Abstract

Objective:

GABAA receptor subunit gene mutations are major causes of various epilepsy syndromes, including severe kinds such as Dravet syndrome. Although the GABAA receptor is a major target for antiseizure medications, treating GABAA receptor mutations with the receptor channel modulators is ineffective. Here we determined the effect of a novel treatment with 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) in the Gabrg2+/Q390X knockin mice associated with Dravet syndrome.

Methods:

We used biochemistry in conjunction with differential tagging of the wildtype and the mutant alleles, live brain slice surface biotinylation, microsome isolation, patch-clamp whole-cell recordings, and video-monitoring synchronized EEG recordings in a Gabrg2+/Q390X mice to determine the effect of PBA in vitro with recombinant GABAA receptors and in vivo with knockin mice.

Results:

We found that PBA reduced the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit protein aggregates, enhanced the wildtype GABAA receptor subunits’ trafficking and increased the membrane expression of the wildtype receptors. PBA increased the current amplitude of GABA evoked current in HEK293T cells and the neurons bearing the γ2(Q390X) subunit protein. PBA also proved to reduce ER stress caused by the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit protein, as well as mitigating seizures and EEG abnormalities in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice.

Significance:

This research has unveiled a promising and innovative approach for treating epilepsy linked to GABAA receptor mutations through an unconventional antiseizure mechanism. Rather than directly modulating the affected mutant channel, PBA facilitates the folding and transportation of wildtype receptor subunits to the cell membrane and synapse. Combining these findings with our previous study, which demonstrated PBA's efficacy in restoring GABA transporter 1 (encoded by SLC6A1) function, we propose that PBA holds significant potential for a wide range of genetic epilepsies. Its ability to target shared molecular pathways involving mutant protein ER retention and impaired protein membrane trafficking suggests a broad application in treating such conditions.

Keywords: GABAA receptors, epilepsy, Gabrg2+/Q390X knockin (KI) mice, 4-phenylbutyrate, ER stress

Introduction

GABRG2 is an established epilepsy gene, and mutations in GABRG2 are associated with a wide spectrum of epilepsy syndromes. Those clinical phenotypes range from febrile seizures, childhood absence epilepsy to generalized tonic-clonic seizures with febrile plus (GEFS+) and Dravet syndrome 1,2. GABRG2(Q390X) is one such mutation associated with GEFS+ and Dravet syndrome3. Previous work on this mutation has demonstrated that the mutant protein is not only a loss-of-function, but also has a dominant negative effect on the wildtype allele4,5. Gabrg2+/Q390X knockin (KI) mice show spontaneous generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), myoclonic jerks, sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP), anxiety, and impaired social activity and cognition, thus representing a mouse model of severe epilepsy5. Comparison of the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice with the Gabrg2+/− knockout mice without the mutant protein further validated that the dominant negative suppression of the GABRG2(Q390X) mutation6. The mutation causes loss of function, aggregation of the mutant protein and dominant negative suppression of the wildtype partnering subunit by the mutant protein, thus trapping the wildtype subunits in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)4. Although exciting work has been done for SCN1A mutation associated Dravet syndrome with antisense oligonucleotides via Targeted Augmentation of Nuclear Gene Output (TANGO) technology7, there is no treatment developed for GABRG2 mutation associated epilepsies. The heterozygous Gabrg2+/Q390X mice had reduced peak current amplitude of GABAergic mIPSCs and increased EEG abnormalities and seizure activity. The GABAA receptor modulator benzodiazepine only partially suppressed seizures, suggesting that more effective treatment options are needed6,8.

4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) is a chemical chaperone inducer. It has been demonstrated that chaperones can assist the folding of membrane proteins and accelerate their ER exit and membrane trafficking9. Therefore, chemical chaperones are potential therapeutic drugs that can improve ER retained protein stability and trafficking. We have previously demonstrated that PBA can restore GABA uptake in multiple cell models including human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived neurons and astrocytes10. We found that PBA reduced seizures in the knockin Slc6a1+/S295L mice associated with childhood absence and neurodevelopmental delay, in which PBA alone reduced the seizure activity by 76% 10. A previous study demonstrated that PBA could rescue Munc18-1 dysfunction, equivalent to mutation in STXBP1 associated with epileptic encephalopathies in C. elegans models11. Together, these studies have prompted a clinical trial on SLC6A1 and STXBP1 mediated developmental epileptic encephalopathies (NCT04937062).

Our work on a large cohort of SLC6A1 mutations demonstrates the common molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying SLC6A1 mutation mediated disorders12. Importantly, these molecular and cellular mechanisms overlap those in GABAA receptor subunit mutations associated with epilepsy1,4,13,14. This thus suggests that PBA could target the common molecular and cellular pathways in both groups of disorders and be used a common treatment option for both.

In this study, we used both HEK293T cells with overexpression of the recombinant GABAA receptors and the Gabrg2+/Q390X mouse associated with Dravet syndrome as model. We tested the effect of PBA on the total and surface expression of the major GABAA receptor subunits as well as on the channel function. Because of the propensity of the mutant subunit protein to form protein aggregates and cause ER stress, we isolated microsomes and analyzed the protein folding and expression of the wildtype γ2 and the partnering subunits in the presence of the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits inside ER. We also evaluated the impact of PBA on the amounts of aggregates and ER stress. At the behavioral level, we used video-monitoring synchronized EEG recordings to determine the in vivo efficacy of PBA in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The Gabrg2+/Q390X KI mouse line was developed and characterized in our previous work5. Mice used in the study were crossed with C57BL/6J mice for at least 8 generations and were between 2-4 months old. Both sexes were included. All experimental procedures were approved by Vanderbilt University Division of Animal Care.

Synchronized video-monitoring EEG recordings, EEG analysis with Seizure Pro software:

This is based on our standard lab protocol as previously described5,6,8. Mice were implanted with the EEG head mount followed by 7 days of recovery before the video-monitoring synchronized EEG recordings were conducted. For EEG recordings, the sampling rate is set at 400 Hz with a pre-amplifier gain of 100. EEG and EMG channels have a filter set per Pinnacle System user guide. EEG recordings are scored blindly by a skilled scorer using the Sirenia Seizure Pro software. A power analysis is performed using the theta frequency band of 5-7 Hz. We chose to measure 5-7 Hz SWDs because it is the mouse correlate of 2-4 Hz SWDs observed in humans. An average power is calculated using baseline recordings and applied to seizure analysis for recordings with treatment. Generalized tonic clonic seizures, myoclonic seizures and tonic seizures were scored. Seizures identified by the software were confirmed using video recordings of the period. The Racine scale was used for seizure identification (Stage 1: mouth/facial movements; Stage 2: head nodding; Stage 3: forelimb clonus; Stage 4: rearing; Stage 5: rearing and falling). The identified SWDs were then confirmed with video monitoring and compared across treated and non-treated recordings.

GABAA receptor subunit cDNAs

The cDNAs encoding human GABAA receptor α1, β2 and γ2 subunits were as described previously4,13. The GABRG2(Q390X) mutation was generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and was confirmed by DNA sequencing. FLAG tagged γ2 subunit plasmids were generated as previously described4,13.

PBA administration in vitro and in vivo

For PBA administration in cells, the stocking solution of PBA (2 Mol) was dissolved in DMSO. The most optimal dosage (2 mM) and duration (24 hr) were identified as in a previous study10 and used throughout the study. The dose of PBA in mice was chosen based on a dose–response experiment performed with increasing doses of PBA from 100 to 800 mg/kg in the Slc6a1+/S295L mice, in which we determined that the most optimal dose was 100 mg/kg. Here, mice of both sexes at 2-4 months of age were dosed with PBA (100 mg/kg, i.p. single dosing per day) or vehicle for 7 days. PBA solution was prepared by dissolving PBA in 0.9% normal saline and then titrating equimolecular amounts of PBA (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) and 1 Mol potassium hydroxide to pH 7.4. The working solution was stored at 4 °C. The brain tissues were harvested at day 8 and 24 hrs after PBA administration.

Cell cultures and transfection

Human embryonic HEK293T cells and mouse L929 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) to a final concentration of 10% FBS and 1% pencicillin/streptomycin. The cells were seeded in 60-mm2 cell culture dishes at a density of 4X105 24 hrs before transfection. A total of 3 μg cDNA was used. The protocol for Polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection that was used at a ratio of cDNA to PEI and 1:2.5 as well as immunoprecipitation and immunoblot were detailed in previous studies12,15-17.

Hippocampi were dissected from the brains of postnatal day 0 pups. The hippocampi of pups were sometimes combined by genotype. Dissociation of cells and cell culture and transfection procedures have been described previously. The neurons were plated on 35 mm dishes or cover slips at a density of 0.5-1×105 cells/ml and first maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 6 % fetal bovine serum for the first three days and then maintained with Neurobasal and B-27 supplement before experiment at day 14 to 17 in culture dish. PBA (2 mM) was applied to the dish 24 hrs before patch clamp recordings but was not present during recordings.

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings

Lifted whole cell recordings were obtained from transfected HEK 293-T cells as previously described4,13. Cells were voltage-clamped at −50 mV and ECl was 0 mV. For mIPSC recordings in hippocampal neurons from the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice, we followed protocol in our previous study on the same mutation4. Hippocampal neurons were cultured from the postnatal day 0 pups and recorded at the 15th to 17th day old in culture. Neurons were voltage-clamped at −60 mV, and tetrodotoxin (TTX) (1 μM) was added to block action potentials. D-(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5; 40 μM) and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; 20 μM) were added to block NMDA and AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory synaptic currents, and 2-hydroxysaclofen (100 μM) was added to block GABAB receptor currents. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The mIPSCs were abolished by addition of the GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline (10 μM). Analysis of mIPSC frequencies and amplitudes were made using the Mini Analysis program by Justin Lee, which is available online.

Microsome Isolation and Comparative Limited Proteolysis:

We used the protocol that has been established for studying the cystic fibrosis mutation ΔF50818. We first isolated microsomes, which are artificial, vesicle-like structures formed from pieces of the endoplasmic reticulum during tissue homogenization. We then digested the isolated protein from the microsomes to determine its folding efficiency by normalizing the amount of protein that is resistant to trypsin digestion over the total amount of protein.

Microsome Isolation:

Microsomes were isolated from human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells transfected with wild-type or mutant GAT-1 cDNAs using the transfection reagent PEI at a DNA: PEI ratio of 1:2.5. Five 100mm2 dishes each containing ~1.5 million transfected HEK cells were prepared for each experimental condition. Microsome isolation was performed using Sigma-Aldrich’s Microsome Isolation Kit (MAK340) and all steps were carried out at 4°C. The DMEM medium was removed, and the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The cells were detached using a cell scraper, suspended in 5ml PBS, and subsequently collected using a dropper/pipette. The cells were centrifuged at 1000xg for 5 min at 4°C, after which the supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was re-suspended in 1.5ml of ice-cold Homogenization Buffer (HB). The re-suspended cells were then homogenized using 30 strokes of a pre-chilled Dounce Homogenizer. The homogenate was transferred to 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes, vortexed for 30 seconds, and centrifuged at 10,000xg for 15min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was kept and centrifuged at 20,000xg for 20 minutes. The resulting pellet (containing the isolated microsomes) was washed with HB and then (following removal of HB) re-suspended in Storage Buffer without protease inhibitors added and checked for protein concentration.

Comparative Limited Proteolysis:

The proteins resulting from microsome isolation were subjected to proteolysis by the enzyme Trypsin. Trypsin at 5 to 100 μg/ml was tested and 20 μg/ml was identified to be optimal for limited proteolysis assay and was thus used in the study. The protein was digested for 15 minutes at 4°C, after which 2μl of Sigma-Aldrich’s Protease Inhibitor Cocktail was added to halt proteolysis. The degree of digestion in each condition was compared after protein fractionation using a Western Blot.

Data quantifications and statistical analysis

For biochemistry experiments, subunit integrated density values (IDVs) were quantified on immunoblots by using the Quantity One or Odyssey fluorescence imaging system (Li-Cor). The IDVs were normalized to the loading control ATPase or β-actin first and then to the designated controls such as untransfected or wildtype depending on each experiment. The fluorescence intensity values were quantified by using ImageJ. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software). Details on statistical analysis and experimental design, including tests performed, exact p values, and sample sizes are provided in the result section describing each figure, or within the legend of each figure. All data values were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), including one-way and two-way ANOVA, unpaired Student t tests, one sample t test were used. Post hoc and a priori Bonferroni comparisons or Turkey test were conducted to evaluate individual mean comparisons where appropriate. All analyses used an alpha level of 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

Results

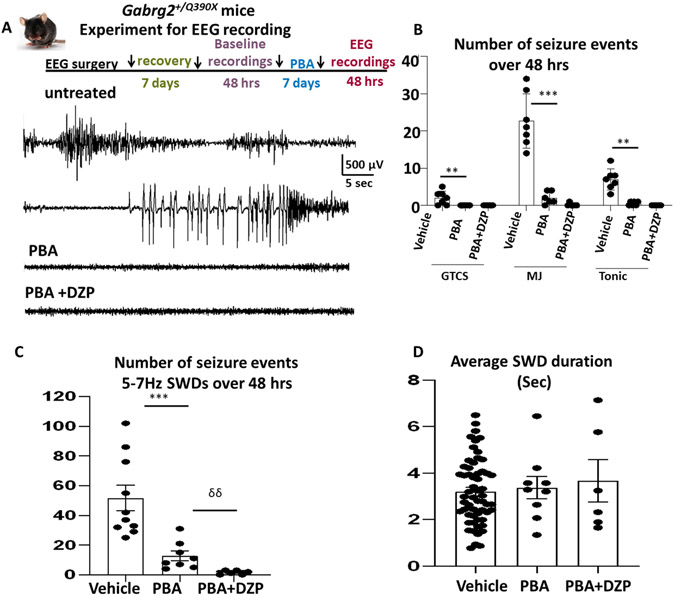

4-phenylbutyrate applied alone or in combination with diazepam mitigated seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice

We have previously demonstrated that PBA reduced seizures in other mouse models, including those caused by mutations in the GABA transporter 1 (GAT-1) encoding gene SLC6A1 10. Because of the shared ER retention of the mutant protein and reduced membrane expression of the functional GABAA receptors 1,4,13 or GABA transporter-112, we then tested PBA in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice. We used the same experimental paradigm for PBA treatment as shown in schematic depiction of experimental paradigm for EEG recordings (Figure 1A). The mice were treated with PBA (100 mg/kg, single dose, daily for 7 days) alone or in combination with diazepam (0.3mg/kg). Representative EEG recordings show that the heterozygous Gabrg2+Q390X (het) KI mice had generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS) and frequent absence like spike wave discharges (SWDs) as well as myoclonic jerks (MJs) during baseline recordings (Figure 1A). EEG traces recorded in the vehicle (normal saline 100 μl) treated or PBA treated alone or with a combination of PBA and diazepam (0.3mg/kg, single dose, daily) 6 for 7 days were presented. The total number of GTCS, MJs or tonic seizure events were drastically reduced, both with PBA treatment alone and in combination with Diazepam during the 48 hrs of recordings (Figure 1B). The total number of 5-7 Hz SWDs was also reduced with PBA treatment alone and also in combination with DZP (Figure 1C). The combined treatment of PBA and DZP almost completely abolished the SWDs (51.7±8.5 for baseline vs 12.75±3.27 for PBA and 1.5±0.56) F(2,21)=16.94. However, the average duration of 5-7 Hz SWDs in the Gabrg2+Q390X mice was similar between the vehicle treated and the drug treated groups (Figure 1D). In addition to mitigating seizures, PBA also improved the cognition (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1. 4-phenylbutyrate alone or in combination with diazepam mitigated seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice.

(A). Schematic depiction of experimental paradigm for EEG recordings and PBA and diazepam treatment. Representative EEG recordings show that the heterozygous Gabrg2+Q390X (het) KI mice had generalized tonic clonic seizures and frequent absence like spike wave discharges (SWDs) as well as myoclonic jerks during baseline recordings. Comparison of EEG traces recorded after the vehicle (normal saline 100 μl) treated or after treatment with PBA alone (100 mg/kg, ip, single dose, daily) or with a combination of PBA and diazepam (0.3mg/kg) for 7 days. B. Graph showing the total number of generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS), myoclonic jerks (MJ) or tonic seizure events calculated by Seizure Pro per 24 hrs. C. Graph showing the total number of 5-7 Hz SWDs calculated by Seizure per 24 hrs. D. Average duration of 5-7 Hz SWDs in the Gabrg2+Q390X mice treated with vehicle or drugs. In B, ** P< 0.01; *** P< 0.001 PBA vs vehicle. In C, *** P< 0.001 PBA vs vehicle; δδ p < 0.01 PBA+DZP vs PBA treated, Values were expressed as mean ± S.E.M, N=7 mice for vehicle and 6 mice for PBA or PBA plus DZP)

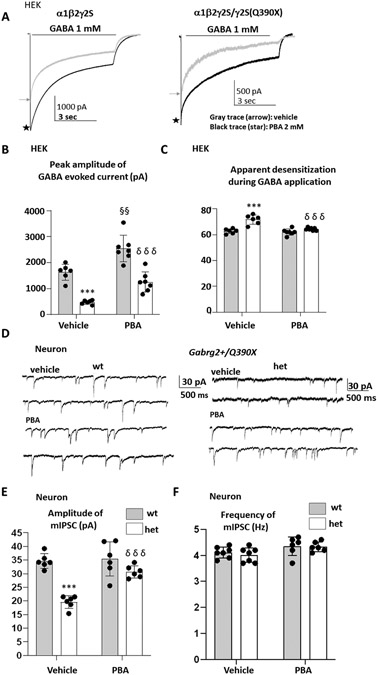

4-phenylbutyrate increased the GABA evoked current amplitude in the HEK293T cells or hippocampal neurons expressing the γ2(Q390X) subunit

We then determined the effect of PBA on the function of GABAA receptors, we used wildtype and mutant γ2S subunit cDNA constructs. We recorded from HEK 293-T cells following cotransfection of α1 and β2 subunits with wild-type γ2S subunits (1:1:1 cDNA ratio) or heterozygous γ2S/γ2S(Q390X) subunits (1:1:0.5:0.5 cDNA ratio) treated with vehicle or PBA (2 mM) for 24 hrs. we used “wildtype” and “heterozygous” receptors and currents to indicate that we transfected cells with non-mutant (wildtype) cDNAs, an equal mixture of non-mutant and mutant cDNAs (heterozygous) to facilitate descriptions of the transfection techniques, and no genetic mechanism or specific assembly patterns were implied.

Currents in the HEK293T cells expressing the wildtype α1β2γ2S or the mutant α1β2γ2S/γ2S(Q390X) receptors were evoked by application of 1 mM GABA for 6 sec (Figure 2A). PBA increased GABA evoked current in both the wt (wt vehicle vs wt PBA (1635± 125.2 vs 2127± 173.9) and het receptors (het vehicle vs het PBA 474.4 ± 31 vs 894.5 ± 135.9 pA), F(1,22)=72.93, (n = 6 patches) (Figure 2A, B). There is more current desensitization in the het receptors (wt vs het: 62.67%± 0.76% vs 71.67%± 1.478%) than the wildtype but PBA treatment normalized the current loss (Figure 2C). We then recorded GABAergic mIPSCs in the hippocampal neurons cultured from the wildtype or the heterozygous postnatal day 0 pups. PBA (2 mM) treatment increased the amplitude of mIPSCs in the heterozygous (19.19 ± 0.90 pA for the vehicle vs 30.70 ± 0.90 pA for PBA) but not the wildtype neurons (34.69 ± 0.93 PA for vehicle vs 35.42 ± 2.56 PA for PBA) F(1,22)=49.84, (Figure 2 E) There was no change of the frequency of mIPSC in either the wildtype or the heterozygous neurons (Figure 2F). This suggests that PBA increased the GABAergic neurotransmission via a post-synaptic mechanism by increasing the functional GABAA receptors at synapse instead of increasing GABA release and channel frequency.

Figure 2. 4-phenylbutyrate increased the current amplitude of GABAA receptors in HEK293T cells or hippocampal neurons bearing the GABRG2(Q390X) mutation.

(A) GABAA receptor currents were obtained from HEK 293-T cells cotransfected with wild-type α1 and β2 subunits and γ2S (1:1:1 cDNA ratio; wt) or heterozygous γ2S/γ2S(Q390X) (1:1:0.5:0.5 cDNA ratio; het) subunits with application of 1 mM GABA applied for 6 sec. The cells were treated with vehicle or PBA for 24 hrs prior to patch clamp recordings (gray trace marked with an arrow for vehicle treated and black trace marked with a star for PBA treated). (B, C) The amplitudes (B) or the extent of desensitization (C) of GABAA receptor currents in the vehicle or PBA treated cells were plotted. (D-F). Representative traces of GABAergic mIPSCs from 15-17 days old hippocampal neurons cultured from the wildtype (wt) and the Gabrg2+/Q390X het pups at postnatal day 0 (D). The amplitude (E) or frequency (F) of GABAergic mIPSCs in the hippocampal neurons from wt or het Gabrg2+/Q390X mice were presented as mean ± S.E.M (n = 6-7 of wildtype or the het neurons cultured from the four different pairs of mouse pups. In B, C, E, ***p < 0.001 vs wt; §§ P<0.01 vs wt vehicle; δδδ p < 0.001 vs het vehicle. Values were mean ± SEM.

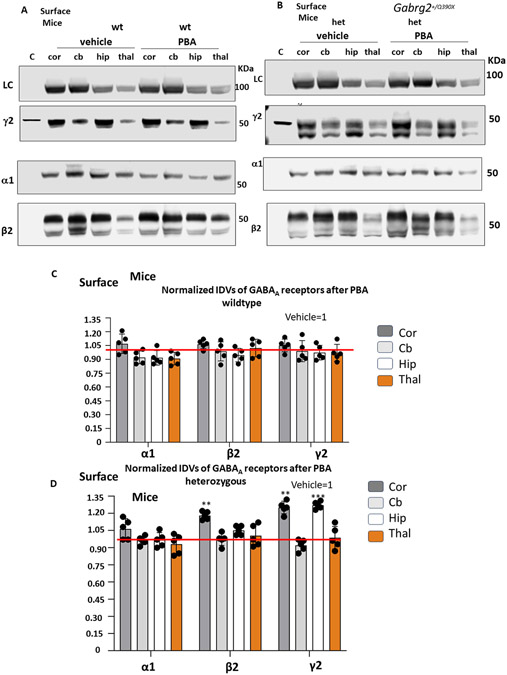

4-phenylbutyrate increased the surface expression of wildtype subunits of GABAA receptors in Gabrg2+/Q390X mice

We have previously identified that PBA can increase the expression of functional GAT-1 in Slc6a1+/S295L mice associated with absence epilepsy10. Reduced seizure activity in PBA-treated Gabrg2+/Q390X mice could be due to the increased expression of the functional GABAA receptors. We then profiled the wildtype γ2 subunit with a specific antibody that only recognizes the wildtype allele, the partnering wildtype α1 and the β2 subunit protein expression in the mutant mice. We have previously identified that the wildtype α1, β2 and γ2 subunits were reduced in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice5. We then treated wildtype or heterozygous mice between 2-4 months old with either saline or PBA for 7 days. The lysates from cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus and thalamus were surveyed. Our previous work indicates that the heterozygous mice had reduced GABAA receptor subunit expression in all surveyed brain regions. PBA treatment did not change the expression of the GABAA receptor expression in the wildtype mice (Figure 3A, 3C). However, in the heterozygous mice, PBA treatment increased the expression of β2 subunit in the cortex and the expression of γ2 subunit in the cortex and hippocampus when normalized to the het treated with vehicle, which is taken as 1 (het PBA α1: 1.04 ±0.12 for cortex, 0.95 ±0.05 for cerebellum; 0.97±0.03 for hippocampus; 1.02±0.03 for thalamus; het PBA β2: 1.18 ±0.05 for cortex; 0.97 ±0.02 for cerebellum; 1.05 ±0.07 for hippocampus; 0.97 ±0.011 for thalamus; het PBA γ2: 1.25 ±0.06 for cortex; 0.93 ±0.07 for cerebellum; 1.27 ±0.04 for hippocampus; 1.05 ±0.14 for thalamus) (F(6,36)=1.188; F(2,36)=3.041; F(3,36)=4.363)) (Figure 3B and 3D). Our findings indicate that PBA treatment results in brain region and subunit specific increase of GABAA receptor subunits. PBA specifically increase γ2 subunit in the heterozygous mice. suggesting that the response of γ2 subunit to PBA is cell-text specific. We also determined the total level of γ2 subunit in the mice treated with PBA and the total γ2 subunit was only increased in the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig 2). There was a trend of increase in the γ2 subunit expression in the cortex of PBA treated heterozygous mice, but it didn’t reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig 2). It seems that the extent of the receptor protein expression at total level is less than the increase of protein at the cell surface level. This may suggest that PBA facilitates the GABAA receptor protein trafficking in addition to increasing the total protein expression.

Figure 3. 4-phenylbutyrate increased the cell surface expression of wildtype partnering subunits of GABAA receptors in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice.

(A) The surface protein isolated with cell surface biotinylation from different brain regions (cortex (cor), cerebellum (cb), hippocampus (hip) and thalamus (thal)) from the wildtype (wt) (A) and heterozygous (het) (B) mice at 2-4 months old, untreated or treated with vehicle or PBA (100mg/kg) for 7 days were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-γ2, α1 or β2 antibody. C, D. Integrated density values (IDVs) for GABAA receptor α1, β2 and γ2 subunits from wild-type and het KI were normalized to the Na+/K+ ATPase as loading control (LC) in each specific brain region and plotted. N=4 from 4 pairs of mice. In the wt or the het mice, the vehicle treated in each brain region was taken as 1. N=4 from 4 pairs of mice. Values were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. In D, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle treated).

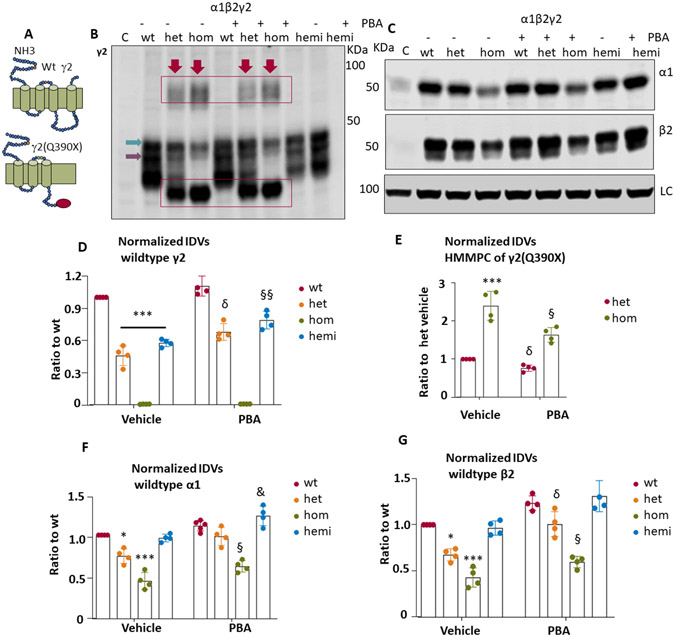

4 phenylbutyrate reduced the mutant protein aggregates but increased the trafficking of wildtype partnering subunits of GABAA receptors in HEK293T cells

As mentioned previously, we have identified that PBA increased the expression of GAT-1 in various cell models and the Slc6a1+/S295L and Slc6a1+/A288V knockin mice10. We then determined the impact of PBA on the expression of the GABAA receptor subunits. We surveyed the recombinant wildtype α1β2γ2 receptors, the disease-representing heterozygous α1β2γ2/γ2(Q390X) receptors and the mutant α1β2γ2(Q390X) receptors. We included the hemizygous α1β2γ2/− receptors as reference for the impact of the γ2(Q390X) subunit. The mutation results in a mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit with 78 amino acid truncations at the c-terminus of the protein peptide (Figure 4A) subunit and a complete loss of the function of the subunit. We first determined the expression of the wildtype and the mutant γ2 subunit with an antibody that recognized both the wildtype and the mutant γ2 subunit (Figure 4B) as well as the wildtype partnering α1 and β2 subunits (Figure 4C) in the cells expressing the wildtype, the mixed or the “heterozygous” (het), the “homozygous” (hom) and the “hemizygous” (hemi) conditions treated with vehicle or with PBA 2mM. The wildtype γ2 subunit was reduced in the heterozygous or the hemizygous condition (Figure 4D) (0.456±0.068 for het; 0.57±0.06 for hemi, F(3.24)=383.4) but was increased with PBA administration (0.678±0.02 for het; 0.78±0.09) for hemi). A faint up band was detected below 50 KDa across all conditions as arrow pointed. This is often observed with the anti-γ2 antibody from Synaptic System (Cat No. 224 004) and is likely a nonspecific protein. Interestingly, the high protein mass molecular weight protein complex observed in the mutant conditions was reduced with PBA treatment ((0.756±0.086 for het PBA vs 1 for het vehicle; 1.664±0.13 for hom PBA vs 2.34±0.25 for hom vehicle, F(1,12)=110.8)) (Figure 4E). However, for the partnering α1 and β2 subunits, a similar reduction with vehicle treated and upregulation with PBA treatment was observed. A ~25-35% increase was in the wildtype α1 and β2 subunits was observed (Figure 4F and G).

Figure 4. 4-phenylbutyrate increased the total wildtype partnering subunits of GABAA receptors and reduced the mutant protein aggregates.

(A) Schematic presentation of human GABRG2-encoded γ2 subunit and the γ2(Q390X) mutant subunit protein topology. The red dot represents the relative locations of the γ2(Q390X) subunit mutation. (B, C) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with α1, β2 and γ2, γ2(Q390X) for 2 days. DMSO (0.1%) or 4-phenylbutyrate (2 mM) in 100 μl of DMEM was applied in cells for 24hrs before harvest. The total cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The membrane was immunostained with polyclonal rabbit anti-γ2 antibody (B) or a mouse monoclonal anti-α1 or anti- β2 antibody (C). The ATPase was used as loading control (LC) for all subunits. The wildtype (wt) designates the cells expressing the wildtype α1, β2 and γ2 subunits at a cDNA ratio of 1;1;1. The “heterozygous” (het) designates the cells expressing the wildtype α1, β2, the γ2 and γ2(Q390X) subunits at a cDNA ratio of 1:1:0.5:0.5. The “homzygous” (hom) designates the cells expressing the wildtype α1, β2 and γ2(Q390X) subunits at a cDNA ratio of 1:1:1 while the “hemizygous” (hemi) designates the cells expressing the wildtype α1, β2, the γ2(Q390X) subunits and the empty vector pcDNA at a cDNA ratio of 1:1:0.5:0.5. The band pointed by the green arrow is a nonspecific band while the one pointed by the purple arrow is the wildtype. Red boxed regions represent the mutant γ2(Q390X) monomer or dimers. (D) The relative total protein integrated density values (IDVs) of the wildtype γ2 subunit in each condition were normalized to those obtained with expression of wildtype γ2 subunit with α1 and β2 subunit cDNAs. E. The IDVs of the high molecular mass protein complexes (HMMPC) in the mutant heterozygous and homozygous conditions were analyzed. (F, G). The relative total protein integrated density values (IDVs) of the wildtype α1 (F) or β2 (G) subunits in the mutant conditions were normalized to those obtained with coexpression of wildtype γ2 subunit with α1 and β2 subunit cDNAs. In D, *** P< 0.001 vs wt, δ P< 0.05 vs “het” vehicle; §§P< 0.01 vs hemi vehicle. In E, *** P< 0.001 vs “het” vehicle; δ P< 0.05 vs “het” vehicle; § P< 0.05 vs “hom” vehicle. In F and G, *P< 0.05; *** P< 0.001 vs wt vehicle, δ P< 0.05 vs “het” vehicle; §P< 0.05 vs “hom” vehicle; & P<0.05 vs “hemi” vehicle. In D to G, n=6 blots from 6 batches of transfections in 6 batches of cells. Mean ± SEM).

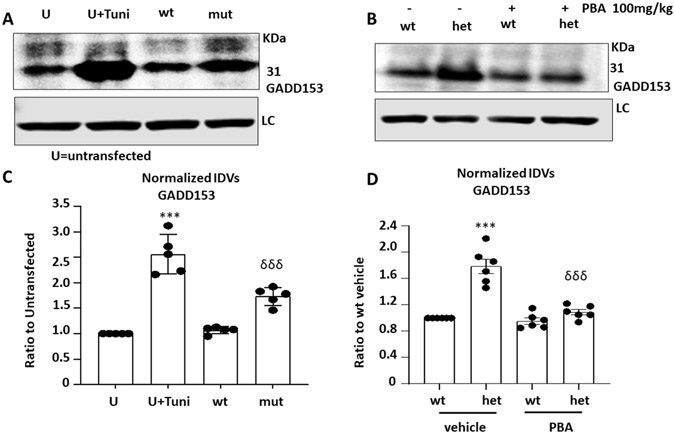

4-phenylbutyrate reduced the ER stress in the cells expressing the mutant receptors and the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice

Our previous work demonstrated that the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits are retained inside ER4. Overload of the misfolded or unfolded protein inside ER could cause ER stress and activate the unfolded protein response (Figure 5A). Total lysates from Mouse L929 cells transfected with wildtype or mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits in combination with the wildtype α1 and β2 subunits for 48 hrs. Sister cultures were treated with or without tunicamycin (10μg/ml) for 16 hrs before harvest (Figure 5A, 5C). Equal amounts of the protein were loaded, and the membranes were immunoblotted with an antibody against GADD153. The cells treated with tunicamycin had increased GADD153 expression (2.556± 0.174 for tunicamycin treated vs 1 for untreated). The cells expressing the α1β2γ2(Q390X) receptors also had increased GADD153 expression but to a lesser extent (1.73± 0.079 for mut vs 1.068± 0.031 for mut, F=56.03). In the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice, we surveyed the cortex, as we have extensively studied the subcellular localization and accumulation of the γ2 subunits in the cortex5,6. Total lysates from the cortex of wildtype or heterozygous Gabrg2+/Q390X mice treated with vehicle or 4-phenylbutyrate (100mg/kg) for 7 days were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The total amount of endogenous GADD153 in the cortex of the heterozygous mice were normalized to wildtype level (1.788 ± 0.11 for het vs 1.09 ± 0.04 for het PBA, 1 vs 0.95 ± 0.047, F=37.74) (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. 4-phenylbutyrate reduced the ER stress caused by the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit protein.

(A). Total lysates from Mouse L929 cells transfected with the wildtype or the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits in combination with the wildtype α1 and β2 subunits for 48 hrs. Sister cultures were treated with or without tunicamycin (10μg/ml) for 16 hrs before harvest. (B). Total lysates from the cortex of wildtype or heterozygous Gabrg2+/Q390X mice treated with vehicle or 4-phenylbutyrate (100mg/kg) for 7 days were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Equal amounts of the protein were loaded and the membranes were immunoblotted with GADD153. B-actin was used as a loading control (LC). (C, D). The total amounts of endogenous GADD153 were normalized to untreated controls (U) (C) for Mouse L929 cells or to vehicle treated wildtype (wt) mice (D). In C, ***p < 0.001 vs U, δδδ p<0.001 vs wt., N=5 batches of transfection in different batches of cells. In D, ***p < 0.001 vs wt; δδδ p<0.001 vs het vehicle. N=6 mice for each group. Mean ± SEM.

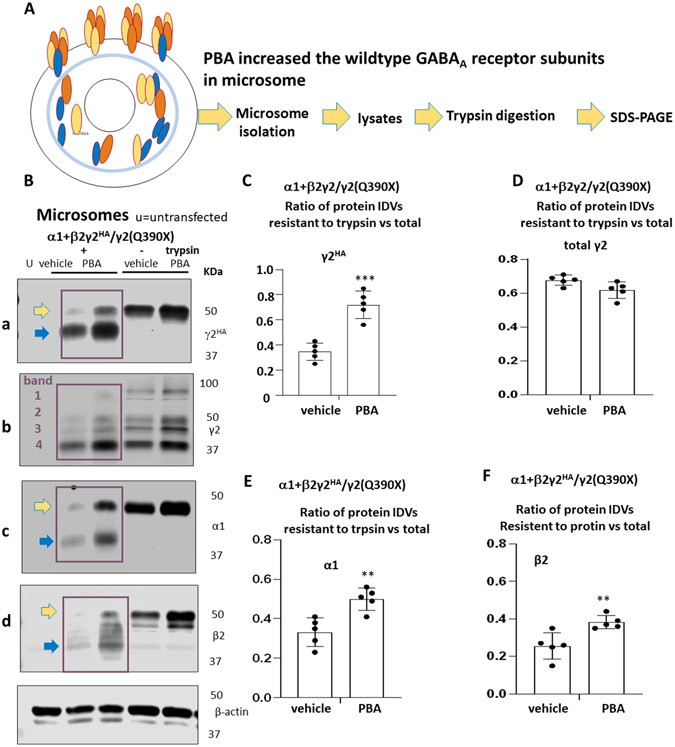

4-phenylbutyrate increased folding and stabilized the wildtype GABAA receptor subunits inside the ER

The increased GABA current is likely due to the increased functional GABAA receptor at cell membrane and synapse. We then performed microsome isolation and limited proteolysis on the protein within the microsomes. This was done to assess the protein folding efficiency within the ER following PBA treatment. (Figure 6A). We first isolated microsomes from cells expressing the mutant heterozygous receptor, treated with vehicle or PBA. Protein lysates of microsomes were either undigested or digested with trypsin. The ratio of remaining protein after digestion over the total undigested protein was measured. Trypsin at 20 μg/ml was tested to be optimal for limited proteolysis assay. The wildtype γ2 subunit was tagged with HA, which ran as one band before trypsin digestion. We identified four bands of the γ2 subunit in microsome (Figure 6B), which is not normally observed in the total protein lysate. These four bands may include both γ2HA and γ2(Q390X) subunits. PBA treatment increased the wildtype γ2 subunit expression in both undigested and trypsin-digested protein lysates. Importantly, the ratio of the digested γ2HA subunit protein over undigested γ2HA subunit was higher for the PBA treated than for the vehicle treated, suggesting that wildtype γ2 subunit protein in PBA treated was more resistant to trypsin digestion and more tightly folded (γ2HA 0.346 ±0.03 vs 0.72 ±0.049, t=6.446, df=8) (Figure 6C). The same pattern was observed for the α1 (α1: 0.332 ±0.03 vs 0.50 ±0.025, t=4.094, df=8) and β2 subunit (0.25 ±0.03 vs 0.38 ±0.016, t=3.536, df=8) (Figure 6E and 6F). However, this phenomenon was not observed in the γ2 total protein, which is mainly contributed by the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit due to the slow degradation of the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit 19(0.677 ±0.013 vs 0.62 ±0.021, t=2.275, df=8) (Figure 6D). Our findings suggest that PBA not only increased the expression of the wildtype α1β2γ2 receptors, but also enhanced the folding of the receptor protein. Increased amount of properly folded GABAA receptor may increase brain inhibition and reduce brain excitability, thus mitigating seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 6. 4-phenylbutyrate increased the folding of the wildtype subunits in the mutant α1β2γ2/γ2(Q390X) receptors.

(A). Schematic depiction of limited proteolysis including microsome isolation, trypsin digestion and SDS-PAGE. (B). Lysates of microsome isolated from HEK293T cells expressing the α1β2γ2/γ2(Q390X) receptors treated with vehicle or 4 phenylbutyrate (PBA 2mM) were undigested or digested with trypsin (100μg/ml). The lysates were analyzed with SDS-PAGE and the membrane was immunoblotted with antibodies that recognizes the wildtype γ2HA, the total γ2, β2 or α1 subunits. The γ2HA subunits were run with one main band (panel a); the total γ2 (γ2HA and γ2(Q390X) subunits were run with four bands (panel b, band 1,2,3,4). The α1 subunits (panel c) were run with one main band while the β2 subunits were run with two bands (panel d). In B panel a,b,d, yellow arrow stands for undigested while the cyan arrow stands for digested protein. All the bands in the purple boxed region were included in quantification. (C-F). Protein IDVs of the wildtype γ2HA subunits (C), the total γ2 subunit (wildtype γ2HA and the γ2(Q390X) subunits) (D), the α1 subunit (E) or the β2 subunit (F) after PBA treatment was normalized to vehicle (DMSO) treated. Values were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. In C to F. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; PBA vs vehicle. N=5 batches of transfection in 5 different batches of cells.

Discussion

Severe epilepsy syndromes like Dravet syndrome and other developmental and epileptic encephalopathies 20 currently lack an effective treatment, and approximately 35% of epilepsy patients continue to experience seizures despite existing therapies. The majority of current treatment approaches focus on channel function, limiting their effectiveness to specific types of epilepsy and lacking broad applicability. While there are promising advancements in gene therapies and antisense oligonucleotides, these methods often come with high costs and are tailored to specific genes or mutations, limiting their widespread use. Despite advances in treating epilepsy mutations affecting GABAA receptors, a major antiseizure drug target, these therapies remain inadequate. The situation is even more challenging for lesser-known epilepsy gene mutations. Consequently, there is a pressing need for more effective and disease-modifying treatment alternatives for epilepsy.

PBA represents a novel treatment paradigm, as it targets the common signaling molecules inside the ER that are likely disturbed in at least a subset of genetic epilepsy, such as Dravet syndrome as reported in Gabrg2+/Q390X mouse model21. Disturbed ER signaling could induce a cascade of changes in signaling pathways, including increased neuroinflammation. To date, PBA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), sorbitol and trehalose are known to function as chemical chaperones. Among them, PBA has been reported to improve the membrane trafficking of mutant CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator), which is found in certain families with cystic fibrosis22. Additionally, 4-PBA has been reported to alleviate ER stress induced by the Pael receptor, which is thought to be accumulated in PARK2, one type of inherited Parkinson’s disease23,24.

We have previously reported that PBA can restore GABA uptake for SLC6A1 mutations and reduce seizures in the Slc6a1+/S295L mice 10. We now identified that PBA could mitigate seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice associated with Dravet syndrome. PBA alone reduced seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice and PBA in combination with diazepam further improved seizure suppression. PBA reduced all types of seizures, including GTCS, myoclonic jerks and absence seizure activity. This implicates that PBA could be used in various epilepsy syndromes, including those other than mutations in GABA transporter and GABAA receptor mutations, because it targets the common ER protein network re, folding and degradation. However, this requires further elucidation in both human patient mutation bearing cell and mouse models.

It is important to note that PBA enhanced the trafficking of the wildtype GABAA receptor subunits and reduced ER stress in both cell and mouse models bearing the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits. In the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice, PBA specifically increased the wildtype subunit at the cell surface but not the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit. The evidence that PBA can enhance the wildtype protein expression implicates its potential application in various genetic epilepsies, especially those nonsense or premature stop codon generating mutations. Increased membrane expression of the GABAA receptors is correlated with the increased function of the GABAA receptors at the cell surface or synapse. Reduced ER stress marker GADD153 expression indicates more efficient protein ER exit or less clogging of the mutant protein. This profile of improved GABAA receptor protein trafficking and reduced ER stress underlies the reduced seizures after PBA treatment in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice. The notion from this finding is consistent with the much less severe seizure phenotype in Gabrg2+/− knockout (KO) mice, in which there is no dominant negative suppression of the mutant γ2(Q390X) protein6. The Gabrg2+/− knockout (KO) mice has been reported to exhibit anxiety without seizures 15,25 or only with the infrequent absence seizures6. Additionally, reduced ER stress could reduce neuroinflammation, which is another contributing factor to the disease phenotype in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mouse21. However, the effect of PBA in reducing neuroinflammation in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice and in genetic epilepsy needs further elucidation.

Our data indicates the wildtype receptor subunits in PBA treated cells are more resistant to trypsin digestion (Figure 6), suggesting that PBA can enhance the folding efficiency of the wildtype GABAA receptors in addition to enhancing clearance of the misfolded protein aggregates. PBA is a hydrophobic chaperone, and it is generally believed that PBA can refold the mutant protein by patching the exposed hydrophobic regions of the unfolded or misfolded mutant protein with its hydrophobic side, thus preventing protein aggregation. It is therefore more likely to be beneficial for missense mutations. Our study provides novel insights that PBA can increase the folding efficiency and facilitate the trafficking of the wildtype GABAA receptor membrane trafficking in the cell expressing a nonsense mutation like GABRG2(Q390X). Considering all the heterozygous patients have an intact wildtype allele, this thus expands the application of PBA for a much broader patient population by leveraging the wildtype allele.

Our study provides direct measurement of the relative protein stability of wildtype GABAA receptor subunits in microsome after PBA treatment using a limited proteolysis assay with trypsin. We quantified the relative conformation stability of the wildtype GABAA subunits in presence of the mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits as a metric for the relative protein folding degree. The same method has been applied to other membrane proteins including CFTR18. Folded proteins are expected to be more compact, and thus more resistant to trypsin digestion than misfolded, unfolded or partially folded proteins, which are thus more resistant to trypsin digestion. Our data indicate that all the wildtype partnering subunits were more resistant to trypsin digestion after PBA treatment in the ER (Fig 6B-F). This is likely due to increased chaperone proteins which assist folding for the partnering subunit upon PBA treatment. These chaperones can facilitate wildtype GABAA receptor subunit folding and subsequently trafficking to the cell membrane, where it exerts function. PBA also reduces mutant γ2(Q390X) subunit aggregates. This suggests that PBA can synergistically reduce ER stress while promoting protein folding and membrane trafficking. Consequently, there will be more functional GABAA receptors at the cell surface or synapse, which lead to enhanced neuronal inhibition and mitigated seizures in Gabrg2+/Q390X mice associated with Dravet syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 2. The effect of 4 phenylbutyrate on the total γ2 subunit protein in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice.

(A) Lysates of the total protein from different brain regions (cortex (cor), cerebellum (cb), hippocampus (hip) and thalamus (thal)) of the wildtype (wt) and heterozygous (het) (A) mice at 2-4 months old, untreated or treated with vehicle or PBA (100mg/kg) for 7 days (B) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-γ2 antibody. C. Integrated density values (IDVs) for GABAA receptor γ2 subunits from wild-type and het KI were normalized to the Na+/K+ ATPase as loading control (LC) in each specific brain region first and then to the wildtype, which is taken as 1(C). D. IDVs for GABAA receptor γ2 subunits from het KI treated with vehicle or PBA were normalized to the Na+/K+ ATPase in each specific brain region first and then to the het treated with vehicle, which is taken as 1. (N=5 from 5 pairs of mice. Values were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Two way ANOVA with post hoc Turkey test. In C, ***p < 0.001 vs wt; in D **p < 0.01 vs vehicle).

Supplementary Figure 1. Gabrg2+/Q390X KI mice had impaired learning and memory that was rescued by 4-phenylbutyrate.

(A) A flow chart depicts an overview of the Barnes maze. (B) The Barnes maze had one target hole and eleven non-target holes. Mice were trained to find the target hole to escape during training sessions, which was hidden during the probe trial. (C) Time spent to locate the target hole was recorded and quantified for each day in each mouse genotype. (D) An hour after the last training trial, each mouse was allotted a 300 sec session to find the target hole. The total time spent at each of the 12 holes was assessed. (In C and D, ***p < 0.05 het vs wt); δ δ δ P<0.001 het vs het PBA. N=6 mice for wt and 7 mice for het. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Turkey test. All data were recorded by an over-head camera and generated by ANY-Maze software.

Supplementary Figure 3. Postulated mechanisms of 4-phenylbutyrate in mitigating seizures

We propose that 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) can enhance the folding and expression of the wildtype α1β2γ2 receptors and reduce the mutant γ2(Q390X) protein aggregates inside endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This thus reduces ER stress and facilitate GABAA receptor protein membrane trafficking and function. Increased GABAA receptor function at the neuronal surface reduce brain excitability and mitigate seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice associated with Dravet syndrome.

Key Points.

4- phenylbutyrate reduced ER stress and the mutant γ2(Q390X) protein aggregates.

4-phenylbutyrate promoted the wildtype GABAA receptor trafficking in the Gabrg2+Q390X mice.

4-phenylbutyrate increased GABA evoked current in the cells expressing the mutant receptors.

4- phenylbutyrate promoted the wildtype GABAA receptor subunit folding inside ER.

4- phenylbutyrate increased GABAA receptor function and mitigated seizures in the Gabrg2+Q390X- knockin mice.

Acknowledgements:

We are very grateful for constructive discussions with Dr. Martin Gallagher on EEG analysis. Research was supported by grants from Citizen United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE), Dravet Syndrome Foundation (DSF), Vanderbilt Brain Institute Award and Vanderbilt Clinical and Translation Science Award and NINDS R01 082635 and R01 NS121718 to J.Q.K.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement: None of authors declared any conflict of interest.

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Reference List

- 1.Kang JQ & Macdonald RL Molecular Pathogenic Basis for GABRG2 Mutations Associated With a Spectrum of Epilepsy Syndromes, From Generalized Absence Epilepsy to Dravet Syndrome. JAMA Neurol 73, 1009–1016 (2016). 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baulac S. et al. First genetic evidence of GABA(A) receptor dysfunction in epilepsy: a mutation in the gamma2-subunit gene. Nat Genet 28, 46–48 (2001). 10.1038/ng0501-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harkin LA et al. Truncation of the GABA(A)-receptor gamma2 subunit in a family with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Am J Hum Genet 70, 530–536 (2002). 10.1086/338710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang JQ, Shen W & Macdonald RL The GABRG2 mutation, Q351X, associated with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, has both loss of function and dominant-negative suppression. J Neurosci 29, 2845–2856 (2009). 10.1523/jneurosci.4772-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang JQ, Shen W, Zhou C, Xu D & Macdonald RL The human epilepsy mutation GABRG2(Q390X) causes chronic subunit accumulation and neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 18, 988–996 (2015). 10.1038/nn.4024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner TA et al. Differential molecular and behavioural alterations in mouse models of GABRG2 haploinsufficiency versus dominant negative mutations associated with human epilepsy. Hum Mol Genet 25, 3192–3207 (2016). 10.1093/hmg/ddw168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen AS et al. De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature 501, 217–221 (2013). 10.1038/nature12439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner TA, Smith NK & Kang JQ The therapeutic effect of stiripentol in Gabrg2(+/Q390X) mice associated with epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsy Res 154, 8–12 (2019). 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gil-Martínez J, Bernardo-Seisdedos G, Mato JM & Millet O The use of pharmacological chaperones in rare diseases caused by reduced protein stability. Proteomics 22, e2200222 (2022). 10.1002/pmic.202200222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nwosu G. et al. 4-Phenylbutyrate restored γ-aminobutyric acid uptake and reduced seizures in SLC6A1 patient variant-bearing cell and mouse models. Brain Commun 4, fcac144 (2022). 10.1093/braincomms/fcac144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guiberson NGL et al. Mechanism-based rescue of Munc18-1 dysfunction in varied encephalopathies by chemical chaperones. Nat Commun 9, 3986 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-018-06507-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mermer F. et al. Common molecular mechanisms of SLC6A1 variant-mediated neurodevelopmental disorders in astrocytes and neurons. Brain 144, 2499–2512 (2021). 10.1093/brain/awab207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang JQ & Macdonald RL The GABAA receptor gamma2 subunit R43Q mutation linked to childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures causes retention of alpha1beta2gamma2S receptors in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Neurosci 24, 8672–8677 (2004). 10.1523/jneurosci.2717-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang JQ, Shen W & Macdonald RL Two molecular pathways (NMD and ERAD) contribute to a genetic epilepsy associated with the GABA(A) receptor GABRA1 PTC mutation, 975delC, S326fs328X. J Neurosci 29, 2833–2844 (2009). 10.1523/jneurosci.4512-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai K. et al. A missense mutation in SLC6A1 associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome impairs GABA transporter 1 protein trafficking and function. Exp Neurol 320, 112973 (2019). 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.112973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mermer F. et al. Astrocytic GABA transporter 1 deficit in novel SLC6A1 variants mediated epilepsy: Connected from protein destabilization to seizures in mice and humans. Neurobiol Dis 172, 105810 (2022). 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum retention and degradation of a mutation in SLC6A1 associated with epilepsy and autism. Mol Brain 13, 76 (2020). 10.1186/s13041-020-00612-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du K, Sharma M & Lukacs GL The DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12, 17–25 (2005). 10.1038/nsmb882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang JQ, Shen W, Lee M, Gallagher MJ & Macdonald RL Slow degradation and aggregation in vitro of mutant GABAA receptor gamma2(Q351X) subunits associated with epilepsy. J Neurosci 30, 13895–13905 (2010). 10.1523/jneurosci.2320-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerrini R. et al. Developmental and epileptic encephalopathies: from genetic heterogeneity to phenotypic continuum. Physiol Rev 103, 433–513 (2023). 10.1152/physrev.00063.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen W, Poliquin S, Macdonald RL, Dong M & Kang JQ Endoplasmic reticulum stress increases inflammatory cytokines in an epilepsy mouse model Gabrg2(+/Q390X) knockin: A link between genetic and acquired epilepsy? Epilepsia 61, 2301–2312 (2020). 10.1111/epi.16670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh OV, Pollard HB & Zeitlin PL Chemical rescue of deltaF508-CFTR mimics genetic repair in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 7, 1099–1110 (2008). 10.1074/mcp.M700303-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ono K. et al. A chemical chaperone, sodium 4-phenylbutyric acid, attenuates the pathogenic potency in human alpha-synuclein A30P + A53T transgenic mice. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15, 649–654 (2009). 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu N. et al. The peroxisome proliferator phenylbutyric acid (PBA) protects astrocytes from ts1 MoMuLV-induced oxidative cell death. J Neurovirol 8, 318–325 (2002). 10.1080/13550280290100699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crestani F. et al. Decreased GABAA-receptor clustering results in enhanced anxiety and a bias for threat cues. Nat Neurosci 2, 833–839 (1999). 10.1038/12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 2. The effect of 4 phenylbutyrate on the total γ2 subunit protein in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice.

(A) Lysates of the total protein from different brain regions (cortex (cor), cerebellum (cb), hippocampus (hip) and thalamus (thal)) of the wildtype (wt) and heterozygous (het) (A) mice at 2-4 months old, untreated or treated with vehicle or PBA (100mg/kg) for 7 days (B) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-γ2 antibody. C. Integrated density values (IDVs) for GABAA receptor γ2 subunits from wild-type and het KI were normalized to the Na+/K+ ATPase as loading control (LC) in each specific brain region first and then to the wildtype, which is taken as 1(C). D. IDVs for GABAA receptor γ2 subunits from het KI treated with vehicle or PBA were normalized to the Na+/K+ ATPase in each specific brain region first and then to the het treated with vehicle, which is taken as 1. (N=5 from 5 pairs of mice. Values were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Two way ANOVA with post hoc Turkey test. In C, ***p < 0.001 vs wt; in D **p < 0.01 vs vehicle).

Supplementary Figure 1. Gabrg2+/Q390X KI mice had impaired learning and memory that was rescued by 4-phenylbutyrate.

(A) A flow chart depicts an overview of the Barnes maze. (B) The Barnes maze had one target hole and eleven non-target holes. Mice were trained to find the target hole to escape during training sessions, which was hidden during the probe trial. (C) Time spent to locate the target hole was recorded and quantified for each day in each mouse genotype. (D) An hour after the last training trial, each mouse was allotted a 300 sec session to find the target hole. The total time spent at each of the 12 holes was assessed. (In C and D, ***p < 0.05 het vs wt); δ δ δ P<0.001 het vs het PBA. N=6 mice for wt and 7 mice for het. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Turkey test. All data were recorded by an over-head camera and generated by ANY-Maze software.

Supplementary Figure 3. Postulated mechanisms of 4-phenylbutyrate in mitigating seizures

We propose that 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) can enhance the folding and expression of the wildtype α1β2γ2 receptors and reduce the mutant γ2(Q390X) protein aggregates inside endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This thus reduces ER stress and facilitate GABAA receptor protein membrane trafficking and function. Increased GABAA receptor function at the neuronal surface reduce brain excitability and mitigate seizures in the Gabrg2+/Q390X mice associated with Dravet syndrome.