Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)—validated questionnaires that assess patients’ perspectives of their health status—have garnered increased attention in high-income countries (HICs). PROMs have been used both for clinical research and in routine clinical care to measure health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction to improve care delivery. In the field of plastic surgery, many operations are performed primarily to improve quality of life, rendering the administration of PROMs particularly relevant. Despite the importance of PROMs, their use in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) continues to be limited. Although further research is needed to comprehensively understand this issue, we discuss potential barriers of PROM use in LMICs.

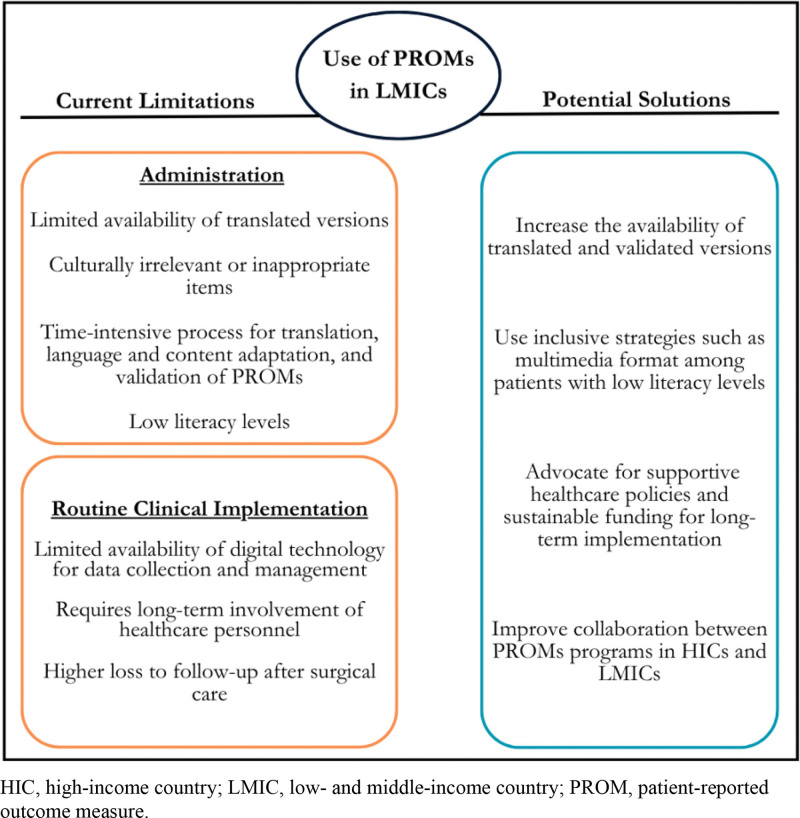

The administration of PROMs requires the availability of PROMs that are comprehensible and relevant to patients and healthcare providers. Many patients in LMICs are non-English speaking and live in areas with multiple dialects, necessitating translated versions of PROMs. However, the current availability of translations of both generic and condition-specific PROMs is limited. Furthermore, the questions asked may not be culturally relevant or appropriate if the PROM was developed in a different country or region.1 Although multiple methods have been described for translation, language and content adaptation, and validation of PROMs,2 this is a time-intensive process and may not be feasible in resource-limited settings. In addition, relative to HICs, a larger proportion of patients in LMICs have low literacy levels, requiring inclusive strategies such as adaptation to a multimedia format3 or interview-based administration of PROMs which can introduce bias. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Current limitations and potential solutions for the use of PROMs in LMICs.

The implementation of PROMs in routine clinical care in LMICs poses additional challenges. In HICs, PROMs have been increasingly collected electronically to improve data collection and management. Although digital technology has become more widely available in LMICs, its use continues to be limited among patients of lower socioeconomic status and within healthcare settings in LMICs, as it requires the engagement and training of stakeholders, alignment with local healthcare policy, sustainable funding, technological expertise, and proper infrastructure.4 In addition, long-term PROM use necessitates the involvement of healthcare personnel, which can be particularly problematic in LMICs where hospitals are substantially understaffed. Even though telemedicine can improve rates of postoperative follow-up,5 barriers such as lack of infrastructure are still prominent.

Strategies to overcome these obstacles include increasing the availability of translated PROMs and developing inclusive strategies to ensure the feasibility of PROM administration to patients with low literacy levels in LMICs. Supportive healthcare policies and sustainable funding are also crucial for the implementation and management of PROM use. International collaboration between mature PROMs programs in HIC users and fledgling programs in LMICs may also be useful. It is imperative to improve the use of PROMs to advance quality of care in LMICs by serving as an avenue to promote patient-centered care and improve clinical outcomes.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Published online 5 February 2024.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petkovic J, Epstein J, Buchbinder R, et al. Toward ensuring health equity: readability and cultural equivalence of OMERACT patient-reported outcome measures. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2448–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krogsgaard MR, Brodersen J, Christensen KB, et al. How to translate and locally adapt a PROM. Assessment of cross‐cultural differential item functioning. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31:999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long C, Beres LK, Wu AW, et al. Developing a protocol for adapting multimedia patient-reported outcomes measures for low literacy patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0252684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labrique AB, Wadhwani C, Williams KA, et al. Best practices in scaling digital health in low and middle income countries. Glob Health. 2018;14:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owolabi EO, Mac Quene T, Louw J, et al. Telemedicine in surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. World J Surg. 2022;46:1855–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]