Introduction

Undocumented immigrants in the United States are not eligible for Medicare or insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act because of their immigration status. Twenty states and Washington, DC were recently identified to provide state-wide scheduled outpatient hemodialysis care for undocumented immigrants.1 In the other 30 states, undocumented patients with kidney failure only have guaranteed hemodialysis access under federal law when critically ill. This is associated with a high mortality rate2; high psychosocial burden for patients, clinicians, and caregivers3–5; and higher cost.6 To avoid these outcomes, health care institutions (health care systems or individual hospitals) may provide or subsidize scheduled hemodialysis care7; the mechanisms regarding how this is provided have not been formally analyzed. In this study, we sought to ascertain through brief clinician interviews how institutions supply scheduled hemodialysis care for undocumented individuals.

Methods

We interviewed clinicians in states without state-wide dialysis provisions1 who had clinical experience (e.g., care of at least two undocumented immigrants with kidney failure in the past 5 years). Participants were recruited via connection with the study investigators, snowball sampling, and institutional websites. We asked (1) what are the dialysis options for undocumented immigrants at your institution and (2) how is dialysis reimbursed? Owing to the sensitive nature of this topic, these interviews were not audio recorded, and no identifying information was recorded. This study was considered Not Human Subjects Research by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Results

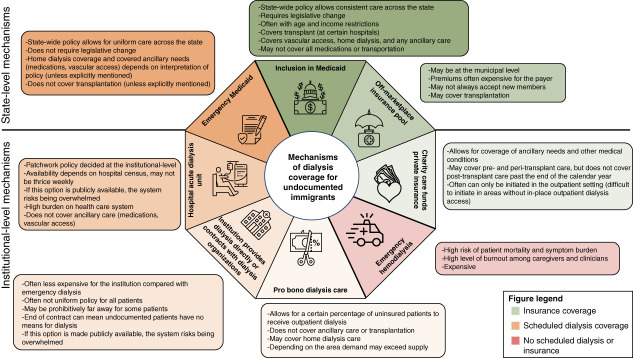

We interviewed 44 clinicians representing 27 states identified to not have state-wide provisions for hemodialysis covering undocumented individuals.1 Fifteen clinicians reported that more than one treatment mechanism was used within their institution. Five mechanisms for providing scheduled hemodialysis for undocumented immigrants through institutional or regional means were reported (Figure 1):

Provision of pro bono outpatient dialysis care: Dialysis organizations are required by regional law to provide thrice weekly scheduled dialysis to a defined percentage of uninsured individuals. Areas with a high number of uninsured patients exceeding this percentage may not have the resources to supply all patients with dialysis services.

Provision of outpatient maintenance dialysis through institutional funding: Outpatient maintenance hemodialysis is funded by the institution and provided via contracts of service with local dialysis organizations or through the institution directly for thrice weekly dialysis. This provision may be provided for all patients or may be provided on the individual level on the basis of patient characteristics. A singular institution contracting outpatient dialysis may be prohibitively far away for patients but may be the only option. Institutions funding outpatient dialysis are hesitant to make this opportunity publicly known to surrounding areas because of concerns of limited funding.

Hospital acute dialysis unit: Patients come to the emergency department or to the hospital acute dialysis unit on scheduled days of the week. These patients are not subject to meet any requirements qualifying an emergency. This practice may require a hospital admission for dialysis treatment or may be via bedded outpatient or observation status. Dialysis may be offered less frequently than the standard thrice weekly sessions (once or twice a week) if there are constraints on the hospital census or dialysis workforce. During the coronavirus disease 2019 global pandemic, a squeeze on hospital resources limited dialysis availability, leading to shorter treatment times or turning patients away.

Municipally funded off-marketplace insurance pool: Some municipalities offer affordable off-marketplace health insurance for those who are residents of the covered area, allowing for full health care coverage.

Charity-funded private health insurance: Undocumented immigrants can apply for private health insurance through a widely utilized national charity for uninsured or low-income dialysis patients funding private insurance,7 allowing for full health care coverage, including transplantation. This charity terminates at the end of the calendar year of transplant, leaving patients without health care coverage for post-transplant care.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of dialysis provision for undocumented people with kidney failure in the United States. Multiple mechanisms may be used at the state or institutional level.

Discussion

Our findings illustrate multiple strategies used to avoid emergency hemodialysis at the institutional or municipal level. Institutional strategies to fund outpatient dialysis can create differences in care on the basis of geography and may even be decided on the individual level, leading to patients receiving care of varying quality on the basis of patients' perceived adherence, disease severity, or ability to travel far distances to receive dialysis. For example, scheduled hemodialysis via the acute dialysis unit in the event of strained hospital resources can lead to undocumented patients being unable to receive reliable dialysis.

Our study had limitations. We interviewed 1–2 clinicians per state, and as such, there may be other institutional treatment mechanisms that were not captured. We did not record participant interviews or participant identifying information. Overall, we demonstrate multiple mechanisms by which institutions provide scheduled hemodialysis access for undocumented individuals. Although these strategies broaden access to scheduled outpatient dialysis, the patchwork nature of these methods are vulnerable to barriers such as geography, hospital resources, and clinician bias, which may be alleviated by state or federal policy change.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the time and expertise of the interviewed clinicians.

Disclosures

L. Cervantes reports research funding from Retrophin and other interests or relationships with Center for Health Progress Board of Directors, Denver Health Board of Directors, and National Kidney Foundation. M. Dubey reports employment with IQVIA. N.R. Powe reports advisory or leadership roles for Commonwealth Fund, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Vanderbilt University, and University of Washington. K. Rizzolo reports other interests or relationships with Health Care Justice Committee. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by NIDDK from 5T32DK007135-46 (R. Katherine).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe, Katherine Rizzolo.

Data curation: Manisha Dubey, Katherine E. Feldman, Katherine Rizzolo.

Formal analysis: Katherine Rizzolo.

Funding acquisition: Lilia Cervantes.

Investigation: Katherine Rizzolo.

Methodology: Lilia Cervantes, Katherine Rizzolo.

Supervision: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe.

Visualization: Katherine Rizzolo.

Writing – original draft: Manisha Dubey, Katherine E. Feldman, Katherine Rizzolo.

Writing – review & editing: Lilia Cervantes, Manisha Dubey, Katherine E. Feldman, Neil R. Powe, Katherine Rizzolo.

References

- 1.Rizzolo K, Dubey M, Feldman KE, Powe NR, Cervantes L. Access to kidney care for undocumented immigrants across the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(6):877–879. doi: 10.7326/m23-0202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cervantes LTD Raghavan R Linas S, et al. Association of emergency-only vs standard hemodialysis with mortality and health care use among undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA. 2018;178(2):188–195. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervantes LRS Richardson S Raghavan R, et al. Clinicians' perspectives on providing emergency-only hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants: a qualitative study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(2):78–86. doi: 10.7326/m18-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervantes LFS, Berlinger N, Zabalaga M, Camacho C, Linas SOD. The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529–535. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervantes LCA Welles CC Zoucha J, et al. The experience of primary caregivers of undocumented immigrants with end-stage kidney disease that rely on emergency-only hemodialysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2389–2397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes L, Rizzolo K, Tummalapalli SL, Powe NR. Economic impact of a change in Medicaid coverage policy for dialysis care of undocumented immigrants. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;34(7):1132–1134. doi: 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raghavan R. New opportunities for funding dialysis-dependent undocumented individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):370–375. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03680316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]