Abstract

Introduction:

The overall impact of social connectedness on health outcomes in older adults living in nursing homes and assisted living settings is unknown. The purpose of this paper was to synthesize the literature regarding the health impact of social connectedness among older adults living in nursing homes or assisted living settings.

Methods:

Using PRISMA guidelines, we identified eligible studies from Scopus, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane databases (1990 - 2021). Bias and quality reporting assessment was performed using standardized criteria for cohort, cross-sectional, and qualitative studies. At each stage, ≥ 2 researchers conducted independent evaluations.

Results:

Of the 7,350 articles identified, 25 cohort (follow-up range: one month - 11 years; with 2 also contributing to cross-sectional), 86 cross-sectional, 8 qualitative, and 2 mixed methods were eligible. Despite different instruments used, many residents living in nursing homes and assisted living settings had reduced social engagement. Quantitative evidence supports a link between higher social engagement and health outcomes most studied (e.g., depression, quality of life). Few studies evaluated important health outcomes (e.g., cognitive and functional decline). Most cohort studies showed that lack of social connectedness accelerated time to death.

Conclusions:

Social connectedness may be an important modifiable risk factor for adverse health outcomes for older adults living in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Most studies were cross-sectional and focused on quality of life and mental health outcomes. Longitudinal studies suggest that higher social engagement delays time to death. Evidence regarding other health outcomes important to older adults was scant and requires further longitudinal studies.

Keywords: social connectedness, social engagement, nursing homes, assisted living, mental health, mortality

1. Introduction

The overall impact of social connectedness on health outcomes in older adults living in nursing homes and assisted living settings around the world is unknown. Social connectedness has been described as belonging to a web of key relationships, community, and engagement in purposeful activities in support of a valued current state (Herzog, 2002; Holt-Lundstad, 2022; "Social Connectedness: Evaluating the Healthy People 2020 Framework: The Minnesota Project," 2010). Dimensions of social connectedness are categorized into three domains: structural (e.g., social networks, integration, and affiliation), functional (e.g., perceived and received social support), and quality (e.g., social inclusion or exclusion) (Holt-Lundstad, 2022). In long-term care settings (i.e., nursing homes, assisted living), connectedness to others is key to quality of life (QOL) as social ties with peer residents can lead to a sense of belonging and being valued by others (Bradshaw, 2012; Kang et al., 2021). In nursing homes, deficits in social connectedness may be felt most acutely among residents who are cognitively impaired (Bova et al., 2021; Cahill, 2011).

Health outcomes are individual or group health status changes ascribed to interventions (Lee & Leung, 2014). They are measured either by the decline or gain in physical functioning (e.g., activities of daily living and mobility) and psychological functioning (e.g., depression and life satisfaction) in long-term care settings (Edvardsson et al., 2019). Although QOL is used interchangeably as an outcome or construct in the literature (Costa et al., 2021), it is often measured as a health-related outcome in long-term care settings (Aspen et al., 2014; Edvardsson et al., 2019). Given the unclear health impact of social connectedness for older adults in congregate long-term care settings worldwide, a comprehensive systematic review is required to evaluate the overall relationship between social connectedness and health outcomes for them. This is because there is great heterogeneity with respect to the size of long-term care facilities, the populations of older adults they serve, organizational structures (e.g., staffing types, staff-to-resident ratios, turnover), and available community-based resources, and these characteristics can either promote or discourage social connectedness (Clemens et al, 2022). For instance, a smaller number of beds, a home-like environment, a higher staffing level, and a location in an urban area are associated with greater social connectedness (Castle & Fogel, 1998; Clemens et al., 2022; Garre-Olmo et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2016).

The overall goal of this in-depth review of literature is to synthesize the qualitative and quantitative evidence about this relationship among older adults living in congregate settings (i.e., nursing homes and assisted living) in various countries. In performing this systematic review, we aim to identify consistencies in the evidence, highlight opportunities for improving the evidence base, and identify research gaps in need of further study.

2. Methods

This study was the second of two planned systematic reviews. The first focused on social isolation and loneliness (Lapane, 2022). The current systematic review includes quantitative and qualitative studies on social connectedness and engagement. The systematic review followed the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher, 2009; Shamseer, 2015). Because this was a systematic review of published research, it was not considered human subjects research. For this reason, we did not seek study approval from the University Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Study Criteria

Our inclusion criteria for the review were as follows: peer-reviewed, published in English between January 1, 1990, and August 31, 2021, used human subjects and qualitative and quantitative studies that examined social connectedness in congregate long-term care settings for older adults with health conditions as outcomes.

Conversely, our exclusion criteria for this review were studies that were not published in English (due to the lack of translation resources) and between January 1, 1990, and August 31, 2021, did not use human subjects and were not peer-reviewed. We also excluded articles of the following conditions:

Pilot studies, feasibility studies, study protocols, case studies, review articles, intervention studies, and conference papers.

Studies focused on young adults living in congregate long-term care settings as our focus was on older adults.

Studies examined social connectedness as an outcome.

Studies that did not include information on social connectedness.

Studies examined either older adults in the community settings or did not differentiate older adults living in the community or congregate settings as we are interested only in congregate long-term care settings.

2.2. Search Strategy

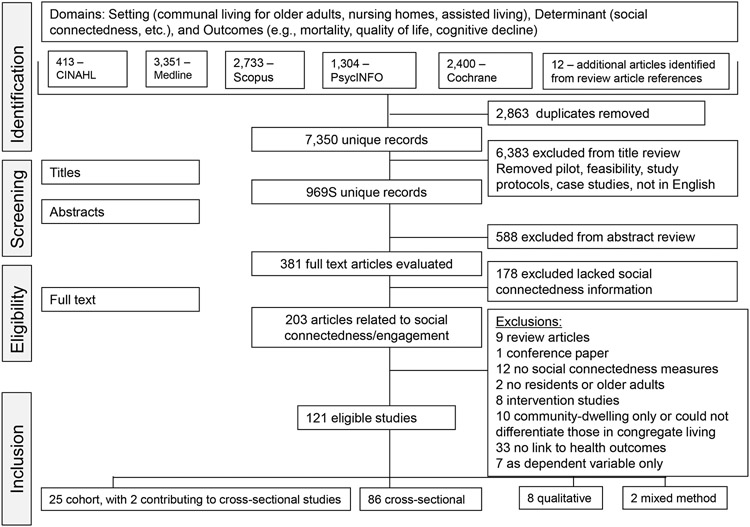

We worked with a research librarian to develop a search strategy to meet the needs of the systematic review. We shaped the search strategy in relation to three broad concepts: 1) social engagement and social connectedness, 2) health outcomes, and 3) setting (e.g., assisted living and nursing homes). The research team first developed keywords relevant to each concept. The research librarian next helped the team refine key words and develop search algorithms aligned with the domains of interest. The research librarian suggested we search five databases to cast a very wide net: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus, and Cochrane Reviews. The search algorithms used in these five databases consist of medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and text words in three aspects: 1) setting – congregate long-term care for older adults (e.g., nursing homes and assisted living); 2) determinants – factors associated with social connectedness; and 3) outcomes – health outcomes associated with older adults (e.g., mortality, cognitive decline, depression, and quality of life). Based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we limited our search in each database to include studies published between January 1, 1990, and August 31, 2021. We excluded studies that were not published in English or lacked human subjects. Articles contributing to our understanding of the association between measures of social connectedness and health outcomes were identified. A search of PROSPERO (Page, 2018) and Cochrane Reviews revealed no review on this topic (by C.E.D.) however, in the intervening time, a scoping review has been published (Lem et al, 2021). Figure 1 (see Appendix) provides the search strategy applied for the broader study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram

2.3. Review Process

Because of the vast number of articles meeting the search criteria (see Appendix), two reviewers first screened the titles to determine relevance. If either of these reviewers selected the article for further consideration, the article went on to the abstract review. For those articles proceeding to abstract review, two reviewers independently read each abstract. If both reviewers selected the abstract as eligible for full-text review, it proceeded in the process. If only one reviewer indicated it might be relevant for inclusion, a senior researcher (K.L.L.) made the final determination. We then obtained the full article for the articles deemed potentially eligible based on their title and abstract. In the last step of the eligibility determination phase, two reviewers independently evaluated each potential article for inclusion. Again, if both agreed it should move forward for further consideration, it did. If only one of the reviewers suggested it continue to be considered, a senior researcher (K.L.L.) made the final determination after re-reading and consulting with the reviewers’ notes. After this process, we identified a preliminary list of eligible studies. Additional studies may have been determined to be ineligible during the detailed abstraction process because, with detailed examination, new information was revealed that did not meet our inclusion criteria, such as ineligible study types (e.g., review articles or conference papers) or respondents’ characteristics (e.g., young adults or community-dwelling). We described these reasons for exclusion in Figure 1. Some of these articles described older adults as “elderly” and we do not endorse this ageist term. However, we retained these articles in our review so that our results would accurately reflect the extant literature in this area.

2.4. Quality Assessment

For quantitative studies, modified Downs and Black criteria (Downs, 1998) was used for cohort studies, and the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) (Downes, 2016) guided the evaluations for cross-sectional studies. For cross-sectional studies, areas of methodological quality reviewed included: 1) reporting of objectives; 2) sample selection; 3) threats to the internal validity of the study (e.g., confounding, misclassification, selection bias); 4) issues related to statistics (e.g., appropriate method, reporting of precision, power); and 5) generalizability of the study. Two or more reviewers completed the quality evaluation for each article. In the event of discordant ratings, the reviewers discussed until consensus was achieved.

Different criteria were used to evaluate the quality and bias in the qualitative studies. Using a modified version of the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research COREQ (Tong & Craig, 2007), two reviewers independently evaluated elements within three domains for each article: four items under the research team and reflexivity domain, eleven items under the study design domain, and eight items concerning the conduct and reporting of the analysis. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers and consensus was easily achieved.

2.5. Data Extraction of Key Elements and Result Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity between quantitative and qualitative studies included, we employed a segregated design to synthesize them separately (Pearson et al., 2015; Sandelowski et al., 2006). Using a descriptive synthesis approach (Dixon-Wood et al., 2005; Xiao & Watson, 2019), we created tables to present the key elements to facilitate the organization and understanding of the studies included in the review. Identification of elements to extract flowed from our specific study question. For example, policies or resources surrounding nursing home operations and the timing of nursing home admissions can encourage or limit social connectedness among older adults, which vary as a function of geography and time (Lapane et al., 2022; Veiga-Seijo et al., 2022); thus we felt it was important to provide information on the location and time frame of the study. Further, in the United States, the quality of resident information in nursing homes appears to vary by residents’ race/ethnicity. Thus, we extracted information on the race/ethnicity of the study participants (if available). Regardless of the study design, we also extracted the study purpose and key sample characteristics. For qualitative and mixed method studies, we differentiated the study type, objective, methods used, and analytic technique applied. We also summarized key findings relevant to social connectedness and its impact on residents’ lives. For quantitative studies, we did not plan to perform a meta-analysis due to the likely heterogeneity of measures, and thus a descriptive approach was employed. First, we extracted the study objective. This was important because, for some, evaluating social connectedness was not the primary reason for the study. Such studies examined social connectedness as either a mediator, moderator, or risk factor (Y. Chen, Lin, K., Wu, C., Chen, C., & Hsieh, Y, 2020; Y. M Chen et al., 2009; Cuijpers & Van Lammeren, 1999; L. W. Guse, & Masesar, M. A., 1999; Kasser & Ryan, 1999; Papi, Karimi, Amini Harooni, Nazarpour, & Shahry, 2019) and are still included in our study. We also extracted information about the operational definitions of social connectedness, the operational definitions of the outcomes under study, and key findings (e.g., the extent of social connectedness and the association between social connectedness and the health outcome). For cohort studies, we also extracted the length of follow-up. To better understand the findings of the quantitative studies, we grouped them based on their study design and tabulated their findings on health impacts of social connectedness into three categories: positive, negative, or no impact, as presented in Table 5 (see Appendix). Overall, data extraction was accomplished by one member of the research team and a second member did a quality review check, verifying that the data extracted was accurate. Any differences were discussed until consensus was achieved. The agency funding for each study was not extracted as we did not believe there would be undue influence on the study findings.

Table 5.

Synthesis of quantitative evidence by study design

| Social connectedness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive impact | Negative or no impact | |||

| Health outcomes | Cohort | Cross-sectional | Cohort | Cross-sectional |

| Death or hospital admission | 6 | 2 | ||

| Functional decline (cohort), physical function, cognitive decline | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Mental health: anxiety, depression, depressive symptoms, psychological well-being | 7 | 35 | 1 | 7 |

| Quality of life satisfaction with life, positive affect, self-esteem, morale, meaning in life, successful aging | 2 | 33 | 1 | 8 |

| Self-rated health | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| Vitality, thriving | 3 | |||

| Underweight, malnutrition, insufficient energy intake, self-feeding dependence, weight loss | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| CNS medication use: antipsychotic use or hypnotics | 1 (women) | 1 | 1 (men) | 1 |

| Symptoms: pain, dyspnea, fatigue, anomia, sleep | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Aggressive behaviors, positive behaviors | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Urinary incontinence, pressure ulcers | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

The number of studies does not equal the total number of cohort and cross-sectional studies because some studies evaluated multiple health outcomes and some studies evaluated multiple dimensions of social connectedness.

2.6. Quality Assurance of Systematic Review

Multiple steps were taken to ensure the quality of this systematic review. The research team consulted with a research librarian and searched multiple databases, casting a wide net when developing search terms. Dual review was applied at all phases of the determination for eligibility, data extraction, and quality assessment. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

We identified 381 articles potentially eligible for the current study (Figure 1). From these articles, 178 did not include information on social connectedness or engagement and thus were excluded from further review. Of the remaining 203 articles, we excluded: nine review articles, one conference paper, 12 that did not include measures of social connectedness or engagement; two studies that did not include resident participants or older adults; eight intervention studies; 10 studies that included only those who were community-dwelling or living independently or that included older adults living either in the community or in congregate living settings, but did not stratify analysis by living setting; 33 studies that did not attempt to link social connectedness to a health outcome; and 7 that considered social connectedness as the dependent variable of interest. Of the remaining 121 eligible studies, 25 were cohort, 86 cross-sectional, eight were qualitative, and two were mixed methods. Two of the eligible cohort studies also had a cross-sectional component which were included in the synthesis of the cross-sectional analyses.

3.2. Qualitative and Mixed Methods Studies

Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the eight qualitative studies and two mixed-methods studies that met the eligibility criteria. Of the 10 studies with a qualitative component, all were descriptive or exploratory in nature. The number of participants in the qualitative studies ranged from 12 (Moyle, Fetherstonhaugh, Greben, Beattie, & group, 2015) to 56 (Kaelen et al., 2021) residents. Two studies used focus groups (with residents [Leung, Wu, Lue, & Tang, 2004], with direct care staff along with interviews conducted with residents [Kaelen et al., 2021]) and the rest used interviews (with two studies [Bergland & Kirkevold, 2006, 2007] using open-ended interviews with a subset of field observations rather than a semi-structured interview format). In addition to residents, some studies included direct care staff (Kaelen et al., 2021), caregivers, and family members (Adra, Hopton, & Keady, 2015) as participants. In all studies, at least half of the participants were women (range: 50.0% [Leung et al., 2004] to 85.7% [E. Cho et al., 2017]), and all included older adults. In studies reporting participants’ marital status (Baldacchino & Bonello, 2013; Moyle et al., 2011), most were separated, widowed, or single. No studies reported the race/ethnicity of the participants. One of the two mixed methods studies included a cross-sectional study (Baldacchino & Bonello, 2013) and the other a cohort study (Potter, Sheehan, Cain, Griffin, & Jennings, 2018) to complement the exploratory qualitative research.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible qualitative studies or mixed-methods studies on the association between social connectedness and health outcomes among older adults living in nursing homes or assisted living facilities

| (Author, Year) Method Location (Year data collected) |

Objective | # of Residents and Description |

Sample Description % Female Age (years) % Race/Ethnicity % Marital status |

Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative studies | ||||

| (Adra et al., 2015) Descriptive, exploratory Lebanon (2010 to 2011) |

Explore the perspectives of quality of life for older residents, care staff, and family |

Design: Semi-structured interviews Participants: 20 residents living in 2 nursing homes, 11 caregivers, and 8 family members |

Residents: Female: 55.0% Age (Range: 65-91): 73.7 Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

Findings from residents: Maintaining family connectedness and maintaining and developing significant relationships contributed to quality of life. Conversations with family/friends were meaningful. Close bonds with others in the home created a feeling of continuity between past and present circumstances. Inadequate staffing/workload prevented more meaningful interactions between residents and staff. |

| (Bergland & Kirkevold, 2006) Descriptive, exploratory Norway (Dates of data collection not reported.) |

Investigate mentally lucid residents’ perspective on what contributes to thriving in a nursing home |

Design: Open-ended interviews and field observations Participants: 26 residents living in 2 nursing homes 16 residents included in the field observation |

Female: 76.9% Women Age: 89.5 (Range: 74 to 103) Men Age: 89.0 (Range: 81 to 99) Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

The innermost core aspect was mental attitude towards living in a nursing home. Essential to thriving was the quality of care and caregivers. Two of the five additional aspects contributing to thriving were positive relationships with peers and family but were not considered to be the core aspect contributing to thriving. |

| (Bergland & Kirkevold, 2007) Descriptive, exploratory Norway (Dates of data collection not reported.) |

Describe nursing home residents’ perceptions of the significance of relationships with peer residents to thriving |

Design: Open-ended interviews and field observations Participants: 26 residents living in 2 nursing homes 16 residents field observation |

Female: 76.9% Age: 89.4 (Range: 74 to 103) Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

Personal relationships with peer residents were not essential to thriving. The expectations, wishes, and capacity to interact with other residents varied, as did the importance of these relationships to thriving. Caregivers have a major impact on whether and how social encounters and interactions develop into positive relationships that contributed to thriving. Participating in activities did not help them form relationships that contributed to thriving. |

| (E. Cho et al., 2017) Descriptive with thematic analysis South Korea (2015) |

Explore older adults’ perceptions of daily lives in nursing homes |

Design: Semi-structured interviews Participants: 21 older adults with normal cognitive function living in 5 nursing homes |

Women: 85.7% Age: 83.6±7.1 Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

One of five themes that emerged related to residents’ desire for meaningful interpersonal relationships was to improve their quality of life. Some reported that difficulty ambulating and living with others who have cognitive impairment made it difficult to develop personal relationships. |

| (Kaelen et al., 2021) Thematic content analysis Belgium (2020) |

Understand psychosocial and mental health needs of nursing home residents during COVID-19 |

Design: Semi-structured interviews with residents Focus groups with direct care staff Participants: 56 residents living in 8 nursing homes without severe cognitive impairment |

Women: 62.5% Age (Range: 58 to 101): <79: 34.0% 80-89: 37.5% >90: 28.6% Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

Residents reported losing their social connections both inside and outside of the nursing homes, with uncertainty about when their social life could resume. Some residents reported cognitive and physical decline, symptoms of depression, and suicidal ideation as a result. |

| (Leung et al., 2004) Exploratory Taiwan (Dates of data collection not reported.) |

Compare components of quality of life among older nursing home residents to those living in the community |

Design: 4 focus groups (2 groups of men from nursing homes, 2 groups of women from nursing homes) 2 focus groups from community (1 with men only, 1 with women only) Participants: 28 older nursing home residents 16 community-dwelling older adults |

Women: 50.0% Age: 75.4±5.7 Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

Of six dimensions identified, one was related to social function. Within the social function domain, domains included: connectedness, exercise and leisure activities, social activities, and services. Regardless of setting, older adults noted that social connections with people (especially spouse, children, grandchildren) and society is important and that social activities are sources of self-efficacy. For those living in nursing homes, friendship and kinship were emphasized, as was self-needs whereas for community-dwelling older adults, relationships with family and family needs were emphasized. |

| (Moyle et al., 2011) Exploratory New South Wales and Queensland Australia (Dates of data collection not reported.) |

Understand factors that influence quality of life for people living with dementia in long-term care |

Design: Semi-structured interviews Participants: 32 residents living in 4 long-term care facilities, aged ≥65 years with dementia |

Women: 68.8% Age group: 70-79: 9.4% 80-89: 78.1% ≥ 90: 12.5% Race/ethnicity not reported. Married: 37.5% Widowed: 56.3% Single/Divorced: 6.2% |

Connections to family: Residents noted the importance of being with family and the opportunities this provided for meaningful conversations (e.g., recall previous memories, link them to the community). Family involvement improved their quality of life. Connections to staff: When family and friends no longer visited, some residents looked towards staff for companionship. But staff did not fulfil residents’ emotional needs and were too busy doing their jobs. Connections with other people (residents): Connections with other residents were important for quality of life. Limited relationships were blamed on others not reaching out (rather than under the control of the residents themselves). Forming of relationships was a challenge for some residents. |

| (Moyle et al., 2015) Descriptive with thematic analysis Brisbane and Melbourne, Australia (Date of data collection not reported.) |

Understand what influences quality of life and strategies to improve quality of life of older people with dementia living in long-term care |

Design: Semi-structured interviews Participants: 12 residents living in 4 long-term care facilities (3 from each) with early-stage dementia |

People with dementia: Women: 75.0% Age: 89.0±8.3 Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

Social interactions and satisfaction were key factors improving quality of life. Residents commented on interactions with family, friends, and residents/staff (at times not being able to differentiate staff from residents). Family: For many, quality of life was about family as they provided meaning, enjoyment, and support. Friends: Most did not mention friends from outside the facility. Memory loss affected ability to maintain friendships. Residents and staff: Being in a facility provides company. Half thought the residents provided an important source of social interactions. One participant didn’t feel he could have good conversations in the facility. Others suggested they can’t walk around to have conversations. Staff lacked time to have meaningful conversations. |

| Mixed method studies | ||||

| (Baldacchino & Bonello, 2013) Descriptive, exploratory and a cross-sectional study Malta and Australia (Dates of data collection not reported.) |

Evaluate factors related to anxiety and depression |

Design: Semi-structured interviews Participants: Older adults living in 6 nursing homes participated in the quantitative (137 residents) and qualitative study (42 residents) |

Quantitative sample: Female: 75.2% Age: 72.8 Married: 13.1% Separated/Widowed: 53.3% Single: 33.6% Qualitative sample: Female: 73.8% Age: 71.9 Race/ethnicity not reported. Married: 14.3% Separated/Widowed: 61.9% Single: 23.8% |

Three contributing factors to anxiety and depression included adaptation to institutional living, physical functioning, and personal outlook towards the future. Within the adaptation to institutional living theme, social support, social activities, and positive relationships with family, roommates, and pets were important factors to control anxiety and depression. |

| (Potter et al., 2018) Exploratory study using thematic framework and a prospective cohort study United Kingdom |

Explore the relationship between the physical environment and depressive symptoms |

Qualitative: Semi-structured interviews 15 residents in 4 care homes Quantitative: 510 residents in 50 care homes |

Qualitative sample: Female: 80% Age (range: 68-95): 85 Quantitative sample: Female: 77.0% Age: 86.4±7.3 Race/ethnicity not reported. Marital status not reported. |

The mean MDS 2.0 based index of social engagement was 4.6±1.8. The association between the index of social engagement and the geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) (adjusted for resident characteristics) did not hold when residential environmental characteristics were added to the model (β= −0.11; 95% confidence interval: −0.25 to 0.02). |

Determined from lead author via email correspondence.

Mean Age±SD (years)

Described like assisted living homes.

Findings

Most qualitative studies highlighted the importance of social connectedness on health outcomes, including QOL (Adra et al., 2015; E. Cho et al., 2017; Moyle et al., 2015; Moyle et al., 2011), cognitive and physical decline (Kaelen et al., 2021), symptoms of depression (Baldacchino & Bonello, 2013; Kaelen et al., 2021), and suicidal ideation (Kaelen et al., 2021). Two studies (Bergland & Kirkevold, 2006, 2007) suggested that positive peer relationships contributed to (but were not essential to) thriving in the nursing home setting. Barriers to developing social relationships included difficulty ambulating and living with others who have cognitive impairment (E. Cho et al., 2017; Moyle et al., 2015). Barriers to developing meaningful interactions with staff included staff shortages and heavy workloads (Adra et al., 2015; Moyle et al., 2015; Moyle et al., 2011). One mixed methods study (Baldacchino & Bonello, 2013) found that social connectedness was an important factor in controlling anxiety and depression, while another study (Potter et al., 2018) found that the association between social engagement and depression was explained by residential environmental characteristics.

3.3. Cross-sectional Studies

Characteristics

Table 2 shows that 27 of the eligible cross-sectional studies were conducted in the United States, thirteen in China, and twelve in Taiwan. Eight studies were a secondary analysis of data from a previous study (J. Cho et al., 2012; Choi, Jung, & Kim, 2018; Hsiao & Chen, 2018; H. Lee, Park, Kwon, & Cho, 2017; M. McCabe et al., 2021; Morrison-Koechl et al., 2021; Randall et al., 2011; Smit, de Lange, Willemse, Twisk, & Pot, 2016). Nine studies (Beck & Ovesen, 2003; Y. M. Chen, Hwang, Chen, Chen, & Lan, 2009; Degenholtz, Kane, Kane, Bershadsky, & Kling, 2006; Hjaltadóttir, Ekwall, Nyberg, & Hallberg, 2012; Kang, 2012; Li, Chang, & Porock, 2015; Saleh et al., 2017; Smit et al., 2016; Vanbeek, Frijters, Wagner, Groenewegen, & Ribbe, 2011) used the Minimum Data Set data and administrative data. For the studies collecting primary data, most had trained members of the research team to conduct structured interviews (face-to-face) or distribute self-administered surveys and six studies (Björk et al., 2017; Y. Chen, Ryden, M. B., Feldt, K., & Savik, K, 2000; Cohen-Mansfield & Marx, 1992; Damian, Pastor-Barriuso, & Valderrama-Gama, 2008; Fernández-Mayoralas, 2015; Marventano et al., 2015) relied on nursing home staff to collect information on the residents. Among the studies reporting the duration of the interviews, the study with the shortest interview reported 25 minutes duration (Yeung, Kwok, & Chung, 2012); the studies with the longest interview time (Bitzan, 1998; Maenhout et al., 2020) had interviews that were at least 2 hours over two sessions. One study (Beerens et al., 2016) performed an ecological momentary assessment of residents, and two studies (Jao, Loken, MacAndrew, Van Haitsma, & Kolanowski, 2018; H. Lee et al., 2017) involved video recordings. Although not all studies mentioned the sampling strategy employed, many studies noted the use of convenience samples. The study with the smallest sample size (Wahyuni, Shahdana, & Armini, 2019) included 20 residents, and the study (Björk et al., 2017) with the largest sample size included 4,831 residents. Four studies (Carpenter, 2002; H. T. Chang, Liu, L. F., Chen, C. K., Hwang, S. J., Chen, L. K., & Lu, F. H, 2010; Y. M. Chen et al., 2009; Ghusn, Hyde, Stevens, Hyde, & Teasdale, 1996) were conducted in nursing homes serving veterans that included no women, and one study had all women (Wahyuni et al., 2019). The study (Randall et al., 2011) with the oldest participants (mean age: 99.8±1.7) was specifically targeting centenarians. Marital status was not reported in 26 studies. In the studies that did report marital status, there was heterogeneity in the proportion of married (range: 3.9% [Tosangwarn, Clissett, & Blake, 2017] to 61.6% [Onunkwor et al., 2016]). Race/ethnicity was not reported in 65 studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of cross-sectional studies on the association between social connectedness/engagement and health outcomes among older adults living in congregate long-term care settings

| (Author, Year) Location |

Objective | Data Source (Years of data) |

# of Residents and Description |

Sample Description % Female Age (years) % Marital status indicators % Race/Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Beck & Ovesen, 2003) Denmark |

Estimate the influence of social engagement and dining location on dietary intake | Minimum Data Set (MDS) 2.0 data collected by registered dietician and cross-checked with nurses and medical records Energy intake derived from 4-day estimated dietary records (Not reported) |

40 residents in 2 nursing homes | Female: 82% Mean age: 83 (Range: 80-85) Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Beerens et al., 2016) Netherlands |

Investigate which aspects of daily life are related to quality of life | Ecological momentary assessment of residents (Not reported) |

115 residents with dementia living in 18 long-term care facilities | Female: 75.0% Mean age: 83.8±7.8 Widowed: 66% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Bitzan, 1998) Wisconsin, USA |

Examine the association between nursing home roommate relationships and subjective well-being | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 2 hours held over 2 sessions) Convenience sample (Not reported) |

31 residents sharing rooms with non-relatives for a ≥ 2 months | Female: 93.5% Mean age: 83 (range: 51-99) Marital status not reported. All were white; most were of German and Polish descent. |

| (Björk et al., 2017) Sweden |

Estimate the extent to which engagement in everyday activities is associated with thriving | Structured questionnaires administered to care staff who knew the residents best (2013-2014) |

4,831 residents in 172 nursing homes | Female: 67.8% Mean age: 85.5±7.8 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Carpenter, 2002) Louisiana, USA |

Evaluate associations between dimensions of social support on psychological well-being | Structured questionnaires administered to patients; staff reported ADL assessment (Not reported) |

32 newly admitted to a Transitional Care Unit at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center | Female: 0% Mean age: 67.8±8.5 Married/Partnered: 41.0% Widowed: 19.0% Divorced/separated/never: 40.0% African American: 63.0% Euro-American: 37.0% |

| (H. T. Chang, Liu, L. F., Chen, C. K., Hwang, S. J., Chen, L. K., & Lu, F. H, 2010) Taiwan |

Evaluate quality of life and related factors of senior veterans | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator to residents, face-to-face (Not reported) |

260 residents aged ≥65 years without cognitive and hearing impairments, and living in 4 veterans’ homes for >3 months | Female: 0% Mean age: 82.9±4.7 Married: 18.8% Widowed: 18.8% Divorced/never: 59.2% Others: 3.1% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (L. Chang, 2015) Taiwan |

Examine whether leisure self-determination and social support were related to acute and chronic stress | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2012) |

141 residents living in 2 nursing homes who were aged ≥65 years, no mental health conditions, and able to participate in leisure activities | Female: 62.4% Mean age: 79.4±7.1 Married: 7.8% Widowed: 72.4% Divorced: 8.5% Unmarried: 11.3% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (L. C. Chang, 2018) Taiwan |

Examine association between leisure self-determination and social support types on stress | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 35 minutes) (Not reported) |

139 residents living in 2 nursing homes who were aged ≥65 years, no mental health conditions, and able to participate in leisure activities | Female: 63.3% Mean age: 79.4±7.1 Married: 7.9% Widowed: 72.7% Divorced/never: 19.4% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Chao, 2019) Taiwan |

Determine the association between activity participation and mental health | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face Stratified probability sample (2014) |

634 residents living in 155 long-term care facilities >3 months, aged ≥60 years, able to understand and respond | Female: 60.0% Mean age: 78.3±9.1 Married: 23.7% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Y. Chen, Ryden, M. B., Feldt, K., & Savik, K, 2000) Minnesota, USA |

Examine social interaction and physical, verbal, and sexual aggression | Research staff retrieved demographic and case mix information from medical records and administered several questionnaires to residents. Research staff guided nurses and nurses’ aides who completed key instruments based on observations of residents over a 3-week period. (Not reported) |

129 residents living in 3 nursing homes and expected to stay >6 months who were cognitively impaired with Mini-Mental Status Exam scores ≤24 and consistently aggressive | Female to male ratio: 2.5 to 1 Mean age: 85.6±7.8 Married: 29.5% Widowed: 58.9% Never: 11.6% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Y. M. Chen et al., 2009) Taiwan |

Explore the relationship of urinary incontinence and physical function, cognitive status, depressive symptoms and quality of life | MDS 2.0 and structured questionnaires administered by trained nurse to residents, face-to-face (2006) |

594 residents living in 1 veterans nursing home aged ≥65 years | Female: 0% Mean age: 80.9±5.3 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Y. Chen, Lin, L., Chuang, L., & Chen, M, 2017) Taiwan |

Examine the extent to which perceived social support and depression mediate the association between functional ability and spiritual well-being | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2014-2015) |

377 residents living in 11 long-term care facilities ≥1 month, aged ≥65 years, with no hearing, visual, or cognitive impairments | Female: 61% Mean age: 79.1±10.4 Married: 25.7% Widowed: 56.0% Divorced/never: 17.0% Others: 1.3% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Y. Chen, Lin, K., Wu, C., Chen, C., & Hsieh, Y, 2020) Taiwan |

Identify determinants of quality of life | Self-administered questionnaires with researchers’ guidance when needed Convenience sample (2016-2017) |

210 residents living in 1 long-term care facility ≥ 6 months, aged ≥65 years, able to answer questions, and scored ≥ 24 on Mini-Mental State Examination | Female: 58.1% Mean age: 80.3±9.74 Married: 37.1% Widowed: 51.4% Divorced/never: 11.4% Min Nan: 85.7% Hakka: 4.8% Aborigines: 1.0% Mainland Chinese: 8.6% |

| (Y. Chen et al., 2020) Wuhan, Yichang, Huanggang, Hangzhou, Jinhua, Haikou, Sanya, Xi’an, Xianyang, Shenzhen, Beijing, Chengdu, Chongqing, China |

Investigate the extent to which perceived social support and self-rated health mediate the relationship between pain and depression | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face Convenience sample (2017-2018) |

2,154 residents living in 38 nursing homes aged ≥60 years, spoke Mandarin, without cognitive and severe hearing impairments | Female: 64.2% Mean age: 82.0±7.0 Married: 34.8% Divorced/widowed/never: 65.2% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Cheng, Lee, & Chow, 2010) Hong Kong, China |

Investigate the extent to which structural and functional social support promote psychological well-being | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 30 minutes) (Not reported) |

71 residents living in 7 nursing homes with any activity of daily living limitation and Mini-Mental State Exam score ≥18 | Female: 80.3% Mean age: 80.9±6.14 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Chipps & Jarvis, 2015) South Africa |

Investigate the association between social capital and mental well-being | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face Purposeful sampling by management of residents who may be socially isolated (2013) |

75 residents living in 1 residential care facility, aged ≥60 years and cognitively intact | Female: 77.3% 60 – 75 years: 41.3% 76-100 years: 58.7% Widowed: 60.0% Divorced/never: 40.0% White: 77.3% Indian: 22.7% |

| (J. Cho et al., 2012) Georgia, USA |

Examine the relationship of functional indicators, psychological and situational factors and fatigue | Secondary analysis of data from The Georgia Centenarian Study (Poon, 2007) Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Not reported) |

62 residents living in long-term care facilities aged ≥ 98 years and cognitively intact | Characteristics of residents living in long-term care not provided separately from community dwelling participants. |

| (Choi et al., 2018) South Korea |

Identify contributing factors of aggressive behaviors | Secondary data analysis of a random sample of participants of a nationally representative sample Trained nurses and social workers working in the nursing homes completed the assessment form (2013) |

1,447 residents living in 91 nursing homes ≥ 1 month, aged ≥65 years | Female: 77.4% Mean age: 82.8 ± 7.5 Married: 18.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Cohen-Louck & Aviad, 2020) Israel |

Examine the relationship between family support and social engagement and suicidal tendency levels and meaning in life | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Not reported) |

92 independently functioning residents of 7 nursing homes and assisted living facilities | Female: 63.0% Mean age: 81.8 ± 7.4 Married: 19.6% Widowed: 60.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Cohen-Mansfield & Marx, 1992) Maryland, USA |

Examine the relationship between social network characteristics and dimensions of agitation | Charge nurses and social workers completed the questionnaires (Not reported) |

408 residents living in 1 large nursing home | Female: 77.5% Mean age: 85 (range: 70-99) Married: 19.1% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Commerford & Reznikoff, 1996) New York, USA |

Examine the relationship of perceived social support on depression and self-esteem | Structured questionnaires administered by the investigator to residents, face-to-face (Not reported) |

83 residents living in 4 nursing homes with ≤ 2 errors on the Mental Status Questionnaire | Female: 77.1% Mean age: 80.7±10.5 Marital status not reported. White: 84.3% African American:14.5% Hispanic: 1.2% |

| (Creighton, Davison, & Kissane, 2019) Australia |

Identify biopsychosocial factors associated with anxiety | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face; research staff abstracted items from charts, and interviewed nursing staff using structured questionnaires (2015-2016) |

178 residents living in 12 nursing homes ≥3 months, aged ≥65 years, Mini-Mental State Exam score ≥18, with no/mild cognitive impairment, and no schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder | Female: 66.3% Mean age: 85.4±7.4 Married: 19.1% Widowed: 52.8% Divorced/separated/never: 27.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Cuijpers & Van Lammeren, 1999) Netherlands |

Explore the relationship between chronic illness and depression | Structured questionnaires administered by trained interviewers to residents, face-to-face; research staff interviewed nursing staff about resident’s chronic illnesses (nurses could refer to medical records) (Duration on average 1 hour) (Not reported) |

424 residents living in 10 residential homes who scored ≥ 18 on Mini-Mental State Examination | Female: 78.5% Age groups: <70: 2.1% 70-80: 23.7% 81-90: 57.8% >90: 16.4% Married: 10.5% Widowed: 74.3% Divorced: 3.8% Never: 11.3% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Cummings, 2002) Southeastern USA |

Examine the effect of functional impairment and social support on well-being | Structured questionnaires administered by trained interviewers to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 20 minutes) (Not reported) |

57 residents in an assisted-living facility who were without cognitive impairment or communication problems | Female: 78.6% Mean age: 83.7±7.4 Married: 19.6% White: 100% |

| (Cummings & Cockerham, 2004) Southeastern USA |

Explore factors associated with depression and life satisfaction | Structured questionnaires administered by trained interviewers to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 30 minutes) (Not reported) |

145 residents of 2 assisted living facilities able to communicate, and no cognitive impairment | Female: 77.4% Mean age: 84.4±7.2 Married: 16.9% Caucasian: 100% |

| (Damian et al., 2008) Spain |

Describe the physical, mental, and social factors associated with self-rated health | Structured questionnaires administered by trained geriatricians to residents, their main caregivers, and their physician (or nurse), face-to-face Multistage cluster sampling (1998-1999) |

669 residents living in 49 nursing homes | Female: 75.0% Mean age: 83.4±7.3 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Degenholtz et al., 2006) California, New York, New Jersey, Minnesota, Florida, Maryland, USA |

Determine the association between resident and facility level factors and quality of life | Interviews with residents to collect quality of life, linked with data from MDS and Online Survey and Certification Automated Record (1999-2000; 2001) |

2,829 residents living in 101 nursing facilities, aged ≥65 years, able to communicate, and in English | Female: 74.0% Mean age: 84.0±8.1 Marital status not reported. White: 89.0% |

| (Doyle, 1995) Australia |

Examine the effect of nursing staff turnover, frequency of visitors, and the presence or absence of close friends on depressive symptoms | Self-administered questionnaires reported by residents and nursing staff (director of nursing) (Not reported) |

165 residents living in 24 nursing homes, Mini-Mental State Exam score >18 | Female: 75.0% Mean age: 82.0±8.6 Married: 19.0% Widowed: 59.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Drageset et al., 2008) Norway |

Quantify the relationship between social support and health-related quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by the principal investigator to residents, face-to-face (2004-2005) |

227 residents living in 30 nursing homes > 6 months, aged ≥ 65 years, cognitively intact, and capable of carrying out a conversation | Female: 72.2% Age groups: 65-74: 8.8% 75-84: 34.4% 85-94: 45.8% ≥95: 11.0% Married or cohabitating: 16.7% Widowed: 63.4% Divorced, unmarried: 19.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Duncan, Killian, & Lucier-Greer, 2017) Arkansas, USA |

Explore the extent to which perceived social support mediates the association between leisure activity engagement and ill-being | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration between 45-60 minutes) (Not reported) |

110 older adults living in 13 long-term care facilities, Mini-Mental State Exam scores ≥25 | Female: 68.1% Mean age: 80.6±9.5 Married/Partnered: 17.3% Widowed: 44.5% Divorced/separated/never: 20.9% White: 95.5% |

| (El Zoghbi, 2014) Lebanon |

Description of nutritional status and its correlates | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2012) |

111 residents living in 3 long stay institutions longer than 4 weeks and aged ≥65 years | Female: 50.5% Mean age: Woman: 78.1 ± 1.02 Men: 74.5 ± 1.09 Married: 27.0% Widow: 24.3% Divorced: 12.6% Single: 24.3% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Fernández-Mayoralas, 2015) Spain |

Evaluate the association between leisure activity profiles and quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered to residents by health professionals working at the nursing homes who were supervised by researchers (2008 and 2010) |

759 residents living in 14 nursing homes aged ≥60 years | Female: 77.3% Mean age: 84.2±7.2 Married/Partnered: 16.2% Widowed: 60.5% Divorced/separated/never: 22.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Ghusn et al., 1996) Texas, USA |

Identify factors that enhance later life satisfaction | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (1993) |

78 residents living in 2 Veterans Affairs nursing homes | Female: 0% Age groups: 44-54: 6.4% 55-64: 28.2% 65-74: 41.0% 75-84: 20.5% > 85: 3.8% Married/Partnered: 30.8% Widowed: 15.4% Divorced/separated/never: 53.8% African American: 30.8% Caucasian: 64.1% Hispanic: 5.1% |

| (Guse, 1999) Manitoba, Canada |

Explore factors related to quality of life | Structured questionnaires (with 3 open-ended questions) administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (1997) |

32 permanent residents aged ≥55 years from 1 long-term care facility | Female: 34.0% Age groups: 65-74: 28.0% 75-84: 59.0% >84: 13.0% Married/Partnered: 34.4% Widowed: 46.9% Divorced/separated/never: 18.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Haugan, Moksnes, & Løhre, 2016) Norway |

Investigate the association between perceived nurse-patient interaction and quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2008 and 2009) |

202 residents living in 44 nursing homes > 6 months and cognitively intact | Female: 72.3% Mean age: 85.6 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Hjaltadóttir et al., 2012) Iceland |

Investigate association between residents’ health status and functional profile and quality indicators | MDS (no admission assessments) (2003-2009) |

3,694 residents living in nursing homes | Female: 66.2% Mean age: 84.3±8.2 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported |

| (Hollinger-Smith & Buschmann, 2000) Illinois, USA |

Examine factors associated with failure to thrive syndrome | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents and medical records (Not reported) |

130 residents living in 2 nursing homes for ≥2 weeks, aged ≥65 years, able to read and write in English | Female: 58.5% Mean age: 76.6±8.7 Widowed: 53.1% Single: 23.1% Caucasian: 83.8% |

| (Hsiao & Chen, 2018) Taiwan |

Investigate the associations among individual, family, and extrafamilial factors and depression | Secondary analysis of Vulnerability and Social Exclusion among Different Groups of Disadvantaged Elderly in an Aging Society: Phenomena and Strategies Project Structured questionnaires administered by research staff, face-to-face (2007) |

327 residents living in 39 care institutions, aged ≥65 years, cognitively intact with mild to no physical impairment | Female: 48.3% Mean age: 82.1±7.5 No spouse: 74.6% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Hsu & Wright, 2014) Taiwan |

Examine the association between frequency, meaningfulness, and enjoyment of social activities and depressive symptoms |

Structured questionnaires, research staff read the questions to participants needing assistance, face-to-face (Not reported) |

174 residents living in 13 long-term care facilities, aged ≥65 years, cognitively intact, able to speak Mandarin or Taiwanese, not bedridden, no severe speech/hearing impairment, no dementia or psychiatric disorder | Female: 54.0% Mean age: 78.6±7.8 Married/Partnered: 24.7% Widowed: 63.2% Divorced/separated/never: 12.1% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Jang, Park, Dominguez, & Molinari, 2014) Florida, USA |

Explore how social engagement interacts with functional disability in predicting depressive symptoms | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2004) |

150 residents living in 17 assisted living facilities, aged ≥60 years, without severe cognitive impairment | Female: 77.3% Mean age: 82.8±9.4 Married: 10.7% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Jao et al., 2018) Pennsylvania, USA |

Examine the association between social interactions and affect | Research staff extract information from medical charts, video recorded residents for 20 minutes in morning and afternoon over 5 consecutive days, and interviewed them (2005-2008) |

126 residents living in 12 nursing homes, aged ≥65 years with dementia (Mini-Mental State Exam score 7-24), who spoke English, unstable medical illness | Female: 77.0% Mean age: 86.1±6.0 Married/Partnered: 17.6% Widowed: 72.8% Divorced/separated/never: 9.5% Caucasian: 88.1% African American: 11.9% |

| (Kang, 2012) Iowa, USA |

Evaluate the association between social depression and functional and behavioral variables | MDS 2.0 Research staff extracted medications from medical charts (2008-2009) |

153 residents living in 17 nursing homes aged ≥ 60 years with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias in their medical chart | Female: 64.7% Mean age: 85.0±7.3 Married: 35.3% Widowed: 55.6% Divorced/separated: 3.3% Never: 5.9% White: 100% |

| (Kasser & Ryan, 1999) New York, USA |

Investigate the effects of autonomy support and relatedness on well-being | Structured questionnaires, research staff aided residents if needed, face-to-face (Duration on average 34 minutes) (Not reported) |

50 residents living in 1 nursing home, aged >60 years, competent to give informed consent | Female: 78.0% Mean age: 83 (range: 70-99) Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Kehyayan, Hirdes, Tyas, & Stolee, 2016) Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Canada |

Identify predictors of long-term care facility residents self-reported quality of life | Structured quality of life questionnaires administered by trained surveyors to residents (face-to-face) linked to MDS 2.0 (2010) |

928 residents in 48 long-term care facilities, without severe cognitive impairment, who spoke English | Female: 65.5% Age groups: <65: 10.6% 65-84: 46.1% ≥85: 43.3% Married: 21.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Keister, 2006) Midwestern USA |

Determine if person and situation factors were associated with health outcomes during the first week in nursing home | Structured questionnaires to residents (face-to-face) Convenience sample (1999-2000) |

114 residents who moved into 11 nursing homes in the last week and were expected to live there at least 8 weeks, aged ≥65 years, who understood and spoke English and had not been diagnosed with major depression in past 4 months | Female: 74% Mean age: 82.3±7.7 Widowed: 61.4% White: 92% |

| (Kroemeke & Gruszczynska, 2016) Poland |

Examine the association between social support and subjective well-being | Self-administered questionnaires distributed by research staff (Not reported) |

180 nursing home residents aged ≥60 years, cognitively intact, and no acute illness | Female: 67.5% Mean age: 79.1±9.1 Married: 17% Divorced/widowed/never: 83% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Kwok, Yeung, & Chung, 2011) Hong Kong, China |

Examine the moderating role of social support on the relationship between physical functional impairment and depressive symptoms | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 25 minute) Convenience sample (Not reported) |

187 residents living in 2 nursing homes, aged ≥65 years, with Mini-Mental Exam scores ≥ 18 | Female: 71.1% Age groups: 65-75: 23.0% 76-85: 40.1% >85: 36.9% Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (G. E. Lee, 2010) South Korea |

Identify predictors of nursing home life adjustment | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2007) |

156 residents living in 7 nursing homes aged >65 years, cognitively intact and healthy enough to participate | Female: 80.1% Mean age: 79.1±6.0 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (H. Lee et al., 2017) Michigan and Pennsylvania, USA |

Examined the relationship between staff–resident interactions and resident psychological well-being | Secondary analysis from a multisite study on wandering (Algase, 2008) Videotaped residents 12 20-minute observation periods on 2 non-consecutive days, between 8:00 A.M. and 8:00 P.M. Random cluster sampling (Not reported) |

110 residents living in 17 nursing homes and 6 assisted living facilities, ≥ 65 years with dementia (Mini-Mental State Exam score <24, English-speaking, not wheelchair-bound, and adequate vision/hearing | Female: 72.7% Mean age: 84±6.9 Marital status not reported. Caucasian: 70.0% |

| (Leedahl, Chapin, & Little, 2015) Kansas, USA |

Examine relationships between social integration and mental and functional health | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration not longer than 1 hour) Two-stage multilevel sampling (Not reported) |

140 long-stay residents living in 30 nursing homes, ≥ 65 years, long-term stay, able to consent, Mini-Mental Exam Score >12, and Cognitive Performance Scale <3 | Female: 74.3% Mean age: 83.1±9.0 Married: 15.0% Widowed: 55.0% White: 92.7% |

| (Li et al., 2015) New York, USA |

Examine factors associated with daytime sleep | MDS 2.0 (2005 to 2010) |

300 residents living in 1 nursing home for more than 3 months | Female: 72% Mean age: 86.9±7.0 Marital status not reported. White: 99% Hispanic or Black: 1% |

| (Lin, Wang, & Huang, 2006) Taiwan |

Examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and length of residency, health status and social support | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face Convenience sampling (Not reported) |

138 residents living in 8 nursing homes at least 6 months, aged ≥ 65 years, and cognitively intact | Female: 53.6% Mean age: 78.0±7.1 Married: 25.4% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Liu, Xue, Xue, & Hou, 2018) Xinjiang, China |

Evaluate the relationship between health literacy, self-care agency, social support and health status | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2011-2012) |

1,452 participants aged between 60 and 99 years from 44 nursing homes | None reported |

| (Maenhout et al., 2020) Belgium |

Investigate the relationship between personal, organizational, activity-related factors, and social satisfaction on quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration 2-4 hours to complete, 2 sessions in a week) Stratified random sample (Not reported) |

171 residents living in 73 nursing homes for > 1 month, aged ≥ 75 years, cognitively healthy, able to understand and answer questions | Female: 73.1% Mean age: 85.4±5.9 Married: 15.8% Widowed: 71.3% Divorced/separate/never: 11.7% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Martin et al., 2006) California, USA |

Evaluate factors associated with excessive daytime sleeping | Structured behavioral observations were performed for one minute every 15 minutes from 9:00 am–5:00 pm for 2 days (1999-2002) |

492 residents from 4 nursing homes | Female: 80.5% Mean age not reported. Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Marventano et al., 2015) Spain |

Evaluate the association between characteristics of residents with dementia and quality of life and residential care centers characteristics with quality of life | Nurses, occupational therapists, directors of nursing care, medical staff, caregivers, and proxies completed different components of the survey and chart review (2010) |

429 residents living in 14 nursing care homes aged ≥60 years with dementia | Female: 82.1% Mean age: 85.8±6.7 Married: 17.5% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (M. McCabe et al., 2021) Australia |

Evaluate the contribution of resident choice and the staff–resident relationship on resident quality of life | Secondary analysis from a randomized trial on consumer directed care (M. P. McCabe, Beattie, E., Karantzas, G., Mellor, D., Sanders, K., Busija, L., Goodenough, B., Bennett, M., Von Treuer, K., & Byers, J, 2018) Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 30-45 minutes) (2018-2020) |

604 residents living in 33 nursing homes ≥2 months, possessed adequate English communication skills, without severe cognitive impairment | Female: 64.4% Mean age: 85.4±7.7 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Mitchell & Kemp, 2000) California, USA |

Examine effects of health status and social involvement on quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 1 hour) Stratified random sample (Not reported) |

201 residents living in 55 assisted living facilities, alert without cognitive impairment | Female: 74.0% Mean age: 81±9.6 Widowed: 69.0% Non-Hispanic White: 96.0% |

| (Morrison-Koechl et al., 2021) Canada |

Explores the effects of psychosocial factors on energy intake | Secondary analysis of data from the Making the Most of Mealtimes study (Keller et al., 2017) Direct observations of mealtime experience, structured interviews with care partners, resident chart reviews, and measures of nutritional care Convenience sampling (Not reported) |

604 residents from 32 long-term care homes | Female: 68.2% Mean age: 86.8±7.8 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Nie, Hu, Zhu, & Xu, 2020) Hunan, China |

Explore risk factors for suicidal ideation | Structured questionnaire Multistage cluster random sample (2018) |

817 residents living in 24 nursing homes > 1 year, aged ≥60 years, physically and mentally able to participate, no severe hearing impairment, severe cognitive deficits, language barrier, or terminal illness | Female: 54.0% Mean age: 79.1±8.7 Divorced/loss of a partner/never married: 63.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Onunkwor et al., 2016) Malaysia |

Determine the quality of life and its associated factors | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face Stratified random sampling (2014) |

203 residents living in 8 elderly homes, aged ≥60 years, able to understand English, Malay, or Chinese, no communication problem or cognitive impairment | Female: 35.5% Mean age: 71.5±6.8 Married: 61.6% Malay: 3.0% India: 8.4% Chinese: 87.1% Others: 1.5% |

| (Papi, Karimi, Amini Harooni, Nazarpour, & Shahry, 2019) Iran |

Determine predictors of sleep disorder | Structured questionnaires, unclear if self-administered or administered by research team Convenience sample (2017) |

130 residents from 4 nursing homes aged > 60 years, no cognitive disorders | Female: reported as 66.2% in abstract and 33.8% in results Mean age: 68±7.8 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (N. S. Park, 2009) Alabama, USA |

Explore the association between social engagement and psychological well-being | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 60-90 minutes) (2006) |

82 residents living in 8 assisted living facilities, aged ≥ 65 years without dementia, capable of understanding and answering questions | Female: 74.4% Mean age: 84.0±6.1 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (S. Park & Sok, 2020) South Korea |

Examine the relationship between the factors influencing the adaptation ability and life satisfaction | Structured questionnaires distributed by research staff to residents, assistance provided by research staff if needed Random sample (2017) |

229 residents living in an elderly care facility for >6 months aged ≥ 65 years, with cognitive ability to respond, with < 2 pharmacological treatments | Female: 67.2% Age groups: 65–74: 14.8% 75–85: 41.5% ≥85: 43.7% Married: 30.1% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Patra et al., 2017) Greece |

Explore the association between social support and depression | Self-administered questionnaires distributed by research staff (2016) |

170 residents living in nursing homes aged >60 years, able to read and write in Greek, no psychiatric illness | Female: 66.5% Mean age: 79.5±7.4 Married: 11.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Pramesona & Taneepanichskul, 2018) Indonesia |

Investigate risk factors of depression | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration between 30–45 minutes) (2017) |

181 residents living in 3 homes ≥ 1 month, aged ≥60 years, no chronic diseases | Female: 65.7% Mean age: 74.4±7.6 Married: 12.2% Widowed: 56.3% Divorced/separate/never: 31.5% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Randall et al., 2011) Georgia, USA |

Investigate the influence of social relations on health outcomes | Secondary analysis of data from The Georgia Centenarian Study (Poon, 2007) Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (4 sessions, each <2 hours) (2002 – 2005) |

105 nursing home residents and 55 assisted living residents, aged ≥ 98 years and cognitively intact | Female: 78.5% Mean age: 99.8±1.7 Married: 6.0% Widowed: 85.0% White: 85.0% African American: 15.0% |

| (Rozzini et al., 1996) Italy |

Describe the association between depression and its factors | Residents were assessed by three geriatricians (Not reported) |

56 residents without severe dementia and without neurological conditions | Female: 76.8% Mean age: 81.1±8.6 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Saleh et al., 2017) British Columbia, Canada |

Explore the association between social engagement and use of antipsychotics | MDS 2.0 and the Continuing Care Information Management System (2008 – 2011) |

2,639 newly admitted long-stay residents aged ≥65 years with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias | Female: 65.8% Mean age: 83.9±6.8 Married: 35.9% Widowed: 47.9% Divorced/separate/never: 11.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Segal, 2005) Colorado, USA |

Assess the relationship of assertiveness, depression, and social support | Anonymous self-administered questionnaires (Not reported) |

50 residents of several nursing homes, older adults were free of cognitive impairment | Female: 75.0% Mean age: 74.9±11.9 Marital status not reported. Caucasian: 92.0% |

| (Smit et al., 2016) Netherlands |

Evaluate activity involvement and quality of life | Secondary analysis of data from the Living Arrangements for people with Dementia (LAD) study (Willemse & 11 (11), 2011) MDS 2.0 merged with informal caregiver and nursing home staff surveys (2010-2011) |

1,144 residents living in 144 long-term care facilities providing care for people with moderate-to very severe dementia | Female: 75.2% Mean age: 84.2±7.6 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Street, Burge, Quadagno, & Barrett, 2007) Florida, USA |

Examine how organizational characteristics, transition experiences, and social relationships impact quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by research staff to residents, face-to-face (2004-2005) |

384 residents living in assisted living facilities, aged ≥65 years, and who were cognitively intact | Female: 73.9% Mean age: 84.2±7.6 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Sun et al., 2017) Shandong, China |

Explore the roles of self-esteem, depression, and social support on quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by investigators to residents, face-to-face (2015) |

205 residents living in 5 nursing homes aged ≥60 years, without terminal illnesses, able to communicate, and cognitively intact | Female: 53.7% Mean age: 77.3±7.9 Married: 29.8% Widowed/divorced: 54.6% Single: 15.6% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Tosangwarn et al., 2017) Thailand |

Explore the association between internalized stigma, self-esteem, social support, and coping strategies and depressive symptoms | Structured questionnaires administered by nurse researcher to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 1 hour) (2015) |

128 residents living in 2 care homes, aged ≥60 years who can speak Thai and without severe cognitive impairment or psychological disturbance | Female: 62.5% Mean age: 76.9±7.8 Married/partnered: 3.9% Widowed: 48.5% Divorced/separated: 26.6% Single: 21.1% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Tseng & Wang, 2001) Taiwan |

Explore the role of social support, health status, and family interactions on quality of life | Structured questionnaires distributed by research staff to residents, assistance provided by research staff if needed (Duration on average 30-45 minutes) Convenience sample (Not reported) |

161 residents living in 10 nursing homes for > 6 months, aged ≥65 years, with good cognitive function and ability to complete the questionnaire | Female: 40.4% Mean age: 76-74±7.1 Married: 34.1% Widowed: 46.6% Unmarried: 19.3% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Tu, Lai, Shin, Chang, & Li, 2011) Taiwan |

Explore the relationship between health status, social support, and leisure activities with depression | Interviews using structured questionnaires (2007) |

309 residents living in 6 long-term care facilities, aged ≥65 years, and capable of answering questions clearly | Female: 61.2% Mean age: 81.6 Spouseless: 80.6% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Vanbeek et al., 2011) Netherlands |

Investigate the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms | MDS 2.0, collected over 3 days (2002-2003) |

502 residents living in 37 long-term care dementia units | Female: 79.7% Mean age: 85.1±7.1 Married/ partner: 26.7% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Wahyuni et al., 2019) Indonesia |

Evaluate the relationship of social support with depression | Primary data collected with a self-administered questionnaire (Not reported) |

20 residents living in 1 nursing home who could read, write, communicate verbally, and cooperate, but who did not have a serious illness | Female: 100% Age group: 60-74: 35.0% 79-90: 60.0% >90: 5.0% Widowed: 95.0% Not married: 5.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (J. Wang, Wang, Cao, Jia, & Wu, 2018) Shanghai, China |

Examine the association between social support and perceived empowerment and quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator or research assistant to residents, face-to-face (Duration ~ 45 to 125 minutes) Convenience and purposive sampling (2011-2012) |

515 residents living in 9 long term care facilities > 1 month, age ≥60 years, speak Mandarin or Shanghai dialect | Female: 60.4% Mean age: 84.0±5.2 Married: 6.2% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Wiesmann, Becker, & Hannich, 2017) Germany |

Explore association between age, social network, sense of coherence and positive aging | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator or research assistant to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 42 minutes) (Not reported) |

190 residents living in 20 nursing homes ≥ 3 months, aged ≥65 years | Female: 81.6% Mean age: 84.3±7.6 Widowed: 66.7% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Wu et al., 2017) Shandong, China |

Identify factors related to successful aging | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator or research assistant to residents, face-to-face Convenience sample (2015) |

205 resident living in 5 nursing homes, aged ≥60 years | Female: 53.7% Mean age: 77.3±7.9 Married: 29.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Wu et al., 2018) Shandong, China |

Quantify the relationship between social support and health-related quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator or research assistant to residents, face-to-face Convenience sample (2015) |

205 residents living in 5 nursing homes aged ≥60 years, without terminal illnesses, able to communicate, and cognitively intact | Female: 53.7% Mean age: 77.3±7.9 Married: 29.8% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Xu et al., 2019) Shandong, China |

Investigate the role of child visit frequency and family support in the relationship between the number of children and quality of life | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator or research assistant to residents, face-to-face Convenience sample (2016) |

371 residents living in 33 nursing homes for ≥1 month, aged ≥60 years, with Mini-Mental State Exam score≥10, with no sensory impairments affecting participation | Female: 59.3% Mean age: 77.5±8.7 Married and lived together: 8.1% Married and separated: 11.9% Han: 98.1% |

| (Yeung et al., 2012) Hong Kong, China |

Evaluate the mediating effect of institutional peer support on the relationship between physical decline and depressive symptoms | Structured questionnaires administered by research assistant to residents, face-to-face (Duration on average 25 minutes) Convenience sample (2009) |

187 residents living in 2 nursing homes without stroke, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease | Female: 71.1% Age group: 65-75: 23% 76-85: 40.1% 85+: 36.9% Married: 38.0% Widowed: 40.0% Single: 22.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Ysseldyk, Haslam Sa Fau - Haslam, & Haslam, 2013) Ontario, Canada |

Examine relationships between religion and well-being among older adults | Semi-structured interviews conducted by research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration ~60 minutes) (2002 & 2008) |

42 older adults from 3 care homes | Female: 59.5% Mean age: 86.3±5.8 Marital status not reported. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Zhang et al., 2018) Shandong, China |

Investigate the relationship among social support, physical health, and suicidal thoughts | Structured questionnaires administered by investigator or research assistant to residents, face-to-face Convenience sample (2015) |

205 residents living in 5 nursing homes aged ≥60 years, without terminal illnesses, able to communicate, and cognitively intact | Female: 53.7% Mean age: 77.3±7.9 Married: 29.8% Widowed: 53.7% Divorced: 1.0% Single: 15.6% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Zhu et al., 2020) Hunan, China |

Explore risk factors for poor sleep quality | Structured questionnaires administered by trained research staff to residents, face-to-face (Duration 30 to 60 minutes) (2018) |

817 residents living in 24 nursing homes for > 1 year and aged > 60 years | Female: 54.0% Age group: 60~69: 16.5% 70~79: 28.4% ≥80: 55.1% Marital Status Stable: 37.0% Race/ethnicity not reported. |

| (Zurakowski, 2000) USA |

Investigate the effects of social support on anomia and self-reported health | Structured questionnaires administered by trained graduate students in nursing to residents, face-to-face Convenience sample |

91 residents living in 4 nursing homes | Female: 79.1% Mean age: 79.4±16.2 Married: 8.8% Widowed: 59.3% Divorced: 4.4% Single: 27.5% White: 100% |

Determined from lead author via email correspondence.

Mean Age±SD (years)

Described like assisted living homes.

Findings

The Supplemental Table 1 shows a summary of the analyses derived from the eligible cross-sectional studies. There was great heterogeneity with respect to the measures of social connectedness used. The concepts measured included network size, social support from inside and outside of the facility, relationship to resident (family, friends, peer resident, staff), and type of support provided. Many measures captured elements of perceived social support. The most common measure of social connectedness was a version of the Index of Social Engagement (Gerritsen, 2008; Mor et al., 1995). The majority of cross-sectional studies evaluated mental health outcomes or QOL outcomes. The most common depressive symptom scale used was a version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (n=21 studies). A particular measure did not dominate studies with QOL and life satisfaction as outcomes. Most studies (but not all) attempted to adjust for various confounders. Most studies demonstrated a favorable association between social connectedness and the health outcomes studied. Across the studies, size of social network was not consistently associated with health outcomes, and the relationships with peer residents within the facilities appeared to be positively associated with health outcomes.

3.4. Cohort Studies

Characteristics