Abstract

Increased fossil fuel usage and extreme climate change events have led to global increases in greenhouse gases and particulate matter with 99% of the world’s population now breathing polluted air that exceeds the World Health Organization’s recommended limits. Pregnant women and neonates with exposure to high levels of air pollutants are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes such as maternal hypertensive disorders, postpartum depression, placental abruption, low birth weight, preterm birth, infant mortality, and adverse lung and respiratory effects. While the exact mechanism by which air pollution exerts adverse health effects is unknown, oxidative stress as well as epigenetic and immune mechanisms are thought to play roles. Comprehensive, global efforts are urgently required to tackle the health challenges posed by air pollution through policies and action for reducing air pollution as well as finding ways to protect the health of vulnerable populations in the face of increasing air pollution.

INTRODUCTION

Air pollution, both indoor and outdoor, is increasingly recognized as a significant determinant of adverse health outcomes, particularly in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and neonates.1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 99% of the world’s population breathe air that exceeds WHO guideline limits.3 The burning of fossil fuels has increased concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), ozone (O3), and fluorinated gases.4 These heat-trapping GHGs increase global surface temperatures and frequency and intensity of wildfires and sand and dust storms, which further contribute to air pollution, particularly particulate matter (PM), a complex mixture of solids and aerosols that vary in size, shape, and chemical composition. PM includes metals, soil or dust particles, natural and synthetic chemicals, and allergens.5 Indoor sources of air pollution include use of biomass for cooking and heating (e.g., coal, dung, and firewood), allergens (mold spores, dust mites, animal dander), cigarette smoke, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from cleaning products.6 PM of concern are those with an aerodynamic diameter less than 10μm (PM10). which are small enough to enter the lungs and be deposited in the upper airways. Those with an aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5μm (PM2.5) are of even greater concern as they can enter the circulatory system through the alveoli of the lungs.3

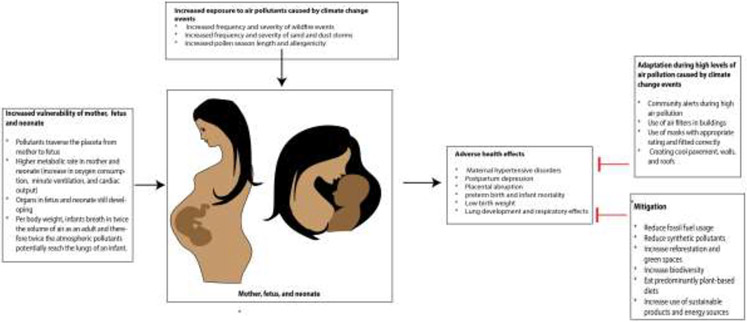

Here we review the increased vulnerability of pregnant women and neonates to air pollutants and the epidemiological evidence linking air pollution to adverse maternal and neonatal health effects such as maternal hypertensive disorders, postpartum depression, placental abruption, low birth weight, preterm birth, infant mortality, and adverse lung and respiratory effects. It is important to note that the impacts of high air pollution exposure are present also among people attempting conception with notable risk for longer time to conception,7 miscarriage,8-10 infertility,11 and reduced in-vitro fertility (IVF) treatment success.12 We also review current understanding of potential mechanisms linking air pollutants to adverse health effects. Finally, we discuss the mitigation and adaptation efforts that are urgently needed to protect the health of current and future vulnerable populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Increased use of fossil fuel has led to increases in greenhouse gases and pollen season length and frequency and intensity of wildfires, and sand and dust storms. Pregnant women, their fetuses and newborn infants are particularly vulnerable to adverse health effects such as maternal hypertensive disorders, postpartum depression, low birth weight, and preterm birth. In the face of worsening climate change adaptation measures (e.g., filters, masks) and mitigation measures (e.g., decreases in fossil fuel usage, increase in green spaces) are urgently needed.

INCREASED VULNERABILITY OF PREGNANT WOMEN AND NEONATES

Pregnant women and their newborn infants are particularly susceptible to the effects of air pollution due to their unique physiology. During pregnancy, physiological changes that occur include a 20% increase in oxygen consumption, a 40% to 50% increase in minute ventilation, and a 40% increase in cardiac output.13 These changes increase the amount of pollutants inhaled and circulated, thereby increasing exposure. The neonate is particularly vulnerable and may already have been adversely impacted by air pollutants during the gestational period. Studies have shown that pollutants traverse the placenta entering the fetal circulation. A study found that maternally inhaled carbonaceous air pollution particles can cross the placenta and then translocate into human fetal organs during gestation.14 Compounding gestational exposures, the lungs of neonates at birth are only partially formed resulting in vulnerability to air borne pollution. Neonates have a higher resting metabolic rate and therefore increased oxygen consumption, upper and lower airway resistance, and decreased lung volume and efficiency and endurance of respiratory muscles compared to older children and adults. Per body weight, infants breath in twice the volume of air as an adult and therefore twice the atmospheric pollutants potentially reach the lungs of an infant. Newborn infants have narrower airways; thus a minor narrowing of the airways in the neonate due to inflammation on exposure to ambient pollutants or respiratory infection has a disproportionate impact on airflow resistance.15-17

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF ADVERSE EFFECTS OF AIR POLLUTION ON MATERNAL AND NEONATAL HEALTH OUTCOMES

Air pollution has been shown to increase health risk during pregnancy and in the newborn. Major adverse maternal outcomes linked to air pollution include maternal hypertensive disorders and post-partum depression. In the neonate, maternal exposure to air pollutants has been associated with placental abruption, preterm birth, infant mortality, and low birth weight.

Maternal hypertensive disorders

Large nationwide studies as well as meta-analysis and systematic reviews have found associations between air pollutants and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDP) such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or eclampsia, which can have adverse effects on both maternal and infant health. A nationwide study in the USA of >5 million individuals used data from birth certificates between1999-2004 and data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) air quality networks and found that each 5 μg/m3 increment in maternal exposure to PM2.5 was associated with a 10% increase in the risk of HDP.17 In this study, HDP was defined as a diagnosis of elevated blood pressure for age, sex, and physiological condition during pregnancy. The study also found that exposure to PM2.5 attributed about 8.1% of burdens of HDP in the United States during 1999 to 2004.18 Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found similar significant positive associations between PM and HDP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 studies published between 1999 to August 2021 found that the risk of HDP (gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia) significantly increased per 5 mg/m3 increase in PM2.5 exposure (odds ration 1.06) during the first trimester and PM10 exposure during the entire period of pregnancy (odds ratio 1.04).19 Another meta-analysis of 33 cohort studies showed that PM10 increased the relative risk of gestational hypertension during the first trimester by 1.07 per 10 μg/m3 and PM2.5 increased the relative risk of HDP during the entire pregnancy by 1.18 per 5 μg/m3.20

Postpartum depression

Although the evidence is limited, a role for maternal exposure to ambient air pollutants and postpartum depression (PPD) is accumulating. A birth cohort of 509 mothers in Mexico City found that while PM2.5 was not associated with PPD at one month, a 5-μg/m3 increase in average PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy was associated with 1.59 times the risk of PPD at 6 months suggesting that the impacts of PM2.5 exposure may not occur until several months post-partum.21 Similarly, a study involving 10,209 expecting mothers from five Chinese hospitals found that exposure to 10 μg/m3 increases in PM10 or NO2 during the entire pregnancy period was associated with an adjusted PPD odds risk of 1.47 and 1.63, respectively, at 6 weeks postpartum.22 In a low-income cohort consisting of primarily Hispanic/Latina women in urban Los Angeles, greater than a two-fold increased PPD rate at 12 months postpartum was associated with second-trimester NO2 exposure (OR = 2.63) and average NO2 (OR = 2.04).23 A systematic review and meta-analysis found that exposure to PM10 within the second trimester was significantly associated with a 1.26 increased odds ratio of PPD.24

Placental abruption

Placental abruption has also been associated with maternal exposure to air pollutants. This is likely due to increased inflammation, oxidative stress, and hemostasis caused by air pollution exposure. A study examined the associations between exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 and the risk of abruptions of acute onset. 24 Between 2008-2014 in New York City (2008-2014) 1,190 abruption cases were identified. The authors found that per 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5, the odds ratio of abruption increased by 1.19, 1.21, and1.17 on lag days 3-5, respectively. Similarly, the odds of abruption increased per 5 ppb increase in NO2 exposure on lag days 3-5 by 1.16, 1.19, and 1.16, respectively.25 In this context, 'lag days' refers to the specific days following exposure, allowing to evaluate the temporal relationship between air pollutant exposure and the outcomes. Another prospective cohort study of 685,908 pregnancies in New York evaluated the associations of maternal exposure to PM2.5 at concentrations of <12 μg/m3, 12-14 μg/m3, and ≥15 μg/m3 and NO2 at concentrations of <26 parts per billion (ppb), 26-29 ppb, and ≥30 ppb with placental abruption. 25 The study found that women exposed to higher PM2.5 concentrations (≥15 μg/m3) in the third trimester had a higher rate of abruption (hazard ratio (HR) of 1.68, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.41, 2.00) than those exposed to lower concentrations (< 12 μg/m3). Similarly, higher concentrations of NO2 of 26-29 ppb (HR=1.1) and ≥30 ppb (HR=1.06, 95% CI: 0.96, 1.24) in the first trimester had higher rates of abruption than those exposed to concentrations less than 26 ppb.26

Preterm birth and infant mortality

The effects of air pollution on infant mortality are felt all around the globe. According to the 2020 State of Global Air, in 2019, 476,000 infants died in their first month of life from health effects associated with air pollution exposure.27_In India, a study used nationally representative anthropometric data from India's 2015-2016 Demographic and Health Survey of approximately 259,627 children under five across 640 districts of India. Satellite-based PM2.5 concentrations were determined during the month of birth of each child. The study found that for every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 exposure during trimester 3, odds ratio for infant mortality was 1.016 (95% CI: 1.003, 1.030) after controlling for child, mother and household factors including trends in time and seasonality.28 While the effect sizes may seem modest, it's crucial to recognize their potential impact in populous regions. An increase of 10 μg/m3 in PM2.5 could lead to a 1.63% rise in infant mortality. In the context of India, where millions of births occur annually, even this seemingly small percentage can translate into a significant number of excess deaths. In China, a study at the prefecture-city level between 2004–2015 found that an increase in the annual average PM2.5 concentration of 10 μg/m3 resulted in an 1.63% increase in infant mortality.29 In the United States, there have been great strides in reducing air pollution.30 These findings underscore the importance of mitigating air pollution and highlights the need for immediate interventions that are tailored to the unique challenges faced by regions with high pollution levels.

Furthermore, a study evaluated the effect of the regional GHG initiative, which is the first mandatory cap-and-trade program designed to reduce GHG emissions in the USA, on infant mortality six years before and after its implementation. States that participated in this initiative have seen considerable decreases in CO2 emissions. The study found a significant reduction in overall neonatal mortality rates (a reduction of 0.41/1000 live births).31 Analysis of birth data between 2015–2017 in Italy found that PM2.5, O3 and aeroallergens increased the risk of preterm birth by 1.023 per 10 μg/m3, 1.025 per 10 μg/m3, and 1.01 per 10 grains/m3, respectively in the week before delivery.32 Preterm birth is one of the main causes of infant mortality.

Low Birth Weight

Low birth weight (LBW) is an important risk factor for future co-morbidities for the infant. A systematic review of 52 studies found that that for every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 exposure in the 3rd trimester or the entire pregnancy, there was a 6.57g or 8.65g decrease in birth weight, respectively, supporting the existence of an inverse association between prenatal PM10 exposure and LBW.33 Another meta-analysis of 54 studies investigated the association between LBW and maternal exposure to six major ambient air pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, NO2, CO, SO2, and O3 and found that maternal exposure to all these 6 air pollutants were generally positively associated with LBW, with effects varying depending on trimester. 33 For instance, NO2 and CO exposure in the first trimester, PM2.5 exposure in the third trimester, and PM10 exposure in the second trimester were positively associated with LBW. The study found that the pooled effect of increased PM2.5, PM10, NO2, CO, SO2, and O3 exposure on LBW were 1.08 per 10 μg/m3, 1.05 per 10 μg/m3, 1.03 per 10 ppb increase, 1.01 per 100 ppb increase, 1.13 per 10 μg/m3, and 1.05 per 10 μg/m3, respectively.34 While the pooled effect sizes may appear subtle, these values signify substantial implications for public health since, for example, an increase in the odds of LBW with PM2.5 exposure denotes up to a 8% higher chance of LBW in infants.

In addition, pooled estimates from a meta-regression and analysis of attributable global burden for 204 countries and territories, indicated 22 grams LBW, 11% greater risk of low birth weight and 12% greater risk of preterm birth per 10 μg/m3 increment in ambient PM2.5. The study also estimated that about a third of the total PM2.5 burden for LBW and preterm birth could be attributable to ambient exposure, with household air pollution dominating in lower-resource country settings.35 In densely populated regions with high levels of pollution, these percentage increases can translate into a considerable number of babies born with LBW annually.

Lung development and respiratory effects

Airway epithelial cells form a frontline defense to infectious pathogens and other environmental pollutants. Air pollutants, including biological as well as gaseous and particulate pollutants, on entering the lungs mediate epithelial barrier dysfunction and adverse respiratory health by disrupting tight junctions.36 Cellular and animal studies have provided compelling evidence of the adverse impacts of pollutants in utero on the developing lungs.37-39 This is supported by epidemiological studies that have associated air pollution with impairments in lung function. A study evaluated the effect of prenatal exposure to PM2.5 (monitored by personal sensors) in 391 mother-child pairs. The study found that a 10 μg/m3 increase in maternal PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy was associated with a 2.3% decrease in the functional residual capacity of the newborn.40 In a large US cohort that included 12 clinical sites and 19 hospitals, air pollution was associated with lung disease in infants, particularly transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN), asphyxia, and respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in addition to lower lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) later in life. RDS, characterized by difficulty breathing due to neonates’ lungs lacking sufficient surfactants, has been linked to elevated NOx and O3 exposure.41 TTN, which is the fast, labored breathing of neonates as a result of fluid accumulation in their lungs, increased by nearly 10% for each interquartile range (IQR) increase in exposure to PM10 during the 3 months' preconception and over trimester one. Asphyxia caused by a lack of respiratory effort by the neonate leading to oxygen deprivation, was reported to increase significantly by up to 73% for each IQR increase in O3 exposure during all stages of pregnancy. Furthermore, the risk of asphyxia increased by 48% following exposure to PM2.5 during the first trimester, and by 84% when exposed to PM2.5 throughout the entire duration of pregnancy.

Other studies have looked at long-term effects. A study conducted in Poland found that exposure to ambient levels of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) during pregnancy was associated with a 4.8-fold increased risk of cough, 3.8-fold increased risk of wheezing without a cold, and an 82% increased risk of runny or stuffy-nose during the newborn’s first year of life.15 Similarly, in a South African birth cohort (n=270), pre- and post-natal exposure to PM10 were associated with reduced lung function at 6 weeks and 1 year and lower respiratory tract infection in the first year of life. There was a higher susceptibility of reduced lung function for infants with an adverse genetic predisposition for asthma that also depended on the infant's ancestry, as those with more asthma-related risk alleles were significantly more susceptible to PM10-associated reduced lung function.42 In a Hong Kong birth cohort from 1997 that followed 2,942 children, it was found that early exposure to NO2 in utero, infancy, and toddlerhood could result in long-term adverse health outcomes at 17.5 years of age. More specifically, NO2 exposure during these time periods were separately associated with lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) , and forced expiratory flow at 25%–75% of the pulmonary volume (FEF25%-75%).43 Not only do these findings suggest that perinatal exposure to airborne PAHs are potentially linked to poor respiratory health, but they also could result in acute and chronic problems related to lung development and increase risk of respiratory effects such as asthma and other respiratory illnesses. Another longitudinal study that followed children in the UK from pregnancy to 15 years of age could not identify clear evidence of a sensitive exposure period during pregnancy for traffic-related PM10, but associations still suggested that overall, exposure during pregnancy could lead to minor but significant reductions in lung function at 8 years of age.44 In a study of 700 mother-infant pairs, higher prenatal air pollution exposure with NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 was associated with an altered nasal mucosal immune profile at 4 weeks, conferring an increased odds of 2.68 for allergic sensitization, 2.63 for allergic rhinitis at age 6 years, and with an altered immune profile in blood at age 6 months conferring increased odds of 1.80 for asthma at age 6 years.45

The dangers air pollution poses to maternal and pediatric health are exacerbated in low- and middle-income countries. A recent literature review reported that in sub-Saharan Africa, where more than 4 out of every 5 children live in households reliant on unclean energy sources, biomass fuel exposures both increase the risk of acute respiratory tract infections and presence of pathogenic bacteria in the upper respiratory tract. In a longitudinal rural Ghanian cohort from birth to 30 days, multivariable linear regression models showed that average prenatal CO exposure from indoor air pollution was associated with reduced time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time, increased respiratory rate, and increased minute ventilation. These adverse effects on infant’s lung function may increase risk for pneumonia in the first year of life.46 Masekela and Vanker also found that despite limited data showing associations between pediatric asthma diagnoses and air pollution, airway hyper-responsiveness and lower lung function have been consistently found in children in Sub-Saharan Africa with higher risk of exposure to ambient pollutants.47

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS

The major mechanisms that have been proposed to mediate adverse maternal and neonatal health by air pollutants include immune dysfunction with increases in Th2 inflammatory and allergic pathways, epigenetic modifications, and oxidative stress.45,48 Here we briefly review these mechanisms.

Immune Mechanisms

Our understanding of the mechanism by which immune dysfunction leads to adverse maternal and neonatal health outcomes is still very rudimentary, but research aided by a number of technological advancements such as flow cytometry and cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF), is enabling characterization of immune phenotypes and function. allowing identification of all major cell lineages as well as additional marker customization. Further, assays to measure immune function often use the same platforms of flow or mass cytometry, but with in vitro stimulation, followed by readout of intracellular cytokines49,50 or phosphoepitopes.51,52 Such assays can use mitogen stimulation (e.g., PMA+ionomycin) to broadly assess immune competence, a concept that has been proposed for assessing cancer patients prior to immunotherapy53 and could be productively applied to the study of neonatal health as well.

The placenta is the site where multiple immune mechanisms work to enable immune tolerance, 54 dysfunction of which has been associated with pregnancy complications, such as spontaneous abortion55 and preeclampsia.56 The placenta consists of fetal trophoblasts interlaced with maternal cells that form the decidua. One way that fetal trophoblasts evade the maternal immune response is via differential HLA expression. Extravillous trophoblasts, the fetal trophoblasts that anchor into the uterine mucosa, lack HLA-A and HLA-B expression, evading alloreactive maternal T cells.57 Extravillous trophoblasts also express HLA-C, HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G, which inhibit maternal natural killer (NK)-cell mediated cytotoxicity and induce tolerogenic dendritic cells.57,58 High traffic-related NO2 exposure has been shown to affect the number of NK cells in fetal cord blood.59 Additionally, increased air pollutant exposure in pregnancy alters the types of dendritic cells present in fetal cord blood.60 Combined, these changes could impact the tolerogenicity of this delicate interface.

Other inhibitor molecules also help induce immune tolerance in a normal pregnancy. PD-L1, for example, is highly expressed on all trophoblast cells and, via binding to the PD-1 receptor, can inhibit antigen-induced T-cell activation in maternal cells.61,62 Sialylated glycans on fetal antigens have also been implicated to suppress maternal B cells via CD22-LYN inhibitory signaling.63 Crosstalk between decidual NK cells and decidual CD14+ cells produce the enzyme IDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) which catalyzes tryptophan, essential for T cell proliferation, into catabolites such as L-kynurenine that can inhibit immune cell function.64,65 Additionally, in a typical pregnancy, there is a shift from a Th1 to a Th2-dominant environment. High levels of air pollutant exposure during pregnancy have been associated with changes in T-cell polarization in fetal cord blood, which could impact these tolerogenic mechanisms.59,60 Cytokine dysregulation and differential cytokine methylation play an important role in T-cell differentiation and are affected by air pollution exposure. Specifically, increased ambient air pollution exposure in pregnancy has been shown to affect levels of CRP, IL-4, IL-6, and TNFa in maternal and fetal samples.66,67 A recent study showing that increases in ambient air pollutants during pregnancy are linked to increases in methylation of IL4, IL10, and IFNγ offers insights into potential mechanisms behind the cytokine dysregulation and consequential differential T-cell polarization.68

Also induced during pregnancy are regulatory T cells (Tregs), which are believed to play a key role in inducing antigen-specific tolerance.69 HLA-G+ extravillous trophoblasts have been observed to interact with decidual T cells to induce Tregs.57 Interactions between decidual NK cells and decidual CD14+ cells have also been shown to induce Tregs.65 Finally, during gestation, there is a persistent transfer of cells from infant to mother known as fetal cell microchimerism. This is hypothesized to also contribute to the continuation of Treg differentiation during gestation, though the precise mechanism is not yet known.70 Importantly, there are fewer Tregs present in the fetal cord blood from infants whose mothers were exposed to higher levels of traffic-related nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter, which could impair this important immune tolerance mechanism.59

Genetic and Epigenetic Mechanisms

Air pollution can directly influence genetic material by inducing DNA damage as well as through epigenetic alterations. In utero exposure to air pollutants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), PM, and heavy metals can cause DNA adduct formation, strand breaks, and oxidative DNA damage.71 Studies have linked these genotoxic effects to an increased risk of low birth weight, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction, among other adverse neonatal outcomes.72 A retrospective study of placenta of 814 pairs of mothers and neonates found that increased exposure to PM2·5 and black carbon was significantly associated with increases in DNA mutation. The Alu gene is the most abundant gene in the human genome. Alu methylation is correlated with the overall level of DNA methylation73 and therefore, alu mutation rate was used as a measure of the overall DNA mutation rate. Further, this occurred in concert with DNA methylation in the promoter genes of key DNA repair and tumor suppressor genes, suggesting that exposure to air pollution can induce changes to fetal and neonatal DNA repair capacity.74 Another study compared the effect of air pollution on oxidative DNA damage in mothers and their newborns from two different locations, one with clean air and one with high levels of air pollution. They measured urinary 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydro-2-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) as a marker of DNA oxidation. The study found that PM2.5 concentrations to be a significant predictor for 8-oxodG excretion in mothers and their newborns from the region of high pollution.75 Furthermore, some genetic polymorphisms may modify the individual susceptibility to the adverse effects of air pollution. Certain variants, particularly in genes related to the detoxification pathways and oxidative stress responses, appear to exacerbate the harmful impacts of prenatal exposure to air pollutants on neonatal health.76

Epigenetic alterations provide the flexibility to alter gene expression by opening and closing transcription sites in response to changing environmental cues. As epigenetic changes are modulated by environmental exposures they act as an interface between genes and environment. Epigenetic changes include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA mechanisms. Most epigenetic studies in humans have focused on DNA methylation and this mechanism is the best studied. Animal studies suggest that air pollutants are associated with histone modifications.77 A few studies in humans have evaluated the effects of air pollution on histone acetylation, but to our knowledge there have been no human studies conducted on pregnant women or their newborn infants. One of the main mechanisms by which PM exposure prompts specific chromatin alterations is through induced oxidative stress. While many studies suggest that PM acts directly on acetylation status through oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species, which disrupts the balance between the acetylated/deacetylated status, some compounds found in PM, such as nickel causes selective inhibition of H3K9 demethylase by replacing the iron from the catalytic site.78,79 Limited evidence suggests that air pollution exposure may affect non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs). Micro-RNA (miRNA) regulates gene expression either by mRNA cleavage or by translational repression via RNA induced silencing complex (RISC).80 These miRNAs are crucial regulators of gene expression, and their dysregulation due to environmental exposures could contribute to adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.81 Welders are often exposed to cadmium fumes and a correlation analysis revealed a positive association of miR-222 and miR-146a with blood cadmium level.82 These miRNAs are crucial regulators of gene expression, and their dysregulation due to environmental exposures could contribute to adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.81 In Cd-exposed workers, correlation analysis revealed a positive association of miR-222 and miR-146a with blood cadmium level.82 Similarly, another study found that miR-155 and miR-221 were significantly upregulated on exposure to lead.80

Most studies have focused on DNA methylation, which regulates gene expression through the disruption of transcription factor binding, chromatin structure, and subsequent gene silencing. Both targeted gene-specific approaches to methylation as well as epigenome-wide, array-based approaches have been used. Exposure studies that assess methylation effects in a trimester-specific approach tend to find larger effects during 1st trimester exposure.83 Prenatal exposure to air pollutants have been shown to alter the DNA methylation status in genes associated with growth, development, and immune function, which can potentially influence fetal development and neonatal health.84A number of studies have found an association between air pollution exposure in utero and neurodevelopmental delays85 or intelligence in the offspring. A systematic review of observational studies concluded that exposure to PAHs during pregnancy has an adverse impact on childhood IQ.86 An epigenome-wide meta-analysis identified several differentially methylated CpGs and DMRs associated with prenatal PM exposure newborns, some of which have been associated with lung function and asthma.87

Oxidative Stress

Air pollutants that are potent oxidants or are able to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) include PM, O3, nitrogen oxides, and transition metals. Oxidative stress occurs when the production of ROS by pollutants exceeds the body’s natural antioxidant capacity. Free radicals produced can damage to structural and functional molecules, organelles, and tissues including DNA, RNA, lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates. However, the exact molecular mechanisms remain elusive. ROS is an essential factor in performing the function of cells, but overproduction of ROS can have detrimental effects on cells through redox sensitive transcription factors such as NF-κB, activator protein 1 (AP-1) and CAATT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP).88 NF-κB can increase the production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecule.89 ROS has also been shown to upregulate NLRP3, which forms an inflammasome after activation and participates in immune regulation. Activation of these inflammasomes leads to the processing and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-18, as well as to an inflammatory form of cell death termed pyroptosis.90

ADAPTATION AND MITIGATION

Air pollution exposure represents a substantial health risk to pregnant women and neonates. Although the mechanism underlying these health effects is incompletely understood, urgent action is needed to mitigate these effects through reduction of air pollutants and evidence-based strategies to reduce exposure to safeguard the health of current and future generations. Adaptation refers to minimizing exposure to pollutants while mitigation refers to reduction of pollutants.

It is well recognized that socioeconomic status, race, and geography often determine exposure to air pollution. Low-income communities, racial and ethnic minorities, and residents of industrially burdened regions often face higher exposure levels to harmful pollutants.91 These circumstances create an environmental justice issue where the burdens of pollution are not equally shared. As a result, these populations, already strained by social and economic challenges, bear the brunt of adverse health effects associated with air pollution, including its impacts on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Therefore, efforts to address air pollution must also aim to rectify these disparities, focusing on comprehensive solutions that address both environmental and social determinants of health.

The uneven distribution of air pollution exacerbates health inequities. Pregnant women in disproportionately affected communities are at higher risk for complications such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and preeclampsia.92 Moreover, neonates in these communities are more likely to suffer from health issues such as neurodevelopmental disorders and respiratory problems, which can have long-term implications for their quality of life.93 Thus, understanding and mitigating the health impacts of air pollution is not just a medical issue, but also a matter of social justice and equity. Addressing these health disparities requires not only tackling the environmental causes but also confronting the systemic issues that perpetuate these inequities.

Adaptation

Individuals need to minimize exposure to air pollutants and robust air quality monitoring and alert systems can assist with this. Emerging technologies in air measurement, such as cloud-based, wearable, and low-cost methods, present the potential for integrative and affordable systems for continuous air monitoring. Recent studies have exhibited how front-end sensors, which may be stationary, portable, or wearable, can successfully feed into the cloud-side backend via Bluetooth. There, an air quality analytics multi-dimensional sensor engine can learn and build air-quality models from sensor data, immediately re-calibrating sensors and quantifying ambient pollutants.94,95

On days with high air pollution, alerts can inform the community and encourage them to stay indoors or use masks when outdoors. Education on mask ratings and proper fit can minimize exposure. Indoor air pollution is also a concern as individuals spend a significant amount of time indoors. It is therefore important to raise awareness about the dangers of indoor air pollution and promoting use of adequate household ventilation, transitioning to cleaner fuels for cooking and heating, and not vaping or smoking cigarettes.96,97 One effective approach to mitigate indoor air pollution is through the use of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems equipped with appropriate air filters. The Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) rating of these filters can serve as an important indicator of their ability to remove pollutants from indoor air. By monitoring the MERV rating of filters in HVAC systems, it is possible to ensure that they are functioning optimally and removing as many pollutants as possible from the indoor air. In addition, HVAC systems can also be used as a means to distribute air quality monitoring sensors and collect real-time air quality data. This information can be used to better understand the sources and levels of indoor air pollution and inform interventions to improve indoor air quality. As such, the combination of MERV ratings and HVAC systems can play an important role in air pollution monitoring and management.

Mitigation

While mitigation efforts can be undertaken at an individual level, larger collaborative efforts at the community, national, and global levels are needed to significantly lower air pollutants. This includes transition to clear energy and lowering overall energy consumption by increased weatherization of buildings, encouraging use of alternative modes of transport such as biking, walking, or use of public transport, promoting use of electric stoves rather than gas for cooking, increasing biodiversity and green spaces, and adoption of diets that are predominantly plant based with limited consumption of red meat.

A 2021 report by the Medical Society Consortium on Climate & Health, Wisconsin Health Professionals for Climate Action, and the National Defense Research Council (NRDC) details the health care costs associated with air pollution and climate change related events, tops $820 billion a year. Health costs include those related to exposure to air pollutants, vector borne infectious diseases, extreme weather events (wildfires, hurricanes, and heat waves).98

In the US, the Clean Air Act of 1963 was the first federal legislation regarding air pollution control and has been amended a number of times to further set, monitor, and limit vehicular and industrial emissions.99 Air pollution reductions that have occurred as a result of the regional GHG initiative (Northeastern states in the US)_estimate substantial health benefits for children’s health outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, asthma, and autism spectrum disorder with an associated avoided cost estimate ranging from $191 to $350 million.100 Another study used EPA’s Co-Benefits Risk Assessment screening tool and estimated that roughly 50,000 premature deaths could be prevented per year saving approximately $608 billion in the health care costs and loss of life associated with PM2.5. Of all the sectors, removal of emissions from on-road vehicles made the single biggest difference in terms of avoided premature deaths and monetized health benefits.101 The 2021 Infrastructure Reduction Act also has a number of incentives to develop low-carbon energy systems.

An important milestone globally was the Paris Agreement in 2015 where a number of nations pledged to limit global warming to well below 2°C, but preferably to 1.5°C in 2100, compared with pre-industrial levels, however, in 2023, it is evident that the actions taken so far by these countries are inadequate to meet these goals.102

There is also recognition that planetary health and human health is interconnected and there are efforts such as that by One Health to emphasize this connection. One Health is a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach working at the local, regional, national, and global levels with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment.103

While there is some political action and policies being implemented to decrease air pollution, current efforts are inadequate to safeguard the health of future generations. It is imperative that each and every citizen take responsibility and action to reduce air pollution.

CONCLUSION

Air pollution, exacerbated by climate change, is an increasingly recognized health risk, its detrimental impacts extend to some of our most vulnerable populations, notably pregnant women and neonates. The epidemiological evidence underscores the significant associations between air pollution exposure and various adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, including HDP, postpartum depression, infant mortality, low birth weight, preterm birth, and effects on lung development and respiratory health.

Our understanding of the underlying mechanisms by which air pollution affects pregnancy and neonatal outcomes continues to evolve. Inclusion of the physiology of gametogenesis, conception, pregnancy establishment, and neonatal development will be critical to identify and prevent air-pollution associated risk in pregnancy.104 Insights into genetic and epigenetic alterations, immune tolerance during pregnancy, oxidative stress, changes in immune cell phenotypes and functions, and newborn infection rates offer new perspectives on the complex pathways linking air pollution exposure and adverse health outcomes.

The distinction between outdoor and indoor air pollution exposure is critical, given their unique sources, health impacts, and strategies for mitigation. Continuous air pollution monitoring, behavioral adaptations, and technological solutions like masks and air purifiers play key roles in managing exposure to air pollutants.

However, the burden of air pollution is not borne equally. Environmental justice concerns highlight the disproportionate exposure to and impacts of air pollution in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities and industrially burdened regions. Understanding and addressing the environmental justice implications of air pollution is critical to reducing health disparities and promoting equitable pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Addressing these disparities requires targeted policies and interventions to reduce pollution exposure and increase access to adaptation resources in these communities. Access to resources for adapting to and mitigating the effects of air pollution is often limited in disadvantaged communities. Factors such as housing conditions, lack of access to healthcare, and limited political influence hinder these communities' ability to reduce exposure to pollutants and manage their health effects. Air pollution should be recognized not merely as an environmental issue but also as a social justice concern that requires an integrative and inclusive approach to tackle effectively.

In conclusion, the impacts of air pollution on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes underscore the urgent need to respond with a multi-faceted approach encompassing robust research, policy change, technological innovation, and environmental justice initiatives. A comprehensive, global effort is required to tackle the health challenges posed by air pollution, protect our vulnerable populations, and ultimately, foster healthier and more sustainable communities.

Funding

NIEHS grant R01ES032253 (KN) and R38 HL 143615 (KK)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COI

Dr.Nadeau reports grants from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), and Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE); Stock options from IgGenix, Seed Health, ClostraBio, Cour, Alladapt; Advisor at Cour Pharma; Consultant for Excellergy, Red tree ventures, Before Brands, Alladapt, Cour, Latitude, Regeneron, and IgGenix; Co-founder of Before Brands, Alladapt, Latitude, and IgGenix; National Scientific Committee member at Immune Tolerance Network (ITN), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinical research centers; patents include, “Mixed allergen com-position and methods for using the same,” “Granulocyte-based methods for detecting and monitoring immune system disorders,” and “Methods and Assays for Detecting and Quantifying Pure Subpopulations of White Blood Cells in Immune System Disorders”. All other authors indicate no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Girardi G & Bremer AA Effects of Climate and Environmental Changes on Women's Reproductive Health. Journal of Women's Health 31, 755–757 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderko L, Chalupka S, Du M & Hauptman M Climate Changes Reproductive and Children’s Health: A Review of Risks, Exposures, and Impacts. Pediatric Research 87, 414–419 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Billions of People Still Breathe Unhealthy Air: New Who Data, <https://www.who.int/news/item/04-04-2022-billions-of-people-still-breathe-unhealthy-air-new-who-data> (2023).

- 4.EPA. Overview of Greenhouse Gases, <https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases> (2023).

- 5.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Particulate Matter (Pm) Basics, <https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics#PM> (2023).

- 6.United States environmental Protection Agency. Introduction to Indoor Air Quality, <https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/introduction-indoor-air-quality> (2023).

- 7.Wesselink AK et al. Air Pollution and Fecundability: Results from a Danish Preconception Cohort Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 36, 57–67 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue T. et al. Estimation of Stillbirths Attributable to Ambient Fine Particles in 137 Countries. Nat Commun 13, 6950 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahalingaiah S, Missmer SE, Cheng JJ, Chavarro J, Laden F & Hart JE Perimenarchal Air Pollution Exposure and Menstrual Disorders. Hum Reprod 33, 512–519 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaskins AJ et al. Air Pollution Exposure and Risk of Spontaneous Abortion in the Nurses' Health Study Ii. Hum Reprod 34, 1809–1817 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahalingaiah S. et al. Adult Air Pollution Exposure and Risk of Infertility in the Nurses' Health Study Ii. Hum Reprod 31, 638–647 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conforti A. et al. Air Pollution and Female Fertility: A Systematic Review of Literature. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 16, 117 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan W & Zlatnik MG Climate Change and Pregnancy: Risks, Mitigation, Adaptation, and Resilience. Obstet Gynecol Surv 78, 223–236 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bongaerts E. et al. Maternal Exposure to Ambient Black Carbon Particles and Their Presence in Maternal and Fetal Circulation and Organs: An Analysis of Two Independent Population-Based Observational Studies. Lancet Planet Health 6, e804–e811 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvi S. Health Effects of Ambient Air Pollution in Children. Paediatr Respir Rev 8, 275–280 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijayasekaran S. Pediatric Airway Pathology. Front Pediatr 8, 246 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trachsel D, Erb TO, Hammer J & von Ungern-Sternberg BS Developmental Respiratory Physiology. Paediatr Anaesth 32, 108–117 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue T, Zhu T, Lin W & Talbott EO Association between Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy and Particulate Matter in the Contiguous United States, 1999-2004. Hypertension 72, 77–84 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao L. et al. Particulate Matter and Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health 200, 22–32 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai W. et al. Association between Ambient Air Pollution and Pregnancy Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Environ Res 185, 109471 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niedzwiecki MM et al. Particulate Air Pollution Exposure During Pregnancy and Postpartum Depression Symptoms in Women in Mexico City. Environ Int 134, 105325 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan CC et al. Association between Prenatal Exposure to Ambient Air Pollutants and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms: A Multi-City Cohort Study. Environ Res 209, 112786 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastain TM et al. Prenatal Ambient Air Pollution and Maternal Depression at 12 Months Postpartum in the Madres Pregnancy Cohort. Environ Health 20, 121 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pourhoseini SA, Akbary A, Mahmoudi H, Akbari M & Heydari ST Association between Prenatal Period Exposure to Ambient Air Pollutants and Development of Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Health Res, 1–11 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ananth CV et al. Exposures to Air Pollution and Risk of Acute-Onset Placental Abruption: A Case-Crossover Study. Epidemiology 29, 631–638 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y. et al. Air Pollution and Risk of Placental Abruption: A Study of Births in New York City, 2008-2014. Am J Epidemiol 190, 1021–1033 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.State of Global Air. Impacts on Newborns: Air Pollution’s Youngest Victims, <https://www.stateofglobalair.org/health/newborns> (2020).

- 28.deSouza PN, Dey S, Mwenda KM, Kim R, Subramanian SV & Kinney PL Robust Relationship between Ambient Air Pollution and Infant Mortality in India. Sci Total Environ 815, 152755 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Shi T & Chen H Air Pollution and Infant Mortality: Evidence from China. Econ Hum Biol 49, 101229 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Air Pollution: Current and Future Challenges, <https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/air-pollution-current-and-future-challenges#limiting> (2023).

- 31.Lee J & Park T Impacts of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (Rggi) on Infant Mortality: A Quasi-Experimental Study in the USA, 2003-2014. BMJ Open 9, e024735 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cocchi E. et al. Air Pollution and Aeroallergens as Possible Triggers in Preterm Birth Delivery. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uwak I. et al. Application of the Navigation Guide Systematic Review Methodology to Evaluate Prenatal Exposure to Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Infant Birth Weight. Environ Int 148, 106378 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C. et al. Maternal Exposure to Air Pollution and the Risk of Low Birth Weight: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Environ Res 190, 109970 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh R, Causey K, Burkart K, Wozniak S, Cohen A & Brauer M Ambient and Household Pm2.5 Pollution and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes: A Meta-Regression and Analysis of Attributable Global Burden for 204 Countries and Territories. PLoS Med 18, e1003718 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee PH, Park S, Lee YG, Choi SM, An MH & Jang AS The Impact of Environmental Pollutants on Barrier Dysfunction in Respiratory Disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 13, 850–862 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Barros Mendes Lopes T. et al. Pre- and Postnatal Exposure of Mice to Concentrated Urban Pm(2.5) Decreases the Number of Alveoli and Leads to Altered Lung function at an Early Stage of Life. Environ Pollut 241, 511–520 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh N, Nagar E & Arora N Diesel Exhaust Exposure Impairs Recovery of Lung Epithelial and Cellular Damage in Murine Model. Mol Immunol 158, 1–9 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rychlik KA et al. In Utero Ultrafine Particulate Matter Exposure Causes Offspring Pulmonary Immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 3443–3448 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lepeule J. et al. Pre-Natal Exposure to No(2) and Pm(2.5) and Newborn Lung Function: An Approach Based on Repeated Personal Exposure Measurements. Environ Res 226, 115656 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seeni I, Ha S, Nobles C, Liu D, Sherman S & Mendola P Air Pollution Exposure During Pregnancy: Maternal Asthma and Neonatal Respiratory Outcomes. Ann Epidemiol 28, 612–618.e614 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hüls A. et al. Genetic Susceptibility to Asthma Increases the Vulnerability to Indoor Air Pollution. Eur Respir J 55 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He B. et al. The Association of Early-Life Exposure to Air Pollution with Lung Function at ~17.5 Years in the "Children of 1997" Hong Kong Chinese Birth Cohort. Environ Int 123, 444–450 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai Y. et al. Prenatal, Early-Life, and Childhood Exposure to Air Pollution and Lung Function: The Alspac Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 202, 112–123 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tingskov Pedersen CE et al. Prenatal Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution Is Associated with Early Life Immune Perturbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 151, 212–221 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee AG et al. Prenatal Household Air Pollution Is Associated with Impaired Infant Lung Function with Sex-Specific Effects. Evidence from Graphs, a Cluster Randomized Cookstove Intervention Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199, 738–746 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masekela R & Vanker A Lung Health in Children in Sub-Saharan Africa: Addressing the Need for Cleaner Air. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yadav A & Pacheco SE Prebirth Effects of Climate Change on Children's Respiratory Health. Curr Opin Pediatr 35, 344–349 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lovelace P & Maecker HT Multiparameter Intracellular Cytokine Staining. Methods Mol Biol 1678, 151–166 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subrahmanyam PB & Maecker HT Cytof Measurement of Immunocompetence across Major Immune Cell Types. Curr Protoc Cytom 82, 9.54.51–59.54.12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies R, Vogelsang P, Jonsson R & Appel S An Optimized Multiplex Flow Cytometry Protocol for the Analysis of Intracellular Signaling in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. J Immunol Methods 436, 58–63 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leelatian N, Diggins KE & Irish JM Characterizing Phenotypes and Signaling Networks of Single Human Cells by Mass Cytometry. Methods Mol Biol 1346, 99–113 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang S, Kohrt H & Maecker HT Monitoring the Immune Competence of Cancer Patients to Predict Outcome. Cancer Immunol Immunother 63, 713–719 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Genebrier S & Tarte K The Flawless Immune Tolerance of Pregnancy. Joint Bone Spine 88, 105205 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zenclussen AC et al. Abnormal T-Cell Reactivity against Paternal Antigens in Spontaneous Abortion: Adoptive Transfer of Pregnancy-Induced Cd4+Cd25+ T Regulatory Cells Prevents Fetal Rejection in a Murine Abortion Model. Am J Pathol 166, 811–822 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu P. et al. Altered Decidual Dc-Sign+ Antigen-Presenting Cells and Impaired Regulatory T-Cell Induction in Preeclampsia. Am J Pathol 181, 2149–2160 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tilburgs T. et al. Fetal-Maternal Hla-C Mismatch Is Associated with Decidual T Cell Activation and Induction of Functional T Regulatory Cells. J Reprod Immunol 82, 148–157 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ristich V, Liang S, Zhang W, Wu J & Horuzsko A Tolerization of Dendritic Cells by Hla-G. Eur J Immunol 35, 1133–1142 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.García-Serna AM et al. Air Pollution from Traffic During Pregnancy Impairs Newborn's Cord Blood Immune Cells: The Nela Cohort. Environ Res 198, 110468 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martins Costa Gomes G. et al. Environmental Air Pollutants Inhaled During Pregnancy Are Associated with Altered Cord Blood Immune Cell Profiles. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petroff MG, Kharatyan E, Torry DS & Holets L The Immunomodulatory Proteins B7-Dc, B7-H2, and B7-H3 Are Differentially Expressed across Gestation in the Human Placenta. Am J Pathol 167, 465–473 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veras E, Kurman RJ, Wang TL & Shih IM Pd-L1 Expression in Human Placentas and Gestational Trophoblastic Diseases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 36, 146–153 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizzuto G. et al. Establishment of Fetomaternal Tolerance through Glycan-Mediated B cell Suppression. Nature 603, 497–502 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fallarino F. et al. T Cell Apoptosis by Tryptophan Catabolism. Cell Death Differ 9, 1069–1077 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vacca P. et al. Crosstalk between Decidual Nk and Cd14+ Myelomonocytic Cells Results in Induction of Tregs and Immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 11918–11923 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Melo JO et al. Inhalation of Fine Particulate Matter During Pregnancy Increased Il-4 Cytokine Levels in the Fetal Portion of the Placenta. Toxicol Lett 232, 475–480 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedman C. et al. Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution During Pregnancy and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood: The Healthy Start Study. Environ Res 197, 111165 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aguilera J. et al. Increases in Ambient Air Pollutants During Pregnancy Are Linked to Increases in Methylation of Il4,Il10, and Ifnγ. Clin Epigenetics 14, 40 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heikkinen J, Möttönen M, Alanen A & Lassila O Phenotypic Characterization of Regulatory T Cells in the Human Decidua. Clin Exp Immunol 136, 373–378 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kinder JM, Stelzer IA, Arck PC & Way SS Immunological Implications of Pregnancy-Induced Microchimerism. Nat Rev Immunol 17, 483–494 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quezada-Maldonado EM, Sánchez-Pérez Y, Chirino YI & García-Cuellar CM Airborne Particulate Matter Induces Oxidative Damage, DNA Adduct Formation and Alterations in DNA Repair Pathways. Environmental Pollution 287, 117313 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goriainova V, Awada C, Opoku F & Zelikoff JT Adverse Effects of Black Carbon (Bc) Exposure During Pregnancy on Maternal and Fetal Health: A Contemporary Review. Toxics 10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiang S. et al. Methylation Status of Individual Cpg Sites within Alu Elements in the Human Genome and Alu Hypomethylation in Gastric Carcinomas. BMC Cancer 10, 44 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neven KY et al. Placental Promoter Methylation of DNA Repair Genes and Prenatal Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution: An Environage Cohort Study. Lancet Planet Health 2, e174–e183 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ambroz A. et al. Impact of Air Pollution on Oxidative DNA Damage and Lipid Peroxidation in Mothers and Their Newborns. Int J Hyg Environ Health 219, 545–556 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao N. et al. Polymorphisms in Oxidative Stress, Metabolic Detoxification, and Immune Function Genes, Maternal Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution, and Risk of Preterm Birth in Taiyuan, China. Environmental Research 194, 110659 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ding R. et al. Dose- and Time- Effect Responses of DNA Methylation and Histone H3k9 Acetylation Changes Induced by Traffic-Related Air Pollution. Sci Rep 7, 43737 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen H. et al. Nickel Ions Inhibit Histone Demethylase Jmjd1a and DNA Repair Enzyme Abh2 by Replacing the Ferrous Iron in the Catalytic Centers. J Biol Chem 285, 7374–7383 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Micheu M-M, Birsan M-V, Szép R, Keresztesi Á & Nita I-A From Air Pollution to Cardiovascular Diseases: The emerging role Of epigenetics. Molecular Biology Reports 47, 5559–5567 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitra P, Goyal T, Singh P, Sharma S & Sharma P Assessment of Circulating Mir-20b, Mir-221, and Mir-155 in Occupationally Lead-Exposed Workers of North-Western India. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 28, 3172–3181 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tumolo MR et al. The Expression of Micrornas and Exposure to Environmental Contaminants Related to Human Health: A Review. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 32, 332–354 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mitra P, Goyal T, Sharma P, Sai Kiran G, Rana S & Sharma S Plasma Microrna Expression and Immunoregulatory Cytokines in an Indian Population Occupationally Exposed to Cadmium. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 37, e23221 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mortillo M & Marsit CJ Select Early-Life Environmental Exposures and DNA Methylation in the Placenta. Curr Environ Health Rep 10, 22–34 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ghazi T, Naidoo P, Naidoo RN & Chuturgoon AA Prenatal Air Pollution Exposure and Placental DNA Methylation Changes: Implications on Fetal Development and Future Disease Susceptibility. Cells 10, 3025 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Feil D. et al. DNA Methylation as a Potential Mediator of the Association between Indoor Air Pollution and Neurodevelopmental Delay in a South African Birth Cohort. Clin Epigenetics 15, 31 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ramaiah P. et al. The Association between Prenatal Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Childhood Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 30, 19592–19601 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gruzieva O. et al. Prenatal Particulate Air Pollution and DNA Methylation in Newborns: An Epigenome-Wide Meta-Analysis. Environ Health Perspect 127, 57012 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lodovici M & Bigagli E Oxidative Stress and Air Pollution Exposure. J Toxicol 2011, 487074 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D & Sun S-C Nf-Kb Signaling in Inflammation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2, 17023 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ren F. et al. Pm2.5 Induced Lung Injury through Upregulating Ros-Dependent Nlrp3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis. Immunobiology 227, 152207 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hajat A, MacLehose RF, Rosofsky A, Walker KD & Clougherty JE Confounding by Socioeconomic Status in Epidemiological Studies of Air Pollution and Health: Challenges and Opportunities. Environmental health perspectives 129, 065001 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bekkar B, Pacheco S, Basu R & DeNicola N Association of Air Pollution and Heat Exposure with Preterm Birth, Low Birth Weight, and Stillbirth in the Us: A Systematic Review. JAMA network open 3, e208243–e208243 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brumberg HL et al. Ambient Air Pollution: Health Hazards to Children. Pediatrics 147 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Piedrahita R. et al. The Next Generation of Low-Cost Personal Air Quality Sensors for Quantitative Exposure Monitoring. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 7, 3325–3336 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yun C. et al. Aircloud: A Cloud-Based Air-Quality Monitoring System for Everyone, < 10.1145/2668332.2668346> (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wimalasena NN, Chang-Richards A, Wang KI-K & Dirks KN Housing Risk Factors Associated with Respiratory Disease: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health 18, 2815 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kumar P, Singh A, Arora T, Singh S & Singh R Critical Review on Emerging Health Effects Associated with the Indoor Air Quality and Its Sustainable Management. Science of The Total Environment 872, 162163 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.NRDC. <https://www.nrdc.org/press-releases/report-health-costs-climate-change-and-fossil-fuel-pollution-tops-820-billion-year> (Report: Health Costs from Climate Change and Fossil Fuel Pollution Tops $820 Billion a Year).

- 99.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Evolution of the Clean Air Act, <zhttps://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/evolution-clean-air-act#:~:text=The%20Clean%20Air%20Act%20of,monitoring%20and%20controlling%20air%20pollution.> (2023).

- 100.Perera F, Cooley D, Berberian A, Mills D & Kinney P Co-Benefits to Children's Health of the U.S. Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Environ Health Perspect 128, 77006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mailloux NA, Abel DW, Holloway T & Patz JA Nationwide and Regional Pm(2.5)-Related Air Quality Health Benefits from the Removal of Energy-Related Emissions in the United States. Geohealth 6, e2022GH000603 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sampath V. et al. Improving Planetary Health Is Integral to Improving Children’s Health—a Call to Action. Pediatric Research (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.CDC. One Health, <https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/index.html> (2023).

- 104.Mahalingaiah S. Is There a Common Mechanism Underlying Air Pollution Exposures and Reproductive Outcomes Noted in Epidemiologic and In vitro Fertilization Lab-Based Studies? Fertil Steril 109, 68 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]