Abstract

BACKGROUND

Oncostatin M (OSM) is a pleiotropic cytokine which is implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

AIM

To evaluate the prognostic role of OSM in IBD patients.

METHODS

Literature search was conducted in electronic databases (Google Scholar, Embase, PubMed, Science Direct, Springer, and Wiley). Studies were selected if they reported prognostic information about OSM in IBD patients. Outcome data were synthesized, and meta-analyses were performed to estimate standardized mean differences (SMDs) in OSM levels between treatment responders and non-responders and to seek overall correlations of OSM with other inflammatory biomarkers.

RESULTS

Sixteen studies (818 Crohn’s disease and 686 ulcerative colitis patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-based therapies) were included. OSM levels were associated with IBD severity. A meta-analysis found significantly higher OSM levels in non-responders than in responders to therapy [SMD 0.80 (0.33, 1.27); P = 0.001], in non-remitters than in remitters [SMD 0.75 (95%CI: 0.35 to 1.16); P < 0.0001] and in patients with no mucosal healing than in those with mucosal healing [SMD 0.63 (0.30, 0.95); P < 0.0001]. Area under receiver operator curve values showed considerable variability between studies but in general higher OSM levels were associated with poor prognosis. OSM had significant correlations with Simple Endoscopic Score of Crohn’s disease [r = 0.47 (95%CI: 0.25 to 0.64); P < 0.0001], Mayo Endoscopic Score [r = 0.35 (95%CI: 0.28 to 0.41); P < 0.0001], fecal calprotectin [r = 0.19 (95%CI: 0.08 to 0.3); P = 0.001], C-reactive protein [r = 0.25 (95%CI: 0.11 to 0.39); P < 0.0001], and platelet count [r = 0.28 (95%CI: 0.17 to 0.39); P < 0.0001].

CONCLUSION

OSM is a potential candidate for determining the severity of disease and predicting the outcomes of anti-tumor necrosis factor-based therapies in IBD patients.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Oncostatin M, Prognosis

Core Tip: Higher Oncostatin M (OSM) expression/levels are found to be associated with worse disease outcomes which shows that OSM can be used as a s surrogate marker of poor prognosis in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor based therapies. Thus, OSM appears to be an attractive biomarker for patient selection and clinical decision-making. However, owing to the presence of heterogeneity in included studies, this evidence should be refined in future studies.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a disease of the gastrointestinal tract with two main types: Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Crohn's disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, whereas ulcerative colitis mainly affects the colon. IBD may arise at any age but usually onsets at early adulthood[1]. Primary surgery is required for approximately 32%, 55%, 70%, and 82% of Crohn’s disease patients after 5, 10, 15, and 20 years of diagnosis, respectively[2]. It is speculated that an altered immune response to gut flora depending on individual's hereditary variability and environmental influences may be involved in the etiology of IBD. Age at onset, location, behavior, perianal disease in Crohn's disease and disease extent in ulcerative colitis are important determinants of disease condition[3].

There is an increasing trend in the prevalence of IBD. In the United States, the prevalence of IBD has increased from 0.8% (1.8 million) in 1999 to 1.3% (3 million) in 2015[4]. Globally, the prevalence of IBD is rising in newly industrialized countries[5]. Concomitantly, the prevalence rates of pediatric-onset IBD are also increasing even in regions where this disease was not previously reported[6]. IBD is clinically difficult-to-treat disease that affects younger individuals and leads to long-term morbidity. Resistance to therapeutic agents is a hallmark of its management that necessitates personalized medicine research and development. Use of alternative drugs is frequent, but prediction of disease course and response to a particular therapy can profoundly benefit to patients.

IBD is a lifelong incurable disease that alternates with remission and relapse. Management may require 5-aminosalicylates, thiopurines, steroids, and biologics such as antibodies against tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), vedolizumab, ustekinumab etc.[7]. TNFα is involved in IBD onset and progression. Anti-TNFα antibody-based drugs including infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab are the mainstay in the treatment of IBD[8]. However, about 40% of patients do not respond to anti-TNF therapies, and among those who initially respond, several develop resistance to treatment. This necessitates IBD research to focus not only on the development of newer drugs, but also to identify biomarkers that can predict response to a therapy in advance[9].

Oncostatin M (OSM) is a proinflammatory cytokine belonging to the interleukin-6 family. OSM is produced mostly in hematopoietic tissues including T-lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells[10]. It is a pleiotropic factor that participates in several organismic processes including hematopoiesis, differentiation, regeneration, and inflammation. On the other hand, several pathological processes including arthritis, ossification, dermatitis, fibrosis, gingivitis, and carcinogenesis are found to have OSM mediation[11]. In colorectal cancer, higher OSM levels are associated with advanced disease and metastasis[12]. One of the major pathological processes in which the involvement of OSM has been found critical is the inflammation of various parts including the joints, skin, lungs, and intestine[10].

The role of OSM in the pathogenesis of IBD was first described in a discovery of single nucleotide polymorphism in OSM receptors[13]. OSM mediates its effects by binding to a glycoprotein called gp130 and this complex then activates the OSM receptor for signaling[14]. OSM is highly expressed in inflamed mucosa of IBD patients in comparison with normal individuals. Elevated OSM levels are also found in serum of IBD patients. Moreover, higher OSM levels are observed in first-degree relatives of multiple-affected families in comparison with normal families[15]. Several studies have evaluated the prognostic role of OSM in IBD patients. However, there are variabilities in the degree of associations between OSM and disease or interventional outcomes. This necessitates a systematic review of this area. The aim of the present study was to identify studies that evaluated the prognostic role of OSM in IBD patients in order to synthesize the reported outcomes and to perform meta-analyses of statistical indices for seeking up-to-date evidence of the prognostic role of OSM in IBD prognosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they: (1) Evaluated IBD patients receiving a therapy who were subjected to OSM measurements in serum or tissue; (2) evaluated prognostic role of OSM in predicting disease outcomes and reported statistical indices of this relationship; and (3) reported correlations between baseline OSM and other important indicators of disease. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Studies involving the prognostic role of OSM in combination with other biomarkers; (2) molecular studies not providing any prognostic outcome; (3) molecular studies evaluating a possible role of OSM in IBD therapeutics; (4) preclinical studies; and (5) reviews and congress abstracts.

Literature search

The literature search was conducted in electronic databases (Google Scholar, Ebsco, PubMed, Science Direct, Springer, and Wiley) using the most relevant keywords. Primary search strategy was: Inflammatory bowel disease OR Crohn’s disease OR ulcerative colitis AND oncostatin M AND prognosis OR prognostic OR predictor. The literature search encompassed original research articles published in English language from the date of inception of the database till September 2023.

Data analysis

The quality assessment of the included studies was performed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the Quality Assessment of Observational Studies. Demographic information, disease pathological indices, previous treatments, study design and conduct features, and study outcome data including OSM levels at baseline, OSM levels in association with response, remission, and mucosal healing rates, statistical data depicting the relationship between baseline OSM levels and outcomes of disease, and correlation coefficients between OSM and other variables of IBD etiology were extracted from research articles of the included studies and were organized in datasheets. Important characteristics of the included studies were tabulated, and outcome data were synthesized for use in analyses.

Area under the receiver-operator curve (AUC) values depicting the relationship between OSM and disease indicators including response rate, remission rate, and mucosal healing rate reported by individual studies were tabulated. A meta-analysis of standardized mean differences (SMDs) in OSM levels between responders and non-responders, remitters and non-remitters, and in patients with mucosal healing and no mucosal healing was performed. Correlation coefficients between OSM and other variables of disease etiology reported by the individual studies were first converted to z-scores and were pooled under random-effects model by deriving variance from respective sample sizes. Overall estimates were back transformed into correlation coefficients.

RESULTS

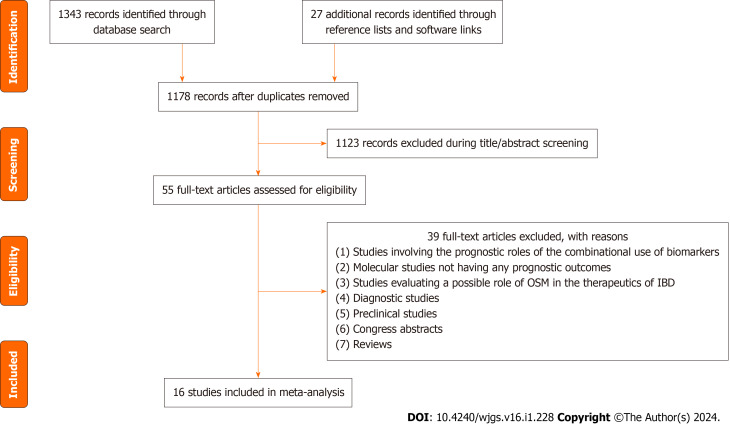

Sixteen studies[16-31] were included in this review (Figure 1). In these studies, 1353 IBD (818 Crohn’s disease and 686 ulcerative colitis) patients were evaluated. Important characteristics of the included studies are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The quality of these studies was generally good. The lack of unexposed cohort was the main constraint which was observed for 7 studies. One of the included studies was double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled with high quality. An assessment of the quality of other included studies with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale is presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of study screening and selection process. OSM: Oncostatin M; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

OSM levels in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis were generally similar. In Cao et al[18], fecal OSM levels (mean ± SD; pg/mL) were 7 ± 3 in Crohn’s disease and 11 ± 4 in ulcerative colitis patients. In Cao et al[19], serum OSM levels (mean ± SD; pg/mL) were 119.4 (range: 34.8 - 240.6) in Crohn’s disease and 122.1 (range: 58.7 - 294.9) in ulcerative colitis patients. In Verstockt et al[28], OSM expression levels (NPX; OLINK proximity extension technology values) were 6.4 (IQR: 5.5, 7) in Crohn’s disease and 6.5 (IQR: 4.35, 4.9) in UC patients. In the study of West et al[29], log 2 OSM mRNA expression levels relative to control were 5 (IQR: 4, 8) in Crohn’s disease and 5.2 (IQR: 4.5, 7) in ulcerative colitis patients.

However, OSM levels were associated with disease severity. In Cao et al[18], fecal OSM levels (mean ± SD; pg/mL) were 7 ± 2 in mild, 8 ± 5 in moderate, and 14 ± 4 in severe IBD cases whereas in Cao et al[19], serum OSM levels (mean ± SD; pg/mL) were 10 ± 27 in mild, 220 ± 240 in moderate, and 340 ± 150 in severe IBD cases. Mohamed et al[24] reported serum OSM levels to be 109.5 ± 25.5 in mild, 116.2 ± 27.6 in moderate, and 144.8 ± 33.5 in severe IBD cases. In West et al[29], OSM expression relative to control was 2 (IQR: 0, 2.2) in mild, 5 (IQR: 4, 5.2) in moderate, and 4 (IQR: 3, 4.5) in severe IBD cases.

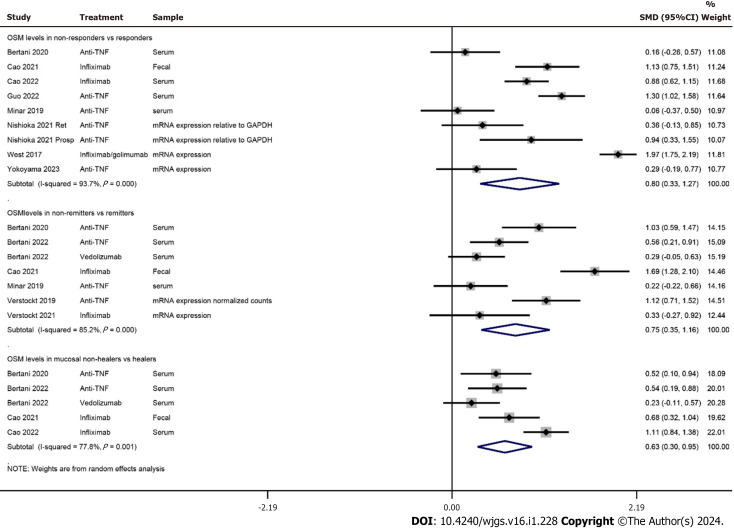

A meta-analysis found significantly higher OSM levels in non-responders than in responders to therapy [SMD 0.80 (95%CI: 0.33 to 1.27); P = 0.001]. OSM levels were also significantly higher in non-remitters in comparison with remitters [SMD 0.75 (95%CI: 0.35 to 1.16); P < 0.0001] and in patients with no mucosal healing than in those with mucosal healing [SMD 0.63 (95%CI: 0.30 to 0.95); P < 0.0001; Figure 2]. OSM levels and tissue expression data of all included studies are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 2.

A forest graph showing the outcomes of a meta-analysis of standardized mean differences between responders and non-responders, remitters and non-remitters, and mucosal healers and non-healers of anti-tumor necrosis factor-based therapies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. OSM: Oncostatin M; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; SMD: Standardized mean difference.

A synthesis of AUC values of treatment outcomes revealed that anti-TNF treatment had poor outcomes in patients with higher OSM levels in most studies (Tables 1 and 2). AUC values of OSM predicting the response of anti-TNF treatment in IBD patients ranged from 0.56 [95%CI: 0.31 to 0.82] to 0.91 [95%CI: 0.81 to 1.0] whereas the AUC values of OSM in distinguishing between responders and non-responders (including remission and mucosal healing) to anti-TNF therapy ranged from 0.52 to 0.9. Two studies did not report numeric data. Among these, O’Connell et al[26], who studied 21 patients with ulcerative colitis, did not find an association of pretreatment colonic OSM expression with the outcomes of infliximab therapy, and Mateos et al[21], who studied 22 patients with Crohn's disease, reported that OSM levels measured before induction therapy predicted response to infliximab treatment.

Table 1.

Area under receiver operator curve values for the prediction of treatment outcomes by the Oncostatin M

|

Ref.

|

Prognostic association

|

OSM cutoff

|

AUC [95%CI]

|

Sensitivity [95%CI]

|

Specificity [95%CI]

|

| Bertani et al[16], 2020 | Prediction of no mucosal healing after anti-TNFα therapy at week 54 by baseline serum OSM | 14 | 0.91 [0.81, 1] | 96% [82, 100] | 89% [67, 97] |

| Bertani et al[16], 2020 | Prediction of no mucosal healing after anti-TNFα therapy at week 54 by serum OSM at week 14 | 0.83 [0.7, 0.95] | |||

| Bertani et al[17], 2022 | Prediction of no mucosal healing after anti-TNFα therapy at week 54 by baseline serum OSM | 14 | 0.91 [0.84, 0.99] | 91% [78, 97] | 90% [75, 97] |

| Bertani et al[17], 2022 | Prediction of non-response to vedolizumab therapy at week 54 by baseline serum OSM | 0.56 [0.42, 0.7] | |||

| Cao et al[18], 2021 | Prediction of non-response to infliximab at week 54 by baseline fecal OSM | 0.638 | |||

| Cao et al[18], 2021 | Prediction of non-response to infliximab at week 28 by baseline fecal OSM | 132 | 0.763 | 66.7% | 92.5% |

| Ezirike Ladipo et al[21], 2021 | Prediction of response to anti-TNF therapy by OSM expression in biopsies | OSM expression in pre-treatment biopsies did not predict response to anti-TNF in a pediatric population | |||

| Mateos et al[22], 2021 | Prediction of response to infliximab in a calprotectin log drop measurement model | OSM was found to have predicting ability to infliximab response | |||

| Minar et al[23], 2019 | Prediction of no remission after anti-TNFα therapy at week 12 by baseline serum OSM | 144 | 0.71 [0.52, 0.89] | 71% | 78% |

| Minar et al[23], 2019 | Prediction of non-response to anti-TNFα therapy at week 12 by baseline serum OSM | 117 | 0.69 [0.5, 0.89] | ||

| Mohamed et al[24], 2022 | Prediction of no remission after anti-TNFα therapy by baseline serum OSM | 119 | 0.56 [0.31, 0.82] | 66.7% | 54.2% |

| O’connell et al[26], 2022 | Prediction of response to infliximab by colonic OSM expression | No association of pretreatment colonic OSM expression with outcomes of Infliximab therapy | |||

| Zhou et al[31], 2019 | Prediction of the response to PF-00547659 (anti-human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1) therapy | Baseline OSM expression/levels were unable to predict response | |||

AUC: Area under receiver operator curve; OSM: Oncostatin M; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

Table 2.

Area under receiver operator curve values for identifying/distinguishing treatment response by OSM

|

Ref.

|

Prognostic association

|

OSM cutoff

|

AUC [95%CI]

|

Sensitivity [95%CI]

|

Specificity [95%CI]

|

| Cao et al[18], 2021 | Identification of mucosal healing after infliximab therapy by fecal OSM | 0.702 | |||

| Cao et al[18], 2021 | Identification of clinical remission after infliximab therapy by fecal OSM | 0.674 | |||

| Cao et al[19], 2022 | Identification of mucosal healing after infliximab therapy by serum OSM | 64.1 | 0.84 [0.75, 0.91] | 81.8% | 80.8% |

| Cao et al[19], 2022 | Identification of clinical response to infliximab therapy by serum OSM | 83 | 0.90 [0.8, 0.96] | 86.4% | 87% |

| Cao et al[19], 2022 | Identification of clinical remission after infliximab therapy by serum OSM | 98.9 | 0.9 [0.83, 0.95] | 82.1% | 86.4% |

| Guo et al[20], 2022 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters after 1 year of anti-TNFα therapy in CD patients by serum OSM | 169 | 0.88 [0.79, 0.96] | 76% [58, 88] | 91% [80, 96] |

| Guo et al[20], 2022 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters after 1 year of anti-TNFα therapy in UC patients by serum OSM | 234 | 0.94 [0.87, 1] | 80% [55, 93] | 96% [79, 99] |

| Nishioka et al[25], 2021 | Distinction between anti-TNFα resistant and sensitive patients by mucosal OSM mRNA | 0.83 | |||

| Nishioka et al[25], 2021 | Distinction between ustekinumab resistant and sensitive patients by mucosal OSM mRNA | 0.77 | |||

| Verstockt et al[28], 2021 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters 6 months after surgery by serum OSM | 0.80 [0.68, 0.92] | |||

| Verstockt et al[28], 2021 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters after anti-TNFα therapy by serum OSM | 0.52 [0.44, 0.61] | |||

| Verstockt et al[28], 2021 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters after anti-TNFα therapy by colonic OSM | 0.74 [0.54, 0.94] | |||

| Verstockt et al[28], 2021 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters after vedolizumab therapy by serum OSM | 0.51 [0.43, 0.59] | |||

| Verstockt et al[28], 2021 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters after vedolizumab therapy by colonic OSM | 0.69 [0.53, 0.84] | |||

| West et al[29], 2017 | Distinction between responders and non-responders to infliximab by mucosal OSM mRNA | 0.99 | 100 | 91.7 | |

| Yokoyama et al[30], 2023 | Distinction between responders and non-responders to anti-TNFα by mucosal OSM mRNA | 0.94 | |||

| Yokoyama et al[30], 2023 | Distinction between CORT-dependent vs non-dependent remission by mucosal OSM mRNA | 0.79 | |||

| Zhou et al[31], 2019 | Distinction between responders and non-responders to F-00547659 by change in OSM expression in inflamed tissue | 0.88 | |||

| Zhou et al[31], 2019 | Distinction between remitters and non-remitters to F-00547659 by change in OSM expression in inflamed tissue | 0.81 | |||

| Zhou et al[31], 2019 | Distinction between mucosal healing and no mucosal healing by F-00547659 therapy by the change in OSM expression during treatment in inflamed tissue | 0.83 |

AUC: Area under receiver operator curve; OSM: Oncostatin M; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

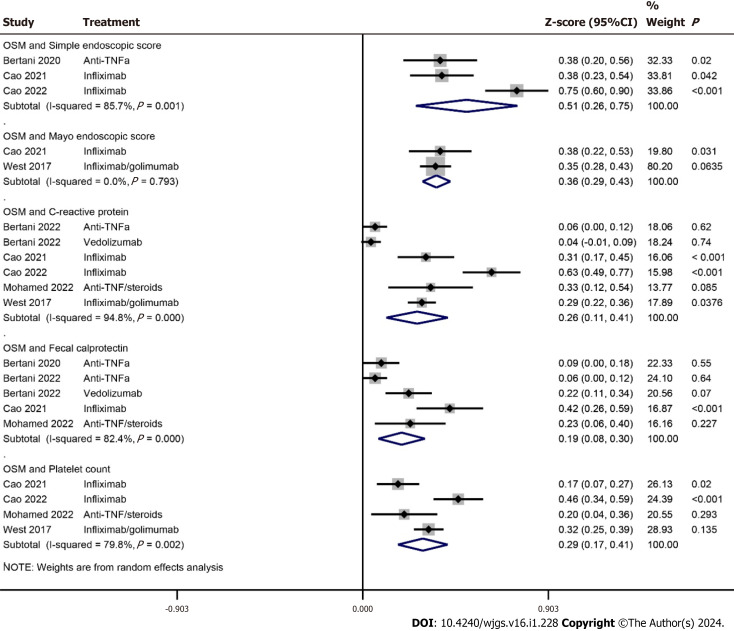

The correlation coefficients between OSM and Simple Endoscopic Score and Mayo Endoscopic Score were 0.47 [95%CI: 0.25 to 0.64] (P < 0.0001) and 0.35 [95%CI: 0.28 to 0.41] (P < 0.0001) respectively. The correlation coefficients between OSM and fecal calprotectin, C-reactive protein, and platelet count were 0.19 [95%CI: 0.08 to 0.3] (P = 0.001), 0.25 [95%CI: 0.11 to 0.39] (P < 0.0001), and 0.28 [95%CI: 0.17 to 0.39] (P < 0.0001) respectively (Figure 3). The correlation coefficients between OSM and other inflammatory/hematological markers observed in the included studies are given in Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 3.

A forest graph showing the outcomes of a meta-analysis of correlation coefficients between baseline Oncostatin M and other baseline inflammatory biomarkers/disease indicators. OSM: Oncostatin M; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

DISCUSSION

OSM has emerged as an important biomarker for determining disease condition and response to anti-TNF therapies in IBD patients. Higher OSM levels are found to be associated with disease severity and therapeutic non-response. AUC values reported by the individual studies showed that higher OSM levels predicted poor response and could be used to distinguish responders from non-responders of anti-TNF therapy. OSM had significant correlations with Simple Endoscopic Score, Mayo Endoscopic Score, fecal calprotectin, C-reactive protein, and platelet count.

Where there is always a need to search for newer drugs, there is also a need to identify markers which can predict the effectiveness of a therapy in advance. Although C-reactive protein is a commonly used marker for predicting response to a therapy, it is non-specific to IBD[16,32,33]. Fecal calprotectin is more important for IBD outcome prediction. Higher FC levels are found to be associated with no response to therapy[34-36]. Cao et al[18] found higher AUC value for fecal calprotectin (0.834) than fecal OSM (0.763) in predicting response to anti-TNF therapy. In the meta-analysis of correlation coefficients, we have found a significant correlation between OSM and fecal calprotectin in IBD patients.

It has been observed that OSM predicts therapeutic response better to anti-TNF than to other pharmacological treatments. Bertani et al[17] found OSM to be a useful biomarker for predicting response to anti-TNF therapy (AUC 0.91) but not to vedolizumab (AUC 0.56). Verstockt et al[28] also found low AUC values for distinguishing remitters from non-remitters after vedolizumab therapy both by serum OSM (0.51) and colonic OSM (0.685). Nishioka et al[25] found a relatively higher AUC value for mucosal OSM expression in distinguishing resistant from sensitive patients to anti-TNF therapy (0.83) compared to ustekinumab (0.77).

Minar et al[23] found no association between clinical remission and OSM 3 months after anti-TNF therapy but observed a significant association between OSM and clinical response one year after treatment. They suggested that duration of response evaluation may affect the outcomes. However, Cao et al[18] found higher AUC value (0.76) of serum OSM to predict nonresponse at week 28 in comparison with AUC value observed at week 54 of treatment (0.64). Verstockt et al[28] found no significant association between serum OSM and endoscopic remission after 6 months of anti-TNF therapy. On the other hand, Bertani et al[16,17] and Guo et al[20] found significant associations between serum OSM and response to anti-TNF therapy after one year of treatment.

In a transcriptomic gene expression study, Zhou et al[31] found that on week 12 of PF-00547659 (anti-human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 antibody) treatment the OSM expression and serum levels decreased profoundly from baseline in patients with ulcerative colitis who achieved response, remission, or mucosal healing. Whereas the change in serum OSM levels was 1.4-fold among responders, the change in OSM expression among responders and those achieving mucosal healing was 6.1-fold and 7.4-fold respectively[31]. Verstockt et al[28] who found mucosal OSM to predict response to anti-TNF therapy, did not find serum OSM to do the same. In the study of Zhou et al[31], baseline OSM expression did not predict therapeutic outcomes. Whether this difference can be attributed to the mechanism of action of drug (PF-00547659 vs anti-TNF based therapies) remains to be evaluated. OSM acts synergistically with TNF to promote inflammation in stromal cells and this phenomenon may not be exhibited by the other modulators such as human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1.

Verstockt et al[28] performed immunohistochemical staining on resected tissues and found OSM expression in the macrophages lying in superficial lamina propria as well as in the epithelial granulomas and multinucleated giant cells. In this study, macrophagic OSM expression had a strong correlation with mucosal OSM. OSM expression is found consistently higher in inflamed parts of intestine where it promotes inflammation in gut stromal cells in response to microbial challenges[22]. O'Connell et al[26] who studied 21 acute severe ulcerative colitis patients observed a greater degree of immunostaining in the mucosal epithelial cells rather than stromal cells which provides impetus for studying OSM immunostaining in different IBD phenotypes. This study did not find an association between OSM expression levels and response to infliximab used as rescue therapy.

We found that OSM levels were not much different between patients with Crohn’s disease and those with ulcerative colitis[19,28,29]. However, Cao et al[18] found fecal OSM levels to be significantly higher in patients with ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. On the other hand, OSM levels were associated with disease severity as there was an increasing trend of OSM levels from mild, to moderate and severe disease[18,19,24,29]. OSM levels are also found higher in IBD patients in comparison with healthy controls[18,21,24,28]. These outcomes are similar to a study that characterized serum inflammatory protein profile and found a differential regulation of OSM between patients with ulcerative colitis and healthy controls but not between patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis[37].

Although, most of the studies included herein identified OSM as a potential biomarker of IBD severity and predictor of response to anti-TNF therapies, some studies could not find so. Ezirike Ladipo et al[21] who studied 98 children with IBD reported that OSM or OSM receptor expression did not predict response to anti-TNF treatment, although OSM was associated with disease severity. Mohamed et al[24] reported that OSM did not have an appreciable ability to predict the response to therapy. O'Connell et al[26] also reported that colonic OSM expression was unable to predict infliximab treatment outcomes. Verstockt et al[28] reported that serum OSM levels had an AUC value of 0.52 in distinguishing between remitters and non-remitters after anti-TNF therapy. In the study of Zhou et al[31], baseline OSM levels were unable to predict response to PF-00547659.

West et al[29] reported that among the 64 cytokines evaluated, the OSM and its receptor were most intensely overexpressed in the inflamed mucosa of IBD patients. They suggested that OSM may also be involved in developing resistance to anti-TNF therapies. According to West et al[29], haematopoietically derived OSM appears to mediate intestinal pathology by promoting inflammatory behavior in gut-resident stromal cells which is a novel system of leukocyte-stromal cell cross talk that may have relevance in multiple mucosal tissues. Because of its stabilizing interactions with extracellular matrix components, OSM may play a critical role in the etiology of disease. Thus, OSM may act as an inflammatory amplifier and driver of disease chronicity by promoting chemokines, cytokines, and adhesion factor production from intestinal stromal cells.

There are some limitations of this review. There were inconsistencies in the outcome data of individual studies in measuring OSM levels/expression and their numerical presentations due to which not all data could be meta-analyzed. Moreover, in some studies, numerical outcome data were not accompanied by the variance. To account for such constraints, we either performed a meta-analysis of SMDs or tabulated the outcomes systematically. This constraint also precluded us from having a generalized estimate of OSM levels/concentrations. Moreover, for data where meta-analyses were possible, we observed higher statistical heterogeneity. Methodological differences of individual studies could have also played a role in the variabilities observed in this review.

CONCLUSION

Most of the studies attempting to seek relationship between OSM and disease or treatment outcomes have found that higher OSM expression/levels to be associated with worse disease outcomes which shows that OSM can be used as a s surrogate marker of poor prognosis in IBD patients treated with anti-TNF treatments. This makes OSM an attractive biomarker for patient selection and clinical decision-making. However, some studies could not recognize such associations and others found non-significant correlations between OSM and other indicators such as fecal calprotectin, C-reactive protein, and platelets. Therefore, more studies are required to validate present day evidence and to explore the behavior of OSM for IBD treatments other than anti-TNF drugs.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Oncostatin M (OSM) is a pleiotropic factor that participates in several physiological processes such as hematopoiesis, differentiation, regeneration, and inflammation, and pathological processes such as arthritis, ossification, dermatitis, fibrosis, gingivitis, and carcinogenesis.

Research motivation

Higher OSM levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) provided impetus for reviewing the outcomes of studies that evaluated the prognostic role of OSM in IBD patients.

Research objectives

The objective of this research was to systematically review relevant studies and perform meta-analyses of statistical indices for seeking current evidence about the role of OSM in IBD prognosis.

Research methods

After a literature search in electronic databases, studies were identified for synthesis. Meta-analyses were performed to estimate standardized mean differences in OSM levels between responders and non-responders, and to pool correlations of OSM with other inflammatory biomarkers.

Research results

OSM levels were associated with disease severity and were significantly higher in non-responders, in non-remitters, and in patients with no mucosal healing after anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy. Area under receiver operator curve values showed considerable variability between studies but in general higher OSM levels were associated with poor prognosis. OSM had significant correlations with Simple Endoscopic Score of Crohn’s disease, Mayo Endoscopic Score, fecal calprotectin, C-reactive protein, and platelet count.

Research conclusions

OSM can potentially determine IBD severity and can predict the outcomes of anti-tumor necrosis factor-based therapies.

Research perspectives

Future studies may refine the outcomes reported herein. It could also be interesting to explore the role of OSM in achieving response to non-anti-TNF therapies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 14, 2023

First decision: December 8, 2023

Article in press: December 29, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Matsui T, Japan S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

Contributor Information

Yue Yang, Department of Gastroenterology III, Heilongjiang Provincial Hospital, Harbin 150036, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Kan-Zuo Fu, Department of Nursing, The Second Hospital of Harbin, Harbin 150056, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Gu Pan, Department of Gastroenterology III, Heilongjiang Provincial Hospital, Harbin 150036, Heilongjiang Province, China. pangu6196@126.com.

References

- 1.Wehkamp J, Götz M, Herrlinger K, Steurer W, Stange EF. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:72–82. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato Y, Matsui T, Yano Y, Tsurumi K, Okado Y, Matsushima Y, Koga A, Takahashi H, Ninomiya K, Ono Y, Takatsu N, Beppu T, Nagahama T, Hisabe T, Takaki Y, Hirai F, Yao K, Higashi D, Futami K, Washio M. Long-term course of Crohn's disease in Japan: Incidence of complications, cumulative rate of initial surgery, and risk factors at diagnosis for initial surgery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1713–1719. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL ECCO -EpiCom. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:322–337. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, Wheaton AG, Croft JB. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1166–1169. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6542a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuenzig ME, Fung SG, Marderfeld L, Mak JWY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC, Wilson DC, Cameron F, Henderson P, Kotze PG, Bhatti J, Fang V, Gerber S, Guay E, Kotteduwa Jayawarden S, Kadota L, Maldonado D F, Osei JA, Sandarage R, Stanton A, Wan M InsightScope Pediatric IBD Epidemiology Group, Benchimol EI. Twenty-first Century Trends in the Global Epidemiology of Pediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1147–1159.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang LF, Chen PR, He SK, Duan SH, Zhang Y. Predictors and optimal management of tumor necrosis factor antagonist nonresponse in inflammatory bowel disease: A literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:4481–4498. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i29.4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra I, Bermejo F. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in poor responders to infliximab. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014;7:359–367. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S45297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas H. IBD: Oncostatin M promotes inflammation in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:261. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West NR, Owens BMJ, Hegazy AN. The oncostatin M-stromal cell axis in health and disease. Scand J Immunol. 2018;88:e12694. doi: 10.1111/sji.12694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf CL, Pruett C, Lighter D, Jorcyk CL. The clinical relevance of OSM in inflammatory diseases: a comprehensive review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1239732. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1239732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurluler E, Tumay LV, Guner OS, Kucukmetin NT, Hizli B, Zorluoglu A. Oncostatin-M as a novel biomarker in colon cancer patients and its association with clinicopathologic variables. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:2042–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirkov MU, Verstockt B, Cleynen I. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease: beyond NOD2. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:224–234. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adrian-Segarra JM, Schindler N, Gajawada P, Lörchner H, Braun T, Pöling J. The AB loop and D-helix in binding site III of human Oncostatin M (OSM) are required for OSM receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:7017–7029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.001920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verstockt S, Verstockt B, Vermeire S. Oncostatin M as a new diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2019;23:943–954. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2019.1677608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertani L, Fornai M, Fornili M, Antonioli L, Benvenuti L, Tapete G, Baiano Svizzero G, Ceccarelli L, Mumolo MG, Baglietto L, de Bortoli N, Bellini M, Marchi S, Costa F, Blandizzi C. Serum oncostatin M at baseline predicts mucosal healing in Crohn's disease patients treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:284–291. doi: 10.1111/apt.15870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertani L, Barberio B, Fornili M, Antonioli L, Zanzi F, Casadei C, Benvenuti L, Facchin S, D'Antongiovanni V, Lorenzon G, Ceccarelli L, Baglietto L, de Bortoli N, Bellini M, Costa F, Savarino EV, Fornai M. Serum oncostatin M predicts mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases treated with anti-TNF, but not vedolizumab. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:1367–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao Y, Dai Y, Zhang L, Wang D, Hu W, Yu Q, Wang X, Yu P, Liu W, Ping Y, Sun T, Sang Y, Liu Z, Chen Y, Tao Z. Combined Use of Fecal Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Oncostatin M and Calprotectin. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:6409–6419. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S342846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Dai Y, Zhang L, Wang D, Yu Q, Hu W, Wang X, Yu P, Ping Y, Sun T, Sang Y, Liu Z, Chen Y, Tao Z. Serum oncostatin M is a potential biomarker of disease activity and infliximab response in inflammatory bowel disease measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay. Clin Biochem. 2022;100:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2021.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo A, Ross C, Chande N, Gregor J, Ponich T, Khanna R, Sey M, Beaton M, Yan B, Kim RB, Wilson A. High oncostatin M predicts lack of clinical remission for patients with inflammatory bowel disease on tumor necrosis factor α antagonists. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1185. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05208-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezirike Ladipo J, He Z, Chikwava K, Robbins K, Beri J, Molle-Rios Z. Oncostatin-M Does Not Predict Treatment Response in Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Pediatric Cohort. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;73:352–357. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mateos B, Sáez-González E, Moret I, Hervás D, Iborra M, Cerrillo E, Tortosa L, Nos P, Beltrán B. Plasma Oncostatin M, TNF-α, IL-7, and IL-13 Network Predicts Crohn's Disease Response to Infliximab, as Assessed by Calprotectin Log Drop. Dig Dis. 2021;39:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000508069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minar P, Lehn C, Tsai YT, Jackson K, Rosen MJ, Denson LA. Elevated Pretreatment Plasma Oncostatin M Is Associated With Poor Biochemical Response to Infliximab. Crohns Colitis 360. 2019;1:otz026. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otz026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed GA, Mohamed HAE-L, Abo Halima AS, Elshaarawy MEA, Khedr A. Changes in serum oncostatin M levels during treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2022;89:7217–7225. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishioka K, Ogino H, Chinen T, Ihara E, Tanaka Y, Nakamura K, Ogawa Y. Mucosal IL23A expression predicts the response to Ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:976–987. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01819-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connell J, Doherty J, Buckley A, Cormican D, Dunne C, Hartery K, Larkin J, MacCarthy F, McCormick P, McKiernan S, Mehigan B, Muldoon C, Ryan C, O'Sullivan J, Kevans D. Colonic oncostatin M expression evaluated by immunohistochemistry and infliximab therapy outcome in corticosteroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2022;20:381–385. doi: 10.5217/ir.2021.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verstockt B, Verstockt S, Dehairs J, Ballet V, Blevi H, Wollants WJ, Breynaert C, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Ferrante M. Low TREM1 expression in whole blood predicts anti-TNF response in inflammatory bowel disease. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verstockt S, Verstockt B, Machiels K, Vancamelbeke M, Ferrante M, Cleynen I, De Hertogh G, Vermeire S. Oncostatin M Is a Biomarker of Diagnosis, Worse Disease Prognosis, and Therapeutic Nonresponse in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1564–1575. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West NR, Hegazy AN, Owens BMJ, Bullers SJ, Linggi B, Buonocore S, Coccia M, Görtz D, This S, Stockenhuber K, Pott J, Friedrich M, Ryzhakov G, Baribaud F, Brodmerkel C, Cieluch C, Rahman N, Müller-Newen G, Owens RJ, Kühl AA, Maloy KJ, Plevy SE Oxford IBD Cohort Investigators, Keshav S, Travis SPL, Powrie F. Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Med. 2017;23:579–589. doi: 10.1038/nm.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoyama Y, Yamakawa T, Miyake T, Kazama T, Hayashi Y, Hirayama D, Nakase H. Mucosal gene expression of inflammatory cytokines as biomarkers for predicting treatment response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Research Square. 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H, Xi L, Ziemek D, O'Neil S, Lee J, Stewart Z, Zhan Y, Zhao S, Zhang Y, Page K, Huang A, Maciejewski M, Zhang B, Gorelick KJ, Fitz L, Pradhan V, Cataldi F, Vincent M, Von Schack D, Hung K, Hassan-Zahraee M. Molecular Profiling of Ulcerative Colitis Subjects from the TURANDOT Trial Reveals Novel Pharmacodynamic/Efficacy Biomarkers. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:702–713. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiss LS, Papp M, Lovasz BD, Vegh Z, Golovics PA, Janka E, Varga E, Szathmari M, Lakatos PL. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein for identification of disease phenotype, active disease, and clinical relapses in Crohn's disease: a marker for patient classification? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1647–1654. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh K, Oh EH, Baek S, Song EM, Kim GU, Seo M, Hwang SW, Park SH, Yang DH, Kim KJ, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Ye BD. Elevated C-reactive protein level during clinical remission can predict poor outcomes in patients with Crohn's disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai C, Cao Q, Jiang M. Clinical Utility of Fecal Calprotectin Monitoring in Asymptomatic Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:E46–E47. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beltrán B, Iborra M, Sáez-González E, Marqués-Miñana MR, Moret I, Cerrillo E, Tortosa L, Bastida G, Hinojosa J, Poveda-Andrés JL, Nos P. Fecal Calprotectin Pretreatment and Induction Infliximab Levels for Prediction of Primary Nonresponse to Infliximab Therapy in Crohn's Disease. Dig Dis. 2019;37:108–115. doi: 10.1159/000492626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petryszyn P, Staniak A, Wolosianska A, Ekk-Cierniakowski P. Faecal calprotectin as a diagnostic marker of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms: meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:1306–1312. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson E, Bergemalm D, Kruse R, Neumann G, D'Amato M, Repsilber D, Halfvarson J. Subphenotypes of inflammatory bowel disease are characterized by specific serum protein profiles. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]