Summary

The ability to sense and respond to infection is essential for life. Viral infection produces double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) that are sensed by proteins that recognize the structure of dsRNA. This structure-based recognition of viral dsRNA allows dsRNA sensors to recognize infection by many viruses, but it comes at a cost – the dsRNA sensors cannot always distinguish between ‘self’ and ‘nonself’ dsRNAs. ‘Self’ RNAs often contain dsRNA regions, and not surprisingly, mechanisms have evolved to prevent aberrant activation of dsRNA sensors by ‘self’ RNA. Here we review current knowledge about the life of endogenous dsRNAs in mammals – the biosynthesis and processing of dsRNAs, the proteins they encounter, and their ultimate degradation. We highlight mechanisms that evolved to prevent aberrant dsRNA sensor activation and the importance of competition in the regulation of dsRNA sensors and other dsRNA binding proteins.

"eTOC blurb"

Recognition of foreign and endogenous dsRNAs is complicated by the sequence-independent binding of dsRNA binding proteins. Cottrell, Andrews and Bass review the synthesis, processing, binding and degradation of dsRNAs. They highlight the mechanisms that prevent dsRNA sensors from binding to endogenous dsRNAs and activating innate immunity pathways.

Introduction

During the 1970s, scientists realized viral infection of mammalian cells generated viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) that inhibited protein synthesis1,2 and triggered the interferon (IFN) response.3 Today we know that all viruses make dsRNA using mechanisms involving defective interfering particles, panhandle structures and convergent transcription,4,5 and that host responses to viral infection are driven by binding of viral dsRNA to dedicated immune sensors.6 Upon recognizing dsRNA, these “dsRNA sensors” activate diverse immune responses: the RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) and Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) instigate the IFN response; Protein kinase R (PKR) and Oligoadenylate synthases (OASs) induce growth inhibition by disrupting protein synthesis and degrading RNA, respectively, while other proteins nucleate inflammasomes to promote cell death by pyroptosis7. In this review we discuss mammalian pathways, with a focus on endogenous dsRNA binding proteins (dsRBPs) and the dsRNA sensors, RLRs and PKR (Box 1). We capitalize on recent results that emphasize the large role that competition plays in regulating dsRNA-mediated pathways, and highlight outstanding questions that can be framed in the context of a competition model.

Box 1: Innate Immune Sensors.

The RIG-I like receptors (RLRs)

In humans, RLRs are represented by three proteins: RIG-I, MDA5 and LGP2 (encoded by RIGI, IFIH1, and DHX58, respectively),5,118 which have well known roles in innate immunity. Binding of either RIG-I or MDA5 to dsRNA drives induction of IFN signaling through activation of MAVS. The third member of the RLR family, LGP2, lacks the N-terminal CARD domains found in RIG-I and MDA5 (Figure 1) and cannot directly induce signaling, but has been reported to modulate the activity of both MDA5 and RIG-I.

RLRs bind to dsRNA via their helicase domain (Figure 1), which is of the same family as the helicase domain of Dicer.119 MDA5 and RIG-I recognize specific features of dsRNA. RIG-I recognizes blunt dsRNA (no overhangs) with 5′ di- or triphosphates, which is rare among cellular transcripts, and thus allows self versus nonself discrimination. Upon binding dsRNA, RIG-I undergoes a conformational change that exposes its CARD domains, allowing interaction with MAVS, and ultimately the production of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

In contrast, MDA5 shows a preference for longer dsRNAs and does not recognize dsRNA termini.120 Instead, MDA5 exhibits length-dependent activation, efficiently forming activated filaments along perfectly paired dsRNAs. Since MDA5 does not distinguish termini, it can be activated by both viral and host dsRNAs, but this typically is prevented by ADAR A-to-I editing of endogenous dsRNA (Box 3). LGP2 acts as a cofactor for MDA5, aiding filament formation and stabilizing dsRNA interactions.121,122 Similar to RIG-I, the binding and filament formation along dsRNA exposes MDA5’s CARD domains, allowing for interacting with MAVS and activating IFN-stimulated genes.

PKR

Unlike the RIG-I family members, the dsRNA sensor PKR (encoded by EIF2AK2) binds to dsRNA via two dsRNA binding domains (dsRBDs, also referred to as dsRBMs). Like other domains that interact with dsRNA, dsRBDs bind in a sequence non-specific manner. Binding of PKR to dsRNA of a sufficient length, greater than 30 bp, promotes dimerization of PKR.123 Dimerized PKR then carries out an autophosphorylation reaction, which activates the kinase function of PKR.124 The primary substrate of PKR is the translation initiation factor eIF2α (encoded by EIF2S1). Like phosphorylation by other proteins involved in the integrated stress-response, phosphorylation of eIF2α by PKR causes a global reduction in translation initiation.125 From an antiviral perspective, activation of PKR thus serves to reduce production of viral proteins.

Even in the early studies there were hints that host cells contained dsRNA even without infection,3 but it would be decades before the actual DNA sequences that encoded and expressed dsRNA were identified. All animal cells analyzed so far express dsRNA,8,9 and in most cases these dsRNAs were identified because they contained inosine from in vivo RNA editing by Adenosine Deaminases that Act on RNA, or ADARs (Box 2). These enzymes convert adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) within dsRNA, and since they will only target dsRNA, finding an inosine in an RNA is proof it was double-stranded in vivo. While the earliest of the identified endogenous dsRNAs included coding sequences10, systematic searches for inosine-containing RNAs,11,12 made more comprehensive by next generation sequencing,13,14 led to the current view that the majority of human protein-coding genes express dsRNA in their non-coding regions, their introns and 3' UTRs.15 Most, but not all, of these expressed dsRNAs involve pairing between repetitive elements,15 and in primates these are dominated by Alu elements, of which there are over a million copies, accounting for around 10% of our genome.16 Possibly related to the fact that many dsRNAs are synthesized from regions that historically were thought of as "junk DNA", we know very little about the fate of these dsRNAs. What happens to long dsRNAs after they are transcribed in the nucleus? If they make it to the cytoplasm, how are they distinguished from the long viral dsRNAs that can infect the cytoplasm?

Box 2: ADARs.

All members of the ADAR family contain dsRBDs and a deaminase ("editase") domain (Figure 1). They are highly conserved and found in all metazoa so far analyzed,126 allowing for researchers to determine their conserved and divergent functions, from C. elegans to humans. While the deaminase domain itself can bind dsRNA,127 dsRNA affinity is further conferred via different configurations of dsRNA and Z-DNA binding domains.

ADAR1

As illustrated in Figure 1, mammals have three ADARs, each with a C-terminal catalytic domain and 2 or 3 dsRBDs. ADAR1, encoded by the ADAR gene in humans, has two isoforms, p150 and p110, and it is p150 that is responsible for suppression of dsRNA sensing by MDA5 and PKR (Box 3).65-74 The two isoforms are generated through the use of two promoters, and while the longer isoform is canonically thought of as being IFN inducible, both isoforms are induced to some extent by IFN signaling.128,129 In addition to the dsRBDs and deaminase domain, p110 and p150 both possess one or two Z-DNA binding domains (ZBDs), respectively.130 Only the first ZBD of p150 (Zα) is capable of binding Z-DNA and Z-RNA.131 While ADAR1 and ADAR2 (below) are capable of editing a wide range of dsRNA substrates, they do have some preferences. Deamination by ADAR1 and ADAR2 requires flipping of the edited adenosine out of the double helix, thus leaving an unpaired ‘orphan base’.132,133 This mechanism favors an A-C mismatch at the edited site,134 and disfavors a 5' guanosine of the targeted adenosine.132 Additionally, there is a preference for A or U on the 5’ side for both ADAR1 and ADAR2, and a 3’ G or U for ADAR2.135 The ability to bind Z-RNA, which takes on a left-handed helical structure, contributes to the editing of a small portion of the total number of RNAs edited by p150.23

ADAR2

The human ADAR2 protein is encoded by the gene ADARB1 (Adarb1, mice). Expression of ADAR2 is largely confined to the brain.136 The editing function of ADAR2 is essential in mice where it edits the GRIA2 mRNA which encodes an AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate) glutamate receptor.137 Editing of GRIA2 mRNA converts a CAG codon to CIG, thus recoding the mRNA to make Arg in place of Gln in the protein product.137 This is the only known essential recoding event in mammals.138

ADAR3

In humans, the ADAR3 protein is encoded by the gene ADARB2 (Adarb2, mice). Unlike ADAR1 and ADAR2, ADAR3 has no catalytic activity and has the ability to bind single-stranded RNA.139 ADAR3 expression is largely confined to the brain,140 where it is involved in learning and memory.141 Recent work has revealed a role for ADAR3 in glioblastoma where it regulates A-to-I editing by ADAR1, MAVS protein expression, and NF-KB signaling.142,143

A discussion of the life of a dsRNA is all about the proteins it meets along the way (Figure 1). The A-form helical structure of dsRNA has a very narrow and deep major groove, making it difficult for proteins to make sequence-specific interactions, and indeed, dsRBPs typically bind any dsRNA they encounter.17 That said, mismatches, bulges or loops that disrupt the contiguous base-paired structure of dsRNA will widen the major groove, allowing for sequence-specific interactions, and certain sequence-specific minor groove interactions allow a dsRBP to bind in a certain register.18 Regardless of the binding preferences that might occur from structural disruptions, or sequence-specific minor groove interactions, dsRBPs will still bind any dsRNA they encounter, be it cellular or viral. Yet, under healthy conditions, cells can distinguish the good from the bad. The biological pathways that have arisen to allow self versus nonself recognition of dsRNA are fascinating, and in truth, not yet fully understood. However, recent examples emphasize that sequence-independent binding allows competition to play a role in this discrimination.

Figure 1. Open-reading frame structures and subcellular locations of dsRBPs.

Domain arrangements of human dsRBPs and RLRs are depicted as colored boxes (in legend) along the length of the peptide chain (gray). Lengths and domain architectures approximately to scale. Adjacent to each schematic is the subcellular location(s) for each: N for nuclear, C for cytoplasmic, M for mitochondrial, and S for nuclear speckles. All annotations were retrieved from the UniProt database on October 13th, 2023; we note that nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling is pervasive, and it is difficult to prove exclusivity to a subcellular compartment.

What happens to endogenous dsRNA in the nucleus?

The long "self" dsRNAs we are most familiar with in mammals are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) and are within the introns and 3' UTRs of nascent transcripts. As soon as dsRNA structures are formed during transcription, a subset of the adenosines within them are deaminated by ADARs to create inosine (Box 2),19,20 which serves as a mark for "self" if the dsRNA makes it to the cytoplasm (Box 3).21 While both isoforms of ADAR1 can shuttle to the nucleus and carry out editing,22 the p110 isoform is responsible for most nuclear A-to-I editing.23,24

Box 3: A-to-I editing and suppression of innate immunity.

A-to-I editing by ADAR1 is essential for marking ‘self’ RNAs and suppressing activation of dsRNA sensors. Mutations in ADAR1 cause the interferonopathy Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome (AGS).144 (For an up to date and thorough review of the role of ADAR1 in innate immunity, see.145) Mouse knockouts of ADAR1 are embryonic lethal, with death at E11.0-E12.5.146 The Adar1−/− embryos show elevated IFN signaling and defective hematopoiesis.147 Knockout of MDA5 (encoded by the gene Ifih1) or MAVS suppresses the embryonic lethality of Adar1−/−, with mice surviving to postnatal day one.68 ADAR1-p150 specific knockouts largely phenocopy knockout of ADAR1, suggesting that ADAR1-p150 is responsible for suppression of dsRNA sensing by MDA5.67 This function of ADAR1-p150 requires A-to-I editing activity as a knockin mutant of ADAR1 that is catalytically inactive (Adar1E861A/E861A) closely phenocopies knockout of Adar1, and can be rescued by knockout of MDA5.65 Interestingly, the Adar1E861A/E861A Ifih1−/− mice live much longer than the Adar1−/− Ifih1−/− mice, suggesting editing independent roles for ADAR1. While these data strongly support the model that ADAR1-p150 suppresses MDA5 activation through A-to-I editing, some questions have remained unanswered until more recently. Foremost, what causes postnatal lethality of Adar1−/− Ifih1−/− mice. Recent work shows that PKR is activated in Adar1−/− Ifih1−/− but not Adar1E861A/E861A Ifih1−/− mice, and that knockout of PKR in addition to MDA5 (Adar1−/− Ifih1−/− Eif2ak2−/−) rescues the lethality of Adar1 knockout to adulthood.87,148 In the main text we describe the mechanism of PKR inhibition by ADAR1, which doesn’t require editing by ADAR1.

While ADAR1-p110 and ADAR1-p150 are nearly identical, both containing a deaminase domain and three dsRBDs, they are not redundant in the role of preventing PKR and MDA5 activation. This is partially driven by the localization of the two proteins, with the nuclear ADAR1-p110 primarily editing introns, while the generally cytoplasmic ADAR1-p150 primarily edits 3' UTRs, which are more likely to encounter MDA5 and PKR in the cytoplasm.23 Another key difference between the proteins is the active ZBD of ADAR1-p150, Zα. Mutations in the Zα domain are common in AGS,144 suggesting Zα has an important role in suppressing activation of dsRNA sensors. Mouse models of AGS that have hemizygous mutations of Adar1, combining point mutations in Zα with knockout of Adar1 or Adar1-p150, show varying degrees of lethality and activation of IFN signaling through MDA5.73,149,150 Similarly, the ability of ADAR1 to bind Z-RNA prevents activation of ZBP1, the only other human protein that contains a ZBD.151,152 These data highlight the importance of the ZBD for ADAR1's ability to suppress activation of dsRNA sensors by endogenous dsRNAs.

Other RNA modifications that mark ‘self’ RNAs also occur co-transcriptionally, such as pseudouridylation,25,26 and methylation to create N6-methyladenosine (m6A).27-29 m6A has been reported to preclude the formation of dsRNA30, and thus indirectly protect against aberrant immune responses. Uridines within single-stranded RNAs (ssRNAs) induce an innate immune response via the ssRNA-specific endosomal receptors TLR7 and TLR8,31,32 and the demonstration that pseudouridine reduces this response,33 gained notoriety with the recent Nobel Prize to Katalin Kariko and Drew Weissman. The "cap" structure that is added during RNAP II transcription also marks transcripts as "self",34 and prevents them from subsequent activation of the dsRNA sensor RIG-I in the cytoplasm. RIG-I recognizes the di and triphosphates on viral dsRNA (nonself) but cannot recognize the m7GpppNm “cap 1” modification that occurs on all host mRNAs (Box 1).35

RNAseq analyses readily detect dsRNA within the steady-state population of intronic sequences in the nucleus,15 but direct evidence into mechanisms of nuclear dsRNA degradation are elusive and worthy of future studies. Humans encode two dsRNA endonucleases of the RNase III family, Drosha, which processes primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) in the nucleus, and Dicer, which processes pre-miRNAs in the cytoplasm.36 Noncanonical functions in the nucleus have been suggested for both enzymes,37 with some studies indicating that Dicer is involved in degrading intermolecular dsRNA from converging transcripts.38 While direct evidence is lacking, the exclusive nuclear localization of Drosha, and its preference for cleavage at the base of a stem flanked by two single-stranded regions, makes it more suitable than Dicer for cleavage of the intramolecular dsRNAs that occur in introns. Indeed, Drosha cleavage in regions that do not encode miRNAs has been reported.39 Additionally, the vast majority of human dsRNA is found in introns, and after splicing and debranching, it is also possible that dsRNA-containing introns are rapidly degraded by the nuclear exosome.40,41 Interestingly, in processing pri-miRNAs, Drosha associates with the accessory factor DGCR8, but some studies indicate DGCR8 also has functions separate from Drosha that are mediated by interaction with exosomal components.42

While early reports indicated edited dsRNAs were retained in the nucleus,43,44 other studies indicated edited dsRNA was exported to the cytoplasm, and if within 3' UTRs, found on polysomes.45 This discrepancy might be explained if certain experimental conditions unintentionally caused stress, which sometimes leads to formation of paraspeckles, subnuclear structures that sequester RNAs.46 Composed of RNA and protein, paraspeckles have a well-defined architecture coordinated by the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) NEAT1, as well as several proteins that are essential for their formation,47 including NONO (formerly known as p54nrb) which can bind to inosine-containing RNAs.43 Other reports show that export of 3' UTRs that contain inverted Alus can be regulated by methylation of NONO48 or binding of the dsRBP STAU1 (Figure 1),49 which might also explain discrepancies in reports of nuclear retention of 3' UTRs that contain inverted Alus.

Export of dsRNA out of the nucleus

While dsRNA within introns would presumably stay in the nucleus, at least some 3' UTRs that contain dsRNA are exported to the cytoplasm and found on polysomes,45,50 however, the export mechanisms involved have not been clearly defined. Mature mRNAs with dsRNA in their 3' UTRs might be exported via conventional pathways,51 albeit some studies indicate STAU1 binding is important to overcome nuclear retention.49

Hypothetically, dsRNA could take advantage of alternative mechanisms to enter the cytoplasm. One possibility is via the exportin protein XPO5, which shuttles pre-miRNAs from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. While the binding of XPO5 to its pre-miRNA substrate is specific, and mediated by recognition of the two nucleotide 3′ overhang left after DROSHA cleavage,52 XPO5 is also known to export dsRBPs, including ADAR1-p110, ILF3, PKR, and STAU1, and in some cases this export is stimulated by dsRNA.22,53 Could these secondary interactions with dsRBPs facilitate more general dsRNA export? Additionally, during mitosis cytoplasmic PKR is activated by nuclear dsRNAs,54 suggesting that, at least in some cases, dsRNAs could simply diffuse to the cytoplasm when the nuclear envelope breaks down.

Understanding mechanisms of dsRNA export is extremely important, since aberrant export of dsRNA increases the chance of activation of dsRNA sensors in the cytoplasm; indeed some studies indicate certain viruses arrest export to decrease activation of innate immune pathways.55 Tight regulation of export might be important during times of stress, which in some cases leads to increased dsRNA. For example, after DNA double-strand breaks occur, transcription of antisense RNA is upregulated, leading to an increase in highly paired intermolecular dsRNA.38,56 If these long, perfectly paired sense•antisense dsRNAs made it to the cytoplasm, they would stimulate dsRNA immune sensors.

What happens to dsRNA in the cytoplasm?

For the dsRNAs that make it to the cytoplasm, their future is largely determined by what proteins they encounter, but how this is controlled is unclear. In healthy cells, in the absence of stress or viral infection, innate immune dsRNA sensors like the RLRs and PKR (Box 1) are expressed at low levels57,58 and cytoplasmic dsRBPs carry out their normal functions on endogenous dsRNA. A well characterized and obvious example is the processing of pre-miRNAs in the cytoplasm by the dsRBP Dicer.59,60 This exemplifies the importance of segregating longer dsRNAs, for example the pri-miRNAs, in the nucleus where they will not encounter dsRNA sensors. The shorter pre-miRNAs do not have the triphosphorylated 5’ end that would be expected to trigger RIG-I, and their short length and mismatches would preclude activation of MDA5.

Presumably, longer dsRNAs that enter the cytoplasm from the nucleus are primarily located in 3' UTRs that have been edited by ADARs. The inosines in these RNAs means that MDA5 will not be activated (Box 3), and in some cases it is clear the mRNAs are simply loaded onto ribosomes and translated.45 During translation, mRNAs can be subject to Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD), a process that serves to degrade faulty mRNAs or regulate their levels.61. Interestingly, there is a related decay process called Staufen-Mediated Decay (SMD),61 that in mammals involves STAU1 and STAU2 (Figure 1) and targets mRNAs containing regions of dsRNA in their 3' UTRs. For example, the ADP ribosylation factor (ARF1) mRNA has a short stem-loop in its 3' UTR that binds Staufen and leads to SMD.62 Other examples involve Alu elements within 3' UTRs that form dsRNA by pairing intermolecularly with complementary Alu elements in lncRNAs.63 At present it is somewhat mysterious as to which dsRNA-containing transcripts are subject to SMD, but compelling models have been proposed.64

How many endogenous dsRNAs are immunogenic, and what is their identity?

Of the ADAR family members, ADAR1-p150 seems most important for marking endogenous dsRNA as self, and loss of ADAR1 causes activation of MDA565-68 and PKR69-74 (Box 3). Most assume that the dsRNAs that activate MDA5 and/or PKR following loss of ADAR1 arise from the inverted Alu sequences that inhabit many 3' UTRs, but in truth, the identity of the immunogenic dsRNAs is not proven. RNase A protection assays performed in cells support binding of MDA5 to Alu sequences, and a decreased binding in the presence of ADAR1,75 but definitive evidence that inverted Alus are responsible for inducing an MDA5-dependent interferon response is lacking. Indeed, in vitro studies show that the oligomerization of MDA5 required for interferon induction is impeded by the mismatches that typically are found in base-paired inverted Alus, even without A-to-I editing sites; however, at higher MDA5 concentrations binding can be observed and is decreased by ADAR editing sites.75

An increasingly popular view is that only a small subset of dsRNAs are responsible for activating MDA5 following loss of ADAR1-p150,23,24 and that possibly their features have made them difficult to find.76 In a mouse mutant lacking ADAR1-p110 and ADAR2, leaving only ADAR1-p150 to carryout A-to-I editing, only 2% of edits remained.24 This 2% of remaining edits, however, was sufficient to prevent activation of type I IFN signaling downstream of MDA5.

Recent work sought to identify the ‘immunogenic’ dsRNAs that activate MDA5 following loss of ADAR1-p150 by identifying the RNAs specifically edited by ADAR1-p150 and ADAR1-p110 in human cells.77 This analysis revealed that a small subset of A-to-I edits are responsible for suppression of MDA5 activation, in agreement with prior work in mice described above. These edits largely occurred in 3′ UTRs, generally within inverted Alu repeats, and varied greatly between cell lines. Overexpression of the ADAR1-p150 specific dsRNAs caused activation of IFN signaling in the absence of ADAR1-p150 when MDA5 was overexpressed. These findings suggest that only a small number of endogenous dsRNAs are responsible for activation of MDA5 in the absence of ADAR1. Given the variability of editing across tissues, and possible changes in the expression of endogenous dsRNAs, it may be the case that the dsRNAs that activate MDA5 and/or PKR following loss of ADAR1 vary by tissue or cell type. Furthermore, given the binding preferences of PKR and MDA5, the RNAs that activate each protein in the absence of ADAR1 may not be the same. Future work is still needed to definitively identify the RNAs that bind to and activate MDA5, and importantly, PKR, following loss of ADAR1.

While our discussion above highlights the search for nuclear-derived immunogenic RNAs, in particular those edited by ADAR1-p150 to prevent activation of PKR and MDA5, it is important to note that mitochondrially-encoded RNAs can also form dsRNA that can bind to and activate dsRNA sensors like PKR.78 Bidirectional transcription of mitochondrial DNA can generate intermolecular dsRNA with perfect base-pairing in lengths much longer than the dsRNA regions arising from repetive elements, up to several kilobases.79 These mt-dsRNAs can represent a significant proportion of the RNAs identified by pulldown with a dsRNA specific antibody or by pulldown of PKR.78 In some cell lines, like HeLa or HEK293T, mt-dsRNAs represent the majority of dsRNA in the cell (70-90%), while in other cell types, like neurons, mt-dsRNAs represent a small proportion (40%).80 Given the endosymbiotic evolution of the mitochondrion within eukaryotes, it is interesting to think about what systems may have evolved to prevent sensing of mt-dsRNA as foreign RNA – even though it was originally foreign.

Regulation by competition: the intricate balance of dsRBPs and dsRNAs

Because dsRBPs are not sequence specific, changes in the concentration of a dsRBP or dsRNA, whether it derives from a virus or endogenous transcript, has the potential to change biological outcome by competition. It is our hypothesis that competition between dsRBPs and dsRNAs is operating in the nucleus, the cytoplasm, and throughout the life of a dsRNA. In the sections below we review existing examples of competition between dsRBPs and dsRNA, using these to build models whereby competition plays a natural role in the regulation of dsRBPs and their functions.

Competition between viral and host dsRBPs

The molecular arms race between viruses and the mammalian innate immune system offers numerous, long recognized,81 examples of non-sequence specific dsRBPs competing for dsRNA substrates.82,83 For example, in chicken, like in humans, MDA5 activates the type I IFN pathway upon infection with an RNA virus. The infectious bursal disease virus of chickens evades this activation via its VP3 protein.84 VP3 competes directly with MDA5 for binding to the viral dsRNA via its dsRBD.

While the favored model for the mechanism of these Viral Suppressors of RNA sensors (VSRs) involves the viral-encoded protein coating the dsRNA to sequester it from dsRNA sensors such as MDA5 or RIG-I, in many cases this has not been proven. While dsRBDs are defined by their ability to bind dsRNA, they can also form direct protein-protein interactions, such as the interaction of TRBP with Dicer.59,85 Experimental mutations that disrupt dsRNA binding may also disrupt protein-protein interaction, therefore, dsRBD mutations that preclude inhibition do not prove the VSR is coating dsRNA. Indeed, paramyxovirus V protein acts as a VSR by interacting directly with MDA5 to disrupt its folding.86

Competition between endogenous dsRBPs

While it is straightforward to understand why viruses might capitalize on the non-sequence specificity of dsRBPs and encode dsRBPs that compete with dsRNA sensors for binding to viral dsRNA, there are also many examples indicating that host dsRBPs bind each other’s substrates. While it is easy to categorize these examples as artifacts of the experimental setup, it also seems possible that competition is an intrinsic feature of the regulation of dsRBPs in cells.

Recent work shows that activation of dsRNA sensors by endogenous dsRNA can be inhibited by increased levels of endogenous dsRBPs, because the dsRBPs compete with the sensors for binding to the endogenous RNA. As discussed in Box 3, ADAR1 is essential for suppression of dsRNA sensing by MDA5 and has also been implicated in suppression of PKR activation.69-74 Whereas suppression of MDA5 activation by ADAR1-p150 is dependent on A-to-I editing, studies in ADAR1-dependent cell lines (cell lines that activate dsRNA-sensing pathways following loss of ADAR1) show that overexpression of catalytically inactive ADAR1-p150 is sufficient to suppress PKR activation and rescue cell viability.70,71 These findings suggest that ADAR1 suppresses PKR activation by endogenous dsRNA by some means other than editing, presumably through competition with PKR for dsRNA binding. More recent work directly establishes that ADAR1-p150 suppresses PKR activation through its ability to bind dsRNA.87 In this study, overexpression of the dsRBDs of ADAR1, ADAR2, and STAU1 each could prevent activation of PKR in the absence of ADAR1, suggesting the identity of the dsRBD was not as important as its general ability to bind dsRNA. Like ADAR1-p150, STAU1 has been shown to bind dsRNA within the 3' UTRs of some mRNAs and prevents activation of PKR.49 ADAR1 also inhibits STAU1 function in an editing-independent way, by competing for its dsRNA binding sites.88 These findings highlight the complex competition between these three dsRBPs – STAU1, ADAR1 and PKR.

In yet another example, the RNA helicase DHX9 functions redundantly with ADAR1 to suppress several dsRNA sensing pathways.89 It was found that in ADAR1-dependent cell lines, depletion of DHX9 caused activation of PKR, while in ADAR1-independent cell lines, depletion of both ADAR1 and DHX9 was required for activation of multiple dsRNA sensing pathways resulting in a viral mimicry phenotype. Mechanistic studies revealed that the dsRBDs of DHX9 were sufficient to rescue activation of PKR. Given the nuclear localization of DHX9, these findings suggest that DHX9 sequesters some endogenous dsRNAs in the nucleus to prevent PKR activation.

In many of the examples above, effects were rescued simply by expressing a dsRBD. Interestingly, in other cases the dsRBP may contain other domains that are important for a biological function, and competition between dsRBDs may bring in new functions. For example, by binding to mRNAs important for proper mitotic progression, the dsRBP NF90 (encoded by ILF3) stabilizes the mRNAs by competing with the dsRBPs STAU1 and STAU2 for binding, thus preventing SMD of pro-mitotic mRNAs.90 This function of NF90 is enabled by interaction with NF45 via the DZF domains of both proteins, which other studies show increases dsRNA binding by 10-fold,91 possibly allowing NF90-NF45 to better compete with STAU1 and STAU2.

While so far our discussion of competition has focused on examples involving the dsRBD, there are similar examples involving the helicase domain of Dicer. RNA-independent interactions occur between Dicer's helicase domain and ADAR1,92 TRBP and PACT,59 and competition with these interactions could also affect the balance of dsRNA and dsRBPs.92,93 RNA-dependent interactions with Dicer's helicase domain also seem likely to affect the balance.93 Immunoprecipitation of tagged Dicer followed by LC-MS/MS to determine interacting proteins, identified the direct interaction with TRBP, with or without viral infection, and a slew of other proteins that are significantly enriched in the presence of infection with either Sindbis virus or Semliki forest virus,93 including PKR, ADAR1, PACT, and DHX9.93 Treatment with ribonuclease confirmed that Dicer and TRBP interacted via a direct protein•protein interaction, while interactions of Dicer with PKR, PACT and DHX9 were almost completely lost after RNase treatment. Intriguingly, deletion of Dicer's helicase domain triggered a PKR dependent decrease in viral titer, suggesting that by sequestering PKR, the helicase domain prevented an antiviral response.

Competition is conserved

Observations of competition are not limited to mammalian cells. Like mammalian ADARs, ADARs from both C. elegans and D. melanogaster have editing independent effects.94-96 In C. elegans, deletion of the gene encoding the catalytically inactive ADAR homologue, ADR-1, causes accumulation of mature miRNAs and depletion of pri-miRNAs,94 consistent with the idea that ADR-1 competes with DROSHA for pri-miRNA binding to affect miRNA processing. Similarly, careful examination of the miR-376 cluster in human cell lines revealed that ADAR2 blocks pri-miRNA processing by DROSHA through its dsRNA binding ability.95 Similar observations have been made in human embryonic stem cells, where ADAR1 has an important role in suppressing processing of miR-302, which promotes stem cell self-renewal, by preventing processing of pri-miR-302 in an RNA-editing independent manner.97

Invertebrates lack a canonical IFN pathway, and it is Dicer that mediates antiviral defense. Yet, despite the differences between vertebrate and invertebrate immune responses, the role for ADARs in modulating the response is conserved. The invertebrate C. elegans triggers an antiviral RNAi response in the absence of its ADAR RNA editing enzyme.98 Similarly, in D. melanogaster, loss of A-to-I editing by Drosophila ADAR (a homologue of human ADAR2)99 causes an innate immune response.96 The aberrant immune response caused by depletion of Drosophila ADAR is rescued by overexpression of catalytically inactive ADAR, suggesting that RNA-editing independent roles for ADAR in suppression of dsRNA sensing have been conserved across species.

Foci and clusters

While the examples discussed so far address the competition that occurs after a change in the levels of dsRBPs, it is also important to consider what happens when levels of dsRNA increase. Recent studies show that introduction of dsRNA into the cytoplasm due to viral infection, expression from a reporter, during mitosis, or after knockdown of ADAR1, induces the formation of foci100 or clusters101 that are distinct from stress granules. Both recent studies show that the localization of proteins to these foci/clusters is dependent on dsRBDs, and when analyzed, the foci/clusters contain dsRNA. Together the studies indicate the foci/clusters contain PKR, ADAR1, PACT, STAU1, NLRP1 and DHX9 (Figure 1). The reports offer opposing speculations on function, proposing either that the foci/clusters contribute to PKR activation or that they are inhibitory to PKR activation.100,101 As described below, in our favorite model, PKR would be subject to substrate inhibition in foci/clusters.

A model

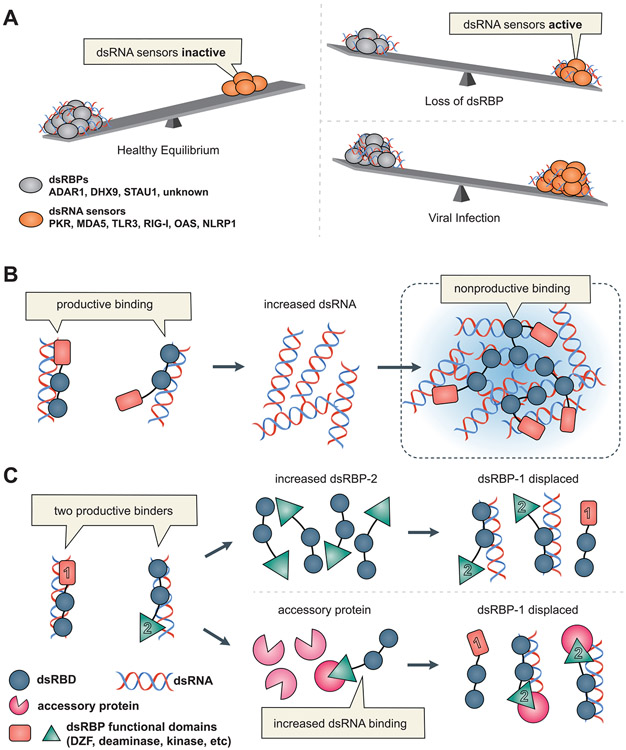

Regulation by competition mandates a fine balance between dsRNA and dsRBPs. Indeed, one wonders if the many repetitive elements retained in our genomes serve to express dsRNA that helps maintain this balance. Figure 2A illustrates how controlled balance between dsRBP expression and dsRNA abundance might determine whether or not dsRNA sensors involved in innate immunity are active. Under healthy conditions, cellular dsRBPs sequester dsRNA, and dsRNA sensors are inactive. The increased abundance of dsRNA that would accompany viral infection or stress, would shift the balance and allow activation of dsRNA sensors. This in turn would trigger an IFN response, leading to increased expression of dsRNA sensors and definitively tilting the balance to favor antiviral defense. Eventually this feedback loop would be broken when the abundance of dsRNA in the cytoplasm was reduced, either through degradation or editing by ADAR1. Finally, loss or reduced expression of an endogenous dsRBP could also allow binding and activation of innate immune dsRNA sensors. As discussed in the final section of this article, recent studies indicate changing the balance of cytoplasmic immunogenic dsRNA and dsRNA sensors in a controlled way is a promising therapeutic option for cancer.

Figure 2: A model for regulation by competition.

A) Balance between dsRNA sensors and dsRBPs. In a healthy cell (left), dsRNA sensors are expressed at low levels, but dsRBPs are prevalent and act to keep dsRNA sensors from being activated by dsRNA. dsRBPs can use different mechanisms to reduce the amount of immunogenic dsRNA available for interacting with dsRNA sensors, for example, they might edit, degrade or simply bind dsRNA. Upon loss of these dsRBPs (top right), or during a viral infection (bottom right) the concentration of dsRNA reaches a threshold that allows for dsRNA sensor activation. NLRP1, NLR family pyrin domain containing 1. B) Productive vs. nonproductive binding. Two dsRBPs are shown, each with two dsRBDs (blue) and a functional/catalytic domain (salmon). Productive binding involves each protein interacting with a single dsRNA; in one example the functional/catalytic domain also interacts with dsRNA, as would occur with an ADAR. In nonproductive binding a high concentration of dsRNA promotes dsRBD binding to different dsRNAs to form foci or clusters. C) Competitive binding dynamics. Two distinct dsRBPs, each with two dsRBDs (blue) and a single functional domain (dsRBP-1:salmon rectangle; dsRBP-2: green triangle), are first illustrated productively binding a single dsRNA. Next, dsRBP-2, with the help of accessory proteins (bottom) that confer a competitive edge (pink three-quarter circle), or increased concentration (top), displaces dsRBP-1, showcasing potential regulation of dsRBP functions through competition.

If one believes in a primordial RNA world,102 replication likely involved a dsRNA intermediate, and as proteins entered the scene, the competition began. Modern day solutions were built on a finely balanced interplay between dsRNA and dsRBPs. An advantage for extant immune pathways is that the system allows the cell to be ever ready to fight infection. dsRNA sensors can be expressed even in the presence of endogenous dsRNAs that could activate them, ready to come into play as the balance is tilted by high levels of viral dsRNA (Figure 2A). An interesting example of the importance of this balance can be seen in human neurons, which have unusually high levels of immunostimulatory dsRNA. Recent studies show that this is due to ELAVL RNA binding proteins that increase 3' UTR length, presumably to encompass addtional regions of dsRNA.80 The activation of dsRNA sensors in these cells is fine-tuned so as not to cause cell death, but high enough that the cell is primed to respond to viral infection. Shortening of 3' UTRs leads to reduced dsRNA sensor activation and susceptibility to viral infection. It is proposed that this exemplifies a situation whereby self dsRNAs are used to preemptively induce antiviral immunity to protect neuronal cells from viral infection. This example emphasizes the need to carefully evaluate different tissues to determine if there is a unique balance of dsRBPs and dsRNA tuned for the specific needs of the tissue.

There are many open questions in regard to how competition contributes to dsRNA sensing during an innate immune response, or in the natural regulation of dsRBP function. For instance, how many other dsRBPs compete with dsRNA sensors for binding to endogenous or foreign RNA? For each competing dsRBP found, it will be important to evaluate their substrate specificity and affinity for dsRNA binding, as well as their abundance in various cells and conditions. Some work has been done in this area; surprisingly the number of dsRBDs is thus far not predictive of affinity.103 Additionally, cooperative binding may influence competition between dsRBPs. Cataloging proteins capable of binding dsRNA is complicated by the fact that as yet, it is not clear that we understand all of the motifs that allow dsRNA binding, such as zinc finger domains and diverse helicases,17 hindering sequence similarity searches. While complex, identifying the dsRBPs that are capable of suppressing dsRNA sensing through competition, and gaining a mechanistic understanding of how this happens, may offer important, therapeutically-relevant insight into the innate response to viral infection and auto-immune disorders.

Intrinsic to the competition model is the dsRBD, which allows dsRBPs that contain this motif to bind in a sequence-independent manner to any dsRNA. Each motif encompasses ~16 base-pairs, interacting with ~1.5 helical turns of an A-form RNA duplex, and spanning two minor grooves and the intervening major groove;17 it is common to find multiple copies of the dsRBD in a dsRBP. In Figure 2B we go one step further in our competition model, illustrating that productive binding involves all dsRBDs of a given dsRBP interacting with a single dsRNA (Figure 2B, left), while nonproductive binding involves each dsRBD of a single protein interacting with different dsRNAs to create an interconnected network of dsRNA (Figure 2B, right). Nonproductive binding would be more likely at high concentrations of dsRNA, such as might occur within foci or clusters and has been used to explain the substrate inhibition that has long been known to occur with both ADARs104 and PKR105 at high concentrations of dsRNA; in this light, foci/clusters may be a means of inactivating the dsRBPs within them.

While existing examples are limited, an intriguing prediction of the model is that competition between dsRBDs could actually regulate, or switch, biological outcome. Figure 2C illustrates two dsRBD-containing proteins interacting with dsRNA in a productive manner, with each dsRBP including a third "functional" domain (labeled 1 and 2), that might comprise a catalytic domain such as a kinase or deaminase. Competition between such dsRBPs could actually switch which catalytic/functional domain was interacting with the dsRNA, and thus regulate biological outcome. In this scenario the competition of NF90/45 and STAU1/2 discussed above would be responsible for the regulation of mRNA degradation.

Looking towards the future: activation of dsRNA sensors as a therapy for cancer

An exciting and emerging twist to cancer therapeutics involves shifting the balance of immunogenic dsRNA in the cytoplasm to trigger an innate immune response, sometimes referred to as viral mimicry.106 Viral mimicry has great potential as a therapeutic approach for cancer, and in addition to cell intrinsic effects, can sometimes awaken the immune system to the presence of the tumor and promote anti-tumor immunity. For example, knockdown of ADAR1-p150 in tumor cells reduces editing of dsRNA, inducing interferon and sensitizing the tumors to immunotherapy.107

Given the above, it is not surprising that ADAR1-p150 is an essential gene in many cancer cell lines – including those derived from breast and lung.70-72 Depletion of ADAR1 in some cancer cell lines with elevated IFN signaling causes cell death. In ADAR1-dependent cells, following depletion of ADAR1 there is activation of the type I IFN pathway downstream of MDA5, and activation of PKR to drive translational repression.70-72 While for some cancer cells depletion of ADAR1 alone is sufficient to induce a viral mimicry phenotype, for other cells this does not occur. As discussed above, depletion of DHX9 in combination with ADAR1 can induce a viral mimicry phenotype. In this case, the loss of DHX9 and ADAR1 together is necessary to shift the balance of dsRBPs in the cell and enable activation of dsRNA sensors.

The same effect can be achieved by increasing the abundance of dsRNAs in the cell. Cells treated with the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor 5-AZA-CdR induce transcription of retroelements, including inverted SINEs, and thereby induce ADAR1-dependency.108 In some cell lines, DNMT inhibitors alone are sufficient to induce a viral mimicry phenotype through activation of dsRNA sensors.106,109 The same phenotype can be accomplished by depletion of epigenetic silencing complexes important for suppressing retroelement expression.110,111 Similarly, certain splicing inhibitors lead to export of unspliced transcripts that contain intronic dsRNA resulting in antiviral signaling and apoptosis,112 and likewise, disruption of splicing regulatory proteins can result in dsRNA accumulation and immunostimulatory phenotypes. For example, knockdown of proteins such as HNRPNM113 and HNRNPC114 results in unspliced mRNAs that are transported to the cytoplasm and induce an innate immune response. Decreasing the degradation of dsRNAs can also drive activation of dsRNA sensors, and depletion of RNA exonuclease XRN1 in cancer cell lines with elevated IFN signaling causes activation of PKR, MAVS, and cell death.115,116 Similarly, phosphorothioate DNA oligonucleotides, like those used in some FDA approved therapies, have been shown to prevent nuclear decay of intronic and intergenic retroelements leading to activation of PKR and OAS/RNase L.117

In each of the examples above, the balance between binding of dsRNA by dsRBPs and dsRNA sensors has been shifted towards the dsRNA sensors. As we have discussed above, this can occur through loss of dsRBPs, increased expression of dsRNA sensors, or increased dsRNA abundance. Disrupting this balance has great potential for cancer therapies, and potentially, antiviral therapies. Further, while we have focused on using viral mimicry to treat cancer, other therapeutic applications can be envisioned. The ELAVL proteins that increase immunogenic dsRNA in neurons could be expressed to increase dsRNA levels for cancer treatment, but also depleted to decrease dsRNA as a therapeutic means to treat neuroinflammatory disease.80 Therapies that shift the balance away from dsRNA sensors may be beneficial for many autoimmune disorders that arise from aberrant sensing of dsRNA.6

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding to K.A.C. from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R00MD016946) and to B.L.B from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM141262) and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA260414).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ehrenfeld E, and Hunt T (1971). Double-Stranded Poliovirus RNA Inhibits Initiation of Protein Synthesis by Reticulocyte Lysates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, 1075–1078. 10.1073/pnas.68.5.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt T, and Ehrenfeld E (1971). Cytoplasm from Poliovirus-infected HeLa Cells inhibits Cell-free Haemoglobin Synthesis. Nature New Biology 230, 91–94. 10.1038/newbio230091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter WA, and De Clercq E (1974). Viral infection and host defense. Science 186, 1172–1178. 10.1126/science.186.4170.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlee M, and Hartmann G (2016). Discriminating self from non-self in nucleic acid sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 566–580. 10.1038/nri.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehwinkel J, and Gack MU (2020). RIG-I-like receptors: their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 537–551. 10.1038/s41577-020-0288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YG, and Hur S (2022). Cellular origins of dsRNA, their recognition and consequences. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 286–301. 10.1038/s41580-021-00430-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett KC, Li S, Liang K, and Ting JP (2023). A 360 degrees view of the inflammasome: Mechanisms of activation, cell death, and diseases. Cell 186, 2288–2312. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whipple JM, Youssef OA, Aruscavage PJ, Nix DA, Hong C, Johnson WE, and Bass BL (2015). Genome-wide profiling of the C. elegans dsRNAome. RNA 21, 786–800. 10.1261/rna.048801.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blango MG, and Bass BL (2016). Identification of the long, edited dsRNAome of LPS-stimulated immune cells. Genome Res 26, 852–862. 10.1101/gr.203992.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sommer B, Kohler M, Sprengel R, and Seeburg PH (1991). RNA editing in brain controls a determinant of ion flow in glutamate-gated channels. Cell 67, 11–19. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90568-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morse DP, and Bass BL (1999). Long RNA hairpins that contain inosine are present in Caenorhabditis elegans poly(A)+ RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 6048–6053. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morse DP, Aruscavage PJ, and Bass BL (2002). RNA hairpins in noncoding regions of human brain and Caenorhabditis elegans mRNA are edited by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 7906–7911. 10.1073/pnas.112704299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenberg E, Li JB, and Levanon EY (2010). Sequence based identification of RNA editing sites. RNA Biol 7, 248–252. 10.4161/rna.7.2.11565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramaswami G, and Li JB (2016). Identification of human RNA editing sites: A historical perspective. Methods 107, 42–47. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich DP, and Bass BL (2019). Mapping the dsRNA World. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 11. 10.1101/cshperspect.a035352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaffer AA, and Levanon EY (2021). ALU A-to-I RNA Editing: Millions of Sites and Many Open Questions. In Methods in Molecular Biology, (Springer US; ), pp. 149–162. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0787-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian B, Bevilacqua PC, Diegelman-Parente A, and Mathews MB (2004). The double-stranded-RNA-binding motif: interference and much more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5, 1013–1023. 10.1038/nrm1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masliah G, Barraud P, and Allain FH (2013). RNA recognition by double-stranded RNA binding domains: a matter of shape and sequence. Cell Mol Life Sci 70, 1875–1895. 10.1007/s00018-012-1119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsiao YE, Bahn JH, Yang Y, Lin X, Tran S, Yang EW, Quinones-Valdez G, and Xiao X (2018). RNA editing in nascent RNA affects pre-mRNA splicing. Genome Res 28, 812–823. 10.1101/gr.231209.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bentley DL (2014). Coupling mRNA processing with transcription in time and space. Nat Rev Genet 15, 163–175. 10.1038/nrg3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quin J, Sedmik J, Vukic D, Khan A, Keegan LP, and O'Connell MA (2021). ADAR RNA Modifications, the Epitranscriptome and Innate Immunity. Trends Biochem Sci 46, 758–771. 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritz J, Strehblow A, Taschner A, Schopoff S, Pasierbek P, and Jantsch MF (2009). RNA-regulated interaction of transportin-1 and exportin-5 with the double-stranded RNA-binding domain regulates nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of ADAR1. Mol Cell Biol 29, 1487–1497. 10.1128/MCB.01519-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinova R, Rajendra V, Leuchtenberger AF, Lo Giudice C, Vesely C, Kapoor U, Tanzer A, Derdak S, Picardi E, and Jantsch MF (2023). The ADAR1 editome reveals drivers of editing-specificity for ADAR1-isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res 51, 4191–4207. 10.1093/nar/gkad265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JI, Nakahama T, Yamasaki R, Costa Cruz PH, Vongpipatana T, Inoue M, Kanou N, Xing Y, Todo H, Shibuya T, Kato Y, and Kawahara Y (2021). RNA editing at a limited number of sites is sufficient to prevent MDA5 activation in the mouse brain. PLoS Genet 17, e1009516. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez NM, Su A, Burns MC, Nussbacher JK, Schaening C, Sathe S, Yeo GW, and Gilbert WV (2022). Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing. Mol Cell 82, 645–659 e649. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun H, Li K, Liu C, and Yi C (2023). Regulation and functions of non-m(6)A mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24, 714–731. 10.1038/s41580-023-00622-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke S, Pandya-Jones A, Saito Y, Fak JJ, Vagbo CB, Geula S, Hanna JH, Black DL, Darnell JE Jr., and Darnell RB (2017). m(6)A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev 31, 990–1006. 10.1101/gad.301036.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Pan Z, Adhikari S, Harada BT, Shen L, Yuan W, Abeywardana T, Al-Hadid Q, Stark JM, He C, Lin L, and Yang Y (2021). m(6) A deposition is regulated by PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation of METTL14 in its disordered C-terminal region. EMBO J 40, e106309. 10.15252/embj.2020106309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang H, Weng H, Zhou K, Wu T, Zhao BS, Sun M, Chen Z, Deng X, Xiao G, Auer F, et al. (2019). Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m(6)A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature 567, 414–419. 10.1038/s41586-019-1016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, Vasic R, Song Y, Teng R, Liu C, Gbyli R, Biancon G, Nelakanti R, Lobben K, Kudo E, et al. (2020). m(6)A Modification Prevents Formation of Endogenous Double-Stranded RNAs and Deleterious Innate Immune Responses during Hematopoietic Development. Immunity 52, 1007–1021 e1008. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nance KD, and Meier JL (2021). Modifications in an Emergency: The Role of N1-Methylpseudouridine in COVID-19 Vaccines. ACS Cent Sci 7, 748–756. 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson J, Sorensen EW, Mintri S, Rabideau AE, Zheng W, Besin G, Khatwani N, Su SV, Miracco EJ, Issa WJ, et al. (2020). Impact of mRNA chemistry and manufacturing process on innate immune activation. Science Advances 6, eaaz6893. 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, and Weissman D (2005). Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23, 165–175. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg G, Dienemann C, Farnung L, Schwarz J, Linden A, Urlaub H, and Cramer P (2023). Structural insights into human co-transcriptional capping. Mol Cell 83, 2464–2477 e2465. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devarkar SC, Wang C, Miller MT, Ramanathan A, Jiang F, Khan AG, Patel SS, and Marcotrigiano J (2016). Structural basis for m7G recognition and 2'-O-methyl discrimination in capped RNAs by the innate immune receptor RIG-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 596–601. 10.1073/pnas.1515152113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholson AW (2014). Ribonuclease III mechanisms of double-stranded RNA cleavage. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 5, 31–48. 10.1002/wrna.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burger K, and Gullerova M (2015). Swiss army knives: non-canonical functions of nuclear Drosha and Dicer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16, 417–430. 10.1038/nrm3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White E, Schlackow M, Kamieniarz-Gdula K, Proudfoot NJ, and Gullerova M (2014). Human nuclear Dicer restricts the deleterious accumulation of endogenous double-stranded RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 552–559. 10.1038/nsmb.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim B, Jeong K, and Kim VN (2017). Genome-wide Mapping of DROSHA Cleavage Sites on Primary MicroRNAs and Noncanonical Substrates. Mol Cell 66, 258–269 e255. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lingaraju M, Schuller JM, Falk S, Gerlach P, Bonneau F, Basquin J, Benda C, and Conti E (2019). To Process or to Decay: A Mechanistic View of the Nuclear RNA Exosome. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 84, 155–163. 10.1101/sqb.2019.84.040295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weick EM, and Lima CD (2021). RNA helicases are hubs that orchestrate exosome-dependent 3'-5' decay. Curr Opin Struct Biol 67, 86–94. 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macias S, Cordiner RA, Gautier P, Plass M, and Caceres JF (2015). DGCR8 Acts as an Adaptor for the Exosome Complex to Degrade Double-Stranded Structured RNAs. Mol Cell 60, 873–885. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z, and Carmichael GG (2001). The fate of dsRNA in the nucleus: a p54(nrb)-containing complex mediates the nuclear retention of promiscuously A-to-I edited RNAs. Cell 106, 465–475. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar M, and Carmichael GG (1997). Nuclear antisense RNA induces extensive adenosine modifications and nuclear retention of target transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 3542–3547. 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hundley HA, Krauchuk AA, and Bass BL (2008). C. elegans and H. sapiens mRNAs with edited 3' UTRs are present on polysomes. RNA 14, 2050–2060. 10.1261/rna.1165008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCluggage F, and Fox AH (2021). Paraspeckle nuclear condensates: Global sensors of cell stress? Bioessays 43, e2000245. 10.1002/bies.202000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox AH, Nakagawa S, Hirose T, and Bond CS (2018). Paraspeckles: Where Long Noncoding RNA Meets Phase Separation. Trends Biochem Sci 43, 124–135. 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu SB, Xiang JF, Li X, Xu Y, Xue W, Huang M, Wong CC, Sagum CA, Bedford MT, Yang L, Cheng D, and Chen LL (2015). Protein arginine methyltransferase CARM1 attenuates the paraspeckle-mediated nuclear retention of mRNAs containing IRAlus. Genes Dev 29, 630–645. 10.1101/gad.257048.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elbarbary RA, Li W, Tian B, and Maquat LE (2013). STAU1 binding 3' UTR IRAlus complements nuclear retention to protect cells from PKR-mediated translational shutdown. Genes Dev 27, 1495–1510. 10.1101/gad.220962.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen LL, DeCerbo JN, and Carmichael GG (2008). Alu element-mediated gene silencing. EMBO J 27, 1694–1705. 10.1038/emboj.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khan M, Hou S, Chen M, and Lei H (2023). Mechanisms of RNA export and nuclear retention. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 14, e1755. 10.1002/wrna.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, and Kutay U (2004). Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science 303, 95–98. 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brownawell AM, and Macara IG (2002). Exportin-5, a novel karyopherin, mediates nuclear export of double-stranded RNA binding proteins. J Cell Biol 156, 53–64. 10.1083/jcb.200110082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim Y, Lee JH, Park JE, Cho J, Yi H, and Kim VN (2014). PKR is activated by cellular dsRNAs during mitosis and acts as a mitotic regulator. Genes Dev 28, 1310–1322. 10.1101/gad.242644.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burke JM, Gilchrist AR, Sawyer SL, and Parker R (2021). RNase L limits host and viral protein synthesis via inhibition of mRNA export. Sci Adv 7. 10.1126/sciadv.abh2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burger K, Schlackow M, Potts M, Hester S, Mohammed S, and Gullerova M (2017). Nuclear phosphorylated Dicer processes double-stranded RNA in response to DNA damage. J Cell Biol 216, 2373–2389. 10.1083/jcb.201612131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim MS, Pinto SM, Getnet D, Nirujogi RS, Manda SS, Chaerkady R, Madugundu AK, Kelkar DS, Isserlin R, Jain S, et al. (2014). A draft map of the human proteome. Nature 509, 575–581. 10.1038/nature13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moreno P, Fexova S, George N, Manning JR, Miao Z, Mohammed S, Munoz-Pomer A, Fullgrabe A, Bi Y, Bush N, et al. (2022). Expression Atlas update: gene and protein expression in multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D129–D140. 10.1093/nar/gkab1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee HY, Zhou K, Smith AM, Noland CL, and Doudna JA (2013). Differential roles of human Dicer-binding proteins TRBP and PACT in small RNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 6568–6576. 10.1093/nar/gkt361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ha M, and Kim VN (2014). Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 509–524. 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim YK, and Maquat LE (2019). UPFront and center in RNA decay: UPF1 in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and beyond. RNA 25, 407–422. 10.1261/rna.070136.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim YK, Furic L, Parisien M, Major F, DesGroseillers L, and Maquat LE (2007). Staufen1 regulates diverse classes of mammalian transcripts. EMBO J 26, 2670–2681. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gong C, and Maquat LE (2011). lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3' UTRs via Alu elements. Nature 470, 284–288. 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ricci EP, Kucukural A, Cenik C, Mercier BC, Singh G, Heyer EE, Ashar-Patel A, Peng L, and Moore MJ (2014). Staufen1 senses overall transcript secondary structure to regulate translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 26–35. 10.1038/nsmb.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liddicoat BJ, Piskol R, Chalk AM, Ramaswami G, Higuchi M, Hartner JC, Li JB, Seeburg PH, and Walkley CR (2015). RNA editing by ADAR1 prevents MDA5 sensing of endogenous dsRNA as nonself. Science 349, 1115–1120. 10.1126/science.aac7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.George CX, Ramaswami G, Li JB, and Samuel CE (2016). Editing of Cellular Self-RNAs by Adenosine Deaminase ADAR1 Suppresses Innate Immune Stress Responses. J Biol Chem 291, 6158–6168. 10.1074/jbc.M115.709014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pestal K, Funk CC, Snyder JM, Price ND, Treuting PM, and Stetson DB (2015). Isoforms of RNA-Editing Enzyme ADAR1 Independently Control Nucleic Acid Sensor MDA5-Driven Autoimmunity and Multi-organ Development. Immunity 43, 933–944. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, Cox S, Brindle J, Read D, Nellaker C, Vesely C, Ponting CP, McLaughlin PJ, et al. (2014). The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 controls innate immune responses to RNA. Cell Rep 9, 1482–1494. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chung H, Calis JJA, Wu X, Sun T, Yu Y, Sarbanes SL, Dao Thi VL, Shilvock AR, Hoffmann HH, Rosenberg BR, and Rice CM (2018). Human ADAR1 Prevents Endogenous RNA from Triggering Translational Shutdown. Cell 172, 811–824 e814. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kung CP, Cottrell KA, Ryu S, Bramel ER, Kladney RD, Bao EA, Freeman EC, Sabloak T, Maggi L Jr., and Weber JD (2021). Evaluating the therapeutic potential of ADAR1 inhibition for triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene 40, 189–202. 10.1038/s41388-020-01515-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gannon HS, Zou T, Kiessling MK, Gao GF, Cai D, Choi PS, Ivan AP, Buchumenski I, Berger AC, Goldstein JT, et al. (2018). Identification of ADAR1 adenosine deaminase dependency in a subset of cancer cells. Nat Commun 9, 5450. 10.1038/s41467-018-07824-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu H, Golji J, Brodeur LK, Chung FS, Chen JT, deBeaumont RS, Bullock CP, Jones MD, Kerr G, Li L, et al. (2019). Tumor-derived IFN triggers chronic pathway agonism and sensitivity to ADAR loss. Nat Med 25, 95–102. 10.1038/s41591-018-0302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maurano M, Snyder JM, Connelly C, Henao-Mejia J, Sidrauski C, and Stetson DB (2021). Protein kinase R and the integrated stress response drive immunopathology caused by mutations in the RNA deaminase ADAR1. Immunity 54, 1948–1960 e1945. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pfaller CK, Donohue RC, Nersisyan S, Brodsky L, and Cattaneo R (2018). Extensive editing of cellular and viral double-stranded RNA structures accounts for innate immunity suppression and the proviral activity of ADAR1p150. PLoS Biol 16, e2006577. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ahmad S, Mu X, Yang F, Greenwald E, Park JW, Jacob E, Zhang CZ, and Hur S (2018). Breaching Self-Tolerance to Alu Duplex RNA Underlies MDA5-Mediated Inflammation. Cell 172, 797–810 e713. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barak M, Porath HT, Finkelstein G, Knisbacher BA, Buchumenski I, Roth SH, Levanon EY, and Eisenberg E (2020). Purifying selection of long dsRNA is the first line of defense against false activation of innate immunity. Genome Biol 21, 26. 10.1186/s13059-020-1937-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun T, Li Q, Geisinger JM, Hu S-B, Fan B, Su S, Tsui W, Guo H, Ma J, and Li JB (2022). A Small Subset of Cytosolic dsRNAs Must Be Edited by ADAR1 to Evade MDA5-Mediated Autoimmunity. bioRxiv 2022.08.29.505707. 10.1101/2022.08.29.505707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim Y, Park J, Kim S, Kim M, Kang MG, Kwak C, Kang M, Kim B, Rhee HW, and Kim VN (2018). PKR Senses Nuclear and Mitochondrial Signals by Interacting with Endogenous Double-Stranded RNAs. Mol Cell 71, 1051–1063 e1056. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Young PG, and Attardi G (1975). Characterization of double-stranded RNA from HeLa cell mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 65, 1201–1207. 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dorrity TJ, Shin H, Wiegand KA, Aruda J, Closser M, Jung E, Gertie JA, Leone A, Polfer R, Culbertson B, et al. (2023). Long 3'UTRs predispose neurons to inflammation by promoting immunostimulatory double-stranded RNA formation. Sci Immunol 8, eadg2979. 10.1126/sciimmunol.adg2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Langland JO, Cameron JM, Heck MC, Jancovich JK, and Jacobs BL (2006). Inhibition of PKR by RNA and DNA viruses. Virus Res 119, 100–110. 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zinzula L, and Tramontano E (2013). Strategies of highly pathogenic RNA viruses to block dsRNA detection by RIG-I-like receptors: hide, mask, hit. Antiviral Res 100, 615–635. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li WX, and Ding SW (2022). Mammalian viral suppressors of RNA interference. Trends Biochem Sci 47, 978–988. 10.1016/j.tibs.2022.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ye C, Jia L, Sun Y, Hu B, Wang L, Lu X, and Zhou J (2014). Inhibition of antiviral innate immunity by birnavirus VP3 protein via blockage of viral double-stranded RNA binding to the host cytoplasmic RNA detector MDA5. J Virol 88, 11154–11165. 10.1128/JVI.01115-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu Z, Wang J, Cheng H, Ke X, Sun L, Zhang QC, and Wang HW (2018). Cryo-EM Structure of Human Dicer and Its Complexes with a Pre-miRNA Substrate. Cell 173, 1191–1203 e1112. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Motz C, Schuhmann KM, Kirchhofer A, Moldt M, Witte G, Conzelmann KK, and Hopfner KP (2013). Paramyxovirus V proteins disrupt the fold of the RNA sensor MDA5 to inhibit antiviral signaling. Science 339, 690–693. 10.1126/science.1230949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hu SB, Heraud-Farlow J, Sun T, Liang Z, Goradia A, Taylor S, Walkley CR, and Li JB (2023). ADAR1p150 prevents MDA5 and PKR activation via distinct mechanisms to avert fatal autoinflammation. Mol Cell. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sakurai M, Shiromoto Y, Ota H, Song C, Kossenkov AV, Wickramasinghe J, Showe LC, Skordalakes E, Tang HY, Speicher DW, and Nishikura K (2017). ADAR1 controls apoptosis of stressed cells by inhibiting Staufen1-mediated mRNA decay. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24, 534–543. 10.1038/nsmb.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cottrell KA, Ryu S, Torres LS, Schab AM, and Weber JD (2023). Induction of viral mimicry upon loss of DHX9 and ADAR1 in breast cancer cells. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2023.02.27.530307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nourreddine S, Lavoie G, Paradis J, Ben El Kadhi K, Meant A, Aubert L, Grondin B, Gendron P, Chabot B, Bouvier M, Carreno S, and Roux PP (2020). NF45 and NF90 Regulate Mitotic Gene Expression by Competing with Staufen-Mediated mRNA Decay. Cell Rep 31, 107660. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schmidt T, Knick P, Lilie H, Friedrich S, Golbik RP, and Behrens SE (2017). The properties of the RNA-binding protein NF90 are considerably modulated by complex formation with NF45. Biochem J 474, 259–280. 10.1042/BCJ20160790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ota H, Sakurai M, Gupta R, Valente L, Wulff BE, Ariyoshi K, lizasa H, Davuluri RV, and Nishikura K (2013). ADAR1 forms a complex with Dicer to promote microRNA processing and RNA-induced gene silencing. Cell 153, 575–589. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Montavon TC, Baldaccini M, Lefevre M, Girardi E, Chane-Woon-Ming B, Messmer M, Hammann P, Chicher J, and Pfeffer S (2021). Human DICER helicase domain recruits PKR and modulates its antiviral activity. PLoS Pathog 17, e1009549. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Warf MB, Shepherd BA, Johnson WE, and Bass BL (2012). Effects of ADARs on small RNA processing pathways in C. elegans. Genome Res 22, 1488–1498. 10.1101/gr.134841.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Heale BS, Keegan LP, McGurk L, Michlewski G, Brindle J, Stanton CM, Caceres JF, and O'Connell MA (2009). Editing independent effects of ADARs on the miRNA/siRNA pathways. EMBO J 28, 3145–3156. 10.1038/emboj.2009.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Deng P, Khan A, Jacobson D, Sambrani N, McGurk L, Li X, Jayasree A, Hejatko J, Shohat-Ophir G, O'Connell MA, Li JB, and Keegan LP (2020). Adar RNA editing-dependent and - independent effects are required for brain and innate immune functions in Drosophila. Nat Commun 11, 1580. 10.1038/s41467-020-15435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen T, Xiang JF, Zhu S, Chen S, Yin QF, Zhang XO, Zhang J, Feng H, Dong R, Li XJ, Yang L, and Chen LL (2015). ADAR1 is required for differentiation and neural induction by regulating microRNA processing in a catalytically independent manner. Cell Res 25, 459–476. 10.1038/cr.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Reich DP, Tyc KM, and Bass BL (2018). C. elegans ADARs antagonize silencing of cellular dsRNAs by the antiviral RNAi pathway. Genes Dev 32, 271–282. 10.1101/gad.310672.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Keegan LP, McGurk L, Palavicini JP, Brindle J, Paro S, Li X, Rosenthal JJ, and O'Connell MA (2011). Functional conservation in human and Drosophila of Metazoan ADAR2 involved in RNA editing: loss of ADAR1 in insects. Nucleic Acids Res 39, 7249–7262. 10.1093/nar/gkr423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Corbet GA, Burke JM, Bublitz GR, Tay JW, and Parker R (2022). dsRNA-induced condensation of antiviral proteins modulates PKR activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119, e2204235119. 10.1073/pnas.2204235119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zappa F, Muniozguren NL, Wilson MZ, Costello MS, Ponce-Rojas JC, and Acosta-Alvear D (2022). Signaling by the integrated stress response kinase PKR is fine-tuned by dynamic clustering. J Cell Biol 221. 10.1083/jcb.202111100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Joyce GF, and Szostak JW (2018). Protocells and RNA Self-Replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10. 10.1101/cshperspect.a034801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang X, Vukovic L, Koh HR, Schulten K, and Myong S (2015). Dynamic profiling of double-stranded RNA binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 43, 7566–7576. 10.1093/nar/gkv726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Plough RF, and Bass BL (1994). Purification of the Xenopus laevis double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase. J Biol Chem 269, 9933–9939. 10.1016/s0021-9258(17)36972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kostura M, and Mathews MB (1989). Purification and activation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent eIF-2 kinase DAI. Mol Cell Biol 9, 1576–1586. 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1576-1586.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R, Wang Y, Danesh A, Shen SY, Han H, Liang G, Jones PA, Pugh TJ, O'Brien C, and De Carvalho DD (2015). DNA-Demethylating Agents Target Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inducing Viral Mimicry by Endogenous Transcripts. Cell 162, 961–973. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ishizuka JJ, Manguso RT, Cheruiyot CK, Bi K, Panda A, Iracheta-Vellve A, Miller BC, Du PP, Yates KB, Dubrot J, et al. (2019). Loss of ADAR1 in tumours overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature 565, 43–48. 10.1038/s41586-018-0768-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mehdipour P, Marhon SA, Ettayebi I, Chakravarthy A, Hosseini A, Wang Y, de Castro FA, Loo Yau H, Ishak C, Abelson S, O'Brien CA, and De Carvalho DD (2020). Epigenetic therapy induces transcription of inverted SINEs and ADAR1 dependency. Nature 588, 169–173. 10.1038/s41586-020-2844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A, Li H, Henke C, Akman B, Hein A, Rote NS, Cope LM, Snyder A, et al. (2015). Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell 162, 974–986. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cuellar TL, Herzner AM, Zhang X, Goyal Y, Watanabe C, Friedman BA, Janakiraman V, Durinck S, Stinson J, Arnott D, et al. (2017). Silencing of retrotransposons by SETDB1 inhibits the interferon response in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cell Biol 216, 3535–3549. 10.1083/jcb.201612160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tunbak H, Enriquez-Gasca R, Tie CHC, Gould PA, Mlcochova P, Gupta RK, Fernandes L, Holt J, van der Veen AG, Giampazolias E, et al. (2020). The HUSH complex is a gatekeeper of type I interferon through epigenetic regulation of LINE-1s. Nat Commun 11, 5387. 10.1038/s41467-020-19170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bowling EA, Wang JH, Gong F, Wu W, Neill NJ, Kim IS, Tyagi S, Orellana M, Kurley SJ, Dominguez-Vidana R, et al. (2021). Spliceosome-targeted therapies trigger an antiviral immune response in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell 184, 384–403 e321. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zheng R, Dunlap M, Lyu J, Gonzalez-Figueroa C, Bobkov G, Harvey SE, Chan TW, Quinones-Valdez G, Choudhury M, Vuong A, et al. (2023). LINE-associated cryptic splicing induces dsRNA-mediated interferon response and tumor immunity. bioRxiv 2023.02.23.529804; doi: 10.1101/2023.02.23.529804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wu Y, Zhao W, Liu Y, Tan X, Li X, Zou Q Xiao Z, Xu H, Wang Y, and Yang X (2018). Function of HNRNPC in breast cancer cells by controlling the dsRNA-induced interferon response. The EMBO Journal 37, e99017. 10.15252/embj.201899017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zou T, Zhou M, Gupta A, Zhuang P, Fishbein AR, Wei HY, Zhang Z, Cherniack AD, and Meyerson M (2023). XRN1 deletion induces PKR-dependent cell lethality in interferon-activated cancer cells. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2023.08.01.551488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hosseini A, Lindholm HT, Chen R, Mehdipour P, Marhon SA, Ishak CA, and De Carvalho DD (2023). Retroelement decay by the exonuclease XRN1 is a viral mimicry dependency in cancer. BioRxiv. 10.1101/2023.03.30.531699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chitrakar A, Solorio-Kirpichyan K, Prangley E, Rath S, Du J, and Korennykh A (2021). Introns encode dsRNAs undetected by RIG-I/MDA5/interferons and sensed via RNase L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, e2102134118. 10.1073/pnas.2102134118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hur S. (2019). Double-Stranded RNA Sensors and Modulators in Innate Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 37, 349–375. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ahmad S, and Hur S (2015). Helicases in Antiviral Immunity: Dual Properties as Sensors and Effectors. Trends Biochem Sci 40, 576–585. 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Peisley A, Lin C, Wu B, Orme-Johnson M, Liu M, Walz T, and Hur S (2011). Cooperative assembly and dynamic disassembly of MDA5 filaments for viral dsRNA recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 21010–21015. 10.1073/pnas.1113651108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Duic I, Tadakuma H, Harada Y, Yamaue R, Deguchi K, Suzuki Y, Yoshimura SH, Kato H, Takeyasu K, and Fujita T (2020). Viral RNA recognition by LGP2 and MDA5, and activation of signaling through step-by-step conformational changes. Nucleic Acids Res 48, 11664–11674. 10.1093/nar/gkaa935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]