Abstract

Objective:

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with considerable caregiver and social burden. It is important to examine ways to minimize the negative effects of AD. Health care advocates (HCAs) may be one means of limiting the aversive effects of AD.

Method:

Participants completed a short survey that assessed their perceptions of the impact of comorbid AD on health status and their likelihood of hiring an HCA to assist in managing it. A mediational model was proposed: cognitive status (AD vs cognitively healthy) was the independent variable, perception of severity was the mediator, and the probability of hiring an HCA was the dependent variable.

Results:

The results indicated that the relationship between cognitive status and probability of hiring an HCA was fully mediated by perceptions of severity.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated that participants appreciated the impact of AD on health status, and this translated into a greater probability of hiring an HCA.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, comorbidity, caregiving, health care advocacy, mediation

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, chronic, neurodegenerative disorder that causes aberrations in memory, mood, and function. Alzheimer’s disease produces caregiver, social, and economic burdens. Estimates of its prevalence indicated that approximately 26.6 million individuals worldwide were affected by AD as of 2006. 1 In the United States alone, AD prevalence was estimated at 4.5 million persons in 2000 and was projected to increase by 293% to 13.2 million persons by 2050. 2 This means that approximately every 70 seconds, someone in the United States is diagnosed with AD—and that by 2050 someone will be diagnosed with AD every 33 seconds. 3 In 2008, the financial burden (direct and indirect) was estimated to be $148 billion annually in the United States. 3 Moreover, AD complicates, and increases costs of, care for comorbid conditions. For example, patients with early-stage AD had significantly higher medical costs than cognitively healthy controls for 8 of 10 comorbidities within a managed care organization (eg, the cost of chronic diabetes management was increased by $7466 annually 4 ). Perhaps most important, in the United States in 2006, AD was the sixth leading cause of death. 3

Beyond these worrisome social and economic costs, AD is an immense burden at the individual and familial levels. Perhaps more than any other disease, AD imposes extraordinary levels of caregiver burden. 5 The presence of cognitive, emotional, and functional problems in AD increases caregiver stress. 6 The burden of caring for ill, older adults is most frequently borne by the immediate family, with spouses constituting the first line of caregivers and adult children and their spouses comprising the second line of caregivers. 7 Though spousal caregivers experience a greater degree of strain across various domains (eg, relational, fiscal, and physical burdens), it appears that there are no differences in subjective well-being or the emotional, social, or occupational burdens incurred by adult children and spouses who are acting as caregivers. 7 The diminished experience of physical and relational burdens may be a function of the relative inability of adult children to be present with their ill parent much of the time, thereby limiting the amount of physical demands and interpersonal stressors. Pinquart and Sörensen 7 noted that adult children are much less likely than spouses to reside with their ill parent when they are providing caregiving for them and are much more likely to be employed. Thus, though they experience a great amount of emotional turmoil as a result of their parent’s illness and the need to provide care for their parent, they may not be able to provide the level or amount of care that they would like to provide as a result of other, competing social and occupational obligations.

The burdens and complexities of care for older populations, especially those with AD, may necessitate more care than can be provided by informal caregivers. It is estimated that, by 2030, an additional 3.5 million formally trained health care providers will be needed to assist in caring for the baby boomer generation. 3 Moreover, geriatric specialty training will need to be dramatically increased because less than 1% of physicians specialize in geriatrics. 3 Health care advocates (HCAs) may be able to provide assistance in caring for the aging population in the United States and relieving caregiver burden, particularly for those adult children, who must bear the weight of occupational and familial obligations beyond those presented by their parents’ illnesses and needs for care. Health care advocacy was started in the 1970s as a result of the patient rights movement. 8 Direct HCAs, sometimes referred to as patient advocates, provide needed assistance to patients and their families in navigating the complex health care system. Examples include finding resources and solutions for practical, legal, or medical problems, 8 all of which are consistent with many of the primary needs that have been cited by AD caregivers. 9 Clearly, these well-trained, specialized ombudsmen could reduce the individual, familial, social, and fiscal burdens imposed by the impending increase in AD and its comorbidities. Previous research in AD has demonstrated the effectiveness of such trained professionals providing educational, supportive, and assistive services for reducing caregiver burden and improving outcomes for individuals affected by AD. 10 –15 The purpose of the present study was to examine the following questions: (1) Is the severity of comorbid AD appreciated? (2) Do people perceive HCAs as viable means of obtaining assistance in caring for a loved one with AD? The present study attempted to answer these questions by examining community-dwelling adults’ perceptions of the severity of an older man’s medical conditions (AD and a comorbid physical malady) and their likelihood of hiring an HCA to assist in caring for him, imagining that he was their father. It was hypothesized that (1) the presence of comorbid AD would result in greater likelihoods of hiring an HCA to assist in his care and (2) this relationship would be mediated by participants’ perceptions of the severity of the man’s medical conditions.

Methods

Participants

The participants were 1078 adults, aged 18 years or older, randomly selected from the community. The mean age was 43.73 years (SD = 16.75); 29% were between the ages of 18 and 29, 48% were aged between 30 and 59 years, and 33% were 60 years of age or older. Most participants (53%) were female, White (68%), educated through some level of college (80%), and insured (84%). The median family income range was reported to be $60,000 to $89,999. Forty-five percent of participants were married, 38% were single, 10% were widowed, divorced, or separated, 6% were in a domestic partnership, and 1% reported their relational status as “other.” Approximately 13% of participants reported that they were single children, 53% reported they had 1 or 2 siblings, 24% reported having 3 or 4 siblings, and 7% reported having 5 or more siblings. Approximately 25% reported having been the primary care provider for their parent/parents at some time in their lives, but only 7% reported ever having hired an HCA or similar professional.

Procedures

Research assistants selected and approached participants using a random number sequence protocol. Participants were visiting Balboa Park located in San Diego. Balboa Park is the nation’s largest urban cultural park. More than 500 000 visitors come to Balboa Park each year. It was selected as a data collection site primarily because its popularity among visitors allows for the application of random selection procedures. In addition, this park attracts large numbers of culturally diverse participants. Research assistants approached potential participants and asked them whether they would be willing to participate in a study investigating factors associated with decisions made in various health situations.

Participants were required to understand and read English. They were told that their participation would take 5 to 10 minutes and that they would be given $5 as a token of appreciation for participation. Interested participants were asked whether they would be able to read two short paragraphs and complete a brief survey. Participants who met the criteria were given a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, a vignette, and a brief questionnaire to complete. The cover letter provided a one-paragraph description of an HCA. The questionnaires were anonymous and completed individually. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of San Diego State University, which determined that participants would not be required to sign an informed consent.

Vignettes

Participants were assigned randomly to read one of 8 vignettes that described a combination of 2 levels of distance (near or far from parent), 2 levels of physical malady (heart attack or hip fracture), and 2 levels of cognitive status (cognitively healthy or AD). The vignettes described a fictitious person, Daryl Smith. Daryl was described as being a 75-year-old, retired, widowed man who was informed recently that he would need surgery for a physical condition (ie, either heart bypass or hip replacement surgery). Participants were asked to imagine that they were James Smith, Daryl’s 42-year-old son. James was portrayed as being a well-to-do engineer with a busy schedule. He was married, but his wife was a successful lawyer who also had a busy schedule. Each of the aforementioned aspects was held constant in all vignette conditions.

Vignette Manipulations

Distance was varied by stating that James lived either (1) 20 minutes away from Daryl or (2) on the opposite coast from Daryl. Physical Malady was manipulated by stating that Daryl recently (1) had a heart attack requiring bypass surgery or (2) had fallen, breaking his hip, and required hip replacement surgery. Lastly, cognitive status was manipulated by depicting Daryl as (1) being cognitively healthy and mentally active or (2) having been diagnosed with AD recently.

Measures

After reading the vignette, participants were asked to assume that they were James Smith and to indicate, using a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 10 (extremely likely), how likely they would be to hire an HCA to perform 8 diverse assistive duties in caring for Daryl. The 8 questions participants answered listed the following duties: (1) staying with Daryl while in the hospital, (2) accompanying him to medical visits, (3) dealing with insurance issues, (4) coordinating medical appointments, (5) coordinating between health care professionals, (6) researching Daryl’s treatment options, (7) assisting him with daily symptom management, and (8) maintaining a medical record for Daryl. Participants were provided with a list of prospective sources from which they could obtain this assistance (with the standard cost per hour for obtaining services from each given specialist). They also were given the option to write in a source from which they would like to obtain the given service and how much they would be willing to pay for each of the 8 listed services. Participants also were asked to rate the severity of Daryl’s medical condition on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all severe) to 10 (extremely severe).

Analyses

A Cronbach α was performed to determine whether the 8 items used to measure the likelihood of hiring an HCA were internally consistent. The results indicated that there was high internal consistency (α = .884), and a factor analysis supported that the 8 items assessed a single dimension (see Table 1). Therefore, the 8 items were combined into an aggregate measure of the overall likelihood of hiring an HCA to assist Daryl.

Table 1.

Factor Analysis of 8 Hiring Questionsa

| Item | Factor loadings |

|---|---|

| Likely to hire while Daryl is in hospital | .634 |

| Likely to hire to accompany Daryl to his medical appointments | .740 |

| Likely to hire to deal with insurance issues | .707 |

| Likely to hire to coordinate medical appointments | .822 |

| Likely to hire to inform each member of treatment team | .815 |

| Likely to hire to research various treatment options | .710 |

| Likely to hire to assist with daily symptom management | .749 |

| Likely to hire to maintain medical records | .769 |

a One component extracted.

Next, a Sobel-Goodman mediational analysis was performed using Stata/IC 12.1. The mean overall likelihood of hiring an HCA was specified as the dependent variable (DV); perception of severity was defined as the mediating variable (MV); and the binary (AD vs cognitively healthy), independent variable (IV) was cognitive status. The Sobel-Goodman approach uses regression analyses to estimate the relationships between the specified IV, MV, and DV. It specifies 4 paths: (A) the relationship between the IV and MV, (B) the relationship between the MV and DV, (C) the relationship between the IV and DV, and (C’) the relationship between the IV and DV, given path B. Next, the Sobel-Goodman test is conducted to determine whether the proportion of variance mediated is statistically significant. It was hypothesized that paths A, B, and C would be statistically significant, but that path C’ would not be significant (indicating that the relationship between the presence of comorbid AD and likelihood of hiring an HCA is mediated by perceptions of severity). All analyses were performed averaging across the levels of the other vignette manipulations (physical malady and distance), because neither of these was found to impact hiring probabilities significantly (t(1075) = −.862, P = .389; t(1075) = .546, P = .585, respectively; [heart attack: M = 6.45; SD = 2.20; hip fracture: M = 6.33; SD = 2.21; near: M = 6.35; SD = 2.27; far: M = 6.43; SD = 2.14]).

Results

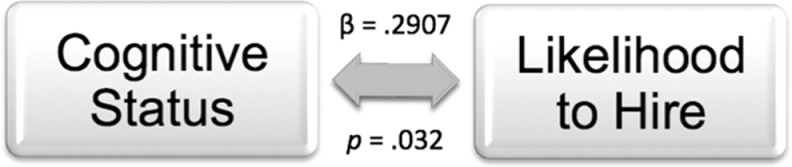

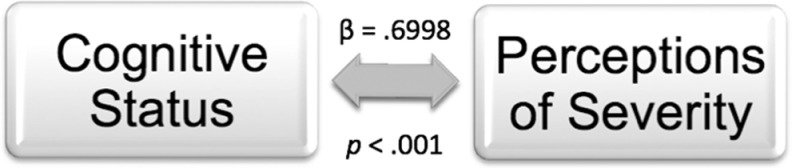

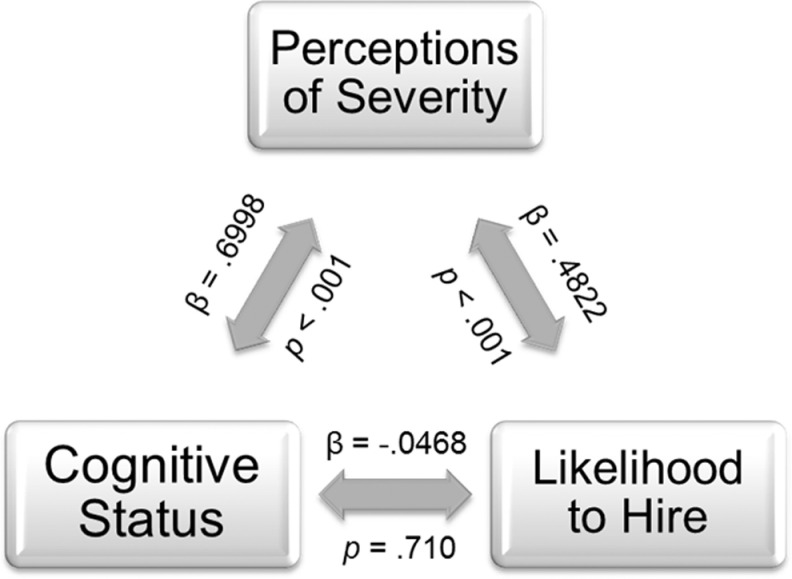

Path C (IV ⇒ DV) was significant, F(1, 1050) = 4.63, P = .032. This demonstrated a significant relationship between cognitive status and overall likelihood of hiring, such that participants reported a significantly higher likelihood of hiring an HCA for Daryl when he had a diagnosis of comorbid AD than when he was cognitively healthy (see Figure 1). Path A (IV ⇒ MV) was significant, F(1, 1050) = 37.92, P < .001, showing that cognitive status and perceptions of severity were related significantly, such that participants rated Daryl’s medical condition as significantly more severe when he had comorbid AD than when he was cognitively healthy (see Figure 2). The model for Paths B and C’ was also statistically significant (IV ⇒ MV ⇒ DV), F (2, 1049) = 106.01, P < .001, R 2 = .0349, root MSE = 1.8246, demonstrating that the meditational model fit well. Path B was significant (MV ⇒ DV|IV), t(1049) = 14.37, P < .001, indicating that participants were significantly more likely to hire an HCA when Daryl’s condition was perceived as more severe than when his condition was perceived as less severe. However, Path C’ (IV ⇒ DV|MV) was not significant, t(1049) = −0.37, P = .71, 95% CI (−.2936, .2000), demonstrating that the relationship between the IV and DV in the presence of the MV was not statistically different from 0. The Sobel-Goodman test was statistically significant, z = 5.66, P < .001, with the proportion of the total effect mediated being bounded at 1.00. This shows that the effect of cognitive status and overall likelihood of hiring an HCA was fully mediated by perceptions of severity (see Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Path C: estimated relationship between independent variable and dependent variable.

Figure 2.

Path A: estimated relationship between independent variable and mediator.

Figure 3.

Paths A, B, and C’: estimated relationships between independent variable, mediator, and dependent variable.

Discussion

First, it was interesting that neither the physical malady nor distance resulted in increased likelihoods of hiring an HCA. Perhaps participants felt that either physical malady (heart attack or hip fracture), and subsequent surgery, was serious enough to necessitate help—eliminating any between-group effect. This is reasonable considering that the mean likelihood to hire for either of the physical conditions was relatively high. Similarly, perhaps distance was a factor that seemed peripheral. Participants did not differ in their likelihood of hiring an HCA, irrespective of distance from their hypothetical father. It is possible that participants felt they would be unable to manage the burdens of caring for an older man with such severe medical conditions alone, obviating any effect that may have been anticipated as a result of distance. However, as hypothesized, our primary findings suggest that community-dwelling adults recognize and appreciate the negative impact of comorbid AD. This is supported by the fact that participants were significantly more likely to hire an HCA when Daryl had comorbid AD, because his condition was perceived as more severe.

Our results suggest that the considerable efforts that have been and are being made to raise awareness of AD throughout the populace appear to be successful (for a review of public knowledge of AD, see 16 ). Although we cannot conclude unequivocally from this study that awareness of and concern for AD have increased, it is clear that awareness and understanding of AD were necessary for participants to view AD as a condition that would increase the severity of an older man's medical condition and thereby be more likely to choose to hire an HCA to provide assistance. Thus, our findings would suggest that efforts to increase the awareness of AD as a health concern, and not a normal aging process, have been successful. Participants appraised comorbid AD as a condition that would be detrimental to one’s overall health status and, thus, would warrant hiring a professional, such as an HCA, to provide additional assistance.

Beyond this, our findings suggest that our sample viewed HCAs as a viable means of gaining needed assistance in caring for a loved one, at least once an individual is made aware of the existence of professionals who perform such activities. Only 6.8% of participants from our sample reported having ever hired an HCA, though 24.6% reported having been the primary caregiver for a parent. One possible explanation for this inconsistent finding is that participants were told to imagine that they were a wealthy engineer, which may have decreased the monetary prohibitions of hiring an HCA for many. Though it is beyond the scope of this article, future research should explore the perceptions of cost–benefit ratios from the public concerning hiring an HCA.

Another possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that much of the general population likely is unaware of the existence of the professional field of health care advocacy, considering that it is still in its infancy. For example, the National Association of Healthcare Advocacy Consultants (NAHAC), the organization that has written the code of ethics for the profession, was established only 3 years ago. 17 Moreover, we know of no studies that have evaluated public awareness or knowledge of health care advocacy. Considering the paucity of gerontological specialists in the health care field, the known burden of caregiving for AD, the rising prevalence of the disorder and its exorbitant economic and social costs, 3 AD may be one of the most appropriate domains for HCAs. Perhaps the general feeling that support and assistive care are inadequate, which appear to be widespread throughout the AD caregiver community, 5 could be changed via the use of professionals such as HCAs. Thus, exploring the knowledge about HCA in general, and more direct evaluations of the utility of HCAs for AD, seems warranted.

Overall, our findings engender some degree of hope. It seems that the burden posed by AD may be recognized in the general populace. Moreover, our findings suggest that individuals may want to pursue assistance in managing this disorder from trained professionals who are devoted solely to the patient and his or her family. As a result, it seems there may be cause for optimism concerning how the general population is likely to respond to the impending influx of AD cases, as people appear to recognize the severity of the disorder and the need for assistance in its management. Realizing this is the first step toward decreasing the burden of AD at the familial, societal, and economic levels. However, this also mandates that individuals be made aware, not only of the seriousness of AD but also of avenues by which assistance can be sought to manage it—such as HCAs. Thus, it seems that health professionals and policy makers concerned with AD are at the crossroads of two population-wide, health-educational needs. The first (increasing awareness of AD), it seems, is being met; the second (increasing awareness of professions such as health care advocacy as means of gaining assistance in managing AD), appears to require additional education and possibly promotion.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer’s disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alzheimer’s Association. 2009. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(3):234–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fillit H, Hill JW, Futterman R. Health care utilization and costs of Alzheimer’s disease: the role of co-morbid conditions, disease stage, and pharmacotherapy. Fam Med. 2002;34(7):527–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Georges J, Jansen S, Jackson J, Meyrieux A, Sadowska A, Selmes M. Alzheimer’s disease in real life – the dementia carer’s survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergvall N, Brinck P, Eek D, et al. Relative importance of patient disease indicators on informal care and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(1):73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Spouses, adult children, and children-in-law as caregivers of older adults: a meta-analytic comparison. Psychol Aging. 2011;26(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hurst M. Health advocacy. Defining the field. 2007. http://www.slc.edu/graduate/programs/health-advocacy/Defining_the_Field.html. Accessed May 21, 2012.

- 9. Rosa E, Lussignoli G, Sabbatini F, et al. Needs of caregivers of the patients with dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(1):54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andrén S, Elmståhl S. Psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia reduces caregiver's burden: development and effect after 6 and 12 months. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(1):98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cuellar N, Butts JB. Caregiver distress: what nurses in rural settings can do to help. Nurs Forum. 1999;34(3):24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garcés J, Carretero S, Ródenas F, Alemán C. A review of programs to alleviate the burden of informal caregivers of dependent persons. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(3):254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gelmini G, Morabito B, Braidi G. Educational and formative training reduce stress in the caregivers of demented persons. Arch Geontol Geriatr. 2009;49(suppl 1):119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teri L, McCurry SM, Logsdon R, Gibbons LE. Training community consultants to help family members improve dementia care: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):802–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Mierlo LD, Meiland FJ, Dröes RM. Dementelcoach: effect of telephone coaching on carers of community-dwelling people with dementia. Int Psychgeriatr. 2012;24(2):212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson LA, Day KL, Beard RL, Reed PS, Wu B. The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease among the U.S. population: A national review. Gerontologist. 2009;49:S3–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Association of Healthcare Advocacy Consultants. National Association of Healthcare Advocacy Consultants. Code of Ethics. 2009. http://www.nahac.com/code/. Accessed May 22, 2012.