-363856 suppresses D1-SPN hyperactivity, but TAAR1 is thought to suppress pre-synaptic dopamine release59. The drugs that we tested undoubtedly exerted some of their effects through non-D2Rs (ref. 20) and engaged receptors in brain areas other than striatum (for example, cortex and thalamus) to indirectly influence D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity.

Regardless of their precise mechanism, our data suggest that drug effects on hyperdopaminergic D1-SPN, rather than D2-SPN, dynamics is more predictive of antipsychotic efficacy. This conclusion is supported by the finding that clozapine normalized D1-SPN, but not D2-SPN, dynamics and that MP-10 exacerbated the D1-SPN dynamics. One explanation for MP-10’s lack of clinical efficacy is that its effects on D1-SPNs counteract any of its therapeutic effects on D2-SPNs. Because none of the drugs that we tested exclusively normalized D2-SPN activity, future experiments are necessary to determine whether selective D2-SPN modulation is associated with clinical efficacy. Still, the fact that every effective drug, including the non-dopaminergic ones, attenuated D1-SPN hyperactivity at rest supports its involvement in psychosis.

Drug effects on baseline D1-SPN and D2-SPN dynamics

In schizophrenia, fluctuations in striatal dopamine are thought to drive psychotic episodes, and dopamine transmission is normal in stabilized patients60. Considering this, treatments should ideally have minimal effects on striatal activity at baseline but counteract the effects of excess dopamine during psychotic episodes. Therefore, a drug’s effects on baseline neural activity may be equally relevant to its therapeutic viability as its effects under hyperdopaminergic conditions. Every effective antipsychotic that we tested differentially modulated D1-SPN dynamics under normal and hyperdopaminergic conditions. For example, effective drugs suppressed D1-SPN hyperactivity after amphetamine treatment but increased or had no effects on D1-SPN activity when administered alone (Figs. 2f and 3c and Extended Data Fig. 3a,c). These findings suggest that therapeutic viability depends not only on a drug’s ability to suppress D1-SPN activity but also on its ability to do so in a dopaminergic state-dependent manner.

Consistent with this idea, the D1R antagonists that we tested are not effective antipsychotics and suppressed D1-SPN activity independently of dopaminergic state22,61 (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 3e). Their indiscriminate suppression of D1-SPN activity may contribute to their intolerability and adverse effects on mood22,60,62. By contrast, D1R partial agonism had an agonist-like effect at baseline and an antagonist-like effect on D1-SPN activity under hyperdopaminergic conditions. This stabilization is analogous to the D2R-selective partial agonist antipsychotic aripiprazole63. Aripiprazole has been proposed to ameliorate psychosis by occluding striatal dopamine signaling and to improve cognition by promoting dopamine signaling in the cortex, where dopamine release is lower in schizophrenia64,65. However, aripiprazole lacks cognitive benefits relative to other antipsychotics9. This may reflect the fact that the cortex predominantly expresses D1Rs, not D2Rs66. Given that D1R partial agonism alleviates the cognitive impairment caused by cortical dopamine depletion in monkeys67,68, and our finding that SKF38393 had similar effects to clozapine on striatal activity, D1R partial agonism may be a viable monotherapy for both positive and cognitive symptoms.

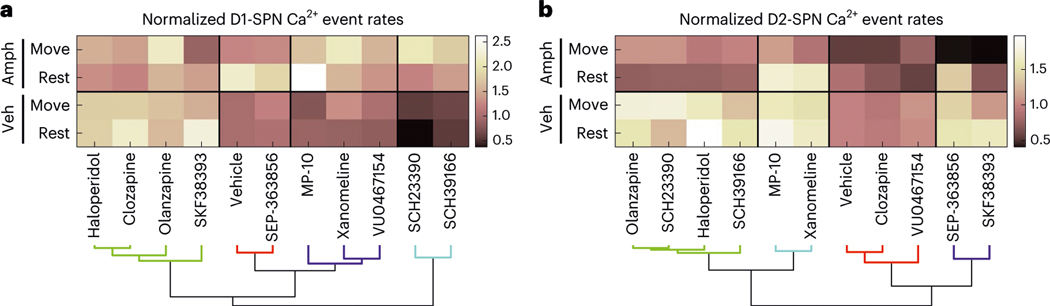

Given the apparent importance of state-dependent modulation, we used every drug’s effects on D1-SPN and D2-SPN activity levels across dopaminergic and locomotor states as features for hierarchical clustering. In this analysis, the clinically effective drugs co-clustered with the D1R partial agonist in terms of their effects on D1-SPN activity (Fig. 6a). By contrast, D1R antagonists were excluded from the effective drug cluster. Although the within-cluster similarity was greater in the analysis of D2-SPN activity, the groupings in the comparison of drug effects on D1-SPN activity were more representative of clinical effect (Fig. 6a,b).

Fig. 6 |. Antipsychotic efficacy is better explained by a drug’s effects on D1-SPN than D2-SPN activity levels.

a,b, Hierarchical clustering of drugs based on their highest dose effects on D1-SPN (a) or D2-SPN (b) activity levels under normal and hyperdopaminergic conditions. Veh, vehicle.

In summary, we have demonstrated the utility of a neural ensemble approach for understanding the mechanisms of brain diseases and their treatment. Specifically, antipsychotic efficacy was associated with a drug’s ability to normalize D1-SPN hyperactivity in a state-dependent manner. This advance was despite the limitations that the approach we used (amphetamine treatment) imperfectly mimics dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia10,69, and the readout was largely agnostic to each drug’s effects outside of the striatum. Direct manipulations of D1-SPN activity during behaviors related to psychosis support our conclusions and set the stage for new therapeutic strategies based on them. These findings and their methodology have the potential to inform the development of novel treatments for psychosis with fewer adverse effects and greater overall efficacy.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01390-9.

Methods

Mice

All mice were housed and handled according to guidelines approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were housed on a 12-h light/dark cycle and tested during the light phase. Animal housing rooms were maintained at 70–74 °F and 30–70% humidity. We used both male and female mice for all experiments. For Ca2+ imaging and DREADD experiments, we used GENSAT Drd1a (FK150) or Adora2a (KG139) BAC transgenic Cre-driver mouse lines (https://www.mmrrc.org/), backcrossed to a C57BL/6J background (JAX, 000664). For PPI experiments and drug–dose determination in the open field, we used C57BL/6J mice. All mice were 12–24 weeks of age at the start of experimental testing, except the mice used for slice electrophysiology, which were 7–8 weeks of age at the time of testing.

Virus injections

We anesthetized mice with isoflurane (2% in O2) and stereotaxically injected virus at a rate of 250 nl min−1 into the DMS using a microsyringe with a 33-gauge beveled-tip needle (WPI, Nanofil). All anterior-posterior (AP) and medial-lateral (ML) coordinates are reported from bregma, and all dorsal-ventral (DV) coordinates are reported from dura. For all DV coordinates, we went 0.5 mm past the injection target and then withdrew the syringe back to the target for the injection. After each injection, we left the syringe in place for 5 min, withdrew the syringe 0.1 mm, waited 5 more minutes and then slowly withdrew the syringe. We then sutured the scalp, injected analgesic (Buprenorphine SR, 1 mg kg−1) and allowed the mice to recover for at least 1 week.

For Ca2+ imaging experiments, we injected 500 nl of AAV2/9-Syn-FLEX-GCaMP7f (1.6 × 1012 GC ml−1; AP: 0.8 mm, ML: 1.5 mm and DV: −2.7 mm). To transduce a wider range of DMS neurons for DREADD behavioral experiments, we injected 650 nl of AAV2/9-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry (5.0 × 1012 GC ml−1) or AAV2/9-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (1.15 × 1012 GC ml−1) bilaterally at two sites in each hemisphere (AP: 0.4 mm, ML: ±1.5 mm and AP: 1.2 mm, ML: ±1.25, both DV: −2.8 mm). For sparser transduction in our DREADD electrophysiology experiments, we injected 650 nl of AAV2/9-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry (1.25 ×1012 GC ml−1) bilaterally at two sites in each hemisphere (AP: 0.4 mm, ML: ±1.5 mm and AP: 1.2 mm, ML: ±1.1 mm, both DV: −2.5 mm). We obtained all viruses from Addgene.

Implant surgeries

We constructed optical guide tubes by using ultraviolet (UV) liquid adhesive (Norland, no. 81) and a UV spot curing system (Electro-Lite) to fix a 2-mm-diameter disc of #0 glass (TLC International) to the tip of a 3.8-mm-long, 18-gauge, extra-thin stainless steel tube (Ziggy’s Tubes and Wires). We ground off any excess glass using a polishing wheel (Ultratec).

To prepare mice for Ca2+ imaging, we anesthetized virus-injected mice with isoflurane (2% in O2) and used a 1.4-mm-diameter drill bit to create a craniotomy (AP: 0.8 mm and ML: 1.5 mm) for implanting the optical guide tube. We used a 0.5-mm-diameter drill bit to drill four additional small holes at spatially distributed locations for insertion of four anchoring skull screws (Antrin Miniature Specialties). We aspirated cortex down to DV: −2.1 mm from dura using a 27-gauge blunt-end needle and implanted the optical guide tube at DV: −2.35 mm from dura. After placing the guide tube, we applied Metabond (C&B) to the skull and then used dental acrylic (Coltene) to fix the full assembly along with a stainless steel headplate (Laser Alliance) for head-fixing mice during attachment and release of the miniature microscope. We injected analgesic (Buprenorphine SR, 1 mg kg−1) and allowed the mice to recover for 3–4 weeks before mounting the miniature microscope.

Miniature microscope mounting

We head-fixed each implanted mouse by its headplate on a running wheel and inserted a gradient refractive index (GRIN) lens (1-mm diameter, 4.12-mm length, 0.46 numerical aperture (NA), 0.45 pitch; Inscopix) into the optical guide tube. We then assessed GCaMP7f expression in the DMS using a commercial two-photon fluorescence microscope (Bruker). Subsequently, we anesthetized mice with ample GCaMP7f expression (2% isoflurane in O2), placed them into a stereotaxic frame and glued the GRIN lens in the guide tube with UV light curable epoxy (Loctite, no. 4305). Next, we used the stereotaxic manipulator to lower the miniature microscope with its attached base plate (nVista, Inscopix) toward the GRIN lens until the fluorescent tissue came into focus. We then created a structure of blue-light curable resin (Flow-It ALC, Pentron) on the dental acrylic skull cap around the base plate and then attached the structure to the miniature microscope base plate using UV curable epoxy. Finally, we coated the epoxy/resin with black nail polish to make it opaque.

In vivo pharmacology

We administered all drugs via subcutaneous injection (1 ml kg−1 injection volume for SEP-363856 and 10 ml kg−1 injection volume for all other drugs). We administered treatment in blocks consisting of vehicle, low, medium and high dose for behavior only (Extended Data Fig. 2) or vehicle, low and high dose for Ca2+ imaging experiments (Figs. 2, 3 and 5). All mice received one treatment per day and one day off between the different treatment blocks. We used two cohorts of mice with the following treatment block orders: clozapine, haloperidol, MP-10, VU0467154, SKF38393 and SCH23390 (cohort 1); SCH39166, xanomeline, olanzapine and SEP-363856 (cohort 2). We randomly assigned both male and female to the cohorts but did not randomize the treatment block order within each cohort. However, baseline and hyperdopaminergic D1-SPN/D2-SPN dynamics were consistent within mice across the different treatment blocks (Extended Data Fig. 7).

We dissolved clozapine (1, 2 or 3.2 mg kg−1) and haloperidol (0.032, 0.1 or 0.32 mg kg−1) in 0.3% tartaric acid. We dissolved SCH23390 (0.01, 0.032 or 0.1 mg kg−1), SCH39166 (0.032, 0.1 and 0.32 mg kg−1), xanomeline (1, 3.2 and 10 mg kg−1) and D-amphetamine hemisulfate (2.5 or 10 mg kg−1) in saline (0.9% NaCl). We dissolved MP-10 (1, 3.2 or 10 mg kg−1) in 5% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in saline, VU0467154 (1, 3.2 or 10 mg kg−1) in 10% Tween 80, SKF38393 (10, 32 or 100 mg kg−1) in water, SEP-363856 (1, 3.2 and 10 mg kg−1) in DMSO and DCZ (1 or 10 μg kg−1) in 2% DMSO. We dissolved olanzapine (1 and 3.2 mg kg−1) in glacial acetic acid and brought to the desired volume and pH (~6.0) with saline and NaOH. We obtained VU0467154 from the Vanderbilt Center for Neuroscience and Drug Discovery; DCZ, xanomeline and SEP-363856 from MedChemExpress; and all other drugs/reagents from Sigma-Aldrich.

To examine treatment effects under normal and hyperdopaminergic states, we injected each drug or its corresponding vehicle and waited 10 min before recording open field behavior + Ca2+ activity for 15 min. We then injected amphetamine (2.5 mg kg−1) and waited 10 min before recording behavior + Ca2+ activity for 45 min (Fig. 2a). For PPI experiments, we administered the higher of the two doses of each drug or vehicle 25 min before amphetamine injection (10 mg kg−1) and measured PPI 25 min after amphetamine treatment (Fig. 2c). For chemogenetic manipulations in the open field, we administered DCZ (10 μg kg−1) or its vehicle 10 min before recording behavior for 15 min and then administered amphetamine (2.5 mg kg−1) and waited 10 min before recording behavior for 45 min. For chemogenetic manipulations during PPI, we administered DCZ (10 μg kg−1) or vehicle 25 min before amphetamine injection (10 mg kg−1) and measured PPI 25 min after amphetamine treatment. For chemogenetic manipulation during HALIP, we administered DCZ (1 μg kg−1), haloperidol (0.1 mg kg−1) or vehicle 25 min before amphetamine injection (2.5 mg kg−1) and began measuring HALIP 25 min after amphetamine treatment.

In vivo Ca2+ imaging

We habituated mice to a circular open field arena (30.48-cm diameter) for 3 d (1 h per day), during which we also habituated the mice to two subcutaneous injections of saline and one injection of amphetamine (2.5 mg kg−1). Just before each Ca2+ imaging session, we briefly head-fixed mice by their implanted headplate on a running wheel. We then attached the miniature microscope, adjusted its focal plane using Inscopix Data Acquisition Software (version 1.8.1) and released the mouse after securing the microscope. After 20 min of habituation in the open field, we injected mice with vehicle or drug, waited 10 min and recorded Ca2+ activity for 15 min and then injected amphetamine, waited 10 min and recorded Ca2+ activity for 45 min (Fig. 2a). We used an illumination power of 50–200 μW at the specimen plane and a 20-Hz image frame acquisition rate.

PPI

We placed mice into a plexiglass cylinder (10 × 20 × 10 cm) on a platform equipped with a piezoelectric transducer inside of a larger, sound-attenuating chamber with 65 dB of continuous background noise (SR-Lab 6310–0000-M, San Diego Instruments). Mice received 2 × 30-min habituation sessions on two consecutive days. During experimental testing, we treated mice with vehicle, drug or DCZ + amphetamine (see ‘In vivo pharmacology’ subsection) and placed them into the startle chamber. PPI evaluation consisted of a 5-min acclimation period followed by five priming acoustic stimulus pulses (120 dB, 40 ms) and then 20-trial blocks of pseudo-randomly presented trials of no-stimulus pulse or pre-pulse (0, 4, 8 or 16 dB above background, 20 ms), 100 ms before the acoustic startle stimulus (120 dB, 40 ms) (Fig. 2c). The inter-trial interval (ITI) averaged 17 s (range, 10–25 s). We calculated the levels of PPI at each pre-pulse intensity as 100 − (100 × [response amplitude for each pre-pulse stimulus with startle stimulus] / [response amplitude for 0 dB pre-pulse with startle stimulus]). We calculated mean % PPI by averaging levels of PPI at all three pre-pulse intensities.

HALIP

We used a modified version of a previously described procedure21. We water restricted ad libitum-fed mice to 85% of their original body weight. We performed behavioral testing in sound-isolated cabinets. All behavior chamber components were from Sanworks. The chambers (Mouse Behavior Bx r2) consisted of three LED-illuminated ports with solenoid valves for water delivery and infrared photodiodes for detecting port entry. We used two calibrated speakers, one on each side of the chamber, and a Bpod HiFi module to present background white noise and auditory signals. We used Bpod (version 1.64) in MATLAB (2019b) to control these signals, monitor nose poking and deliver water. We trained mice to initiate trials by poking their nose into the illuminated center port. Upon trial initiation, after a variable (0.1–0.5 s) interval, the center port LED turned off and re-illuminated for 0.1 s along with the presence or absence of an auditory stimulus embedded in 40 dB of constant white background noise. On signal trials, the auditory stimulus consisted of a 0.1-s sweeping stimulus (10–15 kHz) with a variable (35–65 dB) volume. On no-signal trials, the center port light cue was not accompanied by an auditory stimulus. After the center port light extinguished, the left and right reward ports illuminated, and mice were required to choose the ‘heard signal’ or ‘heard no signal’ reward port to obtain a 5-μl water reward. On correct choices, there was a delay between the choice and reward delivery and the extinguishing of the reward port LEDs that varied between 0.5 s and 5.0 s, according to an exponential distribution with decay constant of 1 s. For 5% of correct choices, we omitted reward delivery, resulting in catch trials that allowed us to measure the amount of time that mice were willing to invest on correct trials for comparison to their investment time at the reward port after incorrect choices.

We pre-trained mice that expressed hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry alone in DMS D1-SPNs in a three-phase protocol that lasted 4–10 weeks with gradually shorter stimulus durations, longer reward delays and the introduction of reward omission trials. In phase 1, we trained mice to coarsely discriminate between signal and no-signal trials. In phase 1a (days 1–2), we trained mice to self-initiate trials by poking into the illuminated center port by delivering 5 μl of water after the mice entered the center port. We then presented the mice with a signal (65 dB in 40 dB of white noise for 0.5 s) or no signal (40 dB of white noise only) and illuminated the signal or no-signal choice port, respectively, where mice could nose poke to obtain an additional 5 μl of water on correct choices. In phase 1b (days 3–4), we reduced the center port reward amount to 2 μl. In phase 1c (day 5 and beyond), we reduced the auditory stimulus duration to 0.3 s and stopped providing water in the center port. Once mice performed with an accuracy of greater than 70% in two consecutive sessions, we illuminated both the choice ports (not just the correct one) after the mice exited the center port on each trial and continued training until mice performed with greater than 70% accuracy for three consecutive sessions. In phase 2, we trained mice to finely discriminate the presence or absence of signal using a range of signal volumes (35–65 dB) embedded in white noise. In phase 2a, we trained mice with these stimuli (0.3-s duration) until they performed with greater than 65% accuracy in a single session. In phase 2b, we reduced the stimulus duration to 0.1 s and trained mice until their performance reached greater than 65% accuracy in two consecutive sessions. In phase 3, we introduced a delay in the choice feedback, defined as the time between the mouse’s choice and extinguishment of the choice port LED. In phase 3a, we varied the feedback between 0.05 s and 0.5 s until mice performed with greater than 65% accuracy in two consecutive sessions. In phase 3b, we varied the feedback delay between 0.1 s and 1.0 s and between 0.5 s and 5.0 s in phase 3c, training mice in each phase until they performed with greater than 65% accuracy in two consecutive sessions. We imposed a 0.5-s grace period during the feedback period to allow the mice to briefly remove and re-enter the choice port without triggering a choice omission. Finally, we introduced catch trials by omitting the reward on 5% of the trials. Once mice reliably performed this auditory discrimination task, we pre-treated the mice with vehicle, haloperidol or DCZ before administering amphetamine (see ‘In vivo pharmacology’ subsection) and tested their task performance for 90 min. We excluded the first 25 trials of each session, which were easy trials intended to acclimate the mice each day. We combined all other trials across multiple sessions in each experimental condition except for sessions with an accuracy below 60% and trials with time investments less than 2 s.

We computed the false alarm rate as the proportion of no-signal trials on which the mice chose the heard-signal reward port, and we computed the false alarm investment time as the duration of time between the choice initiation and port withdrawal on false alarm trials (Fig. 4f,g). We built psychometric curves by plotting the percentage of heard-signal choices as a function of the signal-to-noise ratio (Δ) of the auditory stimulus as previously described70 (Fig. 4e). We treated the no-signal trials to be Δ = −40 dB and binned trials starting at −40 dB in bins of 45, 10, 10, 5 and 5 dB up to Δ = 25 dB. We defined each bin’s value as the average Δ and then weighted the average according to the number of trials contained in each bin and used a 4-parameter sigmoid to fit psychometric curves of signal choice percentage (pS):

We used this sigmoid MATLAB fit function to fit the , , and parameters using the binned data and plotted the psychometric fit with the ± 1 s.d. binomial confidence intervals (using Jeffrey’s method) of the binned data (Fig. 4e).

Histology

After all Ca2+ imaging and DREADD experiments, we euthanized and intracardially perfused the mice with PBS and then a 4% solution of paraformaldehyde in PBS. We sliced 80-μm-thick coronal sections from the fixed-brain tissue using a vibratome (VT1000 S, Leica Microsystems). For immunostaining, we used an anti-GFP antibody (1:1,000, Invitrogen, A11122) and a fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 711–546-152) and then mounted the sections with DAPI-containing fluoromount (SouthernBiotech, 0100–20). We imaged slices using a fluorescence microscope (Keyence, BZ-X800) with a ×10 objective.

Slice electrophysiology

We anesthetized and transcardially perfused mice with ice-cold, carbogen-saturated cutting solution (185 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2 and 25 mM glucose, pH 7.3 (315–320 mOsm L−1)). After perfusion, we decapitated the mice, rapidly removed the brain and sectioned it in an ice-cold carbogen-saturated cutting solution using a vibratome (VT1000 S, Leica Microsystems). We then incubated coronal slices (220 μm) in carbogen-saturated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 93 mM NMDG, 93 mM HCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 30 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 Mm NaH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM Na-ascorbate, 3 mM Na-pyruvate, 2 mM thiourea, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgSO4 and 25 mM glucose, pH 7.3 (315–320 mOsm L−1) at 32–34 °C for 10 min and then in carbogen-saturated ACSF containing 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 25 mM glucose, pH 7.3 (315–320 mOsm L−1) at room temperature for at least 1 h before electrophysiological recordings. We transferred the brain slices to a small-volume (<0.5 ml) recording chamber mounted on a fixed-stage, upright microscope. We performed all electrophysiological recordings at 32–34 °C. The chamber was superfused with carbogen-saturated ACSF (SH-27B with TC-324B controller, Warner Instruments). We performed conventional whole-cell patch-clamp recordings on visually identified (×60, 0.9 NA water immersion objective) D1-SPNs expressing mCherry. Recording electrodes had tip resistances of 3–8 MΩ when filled with internal recording solution containing (in mM): 125 KMeSO4, 5 KCl, 5 NaCl, 0.02 EGTA, 11 HEPES, 1 MgCl, 10 phosphocreatine-Na2, 4 Mg-ATP and 0.3 Na-GTP, adjusted to pH 7.2 (300 mOsm L−1). We made all recordings using MultiClamp 700B amplifiers and filtered all signals at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. We discarded data if the series resistance changed more than 20% over the time course of the experiment. For drug treatment, we perfused vehicle (0.2% DMSO), DCZ (100 nM or 1 μM) or 10 μM of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) for 1 ml min−1.

Behavioral tracking

We used a TTL-triggered video camera with IC Capture 2.4 software (The Imaging Source) and a varifocal lens (T3Z2910CS, Computar) to record 20-Hz videos of freely moving mouse behavior. We used software written in ImageJ and part of the CIAtah analysis suite (https://bahanonu.github.io/ciatah/) to track each mouse’s position in an open field arena. In brief, we used this software to identify the mean location of the largest and darkest contiguous pixel group (that is, the mouse) in each movie frame and then computed the mouse’s locomotor speed from the trajectory of its centroid location across movie frames. We then applied a 1-s median filter to the resulting speed trace and downsampled the trace by a factor of 4 to match the temporal resolution of our downsampled, 5-Hz Ca2+ traces.

Automated pose estimation and behavior classification

We adapted the MARS26 to be used for a single mouse to automatically estimate pose, extract features and classify the behavior of each mouse. We used Amazon Web Services to crowdsource the creation of model training data, consisting of manual annotations of seven anatomically defined key points on the mouse body (nose, right ear, left ear, neck, right hip, left hip and base of tail), in 5,000 randomly sampled video frames. As previously described26, five crowd workers annotated each key point location in each image, and we defined the median key point location across workers as the ‘ground truth’ location for model training. We used the labeled frames to train a MARS model to estimate the pose of the mouse; using held-out test data to evaluate the model, we found that 50% of key points fall within a 1.8-mm radius of human-defined ground truth. We used the key point coordinates to compute the following features, as previously described: the mouse’s absolute orientation (phi, ori_head, ori_body), joint angle (angle_head_body_left, angle_head_body_right), the ellipse encircling the body (major_axis_len, minor_axis_len, axis_ratio, area_ellipse), distance to points within the frame (dist_edge_x, dist_edge_y, dist_edge) and speed (speed, speed_centroid, speed_fwd). We supplemented these features with an additional set of features to capture the posture of each mouse and its position with respect to the arena. Definitions of these features are provided in the table below.

| Feature name | Feature group | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ang1e_nose_neck_tail | Joint angle | Angle formed by the nose, neck and tail base key points. |

| ang1e_to_center | Joint angle | Angle formed by the nose and neck key points and the center of the open field arena. |

| dist_to_center | Distance to frame points | The distance from the nose key point to the center of the open field arena. |

| max_jitter | Speed | The maximum Euclidean distance traveled by any key point on the animal’s body from frame t to frame t+1. |

| mean_jitter | Speed | The across key points average of the Euclidean distance traveled by each key point from frame t to frame t+1. |

We assigned the center of the open field arena to be the minimum and maximum and coordinate across all key point coordinates in a given recording and then averaged these two values for each axis. Along each axis, we excluded coordinate values below the 0.01st and above the 99.99th percentiles as potential false detections. Finally, we added six features to the ‘joint angle’ feature group by computing the sine and cosine of each of the angle_head_body_left, angle_head_body_right and angle_nose_neck_tail features.

To train automated classifiers to detect rearing and grooming behaviors, we manually annotated a subset of videos for each behavior in Bento26. We used these manual annotations alongside subsets of the features described above to train MARS behavior classifiers as previously outlined26. For the rearing classifier, we used the absolute orientation, joint angle, body area ellipse, distance to frame points and speed feature groups. For the grooming classifier, we used the absolute orientation, joint angle, body area ellipse and speed feature groups. We used a held-out test set of data to evaluate classifier performance for rearing (precision: 0.93, recall: 0.72, F1 score: 0.81) and grooming (precision: 0.93, recall: 0.87, F1 score: 0.75).

For detecting right and left turns with MARS, we used the angle formed between the nose, neck and tail key points (‘angle_nose_neck_tail’ feature calculated by MARS). We defined right and left turns as frames in which the nose-neck-tail angle was ≤30° or ≤–30°, respectively. We excluded frames during which rearing or grooming occurred from these left and right turn categorizations.

We used each animal’s locomotor speed trace (see ‘Behavioral tracking’ subsection) and labeled each frame as either ‘rest’ if speed was <0.5 cm s−1 or ‘move’ if speed was ≥0.5 cm s−1. We calculated the derivative of this velocity trace from the difference between neighboring 5-Hz frames and defined bouts of acceleration and deceleration to occur when this was >1.25 cm s−1 or <1.25 cm s−1, respectively. We excluded frames during which another behavior (rearing, grooming or turning) occurred from these acceleration and deceleration categorizations. For the remaining frames not categorized as rearing, grooming, right turn, left turn, acceleration or deceleration, we used a 0.5 cm s−1 speed threshold to categorize frames as either ‘other rest’ and ‘other move’. Hence, the ‘rest’ versus ‘move’ categories differ from ‘other rest’ versus ‘other move’ only in that the latter pair excludes frames during which another listed behavior takes place.

Ca2+ movie pre-processing

We used the CIAtah analysis suite to (1) downsample the acquired Ca2+ movies in space using 2 × 2 bi-linear interpolation; (2) reduce background fluorescence by applying a Gaussian low-pass spatial filter to each movie frame and dividing each frame by its low-pass filtered version; (3) motion correct using the TurboReg algorithm; (4) normalize each movie by subtracting the mean fluorescence value for each pixel in time and dividing each pixel by the same mean fluorescence ; and (5) temporally downsample the resulting movies by a factor of 4 using linear interpolation to a frame rate of 5 Hz.

Active neuron identification

We used constrained non-negative matrix factorization for microendoscopic data (CNMF-E)71 to extract putative neurons from the processed movies. We then visually inspected and manually classified candidate cells in 13% of the Ca2+ imaging sessions (70 of 535 total imaging sessions) based on their size, shape and Ca2+ activity trace. We used these manually sorted data to train a machine-learning-based classifier (using the CLEAN module in CIAtah) to sort the entire dataset. The automated classifier categorized candidate cells based on the evaluation of 21 features of the CNMF-E spatial filters, their Ca2+ activity traces and the movies. Parameters included: the (1) diameter, (2) area and (3) perimeter of the cellular filter; (4) proportion of the pixels in the convex hull that were also in the spatial filter; (5) skewness and (6) kurtosis of the statistical distribution of intensity values in the spatial filter; (7) mean value of the signal-to-noise ratio, averaged over all Ca2+ transients within the candidate cell; number of Ca2+ transients greater than (8) one, (9) three and (10) five times the s.d. of the noise fluctuations within the candidate cells; (11) mean ratio of the peak rise and decay slopes of the Ca2+ transients; (12) mean full-width half-maximum value of the Ca2+ transients; (13) mean amplitude of the Ca2+ transients; (14) skewness and (15) kurtosis of the statistical distribution of intensity values of the full Ca2+ activity trace for each candidate cell; (16) mean amplitude variance at each timepoint in a 16-s window around each Ca2+ transient waveform; (17) mean correlation coefficient of all Ca2+ transient waveforms; (18) mean correlation coefficient between the CNMF-E image and, at most, 10 images taken from frames temporally aligned to Ca2+ event transients in the movie and cropped to a 20 × 20-pixel region centered on the CNMF-E image centroid; (19) the same as (18) but using a binarized image (all pixels below 40% of the maximum value set to 0, all above set to 1); (20) the same as (18) but using only the maximum correlation coefficient from all CNMF-E movie frame image comparisons; and (21) the same as (19) but using only the maximum correlation coefficient from all CNMF-E movie frame image comparisons. After computing these parameters for every candidate cell identified by CNMF-E, we used MATLAB’s Statistics and Machine Learning and Deep Learning software toolboxes to train support vector machine (SVM), general linear model (GLM) and neural network (nnet) classifiers to automatically classify neurons in our dataset.

Ca2+ event detection

After extracting individual cells and their time traces of Ca2+ activity, we evaluated the individual Ca2+ events in each cell trace using a threshold-crossing algorithm72. Noise and reduced fluctuations in baseline fluorescence were removed by averaging over a 600-ms (three frames) sliding window and then subtracting a median-filtered version (40-s sliding window) of the trace from the smoothed version. We calculated the s.d. of the resulting trace and identified any peaks that were ≥2.5 s.d. above baseline noise while enforcing a minimum interevent time of >1.6 s. We determined the initiation time of each Ca2+ event as the temporal midpoint between the time of each event’s fluorescence peak and the most recent preceding trough in fluorescence. All subsequent data analyses of neural activity used the resulting 5-Hz binarized event trains. To generate the illustrative Ca2+ activity traces in Fig. 1b, for each example cell we set to zero all pixels of the cell’s spatial filter with weights <50% of the maximum value in the filter and then applied the truncated filter to the movie to generate a Ca2+ activity trace.

Analysis of pairwise cell co-activity

We computed the fraction of all Ca2+ events that were shared between all pairs of neurons in each imaging field. This fraction is equivalent to a Jaccard index, , of the two cells’ correlated activity , where and are the binarized rasters of Ca2+ events for the two cells in each treatment condition16. We plotted, for all cell pairs, the Jaccard index as a function of anatomical separation between the centroids of each cell pair comparison (Extended Data Fig. 1c). To control for any effects of time-varying Ca2+ event rates, we also computed Jaccard indices for datasets in which the binarized Ca2+ event trace for each cell was circularly permuted in time by a randomly chosen temporal displacement. We did this for 1,000 different randomly permuted datasets. We then normalized the real, pairwise Jaccard index values by those obtained from the shuffled datasets. We defined ‘proximal cell co-activity’ as the mean Jaccard index for all cell pairs within 25–125 μm in each mouse, normalized by the corresponding value of the shuffled datasets. To examine the relationship between proximal cell co-activity and locomotor speed, we subdivided the shuffle-normalized proximal Jaccard indices into bins corresponding to locomotor speeds ranging from 0.5 cm s−1 to 8 cm s−1 (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Figs. 1d, 4c,d, 6c,d, 9c,d,g,h and 10c,d,g,h). To compare drug effects to vehicle, we normalized the values in each speed bin to the corresponding values after vehicle-only treatment and then averaged the speed bins during periods of rest (<0.5 cm s−1) and movement (0.5–8 cm s−1) to generate the bar plots in Figs. 1f, 2g, 3d and 5d and Extended Data Figs. 3b,d,f and 7b. We also used these vehicle-normalized values for the highest drug doses to generate the Drug/Vehicle heat plots or divided them again by the vehicle-normalized value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment to generate the Drug/Amph heat plots in the corresponding panels.

Analysis of event amplitudes

We identified average peak values of all Ca2+ transient events in each cell and averaged these values across all cells in each mouse as a function of their locomotor speed using the same speed bins described above (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 1e). To compare drug effects to vehicle, we normalized the values in each speed bin to the corresponding values after vehicle-only treatment and then averaged the speed bins during periods of rest and movement (Fig. 1h and Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). We also used these vehicle-normalized values for the highest drug doses to generate the Drug/Vehicle heat plots or divided them again by the vehicle-normalized value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment to generate the Drug/Amph heat plots in Extended Data Fig. 5a–c.

Analysis of event rates

We used the binarized Ca2+ event traces of each cell’s activity to compute their Ca2+ event rates and averaged these values across all cells in each mouse as a function of their locomotor speed using the same speed bins described above (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Figs. 1b, 4a,b, 6a,b, 9a,b,e,f and 10a,b,e,f). We normalized the values in each speed bin to the corresponding values after vehicle or vehicle-only treatment and then averaged the speed bins during periods of rest and movement to generate the bar plots in Figs. 1d, 2f, 3c and 5c and Extended Data Figs. 3a,c,e and 7a. We averaged these vehicle-normalized values after vehicle and vehicle or high dose drug (± amphetamine treatment) across all D1- or A2A-Cre mice and divided the D1- by A2A-Cre values to generate the corresponding D1/D2 heat plots. We also used the vehicle-normalized values for the highest drug doses to generate the Drug/Vehicle heat plots or divided them again by the vehicle-normalized value after vehicle + amphetamine treatment to generate the Drug/Amph heat plots in the corresponding panels.

Analysis of specific behaviors and their associated Ca2+ event rates

We computed the fraction of time that each mouse spent performing each behavior (see ‘Automated pose estimation and behavior classification’ subsection) and computed the average number of detected Ca2+ events across every cell and behaviorally categorized frame (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b,d). We analyzed the first 15 min (for vehicle control experiments) or 45 min (for amphetamine or drug + amphetamine experiments) of each behavior movie and its associated Ca2+ event traces. We excluded a mouse’s behavioral category from its associated event rate calculation if it performed the behavior for less than 5 s, owing to insufficient data to confidently estimate the event rate.

We calculated the predicted change in Ca2+ event rate after vehicle or drug + amphetamine treatment due to changes in the proportion of time spent engaged in specific behaviors by using the SPN activity levels associated with each behavior after vehicle treatment to calculate a weighted average based on the time spent engaged in each behavior after amphetamine or drug + amphetamine treatment. We did this separately for behaviors grouped as ‘resting’ or ‘moving’, normalized these weighted averages to their corresponding value after vehicle treatment and compared the normalized values to the Ca2+ event rates during rest and movement reported in the main text (Extended Data Fig. 8c,e).

Hierarchical clustering using drug-associated activity levels

For each mouse in each drug treatment group, we computed the mean Ca2+ event rate in D1-SPNs or D2-SPNs during periods of rest and movement after vehicle, drug or vehicle/drug + amphetamine treatment and normalized these values by the corresponding value after vehicle-only treatment, as shown in Figs. 2f, 3c and 5c and Extended Data Fig. 3a,c,e. We used these normalized values as ‘features’ to quantify the degree of dissimilarity between the different treatments. Specifically, we calculated the mean and variance of each feature across mice within each treatment group and used these values to compute the squared Mahalanobis distance between all treatment pairs. To reduce sensitivity to outliers, we assumed zero covariance between features in our measure of Mahalanobis distance and added a regularization term of 3 to all feature variances. We constructed a dendrogram of treatment groups using this matrix of Mahalanobis distances using Ward’s method, as implemented using the ‘linkage’ function in MATLAB. Finally, we applied a hand-selected threshold to the dendrogram to divide treatment groups into clusters. We performed these analyses separately for the D1-SPN and D2-SPN datasets (Fig. 6).

Data analysis and statistical tests