Abstract

Background:

Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori is the strongest risk factor for distal gastric cancer (GC). While GC incidence has decreased, variation by race and ethnicity is observed. This study describes GC presentation and screening services among Medicare patients by race/ethnicity, place of birth, and history of GC-related conditions.

Methods:

Using demographic, location and disease staging information, extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results – Medicare gastric cancer database (1997–2010), we compared frequencies of GC-related conditions (e.g. peptic ulcer, gastric ulcer, gastritis) and screening (H. pylori testing and endoscopy) from inpatient and outpatient services claims by selected race/ethnicity and place of birth.

Results:

Data included 47,994 incident GC cases with Medicare claims. The majority (48.0%) of Asian/Pacific Islanders (APIs) were foreign-born, compared to Non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs), Hispanics and Blacks (with 64.4%, 33.9%, and 72.9% US-born, respectively). For NHWs, the most frequently diagnosed GC site was the cardia (35.6%) compared to <15% (P<0.001) for APIs, Hispanics and Blacks. While more than 57% of all cases had a history of GC-related conditions, H. pylori testing was reported in only 11.6% of those cases. H. pylori testing was highest for APIs (22.8%) and lowest for Blacks (6.5%).

Conclusions:

Non-cardia GC, associated with H. pylori infection, was diagnosed more frequently among APIs, Blacks, and Hispanics than NHWs. Testing for H. pylori was low among all GC cases despite evidence of risk factors for which screening is recommended. Studies are needed to increase appropriate testing for H. pylori among higher risk populations.

Keywords: gastric cancer (GC), Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File (PEDSF), American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most diagnosed cancer and the third most common cancer-related death worldwide, with over one million cases diagnosed and 700,000 deaths1. In 2018, of the 1.7 million new cancer cases reported in the United States (US), 26,240 were GC2. Among the US elderly (those aged 65 years or older), cancer has an even larger impact as more than half of all new cancer cases and two-thirds of all cancer deaths occur in this group3. More specifically, of the incident GC cases in the US, 60% are diagnosed among individuals over age 65 years, representing 66% of all GC deaths in the US4. The median age at diagnosis is 68 years4 and the highest incidence occurs at approximately 70 years of age5.

Globally, more than 50% of all GC cases are diagnosed in Asia, specifically Japan, South Korea and China6. Similarly, within the US, GC incidence is highest among Asian/Pacific Islanders6, a minority group that has seen more than 400% population growth in the US in the last 30 years7. Within this Asian-American population, Americans of East Asian and Southeast Asian (e.g. Vietnamese) descent have higher incidence and mortality rates when compared to Americans of Non-Hispanic White origin8. In addition, in the US, Hispanics and African-Americans are disproportionately affected compared to Caucasians9.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a risk factor for GC, with chronic infection often resulting in chronic gastritis which can lead to gastric atrophy, which in turn leads to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer10–12. It has been estimated that 89% of non-cardia gastric cancer cases are attributable to H. pylori infection13. While the prevalence of H. pylori infection is lower in the US than in other places, such as Asia and South America14, Hispanic Americans and African-Americans experience a higher prevalence than Non-Hispanic Whites14. Thus, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)14,15 recommends testing for H. pylori infection in those at higher risk such as those taking long-term low-dose aspirin or initiating non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment, and in those with gastric cancer-related conditions such as peptic ulcer (to include gastric or duodenal ulcer) or a history of peptic ulcer10–12.

In this paper, we describe ethnic variations in GC presentation among the elderly population (65 years and older) whose data are in the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. Lui et al. identified GC differences in a general SEER population by ethnicity in incidence, stage of disease and survival16. Here, we extend this work with more recent data and describe differences in this population in screening services (H. pylori testing and endoscopy) by race/ethnicity, place of birth, and history of gastric cancer-related conditions.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

We used the National Cancer Institute’s population-based SEER-Medicare cancer database for gastric cancer. This database includes SEER identifiers for GC cases matched with identifiers contained in Medicare’s master enrollment file (for detailed description of this matching process see Warren et al.17). The linked database included medical outcomes of GC cases among the elderly (65 or older) who received fee-for-service Medicare benefits, as well as information regarding costs and utilization3. In addition, the GLOBOCAN 2012 Fact Sheet1 (accessed October 1, 2017 at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/stomach-new.asp) and the SEER Stat Facts4 (accessed October 1, 2017 at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html) web-sites were used to obtain updated incidence and mortality data.

Study Sample

The study sample comprised of the SEER data file and the Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File (PEDSF), which included patients with a diagnosis of gastric cancer from 1997 to 2010 (n=48,377) for whom Medicare data were available. We excluded those whose race was marked as either American Indian or Other/Unknown (n=383) due to the small sample size; 0.8% of the sample. These SEER records for the 47,994 gastric cancer cases were then merged with the inpatient hospital (Medicare Provider Analysis and Review – MEDPAR) and physician/outpatient services (National Claims History – NCH) claims in order to examine healthcare utilization.

Measures

We extracted demographic information: age at diagnosis, sex, marital status, place of residence, income, place of birth, SEER region, and race/ethnicity. Race/ethnicity was grouped into four categories: Non-Hispanic White, Asian American/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and Black. The SEER regions included: the Northwest (Connecticut, New Jersey), South (Kentucky, Louisiana, Georgia), Midwest (Detroit, Iowa) and West (Hawaii, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, California). Place of birth was categorized as US- or foreign-born or unknown; those born in any US territory (e.g. Puerto Rico, Guam) were classified as US-born. Income was based on census tract of residence using the 2000 Census from the PEDSF file, and classified by quartiles (<$35,149; $35,150-$43,348; $46,349-$60,306; >$60,307) as previously classified in other SEER-Medicare analyses18. Place of residence was classified as urban or rural; urban was defined as counties in metro areas (from fewer than 250,000 population to more than 1 million as described in the PEDSF data dictionary). Marital status was classified as married or not married.

Disease presentation factors (location and staging) were assessed. The location of the gastric cancer tumor was classified as cardia or non-cardia; non-cardia was further broken down into body & fundus, pyloric antrum, pylorus, lesser & greater curvature, and other (classified as other, specified sites of stomach and stomach unspecified) using ICD-9 codes in the dataset. Stage of tumor at diagnosis was classified as unstaged, in situ, local, regional, and distant using the historical SEER staging system7. Those with no information on location and stage of tumor were classified as missing.

Lastly, from the inpatient hospital and physician/outpatient services claims, we obtained information on presence of various gastric cancer-related conditions (i.e. peptic ulcer [ICD533], gastric ulcer [ICD531], duodenal ulcer [ICD532], gastrojejunal ulcer [ICD534], gastritis [ICD535], disorders of function, such as achlorhydria, persistent vomiting, and gastroparesis [ICD536], disorders-other, such as gastric diverticulum, chronic duodenal ileus, and gastroptosis [ICD537]), and screening services received (H. pylori testing [urease activity in blood: CPT83009; or breath: CPT78267, CPT78268, CPT83013, CPT83014; or antibody testing: CPT86677; or enzyme immunoassay: CPT87338 or CPT87339] and endoscopy [Berenson-Eggers Type of Service (BETOS) code: P8B – upper gastrointestinal endoscopy]). The dates for these conditions’ claims were queried to investigate when they were filed in relation to the gastric cancer diagnosis occurring between 1997 and 2010. The gastric cancer diagnosis dates were subtracted from the claims dates. The median time in months was calculated with a negative value indicative of claim being filed before the diagnosis, and a positive value indicative of claim being filed after the diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies of characteristics of cases were calculated for various subgroups. Two-sided chi-square tests (and two-sided ANOVA test on age at diagnosis) were used to assess differences in demographic and disease presentation factors, and to assess differences in gastric cancer-related conditions and screening (H. pylori testing, endoscopy) across race/ethnicities. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess differences in the median number of months between date of claim and date of diagnosis across race/ethnicities.

Results

Of the 47,994 eligible gastric cancer cases, 62% were Non-Hispanic White (NHW) (n=29,614), 13% were Asian/Pacific Islander (API; n=6,240), 12% were Hispanic (n=5,630), and 14% were Black (n=6,510). These records were merged with the inpatient hospital and physician/outpatient services claims. Among the 42,952 unique subjects with claims filed, 62% were NHW (n=26,707), 13% were API (n=5,529), 11% were Hispanic (n=4,783), and 14% were Black (n=5,933).

Demographic data and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis for all cases was 74.1 years with NHWs the oldest (74.6 y. ± 10.5), and Hispanic and Black cases the youngest (both 72.5 y.). Overall, 60% of the sample was male and 93% lived in an urban community. Within this sample, the highest percentages of subjects in the lowest-income quartile were among Black and Hispanic cases (57.6% and 39.8%, respectively), almost double NHW and API (22% in the lowest-income quartile). Over 60% of NHW and Black subjects were born in the US (64.4% and 72.9%, respectively), whereas Hispanics were almost evenly split (34% US-born vs. 32% foreign-born) and the majority of APIs were foreign-born (48%). Across all races/ethnicities, over 24% had an unknown place of birth, with Hispanics having the highest percentage at 34%. The above observed differences across races/ethnicities were statistically significant (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Non-Hispanic White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic and Black Gastric Cancer Medicare Cases (n=47,994) – 1997–2010

| Characteristica | Total (n=47,994) | NHW (n=29,614) | API (n=6,240) | Hispanic (n=5,630) | Black (n=6,510) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) or Mean ± SD | |||||

| Demographic Factors | |||||

| Age at Diagnosis | 74.1±10.7 | 74.6±10.5 | 74.5±9.9 | 72.5±10.8 | 72.5±11.7 |

| Male sex | 28,840 (60.1) | 18,304 (61.8) | 3,608 (57.8) | 3,336 (59.3) | 3,592 (55.2) |

| Married at diagnosis | 26,406 (55.0) | 16,827 (56.8) | 4,015 (64.3) | 3,078 (54.7) | 2,486 (38.2) |

| Lived in urban community | 44,784 (93.3) | 27,040 (91.3) | 6,231 (99.9) | 5,436 (96.6) | 6,077 (93.4) |

| Lowest-income quartile | 13,342 (28.6) | 6,165 (21.5) | 1,309 (21.5) | 2,206 (39.8) | 3,662 (57.6) |

| Place of Birth | |||||

| US-Born | 27,340 (56.9) | 19,078 (64.4) | 1,606 (25.7) | 1,911 (33.9) | 4,745 (72.9) |

| Foreign-Born | 7,390 (15.4) | 2,433 (8.22) | 2,995 (48.0) | 1,812 (32.2) | 150 (2.3) |

| Unknown | 13,264 (27.6) | 8,103 (27.4) | 1,639 (26.3) | 1,907 (33.9) | 1,615 (24.8) |

| SEER Region | |||||

| Northeast | 9,139 (19.0) | 7,068 (23.9) | 292 (4.7) | 654 (11.6) | 1,125 (17.3) |

| South | 8,238 (17.2) | 5,370 (18.1) | 120 (1.9) | 105 (1.9) | 2,643 (40.6) |

| Midwest | 5,090 (10.6) | 3,957 (13.4) | 73 (1.2) | 83 (1.5) | 977 (15.0) |

| West | 25,527 (53.2) | 13,219 (44.6) | 5,755 (92.2) | 4,788 (85.0) | 1,765 (27.1) |

| Disease Presentation | |||||

| Location of Tumor | |||||

| Cardia | 12,305 (26.5) | 10,195 (35.6) | 624 (10.4) | 809 (14.7) | 677 (10.9) |

| Non-Cardia | |||||

| Body & Fundus | 6,411 (13.8) | 3,688 (12.9) | 857 (14.2) | 945 (17.2) | 921 (14.9) |

| Pyloric Antrum | 9,086 (19.6) | 4,344 (15.2) | 1,895 (31.4) | 1,250 (22.8) | 1,597 (25.8) |

| Pylorus | 1,429 (3.1) | 680 (2.4) | 213 (3.5) | 255 (4.6) | 281 (4.5) |

| Lesser & Greater Curvature | 5,659 (12.2) | 2,917 (10.2) | 1,061 (17.6) | 774 (14.1) | 907 (14.6) |

| Other** | 11,469 (24.7) | 6,815 (23.8) | 1,377 (22.9) | 1,459 (26.6) | 1,818 (29.3) |

| Missingb | 1,635 (3.4) | 975 (3.3) | 213 (3.4) | 138 (2.5) | 309 (4.7) |

| Stage of Tumor at Diagnosis in All (Cardia & Non-Cardia) Cases | |||||

| Unstaged | 3,485 (13.2) | 2,203 (13.7) | 375 (10.8) | 404 (12.2) | 503 (13.8) |

| In Situ | 449 (1.7) | 295 (1.8) | 57 (1.6) | 46 (1.4) | 51 (1.4) |

| Local | 7,707 (29.1) | 4,661 (29.0) | 1,085 (31.2) | 894 (26.9) | 1,067 (29.2) |

| Regional | 7,488 (28.3) | 4,320 (26.9) | 1,122 (32.2) | 1,043 (31.4) | 1,003 (27.5) |

| Distant | 7,377 (27.8) | 4,576 (28.5) | 841 (24.2) | 931 (28.1) | 1,029 (28.2) |

| Missingb | 21,488 (44.8) | 13,559 (45.8) | 2,760 (44.2) | 2,312 (41.1) | 2,857 (43.9) |

| Stage of Tumor at Diagnosis in Non-Cardiac Cases | |||||

| Unstaged | 2,657 (14.4) | 1,536 (15.9) | 325 (10.9) | 356 (12.9) | 440 (14.3) |

| In Situ | 77 (0.4) | 57 (0.6) | 9 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

| Local | 5,348 (28.9) | 2,779 (28.8) | 940 (31.4) | 742 (26.9) | 887 (28.9) |

| Regional | 5,122 (27.7) | 2,422 (25.1) | 983 (32.8) | 857 (31.1) | 860 (28.0) |

| Distant | 5,280 (28.6) | 2,865 (29.7) | 738 (24.6) | 796 (28.9) | 881 (28.7) |

| Missingb | 15,570 (32.4) | 8,785 (29.7) | 2,408 (38.6) | 1,926 (34.2) | 2,451 (37.6) |

Statistical significance tests (age at dx – ANOVA; all others – chi-sq) yielded p-values<0.001

Missing: no information on location of tumor or stage of tumor; not included in totals used for frequency calculations

Total number diagnosed with non-cardia gastric cancer sample sizes: Total – 34,054; NHW – 18,444; API – 5,403; Hispanic – 4,683; Black: 5,524

Abbreviations: NHW: Non-Hispanic White; API: Asian/Pacific Islander

Northeast: CT and NJ; South: KY, LA, GA; Midwest: Detroit, Iowa; West: Hawaii, NM, Seattle, Utah, CA

Other: Other, specified sites of stomach & stomach unspecified

Cardia was the most diagnosed specific cancer site among all gastric cancer cases (26.5%), although there was variation by race/ethnicity. For NHWs, 35.6% of tumors were diagnosed in the cardia compared to 10% for APIs, 15% for Hispanics and 11% for Blacks. The most common site among APIs was the pyloric antrum (31.4%), while the other/unspecified stomach sites were more frequently reported among Hispanics and Blacks (26.6% and 29.3%, respectively), followed by the pyloric antrum (22.8% and 25.8%, respectively) (Table 1). For stage at diagnosis, over 55% of NHWs, Hispanics and Blacks were diagnosed at the regional or distant stage, compared with 63% of APIs diagnosed at the local or regional stage. While only about 30% of non-cardia gastric cancer (ncGC) was diagnosed while still localized (31% in APIs, 29% in Blacks and NHWs, and 27% in Hispanics), almost also 30% was not diagnosed until distant spread occurred (30% in NHWs, 29% in Blacks and Hispanics, and 25% in APIs). Furthermore, when APIs and Hispanics were stratified by place of birth, foreign-born cases had a higher percentage of GC diagnosed in non-cardia as compared to US-born cases (90.9% vs. 87.7% in APIs, respectively and 86.2% vs. 82.7% in Hispanics, respectively) (Table 2). The majority of both foreign- and US-born API cases had the ncGC diagnosed at regional stage (33% for both groups) compared to 35% for foreign-born Hispanic cases; majority of US-born Hispanic cases were diagnosed at the distant stage (30%). The differences across the races/ethnicities for the disease presentation factors were statistically significant (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of US-Born and Foreign-Born Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic Gastric Cancer Medicare Cases (n=11,870) – 1997–2010

| Characteristica | API‡ (n=6,240) | Hispanic‡ (n=5,630) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US-Born (n=1,606) | Foreign-Born (n=2,995) | US-Born (n=1,911) | Foreign-Born (n=1,812) | |

| Number (%) or Mean ± SD | ||||

| Demographic Factors | ||||

| Age at Diagnosis | 75.5±9.7 | 73.7±10.2 | 73.1±10.4 | 71.7±11.0 |

| Male sex | 988 (61.5) | 1,690 (56.4) | 1,157 (60.5) | 1,104 (60.9) |

| Married at diagnosis | 988 (61.5) | 1,974 (65.9) | 1,001 (52.4) | 1,057 (58.3) |

| Lived in urban community | 1,604 (99.9) | 2,991 (99.9) | 1,769 (92.7) | 1,807 (99.7) |

| Lowest-income quartile | 233 (15.3) | 750 (25.5) | 798 (42.6) | 739 (41.2) |

| SEER Region | ||||

| Northeast | 6 (0.4) | 165 (5.5) | 250 (13.1) | 209 (11.5) |

| South | 10 (0.6) | 60 (2.0) | 37 (1.9) | 28 (1.6) |

| Midwest | 4 (0.3) | 32 (1.1) | 43 (2.3) | 12 (0.7) |

| West | 1,586 (98.8) | 2,738 (91.4) | 1,581 (82.7) | 1,563 (86.3) |

| Disease Presentation | ||||

| Location of Tumor | ||||

| Cardia | 192 (12.3) | 264 (9.1) | 322 (17.3) | 246 (13.8) |

| Non-Cardia | ||||

| Body & Fundus | 252 (16.1) | 372 (12.9) | 307 (16.5) | 303 (17.1) |

| Pyloric Antrum | 407 (26.0) | 969 (33.5) | 388 (20.8) | 444 (24.9) |

| Pylorus | 37 (2.4) | 117 (4.0) | 83 (4.5) | 84 (4.7) |

| Lesser & Greater Curvature | 256 (16.4) | 537 (18.6) | 244 (13.1) | 259 (14.6) |

| Other** | 421 (26.9) | 635 (21.9) | 522 (27.9) | 441 (24.8) |

| Missingb | 41 (2.6) | 101 (3.4) | 45 (2.4) | 35 (1.9) |

| Stage of Tumor at Diagnosis in All (Cardia & Non-Cardia) Cases | ||||

| Unstaged | 71 (9.3) | 200 (11.6) | 151 (14.3) | 127 (11.6) |

| In Situ | 13 (1.7) | 24 (1.4) | 11 (1.0) | 14 (1.3) |

| Local | 194 (25.5) | 542 (31.3) | 265 (25.1) | 274 (24.9) |

| Regional | 245 (32.2) | 574 (33.1) | 316 (29.9) | 381 (34.6) |

| Distant | 237 (31.2) | 392 (22.6) | 315 (29.8) | 304 (27.6) |

| Missingb | 846 (52.7) | 1,263 (42.2) | 853 (44.6) | 712 (39.3) |

| Stage of Tumor at Diagnosis in Non-Cardiac Cases | ||||

| Unstaged | 60 (9.5) | 177 (11.7) | 135 (15.6) | 108 (11.7) |

| In Situ | 4 (0.6) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| Local | 159 (25.0) | 481 (31.7) | 211 (24.3) | 235 (25.4) |

| Regional | 210 (33.1) | 509 (33.6) | 257 (29.6) | 320 (34.6) |

| Distant | 202 (31.8) | 346 (22.8) | 263 (30.3) | 261 (28.2) |

| Missingb | 738 (45.9) | 1,113 (37.2) | 677 (35.4) | 605 (33.4 |

Total sample size includes US-born, Foreign-born and Unknown place of birth

Statistical significance tests (age at dx – ANOVA; all others – chi-sq) yielded p-values<0.05

Missing: no information on location of tumor or stage of tumor; not included in totals used for frequency calculations

Total number diagnosed with non-cardia gastric cancer sample sizes: API US-Born – 1,373; API Foreign-Born – 2,630; Hispanic US-Born – 1,544; Hispanic Foreign-Born – 1,531

Abbreviations: NHW: Non-Hispanic White; API: Asian/Pacific Islander

Northeast: CT and NJ; South: KY, LA, GA; Midwest: Detroit, Iowa; West: Hawaii, NM, Seattle, Utah, CA

Other: Other, specified sites of stomach & stomach unspecified

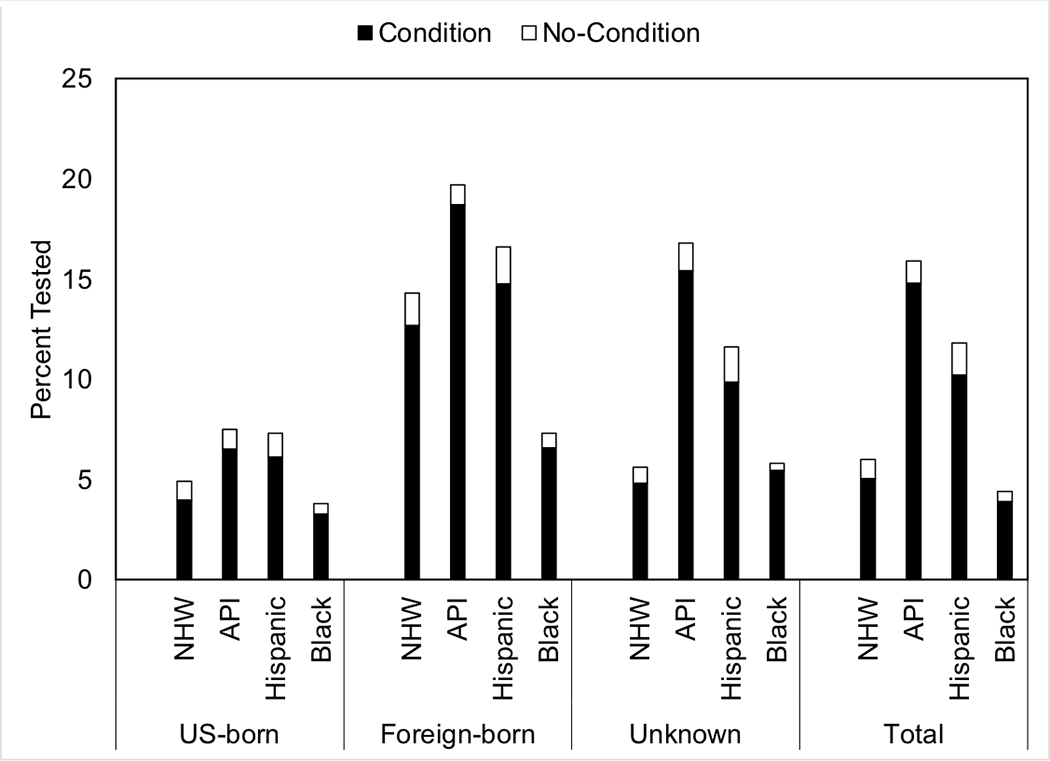

The most common gastric cancer-related conditions are summarized in Table 3. In the total sample, 46.1% of cases had a claim related to gastritis, followed by gastric ulcer (27.8%), with similar ordering when stratified by race/ethnicity. In addition, across all races/ethnicities, over 20% had a “disorder other”; the ICD9 code encompassed other disorders of stomach and duodenum such as gastric diverticulum, gastroptosis, and pylorospasm. Within those with an established gastric condition of a peptic ulcer, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer or a history of gastritis (over 55% across all cases), APIs had the highest percentage of H. pylori testing (22.8%) and Black cases had the lowest (6.5%). Within API cases, 72% of foreign-born cases had an established condition compared to 50% of US-born cases (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, foreign-born cases had higher frequency of H. pylori testing (26%). Similarly, for Hispanics, foreign-born cases had a higher percentage of established conditions (62% vs. 52% in US-born), with those foreign-born cases having double the H. pylori testing (24% vs. 12% in US-born). Endoscopy percentages within those with established conditions ranged from 86.2% in Hispanics to 90.9% in NHWs (Table 3). Overall, within those with an established condition, the H. pylori testing occurred 4.9 (33.0) months before the gastric cancer diagnosis, while the endoscopy occurred 0.3 (2.10) months after the diagnosis (Supplementary Table 3). A similar pattern was observed across all races/ethnicities with APIs having H. pylori testing occurring the furthest out at 7.10 (38.9) months before diagnosis and Black cases having the testing occur 3.15 (30.7) months before diagnosis. Within US-born subjects, APIs had the highest H. pylori testing frequency (7.5%) followed by Hispanics (7.3%). Among foreign-born cases, the testing frequency was highest for APIs (19.7%), followed by 16.6% for Hispanics, 14.3% for NHWs, and 7.3% for Blacks. And within those with an unknown place of birth, APIs also had the highest testing frequency (16.8%) followed by Hispanics (11.6%) (Figure 1). Comparing US-born versus foreign-born cases, endoscopy testing was generally higher in foreign-born than US-born across race/ethnic groups (aside from Blacks) with the biggest difference for APIs (75% in foreign-born vs. 56% in US-born). The differences across races/ethnicities for these conditions were statistically significant (P<0.001).

Table 3.

Medical Services Claims for Specific Gastrointestinal Disorders and Screening History Among Gastric Cancer Cases by Race/Ethnicity (n=42,952) – 1997–2010

| Characteristica (ICD9 Codes) | Total (n=42,952) | NHW (n=26,707) | API (n=5,529) | Hispanic (n=4,783) | Black (n=5,933) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | |||||

| Gastric Cancer-Related Conditions | |||||

| Peptic Ulcerb [ICD533] | 6,116 (14.2) | 3,281 (12.3) | 1,241 (22.5) | 757 (15.8) | 837 (14.1) |

| Gastric Ulcer [ICD531] | 11,919 (27.8) | 6,927 (25.9) | 1,899 (34.4) | 1,321 (27.6) | 1,772 (29.9) |

| Duodenal Ulcer [ICD532] | 1,681 (3.9) | 1,020 (3.8) | 288 (5.2) | 168 (3.5) | 205 (3.5) |

| Gastrojejunal Ulcer [ICD534] | 874 (2.0) | 509 (1.9) | 155 (2.8) | 117 (2.5) | 93 (1.6) |

| Gastritis [ICD535] | 19,820 (46.1) | 11,899 (44.6) | 2,918 (52.8) | 2,231 (46.6) | 2,772 (46.7) |

| Disorders Function [ICD536] | 10,416 (24.3) | 6,162 (23.1) | 1,762 (31.9) | 1,134 (23.7) | 1,358 (22.9) |

| Disorders Other [ICD537] | 10,165 (23.7) | 5,961 (22.3) | 1,501 (27.2) | 1,128 (23.6) | 1,575 (26.6) |

| Mucositis | 17 (0.04) | 11 (0.04) | 1 (0.02) | 3 (0.06) | 2 (0.03) |

| Established Conditionsc | 24,907 (57.9) | 15,067 (56.4) | 3,581 (64.8) | 2,722 (56.9) | 3,537 (59.6) |

| H. pylori Testingd | 2,878 (11.6) | 1,344 (8.9) | 816 (22.8) | 488 (17.9) | 230 (6.5) |

| Endoscopyd | 22,280 (89.5) | 13,694 (90.9) | 3,189 (89.1) | 2,346 (86.2) | 3,051 (86.3) |

| Medical Services & Testing | |||||

| H. pylori Testing | 3,306 (7.7) | 1,605 (6.0) | 877 (15.9) | 564 (11.8) | 260 (4.4) |

| Endoscopy | 30,045 (69.9) | 19,241 (72.0) | 3,834 (69.3) | 2,987 (62.5) | 3,983 (67.1) |

Statistical significance tests of chi-sq yielded p-values<0.001 except for Mucositis (cells had expected counts <5; statistical test not valid)

Includes history of peptic ulcer

Established conditions: combined count of those with peptic ulcer or gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer or a history of gastritis which are indicator conditions for H. pylori testing

Frequencies are of total number with an established condition

Abbreviations: NHW: Non-Hispanic White; API: Asian/Pacific Islander

Figure 1.

H. pylori testing by place of birth and race/ethnicity.

Abbreviations: NHW: Non-Hispanic White; API: Asian/Pacific Islander

The black bar indicates the percent tested among those with a diagnostic code for guideline-based established conditions (peptic ulcer or gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer or a history of gastritis), while the white bar indicates testing among those without.

Discussion

Currently, gastric cancer is the fifth most diagnosed cancer in the world and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths1. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased over time, racial and ethnic differences in both incidence and survival have remained throughout the US. For example, even though Asians have the highest gastric cancer incidence, survival in this group is the highest overall16. Whereas previous work16 identified gastric cancer differences by ethnicity in incidence, stage of disease and survival, we expanded the work by using more recent data and describing gastric cancer differences in screening (Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) testing and endoscopy) among the SEER-Medicare population by ethnicity, place of birth, and gastric cancer-related conditions.

Within this SEER-Medicare gastric cancer population, the average age at diagnosis was 74 years old, similar to other studies5. Of note, Hispanic and Black cases were diagnosed at a younger age. The majority of NHWs, Hispanics and Blacks were US-born, in contrast to APIs. Foreign-born NHWs were diagnosed at the oldest age, while foreign-born Hispanic and Black cases were diagnosed at younger ages. The majority of the cases was male, as seen in global non-cardia gastric cancer rates where the male-to female ratio is approximately 2:119. The majority of Hispanic and Black cases presented in the lowest-income quartile, which is of interest as lower socioeconomic status has been associated with lifestyle behaviors that increase cancer risk20.

We observed notable racial and ethnic variation in both screening practices and disease presentation. Non-cardia gastric cancer is strongly associated with H. pylori infection21. While, overall, the majority of all cases were diagnosed in the non-cardia area, there were important variations by race/ethnicity. Over 35% of NHWs were diagnosed in the cardia region versus less than 15% for Blacks, Hispanics and APIs. For Hispanics, the majority of cases was diagnosed as either regional tumor, meaning the cancer extended beyond organ of origin into surrounding organs, or with distant tumor (metastatic disease). When stratified by place of birth, the majority of foreign-born Hispanic non-cardia tumor cases were diagnosed at regional stage, while US-born Hispanics were diagnosed as distant. On the other hand, majority of NHW and Black cases were diagnosed as either local or distant; and majority of API cases diagnosed as either local or regional. While 50% of patients with localized gastric cancer can be cured, the 5-year survival rate for disseminated gastric cancer is lower than 20%22. Additionally, the majority of Hispanics and Blacks had the location of their non-cardia tumor as “other”. Thus, either their tumor was located in areas of the stomach that could not be classified as body & fundus, pyloric antrum, pylorus and the curvatures; or location could not be determined; or location was not completely evaluated.

Screening for H. pylori is recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) among individuals with gastric cancer-related conditions such as peptic ulcer, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer or a history of peptic ulcer14,15. Despite a high proportion of non-cardia gastric cancer with late staging (~30% regional), in the SEER-Medicare population, testing for H. pylori was low (7.7%) even among those with GC-related conditions (11.6%). However, the H. pylori testing both overall and for those with established conditions, occurred about 4 months before gastric cancer diagnosis. This is indicative that screening did occur before diagnosis. Furthermore, testing was particularly low among Black GC cases with established conditions (6.5%), though this testing occurred within the shortest time period before GC diagnosis at 3.2 months. H. pylori testing was highest in APIs with established conditions (23%), but occurred about 7 months before GC diagnosis. A large proportion of foreign-born API cases also had established conditions (72%), but only 26% were tested for H. pylori. Lastly, an important disparity became apparent among Hispanics with established conditions, who had the second highest H. pylori testing (17.9%), but the lowest endoscopy testing (86.2%); Hispanics also had the lowest endoscopy frequency across all individuals (62.5%). Endoscopy rates were highest in NHWs with established conditions (91%), and unlike H. pylori testing, endoscopies were performed, both overall and for those with established conditions, 0.3 months after gastric cancer diagnosis. This low level of testing and potential screening is contrary to the findings of a recent survey of gastroenterologists which indicated that 97% of practitioners regularly test for H. pylori infection among patients with established conditions and 85% of practitioners report testing patients with gastritis10. If these SEER-Medicare data are representative of broader testing and reporting practices, they indicate a potential source for intervention. Crew et al.19 reported decreased mortality in high-risk H. pylori areas as a result of regular screening and early detection; for example, a 50% reduction in mortality in men in Japan due to implementation of mass screening programs.

Others have also suggested that individuals who migrate from high-risk areas (such as Japan) to low-incidence regions experience a decreased risk in developing gastric cancer19. This finding is borne out in the current study, where API cases, the majority of whom were foreign-born, were the only group with a majority of cases diagnosed at local or regional stage of non-cardia tumor. In addition, H. pylori testing was higher in foreign-born than US-born cases; cases with unknown place of birth had higher testing rates than US-born cases as well.

Among gastric cancer cases, Lui et al. found the incidence of localized cancer had increased for Black cases and stayed the same for Hispanics between 1992 and 200916. Our results showed that the most common stages at diagnosis in this elderly population were regional (28.3%) and local (29.1%). The top two stages for Black cases were distant (28.2%) and local (29.2%), which is consistent with other cancer studies showing that African-Americans experience the highest mortality and shortest survival20. Similar to the findings of Torre et al.23, which stated that APIs in a non-Medicare sample were more likely to be diagnosed with gastric cancer at localized or regional stage than NHWs, we found the majority of APIs (63%) were diagnosed at the local or regional stage.

The present study had several strengths. First, it utilized fourteen years of incidence data from the large population-based SEER cancer registry data that had been merged with Medicare claims data. The results of this study would likely be generalizable to the elderly US population which receives Medicare benefits. Second, the findings described disparities in screening and gastric cancer precursor conditions. This study also expanded upon the classic race/ethnicity categorizations by classifying race/ethnicity by place of birth. There were also several limitations. The SEER-Medicare dataset included only cases whose data (or healthcare) was in the fee-for-service Medicare claims data. As the data only capture the time a person was enrolled in Medicare, it is possible that H. pylori testing could have occurred before that person was eligible for Medicare. The current analysis did not analyze, in-depth, the time interval between testing for H. pylori and endoscopy services, and GC diagnosis. Future analyses will focus more on determining screening and diagnostic testing both in relation to the various conditions, such as ulcers, and by race/ethnicity. In addition, these future analyses will also investigate socio-demographic factors and relevant conditions to determine what might predict whether individuals receive an endoscopy. Another limitation of our study is related to the information on race/ethnicity and place of birth. The information on race/ethnicity came from medical records, death records, and registration information,24 which may be more subject to misclassification, especially for Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whites.7 Furthermore, we used a combination of the Hispanic origin variable as determined by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACR) Hispanic/Latino Identification Algorithm (NHIA), and the SEER race/ethnicity variable. The Hispanic surname algorithm that is part of the NAACR tool may not distinguish between Hispanic/Latino and Portuguese, Italian or Filipino.25 Additionally, responses to Hispanic/Latino origin questions have been inconsistent in self-report which may be problematic with medical records that use patient self-report.25 Lastly, place of birth information also came from medical records, as well as death records26 and was missing from 28% of the cases. As a result, because of more complete data on death certificates, the information on place of birth might be more complete for deceased patients7,26,27.

The current study is the first to describe demographic differences among gastric cancer cases in the SEER-Medicare population by race/ethnicity. Tumor location suggests that H. pylori infection still plays a potential causal role for many GC cases. Importantly, location and stage of tumor at diagnosis differed by race/ethnicity and H. pylori testing was higher in foreign-born than US-born cases. H. pylori testing was low despite a high proportion of cases exhibiting gastric conditions for which H. pylori testing is recommended. Future studies can investigate the reasons for the low H. pylori testing rates in elderly patients with gastric cancer-related conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the work put in by past and present members of the Helicobacter pylori working group at the Mel & Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, Tucson AZ. Special thanks to Elizabeth Jacobs, PhD who provided outside review of the working manuscript, and to Jose M. Guillen-Rodriguez for his statistical assistance and advice. An oral abstract presentation related to this work was given at the American Society of Preventive Oncology annual meeting in New York City, New York March 10–13, 2018.

Funding:

The work and research reported in this publication was supported by the Chapa Foundation, Tucson AZ., and by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30 CA023074

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Society AC. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Medical care 1993;31:732–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Stomach Cancer. [Internet]. Rockville, Maryland; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saif MW, Makrilia N, Zalonis A, Merikas M, Syrigos K. Gastric cancer in the elderly: an overview. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 2010;36:709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe KA, Danese MD, Gleeson ML, Langeberg WJ, Ke J, Kelsh MA. Racial and Ethnic Variability in the Prevalence and Incidence of Comorbidities Associated with Gastric Cancer in the United States. Journal of gastrointestinal cancer 2016;47:168–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Davis RB, Li FP, Phillips RS. Older Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders dying of cancer use hospice less frequently than older white patients. The American journal of medicine 2003;115:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor VM, Ko LK, Hwang JH, Sin MK, Inadomi JM. Gastric cancer in asian american populations: a neglected health disparity. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP 2014;15:10565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rugge M, Fassan M, Graham DY. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer: Springer; 2015:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami TT, Scranton RA, Brown HE, et al. Management of Helicobacter Pylori in the United States: Results from a national survey of gastroenterology physicians. Preventive medicine 2017;100:216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JR, Marshall B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet (London, England) 1983;1:1273–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection and the Development of Gastric Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2001;345:784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori. International journal of cancer 2015;136:487–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. The American journal of gastroenterology 2017;112:212–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The American journal of gastroenterology 2007;102:1808–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lui FH, Tuan B, Swenson SL, Wong RJ. Ethnic disparities in gastric cancer incidence and survival in the USA: an updated analysis of 1992–2009 SEER data. Digestive diseases and sciences 2014;59:3027–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Medical care 2002;40:Iv-3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder RA, Penson DF, Ni S, Koyama T, Merchant NB. Trends in the use of evidence-based therapy for resectable gastric cancer. Journal of surgical oncology 2014;110:285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology 2006;12:354–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2016;66:290–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hacc Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut 2001;49:347–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancer AJCo. Stomach Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:117–21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torre LA, Sauer AM, Chen MS Jr., Kagawa-Singer M, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, 2016: Converging incidence in males and females. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2016;66:182–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bach PB, Guadagnoli E, Schrag D, Schussler N, Warren JL. Patient demographic and socioeconomic characteristics in the SEER-Medicare database: Applications and limitations. Medical care 2002:IV19–IV25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Group NRaEW. NAACCR Guideline for Enhancing Hispanic/Latino Identification: Revised NAACCR Hispanic/Latino Identification Algorithm [NHIA v2.2.1]. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinheiro PS, Bungum TJ, Jin H. Limitations in the imputation strategy to handle missing nativity data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Cancer 2014;120:3261–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin SS, O’Malley CD, Lui SW. Factors associated with missing birthplace information in a population-based cancer registry. Ethnicity & disease 2001;11:598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.