Abstract

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and rhodesiense, is a parasitic disease endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Untreated cases of HAT can be severely debilitating and fatal. Although the number of reported cases has decreased progressively over the last decade, the number of effective and easily administered medications is very limited. In this work, we report the antitrypanosomal activity of a series of potent compounds. A subset of molecules in the series are highly selective for trypanosomes and are metabolically stable. One of the compounds, (E)-N-(4-(methylamino)-4-oxobut-2-en-1-yl)-5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxamide (10), selectively inhibited the growth of T. b. brucei, T. b. gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense, have excellent oral bioavailability and was effective in treating acute infection of HAT in mouse models. Based on its excellent bioavailability, compound 10 and its analogs are candidates for lead optimization and pre-clinical investigations.

Keywords: Trypanosomes, inhibitors, Cysteine protease, HAT, Vinyl sulfone

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Two sub-species of Trypanosoma brucei, T. b. gambiense, predominantly found in Central and West Africa, and T. b. rhodesiense, which is endemic to Eastern and Southern Africa, cause human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also called sleeping sickness [1]. Most reported cases of HAT in the past two decades are caused by T. b. gambiense [2]. While tremendous progress has been made in reducing the public health challenge posed by HAT, the lack of access to adequate diagnostic tools and effective medicines has hampered its elimination in sub-Saharan Africa over the past half-century.

HAT remains targeted for elimination as a public health problem in the World Health Organization’s Neglected Tropical Disease Roadmap by the end of this decade [3]. However, continued transmission of parasites to humans from zoonotic reservoirs cannot be ruled out in the coming years. In addition, limited access to adequate primary healthcare services, especially in rural communities, makes it imperative to develop easily administered and effective curative agents for HAT. Fexinidazole, the first orally active medicine for gambiense-HAT, was approved about four years ago in a significant advancement for the treatment of HAT cases.

Fexinidazole is known to induce nausea, and its absorption depends on food ingestion. In addition, point-of-care observation by trained health staff is required for potential signs of adverse effects and relapse [4-6]. The benzoxaborole derivative, acoziborole, is also being developed as a potential single-dose oral drug for HAT. Recent reports from a phase 2/3 trial show that acozoborole is efficacious and safe in gambiense-HAT patients and has a good chance of being approved for clinical use in endemic countries [7].

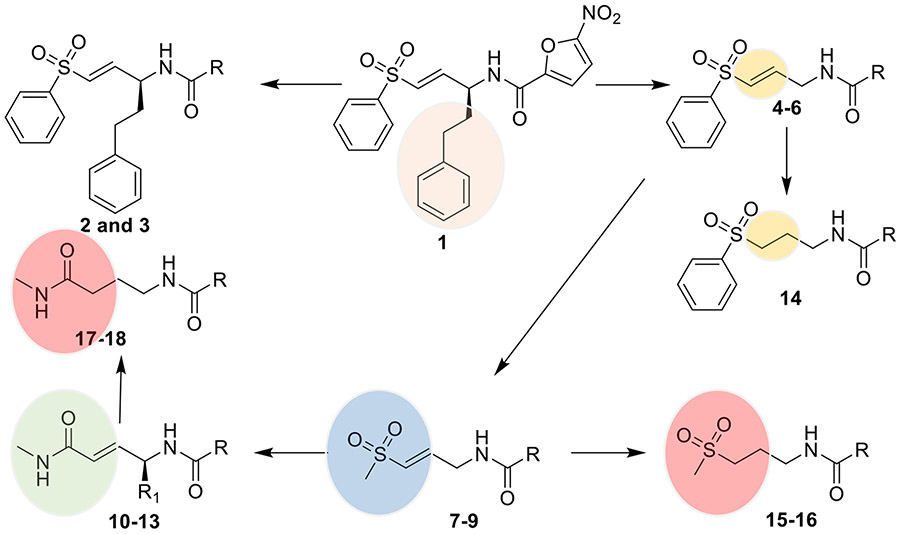

Our previous work on antitrypanosomal agents led to the discovery of trypanosomal cathepsin-L (TCatL) covalent inhibitors that displayed submicromolar activity against T. brucei [8]. Despite the potency, compound 1 lacks oral bioavailability and in vivo efficacy in mouse models of HAT. As a continuation of that work, a structure-activity relationship study was initiated to identify analog(s) that are potent, selective, metabolically stable, and have oral bioavailability. As shown in Figure 1 below, the structure-activity relationship includes replacing the phenethyl side chain that occupies the P1 site in TCatL’s active site in compound 1 with H, ii) replacing the covalent warheads, and iii) the nitroaromatic heterocycles. The changes were guided by potencies on the parasites, stability of the molecules to liver enzymes in vitro, inhibition of tCatL, and cytotoxicity. Overall, we found that a combination of the 4-(methylamino)-4-oxobut-2-en-1-yl motif and nitrothiophene or nitrofuran motif are potent against the three T. brucei subspecies (brucei, gambiense, and rhodesiense) and can serve as lead compounds against HAT.

Figure 1.

Structure of previously reported covalent inhibitor of tCatL (1) [8]. Multiparameter structure-activity investigation identified 10 as an orally active antitrypanosomal agent. Please see the R groups in Table 1 or the experimental section.

Experimental Section

General Procedures:

The 1H and 13C NMR data were obtained on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million, relative to residual solvent peak for 1H and 13C. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates were used to monitor reactions, and the spots were visualized by irradiation with ultraviolet light (254 nm) or by staining with potassium permanganate. NMR and HPLC profiles were used to determine compound purity. Compounds were purified by silica gel (Sorbtech, Norcross, GA, USA, 60Å, 200-500 μm (35 x 70 mesh)) column chromatography, pre-coated preparative TLC plates (SiliCycle Inc, Quebec City, Canada, 1,000 μm, 20 x 20 cm), or Biotage flash column chromatography (Silica D Duo 20 and 60 μm cartridges). HPLC was carried out using a Pinnacle II C18, 5 μM, 200 x 4.6 mm column with isocratic elution with 70% acetonitrile and water (0.1% TFA) and flowrate of 0.5 mL/min). High-resolution mass spectrometric (HRMS) data was obtained on a Synapt G2 HDMS instrument operated in positive or negative ESI mode. Spectra are provided as supplementary information (Figure S1).

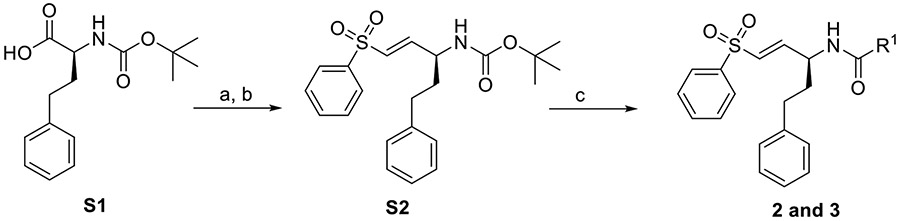

Synthesis of 2-3.

Compounds 2-3 were synthesized as previously described [8] and summarized in Scheme 1 below.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2 and 3. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH2Cl2, CDI, 0°C, 1 hr. Then DIBAL-H, −78°C; 80% (b) NaH, THF, diethyl((phenylsulfonyl)methyl) phosphonate, 0°C, 25 min, 60%; (c) S2 (0.24 mmol), 33% TFA in DCM (2 mL), 0°C, 1.5 h. Then ACN (2 mL), R-COOH (0.18 mmol), Et3N (0.36 mmol), HBTU (0.36 mmol), Room Temperature, 16 h, 30-40%.

(S,E)-2-(2-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-[5-phenyl-1-(phenylsulfonyl)pent-1-en-3-yl]acetamide (2).

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 1 above. 2-(2-methyl-5-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)acetic acid (33.3 mg) was used as acid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.67 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (s, 1H), 7.82 (dt, 2H), 7.71 (m, 1H), 7.62 (m, 2H), 7.20 (m, 5H), 6.89 (dd, J = 15.1, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (dd, J = 15.1, 1.6 Hz 1H), 5.03 (dd, 2H), 4.48 (dd, 1H), 2.63 (m, 1H), 2.54 (m, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 1.94 (m, 1H), 1.74 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.2, 152.4, 147.2, 141.5 140.7, 138.9, 132.9, 130.4, 130.1,128.8, 127.5, 49.5, 48.7, 35.1, 31.8, 14.3, 14.2. HRMS [M-H]− calculated for C23H23N4O5S: 467.1389; found: 467.1391. HPLC: Retention time (RT) = 5.41min.

(S,E)-4-chloro-5-nitro-N-[5-phenyl-1-(phenylsulfonyl)pent-1-en-3-yl]-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxamide (3).

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 1 above. 4-chloro-5-nitro-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (34.3 mg) was used as acid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.90 (dd, 2H), 7.73 (tt, 1H), 7.61 (tt, 2H), 7.31 (t, 2H), 7.23 (t, 1H), 7.16 (d, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.39 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.52 (d, 1H), 4.38 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (dd, J = 13.9, 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (dd, J = 13.9, 2.9 HZ,1H), 2.78 (m, 2H), 1.93 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 156.5, 139.5, 138.5, 134.8, 129.8, 128.9, 128.2, 127.9, 126.8, 124.9, 118.4.0, 114.6, 77.2, 56.7, 53.3, 53.0, 36.1, 31.7. HRMS [M-H]− calculated for C22H19ClN3O5S: 472.0734; found: 472.0732. HPLC: RT = 6.61 min.

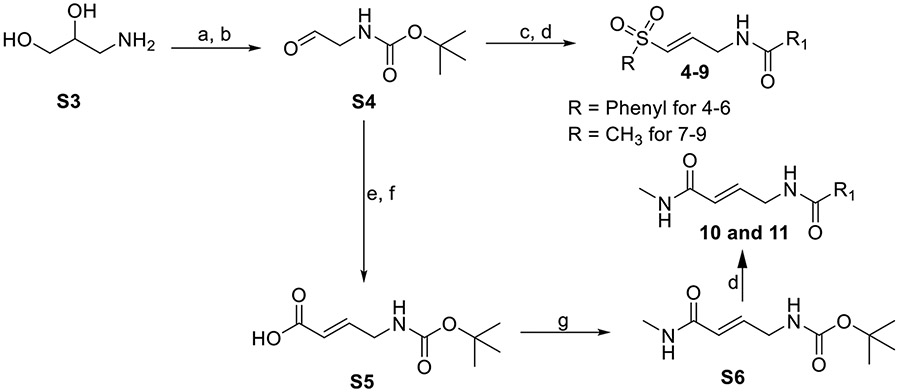

Synthesis of 4-11

Compounds 4-9 were synthesized from S6 as previously described [8] and summarized in Scheme 2 below.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 4-11. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH2Cl2:CH3OH, Et3N, Boc2O, 23°C, 2 h; (b) H2O, NaIO4, RT, 1 h, >90%; (c) NaH, THF, diethyl((methylsulfonyl)methyl) phosphonate or diethyl((phenylsulfonyl)methyl) phosphonate, 0°C, 25 min, 40-70%; (d) tert-butyl (E)-(3-(phenylsulfonyl)allyl)carbamate (0.17 mmol), tert-butyl (E)-(3-(methylsulfonyl)allyl)carbamate (0.21 mmol), or S6 (0. 23 mmol), 33% TFA in DCM, 0°C, 1.5 h. Then ACN (2 mL), R-COOH (1.5 mol eq), Et3N (2 mol eq), HBTU (2 mol eq), RT, 16 h, 35-45%; (e) methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene)acetate, THF, RT, 2 hr; (f) LiOH, THF/H2O, RT, 16 h; (g) N-methylmorpholine (NMM), isobutyl chloroformate, 0°C, 1 hr. Then, methylamine, room temperature, 15 h.

Compounds 10 and 11 were synthesized from S6, as summarized in Scheme 2 above. To obtain S6, methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene)acetate (10.5 g, 33.0 mmol) was added to a solution of S4 (5.0 g, 31.4 mmol) in dry THF (200 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored with TLC (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 3:1) for 2 hours. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the intermediate product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 5:1) to obtain a white solid (4.5 g, 67.1 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.92 (dt, J = 15.7, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.94 (dt, J = 15.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.69 (s, 1H), 3.92 (s, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 9H). The intermediate product (4.5 g, 20.9 mmol) was dissolved in THF (50 mL)/H2O (5 mL), followed by the addition of LiOH (1.93 g, 41.8 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored by TLC (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 3:1). The hydrolysis was complete after 16 hours. The mixture was concentrated at reduced pressure, the pH of the concentrate was adjusted to 4 with 1N HCl and then extracted twice, with 40 mL of ethyl acetate. The extract was washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain S5 (3.5 g, 83.3 %) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.01 (dt, J = 15.6, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (dt, J = 15.6, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (s, 1H), 3.96 (s, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

To a solution of S5 (2.5 g, 12.5 mmol) in dry THF (80 mL), N-methylmorpholine (4.0 g, 37.5 mmol), and isobutyl chloroformate (1.90 g, 15.0 mmol) were added at 0°C. The mixture was stirred in an ice bath for 1 hour. Subsequently, methylamine (9.4 mL, 18.75 mmol, 2.0 M in THF) was added and stirred at room temperature for 15 hours. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (30 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (80 mL). The organic layers were combined and washed with brine (50 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (PE/EA=2:1) to obtain S6 (1.5 g, 56.2 %) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.76 (dt, J = 15.0, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.90 (dt, J = 15.6, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (s, 1H), 4.73 (s, 1H), 3.88 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 2.88 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 3H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

(E)-5-nitro-N-[3-(phenylsulfonyl)allyl]thiophene-2-carboxamide (4)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.25 mmol, 44.1 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ, 9.30 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H) 8.15 (d, J = 4.4, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (m, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 4.4, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (tt, 1H), 7.65 (tt, 2H), 6.93 (m, 2H), 4.16 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.7, 153.0, 145.6, 143.3, 140.2, 133.8, 130.4, 130.2, 129.6, 127.9, 127.3. 39.6. HRMS [M+Na]+ calculated for C14H12N2O5S2Na: 375.0085; found: 375.0059. HPLC: RT = 8.80 min.

(E)-5-nitro-N-[3-(phenylsulfonyl)allyl]furan-2-carboxamide (5)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (0.25 mmol, 39.3 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.19 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, 2H), 7.75 – 7.76 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (m,1H), 7.64 (m, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (m, 2H), 4.13 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 156.7, 148.4, 143.8, 140.7, 134.2, 130.8, 130.1, 129.8, 127.7, 116.4, 113.9, 40.5. HRMS [M+Na]+ calculated for C14H12N2O6SNa: 359.0314; found: 359.0309. HPLC: RT = 4.63 min.

(E)-N-[3-(phenylsulfonyl)allyl]furan-2-carboxamide (6)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (0.25 mmol, 28.0 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, 2H), 7.71 (t, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 1.8, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (t, 2H), 7.06 (td, 1H), 7.02 (dt, J = 15.1, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (dt, J = 15.1, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (dd, J = 3.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (td, J = 6.3, 4.6, 1.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 157.8, 148.2, 144.6, 1436, 141.1, 133.4, 130.8, 129.4, 127.5, 113.7, 111.8, 38.8 HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C14H13NO4SNa: 314. 0463; found: 314.0460. HPLC: RT = 4.5 min.

(E)-N-[3-(methylsulfonyl)allyl]-5-nitrofuran-2-carboxamide (7)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (0.32 mmol, 49.5 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.25 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (dd, 2H), 3.00 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 156.7, 151.9, 148.4, 142.7, 131.0, 116.4, 113.9, 42.6, 39.4. HRMS [M-H]− calculated for C9H9N2O6S: 273.0181; found: 273.0177. HPLC: RT = 4.25.

(E)-N-[3-(methylsulfonyl)allyl]-5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxamide (8)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.32 mmol, 54.6 mg) was used as acid. Its synthesis was scaled up to 1 gram for the in vivo experiments. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (dt, J = 15.3, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (dt, J = 15.3, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (tt, J = 4.4, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 206.2, 160.8, 146.5, 143.3, 131.9, 130.0, 127.9, 42.7, 40.5. HRMS [M-H]- calculated for C9H10N2O5S2:289.9978; found: 289.9976. HPLC: RT = 5.50 min.

(E)-N-[3-(methylsulfonyl)allyl]thiophene-2-carboxamide (9)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.32 mmol, 40.5 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.17 (s, 1H), 7.77 (dd, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (dd, J = 5.0, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (dt, J = 15.3, Hz, 1H), 6.73 (dt, J = 15.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (ddt, J = 6.1, 4.5, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 162.3, 144.2, 131.5, 131.4, 128.9, 128.6, 42.7, 40.2, 38.7. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C9H11NO3S2Na: 268.0078; found: 268.0084. HPLC: RT = 4.22 min.

(E)-N-[4-(methylamino)-4-oxobut-2-en-1-yl]-5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxamide (10)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.34 mmol, 59.7 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 6.73 (dt, J = 15.3, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 6.08 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 3H), 2.74 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, acetone) δ 166.0, 160.5, 154.6, 146.9, 138.5, 130.0, 127.5, 125.7, 41.1, 26.0. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C10H11N3O4SNa: 292.0369 ; found 292.0377. HPLC: RT = 4.23 min.

(E)-N-[4-(methylamino)-4-oxobut-2-en-1-yl]-5-nitrofuran-2-carboxamide (11)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 2 above. 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (0.34 mmol, 53.4 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.22 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (q, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (dt, J = 15.5, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (dt, J = 15.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (td, J = 5.5, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 2.62 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ 164.94, 156.06, 151.52, 148.09, 137.79, 124.35, 115.76, 113.53, 39.57, 25.53. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C10H11N3O5Na: 276.0596 ; found 276.0604. HPLC: RT = 4.16 min.

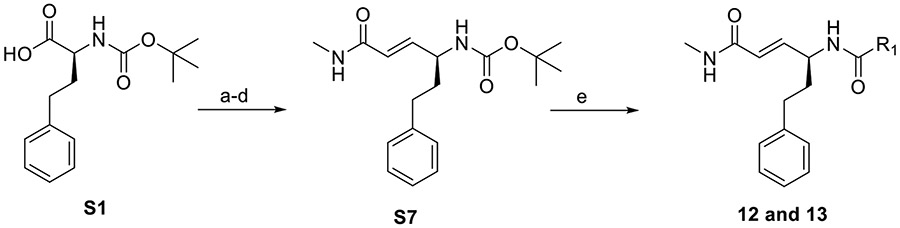

Synthesis of 12 and 13

Compounds 12 and 13 were synthesized from S7. S7 was made as described for S6 above and summarized in Scheme 3 below.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 12 and 13. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH2Cl2, CDI, 0°C, 1 hr. Then DIBAL-H, −78°C; 80%; (b) methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene)acetate, THF, RT, 2 hr; (c) Li-OH, THF/H2O, RT, 16 hr; (d) N-methylmorpholine (NMM), isobutyl chloroformate, 0°C, 1 hr. Then, methylamine, RT, 15 hr; (e) S7 (0.16 mmol), 33% TFA in DCM, 0°C, 1.5 hr. Then ACN (2 mL), R-COOH (1.5 mol eq), Et3N (2 mol eq), HBTU (2 mol eq), RT, 16 hr.

(E)-N-[6-(methylamino)-6-oxo-1-phenylhex-4-en-3-yl]-5-nitrofuran-2-carboxamide (12)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (0.24 mmol, 37.7 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.56 (dd, J = 8.6, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.28 – 7.13 (m, 5H), 6.80 (dd, J = 15.4, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.13 (dt, J = 15.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.80 – 4.72 (m, 1H), 2.83 – 2.65 (m, 5H), 2.12 – 1.97 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone) δ 166.58, 156.83, 152.51, 149.27, 142.46, 142.21, 129.20, 126.68, 125.16, 116.58, 113.58, 51.05, 36.30, 32.94, 26.17. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C18H19N3O5Na: 380.1223 ; found 380.1223. HPLC: RT = 4.87 min.

(E)-N-[6-(methylamino)-6-oxo-1-phenylhex-4-en-3-yl]-5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxamide (13)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.24 mmol, 41.6 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.98 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.28 – 7.12 (m, 5H), 6.73 (dd, J = 15.4, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (dd, J = 15.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (dd, J = 13.9, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (s, 3H), 2.72 (td, J = 7.4, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 2.03 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD3OD) δ 168.54, 161.84, 155.50, 146.32, 143.33, 142.32, 129.84, 129.51, 128.29, 127.10, 124.92, 52.13, 36.62, 33.44, 26.33. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C18H19N3O4SNa: 396.0994 ; found 396.1000. HPLC: RT = 5.07 min.

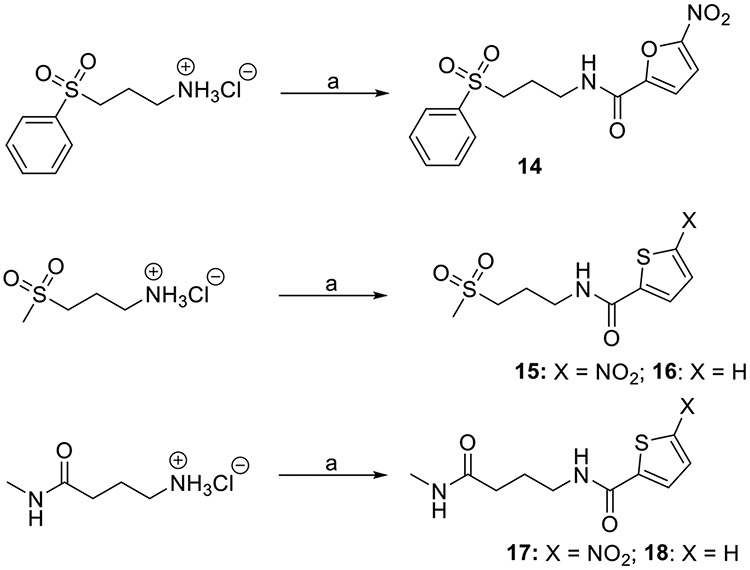

Synthesis of 14-18

Compounds 14-18 were synthesized via amidation reactions between 3-(phenylsulfonyl)propan-1-amine hydrochloride, 3-(methylsulfonyl)propan-1-amine hydrochloride, or 4-amino-N-methylbutanamide hydrochloride and 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (14), 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (15 and 17) or thiophene-2-carboxylic acid (16 and 18) using HBTU as coupling reagent as summarized in Scheme 4 below.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of 14-18. Reagents and conditions: (a) Amine (0.21 mmol), ACN (2 mL), 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid (14), 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (15 and 17) or thiophene-2-carboxylic acid (16 and 18), Et3N (2 mol eq), HBTU (2 mol eq), RT, 16 hr.

5-nitro-N-[3-(phenylsulfonyl)propyl]furan-2-carboxamide (14)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. Furan-2-carboxylic acid (0.32 mmol, 50.3 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, 2H), 7.75 (t, 1H), 7.67 (t, 2H), 7.58 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.53 (q, J = 6.8, 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.35 – 3.32 (m, 2H), 2.03 – 1.95 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 156.4, 148.6, 139.7, 133.7, 129.3, 127.9, 115.4, 112.6, 53.3, 37.6, 23.1. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C14H14N2O6SNa: 361.0470 ; found 361.0468. HPLC: RT = 4.58 min.

N-[3-(methylsulfonyl)propyl]-5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxamide (15)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.29 mmol, 50.2 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.36 (s,1H) 8.02 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (q, 2H), 3.21 (t, 2H), 2.95 (s, 3H), 2.15 – 2.09 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ160.08, 146.3, 129.2, 126.5, 51.7, 39.8, 38.4, 37.8, 22.5. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C9H12N2O5S2Na: 315. 0085; found: 315.0085. HPLC: RT = 4.33 mins.

N-[3-(methylsulfonyl)propyl]thiophene-2-carboxamide (16)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. Thiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.29 mmol, 37.2 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 7.94 (s, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 3.7, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 5.0, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.53 (dd, J = 6.8, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.23 – 3.16 (m, 2H), 2.95 (s, 3H), 2.13 – 2.07 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ161.7, 140.1, 130.3, 127.7, 51.9, 39.8, 38.0, 37.9, 22.9. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C9H13NO3S2Na: 270.0235; found: 270.0240. HPLC: RT = 4.19 mins.

N-[4-(methylamino)-4-oxobutyl]-5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxamide (17)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.33 mmol, 57.1 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.99 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 2.53 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 3H), 2.10 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.73 (p, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 172.5, 159.8, 147.1, 130.8, 127.5, 127.3, 33.1, 25.9, 25.4. HRMS [M-H]− calculated for C10H13N3O4S: 270.0548; found 270.0551. HPLC: RT = 4.26 mins.

N-[4-(methylamino)-4-oxobutyl]thiophene-2-carboxamide (18)

It was synthesized as described in Scheme 3 above. 5-nitrothiophene-2-carboxylic acid (0.33 mmol, 42.3 mg) was used as acid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 8.09 (s, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 3.7, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 5.0, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.11 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (td, J = 6.7, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.69 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H), 2.26 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.86 (p, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 172.8, 161.4, 140.6, 129.9, 127.5, 127.3, 39.3, 33.3, 25.2. HRMS [M-Na]+ calculated for C10H14N2O2SNa: 249. 0674; found: 249.0676. HPLC: RT =4.14 mins.

Bioassays

Trypanosoma b. brucei:

The compounds were evaluated for growth inhibitory activity on bloodstream forms of T. brucei brucei (strain 427) using the Alamar blue assay as previously described [9]. The parasites were cultured in HMI-9-medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10% Serum plus (SAFC), 0.05 mM bathocuproinesulfonate, 1.5 mM L-cysteine, 1 mM hypoxanthine, 0.2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.16 mM thymidine, 1 mM pyruvate. The parasites were dispensed into 96-well plates at a density of 5 x 103 cells/well. The compounds were prepared in a dose range of 0.01–50 μM in DMSO and tested in triplicates at total assay volumes of 100 μL. The parasites were treated for 48 hr, followed by the addition of Alamar blue (20 μL) and incubation at 37°C for 4 hr. Fluorescence signals were read at λex/em 530/590 nm. Suramin was used as positive control with an EC50 of 0.04 ± 0.01 μM.

Trypanosoma b. rhodesiense:

Bloodstream forms of T. b. rhodesiense (STIB 900) were grown in HMI-9-medium supplemented with 0.05 mM bathocuproinesulfonate, 1.5 mM L-cysteine, 1 mM hypoxanthine, 0.2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.16 mM thymidine, 1 mM pyruvate and 15% heat inactivated horse serum. [10]. Serial drug dilutions of eleven 3-fold dilution steps covering 100 to 0.002 μM were prepared in 96-well microplates. Then, 2x104 parasites were added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C under a 5 % CO2 atmosphere for 70 h. 10 μl resazurin solution (resazurin, 12.5 mg in 100 ml in PBS) was then added to each well and incubation continued for a further 2–4 h. Fluorescence signals were read at λex/em 536/588 nm. Melarsoprol (Arsobal Sanofi-Aventis, received from WHO) was used as control with an EC50 of 0.006 ± 0.002 μM.

Trypanosoma b. gambiense assays:

Bloodstream forms of T. b. gcimbiense (130R) were grown in HMI-9-medium supplemented with 0.05 mM bathocuproinesulfonate, 1.5 mM L-cysteine, 1 mM hypoxanthine, 0.2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.16 mM thymidine, 1 mM pyruvate, 15% heat-inactivated fetal calf and 5% human serum. [10]. Serial drug dilutions of eleven 3-fold dilution steps covering 100 to 0.002 μM were prepared in a 96-well microplate. Then 4x104 parasites were added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C under a 5 % CO2 atmosphere for 68 h. 10 μl resazurin solution (resazurin, 12.5 mg in 100 ml in PBS) was then added to each well, and incubation continued for a further 4–6 h. Fluorescence signals were read at λex/em 536/588 nm. Melarsoprol (Arsobal Sanofi-Aventis, received from WHO) was used as control with an EC50 of 0.007 ± 0.003 μM.

Cytotoxicity Assay:

Human hepatocarcinoma cells (Hep G2, CRL-11997TM) were used for cytotoxicity studies previously described [9]. The cells were grown in DMEM:F12 media supplemented with L-glutamine and sodium bicarbonate, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Trypsinized and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-washed cells were dispensed (198 μL) into 96-well microplates at a density of 5 x 105 cells/mL and incubated for 18-24 h. Cells were treated with compounds prepared in DMSO at a dose range of 0.01–300 μM for 72 h. The culture medium was then removed and replaced with DMEM:F12 medium containing MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) and was incubated for 30 minutes. After that, the medium was removed and replaced with DMSO (200 μL) to lyze the cells and dissolve the formazan crystals in the wells. The plates were then incubated for 10 min, and the UV absorbance at 550 nm was measured in each well. The compounds were tested in triplicates. SDS (10%) was used as assay positive control, and podophyllotoxin was used as cytotoxicity control.

tCatL Assay:

tCatL was expressed in Pichia pastoris and purified as previously described [11]. The inhibition assays were carried out as described by Zhang et al., 2020 [8]. E-64 was used as the positive control in the assay. E64 displayed 100% inhibition at 10 μM.

Liver microsomes and S9 Assays:

The in vitro metabolic stability of the compounds was evaluated using mouse liver microsomes and S9 fractions (Eurofins Discovery) as previously described [12]. The compounds (0.1 μM) were exposed to 0.1 mg/mL of microsomes or S9 ± co-factors and incubated for 1 hour. Aliquots were removed every 15 min, quenched with a mixture of ice-cold ACN-methanol, clarified, and analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS. The half-life (t1/2) was estimated from the slope of the initial linear range of the logarithmic curve of percentage compound remaining (%) vs. time [13].

Pharmacokinetics (PK) assay:

The PK analysis of 10 was performed with identical groups of fasted mice (C57BL/6, male, n = 3/group). The mice received compound 10 intravenously (IV, 1 mg/kg) or by oral gavage (PO, 5 mg/kg). The compound was formulated in a solution containing 5% DMSO, 10% solutol, and 85% PBS with Captisol (20%). The dosing volume was 1 mL/kg and 5 mL/kg for IV and PO, respectively. Blood (40 μL) was collected at 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours postdosing for IV and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours postdosing for PO, clarified at 3500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to obtained plasma. Concentrations of the compound at each time point were quantified in clarified plasma using LC-MS/MS. PK parameters were calculated using the non-compartmental analysis model of WinNonlin 8.2 (Certara, Princeton, NJ).

T. b. brucei assay:

The efficacy of 10 was studied using T. bracei–infected BALB/c mice (6-8 weeks old, n = 5/group). The mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 x 105 transgenic T. b. bracei AnTat1.1 trypomastigotes expressing Renilla luciferase. Treatment was initiated three days after infection and lasted for 5 days. A group of infected mice was dosed orally (PO) with 10 prepared in 0.5% Hydroxymethyl cellulose and 0.5% Tween-80 at 100 mg/kg body weight (mpk), and another group was dosed i.p. at 100 mpk. A vehicle control group received PBS containing 0.5% hydroxymethyl cellulose and 0.5% Tween-80 orally, while the positive control group received suramin at 40 mpk intraperitoneally. Luminescence imaging was carried out on day 3 (the day when treatment started) and day 9 (the day after the last treatment) using D-luciferin (15 mg/ml in PBS). Parasite levels were determined by comparing the luminescence intensity signals after treatment. The studies were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at New York University Langone Health (IA16-00829).

T. b. rhodesiense assay:

T. b. rhodesiense parasites modified with pTb-AMluc construct [14] containing red-shifted luciferase reporter gene (PpyRE9h) were used. Five female NMRI mice were used per experimental group. Each mouse was inoculated i.p. with 1 x 104 bloodstream forms of STIB 900-luc, respectively. Compounds were prepared in PBS containing 0.5% hydroxyl-methylcellulose and 0.5% Tween 80. Treatment was initiated 3 days post-infection. The compounds were administered orally and i.p for four consecutive days. Three mice served as infected-untreated controls. Parasitemia was monitored by whole-animal live imaging twice a week after treatment for two weeks, followed by once a week until 60 days post-infection. The mice were imaged as described above. Mice were considered cured if the bioluminescence signal at day 60 post-infection was not higher than the background level. The studies were conducted at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (License number 2813) according to the rules and regulations for the protection of animal rights “Tierschutzverordnung” of the Swiss “Bundesamt fur Veterinärwesen.” and approved by the veterinary office of Canton Baseband, Switzerland.

Results and Discussion

Structure-activity Relationship

In our previous study [8], we found out that compound 1 and its thiophene analog have significant potency against T. brucei (EC50 of 0.11 and 0.69 μM, respectively) with modest selectivity indices (47 and 18, respectively) when their effect on the parasite is compared with their effects on liver cells. Further investigation revealed that 1 is relatively unstable when exposed to human and mouse liver microsomes (HLM and MLM). Its half-life is 10.8 and 22.4 min when treated with HLM and MLM, respectively. Therefore, we sought to investigate analogs of 1 that retain the α,β-unsaturation of the vinyl sulfone warhead, and the nitroaromatic motif and are generally less hydrophobic than 1 (cLogP is 3.5). The T. b. brucei growth assay served as the primary screening tool. As shown in Table 1, Analogues 2 and 3 with the 2-methyl-5-nitroimidazole and 5-nitropyrrole motifs have very weak antitrypanosomal activity. Removing the phenylethyl motif in 4 and 5 while retaining the nitrofuran/nitrothiophene produced modest antitrypanosomal activity compared with 1. However, replacing the phenyl group in the vinyl sulfone warhead with methyl groups in 7 and 8 led to significant improvements in selectivity indices and potency.

Table 1. Antitrypanosomal activity of compounds 2-18.

Compounds were assayed as described in the experimental section. EC50 is the concentration that caused half-maximal trypanosomal viability. CC50 is the concentration that caused half-maximal cellular viability. SI is the selectivity index (CC50/EC50). Suramin (EC50 = 0.04±0.001 μM) was the positive control in T. b. b assays. Melarsoprol (EC50 = 0.01±0.001 μM) was the positive control in T. b. r and T. b. g assays. a Percentage inhibition of tCatL at 10 μM after 1 hour. T.b.b: Trypanosoma brucei brucei; T.b.r: Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense; T.b.g: Trypanosoma brucei gambiense.

| Entry | General Formulae | R |

T.b.b/T.b.g/T.b.r EC50 (μM) |

Hep G2 CC50 (μM) |

SI | MLM and S9 t1/2 (mins) |

tCatLa (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

T.b.b: 0.11±0.01 T.b.r: 2.73±0.57 T.b.g: 0.07±0.03 |

5.17±1.17 | 47.00 1.89 73.85 |

22.40 | 78.08±0.69 |

| 2 |

|

|

T.b.b: >50 | >300 | - | 44.11±1.95 | |

| 3 |

|

T.b.b: 31.2 ± 2.10 | >160.00 | >5.13 | 26.74±2.72 | ||

| 4 |

|

|

T.b.b: 6.35±0.48 T.b.r: 0.61±0.10 T.b.g: 0.32±0.07 |

20.42±0.12 | 3.21 33.47 63.81 |

||

| 5 |

|

T.b.b: 0.98±0.15 T.b.r: 1.77±0.08 T.b.g: 0.20±0.01 |

59.36±0.12 | 60.57 33.53 296.60 |

>60 and 12.99 | 17.72±0.01 | |

| 6 |

|

|

T.b.b: 1.95±0.12 | 66.34±0.09 | 34.02 | 30.65±3.62 | |

| 7 |

|

|

T.b.b: 0.44±0.05 T.b.r: 0.05±0.02 T.b.g: 0.06±0.01 |

21.76±0.11 | 49.45 435.20 362.66 |

>60 | 21.18±2.49 |

| 8 |

|

T.b.b: 0.64±0.02 T.b.r: 0.12±0.03 T.b.g: 0.25±0.06 |

98.65±0.11 | 154.14 822.08 394.60 |

>60 and >60 | 23.25±0.77 | |

| 9 |

|

T.b.b: >30 | >300.00 | - | 23.58±0.13 | ||

| 10 |

|

|

T.b.b: 0.54±0.10 T.b.r: 0.14±0.05 T.b.g: 0.13±0.02 |

>75 | >138.88 >535.71 >576.92 |

>60 and >60 | 43.87±0.15 |

| 11 |

|

T.b.b: 1.69±0.39 T.b.r: 0.22±0.04 T.b.g: 0.47±0.01 |

>75 | >44.38 >340.91 >159.57 |

16.99±3.69 | ||

| 12 |

|

|

T.b.b: 0.30±0.04 T.b.r: 0.14±0.01 T.b.g: 0.06±0.02 |

41.67±0.10 | 138.9 297.64 694.5 |

>60 and 20.49 | 54.77±2.59 |

| 13 |

|

T.b.b: 0.18±0.08 T.b.r: 0.04±0.01 T.b.g: 0.03±0.01 |

60.00±0.11 | 333.33 1500 2000 |

>60 and 19.49 | 58.40±1.20 | |

| 14 |

|

|

T.b.b: 0.99±0.04 | 44.55±0.10 | 45 | 15.01±4.24 | |

| 15 |

|

|

T.b.b: 1.29±0.17 | 98.57±0.08 | 76.41 | 11.05±0.55 | |

| 16 |

|

T.b.b: >30 | >150 | - | inactive | ||

| 17 |

|

|

T.b.b: 4.12±0.45 T.b.r: 1.96±0.12 T.b.g: 1.88±0.13 |

69.53±0.07 | 16.87 35.47 36.98 |

inactive | |

| 18 |

|

T.b.b: >30 | >300 | - | inactive |

As expected, the lack of the phenethyl motif in 4-11 and 14-18 significantly reduced their inhibitory effect on tCatL. While it is desirable to have compounds with strong inhibitory activities against tCatL, our preliminary analysis of molecules with high reactivity towards trypanosomal cathepsins is that such molecules tend to have a high clearance rate.

Consequently, compounds with 4-(methylamino)-4-oxobut-2-en-1-yl motif (10-13) were investigated as bioisosteric replacements for the methyl vinyl sulfone warhead in 7 and 8. As shown in Table 1, compounds 10, 12, and 13 are active against T. b. brucei (EC50 = 0.54, 0.30, and 0.18 μM, respectively), while 11 has relatively weaker activity against T. b. brucei (EC50 = 1.69 μM). Therefore, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10-14, compounds with very promising activity against T. b. brucei, were screened against T. b. gcimbiense and T. b. rhodesiense. All but compound 4 have EC50 values less than 700 nM against both T. b. gcimbiense and T. b. rhodesiense. While the EC50 of 4 against T. b. rhodesiense is as low as 200 μM, the EC50 values of 7, 13, and 14 are 60, 60, and 30 nM, respectively.

To investigate the individual and combined contributions of the α,β-unsaturation in the covalent warhead and the nitro group to the antitrypanosomal activity of the compounds, compounds 6, 9, and 14-18 were synthesized and tested against T. b. brucei. The results revealed that 6 and 9, analogs of 4 and 5 that lack the nitro motif, have weaker activity against T. b. brucei. However, there is no difference between the EC50 of 14 (0.99 μM, lacks the unsaturation) and 5 (0.98 μM). Interestingly, compound 6 (lacks the nitro moiety) is still moderately active (EC50 = 1.92 μM) against the parasite when compared to 9 (lacks the nitro moiety, EC50 >30 μM). The loss of the α,β-unsaturation have a stronger impact on the activity of 15 and 17 (EC50 values are 1.29 and 4.12 μM, respectively) relative to 8 and 10 (EC50 values are 0.64 and 0.54 μM, respectively). The loss of αβ-unsaturation in 17 made it one order of magnitude less active towards T. b. gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense than its unsaturated congener 10. Overall, compounds with the unsaturation relative to their saturated congeners, except for 14, were 2-10 fold more potent. It is worth noting that a relatively small number of congeners was evaluated, and a larger library of compounds might result in a different conclusion. It is very likely that the observed antitrypanosomal activities of this series of compounds are the combined effects of weak inhibition of tCatL and a strong bioactivation of the nitro moiety into reactive trypanocidal moieties. We envisage that dual-active molecules, especially with potent but metabolically stable motifs for tCatL inhibition, could exert significantly stronger pressure against the development of drug resistance by trypanosomes when compared to molecules that can only inhibit tCatL or that have a bioactive nitro moiety.

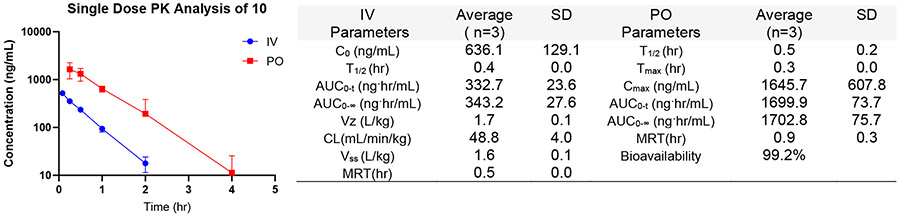

In vitro metabolism and in vivo PK of 10

As part of the testing cascade following the T. brucei growth and cytotoxicity assays, the metabolic stability of 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, and 13 to MLM and S9 fractions were evaluated based on their promising selectivity indices. The compounds were stable to mouse liver microsomes with half-life > 60 mins, but 5, 12, and 13 have a much lower half-life when treated with mouse S9 fraction (Table 1). Therefore, compounds 8 and 10 were identified as candidates for in vivo efficacy studies in mouse models. Subsequently, compound 10 was evaluated in a single-dose pharmacokinetics experiment. As presented in Figure 2 below, 10 is absorbed rapidly (Tmax = 0.3 hr) with high bioavailability (99.2%) at 5 mpk. It has a relatively high peak serum concentration (Cmax = 1645.7 ng/mL), but its half-life is relatively short (T1/2 = 0.5 hr). However, its plasma concentration (0.72 μM) at 2 hr is more than 3 times the EC90 (0.21 μM) of 10 for T. b. rhodesiense. The short half-life may necessitate frequent dosing or a more extended treatment regime with 10.

Figure 2.

PK plot and parameters of 10. The IV dose was administered at 1 mpk, and the PO dose was at 5 mpk in 5% DMSO/10% Solutol/85% PBS (containing 20% Captisol).

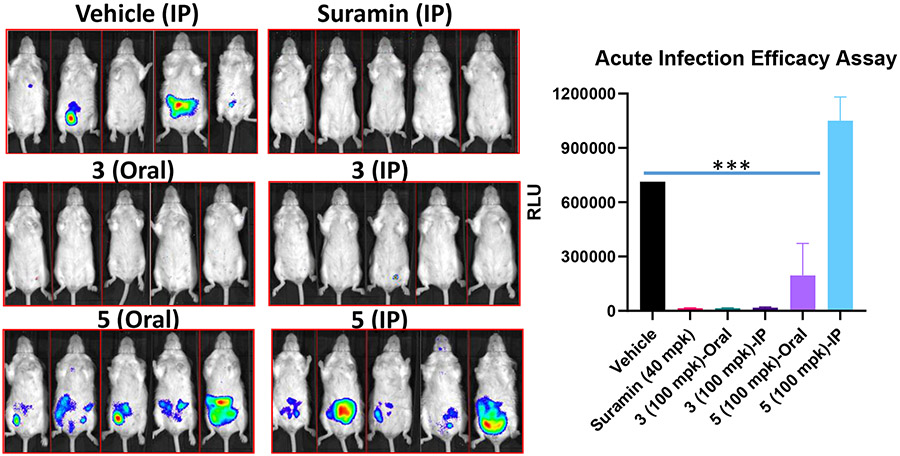

Acute in vivo Efficacy Study in Mice Models

Compounds 7 and 10 were evaluated for their potential to suppress T. brucei brncei infection in mouse models. The mice were infected with T. b. brncei AnTat1.1 trypomastigotes expressing Renilla luciferase. The compounds were administered at 100 mpk to separate groups of mice (n = 5) via oral gavage or intraperitoneally for 5 consecutive days. As shown in Figure 3 below, 10 suppressed parasite growth in vivo when administered orally and intraperitoneally. Oral administration of 7 at 100 mpk also reduced parasitemia, but IP administration at the same dose was ineffective.

Figure 3.

Mice were infected with 1 x 105 T. b. brucei trypomastigotes and treated for 5 days via IP or oral gavage. Vehicle: 0.5% Hydroxymethyl cellulose + 0.5% Tween-80. RLU: relative luminescence reading for T. brucei-Luc parasites. *** P value is < 0.0001 relative to the vehicle. Parasite density color key: Red: very high; Yellow: high; Green: medium; Blue: low

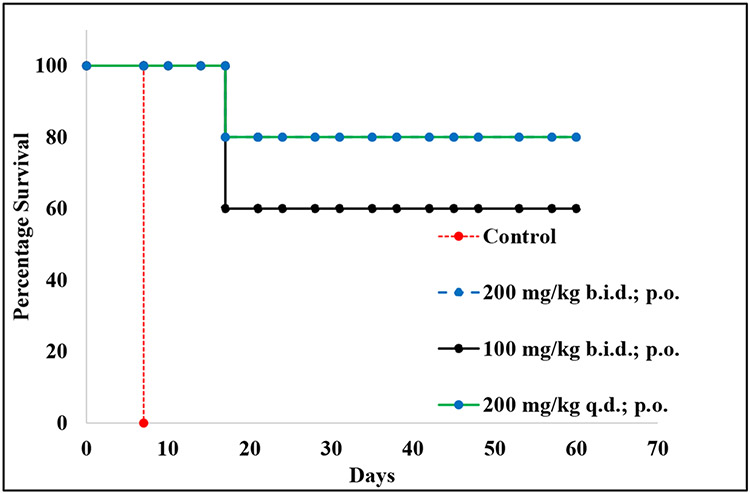

Based on the promising results from the T. b. brucei assay, compound 10 was also evaluated in acute infection mouse models of T. b. rhodesiense. Compound 10 was administered via oral gavage at 100 mpk twice a day, 200 mpk twice daily, and 200 mpk once daily for four days. As expected, the control animals had very high parasitemia by day 7 and were euthanized. However, 4 out of 5 animals that received 200 mpk of 10 once or twice a day survived up to 60 days, with no detectable level of parasitemia, when the experiment was terminated. Similarly, 3 out of 5 animals treated with 100 mpk b.i.d, orally, survived until the end of the experiment 60 days (Figure 4). As a result of the dose-related efficacy, our current hypothesis is that compound 10 might produce 100% survival when administered for a more extended treatment period (5-10 days). Ongoing studies are focused on investigating the ability of 10 to treat chronic infections in mice models. In a broader context but in similar experiments, fexinidazole, an oral drug for HAT, can treat 4 out of 4 infected mice at 100 mpk once a day, as previously reported. Fexinidazole is also rapidly absorbed (Tmax = 0.25 h) like 10 but has a longer half-life (0.8 hr vs 0.5 hr for 10), although fexinidazole was administered at 5 times (25 mpk) the dose used in the PK study of 10 (5 mpk).

Figure 4. The survival plot of T. brucei rhodesiense-infected mouse models treated with 10.

The percentage survival is the ratio of surviving animals over the total number of mice in each group (5 animals per group). The points represent the percent survival at each day. Treatment started on day 3 after infection and continued until day 7, as described in the methods section. B.i.d = twice a day; q.d = once a day.

Conclusion

The SAR from this work revealed that replacing the phenethyl side chain and the phenyl vinyl sulfone with H and methyl vinyl sulfone reduces the metabolic liability of the compound series. Because of the potency of compounds 12 and 13, especially on T. b. rhodesiense and T. b. gambiense, it is particularly attractive to explore the bioisosteric replacement of the phenethyl side chain with a desire to maintain the antitrypanosomal potency while enhancing metabolic stability. Compound 10 is absorbed rapidly, has excellent bioavailability, and suppresses infection in acute mouse models of animal and human trypanosomiasis. It is conceivable that 10 could be used as one of the active ingredients in combination therapies for HAT [17-22]. Ongoing studies are focused on treating chronic infection models with 10 and lead optimization of 10, 12, and 13 to enhance tCatL inhibition, metabolic stability, and in vivo efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

New antitrypanosomal agents were investigated in this work.

A multiparameter optimization of bioactivity led to drug lead candidate 10.

The drug lead has excellent oral bioavailability.

The drug lead (10) has in vivo efficacy in mouse models of human African trypanosomiasis (HAT).

Acknowledgments

We thank Huaisheng Zhang and Bosede Kolawole at Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, for the helpful discussions and technical assistance provided during this work. We also thank Monica Cal, Romina Rocchetti, and Sonja Keller-Märki at Swiss TPH for assistance with the in vitro and in vivo parasite assays.

Funding

This work was carried out in part by resources made available by the US National Institutes of Health (SC1GM140990). OA was supported by The US National Science Foundation (DMR-1826886).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information

Supplementary 1H, 13C, and HRMS spectra are provided as supporting information.

Ifedayo Victor Ogungbe reports financial support was provided by National Institute of Health. Ifedayo Victor Ogungbe reports financial support was provided by National Science Foundation. Ifedayo Victor Ogungbe reports a relationship with Biomolecular Science LLC that includes: equity or stocks. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Kennedy P. Update on human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Journal of Neurology, 2019, 266, 2334–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis C; Rock K; Mwamba Miaka E; Keeling M Village-scale persistence and elimination of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2019, 13, e0007838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franco JR; Cecchi G; Paone M; Diarra A; Grout L; Ebeja AK; Simarro PP; Zhao W; Argaw D The Elimination of Human African Trypanosomiasis: Achievements in Relation to WHO Road Map Targets for 2020. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2022, 16, e0010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindner A; Lejon V; Chappuis F; Seixas J; Kazumba L; Barrett M; Mwamba E; Erphas O; Akl E; Villanueva G; Bergman H; Simarro P; Kadima Ebeja A; Priotto G; Franco J New WHO guidelines for treatment of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis including fexinidazole: substantial changes for clinical practice. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2020, 20, e38–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelfrene E; Harvey Allchurch M; Ntamabyaliro N; Nambasa V; Ventura F; Nagercoil N; Cavaleri M The European Medicines Agency’s scientific opinion on oral fexinidazole for human African trypanosomiasis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2019, 13, e0007381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lutje V; Probyn K; Seixas J; Bergman H; Villanueva G Chemotherapy for Second-Stage Human African Trypanosomiasis: Drugs in Use. The Cochrane Library, 2021, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumeso VKB; Kalonji WM; Rembry S; Mordt OV; Tete DN; Prêtre A; Delhomme S; Kyhi MIW; Camara M; Catusse J; Schneitter S; Nusbaumer M; Miaka EM; Mbembo HM; Mayawula JM; Camara M; Massa FA; Badibabi LK; Bonama AK; Lukula PK; Kalonji SM; Philemon PM; Nganyonyi RM; Mankiara HE; Nguba AAA; Muanza VK; Nasandhel EM; Bambuwu AFN; Scherrer B; Strub-Wourgaft N; Tarral A Efficacy and Safety of Acoziborole in Patients with Human African Trypanosomiasis Caused by Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase 2/3 Trial. Lancet Infections Diseases, 2023, 23, 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H; Collins JT; Nyamwihura R; Crown OO; Ajayi O; Ogungbe IV Vinyl Sulfone-Based Inhibitors of Trypanosomal Cysteine Protease Rhodesain with Improved Antitrypanosomal Activities. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2020, 30, 127217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould MK; Vu XL; Seebeck T; De Koning HP Propidium Iodide-Based Methods for Monitoring Drug Action in the Kinetoplastidae: Comparison with the Alamar Blue Assay. Analytical Biochemistry, 2008, 382, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H; Collins JT; Nyamwihura R; Ware S; Kaiser M; Ogungbe IV Discovery of a Quinoline-Based Phenyl Sulfone Derivative as an Antitrypanosomal Agent. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2018, 28, 1647–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caffrey C; Hansell E; Lucas K; Brinen L; Hernandez A; Cheng J; Gwaltney II S; Roush W; Stierhof Y; Bogyo M; Steverding D Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 2001, 118, 61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ackley DC; Rockich K; Baker TR Metabolic Stability Assessed by Liver Microsomes and Hepatocytes. In: Humana Press eBooks; 2004; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wacher VJ; Wu C; Benet LZ Overlapping Substrate Specificities and Tissue Distribution of Cytochrome P450 3A and P-Glycoprotein: Implications for Drug Delivery and Activity in Cancer Chemotherapy. Molecular Carcinogenesis, 1995, 13, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLatchie AP; Burrell-Saward H; Myburgh E; Lewis MD; Ward TH; Mottram JC; Croft SL; Kelly JM; Taylor MC Highly Sensitive In Vivo Imaging of Trypanosoma Brucei Expressing “Red-Shifted” Luciferase. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2013, 7, e2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torreele E; Trunz BB; Tweats D; Kaiser M; Bran R; Mazué G; Bray MA; Pécoul B Fexinidazole – A New Oral Nitroimidazole Drug Candidate Entering Clinical Development for the Treatment of Sleeping Sickness. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2010, 4, e923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser M; Bray MA; Cal M; Trunz BB; Torreele E; Brun R Antitrypanosomal Activity of Fexinidazole, a New Oral Nitroimidazole Drug Candidate for Treatment of Sleeping Sickness. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2011, 55, 5602–5608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyllie S; Foth B; Kelner A; Sokolova A; Berriman M; Fairlamb A Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2015, 71, 625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos M; Phelan J; Francisco A; Taylor M; Fewis M; Pain A; Clark T; Kelly J Scientific Reports, 2017, 7, 14407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson S; Wyllie S Trends in Parasitology, 2014, 30, 289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mejia A; Hall B; Taylor M; Gómez-Palacio A; Wilkinson S; Triana-Chávez O; Kelly J The Journal of Infections Diseases, 2012, 206, 220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson S; Taylor M; Horn D; Kelly J; Cheeseman I Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2008, 105, 5022–5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson J; Ricker N; Sirjusingh C Eukaryotic Cell, 2006, 5, 1243–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.