Abstract

Purpose:

Hospital visits for drug use-related bacterial and fungal infections have increased alongside overdose deaths. The incidence of mortality from these infections and the comparison to overdose mortality is not established.

Methods:

This cohort study examined mortality outcomes among adults with drug use diagnoses who were insured by public and private plans during 2007 through 2018 in North Carolina. We examined bacterial and fungal infection-related mortality and overdose mortality using cumulative incidence functions.

Results:

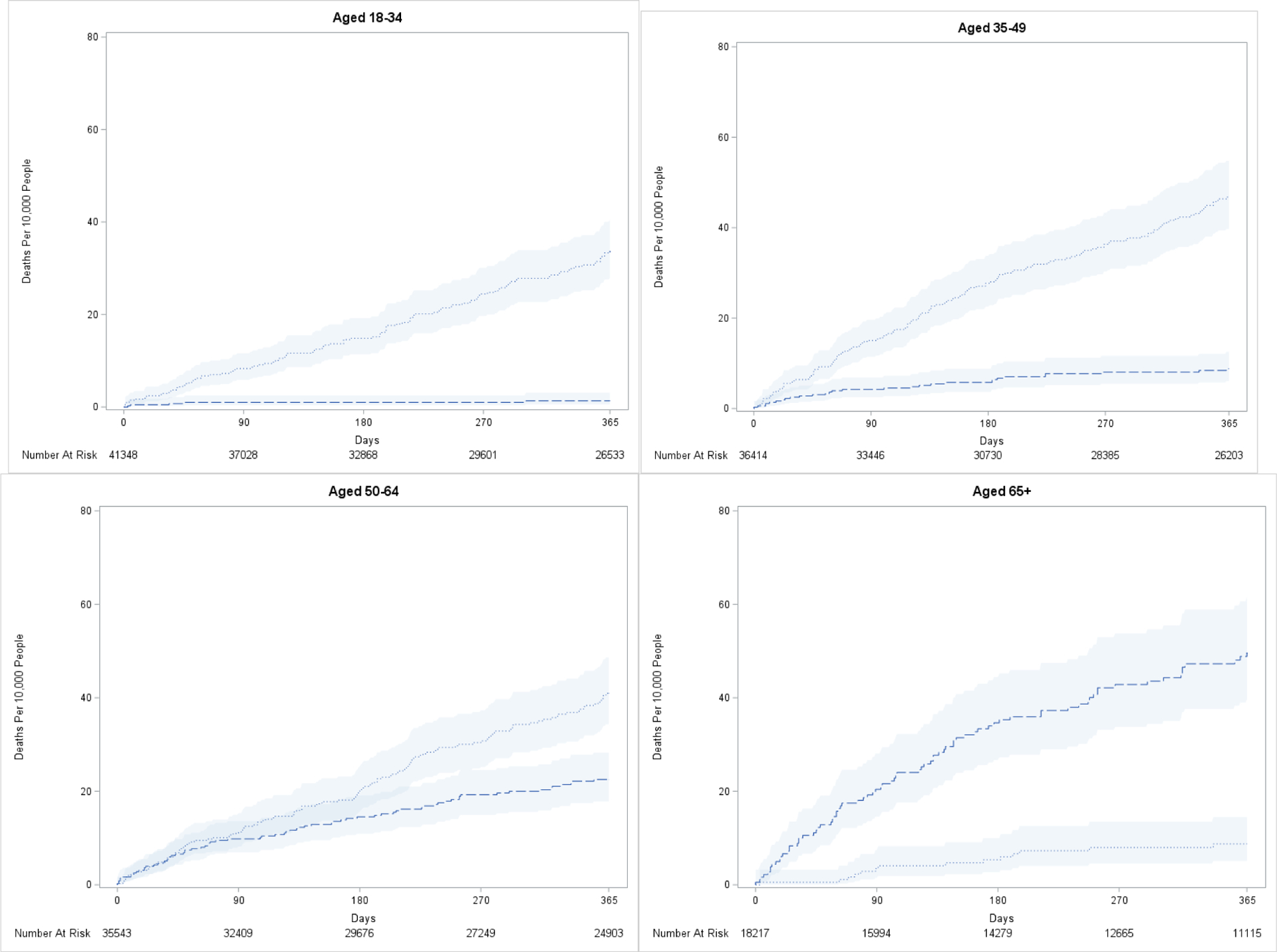

Among 131,522 people with drug use diagnoses, the median age was 45 years (interquartile range: 31–57), 58% were women and 65% had an opioid use disorder diagnosis. The one-year incidence of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality was progressively higher as age increased (35–49 years: 9 per 10,000 people, 50–64 years: 23 per 10,000, 65+ years: 50 per 10,000 people). Conversely, the one-year incidence of overdose mortality was markedly lower among older adults compared to those under the age of 65 (18–34 years: 34 deaths per 10,000 people; 35–49 years: 47 per 10,000; 50–64 years: 41 per 10,000; 65+ years: 9 per 10,000).

Conclusions:

Bacterial and fungal infections and overdose were notable causes of death among adults with drug use diagnoses, and varied by age group.

Keywords: bacterial infections, drug overdose, mortality, injection drug use, opioid use disorder

1. INTRODUCTION

Drug overdose has continued to increase substantially (1). This increase is largely driven by fluctuations in the drug supply and complex socioeconomic factors that are associated with drug harms, often including health events beyond overdose (2,3). For instance, the number of people impacted by drug use-associated bacterial and fungal infections has been rising (4–6). Compared to drug overdose trends, these drug use-associated infections have received less widespread attention and less is known about their contribution to mortality on a population level.

Bacterial and fungal infections associated with drug use include skin and soft tissue infections, infective endocarditis, and other invasive infections (osteomyelitis, spinal abscesses, sepsis) (6). In the context of drug use, the infections occur from the introduction of bacteria or fungi past the skin via contaminated drugs, via injection and drug use preparation equipment. Skin and soft tissue infections are common, with as many as nearly 70% of people who inject drugs having a lifetime history of these infections (7). Increases in drug use-associated bacterial and fungal infections have been identified across the United States since 2008 (4,8). In the general population, the one-year incidence of sepsis-associated mortality is estimates to be approximately 50 deaths per 100,000 people (9). However, this number is unknown among people who use drugs.

By using overdose as a reference indicator, studies may be able to describe the burden of drug use-associated bacterial and fungal infection mortality in the context of the ongoing overdose crisis. Therefore, the objective of this study was to describe the incidence of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality and drug overdose mortality among people receiving care for drug use. We also sought to estimate mortality incidence among demographic and clinical subgroups.

2. METHODS

2.2. Data sources and linkage

Our study used available administrative data for health insurance claims and death certificates in North Carolina from January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2018 (10). Health insurance claims included Medicaid, Medicare, and private plans, which account for approximately 70% of the insured population of North Carolina. Claims included date, diagnoses, procedures, and prescriptions for inpatient and non-inpatient encounters and services. Claims data also included information about the enrollees, such as their months of coverage and basic demographic information (date of birth, sex). Death certificate data were available for all North Carolina residents who died during the study period. Death certificate data included causes and dates of death. We linked death certificate data to the claims cohort data using a combination of probabilistic and deterministic methods (11) based on individual identifiers including name, date of birth, and gender. Supplementary Figure 1 includes detailed information about the analytic dataset creation process.

2.3. Study Design

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study among publicly and privately insured North Carolina adults (18 years old and older) who had an index (i.e., the first documented visit) drug use-associated healthcare visit that occurred from January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2018.

The target population was adults with drug use-associated healthcare visits in North Carolina. Our study population included people aged 18 years and older who had one or more inpatient visits (hospitalization), or two or more outpatient visits (all non-hospitalization visits, including doctor’s office visits and emergency department visits) occurring within a 12-month period with drug use-associated conditions. Drug use-associated diagnoses for cohort inclusion criteria were based on ICD codes for substances associated with drug-related harms at the population level (e.g., overdose, injection drug use-related complications): opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, sedative/hypnotic use disorder, and hepatitis C virus (chronic, acute, or unspecified hepatitis C virus diagnoses) for those born after 1965 (1,12) (Supplementary Table 1). The index date was seven days after the first date of hospitalization discharge for these drug use diagnoses, or the second outpatient visit occurring within a 12-month period (whichever occurred first), similar to algorithms used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicine Services(13) to reduce bias from erroneously recorded diagnoses. To reduce issues with reverse temporality between the index date and death (e.g., the index visit was coded as drug use-associated due to the subsequent cause of death, which may be the first time someone interacts with the health system for drug use reasons), we excluded those who died within the first seven days that immediately followed their index drug use diagnosis date. To allow time to establish clinical history, we excluded people who had insurance coverage less than six of the nine months prior to their index date. Given the possibility of false positive matches (i.e., those who were incorrectly linked with a death certificate), we considered anyone with a death certificate data prior to their index date as a false positive match. We also excluded those who had a death date before index date. \Of the 132,429 people who met initial criteria, we excluded: 191 who had a date of death prior to index date and 717 who died within the first seven days.

We sought to estimate the cumulative incidences of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. The index date was seven days after an individual’s first drug use-associated diagnosis date (i.e., the first date of either of the following: the date of the first inpatient discharge or the date of the second outpatient visit) (Supplementary Figure 2). For each individual, we calculated the days from their index date until death, insurance disenrollment, or end of study period at one year (whichever occurred first).

2.4. Outcomes

In the absence of a standardized definition for bacterial and infection-associated mortality, we defined this cause of death using death records ascertained from death certificate data that were preceded by any hospitalizations for invasive bacterial and fungal infections in the 30 days prior (Supplementary Table 2).

Prior issues with the sensitivity and specificity of sepsis codes (14) informed our choice of the 30-day hospitalization lookback as the primary definition. We also explored two additional infection-associated mortality definitions in sensitivity analyses that were derived from underlying and contributing causes of death listed on death certificates. The “second definition” included sepsis-associated mortality using the World Health Organizations (WHO) definition (15). The “third definition” included the WHO definition for sepsis-associated mortality plus deaths in which other invasive infections associated with injection drug use were indicated (Supplementary Table 2). These invasive infection diagnosis codes were derived from prior studies (6,8,16) and manually reviewed by study authors (MF, AS). As described in more detail in the results and discussion sections, as well as displayed in Supplementary Table 5, the three definitions showed some variation, but ultimately all were consistent in identifying bacterial and fungal infections as an notable contributor to mortality.

All-cause mortality was defined as any individual who had a linked death certificate during follow up. Cause-specific mortality was defined using the single underlying and the contributing causes of death from the ICD-10 code lists used in death certificate coding practices, and listed on the individual’s death certificates (each death could have up to 20 different causes listed). Overdose mortality included any individuals with an underlying cause of death of drug overdose (Supplementary Table 2).

2.5. Covariates

Demographic characteristics and insurance coverage were derived from the latest insurance enrollment information preceding the index date. Age was calculated using the time between an individual’s date of birth and index date. Sex categories were limited to men and women, and were collected by the insurer when an individual enrollees in a plan. While sex and gender were terms included on both, potential options for this variable was limited to female and male; therefore, we assumed it was captured sex assigned at birth. Insurance type was based on the coverage during the index month and categorized into the following: Medicaid alone, Medicare alone, Medicaid/Medicare dual enrollment, or private plans. Specific plans include individuals covered for the following reasons: Medicaid for lower income individuals, Medicare for older adults and permanently disabled individuals, and private plans for those covered through employers or via purchase.

Clinical characteristics were derived from ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes documented during the 9 months preceding an individual’s initial drug use diagnosis date (Supplementary Figure 2). All code lists are included in the supplementary materials. In addition to the substance use disorder codes used for inclusion criteria, we all assessed other substance use disorders that may be comorbid alongside other drug-related diagnosis. Substance use code lists were developed using definitions from prior studies (12,17), as well as manual review by study authors (MF, AS). The nonfatal overdose definition was based on previous case definitions (18). Skin and soft tissue infections and infective endocarditis were based on prior studies and manual review by our study team members (6,8,16). For the other clinical conditions, we used the Chronic Conditions Warehouse definitions created by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (13). Clinical characteristic definition are included in Supplementary Table 3.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We used Aalen-Johansen estimators to calculate the cumulative incidence, a method that accounts for competing events and allows estimation of risk. For cause-specific mortality, we treated all other causes of death as a competing event. We estimated the cumulative incidences among the total study population and among clinical and demographic subgroups. We also estimated the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for incidence estimates based on sample size variance. We visually examined the cumulative incidence curves by age group due to age being so closely associated with mortality. Age groups were chosen to be similar to the CDC estimates of overdose mortality (1).

In a sensitivity analysis, we estimated the cumulative incidence using the second and third infection-associated mortality definitions. We visually compared the cumulative incidence curves and assessed the level of agreement by calculating the percent of individuals with the original definition who also met criteria for the supplemental definition.

2.7. IRB statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (#20–3003).

3. RESULTS

A total of 131,522 people with drug use-associated healthcare visits were included in this cohort study. The median age was 45 years old (interquartile range = 31–57 years), and 76,779 (58.4%) people had recorded identities as women (Table 1). Medicaid was the most common insurer (47.7%, n=62,731) followed by Medicare (22.5%, n=29,538), Medicaid/Medicare (15.5%, n=20,426), and private insurance (14.3%, n=18,827). In this sample, 65.0% of people (n=85,521) had a documented diagnosis for opioid use disorder, 31.0% (n=40,742) had a documented stimulant use disorder, and 25.4% (n=24,757) had an unspecified substance use disorder (substance use diagnoses are not mutually exclusive).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and comorbidity history among a cohort of people with drug use diagnosesa occurring during 2007–2018 in North Carolina (N=131,522).

| Individual Characteristics | Number of People | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 18–34 | 41,348 | 31.4% |

| 35–49 | 36,414 | 27.7% |

| 50–64 | 35,543 | 27.0% |

| 65+ | 18,217 | 13.9% |

| Sex, women | 76,779 | 58.4% |

| Insurer | ||

| Medicaid | 62,731 | 47.7% |

| Medicare | 29,538 | 22.5% |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 20,426 | 15.5% |

| Private | 18,827 | 14.3% |

| Substance use disorders b | ||

| Alcohol | 24,757 | 18.8% |

| Cannabis | 18,547 | 14.1% |

| Hallucinogen | 366 | 0.3% |

| Opioid | 85,521 | 65.0% |

| Sedative/hypnotic | 17,348 | 13.2% |

| Stimulants | 40,742 | 31.0% |

| Unspecified or polysubstance | 33,380 | 25.4% |

| Nonfatal overdose | 24,757 | 18.8% |

| Mental health conditions | ||

| Anxiety | 56,228 | 42.8% |

| Bipolar | 25,864 | 19.7% |

| Depression | 58,494 | 44.5% |

| Intellectual disabilities | 961 | 0.7% |

| Personality disorders | 7,269 | 5.5% |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 9,205 | 7.0% |

| Schizophrenia | 15,324 | 11.7% |

| Infections | ||

| Skin and soft tissue infections | 16,419 | 12.5% |

| Endocarditis | 830 | 0.6% |

| Hepatitis B virus | 740 | 0.6% |

| Hepatitis C virusc | 10,327 | 7.9% |

| HIV | 2,888 | 2.2% |

| Other conditions | ||

| Cancer | 5,363 | 4.1% |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22,662 | 17.2% |

| Diabetes | 26,548 | 20.2% |

| Chronic pain | 65,095 | 49.5% |

| Heart failure | 11,384 | 8.7% |

| Liver disease | 10,972 | 8.3% |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1,215 | 0.9% |

People with the following drug use-related diagnosis were included in the cohort: opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, sedative/hypnotic use disorder, and/or hepatitis C virus for those born after 1965.

Not mutually exclusive.

The incidence of all-cause mortality of 446 deaths per 10,000 people (Table 2). The one-year cumulative incidence of overdose was slightly higher than bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality (overdose: 36 deaths per 10,000 people; bacterial and fungal infections: 16 per 10,000); yet, these incidences varied greatly by age group. Of all 185 infection-associated deaths, less than eleven people also were classified as dying from an overdose (number suppressed due to data use agreements).

Table 2.

One-year incidence of all-cause mortality, overdose mortality, and bacterial and fungal infection-related mortality by demographic and clinical characteristics subgroups among a cohort of people with drug use diagnosesa during 2007–2018 in North Carolina (N=131,522).

| All-Cause Mortality | Bacterial and Fungal Infection-Related Mortality | Overdose Mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | Number At Risk | Deaths per 10,000 People | 95% Confidence Interval | Deaths per 10,000 People | 95% Confidence Interval | Deaths per 10,000 People | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Overall | 131,522 | 446 | (434–458) | 16 | (14–18) | 36 | (33–40) |

| Age group (years) | |||||||

| 18–34 | 41,348 | 93 | (83–104) | -- | 34 | (28–40) | |

| 35–49 | 36,414 | 266 | (249–284) | 9 | (6–13) | 47 | (40–55) |

| 50–64 | 35,543 | 611 | (585–638) | 23 | (18–28) | 41 | (34–49) |

| 65+ | 18,217 | 1,249 | (1198–1301) | 50 | (40–62) | 9 | (5–15) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Men | 54,743 | 550 | (530–571) | 22 | (18–26) | 47 | (41–53) |

| Women | 76,779 | 371 | (357–386) | 12 | (10–15) | 28 | (24–33) |

| Insurance type | |||||||

| Private | 18,827 | 71 | (58–87) | -- | 23 | (16–31) | |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 20,426 | 557 | (526–590) | 28 | (21–36) | 62 | (51–73) |

| Medicaid | 62,731 | 294 | (280–309) | 7 | (5–9) | 34 | (29–39) |

| Medicare | 29,538 | 890 | (855–925) | 35 | (29–43) | 27 | (21–34) |

| Clinical diagnoses | |||||||

| Opioid use disorder | 85,521 | 458 | (443–473) | 18 | (15–21) | 38 | (33–42) |

| Stimulant use disorder | 40,742 | 362 | (343–383) | 12 | (9–16) | 40 | (34–47) |

| Sedative use disorder | 17,348 | 571 | (534–609) | 13 | (8–21) | 72 | (59–87) |

| Drug overdose | 12,863 | 644 | (599–690) | 21 | (14–31) | 127 | (107–149) |

| Skin and soft tissue infections | 16,419 | 787 | (744–832) | 64 | (53–79) | 54 | (43–68) |

| Infective endocarditis | 830 | 1,719 | (1456–2002) | 446 | (316–607) | -- | |

| Hepatitis C virus | 10,327 | 703 | (652–757) | 27 | (18–39) | 68 | (52–87) |

| Chronic pain | 65,095 | 626 | (606–646) | 25 | (22–30) | 41 | (36–47) |

People with the following drug use-related diagnosis were included in the cohort: opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, sedative/hypnotic use disorder, and/or hepatitis C virus for those born after 1965.

Overdose mortality was much higher than bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality among people aged 18–49 years (Figure 1). Among people aged 50–64 years, overdose mortality was also higher, but the gap between overdose and bacterial and fungal mortality was less than the difference observed among those 18–49 years old. However, among people aged 65 years and older, the incidence of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality was much higher than overdose mortality.

Figure 1.

Bacterial and fungal-related mortality and overdose mortality among a cohort of people with drug use diagnosesa during 2007–2018 in North Carolina (N=131,522).

aPeople with the following drug use-related diagnosis were included in the cohort: opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorder, sedative/hypnotic use disorder, and/or hepatitis C virus for those born after 1965.

Cause-specific mortality also varied by insurer (Supplementary Figure 5). The one-year incidence of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality was highest among those covered by Medicare (35 per 10,000) and lowest among those covered by private insurance (<0.1%, number suppressed due to low cell counts) (Table 2). Overdose mortality was highest among those covered by Medicaid/Medicare (62 per 10,000) and lowest among those covered by private insurance (23 per 10,000).

Among the clinical characteristics explored, the one-year incidence of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality was highest among those with a history of endocarditis (446 per 10,000), followed by those with a history of skin and soft tissue infections (64 per 10,000) (Table 2). The one-year incidence of overdose was highest among those with a history of nonfatal overdose (127 per 10,000) (Table 2).

In sensitivity analyses comparing two additional definitions for infection-associated mortality, the incidence using the original definition (i.e., invasive infection hospitalization in 30 days prior to death) was lower than both definitions derived from the causes of death listed on death certificates (Supplementary Figure 6). Notably, the sepsis-associated mortality definition appeared to account for the majority of deaths identified via death certificates. Among all people who met the original definition for bacterial and fungal infection related mortality (N=185), 34% (N=63) also met criteria for the sepsis-associated mortality definition (i.e. sepsis as a cause of death) and 43% (N=79) met criteria for the death certificate derived bacterial and fungal infection mortality definition (i.e. invasive infections or sepsis as causes of death).

4. DISCUSSION

Bacterial and fungal infections are an underrecognized cause of death among people with drug use-associated medical encounters. The contributions of infections and overdose to mortality vary by age. Specifically, bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality was more common than overdose among older age groups and overdose mortality was more common than infection mortality among younger age groups. In the general population, the one-year incidence of sepsis-associated mortality is estimates to be 5 deaths per 10,000 people (9). When examining sepsis-associated mortality in our sensitivity analysis, there were approximately 43 deaths per 10,000 people, speaking to the outsized degree to which severe, life-threatening infections impact people with drug use diagnoses.

Among our study population, nearly 500 of every 10,000 people died during the first year after their initial drug use diagnosis. In comparison, the incidence of mortality among all North Carolina adults (regardless of insurance access or drug use history) was approximately 114 deaths per 10,000 people in 2018 (19). Overdose was a notable contributor to death among our study population, as described in other studies (20,21). Bacterial and fungal infections were another notable contributor to death among our study population. Few studies have examined bacterial and fungal-infection-associated mortality among people who use drugs. However, one study found that 2.5% of all deaths over several decades were attributed to sepsis (22). Other research has primarily focused on mortality after people are diagnosed with drug use-associated endocarditis, with one-year mortality incidences ranging from 16–25% (23–25). Our study builds on this prior knowledge by using more recent data, including a statewide population, and using standardized follow-up periods for more stable estimates. Given how many people died from causes other than overdose or infections, more research is needed to describe cause-specific mortality among this population, and how that compares to the general population.

Age group and insurance type were two characteristics that displayed wide variation in cause-specific mortality incidences. All age groups were impacted by overdose mortality, including older adults (an often-overlooked age group in terms of overdose research). In our study population, bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality was higher than overdose among those aged 65 years and older. Although, it is not clear whether older adults are more at risk for drug use-related infectious complications or if, by virtue of their age and presumed comorbidities, are more likely to die as a result of the infection. Cause-specific mortality also differed among insurance populations, representing the heterogeneity across data sources.

Federal support for overdose prevention and harm reduction programs has increased in recent years (26). Given the systematic and individual-level complexity in drug use-associated harms, additional support is needed to address drug use-associated harms more comprehensively, rather than focusing solely on one health issue at a time or one mechanism of funding. This is particularly important as the drug supply is rapidly changing, which introduces more concerns about potential harms beyond overdose. For example, a tranquilizer called xylazine, was appeared in the drug supply since the end of this study period and is associated with skin lesions that may further complicated the state of mortality due to infections (27). To address these multifaceted drug use-related needs within our communities, many successful models for community-based harm reduction programs are present (28,29). However, in order for these programs to expand services capacity and maintain sustainability, additional and continuous infrastructural support is needed. In healthcare settings, more comprehensive and compassionate care is essential for people who use drugs. Compassionate care is critical, particularly for marginalized populations like people who use drugs. Harm reduction-oriented models based both in clinical and community settings are an approach to improve quality of care.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting study results. First, our primary definition for bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality required someone to be hospitalized before their death. We assumed that invasive infections would often be severe enough for people to seek care at this hospital. For those who truly died from bacterial and fungal infections within the community (i.e., they did not have a hospitalization in the 30 days prior to their death), we assume that typical death investigation procedures would be unlikely to identify or document infections as a cause of death. Therefore, our estimate of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality is likely an underestimate. To assess this issue further, our sensitivity analyses explored two additional definitions of bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality using cause of death data, which displayed higher incidence estimates. However, these deaths were largely driven by sepsis codes, which can be non-specific and may or may not be related to factors not directly associated with drug use (14). Even still, all three definitions showed these infections were notable causes of mortality, even when compared to overdose mortality. To understand these trends on a broader population level, validation studies and standardized case definitions should be created. Second, drug use measurement in claims data is subject to misclassification and measurement error, creating a variety of study-associated considerations (30). With this in mind, we created a study population that both represents people at risk of drug use-associated mortality based on population-level trends in substances that had been associated with overdose mortality during this time period (1) as well as prior validation studies (12,17). Third, the diagnosis-derived covariates are also unlikely to truly capture all instances of health conditions. Therefore, we assumed that observed covariates represent those that were severe enough to require medical care. Fourth, our population was limited to those who had insurance coverage, received reimbursable care, and had a documented drug use diagnosis. These results may not be generalizable to those who are uninsured (who may be at a higher risk of mortality due to related socioeconomic factors and direct barriers to care), people who use drugs without any drug use-associated complications (who may be at a lower risk of mortality), or those residing outside of North Carolina. Last, given the limited availability of information in claims data, important contextual factors (e.g., drug use behaviors; discrimination due to drug use, racism, and/or socioeconomic position; treatment experiences inside and outside of healthcare settings) are not available. Future studies, such as qualitative studies and community-based surveys, are needed to understand factors associated with and interventions to prevent bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Overdose and bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality are two preventable causes of death among people with drug use-associated healthcare visits. Older adults had more deaths due to bacterial and fungal infection-associated mortality, while younger adults experienced more overdose mortality. Yet, both causes of deaths were observed across all age groups. In recent years, the United States has faced an unprecedented number of lives lost to overdose. Our study suggests this number is likely an undercount of the total number of lives lost from a toxic drug supply and socioeconomic conditions that drive drug use-associated mortality. Additional efforts are urgently needed to expand support for evidence-based practices that comprehensively address drug use-associated harms, such as community-based harm reduction programs and access to medications for substance use disorders. Systematic factors that drive drug use-associated death, such as policy and social support systems, should also be carefully evaluated to fully understand potential pathways towards healthier communities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Overdose mortality is a major cause of death; less is known about drug-related infection mortality

Bacterial and fungal infections are contributors to drug-related mortality

Infection mortality was highest among older age groups

Overdose mortality was highest among younger age groups

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Numbers F31DA055345 (Figgatt). AJS was partially supported by NIH K23DA049946. SWM is partially supported by an Injury Control Research Center R49 award (CE19003092) from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Work was also supported by the Cancer Information and Population Health Resource at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, with funding provided by the University Cancer Research Fund via the state of North Carolina. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH, the CDC, and the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Public Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Author Nabarun Dasgupta of this publication has editorial relationship with the American Journal of Public Health, which is published by APHA. This relationship has been disclosed to UNC-Chapel Hill.

Conflict of Interest:

No conflict declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spencer M, Miniño A, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2001–2021 [Internet]. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2022. Dec [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/122556 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciccarone D. Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: A rapidly changing risk environment. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2017. Aug 1;46:107–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D. Opioid Crisis: No Easy Fix to Its Social and Economic Determinants. Am J Public Health. 2018. Feb;108(2):182–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capizzi J, Leahy J, Wheelock H, Garcia J, Strnad L, Sikka M, et al. Population-based trends in hospitalizations due to injection drug use-related serious bacterial infections, Oregon, 2008 to 2018. PLOS ONE. 2020. Nov 9;15(11):e0242165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.See I, Gokhale RH, Geller A, Lovegrove M, Schranz A, Fleischauer A, et al. National Public Health Burden Estimates of Endocarditis and Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections Related to Injection Drug Use: A Review. J Infect Dis. 2020. Sep 2;222(Supplement_5):S429–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy NL, Baggs J, See I, Reddy SC, Jernigan JA, Gokhale RH, et al. Bacterial Infections Associated With Substance Use Disorders, Large Cohort of United States Hospitals, 2012–2017. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2020. Jan 7 [cited 2020 Aug 13];(ciaa008). Available from: 10.1093/cid/ciaa008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larney S, Peacock A, Mathers BM, Hickman M, Degenhardt L. A systematic review of injecting-related injury and disease among people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017. Feb 1;171:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sredl M, Fleischauer AT, Moore Z, Rosen DL, Schranz AJ. Not Just Endocarditis: Hospitalizations for Selected Invasive Infections Among Persons With Opioid and Stimulant Use Diagnoses-North Carolina, 2010–2018. J Infect Dis. 2020. Sep 2;222(Supplement_5):S458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prest J, Sathananthan M, Jeganathan N. Current Trends in Sepsis-Related Mortality in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2021. Aug 1;49(8):1276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer AM, Olshan AF, Green L, Meyer A, Wheeler SB, Basch E, et al. Big data for population-based cancer research: the integrated cancer information and surveillance system. N C Med J. 2014;75(4):265–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dusetzina SB, Tyree S, Meyer AM, Meyer A, Green L, Carpenter WR. Linking Data for Health Services Research: A Framework and Instructional Guide [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014. [cited 2020 Oct 1]. (AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK253313/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janjua NZ, Islam N, Kuo M, Yu A, Wong S, Butt ZA, et al. Identifying injection drug use and estimating population size of people who inject drugs using healthcare administrative datasets. Int J Drug Policy. 2018. May;55:31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories

- 14.Epstein L. Varying Estimates of Sepsis Mortality Using Death Certificates and Administrative Codes — United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2022 Nov 22];65. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6513a2.htm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet. 2020. Jan 18;395(10219):200–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barocas JA, Gai MJ, Amuchi B, Jawa R, Linas BP. Impact of medications for opioid use disorder among persons hospitalized for drug use-associated skin and soft tissue infections. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2020. Oct 1;215:108207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, Parsons GA, Nilsson CI, Alibhai A, et al. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008. Aug;43(4):1424–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology (DOSE) System [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/nonfatal/case.html

- 19.CDC WONDER [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 10]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- 20.Larney S, Peacock A, Tran LT, Stockings E, Santomauro D, Santo T, et al. All-Cause and Overdose Mortality Risk Among People Prescribed Opioids: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2020. Dec 25;21(12):3700–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krawczyk N, Eisenberg M, Schneider KE, Richards TM, Lyons BC, Jackson K, et al. Predictors of Overdose Death Among High-Risk Emergency Department Patients With Substance-Related Encounters: A Data Linkage Cohort Study. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2020. Jan 1;75(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Mehta SH, Astemborski J, Piggott DA, Genberg BL, Woodson-Adu T, et al. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a prospective cohort followed over three decades in Baltimore, MD, USA. Addiction. 2022;117(3):646–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leahey PA, LaSalvia MT, Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Rowley CF. High Morbidity and Mortality Among Patients With Sentinel Admission for Injection Drug Use-Related Infective Endocarditis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2019. Mar 1 [cited 2020 Aug 12];6(ofz089). Available from: 10.1093/ofid/ofz089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Straw S, Baig MW, Gillott R, Wu J, Witte KK, O’regan DJ, et al. Long-term Outcomes Are Poor in Intravenous Drug Users Following Infective Endocarditis, Even After Surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. Jul 27;71(3):564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman-Meza D, Weiss RE, Gamboa S, Gallegos A, Bui AAT, Goetz MB, et al. Long term surgical outcomes for infective endocarditis in people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019. Nov 8 [cited 2020 Sep 1];19. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6839097/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Affairs (ASPA) AS for P. Overdose Prevention Strategy. 2021. [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Harm Reduction. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/overdose-prevention/harm-reduction [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson J, Pizzicato L, Johnson C, Viner K. Increasing presence of xylazine in heroin and/or fentanyl deaths, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010–2019. Inj Prev. 2021. Feb 3; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ, Hickman M, Weir A, Van Velzen E, et al. Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014. Feb 1;43(1):235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huyck M, Mayer S, Messmer S, Yingling C. Community Wound Care Program Within a Syringe Exchange Program: Chicago, 2018–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020. Jun 18;110(8):1211–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Figgatt MC, Schranz AJ, Hincapie-Castillo JM, Golightly YM, Marshall SW, Dasgupta N. Complications in Using Real-World Data to Study the Health of People Who Use Drugs. Epidemiology. 2023. Mar 1;34(2):259–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.