Abstract

Background

Abnormal orthostatic blood pressure (BP) regulation may result in cerebral hypoperfusion and brain ischemia and contribute to dementia. It may also manifest as early symptoms of the neurodegenerative process associated with dementia. The relationship between the magnitude and timing of orthostatic BP responses and dementia risk is not fully understood.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort analysis of the associations of orthostatic BP changes and self-reported orthostatic dizziness with the risk of dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. We calculated changes in BP from the supine to the standing position at five measurements taken within 2 minutes after standing during the baseline visit (1987–1989). The primary outcome was adjudicated dementia ascertained through 2019.

Results

Among 11,644 participants (mean [SD] age, 54.5 [5.7] years; 54.1% women; 25.9% Black), 2,303 dementia cases were identified during a median follow-up of 25.9 years. Large decreases in systolic BP (SBP) from the supine-to-standing position measured at the first two measurements approximately 30 and 50 seconds after standing, but not afterward, were associated with orthostatic dizziness and a higher risk of dementia. Comparing a decrease in SBP of ≤−20 or >−20 to −10 mmHg to stable SBP (>−10 to 10 mmHg) at the first measurement, the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) were 1.22 (95%CI: 1.01–1.47) and 1.10 (95%CI: 0.97–1.25) respectively.

Conclusions

Abnormal orthostatic BP regulation, especially abrupt drops in BP within the first minute, might be early risk markers for the development of dementia. Transient early orthostatic hypotension warrants more attention in clinical settings.

Keywords: Orthostatic Hypotension, Hypertension, Blood Pressure, Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, Brain Health, Community-based cohort

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Measuring orthostatic blood pressure (BP) is important for assessing autonomic dysfunction and impaired baroreflex sensitivity. Orthostatic hypotension is frequently observed in older adults, especially individuals with frailty and hypertension.1 Epidemiological studies have linked orthostatic hypotension to a higher risk of cardiovascular events, syncope, falls, and death.1,2 In several prospective cohort studies, including the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, orthostatic hypotension was also associated with cognitive decline and a higher risk of dementia.3–8

Increasing evidence suggests that the presence or absence of orthostatic hypotension may not fully capture the clinical relevance of BP regulation during the first few minutes of postural change. In the first 30–60 seconds after the postural change, BP may sharply drop due to reduced ventricular filling and cardiac output.9 Those with intact cerebral autoregulation can maintain stable cerebral blood flow regardless of the sudden BP drop,10 but those with cerebral autoregulation dysfunction may be at risk of cerebral hypoperfusion hypoxia, brain ischemia and thus dementia, particularly older adults and those with hypertension.11,12 after the initial 60 seconds, the body activates compensatory mechanisms to restore cardiac output and BP. However, those with deficient compensatory mechanisms, such as autonomic dysfunction associated with neurodegenerative processes before dementia diagnosis, may experience failed BP restoration (orthostatic hypotension) or overcompensation (orthostatic hypertension). 1,13 Different stages of orthostatic BP assessment likely involve various regulatory mechanisms. We hypothesized that orthostatic BP changes at an early stage after standing (representing abrupt hypotensive stress) are more relevant for dementia risk compared with orthostatic BP changes at a later stage (reflecting dysfunctional compensatory mechanisms). This study aims to examine the association of orthostatic BP changes assessed at five-time points after standing with risk of dementia in a community-based population.

Methods

The study was approved by each institution’s institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at each visit or from a designated proxy with participant assent if the participant was unable to provide consent. Requests to access the data sets from researchers trained in human subject confidentiality may be sent to ARICpub@unc.edu.

Study Population

The ARIC Study is an ongoing, community-based cohort in which 15,792 men and women aged 45–64 years from four US communities (Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; Minneapolis, Minnesota) underwent baseline assessments (Visit 1) between 1987 and 1989.14 Participants were followed up through telephone interviews (annually and then semiannually since 2012) and in-person examinations at visit 2 (1990–1992), visit 3 (1993–1995), visit 4 (1996–1998), and visits 5–9 as part of the ARIC Neurocognitive Study. In the current study, we excluded participants with no available orthostatic BP measurements (n=2,582), less than 4 out of 5 standing BP measurements (n=1,255), dementia diagnosis within one year of baseline (n=3), prior diagnosis of stroke (n=245), or taking antiparkinsonian drugs (n=24). We also excluded Black participants from the two sites in Washington County, MD, and Minneapolis, MN, and participants who were neither White nor Black due to small numbers (n=39). Ultimately, 11,644 participants were included (Supplemental Figure S1). Compared to excluded participants, participants in the current study were younger and overall healthier (Supplemental Table S1).

Orthostatic Blood Pressure Assessment

During the baseline visit, supine and standing BP measurements were obtained by a Dinamap 1846 SX oscillometric device using an automatic cuff after participants had 20 minutes of supine rest.15,16 The device was programmed to record up to 5 BP measurements automatically approximately every 20–30 seconds while a participant was lying during the 2 minutes preceding the standing phase of the protocol and during the first 2 minutes after standing (at ~30s, 50s, 75s, 100s, and 115s after standing, range, 2–5 measurements with 91% having at least 4 measurements). Participants were then asked if they felt dizzy immediately after standing. Further details are described in the Online Supplement and elsewhere.16

Dementia Ascertainment

Our primary outcome was incident dementia identified throughout the follow-up period (1987–2019) with detailed methods described elsewhere.17 Dementia cases were ascertained based on expert adjudication using data that incorporated retrospective longitudinal cognitive data and a complete neuropsychological battery administered at Visits 5–7.18 All participants seen at Visits 5–7 completed an extensive neuropsychological battery; participants who did not attend the clinical exam and who agreed to a telephone interview were assessed using Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status–Modified (TICSm). A more detailed assessment was conducted on participants with suspected cognitive impairment and in a random sample consisting of 10% of those without cognitive decline or suspected impairment. This included an informant interview using the modified Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)19 and the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ).20 Participants seen in person at these visits were identified as mild cognitive impairment or dementia based on a computer algorithm with subsequent expert adjudication using the full history of neuropsychological testing plus these informant interviews.18 For individuals who did not attend one of the in-person visits, additional dementia cases were ascertained using the TICSm,21 CDR, and FAQ at Visit 5, and the Eight-item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia (AD-8) and Six-Item Screener (SIS) administered annually between Visits 5 and 7.22 Cases were also ascertained by surveillance based on a discharge hospitalization ICD-9 or death certificate code from the date of the last participant contact up to administrative censoring on December 31, 2019 (2017 in Jackson). The date of dementia diagnosis corresponded to the earliest date that dementia was detected and for dementia diagnosed through informant interviews, hospitalization, and death certificates, a 6-month lead time was given to estimate the date of onset.23

Covariate Assessment

Age, sex, race, attained education, smoking status, and alcohol consumption status were self-reported at baseline. APOE genotype (TaqMan assay; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was classified based on the number of ε4 alleles. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Sitting BP at baseline was also taken with three repeated readings and the average of the last two readings was used for covariate adjustment. Plasma total cholesterol was measured using enzymatic methods.24 Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level of at least 126 mg/dL, nonfasting glucose of at least 200 mg/dL, self-report of physician-diagnosed diabetes, or use of oral diabetes medications or insulin. History of coronary heart disease assessed at baseline was defined based on self-reported history of a physician-diagnosed heart attack, cardiovascular surgery or coronary angioplasty and evidence of a prior myocardial infarction assessed by electrocardiogram.25

Statistical analyses

Our primary exposures were changes in BP from the supine to standing position at each of the five time points after standing. Orthostatic BP changes were assessed as both continuous and categorical variables and for systolic and diastolic BP. The categories for orthostatic SBP change (standing minus supine) were ≤−20, >−20 to ≤−10, >−10 to ≤10, >10 to ≤20, and >20 mm Hg and those for orthostatic DBP change were ≤−10, >−10 to ≤−5, >−5 to ≤5, >5 to ≤10 and >10 mmHg. To allow for the comparison of the results in clinical settings, we also assessed orthostatic hypotension (OH) at each of the five individual points using the consensus defintion of a decrease in SBP or DBP of at least 20 or 10 mmHg, respectively.26 To assess OH patterns over time, we further classified OH as initial OH (transient OH at the first 2 measurements during the first minute of standing), subsequent OH (delayed OH at the 3–5 measurements during the second minute), and sustained OH (during both the first and second minutes of standing).

We described the trajectory and rate of orthostatic BP changes from supine to standing position within the first 2 minutes of standing by building mixed models with piecewise cubic spline functions using orthostatic changes in BP measured at five individual time points approximately 30, 50, 75, 100 and 115 seconds upon standing. In light of previous reports on the significant relevance of orthostatic dizziness,16 dynamic BP patterns were stratified by self-reported orthostatic dizziness upon standing. Out of the 11,644 participants included in the analyses, 7,470 participants had five complete standing BP measurements and 4,174 had four standing BP measurements. Participants who completed all five standing BP measurements appeared to be slightly younger and healthier (Supplemental Table S2).

In primary analyses, we assessed the association of postural BP changes with risk of dementia using Cox proportional-hazards models, where postural BP changes at the five individual time points were analyzed in separate models. Person-time was calculated from baseline until the date of dementia diagnosis or death or the end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. Cause-specific hazard ratios for dementia were estimated to account for the competing risk of death. The proportional hazards assumption was verified by visually inspecting Schoenfeld residual plots. To control for potential confounding factors, we adjusted for age, sex, race-center in the initial model and further adjusted for attained education, APOE 4 carrier status, BMI, alcohol intake, smoking status, total cholesterol level, sitting systolic BP, diabetes, and coronary heart disease status at baseline in the final fully adjusted model. Since the primary exposure, orthostatic BP change, was measured only at visit 1, we considered potential confounding variables collected at the same visit in our primary model to avoid adjustment of potential mediators at subsequent visits. To account for the potential confounding by time-varying covariates such as smoking, alcohol consumption and weight status at subsequent visits, we conducted sensitivity analyses treating these variables as time-varying covariates.

In secondary analyses, we examined potential effect modification by age, sex, race, hypertension status, antihypertension medication use, APOE genotype, length of follow-up, and duration of standing through subgroup analyses stratified by these factors. To evaluate potential underlying mechanisms, we further conducted the analyses stratified by ankle-brachial index (as a measure of arterial stiffness, using the median value of 0.9 as the cut-point) and the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in carotid arteries at visit 1.27,28 Since in typical orthostatic BP responses a transient decrease in BP will be followed by increases in BP resulting from multiple compensatory mechanisms, we also assessed whether the association of initial decreases in BP with the risk of dementia was attenuated after additional adjustment for subsequent compensatory increases in BP and whether this association was further attenuated with additional adjustment for self-reported orthostatic dizziness. In sensitivity analyses, we also adjusted for diastolic BP and antihypertensive medication use instead of sitting systolic BP, additionally adjusted for physical activity and excluded participants with heart failure and atrial fibrillation in separate models. To address potential reverse causation, we also conducted an analysis stratified using mean global cognitive function z-score assessed at visit 2 and an analysis that removed dementia cases occurring within the first five years of follow-up. In addition, , we reran models with adjustment for supine SBP, which is common with OH and hypothesized as a mechanism of injury for dementia. Finally, we repeated analyses, censoring dementia cases after incident coronary heart disease and stroke events to distinguish dementia related to these cardiovascular events from other forms of dementia.

In all the above analyses, all covariates, except SBP level and age, were categorical, and missing data were handled by using an additional category to indicate missing values (<5%). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Participant characteristics

Among 11,644 participants aged 54.5±5.7 years (54.1% women) (Table 1), participants with large decreases in SBP (≤−20 mmHg) from supine to standing position at the first measurement at ~30 seconds upon standing were overall older and appeared to have a lower level of education, higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes, and higher total cholesterol levels compared to participants with smaller initial decreases in SBP.

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics at baseline

| Characteristics | Overall | Orthostatic SBP change (first measurement, mm Hg)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤−20 | >−20 to −10 | >−10 to 10 | >10 to 20 | >20 | ||

|

|

||||||

| (n=11,644) | (n=589) | (n=1,403) | (n=7,006) | (n=1,916) | (n=706) | |

|

|

||||||

| Age, year | 54.5 (5.7) | 57.7 (5.3) | 56.0 (5.6) | 54.1 (5.7) | 53.9 (5.8) | 54.2 (5.5) |

| Female, % | 54.1 | 56.4 | 55.2 | 55.8 | 48.5 | 50.0 |

| Race-study center, % | ||||||

| Washington County, Maryland (White) | 23.1 | 22.1 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 25.0 | 23.5 |

| Jackson, Mississippi (Black) | 23.0 | 22.8 | 18.3 | 20.9 | 29.0 | 36.8 |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota (White) | 27.2 | 22.1 | 23.7 | 28.7 | 26.8 | 23.7 |

| Forsyth, North Carolina (White) | 23.8 | 27.3 | 31.8 | 24.9 | 16.6 | 13.9 |

| Forsyth, North Carolina (Black) | 2.9 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.1 |

| Education level, % | ||||||

| At least some college | 36.9 | 27.8 | 35.6 | 38.0 | 37.2 | 35.8 |

| High school, GED, or vocational school | 41.2 | 38.4 | 42.0 | 41.9 | 40.3 | 37.7 |

| Less than high school | 21.7 | 33.6 | 22.3 | 19.9 | 22.3 | 26.5 |

| APOE genotype, % | ||||||

| 2/2, 2/3, or 3/3 | 68.8 | 68.7 | 68.0 | 69.4 | 68.5 | 65.9 |

| 2/4 or 3/4 | 28.5 | 28.7 | 28.4 | 28.2 | 28.7 | 31.3 |

| 4/4 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Body mass index | 27.1 (4.7) | 26.6 (5.3) | 26.1 (4.9) | 26.6 (4.4) | 28.7 (4.5) | 30.2 (4.7) |

| Body mass index >=30, % | 23.9 | 23.1 | 17.7 | 19.7 | 34.5 | 49.2 |

| Smoking status, % | ||||||

| Never smoker | 41.3 | 31.5 | 42.3 | 40.6 | 44.0 | 47.8 |

| Former smoker | 32.6 | 29.4 | 27.5 | 33.1 | 34.7 | 35.2 |

| Current smoker | 26.0 | 39.1 | 30.2 | 26.3 | 21.3 | 17.0 |

| Hypertension, % | 31.5 | 49.9 | 35.9 | 27.8 | 33.0 | 39.2 |

| Diabetes, % | 10.8 | 18.5 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 12.6 | 14.3 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 213.8 (41.6) | 221.4 (47.2) | 216.4 (41) | 212.1 (41.1) | 213.9 (42.3) | 217.9 (40) |

| Prevalent coronary heart disease at baseline, % | 4.5 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 2.8 |

| Become dizzy upon standing, Yes, % | 9.9 | 15.4 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.6 |

| SBP at supine position | 124 (19) | 142 (22) | 129 (20) | 121 (19) | 125 (17) | 127 (16) |

| SBP at standing position | 124 (20) | 124 (21) | 121 (20) | 122 (19) | 130 (18) | 135 (19) |

| DBP at supine position | 73 (10) | 78 (11) | 73 (10) | 72 (10) | 73 (9) | 74 (9) |

| DBP at standing position | 76 (11) | 75 (12) | 74 (11) | 75 (10) | 78 (10) | 80 (10) |

Data are shown as mean (SD) or percentage.

Standing minus supine SBP.

Orthostatic BP change at individual time points and dizziness

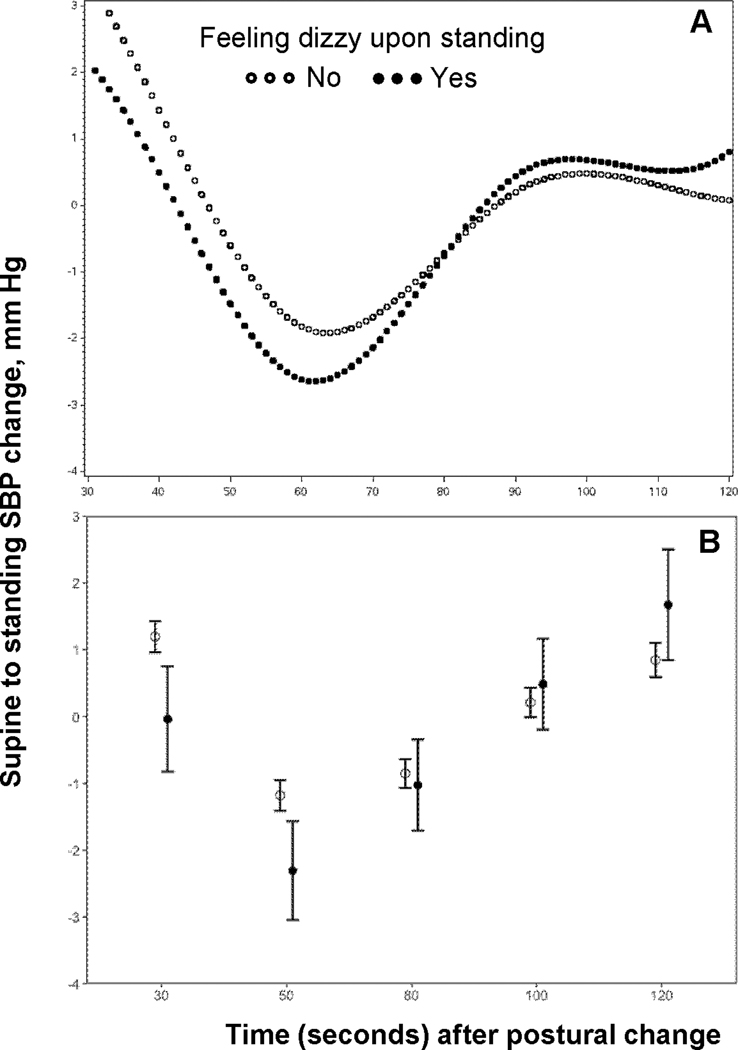

SBP declined steeply at the first two measurements within the first minute of standing (referred to as the initial decrease phase hereafter), followed by a compensatory increase in SBP that plateaued at approximately 90 seconds upon standing (referred to as subsequent increase phase hereafter) (Figure 1A). Compared to those without self-reported dizziness, participants who felt dizzy upon standing had significantly larger decreases in SBP within the first minute.(Figure 1B). The difference in orthostatic changes in SBP became smaller from 1 minute onwards but it diverged again by the end of 2 minutes with participants with orthostatic dizziness appearing to have larger compensatory increases in SBP.

Figure 1.

Orthostatic BP change at individual time points and risk of dementia

A total of 2,303 dementia cases (incidence rate, 8.5 per 1000 person-years) occurred during a median follow-up of 25.9 years (25th percentile-75th percentile, 18.5 to 29.9). Larger decreases in SBP from supine to standing position measured within the first minute upon standing (P values for trend= 0.02 at approximately 30 and 50 seconds both), but not afterward, were linearly associated with a higher risk of dementia (Table 2). Specifically, participants with a decline in SBP at the first measurement of ≤−20 and >−20 to ≤−10 mmHg had 1.22 (95%CI: 1.01–1.47) and 1.10 (95%CI: 0.97–1.25) times higher risk of developing dementia compared to stable SBP (>−10 to 10 mmHg), respectively, after adjustment for potential confounding factors including sitting SBP. The corresponding hazard ratios (HRs) were 1.17 (95%CI: 1.00–1.37) and 0.92 (95%CI: 0.82–1.04) for the second measurement. The spline plots in Figure 2 further show an inverse association of orthostatic SBP change with dementia risk for SBP change within the first minute upon standing, but not thereafter. Consistently, the association of orthostatic hypotension with dementia risk was most pronounced for the first measurement, and it was gradually attenuated over time after standing (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Association of orthostatic systolic blood pressure change with the risk of dementia

| Hazard ratios (95% CI) for dementia by orthostatic SBP change (standing - supine SBP, mmHg) |

P for linearity* | P for non-linearity* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤−20 | >−20 to −10 | >−10 to 10 | >10 to 20 | >20 | per 10 mm Hg | |||

|

|

||||||||

| 1st measurement (~30 seconds upon standing, n=11,620) | ||||||||

| No. of events/ participants | 126/589 | 299/1403 | 1342/7006 | 377/1916 | 157/706 | - | - | |

| Hazard ratio (Model 1) | 1.34 (1.11, 1.61) | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 1 (Ref)# | 1.04 (0.93, 1.17) | 1.04 (0.88, 1.23) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.00) | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| Hazard ratio (Model 2) | 1.22 (1.01, 1.47) | 1.10 (0.97, 1.25) | 1 (Ref) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.11) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.11) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.02 | 0.82 |

| 2nd measurement (~50 seconds upon standing, n=11,634) | ||||||||

| No. of events/ participants | 184/844 | 342/1696 | 1412/7171 | 273/1508 | 91/415 | |||

| Hazard ratio (Model 1) | 1.26 (1.08, 1.47) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.11) | 1 (Ref) | 0.88 (0.77, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24) | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Hazard ratio (Model 2) | 1.17 (1.00, 1.37) | 0.92 (0.82, 1.04) | 1 (Ref) | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) | 1.03 (0.83, 1.28) | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| 3rd measurement (~75 seconds upon standing, n=11,635) | ||||||||

| No. of events/ participants | 133/647 | 327/1609 | 1458/7573 | 308/1465 | 77/341 | |||

| Hazard ratio (Model 1) | 1.23 (1.03, 1.48) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.11) | 1 (Ref) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.12) | 1.13 (0.90, 1.42) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.22 | 0.53 |

| Hazard ratio (Model 2) | 1.10 (0.92, 1.32) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) | 1 (Ref) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.08) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.36) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| 4th measurement (~100 seconds upon standing, n=11,633) | ||||||||

| No. of events/ participants | 121/558 | 285/1397 | 1446/7593 | 352/1627 | 98/458 | |||

| Hazard ratio (Model 1) | 1.25 (1.03, 1.50) | 1.08 (0.95, 1.22) | 1 (Ref) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.23) | 1.09 (0.89, 1.34) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.40 | 0.09 |

| Hazard ratio (Model 2) | 1.15 (0.95, 1.39) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) | 1 (Ref) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.22) | 1.06 (0.86, 1.30) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.61 | 0.06 |

| 5th measurement (~115 seconds upon standing, n=7,502) | ||||||||

| No. of events/ participants | 50/244 | 176/813 | 941/5079 | 230/1089 | 59/277 | |||

| Hazard ratio (Model 1) | 1.07 (0.80, 1.42) | 1.11 (0.95, 1.31) | 1 (Ref) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.30) | 1.07 (0.82, 1.39) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.84 | 0.35 |

| Hazard ratio (Model 2) | 0.94 (0.70, 1.25) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.28) | 1 (Ref) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) | 1.02 (0.78, 1.32) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.80 | 0.54 |

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex and race-center.

Model 2 was additionally adjusted for attained education, APOE 4 carrier status, body mass index, alcohol intake, smoking status, total cholesterol level, average sitting systolic blood pressure, and history of diabetes and coronary heart disease at baseline.

P values were from models with penalized splines for orthostatic SBP change to detect the deviation from linearity.

Reference level

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Results from other secondary and sensitivity analyses

Orthostatic changes in DBP similarly had the most pronounced inverse association with dementia risk at the first measurement (Supplemental Table S3). The inverse association of orthostatic SBP change at approximately 30 seconds after standing with dementia did not differ significantly across subgroups stratified by age, sex, race, hypertension status and other variables (Supplemental Figure S2). This association remained similar in the following sensitivity analyses: 1) adjusting for smoking, alcohol consumption, and weight status at subsequent visits as time-varying covariates, 2) replacing sitting SBP with DBP or antihypertensive medication use, 3) excluding participants with heart failure or atrial fibrillation at baseline, and 4) additionally adjusting for classes of antihypertensive medication and physical activity (Supplemental Table S4). The association showed no significant difference when stratified by global cognitive score at visit 2 and remained statistically significant after excluding dementia cases identified within the first 5 years of follow-up in separate models. The association weakened after additional adjustment for supine SBP and censoring dementia cases diagnosed after incident coronary heart disease during the follow-up. (Supplemental Table S5).

Orthostatic BP change patterns, dizziness, and risk of dementia

Elevated dementia risk associated with initial large decreases in SBP was sustained after adjustment for self-reported dizziness (Supplement Table S4). Individuals feeling dizzy upon standing appeared to have a slightly higher risk of dementia, but the association was not statistically significant (Supplement Tables S6). Similar magnitudes of higher dementia risk were observed with early OH (during the first minute) and sustained OH (during both the first and second minutes) but not with late OH (only during the second minute) (Supplement Table S7). When initial orthostatic SBP change, subsequent SBP change, and conventional sitting SBP level were analyzed jointly in the same model, larger initial decreases in BP, exaggerated increases in BP, and higher sitting BP were all associated with a higher risk of dementia after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Supplement Figure S3).

Discussion

In this community-based prospective cohort study of middle-aged adults, we found that large SBP decreases within the first minute of postural change were associated with dizziness and a higher risk of incident dementia over a follow-up of up to three decades. In contrast, orthostatic SBP decreases after 1 minute were not associated with dementia. These findings demonstrate that initial orthostatic BP decreases within the first minute after standing may be most relevant for the development of dementia.

Prior studies, including a previous report from the ARIC study, have described a link between orthostatic hypotension and a higher risk of dementia.3–8 Our study adds to this literature, showing that large decreases in BP within the first minute of standing are most strongly associated with greater dementia risk. This finding is consistent with reports of other adverse outcomes associated with orthostasis, including another report from the ARIC study showing that measurements of orthostatic BP change within ~60 seconds of standing were associated with dizziness and a higher risk of fracture, fall, syncope and mortality.16 Yet another report demonstrated that orthostatic symptoms immediately after standing, but not delayed orthostatic drops in BP after standing, were associated with incident dementia among older adults.29 Several prospective cohort studies,3–8 but not all,29,30 have reported that orthostatic hypotension was associated with cognitive decline and a higher risk of dementia. The discrepancy observed in previous studies could be due to the use of different orthsotatic BP assessment protocols, such as measuring in BP from sitting to standing rather than from supine to standing.31 In light of our findings, the discrepancy may also be attributable to the varied timing of orthostatic BP assessment since most studies focused on the assessment after one minute upon standing.

We also observed an interesting but not statistically significant association between large increases in BP approximately 2 minutes after standing and greater risk of dementia. This is consistent with emerging data suggesting that hyperreactivity to orthostatic stress is associated with adverse health outcomes13,32 and a prior report from the ARIC study showing that both orthostatic increases and decreases in SBP were associated with incident lacunar stroke.33 The clinical relevance of orthostatic hypertension warrants further investigation. Interestingly, when initial (i.e., within 1 minute of standing) and subsequent (i.e., after 1 minute) orthostatic SBP changes were analyzed jointly in the same model, both large initial decreases and exaggerated subsequent increases in SBP were associated with a higher risk of dementia, even after adjusting for SBP, which itself was also positively associated with dementia risk. These results suggest that dynamic measures of BP phenotypes, such as orthostatic BP changes, may capture additional hypertension-mediated organ damage above and beyond conventional sitting BP.

The mechanisms whereby orthostatic BP changes relate to dementia risk remain largely unknown. It is possible that abnormal orthostatic BP responses at different time points operate through distinct pathways. Abnormal orthostatic BP response could either be a risk factor of dementia or an early symptom of the neurodegenerative process preceding the diagnosis of dementia, given the insidious onset and long prodromal stage of dementia.34 Orthostatic hypotension is a classical manifestation of autonomic dysfunction associated with the neurodegenerative process and it is frequently observed even before the clinical diagnosis of dementia or other neurodegenerative disorders such as Lewy Body disease or Parkinson’s disease that may have an early onset in middle-aged adults.35 Although our sensitivity analyses restricting participants to better cognitive function at visit 2 and excluding dementia cases onsetting within the first 5 years of follow-up showed similar findings, we still cannot rule out the possibility that orthostatic hypotension may result from dementia-related autonomic dysfunction before cognitive abnormalities manifest (i.e., reverse causation). The observed association was moderately attenuated after additionally adjusting for supine SBP, also suggesting supine hypertension as a mechanism for injury.36 Alternatively, abrupt sudden decreases in BP during the first minute could induce cerebral hypoperfusion and hypoxia, contributing to ischemic brain lesions and subsequent dementia.32,37,38 The brain’s delicate autoregulation process to maintain stable cerebral perfusion over a range of BPs appears to be impaired with aging and prolonged hypertension, making it more vulnerable to hypotension-related brain ischemia.39 Cerebral autoregulation may be preserved but delayed with aging40, such that orthostatic hypotension occurring later than 1 minute can be counter-regulated to maintain cerebral perfusion despite a fall in BP, but several other studies do not support the impairment of cerebral autoregulation.41 Future investigations including cerebral hemodynamic measures will improve our understanding of this relationship.

Our findings have several important implications. First, our observation of the relationship between the initial large drops (rather than subsequent or prolonged orthostatic hypotension) and greater dementia risk emphasizes the clinical relevance of orthostatic BP assessment within one minute of postural change. In clinical settings, delaying assessment of orthostatic BP change beyond 1 minute of standing might miss a critical time window for dementia risk. Our findings may foster further research on early abrupt changes after standing to improve our understanding of their underlying mechanisms and clinical relevance. Moreover, our study suggests that abnormal orthostatic BP responses may manifest in various forms, including hyperactivity to standing and the joint association of initial large drops in SBP and exaggerated subsequent increases in SBP with dementia risk also suggests that orthostatic BP assessment at different time points could be complementary and that the timing of orthostatic BP assessment may be clinically relevant. The attenuated association, after censoring dementia cases following incident coronary heart disease or stroke, further emphasizes the importance of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease to prevent dementia.

Several limitations should be noted. First, for orthostatic BP assessments, we do not have available data on the concurrent compensational heart rate, limiting our ability to inform the causes of OH. Second, orthostatic BP assessments were completed within approximately 2 minutes after standing, and we were not able to assess the role of delayed orthostatic hypotension after 3 minutes of standing, a time of interest in several guidelines.35,42,43 Also, we do not have data on the concurrent changes in cerebral blood flow or cerebrovascular reactivity, which could inform whether large drops in BP correlate with cerebral hypoperfusion and identify participants who are most vulnerable to large drops in BP. Third, the measurement protocol was designed to terminate with symptoms of discomfort or dizziness, and therefore people excluded from the analyses due to incomplete BP measurements are more likely to have higher prevalence of orthostatic dizziness and likely larger early BP drops. Additionally, we also do not have detailed information on the causes and subtypes of dementia such as vascular dementia, Lewy Body Dementia or Parkinson’s Dementia and we are not able to assess if associations were due to subclinical vascular pathology or neurodegeneration. Due to the observational nature of our study, residual confounding is possible and we are limited in investigating the causal relationship and class effects of antihypertensive medication, such as β-blockers, in this association.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Relevance.

What is new?

In community-based middle-aged adults, abrupt drops in blood pressure within the first minute of standing, but not afterward, were associated with self-reported dizziness and an elevated long-term risk of dementia.

What is relevant?

Our findings suggest that initial orthostatic blood pressure decreases within the first minute after standing may be most relevant for the development of dementia.

Clinical/Pathophysiological Implications?

Transient early orthostatic hypotension warrants more attention in clinical settings and the timing of orthostatic blood pressure assessments should be considered when interpreting such assessments.

Perspectives.

Large decreases in orthostatic BP within one minute of standing were associated with a higher risk of dementia. Transient early orthostatic hypotension warrants more attention in clinical settings and the timing of orthostatic BP assessments should be considered when interpreting orthostatic BP assessments.

Acknowledgments

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract nos. (75N92022D00001, 75N92022D00002, 75N92022D00003, 75N92022D00004, 75N92022D00005). The ARIC Neurocognitive Study is supported by U01HL096812, U01HL096814, U01HL096899, U01HL096902, and U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA and NIDCD). The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

This work was also supported by grants (K99AG071742 and R00AG071742, to Dr. Ma) from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. This research was funded, in part, by the NIA Intramural Research Program (KAW) and the NINDS Intramural Research Program (RFG). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- BP

blood pressure

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- OH

orthostatic hypotension

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Freeman R, Abuzinadah AR, Gibbons C, Jones P, Miglis MG, Sinn DI. Orthostatic Hypotension: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(11):1294–1309. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juraschek SP, Taylor AA, Wright JT, et al. Orthostatic Hypotension, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Adverse Events. Hypertension 2020. DOI: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.14309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolters FJ, Mattace-Raso FU, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Ikram MA, Heart Brain Connection Collaborative Research Group. Orthostatic Hypotension and the Long-Term Risk of Dementia: A Population-Based Study. PLoS Med 2016;13(10):e1002143. (In eng). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cremer A, Soumare A, Berr C, et al. Orthostatic Hypotension and Risk of Incident Dementia: Results From a 12-Year Follow-Up of the Three-City Study Cohort. Hypertension 2017;70(1):44–49. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elmstahl S, Widerstrom E. Orthostatic intolerance predicts mild cognitive impairment: incidence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia from the Swedish general population cohort Good Aging in Skane. Clin Interv Aging 2014;9:1993–2002. (In eng). DOI: 10.2147/cia.s72316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayakawa T, McGarrigle CA, Coen RF, et al. Orthostatic Blood Pressure Behavior in People with Mild Cognitive Impairment Predicts Conversion to Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(9):1868–73. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/jgs.13596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose KM, Couper D, Eigenbrodt ML, Mosley TH, Sharrett AR, Gottesman RF. Orthostatic hypotension and cognitive function: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Neuroepidemiology 2010;34(1):1–7. DOI: 10.1159/000255459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawlings AM, Juraschek SP, Heiss G, et al. Association of orthostatic hypotension with incident dementia, stroke, and cognitive decline. Neurology 2018;91(8):e759–e768. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibao C, Lipsitz LA, Biaggioni I. Evaluation and treatment of orthostatic hypotension. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension 2013;7(4):317–324. DOI: 10.1016/j.jash.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak V, Novak P, Spies JM, Low PA. Autoregulation of Cerebral Blood Flow in Orthostatic Hypotension. Stroke 1998;29(1):104–111. DOI: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strandgaard S, Olesen J, Skinhøj E, Lassen NA. Autoregulation of Brain Circulation in Severe Arterial Hypertension. Br Med J 1973;1(5852):507–510. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.1.5852.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naritomi H. Effects of Advancing Age on Regional Cerebral Blood Flow. Arch Neurol 1979;36(7):410. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.1979.00500430040005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan J, Ricci F, Hoffmann F, Hamrefors V, Fedorowski A. Orthostatic Hypertension: Critical Appraisal of an Overlooked Condition. Hypertension 2020;75(5):1151–1158. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright JD, Folsom AR, Coresh J, et al. The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) Study: JACC Focus Seminar 3/8. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77(23):2939–2959. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nardo CJ, Chambless LE, Light KC, et al. Descriptive Epidemiology of Blood Pressure Response to Change in Body Position. Hypertension 1999;33(5):1123–1129. DOI: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juraschek SP, Daya N, Rawlings AM, et al. Association of History of Dizziness and Long-term Adverse Outcomes With Early vs Later Orthostatic Hypotension Assessment Times in Middle-aged Adults. JAMA Internal Medicine 2017;177(9):1316. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia prevalence: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2016;2(1):1–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Prevalence: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS). Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;2:1–11. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9 Suppl 1:173–6; discussion 177–8. (In eng). DOI: 10.1017/s1041610297004870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr., Chance JM, Filos S.Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 1982;37(3):323–9. (In eng). DOI: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Berg E, Ruis C, Biessels GJ, Kappelle LJ, van Zandvoort MJ. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (Modified): relation with a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2012;34(6):598–605. (In eng). DOI: 10.1080/13803395.2012.667066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Xiong C, Morris JC. Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology 2006;67(11):1942–8. (In eng). DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247042.15547.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker KA, Sharrett AR, Wu A, et al. Association of Midlife to Late-Life Blood Pressure Patterns With Incident Dementia. JAMA 2019;322(6):535. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siedel J, Hägele EO, Ziegenhorn J, Wahlefeld AW. Reagent for the enzymatic determination of serum total cholesterol with improved lipolytic efficiency. Clin Chem 1983;29(6):1075–80. (In eng). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR, et al. Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, 1987–1993. Am J Epidemiol 1997;146(6):483–94. (In eng). DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clinical Autonomic Research 2011;21(2):69–72. DOI: 10.1007/s10286-011-0119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weatherley BD, Nelson JJ, Heiss G, et al. The association of the ankle-brachial index with incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study, 1987–2001. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2007;7:3. (In eng). DOI: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li R, Duncan BB, Metcalf PA, et al. B-mode-detected carotid artery plaque in a general population. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Stroke 1994;25(12):2377–2383. DOI: doi: 10.1161/01.STR.25.12.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juraschek SP, Longstreth WT, Lopez OL, et al. Orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, neurology outcomes, and death in older adults. Neurology 2020;95(14):e1941-e1950. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000010456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Lamar M, et al. Late-life blood pressure association with cerebrovascular and Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology 2018;91(6):e517–e525. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah RC, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Arvanitakis Z, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Relation of blood pressure to risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and change in global cognitive function in older persons. Neuroepidemiology 2006;26(1):30–6. (In eng). DOI: 10.1159/000089235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palatini P, Mos L, Saladini F, Rattazzi M. Blood Pressure Hyperreactivity to Standing: a Predictor of Adverse Outcome in Young Hypertensive Patients. Hypertension 2022;79(5):984–992. DOI: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.121.18579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yatsuya H, Folsom AR, Alonso A, Gottesman RF, Rose KM. Postural Changes in Blood Pressure and Incidence of Ischemic Stroke Subtypes. Hypertension 2011;57(2):167–173. DOI: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.161844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2011;7(3):280–292. DOI: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman R. Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension. New Engl J Med 2008;358(6):615–624. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp074189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein DS, Pechnik S, Holmes C, Eldadah B, Sharabi Y. Association between supine hypertension and orthostatic hypotension in autonomic failure. Hypertension 2003;42(2):136–42. DOI: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000081216.11623.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manley G, Knudson MM, Morabito D, Damron S, Erickson V, Pitts L. Hypotension, Hypoxia, and Head Injury: Frequency, Duration, and Consequences. Archives of Surgery 2001;136(10):1118–1123. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.136.10.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yatsu F, Lindquist P, GRAZIANO C. An Experimental Model of Brain Ischemia Combining Hypotension and Hypoxia. Stroke 1974;5(1):32–39. DOI: doi: 10.1161/01.STR.5.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toth P, Tarantini S, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Functional vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: mechanisms and consequences of cerebral autoregulatory dysfunction, endothelial impairment, and neurovascular uncoupling in aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2017;312(1):H1–h20. (In eng). DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00581.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heckmann JG, Brown CM, Cheregi M, Hilz MJ, Neundörfer B. Delayed cerebrovascular autoregulatory response to ergometer exercise in normotensive elderly humans. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003;16(4):423–9. (In eng). DOI: 10.1159/000072567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heutz R, Claassen J, Feiner S, et al. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2023:0271678X2311734. DOI: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Delayed orthostatic hypotension. A frequent cause of orthostatic intolerance 2006;67(1):28–32. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223828.28215.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen W-K, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70(5):e39–e110. DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.