Abstract

Purpose

Published data on outcomes among adolescents newly initiating antiretroviral treatment in the Latin American context is sparse. We estimated the frequency of sustained retention with viral load suppression (i.e., successful transition) and identified predictors of successful transition into adult care among youth (14 to 21 years) with recently-acquired HIV in Lima, Peru.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted among 184 adolescents and young adults who initiated antiretroviral therapy in an adult public sector HIV clinic between June 2014 and June 2019. Sustained retention (no loss-to-follow-up or death) with viral suppression was calculated for the first 12 and 24 months following treatment initiation. We conducted regression analyses to assess factors associated with successful transition to adult HIV care, including gender, age, occupation, nationality, pregnancy, samesex sexual behavior, presence of treatment supporter, number of living parents, and social risk factors that may adversely influence health (e.g., lack of social support, economic deprivation).

Results

Patients were predominantly male (n=167, 90.8%). Median age was 19 years (IQR:18–21). Frequency of sustained retention with viral load suppression was 42.4% (78/184) and 35.3% (30/85) at 12 and 24 months following treatment initiation. In multivariable analyses, working and/or studying was inversely associated with successful transition into adult care at 12 months; number of known living parents (RR:2.20; 95%CI: 1.12, 4.34) and absence of social risk factors (RR:1.68; 95%CI 0.91; 3.11) were positively associated with successful transition at 24 months.

Discussion

Sustained retention in HIV care was uncommon. Parental support and interventions targeting social risk factors may contribute to successful transition into adult HIV care in this group.

Keywords: youth, adherence, transition, support, Peru

In adolescents and young adults, newly-diagnosed HIV may lead to a first experience with routine health care. This means that adolescents and young adults who initiate HIV care in an adult clinic will need to navigate the logistics of a complex health system and meet new medical providers in an environment that is unfamiliar, all while simultaneously confronting the emotions of a new HIV diagnosis.1,2 Adult HIV providers may be unprepared to contend with developmental and behavioral issues of adolescence and young adulthood, including mental health morbidity, disclosure to loved ones, and the potential consequences of sexual debut such as condom negotiation, unprotected sex leading to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, and pregnancy.3 Furthermore, the adolescent developmental stage is characterized by risk-taking, reward-seeking, and a strong influence from peer networks, all of which may interfere with retention in care and treatment.4,5 Thus, a complex confluence of factors emerges to challenge adherence, retention, and HIV viral load suppression at a time when adolescents and young adults are expected to assume autonomy in the management of a newly-diagnosed condition.6,7

To date, the majority of HIV care transition studies have focused on adolescents and young adults living with HIV (ALWH) since birth or early childhood who are shifting from a pediatric to adult care provider; however, there is growing recognition that this HIV care transition also applies to those diagnosed with HIV in adolescence or young adulthood, a group that often initiates HIV care directly in an adult clinic.8 This latter transition experience is particularly relevant in Latin America where the majority of new infections occur between the ages of 18 and 29.9 The health transition experiences and needs of adolescents who transition to adult care from a pediatric clinic and those who initiate HIV care directly in an adult clinic may differ, in part due to the experience of receiving HIV care from a pediatric provider, but also because those who acquire HIV in late adolescence or young adulthood face a distinct set of challenges. For example, in addition to the struggles of newly-diagnosed HIV and adjustment to new medications, those diagnosed with HIV during adolescence or young adulthood are more likely to face sexual- and gender-based stigma, experience substance use disorders, and have a history of trauma and mental health concerns.10–18 Additionally, while they are more likely to be in the early stages of HIV, and thus less likely to be dealing with long-term or chronic sequelae, they may have difficulties accepting their diagnosis and continue to engage in sexual behaviors that put their partners at risk of HIV.19

Understanding treatment outcomes among youth who are diagnosed with HIV during adolescence is critical for the design of tailored interventions; however there is scant data in this group, especially from Latin America. As a first step toward addressing this research gap, we estimated the frequency of sustained retention with viral load suppression among newly diagnosed ALWH who were initiating treatment in an adult public sector HIV clinic in Lima, Peru, and identified patient-level predictors of a successful transition into adult HIV care.

METHODS

Study Setting

Peru has an estimated 97,000 people living with HIV. Between 2016 and 2020, 28% of new HIV case notifications were between the ages of 15 to 24 years.20 Our study was conducted in the capital city of Lima, where an estimated 80% of all people living with HIV reside.21,22 New HIV diagnoses in adolescents between the ages of 15 to 19 years increased by nearly 75% between the periods of 2009 to 2013 and 2014 to 2018.9 The majority of new infections in young people occur among men who have sex with men (MSM) and young transgender women (TGW), in whom the prevalence exceeds 10% and 20% respectively.21 In addition, Peru has welcomed an estimated 1.28 million Venezuelan migrants since 2016, with 80% settling in Lima.23 This influx has led to an increased representation of Venezuelans living with HIV in Lima. In 2019, the largest HIV program in the country reported that Venezuelans represented 18.7% of new HIV infections.24,25

In Peru, the transition to an adult HIV clinic typically occurs between the ages of 15 to 18; however, newly-diagnosed adolescents often enter directly into adult HIV care, bypassing the pediatric clinic. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been available free of charge since 2004 and, during the study period, was primarily delivered at public sector tertiary care facilities. National guidelines specified that patients newly initiating ART should identify a treatment supporter who could offer emotional and adherence support, and viral load and CD4 cell counts were to be measured routinely every six months.26,27 9/2/2023 3:13:00 PM New patients underwent a psychological evaluation with a Ministry of Health psychologist, at which time a standardized form was completed to record mental health symptomatology and possible diagnoses.

Study Design & Participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adolescents and young adults, aged 14–21 years who initiated antiretroviral therapy for the first time in an adult, high-burden public sector HIV clinic hospital in Lima, Peru from June 2014 through Februrary 2019. ALWH were followed from ART initiation until the earliest of death, loss-to-follow-up, March 1st, 2020 (start of COVID-19 pandemic), 24 months post-transition or the date of data collection. Each adolescent was eligible to have completed a minimum of 12 months of follow-up. ALWH who disengaged from treatment were retrospectively followed until the time of data collection to determine whether they returned to care.

Data Collection

Study staff collected patient data from clinical charts including sociodemographic information, HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts, clinic visit attendance, mental health morbidity, living situation, presence of support agent, HIV diagnosis disclosure information, sexual and gender identity, ART regimen, and social factors that may adversely influence health (e.g., substance abuse, economic deprivation, lack of social support, violence, legal problems). These data were abstracted from standardized clinical forms that captured this information and supplemented by health provider notes. To standardize mental health symptomatology and diagnoses, clinical notes were reviewed and doubly coded to the most likely ICD-9 code, by a local Peruvian psychologist and U.S.-based clinical social worker with more than two decades of experience working in Peru. Initial coding was blinded and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was sustained retention in treatment with viral load suppression within 12 and 24, months of ART initiation. Only patients eligible to have completed the full follow-up time were included in each respective analysis. Patients were considered retained with viral suppression (‘successful transition’) if they were alive and on treatment (i.e. no disengagement from care) for the full duration of follow-up to that point, had at least one suppressed viral load result in the past year, and no unsuppressed viral load result to that point. Disengagement from care was defined as missing ART treatment for at least 60 days and was identified based on clinician report and/or having missed pill-pick-up appointments for at least 60 days. Unsuccessful transition was defined based on disengagement from care, death, or no evidence of a suppressed viral load (i.e., detectable viral load > than 40 copies/mL or no viral load testing).

Statistical Analyses

We report the frequency of primary outcomes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals, using exact methods as needed. We estimated relative risks for potential baseline factors associated with successful transition during the 12-month and 24-month periods using Poisson regression with robust variance. Factors considered included age at transition, gender, calendar year of transition (2014–2016, 2017, 2018, 2019), activity (none, both works and studies, works only, studies only), living alone, presence of treatment supporter, mental health morbidity, number of known living parents, having no social risk factors, sexual identity (MSM or not), nationality (Peruvian or Venezuelan), and baseline CD4 count. If the status of a parent was unknown (i.e., due to estrangement) they were not counted as a known living parent. Factors correlated with successful transition at a p-value <0.20 at either time point (12 or 24 months) were included in the multivariable analyses. We used this liberal threshold because it was likely to capture relevant factors as well as potential confounders of those factors. The small number of patients that transferred out were excluded from regression analyses for the period corresponding to transfer and thereafter. We accounted for the small amount of missing data using the missing indicator method. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 16 and SAS version 9.4.

IRB Approval / Compliance of Ethical Standards

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Ethics approval was granted in Peru at Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza and at Harvard Medical School in the United States.

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics

184 patients eligible to have completed at least 12 months of follow-up at the time of the chart review were included for analysis. Among this study population, 90.8% (n=167) identified as male (Table 1). The median age at ART initiation was 19 years (25th percentile = 18, 75th percentile = 21), and 16 patients were younger than 18 years of age. The median time from diagnosis date to start of ART treatment was 66 days (25th percentile = 33, 75th percentile = 148). Fourteen patients (7.6%) were Venezuelan. Many were students (36.0%), employed (38.2%), or both (11.8%), and a majority reported having a support agent (76.4%). Twenty-seven ALWH (14.7%) lived alone.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among newly diagnosed adolescents and young adults living with HIV in urban Peru, (N=184)a

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 167 (90.8) |

| Median age at ART initiation, years (IQR) | 19 (18, 21) |

| Median time from diagnosis to ART transition, days, (IQR) | 66 (33, 148) |

| Venezuelan nationality | 14 (7.6) |

| Pregnant at ART initiation, among females (N=17)b | 3 (16.7) |

| MSM, among men (N =167)c | 152 (91.0) |

| Year of ART initiation | |

| 2014 | 1 (0.5) |

| 2015 | 5 (2.7) |

| 2016 | 26 (14.1) |

| 2017 | 57 (31.0) |

| 2018 | 79 (42.9) |

| 2019 | 16 (8.7) |

| Daily Activity (N= 178) | |

| None | 25 (14.0) |

| Both studies & works | 21 (11.8) |

| Only works | 68 (38.2) |

| Only studies | 64 (36.0) |

| Living situation | |

| Alone | 27 (14.7) |

| With parent(s) | 104 (56.5) |

| With other family member(s), but not with parent | 28 (15.2) |

| With partner or significant other | 19 (10.3) |

| Has a treatment supporter (N = 178) | 139 (76.4) |

| HIV diagnosis disclosure | |

| No one | 9 (4.9) |

| At least one parent | 129 (70.1) |

| Sibling | 44 (23.9) |

| Partner | 29 (15.8) |

| Other | 40 (21.7) |

| Status of parents | |

| Mother and father both dead or status unknownb | 30 (16.3) |

| One parent alive, other parent deceased or status unknownd | 42 (22.8) |

| Both parents alive | 112 (60.9) |

| No social risk factors | 29 (15.8) |

| Mode of transmission, sexual | 184 (100.0) |

| Baseline CD4 count (N = 178) | |

| < 50 | 5 (2.8) |

| 51 – 200 | 20 (11.2) |

| 201 – 500 | 95 (53.4) |

| >500 | 58 (32.6) |

| Antiretroviral regimen | |

| TDF 3TC EFV | 66 (35.9) |

| EFV FTC TDF | 101 (54.9) |

| Other | 17 (10.2) |

| Possible mental health diagnosise | 46 (25.0) |

N=184 unless specified otherwise

Pregnant women represented 1.6% of the entire cohort of 184.

MSM represented 82.6% of the entire cohort of 184.

Unknown status of mother only: 0, Unknown status of father only: 42, Unknown status of both: 29

Reviewers arrived at this diagnostic code based on available data; however, insufficient data were available (e.g., duration of symptoms) to make a definitive diagnostic code assignment. Possible mental health diagnoses included adjustment disorders (n=7), schizophrenia (n=1), depressive disorders (n=5 diagnosed, n=31 probable), anxiety disorders (n=3), mixed receptive-expressive language disorder (n=1), and oppositional defiant disorder (n=1)

Frequency of successful transition within 12 and 24months

We observed a consistent decrease in sustained retention with viral suppression over the course of treatment (Table 2). The frequency of sustained retention with viral load suppression was 42.4%, and 35.3% at 12 and 24 months, respectively. Among those who were retained in care, 67.6% (100/148) and 77.8% (42/54) had viral load results at 12 and 24 months respectively, and of those with viral loads, 78.0% (78/100) and 71.4% (30/42) were suppressed at these time points, respectively. Of 48 ALWH who became lost-to-follow-up, 12 (25%) were observed to have returned to care during the follow-up period.

Table 2.

Frequency of treatment retention and successful viral load suppression at 12 and 24 months among adolescents and young adults with recently diagnosed HIV in Lima, Peru.

| Outcomes n (%, 95%CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | N at risk* | Retained w/ VL suppression | Retained w/ no VL data | Retained w/detectable VL | Not retained | Transferred out |

| 12 months | 184 | 78 (42.4, 35.4–49.7) | 48 (26.1, 20.2–33.0) | 22 (12.0, 8.0–17.5) | 29 (15.8, 11.2–21.8) | 7 (3.80, 1.8–7.8) |

| 24 months | 85 | 30 (35.3, 25.8–46.1) | 12 (14.1, 8.1–23.4) | 12 (14.1, 8.1–23.4) | 29 (34.12, 24.7–44.9) | 2 (2.4, 0.6–9.1) |

An adolescent was considered at risk if they were eligible to have completed the corresponding duration of follow-up, based on the ART initiation date and date of chart review.

Factors associated with successful transition

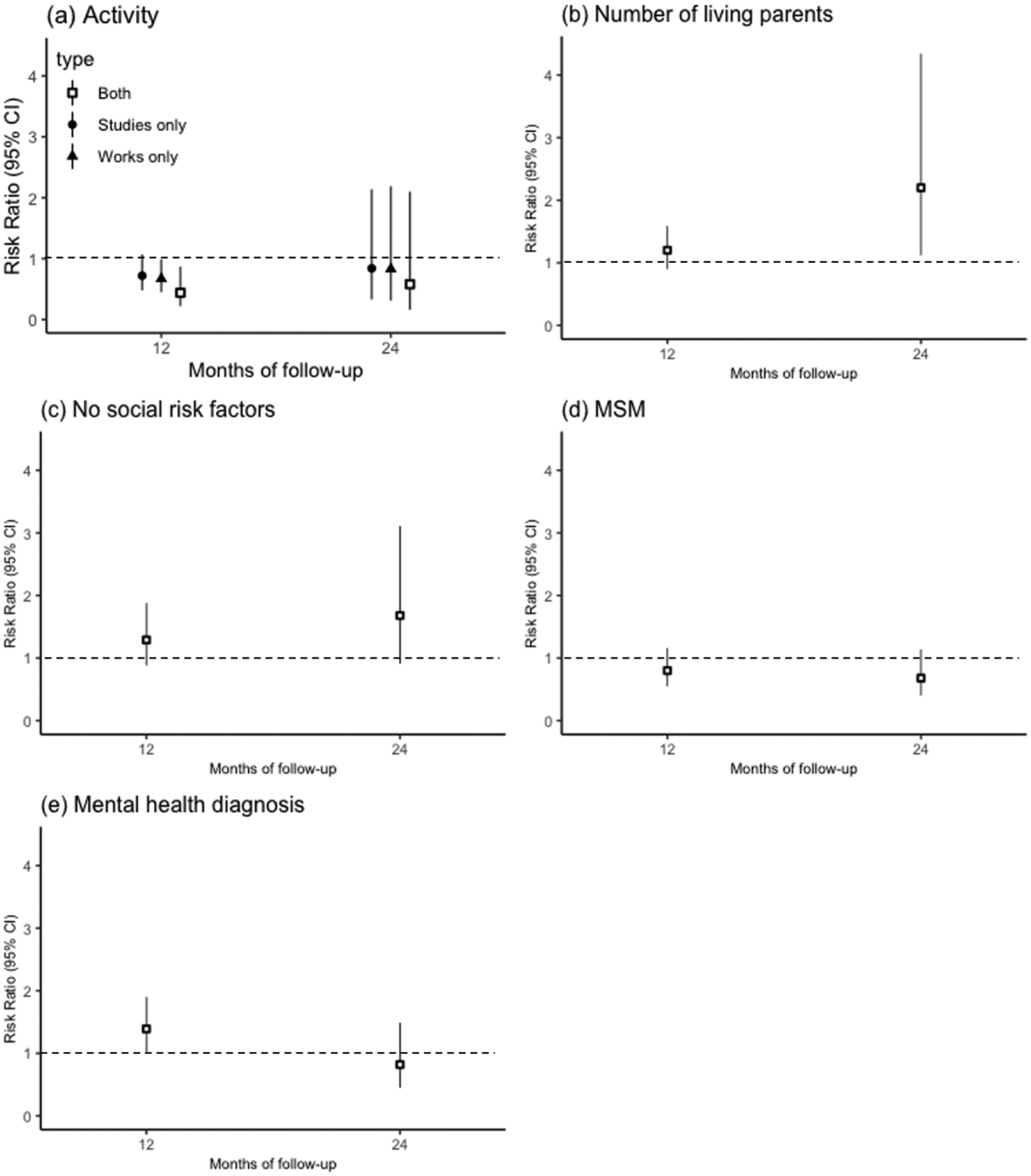

Univariable analyses of factors associated with successful transition within 12 and 24 months are shown in Table 3. We found no associations between calendar year and successful transition outcomes. In the multivariable analyses at 12-months, we found inverse associations between successful transition and working (RR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.99), studying (RR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.48, 1.07), and both working and studying (RR: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.22, 0.87), relative to neither working nor studying. Having a mental health diagnosis note was positively associated with successful transition at 12-months (RR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.90) (Figure 1, Appendix Table A1). In the multivariable analyses at 24-months, the number of known living parents (0, 1, or 2) (RR: 2.20; 95% CI: 1.12, 4.34) and having no noted social risk factors were positively associated with successful transition (RR: 1.68; 95% CI: 0.91, 3.11; Figure 1, Appendix Table A1).

Table 3.

Univariable analyses of baseline predictors of successful transition at 12 and 24 months among adolescents and young adults recently diagnosed with HIV in Lima, Peru.

| 12-months (N=177)a |

24-months (N=83)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | nb | Risk ratio (95%CI) | P value | nb | Risk ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Age at transition (years) | -- | 0.97 (0.86, 1.10) | 0.64 | -- | 1.01 (0.83,1.24) | 0.90 |

| Calendar year of transition | -- | 1.00 (0.84, 1.18) | 0.98 | -- | 1.10 (0.76, 1.91) | 0.44 |

| Male | 160 | 1.08 (0.59, 1.96) | 0.80 | 77 | 0.70 (0.30, 1.66) | 0.42 |

| Activity | ||||||

| Neither works nor studies | 24 | Reference | 13 | Reference | ||

| Works and studies | 21 | 0.46 (0.22, 0.96) | 0.04 | 8 | 0.81 (0.19, 3.50) | 0.78 |

| Works | 68 | 0.73 (0.49, 1.09) | 0.13 | 36 | 1.35 (0.55, 3.36) | 0.51 |

| Studies | 58 | 0.69 (0.45, 1.06) | 0.09 | 23 | 1.13 (0.42, 3.06) | 0.81 |

| Living alone | 23 | 0.77 (0.43, 1.38) | 0.37 | 9 | 1.26 (0.57, 2.81) | 0.56 |

| No support agentc | 37 | 1.14 (0.77, 1.67) | 0.52 | 9 | 0.91 (0.34, 2.43) | 0.86 |

| Mental health diagnosis | 45 | 1.47 (1.06, 2.04) | 0.02 | 33 | 0.76 (0.41, 1.41) | 0.38 |

| Number of known living parents | -- | 1.24 (0.96, 1.61) | 0.10 | -- | 2.40 (1.23, 4.66) | 0.01 |

| No social risk factors | 28 | 1.37 (0.94, 2.00) | 0.096 | 14 | 2.11 (1.24, 3.60) | 0.01 |

| MSM | 145 | 0.93 (0.61, 1.40) | 0.72 | 68 | 0.62 (0.34, 1.09) | 0.096 |

| Venezuelan nationality | 13 | 1.24 (0.73, 2.12) | 0.42 | 1 | --- | --- |

| Baseline CD4 count | ||||||

| < 50 | 5 | Reference | 4 | Reference | ||

| 51 – 200 | 19 | 1.58 (0.24, 10.34) | 0.63 | 5 | 1.60 (0.21, 12.07) | 0.65 |

| 201 – 500 | 91 | 2.31 (0.39, 13.58) | 0.36 | 49 | 1.47 (0.26, 8.43) | 0.67 |

| >500 | 56 | 2.59 (0.44, 15.39) | 0.29 | 25 | 1.44 (0.24, 8.60) | 0.69 |

Seven and two individuals who transferred out were excluded from 12- and 24-month analyses, respectively

Provided for binary and categorical variables; not provided for continuous variables

Missing indicator method used to account for missing data in this variable

Figure 1.

Multivariable analyses of baseline predictors of successful transition at 12 and 24 months among adolescents and young adults recently diagnosed with HIV in Lima, Peru: (a) Activity (reference group is neither works nor studies); (b) Number of known living parents; (c) No note of known social risk factors; (d) MSM; (e) Any note of mental health diagnosis. Note: Factors significantly correlated with successful transition (p <0.20) at any time point were included in the multivariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

Through this retrospective cohort study, we estimated the frequency of retention with viral load suppression, and associated factors, among adolescents and young adults newly initiating ART at a public sector adult HIV clinic in urban Peru. We saw consistent declines in the frequency of sustained retention with viral load suppression during the two years of treatment. Among those that were retained, lack of a viral load test result and lack of viral suppression were common. The “95-95-95” global target to end the AIDS epidemic aims to have 95% of those with living with HIV be diagnosed, 95% of those diagnosed be receiving treatment, and 95% of those with treatment having suppressed viral loads by 2030.28 Studies have revealed gaps in this HIV cascade among younger individuals who have transitioned to adult care, to which our results, and others from Peru, are consistent, highlighting the critical need for tailored interventions for this group.13,17,29–33

Barriers to successful linkage to care among newly diagnosed ALWH include providers’ failure to address adolescent concerns, as well as the difference in care cultures between the HIV clinics.34 Negative perceptions or concerns about adult HIV clinics have also been identified as challenges to transition.17 In our study, no single risk factor predicted successful transition across the two follow-up periods; however, having known living parents and having no social risk factors for unfavorable health outcomes facilitated sustained retention with viral load suppression for the first two years of treatment, highlighting the critical importance of differentiated service interventions that provide more intensive and/or comprehensive support for some ALWH. We also found that the frequency of successful transition was lower in the year following ART initiation for those who reported working, studying, or both working and studying, relative to those who did neither. In Peru, patients often receive ART in centralized tertiary care centers that may be far from home and typically operate during daytime business hours. Thus, patients may need to take time off of work or school to refill medications. In addition, a possible mental health diagnosis in the clinical record was associated with a successful outcome in the first year since ART initiation, a finding at odds with a large body of evidence demonstrating the deleterious effects of mental health morbidity on HIV related outcomes.35–39 Most of those with a mental health diagnosis had a ‘possible’, unconfirmed, diagnosis, thus the data may not be fully reliable. In addition, while all patients were evaluated by a psychologist, in the absence of systematic screening for mental health morbidity, it is possible that some existing mental health conditions were missed. While this result may be a chance finding, those with early mental health diagnoses may be given more attention by providers early on in care or be more likely to be engaged in mental health service utilization; the latter has been associated with retention in care.35 This finding could be explored more fully in a prospective study in which data on symptomatology, diagnoses, communication of diagnoses to the adolescent, and any subsequent treatment are systematically captured.

Our findings highlight the need for interventions to support for ALWH who are newly initiating ART and provide strong motivation for further exploration into the transition experiences among newly diagnosed ALWH in Peru with the goal of ensuring a comprehensive, coordinated, and compassionate model of care during the transition to HIV treatment and beyond. Directly addressing adolescent-specific needs has been associated with successful treatment adherence in the past.40–43 There is increasing recognition of the importance of active engagement by adult HIV care clinics during the transition process to increase coordination and support for adolescents during this critical step in the continuum of care.44 A study among adolescents in Uganda found that having trusting peer educators for treatment, receiving counseling on the transition to adult services, and visiting an adult clinic to prepare for transition were associated with perceived readiness to transition into adult care.45 While these results were from patients who transitioned from pediatric clinics, improving readiness to transition may be critical among newly-diagnosed ALWH who transition directly into adult care as well. In their pilot program optimizing linkage to care in Kenya, Ruria et al. found that active youth engagement and youth-friendly programming for newly-diagnosed adolescents and youth were associated with increased retention in care.42 In Peru, a single-arm pilot study of a community-based differentiated care intervention that aimed to fill gaps in care, provide social and logistical support and build skills during the transition process saw improvements in social support, adherence, and transition readiness, among adolescents with perinatal and recent HIV infection alike.41,46 While there are increasing studies exploring adolescents’ transition experiences and treatment adherence and outcomes, there remains an evidence gap with regard to experiences of adolescents and young adults newly diagnosed with HIV who are engaging in adult care for the first time, particularly in Peru and Latin America.

We did not identify a set of factors that were consistently associated with success across the two time periods. One possible explanation is sampling variability: sample sizes for the two analyses varied based on follow-up time. Limitations of this study relate to its retrospective nature, which precluded systematic collection of many potential correlates of transition and/or engagement in care. And, although ALWH who wished to transfer their care to a different facility would theoretically require a transfer referral from the initial treatment center, we cannot rule out the possibility that some ALWH who were lost from care were in fact receiving treatment elsewhere. The data on absence of viral load testing is difficult to interpret as this may be due to health systems factors (e.g., lack of reagents, viral load not ordered) in addition to patient-level factors. To account for this possibility, we defined successful transition based on the more conservative assumption that ALWH should have had at least one viral load during a one-year period. Additionally, although this work was conducted at a single public sector facility, the study site was a major provider of ART in Lima and is generally thought to be representative of the public sector treatment experience in tertiary care facilities. Thus, our results are likely generalizable to other urban centers in Peru and perhaps beyond. Finally, our definition of retention was based on that used by the Peru National HIV Program, and recent work has shown that retention rates can vary greatly depending on the definition used.47

In conclusion, we found low rates of sustained retention with viral load suppression within the first two years of antiretroviral therapy among adolescents and young adults newly diagnosed with HIV. The development and evaluation of differentiated interventions to support this population, particularly those aiming to address gaps in social support and facilitate the provision of adolescent-friendly care, are of the utmost priority.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS & CONTRIBUTION.

This study identified factors associated with successful transition that may inform future differentiated service interventions to improve outcomes in youth living with behaviorally-acquired HIV. The results support the need for deliberate, adolescent-friendly, comprehensive care models to facilitate successful transitions to adult HIV care.

Funding

This research was entirely supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21AI143365. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Straub DM, Tanner AE. Health-care transition from adolescent to adult services for young people with HIV. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):214–222. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30005-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussen SA, Chakraborty R, Knezevic A, et al. Transitioning young adults from paediatric to adult care and the HIV care continuum in Atlanta, Georgia, USA: A retrospective cohort study: A. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1). doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abadía-Barrero CE, Castro A. Experiences of stigma and access to HAART in children and adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2006;62(5):1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2005.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinberg L Commentary: A Behavioral Scientist Looks at the Science of Adolescent Brain Development. Brain Cogn. 2010;72(1):160. doi: 10.1016/J.BANDC.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tepper V, Zaner S, Ryscavage P. HIV healthcare transition outcomes among youth in North America and Europe: A review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(0):21490. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.4.21490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakkar F, Van der Linden D, Valois S, et al. Health outcomes and the transition experience of HIV-infected adolescents after transfer to adult care in Québec, Canada. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0644-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weijsenfeld AM, Smit C, Cohen S, et al. Virological and Social Outcomes of HIV-Infected Adolescents and Young Adults in The Netherlands Before and After Transition to Adult Care. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(8):1105–1112. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam PK, Fidler S, Foster C. A review of transition experiences in perinatally and behaviourally acquired HIV-1 infection; same, same but different? J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 3):21506. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.4.21506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Situación Epidemiológica Del VIH-Sida En El Perú. Boletín Mensual; 2018. https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/vih/Boletin_2018/diciembre.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cáceres CF, Aggleton P, Galea JT. Sexual diversity, social inclusion and HIV/AIDS. AIDS Lond Engl. 2008;22 Suppl 2:S45–55. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327436.36161.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee On Adolescence. Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):198–203. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LK, Whiteley L, Harper GW, Nichols S, Nieves A, ATN 086 Protocol Team for The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Psychological symptoms among 2032 youth living with HIV: a multisite study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(4):212–219. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conner LC, Wiener J, Lewis JV, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Drug Use Among Adolescents with HIV Infection Acquired Perinatally or Later in Life. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):976–986. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9950-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis JV, Abramowitz S, Koenig LJ, Chandwani S, Orban L. Negative life events and depression in adolescents with HIV: a stress and coping analysis. AIDS Care. 2015;27(10):1265–1274. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1050984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrick A, Stall R, Egan J, Schrager S, Kipke M. Pathways towards risk: syndemic conditions mediate the effect of adversity on HIV risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2014;91(5):969–982. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9896-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandwani S, Koenig LJ, Sill AM, Abramowitz S, Conner LC, D’Angelo L. Predictors of antiretroviral medication adherence among a diverse cohort of adolescents with HIV. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2012;51(3):242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valenzuela JM, Buchanan CL, Radcliffe J, et al. Transition to Adult Services among Behaviorally Infected Adolescents with HIV—A Qualitative Study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(2):134–140. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Thurston IB, et al. Qualitative Comparison of Barriers to Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among Perinatally and Behaviorally HIV-Infected Youth. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(8):1177–1189. doi: 10.1177/1049732317697674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenig LJ, Pals SL, Chandwani S, et al. Sexual Transmission Risk Behavior of Adolescents With HIV Acquired Perinatally or Through Risky Behaviors. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(3):380–390. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f0ccb6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Situación Epidemiológica Del VIH-Sida En El Perú.; 2020. https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/vih/Boletin_2020/febrero.pdf

- 21.UNAIDS. Peru Country Fact Sheet 2019. Published December 17, 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/peru

- 22.Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Situación Epidemiológica Del VIH-Sida En El Perú.; 2021. https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/vih/Boletin_2021/febrero.pdf

- 23.Santisteban AS. Diagnóstico Rápido: Situación de Los Migrantes Venezolanos Con VIH En El Perú. ONUSIDA; 2019. http://onusidalac.org/1/images/2018/diagnostico-rapido-migrantes-con-vihperu.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huerta-Vera GS, Amarista MA, Mejía FA, Graña AB, Gonzalez-Lagos EV, Gotuzzo E. Clinical situation of Venezuelan migrants living with HIV in a hospital in Lima, Peru. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32(12):1157–1164. doi: 10.1177/09564624211024080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNAIDS. Social and Economic Integration of Venezuelan Migrants. Published February 2, 2022. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/fact-sheets/social-and-economic-integration-venezuelan-migrants

- 26.Ministerio de Salud. Norma Técnica de Salud de Atención Integral Del Adulto Con Infección Por El Virus de La Inmunodeficiencia Humana (VIH).; 2014.

- 27.Resolución Ministerial. Published online Diciembre 2020. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1482085/Resoluci%C3%B3n%20Ministerial%20N%C2%B01024-2020-MINSA.PDF

- 28.Ehrenkranz P, Rosen S, Boulle A, et al. The revolving door of HIV care: Revising the service delivery cascade to achieve the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals. PLOS Med. 2021;18(5):e1003651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey H, Cruz MLS, Songtaweesin WN, Puthanakit T. Adolescents with HIV and transition to adult care in the Caribbean, Central America and South America, Eastern Europe and Asia and Pacific regions. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(0):21475. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.4.21475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nassau T, Loabile B, Dowshen N, et al. Factors and Outcomes Associated With Viral Suppression Trajectory Group Membership Among Youth Transitioning From Pediatric to Adult HIV Care. J Adolesc Health. 2022;71(6):737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohn AH, Singtoroj T, Chokephaibulkit K, et al. Long-Term Post-Transition Outcomes of Adolescents and Young Adults Living With Perinatally and Non-perinatally Acquired HIV in Southeast Asia. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(3):471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez CA, Kolevic L, Ramos A, et al. Lifetime Changes in CD4 T-cell count, Viral Load Suppression and Adherence Among Adolescents Living With HIV in Urban Peru. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(1):54–56. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong VJ, Murray KR, Phelps BR, Vermund SH, McCarraher DR. Adolescents, young people, and the 90–90–90 goals: a call to improve HIV testing and linkage to treatment. AIDS Lond Engl. 2017;31(Suppl 3):S191–S194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philbin M, Tanner A, Chambers B, et al. Transitioning HIV-infected adolescents to adult care at 14 clinics across the United States: using adolescent and adult providers’ insights to create multi-level solutions to address transition barriers. AIDS Care. 2017;29:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1338655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooks-Peck CR, Adegbite AH, Wichser ME, et al. Mental Health and Retention in HIV Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2018;37(6):574–585. doi: 10.1037/hea0000606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enane LA, Apondi E, Omollo M, et al. “I just keep quiet about it and act as if everything is alright” - The cascade from trauma to disengagement among adolescents living with HIV in western Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(4):e25695. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krumme AA, Kaigamba F, Binagwaho A, Murray MB, Rich ML, Franke MF. Depression, adherence and attrition from care in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(3):284–289. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haas AD, Ruffieux Y, van den Heuvel LL, et al. Excess mortality associated with mental illness in people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: a cohort study using linked electronic health records. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(10):e1326–e1334. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haas AD, Technau KG, Pahad S, et al. Mental health, substance use and viral suppression in adolescents receiving ART at a paediatric HIV clinic in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(12):e25644. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchwood TD, Malo V, Jones C, et al. Healthcare retention and clinical outcomes among adolescents living with HIV after transition from pediatric to adult care: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1195. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09312-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vargas V, Wong M, Rodriguez CA, et al. Community-Based Accompaniment for Adolescents Transitioning to Adult HIV Care in Urban Peru: a Pilot Study | medRxiv. Accessed February 3, 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.25.21261815v1.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Ruria EC, Masaba R, Kose J, et al. Optimizing linkage to care and initiation and retention on treatment of adolescents with newly diagnosed HIV infection. AIDS Lond Engl. 2017;31(Suppl 3):S253–S260. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zanoni BC, Sibaya T, Cairns C, Lammert S, Haberer JE. Higher retention and viral suppression with adolescent-focused HIV clinic in South Africa. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0190260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanner AE, Philbin MM, Ma A, et al. Adolescent to Adult HIV Health Care Transition From the Perspective of Adult Providers in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(4):434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mbalinda SN, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Lusota DA, Musoke P, Nyashanu M, Kaye DK. Transition to adult care: Exploring factors associated with transition readiness among adolescents and young people in adolescent ART clinics in Uganda. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galea JT, Wong M, Ninesling B, et al. Patient and Provider Perceptions of a Community-Based Accompaniment Intervention for Adolescents Transitioning to Adult HIV Care in Urban Peru: A Qualitative Analysis. medRxiv. Published online January 1, 2022:2022.04.11.22273102. doi: 10.1101/2022.04.11.22273102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sayegh CS, Wood SM, Belzer M, Dowshen NL. Comparing Different Measures of Retention in Care Among a Cohort of Adolescents and Young Adults Living with Behaviorally-Acquired HIV. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(1):304–310. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02568-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.