Abstract

Differences in social motivation underlie the core social-communication features of autism according to several theoretical models, with decreased social motivation among autistic youth relative to neurotypical peers. However, research on social motivation often relies on caregiver reports and rarely includes firsthand perspectives of children and adolescents with autism. Furthermore, social motivation is typically assumed to be constant across social settings when it may actually vary by social context. Among a sample of 58 verbally fluent youth (8-13 years old; 22 with autism, 36 neurotypical), we examined correspondence between youth and caregiver reports of social motivation with peers and with adults, as well as diagnostic group differences and associations with social outcomes. Results suggest youth and caregivers provide overlapping but distinct information. Autistic youth had lower levels of social motivation relative to neurotypical youth, and reported relatively consistent motivation toward peers and adults. Youth self- and caregiver-report were correlated for motivation toward adults, but not toward peers. Despite low correspondence between self- and caregiver-reported motivation toward peers, autistic youths’ self-report corresponded to caregiver-reported social skills and difficulties whereas caregiver-report of peer motivation did not. For neurotypical youth, self- and caregiver-reported motivation toward adults was correlated, but motivation by both reporters was largely independent of broader social outcomes. Findings highlight the unique value of self-report among autistic children and adolescents, and warrant additional work exploring the development, structure, and correlates of social motivation among autistic and neurotypical youth.

Keywords: autism, social motivation, self-report, social skill, reporter agreement

Lay Summary

Researchers studying social motivation in autistic youth often measure it through caregiver-report questionnaires, and rarely ask youth directly about their social experiences. We collected social motivation questionnaires from autistic and neurotypical youth ages 8-13 years and their caregivers, and found that they often agree on their social motivation with adults, but have less agreement on their social motivation with peers. When compared to other social outcomes, we found that autistic youths’ self-reported motivation may correspond better than caregiver reports with those outcomes. We conclude that youth and caregivers contribute overlapping but distinct information about youths’ social experiences.

Introduction

Differences in social motivation from very early in life underlie the core social-communication features observed in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), according to several theoretical models (Chevallier et al., 2012; Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005; Dawson, Webb, Wijsman, et al., 2005; Mundy, 1995). By these accounts, decreased social motivation during infancy contributes to reduced social orienting, attention, and engagement, creating fewer instances for social learning and promoting a trajectory of increasing social and communication differences between autistic and nonautistic youth over time (Chevallier et al., 2012). Consistent with these theories, trajectories of social motivation over the first 24 months of life are predictive of later autism diagnosis and appear to track with autism likelihood based on family history (Marrus et al., 2022). Important to this model is a distinction between social motivation, which emerges very early in life as oxytocin facilitates integration of social stimuli (e.g., faces, voices) into dopaminergic reward mechanisms (Dawson, 2008; Dawson, Webb, Wijsman, et al., 2005), and social skill, which reflects the dynamic outcome of developmental processes.

Among children and adolescents, caregiver-report measures indicate lower mean social motivation among autistic youth relative to peers (Neuhaus et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2019), as do findings from behavioral response to social versus nonsocial reward (Aldridge-Waddon et al., 2020) and neurobiological markers of brain connectivity and activation to a range of different social stimuli (Abrams et al., 2013; Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005; Kohls et al., 2012). Beyond diagnostic group differences, existing research also documents associations between individual differences in social motivation and other important social and communication outcomes. Longitudinally, infants’ social motivation at 14-30 months of age predicts language skills two years later (Su et al., 2021), and higher levels of parent-reported social motivation among school-age children with autism correspond to stronger social skills and fewer social difficulties (Itskovich et al., 2021; Neuhaus et al., 2020).

Markedly absent from most research of social motivation are subjective reports from autistic individuals – particularly children and adolescents – despite the valuable firsthand insight they can provide. The Social Motivation Interview (Elias & White, 2020) is a rare exception, in which youth and a caregiver are interviewed jointly regarding multiple facets of social motivation, yielding rich firsthand information with promising psychometric properties and strong family satisfaction (Elias & White, 2020). Further evidence of the value of self-report among this population comes from findings that autistic youth are able to report on their own personality traits, and their self-reports correspond to their parents’ reports at levels comparable to neurotypical youth (Schriber et al., 2014). Similarly, psychophysiological work suggests that autistic adolescents are able to report effectively on their own auditory sensitivities and anxiety symptoms; moreover, their reports correspond more closely to measures of autonomic arousal than the reports of their parents (Keith et al., 2019). Collectively, these findings argue that youth with ASD offer unique, valid, and valuable insights into their internal social-emotional experiences, and suggest that self-reported social motivation may be equally, if not more, informative than caregiver-report.

Adding complexity to this discussion is the question of how best to conceptualize social motivation with regard to structure and stability. Whether motivation more broadly reflects a trait intrinsic to the individual, a more transient state, or an interaction between dispositional and situational factors, has long been debated (Carver & White, 1994; Harmon-Jones et al., 2013; Panksepp, 2004), and this question can be extended to social motivation as well. Though often construed and measured as a unidimensional construct that holds constant across social interactions, the extent to which social motivation may in fact vary across social settings or across instances is largely unexplored. For example, a child’s motivation may be moderated by social setting and partner, such that motivation to engage with same-age peers differs from motivation to engage with adults, potentially suggesting separable dimensions within the larger construct.

In this study, we sought to explore self- and caregiver-reported social motivation in children with and without ASD. We focused on school-age children, who presumably participate in a variety of social settings (e.g., home, school, extracurricular activities) and for whom self-report of internal experience is developmentally plausible. In addition to considering the role of the reporter, we sought to understand variation in social motivation across social contexts and partners. Accordingly, we assessed motivation with peers and with adults, and examined (1) correspondence between self- and caregiver-report of social motivation in both social contexts; (2) group differences in social motivation by reporter and social context; and (3) associations between social motivation and other social outcomes by reporter and social context.

Method

Procedure:

Data presented here were collected as part of a study examining social motivation and reward among youth with and without autism. Families were recruited from previous research projects, local clinics and organizations, and community settings. Over the course of an in-person visit and a clinician phone call, children completed EEG collection while playing a computerized game, a brief cognitive assessment, a novel behavioral task, and a set of questionnaires (from which the current data come). Diagnostic evaluation was also completed for participants with ASD. Caregivers completed questionnaires and interviews for adaptive skills and developmental history.

Participants:

A total of 58 verbally fluent children from 8 to 13 years of age (mean = 10.2 years, SD=1.4, range=8.0-12.9) were enrolled. Of this total, 22 youth had a diagnosis of ASD (ASD group), confirmed clinically on the basis of the ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2012), ADI-R (Lord et al., 1994), and DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This group comprised 4 participants assigned female at birth and 18 assigned male at birth. The remaining 36 participants did not have an ASD diagnosis (neurotypical (NT) group), and were divided evenly with regard to sex assigned at birth (18 assigned female at birth). See Table 1 for descriptive information, and refer to (Neuhaus et al., 2020) for additional sample characteristics.

Table 1:

Participant characteristics by diagnostic group

| ASD | NT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Age (years) | 10.2 (1.5) | 8.0-12.9 | 10.2 (1.3) | 8.3-12.9 |

|

| ||||

| Cognitive (DAS-II)1 | ||||

| Verbal (Word Definitions) | 50.6 (9.3) | 34.0-71.0 | 60.2 (10.9) | 44.0-90.0 |

| Nonverbal (Matrix Reasoning) | 56.9 (10.5) | 41.0-79.0 | 57.0 (10.4) | 24.0-80.0 |

|

| ||||

| DMQ-17 (Self-report) | ||||

| Persistence with peers | 3.2 (0.9) | 1.3-4.8 | 3.8 (0.6) | 2.5-5.0 |

| Persistence with adults | 3.1 (1.0) | 1.0-4.8 | 3.5 (0.7) | 1.7-4.7 |

|

| ||||

| DMQ-17 (Caregiver-report) | ||||

| Persistence with peers | 3.2 (0.9) | 1.5-4.7 | 4.1 (0.6) | 2.7-5.0 |

| Persistence with adults | 3.4 (0.9) | 1.7-4.7 | 4.0 (0.6) | 2.8-5.0 |

|

| ||||

| Vineland-2 Socialization2 | 80.4 (9.9) | 62.0-100.0 | 102.8 (8.9) | 89.0-124.0 |

|

| ||||

| CBCL Social Problems1 | 60.7 (7.3) | 50.0-75.0 | 52.5 (3.8) | 50.0-67.0 |

Note:

T-scores with mean of 50.

standard scores with mean of 100. DAS-II, Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 2007); DMQ-17, Dimensions of Mastery Questionnaire, 17th Edition (Morgan et al., 2009); Vineland-2, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd Edition (Sparrow et al., 2005); CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Measures:

Social motivation was assessed through both youth and caregiver report, with the self-report and parent-report versions of the Dimensions of Mastery Questionnaire, 17th edition (DMQ-17), respectively (Morgan et al., 2009). The DMQ-17 contains 45 statements, each of which are rated on a 5-point Likert-scale according to “how typical” they are for each child. Responses to subsets of those items yield two indices of social motivation: (1) Social Persistence with Children, and (2) Social Persistence with Adults. Both indices reflect a child’s typical effort toward (e.g., “I try hard to make friends with other kids.”, “I try to get included when other children are playing.”) and enjoyment of (e.g., “I like to talk with other kids and do it often.”, “Enjoys talking with adults, and tries to keep them interested.”) social interactions and relationships with others (Morgan et al., 2009). Used in conjunction, these measures provided a 2 x 2 matrix assessing social motivation across two reporters (self, caregiver) and two social contexts (peers, adults).

Participants’ broader social outcomes were assessed via caregiver-report using two standardized measures that generate age- and sex-normed scores. Social skills were measured with the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd Edition (Vineland-2) Socialization Domain standard score (Sparrow et al., 2005). This domain contains items related to interpersonal relationships (e.g., participation and understanding of friendships, personal space, conversational skills, empathy), play and leisure (e.g., sharing and taking turns, engaging in play with others, cooperation), and coping skills (e.g., understanding of social norms and cues). Social difficulties were measured with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Social Problems T-score (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), which includes items related to loneliness, dependence, and social conflicts.

Analytic Approach:

To better understand the nature of social motivation in our sample, we first examined the internal consistency of each of the social motivation indices within ASD and neurotypical groups by computing Cronbach’s alpha. Stability of social motivation across contexts was then evaluated for each group by computing correlations between motivation toward peers vs adults, for self-report and caregiver-report separately.

Next, correspondence between self- and caregiver-report of social motivation was assessed with bivariate correlations, which were then compared across diagnostic groups and social contexts.

To consider differences in social motivation across diagnostic groups, reporters, and social context, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was computed to test for effects of between (group: ASD, NT) and within (reporter: self, caregiver; social context: peers, adults) subjects factors within a single model.

Finally, associations between social motivation and broader social outcomes were examined through correlations, both across and within groups. Throughout the study, we applied a conventional p-value threshold of p < .05 for interpreting results.

Results

Internal consistency and stability of social motivation measures

Internal consistency was variable across our indices of social motivation (values for each are presented in Table 2). Although guidelines for interpretation of Cronbach’s alpha are inconsistent (Taber, 2018), all values for the ASD group were acceptable by conventional standards, ranging from .70 (self-reported persistence with peers) to .83 (caregiver-reported persistence with peers). For the NT group, values ranged from .54 (self-reported persistence with peers) to .82 (caregiver-reported persistence with adults). While values for caregiver-report indices were acceptable, values for NT youth self-report fell below preferred thresholds.

Table 2:

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for measures of social motivation by group, reporter, and social context

| Youth self-report | Caregiver report | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Persistence with peers | Persistence with adults | Persistence with peers | Persistence with adults | |

| ASD group | .70 | .78 | .83 | .82 |

| NT group | .54 | .60 | .79 | .82 |

Note: Social motivation in peer and adult social context assessed with Persistence with Peers and Persistence with Adults subscales, respectively, from the Dimensions of Mastery Questionnaire, 17th Edition (Morgan et al., 2009).

Table 3 presents within-reporter correlations for social motivation with peers and adults. For the full sample, youth self-reported motivation with peers and adults was positively correlated, r = .56, p < .001, such that greater motivation in one social context was associated with greater motivation in the other. Within the ASD diagnostic group alone, this pattern persisted, r = .74, p = .001. However, within the NT group, the correlation did not reach significance, r = .33, p = .06. With regard to caregiver-reported motivation across social contexts, no significant correlations were observed for the full sample, r = .26, p = .055, nor for the ASD, r = .05, p = .83, nor NT, r = .13, p = .48, groups.

Table 3:

Correlations between motivation with peers and motivation with adults, within reporters, for the full sample and by group

| Reporter | ||

|---|---|---|

| Youth Self-Report | Caregiver-Report | |

| Full sample |

r = .56, p < .001 95% CI [.33, .73] N = 49 |

r = .26, p = .055 95% CI [−.01, .49] N = 55 |

|

| ||

| ASD Group |

r = .74, p = .001 95% CI [.39, .90] N = 16 |

r = .05, p = .83 95% CI [−.40, .48] N = 20 |

|

| ||

| NT Group |

r = .33, p = .06 95% CI [−.02, .60] N = 33 |

r = .13, p = .48 95% CI [−.22, .44] N = 35 |

|

| ||

| Fisher r-to-z (two-tailed) | z = 1.83, p = .067 | z = 0.27, p = .787 |

Correspondence between self- and caregiver-report of social motivation

As shown in Table 4, for the sample as a whole, child self-reports and caregiver reports of social motivation were positively correlated with respect to peer interactions, r = .38, p = .006, as well as adult interactions, r = .56, p < .001. Within the ASD group, reports were positively correlated for persistence with adults, r = .53, p = .029, but not with peers, r = .03, p = .897, indicating differing perspectives on social motivation within the peer social context. Among the NT group, reporters were again positively correlated for adult persistence, r = .55, p = .001, but the correlation in the context of peers did not reach significance, r = .32, p = .061.

Table 4:

Correlations between child self-report and caregiver-report of social motivation by social context for the full sample and by group

| Social Context | ||

|---|---|---|

| Peers | Adults | |

| Full sample |

r = .38, p = .006 95% CI [.12, .59] N = 52 |

r = .56, p < .001 95% CI [.33, .73] N = 49 |

|

| ||

| ASD Group |

r = .03, p = .897 95% CI [−.45, .51] N = 17 |

r = .53, p = .029 95% CI [.07, .81] N = 17 |

|

| ||

| NT Group |

r = .32, p = .061 95% CI [−.02, .59] N = 35 |

r = .55, p = .001 95% CI [.25, .75] N = 32 |

|

| ||

| Fisher r-to-z (two-tailed) | z = 0.94, p = .347 | z = 0.09, p = .928 |

Note: Social motivation in peer and adult social context assessed with Persistence with Peers and Persistence with Adults subscales, respectively, from the Dimensions of Mastery Questionnaire, 17th Edition (Morgan et al., 2009).

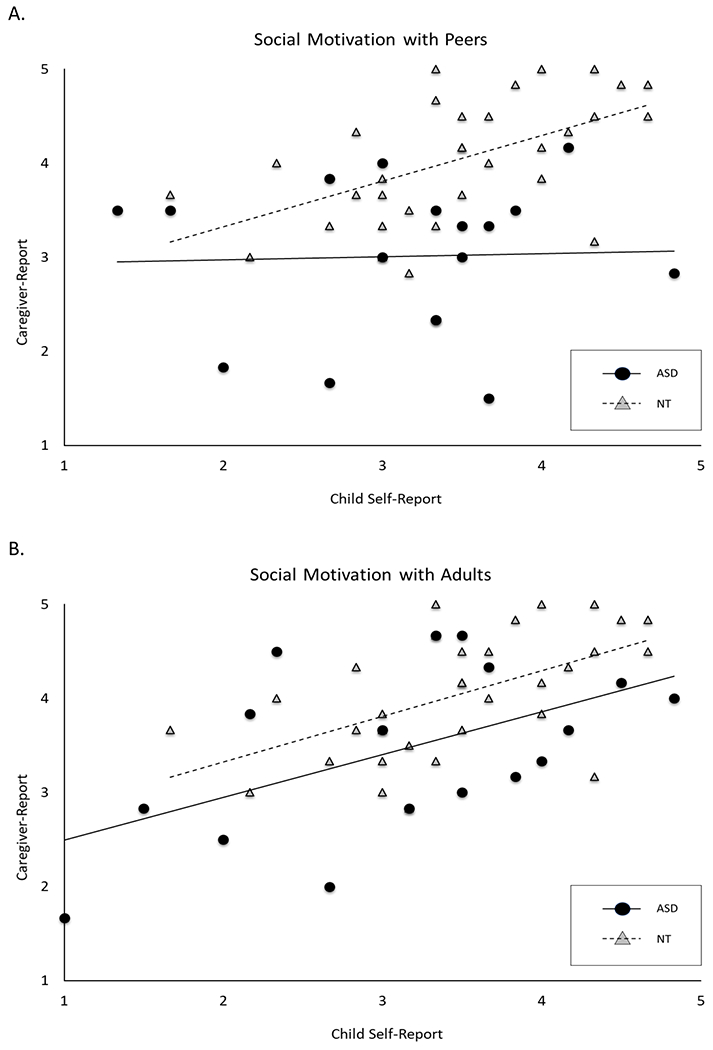

Inspection of r-values suggested that correspondence may differ between groups with regard to peers, but results of Fisher’s r-to-z tests (two-tailed) comparing correlations across the ASD and NT groups did not reach significance, z = 0.94, p = .347. Although likely constrained by the study sample size, tests indicated that the strength of correlations did not differ between the ASD and NT groups in either social context. See Figure 1 for scatter plots.

Figure 1.

Correspondence between youth self-report and caregiver-report of social motivation by diagnostic group and social context

Group comparisons of social motivation by reporter and social context

Group differences in social motivation were then examined with a 2 (diagnostic group) x 2 (reporter) x 2 (social context) ANOVA. See Figures 2 and 3 for box plots and histograms, respectively. The omnibus ANOVA revealed significant main effects of reporter, F(1, 45) = 6.57, p = .014, partial eta2 = 0.13, such that caregiver ratings of social motivation were higher on average than youth self-reported motivation. The main effect of diagnostic group was also significant, F(1, 45) = 16.80, p < .001, partial eta2 = .27, such that ratings of social motivation were higher for the NT group than for the ASD group. A marginally significant interaction between reporter and social context was also observed but did not reach statistical significance, F(1, 45) = 3.32, p = .075, partial eta2 = 0.07.

Figure 2.

Social motivation with peers and adults by diagnostic group and reporter

Figure 3.

Distributions of social motivation for the full sample and diagnostic groups by (A) youth self-report and (B) caregiver-report

Associations between social motivation and social outcomes by reporter and social context

Correlations between social motivation and broader social outcomes are presented in Table 5, first for the full sample and then separately for ASD and NT groups.

Table 5.

Correlations between measures of social motivation by reporter and context

| Youth self-report | Caregiver report | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Persistence with peers | Persistence with adults | Persistence with peers | Persistence with adults | |

| Full Sample | ||||

| Vineland-2 Socialization1 |

r = .47, p < .001 95% CI [.23, .65] |

r = .34, p = .015 95% CI [.07, .56] |

r = .37, p = .006 95% CI [.11, .58] |

r = .44, p < .011 95% CI [.20, .63] |

| CBCL Social Problems2 |

r = −.55, p < .001 95% CI [−.71, −.33] |

r = −.35, p = .011 95% CI [−.57, −.09] |

r = −.23, p = .09 95% CI [−.47, .04] |

r = −.31, p = .02 95% CI [−.53, −.05] |

|

| ||||

| ASD group | ||||

| Vineland-2 Socialization |

r = .49, p = .04 95% CI [.03, .78] |

r = .54, p = .022 95% CI [.09, .80] |

r = −.17, p = .465 95% CI [−.57, .29] |

r = .43, p = .054 95% CI [−.01, .73] |

| CBCL Social Problems |

r = −.68, p = .002 95% CI [−.87, −.31] |

r = −.42, p = .081 95% CI [−.74, .06] |

r = .24, p = .299 95% CI [−.22, .62] |

r = −.22, p = .350 95% CI [−.59, .24] |

|

| ||||

| NT group | ||||

| Vineland-2 Socialization |

r = .12, p = .48 95% CI [−.22, .43] |

r = .06, p = .75 95% CI [−.29, .39] |

r = .09, p = .603 95% CI [−.25, .41] |

r = .15, p = .402 95% CI [−.20, .46] |

| CBCL Social Problems |

r = −.12, p = .490 95% CI [−.43, .22] |

r = −.06, p = .722 95% CI [−.40, .29] |

r = −.04, p = .804 95% CI [−.37, .29] |

r = .05, p = .782 95% CI [−.29, .38] |

Note:

standard scores with mean of 100.

T-scores with mean of 50. Vineland-2, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd Edition (Sparrow et al., 2005); CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

For the full sample, social motivation was positively correlated with social skills as assessed through caregiver report on the Vineland-2 Socialization scale. This association was observed across youth self-report with peers, r = .47, p < .001, and with adults, r = .34, p = .015, as well as by caregiver report with peers, r = .37, p = .006, and with adults, r = .44, p < .011. Thus, greater social motivation was associated with stronger social skills across reporters and social context.

Inversely, social difficulties as assessed with the CBCL Social Problems subscale were negatively correlated with youth self-reported social motivation across peers, r = −.55, p < .001, and adults, r = −.35, p = .011. Across contexts, stronger social motivation corresponded to fewer social problems. For caregiver-reported motivation, motivation with adults was negatively correlated with social difficulties, r = −.31, p = .02, whereas motivation with peers did not reach significance, r = −.23, p = .09.

Associations between motivation and social outcomes varied across diagnostic groups, however. Within the ASD group, self-reported social motivation was again positively correlated with social skills with peers, r = .49, p = .04, and with adults, r = .54, p = .022. Motivation was again negatively correlated with social difficulties with peers, r = −.68, p = .002, and the association with for motivation with adults did not reach significance, r = −.42, p = .081. With regard to caregiver-reported social motivation, in contrast, none of the associations between caregiver-reported social motivation and youth social functioning reached significance, ps ≥ .06.

Among the NT group, no correlations emerged between social motivation and social outcomes for self-report, ps ≥ .48, nor for caregiver-reported social motivation, ps ≥ .40. For this group, social motivation across indices appeared to be unrelated to youths’ broader social outcomes.

Discussion

Taken together, our findings argue for a more nuanced understanding of social motivation in autistic youth, in which individual differences in motivation and its correlates should be considered in the context of reporter and social context. Most fundamentally, results support the feasibility of autistic youth’s self-report of their social motivation, as self-reported persistence with peers and with adults demonstrated reasonable internal consistency (alpha = .70 and .78, respectively). This aligns with a growing body of research documenting the validity and unique contribution of autistic youth’s firsthand accounts of social and nonsocial internal experiences (e.g., (Elias & White, 2020; Kenworthy et al., 2022)).

Surprisingly, within our NT group, internal consistency values were similarly strong for caregiver-report (alpha ≥ .82) but were lower for self-report (peers: alpha = .54; adults: alpha = .60), in relation to both conventional thresholds and internal consistency values from the DMQ’s standardization sample (peers: alpha = .61; adults: alpha = .70)(Morgan et al., 2009), indicating a more variable response pattern across the items within each index. One interpretation of this finding could suggest that NT youth made subtle distinctions between items contained within each index, perhaps perceiving separable factors within the index, yielding variability across items that might appear similar. For example, NT youth in our sample might have differentiated between items addressing social effort (e.g., “I try hard to make friends with other kids.”) versus those addressing social enjoyment (e.g., “I like to talk with other kids and do it often.”), contributing to variability within the scale and thus lower internal consistency values. Although this possibility is hypothetical, factor analytic methods with a larger sample would be able to further explore this variability, to consider the possibility of separable dimensions within the DMQ scales, and to investigate the psychometric equivalence of social motivation as a construct across autistic and NT groups.

A somewhat similar pattern emerged in terms of consistency across social contexts, where autistic youth reported their persistence with peers and with adults to be highly correlated, but the correlation for NT youth did not reach significance. This indicates that autistic youth in our sample viewed their motivation as relatively stable across social settings and partners, whereas NT youth perceived more variability in their own motivation for interaction with peers versus adults. For both groups, caregivers reported persistence with peers to be largely distinct from motivation with adults. When self-report and caregiver-report were compared directly, degree of correspondence varied across groups and settings. Both ASD and NT groups demonstrated significant correspondence between self- and caregiver-reported motivation in the context of adults; however, motivation with peers was a point of particular discrepancy between autistic youth and caregivers, with no observable association between their reports. These discrepancies between social motivation as experienced by autistic youth versus that perceived by their caregivers reinforce suggestions that internal social drives may be inaccurately inferred by observers on the basis of outward social behaviors (Jaswal & Akhtar, 2018).

Moreover, when compared with real-world social outcomes, we found that autistic youth self-report corresponded to social skills and social difficulties across two different measures, whereas caregiver-report of peer motivation did not. This is especially striking given that both outcome measures (Vineland-2 Socialization, CBCL Social Problems) are caregiver-report assessments, and thus their associations with youth self-reported motivation cannot be attributed to shared method variance. Instead, we conclude that youth and caregivers have overlapping but distinct information to contribute with regard to social motivation, and that children and adolescents with autism can provide an under-appreciated perspective that carries unique value for understanding their social experiences.

Limitations

The primary limitation of the current study is the restricted sample size in relation to the study aims and statistical approach. and replication of these aims within larger samples will be important. Looking ahead, future work should include exploration of social motivation among a more diverse participant group with respect to intellectual ability and verbal fluency. Ensuring that such studies are both representative of the full autism spectrum and appropriately powered to illuminate differences along that heterogeneous spectrum will be essential. Stronger representation of autistic females will be critical as well. Social experiences of autistic females, particularly as described through self-report, are underrepresented in the ASD literature, likely contributing to incomplete conceptualizations of autism and limiting access to diagnostic and support resources for females (Milner et al., 2019). The size and sex ratio our participant group did not permit exploration of possible sex differences, particularly in the ASD group, but recent neuroimaging work indicates sex-based differences in neural response to social reward (Lawrence et al., 2020), and we cannot assume that findings among autistic males generalize to females. This is a critical step in both research and clinical spheres, and offers the promise of more inclusive and representative conclusions.

Future directions

More broadly, future work in this area should seek to characterize social motivation and outcomes from a variety of perspective and methods. Although well-established tools for autism evaluation and diagnosis provide opportunities to elicit perspectives on social interactions and relationships from autistic individuals (e.g., interview questions during the ADOS-2), routinely incorporating self-report measures such as the Social Motivation Interview (Elias & White, 2020) or Dimensions of Mastery Questionnaire (Morgan et al., 2009) can offer straightforward opportunities to gain insight directly from youth with autism. Complementing self- and caregiver-report, incorporation of teacher-report, peer-report, and observational measures of social motivation, skills, and difficulties may provide rich insights into social experiences with peers, in group settings at school, and with siblings or family members at home. Multi-method studies may also aid in clarifying the relatively low correspondence we observed between some variables; for example, teacher-report of persistence toward peers and adults may be more strongly correlated with social skills and difficulties, as they observe a child’s behavior in a different setting and under different environmental demands than do a child’s caregivers. Regardless, data from the current study support both the feasibility and reliability of self-reported social motivation among autistic youth, but integration with additional sources of data is needed to more fully understand the validity, reliability, and structure of the DMQ and other measures of social motivation.

An essential step toward those goals will be longitudinal research evaluating social motivation at multiple points in time, with goals of understanding variability in social motivation across repeated instances and over the course of development. As we note above, we distinguish motivation from skill, viewing these as distinct but related constructs. However, motivation and skill presumably influence and reinforce one another over time, as stronger social motivation likely promotes social engagement and creates opportunities for skill development, reinforcing motivation when positive interactions occur. Repeated assessments of both social motivation and social skill will be necessary to test developmental models such as this. Efforts to elicit and incorporate youth self-report of social experiences will become increasingly important over the course of development as adolescents engage more independently in social interactions and caregivers have fewer opportunities for direct observation of peer interactions. Among neurotypical youth, adolescence often brings a shift in salience and relative influence from parents to peers (Abrams et al., 2022; Morningstar et al., 2019), as well as changes in neural activation and connectivity related to social reward and social cognition (Morningstar et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2022). Thus, we might anticipate shifts in social motivation itself as well as shifts in the relative abilities of youth and their caregivers to accurately assess that motivation.

Finally, interactions between social motivation and other individual differences warrant study, as social motivation does not develop or act in isolation but rather within a broader developmental context for all youth. Factors such as youth mental health (for example, anxiety and impulsivity (Kerns et al., 2017; Neuhaus et al., 2019), social experiences including bullying or exclusion (Kerns et al., 2017), and family or school ability to scaffold positive social experiences all shape and are shaped by social motivation. By more fully assessing these individual differences and the dynamic associations between them over time, we can inform developmental models, understand broader outcomes for autistic and NT youth, and individualize supports to promote positive outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Autism Speaks (Neuhaus), NIMH R01MH101221 (PI: Eichler), and NIMH U01MH119705-02S1 (PI: Martin; Site PI: Neuhaus).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the outcome of this project. Bernier is currently at Apple.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abrams DA, Lynch CJ, Cheng KM, Phillips J, Supekar K, Ryali S, … Menon V (2013). Underconnectivity between voice-selective cortex and reward circuitry in children with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(29), 12060–12065. 10.1073/pnas.1302982110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams DA, Mistry PK, Baker AE, Padmanabhan A, & Menon V (2022). A Neurodevelopmental Shift in Reward Circuitry from Mother’s to Nonfamilial Voices in Adolescence. J Neurosci, 42(20), 4164–4173. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2018-21.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge-Waddon L, Vanova M, Munneke J, Puzzo I, & Kumari V (2020). Atypical social reward anticipation as a transdiagnostic characteristic of psychopathology: A meta-analytic review and critical evaluation of current evidence. Clin Psychol Rev, 82, 101942. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & White TL (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319–333. 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, & Schultz RT (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci, 16(4), 231–239. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G (2008). Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Psychopathol, 20(3), 775–803. 10.1017/S0954579408000370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Webb SJ, & McPartland J (2005). Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Dev Neuropsychol, 27(3), 403–424. 10.1207/s15326942dn2703_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Webb SJ, Wijsman E, Schellenberg G, Estes A, Munson J, & Faja S (2005). Neurocognitive and electrophysiological evidence of altered face processing in parents of children with autism: implications for a model of abnormal development of social brain circuitry in autism. Dev Psychopathol, 17(3), 679–697. 10.1017/S0954579405050327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias R, & White SW (2020). Measuring Social Motivation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Development of the Social Motivation Interview. J Autism Dev Disord, 50(3), 798–811. 10.1007/s10803-019-04311-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott CD (2007). Differential Ability Scales, 2nd Edition. The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Harmon-Jones C, & Price TF (2013). What is Approach Motivation? Emotion Review, 5(3), 291–295. 10.1177/1754073913477509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itskovich E, Zyga O, Libove RA, Phillips JM, Garner JP, & Parker KJ (2021). Complex Interplay Between Cognitive Ability and Social Motivation in Predicting Social Skill: A Unique Role for Social Motivation in Children With Autism. Autism Res, 14(1), 86–92. 10.1002/aur.2409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK, & Akhtar N (2018). Being versus appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behav Brain Sci, 42, e82. 10.1017/S0140525X18001826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith JM, Jamieson JP, & Bennetto L (2019). The Importance of Adolescent Self-Report in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Integration of Questionnaire and Autonomic Measures. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 47(4), 741–754. 10.1007/s10802-018-0455-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy L, Verbalis A, Bascom J, daVanport S, Strang JF, Pugliese C, … Wallace GL (2022). Adding the missing voice: How self-report of autistic youth self-report on an executive functioning rating scale compares to parent report and that of youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or neurotypical development. Autism, 26(2), 422–433. 10.1177/13623613211029117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Renno P, Kendall PC, Wood JJ, & Storch EA (2017). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Autism Addendum: Reliability and Validity in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 46(1), 88–100. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1233501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Chevallier C, Troiani V, & Schultz RT (2012). Social ‘wanting’ dysfunction in autism: neurobiological underpinnings and treatment implications. J Neurodev Disord, 4(1), 10. 10.1186/1866-1955-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence KE, Hernandez LM, Eilbott J, Jack A, Aylward E, Gaab N, … Consortium, G. (2020). Neural responsivity to social rewards in autistic female youth. Transl Psychiatry, 10(1), 178. 10.1038/s41398-020-0824-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, & Bishop S (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part I): Modules 1–4. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, & Le Couteur A (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview - Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 659–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrus N, Botteron KN, Hawks Z, Pruett JR, Elison JT, Jackson JJ, … Constantino JN (2022). Social motivation in infancy is associated with familial recurrence of ASD. Dev Psychopathol, 1–11. 10.1017/S0954579422001006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, & Happé F (2019). A Qualitative Exploration of the Female Experience of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord, 49(6), 2389–2402. 10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan G, Busch-Rossnagel N, Barrett K, & Wang J (2009). The Dimensions of Mastery Questionnaire (DMQ): A manual about its development, psychometrics and use. Colorado State University. [Google Scholar]

- Morningstar M, Grannis C, Mattson WI, & Nelson EE (2019). Associations Between Adolescents’ Social Re-orientation Toward Peers Over Caregivers and Neural Response to Teenage Faces. Front Behav Neurosci, 13, 108. 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P (1995). Joint attention and social-emotional approach behavior in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology, 7(1), 63–82. 10.1017/S0954579400006349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus E, Bernier RA, & Webb SJ (2020). Social Motivation Across Multiple Measures: Caregiver-Report of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 10.1002/aur.2386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus E, Webb SJ, & Bernier RA (2019). Linking social motivation with social skill: The role of emotion dysregulation in autism spectrum disorder. Dev Psychopathol, 31(3), 931–943. 10.1017/S0954579419000361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J (2004). Affective Neuroscience : The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JM, Uljarević M, Schuck RK, Schapp S, Solomon EM, Salzman E, … Hardan AY (2019). Development of the Stanford Social Dimensions Scale: initial validation in autism spectrum disorder and in neurotypicals. Mol Autism, 10, 48. 10.1186/s13229-019-0298-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriber RA, Robins RW, & Solomon M (2014). Personality and self-insight in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Pers Soc Psychol, 106(1), 112–130. 10.1037/a0034950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, & Balla D (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd ed. Pearson Assessments. [Google Scholar]

- Su PL, Rogers SJ, Estes A, & Yoder P (2021). The role of early social motivation in explaining variability in functional language in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 25(1), 244–257. 10.1177/1362361320953260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber KS (2018). The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48, 1273–1296. 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Alkire D, Moraczewski D, & Redcay E (2022). Developmental differences in brain functional connectivity during social interaction in middle childhood. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 54, 101079. 10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.