Abstract

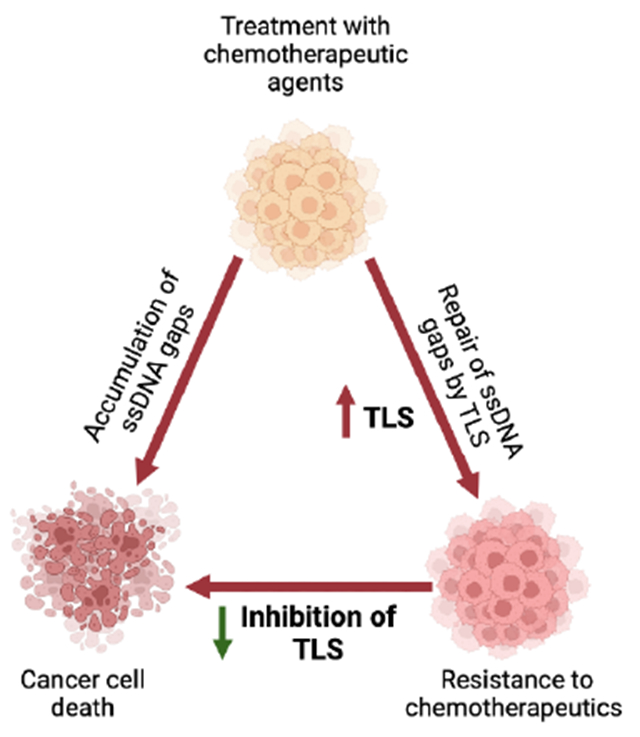

Translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) is a DNA damage tolerance pathway utilized by cells to overcome lesions encountered throughout DNA replication. During replication stress, cancer cells show increased dependency on TLS proteins for cellular survival and chemoresistance. TLS proteins have been described to be involved in various DNA repair pathways. One of the major emerging roles of TLS is single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) gap-filling, primarily after the repriming activity of PrimPol upon encountering a lesion. Conversely, suppression of ssDNA gap accumulation by TLS is considered to represent a mechanism for cancer cells to evade the toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents, specifically in BRCA-deficient cells. Thus, TLS inhibition is emerging as a potential treatment regimen for DNA repair-deficient tumors.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

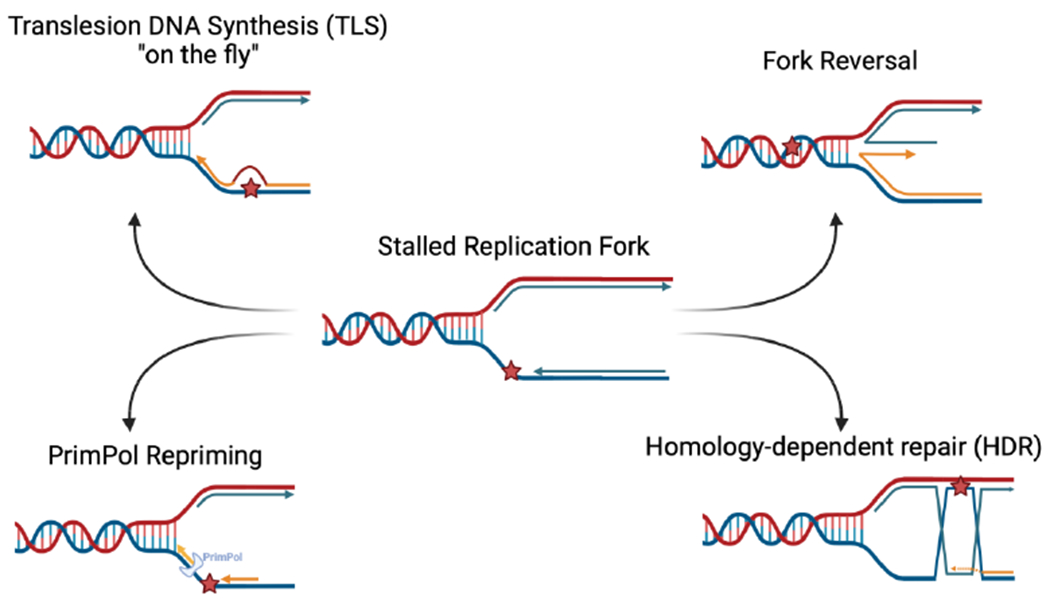

Genomic instability is a cellular vulnerability and a driver of tumorigenesis, therefore considered to be a hallmark of cancer [1]. DNA damage arises from either endogenous or exogenous factors. Endogenous stressors include reactive oxygen species (ROS), abasic sites, as well as imbalanced nucleotide pool, whereas exogenous factors include ultraviolet (UV) radiation, ionizing radiation (IR), and chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin [2]. As a result of these genotoxic stressors, various types of DNA lesions can form, including single-strand DNA (ssDNA) gaps [3, 4], double-strand DNA breaks (DSB) [5, 6], single base lesions and bulky DNA adducts [2, 7, 8]. To deal with such obstacles, the replication fork slows, and in some instants, stalls to allow for the repair and restart of DNA replication. This phenomenon is referred to as “replication stress” and is often implicated in cancer tumorigenesis [7, 9–11]. If these structures are not resolved, the replication fork collapses leading to genomic catastrophe and cell death [12]. Various DNA damage repair (DDR) and DNA damage tolerance (DDT) mechanisms can be utilized by the cell to restart replication and maintain genomic stability [13]. These include homology-dependent repair (HDR), fork reversal, translesion DNA synthesis (TLS), and fork repriming (Fig. 1). Homology-dependent repair is generally error-free and includes BRCA pathway-dependent homologous recombination (HR) repair, as well as template switching (TS), a mechanism that uses the nascent strand of the sister chromatid to bypass the lesion [14, 15]. Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) is a DNA sliding clamp and a major player at replication forks that acts as a processivity factor for replication polymerases [16]. PCNA undergoes various post-translational modifications to initiate DDT pathways [17, 18]. For TS to occur, PCNA undergoes K63-linked polyubiquitination by the E2-ligase complex Mms2/Ubc13 [19]. Replication fork reversal is a version of tS, where the replication fork remodels into a four-way junction by annealing of the two newly synthesized DNA strands [20]. In general, fork reversal repositions the lesion ahead of the fork granting more time for repair while resuming DNA replication and avoiding fork collapse [21]. TLS on the other hand, is an error-prone repair pathway that uses low-fidelity polymerases able to replicate over and beyond the lesion [22]. Lastly, replication fork repriming involves replication restart past the lesion leaving behind ssDNA gaps [23, 24]. In mammalian cells, this repriming is mediated by the human Primase and DNA-directed Polymerase (PrimPol) [25]. Resulting ssDNA gaps are filled by either TS [26, 27] or TLS [28–30]. In BRCA-deficient cells, where HR is not functional, cells use TLS as a compensatory pathway thereby rendering BRCA-deficient cells more reliant on TLS for survival upon exposure to genotoxic agents [31]. To this end, the choice of DDT/DDR mechanism used by the cells is not fully understood. However, it can depend on factors such as the type of damage, availability of factors, and genetic background [32].

Figure 1. DNA Damage tolerance pathways.

As a result of DNA-damaging agents and replication stress, replication forks arrest at fork blocking obstacles. Various repair pathways can be utilized by the cell for survival. Created with BioRender.com.

Here, we will focus on the role of TLS in DNA damage tolerance, specifically discussing the role of TLS proteins in ssDNA gap-filling in BRCA-deficient tumors. Inhibition of TLS proteins causes the accumulation of ssDNA gaps that can eventually be toxic to the cells if kept unrepaired [31, 33]. Recent studies indicate that such a vulnerability can be exploited in BRCA-deficient tumors. Thus, targeting TLS in BRCA-deficient cells is a potential therapeutic approach that can be utilized.

Translesion DNA synthesis (TLS): a DNA damage tolerance pathway

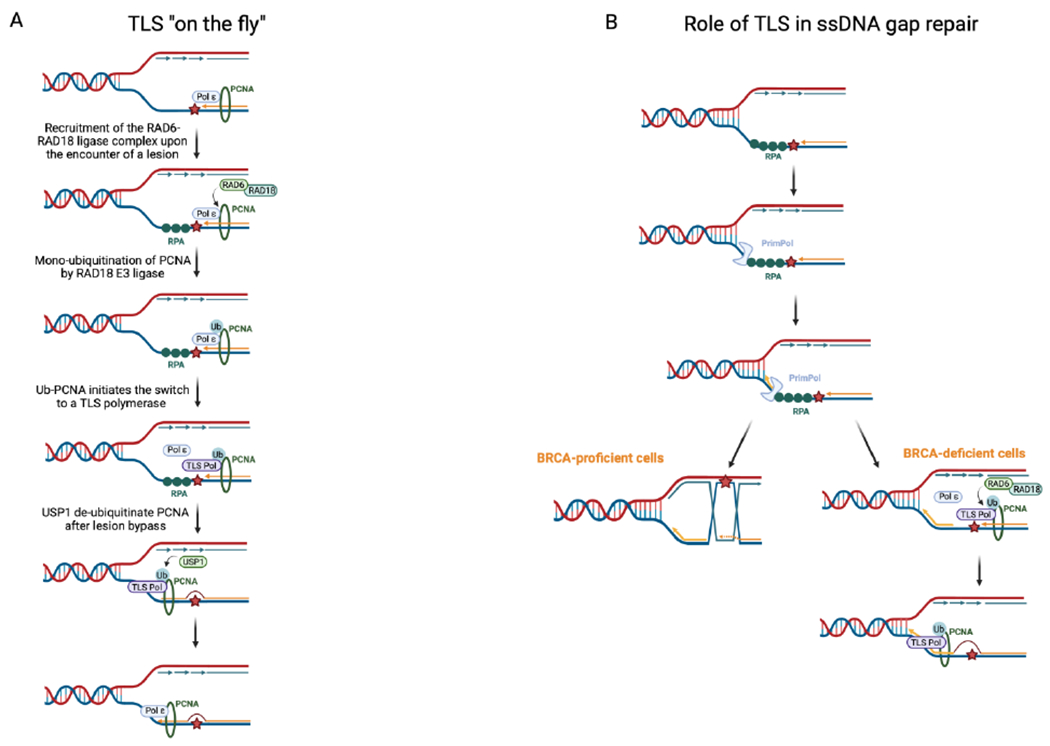

TLS is a conserved DNA damage tolerance pathway that enables the replication machinery to bypass lesions and restart replication. To be able to replicate through obstacles, specialized TLS polymerases are recruited to mediate the replication through and past the lesion. These TLS polymerases belong to several polymerase families and are known to be involved in various biological processes (Table 1). Most TLS polymerases belong to the Y-family of polymerases which have a larger active site and lack proofreading activity, allowing them to incorporate nucleotides across the lesion [34]. Such polymerases include REV1, Polη, Polκ, and Polι [35]. To initiate the switch from a high-fidelity replicative polymerase to a low-fidelity TLS polymerase, PCNA is monoubiquitinated at residue lysine 164 (K164) [36]. This post-translational modification of PCNA is mediated by the RAD6/RAD18 E2-E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [18]. RAD18 is signaled to stalled replication forks by replication protein A (RPA) which coats ssDNA gaps upon the encounter of a lesion [37, 38]. Most TLS polymerases interact with mono-ubiquitinated PCNA through their PCNA interacting peptide box (PIP-box) [39] and ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIM) [40]. This interaction with PCNA is essential for the sequential activity of these polymerases where nucleotides are first inserted across the lesion [41], which is then followed by the extension of the nascent strand by Polκ [42] or by Polς [43]. REV1, on the other hand, is a unique polymerase as it seems to interact with PCNA through its BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domain [44]. REV1 has been described to act as a scaffold for other TLS polymerases including Polζ, Polη, Polκ, and Polι [45]. This repair by TLS is often referred to as TLS ‘on-the-fly’ (Fig. 2k). In this model, PCNA monoubiquitination and polymerase switch occur instantly upon the encounter of a lesion. In addition to its role in lesion bypass, TLS is also involved in ssDNA gap-filling [2, 46] (Fig. 2B). While lesion bypass could occur co-replicationally, it has been reported that ssDNA gaps can be filled post-replicatively in the late S phase or G2 phase [28]. The role of TLS in ssDNA gap-filling will be further discussed later in this review.

Table 1.

List of TLS and other polymerases discussed in this review.

| TLS and other related polymerases | Family/ Features | Function | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymerase eta (Polη) | Y family Low fidelity and processivity Lacks 3’-5’ proofreading activity |

Replicates over cyclobutene pyrimidine dimers (CPD) and platinum-induced intrastrand crosslinks such as cisplatin adducts. Mutations in Polη leads to higher sensitivity to UV radiation and risk of skin cancer. Overexpression of Polη causes chemoresistance in cancers such as ovarian cancers. |

[113–115] |

| Polymerase kappa (Polκ) | Y family Low fidelity and processivity Acts as an extender after bypassing the lesion. Lacks 3’-5’ proofreading activity |

Bypasses bulky lesions such as BPDE and 8-oxoguanine caused by benzo[a]pyrene, as well as N3-methyl-adenine. | [42, 116, 117] |

| Polymerase iota (Polι) | Y family; unusual member Has the lowest fidelity Uses Hoogsteen base pairing during DNA synthesis |

Can bypass 8-oxoguanine with the highest fidelity compared to other TLS polymerases. Unable to bypass cisplatin-induced intrastrand crosslinks and CPD. |

[118–120] |

| Polymerase zeta (Polζ) | B family Made up of two subunits: Rev3 (the catalytic subunit) and Rev7 (stimulates the activity of Rev3) Known to interact with Rev1 Lacks exonuclease proofreading activity |

Mainly responsible for extending the mismatch primer, but not for replicating over a lesion. Some studies indicate that is it capable of bypassing (6-4) photoproducts |

[121–124] |

| REV1 | Y family | Inserts deoxycytidine (dC) across abasic sites. Is able to bypass bulky lesions by acting as a scaffold for other TLS polymerases. The small molecule JH-RE-06 inhibits the interaction between REV1 and Polζ. |

[99, 125] |

| Primase and DNA directed polymerase (PrimPol) | Archaeo-eukaryotic primases (AEP) | Responsible for catalyzing DNA primers specifically after obstacles to restart replication. | [23] |

| Polymerase theta (Polθ) | A family Lacks proofreading activity |

Involved in TLS to bypass UV-induced lesions and abasic sites. Also functions in TMEJ (polymerase theta-mediated end joining) to repair DNA breaks. |

[126–129] |

Figure 2. Roles of TLS in DNA repair.

A. Mechanism of lesion bypass by TLS, also referred to as “TLS on the Fly”. Upon the encounter of a lesion, PCNA is ubiquitinated by the RAD6-RAD18 ligase complex, initiating the switch to a TLS polymerase. USP1 acts as a major regulator of TLS after lesion bypass. B. Repriming after a lesion by PrimPol leaves behind ssDNA gaps that are either filled by homology-dependent repair or by TLS. BRCA status may dictate the choice of gap-filling mechanism. Created with BioRender.com.

Being a mutagenic tolerance pathway, TLS is tightly regulated. Several regulatory mechanisms operate through the de-ubiquitination of PCNA by various deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). One of the major regulators of mono-ubiquitinated PCNA is ubiquitin-specific peptidase 1 (USP1) [47]. USP1 deubiquitinates modified PCNA at residue K164 in vivo and in vitro [47]. Exposure to UV irradiation causes the degradation and autocleavage of USP1 leading to higher levels of ubiquitinated PCNA and TLS activity [47]. Thus, the loss of USP1 was shown to increase mutation frequency after UV exposure [47]. Interestingly, other studies have shown that the de-ubiquitination of PCNA after oxidative stress is independent of USP1 and occurs outside of S-phase [48]. As such, monoubiquitination of PCNA after H2O2 exposure is mainly regulated by USP7 rather than USP1 [49]. USP7 mainly acts during interphase, while USP1 is critical throughout the S-phase [49]. Other studies show that USP10 is also involved in the de-ubiquitination of PCNA after its ISG15 modification (ISGylation) [50].

In addition to de-ubiquitination by de-ubiquitinating enzymes, recent studies have shown that the maintenance of PCNA ubiquitination can be influenced by multiple other factors, which therefore can act as TLS regulators. One of these factors is the E3 ubiquitin ligase RFWD3, which is needed for the bypass across DNA-protein crosslinks (DPCs) by ubiquitinating PCNA and modulating TLS [51]. Specifically, Gallina et. al show that RFWD3 promotes the ubiquitination of PCNA and RPA at ssDNA, thus enabling ssDNA gap-filling [51]. Moreover, our laboratory previously identified Poly-ADP-Ribose Polymerase 10 (PARP10) as another regulator of TLS [52]. We showed that PARP10 interacts with PCNA through its PIP-box and UIM domains, and that the depletion of PARP10 causes a decrease in the ubiquitination of PCNA and in translesion synthesis rates [52]. Subsequently, we showed that PARP10 overexpression helps alleviate replication stress from HU and promotes tumor formation in the mouse xenograft model [53]. In addition, a genome-wide CRISPR knockout screen performed in our laboratory showed that PARP10-overexpressing cells rely on Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, a regulator of DNA damage repair, for survival [54].

Mechanisms of genome stability orchestrated by TLS

TLS in fork reversal and degradation

Fork reversal is a conserved DNA stress response that results in a four-way junction by the annealing of the two newly synthesized strands [20, 55]. Reversal is dependent on several DNA translocases including SMARCAL1 [56], HLTF [57], and ZRANB3 [58, 59] as well as DNA helicases including RECQL5, WRN, and BLM. Ultimately, repositioning the lesion ahead of the fork to double-stranded DNA allows for excision repair and prevents fork collapse due to prolonged stalled replication fork [55]. In addition, reversal avoids continued replication across the lesion preventing the accumulation of ssDNA breaks that can eventually lead to DSB [55]. Fork reversal can in some circumstances be detrimental to the cells. Reversed forks are more prone to nucleolytic degradation and misalignment of the parental and newly synthesized strands during strand exchange. Such vulnerabilities render cells more susceptible to genetic instability and diseases including cancer. Earlier studies have shown the central role of BRCA proteins in protecting reversed forks from nucleolytic degradation by MRE11 [60, 61]. As such, BRCA2-deficient cells are more susceptible to MRE11 degradation and genomic instability [60, 61]. The ability to suppress fork degradation correlates with resistance to genotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs including cisplatin and PARP inhibitors such as olaparib [61–63]. While roles of TLS proteins in replication fork reversal have been identified, the exact mechanisms of their involvement are not yet fully understood. Polι was identified to form a complex with p53 that is required for fork reversal by ZRANB3 and HLTF to bypass DNA damage [64]. In addition, Tonzi et al. showed that Polκ is required for fork protection from nucleolytic degradation by MRE11 after SMARCAL1 remodeling upon treatment with a high dose of 2mM hydroxyurea (HU) [65]. Furthermore, BRCA2-deficient PEO1 ovarian cancer cells with increased TLS activity showed resistance to cisplatin [33]. Therefore, cells with enhanced TLS activity seem to prevent fork reversal and degradation [33].

TLS in fork repriming

Repriming is a stress response mechanism utilized to deal with perturbations during DNA replication. DNA priming in human cells is mediated by a family of enzymes called Primases, which synthesize short RNA oligonucleotides that act as primers for DNA polymerases. Two DNA primases have been identified in eukaryotes: The Polα primase complex and PrimPol [23–25]. The Polα-primase complex is essential for DNA replication by synthesizing and initial extension of RNA primers at replication fork origins on the leading strand and for Okazaki fragments synthesis on the lagging strand [66]. PrimPol is a recently characterized member of the AEP (Archaeo-Eukaryotic Primases) family, containing the conserved AEP domain that binds double and single-stranded DNA, and the UL52-like zinc finger domain that only binds ssDNA [67, 68]. Along with its repriming activity, PrimPol is a highly error-prone polymerase that lacks exonuclease activity, similar to TLS polymerases. Studies have shown that PrimPol is indeed recruited to stalled replication forks after exposure to UV-radiation [24]. As such, PrimPol is able to bypass 8-oxo-guanine lesions, abasic sites, and CPD [23, 24]. On the other hand, as a result of the recruitment of PrimPol to stalled replication forks and its primase activity restarting the fork past the lesion, ssDNA gaps form on the template DNA strand that are repaired post-replicatively. Such ssDNA gaps have been visualized using electron microscopy and two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis [69]. The repair of ssDNA gaps is crucial for genomic stability as these stretches are more susceptible to nucleolytic processing that eventually can lead to DSB. In addition, studies from our laboratory have shown that, on the lagging strand, defective Okazaki fragment maturation impedes nucleosome assembly, leaving BRCA-deficient cells more sensitive to genotoxic agents [70, 71]. These findings suggest that Polα-mediated repriming is a mechanism of genomic instability under replication stress conditions.

TLS in ssDNA gap filling

Nascent strand ssDNA gaps can form in response to treatment with multiple DNA damaging agents, including UV [24], BPDE [72], MMC [73], PARP1 inhibitors [10], cisplatin [3]. In general, the mechanism of ssDNA gap formation in response to these genotoxic agents involves fork arrest at the site of the lesion, followed by repriming of the fork downstream the lesion through the activity of the PRIMPOL. To fill the gap left behind the fork, TLS polymerases can bypass the lesion and subsequently extend beyond the lesion to fill up the gap (Fig. 2B). Different TLS polymerases have been identified to participate in the repair of ssDNA gaps. Nayak et al. showed an increase in the percentage of ssDNA present in cells under HU conditions upon REV1 inhibition [33]. Furthermore, RAD18, PCNA monoubiquitination, and the REV1-Polζ polymerases are also essential for gap-filling, specifically during the late S and G2 phase [28]. Using a single-molecule DNA fiber technique to investigate PRR tract density, Tirman et al. showed that the knockdown of RAD18 and REV1 impaired gap-filling in PrimPol-overexpressing cells upon cisplatin treatment [28]. Similarly, PCNA K164R mutant cells with transient PrimPol-overexpression demonstrated a lack of gap-filling activity, indicating the need for the monoubiquitination of PCNA ssDNA repair [28]. In addition, depletion of Polι is also implicated in an increase in PrimPol-dependent repriming leading to the accumulation of ssDNA gaps and genomic instability [74]. On the other hand, its expression causes checkpoint activation such as Chk1 leading to the recruitment of RPA onto ssDNA and consequently ZRANB3-mediated fork reversal [74].

Interestingly, gap-filling activity by TLS polymerases is affected by the cell cycle. Studies done in budding yeast have shown that TLS can mainly occur in the G2/M phase [75]. This was supported by evidence that TLS counteracts and fills ssDNA gaps behind the fork, without any significant effect on fork progression [69]. In addition, restricting the expression of Polη and REV3 to the G2/M phase did not affect cell survival even after exposure to DNA-damaging agents [75]. G2/M-restricted cells were proficient in spontaneous and UV-induced mutagenesis [75], indicating that Polη-mediated gap-filling is functional after the S phase. In line with this, in budding yeast REV1 levels were reported to increase rapidly in the late S phase with its highest expression being in G2 and M [76]. In human cells. TLS was also found to take place in G2, with higher overall mutation frequency than in S-phase, albeit the expression of REV1 was not found to fluctuate during the cell cycle [77]. In contrast to budding yeast and human cells, in fission yeast the expression of REV1 peaks during G1, which was linked to its role in the assembly of TLS polymerase complexes, which are thus primed for action during S-phase [78].

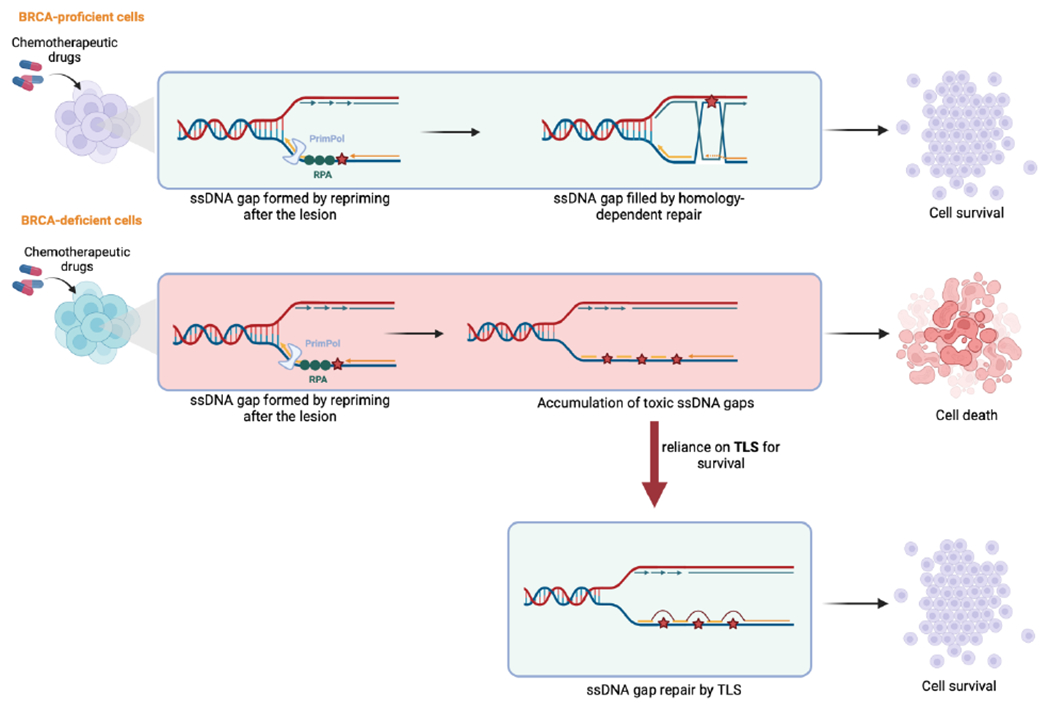

Functional relevance of TLS-mediated ssDNA gap filling in BRCA-deficient tumors

Along with their major role in protecting reversed forks, BRCA proteins are essential for the repair of ssDNA gaps [79–81]. Recent studies have focused on understanding the role of ssDNA gap accumulation in BRCA-deficient cells [28, 31, 33] (Fig. 2B). ssDNA gaps generated by PrimPol-mediated repriming can be repaired by homology-dependent repair involving the sister chromatid [82]. In addition, BRCA proteins inhibit MRE11 nucleolytic activity in the S and G2 phase [28] and suppress the repriming activity of PrimPol by interacting with MCM10 [83]. As the accumulation of ssDNA gaps is toxic, BRCA-deficient cells, due to their inability to initiate repair through TS, become more reliant on TLS for the repair of ssDNA gaps and survival upon exposure to genotoxic agents [28, 31, 32]. Recent studies showed that depletion of RAD18 and REV1 is synthetic lethal with BRCA1 and BRCA2 [31]. Importantly, this lethal interaction is dependent on PrimPol repriming activity [31]. Therefore, inhibition of REV1-Polζ sensitizes BRCA1-deficient cells to olaparib and cisplatin [31] (Fig. 3). In addition, loss of the polymerase Polθ, which has both TLS and end joining (known as TMEJ, for Theta-Mediated End Joining) activities in BRCA1-deficient cells results in synthetic lethality due to the accumulation of ssDNA gaps which ultimately causes a delay in the progression through the S phase [84, 85] (Fig. 3). This was also shown using a Polθ small-molecule inhibitor that targets its polymerase domain, potentially indicating that Polθ TLS activity is required for ssDNA gap filling [84]. In addition, Polθ is critical for preventing the cleavage of ssDNA gaps by the MRE11-NBS1-CtIP complex endonuclease activity and averts fork collapse [85]. Due to the importance of Polθ in cancer development, several inhibitors have been developed that target both its polymerase and helicase domain [86].

Figure 3. Repair of ssDNA gaps drives chemoresistance in BRCA-deficient cells.

BRCA-proficient cells are able to survive the toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents by utilizing homology-dependent repair. However, BRCA-deficient cells are sensitive to such therapies through the accumulation of ssDNA gaps. These can cells develop resistance by relying on TLS for gap repair and survival. Created with BioRender.com.

TLS as a target in cancer treatment

TLS inhibition in combination with cross-linking agents

Various studies have explored the role of TLS proteins in bypassing cross-links formed by platinum-based drugs and thereby contributing to resistance. Increased levels of Polη has been associated with resistance to cisplatin in NSCLC cell lines, making the expression levels of Polη a biomarker for the efficacy of cisplatin [87]. Interestingly, the expression of Polθ increases upon the treatment of cisplatin-resistant A549/DR lung cancer cells with cisplatin [88]. Co-depletion of Polθ and BRCA2 significantly increases the sensitivity of these cells to cisplatin, implying a synthetic lethal relationship between Polθ and HR [88]. Whether this synthetic lethality is due to the TLS or TMEJ activities of Polθ is unclear. However, the increase in 53BP1 and RAD51 foci upon knockdown of Polθ may indicate that the TMEJ activity affects sensitivity to cisplatin [88]. Moreover, replication stress caused by Cyclin E overexpression, oncogenic RAS expression, or inhibition of ATR or WEE1 results in accumulation of ssDNA gaps and leads to increased TLS activity to fill these gaps. Thus, WEE1 or ATR inhibition is toxic to TLS-deficient cells [33, 89].

TLS inhibition in PARP1 inhibitor resistance

PARP1 inhibitors (PARPi) have been used in the clinic for the treatment of BRCA-deficient tumors. PARPi work by inactivating its PARylation activity, as well as by trapping PARP1 on damaged DNA generating a protein-DNA complex that blocks DNA replication [90–93]. The synthetic lethal interaction between PARP1 and BRCA proteins was first described by the finding that PARP1 inhibition sensitizes BRCA-deficient cells [5, 6]. Due to the lack of DNA break repair, trapping PARP1 on damaged DNA causes DNA breaks that cannot be repaired in BRCA-deficient cells, ultimately causing fork collapse [5, 6]. In addition, BRCA proteins are essential for replication fork protection by inhibiting nucleolytic degradation of nascent DNA at stalled forks [60, 94]. Thus, loss of BRCA protein causes excessive nucleolytic degradation and eventually fork collapse [30, 60, 94]. However, resistance to PARPi develops due to the restoration of HR and replication fork stability [62, 95, 96]. Recently, new evidence has indicated that the cisplatin chemosensitivity of BRCA-deficient cells may also be attributed to the formation of ssDNA gaps during replication, somewhat challenging the fundamental idea of the DSB toxicity [79, 81]. As such, toxicity to cisplatin-induced cross-links in BRCA-deficient cells is thought to be due to unrestrained replication under genotoxic conditions [81]. BRCA-proficient cells with intact fork protection and HR remain sensitive to chemotherapy unless ssDNA gap accumulation is suppressed [79, 81] (Fig. 3). On the other hand, BRCA2 separation-of-functions mutants which are proficient for HR but defective in fork protection and ssDNA gap suppression show reduced chemosensitivity compared to BRCA2 mutants defective in all three activities, suggesting that BRCA2 promotes therapy resistance primarily through HR [97, 98]. Overall, these findings suggest that ssDNA gaps may be, at least in part, drivers of chemosensitivity in BRCA-deficient cells. Thus, inhibiting TLS could potentially re-sensitize BRCA-deficient cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Indeed, a potent TLS inhibitor has been recently developed, which blocks the REV1-REV7 interaction and thus impairs Polζ recruitment. In both cell lines and mouse xenografts, treatment with this compound, termed JH-RE-06, causes cisplatin sensitivity [99]. Moreover, this compound hyper-sensitized BRCA1-deficient cells to cisplatin [28, 31].

Expression of TLS proteins in cancer cells

The expression of TLS factors varies in different types of cancers. RAD6B, a major E2 ligase and regulator of TLS, was found to be overexpressed in breast cancers promoting cellular transformation and chemoresistance to cisplatin and adriamycin [100, 101]. As such inhibition of RAD6 with its small molecule inhibitor SMI#9 enhances sensitivity to cisplatin in both BRCA1-wildtype and mutated triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells [102]. Moreover, RAD18 has also been reported to be a possible prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer tissues (CRC) [103]. Similarly, transgenic mice with REV1 overexpression show increased intestinal carcinoma after treatment with N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) carcinogen [104]. Interestingly, these REV1 overexpressing mice did not develop spontaneous tumors similar to wild-type mice [104]. Furthermore, data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) show upregulation of Polθ mRNA levels in lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) cells. Polθ overexpression is associated with increased somatic mutation load and resistance to etoposide-induced DSBs, however it is unclear if this is due to its TLS or TMEJ activities [105]. Overexpression of Polκ has also been implicated in tumorigenesis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [106], as well as resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide in glioblastoma cells [107]. Indeed, various TLS polymerases are implicated in different types of cancers and contribute to resistance to chemotherapeutics.

Synthetic lethality between USP1 and the BRCA pathway

Due to the central role of USP1 in regulating TLS by de-ubiquitinating PCNA, inhibiting USP1 became of great interest. Using TCGA breast cancer consortium data, Lim et al. showed that USP1 is overexpressed in BRCA1-deficient cells [108]. They further showed that loss of USP1 results in synthetic lethality in BRCA1-deficient cells due to persistent monoubiquitination of PCNA, leading to extensive replication fork degradation [108]. In addition, a recent CRISPR-Cas9 screen also identified USP1 as being synthetic lethal with the loss of BRCA1/2 [109]. Inhibition of USP1 using the small molecules I-138 and ML323 reduced the viability of BRCA1-mutated breast and ovarian cancer cell lines [109]. Ultimately, inhibition of USP1 leads to high levels of mono and poly-ubiquitinated PCNA [109]. Moreover, combination treatment with USP1 and PARP inhibitors synergizes in BRCA1/2 mutant tumors [109]. Mechanistically, Coleman, et al. showed that the autocleavage activity of USP1 is critical for maintaining replication fork integrity and elongation [110]. By inhibiting the autocleavage activity, USP1 gets trapped on the nascent DNA leading to an increase in replication stress and DNA damage [110]. Such studies suggest USP1 is a clinical target for the treatment of BRCA1/2-deficient tumors and possibly in combination with PARP inhibitors. This highlights the potential for USP1 inhibition as monotherapy or combination therapy with platinum drugs in BRCA-deficient patients.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The role of TLS in cancer development has been investigated in several contexts, including its inherently mutagenic outcomes during lesion bypass, its function in fork restart and reversal, and most recently its role in gap-suppression in BRCA-deficient cells and chemoresistance. Here, we first review the canonical mechanism by which TLS is initiated and regulated by various major enzymes upon DNA perturbations. We highlight the dependence of cancer cells on TLS proteins for damage tolerance and survival. We discuss the essential role of TLS in ssDNA gap-filling and its impact on chemoresistance. Various studies in recent years have indicated the importance of ssDNA gaps in chemosensitivity against genotoxic agents, particularly in BRCA-deficient cells. To survive, cancer cells rely on TLS to suppress ssDNA gaps and therefore develop chemoresistance to conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Thus, solely inhibiting TLS polymerases or in combination with platinum drugs or PARPi could provide a potential solution to chemoresistance in BRCA-deficient tumors. The dependency of cancer cells on TLS proteins provides evidence for further development of TLS inhibitors and exploring new treatment regimens for BRCA-deficient patients involving combination therapy with TLS inhibitors.

Although significant progress has been made in understanding the role of TLS in genomic stability, ambiguities and gaps in our knowledge remain to be answered. Many TLS factors have been implicated in DDT pathways, however, whether these polymerases have unique or redundant roles in genomic stability, lesion bypass, and gap-filling requires further investigation. Indeed, multiple TLS proteins have been implicated in PrimPol-mediated gap-filling including RAD18, REV1-Polξ [31], and Polι [74]. While RAD18 and the REV1-Polξ complex promote genomic stability by their gap-filling activity, Polι slows the replication fork and prevents the progression through the S phase by suppressing PrimPol-mediated repriming. Polι was found to counteract the possible genomic instability prompted by PrimPol activity in a different manner than gap-filling [74]. Depletion of Polι causes a decrease in the phosphorylation of checkpoint proteins such as Chk1, KAP1, and RPA leading to increased replication and accumulation of PrimPol-mediated ssDNA stretches. This activity of Polι was described to be “TLS-independent” requiring its interaction with PCNA and regulation of replication speed, as well as cell cycle progression, but not its polymerase function [74]. This reflects the diverse activities and roles of TLS polymerases in genomic stability and in gap-filling which is worth investigating from a broader perspective.

Furthermore, factors that determine the choice of gap-filling mechanism, whether through homology-dependent repair or TLS, remain elusive. Although factors such as BRCA status, type of obstacle, and cell cycle are indicative of the choice of repair, further characterization of each repair pathway is still required. Recently, Garrido et al. showed that efficient histone deposition and recycling at the parental strand is required for ssDNA gap-filling by HR to occur upon treatment with the alkylating agent methyl-methane sulfonate (MMS) [111]. TLS is observed to be an alternative mechanism for ssDNA repair in cells with defective histone recycling and HR [111]. In addition, a study in yeast showed that the Rad55-Rad57 complex is needed for RAD51 filament assembly at UV-induced ssDNA gaps, which inhibits the recruitment of TLS polymerases onto the gap [112]. Therefore, in Rad55-Rad57 deficient cells where the Rad52 filaments are unstable, TLS polymerases are loaded to initiate repair by TLS [112]. Expanding our understanding of the interplay between both repair pathways will allow for the characterization of how TLS polymerases influence cancer development and resistance to chemotherapeutics. This will give more insight into targeted therapies and the potential resistance to TLS inhibitors in cancers.

Research Highlights.

Translesion synthesis (TLS) is a DNA damage tolerance (DDT) and mutagenic repair pathway used to bypass DNA lesions.

Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) gaps are potential determinants of the sensitivity of cancer cells to cisplatin and PARP1 inhibitors. Such gaps are repaired by either homology-dependent repair or TLS.

In BRCA-deficient cells, TLS is used to repair ssDNA gaps and acts as a chemoresistance mechanism. Inhibition of TLS in these cells is a possible treatment regimen that can be in combination with chemotherapeutic agents to cause the accumulation of toxic ssDNA gaps.

Acknowledgments

G.L.M. is supported by NIH R01ES026184 and R01GM134681. C.M.N. is supported by NIH R01CA244417. Schematic figures were created with Biorender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chatterjee N, Walker GC. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2017;58:235–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Quinet A, Tirman S, Jackson J, šviković S, Lemaçon D, Carvajal-Maldonado D, et al. PRIMPOL-Mediated Adaptive Response Suppresses Replication Fork Reversal in BRCA-Deficient Cells. Mol Cell. 2020;77:461–74.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vaitsiankova A, Burdova K, Sobol M, Gautam A, Benada O, Hanzlikova H, et al. PARP inhibition impedes the maturation of nascent DNA strands during DNA replication. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2022;29:329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cybulla E, Vindigni A. Leveraging the replication stress response to optimize cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:6–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411:366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gaillard H, García-Muse T, Aguilera A. Replication stress and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:276–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Genois MM, Gagné JP, Yasuhara T, Jackson J, Saxena S, Langelier MF, et al. CARM1 regulates replication fork speed and stress response by stimulating PARP1. Mol Cell. 2021;81:784–800.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maya-Mendoza A, Moudry P, Merchut-Maya JM, Lee M, Strauss R, Bartek J. High speed of fork progression induces DNA replication stress and genomic instability. Nature. 2018;559:279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fugger K, Bajrami I, Silva Dos Santos M, Young SJ, Kunzelmann S, Kelly G, et al. Targeting the nucleotide salvage factor DNPH1 sensitizes. Science. 2021;372:156–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sale JE. Competition, collaboration and coordination--determining how cells bypass DNA damage. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1633–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Adar S, Izhar L, Hendel A, Geacintov N, Livneh Z. Repair of gaps opposite lesions by homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5737–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wright WD, Shah SS, Heyer WD. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:10524–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Choe KN, Moldovan GL. Forging Ahead through Darkness: PCNA, Still the Principal Conductor at the Replication Fork. Mol Cell. 2017;65:380–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tsutakawa SE, Yan C, Xu X, Weinacht CP, Freudenthal BD, Yang K, et al. Structurally distinct ubiquitin- and sumo-modified PCNA: implications for their distinct roles in the DNA damage response. Structure. 2015;23:724–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chiu RK, Brun J, Ramaekers C, Theys J, Weng L, Lambin P, et al. Lysine 63-polyubiquitination guards against translesion synthesis-induced mutations. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Neelsen KJ, Lopes M. Replication fork reversal in eukaryotes: from dead end to dynamic response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:207–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Berti M, Cortez D, Lopes M. The plasticity of DNA replication forks in response to clinically relevant genotoxic stress. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:633–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sale JE. Translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].García-Gómez S, Reyes A, Martínez-Jiménez MI, Chocrón ES, Mourón S, Terrados G, et al. PrimPol, an archaic primase/polymerase operating in human cells. Mol Cell. 2013;52:541–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mourón S, Rodriguez-Acebes S, Martínez-Jiménez MI, García-Gómez S, Chocrón S, Blanco L, et al. Repriming of DNA synthesis at stalled replication forks by human PrimPol. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bianchi J, Rudd SG, Jozwiakowski SK, Bailey LJ, Soura V, Taylor E, et al. PrimPol bypasses UV photoproducts during eukaryotic chromosomal DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2013;52:566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fumasoni M, Zwicky K, Vanoli F, Lopes M, Branzei D. Error-free DNA damage tolerance and sister chromatid proximity during DNA replication rely on the Polα/Primase/Ctf4 Complex. Mol Cell. 2015;57:812–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rossi SE, Ajazi A, Carotenuto W, Foiani M, Giannattasio M. Rad53-Mediated Regulation of Rrm3 and Pif1 DNA Helicases Contributes to Prevention of Aberrant Fork Transitions under Replication Stress. Cell Rep. 2015;13:80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tirman S, Quinet A, Wood M, Meroni A, Cybulla E, Jackson J, et al. Temporally distinct post-replicative repair mechanisms fill PRIMPOL-dependent ssDNA gaps in human cells. Mol Cell. 2021;81:4026–40.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gallo D, Kim T, Szakal B, Saayman X, Narula A, Park Y, et al. Rad5 Recruits Error-Prone DNA Polymerases for Mutagenic Repair of ssDNA Gaps on Undamaged Templates. Mol Cell. 2019;73:900–14.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hashimoto Y, Ray Chaudhuri A, Lopes M, Costanzo V. Rad51 protects nascent DNA from Mre11-dependent degradation and promotes continuous DNA synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1305–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Taglialatela A, Leuzzi G, Sannino V, Cuella-Martin R, Huang JW, Wu-Baer F, et al. REV1-Polζ maintains the viability of homologous recombination-deficient cancer cells through mutagenic repair of PRIMPOL-dependent ssDNA gaps. Mol Cell. 2021;81:4008–25.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Quinet A, Tirman S, Cybulla E, Meroni A, Vindigni A. To skip or not to skip: choosing repriming to tolerate DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2021;81:649–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nayak S, Calvo JA, Cong K, Peng M, Berthiaume E, Jackson J, et al. Inhibition of the translesion synthesis polymerase REV1 exploits replication gaps as a cancer vulnerability. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:317–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhao L, Washington MT. Translesion Synthesis: Insights into the Selection and Switching of DNA Polymerases. Genes (Basel). 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bienko M, Green CM, Crosetto N, Rudolf F, Zapart G, Coull B, et al. Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science. 2005;310:1821–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Davies AA, Huttner D, Daigaku Y, Chen S, Ulrich HD. Activation of ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is mediated by replication protein a. Mol Cell. 2008;29:625–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Niimi A, Brown S, Sabbioneda S, Kannouche PL, Scott A, Yasui A, et al. Regulation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen ubiquitination in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16125–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Masuda Y, Kanao R, Kaji K, Ohmori H, Hanaoka F, Masutani C. Different types of interaction between PCNA and PIP boxes contribute to distinct cellular functions of Y-family DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7898–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Guo C, Tang TS, Bienko M, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Sonoda E, et al. Ubiquitin-binding motifs in REV1 protein are required for its role in the tolerance of DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kannouche PL, Wing J, Lehmann AR. Interaction of human DNA polymerase eta with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2004;14:491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Haracska L, Prakash L, Prakash S. Role of human DNA polymerase kappa as an extender in translesion synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16000–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Johnson RE, Washington MT, Haracska L, Prakash S, Prakash L. Eukaryotic polymerases iota and zeta act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions. Nature. 2000;406:1015–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Guo C, Sonoda E, Tang TS, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Takeda S, et al. REV1 protein interacts with PCNA: significance of the REV1 BRCT domain in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell. 2006;23:265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dash RC, Hadden K. Protein-Protein Interactions in Translesion Synthesis. Molecules. 2021;26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Edmunds CE, Simpson LJ, Sale JE. PCNA ubiquitination and REV1 define temporally distinct mechanisms for controlling translesion synthesis in the avian cell line DT40. Mol Cell. 2008;30:519–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Huang TT, Nijman SM, Mirchandani KD, Galardy PJ, Cohn MA, Haas W, et al. Regulation of monoubiquitinated PCNA by DUB autocleavage. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zlatanou A, Despras E, Braz-Petta T, Boubakour-Azzouz I, Pouvelle C, Stewart GS, et al. The hMsh2-hMsh6 complex acts in concert with monoubiquitinated PCNA and Pol η in response to oxidative DNA damage in human cells. Mol Cell. 2011;43:649–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kashiwaba S, Kanao R, Masuda Y, Kusumoto-Matsuo R, Hanaoka F, Masutani C. USP7 Is a Suppressor of PCNA Ubiquitination and Oxidative-Stress-Induced Mutagenesis in Human Cells. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2072–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Park JM, Yang SW, Yu KR, Ka SH, Lee SW, Seol JH, et al. Modification of PCNA by ISG15 plays a crucial role in termination of error-prone translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2014;54:626–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gallina I, Hendriks IA, Hoffmann S, Larsen NB, Johansen J, Colding-Christensen CS, et al. The ubiquitin ligase RFWD3 is required for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2021;81:442–58.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nicolae CM, Aho ER, Vlahos AH, Choe KN, De S, Karras GI, et al. The ADP-ribosyltransferase PARP10/ARTD10 interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and is required for DNA damage tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:13627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Schleicher EM, Galvan AM, Imamura-Kawasawa Y, Moldovan GL, Nicolae CM. PARP10 promotes cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis by alleviating replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:8908–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Khatib JB, Schleicher EM, Jackson LM, Dhoonmoon A, Moldovan GL, Nicolae CM. Complementary CRISPR genome-wide genetic screens in PARP10-knockout and overexpressing cells identify synthetic interactions for PARP10-mediated cellular survival. Oncotarget. 2022;13:1078–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ray Chaudhuri A, Hashimoto Y, Herrador R, Neelsen KJ, Fachinetti D, Bermejo R, et al. Topoisomerase I poisoning results in PARP-mediated replication fork reversal. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bétous R, Mason AC, Rambo RP, Bansbach CE, Badu-Nkansah A, Sirbu BM, et al. SMARCAL1 catalyzes fork regression and Holliday junction migration to maintain genome stability during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 2012;26:151–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Blastyák A, Hajdú I, Unk I, Haracska L. Role of double-stranded DNA translocase activity of human HLTF in replication of damaged DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:684–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Moore CE, Yalcindag SE, Czeladko H, Ravindranathan R, Wijesekara Hanthi Y, Levy JC, et al. RFWD3 promotes ZRANB3 recruitment to regulate the remodeling of stalled replication forks. J Cell Biol. 2023;222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Vujanovic M, Krietsch J, Raso MC, Terraneo N, Zellweger R, Schmid JA, et al. Replication Fork Slowing and Reversal upon DNA Damage Require PCNA Polyubiquitination and ZRANB3 DNA Translocase Activity. Mol Cell. 2017;67:882–90.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schlacher K, Christ N, Siaud N, Egashira A, Wu H, Jasin M. Double-strand break repair-independent role for BRCA2 in blocking stalled replication fork degradation by MRE11. Cell. 2011;145:529–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Taglialatela A, Alvarez S, Leuzzi G, Sannino V, Ranjha L, Huang JW, et al. Restoration of Replication Fork Stability in BRCA1- and BRCA2-Deficient Cells by Inactivation of SNF2-Family Fork Remodelers. Mol Cell. 2017;68:414–30.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ray Chaudhuri A, Callen E, Ding X, Gogola E, Duarte AA, Lee JE, et al. Replication fork stability confers chemoresistance in BRCA-deficient cells. Nature. 2016;535:382–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Thakar T, Moldovan GL. The emerging determinants of replication fork stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:7224–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hampp S, Kiessling T, Buechle K, Mansilla SF, Thomale J, Rall M, et al. DNA damage tolerance pathway involving DNA polymerase ι and the tumor suppressor p53 regulates DNA replication fork progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E4311–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Tonzi P, Yin Y, Lee CWT, Rothenberg E, Huang TT. Translesion polymerase kappa-dependent DNA synthesis underlies replication fork recovery. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Muzi-Falconi M, Giannattasio M, Foiani M, Plevani P. The DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex: multiple functions and interactions. ScientificWorldJournal. 2003;3:21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Keen BA, Jozwiakowski SK, Bailey LJ, Bianchi J, Doherty AJ. Molecular dissection of the domain architecture and catalytic activities of human PrimPol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:5830–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Iyer LM, Koonin EV, Leipe DD, Aravind L. Origin and evolution of the archaeo-eukaryotic primase superfamily and related palm-domain proteins: structural insights and new members. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3875–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lopes M, Foiani M, Sogo JM. Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol Cell. 2006;21:15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Thakar T, Leung W, Nicolae CM, Clements KE, Shen B, Bielinsky AK, et al. Ubiquitinated-PCNA protects replication forks from DNA2-mediated degradation by regulating Okazaki fragment maturation and chromatin assembly. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Thakar T, Dhoonmoon A, Straka J, Schleicher EM, Nicolae CM, Moldovan GL. Lagging strand gap suppression connects BRCA-mediated fork protection to nucleosome assembly through PCNA-dependent CAF-1 recycling. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Piberger AL, Bowry A, Kelly RDW, Walker AK, González-Acosta D, Bailey LJ, et al. PrimPol-dependent single-stranded gap formation mediates homologous recombination at bulky DNA adducts. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bai G, Kermi C, Stoy H, Schiltz CJ, Bacal J, Zaino AM, et al. HLTF Promotes Fork Reversal, Limiting Replication Stress Resistance and Preventing Multiple Mechanisms of Unrestrained DNA Synthesis. Mol Cell. 2020;78:1237–51.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Mansilla SF, Bertolin AP, Venerus Arbilla S, Castaño BA, Jahjah T, Singh JK, et al. Polymerase iota (Pol ι) prevents PrimPol-mediated nascent DNA synthesis and chromosome instability. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eade7997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Karras GI, Jentsch S. The RAD6 DNA damage tolerance pathway operates uncoupled from the replication fork and is functional beyond S phase. Cell. 2010;141:255–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Waters LS, Walker GC. The critical mutagenic translesion DNA polymerase Rev1 is highly expressed during G(2)/M phase rather than S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8971–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Diamant N, Hendel A, Vered I, Carell T, Reissner T, de Wind N, et al. DNA damage bypass operates in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and exhibits differential mutagenicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:170–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Uchiyama M, Terunuma J, Hanaoka F. The Protein Level of Rev1, a TLS Polymerase in Fission Yeast, Is Strictly Regulated during the Cell Cycle and after DNA Damage. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Cong K, Peng M, Kousholt AN, Lee WTC, Lee S, Nayak S, et al. Replication gaps are a key determinant of PARP inhibitor synthetic lethality with BRCA deficiency. Mol Cell. 2021;81:3128–44.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Simoneau A, Xiong R, Zou L. The. Genes Dev 2021;35:1271–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Panzarino NJ, Krais JJ, Cong K, Peng M, Mosqueda M, Nayak SU, et al. Replication Gaps Underlie BRCA Deficiency and Therapy Response. Cancer Res. 2021;81:1388–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Giannattasio M, Zwicky K, Follonier C, Foiani M, Lopes M, Branzei D. Visualization of recombination-mediated damage bypass by template switching. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:884–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kang Z, Fu P, Alcivar AL, Fu H, Redon C, Foo TK, et al. BRCA2 associates with MCM10 to suppress PRIMPOL-mediated repriming and single-stranded gap formation after DNA damage. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Schrempf A, Bernardo S, Arasa Verge EA, Ramirez Otero MA, Wilson J, Kirchhofer D, et al. POLθ processes ssDNA gaps and promotes replication fork progression in BRCA1-deficient cells. Cell Rep. 2022;41:111716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Mann A, Ramirez-Otero MA, De Antoni A, Hanthi YW, Sannino V, Baldi G, et al. POLθ prevents MRE11-NBS1-CtIP-dependent fork breakage in the absence of BRCA2/RAD51 by filling lagging-strand gaps. Mol Cell. 2022;82:4218–31.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Pismataro MC, Astolfi A, Barreca ML, Pacetti M, Schenone S, Bandiera T, et al. Small Molecules Targeting DNA Polymerase Theta (POLθ) as Promising Synthetic Lethal Agents for Precision Cancer Therapy. J Med Chem. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Ceppi P, Novello S, Cambieri A, Longo M, Monica V, Lo lacono M, et al. Polymerase eta mRNA expression predicts survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1039–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Dai CH, Chen P, Li J, Lan T, Chen YC, Qian H, et al. Co-inhibition of pol θ and HR genes efficiently synergize with cisplatin to suppress cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells survival. Oncotarget. 2016;7:65157–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Yang Y, Gao Y, Mutter-Rottmayer L, Zlatanou A, Durando M, Ding W, et al. DNA repair factor RAD18 and DNA polymerase Polκ confer tolerance of oncogenic DNA replication stress. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:3097–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Pommier Y, O’Connor MJ, de Bono J. Laying a trap to kill cancer cells: PARP inhibitors and their mechanisms of action. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:362ps17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Doroshow JH, et al. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5588–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ström CE, Johansson F, Uhlén M, Szigyarto CA, Erixon K, Helleday T. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is not involved in base excision repair but PARP inhibition traps a single-strand intermediate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3166–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Cong K, Cantor SB. Exploiting replication gaps for cancer therapy. Mol Cell. 2022;82:2363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Schlacher K, Wu H, Jasin M. A distinct replication fork protection pathway connects Fanconi anemia tumor suppressors to RAD51-BRCA1/2. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:106–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bunting SF, Callén E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, et al. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 2010;141:243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, Agarwal MK, Higgins J, Friedman C, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. 2008;451:1116–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lim PX, Zaman M, Jasin M. BRCA2 promotes genomic integrity and therapy resistance primarily through its role in homology-directed repair. bioRxiv. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Feng W, Jasin M. BRCA2 suppresses replication stress-induced mitotic and G1 abnormalities through homologous recombination. Nat Commun. 2017;8:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Wojtaszek JL, Chatterjee N, Najeeb J, Ramos A, Lee M, Bian K, et al. A Small Molecule Targeting Mutagenic Translesion Synthesis Improves Chemotherapy. Cell. 2019;178:152–9.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Lyakhovich A, Shekhar MP. RAD6B overexpression confers chemoresistance: RAD6 expression during cell cycle and its redistribution to chromatin during DNA damage-induced response. Oncogene. 2004;23:3097–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Shekhar MP, Lyakhovich A, Visscher DW, Heng H, Kondrat N. Rad6 overexpression induces multinucleation, centrosome amplification, abnormal mitosis, aneuploidy, and transformation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2115–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Haynes B, Gajan A, Nangia-Makker P, Shekhar MP. RAD6B is a major mediator of triple negative breast cancer cisplatin resistance: Regulation of translesion synthesis/Fanconi anemia crosstalk and BRCA1 independence. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866:165561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Li P, He C, Gao A, Yan X, Xia X, Zhou J, et al. RAD18 promotes colorectal cancer metastasis by activating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathway. Oncol Rep. 2020;44:213–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Sasatani M, Xi Y, Kajimura J, Kawamura T, Piao J, Masuda Y, et al. Overexpression of Rev1 promotes the development of carcinogen-induced intestinal adenomas via accumulation of point mutation and suppression of apoptosis proportionally to the Rev1 expression level. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:570–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Shinmura K, Kato H, Kawanishi Y, Yoshimura K, Tsuchiya K, Takahara Y, et al. POLQ Overexpression Is Associated with an Increased Somatic Mutation Load and PLK4 Overexpression in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].O-Wang J, Kawamura K, Tada Y, Ohmori H, Kimura H, Sakiyama S, et al. DNA polymerase kappa, implicated in spontaneous and DNA damage-induced mutagenesis, is overexpressed in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5366–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Peng C, Chen Z, Wang S, Wang HW, Qiu W, Zhao L, et al. The Error-Prone DNA Polymerase κ Promotes Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma through Rad17-Dependent Activation of ATR-Chk1 Signaling. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2340–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Lim KS, Li H, Roberts EA, Gaudiano EF, Clairmont C, Sambel LA, et al. USP1 Is Required for Replication Fork Protection in BRCA1-Deficient Tumors. Mol Cell. 2018;72:925–41.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Simoneau A, Engel JL, Bandi M, Lazarides K, Liu S, Meier SR, et al. Ubiquitinated PCNA Drives USP1 Synthetic Lethality in Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023;22:215–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Coleman KE, Yin Y, Lui SKL, Keegan S, Fenyo D, Smith DJ, et al. USP1-trapping lesions as a source of DNA replication stress and genomic instability. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].González-Garrido C, Prado F. Parental histone distribution and location of the replication obstacle at nascent strands control homologous recombination. Cell Rep. 2023;42:112174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Maloisel L, Ma E, Phipps J, Deshayes A, Mattarocci S, Marcand S, et al. Rad51 filaments assembled in the absence of the complex formed by the Rad51 paralogs Rad55 and Rad57 are outcompeted by translesion DNA polymerases on UV-induced ssDNA gaps. PLoS Genet. 2023;19:e1010639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Iwai S, Hanaoka F. Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase eta. EMBO J. 2000;19:3100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Sokol AM, Cruet-Hennequart S, Pasero P, Carty MP. DNA polymerase η modulates replication fork progression and DNA damage responses in platinum-treated human cells. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Srivastava AK, Han C, Zhao R, Cui T, Dai Y, Mao C, et al. Enhanced expression of DNA polymerase eta contributes to cisplatin resistance of ovarian cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4411–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Zhang Y, Yuan F, Wu X, Wang M, Rechkoblit 0, Taylor JS, et al. Error-free and error-prone lesion bypass by human DNA polymerase kappa in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Plosky BS, Frank EG, Berry DA, Vennall GP, McDonald JP, Woodgate R. Eukaryotic Y-family polymerases bypass a 3-methyl-2’-deoxyadenosine analog in vitro and methyl methanesulfonate-induced DNA damage in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2152–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Tissier A, McDonald JP, Frank EG, Woodgate R. poliota, a remarkably error-prone human DNA polymerase. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1642–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Biochemical evidence for the requirement of Hoogsteen base pairing for replication by human DNA polymerase iota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10466–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Zhang Y, Yuan F, Wu X, Taylor JS, Wang Z. Response of human DNA polymerase iota to DNA lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Thymine-thymine dimer bypass by yeast DNA polymerase zeta. Science. 1996;272:1646–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Shachar S, Ziv O, Avkin S, Adar S, Wittschieben J, Reissner T, et al. Two-polymerase mechanisms dictate error-free and error-prone translesion DNA synthesis in mammals. EMBO J. 2009;28:383–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Yoon JH, Prakash L, Prakash S. Error-free replicative bypass of (6-4) photoproducts by DNA polymerase zeta in mouse and human cells. Genes Dev. 2010;24:123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Washington MT, Minko IG, Johnson RE, Haracska L, Harris TM, Lloyd RS, et al. Efficient and error-free replication past a minor-groove N2-guanine adduct by the sequential action of yeast Rev1 and DNA polymerase zeta. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6900–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Deoxycytidyl transferase activity of yeast REV1 protein. Nature. 1996;382:729–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Kruchinin AA, Makarova AV. Multifaceted Nature of DNA Polymerase θ. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Carvajal-Garcia J, Cho JE, Carvajal-Garcia P, Feng W, Wood RD, Sekelsky J, et al. Mechanistic basis for microhomology identification and genome scarring by polymerase theta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:8476–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Seki M, Masutani C, Yang LW, Schuffert A, Iwai S, Bahar I, et al. High-efficiency bypass of DNA damage by human DNA polymerase Q. EMBO J. 2004;23:4484–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Yoon JH, McArthur MJ, Park J, Basu D, Wakamiya M, Prakash L, et al. Error-Prone Replication through UV Lesions by DNA Polymerase θ Protects against Skin Cancers. Cell. 2019;176:1295–309.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]