Abstract

Neonatal endotracheal intubation is a challenging procedure with suboptimal success and adverse event rates. Systematically tracking intubation outcomes is imperative to understand both universal and site-specific barriers to intubation success and safety. The National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates (NEAR4NEOS) is an international registry designed to improve neonatal intubation practice and outcomes that includes over 17,000 intubations across 23 international sites as of 2023. Methods to improve intubation safety and success include appropriately matching the intubation provider and situation and increasing adoption of evidence-based practices such as muscle relaxant premedication and video laryngoscope, and potentially new interventions such as procedural oxygenation.

Keywords: Neonate, Intubation, Safety

Introduction

Endotracheal Intubation is a life-saving intervention performed in up to 20% of critically ill neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients.1 The procedure is high-risk, and adverse safety events are frequent. Therefore, pertinent procedural outcomes include both success and adverse events. The National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates (NEAR4NEOS) is an international registry designed to improve neonatal intubation practice and outcomes. This article will review the state of neonatal intubation regarding both success and safety and will highlight contributions from the NEAR4NEOS collaborative.

The National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates

NEAR4NEOS evolved from the National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) family. The National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) initially reported on the process and outcomes of airway management performed across 31 emergency departments from 1997–2002.2 The NEAR infrastructure was adapted for pediatric airway management and piloted in a single center.3 In 2010, the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS) was launched in a multicenter setting with 15 founding sites.4

NEAR4NEOS was further adapted for relevance to the neonatal population but retains many of the same structural elements and operational definitions as the other NEAR registries.5 NEAR4NEOS was originally established in 2014 and has since expanded to include 23 international sites. Detailed patient, provider, practice, and outcome data are collected using standard operational definitions for all intubations in the NICU and delivery room (DR) setting (Table 1). As of 2023, over 17,000 intubation procedures have been captured in NEAR4NEOS.

Table 1:

Characteristics captured in NEAR4NEOS Registry

| Event | Patient | Provider | Practice | Process | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Age (gestation, postnatal) | Discipline | ETT size, type Stylet | Family presence | Success |

| Date | Weight | Training level | Laryngo-scope type | Change in approach | TIAEs |

| Hospital | Diagnoses | Years of Experience | Equipment | Teamwork assessment | Oxygen saturation |

| Location | Intubation indication | Supervision present | Medication (type and dose) | Glottic exposure grade (I-IV) | Heart rate |

| Difficult airway features | Method (oral vs nasal) | Number of attempts | NICU respiratory outcomes |

ETT: endotracheal tube; TIAE: tracheal intubation associated event

Neonatal Intubation Success

Endotracheal intubation is technically challenging to perform in neonatal patients due to airway anatomic differences from older patients, including a large epiglottis and anterior larynx.6 In addition, compared with adults and larger children, infants have a smaller functional residual capacity and higher oxygen consumption,7 leading to more rapid oxygen desaturation during apnea.8 This results in a shorter duration of apnoeic time for providers to safely perform the intubation. Accordingly, overall first attempt success rates in NEAR4NEOS (49%) are lower than those reported for older children in NEAR4KIDS (60%)9 or adolescents and adults in NEAR (83%).10

Airway provider training level is consistently associated with improved procedural success; neonatal fellows and attendings demonstrate progressively higher success rates compared with residents.5,11,12 Historically, reported success rates for residents ranged between 20–40% for a given attempt.11,13 More contemporary data suggest lower success rates: Haubner et al. reported first attempt rates of 16% and overall success rates of 20% for residents.12 In the initial NEAR4NEOS analysis, residents were successful in 24% of intubation procedures on the first attempt and 56% of procedures within 2 attempts.5

The impact of changes in neonatal care

Changes in neonatal practice and reductions in trainee work hours have reduced intubation procedural learning opportunities for medical trainees.14–15 Thus, it is important to ensure that all learners who must acquire intubation skills have sufficient exposure to the procedure. Evans et al. recently employed cumulative sum (Cusum) methodology to determine the number of intubation procedures required for neonatal fellows to achieve competence, which was defined as an 80% success rate within 2 attempts.16 Among fellows who demonstrated procedural competence, a median of 18 procedures was required. Of note, the number of procedures required to demonstrate competence ranged from 8–46 across fellows, suggesting an individualized approach is warranted to promote trainees’ progression to procedural competence.

Optimising Neonatal Intubation Success

For training institutions, one approach to optimize intubation outcomes is to ensure the intubation provider, encounter, and patient are appropriately matched (Table 2). For example, it may be appropriate to prioritize more challenging intubation procedures for experienced providers. Increasing patient weight is associated with increased odds of procedural success in observational studies.16–17 Gariépy-Assal recently demonstrated the impact of a specialized “tiny baby intubation team” on intubation outcomes for patients with weight <1000 grams or postmenstrual age <29 weeks. First intubation success rates for “tiny babies” improved from 44% before implementation to 59% post-implementation.18

Table 2:

Factors independently associated with neonatal intubation success for neonatal fellows (adapted from Evans et al.)16

| aOR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training quarter | 1.10 | 1.07, 1.14 | <0.001 |

| Muscle relaxant premedication | 1.77 | 1.35, 2.33 | <0.001 |

| Video laryngoscopy | 1.67 | 1.19, 2.33 | 0.003 |

| Patient weight <1000g | 0.61 | 0.48, 0.77 | <0.001 |

Premedication is an important factor associated with intubation success. Although premedication is recommended for non-emergent neonatal intubation,19,20 its use is inconsistent, and important variability exists around the types of medications included in premedication regimens.21,22 In an analysis of 2260 intubations in the NEAR4NEOS registry, intubations performed with sedation plus neuromuscular blockade were more likely to be successful on the first attempt (56%) compared with sedation only (34%) or no medication (47%).23 These data support the inclusion of muscle relaxants as a component of intubation premedication, and are consistent with previous studies of premedications in neonatal intubation.24

Intubation equipment such as a video laryngoscope or stylet may influence intubation success. A video laryngoscope provides an improved view of the glottis and airway structures that is displayed on a screen visible by all clinicians involved in the procedure. Early neonatal trials demonstrated improved procedural success outcomes for resident providers when their supervisors could see the video laryngoscope screen and provide guidance to the resident.25,26 A recent meta-analysis of 8 trials favored video laryngoscopy over traditional (direct) laryngoscopy for the outcome of first attempt success during neonatal intubation (number needed to treat of 7, 95% confidence interval 5–13).27 Outside of the controlled trial setting, video laryngoscopy is associated with improved success for fellows in NEAR4NEOS,16 but the results were not consistent when all providers were assessed.28 Video laryngoscopy is further discussed in Chapter 4. Stylet use during intubation has also been investigated but was not associated with procedural success in a randomized trial29 or observational study.17

Neonatal Intubation Adverse Events

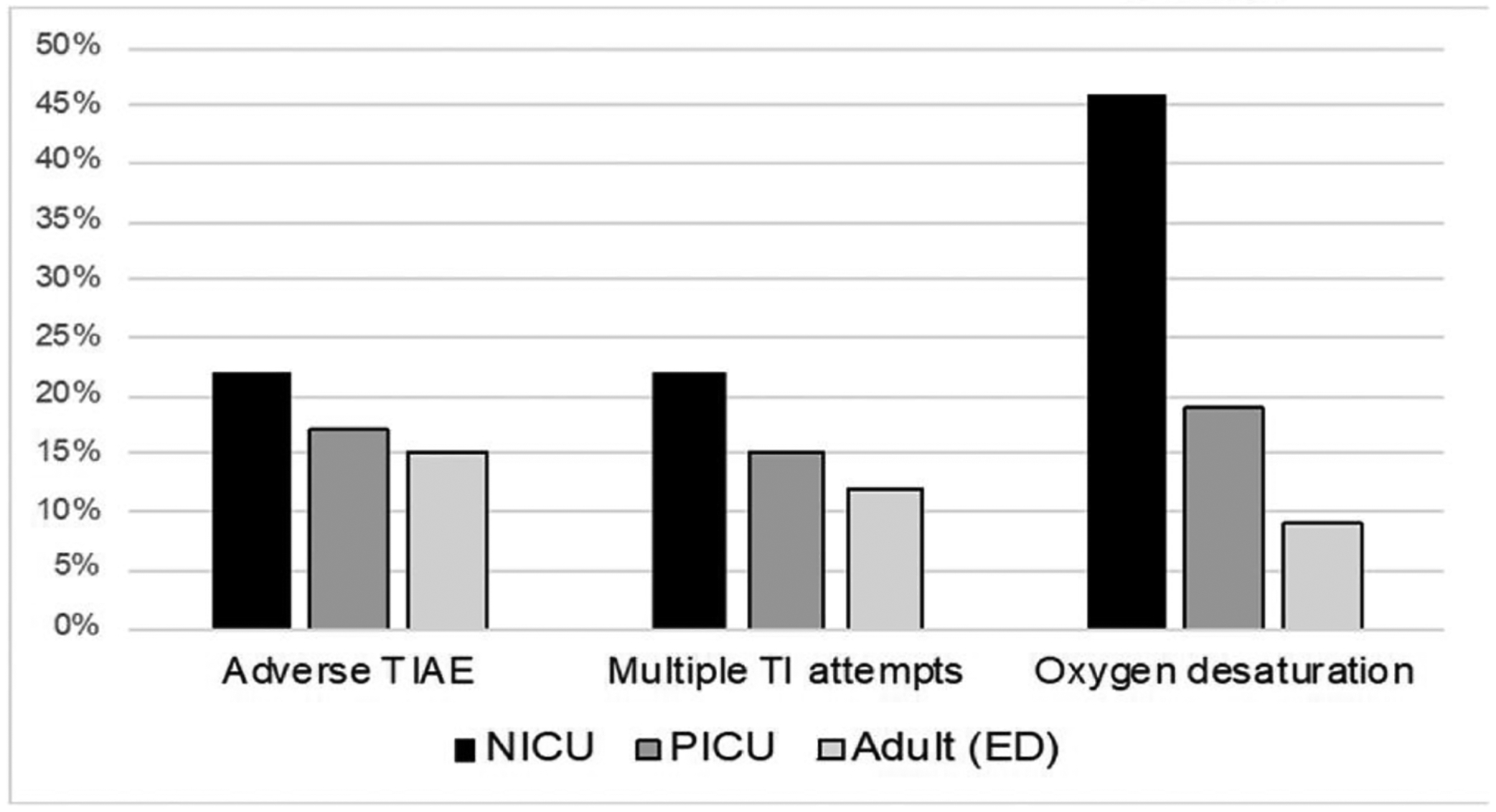

In addition to suboptimal success rates, adverse events complicate 18% of neonatal intubations, with rates ranging from 9–50% across centers.5, 30–32 Neonates experience much higher rates of tracheal intubation associated adverse events compared with older patients, likely due to the unique anatomic and physiologic characteristics described earlier (Figure 1).5,33–37

Figure 1: Tracheal Intubation Safety Events across Settings5,33–37.

TI: Tracheal Intubation, TIAE: Tracheal Intubation Associated Events, NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, PICU: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, ED: Emergency Department

NEAR4NEOS’ comprehensive list of adverse tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) is the most frequently used tool to assess neonatal intubation safety. NEAR4NEOS identifies adverse TIAEs based on standard consensus-based operational definitions and classifies these as severe and non-severe (Table 3). NEAR4NEOS separately reports the rate of severe oxygen desaturation, which is defined as a decline of ≥20% in peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2).

Table 3:

Adverse TIAEs captured in NEAR4NEOS

| Listed in order of frequency | |

|---|---|

| Severe TIAEs | Non-severe TIAEs |

| Esophageal intubation, delayed recognition | Esophageal intubation, immediate recognition |

| Cardiac compressions <1 minute | Dysrhythmia* |

| Laryngospasm | Mainstem intubation |

| Cardiac arrest, patient survived | Gum or dental trauma |

| Emesis with aspiration | Emesis without aspiration |

| Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum | Pain/agitation requiring additional medication |

| Direct airway injury | Epistaxis |

| Hypotension requiring intervention | Lip trauma |

| Cardiac Arrest, patient died | |

Including bradycardia <60 beats per minute without chest compressions

TIAE: Tracheal Intubation Associated Events

In response to the high rates of adverse events, numerous observational studies and quality improvement projects have aimed to identify factors to improve neonatal intubation safety. These factors can be divided into patient, provider, and practice characteristics. For patients, an indication for intubation of ‘unstable hemodynamics’ was independently associated with an increased odds of adverse TIAEs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 3.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.59–9.35) in an observational study of 2607 intubations across 10 sites.5 In a single center study, Glenn et al. demonstrated that increased chronological age and decreased weight at the time of intubation were associated with an increased aOR of adverse events.31

Provider training level has inconsistently been associated with TIAEs.38–40 In two single center observational studies, an attending level provider was associated with a decreased aOR of any TIAE as compared to a resident provider.39,40 Conversely, in a study of 2608 intubations across 11 sites, Johnston et al. demonstrated no association between provider training level and adverse TIAEs.38

Modifiable practice characteristics associated with decreased TIAEs include muscle relaxant premedication, video laryngoscopy, decreased number of intubation attempts, and improved preparation. The use of muscle relaxant premedication has consistently been associated with a decreased odds of TIAEs across numerous multicenter and single center observational studies.5,23, 39–41 These associations remain significant after adjusting for patient, provider, and practice characteristics. In a study of 2260 neonatal intubations across 11 centers, Ozawa et al. demonstrated the use of muscle relaxant premedication was associated with a significantly decreased aOR of any adverse TIAE compared with no premedication (aOR 0.47, 95% CI 0.34–0.67).23 Interestingly, the use of sedation premedication alone was associated with an increased aOR of any adverse TIAE compared with no premedication (aOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.11–1.96).23 The authors postulate this may have been due to adverse effects of the medications (such as chest wall rigidity or decreased upper airway tone) or insufficient doses to achieve optimal intubating conditions.

The use of the video laryngoscope is independently associated with decreased odds of adverse TIAEs across multiple observational studies.5,39,40,28

In two multicenter studies, an increased number of intubation attempts was independently associated with adverse TIAEs.5,42 In a study of 7708 intubations across 17 sites, Singh et al. demonstrated significant increase in the aOR of any TIAE, a severe TIAE, and severe desaturation with each additional attempt.42 Thus, factors that improve intubation success are also likely to improve intubation safety.

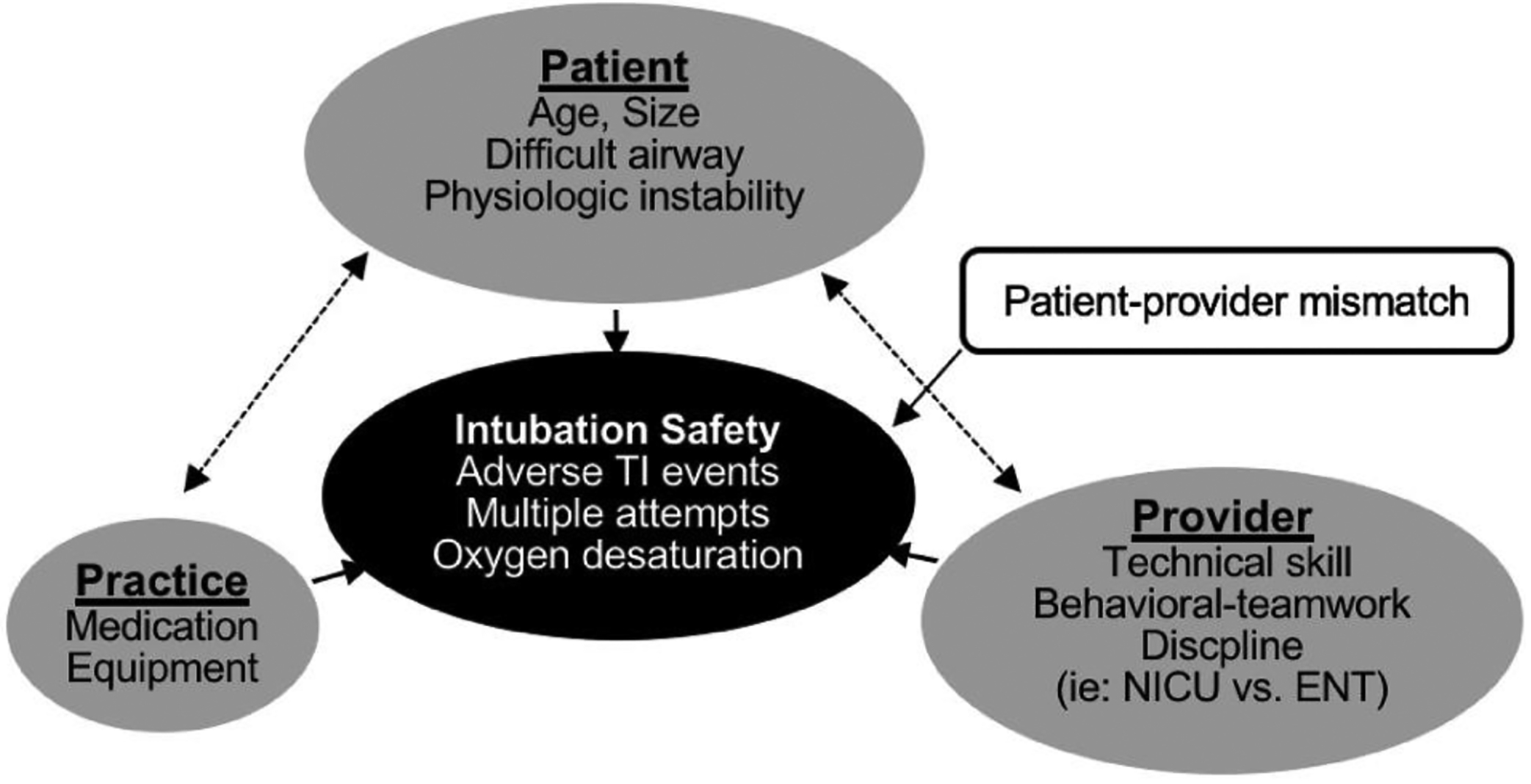

Figure 2 demonstrates our conceptual model of the relationship between patient, provider, and practice factors to improve intubation outcomes. Strategies to improve intubation safety should focus on increasing the use of established interventions to reduce adverse events and ensuring the patient and provider are well matched. Two quality improvement initiatives showed improved rates of adverse events after implementation of interventions to promote evidence-based practices.32,43 Hatch et al. demonstrated a decrease in adverse events from 46% to 36% with the implementation of an intubation checklist used immediately prior to intubation.32 Herrick et al. implemented a prospective individualized airway bundle to improve communication and preparation for neonates at risk for intubation, resulting in a 66% decrease in severe TIAEs.43 The ongoing Optimizing Intubation Outcomes and Neonatal Safety (OPTION SAFE) trial builds on the single center project led by Herrick. OPTION SAFE will assess the impact of a personalized intubation safety bundle on intubation adverse events across eight NEAR4NEOS centers.44

Figure 2:

Conceptual model of factors associated with intubation safety

Despite the number of modifiable practice factors identified to improve neonatal tracheal intubation safety, no factors have consistently improved desaturation events. Apneic oxygenation, defined as the application of free-flowing oxygen during the apneic phase of laryngoscopy and intubation, prevents or delays oxygen desaturation during intubation among older children and adults.45–47 Apneic oxygenation during neonatal intubation represents a potential promising intervention to reduce rates of desaturation. Two trials to date have demonstrated mixed results with the use of nasal high flow therapy to deliver apneic oxygenation. Hodgson et al. demonstrated a significant improvement in their primary outcome of first attempt success without physiological instability (50% versus 31%). Neonates undergoing TI in the delivery room or in the neonatal unit were randomized to 8 L/min nasal high flow therapy versus standard care (no additional support) during intubation. The trial included 251 intubations among 202 neonates with a median post menstrual age of 27.9 weeks. It is important to note that this was a trial of procedural (not apneic) oxygenation, as not all patients in that trial received muscle relaxant premedication.48 In a smaller pilot trial, Foran et al. showed no difference in the primary outcome of duration of oxygen desaturation, however the trial was not powered to detect a difference.49 This trial included 50 intubations among 43 neonates in the neonatal unit. Neonates were randomized to 6 L/min nasal high flow or to a control sham procedure where nasal cannulae were placed but no flow provided. A third ongoing trial, Providing Oxygen during Intubation in the NICU Trial (POINT), is underway.50 POINT will assess the impact of apneic oxygenation administered via regular (non-humidified) nasal cannula on the primary outcomes of magnitude of desaturation during premedicated intubation in the NICU setting.

Conclusion:

Neonatal endotracheal intubation is a challenging procedure with suboptimal success and adverse event rates. Strategies to improve intubation success are often associated with improved safety. It is imperative to systematically track intubation outcomes to understand both universal and site-specific barriers to intubation safety. Methods to improve intubation safety include ensuring the intubation provider and situation are appropriately matched, the increased adoption of evidence-based practices such as muscle relaxant premedication and video laryngoscope, and potentially new interventions such as procedural oxygenation.

Practice Points:

Neonatal tracheal intubation success and adverse event rates are suboptimal.

Systematically tracking intubation outcomes can identify universal and site specific barriers to intubation success and safety.

Muscle relaxant premedication and video laryngoscopy are associated with improved neonatal intubation safety.

New strategies with the potential to improve intubation safety include procedural oxygenation and prospective airway bundles.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Durrmeyer X, Daoud P, Decobert F et al. Premedication for neonatal endotracheal intubation: results from the epidemiology of procedural pain in neonates study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2013; 14: e169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walls RM, Brown CA, Bair AE, Pallin DJ Emergency Airway Management: A Multi-Center Report of 8937 Emergency Department Intubations. J Emerg Med 2011; 41(4): 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishisaki A, Ferry S, Colborn S et al. Characterization of tracheal intubation process of care and safety outcomes in a tertiary pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012; 13: e5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishisaki A, Turner DA, Brown CA, Walls RM, Nadkarni VM, Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. A National Emergency Airway Registry for children: landscape of tracheal intubation in 15 PICUs. Crit Care Med 2013; 41: 874–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foglia EE, Ades A, Sawyer T et al. Neonatal Intubation Practice and Outcomes: An International Registry Study. Pediatrics 2019; 143(1): e20180902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijayasekaran S Pediatric Airway Pathology. Front Pediatr 2020; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann RP, von Ungern-Sternberg BS The neonatal lung - physiology and ventilation. Wolf A, ed. Paediatr Anaesth 2014; 24(1): 10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel R, Lenczyk M, Hannallah RS, McGill WA. Age and the onset of desaturation in apnoeic children. Can J Anaesth 1994; 41(9): 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders RC, Giuliano JS, Sullivan JE et al. Level of trainee and tracheal intubation outcomes. Pediatrics 2013; 131: e821–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CA, Bair AE, Pallin DJ, Walls RM Techniques, Success, and Adverse Events of Emergency Department Adult Intubations. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 65(4): 363–370.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Donnell CPF, Kamlin COF, Davis PG, Morley CJ Endotracheal intubation attempts during neonatal resuscitation: success rates, duration, and adverse effects. Pediatrics 2006; 117: e16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haubner LY, Barry JS, Johnston LC et al. Neonatal intubation performance: room for improvement in tertiary neonatal intensive care units. Resuscitation 2013; 84: 1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leone TA, Rich W, Finer NN. Neonatal intubation: success of pediatric trainees. J Pediatr 2005; 146: 638–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downes KJ, Narendran V, Meinzen-Derr J, McClanahan S, Akinbi HT. The lost art of intubation: assessing opportunities for residents to perform neonatal intubation. J Perinatol 2012; 32: 927–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Escobedo MB et al. Part 13: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2015; 132(18 Suppl 2): S543–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans P, Shults J, Weinberg DD et al. Intubation Competence During Neonatal Fellowship Training. Pediatrics 2021; 148(1): e2020036145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray MM, Rumpel JA, Brei BK et al. Associations of Stylet Use during Neonatal Intubation with Intubation Success, Adverse Events, and Severe Desaturation: A Report from NEAR4NEOS. Neonatology 2021; 118(4): 470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gariépy-Assal L, Janaillac M, Ethier G et al. A tiny baby intubation team improves endotracheal intubation success rate but decreases residents’ training opportunities. J Perinatol 2023; 43(2): 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar P, Denson SE, Mancuso TJ, Newborn C on F and, Medicine S on A and P. Premedication for Nonemergency Endotracheal Intubation in the Neonate. Pediatrics 2010; 125(3): 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durrmeyer X, Walter-Nicolet E, Chollat C et al. Premedication before laryngoscopy in neonates: Evidence-based statement from the French society of neonatology (SFN). Front Pediatr 2022; 10: 1075184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joyce K, Mimoglu E, Mohamed B, Sathiyamurthy S, Banerjee J. 695 A National survey of Premedication practices for Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation and LISA (NeoPRINT Survey). Arch Dis Child 2022; 107: A158–A159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter-Nicolet E, Marchand-Martin L, Guellec I et al. Premedication practices for neonatal tracheal intubation: Results from the EPIPPAIN 2 prospective cohort study and comparison with EPIPPAIN 1. Paediatr Neonatal Pain 2021; 3(2): 46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozawa Y, Ades A, Foglia EE et al. Premedication with neuromuscular blockade and sedation during neonatal intubation is associated with fewer adverse events. J Perinatol 2019; 39(6): 848–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts KD, Leone TA, Edwards WH, Rich WD, Finer NN Premedication for nonemergent neonatal intubations: a randomized, controlled trial comparing atropine and fentanyl to atropine, fentanyl, and mivacurium. Pediatrics 2006; 118(4): 1583–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Shea JE, Thio M, Kamlin CO et al. Videolaryngoscopy to Teach Neonatal Intubation: A Randomized Trial.Pediatrics 2015; 136: 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moussa A, Luangxay Y, Tremblay S et al. Videolaryngoscope for Teaching Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 2016; 137(3): e20152156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lingappan K, Neveln N, Arnold JL, Fernandes CJ, Pammi M. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023; 5(5): CD009975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moussa A, Sawyer T, Puia-Dumitrescu M et al. Does videolaryngoscopy improve tracheal intubation first attempt success in the NICUs? A report from the NEAR4NEOS. J Perinatol 2022; 42(9): 1210–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamlin COF, O’Connell LAF, Morley CJ et al. A randomized trial of stylets for intubating newborn infants. Pediatrics 2013; 131: e198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatch LD, Grubb PH, Lea AS et al. Endotracheal Intubation in Neonates: A Prospective Study of Adverse Safety Events in 162 Infants. J Pediatr 2016; 168: 62–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glenn T, Sudhakar S, Markowski A, Malay S, Hibbs AM. Patient Characteristics Associated with Complications During Neonatal Intubations. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021; 56(8): 2576–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatch DL, Grubb PH, Lea AS et al. Interventions to improve patient safety during intubation in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics 2016; 138(4): e20160069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishisaki A, Lee A, Li S et al. Sustained Improvement in Tracheal Intubation Safety Across a 15-Center Quality-Improvement Collaborative: An Interventional Study From the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children Investigators. Crit Care Med 2021; 49(2): 250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S, Hsieh TC, Rehder KJ et al. Frequency of Desaturation and Association with Hemodynamic Adverse Events during Tracheal Intubations in PICUs. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2018; 19(1): e41–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li S, Hsieh TC, Rehder KJ et al. Frequency of Desaturation and Association with Hemodynamic Adverse Events during Tracheal Intubations in PICUs. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2018; 19(1): e41–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.April MD, Arana A, Pallin DJ et al. Emergency Department Intubation Success With Succinylcholine Versus Rocuronium: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. Ann Emerg Med 2018; 72(6): 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JH, Turner DA, Kamat P et al. The number of tracheal intubation attempts matters! A prospective multi-institutional pediatric observational study. BMC Pediatr 2016; 16(1): 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston L, Sawyer T, Ades A et al. Impact of Physician Training Level on Neonatal Tracheal Intubation Success Rates and Adverse Events—A report from National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates (NEAR4NEOS). Neonatology 2021; 118(4): 434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foglia EE, Ades A, Napolitano N, Leffelman J, Nadkarni V, Nishisaki A. Factors Associated with Adverse Events during Tracheal Intubation in the NICU. Neonatology 2015; 108(1): 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pouppirt NR, Nassar R, Napolitano N et al. Association Between Video Laryngoscopy and Adverse Tracheal Intubation-Associated Events in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Pediatr 2018; 201: 281–284.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neches SK, Brei BK, Umoren R et al. Association of full premedication on tracheal intubation outcomes in the neonatal intensive care unit: an observational cohort study. J Perinatol 2023; 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh N, Sawyer T, Johnston LC et al. Impact of multiple intubation attempts on adverse tracheal intubation associated events in neonates: a report from the NEAR4NEOS. J Perinatol 2022; 16: 1221–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herrick HM, Pouppirt N, Zedalis J et al. Reducing Severe Tracheal Intubation Events Through an Individualized Airway Bundle. Pediatrics 2021; 148(4): e2020035899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foglia EE Optimizing Tracheal Intubation Outcomes and Neonatal Safety (OPTION SAFE). ClinicalTrials.gov 2023; NCT05838690.

- 45.Grude O, Solli HJ, Andersen C, Oveland NP. Effect of nasal or nasopharyngeal apneic oxygenation on desaturation during induction of anesthesia and endotracheal intubation in the operating room: A narrative review of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Anesth 2018; 51: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steiner JW, Sessler DI, Makarova N et al. Use of deep laryngeal oxygen insufflation during laryngoscopy in children: a randomized clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2016; 117(3): 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Humphreys S, Lee-Archer P, Reyne G, Long D, Williams T, Schibler A. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) in children: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2017; 118(2): 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodgson KA, Owen LS, Kamlin COF et al. Nasal High-Flow Therapy during Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(17): 1627–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foran J, Moore CM, Ni Chathasaigh CM, Moore S, Purna JR, Curley A. Nasal high-flow therapy to Optimise Stability during Intubation: the NOSI pilot trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023; 108(3): 244–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herrick HM, O’Reilly M, Lee S et al. Providing Oxygen during Intubation in the NICU Trial (POINT): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial in the neonatal intensive care unit in the USA. BMJ Open 2023; 13(4): e073400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]